#as ways to control rhythm in prose and the impact of moments

Text

If our writing is to a degree the influence of what we have read, I'd like to know particularly what fucking authors I read that rubbed off on me that I write the particular way I do.

I Know to a degree Edgar Allen Poe has got to be why I do the particular emotional descriptions and specifically poetically rhythmic sentence choices. He did this thing of sentences breaking in places to feel like poetry almost, and I definitely picked that up at age 12 and never stopped.

But I also got into this specific habit of going not just biased pov third person (which plenty of authors I most enjoy tend to do), but also this sort of very thought-heavy biased pov where I don't tell the reader all thoughts but what I write is a hint to what's not said, and i write emotionality of the pov (again a lot like poe I know I picked up some word choice and sentence style from him) but it doesn't say it all it sort of makes a shape. I cannot figure out what writers I picked it up from. Maybe some fanfic writers I liked? I know at some point mid college, I swung from writing Really Minimalistic to enjoying going in DEEP into each scene to enjoy and savor it. And that's when those sections went from same style but curt, to very in depth and scenes got 5 pages long when they used to be 1 page. But I can't think at the moment of who writes like that.

Also, the emotional biased unreliable way I do description is something I can see I was doing all through High school, very early, so I picked that up from something I read probably soon after poe. Really early on.

#rant#i just. i wonder where the fuck i get it from??#if i knew then i coukd read something other than my own stuff when i need to shift baxk into it for writing lol#but also just out of curiousitys sake#i KNOW biased pov i picked up because Holly Black. Poe. Anne Rice. ALL use it.#and i picked up stuff from those 3 a lot. i picked up some frankly Too Much taste for unique peculiarities in writing from anne rice#as in i appreciate something feeling Distinct over somrthing feeling perfect/solidly executed. if its technivally perfect but#the same style as other stuff its less interestinf to me. i think its partly cause anne rice flips pov voice and then style to a distinct#degree when povs shift#then poe does the poetic rhythm even in prose. and i loved it when i noticed it.#and after that i always thought of sentence length and breaos#as ways to control rhythm in prose and the impact of moments#and i know absolutely i got that part from poe#but like. idk i write in this way where im. well its always character analysis#and its like i go into their pov into their thoughts. then put their thoughts on the page raw#and you still have to figure out between the lines theur truth they wont tell u or thenselves.#and its very imagery heavy. and maybe the character introspection is from anne rice? she does it to some degree#i know my genre preferences i got from holly blaxk#the instant i read Tithe and Valiant. fae political bullshit juxtaposed against new jersey mundane? i was like#this is IT THE PINNACLE. MY IDEAL FAVORITE

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Q&A: Fight Scene Length

Do you have any advice for scene length/impact? I’m realizing that if writing a three page play by play of a sword fight is hard, reading it must be even worse, so I’m trying o shorten it up without diminishing its importance or the impact it’s supposed to have.

Usually, the shorter the better. I’ve talked about this before, but different mediums lend themselves to different approaches to combat.

Film and games thrive on a longer, drawn out, format. In a film, each strike can carry individual drama because you’re getting the responses of the actors. Film can also thrive on spectacle, a visually exciting environment and engaging choreography can sell a fight that, on paper, is fairly dull.

Comics thrive on spectacle. It’s not about how long the fight is, it’s about being able to have dynamic moments that your artist can bring to life. If you have that, your fight can be one panel or it can comfortably go for pages. I haven’t pointed this out before, but in comics, as a writer, you really need an artist who fits what you’re trying to do. You’re equal parts of a team.

In prose, you want your fights to be as brief as necessary. Note: “As brief as necessary.” If it’s just a fight between two characters, that can be over in a couple paragraphs. Even if it’s part of a larger battle, that stuff can be pushed to the side for this individual fight. However, background elements can intrude, extending the fight. For example: If a fight is interrupted by other characters, and one chooses to break combat to escape, you could have a much longer encounter without resorting to a blow by blow.

You want to avoid a rhythm of repetition at all costs. RPGs can easily break down combat into round after round of, “I hit them with my axe,” and the sound of dice rolling. There’s nothing wrong with that in that format. The experience that sells that is three fold: First: You’re a participant. This isn’t something affecting a character you care about, it’s affecting your proxy in the story. Second: The outcome is not preordained, you’re still rolling dice. Third: It was never about the content to begin with, it’s the people you’re there with. So combat that gets repetitive isn’t a problem because it’s not the main event. This is not true in prose, and one of the most dangerous things about transposing combat from a game system into prose.

