#abakuá

Text

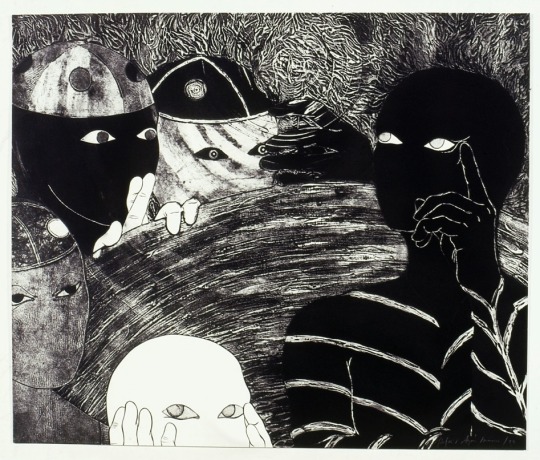

I Always Return, Belkis Ayón - 1993

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Music of African heritage in Cuba derives from the musical traditions of the many ethnic groups from different parts of West and Central Africa that were brought to Cuba as slaves between the 16th and 19th centuries. Members of some of these groups formed their own ethnic associations or cabildos, in which cultural traditions were conserved, including musical ones. Music of African heritage, along with considerable Iberian (Spanish) musical elements, forms the fulcrum of Cuban music.

Much of this music is associated with traditional African religion – Lucumi, Palo, and others – and preserves the languages formerly used in the African homelands. The music is passed on by oral tradition and is often performed in private gatherings difficult for outsiders to access. Lacking melodic instruments, the music instead features polyrhythmic percussion, voice (call-and-response), and dance. As with other musically renowned New World nations such as the United States, Brazil and Jamaica, Cuban music represents a profound African musical heritage.

Clearly, the origin of African groups in Cuba is due to the island's long history of slavery. Compared to the USA, slavery started in Cuba much earlier and continued for decades afterwards. Cuba was the last country in the Americas to abolish the importation of slaves, and the second last to free the slaves. In 1807 the British Parliament outlawed slavery, and from then on the British Navy acted to intercept Portuguese and Spanish slave ships. By 1860 the trade with Cuba was almost extinguished; the last slave ship to Cuba was in 1873. The abolition of slavery was announced by the Spanish Crown in 1880, and put into effect in 1886. Two years later, Brazil abolished slavery.

Although the exact number of slaves from each African culture will never be known, most came from one of these groups, which are listed in rough order of their cultural impact in Cuba:

The Congolese from the Congo Basin and SW Africa. Many ethnic groups were involved, all called Congos in Cuba. Their religion is called Palo. Probably the most numerous group, with a huge influence on Cuban music.

The Oyó or Yoruba from modern Nigeria, known in Cuba as Lucumí. Their religion is known as Regla de Ocha (roughly, 'the way of the spirits') and its syncretic version is known as Santería. Culturally of great significance.

The Kalabars from the Southeastern part of Nigeria and also in some part of Cameroon, whom were taken from the Bight of Biafra. These sub Igbo and Ijaw groups are known in Cuba as Carabali,and their religious organization as Abakuá. The street name for them in Cuba was Ñáñigos.

The Dahomey, from Benin. They were the Fon, known as Arará in Cuba. The Dahomeys were a powerful group who practised human sacrifice and slavery long before Europeans arrived, and allegedly even more so during the Atlantic slave trade.

Haiti immigrants to Cuba arrived at various times up to the present day. Leaving aside the French, who also came, the Africans from Haiti were a mixture of groups who usually spoke creolized French: and religion was known as vodú.

From part of modern Liberia and Côte d'Ivoire came the Gangá.

Senegambian people (Senegal, the Gambia), but including many brought from Sudan by the Arab slavers, were known by a catch-all word: Mandinga. The famous musical phrase Kikiribu Mandinga! refers to them.

Subsequent organization

The roots of most Afro-Cuban musical forms lie in the cabildos, self-organized social clubs for the African slaves, and separate cabildos for separate cultures. The cabildos were formed mainly from four groups: the Yoruba (the Lucumi in Cuba); the Congolese (Palo in Cuba); Dahomey (the Fon or Arará). Other cultures were undoubtedly present, more even than listed above, but in smaller numbers, and they did not leave such a distinctive presence.

