#alexandre walewski

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It is 4rd may.

Yesterday, I luckily discovered that on 4rd may it is Aleksander Walewski’s birthday (don’t judge me I have dyscalculia so I have a hard time remembering anything number related)

So, Happy birthday Alexander Walewski…!

+ a meme I made months ago

#drawing#aleksander walewski#alexandre walewski#walewski#polish history#traditional sketch#traditional illustration#traditional drawing#traditional art#birthday boy :3

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexandre Walewski wanting to skip Wellington’s funeral

This is an excerpt from the Greville memoirs. According to Greville, Louis Napoleon, then President of France, “ordered Walewski to attend the funeral” of the Duke of Wellington, who died in 1852.

“Count Walewski, then French Ambassador in London, expressed some reluctance to attend the funeral of the conqueror of Napoleon I [the Duke of Wellington], upon which Baron Brunnow said to him, ‘If this ceremony were intended to bring the Duke to life again, I can conceive your reluctance to appear at it; but as it is only to bury him, I don’t see you have anything to complain of.’”

————

Source: The Greville Memoirs: A journal of the reign of Queen Victoria from 1852 to 1860. Date: November 21, 1852 (google books)

#Alexandre Walewski#Charles greville#greville memoirs#Napoleon#Napoleon’s sons#napoleon bonaparte#napoleonic#walewski#Wellington#the Duke of Wellington

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Colorized Countess Elise Walewska, Granddaughter of Emperor Napoleon

Catherine "Elise" Joséphine Marie Colonna-Walewska

Elise Walewska, born on December 15, 1849 in Florence (Italy), was the eldest surviving daughter of Count Alexandre Colonna Walewski and Marie-Anne Alexandra di Ricci.

Making her the granddaughter of Emperor Napoleon and countess Maria Walewska.

When she was younger her and her siblings was the playmates of the Prince Imperial (son of Napoleon III)

In 1871, after her father had died and she lived with her mother at 9 avenue d'Antin in Paris. She married Marie Victor Félix, Count of Bourqueney, on October 9, 1871 in Paris (8th arrondissement) in the presence of Félix, Baron of Bourqueney, 75-year-old uncle of the groom, Ernest Charles Léon Leclerc, Marauis of Juiané, deputy of Sarthe, cousin of the groom, Certain François Marcelin

Canrobert, Marshal of France, and Ernest Arrighi de Casanova, Duke of Padua.

(Fun fact: the second photo is her in her First Communion dress, Photo by Ghémar Frères, carte de visite format, around 1860)

#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#alexandre Walewski#france#Alexandre colonna Walewski#napoleon’s grandchildren#Elise Walewska

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

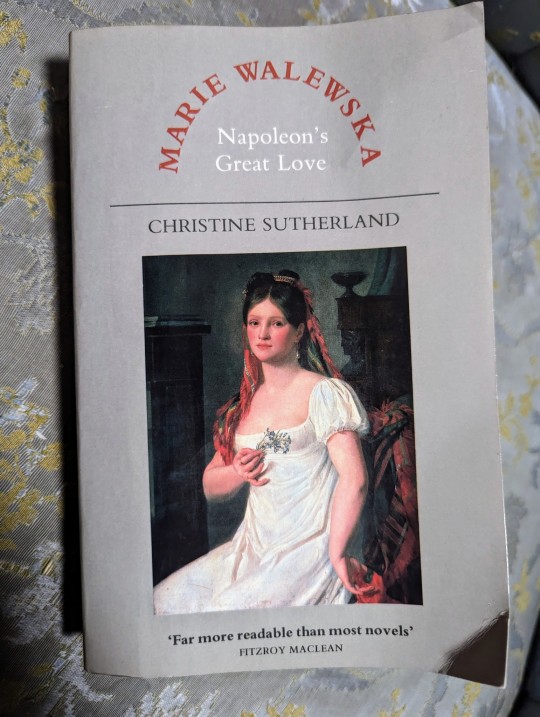

BOOK REPORT

Marie Walewska Napoleon's Great Love by Christine Sutherland was a nice break from the monotony of another giant Napoleon biography. At this point, I know how the story goes and they can get tedious at points. Yes, it was the same story but from a new and different perspective. From the views of Poland and specifically Marie Walewska, I saw a different side of the story. A country longing for Napoleon to be their savior. A young girl who hero worshipped the very man she became a mistress to.

It told of Marie's beginnings and her first marriage to the old Count Anastase Colonna Walewska, the birth of her first son Anthony, how she came to meet Napoleon, captivated him, and was encouraged to become his mistress for Poland's cause. She was reluctant at first but continued to go and see him, for Poland. It seemed that she and Napoleon were truly happy when they were together and it makes me prefer Marie over his wives and any of his other mistresses. She became pregnant and it was heartbreaking for me to read how Napoleon took such good care of her, but he was already planning his divorce from Josephine and marriage to Marie Louise, now that it was confirmed that he could father children. (He had doubts about his son with Eleonore Deneulle de la Plaigne.) Their son, Alexandre Florian Joseph was born and officially called the son of Count Walewski to prevent scandal on Marie's part. Napoleon made sure to provide for Marie and his son and even visited with them many times throughout the years, including when he was in exile on Elba. Once Napoleon was defeated and sent to St. Helena, Marie finally remarried (she had gotten a divorce, but waited until after Count Walewski died, and there was no more chance with Napoleon). She married Napoleon's cousin, Phillipe-Antione d'Ornano. They had a son, Rudolph Augusta, shortly before she died at the young age of 31. Napoleon did not learn of her death before he died.

It was a very good book and I learned a lot. Not just about Marie Walewska, but Poland as well! I would definitely recommend having some background knowledge on Napoleon before reading.

#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#Marie Walewska#book report#Poland#alexandre walewski#napoleons great love#christine sutherland

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

William C. Carter on Napoleon’s grandson Count Charles Walewski :

“Another of Marcel's superiors was company commander Captain Walewski, otherwise known as Comte Charles Colonna-Walewski, the grandson of France's most famous military genius: Napoléon Bonaparte. Walewski's father, Alexandre-Florian-Joseph Colonna, Comte Walewski, came into the world as the illegitimate son of Napoléon and his Polish lover Marie Laczynska (Walewska).

Marcel and his fellow cadets believed they saw in Captain Walewski a strong resemblance to his illustrious grandfather. Like Cholet, the count was a member of the Jockey Club, of which his father had been one of the founders. The club had been created to restore French horse breeding, after the decimation suffered during the Napoleonic Wars, to its former superior level. Proust and his fellow cadets admired Walewski's "gentle-ness (and) his politeness as a commanding officer," traits his grandfather Bonaparte might not have considered the most important for a military officer.

Marcel closely observed these two officers, each representing one of France's opposing political and historical forces: the ancient nobility, epitomized by Cholet, and the more recent nobility of the Empire represented by Walewski.”

