#also the only thing you can really put in a query is plot/premise

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

writing a query letter and i THINK it's in good shape but it's making me want to throw up because the point of a query letter is telling potential literary agents "here's why my book is good!!" and idk man!! is it!!

#like probably it is at least a little good#but!! evaluating your own work is hard!!#also the only thing you can really put in a query is plot/premise#but i feel like a lot of the appeal of my manuscript is execution/tone/ideas#which is a hard thing to talk about in a summary#because I feel like it breaks the whole point of show-don't tell#writing#hehe ~putting yourself out there~ scarey :( wanna hide in my hole

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reverse-Outlining Revision Method with Plottr

So in my editing guide, I give a step-by-step method for structural editing that I find really useful, and I wanted to do a visual follow-up to kind of show what that process looks like. I’m using Plottr for this, because I was gifted a copy of the software in exchange for them using my horror-writing beat-sheet as one of the templates, but you could just as easily do this with Scrivener, scrap paper, or any other organizational system you like.

Whether you’re a fellow pantser who struggles with story structure (hi!) or you’re an outliner who needs to make sure your draft matches up to your vision (or the second draft has a good structure), this will work for you!

Step One: Write a one-sentence log-line of the story + jot down the major themes

There’s space for this in Plottr. I’m doing Neverest.

Premise: A woman’s search for her missing husband’s body on Mount Everest sends her into the grip of ancient forces that don’t want her to leave.

Themes: Putting your name on something doesn't make it yours; colonialism and the urge to conquer and codify; relationships as a form of control and change vs understanding

You’ll also want to write a one-page overview summary of the story, similar to what you’d put in a query letter. Here’s mine:

One year ago, Sean Miller -- journalist and mountain climbing enthusiast -- reached the summit of Mt. Everest, and was never seen again. Unable to move on without knowing the truth of what happened, his wife Carrie flies to Nepal to meet with Sean’s best friend and former climbing partner, Tom. They assemble a small crew and begin an expedition up the peak in search of Sean’s body and a better understanding of what might have happened in his final days.

Guided by a travel journal left behind from her husband's expedition, Carrie ventures into the frozen, open-air graveyard of the world's tallest peak. But as Sean’s diary and Carrie’s experiences reveal, climbing the mountain is more than a test of endurance; it’s a battle of wills with an ancient and hostile force protecting the mountain — and the dead do not rest easy at the summit.

Doing this helps you to identify the core elements of your story -- the characters, the conflict, and the stakes. You should be able to answer the questions: who is the main character, what do they want, what’s stopping them, what happens if they succeed/fail.

In this case:

The main character is Carrie, the wife of a journalist who disappeared while summiting Mt. Everest (character)

She wants to find his body and get closure about his death/understand how and why he died (what does she want)

But there are supernatural forces at work that led to his death and now have the same in store for her (conflict/stakes)

Step Two: List out every scene in the book

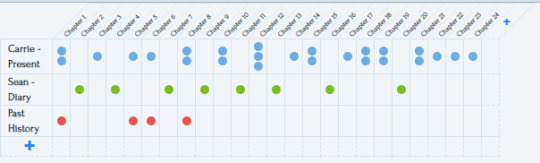

Plottr is an outlining software, so it makes this step really easy (and conveniently color-codes things for me at the same time!). There are multiple views this can take, but this one screenshots well so I used this one for the example.

Basically what you want to do is write down everything that happens, scene by scene. You can color-code them however you want -- in my case, I have three narrative threads, so I made a timeline for each one. Then I just mapped out all the scenes -- across 24 chapters, each dot is a scene, and you can see that some chapters have multiple scenes and also that the primary and secondary plot alternate chapters.

When you look at it this way, you can tell really clearly that the tertiary plot needs some work -- it’s only there for four scenes in the first third of the story. I either need to cut it completely and incorporate any essential information into the other plots, or I need to expand it.

In this particular case, I decided to expand because 1.) my word count is low, and I’d like to fill in more story and 2.) a big theme I want to explore in the story is what it’s like to love someone who’s deeply passionate about something you don’t understand -- so this tertiary plot is a great place to explore that and fill in more characterization that should add some depth to the primary and secondary stories.

I can also see at a glance that I have a variable number of scenes in each chapter. Sometimes that makes sense (the green ones are diary entries, so it’s logical that one chapter = one entry) but sometimes it hints that those chapters could be a little thin and need more content. If I’m looking to add additional conflict, I should do it in those blue chapters that only have one dot as opposed to the ones with multiple dots!

