#ancient greek theater

Photo

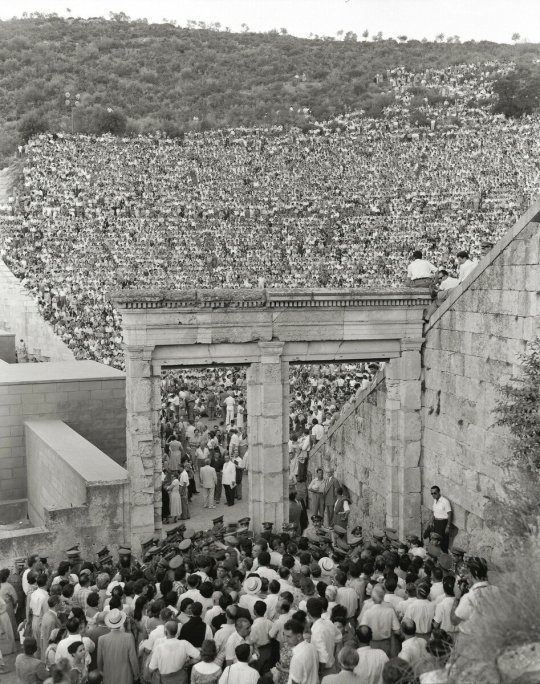

Ancient Theater of Epidaurus, Greece, 1956. People gather to watch Anna Synodinou in Sophocles’ Antigone, directed by Alexis Minotis.

#greece#ancient greek theater#antigone#black and white#sophocles#theater#epidaurus#argolis#peloponnese#argolida#peloponnisos#mainland#anna synodinou#greek culture

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

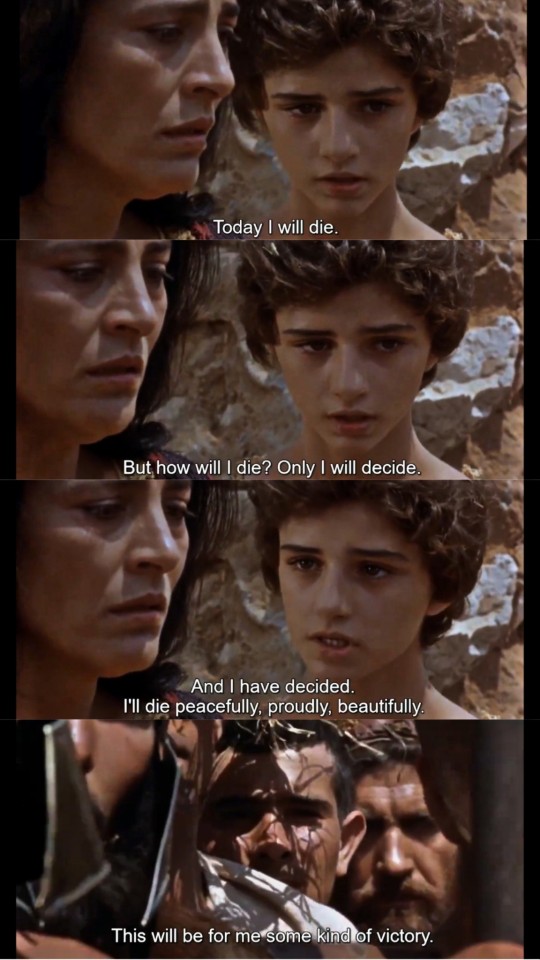

Clytemnestra was way too lenient I wouldn’t have stopped with just killing Agamemnon I would’ve hunted down every single surviving Greek leader that stood by and did nothing (or worst straight up participated) as my daughter was slaughtered like an animal.

#including and especially Odysseus#greek mythology#ancient greek mythology#greek pantheon#greek myths#greek tragedy#clytemnestra#iphigenia#iphigenia 1977#agamemnon#tagamemnon#Odysseus#Euripides#ancient greek theater

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Stronger than lover's love is lover's hate. Incurable, in each, the wounds they make.”

Euripides, Medea 431 BC

Art: Battling pegases by George Ford Morris 1925

#art#dark academia#classical art#dark aesthetic#classic literature#ancient greek theater#pegasus#illustration#greek mythology

361 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Oedipus Project (or, How Oedipus’ Historical Context Reveals the Play’s Meaning)

Sooo back in Spring 2020, Oscar Isaac starred in a Zoom production of Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus — The Oedipus Project. I highly recommend watching the production. Oscar gives a uniquely genuine performance of Oedipus. Thankfully, @hupperts linked to the full livestream in a post (it’s a Google Drive link you can watch here).