Marcel Proust: A Life by WILLIAM C. CARTER (pages 105-106)

#French Third Republic#Charles Colonna-Walewski#spare me my obsession with Walewski descendents#they fascinate me#lol#marcel proust#alexandre walewski#napoleon#Marie Walewska

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Have you seen his son? Because the dude had sideburns (at least I think they’re sideburns)

With sideburns being so popular at the time I tried to imagine what Napoleon would look like with them. So... yeah, that is what this is.

I wonder what he thought about this trend. Seriously why was this so popular? 😐

#I surprisingly like Napoleon with sideburns for some reason#looks cute#napoleon bonaparte#Napoleon#Alexandre Walewski#Walewski

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Françoise de Bernardy’s Alexandre Walewski: The Polish son of Napoleon- the first chapter

If I went to the (long and tedious) effort of translating the first chapter of Françoise Bernardy’s 1976 biography of Alexandre Walewski, I figure you guys should see it too. Enjoy!

* * *

MARCH 1810. Paris is moved by the preliminaries of Napoleon's marriage with Marie-Louise. In a few days, the archduke Charles has to marry in Vienna, in the name of the French Caesar, his yesterday's victor, the daughter of the German Caesars.

At 2 rue du Houssaye, in the then aristocratic district of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, a small hotel of elegant appearance. On March 10, at the end of the afternoon, the Emperor brought a cradle decorated with silver laurel. The room where the imperial gift is deposited is hung with light blue. On the wall is a beautiful portrait of a woman by Gerard: blonde, with beautiful eyes and a fine, gentle face. The mirror of the fireplace reflects the charming features. Near the Boucaut armchairs, a Martin varnished chiffonier, behind, half-folded, a large screen of Coromandel lacquer.

A heroic fighter in the last wars of Polish independence, Mathieu Laczynski, staroste of Gostyn, died young and desperate, leaving a widow and six children who can barely live off the mortgaged land of Kiernozia.

The years pass, aggravating the ruin. The four sons are valiant but weak, spendthrift, covered with debts, whether they work on the land or fight in the Polish legions in the service of France. Only one hope, a rich marriage for the oldest daughter, Marie, born in 1786, who is beautiful and good.

An almost septuagenarian but very noble neighbor, Count Anastasius Walewski, offers this rich marriage when Marie has just turned seventeen. At first, the young girl rejects the idea of a union with an old man, twice widowed, whose son Stanislaus is already a made man. But Mme. Laczynska urges her daughter. She knows that he has a warm heart and a devoted soul. Count Walewski is generous. If Mary sacrifices herself, he will secure the future of her brothers and sister. How to resist seventeen years? At the beginning of 1804 Marie became countess Walewska. In June 1805 she had a son, Antoine, a fragile, weak, viable child, who was taken over by the count's sister, Hedwige, an abusive spinster. She leaves behind a distraught young woman with a sad heart and empty arms. Only the sense of duty and a deep passion, which lifts her out of herself, the love of the country, sustain her. Marie lives on the hopes that the victories of the imperial France over Austria, Prussia, and Russia, the powers that once shared Poland.

This patriotism and these hopes brought Marie Walewska to meet Napoleon in Blonie on the road to Warsaw on December 31, 1806. In the weeks that followed, this patriotism and these hopes persuaded the young woman to become the mistress of the French emperor, first forced, then willing, then in love. In the spring of 1807, she lived with him in Finckenstein, where the warrior spent some quiet hours preparing for the Friedland campaign.

Unofficially separated from her old husband, Marie Walewska came to Paris at the beginning of 1808. She remained there until the Emperor's departure for Bayonne. If the fever of the senses has subsided between them, if the lovers are often and for a long time separated, nevertheless Napoleon remains attentive and Marie attached. And then there is always Poland, whose destiny once more seems to be played out during the campaign of 1809. In May, Marie writes to Napoleon, reminds him of his promises, offers to join him in Austria, and on May 18, from Schoenbrunn, which he is about to leave for his headquarters in Ebersdorf, the Emperor replies to the young woman.

"Marie, I have received your letter. I read it with the pleasure that your memory always inspires me. The feelings that you keep for me, I carry them with me.

"Come to Vienna, I wish to see you and give you new proofs of the tender friendship I have for you. You cannot doubt the value I place on everything that concerns you. A thousand tender kisses on your beautiful hands and one on your beautiful mouth. "

A month later, back at Schoenbrunn, on June 20, fifteen days before the battle of Wagram, the Emperor sent Marie an affectionate letter.

"Dear Marie, your letters have pleased me as always. I do not approve of your having followed the [Polish] army in Cracow, but I cannot blame you.

"The affairs of Poland are restored, and I understand the anxieties you have had ... I acted, it was better than to lavish consolation on you. You don't have to thank me, I love your country and I appreciate the merits of many of your people.

"It takes more than the capture of Vienna to bring the end of the campaign. When I have finished, I will move to be closer to you, my sweet friend, because I am anxious to see you again. If it is at Schoenbrunn, we will enjoy together the charm of its beautiful gardens and we will forget all these bad days.

"Have patience and keep faith. "N"

After Wagram, Countess Walewska moved to Moedling, a few miles from Vienna, and throughout the summer of 1809, while peace was being discussed, the Emperor came almost every day to spend the evening, the night - with Marie.

Slow, sweet weeks which, if they seem to consecrate the liaison by the expectation of a child, however, by precipitating the divorce, also prepare the rupture. Indeed, Marie wishes to return to France with the Emperor, but Napoleon, now assured that he can procreate, determined to separate from Josephine, does not want to. The presence of the young woman in Paris would disturb him as he prepares his second marriage. He asked the Countess to return to Poland and on October 13 - the Emperor left Vienna the next day - Marie took the road to Warsaw.

On December 18 - the divorce was pronounced on the 15th - from Trianon where he went to his departure from the Tuileries, Napoleon writes to the countess Walewska. How the tone has changed since the letters of May and June, and how the young woman must have suffered. It is no longer a lover, but the sovereign who speaks, only the concern for the child still shines through. "Madam, I received your letter. All that it contains touched me much. I was pleased to see that you arrived in Warsaw without any unpleasant accident. Take care of your health, which is very precious to me, and put away dark thoughts, the future should not worry you. Teach me that you are happy and content, that is my greatest desire."

Unconsciousness of men. It is almost in the same terms that the Emperor tries to console Josephine...

Happy? Happy? Marie is not happy while she is waiting for Napoleon's child so far away from him, while Caulaincourt seems to be about to sacrifice the Polish hopes in Saint-Petersburg... In 1807, prince Poniatowski asked countess Walewska not to reject the sovereign on whom the fate of Poland depends. In 1810, he probably asked Marie to come to Paris to defend the cause of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and she agreed. Thus, she was in Paris at the beginning of 1810.

