#and their history of being forced into hegemony with the global order

Text

tbh i think the core of being a union trooper is “it be alright in the long run”. despite being the instrument of violence you’re doing it for the right cause right?? theres no way empire could possibly misusing its monopoly on violence right????

#this post brought to you but the union australian auxies#and their history of being forced into hegemony with the global order

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The system’s attempt to break the revolutionary youth spirit is present in every context and in all of us. The time we are in at the moment is a time of chaos, which brings dangers, but it also includes a lot of chances and possibilities. Florian reminds us that if we know how to use these chances and possibilities, we can take big steps forward together. He analysed that since the breakdown of real socialism (in Kurdish discourse, real socialism is the name given to the form of state socialism that dominated the 20th century and peaked in the Soviet Union), the world has been in crisis. The world’s powers, the US, Russia, and China, struggle and fight to define a new world order. In the last 30 years, a war has been going on that is spreading with increased speed. The attempt to build a new world order, with the US being the leading force, has failed. There are new forces that want to have a “bigger piece of the cake”. The hegemony of one superpower has been rejected.

We should not get bogged down trying to take a stance in every conflict. Instead, we need to look at the third party- where are the democratic structures, the youth and the women in the current global crises? In this period of a third world war, we can see destruction, suicide, genocide and ecological catastrophes all around us, but there is also a lot of hope. We have seen the greatest strike of history in India, uprisings against climate breakdown globally and massive youth demonstrations in France.

The problem we are facing is not the lack of motivation or upset with the current state of our world but the fact that our enemy is very well organised through different forms, militarily, politically, and culturally, while we are often split and divided. Yet even though “the enemy might be big, it doesn’t have the power of the people- we are the people”. If we manage to be united rather than divided by our diversity, we will be an unstoppable force. He ended his speech with Ocalan’s words: “Young we have started, and young we will succeed”.

#anarchism#socialism#freeblr#democratic confederalism#communalism#Revolutionary Youth#Rojava#Kurdistan#Europe

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anarchist Book Club Presents:

David Graeber's Debt: The First 5000 Years

Introduction

What follows are a series of brief reflections (part of a much broader work in progress) on debt, credit, and virtual money: topics that are, obviously, of rather pressing concern for many at the current time.

There seems little doubt that history, widely rumored to have come to an end a few years ago, has gone into overdrive of late, and is in the process of spitting us into a new political and economic landscape whose contours no one understands. Everyone agrees something has just ended but no one is quite sure what. Neoliberalism? Postmodernism? American hegemony? The rule of finance capital? Capitalism itself (unlikely for the time being)? It’s even more difficult to predict what’s about to be thrown at us, let alone what shape the forces of resistance to it are likely to take. Some new form of green capitalism? Knowledge Keynesianism? Chinese-style industrial authoritarianism? ‘Progressive’ imperialism?

At moments of transformation, one of the few things one can say for certain is that we don’t really know how much our own actions can affect the outcome, but we would be very foolish to assume that they cannot.

Historical action tends to be narrative in form. In order to be able to make an intervention in history (arguably, in order to act decisively in any circumstances), one has to be able to cast oneself in some sort of story — though, speaking as someone who has actually had the opportunity to be in the middle of one or two world historical events, I can also attest that one in that situation is almost never quite certain what sort of drama it really is, since there are usually several alternatives battling it out, and that the question is not entirely resolved until everything is over (and never completely resolved even then). But I think there’s something that comes before even that. When one is first trying to assess a historical situation, having no real idea where one stands, trying to place oneself in a much larger stream of history so as to be able to start to think about what the problem even is, then usually it’s less a matter of placing oneself in a story than of figuring out the larger rhythmic structure, the ebb and flow of historical movements. Is what is happening around me the result of a generational political realignment, a movement of capitalism’s boom or bust cycle, the beginning or result of a new wave of struggles, the inevitable unfolding of a Kondratieff B curve? Or is it all these things? How do all these rhythms weave in and out of each other? Is there one core rhythm pushing the others along? How do they sit inside one another, syncopate, concatenate, harmonise, clash?

Let me briefly lay out what might be at stake here. I’ll focus here on cycles of capitalism, secondarily on war. This is because I don’t like capitalism and think that it’s rapidly destroying the planet, and that if we are going to survive as a species, we’re really going to have to come up with something else. I also don’t like war, both for all the obvious reasons, but also, because it strikes me as one of the main ways capitalism has managed to perpetuate itself. So in picking through possible theories of historical cycles, this is what I have had primarily in mind. Even here there are any number of possibilities. Here are a few:

Are we seeing an alternation between periods of peace and massive global warfare? In the late 19th century, for example, war between major industrial powers seemed to be a thing of the past, and this was accompanied by vast growth of both trade, and revolutionary internationalism (of broadly anarchist inspiration). 1914 marked a kind of reaction, a shift to 70 years mainly concerned with fighting, or planning for, world wars. The moment the Cold War ended, the pattern of the 1890s seemed to be repeating itself, and the reaction was predictable.

Or could one look at brief cycles — sub-cycles perhaps? This is particularly clear in the US, where one can see a continual alternation, since WWII, between periods of relative peace and democratic mobilisation immediately followed by a ratcheting up of international conflict: the civil rights movement followed by Vietnam, for example; the anti-nuclear movement of the ’70s followed by Reagan’s proxy wars and abandonment of détente; the global justice movement followed by the War on Terror.

Or should we be looking at financialisation? Are we dealing with Fernand Braudel or Giovanni Arrighi’s alternation between hegemonic powers (Genoa/ Venice, Holland, England, USA), which start as centers for commercial and industrial capital, later turn into centers of finance capital, and then collapse?

If so, then the question is of shifting hegemonies to East Asia, and whether (as Wallerstein for instance has recently been predicting) the US will gradually shift into the role of military enforcer for East Asian capital, provoking a realignment between Russia and the EU. Or, in fact, if all bets are off because the whole system is about to shift since, as Wallerstein also suggests, we are entering into an even more profound, 500-year cycle shift in the nature of the world-system itself?

Are we dealing with a global movement, as some autonomists (for example, the Midnight Notes collective) propose, of waves of popular struggle, as capitalism reaches a point of saturation and collapse — a crisis of inclusion as it were?

According to this version, the period from 1945 to perhaps 1975 was marked by a tacit deal with elements of the North Atlantic male working class, who were offered guaranteed good jobs and social security in exchange for political loyalty. The problem for capital was that more and more people demanded in on the deal: people in the Third World, excluded minorities in the North, and, finally, women. At this point the system broke, the oil shock and recession of the ’70s became a way of declaring that all deals were off: such groups could have political rights but these would no longer have any economic consequences.

Then, the argument goes, a new cycle began in which workers tried — or were encouraged — to buy into capitalism itself, whether in the form of micro-credit, stock options, mortgage refinancing, or 401ks. It’s this movement that seems to have hit its limit now, since, contrary to much heady rhetoric, capitalism is not and can never be a democratic system that provides equal opportunities to everyone, and the moment there’s a serious attempt to include the bulk of the population even in one country (the US) into the deal, the whole thing collapses into energy crisis and global recession all over again.

None of these are necessarily mutually exclusive but they have very different strategic implications. Much rests on which factor one happens to decide is the driving force: the internal dynamics of capitalism, the rise and fall of empires, the challenge of popular resistance? But when it comes to reading the rhythms in this way, the current moment still throws up unusual difficulties. There is a widespread sense that we are heading towards some kind of fundamental rupture, that old rhythms can no longer be counted on to repeat themselves, that we might be entering a new sort of time. Wallerstein says so much explicitly: if everything were going the way it generally has tended to go, for the last 500 years, East Asia would emerge as the new center of capitalist dominance. Problem is we may be coming to the end of a 500 year cycle and moving into a world that works on entirely different principles (subtext: capitalism itself may be coming to an end). In which case, who knows? Similarly, cycles of militarism cannot continue in the same form in a world where major military powers are capable of extinguishing all life on earth, with all-out war between them therefore impossible. Then there’s the factor of imminent ecological catastrophe.

