#also my decision to write class of 2004 was 10% because the show ended in 2004 and 90% because i was the kindergarten class of 2004 🥰

Text

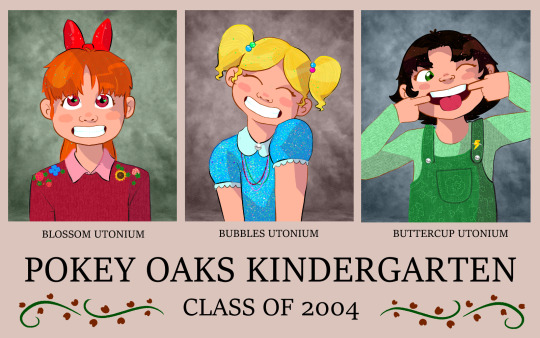

✨ School pictures ✨

#ppg#not ml#Powerpuff girls#мой рисунок#мой пост#their names are so ridiculous. these girls never stood a chance at normalcy#anyway i feel like blossom is that kind of person who has a really pretty candid smile#but the second she notices someone taking a picture it turns into 😬😬😬#and buttercup has mastered the art of using super speed to make a funny face in the fraction of a second when the camera takes a picture#this was so much fun to draw. but i deeply apologize that every time i draw some actual good fanart it's for something other than ml 😭😂😭#also my decision to write class of 2004 was 10% because the show ended in 2004 and 90% because i was the kindergarten class of 2004 🥰#the powerpuff girls

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Movies I watched in May

Sadly, I kind of skipped writing a post for April. It was a mad month with so much going on: lots of emails sent and lots of stress. I started a new job so I’m getting to grips with that... and even then, I still watched a bunch of movies. But this is about what I watched in May and, yeah… still a bunch.

So if you’re looking to get into some other movies - possibly some you’ve thought about watching but didn’t know what they were like, or maybe like the look of something you’ve never heard of - then this may help! So here’s every film I watched from the 1st to the 31st of May 2021

Tenet (2020) - 8/10

This was my third time watching Christopher Nolan’s most Christopher Nolan movie ever and it makes no sense but I still love it. The spectacle of it all is truly like nothing I’ve ever seen. I had also watched it four days prior to this watch also, only this time I had enabled audio description for the visually impaired, thinking it would make it funny… It didn’t.

Nomadland (2020) - 6/10

Chloé Zhao’s new movie got a lot of awards attention. Everyone was hyped for this and when it got put out on Disney+ I was eager to see what all the fuss was about. Seeing these real nomads certainly gave the film an authenticity, along with McDormand’s ever-praisable acting. But generally I found it quite underwhelming and lacking a lot in its pacing. Nomadland surely has its moments of captivating cinematography and enticing commentary on the culture of these people, but it felt like it went on forever without any kind of forward direction or goal.

The Prince of Egypt (1998) - 6/10

I reviewed this on my podcast, The Sunday Movie Marathon. For what it is, it’s pretty fun but nowhere near as good as some of the best DreamWorks movies.

Chinatown (1974) - 8/10

What a fantastic and wonderfully unpredictable mystery crime film! I regret to say I’ve not seen many Jack Nicholson performances but he steals the show. Despite Polanski’s infamy, it’d be a lie to claim this wasn’t truly masterful.

Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) - 8/10

Admittedly I was half asleep as I curled up on the sofa to watch this again on a whim. I watched this with someone who demanded the dubbed version over the subtitled version and while I objected heavily, I knew I’d seen the movie before so it didn’t matter too much. That person also fell asleep about 20 minutes in, so how pointless an argument it was. Howl’s Moving Castle boasts superb animation, the likes of which I’ve only come to expect of Miyazaki. The story is so unique and the colours are absolutely gorgeous. This may not be my favourite from the legendary director but there’s no denying its splendour.

Bāhubali: The Beginning (2015) - 3/10

The next morning I watched some absolute trash. This crazy, over the top Indian movie is hilarious and I could perhaps recommend it if it weren’t so long. That being said, Bāhubali was not a dumpster fire; it has a lot of good-looking visual effects and it’s easy to see the ambition for this epic story, it just doesn’t come together. There’s fun to be had with how the main character is basically the strongest man in the world and yet still comes across as just a lucky dumbass, along with all the dancing that makes no sense but is still entertaining to watch.

Seven Samurai (1954) - 10/10

If it wasn’t obvious already, Seven Samurai is a masterpiece. I reviewed this on The Sunday Movie Marathon podcast, so more thoughts can be found there.

Red Road (2006) - 6/10

Another recommendation on episode 30 of the podcast. Red Road really captures the authentic British working class experience.

Before Sunrise (1995) - 10/10

One of the best romances put to film. The first in Richard Linklater’s Before Trilogy is undoubtedly my favourite, despite its counterparts being almost equally as good. It tells the story of a young couple travelling through Europe, who happen to meet on a train and spend the day together. It is gloriously shot on location in Vienna and features some of the most interesting dialogue I’ve ever seen put to film. Heartbreakingly beautiful.

Tokyo Story (1953) - 9/10

This Japanese classic - along with being visually and sonically masterful - is a lot about appreciating the people in your life and taking the time to show them that you love them. It’s about knowing it’s never too late to rekindle old relationships if you truly want to, which is something I’ve been able to relate to in recent years. It broke my heart in two. Tokyo Story will make you want to call your mother.

Before Sunset (2004) - 10/10

Almost a decade after Sunrise, Sunset carries a sombre yet relieving feeling. Again, the performances from Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke take me away, evoking nostalgic feelings as they stroll through the contemporary Parisian streets. There is no regret in me for buying the Criterion blu-ray boxset for this trilogy.

Before Midnight (2013) - 10/10

Here, Linklater cements this trilogy as one of the best in film history. It’s certainly not the ending I expected, yet it’s an ending I appreciate endlessly. Because it doesn’t really end. Midnight shows the troubling times of a strained relationship; one that has endured so long and despite initially feeling almost dreamlike in how idealistically that first encounter was portrayed, the cracks appear as the film forces you to come to terms with the fact that fairy-tale romances just don’t exist. Relationships require effort and sacrifice and sometimes the ones that truly work are those that endure through all the rough patches to emerge stronger.

The Holy Mountain (1973) - 10/10

Jodorowsky’s masterpiece is absolute insanity. I talked more about it on The Sunday Movie Marathon podcast.

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) - 10/10

Another watch for Grand Budapest because I bought the Criterion blu-ray. As unalterably perfect as ever.

Blue Jay (2016) - 6/10

Rather good up to a point. My co-hosts and I did not agree on how good this movie was, which is a discussion you can listen to on my podcast.

Shadow and Bone: The Afterparty (2021) - 3/10

For what it’s worth, I really enjoyed the first season of Shadow and Bone, which is why I wanted to see what ‘The Afterparty’ was about. This could have been a lot better and much less annoying if all those terrible comedians weren’t hosting and telling bad jokes. I don’t want to see Fortune Feimster attempt to tell a joke about oiling her body as the cast of the show sit awkwardly in their homes over Zoom. If it had simply been a half hour, 45 minute chat with the cast and crew about how they made the show and their thoughts on it, a lot of embarrassment and time-wasting could have been spared.

Wadjda (2012) - 6/10

Another recommendation discussed at length on The Sunday Movie Marathon. Wadjda was pretty interesting from a cultural perspective but largely familiar in terms of story structure.

Freddy Got Fingered (2001) - 2/10

A truly terrible movie with maybe one or two scenes that stop it from being a complete catastrophe. Tom Green tried to create something that almost holds a middle finger to everyone who watches it and to some that could be a fun experience, but to me it just came across as utterly irritating. It’s simply a bunch of scenes threaded together with an incredibly loose plot. He wears the skin of a dead deer, smacks a disabled woman over and over again on the legs to turn her on, and he swings a newborn baby around a hospital room by its umbilical cord (that part was actually pretty funny). I cannot believe I watched this again, although I think I repressed a lot of it since having seen it for the first time around five years ago.