Marie Walewska looked sadly at the cradle. It is true that Napoleon welcomed her and spoke tenderly of the child she was carrying - a son, he had no doubt. But the young woman's heart is heavy. The Emperor had come the day before to bid her farewell. He would not see her again until she had given birth. What will Marie do? Stay in Paris? Retire to the country? To Warsaw? But can she return without the count's permission?

All of a sudden hurried footsteps, a panting courier. "A letter from Poland!"

The count's handwriting...

"Walewice, 21 February 1810

"Dear and honored wife,

"Walewice is more and more a burden to me, my age and state of health forbidding me any activity. I have come there for the last time, in order to sign the deed by which my eldest son acquires it.

"I advise you to come to an agreement with him about the formalities to be completed at the birth of the child you are expecting. They will be simplified if it is in Walewice that this Walewski is born.

"This is also his opinion, and that I write to you. I do so, conscious of fulfilling my duty, praying to God that he may have you in his care.

"Anastase Colonna Walewski".

Marie weeps with relief, with gratitude. Without wasting a minute, she claims her chaise de poste.

Poland is still under a blanket of snow when the Walewska princess arrives in Walewice. The young woman was pleased to see the long white house again, with its two wings covered by terraces and the triangular pedimented porch. This "colonial style" is surprising in the Polish plain: it is a memory of the veterans of the American War of Independence.

April soon brings its first greens, the buds burst in the woods. Marie Walewska takes long solitary walks. Her term is near. What will be the future of this child in whom Slavic and Latin blood are mixed? If it is a son, will he be a soldier, a diplomat? If it is a daughter, will she have fewer difficulties than her mother? What Marie wishes for her child is happiness...

On May 4, Countess Walewska gave birth to a son. At the end of his life Alexandre Walewski will write:

"My birth was accompanied by lightning and thunder, and it was predicted that my life would be stormy and even life-changing.

"To satisfy an old family prejudice, I was held at the font by two beggars, which was supposed to bring me luck... "

Three days pass, then on May 7 the priest of Walewice, acting as civil registrar, registers in the commune of Bielow that "Mgr Anastase de Walewski, staroste of Wareck, residing in Walewice, age of 73 years ", presented him "a child of the male sex, born in his palace on May 4 of the present year at four o'clock, by clarifying to us that he was born from his marriage with the lady Marie, nee de Laczynska, his wife . ... and that he intended to give her the following three names: Alexandre-Florian-Joseph. In view of this declaration, we have proceeded to the redaction of the birth certificate of the said child, in the presence of Mgr Stanislas de Walewski aged 30 years ... and of Mr. Joseph Ciekerski,doctor of medicine and surgeon deliverer ... which birth certificate was signed by us as well as by the above-mentioned and the required witnesses after reading made. "

Anastase Walewski thus fulfills all his duty towards a woman whose honesty and uprightness he appreciates. To this child who is nothing to him, he assures a name, a legitimate filiation, a heritage. This is a striking proof of the affection and esteem he has for Marie. Stanislaus Walewski is fully associated with this testimony by his presence in front of the priest of Walewice.

On his side the Emperor did not forget Marie.

On April 16 (1) he wrote to her:

"Madam, I receive with great pleasure your news, but the dark ideas that I see that you nourish do not suit you well. I do not want you to have any. Teach me soon that you have a beautiful boy, that your health is good and that you are cheerful. Never doubt the pleasure I will have in seeing you and the tender interest I take in what concerns you. Farewell Marie, I await with confidence your news."

(1) When it was published, this letter was dated February 16. This date hardly seems acceptable. First of all, it is clearly a reply to a distant person whom the Emperor will have "pleasure in seeing". Above all, Napoleon knew that the child was due at the beginning of May and he could not hope that he would be born "soon" - prematurely. Date of April, when the young woman withdrew to Walewice, this text takes on its full meaning.

Leaving a few days later for Belgium and Holland with Marie-Louise, he is informed by quick couriers and, as soon as he knows the birth of Alexandre, he sends for the child Brussels lace and twenty thousand gold francs, for the mother, a very special tribute if we think of Napoleon's admiration for the poet, the works of Corneille, printed in Rouen in 1648, in a beautiful binding by Trantz. Does the Emperor want to signify to Marie that she has the high and tender soul of a Chimene, that he remembers her faithful and generous love?

Napoleon called the young woman back to France on September 3. After thanking her for the news brought by her brother, Theodore Laczynski, he adds in effect: "If your health is well recovered, I desire that you come on the end of autumn to Paris where I desire very much to see you... "

An amicable agreement is then definitively reached between Marie and the count Walewski. The latter gives her a large part of his fortune and entrusts her with the custody of their son Antoine. In Paris Marie Walewska moves back to rue du Houssaye. The months pass. Marie lives far from the court, does not meet Napoleon who, all occupied with Marie-Louise, seems to be interested in the young woman and her son. Finally, in February 1811, the Emperor came to see little Alexandre. It is a beautiful blond child, but whose dark complexion recalls that of the Bonapartes. He has the round head of the Latins, the high and wide forehead of his father, his eyebrow, his mouth and his chin, but the eye does not have the deep blue of the Corsican, reflection of the Mediterranean, it does not have either the sparkle which had always to brighten in the imperial pupil, the brown eye of Alexandre is pleasant and merry. A second visit follows the first one, then it is the rupture, without clashes, without discussion, like a fruit that has reached maturity.

Napoleon, however, is very concerned about the material well-being of Countess Walewska, to whom Duroc brings ten thousand francs every month. Especially the future of his son. On the eve of leaving Paris for Russia, on May 5, 1812, he made the young woman come to the Tuileries and gave her a patent which instituted in favor of Alexandre a majorat of one hundred and seventy thousand pounds of income, with the title of count. The majorat is established on goods situated in the kingdom of Naples.

One evening in January 1813, Alexandre was awakened with a start. Dressed in a hurry, he was taken to his mother.

"Two elderly men were with him, one of whom took me on his lap and kissed me. His physiognomy made a deep impression on me; it was certainly the first memory of his life."

The Emperor's solicitude for his Polish son did not waver. In the middle of the dark hours of the French campaign, fearing that Murat would confiscate the first endowment, he charged his treasurer general, M. de La Bouillerie, to establish a new majorat of fifty thousand pounds of rent on the canals for the young Walewski; he also had a hotel at 48, rue de la Vicioire, bought in the name of Alexandre for 137,500 francs, of which Marie was the usufructuary (1).

Come the great reverses. In the defeated Emperor, abandoned by his former companions, Marie Walewska sees only the man who has loved her, whom she has loved. She runs to Fontainebleau and is announced. Napoleon, absorbed, does not see her again immediately, and then does not think about her anymore. Weary of body and soul, he looks for oblivion and rest in poison, but does not find it.