But I would be remiss in talking about Ancient Greek theatre if I didn’t also share a few historical facets of the play (and of Greek Theatre in general) that are often overlooked in modern productions. (For context, my college major was Classical Theatre — with an emphasis on Ancient Greek theatre and Shakespeare. So Ancient Greek Tragedy is still a big special interest.)

The Original Actors:

In Sophocles' and Euripides' tragedies, there were only three actors (all adult men), plus a Chorus of fifteen young men, led by a Chorus Leader. (Aeschylus before them had two actors, plus a chorus of twelve young men.)

Since there are more than three characters in these plays, it was standard for several (if not all) of the three actors to play multiple roles. The roles that these actors played often relate to each other, creating many subtextual layers of connection and meaning between the characters.

Read more below the cut:

The Three Actors and the Chorus:

In Ancient Greek theatre, the lead actor was called the Protagonist. This was often the most senior actor and the one deemed most skilled.

The second actor was called the Deuteragonist. This actor often had less seniority than the Protagonist, though they were often deemed to be of equal skill level.

The third actor was called the Tritagonist. This actor was often the youngest and least experienced of the three, and they would often play Messenger roles.

The Chorus comprised a Chorus Leader, leading a Chorus of 15 young men. They chanted and danced in unison, with certain lines spoken/sung solo by the Chorus Leader.

Singing, Dances, and Masks in Ancient Greek Theatre:

Ancient Greek theatre was first and foremost a religious ceremony, dedicated to the god, Dionysos. The plays were written in meter, and the actors would have alternated between speaking their lines and singing the text. The Chorus performed circular dances, and they also sang and chanted their lines. The actors were accompanied by a musician playing a double-piped reed instrument called the aulos (the sound would have been similar to a modern-day oboe).

The three actors and the Chorus all wore masks and costumes. These masks were religious in nature — they permitted the actors and Chorus to interact with the divine nature of Dionysos (which was believed to be present on the theatre stage) without being overcome by the god. In Ancient Greek theatre, masks do not conceal; instead, they reveal the truth. The masks also served a practical purpose, allowing the actors to switch between their characters with relative ease.

The Roles Played by the Three Actors and Chorus in Oedipus Tyrannus:

Here is the original cast list from Oedipus Tyrannus (this is my reconstruction, based on exits and entrances).

1st Actor (Protagonist):

Oedipus (King of Thebes, who unknowingly murdered his father, King Laius, and who married his mother, Queen Jocasta; he became the new King upon defeating the Sphinx at Thebes by solving her riddle)

2nd Actor (Deuteragonist):

Priest (Priest of Apollo)

Tiresias (blind prophet and servant of Apollo)

Queen Jocasta (Queen of Thebes, unknowing wife of her son Oedipus, and former wife of King Laius, Oedipus' father)

Theban Shepherd (who saved the infant Oedipus from death and gave him to the Shepherd and Messenger from Corinth)

3rd Actor (Tritagonist):

Creon (Brother of Jocasta, Queen of Thebes, and unknowing uncle of Oedipus)

Corinthian Messenger (the Shepherd who brought Oedipus to his adoptive parents in Corinth)

Theban Messenger (the Messenger who delivered the news of Jocasta's death and Oedipus' blinding)

Chorus Leader, leading a Chorus of 15 young men:

The Elder Citizens of Thebes (the Chorus serve as the point-of-view character through which the audience is meant to intellectually and emotionally understand the play)

The Connections Between the Three Actors and Their Roles:

The Protagonist in Oedipus played one role: Oedipus. In Greek Tragedy, the lead role was deemed to be of such importance that the Protagonist was often given no other roles to play.

The Deuteragonist had to shoulder some of the most important moments in the play. They opened the play as the Priest of Apollo. They played Tiresias and then Jocasta, both wrestling emotionally with Oedipus. And finally, they played the Theban Shepherd, who is tortured into his confession of saving the baby Oedipus from certain death. The fact that the Deuteragonist portrays all of these roles provides a common thread between them, linking together characters who unknowingly lead Oedipus to his downfall.

The Tritagonist played Creon as well as the two Messenger roles. As the Theban Messenger, they would have been expected to deliver a dramatic and scene-stealing monologue about the death of Jocasta and the blinding of Oedipus, which would have given the younger actor some scenery to chew.

The Historical Context of Oedipus Tyrannus:

Something to note about Oedipus Tyrannus in the context in which it was written: the original meaning of the play is different from the Freudian themes that we normally associate with it. Freud took Oedipus and used it as an exploration of unconscious desires, but that wasn’t really Sophocles’ intent.

When Sophocles wrote Oedipus Tyrannus, Athens was beginning the second half of the great war with Sparta (the Peloponnesian War), which would ultimately lead to Athens’ downfall, as well as Sparta’s downfall not long after.

