#and now the powers that have destroyed mine and my friends cultures are endorsing ANOTHER colonist state. calling the people that are sick

Text

i think i would like to make every genocidal imperialist state explode into one million dust particles

#i am upset#the land i live on was violently taken from my friends ancestors#and we're about to lose a referendum which could have done so much for reconciliation. my country was built on genocide#my own land does not belong to me. my country is in the hands of the worlds most violent imperialist power#me and my family have lost so much because of it. i cant speak my own language. i cant live safely in my own home.#my body remembers the trauma my dad and grandmother went through#and now the powers that have destroyed mine and my friends cultures are endorsing ANOTHER colonist state. calling the people that are sick#of the ethnic cleansing and the dispossession and aparthied ''unprovoked'' agressors as if they have not suffered for decades#none of this is like. genuine political commentary or anything. i dont know much about what im talking about.#this is more of an emotional outburst. im just upset about what me and my friends and the people that are so similar to us have been through#argh.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

QUARANTINE LETTER #4

A fourth letter in our quarantine series, from our friend Icarus.

-----

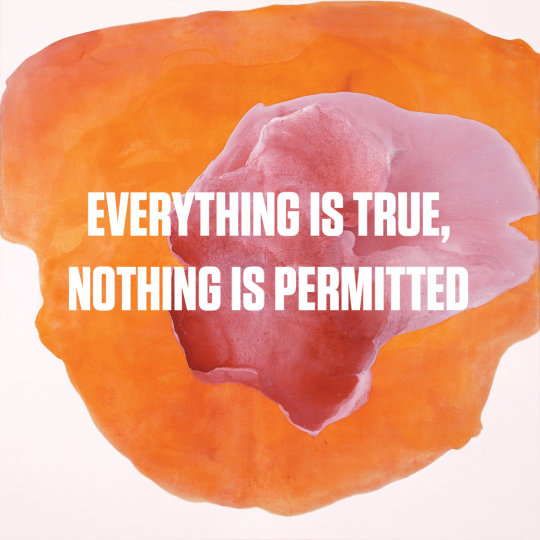

EVERYTHING IS TRUE, NOTHING IS PERMITTED

“They’ve already destroyed everything, all the structures we believed in, trusted. Maybe we’re in a transitional phase, you know? There’s some sort of substitution going on. Meanwhile, we’re navigating in a tremendous vacuum, vaguely oriented by the stars but with no true reference point. Our compasses have gone wild, spinning madly, attracted by thousands of magnetic poles. We might as well throw them out the window, they’re obsolete. It’s just us and the night sky, like it was for the early explorers, while we wait for new, more advanced navigational devices to be invented. My only fear is that the stars have somehow gotten out of place and will be no help as references either.”

- Ignacio de Loyola Brandao, “And Still the Earth”

Dear friends,

It can be strange to intervene in someone else’s debate, but I don’t believe you’ll hold it against me if I do. Over the past weeks, I’ve rather enjoyed the commentary and exchange of letters between my friends, August, Kora, and Orion. Something about the reflections of my friends is missing for me still, so I’ll chime in without wasting too much time, I hope.

QUARANTINE: INCOMPLETE—WHAT WE THINK IS HAPPENING IS ONLY SOMEWHAT ACCURATE

Today, millions of people are working. In warehouses, in offices, in fields, kitchens and storerooms; from the computer, the sorting room and at construction sites, millions of Americans are sharing the coronavirus with each other and with their neighbors. Many of them are asymptomatic, a portion are not sick yet, and certainly some of them are still hiding their symptoms from their families, employers, and coworkers. No zombie apocalypse is complete without the inconsiderate hot-head who insists, deceptively, that his injury is “nothing, it’s fine, let’s keep moving”. Orion wrote that the virus imposes “its own temporality, which immobilizes everything.” If only.

Logistics, shipping, freight, warehousing: these are some of the largest sectors of the 21st century workforce, and they are all on overtime. From Whole Foods to Old Dominion, these disposable workers are simultaneously killable - insofar as the market facilitates their endangerment via assured contact with the virus - and indispensable, insofar as they must not be allowed to strike, unionize, or cease working that this society may minimally function. In these industries, overwhelmingly, black men and immigrants are crammed into job sites without any protective equipment. In other words, they are proletarians in the classical sense, and they are still at work. A true quarantine, a dignified exodus from the commodity society and its extensive productive apparatus, would halt all forms of labor and toil, a circumstance as yet unrealized. If we can say we are living in a quarantine, we must say that it is still incomplete.

AUTONOMY OR AUTOMATA?—THE PANDEMIC AFFECTS ALL OF HUMANITY—WHICH NO LONGER EXISTS AS SUCH

What we once called "society" (an entity which now insists it can survive unity and distance simultaneously, even distance for the sake of unity), has been replaced by billions of apparatuses. These apparatuses constitute a vast ACEPHALOGRAM - a system of machines designed to trace and retrace the consciousness of a world that has definitively lost its head.

