#aspirated consonant

Text

the listener's ability to perceive minute changes in sound waves within speech sounds is actually fucking amazing

#shay posts#We can perceive slight resonances/formants#and use that to distinguish one consonant from another??#incredible. and its taught to! ppl who've grown up speaking one language for example might not perceive a difference between /t/ and /k/#for an example. but english does#plus some languages distinguish between /p/ and an aspirated /p/ to the point where it would create a whole new word if its replaced w /p/#and yet eng doesnt distinguish between them. its FACINATING#im sure animals do it too but man going into phonphon after finishing project hail mary is a trip#considering Ryland learns to understand eiridian#even tho he physically cannot produce their sounds. facinating

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

native speaker with no linguistic background vs overly clinical linguistic pronunciation breakdown: fight

#its always shit like 'this is an 'a' sound like the 'a' and 'apple :D'' <-distinctly different vowel sound that has no english equivalent#or#'this consonant is voiced between sonorants but voiceless elsewhere and also aspirated at initial position in younger speaweijehd*static*#the ho rambles

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

first sentence in my new, as of yet unnamed conlang! ṭais kharxara haiṭa (/ʈais ˈkʰar.xa.ra ˈhai.ʈa/) - I see a deer (or, rather, 1SG.ERG deer-I.SG.ABS see-NP.1SG). Just something simple to start with and very much subject to change, but I like the direction it's taking so far. The writing script is a sort of alphasyllabary, where letters can be stacked on top of each other to form syllable blocks.

#actually ill probably make it a pro-drop lang cus i love pro-drop and ive never incorporated it into a clong#also fun fact it has split ergativity and the erg-abs are only used bc the verb is in the perfective aspect#imperfective uses nom-acc#which is also a type of split ergativity that i havent used before! and ive never used retroflex consonants or phonemic aspiration!#very fun things happening in my excel file right now#my conlangs#conlang#neography#irkan osla

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

i find it so weird that native english speakers aren’t taught proper linguistics in school

#russian schooling isn’t perfect by any means but you have to know a good bit of linguistics before even attempting to begin#properly speaking the language. however this doesn’t seem to be a requirement for english speakers which is just supremely puzzling#please tell me they teach you about voiced and aspirated consonants in elementary school at least