Step Three: Look at the overall shape and adjust for pacing and genre

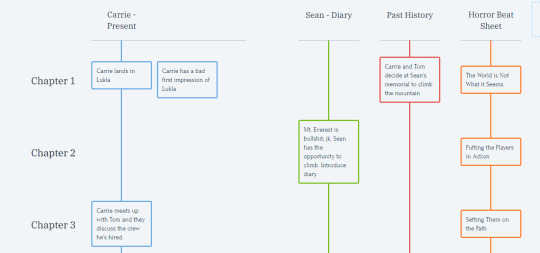

Plottr has a bunch of templates pre-loaded into it that make this easy, but you can also just google various different story structures and beat sheets such as Save the Cat or the 3 Act Structure etc. But just look at the overall map of story beats and see how they line up with the outline you’ve made:

This is just a small snapshot view, but you get the idea -- when you look at the scenes side-by-side with the beat sheet, you can see some things. For example, it sure would make more sense if the flashback scene where Carrie decides to embark on this journey got its own chapter and lined up better with the “putting the players in action” plot point rather than being smooshed into the first chapter with the introduction to the world! The fact that I’ve got it smashed into that first chapter is probably a sign that my opening scenes/chapter itself is a bit thin and needs to be fleshed out a little more.

Step Four: Figure out what you need to adjust and make the changes accordingly

So after looking at everything mapped out this way, I’ve got a little list of things I need to do:

Come up with more scenes for that red plotline

Rearrange some things a little bit to better fit the structure I want

Figure out some more blue scenes to fill in the gaps caused by rearranging things and smooth over the pacing/amp up the conflict/alleviate some areas where critique partners hae expressed confusion

I also moved around the categories in Plottr (you can drag-and-drop storylines and chapters) to make it a bit easier to see everything all at once. Basically you can edit the story’s outline first, to save you the confusion of manually moving around whole paragraphs/chapters in your actual story document.

Now, I haven’t finished that step yet for this particular project (there’s a lot of brainstorming to do re: filling in those gaps!) BUT I did want to skip ahead to show you the next step (let’s pretend this is a TV cooking show where the finished pie is pulled right out of the oven).

Step Five: Re-Type everything based on your new scene list

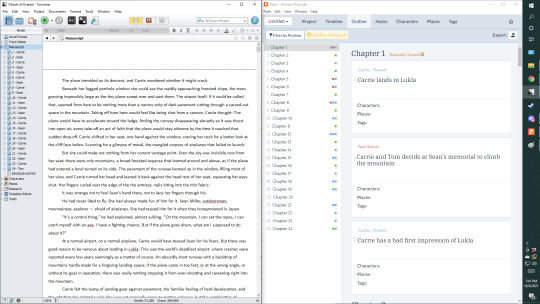

This is a really neat thing about Plottr. If you swap from the “Timeline” view to the “Outline” view, you get these editable text windows where you can type whatever you want, and it’ll keep it organized into chapters and scenes.

So, just pull up your original in one window, and the Plottr screen (or other outlining/drafting device) in another. Dual monitors are great for this but we make due. Now, retype the original document into the new document, making changes as you go to fit the new outline and also cleaning up language and so forth as you go. For example, this time around I’ll be changing Carrie’s blue timeline scenes to present-tense instead of past, so I’ll rewrite them in present tense in the new window.

Once all that is said and done, in Plottr you can export the file directly into Scrivener or Word. (If you’re not using Plottr, you’ll have to figure out for your own self how to transfer the final product into a final document -- I trust you can sort through that). From there you’ve got a fresh clean copy of a second draft all ready to go for the final copy-edit/proofread/polish/formatting and then you’re off to the races!

I hope this was helpful for you! I talk more about editing in my Gumroad guide here: https://tlbodine.gumroad.com/l/jkLpr

If you’d like to receive all of my existing + future guides and support me in making more content like this, consider subscribing to my Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/tlbodine

And you can pick up a copy of Plottr here: https://plottr.com/

This post isn’t sponsored or anything, but I did get a free copy of the software from the developer and I think it’s pretty neat. It’s still in beta so new features keep getting added, and the team that makes it are very nice and responsive to feedback.

#writing advice#writing tips#outlining#editing#how to edit#editing advice#writeblr#writing#share to save a writer

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rejection Woes

Anonymous said: Hi. I apologise for the missing part. I've been rejected by 250+ agents. Most said I have an intriguing and original premise with complex characters, but it's not right for their list right now. Some loved the concept and writing, asking for the full manuscript, and then rejected it for reasons like it had too hard issues, the violence made them uncomfortable, a character seemed underdeveloped, they didn't connect with the voice, or they simply don't feel passionate enough to represent it. I've had two professional editors and one literary agent look it over. They didn't mention any of the above issues, but felt immersed and connected, and they told me that my manuscript is different. The literary agent also told me to query the best agents out there because that's what my manuscript deserved. I sent it to an independent publishing house for yet another opinion (since I always doubt praise), and the director there compared my writing to Kahlil Gibran and wanted to publish it. However, I have to pay for the publication, and they'll distribute it to Amazon, Waterstones, and Barnes & Nobles, as they have some kind of deal with them. (I checked the publishing house and it's legit).