All night long, in an anteroom, Marie waits for him to call her. In the morning, she finally goes away, discreet, fearing to be unwelcome. The Emperor learns a few hours later of her apparent negligence. "The poor woman," he murmured, "will think she has been forgotten," and on April 16 he was anxious to reassure her. "Marie, I have received your letter of the 15th, the feelings that you have expressed touch me deeply. They are worthy of your beautiful soul and the goodness of your heart. When you have arranged your affairs, if you want to go to the waters of Lucca or Pisa, I will see you with great and lively interest, as well as your son for whom my feelings are invariable. Be well, think of me with pleasure and never doubt me.”

(1) On February 4, from Nogent, he writes in his own hand to La Bouillerie: "I have received your letter relative to young Walewski. I leave you carte blanche. Do what is convenient but do it immediately. What interests me is above all the child, the mother afterwards." A judgment of the court of the Seine, of April 4, 1818, will authorize the tutor of the "minor" Walewski it to sell the hotel of the rue de la Victoire and it to replace the funds produced by this sale in the purchase of Walewice of which Stanislas Walewski wants to get rid.

In August 1814 Marie Walewska travels to Italy with her son, her sister Emilie and her brother Theodore. The Emperor encouraged her again on August 9:

"Marie, I have received your letter, I have spoken to your brother. Go to Naples to arrange your affairs. On my way there or on my way back, I will see you with the interest you have always inspired in me, and the little one of whom I hear so much good news that I am truly happy and will be happy to embrace him. Farewell, Madame, a hundred tender things.”

On September 1 Marie arrived on the island of Elba with her son, Emilie and Theodore. Immediately a rumor spread among the population and the small garrison: Marie-Louise and the King of Rome had just arrived. The good people are mistaken. The Viennese woman of light soul and weak flesh is in Aix, already all in Neipperg.

Is Napoleon going to retain Marie who has come to offer him her life? Certainly he is moved to find her always so faithful and so generous. But the Emperor thinks first of the Empress, first of the King of Rome, and he fears that Marie-Louise, warned of the coming of the Polish girl, will take the pretext not to join him. Surprisingly, does he not guess that the choice is already made?

In any case, he receives Marie Walewska in a half-mystery, at the hermitage of the Madonna.

Leaving the countess the three rooms of the little house, Napoleon settles for the night in a tent under the chestnut trees. When he came out in the morning, he found Alexandre playing. He called him, sat down on a chair, took the child in his lap, then sent for Foureau de Beauregard, the doctor who had followed him to Elba, and the latter wrote to Alexandre Walewski on June 22, 1843: "You are that pretty little Alexandre that I saw, almost twenty-nine years ago, on the Emperor's lap near the Madonna delle Grazie on the island of Elba.”

“The Emperor wanted the child, who had no youngster with him, to be there," says Marchand. The Emperor placed Mme. Walewska's son next to him, he was very good at first, but it didn't last long and, as his mother reproached him, the Emperor said to him: "So you are not afraid of the whip? Well! I urge you to fear it; I have only received it once and I have always remembered it." Napoleon then tells how one day when he had mocked his grandmother's clumsy walk, Madame Mere had firmly corrected him. "The child had listened with the greatest attention, the Emperor said to him: 'Well, what do you say to that?’— ‘But I don't make fun of Mama,' he said with a little air of contrition which pleased the Emperor, who kissed him and said: 'That's well answered.’"

Rare picture of Napoleon with his Polish son.

That same evening, September 2, Marie Walewska took the road to Naples again in small steps. The endowment of Alexandre, confiscated on September 15 with all the other French endowments of the kingdom of Naples, is restored on November 30. Perhaps on the intervention of Caroline, who always liked Marie Walewska? Perhaps Murat had some shame to add a meanness to his betrayals? In any case the Emperor was satisfied and he told the King of Naples on February 17, 1815, adding: "I recommend her to you and especially her son who is very dear to me. "She came to Paris in the spring of 1838 and was ‘touched by the assiduous care’ that Walewski gave her during her stay. Caroline Murat wrote to him on November 23: "I am sending you the letter from the Emperor that I had promised you; you will see in it the proofs of the affection that he had for you... "

The countess Walewska lingers in Naples. Alexandre will keep a vague but pleasant memory of this stay, of the toys that he received there. At the beginning of 1815 the mother and the child embarked for France. Caught by a corsair, they escaped him in great difficulty.

Marie learned of the death of the count in Walewice on January 18, 1815. Now that she is free, what will she do with her life? To marry General d'Ornano, who has been courting her for a long time and for whom she has a deep inclination? Perhaps... She has hardly had time to decide when on March 1, 1815 Napoleon lands in Golfe-Juan.

It is the prestigious return, the intoxicating reception of Paris, the feverish days of work. Before the departure for the plains of Flanders where the imperial eagle will fall, Marie, always faithful heart, goes to the Elysee with her son. Alexandre found the visitor from the rue du Houssaye at the palace. He wears, as on the island of Elba, a blue uniform with a white lapel. "He told my mother that he was going to leave for a campaign. He asks me if I want to go with him. My mother refused. ‘Well madam, I will take him by force.’” These words still ring in my ears. "

Waterloo, the second abdication, the halt at Malmaison. Marie once again comes to the Emperor. So many bonds united them, gratitude for the resurrected Poland, and then love, and then the child. Without a doubt, she is ready to accompany him in this exile from which Napoleon's immense weariness, after a life so full and so ardent, awaits rest. But he does not accept, happiness is no longer for him, he enters the legend.

Despite the clear light of this beautiful summer day, everything is sad and gloomy on this June 26 and Malmaison is a kingdom of shadows: shadow of Josephine, unfaithful and charming, shadow of Duroc and Bessieres, shadow of the madman Junot, shadow of the absent ones too, Eugene, Murat, the companions of glory and youth, shadow of Talleyrand and Fouche who betrayed him, shadow above all of this young consul who took France in his arms and with a sincere effort straightened it.

Marie and the Emperor speak at length. Alexandre, serious and silent, listens to them without understanding. The countess is crying softly, she would like to retain Napoleon, to persuade him not to abandon himself to destiny. It is a vain effort, the Emperor does not hear her, nor does he hear Hortense. Marie finally decides to leave and Napoleon leans over to the child and gives him a long kiss. Later the man made, the wall man who became ambassador, then minister of the resurrected empire, will remember that he thought he saw a tear running down the cheek of the defeated of Waterloo.

Three more days the slow agony continues, three more days Marie returns to Malmaison and on June 29 she will be among the last faithful who, on the threshold of the house, will see the Emperor sinking with a firm step into the park, crossing the small gate, will hear the door of the heavy car slamming while the bells of the church of Rueil ring...

* * *

A long year... Europe catches its breath, gets used to the absence of the man who for fifteen years has dominated it and who disappeared at the bottom of the Atlantic.

