#and i think such a complex world will be offputting to readers

Note

Hi Pia.

I'm curious; do you think Mallory and Mount is going to be as 'epic' or as complex as Fae tales Verse?

And do you mind sharing some of it's worldbuilding with us?

Hi anon!

Mallory & Mount will have more complex building than the Fae Tales Verse, because it's not set on earth at all. It has different names for the days of the week, the months of the year, and its currency system is different, for a start. It has different festivals per different culture. It has new species of dog, and tree, and bird, for example (though some are recognisably based on dogs and trees and birds we have here).

It won't be as epic in some ways however because the characters aren't fae, so their stories can't stretch across decades in the same way. They can't heal from the same bombastic ridiculous injuries. They can't go and literally die and then literally come back from the dead because a Mage sacrificed some of her lifespan to save someone. In fact many of the characters have chronic illnesses and disabilities.

And it won't be as long, I don't think. The length of Fae Tales is now daunting to many new readers. So I don't really want to write a series that long again.

It will definitely be epic in other ways though! There are definitely life and death stakes, a lot of dangers, and big potentially morality destroying decisions on the line.

There's a metric fuckton of worldbuilding that has gone into the Mallory & Mount world, enough that I have a 150+ page private Wiki about it complete with hyperlinks. I'm going to share one file lol:

Blaubaas: Horse

A heavy drafthorse originating in Skemmerlicht and also found in Donwall, who often trade blaubass for the Whytefern draft. Blaubass means 'blue boss.'

They are blue-to-black drafthorses with a heavy winter coat, suited for mountaineering, difficult journeys and sled-pulling. They are slow but determined and weather dock-work well, and do not stain as badly as the Whytefern draft. Frugal and economical on food, and survives well on horsebread.

Function: Crate and stock pulling, carriages, heavy transport, mountain passes, cold weather journeys.

-

I know it's not that interesting, anon, but I really don't want to reveal any spoilers yet, and I'm worried I will. You can always check out the mandm tag for more about the world itself.

#asks and answers#mandm#mallory and mount#mallory & mount#tbh it's very intimidating worldbuilding#and i think such a complex world will be offputting to readers#so i'm now starting to think it'll be a bad idea in its current form#to launch#and i've been thinking about putting the characters in another world first lmao#to drive up some interest#but who knows

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

I think you have best theories in the fandom about shanks. It’s like you see more than most of us. So that’s why to just have simple yes or no answer would be enough. I have this level of trust in you.

Do you believe makinos child is shanks or someone’s else?

I just can’t stop thinking about this, because for me I don’t see it, but it’s so popular I feel stupid or blinded by my other ships.

thank you for your kind words!! you probably shouldn't place this must trust in me though, LOL. i'm just reading and overthinking everything in the source material, like everyone else is.

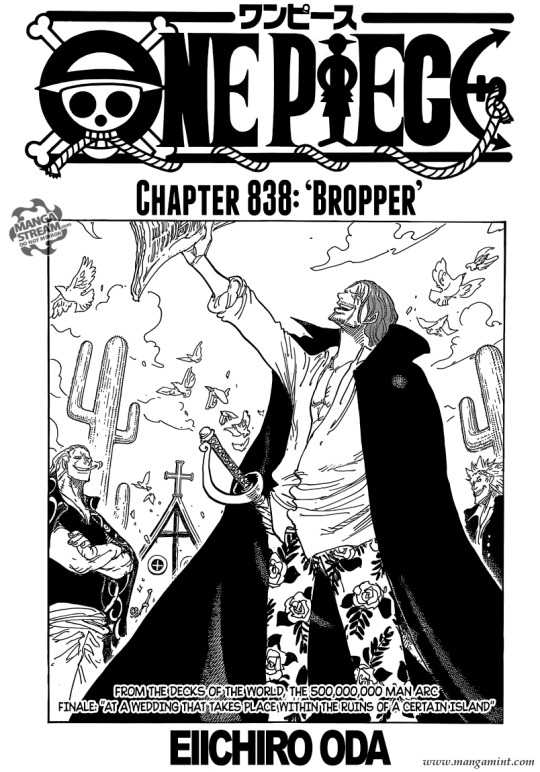

is it possible that shanks has a child with makino? well.. yeah. to put it bluntly, the simplest answer is usually the right answer with oda. he's already established that makino and shanks are friendly from chapter one, and shanks is even seen dressed up for a wedding on one cover page, which oda sometimes uses to tell canon events that don't fit the flow of the current arc. (think of enel's journey to the moon, for example).