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

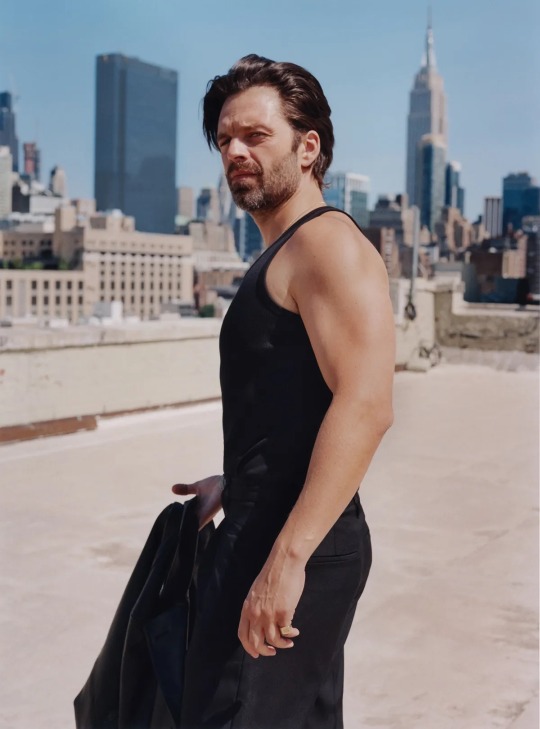

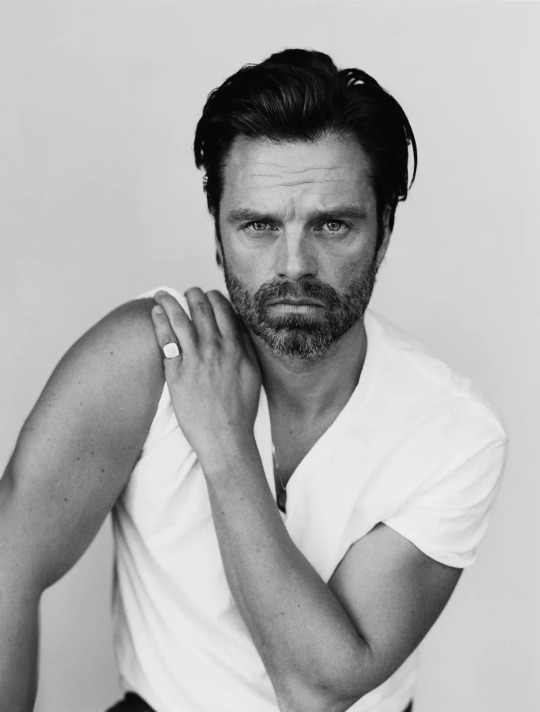

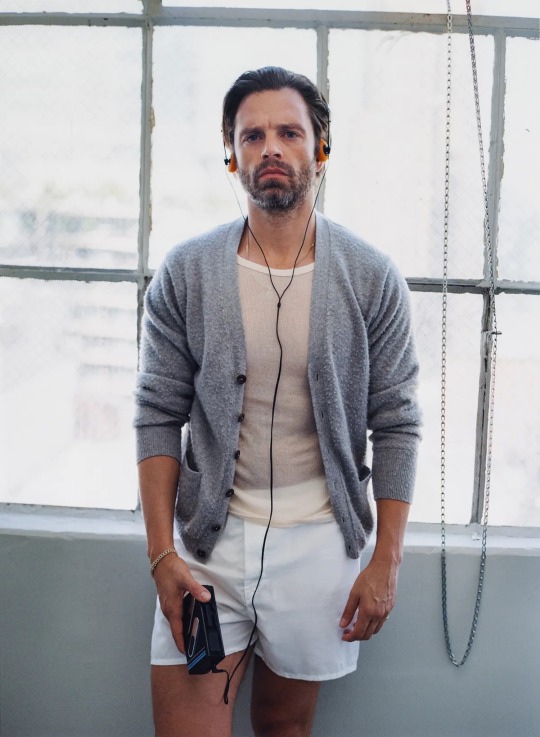

Sebastian Stan Tells All: Becoming Donald Trump, Gaining 15 Pounds and Starring in 2024’s Most Controversial Movie

By Daniel D'Addario

Sebastian Stan Variety Cover Story

It started with the most famous voice on the planet, the one that just won’t shut up.

Sebastian Stan, in real life, sounds very little like Donald Trump, whom he’s playing in the new film “The Apprentice.” Sure, they share a tristate accent — Stan has lived in the city for years and attended Rutgers University before launching his career — but he speaks with none of Trump’s emphasis on his own greatness. Trump dwells, Stan skitters. Trump attempts to draw topics together over lengthy stem-winders (what he recently called “the weave”), while Stan has a certain unwillingness to be pinned down, a desire to keep moving. It takes some coaxing to bring Stan, a man with the upright bearing and square jaw of a matinee idol, to speak about his own process — how hard he worked to conjure a sense Trump, and how he sought to bring out new insights about America’s most scrutinized politician.

“I think he’s a lot smarter than people want to say about him,” Stan says, “because he repeats things consistently, and he’s given you a brand.” Stan would know: He watched videos of Trump on a loop while preparing for “The Apprentice.” In the film, out on Oct. 11, Stan plays Trump as he moves from insecure, aspiring real estate developer to still insecure but established member of the New York celebrity firmament.

We’re sitting over coffee in Manhattan. Stan is dressed down in a black chore coat and black tee, yet he’s anything but a casual conversation partner. He rarely breaks eye contact, doing so only on the occasions when he has something he wants to show me on his iPhone (cracked screen, no case). In this instance, it’s folders of photos and videos labeled “DT” and “DT PHYSICALITY.”

“I had 130 videos on his physicality on my phone,” Stan says. “And 562 videos that I had pulled with pictures from different time periods — from the ’70s all the way to today — so I could pull out his speech patterns and try to improvise like him.” Stan, deep in character, would ad-lib entire scenes at director Ali Abbasi’s urging, drawing on the details he’d learned from watching Trump and reading interviews to understand precisely how to react in each moment.

“Ali could come in on the second take and say, ‘Why don’t you talk a little bit about the taxes and how you don’t want to pay?’ So I had to know what charities they were going to in 1983. Every night I would go home and try not only to prepare for the day that was coming, but also to prepare for where Ali was going to take this.”