This may sound a little stupid but, each time your character acts they should be trying to achieve a goal. Yes, “harming my foe,” is a legitimate objective, but if they can’t do that directly, they shouldn’t resort to, “I’m going to repeat the same action a dozen times hoping for a different result.”

If your character is in a fight, they try to attack their opponent, and the attack is defended, they need a new approach.

There are a few things your experienced character should do that will help with this. First, they don’t start with direct attacks, their first goal should be to test their opponent’s defenses. So, they’ll start with probing attacks, looking for weaknesses in their foe’s defenses. They’ll be studying how their opponent moves. On the page, there’s a huge difference between a character simply attacking, and specifically trying to tease their opponent’s parry to get a look at it. Once they have a solid grasp of how their foe fights, then they’ll probably move in for the kill. This could be complicated by other events. This is the background, the environment, or even sustained injuries. This stuff is not safe, and minor miscalculations could result in your character being injured, which then becomes a complication they’ll need to deal with as the fight progresses. If your character can’t exploit their foe’s weaknesses, they’ll need to find a way to open them up. This could include attempting to wound in order to create a future opening, or forcing them into a disadvantageous position. Once they’ve taken control of the fight and gotten it to a position where they have a decisive advantage, then they’ll kill.

While your character is trying to take control of the fight, an experienced foe will be doing the same. Obviously, if only one character knows what they’re doing, it will seriously impact how all of this plays out, and the fight will be very one-sided. It’s entirely possible the veteran will simply disarm and kill the rookie.

Impact is a more complex concept. I think the simplest way to describe it is: Impact is determined by how quickly, and sharply, and scene goes wrong for the characters.

In a fight scene, you want to clean it up quickly because your readers will get bored. When you’re asking about impact, you need to it to resolve fast or the impact is lost. The scene needs to transition from, “thing are going well,” to, “everything’s fucked,” in as few words as possible.

For example: Let’s look at that template above. You start with your protagonist testing their foe’s defenses, finding an opening, and moving their foe to a position where they think they have the advantage. Their opponent is struggling to deal with their assault, and then when they’re about to press and kill them, their enemy lops off your protagonist’s sword arm and executes them.

The part where things are going well can be longer, but it needs to go wrong, roughly, that fast. You can also foreshadow this in a lot of ways. If you’ve established that their foe is a more skilled swordsman than you’re seeing in that fight, you’ve warned the audience that this will happen, but in the moment they’ll think your protagonist is just that awesome, or that the villain’s reputation was unearned. It’s only after the walls are painted in blood that they realize you realize your protagonist walked into a trap.

The second thing about impact is, your audience will acclimate very quickly. You can get away with a hard shift like this, maybe, once per story. If you’re reusing characters, you don’t get that back, you’ve already turned things sideways once. If you want to hit hard again, it needs to be completely different. In the example above, if you started by killing a protagonist, you’re not going to get that kind of impact with another death. You’ve already told your audience that you’re willing to go there, and doing it again isn’t going to surprise anyone.

Fight scenes need to be as short as necessary. Impact has to as fast and hard as possible.

There is no, “this number of words/pages,” for how long a fight should be, because the answer will be different. It depends on the specific scenario. It depends on your style as a writer. It depends on what you’re trying to accomplish. The only universal answer is that you don’t want to waste words in a fight scene.

-Starke

This blog is supported through Patreon. If you enjoy our content, please consider becoming a Patron. Every contribution helps keep us online, and writing. If you already are a Patron, thank you.

Q&A: Fight Scene Length was originally published on How to Fight Write.

446 notes

·

View notes

Photo

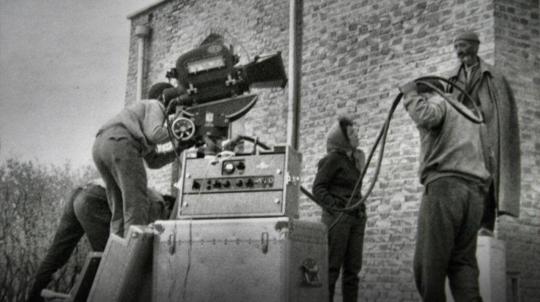

Sculpting in Time.

As the world inches into the future, we invited Justine Smith, author of the ‘100 Films to Watch to Expand your Horizons’ list, to look to the cinematic past to help us process the present.

