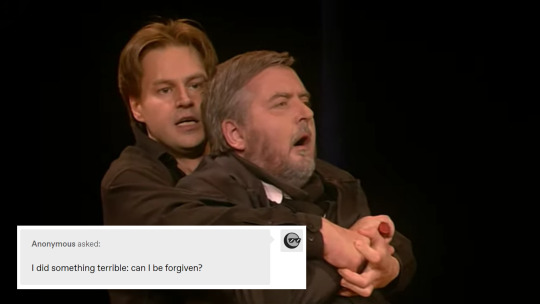

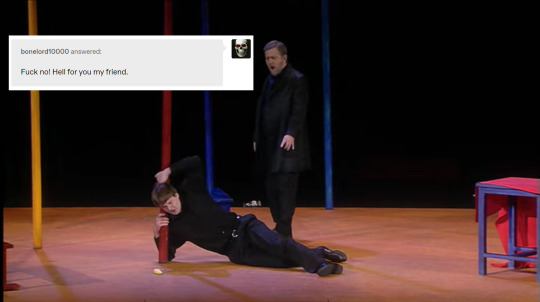

#and for my non opera mutuals: this is basically the entire show

Photo

hello opera mutuals.

#sasha makes#look it was only a matter of time before i made something stupid like this#don giovanni#il commendatore#text post meme#not the most dramatic staging of the finale to grab stills from but it'll do#and for my non opera mutuals: this is basically the entire show#actually i made an alternate version of this with a different production but i think this one will circulate better. know your audience etc#opera memes

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love Never Dies is not the fix-it fic I was expecting

Recently, I found out there was a sequel movie to that 2004 Phantom of the Opera movie with Gerard Butler in it. And since I’ve been on a Phantom kick... I watched it.

It's called Love Never Dies and it basically reads like someone's "fix-it fic" where Raoul turns out to be an abusive gambling drunk and Christine actually DID have sex with the Phantom once and WHOOPS the son Raoul thinks is his own is ACTUALLY the Phantom's son and in the end she fucking dies, so her dying wish is for Phantom to raise the boy.... and I guess kiss her corpse one last time because That Happened....

ALSO ABOUT 30 MINUTES INTO THE MOVIE PHANTOM AND CHRISTINE START SINGING ABOUT HAVING SEX, SO I JUST WANT YOU TO KNOW AND BE PREPARED FOR THAT BECAUSE IT IS BOTH HILARIOUS AND EXTREMELY AWKWARD.

Seriously, I had to keep pausing the movie to laugh because I swear they started having sex with their voices by the end of the duet. My major question after all that is... when did they actually HAVE time to do the devil's tango during the first movie? Like... at what point exactly did this take place? What did I miss? XD

Bearing all that in mind, I’m going to take anyone interested in this on a little adventure through the highlights of this movie. Because I already essentially live blogged this to several people as I was going through it and I feel like it’s worth sharing.

There is a plot twist at the end of this “fix-it” - trust me it’s worth it, please keep reading you’re in for a treat~

~.~

WELL ANYWAY THIS IS THE LOOK ON PHANTOM'S FACE WHEN HE REALIZES FOR THE FIRST TIME THAT CHRISTINE HAS A SON

This, mind you, is directly after the scene in which they've just sung a duet about how they bonked each other way back when.....

Like... they literally transition from "GRAPHIC VOICE FUCKING" to "Sing for me again, Christine! I'll pay you double what you were offered by that Hammerstein fellow!" to "OH HEY LOOK A CHILD!" asdhklf

That's not the face of a man who's like "OH SHIT I HAVE A SON"

That is the face of a man who's like "OH SHIT MY RIVAL GOT MY CRUSH PREGNANT, NOW I HAVE TO KILL THE BOY" because he hasn't fucking figured it out yet and I'm cackling this is awful.

Flash forward a few short scenes and

THIS!!! THIS IS THE FACE OF A MAN WHO JUST REALIZED "OH SHIT THIS IS MY SON!"

"this boy... this music... he plays... just like me" he figured it out... because... the kid plays piano.... I just

Breaking News: latent piano talent is hereditary

Amazing XD

Meanwhile, the kid’s just:

"uh, dude? you okay over there?"

Also, I feel like I have to mention that Phantom's hair is all sleek and black and full right up until he discovers he has a son, decides to test him to see if this boy could truly be his.... and then takes off his mask to the sound of his son SCREECHING BLOODY MURDER BECAUSE APPARENTLY ACTUAL DEFORMED HUMANS IN GLASS CAGES ARE BEAUTIFUL BUT A BUBBLE SUNBURN SCAR FACE IS THE MOST HIDEOUS THING THIS CHILD HAS EVER SEEN WITH HIS 10-YEAR-OLD EYES.... and that's evidently enough to make Phantom's hair go thin and grey and start falling out of his head because he looks like he's Been Through Some Shit right after that.

Poor dude can only take so much rejection, it seems. That child aged him by at least 50 years all in the span of a few minutes.