One could make the argument, of course, that history is such that we always feel we’re at the edge of something. It’s always a crisis, there’s no particular reason to assume that this time it’s true. Historically, it has been a peculiar feature of capitalism that it seems to feel the need to constantly throw up spectres of its own demise. For most of the 19th century, and well into the 20th, most capitalists operated under the very strong suspicion that they might shortly end up hanging from trees — or, if they weren’t going to be strung up in an apocalyptic Socialist Revolution, witness some similar apocalyptic collapse into degenerate barbarism. One of the most disturbing features of capitalism, in fact, is not just that it constantly generates apocalyptic fantasies, but that it actually produces the physical means to make apocalyptic fantasies come true. For example, in the ’50s, once the destruction of capitalism from within could no longer be plausibly imagined, along came the spectre of nuclear war. In this case, the bombs were quite real. And once the prospect of anyone using those bombs (at least in such numbers as to destroy the planet) became increasingly implausible, with the end of the Cold War, we were suddenly greeted by the prospect of global warming.

It would be interesting to reflect at length on capitalism and its time horizons: what is it about this economic system that it seems to want to wipe out the prospect of its own eternity? On the one hand, capitalism being based on a logic of perpetual growth, one might argue that it is, by definition, not eternal, and can only recognise itself as such. But at other times those who embrace capitalism seem to want to think of it as having been around forever, or at least 5 thousand years, and stubbornly insist it will continue to exist 5 thousand years into the future. At yet other times it seems like a historical blip, an insanely powerful engine of accumulation that exploded around 1500, or maybe 1750, which couldn’t possibly be maintained without some sort of apocalyptic collapse. Perhaps the apparent tangle of contradictions is the result of a need to balance the short term perspectives needed by short term profit-seekers, managers, and CEOs, with the broader strategic perspectives of those actually running the system, which are of necessity more political. The result is a clash of narratives. Or maybe it’s the fact that whenever capitalism does see itself as eternal, it tends to lead to a spiraling of debt. Actually, the relations between debt bubbles and apocalypse are complicated and would be difficult (though fascinating) to disentangle, but I would suggest this much. The financialisation of capital has lead to a situation where something like 97 to 98 percent of the money in the total ‘economy’ of wealthy countries like the US or UK is debt. That is to say, it is money whose value rests not on something that actually exists in the present (bauxite, sculptures, peaches, software), but something that might exist at some point in the future. ‘Abstract’ money is not an idea, it’s a promise — a promise of something concrete that will exist at some time in the future, future profits extracted from future resources, future labour of miners, artists, fruit-pickers, web designers, not yet born. At the point where the imaginary future economy is 50 to 100 times larger than the current ‘real’ one, something has got to give. But the bursting of bubbles often leaves no future to imagine at all, except of catastrophe, because the creation of bubbles is made possible by the destruction of any ability to imagine alternative futures. It’s only once one cannot imagine that we are moving towards any sort of new future society, that the world will never be fundamentally different, that there’s nothing left to imagine but more and more future money.

It might be interesting, as I say, to try to disentangle the shifting historical relations between war, the development of ‘security’ apparatuses designed above all to strangle dreams of alternative futures, speculative bubbles, class struggle, and history of the capitalist Future, which seems to veer back and forth between utopia and cataclysm. These are not, however, precisely the questions that I’m asking here. I want, rather, to look at questions of debt from a different, and much longer term, historical perspective. Doing so provides a picture much less bleak and depressing than one might think, since the history of debt is not only a history of slavery, oppression, and bitter social struggles — which, of course, it certainly is, since debt is surely the most effective means ever created for taking relations that are founded on violence and oppression and making them seem right and moral to all concerned — but also of credit, honour, trust, and mutual commitment. Debt has been for the last 5 thousand years the fulcrum not only of forms of oppression but of popular struggle. Debt crises are periodic and become the stuff of uprisings, mobilisations and revolutions, but also, as a result, reflections on what human beings actually do owe each other, on the moral basis of human society, and on the nature of time, labour, value, creativity and violence.

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/david-graeber-debt-the-first-five-thousand-years

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In a period of deep crisis, Stuart Hall argues in The Hard Road to Renewal, the capitalist class’ efforts to protect the status quo will not be simply defensive, but formative: reconfiguring political ideas and ideologies, organising new power bases and a new ‘historic bloc’, rebalancing the balance of forces. This is a creative, imaginative, contested process. ‘Every form of power not only excludes but produces something’, Hall writes. Politics, he argues, following Gramsci, is not a mirror that simply reflects the struggle between ‘already unified collective political identities’, but the terrain on which new forms of power might be constructed:

This is the production of politics – politics as production. This conception of politics is fundamentally contingent, fundamentally open-ended. There is no law of history which can predict what must inevitably be the outcome of a political struggle. Politics depends on the relations of forces at any particular moment. History is not waiting in the wings to catch up your mistakes into another ‘inevitable success.’ You lose because you lose because you lose.

What it means to pursue a hegemonising project, then, is to have the clarity to see what is actually happening in the present and to have the courage to respond not by reworking old and stale ideas to describe what is new and different, but with the ambition to struggle on many fronts and to seek to construct a new common sense, not simply advance a slew of policies – even if those policies are good, correct, and necessary.

This requires ideological contestation of the ideas already floating around in common sense: safety and security, freedom and choice, liberty and equality. The Left in the US is often uneasy engaging on these grounds. For those of us who came of age under the Bush administration and during the Global War on Terror, talk of ‘freedom’ and ‘liberty’ seems to veer too close to jingoism, while directives to embrace patriotic discourses in the style of the CPUSA (‘socialism is twenty-first century Americanism’) feel at best ridiculous and at worst offensive to those who remain oppressed by the very-much-still-existing American empire.

But perhaps the abolitionist tradition within American democracy – that is, the tradition of ‘abolition democracy’, by way of Davis and WEB Du Bois – offers us a way through: a language that draws upon historical memories that occupy pride of place in American common sense, even if they are often distorted by liberal revisionism. If, as Hall put it, ‘[d]emocracy is what working people have made it: neither more or less’, the abolitionist struggle for democracy and the struggle for communism are one and the same.

The hegemonising task of abolitionism is to meet and answer the people’s real fears with a politics of care, to redefine safety according to the needs of the exploited and oppressed. The analysis contained in the abolitionist slogan ‘Who keeps us safe? We keep us safe’ reveals the law-and-order state as illegitimate not only on account of its brutality but because it fails to provide the very thing any sovereign state must: the security of its people.

Again, all of these ideas must be contested. In A Critical Theory of Police Power, Mark Neocleous argues that security is ‘the supreme concept of bourgeois society.’ The regime of private property cannot be upheld without the ideology of security. ‘Far from being a spontaneous order of the kind found in liberal mythology, civil society is the security project par excellence’, he writes. ‘The demand for security is inevitably a demand for the greater exercise of state power.’

Well, maybe so. Abolitionism, then, does not simply make demands of the state but demands a different kind of state altogether....

Any credible attempt to redress the present political and social crisis will have to proceed from a democratic re-appropriation and socialist reorientation of all those key state levers that are essential for controlling and shaping economic reality."

- Brendan O'Connor, "The Ordinary is a Horror: Abolition, Hegemony, and the State." Salvage. January 28, 2023.