At this point, I'm so lost and I don't feel like a writer, or that my manuscript is worth being published. I can't figure out if something's wrong with my writing, or if it's just a matter of taste and whether my manuscript fits the format of a mainstream YA Fantasy for the agents. One of the professional editors was also a consultant at a well-known press and she was adamant about acquiring my manuscript from me (claiming that it was a powerful and different manuscript) once I'd cut the things that she wanted me to cut to follow the YA Fantasy formula, so I reworked most of it, but didn't feel comfortable compromising on the things that represented my culture and were essential to the plot. She seemed insulted and rejected me. This entire process of querying, receiving all this contradicting feedback, and being rejected over and over, has convinced me that I don't have what it takes to write a successful story, and my writing isn't good enough for the publishing world. All I wanted was to tell a story that mattered beyond just the entertainment value. To have my voice be heard. I'm sorry for dumping this on you. I don't even know what I'm trying to ask anymore.

First, more than anything else, I want to give you some virtual hugs and make sure you understand that rejection, and having a hard time finding a home for an unusual story, is not a reflection upon the quality of your story and your talent as a writer. It also doesn’t mean there’s not an audience for your book. There’s an audience for everything--it just takes a little longer to find that audience for books that stray from the “tried and true” formula, and neither agents or publishers are interested in putting in the time to search for an audience. (More on that in a bit...)

So, what’s the explanation for the conflict between the praise you’ve received and the inability to find an agent to represent you? The explanation is money. Plain and simple.

You see, the traditional publishing industry has one goal: to make money. Every decision they make is what’s best for the bottom line. And what people may not realize about the publishing industry is that every manuscript they take on presents a potential financial risk. Why? Because they’re going to pour a ton of money into that manuscript in order to turn it into a book that can sit on shelves. They have to buy the manuscript from the agent, thus paying both the agency and the author. They have to pay their in-house team (editors, cover artist, marketing, legal, overseas rights, etc.) to get the book ready for production, and then they have to pay for the physical production of the book and thousands upon thousands of copies. Finally, they have to pay to ship those books out to book stores and Amazon, and they have to pay to promote the book. It’s a costly venture. The cost of publishing a single book for a traditional publisher can be well into the tens of thousands of dollars range, and they not only need to make all of that money back, they want to make a profit, too.

The bottom line is that a traditional publisher is going to do everything they can to minimize that initial risk by making sure every manuscript they take on is one that is likely to do well. In other words, they’re always going to look for books that follow “tried and true” formulas, because they know they’re probably going to sell well. The more a book strays from what’s known to sell well, the bigger a risk it presents. For that reason, books that stray from the usual formula are almost always written by established and successful authors. Why? Because established, successful authors have a built-in fan-base, so their name alone will drive much of the book’s sale. This grants some wiggle room in which the author and publisher can take bigger risks. They’re not going to do that with a debut author or an author with only a few books to their name. So, what can you do? These are your options...

1. Pursue Traditional Publishing with Another Manuscript

If you want to break into traditional publishing, you have to do it with a manuscript that falls in line with current trends and doesn’t push the boundaries too hard. Once you get published and have a few more formulaic books under your belt, if your books sell reasonably well, you can talk to your agent or publisher about the more risky manuscript.

2. Pursue an “Assisted Publishing House” (But Beware...) It’s super important to understand that any publishing house that makes you pay to publish your book isn’t an “independent publishing house” but an “assisted publishing house,” often called a “subsidy publisher” or “vanity press.”

An “independent publishing house” is a small traditional publishing house, meaning that you don’t pay them. They cover the costs of book production, just like in the bigger traditional publishing houses. The only difference is that you may not get an advance or may get only a very small one (hundreds of dollars vs thousands.)

The problem with assisted publishing houses (again, not the same thing as an independent publishing house) is that they are a breeding ground for scammers. They can look “legitimate” and still rob you blind. And, unlike traditional publishers (who don’t pay themselves until your book sells), most assisted publishers pay themselves out of what you pay them to produce your book. In other words, they’re not taking a risk by publishing your book. They get paid (out of your pocket) whether your book sells or not. And, despite what many of them claim, they simply do not have the same reach as traditional publishing houses as far as getting your books onto actual bookstore shelves.