Looking at Stan’s phone, among the endless pictures of Trump, I glimpse thumbnails of Stan’s own face perched in a Trumpian pout and videos of the actor’s preparation just aching to be clicked — or to be stored in the Trump Presidential Library when this is all over in a few months, or in 2029, or beyond.

“I started to realize that I needed to start speaking with my lips in a different way,” Stan says. “A lot of that came from the consonants. If I’m talking, I’m moving forward.” On film, Stan shapes his mouth like he can’t wait to get the plosives out, puckering without quite tipping into parody. “The consonants naturally forced your lips forward.”

“If he did 10% more of what he did, it would become ‘Saturday Night Live,’” Abbasi says. “If he did 10% less, then he’s not conjuring that person. But here’s the thing about Sebastian: He’s very inspired by reality, by research. And that’s also the way I work; if you want to go to strange places, you need to get your baseline reality covered very well.”

A little later, Stan passes me the phone again to show me a selfie of him posing shirtless and revealing two sagging pecs and a bit of a gut. He’s pouting into a mirror. If his expression looks exaggerated, consider that he was in Marvel-movie shape before stepping into the role of the former president; the body transformation happened rapidly and jarringly. Trump’s size is a part of the film’s plot — as Trump’s sense of self inflates, so does he. In a rush to meet the shooting deadline for “The Apprentice,” Abbasi asked Stan, “How much weight can you gain?”

“You’d be surprised,” Stan tells me. “You can gain a lot of weight in two months.” (Fifteen pounds, to be exact.)

Now he’s back in fighting form, but the character has stayed with him. After years of playing second-fiddle agents of chaos — goofball husbands to Margot Robbie’s and Lily James’ characters in “I, Tonya” and Hulu’s “Pam & Tommy,” surly frenemy to Chris Evans’ Captain America in the Marvel franchise — Stan plunged into the id of the man whose appetites have reshaped our world. He had to have a polished enough sense of Trump that he could improvise in character, and enough respect for him to play him as a human being, not a monster.

It’s one of two transformations this year for Stan — and one that might give a talented actor that most elusive thing: a brand of his own. He’s long been adjacent enough to star power that he could feel its glow, but he hasn’t been the marquee performer. While his co-stars have found themselves defined by the projects he’s been in — from “Captain America” and “I, Tonya” back to his start on “Gossip Girl” — he’s spent more than a decade in the public eye while evading being defined at all.

This fall promises to be the season that changes all that: Stan is pulling double duty with “The Apprentice” and “A Different Man” (in theaters Sept. 20), in which he plays a man afflicted with a disfiguring tumor disorder who — even when presented with a fantastical treatment that makes him look like, well, Sebastian Stan — can’t be cured of ailments of the soul. For “A Different Man,” Stan won the top acting prize at the Berlin Film Festival; for “The Apprentice,” the sky’s the limit, if it can manage to get seen. (More on that later.)

One reason Stan has largely evaded being defined is that he’s never the same twice, often willing to get loopy or go dark in pursuit of his characters’ truths. That’s all the more true this year: In “The Apprentice,” he’s under the carapace of Trumpiness; in “A Different Man,” his face is hidden behind extensive prosthetics.

“In my book, if you’re the good-looking, sensitive guy 20 movies in a row, that’s not a star for me,” says Abbasi, who compares Stan to Marlon Brando — an actor eager to play against his looks. “You’re just one of the many in the factory of the Ken dolls.”

This fall represents Stan’s chance to break out of the toy store once and for all. His Winter Soldier brought a jolt of evil into Captain America’s world, and his Jeff Gillooly was the devil sitting on Tonya Harding’s shoulder. Now Stan is at the center of the frame, playing one of the most divisive characters imaginable. So he’s showing us where he can go. The spotlight is his, and so is the risk that comes with it.

Why take such a risk?

The script for “The Apprentice,” which Stan first received in 2019, but which took years to come together, made him consider the American dream, the one that Trump achieved and is redefining.

Stan emigrated with his mother, a pianist, from communist Romania as a child. “I was raised always aware of the American dream: America being the land of opportunity, where dreams come true, where you can make something of yourself.” He pushes the wings of his hair back to frame his face, a gold signet ring glinting in the late-summer sunlight, and, briefly, I can hear a hint of Trump’s directness of approach. “You can become whoever you want, if you just have a good idea.” Stan’s good idea has been to play the lead in movies while dodging the formulaic identity of a leading man, and this year will prove just how far he can take it.