me personally, though? i've got beef with this idea, and not for the reasons you might think. makino and shanks as a couple is fine to me; i don't find their relationship all that compelling, truthfully, but they fit the mold for most of oda's canon pairings.

when it comes to shanks' characterization, though, the idea of him having a child at this point in the story strikes me as both offputting and irrelevant. shanks is an emperor, and given his actions, his current responsibilities are clearly the priority. so the thought of shanks leaving makino alone to take care of their child is... strange? his status has the potential to endanger them. he is surely too preoccupied to be sailing back and forth to see them.

you could argue that this parallels roger and rouge, but i also think that's the worst possible way oda could have shanks mirror his old captain. at least in roger's case, oda had ace become a relevant part of luffy's story. what narrative purpose does this serve? is it to humanize shanks? i'm not quite sure what oda's angle is, here.

we also have to consider shanks' past. shanks left uta behind, so i don't think he is "above" leaving his newborn child, so to speak, but his reasoning in that situation was far more complex. here, though? this would be shanks ACTIVELY choosing to bring a child into this world, knowing full well he cannot take care of it until he sees his goals through. (SHANKS? patient, protective shanks, unable to wait to start a family? the boy who was an abandoned child himself? does he not believe that he will live long enough to wait? if so, why would he leave makino with that responsibility at all? characters can make selfish decisions, but i can't see any reasoning from shanks' perspective. this is a problem to me.)

so, in short, no, i'm not exactly a fan of this theory. i just don't see the merit of adding it to the story, when the implications seem to contradict what we know about his character. and again, what is the narrative benefit that outweighs the faulty logic? what do we gain as readers? what does this do for the story? to me, it feels like nothing at all.

#tldr; 'why is the author acting like he knows so much lol'#oda. PLEASE explain#because i just cannot see it#not in the way i could understand shanks' reasoning when he left uta#i also think this decision undermines uta's entire existence#it gives the impression that shanks is. idk. unaffected?#parents are allowed to process the deaths of their children and move on#but we have never once seen shanks process any losses in his life. hell we don't even the poor man CRY#and so as a result this writing choice just feels.. sloppy#it skips over the potential for depth#if you are going to add lore to a character's story... give it the proper weight it deserves. let uta's memory haunt shanks. shape him#don't just write her in to write her off. otherwise what's the point?#ask#long post

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Santal 33 by Le Labo

Notes from Description:

Top: violet accord, cardamom. Middle: iris, ambrox. Base: cedarwood, leather, sandalwood.

My Review:

Sandalwood scents are very hit or miss to me. I always fear that I'll end up smelling like my mother or *gasp!* a resident of a hippie commune (come to think of it that also describes my mother).

At first I didn't get the hype. I'm going to be honest it did not agree with my skin at first, it sort of dissipated into nothing after about twenty minutes and I never got that beautiful woody bloom that everyone goes bananas over. It felt like a case of olfactory blue balls.

But, because I wanted it to work, I kept wearing it, tried applying it to different bits of my anatomy, using different methods of application... and then one day it worked.

Reader when I tell you I had a come to Jesus moment, I mean the angels started singing.

When it first goes on it smells like a shoe store. There's a very profound and nearly offputting leatheriness to it that mellows out into a subtle spice before blooming into this pure sandalwood wonderland. The cardamom is definitely present on me which offsets some of the more jarring acidity I find in a lot of sandalwood scents. The cedarwood tingles, right there, at the base of the whole thing, a steady base holding everything up and grounding it at the same time. It goes out as a sigh that smells of my grandmother's linen cupboard and the cedar shavings she'd store them with to keep the moths away.