Meanwhile, I'm still vexxed by the fact that the Phantom in this movie is somehow still convinced his non-birth deformity couldn't possibly NOT be genetically passed on to his child.... because it's... you know... not a genetic deformity in the Phantom cinematic universe of these two movies unlike in the original source material...

His bubble sunburn scar face was obtained through abuse he received while being caged for a freak show since his childhood... so why is he somehow convinced that it's impossible for his offspring to be born without a deformity? I mean, I get what the movie is trying to go for with his initial denial that he could produce something so beautiful... considering he has internalized the idea that his outward appearance is ugly, he could never be beautiful, and it's the reason for his loneliness... but I'm just too distracted by this discrepancy.

I mean...

Movie Phantom: *is surprised non-genetic deformity isn't hereditary*

Also Movie Phantom: *thinks latent musical talent/interest is hereditary*

Aah, yes. It all makes sense now. Everything is genetic but actual genetics itself. How foolish of me. XD

~.~

And then the second half of this movie is really something.....

16 minutes in to the second act and Raoul has gambled his wife away because he was drunk and Phantom saw the perfect opportunity to swoop in and hit him in his "manly pride spot"

Phantom, out here in full fuckboy mode: "Alright, Raoul, let's settle this once and for all, you drunken bastard. How about we take a gamble?"

Raoul: "Dammit, you know I can't resist a gamble!"

Phantom: "If Christine does the singing gig she's being paid to do, it means she loves me and you have to disappear forever! But if she decides to drop her career for some reason, it means she loves you and I'll leave you alone."

Raoul: "Sounds perfectly reasonable to me! So, I'm going to charge right into her dressing room 10 minutes before she's due to sing and then beg her to drop her entire career for me without informing her of this stupid bet we've just made! That'll totally win her heart and not come back to bite me in a classic misunderstanding at all!"

Phantom: "Excellent, you stupid boy! You go do that!"

Phantom then proceeds to convince Christine that Raoul is a selfish bastard who wants to hold her back from reaching her potential like the shitty sexist husbands of the time.

Raoul:

~.~

Now it's the end of the movie, Christine is dead, their son is sadly laying in her lap.... and Raoul just arrived on the scene, so Phantom lifts his hand off the boy's head after trying to have A Moment and does THIS

I don't even know what this face is, but I fucking love it. Ben Lewis’ facial expressions make this whole movie, to be honest. XD

Phantom literally just.... doesn't know what to do with his hands. He just removes himself from the scene, hands Raoul back his dead wife like "okay, here's your family back, sorry I got involved" and then cries at the ocean for a while asdhklf

Then the son goes up to the Phantom, hugs him, takes his mask off and DOESN'T SCREAM IN TERROR THIS TIME.... because he finally accepted this man as his birth father and understands that beauty comes from within and all that jazz.

So, what I got out of this ending here..... is that Christine is dead...... and Raoul and Phantom are finally going to put aside their differences to raise their son (now that their mutual love interest is out of the picture). And now I'm kind of wondering if.... this "fix-it fic" actually had a different ship in mind the entire time and they just really needed to find a feasible way to get Phantom's DNA into the mix. XD

So, in conclusion, my only question is this: Where is the sequel to THIS movie, Andrew Lloyd Webber?! Where is my sequel where Raoul and Phantom have to share the domestic responsibilities of raising their son together???!!!?!? WHERE IS IT, YOU COWARD

GIVE ME MY SEQUEL WHERE THESE TWO AWFUL MEN HAVE TO REFORM THEMSELVES AND EACH OTHER FOR THE SAKE OF THEIR CHILD AND A HEALTHIER LIFESTYLE!

YOU BUTCHERED THEM, SO NOW YOU HAVE TO FIX THEM!

THINK OF THE CHILDREN!

#Phantom of the Opera#Love Never Dies#random thought#if Tumblr flags this because of my swearing I really really hope someone has to sit down and read this post with their own human eyes#validate my suffering please XD#the character assassinations in this sequel were horrible they all deserved so much better than this

1 note

·

View note

Text

How @supports Works

CSS has a neat feature that allows us to test if the browser supports a particular property or property:value combination before applying a block of styles — like how a @media query matches when, say, the width of the browser window is narrower than some specified size and then the CSS within it takes effect. In the same spirit, the CSS inside this feature will take effect when the property:value pair being tested is supported in the current browser. That feature is called @supports and it looks like this:

@supports (display: grid) { .main { display: grid; } }

Why? Well, that's a bit tricky. Personally, I find don't need it all that regularly. CSS has natural fallback mechanisms such that if the browser doesn't understand a property:value combination, then it will ignore it and use something declared before it if there is anything, thanks to the cascade. Sometimes that can be used to deal with fallbacks and the end result is a bit less verbose. I'm certainly not a it's-gotta-be-the-same-in-every-browser kinda guy, but I'm also not a write-elaborate-fallbacks-to-get-close kinda guy either. I generally prefer a situation where a natural failure of a property:value doesn't do anything drastic to destroy functionality.