The period of real domination opened by the aggressive economic and political restructuring in the 70s, 80s, and 90s - “globalization” - has pushed a vast quantity of workers out of manufacturing and into service related industries. Services being overall less profitable then commodity manufacturing and heavy industry, other technological implements such as we see emerge from Silicon Valley have filled the gap, so to speak, of lost profits for the economy by allowing large advertising and analysis firms to mine directly the collective human ambitions in art, sex, politics, culture, and society. To open up this mine, which has produced an existential ruin comparable to the environmental ruin associated with mineral mining, the internet has developed as a global network of pseudo participatory information systems. The data thirst of these industries cannot be sated by the administration of facts from the center or top, they must be produced by the masses directly. But technology does not simply catch data falling naturally from the sky or running off the gutters of consciousness. It produces data by arranging relations such that they produce content that can be bought and sold. Under such conditions, the medical, political, technological and ontological crisis of a pandemic cannot help but be experienced as a video, a collection of tweets, graphs, memes, as background noise, as a conspiracy theory, as a genre in the endless relay of notifications.

THE MIDDLE OF THE BEGINNING OF THE END—WHAT MAKES INDIVIDUAL INTERPRETATION POSSIBLE, MAKES COMMON UNDERSTANDING IMPOSSIBLE.

The truth is that social media has allowed billions of people to coordinate themselves into large and small containers of meaning and virtual energy. These containers, ecosystems of signs and signifiers, by dint of their polycentralized arrangement, function as an epistemological subversion of established truth-making infrastructures that require a certain amount of hegemony or global purchase: the scientific method, fact-checking, and debate. Occasionally, the understanding produced in these containers, theory-fictions more than anything else, incidentally conform to an intensity with physical correlatives capable of overpowering police infrastructures and seizing public space, as we saw across the world in 2019. More often, the echo chambers, as they are often called, curtail feelings of common dialogue and the perception of shared futurity that would be seemingly embedded in such a “global” sharing of information. This curtailing allows people of all “types” to be bundled together as data sets, insulated from the experience of true diversity of thought, of experience, of analysis. The polycentralized arrangement of the internet today may be even less participatory than previous eras of information sharing, even though it doesn’t feel that way.

Commentators and critics have used the ongoing crisis to delay the moment of our collective education with unwavering ideological entrenchment. At work, it is not uncommon for me to hear small business owners and day traders talk about the failures of socialized medicine in Italy, implicitly endorsing greater privatization in the US. Among activists, liberals, and leftists, it is impossible to imagine a greater indictment on the privatized, decentralized, healthcare system than what is taking place. Apocalyptic Christian sects believe the government is going to repress churches for gathering, and social justice advocates believe the coronavirus crisis will be “the same, but worse” on every oppressive axis. It’s hard to imagine another reflex.

While they recognize that the internet has plunged billions of people into a pulverized simulacrum, some of my comrades would have us devote ourselves to the dissemination of real news, of verified and sober analysis, of scientific rigor, in order to combat the prevailing disarray. This warms my heart just as it saddens my intellect. We have always been machine-breakers, in a way, revolting against the forward and crushing movement of industry to preserve a less alienated experience of reality, labor, and community. We aren’t wrong for that. We should be reliable sources of information, but not because we will convince people with our reports — which may no longer be so possible online — rather because we believe it is the right thing to do, and because we can at least proceed on a clear and shared basis with each other. But what other strategies could we utilize for analyzing the world that would allow us to act within the protracted vertigo, without trapping ourselves or others in ideological camps, and without losing revolutionary aspirations in a world where global verification of facts seems impossible, but where universal need for a transformation, fascistic or revolutionary, feels like common sense?

EVERYTHING IS TRUE, NOTHING IS PERMITTED—THE SYSTEM REDUCES ITSELF TO A PURE FLUX OF DYNAMICS

“We dreamed of utopia and woke up screaming

A poor lonely cowboy that comes back home, what a wonder”

-Roberto Bolano, “Leave Everything, Again”

For millennia, the administration of public facts was the cornerstone of political power, and stamping out alternative readings the chief objective of the repressive machinery. The ruling bureaucracy has organized itself to prevent any global loss of control. They’ve always done that. What is surprising is how readily, since 9/11 at least, perhaps much earlier, they have abandoned many important methods for doing so. As the possibility of imagining its own future became increasingly stamped-out, the reigning order abandoned any pretense of pursuing the ideals it propped itself up on, its sole promise being to ward-off unforeseen eventualities. Without embarrassing myself with long-winded arguments about things I am ill-equipped to discuss - certainly less knowledgeable than my dear friends are on such matters as philosophy and critical works - I’d prefer to refer to an argument advanced by Brian Massumi in his essay “National Emergency Enterprise”. In this piece, he argues that a primary strategy of governance is to identify all possible causes of a scenario. The market refashions environments that submit the living tissue of relations one and all to technological “dataveillance”, information which, in principle, allows the administrators of such a system to model its every possible outcome, translating every action into a trans-action, while ensuring that every aberration meets a form of control. He utilizes the example of a forest fire, but we can just look at the pandemic and it’s consequences.

The ruling class everywhere, has argued and governed as if the coronavirus is "merely the flu", justifying late responses and insufficient care, while also closing borders and taking emergency measures as if we are living in a veritable plague. There are strategies attached to every discourse, interests silently advanced with each interpretation, and powers produced and mobilized by every kind of theory and operation. Anyway, we have been living in the fall out of multiple convergent strategies for controlling and responding to this situation. The governors of the world, at least of the democratic countries, are basically throwing things against a wall and seeing what sticks. We can imagine that modeling and predictions are conducted endlessly based on analytics produced through data mining and network analysis purchased from Google, Facebook, Twitter, and elsewhere. As technocratic governments subordinate welfare states to the "science" of neoliberalism, the nihilism of the powerful today subordinates everything to the "science" of control.