The advantage to this kind of publisher, if you can find one that’s vetted by groups like ALLi, is that you don’t have to worry about doing all the footwork to get your book produced. You pay them and they do most of the work. It can also make a writer feel like they look more legitimate if they have what sounds like a traditional publishing house behind their book. And, obviously, since they’re not taking on a financial risk by contracting to publish your book, they’re much more likely to publish books that don’t follow current trends and known formulas for success.

3. Self-Publish (AKA “Indie Publish”)

The indie publishing industry has bloomed over the last ten years or so. The advent and popularity of e-books and the accessibility of indie author services has made indie publishing a more accessible, more viable route for writers whose books don’t follow current trends or “tried and true” formulas, and for writers who, for various other reasons, aren’t interested in the traditional publishing industry.

The main drawback to self-publishing is that many still view it as an inferior route to getting published, which is unfortunate because traditional publishers are just as likely to crank out some really awful books, and indie authors are just as likely to publish really fantastic, award winning fiction. The other drawback is that it’s a lot of work and it does cost money, though depending on how much you’re able to do on your own, it’s possible to publish an e-book (and even a print version) pretty much for free. The amount of money you put into your book is entirely under your control.

The benefit to being an indie author is you’re 100% in control of everything. You control the rights, you control the content, you get to decide on the title and choose what’s on the cover... no one can tell you what you can and can’t do. There are boat loads of services out there targeted toward indie authors, everything from editing and book formatting to cover design and marketing, all in a variety of price ranges. The indie author community is also strong and supportive, with lots of wonderful social media communities, not to mention organizations like The Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi) and The Association of Independent Authors. 4. Try Social Publishing

This is an emerging yet popular means of publishing that is cost-free and a great way for budding authors to find an audience. Ultimately, social publishing is when you post your story to a site where others can read it for free. Sites like Wattpad, Tapas, Swoon Reads, Booksie, and Underlined allow you to post your book so others can read it and offer feedback, and sometimes popular authors on these sites catch the attention of agents and traditional publishers. Alternatively, you can post your story in installments through your blog.

The downside, obviously, is that you don’t get a physical copy of your book and you don’t get paid. But the upside is that it’s free, there are few restrictions, and it’s a great way to help you find an audience for an unusual story, not to mention start to create a built-in fanbase. Having a built-in fanbase can be hugely important if you decide to indie publish, as well as if you decide to seek traditional publishing. You can also go on to open up a Patreon account, which at least gives you an option for making some money off the content you create.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I hope that one of these options will work for you. The important thing is to not get discouraged. Try to focus on the fact that you’ve gotten so many wonderful compliments about the manuscript. People love what you’ve done--they’re just too afraid to take a risk in publishing it, but the options above offer a variety of routes around that obstacle. Good luck and hang in there! <3

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

All of the info in that last reblog about writing a synopses is really useful and worth the read, but I wanted to echo what Raven said in her addition to it and add on a couple points of emphasis for querying writers to focus on when writing their initial query letters.

If you take away nothing else, based off of the almost unanimous agreement of every agent and every other author I’ve ever known or compared notes with in over a decade in and around the publishing industry, here are three of the most common mistakes querying writers make. If you even just avoid doing these three things, you can improve your chances of making it through an agent or editor’s slush pile IMMEASURABLY.

1) What Raven said, because this one is such, SUCH a biggie and I don’t know anyone who hasn’t done this at least once, or when starting out - DO NOT PLAY COY WITH YOUR ENDING. When querying agents or editors, forget about every impulse instilled by spoiler culture. You are not trying to tell them a story. You are trying to get them to represent your story or buy your story. They are not your audience, nor are they trying to be. They are industry professionals whose entire job is to be how writers GET in front of their actual audiences.

Most writers’ natural instinct is to leave a query or a synopsis on a cliffhanger in the hopes that an agent and editor will be intrigued enough they’ll request a partial read of your manuscript, or a full read. Don’t fall into the trap of viewing ‘getting an agent/editor to read my manuscript based off my query’ as your end goal. Its not. Your end goal is to get an agent/editor to buy or rep your manuscript. You have one shot to make a first impression. Its simply not in your best interests to hold back ANY cards. Put your best foot forward. Always. Always. Always. You do not have a guarantee of a chance at making a second impression, so there is literally no point in ‘saving your best for last.’ Plus, anyone can write a cliffhanger, pose questions that have someone interested in learning the answer. But that’s not a story, and its not a guarantee an author knows how to tell a full, complete story. A query letter is you pitching an agent or editor on your whole story, the beginning, middle AND end. They don’t want to see just your premise at a glance, they want and expect to see your premise and where its going, the point of it. Not just that you can set up an engaging conflict, but that you can resolve it too.