That said, @supports certainly has use cases! And as I found out while putting this post together, plenty of people use it for plenty of interesting situations.

A classic use case

The example I used in the intro is a classic one that you'll see used in lots of writing about this topic. Here it is a bit more fleshed out:

/* We're gonna write a fallback up here in a minute */ @supports (display: grid) { .photo-layout { display: grid; grid-template-columns: repeat(auto-fill, minmax(200px, 1fr)); grid-gap: 2rem; } }

Nice grid! Repeating and auto-filling columns is a sweet feature of CSS grid. But, of course, there are browsers that don't support grid, or don't support all the specific features of it that I'm using above there.

For example, iOS shipped support for CSS grid in version 10.2, but iOS has had flexbox support since version 7. That's a decent gap of people with older iOS devices that do support flexbox but not grid. I'm sure there are more example gaps like that, but you probably get the idea.

I was running on an older version of mobile safari and many many many many many sites were flat out broken that used grid

I’m waiting another year or so before messing about with it

— David Wells (@DavidWells) February 6, 2019

It may be acceptable to let the fallback for this be nothing, depending on the requirements. For example, vertically stacked block-level elements rather than a multi-column grid layout. That's often fine with me. But let's say it's not fine, like a photo gallery or something that absolutely needs to have some basic grid-like structure. In that case, starting with flexbox as the default and using @supports to apply grid features where they're supported may work better...

.photo-layout { display: flex; flex-wrap: wrap; > div { flex: 200px; margin: 1rem; } } @supports (display: grid) { .photo-layout { display: grid; grid-template-columns: repeat(auto-fill, minmax(200px, 1fr)); grid-gap: 2rem; > div { margin: 0; } } }

The "fallback" is the code outside of the @supports block (the properties above the block in the example above), and the grid code is either inside or after. The @supports block doesn't change any specificity, so we need the source order to help make sure the overrides work.

Notice I had to reset the margin on the divs inside the @supports block. That's the kind of thing I find a bit annoying. There is just enough crossover between the two scenarios that it requires being super aware of how they impact each other.

Doesn't that make you wish it could be entirely logically separated...

There is "not" logic in @supports blocks, but that doesn't mean it should always be used

Jen Simmons put this example in an article called Using Feature Queries in CSS a few years ago:

/* Considered a BAD PRACTICE, at least if you're supporting IE 11 and iOS 8 and older */ @supports not (display: grid) { /* Isolated code for non-support of grid */ } @supports (display: grid) { /* Isolated code for support of grid */ }

Notice the not operator in the first block. That's checking for browsers that do not support grid in order to apply certain styles to those browsers. The reason this approach is considered bad practice is that the browser support for @supports itself has to be considered!. That's what makes this so dang tricky.

It's very appealing to write code in logically separated @supports blocks like that because then it's starting from scratch each time and doesn't need to be overriding previous values and dealing with those logical mind-benders. But let's go back to the same iOS situation we considered before... @supports shipped in iOS in version 9 (right between when flexbox shipped in iOS 7 and grid shipped in iOS 10.2). That means any flexbox fallback code in a @supports block using the not operator to check for (display: grid) {} support wouldn't work in either iOS 7 or 8, meaning the fallback now needs a fallback from working in browsers it otherwise would have. Phew!

The big reason to reach for @supports is to account for very different implementations of something depending on feature support where it becomes easier to reason and distinguish between those implementations if the blocks of code are separated.

We'll probably get to a point where we can use mutually-exclusive blocks like that without worry. Speaking of which...

@supports is likely to be more useful over time.

Once @supports is supported in all browsers you need to support, then it's good to start using it more aggressively and without having to factor in the complication of considering whether @supports itself is supported. Here's the support grid on that:

This browser support data is from Caniuse, which has more detail. A number indicates that browser supports the feature at that version and up.

Desktop

ChromeOperaFirefoxIEEdgeSafari2812.122No129

Mobile / Tablet

iOS SafariOpera MobileOpera MiniAndroidAndroid ChromeAndroid Firefox9.0-9.246all4.47164

Basically, IE 11 and any iOS device stuck on iOS 8 are the pain points. If your requirements are already past those, then you're good to use @supports more freely.

The irony is that there hasn't been a ton of CSS features shipping that have big clear @supports use cases — but there are some! Apparently, it's possible to test new fancy stuff like Houdini:

Using it on my wedding website to check for Houdini support 🎩🐰

— Sam Richard (@Snugug) February 6, 2019

(I'm not sure entirely what you'd put in the @supports block to do that. Has anyone else done this?)

When @supports isn't doing anything useful

I've seen a good amount of @supports uses in the wild where the end result is exactly as it would be without using it. For example...

@supports (transform: rotate(5deg)) { .avatar { transform: rotate(5deg); } }

On some level, that makes perfect logical sense. If transforms are supported, use them. But it's unnecessary if nothing different is happening in a non-support scenario. In this case, the transform can fail without the @supports block and the result is the same.