On September 7, 1816 Marie Walewska married Ornano, who had been exiled by the Restoration, in St. Gudula in Brussels. Antoine and Alexandre Walewski stayed in Paris. Under the guidance of M. Carite, a friend on whom the countess entrusted the education of her children, and of an old valet, Andre, the two little ones join the Ornanos at the waters of Chaudfontaine near Liege. The new household moved soon after to Liege itself, in a charming house on rue Mandeville, today rue de la Fragnee. On June 9, 1817, a son, Rodolphe, was born. After his release from exile, Ornano returned to Paris with his wife in October 1817, but Marie died soon after, on December 11.

In her will Madame d'Ornano entrusted the guardianship of her Polish sons to her brother Theodore Laczynski, who was in Paris at the time. "He will have to report frequently to my dear husband on the state of Alexandre's health, to take his advice when this child will be of school age. Place him in a school where his father-in-law will be able to go and visit him sometimes and supervise his education... "

Laczynski takes the two orphans to Kiernozia in Poland. Alexandre likes this quiet and patriarchal life. Memories of the imperial era haunt the house. In the evening, Antoine and Alexandre linger in the living room. Theodore Laczvnski takes the lead in the conversation, he talks about the French Revolution, Paris, the imperial campaigns, especially about the Emperor. As Duroc's aide-de-camp, the Pole often approached Napoleon. The children, with bright eyes, listen "with indefinable interest". Laczynski's dream is to go to Saint Helena, to take his wards there...

After a few happy months in the country, Theodore Laczynski decides to settle in Warsaw and gives the children whose education cannot be neglected any longer a tutor. A strange choice. The times decidedly wanted it. While Queen Hortense entrusted Louis-Napoleon to the son of the conventionnel Le Bas, the young Walewskis, in their snows, were given to a certain Muller, a "philosopher teacher" as he called himself, of a very advanced republicanism. Laczynski quickly separates from the astonishing character and, in order to restore the balance, his pupils spend half a year in a Jesuit college in Warsaw, where Alexandre makes his first communion. Then they left for Geneva in 1820.

Napoleon's son stayed there for four years. After a happy, pampered life with the gentle and tender woman who was his mother, the child had two more easy years. Now here he is, thrown alone - his brother Antoine is leaving him soon (1) - in a new, even hostile environment, in a foreign city whose Protestant austerity must have clashed with the Catholic heredity of this Pole with Latin roots. And yet, as he himself wrote, it was from this period that his spiritual life began. The city of Calvin suits this calm, somewhat soft temperament. No flashes of anger or outbursts. Order, measure, a certain fundamental rigidity. In Geneva, one day in the summer of 1821, the child of Wagram, the one who prayed for the Emperor because he was his father, learns of the death of the captive of Saint Helena.

(1)Recalled probably by the tsar. Antoine Walewski died young, without children from his marriage to Constance Grotowska.

No trace in the memories of the imprisoned man of what he thought, felt... Did he ever know, except by the cold instructions to the executors of his will, that Napoleon, although absorbed by the concern for his imperial son, nevertheless thought of his Polish son, recommended him to Bertrand, expressed the wish that he enter a regiment of lancers, and above all that he become a Frenchman. "He is really of my blood, and that is also something."

Alexandre Walewski is a boarder at the Academy's rector's house, which receives about twenty young people. His lavish lifestyle, the apartment, the governor, the servant, attracted jealousy and bullying. In spite of his young age, Alexandre decides to avoid a situation which, if it goes on too long, will become painful. He gets the governor recalled, keeps the servant but puts him at the service of the community. He has easy money - his hands will always be wide open -, he lends to his comrades and shows himself to be generous. He is a serious, authoritarian boy, aware of his importance. The traits of his character, which we will find again during his life, are already marked: he is honest, upright, but he is neither cheerful nor fanciful. He evokes his life in Geneva as follows: "I was at twelve very tall for my age, and I considered myself a young man; so much so that I was already going a little into the world, to balls, to little parties... I stayed in Geneva for four years. I left Geneva on an order from the emperor of Russia."

* * *

On his return to Poland in 1824, Alexandre Walewski was emancipated by his tutor. He settled in Walewice, where he led a stately life. Princess Jablonowska, a sexagenarian cousin who had once been the friend and confidante of Maria Walewska, helped him to entertain. The house of the young man, of this so young man, is soon to be very sought after.

Precocious from a worldly point of view, Alexandre Walewski is also precocious with women. The Latin blood is hot, the Slavic blood as well. Judging by what he wrote in the first draft of his memoirs, shortly after his arrival in Walewice, Alexandre had an affair. He had an affair with a "vulgar girl" that left him feeling disgusted and that would keep him away from such promiscuity in the future. The numerous women who will mark out his life will be from now on women of talent or: women of quality.

On December 22, 1825, Alexandre sends to the General d'Ornano his wishes for the new year. This letter, green, charming, which confirms the impression of maturity of a boy who is not sixteen years old, also reveals the affectionate feelings that he feels for his stepfather.

“It is nearly three months since I wrote to you and many things have happened since I took possession of my land in Walewice. First of all, the castle was repaired, which was in great need of it, and then my good cousin wanted the whole region to hear, with loud trumpeting, that I had become its lord. More than a hundred people did us the honor of attending the magnificent ball that she gave. It was very cold outside, but fortunately there was no snow that night. I was celebrated and saw people from the past whom I pretended to recognize and who were charmed by it. The dowagers even kissed me, but not the young girls, which would have pleased me more. I made up for it by dancing with several of them.

"I must confess also that I fell several times into the sin of pride. I don't know who said anything about my academic successes, but I have been in the hot seat and have been made to take part in political, diplomatic, literary, and I don't know what else conversations. How many compliments have I heard about my intelligence, my reason, the power of my arguments, etc., etc., etc.? And then I noticed that the girls preferred me to many other dancers. As the lessons given to me were profitable, I remembered that it was especially necessary to court ladies of canonical age and they brought back to me very flattering appreciations on my modest person, expressed by exquisite mouths...

"General Zayonczek is one of my most frequent visitors... He rambles a little, but this does not affect his memory. He remembers very well all that happened in Warsaw when the Emperor came there before the battle of Eylau... He is very popular with the great Duke and even with the Czar's court. Some people criticize him, but I think it is good that we have our great men in favor. It can only be useful for us...

"We will reopen the Warsaw hotel in a few days. Ah! if we could see you there!

"Your tender and respectful Alexandre. "

Son of the patriot Marie Walewska, son of the Emperor, Alexandre attracts Polish hopes. He would gladly be taken as a standard bearer. Grand Duke Constantine, the skillful and often benevolent governor of the kingdom, wanted to neutralize him. He offers him to join the Russian army, to become his aide-de-camp. The young man "stubbornly" refused. He was put under police surveillance and told to leave the country. Tsar Alexandre had once recommended that Napoleon's Polish son should never be allowed to go to France: his brother remembered this.