The silage is enormous, and the staying power endless. Some other reviews I read said that it's now so ubiquitous it's almost the smell of the air in certain parts of NYC and London and I can see how. After wearing it for a few days off and on it's still everywhere. Even after laundry the cuffs of my shirt still smell of it, my watch band, the makeup bag I carry to work with me, my hair, my pillowcase. Working as I was each time with a tiny dab from a 1ml sample vial, if sprayed I can only imagine it would be strong enough to block out the sun and incite a bacchic frenzy in anyone within a 13-mile radius.

It's truly gender-neutral. It's sweet but not cloying, woody but rounded, warm rather than sharp. I wouldn't go so far as to call it creamy but there is a softness to it, a well-loved sweater kind of softness that is tempered by the edginess of a truly gender-bending profile (none of that gourmand skew that a lot of sandalwood scents "pour femme" seem to like and nor any of that awful put-upon musk that seems to be the only thing anyone can come up with to make a scent "pour homme"). There's honestly nothing complex about it. It's a minimalist dream, it is exactly what it says on the tin and is all the more luxurious for its simplicity.

The hype is absolutely real.

Rating:

*dives into a pool of this scent. Never to return*

9/10 -1 point for its ubiquity.

Everyone loves this scent, everyone wears this scent. I need to be original or I will perish and in the circles I run in? this is as trite as a June wedding or calling your art "poststructuralist" because it doesn't actually mean anything and you know it.

The beaten dead horse of the fragrance scene. But it was, once, the world's most beautiful horse. May it rest in peace.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adam Roberts Phantom Kitschies 2016

Adam Roberts, in typical overachieving fashion, managed to read enough books to populate a full and complete shortlist.

Adam Roberts

No Kitschies were awarded last year. 2016 was a Kitschless year—for one year only it was Nitch on the Kitsch. Which was a shame, since 2016 saw a wealth of (to quote the Kitschies’ remit) ‘progressive, intelligent and entertaining works containing elements of the speculative or fantastic’. So, [*clears throat*] in my capacity a former judge, I thought I’d post some speculative short-lists for the year the prize didn’t happen.

A disclaimer is needful: I didn’t do last year, what I did in my judging year—that is, read a metric tonne of hard-copy and e-books, the better to be able to narrow down our shortlists. But I read a fair few and some of the books I read were really excellent. So here, for the sake of argument (and please: argue with what I list here) are my Phantom Kitschies shortlists for 2016.

Red Tentacle for the best novel

Naomi Alderman’s The Power is a brilliant jolt of a read, a book happy to inhabit blockbuster conventions in order to suborn them to some powerfully subversive ends. Teenage girls across the world suddenly discover they have the ability electrically to shock others—to burn them, cause them intense pain, even to kill them. The narrative rattles through the immediate implications of this: girls taking revenge on violent or raping men, girls simply being mean, girls collectively coming to a sense of their new power. But the strength of the novel is the way it follows-through its premise, into a world in which men are segregated for their own protection and women, for good and ill and with quite an emphasis on the latter, take control. I particularly liked the way this new society retcons its sense of the world—it becomes seen as ‘natural’ and a product of ‘evolutionary psychology’ for women to be aggressive and violent, since they have babies to protect; if men ever ruled the world their patriarchy would be nurturing and gentle. It’s a raw novel, more than a little jagged—though that also suits its theme—but sparky and engaging throughout. A lightning bolt of a read.

Dave Hutchinson’s Europe in Winter is the third of his ‘fractured Europe’ novels, set in bivalve European set-up—one a tessellation of myriad tiny statelets and ruritaniae, the other, ‘The Community’ a calm but stifling version of 1950s Britain rolled out across the whole continent. The two versions of European reality are linked via a complex of strange portals. Each of the Europe books has a subtly different emphasis and tone, although all provide the pleasures of alt-spy adventures, a cosmopolitan richness of interlocking storylines and slowly unfurling mystery; but arguably this is the best of the three, from its bang-bang opening act of intercontinental railway terrorism through to its big finale. A modern classic.