You want an agent or editor to enjoy reading your manuscript should you get it in front of them, obviously. Just be careful not to forget that doesn’t mean they’re reading manuscripts FOR enjoyment. Its their job. They’re looking for a work they can represent or sell, not just a satisfying read that they enjoy on a personal level. Tell them right there in your query letter just what exactly your story is and where it goes....THAT’S what gets them to request a full manuscript read. Not to satisfy their own curiosity and any questions your query brought up for them, so they can decide then if they even like the answers you crafted to those questions. But because the summation of your WHOLE novel already gave them the answers to those questions, they already decided they liked the sound of those answers, and now they want to read your whole manuscript so they can decide whether they also like how you take readers from Point A to Point B.

The quicker you can get an agent or editor any and all information they might need or want, the more you can pack into each step of the process and make the most of it, the fewer steps required for the agent/editor to get everything they need to make a decision on you - the better your chances.

2) Along related lines, another thing to be wary of is thinking that all of what I just said means more is better. Because this is another extremely common mistake so many authors make. Trying to cram everything possible into short query letters and synopses that can’t actually be expected to ever do the job of conveying EVERYTHING that you needed 90K words of actual story in order to convey in your actual manuscript.

No, all that will actually accomplish is to confuse agents/editors as to what in all of that they’re actually supposed to focus on as the most important, and usually just overwhelm them with minutiae that doesn’t actually contain any vital information so much as it just stands out as significant to you and thus you hope it’ll make an impression on them. Nine out of ten times it won’t, because the things that make it significant are the pages and scenes and chapters worth of context that lend those things weight.

Your query and/or synopses needs to be as streamlined as possible. Focus on essentials, and facts. Specific events in the story that advance the plot. What is your inciting conflict, what is your protag’s intended or proposed solution, what obstacles arise to get in the way of that, how do they adjust or compensate for that, how are things ultimately resolved. Bam, bam, bam. Rapid fire. Don’t waste time setting up your stakes and moving through that list, get to the point of each as quickly as possible. You don’t have a ton of room to waste in a query letter, be economical. You don’t need DETAILS. You don’t need an extensive breakdown of who, what, where, when, why and how for each step along the way. Boil your story down to its most significant highs and lows, and then boil each of those things down to their ultimate heart, the things that make those moments critical to the story.

If you’re having trouble packing everything into a query letter, you’ve condensed your story down as much as you possibly can and it still doesn’t seem to fit everything....stop. Take a step back. Look at the big picture: does your story simply have too many moving parts to boil it down any further while still containing the essential elements of each of those moving parts? This happens a lot with stories with ensemble casts or multi-POV novels. In situations like this, the best thing you can do is to aim for conveying the whole story...but through a more narrow focus. Pick ONE protag, even if you have five main characters and your novel cycles through each one of their POVs in alternating chapters. Make it clear in your query letter that it is in fact a multi-POV novel with five different main characters who are each equally crucial to the overall novel, with their own complete storylines with each having their own version of a beginning, middle and end to their personal stories-within-the-story....and then do every thing I just said above....but for just one of your main characters, and one only.

It might seem counter-intuitive, given that the point of the query letter is as I’ve said: to tell your whole story as concisely as possible and give an agent or editor all the information they need to decide whether or not it has all the ingredients/elements they’re looking for in a story, and now they want to see your full manuscript to see how well you combined all those things and used them to their best potential.

But here’s the thing - if each of your main characters is just as crucial to the story as the next, then each main character should in effect be a whole story unto themselves. Their beginning, middle and end might not give an agent/editor all the information or context needed to see how you resolved the entire conflict for the whole book, across all your multiple protagonists. BUT it will tell them everything they need in order to see how you resolved A story, that your plot has clear direction and where that is, that these individual characters’ arcs are equally essential to the big picture and where this one at least slots into that. This is essentially the cliffhanger version of querying, without ever actually resorting to using a cliffhanger.

Because here you’re using one focus as a sample of what they can expect for the others, selling them on this one character’s individual story as fully and thoroughly as you would sell them on your whole story were it a single POV, single protagonist story. And while its true that they’re only getting one fifth of the whole picture here, and they’ll need your whole manuscript in order to evaluate whether the other protagonists are just as essential to that big picture and you’re just as effective in telling their stories....you’re still giving them A complete picture, you’re showcasing your plotting and ability to craft a resolution as well as an inciting premise, etc.