It is said that the essential quality of cinema that distinguishes it from other arts is time. Music can be played at different tempos, and standing in a museum, we choose how many seconds or hours we stand before a great painting. A novel can be savored or sped through. Cinema, on the other hand, exists on a fixed timeline. While it can theoretically be experienced at double or half speeds, it is never intended to be seen as such. Cinema’s fundamental quality is experiencing time on someone else’s terms. As the great Andrei Tarkovsky said in describing his work as a filmmaker, he was “sculpting in time”.

The perception of time, however, is not universal. Our moods, our emotions, and our ideologies shape our relationship to it. Most Western audiences are further acclimated to Western cinema’s ebbs and flows, which similarly favor efficiency and invisibility. When we see a Hollywood film, we don’t want the story to stop. We want to be swept away and forget that we are all moving towards a mortal endpoint. Cinema, though, in its infinite possibilities, exists far beyond these parameters. It can challenge and enrich our vision of the world. If we open ourselves up, we can transfigure and transform our relationship to time itself.

When I first put together my 100 Films to Watch to Expand your Horizons list, I did it quite haphazardly. I imagined countries, filmmakers and experiences that I felt went under-appreciated in discussions of cinema’s potential. Intuitively, I went searching for corners of experience that expanded my own cinematic horizon. Some of these films are well-loved and seen by wide audiences; others are virtually unknown. It was often only after the fact that the myriad of intimate connections between the films came to light.

Manuel de Oliveira’s ‘Visit, or Memories and Confessions’ (2015).

“The only eternal moment is the present.” —Manoel de Oliveira

Released in 2015 but made in 1982, Visit, or Memories and Confessions is a reflection on life, cinema and oppression by Portuguese filmmaker Manoel de Oliveira. If we were to reflect on cinema’s history, few filmmakers have the breadth of experience and foresight as Oliveira. His first film was made in the silent era using a hand-cranked camera. By the time of his death at 106 years of age, he had made dozens of movies, including many in a digital format.

He made Visit, or Memories and Confessions in the shadow of the Portuguese dictatorship. While filming, he imagined he was in the twilight of his life. It revisited essential incidents in his history but also that of his country. It’s a film of reconciliation, violence and oppression, told tenderly in a home lost as a consequence of a vindictive dictatorship. Oliveira’s film, like his life, spanned time in a way that stretches perceptions. It’s a film without significant incident, about the peaceful pleasures and tragedies of daily life.

Elia Suleiman’s ‘The Time that Remains’ (2009).

What worlds have changed over the past one hundred years? The same breadth of perception, which often feels too seismic to tackle in traditional narrative cinema, was also explored in The Time that Remains. In a retelling of his family’s history, Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman also tells Israel’s story. It is a film of wry comparisons and Keatonesque comic patterns. As borders change and time passes, few things fundamentally change, except on a spiritual plane. What happens to people without an identity or a country? What damage does it do to their souls?

The question of time looms heavily in both Oliveira’s and Suleiman’s films. They are movies that contemplate centuries of experiences and explore how those stories are guarded, twisted and erased by the powerful.

Alanis Obomsawin’s ‘Incident at Restigouche’ (1984).

The echoes of history and attempts to break with old patterns often emerge in other anti-colonial and anti-imperialist films. They can be seen in Alanis Obomsawin’s vital and angry Incident at Restigouche, about an explosive, centuries-in-the-making 1981 conflict between Quebec provincial police and the First Nations people of the Restigouche reserve; In Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India, villagers must win a cricket match to free themselves from involuntary servitude; and in Daughters of the Dust, the languid pace of the Gullah culture is challenged by the promise and violence of the American mainland.

Time, more than just a tool for chronology, becomes in itself a tool for oppression. Those who control time maintain power. If we are to break with dominant histories, the rhythms of oppression must be broken and challenged.

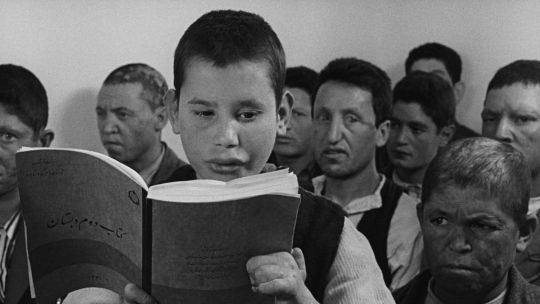

Forugh Farrokhzad’s ‘The House is Black’ (1963).