Lavie Tidhar’s sprawling masterpiece Central Station, set in a future spaceport Tel Aviv, is easily his best book yet (and that’s saying something). What I particularly loved about this is the way it manages to be both gloriously old-fashioned in its SF—an actual fix-up novel set in a space-port in which a colourful variety of humans robots and aliens intermingle—and a distinctively twenty-first century novel about the complex but sustaining inter-relationship between culture and place and memory and technology and change. Most of all it’s about the centrality of stories to who we are, and about the way those stories are always collective and heterogeneous. It’s a marvel.

Christopher Priest’s The Gradual works a simple-enough sciencefictional version of time-zone differences into a haunting exploration of travel, aging and loss. Set like many of Priest’s best novels in his ‘Dream Archipelago’ of endless islands, it is the first-person narrative of composer Sandro Sussken, a citizen of the Glaund Republic on the Northern mainland (a downbeat, authoritarian society locked in an Orwellian permanent war with the Faianland Alliance). The success of his music means that, unlike most Glaundians, Sussken gets to travel from island to island, but in doing so he discovers the titular ‘gradual’, a kind of complex time-slip, or time-stall, that dislocates him from his origins, his family and in the end from the world as a whole. Priest uses his speculative conceit brilliantly to explore what it means to age. It makes me think how rarely the old figure, and how much more they ought to, in progressive narratives of equality and diversity.

Sofia Samatar’s The Winged Histories is a remarkable epic Fantasy, the follow-up to her debut A Stranger in Olondria (2013) and an even stronger novel. It gives us many of the satisfactions of this over-populated mode, as four women—an aristocrat, a military officer, a priestess and a nomadic poet—are caught up in the events leading to an empire-shaking war. But Samatar has the confidence, and the skill, to downplay the conventional satisfactions of narrative. The result is a gorgeous labyrinth of a text that circles through the permutations of its characters, plot, and the history of her world, richly written and formally involuted.

Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad deploys its fantastical conceit—the literalisation of the celebrated 19th-century US ‘railroad’ along which slaves would try to pass to freedom as a network of actual excavated tunnels, railways and stations—with commendable restraint. He is not interested in the worldbuilding mechanics of his idea so much as in the imaginative freedom it gives him to send his heroine, Cora, on a journey encompassing the different violences slavery has manifested over the centuries. It is a novel that renders slave society as vividly and memorably brutal without, at any point, reverting to the pieties of hindsight or historical cliché. An unforgettable piece of fiction.

Golden Tentacle for best debut novel

Yoon Ha Lee’s Ninefox Gambit recasts Korean legend in a densely rendered high-tech future universe governed by ‘calendars’, sort-of computer programmes that determine the nature of reality itself. It’s a book that boldly drops its reader into its properly futuristic and alien cosmos—an interstellar empire called the Hexarchate in which six factions each with unique skills are competing for power. Though it might put some readers off, the advantage of this approach is that when the book clicks fully into focus it does so with kaleidoscopic brilliance and coherence. The game theory and maths, all the politics and military tactics, neatly offset some nicely written central relationships.

David Means’s Hystopia is a brilliant, baffling and expertly fractured novel set in an alt-1970s America in which Kennedy wasn’t assassinated, and Vietnam veterans are being treated for PTSD with psychedelics. It is steeped in the flavour of its era, and manages to be simultaneously weirdly familiar and intensely strange—quite the combo, that. I have to concede it’s a little distorting describing this as a ‘first novel’ (even though that’s what it is) because Means has been honing his craft writing short stories for decades. The technical skill shows: Means’s multi-viewpoint and deracinated approach could easily have slid into mere messiness; but though the novel is often violent it is also potent and, in its way, coherent.

Wyl Menmuir’s superbly eerie The Many is, though short, a tricky book to summarise. Suffice to say that as an exercise in unnerving the reader, this cryptic, powerful novella is remarkable. Its seemingly simple plot, about a young man coming to a Cornish seaside village to live in an abandoned cottage whose previous owner had drowned, invokes a sort-of ghost story, or perhaps hallucination, or perhaps dreamtime, to render its poisoned near-future world more obliquely vivid that any straightforward account ever could.