Anyway, who organizes oblivion today acts with no principles and can only speak in lies. What does this mean for the rest of us?

NOTHING IS EVERYTHING, TRUE IS PERMITTED—TRUTH DOES NOT REQUIRE A SUBJECT ONLY LIES DO. LET'S KEEP IT REAL, WHATEVER THAT IS.

We can and are responding to this situation. The most important thing, from my perspective, is that we develop a vibrant enough ecosystem of strategies, corresponding to the largest possible interpretation of facts, without dividing our sympathies and concerns into rival fiefdoms and ideological sects. There are benefits to arguing that nothing of the situation is unique, that in fact the worst off before are the worst off now, that today simply represents an opportunity for us, etc. I am not among the comrades advancing this position, but I want to see the results of that framework as soon as possible, if it does not in fact raise the threshold for meaningful interventions. There are benefits to arguing that the quarantine is not deep enough, that the politics of mobilization have failed utterly to devastate the economy, but that a true lock down of the world could resemble the worlds first ever international wildcat general strike. I want to hear advocates of this position contend with the possibility of carceral interpretations of this argument. For those planting survival gardens, for those running autonomous rent strike hotlines, for those training in firearms, I want us to develop a shared enough perspective to see that there is a simple unity in our strategies, which is what is precisely, and incorrectly, attacked in Kora’s most recent letter to Orion: our autonomy. Beyond any individualistic misinterpretations, it is my perspective that the ability of human beings to self-authorize our activity, to determine our shared destinies, to control supply chains, vital infrastructures, and means of subsistence without the mediating factors of the market, are necessary prerequisites for a dignified life on earth. This is not to say, as Kora has intelligently argued, that anyone could come to control the unfolding course of history - a delusion that preppers, governors, and revolutionaries have all held - but precisely that autonomous, self-organized, structures are the only structures capable of responding quickly enough to the destabilizing, frightening, and uncertain futures lying in wait regardless of what we or anyone else do. We must utilize the current situation to repolarize the circumstances to the best of our ability around foundational concerns of power: on the one hand, there are all of the people of the world, some of them bastards we would not live with, and our shared need for dignified healthcare, housing, sustenance, and livelihood; and on the other hand there are all of the bastards waiting this out on yachts, manipulating public data for the sake of a geopolitical PR battle, utilizing the pandemic to pursue totalitarian power fantasies and clampdowns. We don’t need to steer the ship forward, we need to be able to swim in the wreckage.

Sorry, I wrote too much. Thanks for reading and I look forward to reading what others think soon.

-- Icarus

04.11.2020

STATE OF EMERGENCY, DAY 40

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ross Barkan, Exterminating Angels, 46 The Baffler (July 2019)

The American myth of the progressive prosecutor

© Kelsey Niziolek

When Kamala Harris spoke in front of the Commonwealth Club of California in the winter of 2010, the presidency wasn’t yet on her mind. Or, if it was—as it usually is for any ladder-climbing politician with a pulse and a dream—she wasn’t going to talk about it. Harris was San Francisco’s district attorney, one year away from narrowly ascending to statewide office. The following year, she would be sworn in as California’s attorney general; in 2016, she was elected to the Senate and is now a top-tier candidate for president, at least in the view of many pundits.

It is unlikely the Harris of 2010 believed that what she was about to say to the Commonwealth Club would be held against her in a future primary race. While the criminal justice reform movement had gained ground in the early days of the Obama presidency, the tragic deaths of Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, and Eric Garner were still several years off.

Harris, then, was on safer ground laughing about locking parents up.

“I believe a child going without an education is tantamount to a crime. So I decided I was going to start prosecuting parents for truancy,” Harris said that day. “Well, this was a little controversial in San Francisco.”

Harris, laughing, broke into a wide smile, the subtext clear enough: the granola-crunching investment hippies in Haight Ashbury weren’t going to like this one.

“Frankly, my staff went bananas. They were very concerned because we didn’t know at the time whether I was going to have an opponent in my re-election race,” Harris continued. “But I said, ‘Look, I’m done. This is a serious issue and I’ve got a little political capital and I’m gonna spend some of it.’”

Harris went on to describe her office as a “huge stick,” with letterhead alone that could compel people to do what she wanted. In a letter to every parent in the school district, Harris outlined the connections between elementary school truancy and a future life of crime. “A friend of mine actually called me and he said, ‘Kamala, my wife got the letter, she freaked out, she brought all the kids into the living room, held up the letter and said if you don’t go to school, Kamala is going to put you and me in jail.’”

A clip of the event, unearthed anew in January, quickly went viral. Progressive critics faulted Harris for joking about jailing parents and misdiagnosing a problem that runs much deeper than a morality deficit or lack of supervision. California public schools are still woefully underfunded, and criminalizing truancy can have the unintended consequence of sending more young people of color to prison. In every sense, Harris’s remarks at the Commonwealth Club have aged terribly, especially as she vies to become the nominee of a diverse Democratic Party that has rejected wholesale its tough-on-crime heritage.