The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn - Part 1 - (2011)

I have to say, these movies seem to get better with each instalment. They’re still not very good though. That being said, I’m amazed at how many times I’ve watched each of the Twilight movies at this point. This time around, I watched Breaking Dawn - Part 1 with a YMS commentary track on YouTube and that made the experience a lot more entertaining. Otherwise, this film is super dumb but pretty entertaining. I would recommend watching these movies with friends.

Solaris (1972) - 8/10

Andrei Tarkovsky’s grand sci-fi epic about the emotional crises of a crew on the space station orbiting the fictional planet Solaris is much as strange and creepy as you might expect from the master Russian auter. I had wanted to watch this for a while so I bought the Criterion blu-ray and it’s just stunning. It’s clear to see the 2001: A Space Odyssey inspiration but Solaris is quite a different beast entirely.

Jaws (1975) - 4/10

I really tried to get into this classic movie, but Jaws exhibits basically everything I don’t like about Steven Spielberg’s directing. For sure, the effects are crazily good but the story itself is poorly handled and largely uninteresting. It was just a massive slog to get through.

Darkman (1990) - 6/10

Sam Raimi’s superhero movie is so much fun, albeit massively stupid. Further discussion on Darkman can be found on episode 32 of The Sunday Movie Marathon podcast.

Darkman II: The Return of Durant (1995) - 1/10

Abysmal. I forgot the movie as I watched it. This was part of a marathon my friends and I did for episode 32 of our podcast.

Darkman III: Die Darkman Die (1996) - 1/10

Perhaps this trilogy is not so great after all. Only marginally better than Darkman II but still pretty terrible. More thoughts on episode 32 of my podcast.

F For Fake (1973) - 8/10

Rewatching this proved to be a worthwhile decision. Albeit slightly boring, there’s no denying how crazy the story of this documentary about art forgers is. The standout however, is the director himself. Orson Welles makes a lot of this film about himself and how hot his girlfriend is and it is hilarious.

The Mitchells vs. The Machines (2021) - 4/10

More style over substance, Sony’s new animated adventure wants so much to be in trend with the current internet culture but it simply doesn’t understand what it’s emulating. There’s a nyan cat reference, for crying out loud. For every joke that works, there are about ten more that do not and were it not for the wonderful animation, it simply wouldn’t be getting so much praise.

Taxi Driver (1976) - 10/10

The first movie I’ve seen in a cinema since 2020 and damn it was good to be back! I’ve already reviewed Taxi Driver in my March wrap-up but seeing it in the cinema was a real treat.

Irreversible (2002) - 8/10

One of the most viscerally horrendous experiences I’ve ever had while watching a movie. I cannot believe a friend of mine gave me the DVD to watch. More thoughts on episode 32 of The Sunday Movie Marathon podcast. Don’t watch it with the family.

The Golden Compass (2007) - 1/10

I had no recollection of this being as bad as it is. The Golden Compass is the definition of a factory mandated movie. Nothing it does on its own is worth any kind of merit. I would say, if you wanted an experience like what this tries to communicate, a better option by far is the BBC series, His Dark Materials. More of my thoughts can be found in the review I wrote on Letterboxd.

Antichrist (2009) - 8/10

Lars von Trier is nothing if not provocative and I can understand why someone would not like Antichrist, but I enjoyed it quite a lot. After watching it, I wrote a slightly disjointed summary of my interpretations of this highly metaphorical movie in the group chat, so fair warning for a bit of spoilers and graphic descriptions:

It's like, the patriarchy, man! Oppression! Men are the rational thinkers with big brains and the women just cry and be emotional. So she's seen as crazy when she's smashing his cock and driving a drill through his leg to keep him weighted down. Like, how does he like it, ya know?

So then she mutilates herself like she did with him and now they're both wounded, but the animals crowd around her (and the crow that he couldn't kill because it's Mother nature, not Father nature, duh). Then he kills her, even though she could've killed him loads of times but didn't. So it's like "haha big win for the man who was subjected to such horrific torture. Victory!"

And then all the women with no faces come out of the woods because it's like a constant cycle.

Manchester By The Sea (2016) - 6/10

Great performances in this super sad movie. I can’t say I got too much out of it though.

Roar (1981) - 9/10

Watching Roar again was still as terrifying an experience as the first time. If you want to watch something that’s loose on plot with poor acting but with real big cats getting in the way of production and physically attacking people, look no further. This is the scariest movie I’ve ever seen because it’s all basically real. Cannot recommend it enough.

Eyes Without A Face (1960) - 8/10

I’m glad I checked this old French movie out again. There’s a lot to marvel at in so many aspects, what with the premise itself - a mad surgeon taking the faces from unsuspecting women and transplanting them onto another - being incredibly unique for the time. Short, sweet and entertaining!

Se7en (1995) - 10/10

The first in a David Fincher marathon we did for The Sunday Movie Marathon, episode 33.

Zodiac (2007) - 10/10

Second in the marathon, as it was getting late, we decided to watch half that evening and the last half on the following evening. Zodiac is a brilliant movie and you can hear more of my thoughts on the podcast (though I apologise; my audio is not the best in this episode).

Gone Girl (2014) - 10/10

My favourite Fincher movie. More insights into this masterpiece in episode 33 of the podcast.

Friends: The Reunion (2021) - 6/10

It was heartwarming to see the old actors for this great show together again. I talked about the Friends reunion film at length in episode 33 of my podcast.

Wolfwalkers (2020) - 10/10

I reviewed this in an earlier post but would like to reiterate just how wonderful Wolfwalkers is. If you get the chance, please see it in the cinema. I couldn’t stop crying from how beautiful it was.

Raya and The Last Dragon (2021) - 6/10

After watching Wolfwalkers, I decided I didn’t want to go home. So I had lunch in town and booked a ticket for Disney’s Raya and The Last Dragon. A child was coughing directly behind me the entire time. Again, I reviewed this in an earlier post but generally it was decent but I have so many problems with the execution.

The Princess Bride (1987) - 9/10

Clearly I underrated this the last time I watched it. The Princess Bride is warm and hilarious with some delightfully memorable characters. A real classic!

The Invisible Kid (1988) - 1/10

About as good as you’d expect a movie with that name to be, The Invisible Kid was a pick for The Sunday Movie Marathon podcast, the discussion for which you can listen to in episode 34.

Babel (2006) - 9/10

The same night that I watched The Invisible Kid, I watched a masterful and dour drama from the director of Birdman and The Revenant. Babel calls back to an earlier movie of Iñárritu’s, called Amores Perros and as I was informed while we watched this for the podcast, it turns out Babel is part of a trilogy alongside the aforementioned film. More thoughts in episode 34 of the podcast.

Snake Eyes (1998) - 1/10

After feeling thoroughly emotionally wiped out after Babel, we immediately watched another recommendation for the podcast: Snake Eyes, starring Nicolas Cage. This was a truly underwhelming experience and for more of a breakdown into what makes this movie so bad, you can listen to us talk about it on the podcast.

#may#movies#wrap-up#film#follow for more#Twitter: @MHShukster#tenet#nomadland#the prince of egypt#chinatown#howl's moving castle#bahubali: the beginning#seven samurai#red road#before sunrise#tokyo story#before sunset#before midnight#the holy mountain#the grand budapest hotel#blue jay#shadow and bone#shadow and bone: the afterparty#wadjda#freddy got fingered#the twilight saga: breaking dawn - part 1#solaris#jaws#darkman#darkman ii: the return of durant

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview: Tim Kinsella (2012)

In 2012 my life was chaotic. I was working on my degree at Wayne State University and working two jobs. I was also going through some trauma in my personal life, which I’ve only recently sorted out. During all of this, I interviewed one of my favorite artists. Tim Kinsella has been a part of numerous musical projects (most notably Cap N’ Jazz and Joan of Arc). I was lucky enough to interview him when he did a limited run of living room shows at the time. I wrote an article from the interview for my college newspaper. I really don’t like how it turned out. This interview appears on another Tumblr page I made at the time and have since forgotten all the login stuff (including the email). Joan of Arc recently concluded after over 20 years, so I thought it would be fitting to post it again with a bit of light editing. The interview happens at a creative high for JOA and a commercial low. Kinsella currently performs in Good Fuck.

What made you want to tour living rooms?