About 50 years prior, Athens and Sparta had fought together in the Persian Wars to prevent the Persians from conquering Greece (if you’ve ever seen the movie 300, that’s what it is about). But in the intervening decades, Sparta and Athens had become rivals for resources and land within Greece, and between 460 – 445 BCE, and 431 – 404 BCE, they fought two bloody wars that ultimately led to the defeat of Athens, and the end of the Athenian Democracy.

Many Athenians, including the playwrights Sophocles and Euripides, were incredibly nervous about this conflict, and foresaw that it would lead to prolonged bloodshed and even the city’s downfall.

For example, around the same time that Sophocles wrote Oedipus Tyrannus, Euripides wrote Medea, about a woman who murders her children to spite her husband — Euripides was effectively saying, “If these two powers of Sparta and Athens, mother and father, go to war with each other, all that we will succeed in doing is murdering our children (the young soldiers who will die in battle).”

Oedipus Tyrannus is about a king who wants to be a great ruler for his city, Thebes. And yet, he cannot know how to lead his city, for he does not even know himself.

Many years before the start of the play, he had defeated the Sphinx who had camped out outside Thebes’ city walls and was consuming the city’s inhabitants. She demanded that everyone who passed by her must answer her riddle. If they could not figure it out, she would eat them.

She asked them, “What creature walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at noon, and three legs in the evening?”

No one in Thebes could answer her riddle, and so one by one, she devoured them, simultaneously consuming the city’s soldiers and starving out the city’s inhabitants.

Around the time that the Sphinx was laying waste to Thebes, Oedipus was running from himself. Oedipus had received a prophecy that he would “kill his father and marry his mother,” so he left his city of Corinth and ran far away from his (adoptive) parents (though he didn’t know that he was adopted).

Along the way, Oedipus encountered an old man who attacked him at a crossroads. In anger, Oedipus killed the man, and kept going (unbeknownst to him, this was his father, Laius, the King of Thebes).

He soon happened upon the city of Thebes, and encountered the Sphinx. Like she had done countless times before, she asked Oedipus her riddle. But unlike the others before him, Oedipus used his intelligence and cunning to defeat her.

Oedipus understood what the Sphinx was asking, and he answered her riddle correctly. The answer is “man.” Man walks on four legs in the morning (crawling as a baby), on two legs at noon (walking upright in the prime of his youth), and on three legs in the evening (using a cane to walk in old age).

Oedipus knew “man,” but he did not know himself.

Still, the Sphinx was defeated, and Oedipus was welcomed into the city of Thebes as a hero. The old king had just died, and the city was in turmoil. They were looking for a new king. The old king’s brother-in-law, Creon, did not want the throne, and so the city decided to adopt Oedipus as their new king and leader. The Queen, Jocasta, willingly married this young man who had saved her and her city. They wed and had four children together: two sons, Polynices and Eteocles, and two daughters, Antigone and Ismene.

(Of course, these children would continue the twisted generational trauma of their family, as brother would turn against brother, sister against sister, and uncle against niece and nephew, until the family had consumed itself from the inside out.)

Oedipus’ Hubris:

Oedipus learns several important lessons from this incident. However, these lessons ultimately lead to his downfall:

1) He can defeat any enemy through argument, both in terms of aggression and cunning. He defeated the old man who attacked him (his own father) through aggression, and he defeated the Sphinx through cunning.

2) His intellect and reason are more powerful than even a superhuman force (the Sphinx), and he can threaten to banish or execute anyone who tries to challenge his understanding of things. He creates an echochamber from which he cannot escape.

3) He must continue to run away from his past, and never look at himself too deeply. He must never “know himself” or engage in any deep self-analysis because he believes that he is still running from the prophecy. He doesn’t realize that he already fulfilled the prophecy years before, and soon his punishment will come due.

In his Oedipus Project performance, Oscar did a masterful job at making Oedipus' guilt clear, and at laying out his hubris. Oedipus’ anger and insistence in his own righteousness ultimately bring him down.

Oedipus' haughtiness is a protection against the fear and inadequacy he feels in his life. He has felt like an outsider for much of his life, and he is overcompensating for that. He feels that he must prove himself right in all arguments, because deep down, he knows that he’s not who he thinks he is.

Oedipus is terrified to look at the “truth,” because he suspects that he'll be looking in a mirror.

The downfall of Oedipus is that he resists the truth of himself that is staring him in the face. He won't see until he literally blinds himself, and then when he is blinded, he can finally see, but by then it is too late.

Athens’ Hubris:

Like Oedipus, Athens believed it could defeat any enemy through cunning and aggression. Years before, it had decisively routed the Persians in the Battle of Salamis, driving the Persian forces away from Greece and ending the war. In the same way, it believed that it could use cunning and aggression to defeat Sparta. Sparta and Athens were like mirror selves. They were the two parts of the whole that made up what it was to be Greek.