Here's another example of that shaking out.

There are browser extensions for playing with @supports

There are two of them!

Feature Queries Manager by Ire Aderinokun

CSS Feature Toggle Extension by Keith Clark

They are both centered around the idea that we can write @supports blocks in CSS and then toggle them on and off as if we're looking at a rendering of the code in a browser that does or doesn't support that feature.

Here's a video of Keith's tool applied to the scenario using grid with a flexbox fallback:

This is fun to play with and is very neat tech. But in this exact scenario, if I was able to pull off the layout identically with flexbox, then I'd probably just do that and save that little bit of technical debt.

Ire's tool, which she wrote about in the article Creating The Feature Queries Manager DevTools Extension, has a slightly different approach in that it shows the feature queries that you actually wrote in your CSS and provides toggles to flip them on and off. I don't think it works through iframes though, so I popped open Debug Mode to use it on CodePen.

More real world use cases for @supports

Here's one from Erik Vorhes. He's styling some custom checkboxes and radio buttons here, but wraps all of it in a @supports block. None of the styling gets applied unless the block passes the support check.

@supports (transform: rotate(1turn)) and (opacity: 0) { /* all the styling for Erik's custom checkboxes and radio buttons */ }

Here are several more I've come across:

Joe Wright and Tiago Nunes mentioned using it for position: sticky;. I'd love to see a demo here! As in, where you go for position: sticky;, but then have to do something different besides let it fail for a non-supporting browser.

Keith Grant and Matthias Ott mention using it for object-fit: contain;. Matthias has a demo where positioning trickery is used to make an image sort of fill a container, which is then made easier and better through that property when it's available.

Ryan Filler mentions using it for mix-blend-mode. His example sets more opacity on an element, but if mix-blend-mode is supported, it uses a bit less and that property which can have the effect of seeing through an element on its own.

.thing { opacity: 0.5; } @supports (mix-blend-mode: multiply) { .thing { mix-blend-mode: multiply; opacity: 0.75; } }

Rik Schennink mentioned the backdrop-filter property. He says, "when it's supported the opacity of the background color often needs some fine tuning."

Nour Saud mentioned it can be used to detect Edge through a specific vendor-prefixed property: @supports (-ms-ime-align:auto) { }.

Amber Weinberg mentioned using it for clip-path because adjusting the sizing or padding of an element will accommodate when clipping is unavailable.

Ralph Holzmann mentioned using it to test for that "notch" stuff (environment variables).

Stacy Kvernmo mentioned using it for the variety of properties needed for drop capping characters. Jen Simmons mentions this use case in her article as well. There is an initial-letter CSS property that's pretty fantastic for drop caps, but is used in conjunction with other properties that you may not want to apply at all if initial-letter isn't supported (or if there's a totally different fallback scenario).

Here's a bonus one from Nick Colley that's not @supports, but @media instead! The spirit is the same. It can prevent that "stuck" hover state on touch devices like this:

@media (hover: hover) { a:hover { background: yellow; } }

Logic in @supports

Basic:

@supports (initial-letter: 4) { }

Not:

@supports not (initial-letter: 4) { }

And:

@supports (initial-letter: 4) and (transform: scale(2)) { }

Or:

@supports (initial-letter: 4) or (-webkit-initial-letter: 4) { }

Combos:

@supports ((display: -webkit-flex) or (display: -moz-flex) or (display: flex)) and (-webkit-appearance: caret) { }

JavaScript Variant

JavaScript has an API for this. To test if it exists...

if (window.CSS && window.CSS.supports) { // Apparently old Opera had a weird implementation, so you could also do: // !!((window.CSS && window.CSS.supports) || window.supportsCSS || false) }

To use it, either pass the property to it in one param and the value in another:

const supportsGrid = CSS.supports("display", "grid");

...or give it all in one string mirroring the CSS syntax:

const supportsGrid = CSS.supports("(display: grid)");

Selector testing

At the time of this writing, only Firefox supports this sort of testing (behind an experimental flag), but there is a way to test the support of selectors with @supports. MDN's demo:

@supports selector(A > B) { }

You?

Of course, we'd love to see Pens of @supports use cases in the comments. So share 'em!

The post How @supports Works appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

How @supports Works published first on https://deskbysnafu.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

How @supports Works

CSS has a neat feature that allows us to test if the browser supports a particular property or property:value combination before applying a block of styles — like how a @media query matches when, say, the width of the browser window is narrower than some specified size and then the CSS within it takes effect. In the same spirit, the CSS inside this feature will take effect when the property:value pair being tested is supported in the current browser. That feature is called @supports and it looks like this:

@supports (display: grid) { .main { display: grid; } }

Why? Well, that's a bit tricky. Personally, I find don't need it all that regularly. CSS has natural fallback mechanisms such that if the browser doesn't understand a property:value combination, then it will ignore it and use something declared before it if there is anything, thanks to the cascade. Sometimes that can be used to deal with fallbacks and the end result is a bit less verbose. I'm certainly not a it's-gotta-be-the-same-in-every-browser kinda guy, but I'm also not a write-elaborate-fallbacks-to-get-close kinda guy either. I generally prefer a situation where a natural failure of a property:value doesn't do anything drastic to destroy functionality.