They won’t be annoyed by an unnecessary cliffhanger here as you’re not teasing ‘if you want to know what happens next, you’ll just have to read the whole story.’ Rather, what you’ve actually provided them is ‘here’s what I did with one protag using this premise and faced with this conflict, and if you found that compelling enough on its own, my manuscript has four more protags with their own stories of comparative stakes, that I think are equally compelling.’

The bottom line here is even if your novel has multiple leads and follows several different characters and their POVs, any one of those characters and their personal journey needs to be able to hold a reader’s interest - otherwise it begs the question of whether that character’s POV is actually as crucial to telling a full complete story as you thought, and that’s something you might need to consider before moving forward. But as long as you affirm that each POV is equally worth telling, then any single one of them is in and of themselves an effective display of your ability to tell a complete and engaging story with a beginning, middle and end - which is exactly what an agent or editor is looking for in a query letter.

3) The third most common mistake - although perhaps not so much a mistake as just a lack - is the trickiest to address, and by that same token potentially the most important.

With all of the above having been said, its easy to see how many writers end up viewing their query letters as wholly set in the ‘professional’ side of writing-as-actual-job, and not at all in the ‘creative’ side. There’s a tendency upon whittling a story down to its bare essentials, to then basically ‘report’ those things in a query letter. Being dry and clinical about it, like a glorified series of bullet points. As easy it is to end up with something that’s more laundry list than story by the end of your query letter, that would be a mistake. Because an agent or editor needs the facts in your query letter, they need the bones, the framework, the aerial view of the big picture.....but there’s one last, equally fundamental element to every novel, and they need that in your query every bit as much.

That’s your voice.

The ‘know it when you see it’ part of a book, a narration, that turns a story into more than just a dry recitation of ‘then this happened and then this happened and this, and after that, Protag was very sad.’ The ‘I don’t know what’ that makes a story actually feel like a story, like whether its in 1st person POV or 3rd person POV, the reader isn’t just distantly viewing events with no emotional connection to them, but rather feels immersed in whatever the POV narrator is thinking and feeling, like they’re right there beside them or only a step removed from the action.

Voice is an extremely tricky thing to define, and even trickier to capture....and finding ways to instill it into your query letter itself, even with as little room as you have to work with, that’s easily the trickiest part of all. But that’s also what makes it arguably the single best indicator to an agent or editor that this writer is worth taking a closer look at, this is a story they need to read. And so the mere fact that so many query letters make the mistake of not even TRYING to include a sense of their main character’s voice while giving the agent/editor the facts of the story.....that’s why more than anything else probably, a lack of voice is what keeps 90% of query letters from ever advancing beyond the slush pile.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean write your query letter in the POV and voice of your main character. I’m pretty sure I’ve never met an agent or editor that didn’t find that gimmicky and annoying as hell - it definitely does happen, and they almost all give the same advice about it: Don’t.

It just means....don’t waste time in jumping right into the meat of your story in your query letter, in delivering all the essential facts....but try and write it in the same style you wrote your actual manuscript, make it a kind of preview of your novel’s stylistic voice and feel. Obviously pacing is a large part of what makes each voice distinct, and there’s simply no way the pacing of a query letter is ever going to be a reliable indicator of how your novel is paced and how that carries over into its voice, the rhythm and flow of your words and the rise and fall of action just page by page or in single scenes. But aside from pacing, to whatever degree you can possibly manage, try and carry as much of your novel’s voice as possible over into its query letter. Aim for being able to insert your query letter into the middle of your manuscript at the start of any random chapter, and see how jarring or not it is to read the end of the previous chapter and then segue straight into reading that query letter, see how seamless or not of a transition there is, how much the latter still ‘feels’ and ‘sounds’ like the chapter you just finished reading.

It’s much easier said than done, but when you can and do manage it, it really can make all the difference.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Cult of Celebrity and Fashion Design

(I touched on this on my twitter @ginnyzero.) If there are two things that I’ve noticed writing and fashion design have in common is that everyone thinks they can do them. It can’t be all that hard to write a book or come up with a bunch of clothes in the same design and theme. I mean, anyone can write a fiction book, you don’t need to go to school for that. (It doesn’t mean that everyone has the talent or stamina to do it!) There are famous designers that didn’t go to school, that means it can’t be all that difficult.

And so enter the celebrities who are looking to increase their name awareness and expand their brand into the world of fashion design and fiction book writing. Kanye West, Heidi Klum, Kelly Osbourne, Tyra Banks, Amber Benson, Nicole Ricci, Gwen Stefani, that female country singer I can’t remember the name of. Hell, even companies like Kohl’s get into it having lines in their store designed by celebrities like Avril Lavigne. Now, some designers like Mary Kate and Ashley Olsen seem to have turned their brand into a real business. Nicole Ricci is more serious. Amber Benson has an entire series of books. (I barely got through book one despite the cool premise. Take from that what you will.)