Cabildos preserved African cultural traditions, even after the abolition of slavery in 1886. At the same time, African religions were transmitted from generation to generation throughout Cuba, Haiti, other islands and Brazil. These religions, which had a similar but not identical structure, were known as Lucumi or Regla de Ocha if they derived from the Yoruba, Palo from Central Africa, Vodú from Haiti, and so on. The term Santería was first introduced to account for the way African spirits were joined to Catholic saints, especially by people who were both baptized and initiated, and so were genuine members of both groups. Outsiders picked up the word and have tended to use it somewhat indiscriminately. It has become a kind of catch-all word, rather like salsa in music.

The ñáñigos in Cuba or Carabali in their secret Abakuá societies, were one of the most terrifying groups; even other blacks were afraid of them:

Girl, don't tell me about the ñáñigos! They were bad. The carabali was evil down to his guts. And the ñáñigos from back in the day when I was a chick, weren't like the ones today... they kept their secret, like in Africa.

African sacred music in Cuba

All these African cultures had musical traditions, which survive erratically to the present day, not always in detail, but in the general style. The best preserved are the African polytheistic religions, where, in Cuba at least, the instruments, the language, the chants, the dances and their interpretations are quite well preserved. In few or no other American countries are the religious ceremonies conducted in the old language(s) of Africa, as they are at least in Lucumí ceremonies, though of course, back in Africa the language has moved on. What unifies all genuine forms of African music is the unity of polyrhythmic percussion, voice (call-and-response) and dance in well-defined social settings, and the absence of melodic instruments of an Arabic or European kind.

Not until after the Second World War do we find detailed printed descriptions or recordings of African sacred music in Cuba. Inside the cults, music, song, dance and ceremony were (and still are) learnt by heart by means of demonstration, including such ceremonial procedures conducted in an African language. The experiences were private to the initiated, until the work of the ethnologist Fernando Ortíz, who devoted a large part of his life to investigating the influence of African culture in Cuba. The first detailed transcription of percussion, song and chants are to be found in his great works.

There are now many recordings offering a selection of pieces in praise of, or prayers to, the orishas. Much of the ceremonial procedures are still hidden from the eyes of outsiders, though some descriptions in words exist.

Yoruba and Congolese rituals

Main articles: Yoruba people, Lucumi religion, Kongo people, Palo (religion), and Batá

Religious traditions of African origin have survived in Cuba, and are the basis of ritual music, song and dance quite distinct from the secular music and dance. The religion of Yoruban origin is known as Lucumí or Regla de Ocha; the religion of Congolese origin is known as Palo, as in palos del monte.[11] There are also, in the Oriente region, forms of Haitian ritual together with its own instruments and music.

In Lucumi ceremonies, consecrated batá drums are played at ceremonies, and gourd ensembles called abwe. In the 1950s, a collection of Havana-area batá drummers called Santero helped bring Lucumí styles into mainstream Cuban music, while artists like Mezcla, with the lucumí singer Lázaro Ros, melded the style with other forms, including zouk.

The Congo cabildo uses yuka drums, as well as gallos (a form of song contest), makuta and mani dances. The latter is related to the Brazilian martial dance capoeira

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#brown skin#afrakans#african culture#fitness#afrakan spirituality#afro cuban music#afro cuban#igbo#yoruba#congo#african music