0 notes

Text

The Arab World Has Already Left Unipolarity and Hegemony Behind

— Ebrahim Hashem | March 21, 2024

Illustration: Chen Xia/Global Times

By launching the war of aggression against Iraq and enabling the subsequent calamitous "Arab Spring," some US policymakers and their Western peers thought that they were "present at the re-creation." They wishfully thought they were on the cusp of imposing "Sykes-Picot 2.0" on the Arab world to further divide the divided. However, they did not know that they were embarking on adventurism that would eventually backfire and dramatically erode the American and Western dominance in the Arab region and the world. Their strategically fatal mistakes of the early years of this century are now catching up with them. To say that the Western influence in the Arab region and the world is currently at its lowest point since WWI is an understatement.

The Arab world is already in the post-US and post-West era. The US will never again have the hegemonic position it once enjoyed in the region during the 1991-2013 period. Similarly, the European powers will never again have the dominant role they once had in the region during the 1914-1945 period. The two periods represent a fleeting moment and an aberration in the long Arab history.

The Arabs are transparently demonstrating their embrace of multi-alignment and actively facilitating global multipolarity. They have no qualms about joining various organizations and initiatives such as BRICS, China-proposed Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC). The Arabs are not ideological in their decisions to join groupings and projects. They are keen on being in partnerships and associations that serve their strategic objectives. The Arabs are among the key contributors to the ongoing global power diffusion. By unlocking their potential and diversifying their strategic partnerships, the Arabs are helping accelerate the transition to a new world order.

While the Emiratis, Saudis and Egyptians were aware of the impact of their BRICS membership on regional and global politics, their primary motivation for joining the grouping was geoeconomics. The Arabs do not want to miss out on the opportunity to be part of the next wave of globalization. BRICS is increasingly seen as the emerging powerful force that will drive the new economic globalization in the remaining decades of the 21st century. The grouping is already economically and demographically larger than the G7. Even when excluding the recent expansion, BRICS accounts for 32 percent of the global GDP (PPP) and 40 percent of the world population - compared to the G7's 30 percent and 10 percent, respectively. China and India alone contribute around 50 percent to world economic growth.

The Arab world's top two trading partners are BRICS members, namely China and India. Arab trade with China and India exceeds $400 billion and $240 billion, respectively. The Arab world, as a trading bloc, is India's largest partner and one of China's most important partners. The UAE and Saudi Arabia, for example, send more than a third of their crude oil exports to China and India, while the Arab world provides around 45 percent of China's crude imports and 60 percent of India's. With so much synergy between the Arabs and the two Asian giants, trade is only going to increase between the two sides in the coming decades.

Despite the devastating Iraq war and atrocious Arab Spring events, the Arabs have recovered a lot of self-confidence in the last decade. They are deeply aware of the potential of their region. They recognize that their strength should not be measured myopically based on the current phase of their development, but more correctly and strategically, it should be assessed based on their potential. Despite regional turbulence in the last two decades, the Arab world is still doing relatively well.

The combined Arab GDP (PPP) is about $8 trillion. The size of the combined Gulf Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) alone is $4 trillion, a considerable portion of which is being wisely and progressively deployed to drive regional economic development and integration. According to a recent study, Saudi Arabia is going to be among the top 13 economies by 2050, while Egypt is expected to be one of the top seven economies by 2075. Arab land contains around 40 percent and 25 percent of the world's proven oil and gas reserves, correspondingly. The Arab population has reached more than 470 million, exceeding that of the EU, and more than 60 percent of Arab inhabitants are under the age of 30. If harnessed appropriately, the growing Arab population can be a major boon with massive demographic dividends for the region and the world.

The Arabs have made a strategic decision to deescalate tensions and address regional issues through peaceful political means. They do not want to squander their precious resources on endless and unnecessary conflicts; they want to use their abundant competitive and comparative advantages for economic and social development. Although most of the world sees profitable opportunities in the Arabs' strengthening regional and global position, some in the West mistakenly view it as a threat. They erroneously believe that to achieve global hegemony, they should subordinate Arab interests to Western ambitions for dominance - the basis of which the Carter doctrine and Reagan Corollary were created in the early 1980s. However, the Arabs refuse to engage with foreign countries based on self-proclaimed hegemonist doctrines and reductionist frameworks, especially those that ignore the interests of the Arab world.

In the Arab region, people are mindful of the current intensifying great power rivalry. They do not want their region to become a battleground for power struggles. They view China's economic development positively. They accept and celebrate the fact that China is re-emerging not only as a major power in Asia, but as a great power in the world. They see huge economic and trade partnership opportunities in China's expanding growth and development. Therefore, some US officials' demands and expectations that the Arabs restrict relations with the Chinese are not only unrealistic and presumptuous, but also unacceptable. The region has changed, the world has changed, and therefore the old, outdated dogmas of a past era should also change.

The Arabs have already left unipolarity and hegemony behind. They are now in charge of their own destiny. They are busy building their future based on a new paradigm that focuses mainly on indigenous capacity building, diverse strategic partnerships and comprehensive regional development and integration.

Ebrahim Hashem

— 2022 AsiaGlobal Fellow, Asia Global Institute, The University of Hong Kong! Ebrahim Hashem is a China-based strategist, consultant and scholar interested in the global economy, the world order, and Arab-China relations. He was a 2022 AsiaGlobal Fellow at the Asia Global Institute of The University of Hong Kong. He has been watching China’s rise since 2011 when he managed a strategic project related to China’s 12th Five-Year-Plan for the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). He has worked as a public-policy and strategy adviser to the chairman of the Abu Dhabi Executive Office and headed the long-term strategy division of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC). He advises various organizations on long-term strategies and Arab-China relations. He holds three master’s degrees in engineering science, business administration and public administration.

— The Author is Former Adviser to the Chairman of the Abu Dhabi Executive Office, an authority responsible for Abu Dhabi's long-term strategies, and Former Head of the Strategy Division of Abu Dhabi National Oil Company. He is currently a Visiting Scholar at the Asia Global Institute of the University of Hong Kong.

0 notes

Text

A GLOSSARY OF LEFTIST DISCOURSE

Introduction and disclaimer

I thought it would be useful to have a point of reference for terminology we encounter often, which may result in miscommunication or misunderstanding. This list is imperfect, but it will hopefully be useful as a starting point to explain to ourselves or others things we may not have fully understood or internalised. I do not claim to be an authority on these concepts, but I would hope that this post can be used as a tool to co-educate, rather than as an arena in which to attack or argue.

Paix entre nous, guerre aux tyrans! Solidarity forever, comrades.

***

Ancap (noun; adjective; slang)

Anarcho-capitalist. A branch of capitalist thought that advocates deregulation of the capitalist economy so much as to desire the means to privately exploit labour unencumbered by even state controls. Functionally the pursuit of corporate havens for slave labour.

Ancom (noun; adjective; slang)

Anarcho-communist. A branch of communism that embraces the anarchist rejection of state authority on the grounds that statehood is inherently abusive. Characterised by devolution to grassroots organisation and decentralisation, as opposed to outright eschewal of infrastructure.

Bourgeois (noun; plural bourgeoisie; adjective, bourgeois)

Traditionally, the socio-economic class who have recourse to profit from the labour of others (proletariat). Characterised by white-collar work, education, property or business ownership, some degree of upward mobility, though these qualifiers have arguably become increasingly complicated in the 21st Century with even many bourgeoisie being themselves subject to wage-slavery.

Capital (noun)

The material position of wealth, privilege, political-economic influence, and the power to profit from the labour of others (those others being proletariat). Frequently expanded to refer to the actual people who occupy this role (e.g. Jeff Bezos, Boris Johnson, Ellen Degeneres), but strictly speaking refers to the position itself.

Capitalism (noun)

The political-economic system which relies on the perpetual exploitation of disenfranchised classes’ (proletariat) labour in order that enfranchised classes (bourgeoisie) are able to both profit therefrom and retain monopoly on the means of production. Characterised by economic inequality, privatisation, wealth accumulation, indefinite and unsustainable growth.