Alexandre decides to escape. With a passport obtained at a high price, he goes to St. Petersburg and hides there, waiting for a favorable opportunity to gain more free land. He learns that the police are looking for him to bring him back to Warsaw where his fate will be decided. Four hundred leagues on foot, a probable prison do not tempt the Pole. He had to escape at all costs. He reached Kronstadt and boarded a steamer bound for England. The police have found his trail, and they launch an armed barge in pursuit of him, ordering him to stop: inadvertently or unwillingly, the captain does not obey the summons and, thanks to his superior speed, makes it to the open sea.

* * *

In London, Walewski received an enthusiastic welcome from the elegant society, the opposition. The Whigs, that is, the Liberals, have always regretted the treatment of the Emperor, and Lord Holland has protested in the House of Lords against the conditions of captivity. With Napoleon gone, the regrets became remorse...

In spite of the attentions of which he is the object, the young man does not linger in England. He will return there with pleasure and in 1828 he will spend several months: summer, autumn, making a long stay in Chatworth at the Duke of Devonshire, the most prominent of the great Whig lords. But it is in Paris that Walewski intends to settle down. He arrived there in the autumn of 1827. He found his father-in-law, with him Flahaut, Sebastiani, Gerard, veterans of the time. The salons of the Faubourg Saint Honore, of liberal tendency, receive him with great pleasure. He is charming at his entrance in the Parisian world, this young Walewski. Slim, slender, elegant, he has beautiful dark eyes and a dreamy smile. His slight accent adds to his charm when he courts a woman, and he waltzes divinely - like a Slav.

And then, isn't he called the natural son of Man? The Marechal de Castellane notes on November 1, 1827: "At Mme de Flahaut's, I saw for the first time a young M. Walewski, son of Mme Walewska and of the Emperor Napoleon. He has the eyes, the sound of his father's voice, he is taller than him and very well turned out (1)."

(1) Many years later Walewski pronounced the eulogy of the count of Rayneval. An old general of the Empire suddenly begins to cry. "I attended the farewell that the Emperor made to his guard at Fontainebleau and I just heard the sound of his voice.”

What is more surprising, the faubourg Saint-Germain, stronghold of the ultras, is infatuated with Walewski who becomes the darling of the "ultra-duchesses" according to Lady Morgan. Haussonville on his side confirms it to us. "The debuts of Count Walewski took place, singularly enough, under the auspices of what is most exclusive and purest in the aristocratic society of Paris. It was as if it were a watchword among the most sought-after ladies of the Faubourg Saint-Germain to give the most benevolent welcome to the young man whose features were strikingly reminiscent, but with a pleasant and gentle physiognomy, of those of a famous mask. The first of these was the one who was to be the first to be the first to be the first to be the first to be the first to be the first to be the first to be the first to be the first to be of a man who was not a man of the world. He let the most haughtiest women, those who were about to consider themselves the prettiest or the wittiest, put themselves to the expense for him, either of brilliant toilet or of beautiful spirit, each one according to the means of seduction which suited her best. Thus, every evening in the fashionable salons, there was a real race to the bell tower between a learned marquise... who affected to speak to each ambassador the language of her country and a beautiful duchess [it seems to be the duchess de Guiche] who was then in Paris the type of the sovereign elegance. Between these ladies the bets were open and the chances seemed doubtful, Walewski taking care to share equally between them his discreet attentions...”

A cloud rises however on the horizon. Pozzo di Borgo, the Russian ambassador, a Corsican who had been in the service of the tsar, pursued with a Corsican hatred all that was Bonaparte. He asks for the extradition of Walewski, this "rebel, fugitive from the Russian Empire". By order of Charles X, who doesn't like Pozzo, Villele, on the eve of leaving the ministry, refuses it. Walewski could stay in France on condition that he avoided official circles and made himself forgotten.

Life is very pleasant in these last years of the Restoration. Lady Blessington has left us a pleasant picture of the society of the time. The manners are ceremonious and the young people surround the old women with delicate attentions, whether it is a flattering silence when the beautiful ones of the past are remembered or a lively eagerness to render them small services: handkerchief, bouquet or fan picked up, shawl placed on cold shoulders. France is the paradise of old women, especially if they are witty, England is the purgatory, says the Englishwoman without ambiguity. The amorous intrigues are discreet, hidden from the public, and those whose affair is best known affect the most reserved manners. Hypocrisy perhaps, but the Parisian world takes on an air of dignity and decency.

Once a week, the women of quality open their salons to a circle of intimates who meet like-minded people every evening in a friendly house. Small closed coteries, where strangers are not admitted. For them, balls, dinners and parties in full dress. For the regulars, the amiable negligence of the half-clothes and the free, unceremonial chat. “Yesterday I went to a small party at Madame de Jumilhac's [a sister of the Duke of Richelieu] where Walewski served as my introducer," said the Pole Andre Kosmian on November 7, 1829. “Without being rich, she received three times a week the flower of the Parisian world. Her small salon is only open to ten or twelve people at a time. It is very difficult to be admitted. I owed this favor to Walewski who is the gate child of these ladies."

Walewski likes this refined society as much as he likes it. He is linked with the due de Chartres. They are tall, one dark, the other blond, they look alike and for three winters they never leave each other. Walewski also met Thiers at Madame de Flahaut's house: their friendship will never be denied. He finally met Morny, the son of Flahaut and Queen Hortense. "They are both of distinguished and graceful manners, without support, gifted with an air as it should be which is in them as a native gift... "

Lady Blessington, a very good judge, noted in 1829: "The more I see Count Walewski, the more I like him. He has the spirit, intuition and perfect manners. I have always considered it a good sign for a young man to like the society of old people and Count Walewski marks the preference for men of age to be his father."

When the count d'Orsay and the due de Guiche create in 1828 the circle of the Union, Walewski joins one of the first. He found there many Englishmen, Lord Granville, the English ambassador who had married a sister of the Duke of Devonshire and whose son was to be a minister in 1852. Caradoc, the future opponent of Walewski in La Plata, Normanby. He also met Talleyrand... There is a lot of talk about horses, it is a passion of the time and also a fashion. The races begin to be very popular at the Champ-de-Mars and at the Bois de Boulogne. Walewski goes there with assiduity. He runs and plays...