124 notes

·

View notes

Photo

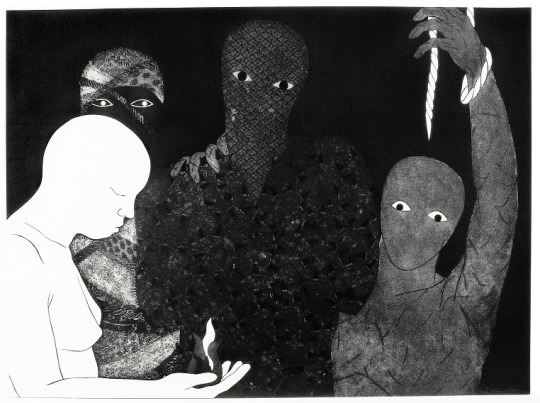

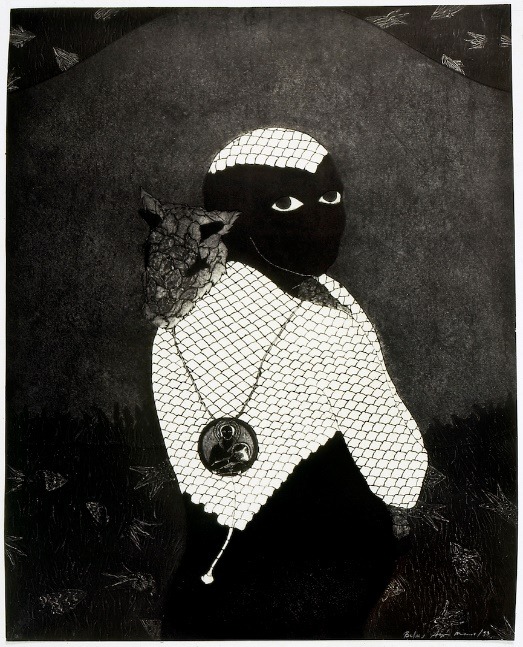

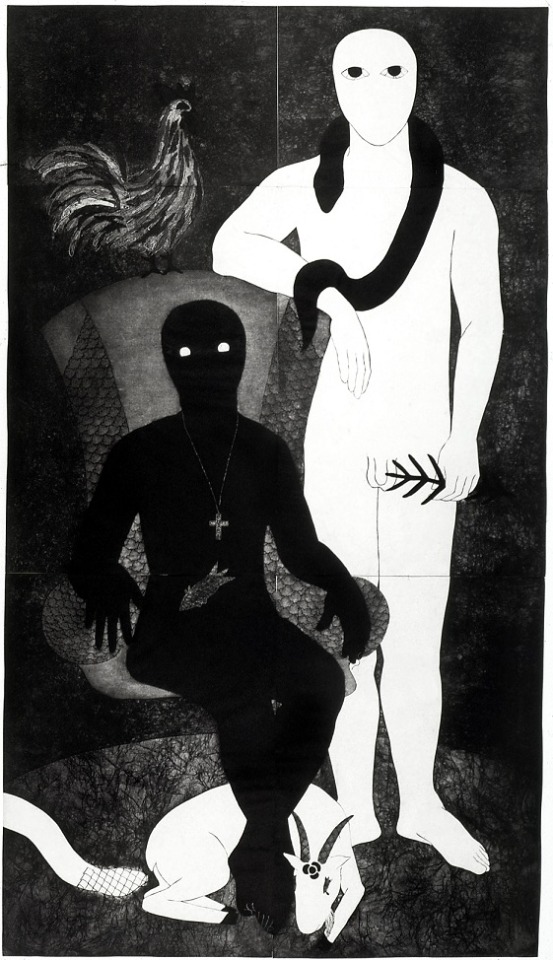

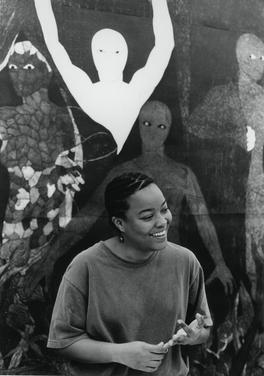

Belkis Ayón is another talented artist who died very early - at 32.