Now, I’m glad of these celebrities success! I wish them all the best in the world. I’m happy they have their fame and their fortune from acting, singing and so on. That’s great.

I find their forays into fashion and make-up and book writing to be suspect. I can’t speak of their motivations. I don’t know if their passion truly lies in fashion versus music. (Though I doubt it in some cases.) I have to question why they decide to enter another creative field when it feels like it is supposed to fuel or be fueled by their other creative field.

Look, I’m a writer and a fashion designer. I’ve been doing both for about the same amount of time. I’m going to tell you right now that my writing and my designing have very little to do with each other. People find descriptions of clothes in books to be boring and they don’t go to clothing stores to buy books! (And I do notice that GRRM and JK Rowling aren’t creating fashion labels. Hmmm.)

The fashion field is similar to the corporate field. You have to work your way up a ladder. Most designers don’t jump out of fashion school straight into the design business of their own label. For one, they don’t have the money. And for two, they tend not to have the business skills. (Design and fashion business are two different majors, go figure. In fact, most schools don’t offer fashion business. They offer fashion merchandising, but not fashion business.)

Fashion designers that are starting out tend to spend at least ten years working for other people. In these ten years a lot of them burn out and decide to leave the field for the next crop of fashion hopefuls to find out how unglamorous working in fashion really is. They pay is low. The cost of living in a city is high. There is very little room for advancement.

And in book publishing, traditional publishers only put out so many books in a year. Hundreds and hundreds of hopefuls query agents putting their hopes and dreams and magnum opus works into a slush pile on the dream that they’re good enough to get a publishing contract. Most of them never get more than a rejection notice that gives no reason other than “I’m not feeling it at this time.” Your book, no matter how good it is, is not what the agent is looking for right that second because it might be the wrong age category or have a spelling mistake or they’ve seen too many vampires today. (The main problem with this being is that you don’t know what is wrong with the book or if it “Just isn’t the right time to try and sell this book” because they don’t tell you.)

Fashion isn’t a zero sum game. Business isn’t a zero sum game. (Book publishing in the traditional manner seems to be closest.) Just because a celebrity like Kanye starts a fashion label and does a show doesn’t mean that an up and coming designer can’t do the same thing. Kanye has two things over a designer that’s not a celebrity, money and a brand name.

Now a celebrity that writes a book and there are so many slots that a publisher is willing to print in a year and they have the choice between the celebrity and another author and they choose the celebrity, then yes, that other author loses their publishing chance because next year may not be a good time for their book. So, it becomes more of a zero sum game. Sure, the author can go indie and publish themselves but take it from an indie author it is a lot of work and it is not the same.

Celebrities, to an extent, skip ahead of the line both in fashion and in publishing. Celebrities have a name. They have a brand. They have power and money to invest. They don’t go to school to learn to design a collection. They pull swipes from magazines and hire others to do it for them most the time. There are exceptions to this rule of course. I’ve mentioned them, like the Olsen twins. They’re exceptions. Just like Tom Ford not going to school for fashion and Vera Wang being unable to drape and draw are also exceptions to most of the fashion industry.

Because celebrities have a name, investors and magazine editors and publishing houses are much more willing to go with someone that the common person is going to recognize and has a huge marketing machine in place than a young and upcoming designer with fresh in the moment ideas or a book writer that no one has heard of. The up and coming designer, the unknown book writer, they are too much of a risk. The publisher, the investor would have to put more money into setting up a marketing machine for them. They’d have to do more advertise. It’s more money out with less guarantee of money coming back in!

The celebrity is just good business.

So, in order to even get a deal, many writers and yes, fashion designers, feel they have to create a social media following and a brand before they finish or query their book to try and prove they have people following them. (And I’m going to tell you right now that follows and likes do not equal sales of original works.) Fashion designers try out for reality shows like Project Runway to get a chance to put their face out there and get some recognition. $125,000 goes really fast in the fashion world and that is the high end of a reality show cash payout.

There aren’t a lot of Christian Siriano’s for a reason. Christian Siriano had savvy and chutzpah after the show and delivered. His success was less on Project Runway and more on using Project Runway as a launching pad to get what he wanted and being able to follow through! (I mean, good on him.)

To me, having 35,000 people follow you on Instagram because they like the pictures of the books you’re reading doesn’t mean to me that those same 35,000 people are going to buy the books you’re writing. And if an agent and publisher falls for that, that’s on them. (To me that says you’ve spent way, way too much time on Instagram and other people’s books rather than writing.)