It was really a very practical decision. I’ve been working as an adjunct teacher around Chicago and I have a better job that starts in February. I didn’t want to go back to my old job yet and get lots of music done. But by the time I found out I wasn’t working it was too late. It was too late to book clubs; to do a normal tour. It was very much just a backwards kind of a panic. Dave Bazan of Pedro the Lion and Tim Kasher have been doing this. So I got hooked up with the guys who booked those. And I’m excited this is the first one.

What subject and where did you teach?

I taught two semesters at the Art Institute [of Chicago] teaching a weird first year seminar. I taught classes on Utopia that I made up. But that’s just while I was in school there. But then I taught at Harold Washington, which is part of the Chicago City colleges, and I taught popular culture and mass media studies sorts of things. In February I start teaching experimental fiction writing at the University of Chicago’s night school program. That’ll be more exciting for me, teaching writing classes.

Are you going to write a follow up the “Karaoke Singers Guide to Self Defense”?

You know I just finished the second one and I can’t find a publisher. I actually just finished a first draft of the third one in the last two and a half months. So that means it’s still about two and a half years away from being done. I sent out the second one to 28 different publishers and have gotten 12 or 13 rejections so far and haven’t heard back from the other 14.

Why not put it out with the last publisher?

That’s part of there deal they don’t do two books by anyone. Half the people they put books out by have deals with bigger publishers, so this is like their weird side project thing. So they’re helping me find people to send it to. And I’ve become really good friends with them. So they’re on my side but they won’t do the book.

I saw in another interview that you were starting to move away from song-based albums to larger instrumental pieces. On the new self-titled album there is one side devoted to song-based material. Do you see yourself continuing to move away from that in the future or is it kind of up in the air in terms of Joan of Arc?

It’s hard to say. I remember when Joan of Arc Dick Cheney Mark Twain came out in 2004 and, when we finished mixing it, we met this friend of mine who’s in this band called Disappears, who’re really awesome, and telling him how excited I was about the record and gushing about how it does this and it does this and how we balanced it’s so crazy. He was nodding along patiently and he was like ‘you know it sounds like you just described the first Joan of Arc record to me.’ And I went ‘oh…right. I guess so’ But I don’t know I feel like I’m getting better at the craft of song writing. They’re very separate disciplines in my mind; song writing and playing music. I feel like I’m getting better at both, but they’re definitely separate disciplines in my mind.

Does it feel strange doing very different things under the same banner?

Yeah, from my perspective it’s very unified. Ideally, it should have contradictions. I don’t know. Have you ever seen a really depressing movie or read a really fun book and think ‘oh man I want to make something like that.’ That never lets up or never goes one way or the other. Realistically, I’m sad a lot of the time and I’m funny a lot of the time.

You wouldn’t want to box it in or anything?

If it’s going to representative then it needs to be multi- dimensional. So I’m comfortable with it. I understand it’s hard to sell. And at the same time when I feel like I’m getting better at these things, but the business aspect of it has never been worse. Our audience is shrinking and shrinking as I get better and better at what I mean to do.

Were any of the east coast shows canceled due to hurricane Sandy?

I guess I’m doing them. I’ve talked to all the hosts. There was one show at a friend of mine’s house in New Jersey that we moved to Brooklyn anyways so we could sell more tickets there. His street was destroyed but that show was canceled anyways. The only show that would’ve been canceled was already canceled…so it might be weird getting in and out of places…but I don’t know. Yeah I’ve been in contact with all of them and they’ve said ‘no you have to do it everything’s fine.’ I guess it’ll go neighborhood to neighborhood.

Are you going to make another film after Orchard Vale?

It’s a thing I think about a lot. Both novels started as script ideas. I found I have an easier time realizing the thing when it was just me, a laptop and a notebook. The movie was very frustrating. It didn’t turn out like I hoped it would. The tension of it ended my marriage because me and my ex-wife made it together. My girlfriend now is an experimental filmmaker and she’s really great, so we collaborate on some little things. I’ve done some music for a couple of her films and we’re constantly talking through ideas, but I don’t think…I mean I would love to, it would be my dream.

What made you want to soundtrack the Passion of Joan of Arc film?

This festival asked us to do something, it could be whatever we wanted. But they wouldn’t tell us how much money they had. They said ‘well how much do you guys want?’ Well for this little bit of money we’ll improvise to a 10-minute experimental film, for a lot of money we’ll do an original score to the Joan of Arc movie. It just popped out of my mouth. I didn’t think about it. They said ‘oh that sounds cool let’s try that.’ The one time we preformed it was in an old church this old church that was really perfect. There were stained glass windows, some people sitting in pews and a big pipe organ sitting to the side. We tried riding with the pipe organ, but we couldn’t get things in tune with it. The a-lot-of-money turned out to be very little money considering the amount of time we had to put into it. They called my bluff.

How much did the film influence the band name? Did it feel like it was coming full circle to do that?

It did feel great to do that. My relationship with the name Joan of Arc has gone back and forth a few times over the years. At first we thought it was a good idea because we wanted this familiar thing. Then there were some years where I was like this is a stupid band name, why are we stuck with this? It felt like claiming it as our own. I mean obviously it belongs to everyone. Our original idea was Sony. But our first label wouldn’t let us be named that. We just wanted a name that everybody knew that we could change the meaning of the name to certain people.

How’s the Owls reunion going?

It’s going great. It’s really fun. It took us a really long time to get momentum Sam [Zurick] moved back to Chicago last Valentine’s day. He was living on my couch so he needed to find a job and had to find a place. Then my brother had a second baby. I think we wrote the whole record twice and threw it away. It just wasn’t working. It had been 12 years since we all played together even though all of us play in Joan of Arc some of the time. Now we finally have momentum. We have enough songs where we’re throwing songs away. I think if we had to record next week we could but we’re waiting until the spring because we’re enjoying playing together and not tweaking things or making it a public thing right now. It’s fun for us to cultivate.

Did you plan to release three albums in a year? Is it hard to do that or is it more of a natural process?

No we’re totally backlogged right now, the labels hate us. Two years ago we did 113 shows we were all just miserable and exhausted. So we were like OK let’s stay at home and figure things out. It was a good year we all enjoyed it, but it’s difficult to sustain it. We’re just staying home but we still like playing music. Most days of the week we play music together. We throw away a lot of stuff you know.

The three records are very different: the soundtrack is a very specific thing, Pinecone is a very specific thing and this acoustic record. There’s three records for next year too. We aren’t trying to, it’s just how it kind of naturally occurs. I mean there’s the Owls record and our main focus has been our soundtrack to this performance art piece. We did it in London in April I guess and that’s a very specific thing. We’ve been doing this funny greatest hits record of rearranged old songs. The label’s saying you sound better live than you ever have, you should make a record as a live band.

They’re very distinct. And that’s a music industry thing really, I mean if you love what you do you’ll want to do it every day. It doesn’t seem weird to me. I understand the labels hate it because the records come out in very small pressings now.

Do you still bartend at all?

You know, I just started again and it’s fine. I was miserable the first couple shifts, but I’m just doing it until I can start teaching again. I’m just not used to being up that late.

Did that inspire the book at all?

I’ve lived above the bar I worked at. I’m not in there very often when it’s open and crowded unless I’m working. But the owners and managers there are my best friends. So I guess I’ve just been around the bar. And my Dad was a governor of a Moose Lodge, so he was like a bar manager too. So I’ve always been around bars I guess.

1 note

·

View note

Link

How Susan Sontag Taught Me to Think

The critic A.O. Scott reflects on the outsize

influence Sontag has had on his life as a critic.

By A.O. SCOTT OCT. 8, 2019

“I spent my adolescence in a terrible hurry to read all the books, see all the movies, listen to all the music, look at everything in all the museums. That pursuit required more effort back then, when nothing was streaming and everything had to be hunted down, bought or borrowed. But those changes aren’t what this essay is about. Culturally ravenous young people have always been insufferable and never unusual, even though they tend to invest a lot in being different — in aspiring (or pretending) to something deeper, higher than the common run. Viewed with the chastened hindsight of adulthood, their seriousness shows its ridiculous side, but the longing that drives it is no joke. It’s a hunger not so much for knowledge as for experience of a particular kind. Two kinds, really: the specific experience of encountering a book or work of art and also the future experience, the state of perfectly cultivated being, that awaits you at the end of the search. Once you’ve read everything, then at last you can begin.