Capitalist (noun, plural capitalists; adjective)

The class of bourgeoisie who possess the power to employ and exploit others. Strictly speaking, this only includes those with enough control over the means of production as to actively exclude others recourse thereto and thus make them reliant on wages.

Colonialism (noun; adjective, colonial)

The political-economic process of annexing foreign territory as a means of profit. Historically, this derives from feudalist military-expansionism, but was in many ways central to the advent of the modern era and the spread of capitalism globally.

Communism (noun; adjective, communist)

A political ideology and system of governance in which the proletariat possess the means of production, and thus the needs of each is provided by the association of workers. Characterised by unilaterally socialised services, public ownership of all resources, total eschewal of liquid economics.

Also: communist (noun, plural communists): subscriber to the above.

Cultural imperialism (noun)

An exercise of systemic abuse perpetrated through popular depictions (e.g. in media) rather than material political means, whereby it is presumed that (primarily) Western/European cultural norms are superior to others.

Decentralise (verb; adjective, decentralised; noun, decentralisation)

To deconstruct or cede authority from a single, primary position, resituating it at a local level, empowering regional autonomy. This devolution can take many forms, such as geographic (e.g. local councils, county authorities), cultural/ethnic (tribal bands, minority representation associations), or professional/disciplinary (workers’ councils, unions, guilds).

Decolonise (verb; noun, decolonisation; adjective, decolonial)

To dismantle colonial infrastructure. This usually refers to ceding (stolen) land rights back to indigenous populations, may include forming new sovereign governments, and essentially never involves forced migration.

Direct action (noun)

The active pursuit of (usually proletarian or leftist) aims through practical means, such as squatting, blockading, or guerilla gardening, rather than via bureaucracy, democracy, or appeal to state representatives which serve as a buffer between the alienated masses and our due, up to and including the forcible seizure of the means of production.

Fascism (noun; adjective, fascist)

A political system of authoritarian control over populations, particularly with tiered citizenship denying basic human rights to specific (especially ethnic) groups. Characterised by forced seizure of government, subversion of democracy, suppression and criminalisation of opposition, targeted ethnic violence/extermination, policies of eugenics, usually with overtures to nationalist supremacy and military conquest.

Feudalism (noun; adjective, feudalist)

The political-economic system which relies on miltary-expansionism and hierarchical control of land and resources, with a unique class system involving military service and nobility which has become largely obsolete. Generally held to be relegated to history, but directly leading to the advent of colonialism and capitalism.

Hegemony (noun; adjective, hegemonic)

A social condition which becomes so pervasive and normalised that any alternative comes to be seen as impossible, generally engineered by the ruling class through simultaneous measures of force and consent in order to pacify underclasses.

Imperialism (noun; adjective, imperialist)

A political process of ruling over people and especially other nations from a centralised control structure. This is often achieved through military occupation, but frequently takes the form of legislation or even corruption of local governance. ‘The highest stage of capitalism’.

Imperial-colonial (adjective; noun, imperial-colonialism)

Pertaining to the form of colonialism in which a region or territory is ruled by an absentee, centralised government, usually resulting in resources being exported from colonies to the centre/metropole for the profit and privilege of the ruling class to the exclusion of indigenous populations.

Internationalist (adjective; noun, internationalism)

Pertaining to policy which prioritises mutual aid and cooperation at a state level while maintaining regional autonomy. A central premise of Lenin’s Soviet strategy to unite proletariat globally.

Liberal (adjective; noun)

Socio-political ideology espousing capitalism as the best means to emancipate disenfranchised classes from their evident oppression, prioritising reform of exploitative systems and defending against leftist movements to fully dismantle them.

Lumpenproletariat (noun, plural same; adjective)

The lowest socio-economic class, often referring to those forced to beg or engage in criminal activity to meet needs. Marx and Engels contrasted this group with the proletariat as being impossible to mobilise via class consciousness, while Frantz Fanon and Fred Hampton viewed the lumpenproletariat as vital to anti-capitalist and especially decolonial action.

Marxism (noun)

A very wide body of theory and its associated ideology, subscribing to Marx’s principles of mobilisation through class consciousness, bottom-up revolution, and active destruction of hierarchical structures, classically with an emphasis on phenomenological inevitability.

Marxism-Leninism (noun; adjective, Marxist-Leninist)

The branch of Marxist theory developed by Lenin, adopted by the Soviet Union and most communist states since as official policy. Significantly espouses a ‘vanguard party’ to seize the means of production on behalf of the proletariat. Characterised by pragmatic (revolutionary) transition from capitalism, internationalist anti-imperialism, socialist democracy.

Marxist-feminist (noun; adjective)

A branch of feminist theory identifying capitalism as the ultimate source of (at least contemporary) patriarchal oppression, generally emphasising intersectionality, class consciousness, and solidarity, and standing in direct contrast to liberal feminism.

The means of production (noun)

The material components required to produce goods, such as tools, facilities, and raw materials. A basic premise underlying Marxist analysis is the empirical truth that proletariat are fully able to self-manage, given direct access to these components, and bourgeoisie therefore have no function but to control, exploit, and alienate.

Nationalise (verb)

To legislate against private ownership of a given resource and resituate said resource in state apparatus. A central tenet of socialism and communism is certain resources being publicly/state owned or controlled, and most capitalist societies also feature state control of certain resources. Sometimes synonymous with ‘socialise’.

Nationalism (noun; adjective, nationalist)

The pursuit of the interests of a specific national identity over others, usually including targeted violence, the real threat of exclusion and expulsion, propagandised rhetoric of ‘true’ members of said national identity, dangerous dogwhistles. Many minority nationalist movements (e.g. Kurdish, Basque, Iroquois) relate more to anti-colonial resistance, and Leninist internationalism supports these, but only as long as the relevant group remains oppressed.

Neo-colonial (adjective; noun, neo-colonialism)

Pertaining to a more recent practice whereby an economic power annexes foreign territory without explicitly controlling or occupying it, usually through corporate monopoly or land seizure, but generally includes political engineering of local governing bodies.

Petite bourgeois (noun; adjective)

Those bourgeoisie who have not got recourse to profit or significant wealth accumulation, but nevertheless rely on the labour of others (proletariat). Often small business owners or lower management, with limited (vocational) education, generally alienated from the means of production yet in a position to allocate resources to employees under them.

Praxis (noun)

The synthesis of theory and practice; practical activity directly informed by and in keeping with theoretical principles.

Proletariat (noun, plural same; adjective proletarian)

Traditionally, the socio-economic class whose only source of meeting needs is through (selling) labour. Characterised by blue-collar work, manual/’unskilled’ labour, lack of formal education, lack of property, alienation from the means of production (under capitalism). A large amount of leftist theory relates to the liberation of the proletariat and their claiming the means of production, and their right to self-determination.

Settler-colonial (adjective; noun, settler-colonialism)

The form of colonialism in which colonisers fully occupy and establish centralised governmental infrastructure on (stolen) land. Characterised by forcibly displaced indigenous populations, erasure of indigenous people and culture, legislation around indigenous status forming a tiered system of citizenship, nationalist propaganda.

Socialism (noun; adjective, socialist)

Political-economic system of publicly provided infrastructural support (of e.g. healthcare, education, housing, food). Often used interchangeably with ‘communism’, but differs in maintaining private property and potentially liquid economics. For this reason, Lenin viewed it as an interstitial condition between capitalism and full communism.

Also: socialist (noun, plural socialists): subscriber to the above.

Subaltern (adjective; noun)

The class most fully removed from the centralised position of privilege, without recourse to even basic infrastructural support, usually, though not exclusively, in imperial-colonial contexts. In many ways overlapping with lumpenproletariat, the term is more likely to refer to rural Indians than homeless Londoners.

Tankie (noun; adjective; slang)

Traditionally, those British communists who endorsed the Soviet military suppression of the Hungarian and Czech revolutions (of 1956 and 1968, respectively), the term has come to be used for any advocates or apologists of authoritarian state communism.