Like Oedipus, Athens’ rulers were hubristic, and believed that they could know what was best for all of Greece, and yet they didn’t even know what was best for their own city.

Thebes, Oedipus’ city, had sided with Persia during the Persian Wars. During the Peloponnesian War, it sided with Sparta. To the Athenians, Thebes was the Anti-Athens. But by basing this critique of Athens in a city that was seen as an enemy, Sophocles was effectively looking at Athens “through the mirror,” and recognizing that self and reflection of self are two parts of the same whole.

So, unlike the modern Freudian characterization of Oedipus, Sophocles’ intention was to explore the way that a political entity can become entirely corrupted by its leaders. These leaders argue themselves in circles, round and round, until they eventually come face to face with themselves. In that moment, it is shown that they have not been fighting against any external enemy, they have been destroying their own city from within, and in their own immolation, they burn the city as well.

Oedipus Tyrannus is a great exploration of generational trauma — it shows in microcosm the way that toxic dynamics are passed down over and over to create an inheritance of destruction. If Jocasta and Laius had loved their son despite Apollo’s prophecy, if they had sought to wrestle with the god instead of blindly following him, if they had treated their son with care instead of piercing his ankles and leaving him on a hillside to die, their downfall and his would never have occurred. Their compulsion towards the very predeterminism they feared sealed their fate.

In the same way, Athens' and Sparta's fear and enmity towards each other ultimately led to Athens' downfall and Sparta's decline not long after. In trying to destroy one another, Athens and Sparta learned far too late that they were only destroying themselves.

The Anti-War Message of Ancient Greek Tragedy:

Ancient Greek Tragedy dealt with deeply human themes, such as psychology, philosophy, religion, politics, and art. Above all, it dealt with what it is to be a nation at war.

The Athenian Democracy was bookended by two great wars: the Persian Wars, which culminated around 480 BCE, and the Peloponnesian War, which concluded in 404 BCE when Sparta defeated Athens.

Within that span of roughly 80 years, the Greek playwrights engaged in a complex discourse, addressing their existential feelings of being a society defined by both internal and external conflict. They warned about the horrors of war, and they strove to use their art to steer the ship that was Athenian Democracy.

When we understand Ancient Greek Tragedy within its historical context, we can see that it is just as relevant today as it was when it was written over 2400 years ago.

#oscar isaac#the oedipus project#oedipus rex#ancient greek tragedy#ancient greek theater#oedipus tyrannus

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

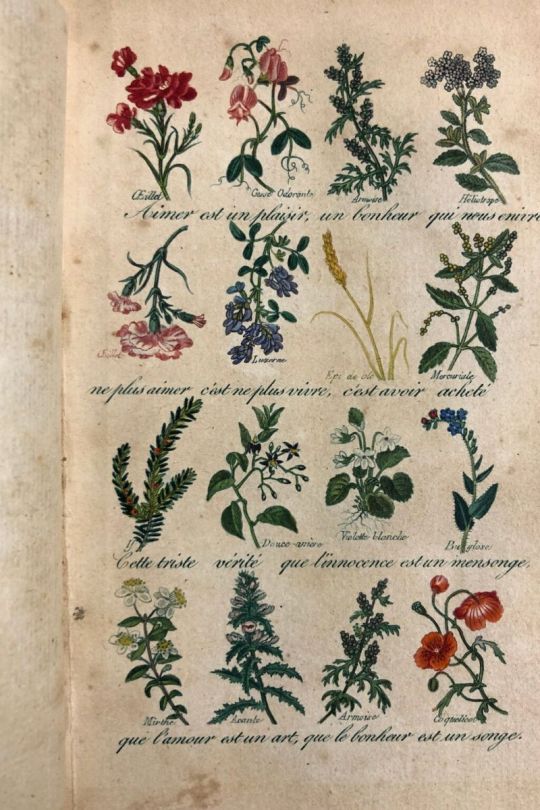

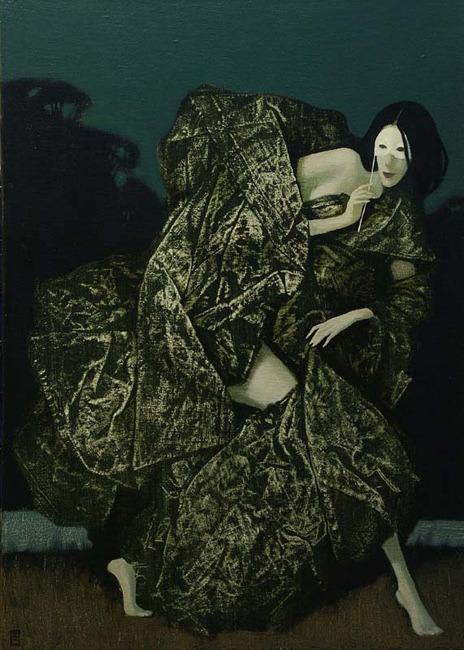

mood board | Unit 3 ALA Task 1 - staging a play that resonated personally with you