Idra Novey’s Ways to Disappear wonderfully resuscitates a form—magic realism—I had thought dead and buried. A famous Brazilian writer, Beatriz Yagoda, up to her neck in gambling debt, goes missing; her American translator Emma flies down to South America to try and make sense of things. The characters she meets are colourful and varied (indeed, perhaps, their colourful variety is a little by rote), and the tone is lightly comic, but as the story goes on it becomes stranger and more beautiful, and Novey’s background as a lyric poet increasingly comes to dominate the telling. A short novel that leaves rich and strange residue in the imagination.

Ada Palmer’s Too Like the Lightning boldly mashes together eighteenth-century manners and 25th-century adventure in a post-scarcity utopia where which gender-distinctions are taboo and large-scale affinity-groups are carefully manipulated and managed by behind-the-scenes forces to maintain broader social balance. Readers are liable to find the richly mannered idiom in which Palmer tells her story either beguiling—as I did—or, perhaps, archly offputting. But it is worth persevering with the narrative: there’s a piercing political intelligence at work here, of the sort that would surely have delighted the Enlightenment philosophes that inspired it. Intricately worked, and, I’m pleased to say, the first of a very promising series.

Nick Wood’s Azanian Bridges is set in a modern day South Africa still under the sway of Apartheid, and expertly uses this alt-historical premise to estrange and refresh the way racism violates social and human contexts, without abandoning the possibility of bridging this chasm. Sibusiso Mchunu, traumatised by seeing his friend killed at a demonstration, is admitted to a psychiatric hospital where White doctor Martin test him on his new invented, an ‘empathy machine’. The potential of this device, and its dangers, power a compact but very effective thriller. A thought-provoking and promising debut.

from http://ift.tt/2rueAmg

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

PROCESS HACK: Seven Tips for Starting Your Own Game

So, I have a lot of asks sitting in my inbox about how to start / run / write a LARP game. I’m going to give it my best shot, but I’m equally aware that there are many wiser than me out there who likely have their own opinions, and I look forward to learning and reblogging from people who want to add to or disagree with anything I’ve said here. The post is a bit of a monster, so buckle in!

1. DECLARE YOUR INTENT

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: Your policies on diversity & inclusion / equality and accessibility should be the first thing you think about and the first thing you publish when you start making material public, not an afterthought.

Photo from the first event of Pioneers, by @tomgarnett

Now Read On....

It isn’t good enough to write some airy-fairy “~~everyone is welcome at our LARP~~ ^_^” rubbish either. You’ve got to get real with this stuff. This is a statement of principles that your entire game needs to live up to. You have to start considering now:

What the practical limitations facing you are, and

What sort of game you want to run vs. what sort of game you can run.

Is your intent to run a game where everyone has equal access to all IC spaces? Then you can’t put any of those IC spaces in areas only accessible by stairs. Is your intent to run a game where people of all genders feel welcome and included? Then you’d better be prepared to back it up in your setting material by including specific representation of multiple genders in different roles, otherwise your intention means squat. Is your intent to run a game where everyone can participate in combat? Then you need to have a serious chat with yourself about hard vs soft skills.

The statement of principles that you start with will influence every aspect of your game, from setting, to system, to what sites you can and can’t use. It isn’t set in stone - there’s nothing wrong with coming back and revising it later, adding elements you’ve forgotten or clarifying how it relates to your game; indeed I heartily encourage it! But you need to understand now what sort of game you intend to run, and for what sort of people.

Unpopular opinion time: It is not inherently evil to run a game which is not equally accessible to all possible players. LARP is a physical hobby, some variants more than others - it is not wrong to run a game where it’s easier to play a fighter if you have 20/20 vision and the use of both legs; it is not wrong to run a game where it’s easier to play a mage if you are highly numerate and can speak fluently in public. It’s not even wrong to run a game at a site that’s impossible to access by wheelchair, especially if that’s the only site available to you.

What is wrong is not clearly signposting those restrictions up front in your publicly accessible game material, and making whatever reasonable adjustments you can to compensate. It is worse to be welcoming and “talk the talk” in your advertising material, then fail to follow through on the field, than to state simply and clearly what access restrictions your game comes with - your players need as much information as possible to decide for themselves whether the game is right for them.