Third world (noun; adjective)

Traditionally, those countries or regions which were neither aligned with the capitalist West or the communist Eastern Bloc, but tertiary and therefore the more disenfranchised, the term has been resignified by global capitalist hegemony, referring to ‘developing’ nations which fall outside of exploitable markets (in part due to confusion with Mao Zedong’s ‘Three Worlds Theory’).

686 notes

·

View notes

Photo

LEK BORJA RENEWS FILIPINO HISTORY THROUGH ART

BY PRECIOUS RINGOR

Asian Pasifika Arts Collective New Outlooks Blog

April 2, 2021

http://ow.ly/fEby50FlQWZ

Editor’s Note: Precious Ringor brings us a second artist profile, this time of Filipino American interdisciplinary artist and poet Lek Borja, whose work is an attempt to track the continuous colonization across time, first within the Philippines from Spain and the United States, through present day America and trying to give voice to Filipino life against a white hegemony. Precious displays how Lek crosses borders of cultural stereotypes, seeking to expand the visions placed on Filipinos by other oppressive powers, and inserting her culture in art spaces where they are new and unfamiliar, but for the community, reminders of home.

Header Image: “Heritage at the Threshold” by Timothy Singratsomboune | Digital photography collage, 5400 x 4050 px, 2021.

Getting to know someone virtually is one of the sad realities we’ve had to face because of COVID-19 regulations. It’s both a blessing and a curse—we’ve become a global village, but at the same time we’ve all had more eye and back problems from sitting around and zooming this past year.

A zoom call and an hour was all I had to get to know Lek Vercauteren Borja, a Filipino American interdisciplinary artist and poet widely known for her thought-provoking work into the Asian diaspora. Chatting with Lek didn’t feel like a job though; time flies fast when you’re having fun.

One of the things I noted was Lek’s warm and friendly nature. Most of the time, it’s uncommon for an interviewee to ask questions about the interviewer. Lek unabashedly admitted that she did a bit of ‘stalking’ before we hopped on Zoom, “I like to know about the person I’m talking with, even before the interview starts.”

Lek started in poetry. Armed with a love for Shakespeare, she pursued a dual concentration in Art and Creative Writing at Antioch University. It was there that she first fell in love with art history and sculpture. During that time, her first chapbook, Android, was published by Plan B Press. She took this as a sign to continue pursuing a career in arts.

As an artist, she admits that’s where she gets inspiration from, “I want to talk about the history of Filipinos, the invisible stories. Growing up in the Philippines and studying there, I realized there was a lot missing in our history books. It seemed as if it were written from a western perspective.” She reminded me so much of the Philippines, of home. Because of our similar upbringing, I immediately understood her search for truth.

The themes of home and longing, of memory and the present, and of giving Filipino lives new voices, carry across her work, and no more palpably than her piece Evolution of the Aswang Myth, what she calls “seed and the origin” to all her current works. Lek says “Without it, I wouldn’t be thinking about art, the way I’m making now.” This 8 x 8 feet painting explores the origins of the aswang or manananggal, a Filipino mythical creature typically depicted as a woman feared for its penchant for eating infants and unborn fetuses during the night. Interestingly, the aswang was also a word ascribed to the Filipina women who went against the forced religious conversion by Spanish friars during their colonization of the Philippines.

March 2021 marked 500 years since Spanish ships first arrived on the shores of the Philippines.

Since then, our country fought hard for liberation, first from Spain and then from the United States of America. In retrospect, it hasn’t been long since the Philippines became an independent nation. Today, we are striving to find our voice amidst the imperialistic erasure we’ve endured.

As Lek puts it, “What propelled me to tell these stories is the feeling that I had no voice. For one, I didn’t speak English well so I couldn’t really talk about what I was going through or how I felt. That’s why a lot of my work now focuses on bringing my experiences of living in the Philippines at the forefront and seeing how that’s connected to bigger conversations and narratives around us.”

Currently, Lek’s work called Anak (My Child) is being featured in the gallery at Towson University’s Asian Arts & Culture Center.

View Anak (My Child) Exhibit: https://towson.edu/anak

Besides online exhibitions and virtual galleries, Lek is also conducting several workshops in Baltimore’s upcoming Asia North Festival. These workshops are a good model for Lek’s philosophy in making art out of personal histories. Whether it’s experiences of displacement or change, she points out that everyone’s story matters and there will always be a community of people who can empathize with that.

“I think it’s really important for our stories to be brought to light in the larger narrative. They think by calling us model minority, our problems can easily be brushed aside” I lamented the steady rise of xenophobic crimes these past few months.

“I agree, it’s a really complex issue” Lek adds, “Why are we so silent? Why do we stand in the shadows? I’ll probably look for an answer my entire life. It’s hard to talk about our struggles and it’s not easy to have conversations about the past. There’s a culture of silence that’s been normalized and it’s perpetuated even in our own homes. But that’s part of the work I do, bringing everything from the past into the forefront so we can have deeper conversations about it.”

Speaking of the past, Lek’s introduction to the arts started in Tarlac, a city located north of the Philippines. Besides being known as the most multicultural province, the city is home to numerous sugar and rice plantations. “The population of our barrio was probably less than 1,000. Our family had a farm as well as a sugar-cane and rice field plantation. My inang [grandmother] also worked in the market as a butcher. It was a pretty simple country lifestyle but my childhood was amazing.”

Life in the country has been instrumental to Lek’s artistry. “The memory of the landscape and of the community is an extension of my art,” Lek explains. As a young girl, her biggest inspiration comes from her grandfather who, like herself, was also an artist. Lek would copy his drawings and eventually create drawings of her own. Recently, Lek has started to incorporate banana leaves into her work. Banana leaves are incredibly important to Filipino culture as it is used for cooking and traditional homebuilding.

“Sounds like you had to find your own path, coming here at such a young age and experiencing culture shock. America is very different from the Philippines!” I quipped.

“It was snowing where I first came here!” she exclaimed, thinking back to her initial introduction of America. “It was November when we landed in New York, it was freezing. I remember our families bundling us in huge warm winter coats before wecould even say hello. It was definitely a huge shock.”

I laugh, thinking back to when I first arrived in California ten years ago. Silly to think I was already freezing in sunny temperatures when she had to endure piles of snow. “Do you think you’ve had to change yourself in order to adjust to that culture shock?”

“For a long time I really didn’t know who I was,” Lek admits. “When I was younger, the school I went to was predominantly white. What I thought about how I should present myself came from that image. I dyed my hair blond and put on blue colored contacts to fit in. It was a lot of assimilation and cultural erasure. I started talking less Tagalog and less Ilocano. But art has really helped me find myself. It made me think more deeply about who I really was and what was important to me on an authentic level.”

Halfway through our conversation, we slowly realized just how similar we were. From migrating at the age of ten to living twenty miles apart in the same city. It was also in chatting that Lek found out I spoke Tagalog fluently, one thing she regrets losing unexpectedly. As it is my first language, Lek asked me to speak it instead. Once again, her warm nature bled through the Zoom interview; I found it refreshing since hardly anyone thinks about the interviewer’s comfort.

Unsurprisingly, community building is important to Lek. Before working, she likes to ask herself the following questions, ‘How is what I’m doing connected to my family and everyone in the Filipino community? How can I better serve my community?’ One of the main reasons she moved to L.A. is to network with other Filipino artists.

“A few years ago, I showed my art alongside a group of all Filipino artists at Avenue 50 Studio gallery for an exhibition that Nica Aquino and Anna Calubayan organized (also both Filipinas). It’s crazy because I’ve lived in and out [of L.A.] for over 10 years now and it was only in 2019 that I started to be part of that community. It’s probably the most fun I've had at an art show, I really felt at home.”