for this task I chose ‘Antigone’ by Sophocles and decided on an outdoor/open-air staging, using Victorian flower language as potential signifiers (used to articulate the multiple layers of themes and topic explored in the play, such as death, marriage, women’s rights, pride, religion, traditions & customs etc)

flowers would be used as stage decor as well as props used by the actors and actresses; for example white and purple hydrangeas to symbolise Creon’s hubris (false pride)

the actors and actresses would wear simple black or white masks

I would like each scene and staging of actors and actresses to remind of pre-raphaelite paintings, which are loaded with signifiers and symbolic flowers

also, the death scene of Antigone and Haemon (they kill themselves) would be staged as a Pas de deux (involving physical movements and dancing), reminding of the end of the second act in the ballet ‘Giselle’ (where white lilies are used as signifiers, as they symbolise death, grace and purity, and are therefore often present in depictions of the Virgin Mary)

#theatre studies#theatre#theatre academia#theatre aesthetic#aestheitcs#moodboard#antigone#sophocles#ancient greek theater#preraffaelliti#pre raphaelite#giselle ballet#flower language#victorian era#studyinspo#study blog#studyblr#studygram#student life#student#university#college student

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've come to dislike how non Greeks (most likely native English speakers because I've seen this happening mostly by them, but of course they're not the only ones) who have taken like 1 or 2 years of Greek or Ancient Greek at university, carry themselves as they've now become very educated on the language and the culture as well, and they're treated as such by everyone!

Like, I believe Tom Hiddleston claims to speak Ancient Greek, or maybe others have claimed that for him but, my dude, the Erasmian pronunciation is wrong.

And just last night, I finished Stephen Fry's book called Mythos and in the end, there is a guide on how to pronounce the names which can be limited to "Just do it the way it's easier for you, Greeks do it their way, Brits and Americans do it their way, there is no correct answer." No. I've been taking English lessons since I was 3, but still mispronounce and mispell a lot of stuff. You don't see me coming and making comments on the correct way to speak English, so maybe don't comment on the correct way to speak Greek, since you're not a native speaker.

And last but not least, dishonorable mention to the author Monica Gutierrez, who in one of her books, through a character that, if I'm not mistaken, is an archaeologist, says that the Parthenon Marbles that were stolen from us and are currently in the British museum don't have to return to Greece, because 'they belong to the whole world'. They belong to the whole world, but they were made here, and I, a Greek person, have to buy a ticket to England in order to see them, because a British smuggler got the permission to take them away, by the people who had us enslaved for 4 centuries. And to this day, the British keep on using stupid excuses because they don't want to give them back!

And yet, those are the people whose voices and work will get picked over the work of actual native people. For example, there is a Greek youtuber that is an archaeologist and makes videos about mythology (sometimes he does videos on Scandinavian and Egyptian mythologies too, I hope those are accurate) and ancient art and he has just released a book. I highly doubt his book will get picked by publishers, to get translated in other languages and be released outside of Greece, even though I encourage you to check him out.

I don't claim that this happens only to Greek people/language/culture, but it's the only one I can comment on ☺

#scorpion-flower#we were the kings and the queues#greece#aegean sea#greek islands#cyprus#greek#greek history#greek post#greek aesthetic#greek mythology#greek status#crete#ancient greek#ancient greece#ancient greek theater#ancient greek art#ancient greek memes#ancient greek mythology#erasmus was dutch and someone i know has claimed that erasmus believed that greeks have ruined their language#yes dutch person please enlighten us poor greeks on how to properly speak our language#but even if that's not what he believed#the erasmian pronunciation is wrong#i am especially disappointed by fry#tom hiddleston#stephen fry#mythos#greek mythos#parthenon marbles

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

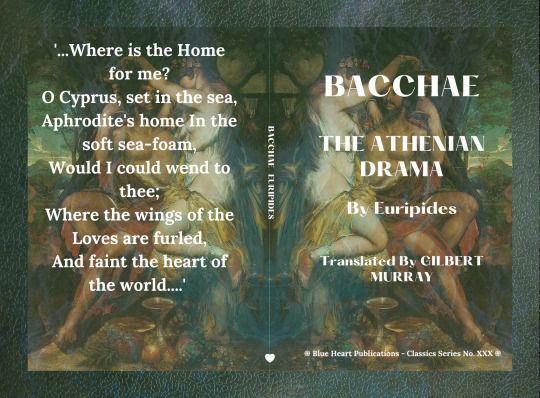

Dionysian Delirium Unleashed: A Riveting Odyssey into Euripides' Bacchae

Euripides' timeless masterpiece, "Bacchae," as brilliantly translated by Gilbert Murray, serves as an electrifying exploration into the essence of human nature and the intoxicating power of the divine. This Athenian drama unfolds with an enigmatic title that hints at revelry, and indeed, the narrative plunges the audience into the captivating chaos of Dionysian rites. Murray's translation masterfully captures the raw energy and mysticism of the original text, plunging readers into a world where reason battles ecstasy, and the boundaries between mortals and gods blur into a thrilling dance of delirium.