That said, @supports certainly has use cases! And as I found out while putting this post together, plenty of people use it for plenty of interesting situations.

A classic use case

The example I used in the intro is a classic one that you'll see used in lots of writing about this topic. Here it is a bit more fleshed out:

/* We're gonna write a fallback up here in a minute */ @supports (display: grid) { .photo-layout { display: grid; grid-template-columns: repeat(auto-fill, minmax(200px, 1fr)); grid-gap: 2rem; } }

Nice grid! Repeating and auto-filling columns is a sweet feature of CSS grid. But, of course, there are browsers that don't support grid, or don't support all the specific features of it that I'm using above there.

For example, iOS shipped support for CSS grid in version 10.2, but iOS has had flexbox support since version 7. That's a decent gap of people with older iOS devices that do support flexbox but not grid. I'm sure there are more example gaps like that, but you probably get the idea.

I was running on an older version of mobile safari and many many many many many sites were flat out broken that used grid

I’m waiting another year or so before messing about with it

— David Wells (@DavidWells) February 6, 2019

It may be acceptable to let the fallback for this be nothing, depending on the requirements. For example, vertically stacked block-level elements rather than a multi-column grid layout. That's often fine with me. But let's say it's not fine, like a photo gallery or something that absolutely needs to have some basic grid-like structure. In that case, starting with flexbox as the default and using @supports to apply grid features where they're supported may work better...

.photo-layout { display: flex; flex-wrap: wrap; > div { flex: 200px; margin: 1rem; } } @supports (display: grid) { .photo-layout { display: grid; grid-template-columns: repeat(auto-fill, minmax(200px, 1fr)); grid-gap: 2rem; > div { margin: 0; } } }

The "fallback" is the code outside of the @supports block (the properties above the block in the example above), and the grid code is either inside or after. The @supports block doesn't change any specificity, so we need the source order to help make sure the overrides work.

Notice I had to reset the margin on the divs inside the @supports block. That's the kind of thing I find a bit annoying. There is just enough crossover between the two scenarios that it requires being super aware of how they impact each other.

Doesn't that make you wish it could be entirely logically separated...

There is "not" logic in @supports blocks, but that doesn't mean it should always be used

Jen Simmons put this example in an article called Using Feature Queries in CSS a few years ago:

/* Considered a BAD PRACTICE, at least if you're supporting IE 11 and iOS 8 and older */ @supports not (display: grid) { /* Isolated code for non-support of grid */ } @supports (display: grid) { /* Isolated code for support of grid */ }

Notice the not operator in the first block. That's checking for browsers that do not support grid in order to apply certain styles to those browsers. The reason this approach is considered bad practice is that the browser support for @supports itself has to be considered!. That's what makes this so dang tricky.

It's very appealing to write code in logically separated @supports blocks like that because then it's starting from scratch each time and doesn't need to be overriding previous values and dealing with those logical mind-benders. But let's go back to the same iOS situation we considered before... @supports shipped in iOS in version 9 (right between when flexbox shipped in iOS 7 and grid shipped in iOS 10.2). That means any flexbox fallback code in a @supports block using the not operator to check for (display: grid) {} support wouldn't work in either iOS 7 or 8, meaning the fallback now needs a fallback from working in browsers it otherwise would have. Phew!

The big reason to reach for @supports is to account for very different implementations of something depending on feature support where it becomes easier to reason and distinguish between those implementations if the blocks of code are separated.

We'll probably get to a point where we can use mutually-exclusive blocks like that without worry. Speaking of which...

@supports is likely to be more useful over time.

Once @supports is supported in all browsers you need to support, then it's good to start using it more aggressively and without having to factor in the complication of considering whether @supports itself is supported. Here's the support grid on that:

This browser support data is from Caniuse, which has more detail. A number indicates that browser supports the feature at that version and up.

Desktop

ChromeOperaFirefoxIEEdgeSafari2812.122No129

Mobile / Tablet

iOS SafariOpera MobileOpera MiniAndroidAndroid ChromeAndroid Firefox9.0-9.246all4.47164

Basically, IE 11 and any iOS device stuck on iOS 8 are the pain points. If your requirements are already past those, then you're good to use @supports more freely.

The irony is that there hasn't been a ton of CSS features shipping that have big clear @supports use cases — but there are some! Apparently, it's possible to test new fancy stuff like Houdini:

Using it on my wedding website to check for Houdini support 🎩🐰

— Sam Richard (@Snugug) February 6, 2019

(I'm not sure entirely what you'd put in the @supports block to do that. Has anyone else done this?)