So, fittingly, Harris’s candidacy has sparked new questions on the left. Should a former prosecutor—someone who celebrated putting human beings in cages—be elevated to the presidency? Can someone who held such a position be considered an ally of the ascendant progressive movement? Is prosecuting an original sin? Is the institution, even in an age of reformist prosecutors, beyond redemption?

The final question is the most pressing for the left and arguably the most difficult to answer. Conservatives—even those who have called into question decades of punitive and wasteful policy that imprisoned a generation of black people and shattered countless communities—do not seriously question the role of the prosecutor. They are there to keep us safe. The judge and jury referee but the prosecutor plays; the courtroom, in every sense, belongs to the prosecutor in the United States of America, and it’s on this field where the lives of the country’s most vulnerable are decided every day.

Liberals don’t usually challenge these assumptions either. Legislators and executives are asked to make better laws that help keep innocent people out of prison. Prosecutors, then, are expected to seek justice within this framework. Good laws, it can be argued, make better prosecutors. And prosecutors, with their enhanced sense of discretion, can change lives for the better—as long as good people are elected to these positions.

American Mythdemeanors

It’s important to consider the relative absurdity of Harris’s remarks in a historical and global context. The United States is a hegemon and cultural trendsetter, but it does not see its governing structures replicated elsewhere. Many countries will take our fast food and pop music. They will pass on our uniquely demented presidential system, preferring the suppleness of parliamentary government and executives who do not enjoy virtual immunity. We are both leader and mutant on the world stage: an example of everything to avoid, yet inarguably an influencer.

American prosecution endures as an anomaly par excellence. The United States is the only country in the world that elects prosecutors. As Michael J. Ellis explained in the Yale Law Journal, local public prosecutors were an invention of colonial America. They were originally appointed and lacked prestige. By the time of the Revolution, the job was only part-time. In state court, prosecutors were paid by the case or conviction; defense lawyers were the stars of the era.

In the nineteenth century, popular democracy fueled the American imagination. Americans wanted more elections, at least for the white men who could vote in them. Reformers believed electing prosecutors would combat corruption and patronage. In 1832, Mississippi changed its constitution to give local voters the power to elect district attorneys, and by the Civil War, most states had followed suit.

At the time, supporters of electing prosecutors gave little consideration to how this trend would affect the criminal justice system. The chief concern was expanding the franchise and making yet another office accountable to voters. The rise of elected prosecutors allowed for the conferral of new power on a post that was once a bureaucratic afterthought. District attorneys, liberated from their status as de facto clerks, gained discretion over when cases could be prosecuted and began to collaborate with newly formed police departments. Almost every state that joined the United States after the Civil War adopted the election of prosecutors, mirroring already existing state constitutions. Today, there are only five states that appoint prosecutors: Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, New Jersey, and Rhode Island.

The twentieth century brought the cult of the prosecutor. Though no president in modern times served as a district attorney or top prosecutor, one came very close: Thomas Dewey. A Republican from New York, Dewey was emblematic of the institution’s growing glamour. As a young Manhattan district attorney in the 1930s and early 1940s, Dewey crusaded against the mafia, successfully prosecuting organized crime kingpins and other nefarious figures. Destined for stardom, Dewey was elected governor of New York in 1942. In 1944, he was the Republican nominee against Franklin Roosevelt when the New Deal architect sought his fourth term. Roosevelt’s margin of victory was narrow enough to assure Dewey the Republican nomination in 1948, when most pundits predicted he would be elected the thirty-third president of the United States.

One seismic political upset later, Dewey’s political career was over, but Harry Truman could not reverse the tide. The prosecutor was now the leading man. Sure, the American public could swoon over their Clarence Darrows and Atticus Finches. But the prosecutor stood atop the machine, inspiring fear and awe while attracting the attention of a fawning press.

Before he debased himself as Trump’s orcish counsel, Rudy Giuliani was a hustler in the Dewey mold, a New York prosecutor bound for greatness. The two poles of prosecutorial eminence in New York are the Manhattan district attorney and the U.S. attorney for the Southern District, often referred to, half tongue-in-cheek, as the “sovereign district” for the wide discretion the office enjoys. Giuliani was a U.S. attorney and, like Dewey, a Republican reformer who chased the mob.

By winning convictions against mobsters like Carmine “The Snake” Persico, the murderous Colombo crime boss, Giuliani became a hero to New York and national media alike, a young Hercules cleansing the city’s Augean stables. Even otherwise cynical reporters were not immune to the Giuliani mythos. In City for Sale, their investigative tome of 1980s municipal corruption, Wayne Barrett and Jack Newfield portray Giuliani as a white knight with a moral compass that always pointed true north.

Giuliani parlayed his local fame into two terms as New York City’s mayor, and for a time, he was viewed as serious presidential timber. The dream would die quickly in 2008 following humiliation in the Florida Republican primary. It would take another New York Republican, a thuggish real estate developer and tabloid obsession, to propel him into the White House’s inner circle.