2 Furious consumption is often described as indiscriminate, but the point of it is always discrimination. It was on my parents’ bookshelves, amid other emblems of midcentury, middle-class American literary taste and intellectual curiosity, that I found a book with a title that seemed to offer something I desperately needed, even if (or precisely because) it went completely over my head. “Against Interpretation.” No subtitle, no how-to promise or self-help come-on. A 95-cent Dell paperback with a front-cover photograph of the author, Susan Sontag.

There is no doubt that the picture was part of the book’s allure — the angled, dark-eyed gaze, the knowing smile, the bobbed hair and buttoned-up coat — but the charisma of the title shouldn’t be underestimated. It was a statement of opposition, though I couldn’t say what exactly was being opposed. Whatever “interpretation” turned out to be, I was ready to enlist in the fight against it. I still am, even if interpretation, in one form or another, has been the main way I’ve made my living as an adult. It’s not fair to blame Susan Sontag for that, though I do.

3 “Against Interpretation,” a collection of articles from the 1960s reprinted from various journals and magazines, mainly devoted to of-the-moment texts and artifacts (Jean-Paul Sartre’s “Saint Genet,” Jean-Luc Godard’s “Vivre Sa Vie,’’ Jack Smith’s “Flaming Creatures”), modestly presents itself as “case studies for an aesthetic,” a theory of Sontag’s “own sensibility.” Really, though, it is the episodic chronicle of a mind in passionate struggle with the world and itself.

Sontag’s signature is ambivalence. “Against Interpretation” (the essay), which declares that “to interpret is to impoverish, to deplete the world — in order to set up a shadow world of ‘meanings,’ ” is clearly the work of a relentlessly analytical, meaning-driven intelligence. In a little more than 10 pages, she advances an appeal to the ecstasy of surrender rather than the protocols of exegesis, made in unstintingly cerebral terms. Her final, mic-drop declaration — “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art” — deploys abstraction in the service of carnality.

4 It’s hard for me, after so many years, to account for the impact “Against Interpretation” had on me. It was first published in 1966, the year of my birth, which struck me as terribly portentous. It brought news about books I hadn’t — hadn’t yet! — read and movies I hadn’t heard about and challenged pieties I had only begun to comprehend. It breathed the air of the ’60s, a momentous time I had unforgivably missed.

But I kept reading “Against Interpretation” — following it with “Styles of Radical Will,” “On Photography” and “Under the Sign of Saturn,” books Sontag would later deprecate as “juvenilia” — for something else. For the style, you could say (she wrote an essay called “On Style”). For the voice, I guess, but that’s a tame, trite word. It was because I craved the drama of her ambivalence, the tenacity of her enthusiasm, the sting of her doubt. I read those books because I needed to be with her. Is it too much to say that I was in love with her? Who was she, anyway?

5 Years after I plucked “Against Interpretation” from the living-room shelf, I came across a short story of Sontag’s called “Pilgrimage.” One of the very few overtly autobiographical pieces Sontag ever wrote, this lightly fictionalized memoir, set in Southern California in 1947, recalls an adolescence that I somehow suspect myself of having plagiarized a third of a century later. “I felt I was slumming in my own life,” Sontag writes, gently mocking and also proudly affirming the serious, voracious girl she used to be. The “pilgrimage” in question, undertaken with a friend named Merrill, was to Thomas Mann’s house in Pacific Palisades, where that venerable giant of German Kultur had been incongruously living while in exile from Nazi Germany.

The funniest and truest part of the story is young Susan’s “shame and dread” at the prospect of paying the call. “Oh, Merrill, how could you?” she melodramatically exclaims when she learns he has arranged for a teatime visit to the Mann residence. The second-funniest and truest part of the story is the disappointment Susan tries to fight off in the presence of a literary idol who talks “like a book review.” The encounter makes a charming anecdote with 40 years of hindsight, but it also proves that the youthful instincts were correct. “Why would I want to meet him?” she wondered. “I had his books.”

6 I never met Susan Sontag. Once when I was working late answering phones and manning the fax machine in the offices of The New York Review of Books, I took a message for Robert Silvers, one of the magazine’s editors. “Tell him Susan Sontag called. He’ll know why.” (Because it was his birthday.) Another time I caught a glimpse of her sweeping, swanning, promenading — or maybe just walking — through the galleries of the Frick.

Much later, I was commissioned by this magazine to write a profile of her. She was about to publish “Regarding the Pain of Others,” a sequel and corrective to her 1977 book “On Photography.” The furor she sparked with a few paragraphs written for The New Yorker after the Sept. 11 attacks — words that seemed obnoxiously rational at a time of horror and grief — had not yet died down. I felt I had a lot to say to her, but the one thing I could not bring myself to do was pick up the phone. Mostly I was terrified of disappointment, mine and hers. I didn’t want to fail to impress her; I didn’t want to have to try. The terror of seeking her approval, and the certainty that in spite of my journalistic pose I would be doing just that, were paralyzing. Instead of a profile, I wrote a short text that accompanied a portrait by Chuck Close. I didn’t want to risk knowing her in any way that might undermine or complicate the relationship we already had, which was plenty fraught. I had her books.

7 After Sontag died in 2004, the focus of attention began to drift away from her work and toward her person. Not her life so much as her self, her photographic image, her way of being at home and at parties — anywhere but on the page. Her son, David Rieff, wrote a piercing memoir about his mother’s illness and death. Annie Leibovitz, Sontag’s partner, off and on, from 1989 until her death, released a portfolio of photographs unsparing in their depiction of her cancer-ravaged, 70-year-old body. There were ruminations by Wayne Koestenbaum, Phillip Lopate and Terry Castle about her daunting reputation and the awe, envy and inadequacy she inspired in them. “Sempre Susan,” a short memoir by Sigrid Nunez, who lived with Sontag and Rieff for a while in the 1970s, is the masterpiece of the “I knew Susan” minigenre and a funhouse-mirror companion to Sontag’s own “Pilgrimage.” It’s about what can happen when you really get to know a writer, which is that you lose all sense of what or who it is you really know, including yourself.

8 In 2008, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Sontag’s longtime publisher, issued “Reborn,” the first of two volumes so far culled from nearly 100 notebooks Sontag filled from early adolescence into late middle age. Because of their fragmentary nature, these journal entries aren’t intimidating in the way her more formal nonfiction prose could be, or abstruse in the manner of most of her pre-1990s fiction. They seem to offer an unobstructed window into her mind, documenting her intellectual anxieties, existential worries and emotional upheavals, along with everyday ephemera that proves to be almost as captivating. Lists of books to be read and films to be seen sit alongside quotations, aphorisms, observations and story ideas. Lovers are tantalizingly represented by a single letter (“I.”; “H”; “C.”). You wonder if Sontag hoped, if she knew, that you would be reading this someday — the intimate journal as a literary form is a recurring theme in her essays — and you wonder whether that possibility undermines the guilty intimacy of reading these pages or, on the contrary, accounts for it.

9 A new biography by Benjamin Moser — “Sontag: Her Life and Work,” published last month — shrinks Sontag down to life size, even as it also insists on her significance. “What mattered about Susan Sontag was what she symbolized,” he concludes, having studiously documented her love affairs, her petty cruelties and her lapses in personal hygiene.

I must say I find the notion horrifying. A woman whose great accomplishments were writing millions of words and reading who knows how many millions more — no exercise in Sontagiana can fail to mention the 15,000-book library in her Chelsea apartment — has at last been decisively captured by what she called “the image-world,” the counterfeit reality that threatens to destroy our apprehension of the actual world.

You can argue about the philosophical coherence, the political implications or the present-day relevance of this idea (one of the central claims of “On Photography”), but it’s hard to deny that Sontag currently belongs more to images than to words. Maybe it’s inevitable that after Sontag’s death, the literary persona she spent a lifetime constructing — that rigorous, serious, impersonal self — has been peeled away, revealing the person hiding behind the words. The unhappy daughter. The mercurial mother. The variously needy and domineering lover. The loyal, sometimes impossible friend. In the era of prestige TV, we may have lost our appetite for difficult books, but we relish difficult characters, and the biographical Sontag — brave and imperious, insecure and unpredictable — surely fits the bill.