The play centers around the god Dionysus, who descends upon Thebes to assert his divine identity. The portrayal of the erratic and orgiastic rituals of the Bacchantes, led by the charismatic yet enigmatic Dionysus, becomes a metaphorical journey into the deepest recesses of human psychology. Murray's linguistic prowess and sensitivity to the nuances of ancient Greek bring forth the rich tapestry of tragedy, ecstasy, and divine intervention that permeates every scene.

As the tension between Dionysus and the skeptical King Pentheus escalates, the audience is drawn into a complex web of power, belief, and the consequences of denying the divine. Murray's translation skillfully weaves together the poetic and the profound, ensuring that the play's philosophical undercurrents are as resonant today as they were in ancient Athens.

"Bacchae" is more than a dramatic spectacle; it is a philosophical inquiry into the nature of faith, reason, and the consequences of defying the divine order. Murray's translation adds a layer of accessibility without sacrificing the original's poetic brilliance, making this rendition an ideal entry point for both seasoned scholars and newcomers to Greek tragedy.

In conclusion, "Dionysian Delirium Unleashed" is a riveting journey through the mystical and tumultuous realm of "Bacchae," inviting readers to question the boundaries of sanity, embrace the divine within, and confront the consequences of resisting the call of the god of wine and revelry.

"Bacchae," of Euripides skillfully translated by Gilbert Murray is available in Amazon in paperback 10.99$ and hardcover 18.99$ editions.

Number of pages: 152

Language: English

Rating: 8/10

Link of the book!

Review By: King's Cat

#Euripides#Bacchae#Athenian drama#Greek tragedy#Dionysian rituals#Divine ecstasy#Gilbert Murray translation#Ancient Greek theater#Thebes#Dionysus#Pentheus#Bacchantes#Tragedy and ecstasy#Greek mythology#Theater of the absurd#Ritual madness#Divine intervention#Theatrical mysticism#Power and belief#Mythological transformations#Greek classics#Poetic brilliance#Dramatic tension#Philosophical inquiry#Religious symbolism#Classical literature#Mythic confrontation#Enigmatic revelry#Athenian culture#Theatrical exploration

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dionysian Delirium Unleashed: A Riveting Odyssey into Euripides' Bacchae

Euripides' timeless masterpiece, "Bacchae," as brilliantly translated by Gilbert Murray, serves as an electrifying exploration into the essence of human nature and the intoxicating power of the divine. This Athenian drama unfolds with an enigmatic title that hints at revelry, and indeed, the narrative plunges the audience into the captivating chaos of Dionysian rites. Murray's translation masterfully captures the raw energy and mysticism of the original text, plunging readers into a world where reason battles ecstasy, and the boundaries between mortals and gods blur into a thrilling dance of delirium.

The play centers around the god Dionysus, who descends upon Thebes to assert his divine identity. The portrayal of the erratic and orgiastic rituals of the Bacchantes, led by the charismatic yet enigmatic Dionysus, becomes a metaphorical journey into the deepest recesses of human psychology. Murray's linguistic prowess and sensitivity to the nuances of ancient Greek bring forth the rich tapestry of tragedy, ecstasy, and divine intervention that permeates every scene.

As the tension between Dionysus and the skeptical King Pentheus escalates, the audience is drawn into a complex web of power, belief, and the consequences of denying the divine. Murray's translation skillfully weaves together the poetic and the profound, ensuring that the play's philosophical undercurrents are as resonant today as they were in ancient Athens.

"Bacchae" is more than a dramatic spectacle; it is a philosophical inquiry into the nature of faith, reason, and the consequences of defying the divine order. Murray's translation adds a layer of accessibility without sacrificing the original's poetic brilliance, making this rendition an ideal entry point for both seasoned scholars and newcomers to Greek tragedy.

In conclusion, "Dionysian Delirium Unleashed" is a riveting journey through the mystical and tumultuous realm of "Bacchae," inviting readers to question the boundaries of sanity, embrace the divine within, and confront the consequences of resisting the call of the god of wine and revelry.