“The Apprentice” seemed like it would never come together before suddenly it did. This time last year, Stan was sure it was dead in the water, and he was OK with that. “If this movie is not happening, it’s because it’s not meant to happen,” he recalls thinking. “It will not be because I’m too scared and walk away.”

Called in on short notice and filming from November 2023 to January of this year (ahead of a May premiere in Cannes), Stan lent heft and attitude to a character arc that takes Trump from local real estate developer in the 1970s to national celebrity in the 1980s. He learns the rough-and-tumble game of power from the ruthless and hedonistic political fixer Roy Cohn (Jeremy Strong), eventually cutting the closeted Cohn loose as he dies of AIDS and alienating his wife Ivana (Maria Bakalova) in the process. (In a shocking scene, Donald sexually assaults Ivana in their Trump Tower apartment.) For all its edginess, the film is about Trump’s personality — and the way it calcified into a persona — rather than his present-day politics. (Despite its title, it’s set well before the 2004 launch of the reality show that finally made Trump the superstar he longed to be.)

And despite the fact that Trump has kept America rapt since he announced his run for president in 2015, Hollywood has been terrified of “The Apprentice.” The film didn’t sell for months after Cannes, an unusual result for a major English-language competition film, partly because Trump’s legal team sent a cease-and-desist letter attempting to block the film’s release in the U.S. while the fest was still ongoing. When it finally sold, it was to Briarcliff Entertainment, a distributor so small that the production has launched a Kickstarter campaign to raise money so that it will be able to stay in theaters.

Yes, Hollywood may vote blue, but it’s not the same town that released “Fahrenheit 9/11” or even “W.,” let alone a film that depicts the once (and possibly future) president raping his wife. (The filmmakers stand behind that story. “The script is 100% backed by my own interviews and historical research,” says Gabriel Sherman, the screenwriter and a journalist who covers Trump and the American conservative movement. “And it’s important to note that it is not a documentary. It’s a work of fiction that’s inspired by history.”) Entertainment corporations from Netflix to Disney would be severely inconvenienced if the next president came into office with a grudge against them.

“I am quite shocked, to be honest,” Abbasi says. “This is not a political piece. It’s not a hit piece; it’s not a hatchet job; it’s not propaganda. The fact that it’s been so challenging is shocking.” Abbasi, born in Iran, was condemned by his government over his last film, “Holy Spider,” and cannot safely return. He sees a parallel in the response to “The Apprentice.” “OK, that’s Iran — that is unfortunately expected. But I wasn’t expecting this.”

“Everything with this film has been one day at a time,” Stan says. The actor chalks up the film’s divisiveness to a siloed online environment. “There are a lot of people who love reading the [film’s] Wikipedia page and throwing out their opinions,” he says, an edge entering his voice. “But they don’t actually know what they’re talking about. That’s a popular sport now online, apparently.”

Unprompted, Stan brings up the idea that Trump is so widely known that some might think a biographical film about him serves no purpose. “When someone says, ‘Why do we need this movie? We know all this,’ I’ll say, ‘Maybe you do, but you haven’t experienced it. The experience of those two hours is visceral. It’s something you can hopefully feel — if you still have feelings.’”

After graduating from Rutgers in 2005, Stan found his first substantial role on “Gossip Girl,” playing troubled rich kid Carter Baizen. Like teen soaps since time immemorial, “Gossip Girl” was a star-making machine. “It was the first time I was in serious love with somebody,” he says. (He dated the series’ star, Leighton Meester, from 2008 to 2010.) He feels nostalgic for that moment: “Walking around the city, seeing these same buildings and streets — life seemed simpler.”

Stan followed his “Gossip Girl” gig with roles on the 2009 NBC drama “Kings,” playing a devious gay prince in an alternate-reality modern world governed by a monarchy, and the 2012 USA miniseries “Political Animals,” playing a black-sheep prince (and once again a gay man) of a different sort — the son of a philandering former president and an ambitious former first lady.

When I ask him what lane he envisioned himself in as a young actor, he shrugs off the question. “I grew up with a single mom, and I didn’t have a lot of male role models. I was always trying to figure out what I wanted to be. And at some point, I was like, I could just be a bunch of things.”