“In the meantime, I attended horse races for the first time in my life," Kosmian said in November 1829. Unfortunately, they ended in a way that was unpleasant for Walewski, because Walewski was always doing crazy things, throwing money out of the window. In England and here in Paris, he lost at cards up to a hundred thousand francs. Having stopped on the slope, he no longer plays cards, but, which amounts to the same thing, he plays at the races. There is a very rich Englishman here, Lord Seymour [Milord l'Arsouille], who lives only for horses and for whom betting on races is a passion. He is the one who is constantly pestering poor Walewski. Last Saturday, they had only two, each on his own horse. Walewski rode an English racehorse; Seymour a hunting horse; but Walewski had to carry sixty pounds more! Everyone who knew anything about racing said in advance that Walewski was making a fool of himself and that he would lose. He wouldn't listen to anyone - and lost. The stake was five thousand francs. He has seventy-five thousand pounds of income; what a comfortable and pleasant life he could lead. Perfectly well seen in the world, universally loved... But one has to tell him the truth... he doesn't want to hear anything until now. It is a great pity because what a good and noble nature it is and of how much pleasure in society ... "

The year 1829 had been cheerful, the beginning of the year 1830 is not less. On February 9 a great masked ball was organized by Mrs. Alexandre de Girardin in the concert hall of the rue Taitbout. Mme. Alfred de Noailles intrigues during one hour Rodolphe Apponyi, the king of the cotillion leaders; on the other hand, he recognizes at first sight the princess of Lieven and both of them go in the box of Walewski so that they intrigue their turn.

Alexandre is twenty years old on May 4, 1830. He is a man. Will he continue to waste his life in frivolity, thinking only of the world, of women, of races, of gambling? Does he forget the hopes cherished by his mother, does he remember that his father wanted him to be a soldier? Will he, who is free, get bogged down in the pleasures of Paris like the Duke of Reichstadt, he who is a prisoner, in the soft life of Austria? Will the sons of Napoleon be only dandies?

Walewski was a calm observer of the Three Glorious Years, and the return of the tricolor flag, which his father had flown in Vienna, Berlin and Moscow, did not arouse any echo in him. Polish by mother, Polish by heart, Polish by nationality if not by language (1), only the tocsin of Warsaw is going to move him, to awaken him suddenly.

(1) Walewski was not fluent in Polish. Joseph Tanski tells that when he came to London in 1854 to talk to the ambassador about projects he did not wish to see revealed, he offered to speak Polish to Walewski, the valet being present in the room. The latter refused, admitting that he could not sustain the conversation.

#alexandre walewski#marie walewska#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#polish history#francoise bernardy#long post#translation#joachim murat#caroline bonaparte#d'ornano

69 notes

·

View notes

Note

Did Napoleon have an illegitimate children? I remember reading somewhere that he had an illegitimate son that had children. Is this true?

Oh yes he did.

Here’s a brief summery of them:

1. Count Leon--He is the son of Elenore Denuelle who is mentioned being a person in the household of Caroline, Napoleon’s sister. Caroline played match-maker in order to try to prove Napoleon was able to father children and to get Josephine out of the way. This wasn’t some grand love affair, more like an experiment to see if she could get pregnant.. She did. There has been some speculation that the child could have been Murat’s as apparently he was also “seeing” her. However, Napoleon accepted the child as his own, made him a count and it’s said that as he grew he resembled Napoleon. He turned out to be a bit of a scoundrel, had a huge gambling problem and would pester his cousin, Napoleon III, for payment of his debts and other things.

2. Alexandre Walewski--He is the son of Napoleon’s love affair with Marie Walewska, nicknamed Napoleon’s “Polish Wife”. They met during Napoleon’s campaign through Poland, she started out as a patriot who had a bit of hero worship of Napoleon and was begging him to help free Poland. Napoleon made promises to that he never followed through on. He immediately wanted her for his mistress, she balked because she was already married to Count Walweski who was several decades older than her (she was 18 and he was maybe in his 60s pushing 70s). They also had a son together AND she was also Catholic. However, Napoleon pursued her, conquered her, and she seemed to fall genuinely in love with him. She followed him around and was eventually installed in Napoleon’s and Josephine’s first home in Paris. Count Walweski accepted the son as his own, he knew of the affair and seems to have even given it his blessing. Alexandre grew up in Poland in the Walewski family. Marie married a distant cousin of the Bonapartes, a man named Ornano and died before Napoleon after giving birth to her third son from kidney failure. Alexandre would join Napoleon III’s cabinet as a minister of foreign affairs and later minister of state. Ironically, he was friendly with Wellington and walked in his funeral representing France. He did resemble his father, was said to have Napoleon’s voice and never really seemed to care about his father’s “greatness”. A famous anecdote says that one woman stopped him at a reception and said “I knew your father, he was a great man!” And Alexandre replied “Oh, I did not know that you were acquainted with the late Count Walewski.” He had several different orders and was created a duke. He married twice, first to the daughter of the English Earl of Sandwich who died, later to Mlle. Ricci who also apparently was a mistress to Napoleon III.

3. Madame Pellapra (?) This woman claimed to be the daughter of Napoleon and there are historians who both acknowledge that she is and other’s that don’t seem to think the claim is legit.

4. Napoleone Montholon: There is some strong evidence that Napoleon took Montholon’s wife, Albine, as mistress on Saint Helena. She did become pregnant on the island and had a daughter whom she named Napoleone.

There of course could be others that went unrecorded.

Here is a link to a post I did on the Walewski branch of Napoleon’s decendants.

https://napoleondidthat.tumblr.com/post/176541583836/napoleons-descendants-walewski-family

#napoleon#bonaparte#Napoleon Bonaparte#Emperor Napoleon#Emperor Napoleon I#Emperor Napoleon Ier#Napoleon Ier#Napoleon I#Napoleon's children#Bonaparte family#Bonaparte Clan#Alexandre Walewski#Marie Walewska#Elenore Denuelle#Count Leon#Madame Pellapra#Napoleone Montholon#Albine Montholon#Napoleon's mistresses#NDT#napoleon did that tumblr#napoleondidthat#Napoleon question#question#Napoleon mail#I love mail#mail#send me mail

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

i uh, i have some more school doodles

i failed my test and i cried but then i remembered wow i have death french people in my life this is great

cooking mama more like cooking marshal haha get it cause haha he's like like he likes baking and stuff haha nevermind

how would we forget ab the time murat fell asleep and woke up to being a flower pot

old horny gentleman

napoleon's cool bastard!

the not so cool napoleon's bastard (he looks stupid cause he is) and thats it goodbye

#yes i am straight up bullying myself#marshal soult#jean de dieu soult#marshal murat#joachim murat#napoleon iii#alexandre colonna walewski#charles leon denuelle#school doodles

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

What’s hilarious about Alexandre Walewski is even before the DNA Evidence of his descendants in recent times proving he was the son of Napoleon, most historians throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries never doubted or said “well he was the rumored” , nah everyone’s like yeah it’s his son.

Even when Alexandre tried to keep up the facade that Athanasius was his real father. Him being Napoleon’s son must of been an huge open secret. Like everytime he was asked about it he would wink at the camera. lol

Napoleon just ctrl+c ctrl+v’s his genes, huh?