In retrospect, Giuliani’s turn as prosecutor-as-hero was exceedingly well-timed: the second half of the twentieth century would make local district attorneys and federal prosecutors into crusading protagonists of a dangerous myth, one that would destroy the lives of countless black and brown Americans. In the late 1960s, violent crime spiked across America and continued to climb over the next two decades—against which Democrats and Republicans united to endorse policies that would fuel an unprecedented incarceration boom. The number of people locked up in the United States has quintupled since the 1980s, ballooning to nearly 2.3 million, a population larger than almost every American city. It is a level of imprisonment far beyond all other liberal democracies.

Enemy Combatants

We are a prison state, but how exactly did we end up that way? Were the police and political elites simply out of control? The journalist Emily Bazelon thinks she has an answer. In her well-researched, provocative new book, Charged, she traces a line directly from punitive prosecution to the prison explosion. “American prosecutors have breathtaking power, leading to disastrous results for millions of people churning through the criminal justice system,” Bazelon writes in the book’s introduction, noting that local prosecutors handle more than 95 percent of America’s criminal docket. “Over the last forty years, prosecutors have amassed more power than our system was designed for.”

Bazelon argues that the “unfettered power of prosecutors is the missing piece” in explaining America’s unconscionable incarceration boom. “Our justice system regularly operates as a system of injustice, grinding out unwarranted and counterproductive levels of punishment. This is, in large part, because of the outsize role prosecutors now play.”

Prosecutors and defense lawyers, in the layperson’s conception of the criminal justice system, are perceived as quasi-equals. On shows like Law and Order, a charismatic assistant district attorney jousts with a suave, sometimes garish defense lawyer. They have their own bags of tricks. One will win, one will lose, yet they each have a reasonable shot at victory. It’s simply a matter of who makes the best case, who produces the most scintillating comeback.

Any person who has the misfortune of entering the criminal justice system knows prosecutors and defense lawyers are asymmetrical combatants. This is Bazelon’s point. One has a cache of sophisticated weaponry, each carrying the power of annihilation, while the other waves around a stick, or hopes words are enough. They usually aren’t.

In the American system, prosecutors stand even above judges. They answer to no one and make virtually all key decisions in a case. They choose the charges, make the bail demands, and regularly determine the plea bargains. They can add charges on a whim. They can delay trials indefinitely, letting defendants rot in jail cells. They are the angels of mercy and the executioners. It all depends on which one you run up against.

Prosecutors have another weapon at their disposal: the press. Powerful prosecutors can selectively leak favorable tidbits of their investigations before indictments are even brought. In larger media markets, this is the preferred mode of operation, endangering defendants long before they even make it to trial. Striking details of former U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York Preet Bharara’s most high-profile investigations often reached daily newspapers weeks or even months before formal charges were filed. His targets could be tried and convicted in the court of public opinion. His successor, the Republican Geoff Berman, is not so flamboyant, and overeager journalists have been forced to subsist without regular leaks.

Crime Organized

An overwhelming majority of cases in the United States of America end in plea bargains, never even going to trial—a trend that has only worsened in the last half century. Prosecutors can intimidate defendants into avoiding trials and pleading guilty, even if they didn’t commit the crime. The pressure to plea is immense: heading to trial always carries the risk of a far worse sentence if a jury or judge finds a defendant guilty.

For the vast number of people, many of them low-income and nonwhite, faced with this devastating choice each day, there is no way out. Either take the plea and leave with a criminal record or go to trial with an underpaid, outmatched public defender, facing a jury ready to convict you because you match their media-inflected conception of a criminal.

It’s no coincidence that the culture of the late twentieth century valorized a man like Giuliani, a conservative white prosecutor who, when he became mayor, encouraged his militarized police force to crack down on the African American and Hispanic residents of his city in the name of controlling crime. Prosecutors are human beings who take cues from the culture; if the zeitgeist cries out for prisoners, prisoners they will make. More important, many prosecutors are politicians, typically elected in four-year cycles, responsible for meting out justice and glad-handing with the very people (other politicians, the police they work with) they are theoretically charged with trying to lock up.

There is a reason other countries choose not to elect prosecutors—they do not want to reproduce scenes like Kamala Harris’s at the Commonwealth Club in which prosecutors yuck it up about political capital. This is the danger of the system we have inherited from our ancestors. The gravest matters—guilty or innocent, life or death—are reduced to whether prosecutors believe such choices will alter their political futures.

Status Quo Economy

Some have argued that electing prosecutors itself is dangerous. An elected official must single out tangible results for the district he or she represents or champion certain votes that led to direct positive outcomes. The lines of argument are clear: I’ve done enough for you, return me to office so I can do more.

Prosecution is murkier. What is a deliverable? What counts as a win? Most elected prosecutors point to convictions and crime rates. They believe racking up guilty convictions or appearing “tough” on crime will help them get re-elected. One 2015 study found that 95 percent of prosecutors in America are white, fueling a process that is inevitably tortured and toxic: powerful white people, usually men, campaigning to imprison large numbers of people who do not look like them. The progenitors of Jim Crow would be proud.