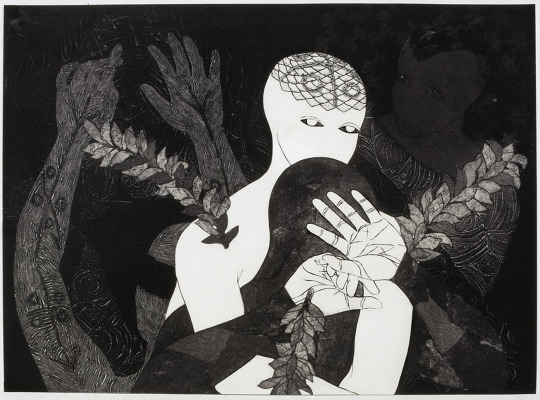

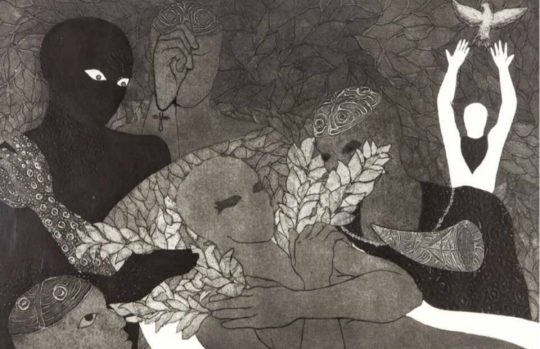

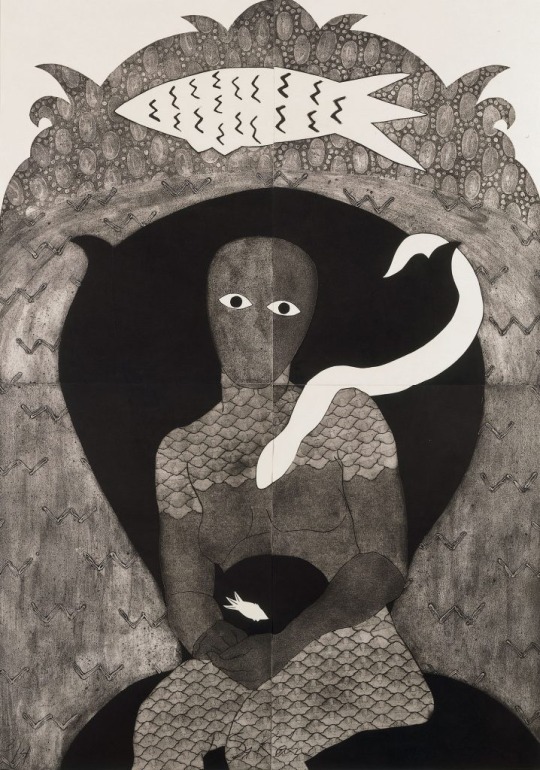

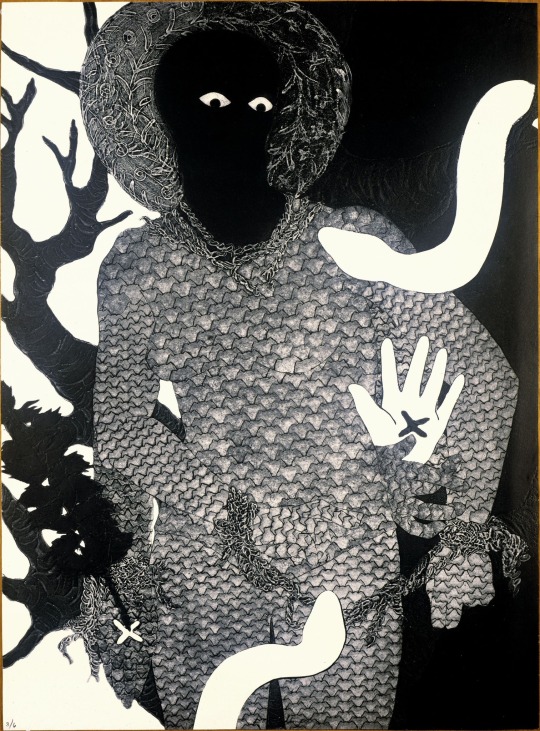

Belkis Ayón (1967 – 1999) was a Cuban printmaker who specialized in the technique of collography. Ayón is known for her large, highly-detailed allegorical collographs based on Abakuá, a secret, all-male Afro-Cuban society. Her work is often in black and white, consisting of ghost-white figures with oblong heads and empty, almond-shaped eyes, set against dark, patterned backgrounds.

A central theme of Ayón's art is Abakuá, a secret, exclusively male association with a complex mythology that informs their rites and traditions. The fraternal society began in Nigeria at Cross River and Akwa Ibom and was brought to Haiti and Cuba through the slave trade in the 19th century.

Ayón researched the history of Abakuá extensively, with special emphasis on the most prominent and only female figure in the religion, Princess Sikan. According to a central Abakuán myth, Sikan once accidentally captured Tanze, an enchanted fish which imparted great power to those who heard its voice. When she took the fish to her father, he warned her to remain silent and never speak of it again. She did divulge the information however, to her fiance, leader of an enemy tribe. Her punishment was a death sentence and with her, Tanze also died.

This story comes in the form of imposed silence in her work, a major theme. The concept of imposed silence is evident in the lack of mouths in all of her figures. Belkis Ayón demonstration of Sikan’s betrayal in her collographs may be considered a transgression because, ironically, Ayon, a female artist, gives voice to the main antagonist Sikan, a woman, in Abakua mythology, which traditionally prohibits women. In this way, Belkis rebelled against the sexist and patriarchal culture argued to be ingrained in Cuban society by highlighting the religion’s feminine presence.