“The universe is pregnant with inertia and has given birth to time.” —Forugh Farrokhzad, The House is Black

Persian filmmaker and poet Forugh Farrokhzad made just one film before her untimely death in a car accident when she was 32. The House is Black is a short documentary about a Leper colony, which utilizes essay-esque prose taken from the Quaran, and Farrokhzad’s poetry. It is a film about people who are seen as invisible by society at large, cast away and hidden. The film reflects on beauty, sickness and reconciliation. How does one experience time when you’ve been ostracized and cut off from the larger world?

Barbara Loden’s landmark independent film Wanda asks a similar question. A solo mother who cycles from one abusive situation to the next exists outside of time and space. She is invisible. If we look at most American cinema, it might as well be propelled by people who take control over their destiny, but what of the people who are (un)willingly passive to the whims of society and other human beings? In her powerlessness, Wanda stands in for the invisible labor and sacrifices of so many other women. The ordinariness of Wanda’s life, the dusty and dirty environments she inhabits, rebound with significance. It is, however, not a victorious film. Instead, it is a profound portrait of loss and beauty. It’s the only film Barbara Loden ever made.

"If you don't want anything you won't have anything, and if you don't have anything, you're as good as dead." —Norman Dennis in Wanda

Barbara Loden’s ‘Wanda’ (1970).

In 2020, it seemed all we had was time. What seemed like an opportunity quickly became horrific. Time became a burden. We were reminded of our finite time on this Earth and all the hours spent commuting, working and surviving. The pandemic has had a seismic impact on our perceptions. In processing the ongoing crisis, we’ve transformed our relationship to the passage of time. We’ve altered the state of our reality.

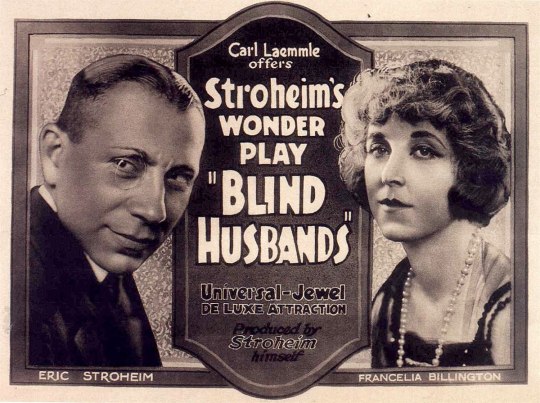

This new pandemic gaze offers us new perspectives on time and history. The oldest film on the list is Erich Von Stroheim’s Blind Husbands, released in 1919 during the grips of the Spanish flu. The film does not reference the event, but its sensuality and class conflicts speak to a world on the brink of seismic change. It is a movie about an Austrian military officer who seduces a surgeon’s wife. The men grapple with jealousy and violence on a literal mountaintop, fighting for survival in an increasingly mechanized society.

Poster for Erich Von Stroheim’s ‘Blind Husbands’ (1919).

To this day, Blind Husbands is shocking. It’s profoundly fetishistic and loaded with heavy sexual imagery. It’s a movie about touch and desire absent of love and affection. It speaks to aspects of current life that feel lost and impenetrable. It speaks to growing and changing social disparities as well. Surviving the modern world is more than just surviving the plague; it has to do with value compromises and shifting power dynamics.

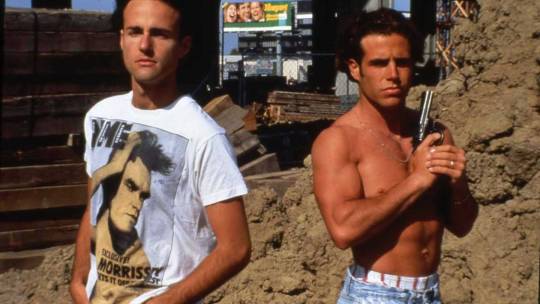

But, a pandemic is also about loss. Gregg Araki’s 1992 film The Living End explores the AIDS crisis from the inside out. Rebellious and angry, the film is about a gay hustler and a movie critic, both of whom have been diagnosed with the HIV virus. With characters who are cast out from society at large, gripped with a deadly and unknown fate, The Living End is apocalyptic—much like other Araki works from the 90s, such as The Doom Generation and Totally Fucked Up. It captures the deep sense of hopelessness of experiencing a pandemic while also belonging to a marginalized group. What is so radical about Araki’s cinema, though, is that it is also fun. It is a film that transcends mourning and becomes a lavish punk celebration. It is a film about survival, out of step with dominant ideology and histories.