"Bacchae," of Euripides skillfully translated by Gilbert Murray is available in Amazon in paperback 10.99$ and hardcover 18.99$ editions.

Number of pages: 152

Language: English

Rating: 8/10

Link of the book!

Review By: King's Cat

#Euripides#Bacchae#Athenian drama#Greek tragedy#Dionysian rituals#Divine ecstasy#Gilbert Murray translation#Ancient Greek theater#Thebes#Dionysus#Pentheus#Bacchantes#Tragedy and ecstasy#Greek mythology#Theater of the absurd#Ritual madness#Divine intervention#Theatrical mysticism#Power and belief#Mythological transformations#Greek classics#Poetic brilliance#Dramatic tension#Philosophical inquiry#Religious symbolism#Classical literature#Mythic confrontation#Enigmatic revelry#Athenian culture#Theatrical exploration

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝗔𝗻𝗰𝗶𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗮𝗿𝗰𝗵𝗶𝘁𝗲𝗰𝘁𝘂𝗿𝗲 𝗼𝗳 𝗔𝘁𝗵𝗲𝗻𝘀

•Socrates & Confucius: An Encounter

•Odium of Herode

music hall

•Temple of Athena Nike

•Temple of Erechthion

East dedicated to Athena

North dedicated to Poseidon

•Parthenon

•bench sculpture

#greece#greece travel#travel#ancient greek mythology#ancient greek philosophy#ancient greek history#ancient greek statue#ancient greek theater#ancient greek culture#ancient greek art#ancient greek religion#ancient greece#ancient architecture#honeymoon#baroque#baroque architecture#explore#travel photography#beautiful destinations#destinations#wanderlust#tourism#travel blog#traveltheworld#athens#acropolis

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

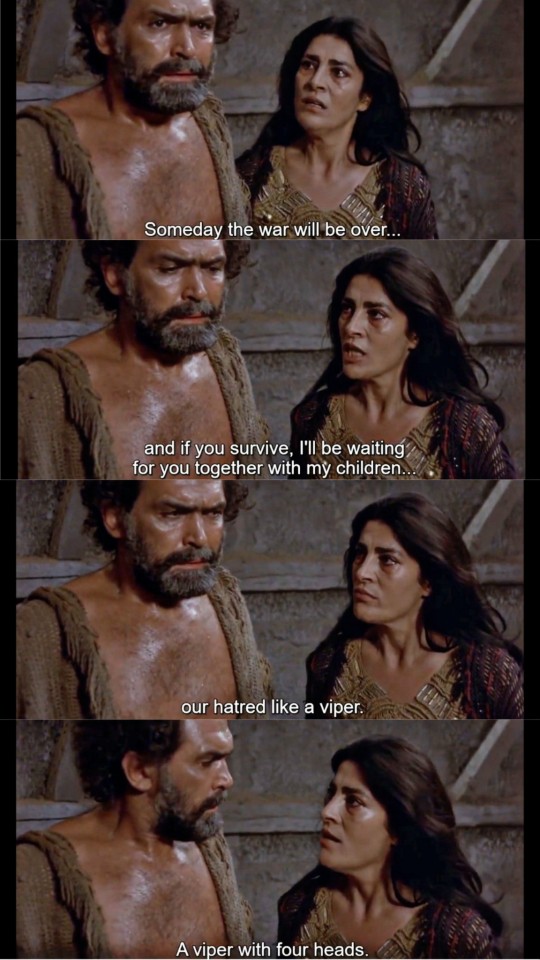

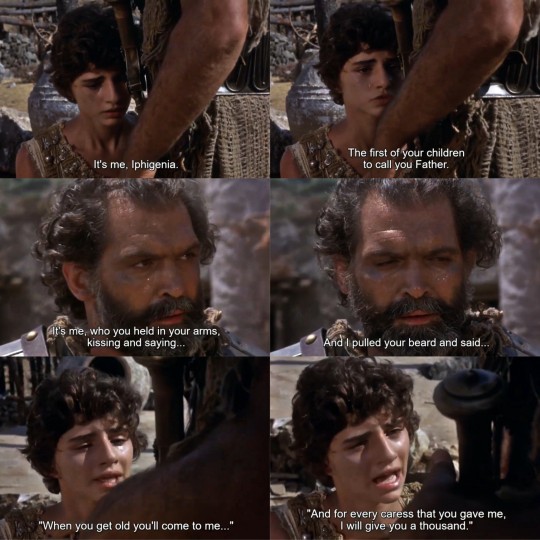

Film: Iphigenia

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

He’s so funny

Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound

#I hate when Hephaestus is characterized as a pushover#that man is sassy af#and willing to defend Hera#just bc he got cheated on doesn’t mean he’s a loser#even when he’s forced to chain Prometheus he complains#love that#greek mythology#ancient greek mythology#greek pantheon#ancient greek theater#Aeschylus#Prometheus#greek myths#Kratos#bia#hephaestus greek mythology#hephaestus god#hephastios#hephaestus

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

are there any epithets for Dionysos that revolve around his theater aspect?