To date, Ayón has been the only prominent artist to create an extensive body of work based on the Abakuán society. Because the society itself had created very few visual representations of its myths, Ayón had great freedom to visually interpret their myths for herself. Numerous Abakuán rituals are represented in her collographs, many of which draw on Christian as well as Afro-Cuban traditions. Abakuán beliefs existed in sharp contrast to the atheistic anti-religious position of the Cuban communist government at the time.

Ayón killed herself with a gunshot to the head at home in Havana on 11 September 1999. She was 32. Reasons for her suicide still remain a mystery to her friends and family. However,The New York Times obituary quotes her as saying of her art, in the year that she died:

"These [works] are the things I have inside that I toss out because there are burdens with which you cannot live or drag along, ...Perhaps that is what my work is about — that after so many years, I realize the disquiet."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belkis_Ay%C3%B3n

https://rjm-resist.de/en/portfolio-item/belkis-ayon-manso-2/

444 notes

·

View notes

Text

Belkis Ayón

Ayón was a Cuban printmaking artist who specialised in collagraphy, making works based on Abakuá, an Afro-Cuban men's secret society. Her works feature ghost-like black and white figures. While the subject of these painting aren't actually ghosts, I find the figures really intriguing in terms of my concept.

I love her use of negative space and the balance of greys and blacks to add a transparent quality.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watch "Joey Diaz Explains The Abakuá Brotherhood #shorts" on YouTube

0 notes

Text

Mariwó o palma real

Juega un papel muy importante en la religión yoruba, no solamente como árbol sagrado, sino como planta medicinal, por eso, es un elemento que no debe faltar en ningún ìlé (casa religiosa) ya que se utiliza para identificarse como religiosos de la osha e Ifá, representa un poder o condición divina, se trata de un árbol cargado de fuerzas sagradas, la corona de hojas (o penacho) es grande, casi circular, frondosa y siempre verde, simboliza lo eterno, lo perenne, l a palma real se divide en hembra, que es la de porte bajo, ensanchada, jorobada y gran productora de frutos y en la palma macho que es de tronco recto, alta, poco productora de frutos y es la cual que se ocupa para fabricar le escobilla sagrada.

Debido a esta sacralidad que posee la palma real, la ocupan para confeccionar instrumentos poseedores de una fuerza sobrenatural, como por ejemplo la escobilla que se hace con esta palma se utiliza para hacer obras, despojos, o limpiezas de los ìlés , en muchos ìlés se le ponen 7 tiras de diferentes colores y se baldea la casa con ewés, hielo y leche para sacar el mal y se barre de atrás hacia adelante, para poner altares, se le coloca a Ògún afuera de su caldero como un faldón, también forma parte del traje ritual de Shangó (aunque Shangó es fiel a la ceiba su trono es la majestuosa palma, desde ahí vigila y cuida a sus hijos, tambien se le depositan distintas ofrendas y ẹbọs a Shangó) y de los guerreros, Elegguá, Òshosi y Ògún, tambien en esta palma se le rinde culto a Oyá la dueña de los vientos y centellas, si un Ìyàwó es hijo de alguno de estos orishas se coloca una especie de saya o faldilla de flecos secos confeccionada con las hojas de la palma real que se coloca en la cintura del iniciado (Ìyàwó) sobre el propio traje, las hojas de la palma real también se colocan a la entrada del igbódùn o cuarto de consagraciones, (es la cortina que divide el igbódùn, de la vida social de la religiosa), junto a una sábana blanca en el dintel de la puerta según corresponda al orisha, al orisha Babalú Ayé, sincretizado con San Lázaro y a Naná Burúkú, madre del mismo, se les confecciona el llamado já, (especie de escobilla que se realiza con las fibras del coco que da esta palma) en la empuñadura va la carga y se decoran con cintas y cuentas, utilizándola para hacer ẹbọ o limpiezas y librar así a sus hijos de epidemias o enfermedades, el objetivo principal del Mariwó es dividir lo mundano de lo religioso, en la entrada de sus casas para espantar a las entidades espirituales retrasadas, otros lo utilizan en misas espirituales y en los ìtas se recomienda usarlo para protección, pero eso ya depende de cada padrino o madrina, con la madera de esta palma se confecciona el Oshe que es una figura representativa de Shangó y es un refuerzo del rey del fuego, en los altares para Shangó no puede faltar la palma.

Tambien es importante el Mariwó en las consagraciones de Ifá, ya que sin el cual

no puede haber Bàbáláwos, también habla de la importancia de Bàbá Shangó

dentro de las consagraciones de Ifá ya que Shangó es Bàbáláwo y se llama

ORANIFE ÀWÔ MAGBÁ y el tenia hecho Ifá por OLÓDÙMÀRÈ.