Gregg Araki's ‘The Living End’ (1992).

The connections between Blind Husbands and The Living End bridge together to form common passions and changing perceptions. Both films are products of their time, at once part of distant histories but also uncomfortably prescient. More than films about a specific time and place, they are transformed by the time we live in now. To watch and connect with these movies in a pandemic means looking and living beyond the current moment.

While it seems like cinema might be facing an especially precarious future, it feels like the ideal art form to process what is happening right now. Caught in the vicious patterns of our own creation, giving ourselves up to the rhythms of someone else’s will might be a necessary form of healing, as well as an ongoing project in compassion. Time does not have to be a prison; it can be an agent for liberation.

Related content

100 Films to Watch to Expand Your Horizons

The Oxford History of World Cinema

1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die

The Great Unknown: High Rated Movies with Few Views

Follow Justine on Letterboxd

#justine smith#justine peres smith#world cinema#expand your horizons#gregg araki#manoel de oliveira#elia suleiman#julie dash#alanis obomsawin#Forugh Farrokhzad#barbara loden#erich von stroheim#mubi#criterion#criterion collection#letterboxd

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mosque of the Late Mohamed Abdulkhaliq Gargash

Mosque of the Late Mohamed Abdulkhaliq Gargash Dubai, UAE Religious Building Photos, Architecture

Mosque of the Late Mohamed Abdulkhaliq Gargash, Dubai

21 September 2021

Design: Dabbagh Architects

Location: Um Suqeim Road, Al Quoz, Dubai, UAE

Mosque of the Late Mohamed Abdulkhaliq Gargash in Dubai

• A contemporary place of worship quietly masterful in its use of form, materiality and controlled natural lighting to create a sense of calm and spiritual connection

• A pared down form that eschews traditional Islamic typology, with a design narrative to transition the worshipper from the outer everyday world to an inner spiritual experience

• One of the first mosques in the UAE to be designed by a female architect

Mosque of the Late Mohamed Abdulkhaliq Gargash News

Dubai, United Arab Emirates – Dabbagh Architects lead by Principal Architect and Founder, Sumaya Dabbagh, completes the Mosque of the Late Mohamed Abdulkhaliq Gargash (Dubai, UAE), a contemporary place of worship that is quietly masterful in its use of form, materiality and controlled natural light to evoke a sense of calm and spiritual connection and transition the worshipper from outer material world to inner sense of being. The mosque is one of the first in the UAE to be designed by a female architect.

Sumaya is one of only a few Saudi female architects of her generation and amongst a handful of women architects leading their own practice in the Gulf region. With a reputation for crafting culturally relevant buildings in dialogue with their surroundings, she places emphasis on the intangible in architecture; seeking to create meaning and a sense of the poetic to form a connection with each building’s user.

Previous projects include Mleiha Archaeological Centre (2016), a curved sandstone structure that rises from the desert in the small town of Mleiha, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The project was awarded an Architecture MasterPrize (2020), amongst other award wins, as well as being nominated for the Aga Khan Awards (2018). Creating a transition from outer material world to inner sense of being

As a gift to the community and in honour of the late patriarch of the family, Mohamed Abdulkhaliq Gargash, the Gargash family’s brief was to create a minimal contemporary mosque, a calm and spiritual space for prayer, for the community of the Al Quoz, the industrial heart of Dubai. Committed to supporting local industries and in keeping with the practice’s sustainable approach to design, Dabbagh Architects sourced materials from the mosque’s locality: stone from Oman; concrete, aluminium, cladding, joinery and ceramics from the UAE.

At the heart of the design approach is the enhancement of the act of worship and a transitional journey throughout the building so that the worshipper is ready for prayer and feels a sense of intimacy with the sacred.

“Creating a space of worship was a very particular design challenge. Prayer is a devotional act. It requires the worshipper to be totally present. With all the distractions in our modern busy lives it can be challenging to quieten the mind and find an inner calm to allow for full immersion into prayer,” says Sumaya. “Through the design, a series of spaces are created that allow the worshipper to transition from the busy outer world and prepare for an inner experience.”