Which might seem challenging when one is booked to play the same character, Bucky Barnes, in Marvel movie after Marvel movie. Bucky’s adventures have been wide-ranging — he’s been brainwashed and turned evil and then brought back to the home team again, all since his debut in 2011’s “Captain America: The First Avenger.” Next year, he’ll anchor the summer movie “Thunderbolts,” as the leader of a squad of quirky heroes played by, among others, Julia Louis-Dreyfus and Florence Pugh. It’s easy to wonder if this has come to feel like a cage of sorts.

Not so, says Stan. His new Marvel film “was kind of like ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’ — a guy coming into this group that was chaotic and degenerate, and somehow finding a way to unite them.”

Lately, knives have been out for Marvel movies as some have disappointed at the box office, and “Thunderbolts,” which endured strike delays and last-minute cast changes, has been under scrutiny.

“It’s become really convenient to pick on [Marvel films],” Stan says. “And that’s fine. Everyone’s got an opinion. But they’re a big part of what contributes to this business and allows us to have smaller movies as well. This is an artery traveling through the system of this entire machinery that’s Hollywood. It feeds in so many more ways than people acknowledge.” He adds, “Sometimes I get protective of it because the intention is really fucking good. It’s just fucking hard to make a good movie over and over again.”

Which may account for an eagerness to try something new. “In the last couple of years,” he says, “I’ve gotten much more aggressive about pursuing things that I want, and I’m constantly looking for different ways of challenging myself.”

The challenge continued throughout the shoot of “The Apprentice,” as Stan pushed the material. “One of the most creatively rewarding parts of the process was how open Sebastian was to giving notes on the script but also wanting to go beyond the script,” says Sherman, the screenwriter. “If he was interested in a certain aspect of a scene, he was like, Can you find me a quote?” he recalls.

Building a dynamic through improvised scenes, Stan and Strong stayed in character throughout the “Apprentice” shoot. “I was doing an Ibsen play on Broadway,” says Strong, who won a Tony in June for his performance in “An Enemy of the People,” “and he came backstage afterwards. And it was like — I’d never really met Sebastian, and I don’t think he’d ever met me. So it was nice to meet him.”

Before the pair began acting together, they didn’t rehearse much — “I’m not a fan of rehearsals,” Strong says. “I think actors are best left in their cocoon, doing their work, and then trusted to walk on set and be ready.” The two didn’t touch the script together until cameras went up — though they spent a preproduction day, Strong says, playing games in character as Donald and Roy.

After filming, both have kept memories of the hold their characters had on them. They shared a flight back from Telluride — a famously bumpy trip out of the mountains. “He’s a nervous flyer, and I’m a nervous flyer,” Stan says. Both marveled at the fact that they’d contained their nerves on the first day of shooting “The Apprentice,” when their characters traveled together via helicopter. “We both go, ‘Yeah — but there was a camera.’”

Stan’s aggressive approach to research came in handy on “A Different Man,” which shot before “The Apprentice.” His character’s disorder, neurofibromatosis, is caused by a genetic mutation and presents as benign tumors growing in the nervous system. After being healed, he feels a growing envy for a fellow sufferer who seems unbothered by his disability.

Stan’s co-star, Adam Pearson, was diagnosed with neurofibromatosis in early childhood. Stan found the experience challenging to render faithfully. “I said many times, I can do all the research in the world, but am I ever going to come close to this?” Stan says. “How am I going to ever do this justice?”

Plus, he had precious little time to prepare: “He was fully on board, and the film was being made weeks later,” director Aaron Schimberg says. “Zero to 60 in a matter of weeks.”

The actor grappled for something to hold on to, and Pearson sug gested he refer to his own experience of fame. “Adam said to me, ‘You know what it’s like to be public property,’” Stan says.

Pearson recalls describing the experience to Stan this way: “While you don’t understand the invasiveness and the staring and the pointing that I’ve grown up with, you do know what it’s like to have the world think you owe them something.”

That sense of alienation becomes universal through the film’s storytelling: “A Different Man” takes its premise as the jumping-off point for a deep and often mordant investigation of who we all are underneath the skin.

The film was shot in 22 days in a New York City heat wave, and there was, Schimberg says, “no room for error. I would get four or five takes, however many I could squeeze out, but there’s no coverage.”