También es una herramienta que pertenece a Ògún, para algunos olorishas la

palma real es el bastón de Ággayú, padre de Shangó.

Para los carabalí muy conocidos por las asociaciones abakuá o de ñañigos, la

palma real recibe el nombre de Ukano Mambre y es de gran importancia ya que

bajo una palma real se organizó por vez primera esta secta religiosa exclusiva para

hombres, esta palma fue testigo del descubrimiento del secreto Abakuá por parte de la princesa Sikán, secreto que luego confió a otras tribus, de ahí que las mujeres no sean aceptadas en dicha sociedad, despues de esto sikán fue

sentenciada junto a una ceiba y sepultada bajo una palma real, quien fue el único testigo de lo sucedido.

La palma real en la religión católica se utiliza en la celebración de la Semana Santa

que se inicia con el llamado Domingo de Ramos.

En la rama conga conocida como palo mayombe o palo monte en algunos munanzos se le coloca un mariwo en la parte de afuera y tambien se le coloca como faldon a la

Nganga.

Al Mariwó o palma real tambien se le conoce como falda de guano, diba, lala, mabba, dunkende.

En el ọdún de Otura Sá hay un refrán que dice.

Muere una palma para que nazca un Àwó.

Y el pataki se llama la tierra de la desconfianza.

Era una tierra llamada MABINO INLE donde todos, desde el rey hasta el mas pequeño vasallo eran, OGUBA y en razón de esto aquella tierra llego a ser

conocida como Otura Sá Nílé que era tierra de desconfianza.

El rey que era OTURA SÁ deseaba unir a todos sus hijos y súbditos y acabar con aquella desconfianza, llamo en su ayuda a todos los Ọbas y adivinos de las tierras vecinas, los cuales le dijeron.

Estamos dispuestos a unirnos a ti, pero esta desconfianza que hay en tu pueblo hay que vencerla porque si no la desconfianza hundirá a todos los pueblos y cualquier cosa que deseemos hacer fracasará, ellos empezaron a tratar de unir a la gente pero la desconfianza impedía el exito.

Así que todos decidieron ir a ver al rey de los adivinos que era ORANIFE ÀWÓ MAGBÁ que era Shangó, que tenia hecho Ifá por OLÓDÙMÀRÈ.

Cuando llegaron a donde estaba, el les pregunto que querian, ellos le explicaron su objetivo, que consistía en unirse para formar una sociedad, entonces Shangó respondió.

Tienen que buscar a los 16 jefes de esa sociedad, que no están entre ustedes, pues ellos están escondidos hace mucho tiempo en la Ope (palma) para que ellos salgan hay que hacer una obra, Shangó explico la obra y lo que llevaba.

Todos se pusieron de acuerdo y le llevaron a ORANIFE todo lo que pidió, que principalmente eran 16 jicoteas.

Entonces ORANIFE fue debajo de cada palma y hacía la ceremonia y entonces en la primera palma en la que realizo la ceremonia bajo un personaje que se identifico con el nombre de BÀBÁ EJIOGBE, en la siguiente apareció BABA OYEKÚN MÉJÌ, así hasta llegar a la palma número 16 que era BÀBÁ OFÚ MÉJÌ.

Cuando terminó ORANIFE dijo.

Ahora éstos serán los jefes de la sociedad y todos tenemos que jurar fidelidad a ellos y a todos nosotros, y para eso tenemos que firmar un pacto y que mejor para firmarlo que la tabla de la ley que se haga con el cuerpo de la palma, que murió para que nacieran estos Àwós, entonces en esa tabla de palma sellaron el pacto de los ọdún méjìs.