If you want some examples of what an “OC policies” or E&D / accessibility statement might look like, try these:

Death unto Darkness OOC policies

Profound Decisions Accessibility Policy

Profound Decisions Equality & Diversity Policy

Tales out of Anchor Event Rules

Photo from the first event of Falling Down, by @tomgarnett

2. WRITE FOR THE SITE

Now that you understand what inclusion and accessibility requirements you need to meet, you can pick a site!

If you’re a university or small-town LARP, this decision may be from a very small pool indeed; you may even find after looking at your options that you need to go back to your accessibility statement and revise it or manage expectations. That’s fine - you can only work with the resources you have; just make sure that you’re doing site recce & viewings with accessibility in mind.

If you are mobility impaired or have a friend who is, they may be willing to help you out by conducting an accessibility survey of your potential site. Don’t assume they’re obligated to help you, but there’s nothing wrong with asking politely.

It is important that you match the game to the site, not the other way around. My LARP career is littered with examples of start-up games which had a fantastic concept of the world they wanted to run in, and which implemented shockingly badly in play because the site they eventually found didn’t match up with their requirements.

What do you have? A lot of single-use mixed-terrain woodland? Then small-party linear adventures can be an excellent feature of your game! A big open empty field with nothing in it? Have some linefights, or a big friendly diplomacy-heavy IC camp! An abandoned glue factory but no outdoor terrain? Claustrophobic space-prison survival horror it is!

At all costs, avoid marrying yourself to any particular gameplay style or type before you know what site you’re working with.

Photo from the first event of Regenesis, by @tomgarnett

3. GAMEPLAY BEFORE NUMBERS

Start thinking about designing the mechanics and working parts of your game the same way the military plans operations: Begin with the effect you want to achieve on the players and then think about the tools you can use to get there, not the other way around. A lot of people who write and run LARP games are mathematically clever and get excited about creating intricate, clever systems like D&D; that’s fine, if that’s the sort of game you want to run, but you need to be focused on what the players get out of it and how it works in play as the first priority, not as an interesting side effect.

Your “system” - the crunchy numbers bit, the magic, the calls, the death counts, the bean bags, the Nerf guns, whatever it is - is a mechanism to create the kind of gameplay you want, not an end in itself.

Once more: System is a mechanism to create the kind of gameplay you want, not an end in itself.

Photo from the first event of Slayers LRP, by @tomgarnett

4. PLAYTEST THOROUGHLY

Take every possible opportunity to playtest. Give your mechanics, your setting, your character creation and your fight system to fellow LARPers. Give them to LARPers whose opinions you disagree with, who like a different type of game to you, who you argue with on the internet. Give them to friends and family. Give them to total newbies and ask them how accessible they are. Ask them to murder your darlings. Swallow your pride and take all feedback with equanimity - use it to hone and refine your game. Don’t feel the need to change everything someone objects to, but understand where the objection comes from and how you would meet it from a paying customer.

Don’t try to please everyone “just enough” (unless you are trying to run a national, professional-level game you intend to make a lot of money from, or a local system in a town that has no other LARPs and which you want to have a wide appeal to local nerds); please your target audience as much as you can, and make it very clear who that audience is and what sort of game you are running. Hard work during the playtest will help you articulate these things, and clearly signpost who this game is designed for - and who it’s not designed for.

One useful project management system that my friends Crazy Donkey LARP use when receiving feedback about games is the Stop, Start, Continue heuristic. They ask their audience segment to tell them about things they didn’t enjoy (that they should Stop doing in their games), things they felt were lacking that they should Start doing, and things which worked well which they should Continue doing.

Photo from the first event of Split Worlds, by @tomgarnett

5. THINK ABOUT THE BUY-IN

What is the minimum amount someone needs to know to functionally play this game, and how long will it take them to absorb that information?

If you really care about your game setting, you’ll be overflowing with cool tidbits of history and costume advice and setting material. That is great - and all to the good for stoking the fires of keen from already keen players! But a huge volume of game material (such as, much as I love it, the Empire wiki) can be really offputting for a new player. It’s in your interests to boil down “the basics” as far as possible, and present them in a clear, obvious one-pager which allows a new player to quickly and easily absorb them. This also helps accessibility for people who have issues reading, or absorbing, a large volume of text at once.