Through it all, Stan’s performance is utterly poised — Schimberg and Stan discussed Buster Keaton as a reference for his ability to be “completely stone-faced” amid chaos, the director says. And the days were particularly long because Oscar-nominated prosthetics artist Michael Marino was only able to apply Stan’s makeup in the early morning, before going to his job on the set of “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel.”

“Even though I wasn’t shooting until 11 a.m., I would go at like 5 in the morning to his studio, or his apartment,” Stan recalls. The hidden advantage was that Stan had hours to kill while made up like his character, the kind of person the world looks past. “I wanted to walk around the city and see what happened,” Stan says. “On Broadway, one of the busiest streets in New York, no one’s looking at me. It’s as if I’m not even there.” The other reaction was worse: “Somebody would immediately stop and very blatantly hit their friend, point, take a picture.”

It was a study in empathy that flowed into the character. Stan had spoken to Pearson’s mother, who watched her son develop neurofibromatosis before growing into a disability advocate and, eventually, an actor. “She said to me, ‘All I ever wanted was for someone to walk in his shoes for a day,’” Stan recalls. “And I guess that was the closest I had ever come.”

“The Apprentice” forced Stan, and forces the viewer, to do the same with a figure that some 50% of the electorate would sooner forget entirely. And that lends the film its controversy. Those on the right, presupposing that the movie is an anti-Trump document, have railed against it. In a statement provided to Variety, a Trump campaign spokesman said, “This ‘film’ is pure malicious defamation, should never see the light of day and doesn’t even deserve a place in the straight-to-DVD section of a bargain bin at a soon-to-be-closed discount movie store, it belongs in a dumpster fire.” The campaign threatened a lawsuit, though none has materialized.

Asked about the assault scene, Stan notes that Ivana had made the claim in a deposition, but later walked it back. “Is it closer to the truth, what she had said directly in the deposition or something that she retracted?” he asks. “They went with the first part.”

The movie depicts, too, Ivana’s carrying on with her marriage after the violation, which may be still more devastating. “How do you overcome something like this?” asks Bakalova. “Do you have to put on a mask that everything is fine? In the next scene, she’s going to play the game and pretend that we’re the glamorous, perfect couple.” The Trumps, in “The Apprentice,” live in a world of paper-thin images, one that grows so encompassing that Donald no longer feels anything for the people to whom he was once loyal. They’re props in his stage show.

“The Apprentice” will drop in the midst of the most chaotic presidential election of our lifetime. “The way it lands in this extremely polarized situation, for me as an artist, is exciting. I won’t lie to you,” says Abbasi.

When asked if he was concerned about blowback from a Trump 47 presidency, Stan says, “You can’t do this movie and not be thinking about all those things, but I really have no idea. I’m still in shock from going from an assassination attempt to the next weekend having a president step down [from a reelection bid].”

Stan’s job, as he sees it, was to synthesize everything he’d absorbed — all those videos on his phone — into a person who made sense. This Trump had to be part of a coherent story, not just the flurry of news updates to which we’ve become accustomed.

“You can take a Bach or a Beethoven, and everyone’s going to play that differently on the piano, right?” Stan says. (His pianist mother named him for Johann Sebastian Bach.) “So this is my take on what I’ve learned. I have to strip myself of expectations of being applauded for this, if people are going to like it or people are going to hate it. People are going to say whatever they want. Hopefully they should think at least before they say it.”

It’s a reality that Stan is now used to — the work is the work, and the way people interpret him is none of his business. Perhaps that’s why he has run away from ever being the same thing twice. “I could sit with you today and tell you passionately what my truth is, but it doesn’t matter,” he says. “Because people are more interested in a version of you that they want to see, rather than who you are.”

“The Apprentice” has been the subject of extreme difference of opinion by many who have yet to see it. It’s been read — and will continue to be after its release — as anti-Trump agitprop. The truth is chewier and more complicated, and, perhaps, unsuited for these times.

“Are we going to live in a world where anyone knows what the truth is anymore? Or is it just a world that everyone wants to create for themselves?” Stan asks.

His voice — the one that shares a slight accent with Trump but that is, finally, Stan’s own — is calm and clear. “People create their own truth right now,” he says. “That’s the only thing that I’ve made peace with; I don’t need to twist your arm if that’s what you want to believe. But the way to deal with something is to actually confront it.”