Elected prosecutors are expected, in most instances, to bring justice in cases where police officers have killed civilians, many of them black. The construct of the office and local electoral politics make this all but impossible. Police unions endorse district attorneys, donating to their campaigns and mobilizing votes. To lock up more people, district attorneys must constantly collaborate with police. Again, Law and Order—accurately this time—regularly illustrates this reality. How can the same district attorney who was endorsed by police and relies on the police to put more people in cages also prosecute them when they break the law? In New York, at least, cases of police killings of unarmed civilians are now in the hands of the state attorney general instead of local district attorneys. The attorney general is also elected but has more remove from individual localities, allowing a degree of impartiality. District attorneys, predictably, have decried this change.

Politicians fall into a similar camp. A district attorney, with rare exceptions, does not get elevated without support from the political establishment and does not remain in power without the help of elected officials and party organizations. The same dynamic that thwarts adequate investigations of police misconduct rears its head when district attorneys, particularly those who want to stick around, target the very politicians who donated money and lent their endorsements and volunteers to the cause. Even when district attorneys pursue political corruption cases, the public is left to wonder how fair they can really be. The party boss helped put the district attorney in office; the young black man just prosecuted on a marijuana possession charge did not.

Shiny and Merciful

We are now in the era of the reformist prosecutor. This is a new phenomenon. The criminal justice reform movement, which has gained most of its steam in the last decade, only recently expanded its focus to electing new prosecutors. The liberal billionaire George Soros began spending millions in 2016 on efforts to elect African American and Hispanic district attorneys who share his goal of reducing racial disparities in sentencing. Soros knows how to get bang for his buck. It costs less to elect a district attorney than a senator, and the senator will never have such a tangible and immediate influence on the lives of thousands of people like a district attorney can.

For progressives, there are now shining beacons. Larry Krasner, the new Philadelphia district attorney, is a former public defender who ended cash bail in many cases, sought more lenient sentences, and forced his prosecutors to explain for the public record why taxpayer money should be spent to incarcerate a particular defendant. In 2018, Krasner’s office worked to expand a public list of police officers who lied on duty, used excessive force, violated civil rights, or racially profiled.

In Chicago, State Attorney Kim Foxx raised the threshold for felony theft prosecution to reduce the number of shoplifters who go to jail. Mark Dupree, the district attorney in Kansas City, Kansas, created a unit to scrutinize old cases with questionable police practices. And Rachael Rollins, the new district attorney in Suffolk County, Massachusetts (which includes Boston), won office last year promising to end prosecution for low-level, nonviolent crimes.

Bazelon and other observers believe the best hope for undoing the damage of the mass incarceration age is the election of more progressive prosecutors. They are optimistic that this groundswell, a product of the Civil Rights movement, Black Lives Matter, and even libertarian skepticism of government overreach, can begin the work of permanently altering a system that has existed largely to shackle poor and black people.

Eric Gonzalez, elected Brooklyn’s district attorney in 2017, got his start in the tough-on-crime 1990s. He is now one of the leading progressives and a subject of Bazelon’s book, in part because he is guiding the criminal justice system of one of the most populous counties in America. In April, he announced he would no longer contest most parole cases. This is the mode forward-thinking prosecutors now operate in, and it’s a welcome change from fifty years of deliberate punishment. The progressive sets aside (some) of their weapons in the name of justice.

In terms of how the word “progressive” is understood in our political context, the prosecutor who champions reform is not like the senator or presidential candidate proposing a bevy of new policies and laws to strengthen the social safety net. Progressive prosecutors don’t want more government in people’s lives—ultimately, they want less. Progressive prosecution concerns the restriction and negation of power. It’s about discretion.

“The Progressive Prosecutor’s Handbook,” a guide published by UC Davis Law Review, suggests the new breed of prosecutors allow for internal appeals and reviews of wrongful convictions; disclose exculpatory evidence; avoid the pursuit of fines, forfeitures, and fees; reduce case delays; pursue independent and transparent investigations of police shootings; and diversify staff. The new progressive prosecutors adhere to many of these benchmarks, and candidates for the office, at least in Democratic-leaning areas, are in support of many of these initiatives.

Cutting the Dragnet

Reform movements are confined by institutions until they seek to topple them altogether. Progressive policing practices can’t negate the reality of an armored human being with a uniform, a gun, and handcuffs. Prosecutorial reformers—or those who look to elections as the answer—are dependent on the wisdom of individuals and a political climate that encourages their best instincts. Give Eric Gonzalez or even Larry Krasner another violent crime wave of the likes we saw forty years ago, and will they keep restraining themselves? As voters, who do not pay much attention to the nuances of a district attorney’s office, cry out for more convictions in the erroneous belief that these alone will halt rising crime, will these prosecutors be able to defy popular appeal and stay the course?

Today’s progressive prosecutor is working to strip away the armaments, to present a softer veneer—but they haven’t quite vanished. Crime is a social and economic problem, and the prison-industrial complex has not brought healing. Most reform comes at the provisional discretion of sage prosecutors; few laws are being written to strip them of their awesome power.

Prosecutors’ offices are complicated organisms. The largest employ hundreds of lawyers, investigators, and support staff. The elected district attorney can only keep so much watch over the so-called line prosecutors who are in the grind, handling cases daily. Just as important, the elected district attorney is not about to shrink the office permanently or limit its scope. He or she merely sets some power aside for what is, naturally, a limited amount of time, since they can all only serve in office or live so long.