Light as a tool to create a connection with the divine

Natural light is used as a tool to enhance a feeling of spirituality, the connection between the

earthly and the divine, and to mark the worshipper’s journey through the building. Scale also

plays a role in creating this sense of sacredness.

Starting at the mosque’s outdoor entrance, perforated shading creates a threshold of perforated light leading the worshipper to the ablution area where physical cleansing invites the clearing of the mind and preparation for prayer. The route continues through to a lobby space where further shedding of the material world takes place through the act of removing one’s shoes.

Once inside the prayer hall, the visitor further transitions to a contained space where reading from the Quran may take place before prayer. All the while, the quality of light from one space to another changes to enhance the preparation process, so that when the worshipper finally enters the main hall, they are ready for prayer.

“Muslim prayer is performed throughout the day at prescribed timings: at dawn, midday, afternoon, sunset and at night. This discipline creates a human connection with the natural day and night rhythm. The experience created through the design of the mosque seeks to enhance this connection through a controlled introduction of natural lighting,” explains Sumaya.

This is done in three ways: vertically, via the perforated dome to enhance the spiritual connection to the heavens, the shafts of light from the narrow openings on the sides further create a sense of illumination from the divine; indirectly, behind the Mihrab to highlight the point of focus in the prayer hall facing the direction of prayer; and, through a play of light from a series of small openings in the façade that follows the same decorative patterns of the interior.

Pared down form eschews traditional architectural typology

Dabbagh Architects sought to avoid multiple blocks, simplifying the traditional typology of the Islamic form and stripping it away to its essence. In the process of design development, the main building volume was separated into two: firstly, the prayer block containing the male and female prayer areas, and secondly the service block where the ablution facilities and residence for the Imam (the leader of prayer) and Moazen (caller of prayer) are found.

As a result of this division, a courtyard is formed which has a sculptural canopy reaching out to reconnect the two volumes together. With its two arms almost touching, the canopy gives a sense of separation of the functional and the more scared: the practicality of the ablution ritual and the spirituality of prayer. In further contrast to traditional mosque architecture, the minaret is designed as a separate volume.

A reinterpretation of Islamic geometry and metaphorically protective calligraphy The use of pattern and materiality in this project enhances the user’s experience as they journey from the outside into to the courtyard and enter the building. Throughout the building is a triangular pattern, a reference to traditional Islamic geometry but reinterpreted in a deconstructed contemporary language.

The exterior paneling uses this triangulated pattern in recessed and perforated elements, which gives the building’s skin a dynamic appearance. Internally, these perforations scatter natural light into the areas of worship with great control and care to illuminate the key spaces and create a calm atmosphere and sense of connection to the divine, as well as helping to cool the mosque’s interior.

The double skin dome also allows natural light to enter, filtering it through the internal decorative skin, which incorporates the same triangulated pattern as the rest of the building. This filtered light creates a soft naturally-lit prayer space tailoring to the introspective mind during prayer. The reinterpreted Islamic patterns and triangulated geometry harmonize throughout the interior as lines intersecting across walls, carpets and light fittings.

Calligraphy plays an important part in the overall design. A Surah (verse from the Quran) wraps around the prayer hall externally to create a metaphoric protective band signaling the spiritual nature of the space upon arrival and instilling a sacred energy throughout the building. The verse, “The Most Merciful”, is composed entirely in saj’, the rhyming, accent-based prose characteristic of early Arabic poetry and references the sun, the moon, the stars and heavens and many other creations.

“At the end of each project my hope is that the building will evoke the feelings and emotions that were envisioned at the outset. There is a defining, magical moment when the building is born and claims a life of its own. For this, my first mosque, that moment was particularly moving. I feel truly blessed to have had the opportunity to create a sacred space that brings people together for worship,” says Sumaya.