Yes, though some of them overlap with musical aspects. This is the case for the epithet Melpomenos, for which Giorgio Ieranò says: “It is unclear whether the epithet Melpomenos refers specifically to Dionysus as the god of tragedy (Melpomenē was the Muse responsible for tragic poetry), or whether it generically indicates his connection with molpē, sung music, as Pausanias seems to suggest, establishing a comparison between Dionysus Melpomenos and Apollo Musegetes.”1

Something similar can also be said of epithets like Dionysus Aulonaeus (of the aulos) and Dionysus Dithyrambos, especially since the latter refers to a choral song that does have a place in ancient Greek theater and both these artforms present in theatrical festivals like the Dionysias.

These are the ones that come to mind as the most obvious, but there could be more that are less direct. I hesitated about including “Kathegemon” because it is historically linked to the theater, but more from context than literal meaning (it means “leader”), and the same would apply for an epithet like Eleuthereus, in the sense that it’s not literally linked to acting or theater as an art, but rather linked to it via the Athenian theater and City Dionysia as a state festival.

1- Giorgio Ieranò, Dionysus and the Ambiguity of Orgiastic Music in A Companion to Ancient Greek and Roman Music

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝕸𝖔𝖓𝖙𝖍 𝕺𝖋 𝕲𝖆𝖒𝖊𝖑𝖎𝖔𝖓

14𝖙𝖍 𝖉𝖆𝖞 𝖔𝖋 𝕲𝖆𝖒𝖊𝖑𝖎𝖔𝖓

Third day of Lenaia (most probable period).

Theatrical competitions.

From the 🌕(♌) : Beginning of the Sacred Truce for the Lesser Mysteries until the 10th day of Elaphebolion. (IG 12, 6, 76-87)

''The fourteenth day of each month is called ''the most sacred'' because (Hesiod) praises the fourteenth day both as the day of the opening jars as the best of all; in fact, the lunar light is rich...the moon reaches the middle of the total distance into wich accomplishes her journey...since in the middle, in relation to the circle, perfection is found...'' (Scholia Erga 819)

Source: Hellenismo

Img: Museo Archeologico Nationale. Ancient roman mosaic that depicts a young Bacchus. Napoli House of the Faun, Pompei

#today#gamelion#hellenic calendar us#hellenic calendar#dionysos#dionysus lenaia#dionysus#dionysos lenaia#god dionysos#ancient greek theater

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

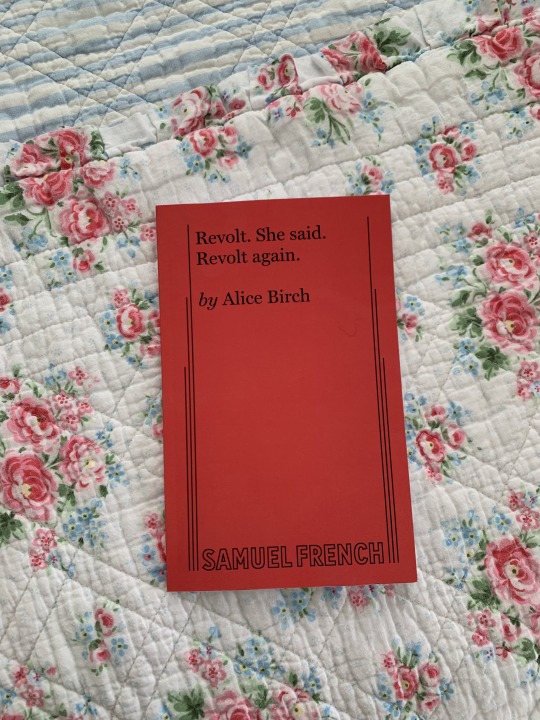

day 14/100 days of productivity

read ‚The Bacchae‘ by Euripides

read ‚Revolt. She said. Revolt again.‘ by Alice Birch

doing on-going house chores & gardening

ate some delicious pizza 🍕🌿🇫🇷

#100 days of productivity#study blog#studyblr#studygram#student life#student#books and reading#reading aesthetic#reading#studies#theatre studies#theatre#ancient greek theater#alice birch#euripedes#the bacchae#bacchanalian

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ancient Greek theater of Epidaurus, a work of the architect Polykleitos the Younger (late 4th century BCE).

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“There is no sickness worse for me than words that to be kind must lie.”

Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus (525-456 B.C.)

Art: Vladimir Gvozdariki

3 notes

·

View notes