When @supports isn't doing anything useful

I've seen a good amount of @supports uses in the wild where the end result is exactly as it would be without using it. For example...

@supports (transform: rotate(5deg)) { .avatar { transform: rotate(5deg); } }

On some level, that makes perfect logical sense. If transforms are supported, use them. But it's unnecessary if nothing different is happening in a non-support scenario. In this case, the transform can fail without the @supports block and the result is the same.

Here's another example of that shaking out.

There are browser extensions for playing with @supports

There are two of them!

Feature Queries Manager by Ire Aderinokun

CSS Feature Toggle Extension by Keith Clark

They are both centered around the idea that we can write @supports blocks in CSS and then toggle them on and off as if we're looking at a rendering of the code in a browser that does or doesn't support that feature.

Here's a video of Keith's tool applied to the scenario using grid with a flexbox fallback:

This is fun to play with and is very neat tech. But in this exact scenario, if I was able to pull off the layout identically with flexbox, then I'd probably just do that and save that little bit of technical debt.

Ire's tool, which she wrote about in the article Creating The Feature Queries Manager DevTools Extension, has a slightly different approach in that it shows the feature queries that you actually wrote in your CSS and provides toggles to flip them on and off. I don't think it works through iframes though, so I popped open Debug Mode to use it on CodePen.

More real world use cases for @supports

Here's one from Erik Vorhes. He's styling some custom checkboxes and radio buttons here, but wraps all of it in a @supports block. None of the styling gets applied unless the block passes the support check.

@supports (transform: rotate(1turn)) and (opacity: 0) { /* all the styling for Erik's custom checkboxes and radio buttons */ }

Here are several more I've come across:

Joe Wright and Tiago Nunes mentioned using it for position: sticky;. I'd love to see a demo here! As in, where you go for position: sticky;, but then have to do something different besides let it fail for a non-supporting browser.

Keith Grant and Matthias Ott mention using it for object-fit: contain;. Matthias has a demo where positioning trickery is used to make an image sort of fill a container, which is then made easier and better through that property when it's available.

Ryan Filler mentions using it for mix-blend-mode. His example sets more opacity on an element, but if mix-blend-mode is supported, it uses a bit less and that property which can have the effect of seeing through an element on its own.

.thing { opacity: 0.5; } @supports (mix-blend-mode: multiply) { .thing { mix-blend-mode: multiply; opacity: 0.75; } }

Rik Schennink mentioned the backdrop-filter property. He says, "when it's supported the opacity of the background color often needs some fine tuning."

Nour Saud mentioned it can be used to detect Edge through a specific vendor-prefixed property: @supports (-ms-ime-align:auto) { }.

Amber Weinberg mentioned using it for clip-path because adjusting the sizing or padding of an element will accommodate when clipping is unavailable.

Ralph Holzmann mentioned using it to test for that "notch" stuff (environment variables).

Stacy Kvernmo mentioned using it for the variety of properties needed for drop capping characters. Jen Simmons mentions this use case in her article as well. There is an initial-letter CSS property that's pretty fantastic for drop caps, but is used in conjunction with other properties that you may not want to apply at all if initial-letter isn't supported (or if there's a totally different fallback scenario).

Here's a bonus one from Nick Colley that's not @supports, but @media instead! The spirit is the same. It can prevent that "stuck" hover state on touch devices like this:

@media (hover: hover) { a:hover { background: yellow; } }

Logic in @supports

Basic:

@supports (initial-letter: 4) { }

Not:

@supports not (initial-letter: 4) { }

And:

@supports (initial-letter: 4) and (transform: scale(2)) { }

Or:

@supports (initial-letter: 4) or (-webkit-initial-letter: 4) { }

Combos:

@supports ((display: -webkit-flex) or (display: -moz-flex) or (display: flex)) and (-webkit-appearance: caret) { }

JavaScript Variant

JavaScript has an API for this. To test if it exists...

if (window.CSS && window.CSS.supports) { // Apparently old Opera had a weird implementation, so you could also do: // !!((window.CSS && window.CSS.supports) || window.supportsCSS || false) }

To use it, either pass the property to it in one param and the value in another:

const supportsGrid = CSS.supports("display", "grid");

...or give it all in one string mirroring the CSS syntax:

const supportsGrid = CSS.supports("(display: grid)");

Selector testing

At the time of this writing, only Firefox supports this sort of testing (behind an experimental flag), but there is a way to test the support of selectors with @supports. MDN's demo:

@supports selector(A > B) { }

You?

Of course, we'd love to see Pens of @supports use cases in the comments. So share 'em!