Mosque of the Late Mohamed Abdulkhaliq Gargash in Dubai, UAE – Building Information

Location: Um Suqeim Road, Al Quoz, Dubai, UAE

Completion date: 30.06.2021

Site Area: 3731.27 m2

Total BUA: 1680 m2

Classification: Juma’a (Friday) Mosque*

Lead architects: Dabbagh Architects – Sumaya Dabbagh, Sandrine Quoilin, Aleks

Zigalovs, Hana Younes, William Java

Structure engineers: Orient Crown Architectural

MEP Engineers: Clemson Engineering

Landscape Architects: WAHO Landscape Architecture

Client: Family of the late Mohamed Abdulkhaliq Gargash

Height Ground + 1

Structure: RC Concrete

Cladding: GRC Cladding

Canopy: Aluminium Canopy on Steel Support Structure

Joinery: Wood Veneer/HPL/Solid Wood/Solid Surface

*Mosque design in the Emirate of Dubai is governed by the Islamic and Charitable Affairs

Department. Mosques are classified by size into categories, Juma (Friday) Mosque is a medium

size mosque with a capacity of approximately 1000 worshippers. It is used for daily as well as

Friday prayers. The mosque is required to house on site an Imam (the leader of prayer) and

Moazen (the caller of prayer).

Sumaya Dabbagh

About Sumaya Dabbagh RIBA, Principal, Dabbagh Architects

Saudi architect Sumaya Dabbagh founded Dabbagh Architects in Dubai, UAE in 2008. The practice

sets out to create contemporary architecture that is culturally and environmentally sensitive: a

timeless architecture that creates a positive impact on the world.

Following an education in Architecture at Bath University, UK (BSc and BArch, 1990), Sumaya

began her career in London and Paris in the early 90s. Her return to the Gulf region in 1993 was

part of a quest to gain a deeper understanding of her own identity, a unique mix of influences

and sensitivity towards both western and middle eastern cultures.

Through her work in architecture and design in the Gulf region, Sumaya aims to bridge cultural

and gender gaps and has broken stereotypes and limiting beliefs about Saudi Arabia, the Gulf,

and Arab Women. As one of the few Saudi women of her generation to train as an architect and

one of the first women in architecture to found their own practices in the UAE, Sumaya is an

example of what women can achieve and how much they can influence change. In 2019 she won

the Principal of the Year Award at the Middle East Architects Awards and became a finalist at The

Tamayouz Award for Women of Outstanding Achievements.

Sumaya is passionate about bringing more awareness to the region on the value of a sensitive

and sustainable approach to design. As one of the first RIBA Chartered Practice in the Gulf

region, Dabbagh Architects is known for its quality-driven design and the practice undertakes

diverse sectors, such as commercial, residential, educational, as well as cultural projects.

The Mleiha Archaeological Centre (2016) is globally recognized as a significant example of a new

emerging approach to architecture in the UAE and won multiple awards including a prestigious

Architecture Master Prize (2020) and Agha Khan Awards (2018) nomination. Gargash Mosque

(2021) is a recent addition to Dabbagh Architects’ portfolio of sensitive, contextual designs.

Currently the practice is working on new prestigious cultural projects such as Al Ain Museum

(2023) and other projects in Saudi Arabia. The practice’s projects were showcased in RIBA/d3

Dubai Festival of Architecture’s “Emerging Architecture in the Gulf” exhibition during Dubai

Design Week 2020.

All content by Dabbagh Architects

Photography by Gerry O’Leary Photography

Video by Intelier

https://ift.tt/3AvCEIu

LinkedIn: Dabbagh Architects | Instagram: @dabbagharchitects_

Mosque building designs

Mosque of the Late Mohamed Abdulkhaliq Gargash images / information received 200921 from Dabbagh Architects

Location: Um Suqeim Road, Al Quoz, Dubai, UAE

UAE Mosque Buildings

United Arab Emirates Mosque buildings

Sheikh Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nayhan Mosque, Abu Dhabi

Spatium

photograph : Speirs and Major Associates

Abu Dhabi Mosque Building

WTC Mosque, World Trade Center, Abu Dhabi, UAE

Design: AL_A architects

image from architect

WTC Mosque Abu Dhabi

Middle East Mosque building design

AlJabri Mosque in Ha’il, Saudi Arabia

Design: Schiattarella Associati architects

image from architects

AlJabri Mosque Building in Ha’il

Dubai Architecture

Dubai Architecture Designs – chronological list

Dubai Building News

Al Seef Dubai Creek Master Plan

Architects: GAJ (Godwin Austen Johnson)

photograph : Chris Goldstraw

Al Seef Dubai Creek

Dubai Architecture Tours by e-architect

Aljada’s Central Hub, Sharjah, UAE

Design: Zaha Hadid Architects

image courtesy of architects

Aljada Sharjah

Sharjah Architecture Triennial

photo : Ieva Saudargaitė

Sharjah Architecture Triennial News

Al Seef Dubai Project

Architects: 10 DESIGN

photograph : Gerry O’Leary

Al Seef Dubai Project

1/JBR Tower

Design: EDGE Architects

image courtesy of architects

1/JBR Tower Dubai

Comments / photos for the Mosque of the Late Mohamed Abdulkhaliq Gargash page welcome

The post Mosque of the Late Mohamed Abdulkhaliq Gargash appeared first on e-architect.