#also him being mentioned in napoleons will twice#and he gives lands money and titles to the random polish boy who so happens to be son of your polish wife/mistress#and he looks just like you more than your legitimate son#too many coincidences lol#napoleon bonaparte#alexandre colonna walewski

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh boy i feel so active lately!

Drew this depressed-looking guy. Hope you all Aleksander Walewski enjoyers enjoy this.

If you don’t know who this guy is… idk check the info on internet if you want, because I don’t want to info dump here.

He’s just a sad guy. Very sad guy. At least that’s what he looks like in most photos.

(he’s sad because i called him dumb. Sorry Walewski)

#drawing#sketch#alexandre walewski#aleksander walewski#walewski#shitpost drawing#??? i think#traditional drawing#my art#my artwork#historical art

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

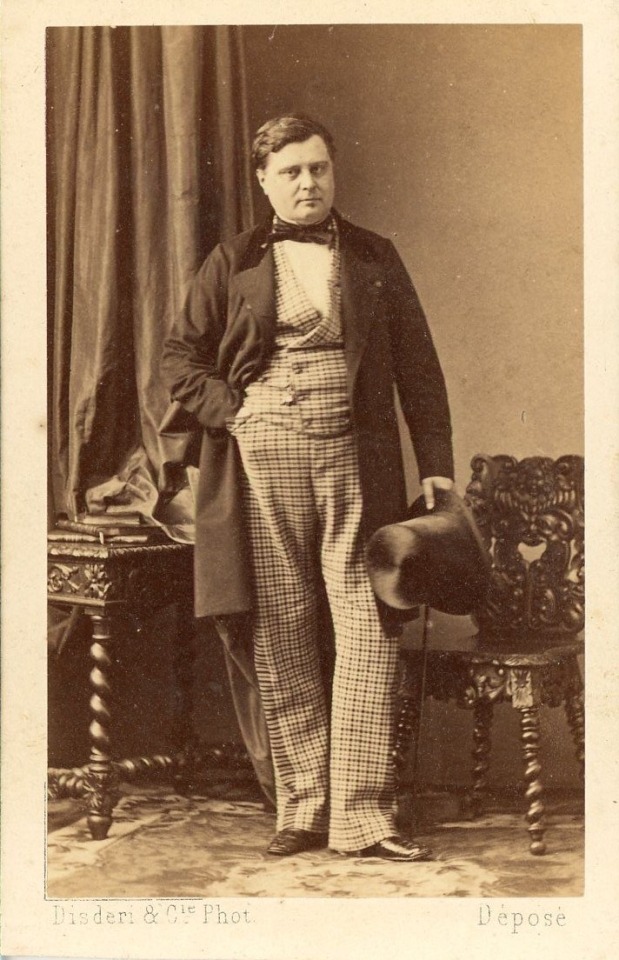

Checkered suit, bow tie, top hat, right hand in pocket, coat pushed back seductively, showing off handy-dandy pocket watch, walking cane ready.

He was thriving, glowing.

#Alexandre walewski#walewski#Napoleon’s son#Napoleon’s children#vintage photo#19th century#19th century photography#france#2nd empire#second empire#second french empire#napoleon iii#Napoleon’s sons

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Different Portrayal’s of Napoleon’s Son Alexandre Walewski on screen.

-Conquest 1937

-Sacha Guitry’s Napoleon

--La caméra explore le temps" Marie Walewska

#napoleon#Napoleon’s sons#napoleon’s children#alexandre colonna walewski#Marie Walewska#napoleonic era

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charles Léon Denuelle in his later years

Napoleon’s first-born child, Léon Denuelle, died at Pontoise, northwest of Paris, on April 14, 1881, age 74, of stomach or bowel cancer. He was buried in a pauper’s grave in the local cemetery, marked with a black wooden cross. His remains were later dug up to make room for others. He has living descendants.

For details of Léon’s life, see “Napoleon’s Illegitimate Children: Léon Denuelle & Alexandre Walewski.”

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bust Napoleon and Relatives

1805 Napoleon bronze bust by Italian sculptor Lorenzo Bartolini

Bust of Pauline Bonaparte by Antonio Canova

Bust of Joseph Bonaparte by Antonio Canova

Letizia Bonaparte Sculpture by Antonio Canova

Bust of Caroline Bonaparte by Antonio Canova

Bust of the Duke of Reichstadt Napoleon II by Pietro Tenerani

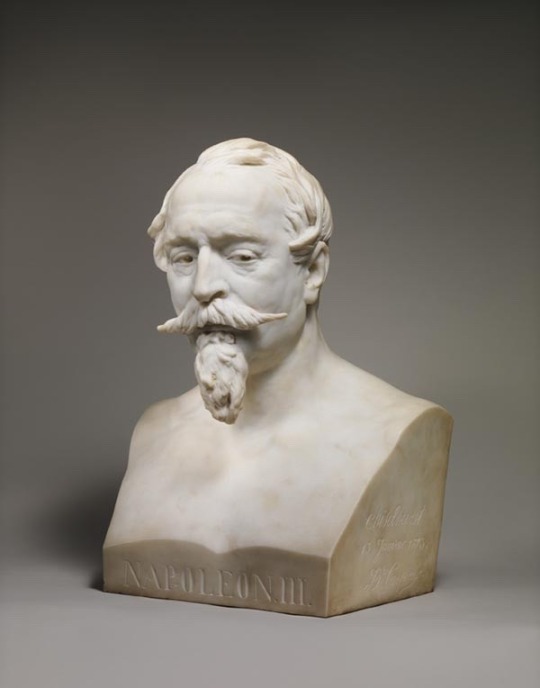

Bust of Count Alexander Colonna Walewski I by Jean-Auguste Barre 1852

Bust of Napoleon III 1873-1874, BY JEAN-BAPTISTE CARPEAUX

Bust of Prince Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux 1864

Bust of Count Alexandre Colonna Walewski II as a child by Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse.

#napoleon bonaparte#first french empire#second french empire#pauline bonaparte#Caroline Bonaparte#joseph bonaparte#duke of reichstadt#napoleon ii#alexandre walewski#napoleon iii#Louis-Napoléon#neoclassical

0 notes

Photo

Wow! He really did look like his dad

Alexandre Colonna-Waleski

From a Polish website:

Choć z urody podobieństwo do Napoleona było wręcz uderzające, i wszyscy wiedzieli kim był przodek Aleksandra, ten do końca życia obruszał się na uwagi, jakoby to nie szambelan Anastazy Walewski z Walewic był jego prawowitym ojcem.

**

Although the resemblance to Napoleon was striking in terms of beauty and everyone knew who Alexandre’s ancestor was, Alexandre was indignant until the end of his life that it was not the chamberlain, Anastazy Walewski from Walewice, who was his rightful father.

http://phw.org.pl/syn-napoleona-w-powstaniu-listopadowym/

16 notes

·

View notes