The post How @supports Works appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

😉SiliconWebX | 🌐CSS-Tricks

0 notes

Text

How @supports Works

CSS has a neat feature that allows us to test if the browser supports a particular property or property:value combination before applying a block of styles — like how a @media query matches when, say, the width of the browser window is narrower than some specified size and then the CSS within it takes effect. In the same spirit, the CSS inside this feature will take effect when the property:value pair being tested is supported in the current browser. That feature is called @supports and it looks like this:

@supports (display: grid) { .main { display: grid; } }

Why? Well, that's a bit tricky. Personally, I find don't need it all that regularly. CSS has natural fallback mechanisms such that if the browser doesn't understand a property:value combination, then it will ignore it and use something declared before it if there is anything, thanks to the cascade. Sometimes that can be used to deal with fallbacks and the end result is a bit less verbose. I'm certainly not a it's-gotta-be-the-same-in-every-browser kinda guy, but I'm also not a write-elaborate-fallbacks-to-get-close kinda guy either. I generally prefer a situation where a natural failure of a property:value doesn't do anything drastic to destroy functionality.

That said, @supports certainly has use cases! And as I found out while putting this post together, plenty of people use it for plenty of interesting situations.

A classic use case

The example I used in the intro is a classic one that you'll see used in lots of writing about this topic. Here it is a bit more fleshed out:

/* We're gonna write a fallback up here in a minute */ @supports (display: grid) { .photo-layout { display: grid; grid-template-columns: repeat(auto-fill, minmax(200px, 1fr)); grid-gap: 2rem; } }

Nice grid! Repeating and auto-filling columns is a sweet feature of CSS grid. But, of course, there are browsers that don't support grid, or don't support all the specific features of it that I'm using above there.

For example, iOS shipped support for CSS grid in version 10.2, but iOS has had flexbox support since version 7. That's a decent gap of people with older iOS devices that do support flexbox but not grid. I'm sure there are more example gaps like that, but you probably get the idea.

I was running on an older version of mobile safari and many many many many many sites were flat out broken that used grid

I’m waiting another year or so before messing about with it

— David Wells (@DavidWells) February 6, 2019

It may be acceptable to let the fallback for this be nothing, depending on the requirements. For example, vertically stacked block-level elements rather than a multi-column grid layout. That's often fine with me. But let's say it's not fine, like a photo gallery or something that absolutely needs to have some basic grid-like structure. In that case, starting with flexbox as the default and using @supports to apply grid features where they're supported may work better...

.photo-layout { display: flex; flex-wrap: wrap; > div { flex: 200px; margin: 1rem; } } @supports (display: grid) { .photo-layout { display: grid; grid-template-columns: repeat(auto-fill, minmax(200px, 1fr)); grid-gap: 2rem; > div { margin: 0; } } }

The "fallback" is the code outside of the @supports block (the properties above the block in the example above), and the grid code is either inside or after. The @supports block doesn't change any specificity, so we need the source order to help make sure the overrides work.

Notice I had to reset the margin on the divs inside the @supports block. That's the kind of thing I find a bit annoying. There is just enough crossover between the two scenarios that it requires being super aware of how they impact each other.

Doesn't that make you wish it could be entirely logically separated...

There is "not" logic in @supports blocks, but that doesn't mean it should always be used

Jen Simmons put this example in an article called Using Feature Queries in CSS a few years ago:

/* Considered a BAD PRACTICE, at least if you're supporting IE 11 and iOS 8 and older */ @supports not (display: grid) { /* Isolated code for non-support of grid */ } @supports (display: grid) { /* Isolated code for support of grid */ }

Notice the not operator in the first block. That's checking for browsers that do not support grid in order to apply certain styles to those browsers. The reason this approach is considered bad practice is that the browser support for @supports itself has to be considered!. That's what makes this so dang tricky.

It's very appealing to write code in logically separated @supports blocks like that because then it's starting from scratch each time and doesn't need to be overriding previous values and dealing with those logical mind-benders. But let's go back to the same iOS situation we considered before... @supports shipped in iOS in version 9 (right between when flexbox shipped in iOS 7 and grid shipped in iOS 10.2). That means any flexbox fallback code in a @supports block using the not operator to check for (display: grid) {} support wouldn't work in either iOS 7 or 8, meaning the fallback now needs a fallback from working in browsers it otherwise would have. Phew!

The big reason to reach for @supports is to account for very different implementations of something depending on feature support where it becomes easier to reason and distinguish between those implementations if the blocks of code are separated.

We'll probably get to a point where we can use mutually-exclusive blocks like that without worry. Speaking of which...

@supports is likely to be more useful over time.

Once @supports is supported in all browsers you need to support, then it's good to start using it more aggressively and without having to factor in the complication of considering whether @supports itself is supported. Here's the support grid on that:

This browser support data is from Caniuse, which has more detail. A number indicates that browser supports the feature at that version and up.

Desktop

ChromeOperaFirefoxIEEdgeSafari2812.122No129

Mobile / Tablet

iOS SafariOpera MobileOpera MiniAndroidAndroid ChromeAndroid Firefox9.0-9.246all4.47164

Basically, IE 11 and any iOS device stuck on iOS 8 are the pain points. If your requirements are already past those, then you're good to use @supports more freely.