0 notes

Text

41 tools to write (and critique) effectively

When refining, rewriting, editing and critiquing, what should you be looking for? Sentence structure? Character believability? Setting? Sometimes it can be a bit much to keep everything in your head, so I’ve written the following list of things I look for (or need to remind myself to pay attention to) in order to make my writing, and my critiques of other writers, as effective as possible. Hopefully it works for you too.

Style

Is sentence length varied?

Do sentences flow naturally?

Is the information being communicated accurately and effectively?

Do sentences start and end with strong, evocative words?

Are long, wandering sentences used effectively, or should they be broken into shorter, punchier and easier to follow ones (depends on the situation. Long is good for lists and important points. Short is good for immediacy and impact.)

Are there too many -ing and -ly words bunched together (happening, doing, jumping, running, happily, excitedly, remotely)? Too many of these words weaken prose.

Are there semicolons? Rip them out.

Are there parenthesis? Can they be justified? If not, rip them out.

Are the colons? Can they be justified? If not, rip them out too.

Are two words used where only one will do?

Are there phrases like ‘in fact’, ‘there was’, ‘she had said’, etc. Rip those out.

Are the words on the page interesting in themselves? Trade common words and phrases for unique ones. Make the familiar unfamiliar and the unfamiliar familiar.

Is the same word used twice in a paragraph? If so, there better be a reason for it. Clarity and rhythm are good reasons, lack of vocabulary is not.

Does it read like I spent all my time looking at a thesaurus? Simplify.

Can a dumb reader make sense of your complex ideas? Consider simplifying your explinations.

Does a smart reader feel they’re being talked down to? Make your ideas bigger.

Descriptions

As a reader, can I inhabit the scene with the information given?

Are all the senses engaged? Can the prose make a blind man see or a deaf man hear? If not, add more.

Is the flow of narrative slowed by an overabundance of description? Pair it down or rearrange it.

Are the details portrayed in logical order?

Are descriptions of everyday things lending value? Again, make the familiar unfamiliar and the unfamiliar familiar.

Characters

Do we know the character enough to justify the current scene?

Does the characters actions make sense from the characters point of view?

From reading the current scene, can I imagine how the character might behave in a different situation? If not, the character is not as well defined as it should be.

Can I picture the character in my head? If not, add more description and do it early.

Does character speech feel natural. Read aloud.

What mannerisms does this character have? Do they have a tick, a habit, or feature that sets them apart?

What does each character want? How badly do they want it? What are they willing to do to get it?

Do character actions reveal something about the character, or are they superfluous?

Scenes

Is the current scene vital? Justify it, if you can’t, cut it.

What is the purpose of this scene? Furthering plot, building character, etc. Every scene should do what it does well.

Does the current scene feel familiar? Is it familiar to another scene in the work, or familiar to something from somewhere else? If so, there better be a really good reason.

Where is the tension / suspense? (from wikipedia: Suspense is a feeling of pleasurable fascination and excitement mixed with apprehension, tension, and anxiety developed from an unpredictable, mysterious, and rousing source of entertainment) How many layers of tension / suspense are there? More on this next.

Is there a basic level of tension? If there are two characters, they should each want something different. If characters have the same wants, then something should get in there way. If life is easy, then the read is boring.

Is there a middle layer of suspense? Something else above the immediate scene should be looming. Something outside of the characters current control.

Is there a grand level of suspense? There should be a singular overarching thing that drives the story, gives it a time limit, forces the characters to make difficult choices again and again. If it’s a villain, it better be a damn good one.

Cohesion

Can each scene be explained in one or two sentences? Hone them.

Can each chapter be explained in one or two sentences? Hone some more.

Can the entire plot be explained in one or two sentences? If not, focus, hone, find the heart of the story and throw the rest away.

Is the word count justified? The entire reading experience should feel tight, even if it’s 200,000 words or more. If there is a moment of boredom, cut cut cut.

In the end, am I fulfilled but wishing there was just a little more. Perfect, time to start the next book.

3 notes

·

View notes