10 “Interpretation,” according to Sontag, “is the revenge of the intellect upon art. Even more. It is the revenge of the intellect upon the world.” And biography, by the same measure, is the revenge of research upon the intellect. The life of the mind is turned into “the life,” a coffin full of rattling facts and spectral suppositions, less an invitation to read or reread than a handy, bulky excuse not to.

The point of this essay, which turns out not to be as simple as I thought it would be, is to resist that tendency. I can’t deny the reality of the image or the symbolic cachet of the name. I don’t want to devalue the ways Sontag serves as a talisman and a culture hero. All I really want to say is that Susan Sontag mattered because of what she wrote.

11 Or maybe I should just say that’s why she matters to me. In “Sempre Susan,” Sigrid Nunez describes Sontag as:

... the opposite of Thomas Bernhard’s comic “possessive thinker,” who feeds on the fantasy that every book or painting or piece of music he loves has been created solely for and belongs solely to him, and whose “art selfishness” makes the thought of anyone else enjoying or appreciating the works of genius he reveres intolerable. She wanted her passions to be shared by all, and to respond with equal intensity to any work she loved was to give her one of her biggest pleasures.

I’m the opposite of that. I don’t like to share my passions, even if the job of movie critic forces me to do it. I cling to an immature (and maybe also a typically male), proprietary investment in the work I care about most. My devotion to Sontag has often felt like a secret. She was never assigned in any course I took in college, and if her name ever came up while I was in graduate school, it was with a certain condescension. She wasn’t a theorist or a scholar but an essayist and a popularizer, and as such a bad fit with the desperate careerism that dominated the academy at the time. In the world of cultural journalism, she’s often dismissed as an egghead and a snob. Not really worth talking about, and so I mostly didn’t talk about her.

12 Nonetheless, I kept reading, with an ambivalence that mirrored hers. Perhaps her most famous essay — certainly among the most controversial — is “Notes on ‘Camp,’ ” which scrutinizes a phenomenon defined by “the spirit of extravagance” with scrupulous sobriety. The inquiry proceeds from mixed feelings — “I am strongly drawn to Camp, and almost as strongly offended by it” — that are heightened rather than resolved, and that curl through the 58 numbered sections of the “Notes” like tendrils in an Art Nouveau print. In writing about a mode of expression that is overwrought, artificial, frivolous and theatrical, Sontag adopts a style that is the antithesis of all those things.

If some kinds of camp represent “a seriousness that fails,” then “Notes on ‘Camp’ ” enacts a seriousness that succeeds. The essay is dedicated to Oscar Wilde, whose most tongue-in-cheek utterances gave voice to his deepest thoughts. Sontag reverses that Wildean current, so that her grave pronouncements sparkle with an almost invisible mischief. The essay is delightful because it seems to betray no sense of fun at all, because its jokes are buried so deep that they are, in effect, secrets.

13 In the chapter of “Against Interpretation” called “Camus’ Notebooks” — originally published in The New York Review of Books — Sontag divides great writers into “husbands” and “lovers,” a sly, sexy updating of older dichotomies (e.g., between Apollonian and Dionysian, Classical and Romantic, paleface and redskin). Albert Camus, at the time beginning his posthumous descent from Nobel laureate and existentialist martyr into the high school curriculum (which is where I found him), is named the “ideal husband of contemporary letters.” It isn’t really a compliment:

Some writers supply the solid virtues of a husband: reliability, intelligibility, generosity, decency. There are other writers in whom one prizes the gifts of a lover, gifts of temperament rather than of moral goodness. Notoriously, women tolerate qualities in a lover — moodiness, selfishness, unreliability, brutality — that they would never countenance in a husband, in return for excitement, an infusion of intense feeling. In the same way, readers put up with unintelligibility, obsessiveness, painful truths, lies, bad grammar — if, in compensation, the writer allows them to savor rare emotions and dangerous sensations.

The sexual politics of this formulation are quite something. Reading is female, writing male. The lady reader exists to be seduced or provided for, ravished or served, by a man who is either a scamp or a solid citizen. Camus, in spite of his movie-star good looks (like Sontag, he photographed well), is condemned to husband status. He’s the guy the reader will settle for, who won’t ask too many questions when she returns from her flings with Kafka, Céline or Gide. He’s also the one who, more than any of them, inspires love.

14 After her marriage to the sociologist Philip Rieff ended in 1959, most of Sontag’s serious romantic relationships were with women. The writers whose company she kept on the page were overwhelmingly male (and almost exclusively European). Except for a short piece about Simone Weil and another about Nathalie Sarraute in “Against Interpretation” and an extensive takedown of Leni Riefenstahl in “Under the Sign of Saturn,” Sontag’s major criticism is all about men.

She herself was kind of a husband. Her writing is conscientious, thorough, patient and useful. Authoritative but not scolding. Rigorous, orderly and lucid even when venturing into landscapes of wildness, disruption and revolt. She begins her inquiry into “The Pornographic Imagination” with the warning that “No one should undertake a discussion of pornography before acknowledging the pornographies — there are at least three — and before pledging to take them on one at a time.”

The extravagant, self-subverting seriousness of this sentence makes it a perfect camp gesture. There is also something kinky about the setting of rules and procedures, an implied scenario of transgression and punishment that is unmistakably erotic. Should I be ashamed of myself for thinking that? Of course! Humiliation is one of the most intense and pleasurable effects of Sontag’s masterful prose. She’s the one in charge.

15 But the rules of the game don’t simply dictate silence or obedience on the reader’s part. What sustains the bond — the bondage, if you’ll allow it — is its volatility. The dominant party is always vulnerable, the submissive party always capable of rebellion, resistance or outright refusal.

I often read her work in a spirit of defiance, of disobedience, as if hoping to provoke a reaction. For a while, I thought she was wrong about everything. “Against Interpretation” was a sentimental and self-defeating polemic against criticism, the very thing she had taught me to believe in. “On Photography” was a sentimental defense of a shopworn aesthetic ideology wrapped around a superstitious horror at technology. And who cared about Elias Canetti and Walter Benjamin anyway? Or about E.M. Cioran or Antonin Artaud or any of the other Euro-weirdos in her pantheon?

Not me! And yet. ... Over the years I’ve purchased at least three copies of “Under the Sign of Saturn” — if pressed to choose a favorite Sontag volume, I’d pick that one — and in each the essay on Canetti, “Mind as Passion,” is the most dog-eared. Why? Not so I could recommend it to someone eager to learn about the first native Bulgarian to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, because I’ve never met such a person. “Mind as Passion” is the best thing I’ve ever read about the emotional dynamics of literary admiration, about the way a great writer “teaches us how to breathe,” about how readerly surrender is a form of self-creation.

16 In a very few cases, the people Sontag wrote about were people she knew: Roland Barthes and Paul Goodman, for example, whose deaths inspired brief appreciations reprinted in “Under the Sign of Saturn.” Even in those elegies, the primary intimacy recorded is the one between writer and reader, and the reader — who is also, of course, a writer — is commemorating and pursuing a form of knowledge that lies somewhere between the cerebral and the biblical.

Because the intimacy is extended to Sontag’s reader, the love story becomes an implicit ménage à trois. Each essay enacts the effort — the dialectic of struggle, doubt, ecstasy and letdown — to know another writer, and to make you know him, too. And, more deeply though also more discreetly, to know her.

17 The version of this essay that I least want to write — the one that keeps pushing against my resistance to it — is the one that uses Sontag as a cudgel against the intellectual deficiencies and the deficient intellectuals of the present. It’s almost comically easy to plot a vector of decline from then to now. Why aren’t the kids reading Canetti? Why don’t trade publishers print collections of essays about European writers and avant-garde filmmakers? Sontag herself was not immune to such laments. In 1995, she mourned the death of cinema. In 1996, she worried that “the very idea of the serious (and the honorable) seems quaint, ‘unrealistic’ to most people.”