Los de la tierra OTURA SÁ NÍLÉ y todos los demas vecinos terminaron asi la desconfianza, entonces en la tierra OTURA SÁ NÍLÉ se creo un cofradía o sociedad de Àwós, por ello siempre muere una palma para que nazca un Àwó.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Michele Rosewoman's New Yor-Uba - Old Calabar (Abakuá)

0 notes

Video

youtube

Abakuá is an Afro-Cuban men's initiatory fraternity, or secret society

0 notes

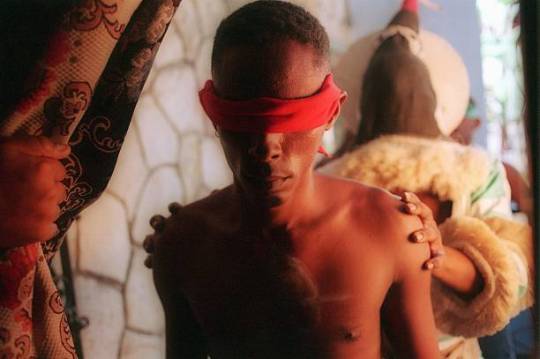

Text

The Abakuá Brotherhood - Ancient Beliefs Thrive In Cuba

An "Ireme" or "Diablito" (masked dancer) leads a blindfolded "Indeceme" (initiate) to a larger room where the main part of an Abacua a two-day initiation ceremony will take place on July 16, 2000 in the Santo Suarez district of Havana, Cuba. Abacua, a secret Afro-Cuban men's initiatory fraternity or brotherhood, was brought over from Africa by tribes nations from the Cross River delta region between Nigeria and Cameroon

#Abakuá#Brotherhood#Ancient#Ireme#Diablito#Indeceme#initiate#Santo Suarez#Havana#Cuba#secret#Afro-Cuban#fraternity#Cross River Delta Region#Nigeria#Cameroon#African Descent#African Diaspora

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

al things considered — when i post my masterpiece #714

first posted in facebook june 30, 2019

belkis ayón -- "la cena" [i.e., the supper] (1991)

"people are intrigued because the eyes look at you directly ... i believe that you cannot hide — wherever you go they are there, always looking at you, making you an accomplice of what you are seeing” ... belkis ayón

"ayón’s choice of subject matter—the history and mythology of abakuá—was a direction she took in 1985 while still a high school student ... this brotherhood arrived in the western port cities of cuba in the early 19th century, carried by enslaved africans from the cross river region of southeastern nigeria, and since then became a nucleus of protection and resistance for its members. a brief synopsis of the founding myth of abakuá begins with sikán, a princess who inadvertently trapped a fish while drawing water from the river. she was the first to hear the unexpected and loud bellowing of the fish, the mystical 'voice' of abakuá. because women were not permitted this sacred knowledge, the local diviner swore sikán to secrecy. sikán, however, revealed her secret to her fiancé, and because of her indiscretion was condemned to death. in ayón’s work, sikán remains alive, and her story and representation figure prominently" ... from station museum of contemporary art

"these are the things i have inside that i toss out because there are burdens with which you cannot live or drag along ... perhaps that is what my work is about — that after so many years, i realize the disquiet” ... belkis ayón [on her art the year before she died]

"ms. ayón committed suicide at home sept. 11, 1999, age 32. her family and friends said they didn’t know why" ... sandra e. garcia

"the eyes have it" ... al janik

#belkis ayón#la cena#the supper#the last supper#the eyes#abakuá#sikán#cuba#nigeria#station museum of contemporary art#the disquiet#suicide#sandra e. garcia#al things considered

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Belkis Ayón: "Nkame" is on view at El Museo del Barrio in NYC through November 5. Belkis Ayón, La Consagración, 1991, collograph. #belkisayón #printmaking #cuba #havana #abakuá #nigeria #prints #nyc #museum @elmuseo #nkame (at El Museo del Barrio)

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Abakuá, also sometimes known as Nañigo, is an Afro-Cuban men's initiatory fraternity or secret society, which originated from fraternal associations in the Cross River region of southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon.

Abakuá has been described as "an Afro-Cuban version of Freemasonry".

The Cuban artist Belkis Ayón intensively investigated the Abakuá mythology in her prints.

Abakuá members derive their belief systems and traditional practices from the Efik, Efut, Ibibio Igbo and Bahumono spirits that lived in the forest. Ekpe and synonymous terms were names of both a forest spirit and a leopard related secret society. Much of what the Abakua believe in terms of religion is considered a secret only known to members

Due to the secrecy of the society, little is known of the Abakuá language. It is assumed to be a creolized version of Efik or Ibibio, both closely related languages or dialects from the Cross River region of Nigeria, because this is the cultural region and ethnic groups where the society originated

#abakua#african#african culture#nanigo#afro cuban#cameroon#nigeria#belkis ayon#ibibio#igbo#efut#efik#leopard#cross river#kemetic dreams#spirituality

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cuban Printmaker Belkis Ayón (1967-1999) was a Cuban printmaker who specialised in the technique of collography. Ayón created large, highly detailed allegorical collagraphs based on Abakuá, a secret, all-male Afro-Cuban society. Her work is often in black and white, consisting of ghost-white figures with oblong heads and empty, almond-shaped eyes, set against dark, patterned backgrounds.