Fashion designers that go to school and writers no matter what university track they went through, fanfiction or traditional, work really hard because they had passion for what they do, learned the skills and struggled one way or the other in very competitive industries now have to face off against a celebrity that are most likely only trying to increase their brand awareness to have their name on more things and have the money to make it happen.

Then fashion designers also have to face the competition of the big established brand houses that are owned by huge corporations. Most of the large fashion brands are owned by LVMH or by Fendi. The same is in traditional publishing, there are six major publishing houses and all other publishing houses are owned by them. Television is just as bad! These big companies buy their advertising in blocks in the major magazines essentially. Runway shows cost at least 100,000 dollars per season. Fashion weeks tend to have corporate sponsors for very good reasons.

In this world, it’s hard for the small designer, the unknown writer, to get their little voice to be heard against the loud yelling of big corporations, celebrities and social media.

I wish celebrities all the success.

They also frustrate me. These people are also creatives. Some of them were poor and barely making it before being “discovered.” In order to be successful, they had to be creative and good in the fields that first launched them into fame! And instead of using their fame and fortune to help people in other creative fields, they barge into those creative fields and try to use their name to style themselves as experts. Because yes, to design a collection, there is expertise involved. I wrote an entire seven post series on what it takes to simply design a collection and that didn’t cover the sample making and the model fittings and the actual manufacturing process!

Writers also go through long processes to write books with the world building and the character making and creating this thing called plot and having the characters talk to each other and have emotional and personal growth arcs. Then they get nitpicky about sentence structure and repeated phrases and did I use that word too many times?

As a fashion designer and a little known writer, if you’re a celebrity and you want to dabble in fashion design or your agent things you should write a book, turn around and pay it forward by sponsoring someone in that field already instead.

As I said on twitter, celebrities can treat a little known fashion designer as a business investment instead of treating the field of fashion like an extension of their branding and marketing. Sponsorship and investments by celebrities of the day and by nobles and major businessmen were how many of the major older fashion houses started.

The payoff will be different. The byline won’t be as big. Sure, there will be money because of course they’ll want a return on their investment. But there is also the emotional payout. “I helped someone else achieve my dreams the way someone else helped me achieve mine.” “I helped start that brand. I helped build it.” Be the positive change you needed back when you were struggling. Sponsor a designer, any ethnicity, any gender. Invest in their talent.

There’s a reason why I’m more willing to support someone like Vin Diesel, than I’m willing to support someone like Kanye. Vin’s not only using his money to help people, he’s focusing on what he’s good at making movies, so he can make more money to help more people.

I feel like a lot of this can be laid at the feet of the 80s when shoe designers started having sports celebrities “design” and endorse their shoes. By the time I hit college, celebrities had already entered the designing landscape and they haven’t left, picking up and dropping projects and slapping their name on things for a couple seasons before chasing something else. None of the students and indeed very few if any of the teachers talked about this in a positive light. They didn’t see how having celebrities as designers helped the fashion community or helped the rest of the world take fashion more seriously.

(Despite the fact everyone has to wear clothes, most the world finds the world of fashion ridiculous. Things like the Devil wears Prada and actual true stories from the fashion world and people in the fashion world don’t help.)

Celebrities were seen as road blocks and rivals that hadn’t earned their title as rivals. They were taking jobs from us. The students and teachers didn’t see them as job creators, especially since the celebrities were sending their manufacturing overseas like everyone else. If celebrities could step into the fashion world without an education and try to fake it and make it instead of employing actual designers, why were we even at school? What as the point? We felt doomed before we even graduated.

Think of a world where instead of starting his own fashion line (that no one takes seriously other than Kanye) if Kanye had sponsored someone like Edmund or Anthony or any of the male black fashion designers from Project Runway and launched them into success. What happens when a celebrity other than Oprah says “I read this obscure book by little known author and loved it?”

What happens when creatives in different fields get behind each other instead of putting themselves into competition with each other?

If I was a famous fashion designer, I wouldn’t go and lay down a music track and think that means I should be successful in music or that it should enhance my brand to have music as well as clothes. It’s not that I don’t have a decent voice, because I do. It’s because my passion isn’t music. My passion is fashion. My passion is writing. So, I wish that these musicians and actors would have the same respect for my field(s) as I have for theirs.

Right now this feels really important to me as I finish up my branding portfolio and try to think ahead about where I can get a creative job in fashion or branding or any creative consulting/interior design, hell, I'll be a wedding shop consultant at this point. It's an issue that hasn't gone away. I don't foresee it doing so in the near future either.

0 notes