“I’d love to visit the studio’s galleries once it’s safer to go outside”

“Definitely! I’ll keep you updated on any gatherings” Lek pitched excitedly.

“And I'll bring you guys homemade ube cakes and puto pao!” I teasingly replied back.

As our call came to a close I couldn’t help but ask Lek if she had any advice to give to budding AAPI artists.

“I’ll echo what people who have supported me have said in the past: trust yourself and trust that you can make a difference. It’s hard to figure out who you want to be when [the world] has expectations and demands from you. We’re lucky to live in a time where there’s so many possibilities. Figure out what you want to do authentically and genuinely, and go for it.”

Lek continues on, “Personally, it took me a long time to find my voice. When I was in grad school, I had a lot of doubt in myself because most visiting artists and curators couldn’t understand my work. What made it all worth it were the moments that people got [my voice] right away.”

Getting to know Lek and learning about her commitment to showcasing invisible stories has been awe-inspiring; it made me proud to be a Filipino American artist. And in the wake of our hurting AAPI community, I believe it’s incredibly important, now more than ever, to highlight and support works of people like Lek. People who have had to fight for their voice in this world, who our youth could look up to and be inspired to become.

About the Author:

Precious Ringor is a Filipino-American singer/actress/writer residing in Los Angeles, CA. Ringor graduated from Cal State University, Fullerton with a degree in Human Communication Studies where her research is geared towards Asian American socio-cultural communication norms. Besides performing in various theatre shows and indie film sets, Ringor also works as a content contributor to Film Fest Magazine and Outspoken

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The History of Light and Shadow

At the end of Twilight Princess, Ganondorf delivers one of his most memorable lines, “The history of light and shadow will be written in blood.” He is not wrong. As the player has witnessed over the course of Link’s adventure, Hyrule is haunted by ruins and ghost towns, a mere shadow of what it once was. The landscape is filled with numerous sites of past violence and empty spaces visibly marked by decay and wasted potential.

When Zelda tells Link and Midna that “these dark times are the result of our deeds,” she is referring to specific historical acts of imperialistic aggression. Hyrule established hegemony over its outlying territories by crushing the rebellions against its advances, but the kingdom has suffered from cultural stagnation as a result. Without the dynamic diversity symbolized by Ganondorf, Hyrule finds itself in economic and political decline, isolated from any contact with the world beyond its shrinking borders.

As a representative of a marginalized group of people who have been attacked and driven from their homes, Ganondorf is a tangible manifestation of the horrors of imperialism. He must be defeated, but doing so does not address the underlying problems that have resulted in Hyrule’s decline. I therefore want to argue that Twilight Princess uses Ganondorf to deliver a subtle yet poignant protest against the discourses of empire reflected by the dualistic “light and shadow” rhetoric of heroism that has resulted in tragedy and regret.

In the era immediately preceding Ocarina of Time, the kingdom of Hyrule united multiple geographically proximate groups of people at the end of a devastating civil war. Ganondorf was the leader of the Gerudo, an ethnic minority that resisted Hyrule. After several years of fighting, Ganondorf was eventually captured and imprisoned. The Sages of Hyrule were unable to execute him, so they sealed him away by casting him into the Twilight Realm, a world of shadows that exists alongside Hyrule. The events of Twilight Princess are triggered an indefinite period of time later when Ganondorf manages to persuade Zant, a prince of the Twilight Realm, to stage an uprising against Midna, its legitimate ruler.

Guided by Midna, the player takes on role of the teenage hero Link in order to defeat Zant and Ganondorf and thereby save Hyrule with the aid of its crown princess, Zelda. Many (if not the majority) of players will be influenced by the broad archetypes reproduced in this heroic narrative to understand Link as “good” and Ganondorf as “evil.”

Throughout most of Twilight Princess, Ganondorf is characterized as a ruthless tribal warlord who attacked Hyrule because of his lust for power. As indicated by his monologues and gradual humanization over the course of the final battle, however, Ganondorf represents much more than simply an evil to be defeated. He is introduced to the player as a foolish man who became evil incarnate, and he does little more than scream in rage and pain when the player first sees him in a flashback. When he is allowed to speak for himself, however, he reveals himself to be highly intelligent with motivations that are not unsympathetic.

When Link finally confronts Ganondorf in the throne room of Hyrule Castle, he is sitting alone. The world he once knew is long gone, and all that remains to him is the intense emotion he has directed toward Hyrule, whose wealth and security he simultaneously covets and resents. Ganondorf has succeeded in conquering the kingdom, but his victory no longer has meaning, as his people have been killed, driven away, or assimilated.

As established in Ocarina of Time, the Gerudo historically maintained uneasy relations with the majority ethnicity of Hyrule. The views once espoused by the people in Hyrule concerning the Gerudo are reminiscent of Orientalist stylizations, in which the peoples of certain “non-Western” and therefore “uncivilized” nations are characterized as being either unintelligent animals incapable of governing themselves or decadent and weak and thus a prime target for colonization.

The villainization of Ganondorf and the Gerudo as deceitful and lawless thieves within Hyrule echoes contemporary postcolonial discourse, in which former colonial powers exhibit a longing for “the good old days” of expansive imperial hegemony. The British sociologist Paul Gilroy has termed this fabricated nostalgia “postcolonial melancholy,” a tonal atmosphere characterizing stories that are often haunted by the gothic figure of the postcolonial ghost. Ganondorf is a textbook example of a postcolonial ghost – a menacing supernatural figure who represents the frightening native traditions of the past that the supposedly enlightened colonizers attempted to “correct” but were prevented from eradicating completely.

In order for culturally odorless global capitalism to move forward, the ghosts of the colonial past must be laid to rest, regardless of whether they are symbolic narratives or actual human beings. Such narratives are not uncommon in the political discourse and popular narratives of Japan, which is still struggling to come to terms with its history of imperial violence on the Asian mainland. In essence, the demonization of Ganondorf reflects the historical and contemporary villainization of both specific and broadly defined groups in the real world, including entire nations of people who have been discursively positioned as “enemies.”

As a medium, video games require challenges for the player to overcome. Story-based games such as those in the Legend of Zelda series tend to be relentless in their construction of enemies whose unequivocally evil deeds propel the hero to action. In Twilight Princess, there are two primary categories of characters with whom the player can interact: NPCs who offer material assistance and advice on how the hero can proceed through the quest, and monsters who must be attacked and generally yield tangible rewards when defeated.

In other words, the fundamental elements of gameplay reflect a worldview built on the foundation of a battle of “us” versus “them,” which is given literal expression in the dichotomy between who cannot be attacked and who must be attacked in order to advance. Many players take it for granted that a game will present a class or race or species that deserves to be destroyed, and the lack of alternative options for interaction suggests that it is still somewhat radical to suggest that perhaps the player-character is not entirely justified in the demonization of people who don’t look or think like them.

Video games are adept at engendering a sense of subjectivity, meaning that one of their functions is to give the player a feeling of controlling their movement through the game while enacting their will via the actions of their character. At the end of Twilight Princess, however, Link must fight and defeat Ganondorf, no matter how much sympathy the player may feel for him.

The gameplay elements of Twilight Princess therefore perform abjection, the process by which we demarcate the boundaries of the whole and wholesome “self” by setting up a contrast against a fragmented and unclean “other.” As individuals, we employ this process to construct monsters that violate the sanctity of our bodies; and, as cultures, we employ this process to construct enemies that violate our sense of belonging to a shared identity.

The dualism of “the pure” and “the abject” functions to further erase the nuances and possibilities denied by the artificial designation of the characters in Twilight Princess as either “good” or “evil.” Ganondorf’s cultural barrier-crossing, his shifting physical form, his open physical and emotional wounds, and his occupation of the liminal spaces between one world and another place him squarely in the realm of the impure and abject. Both the story of Twilight Princess and the narrative functions of its gameplay demand that the abject ghosts of the empire be purified and expelled by cleansing Hyrule of the pollution of Ganondorf’s lingering malice.