The institution will only allow reforms to go so far, so maybe progressives should place less faith in well-meaning prosecutors operating in a retrograde system. This is thrust of a recent argument in the Harvard Law Review, “The Paradox of ‘Progressive Prosecution.’” Reformers ask prosecutors to restrain themselves in an environment that allows for near unlimited leverage over defendants. In sprawling offices that process many thousands of people a year, this is a daunting task, especially when most lawyers who seek to work in district attorney’s offices are conditioned to “win” cases and score convictions.

What about the jurisdictions that won’t embrace progressive prosecutors at all? Many of the African Americans most victimized by our system are clustered in the Republican-controlled Deep South. If a conservative majority won’t allow Krasners to take bloom in all the counties and municipalities that regularly send Republicans to the state legislature and Congress, criminal justice reform remains theoretical to those who desperately need it most. There are more than 2,300 prosecutor offices in America and the zeal for change has not taken root in many of them.

Few have called for defunding or shrinking prosecutor offices altogether. This is still a radical suggestion outside the lexicon of most reformers—much like calls to end cash bail, which can lead to questions about the morality and efficacy of jails existing in the first place. To keep black and brown bodies outside the dragnet of prosecution, it only makes sense to reduce the net or cut it altogether. What this will look like remains to be seen.

Any movement toward a narrower, weaker mode of prosecution is guaranteed to spark backlash, especially in an era that so readily manufactures psychological threats, whether it’s terrorism, immigration, or fears of fresh crime waves. Even the most noble-seeming people, when handed power, are loath to surrender it permanently. Kamala Harris enjoyed it, after all. As she said, she had a little political capital. Now she’s spending it.

#kamala harris#liberalism#hypocrisy#prison reform#incarceration#carceral state#prosecutors#criminal justice system#criticism#emily bazelon

0 notes

Text

★ INTERVIEW: Salman Khan On Ghosts Of His Past, Attempts Of Image Rehabilitation, And Why Critics Don't Matter !

In an exclusive interview, Khan opens up like never before.

15/06/2017 | Ankur Pathak

It's no secret that Salman Khan has a rather whimsical equation with the press. Whenever I have seen him at events and press conferences, the actor either appears distracted and zoned out or the opposite: funny, attentive, and in the mood to have a baller time.

On Wednesday evening at Bandra's Taj Lands End, Salman is busy gorging on keema pao, straight from the containers of the buffet spread. At the same time, he's also talking to a journalist, calling Pritam, the music composer, 'lethargic and lazy.'

While I worry he'll be his usual inattentive self, Salman, dressed in a black tee and a black denim, takes a smoke break. His film, Tubelight, is days away from release and the pressure is palpable. Khan's eyes look droopy, his gait, tired. He is not only acting in the film but also producing and distributing it.

After waiting for over two hours (that'd come at the cost of standing up a date), Khan sits with me for a chat. Excerpts:

Kabir Khan's Tubelight once again portrays you as a sincere, innocuous, do-gooder who's just too nice to do any wrong -- a trend that started with Bajrangi Bhaijaan and was seen in Prem Ratan Dhan Payo too. What draws you to these characters?

Like you said, the niceness of it. But with Tubelight, my agenda is different -- after the film, I want brothers, who may not have spoken to one another in months and years, to call each other up and forget the differences, if they had any. I want them to be so emotionally overcome that they just let past differences aside and say, "Hey man, let's party." Many times, in our families, we end up cutting ourselves away from our siblings. Sometimes the issues are trivial, sometimes serious. But why let it affect you? I hope Tubelight can achieve that. It touches on those emotions. This film is beautifully shot. It's also styled very well by Lepakshi Ellawadi, who did Sultan and is doing Tiger Zinda Hai.

But Salman, do you actually believe films can end family feuds and change people's lives?

Absolutely. I've seen films that have changed my life. And trust me, if a film can change me, out of all people, a film can change anyone. It is the only medium that has such a huge influence on your psyche. When you sit in that dark room and see a character, you are also internally absorbing its ideas and traits.

When you see nobility being projected by a hero, you are inspired to emulate it. This is one of the reasons why I haven't ever played a negative character. Negativity in a character doesn't impress me. Say if you have a character who earns a living through corrupt means, man, that puts me off. I will never play a dark character. Underdogs impress me. Those who make it against all odds impress me. I want to tell their stories.

But doesn't that limit you as an actor? A lot of great performances in cinema have come from actors who've played dark, twisted, villainous roles.

Well, I don't know. From the stuff I do, a Dabangg is a character that is sort of, somewhere-in-between. His intentions are good, actions aren't all that good. So you try and balance that off. My next, Tiger Zinda Hai, also veers in the grey area. I am also doing a crazy dance film. So while I do wanna portray characters which are inherently nice, I don't want them to be one-dimensional. It has to have style and swag and some depth.

While your popularity in the country is undeniably huge, I believe there is a certain section in the audience who aren't your fans and perhaps, they'll never be. While some don't want to be seen endorsing your brand of cinema, some will find hard to appreciate even a good film only because you are in it. A lot, I think, has to do with the notoriety of your past.

Well, I don't know. I move around and meet all sorts of people but funnily, I have never been told that. Neither have I noticed that. But if you say so, all I can say is that I will probably have to work that much harder to win them over. I know it won't happen overnight but I can only hope that some day they'll warm up to me as an artist.