Worse, there are ideas and assumptions abroad in the digital land that look like debased, parodic versions of positions she staked out half a century ago. The “new sensibility” she heralded in the ’60s, “dedicated both to an excruciating seriousness and to fun and wit and nostalgia,” survives in the form of a frantic, algorithm-fueled eclecticism. The popular meme admonishing critics and other designated haters to shut up and “let people enjoy things” looks like an emoji-friendly update of “Against Interpretation,” with “enjoy things” a safer formulation than Sontag’s “erotics of art.”

That isn’t what she meant, any more than her prickly, nuanced “Notes on ‘Camp’ ” had much to do with the Instagram-ready insouciance of this year’s Met Gala, which borrowed the title for its theme. And speaking of the ’Gram, its ascendance seems to confirm the direst prophecies of “On Photography,” which saw the unchecked spread of visual media as a kind of ecological catastrophe for human consciousness.

18 In other ways, the Sontag of the ’60s and ’70s can strike current sensibilities as problematic or outlandish. She wrote almost exclusively about white men. She believed in fixed hierarchies and absolute standards. She wrote at daunting length with the kind of unapologetic erudition that makes people feel bad. Even at her most polemical, she never trafficked in contrarian hot takes. Her name will never be the answer to the standard, time-killing social-media query “What classic writer would be awesome on Twitter?” The tl;dr of any Sontag essay could only be every word of it.

Sontag was a queer, Jewish woman writer who disdained the rhetoric of identity. She was diffident about disclosing her sexuality. Moser criticizes her for not coming out in the worst years of the AIDS epidemic, when doing so might have been a powerful political statement. The political statements that she did make tended to get her into trouble. In 1966, she wrote that “the white race is the cancer of human history.” In 1982, in a speech at Town Hall in Manhattan, she called communism “fascism with a human face.” After Sept. 11, she cautioned against letting emotion cloud political judgment. “Let’s by all means grieve together, but let’s not be stupid together.”

That doesn’t sound so unreasonable now, but the bulk of Sontag’s writing served no overt or implicit ideological agenda. Her agenda — a list of problems to be tackled rather than a roster of positions to be taken — was stubbornly aesthetic. And that may be the most unfashionable, the most shocking, the most infuriating thing about her.

19 Right now, at what can feel like a time of moral and political emergency, we cling to sentimental bromides about the importance of art. We treat it as an escape, a balm, a vague set of values that exist beyond the ugliness and venality of the market and the state. Or we look to art for affirmation of our pieties and prejudices. It splits the difference between resistance and complicity.

Sontag was also aware of living in emergency conditions, in a world menaced by violence, environmental disaster, political polarization and corruption. But the art she valued most didn’t soothe the anguish of modern life so much as refract and magnify its agonies. She didn’t read — or go to movies, plays, museums or dance performances — to retreat from that world but to bring herself closer to it. What art does, she says again and again, is confront the nature of human consciousness at a time of historical crisis, to unmake and redefine its own terms and procedures. It confers a solemn obligation: “From now to the end of consciousness, we are stuck with the task of defending art.”

20 “Consciousness” is one of her keywords, and she uses it in a way that may have an odd ring to 21st-century ears. It’s sometimes invoked now, in a weak sense, as a synonym for the moral awareness of injustice. Its status as a philosophical problem, meanwhile, has been diminished by the rise of cognitive science, which subordinates the mysteries of the human mind to the chemical and physical operations of the brain.

But consciousness as Sontag understands it has hardly vanished, because it names a phenomenon that belongs — in ways that escape scientific analysis — to both the individual and the species. Consciousness inheres in a single person’s private, incommunicable experience, but it also lives in groups, in cultures and populations and historical epochs. Its closest synonym is thought, which similarly dwells both within the walls of a solitary skull and out in the collective sphere.

If Sontag’s great theme was consciousness, her great achievement was as a thinker. Usually that label is reserved for theorists and system-builders — Hannah Arendt, Jean-Paul Sartre, Sigmund Freud — but Sontag doesn’t quite belong in that company. Instead, she wrote in a way that dramatized how thinking happens. The essays are exciting not just because of the ideas they impart but because you feel within them the rhythms and pulsations of a living intelligence; they bring you as close to another person as it is possible to be.

21 “Under the Sign of Saturn” opens in a “tiny room in Paris” where she has been living for the previous year — “small bare quarters” that answer “some need to strip down, to close off for a while, to make a new start with as little as possible to fall back on.” Even though, according to Sigrid Nunez, Sontag preferred to have other people around her when she was working, I tend to picture her in the solitude of that Paris room, which I suppose is a kind of physical manifestation, a symbol, of her solitary consciousness. A consciousness that was animated by the products of other minds, just as mine is activated by hers. If she’s alone in there, I can claim the privilege of being her only company.

Which is a fantasy, of course. She has had better readers, and I have loved other writers. The metaphors of marriage and possession, of pleasure and power, can be carried only so far. There is no real harm in reading casually, promiscuously, abusively or selfishly. The page is a safe space; every word is a safe word. Your lover might be my husband.

It’s only reading. By which I mean: It’s everything.”

0 notes

Text

tagged by @chlance for this 10 + 1 facts about me thing. i’m not entirely sure i’ve seen that floating around before now. also, i’m incredibly boring.

click the read more at your own risk.

i’ve been writing for 11 years. it’s weird to think about it in terms of time now because i used to talk about it in high school, joking i’d have been writing for a whole decade soon. but nonetheless, it’s true. i started writing when i was very young because state standardized testing is terribly boring, takes too little time, and i needed to fill in the huge empty gaps of waiting with something. i’m still not entirely sure what drove me to write in the first place, but that’s what i did. and i’ve almost always been exclusively fascinated by stories about lgbt people and lgbt relationships even before i knew i was lgbt.

i like shitty movies and hate good movies. that’s only half a joke. there are plenty of movies that are considered “good” that i like, but when i actually tried watching a lot of classic movies that people have raved about, i ended up not liking a lot of them or just being terribly bored. it’s not even just a matter of not appreciating the themes present, but more that the films just don’t hold my interest for very long. in contrast, i can binge watch shitty horror films until i pass out in the middle of them. creature feature weekends on syfy used to be my favorite parts of the month for a reason.

i have a fear of ghosts and demons. i’m not entirely sure what caused it or why it’s become such a part of my life, maybe it’s just too many possession/demonic horror films at the wrong point in my life. maybe it’s just that i was raised religious and though i’m not religious anymore, i still can’t shake the fact that i believe these things do exist and can be malevolent. maybe it’s too much reading too late at night. i don’t really know why, to be honest. it’s ironic, because i’ll purposefully seek out movies and books that feature ghosts and demons. the grudge came out in 2004, and to this day i still have a paranoid and irrational fear of stairs late at night and can’t shake the creepy feeling that something is in the dark. might sound crazy, but it’s true.

i suffer from mental illness and personality disorders. and they all most likely result from the abuse i suffered at the hands of my mother for most of my life. i have very high key anxiety, which makes it difficult for me to initiate conversations with people and make decisions that are risky in nature. it also makes walking my dog at night very difficult. there is also depression mixed in there, which makes me very tired and decreases my motivation significantly. i have bpd and avpd, as well. bpd makes it very difficult for me to manage my emotions, as everything feels very intense or very numb, and contributes significantly to my self-loathing as there’s a constant stream of uncertainty in my head. avpd makes it very difficult to talk to outside sources about my issues, which makes therapy at the moment an absolute impossibility. i’m finding my own ways to cope as i can, and i think it’s starting to work.

tadanobu asano is my favorite actor. and he has been since i watched ichi the killer when i was in sixth grade. that was a very pivotal point in my life for several reasons, and he’s very important to me. believe me when i say that silence might have been a shitty movie, but i really enjoyed everything he did in it. i’ve been steadily tracking down and watching his films ever since. he’s the real reason that i started watching j-horror in the first place, which is pretty much what led me to the place i’m at right now and led me to the fandoms that would become the most important to me and the most important in my life. there’s a LOT i would like to thank him for, tbh. he means a lot to me.