By humanizing Ganondorf but then forcing the player to fight him anyway, Twilight Princess employs various tropes relating to the figure of the postcolonial ghost not to invoke unironic postcolonial melancholy, but rather to force the player to experience the violence of these tropes in a subjective and visceral way. Twilight Princess is therefore not so much a heroic legend of triumph over “darkness” as it is an elegiac legend of regret concerning past atrocities.

Link’s victory is bittersweet, and it is not presented as a triumph for him or for Hyrule. At the end of Twilight Princess, Princess Zelda barely looks at the young man who supposedly rescued her. Midna, whose people were once banished to the Twilight Realm for opposing Zelda’s ancestors, takes her leave of Link, shattering the gate between their worlds after she departs. Midna explains her decision by saying, “Light and shadow can’t mix, as we all know.”

As Link and Midna’s friendship throughout the game has demonstrated, light and shadow can indeed coexist. Midna does not explain why she would choose to destroy the Mirror of Twilight that connects the Twilight Realm to Hyrule, but it is significant that this occurs immediately after she has witnessed the fight between Link and Ganondorf. Perhaps the prolonged spectacle of Ganondorf’s death has convinced Midna that there is no room for “monsters” in Hyrule, and it may be that she fears that she and her people will always be seen as abject outsiders, just as Ganondorf and his people once were.

It’s not clear to whom the title of Twilight Princess refers, and it could easily designate Midna, who emerges from and returns to the shadowy Twilight Realm. The title could also apply to Princess Zelda, however, as the victory over the forces of evil at the end of the game does not necessarily reverse or alleviate her kingdom’s slow decline. Before the end credits roll, Zelda sends the hero back to his village and returns alone to her empty castle.

Despite the narrative arc of Link’s progressive competence as an adventurer, this element of sorrow has been present from the outset of the game. Unlike the other games in the Legend of Zelda series, Twilight Princess begins not with Link waking up in the morning, but with him returning home in the evening. The opening scene is suffused with the golden light of the setting sun, and the game’s first spoken line is delivered by Link’s mentor Rusl, who asks, “Tell me… Do you ever feel a strange sadness as dusk falls?” The player’s first few minutes with Twilight Princess thereby establish melancholy and lament as two of the major themes of the game. The people of Hyrule are entering the twilight of their civilization under the rule of an ineffectual monarchy that has not allowed its people to be revitalized by change and diversity.

The slow apocalypse suggested by the environment of Twilight Princess, such as eroded ruins and decaying ghost towns, is not presented with an opportunity for renewal along with Ganondorf’s defeat. The potential for energetic dynamism represented by Ganondorf has been violently denied in favor of cultural purity, and the severity of this loss is reflected in the somber tone of the game’s closing scenes. If Ganondorf cannot exist in Hyrule, neither can Midna – and perhaps neither can Link himself.

When Ganondorf speaks of a history written in blood, he is referring to the history that has been lost to Hyrule along with the bodies and voices of the people who have fallen in its imperialistic conflicts. Twilight Princess thereby uses the menacing yet tragic figure of Ganondorf to suggest that, if the lifeblood of the kingdom is to remain vital, its history must be able to accommodate more than a reductive dualism between “light” and “shadow.”

#Legend of Zelda#Twilight Princess#Ganondorf#Midna#Princess Zelda#and Link too#Twilight Princess gives me feelings#witness my tears#lord help me I'm back on my bullshit#Zelda meta

271 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Is This a Remake of the 1941 Hitler Stalin Great War?

If we step back from the details of daily headlines around the world and try to make sense of larger patterns, the dominant dynamic defining world geopolitics in the past three years or more is the appearance of a genuine irregular conflict between the two most formidable powers on the planet—The Peoples’ Republic of China and the United States of America. Increasingly it’s beginning to look as if some very dark global networks are orchestrating what looks to be an updated rerun of their 1939-1945 World War. Only this time the stakes are total, and aim at creation a universal global totalitarian system, what David Rockefeller once called a “one world government.” The powers that be periodically use war to gain major policy shifts.

On behalf of the Powers That Be (PTB), World War II was orchestrated by the circles of the City of London and of Wall Street to maneuver two great obstacles—Russia and Germany—to wage a war to the death against each other, in order that those Anglo-Saxon PTB could reorganize the world geopolitical chess board to their advantage. It largely succeeded, but for the small detail that after 1945, Wall Street and the Rockefeller brothers were determined that England play the junior partner to Washington. London and Washington then entered the period of their global domination known as the Cold War.

That Anglo-American global condominium ended, by design, in 1989 with the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the disintegration of the Soviet Union by 1991.

Around this time, with the onset of the Bill Clinton presidency in 1992, the next phase– financial and industrial globalization– was inaugurated. With that, began the hollowing out of the industrial base of not only the United States, but also of Germany and the EU. The cheap labor outsourcing enabled by the new WTO drove wages down and destroyed one industry after the next in the industrial West after the 1990s. It was a necessary step on the path to what G.H.W. Bush in 1990 called the New World Order. The next step would be destruction of national sovereignty everywhere. Here the USA was the major obstacle.

“A little help from our friends…”

For the PTB, who owe no allegiance to nations, only to their power which is across borders, the birth of the World Trade Organization and their bringing China in as a full member in 2001 was intended as the key next step. At that point the PTB facilitated in China the greatest industrial growth by any nation in history, possibly excepting Germany from 1871-1914 and USA after 1866. WTO membership allowed Western multinationals from Apple to Nike to KFC to Ford and VW to pour billions into China to make their products at dirt-cheap wage levels for re-export to the West.

One of the great mysteries of that China growth is the fact that China was allowed to become the “workshop of the world” after 2001, first in lower-skill industries such as textiles or toys, later in pharmaceuticals and most recently in electronics assembly and production. The mystery clears up when we look at the idea that the PTB and their financial houses, using China, want to weaken strong industrial powers, especially the United States, to push their global agenda. Brzezinski often wrote that the nation state was to be eliminated, as did his patron, David Rockefeller. By allowing China to become a rival to Washington in economy and increasingly in technology, they created the means to destroy the superpower hegemony of the US.

By the onset of the Presidency of Xi Jinping in 2012, China was an economic colossus second in weight only to the United States. Clearly this could never have happened–not under the eye of the same Anglo-American old families who launched the Opium Wars after 1840 to bring China to heel and open their economy to Western financial looting–unless the Anglo-Americans had wanted it.

The same British-owned bank involved in the China opium trade, Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank (HSBC), founded by a Scotsman, Thomas Sutherland in 1865 in the then-British colony of Hong Kong, today is the largest non-Chinese bank in Hong Kong. HSBC has become so well-connected to China in recent years that it has since 2011 had as Board member and Deputy HSBC Chairman, Laura Cha. Cha was formerly Vice Chairman of the China Securities Regulatory Commission, being the first person outside mainland China to join the Beijing Central Government of the People’s Republic of China at vice-ministerial rank. In other words the largest bank in the UK has a board member who was a member of the Chinese Communist Party and a China government official. China needed access to Western money and HSBC and other select banks such as JP MorganChase, Barclays, Goldman Sachs were clearly more than happy to assist.

“Socialism with Xi Jinping Characteristics…”

All told until 2012 when Xi took charge of the CCP in Beijing, China seemed to be willing to be a globalist “team player,” though with “Chinese characteristics.” However, in 2015 after little more than two years in office, Xi Jinping endorsed a comprehensive national industrial strategy, Made in China: 2025. China 2025 replaced an earlier Western globalist document that had been formulated with the World Bank and the USA, the China 2030 report under Robert Zoellick. That shift to a China strategy for global tech domination might well have triggered a decision by the globalist PTB that China could no longer be relied on to play by the rules of the globalists, but rather that the CCP under Xi were determined to make China the global leader in advanced industrial, AI and bio-technologies. A resurgent China nationalist global hegemony was not the idea of the New World Order gang.