Do you feel you are unfairly judged by your critics?

I genuinely, honestly don't care. I believe that they've no right to take anybody's hard work down. The fans will decide that, in any case. The box-office will prove it one way or the other. What have you done to earn the right to rip a film apart? On Day 1 of the release, you write some rubbish crap. It destroys films and a lot of hard work that went behind making it. With me, of course, it doesn't make any difference. And I think they know it all too well. My films are critic-proof. I am telling them now: go give my film minus 100 stars, why just zero. Let's see how that pans out. My fans will anyway watch my film and that's my reward. It only makes them look like a bunch of idiots.

My films are critic-proof. I am telling them now: go give my film minus 100 stars, why just zero. Let's see how that pans out. My fans will anyway watch my film and that's my reward. It only makes them look like a bunch of idiots.

I am pretty sure that our critics aren't under the delusion that they can influence the market of a Salman Khan film. What I want to know is -- what is your analysis? Why do you think they are so insanely crazy about Salman? I cannot even send a negative tweet about you without getting massively trolled by this insane sub-culture of bhaifans.

I don't know. Maybe they think I'm one of them. Maybe they think I am just a regular dude who's chill and approachable and has no airs of being a superstar. And I have remained like that right from the start. I lived in Indore in a boarding school until the age of 16. That really grounded me. I hung around on the streets, went to the farms. There's nothing fancy about my life. I like cycling around the city, I hop into an auto-rickshaw now and then. I don't drive a big car -- I hate big cars. Maybe that, along with the kind of films I do, make them think I'm, I don't know, accessible in a way?

I don't drive a big car -- I hate big cars.

Perhaps. It's hard to decode stardom.

It is. I just think I am a guy who lucked out. Mostly because of the family I was born in. I am immensely fortunate to have the kind of family and friends and the fans I have. Some people come to me and tell me that their children are yet to talk but if they see a Salman Khan song, they jump, react, laugh. They can recall me by my name. Earlier it used to be Prem and Chulbul but now it's Salman.

I don't get it. There are children and youngsters who idolize you and have deified you. They look up to you, want to emulate you, carry your style. But I believe you're obviously a very flawed person to idolize. You've had some very serious court cases against you. Why should anybody just forget and forgive and move on to your next blockbuster?

Everybody has a past. Does that make you a bad person for life? In my case, there is deliberate malice. When people go after you for something you have not done, it's bad. Next thing you know you are running around courts and people are judging you.

For 20 years. 20 years is a long time, man. It's a lot of years. It takes a toll on you and your family. The financial toll on our family because of the cases has been huge.

For 20 years. 20 years is a long time, man. It's a lot of years. It takes a toll on you and your family. The financial toll on our family because of the cases has been huge.

When I was a nobody I had nothing. (Pauses) When I become somebody, I got the magistrate court. When I become slightly bigger, I got the High Court, then. And now when I am in this position, I have the Supreme Court.

Well, something awful did happen. It's not going to leave you.

It will leave me. It's God's way of anchoring me down. If these things didn't happen, I would have lost the plot by now. That's how I see it. It's my journey and whatever it takes, I will go through it. Thankfully, I have family and friends who've stood by me and pointed out whatever happened wasn't correct.

How do you deal with these ghosts of the past, Salman?

I don't have any ghosts. These ghosts have been created by people who are running businesses on them. There are so many incidents like mine that happened and nobody ever talks about them. Whenever there's a hit-and-run that happens anywhere, they drag me into it all over again. I mean, what the hell, come on, man. How much will you go on and on...

Whenever there's a hit-and-run that happens anywhere, they drag me into it all over again.

That's because some do think you got away with it quite easily.

...well, the High Court looked into it and they came up with a verdict which says that nothing of that sort ever happened. Ye sab galat hi hai. The courts said it. But what about the 20 years? What about it? Mere toh wo gaye na? And there's nothing to compensate for that. Nothing at all. And during all this, when I am seen doing a comedy show, or romancing beautiful women, or just laughing, they go like, "Look at this brat. He doesn't care. He is indifferent to what happened." And I am like, dude. It's my bloody job. I have to do it no matter what. I have to do it to sustain myself and pay my lawyers. If I don't do it, where is the money going to come from?

The idea still lingers around that you got away with it because you are a powerful movie star.

Which is not at all true. It's not true. It's all nautanki (mischief). Even now there are 5 out of job people who'll show up on television to debate my case. Some for, some against. It's ridiculous. None of them would have happened if I wasn't a star. None of it.

There's an argument that your Being Human charitable trust has been cleverly designed to rehabilitate your image. That, along with your Mr. Good Boy roles, carves a certain perspective that glosses over your moral transgressions.

Do you have any idea of the amount of work we do at Being Human? We do s***loads of work on a daily basis. I haven't even put my name there, man. It's Being Human. I am not even on the Board or any of the trustees. The idea is that years from now, people should forget who even started the foundation. You have no idea, man. Do one thing: Come and live my life for one day.

(Gets up and walks away)

Huffington Post India

#salman khan#tubelight interview#interview#text interview#tubelight promotion#huffington post india#tubelight#salmankhanfilms#skf#kabir khan's next 2

1 note

·

View note