Ayón killed herself with a gunshot to the head at home in Havana on 11 September 1999. She was 32. Reasons for her suicide still remain a mystery to her friends and family. However,The New York Times obituary quotes her as saying of her art, in the year that she died:

"These [works] are the things I have inside that I toss out because there are burdens with which you cannot live or drag along, ...Perhaps that is what my work is about — that after so many years, I realize the disquiet."

Collagraphy—a printing technique in which collaged and textured materials are painstakingly layered onto a cardboard matrix.

https://www.frieze.com/.../how-myth-sacrificed-princess...

109 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Even after the end of slavery, the masters of Haitian machete fighting continued to teach in a progression from training with sticks to mastery of the machete. An aspirant in this system first learned tiré bwa, the art of fencing with sticks as a safe way to learn the strikes and defenses of the system in relative safety. Only after achieving some proficiency in tiré bwa, did masters then teach the student tiré coutou (knife) or, more importantly, at least one of many styles of tiré machet, the art of machete fighting. Although basic proficiency could be attained in less than half a years training, mastery required much higher levels. The test of graduation to mastery often involved defending oneself blindfolded or in a completely dark room. In order to pass this test the student had to master a system called “the secret of Dessaline,” which developed the skill allowing a master to fight without the use of his eyesight.[8] In Cuba, the feared Abakuá societies perpetuated elements of the Biafran paramilitary tradition. Based upon the leopard societies of Biafra, enslaved Africans in Cuba established Abakuá as a mutual aid society promoting proper behavior and community defense. Abakuá members, known as ñáñigos, enforced strict standards of communal protection and individual “manliness.” A ñáñigo could never let himself be struck by anyone without dire consequences for the offender. Ritual conflicts also occurred between different Abakuá groups. To show themselves as brave, ñáñigos would demonstrate their abilities with machetes and knives in these conflicts. According to Lois Martínez-Fernández, one of the requirements of initiation was to “test iron”, or kill a white person with a machete or large knife.[9]

T. J. Desch-Obi - Peinillas and Popular Participation: Machete fighting in Haiti, Cuba and Colombia [Memorias. Revista Digital de Historia y Arqueología desde el Caribe, vol. 6, núm. 11, noviembre, 2009, pp. 144-172]

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watch "Joey Diaz Explains Mike Tyson What Abakuá Brotherhood Is #shorts" on YouTube

0 notes

Text

Belkis Ayon (1967-1999)

Belkis Ayon était une artiste cubaine connue pour ses collographies en noir et blanc. Elle était très intéressée par les Abakuá, une société secrète cubaine composée entièrement d’hommes afro-cubains.

« Sikán » (seconde édition), 1991, Collographie

À Abakuá, il n’y a aucune femme, ce qui découle de l’histoire de Sikán, la seule femme de Abakuá qui a été mise a mort pour avoir révélé les secrets de la société. Alors, Ayon s'est inspirée de la tradition et a visé son attention vers Sikán, qui est devenue le centre de son travail.

« La sentencia », 1993, Collographie

Sur tous ses tableaux on peut voir que la bouche de Sikán est absente, qu’on peut interpréter comme si la société avait voulu la faire taire en la tuant. De plus, on sent l’entrave à sa liberté d’expression parce que ses mains sont liées par ce qui semble être une chaine. Dans ses deux tableaux, on pourrait croire à une représentation de Sikán du point de vue de la société de Abuaká car elle est représentée avec des écailles et des symboles incarnant le Mal.

« La cena », 1991, Collographie

Ayon a également placé Sikán dans des décors combinant Abuaká et des symboles chrétiens. On remarque dans les trois tableaux la présence de serpents, signe incontestable du diable et de la trahison dans le christianisme. Ici, Sikán est placée au banquet d'initiation d'Abuakán. C’est une référence à la Cène. Elle remplace Jesus en tant qu’élément central. Aussi, on remarque que tous les personnages autour d’elle semblent soit se cacher la bouche, les yeux ou même tourner le dos. On voit même qu’un des personnages à les yeux bandés ce qui accentue l’ambiance cachotière de la scène.

4 notes

·

View notes