China:2025 combined with Xi’s strong advocacy of the Belt Road Initiative for global infrastructure linking China by land and sea to all Eurasia and beyond, likely suggested to the globalists that the only solution to the prospect of their losing their power to a China global hegemon would ultimately be war, a war that would destroy both nationalist powers, USA AND China. This is my conclusion and there is much to suggest this is now taking place.

Tit for Tat

If so, it will most likely be far different from the military contest of World War II. The USA and most of the Western industrial economies have “conveniently” imposed the worst economic depression since the 1930’s as a bizarre response to an alleged virus originating in Wuhan and spreading to the world. Despite the fact that the death toll, even with vastly inflated statistics, is at the level of a severe annual influenza, the insistence of politicians and the corrupt WHO to impose draconian lockdown and economic disruption has crippled the remaining industrial base in the US and most of the EU.

The eruption of well-organized riots and vandalism under the banner of racial protests across the USA has brought America’s cities to a state in many cases of war zones resembling the cities of the 2013 Matt Damon and Jodie Foster film, Elysium. In this context, anti-Washington rhetoric from Beijing has taken on a sharp tone in their use of so-called “Wolf Diplomacy.”

Now after Washington closed the China Consulate in Houston and China the US Consulate in Chengdu, both sides have stepped up rhetoric. High tech companies are being banned in the US, military displays of force from the US in the South China Sea and waters near Taiwan are increasing tensions and rhetoric on both sides. The White House accuses the WHO of being an agent of Beijing, while China accuses the US of deliberately creating a deadly virus and bringing it to Wuhan. Chinese state media supports the explosion of violent protests across America under the banner of Black Lives Matter. Step-wise events are escalating dramatically. Many of the US self-styled Marxists leading the protests across US cities have ties to Beijing such as the Maoist-origin Revolutionary Communist Party, USA of Bob Avakian.

“Unrestricted Warfare”

Under these conditions, what kind of escalation is likely? In 1999 two colonels in the China PLA, Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui, published a book with the PLA Press titled Unrestricted Warfare. Qiao Liang was promoted to Major General in the PLA Air Force and became deputy secretary-general of the Council for National Security Policy Studies. The two updated their work in 2016. It gives a window on high-level China military strategy.

Reviewing published US military doctrine in the aftermath of the 1991 US Operation Desert Storm war against Iraq, the Chinese authors point out what they see as US over-dependence on brute military force and conventional military doctrine. They claim, “Observing, considering, and resolving problems from the point of view of technology is typical American thinking. Its advantages and disadvantages are both very apparent, just like the characters of Americans.” They add, “military threats are already often no longer the major factors affecting national security…these traditional factors are increasingly becoming more intertwined with grabbing resources, contending for markets, controlling capital, trade sanctions, and other economic factors, to the extent that they are even becoming secondary to these factors. They comprise a new pattern which threatens the political, economic and military security of a nation or nations… The two authors define the new form of warfare as, “encompassing the political, economic, diplomatic, cultural, and psychological spheres, in addition to the land, sea, air, space, and electronics spheres.”

They suggest China could use hacking into websites, targeting financial institutions, terrorism, using the media, and conducting urban warfare among the methods proposed. Recent revelations that Chinese entities pay millions in ad revenues to the New York Times and other mainstream USA media to voice China-positive views is one example. Similarly, maneuvering a Chinese national to head the US’ largest public pension fund, CalPERS, which poured billions into risky China stocks, or persuading the New York Stock Exchange to list dozens of China companies without requiring adherence to US accounting transparency increase US financial vulnerability are others.

This all suggests the form that a war between China and the US could take. It can be termed asymmetrical warfare or unrestricted war, where nothing that disrupts the enemy is off limits. Qiao has that, “the first rule of unrestricted warfare is that there are no rules, with nothing forbidden.” There are no Geneva Conventions.

The two Beijing authors add this irregular warfare could include assaults on the political security, economic security, cultural security, and information security of the nation. The dependence of the US economy on China supply chains for everything from basic antibiotics to militarily-vital rare earth minerals is but one domain of vulnerability.

On its side, China is vulnerable to trade sanctions, financial disruption, bioterror attacks and oil embargoes to name a few. Some have suggested the recent locust plague and African Swine Fever devastation to China’s core food supplies, was not merely an act of nature. If not, then we are likely deep into an undeclared form of US-China unrestricted warfare. Could it be that the recent extreme floods along the China Yangtze River that threaten the giant Three Gorges Dam and have flooded Wuhan and other major China cities and devastated millions of acres of key cropland was not entirely seasonal?

A full unrestricted war of China and the USA would be more than a tragedy. It could be the end of civilization as we know it. Is this what characters such as Bill Gates or George Soros and their superiors are trying to bring about? Do they plan to introduce their draconian dystopian “Reset” on the ashes of such a conflict?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

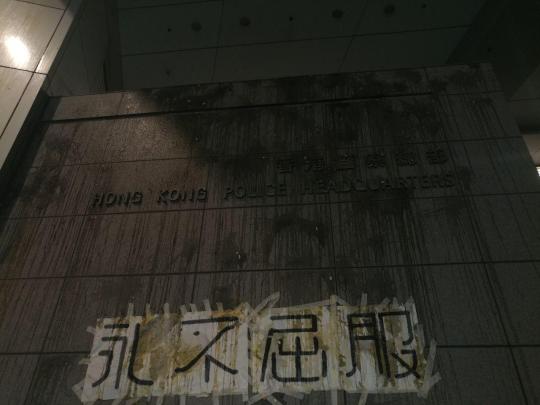

Hong Kong: Anarchists in the Resistance to the Extradition Bill An Interview

Since 1997, when it ceased to be the last major colonial holding of Great Britain, Hong Kong has been a part of the People’s Republic of China, while maintaining a distinct political and legal system. In February, an unpopular bill was introduced that would make it possible to extradite fugitives in Hong Kong to countries that the Hong Kong government has no existing extradition agreements with—including mainland China. On June 9, over a million people took the streets in protest; on June12, protesters engaged in pitched confrontations with police; on June 16, two million people participated in one of the biggest marches in the city’s history. The following interview with an anarchist collective in Hong Kong explores the context of this wave of unrest. Our correspondents draw on over a decade of experience in the previous social movements in an effort to come to terms with the motivations that drive the participants, and elaborate upon the new forms of organization and subjectivation that define this new sequence of struggle.

In the United States, the most recent popular struggles have cohered around resisting Donald Trump and the extreme right. In France, the Gilets Jaunes movement drew anarchists, leftists, and far-right nationalists into the streets against Macron’s centrist government and each other. In Hong Kong, we see a social movement against a state governed by the authoritarian left. What challenges do opponents of capitalism and the state face in this context? How can we outflank nationalists, neoliberals, and pacifists who seek to control and exploit our movements?

As China extends its reach, competing with the United States and European Union for global hegemony, it is important to experiment with models of resistance against the political model it represents, while taking care to prevent neoliberals and reactionaries from capitalizing on popular opposition to the authoritarian left. Anarchists in Hong Kong are uniquely positioned to comment on this.

The front façade of the Hong Kong Police headquarters in Wan Chai, covered in egg yolks on the evening of June 21. Hundreds of protesters sealed the entrance, demanding the unconditional release of every person that has been arrested in relation to the struggle thus far. The banner below reads “Never Surrender.” Photo by KWBB from Tak Cheong Lane Collective.

“The left” is institutionalized and ineffectual in Hong Kong. Generally, the “scholarist” liberals and “citizenist” right-wingers have a chokehold over the narrative whenever protests break out, especially when mainland China is involved.