i love animals, and they love me. and i’m not exaggerating when i say that. i’ve encountered animals and been told that they’re dangerous, but they liked me just fine. i’ve had stray animals grow warmer towards me and allow me to pick them up and hold them. my grandmother had kittens in the barn next to her house and i was the one who made it possible for my cousins to touch them since they trusted humans by trusting me first. i’ve had people’s dogs who usually bite approach me and let me pet them. and i really love animals. i don’t kill bugs if i don’t have to, i used to play with the daddy long leg spiders that showed up in my veterinary science room in high school, and i raised praying mantises as a kid and kept a pet frog for just over a year.

i have a natural talent for academic writing. when i was in my last two years of high school, my grades absolutely tanked and a large part of that had to do with returning to an abusive environment and being so isolated from everyone that i had no way to cope. my grades suffered heavily, except for my grades in english. my senior year, i was taking a college freshman level class through a university and i was able to get great grades in it even when i often scrambled to complete assignments or worried i didn’t understand the material. i had a teacher comment he never understood how much english meant to me until he saw a test score of mine that was incredibly high when most people hadn’t scored that high. had i kept my shit together and gone to college, i probably would have studied it. i might still some day if i ever get my shit together enough to consider attempting anything academic.

i have a sleep disorder. it’s largely caused by working the night shift and developed the longer i worked there. while left to my own devices, i usually develop a nocturnal sleep schedule and spent an entire summer sleeping during the day and staying up all night several times. that didn’t really translate well to working for some reason. as time passed, it became more and more difficult to sleep during the day to the point where i now have to take sleep medication to ensure i sleep for more than three to four hours before i go to work. during my days off, my sleep schedule almost always tries to revert to me staying up during the day and sleeping at night, and it’s an active issue trying to resolve it. i’m strongly considering changing what hours i work as a result.

i’m agnostic. i was raised in a nondenominational christian church and ended up not going back once i entered public school. when i lived with my grandmother, i encountered several denominations, which were apostolic, baptist, and pentecostal. needless to say, i’m very apathetic at best to religion. that doesn’t stop me from watching movies that include religion or make me automatically dislike media with religious themes. i’ve also retained a lot of information about christianity from my time in the church and my own studies which makes me very critical toward people misusing the faith. i don’t mind people who are religious! i just merely ask that you don’t approach me about the topic unless you’ve asked first.

i’m gay and trans. it’s in my about and my description and if you somehow missed both of those, i talk about it a fair lot. my identity is very important to me. i knew for the vast majority of my life that i was not straight or cis, but i didn’t have the terms i needed to really describe how i felt and wasn’t really able to admit it to myself until recently. however, that’s who i am. being lgbt is very important to me and is a very important part of my life.

i’m a restless perfectionist. it’s why you’ll see my theme change often (though this one is lasting well). it’s why my icon and mobile banner change. on my old tumblr account and on twitter, my @ changed very often, as did my entire layout + color scheme. i want things to be perfect, and that often means changing them. that also means i pretty much bust my own ass on my writing and my gifs and edits, and it also means i hate a whole hell of a lot of what i create because it’s never up to scratch and never what i envisioned it to be.

since i’m supposed to tag 11 followers, i’ll tag @halfpastmonsoon @yoshimiyahagi @hironoshimizu @sparktaekwoon @complicatedmerary @chatcsantana @underjacksumbrella

look that’s enough anyway if you actually read this... i’m so sorry

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Julian Robertson: A Tiger in the Land of Bulls & Bears (2004)

Main thing Julian was known for was massive competitive streak -- hated to lose at anything. There are a lot of similarities to the obsessive (and great) athletes like MJ, Tiger or Lance Armstrong. Comp is made to Vince Lombardi who treated athletes poorly but got the best out of them.

Very image-conscious (ie the obsession with being well dress and looking put together) and balanced a Southern genteel politeness with a temper and “deliberate coarseness”

Key to every investment was “story” -- a simple, sensible narrative. When that changed or a fact violated it, Roberton was ruthless about getting out. No room in portfolio for broken story.

Story is the empirical embodiment of the quality of the research. If story shows flaws, indicates research is flawed

When story was not broken, had ability to take major pain and stick with unpopular positions. Great at avoiding deluding himself or rationalizing a position

To commit capital, needed first-hand knowledge of an industry or company. Secondhand tips or analysis was never enough. In the 1990s, before internet, this meant lots of travel

Not a good student at UNC -- didn’t enjoy the rigor of studying for most courses

Robertson’s initial contact with HF world was because a partner of his at Kidder Peadbody married AW Jones’ daughter, so he got to know Jones and learned shorting from him. Thus Jones’ FO became Tiger’s first LP through his son-in-law.

Always maintained a huge network for information-gathering -- highly valued being able to pick up the phone and get first-hand knowledge quickly.

To make an educated decision, need to know every variable and understand how they interact.

Firm had strong macro views going back to at least 1985 when Robertson made bets on stocks due to his view on the impact of a too-strong USD. Also had the ability to allocate 25% of portfolio to commodities from early on

For much of the 1980s, Robertson was cautious on the US economy because dollar strength made imports too cheap -- he expected infatuation with imports to be a major LT problem for US economy

Looked at margin buying trends, put-call ratio and pension/IRA flows to determine market-level sentiment and positioning

Outperforming Soros and Steinhardt in the 1987 crash (finished year flat) was crucial because there were seen as his main competition

He was bullish post-1987 because 80%+ of Americans weren’t hurt more as their home value went up, credit loosened and dollar weakness helped competitiveness of factories. In 10 days after the crash, Ford sales were up 15% YY

In mid-late 80s, 30% of HBS grad were going to Wall Street -- sign of overheated industry

Even during late 80s, Japanese company ROEs / ROAs were below global averages

There was lots of fear USTs would be sold aggressively in any Japanese market crash

Tiger owned Ford and actually wrote a letter to BOD in mid-1988 objecting to low-return M&A (including Hertz) and asking mgmt to allocate capital more like Henry Singleton by repurchasing stock

Very focused on idea velocity and maintaining steady flow of new ideas to compete for capital with existing positions. Actively reached out to Tiger investors requesting tips and ideas from industries they knew well for the team to analyze. Good names always had to be replaced by better names, never-ending process.

Brought on a psychologist, Dr. Aaron Stern, in 1993 who developed the “Tiger test” for applicants -- looking for smart/quick, ethical, background in sports, interest in charity/public welfare, sense of humor/fun to be around, and good resume

At one point also installed member of his team on a company board during a turnaround, but no details given

Objective of the investment process was “is this a risk worth taking” -- seeking phenomenal r/r

“You never make a mistake by seeing people with brains” -- Always be willing to take a meeting with someone smart

Robertson apparently admitted firm’s downfall was due to over-expansion of assets / growing too fast.

Tiger analysts believe something was lost when firm starting hiring bigger names and people later in Wall Street careers as opposed to young guns who were hungry and willing to take risk because they “didn’t know any better”. Later on, firm was said to be filled with “lifers” who viewed Tiger as a place to go cash out.

As org grew in complexity and size, analysts lost their easy access to Robertson and free flow of ideas ceased.

Friday idea lunch meetings were famously competitive and intense but got less so as the org became less tight knit / more siloed. Pitches had to be short and to the point -- allocated 5 mins, must be summarized in 4 sentences, even if that reflected 6 months of work. Story had to come across in a salient way. Analysts would then stress-test it, idea was if you weren’t prepared you’d definitely be caught out.

Not unusual for Robertson to 2-3x a position vs. recommended size without telling the analyst

At one point, Tiger had engaged Margarat Thatcher and Bob Dole, both of whom assured Robertson a Russian default was impossible in 1997.

Leaving the firm was very personal, Robertson usually wouldn’t speak to someone who’d left for 6 months or more.

As Robertson aged, became more set in his ways and harder to question, also started fighting positions more rather than getting out quickly when they went against him.

After Tiger shut down, sub-letting his office space to new managers was a rational step that led to a virtuous cycle -- he got idea generation, seeded and invested in funds and referred investors.

In 2003, was estimated former Tigers managed 10% of HF assets and 20% of assets devoted to L/S equity strategies.