The irony is that there hasn't been a ton of CSS features shipping that have big clear @supports use cases — but there are some! Apparently, it's possible to test new fancy stuff like Houdini:

Using it on my wedding website to check for Houdini support 🎩🐰

— Sam Richard (@Snugug) February 6, 2019

(I'm not sure entirely what you'd put in the @supports block to do that. Has anyone else done this?)

When @supports isn't doing anything useful

I've seen a good amount of @supports uses in the wild where the end result is exactly as it would be without using it. For example...

@supports (transform: rotate(5deg)) { .avatar { transform: rotate(5deg); } }

On some level, that makes perfect logical sense. If transforms are supported, use them. But it's unnecessary if nothing different is happening in a non-support scenario. In this case, the transform can fail without the @supports block and the result is the same.

Here's another example of that shaking out.

There are browser extensions for playing with @supports

There are two of them!

Feature Queries Manager by Ire Aderinokun

CSS Feature Toggle Extension by Keith Clark

They are both centered around the idea that we can write @supports blocks in CSS and then toggle them on and off as if we're looking at a rendering of the code in a browser that does or doesn't support that feature.

Here's a video of Keith's tool applied to the scenario using grid with a flexbox fallback:

This is fun to play with and is very neat tech. But in this exact scenario, if I was able to pull off the layout identically with flexbox, then I'd probably just do that and save that little bit of technical debt.

Ire's tool, which she wrote about in the article Creating The Feature Queries Manager DevTools Extension, has a slightly different approach in that it shows the feature queries that you actually wrote in your CSS and provides toggles to flip them on and off. I don't think it works through iframes though, so I popped open Debug Mode to use it on CodePen.

More real world use cases for @supports

Here's one from Erik Vorhes. He's styling some custom checkboxes and radio buttons here, but wraps all of it in a @supports block. None of the styling gets applied unless the block passes the support check.

@supports (transform: rotate(1turn)) and (opacity: 0) { /* all the styling for Erik's custom checkboxes and radio buttons */ }

Here are several more I've come across:

Joe Wright and Tiago Nunes mentioned using it for position: sticky;. I'd love to see a demo here! As in, where you go for position: sticky;, but then have to do something different besides let it fail for a non-supporting browser.

Keith Grant and Matthias Ott mention using it for object-fit: contain;. Matthias has a demo where positioning trickery is used to make an image sort of fill a container, which is then made easier and better through that property when it's available.

Ryan Filler mentions using it for mix-blend-mode. His example sets more opacity on an element, but if mix-blend-mode is supported, it uses a bit less and that property which can have the effect of seeing through an element on its own.

.thing { opacity: 0.5; } @supports (mix-blend-mode: multiply) { .thing { mix-blend-mode: multiply; opacity: 0.75; } }

Rik Schennink mentioned the backdrop-filter property. He says, "when it's supported the opacity of the background color often needs some fine tuning."

Nour Saud mentioned it can be used to detect Edge through a specific vendor-prefixed property: @supports (-ms-ime-align:auto) { }.

Amber Weinberg mentioned using it for clip-path because adjusting the sizing or padding of an element will accommodate when clipping is unavailable.

Ralph Holzmann mentioned using it to test for that "notch" stuff (environment variables).

Stacy Kvernmo mentioned using it for the variety of properties needed for drop capping characters. Jen Simmons mentions this use case in her article as well. There is an initial-letter CSS property that's pretty fantastic for drop caps, but is used in conjunction with other properties that you may not want to apply at all if initial-letter isn't supported (or if there's a totally different fallback scenario).

Here's a bonus one from Nick Colley that's not @supports, but @media instead! The spirit is the same. It can prevent that "stuck" hover state on touch devices like this:

@media (hover: hover) { a:hover { background: yellow; } }

Logic in @supports

Basic:

@supports (initial-letter: 4) { }

Not:

@supports not (initial-letter: 4) { }

And:

@supports (initial-letter: 4) and (transform: scale(2)) { }

Or:

@supports (initial-letter: 4) or (-webkit-initial-letter: 4) { }

Combos:

@supports ((display: -webkit-flex) or (display: -moz-flex) or (display: flex)) and (-webkit-appearance: caret) { }

JavaScript Variant

JavaScript has an API for this. To test if it exists...

if (window.CSS && window.CSS.supports) { // Apparently old Opera had a weird implementation, so you could also do: // !!((window.CSS && window.CSS.supports) || window.supportsCSS || false) }

To use it, either pass the property to it in one param and the value in another:

const supportsGrid = CSS.supports("display", "grid");

...or give it all in one string mirroring the CSS syntax:

const supportsGrid = CSS.supports("(display: grid)");

Selector testing

At the time of this writing, only Firefox supports this sort of testing (behind an experimental flag), but there is a way to test the support of selectors with @supports. MDN's demo:

@supports selector(A > B) { }

You?

Of course, we'd love to see Pens of @supports use cases in the comments. So share 'em!

The post How @supports Works appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

How @supports Works published first on https://deskbysnafu.tumblr.com/

0 notes