The “At-a-Glance” pages for the six Cultures of Odyssey LARP (now, tragically, ended) are a really good example of how the game writers used a single format to boil down a high volume of culture-specific setting material into a series of representative fragments that gave a new player all the information they need to quickly play a character from that IC culture. Here and here are examples.

In system terms, this is a pretty successful attempt to collate several pages of Odyssey rules into as-basic-as-possible summaries for the reader in a hurry.

The Empire Game Overview is another good page, and the Combat Rules page for Empire is an example of the “Bullet Point / Expand” format that can make it easier for some people to absorb complex rules and system information.

Photo from the first event of Tales Out Of Anchor, by @tomgarnett

6. KIT & COSTUMING

When contemplating what costume looks like for your setting, you should be thinking on two levels: Firstly, what makes the characters look cool and iconic (and, assuming your setting has different classes, nations, professions or cultures which are distinguished by kit, what is obviously different about each one); but secondly and more importantly, what do your players have access to?

Once again here, understanding your target audience is key. For a small, local weekly game that runs for a few hours on a Saturday and targets university students, your costume briefs need to be realistically achievable by people with a low budget and time constraints. For a £250 three-dayer in a castle, you can probably assume your target audience has a bit more spare cash to splash out on frock coats or chainmail or EL wire. If your target audience already has a certain type of kit in abundance - Medieval armour, or Roller Derby kneepads, or leather jackets - build that into your briefs.

Do your best to provide photographic examples of costumes in advance so that players can see what sort of “look” they strive for. When writing costume briefs, pick one or two clear, simple, iconic and easy elements for each brief - like “wide sash around the waist” or “brightly coloured headgear” - and try not to crowd the brief with too many elaborate suggestions for the perfect look. Your players will pleasantly surprise you.

Be aware of body shape and size accessibility when writing your costume briefs. “Empire line” or “broad shoulders” or “ethereal, floaty, elfin clothing” may all sound iconic and straightforward to you, but they are all examples of clothing which disproportionately favours particular body shapes; steer away.

Think about where your monster/crew kit comes from; do you expect crew to self-costume or will you be buying kit for them? What does a properly stocked crew kit room look like? How does that affect your budget?

Photo from Hades, by Oliver Facey

7. SEPARATION OF POWERS

When you’re putting your game team together, clearly define what each role means - who’s responsible for what - and write down those responsibilities somewhere everyone on the team can see them. An amorphous blob of “the refs” which slowly evolves into proper working practices is unlikely to be as efficient as starting out with a head of site & logistics, a head of setting coherency, etc.

You can always change and modify these terms of reference as you go on, but setting them out clearly at the start will cut out an awful lot of drama later down the line.

Try to avoid having any individual make big important setting, system or plot decisions on their own; everyone, no matter how authoritative, should have their work checked by at least one other person who has the power to veto or bring their material to discussion.

If you can, appoint a “conscience” early in the game design process. That person’s job is to stand behind you every time you’re about to make an important decision or rules call, or finalise a plot, or do something you think is really cool, and ask “What about player agency?” and “But how do the players interact with this?” and “What effect does this have on the players?”

Photo from Gruntz, by Oliver Facey

8. CREW

Where is your crew from? How do you keep crew coming back for more? How many crew do you need to run a successful game?

If you’re starting up a local small linear style system, inculcating an early culture of “crew one / play one” is a good way to keep a regular stream of crew available for more. For medium systems, you might implement a “crew lottery” where people who crewed the last game get favourable placement for tickets for the next event, or discounts on future tickets. You should also do your best to include crew incentives - you’d be surprised how little “bennies” like hats or t-shirts help cement a sense of group identity and belonging among your crew cohort.

Out of the number of crew you need to run your ideal event, 2/3rds will book, and half of that number will actually show up. Be prepared and write your encounter based on low crew numbers as a contingency.

All photos from this set are from the first games of new systems, or one-off games.

69 notes

·

View notes