Robertston was said to be making 20%/year on his own money after closing.

Huge focus on philanthropy and giving back -- specifically to his hometown in NC as well as to NYC, where his profits were generated. Often around breaking the cycle of poverty and homelessness. Encouraged highly analytical approach to where his dollars could be most impactful.

Takeaways

It’s hard to stress how poorly written and repetitive this book is. It’s actually painful to read. While this is apparent from the start, I soldiered on in hopes of picking up some interesting anecdotes — I have some personal familiarity with 101 Park and Julian, so I was interested in learning more about his history. As such, I’m reluctant to blindly reprint some of the lessons from it, so there’s a lot I’ve left out. Much of the writing was contradictory, so it was often hard to tease out how Robertson was positioned at certain key moments, etc. In my view,what the book accomplishes is to tell the story of the firm (performance year by year, major/notable trades, AUM growth, significant anecdotes, some name-dropping) without really getting into the interesting details of how research was done and what their contribution to the HF canon really was.

Confirms a lot of what’s know at a high level about the Tiger model -- focus on story, big high-conviction bets, best-in-class management backed up by deep first-hand diligence and stress-tested in internal meetings.

In Strachman’s view, Tiger’s main success was due to Robertson’s unrelenting competitive nature, ability to attract and retain top talent (via huge pay, despite a brutal work environment) and its fall was due to their over-aggressive asset gathering and inability to put $20B+ of equity (levered 3-4x) to work in equities leading them further into macro trading.

If you’re looking for more insightful perspective on Robertson, this portion of a recent interview with Mark Yusko is worth a read or watch: https://acquirersmultiple.com/2019/12/julian-robertson-one-of-the-most-important-lessons-double-up-not-down/

0 notes

Link

(Via: Lobsters)

Transcript

(Editor's note: transcripts don't do talks justice. This transcript is useful for searching and reference, but we recommend watching the video rather than reading the transcript alone! For a reader of typical speed, reading this will take 15% less time than watching the video, but you'll miss out on body language and the speaker's slides!)

[APPLAUSE] Can everybody hear me?

Yes.

Great. OK. So first of all, thank you all for coming to my talk, SOLID is Solid, enterprise pencils in OOP architecture. We're going to be talking about why SOLID is super important for OOP because it's very important. So there's basically five principles of SOLID. There's a single responsibility-- all classes should have one responsibility; open-closed, saying that all classes should be open and/or closed; we have this Liskov substitution principle, which I don't know what that even means; interface segregation principle, all individually segregated; and dependency inversion, you have to flip your dependencies upside-down.

I want to go into detail about all of this, but first, quick show of hands. Who here knows what SOLID is? Oh, that's most of you. Don't need to do that one anymore. It's OK, it's OK, it's OK, I've got a backup in here. I just need to find it real quick. Not that.

[LAUGHTER]

Yeah, I think it'll still work. OK. So who knows why SOLID is so important? Or more specifically, why SOLID and not something else? Sure, there's good ideas there, but there's good ideas everywhere, right? Why did SOLID win out and not, say, OMT or Booch Method or Design by Contract? Why SOLID?

It turns out there is a very, very, very specific reason-- this guy. Robert C Martin is one of the biggest modern influencers in tech. If you've heard of things like Agile or TDD or clean Code or software craftsmanship, these are all ideas he either pioneered or invented. He is very controversial, I will admit that, but you cannot deny his influence.

In 1995, he read a post on a forum, newsgroup, whatever called, "What are the 10 commandments of OOP?" People were giving very different, often contradictory answers to this. He listed his 11. He went-- off by one error. And then divided them into three groups. Five on design, three on packaging, three on systems.

Later, Michael Feathers realized that the first five can be called SOLID based on the initial first letters. And this he pushed-- sorry, Robert Martin pushed in his many, many, many popular bestsellers. And that's it. That's the reason SOLID is everywhere. One person in the right place at the right time with the right audience. And so the industry zigs instead of zags, and what one person believes becomes common wisdom.

We tend to think of history as something in the past, something that ended, a story that's over. A thing we can pick up and examine like an insect trapped in amber. But that's not how the world works. The past flows eternally into the present. History happens and keeps happening. And only by understanding how the world was can we understand where we are now.

My name is Hillel Wayne, and this is a talk on software history. What makes it so valuable and how we can use it to better ourselves as engineers. One thing before I start. I have a lot of sources in this talk. I don't want you to blindly believe what I say. I want you to be able to do the same research yourself. You can go here to see all of the resources on this talk as well as the slides, and if anybody asks me questions after, I'm going to write them down and put them up there, too.

So the past becomes the present infinitely. Everything we do is built upon layer upon layer of abstractions. Some of these abstractions, some of these decisions are years, decades, even centuries old. And they were often decided by people with given constraints and given problems. They did the best solution they could think of at the time. This is normal. We do the same. This is how engineering works.

But their choices, their decisions live with us. But most often, their reasons do not. We do not have the same context that they do that the world has changed. Our companies change, everything changes. We are now faced with what is without knowing why is. So what do we do? We make things up.

This happens all the time. We have something that we'd want to understand about our current world, and we come up with some sort of post hoc justification to explain why it's the way it is. A justification that's quite often wrong, and wrong in ways that make us worse off that are the opposite of the original reasons that make our products worse, our paradigms worse, our process worse.

To give even one small example, I mean, look at SOLID. There are great ideas there, I'm going to say that, but if you basically look online, people essentially treat as a stark division. OOP and SOLID are the same thing. If you do OOP, you must do SOLID. If you hate SOLID, you must also hate OOP. But they're not the same thing. They only seem like the same thing because historically, there was one very charismatic, very influential individual who supported that. Without that understanding of the context of the history, we miss that out. We miss out that it's just a decision.

There's a lot of power in history, but that's not what I want to convince you of. What I want to do today is show you how it can benefit you. How you can study history to learn more about the work you do, to learn more about the decisions made, to learn more about why you do things. And I honestly think the best way to do that is to show you what it's like to take a question and walk you through the process of researching it. To show you how even the smallest things have a rich history behind them that shapes our world today.

So show of hands, who here has done a linked list question on an interview, like reverse a linked list? Yeah. I see that's a lot of you. Now lower your hand-- keep your hands raised-- lower your hand if you have actually used a linked list on your job. Now-- OK, still see a few hands. Now keep that-- now lower your hand if you have used that linked list on a job and you are not a low level systems programmer. Well, a couple of people. That's kind of cool.

Right. So there's actually some like-- so somebody just in the audience said that there's-- some of us are functional programmers. There's actually some really subtle nuances that I'll get into later. But I was simply asked, when I was first interviewing in 2013, to do linked list questions, to reverse linked lists, to do algorithms in Python. It doesn't even make sense in Python.

And I remember asking the first company why I was supposed to do this? What was the value in it? And they said, oh, we want to see if fundamental CS knowledge. Do you know your algorithms, do you know your data structures, et cetera? Then on a different interview for a different company, I got the same question, and I asked the same question. Their reason was completely different. It's, can you take a problem you've never seen before and reason through it and think on your feet?

And this got me suspicious.

[LAUGHTER]

These reasons are actually kind of contradictory. Either it's whether you have the wrong knowledge or whether you don't have the knowledge but can reason quickly. So which is it? What does it actually test? Or does it test neither of them? So here's the process I did to sort of look through the history to figure out the origins of this question and decide why it was actually being asked.

Now one important caveat here. History is big and complicated. This is the process I took. You may disagree with my results and you may disagree with my methods. That's fine. I'm showing you how this works so that you can do it, too. What's important is that we search and we keep searching.

So the first step is to actually pin down the origins. When did it happen? And this is important because we want to find the source, not the post hoc. I can easily find things from 2004 that say, oh, ask these questions about your reasoning ability. And if it comes from 2004, then we're done, we know the reason. But if it comes from earlier, then they were also post hoc justifying it.

So when does it come from? My first guess was it was the 1990s, roughly when like the dot-com era was booming. So I want to find out if this was actually true. How do I know what questions people were asking at that time for job applications? I ask other people. Turns out that just going up to people who remember stuff and asking them is a pretty great way to learn stuff.

[LAUGHTER]