#Variety#Sebastian Stan#Photoshoot#A Different Man#The Apprentice#Thunderbolts*#Marvel#Interview#mrs-stans

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

i'm using an open source online textbook (ancient greek for everyone) as part of my "get better at latin and greek" summer project and so far it's a pretty solid textbook but the thing it does that makes it really, really useful is it tells you what the stem is for each word and then explain why that stem transforms/changes.

like for example for "τιθημι" it says that the stem is "θη," but in the present tense it's reduplicated, but you can't reduplicate an aspirated consonant like θ so you use a τ instead. and when explaining third declension nouns it explains that the masculine/feminine nominative ending is -ς, and in words where the stem ends in a consonant it will often either remove the stem's final consonant (παιδ- -> παιδς -> παις) or the -ς will drop (δαιμων- -> δαιμωνς -> δαιμων). these are just a couple examples but so far these explanations are making it much much clearer how we get all the irregularities that i was originally told i just had to memorize with little rhyme or reason behind it. greek makes a lot more sense this way.

so anyway i recommend this to anyone who's looking to learn/improve at greek!

#mod felix#resources#tagamemnon#i suspect knowing the stem for the verbs is a surprise tool that will help us later but i haven't gotten there yet in the book

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

the way that i can always tell if dan is saying “phan” or “fan” rattles me to my core every time. he aspirates the FUCK out of that voiceless labiodental fricative so violently it’s practically a voiced consonant am i right, ling phannies 😝

#another niche ass post about linguistics#i need to start the field of phanology so bad#the phield of phanology#/fæn/ vs /fʰæn/ but i feel like there’s even more of a difference for transciption#like they both hold the /f/ longer and with more emphasis#idk how to transcribe it other than adding the aspiration symbol#i don’t have a fancy english language and linguistics degree from the university of york like mr amazing or anything#dan and phil#dnp#phan#dan howell#daniel howell#amazingphil#phil lester#danisnotonfire#yeet my deenp#yeet my deet#lingblr#ipa#international phonetic alphabet#pp42??

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

This cat's name is Peaches, and she is my role model. But let's talk about Russian phonetics.

My neighbours once told me that they honestly believed that her name is Bitches. When I call her home, this is what they hear: Bitches.

And there are at least two linguistic reasons why this happens. First, in Russian, we don't have tense and lax vowels. It took me a while just to learn to hear the difference between 'shit' and 'sheet', and I am still tying to re-train my articulation apparatus to make this distinction when I speak. So, "peaches" may well sound like 'pitches' to my English speaking neighbours.

But why B? Well, in Russian, we put a lot of energy to consonants, and we don't aspirate. Even though P is devocalized, the energy I put in P is enough to confuse my poor neighbours. Russian is simply more energy-fuelled and less "breathy" than English.

Well, anyway, Peaches is very independent, always knows what she wants, always looking to make the most of the moment and enjoys life to the fullest. She turned 11 years old a couple of weeks ago and is the happiest cat in the world.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mycenaean Greek

(and examples of lexical evolution to Modern Greek)

Mycenaean Greek is the most ancient attested form of the Greek language (16th to 12th centuries BC). The language is preserved in inscriptions of Linear B, a script first attested on Crete before the 14th century BC. The tablets long remained undeciphered and many languages were suggested for them until Michael Ventris, building on the extensive work of Alice Kober, deciphered the script in 1952. This turn of events has made Greek officially the oldest recorded living language in the world.

What does this mean though? Does it mean that a Modern Greek could speak to a resurrected Mycenaean Greek and have an effortless chat? Well obviously not. But we are talking about the linear evolution of one single language (with its dialects) throughout time that was associated with one ethnic group, without any parallel development of other related languages falling in the same lingual branch whatsoever.

Are we sure it was Greek though? At this point, yes, we are. Linguists have found in Mycenaean Greek a lot of the expected drops and innovations that individualised the Hellenic branch from the mother Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). In other words, it falls right between PIE and Archaic Greek and resembles what Proto-Greek is speculated to have been like. According to Wikipedia, Mycenaean Greek had already undergone all the sound changes particular to the Greek language.

Why was it so hard to decipher Linear B and understand it was just very early Greek? Can an average Greek speaker now read Linear B? No. An average Greek speaker cannot read Linear B unless they take into account and train themselves on certain rules and peculiarities that even took specialized linguists ages to realise and get used to. Here's the catch: Linear B was a script inspired by the Minoan Linear A, both of which were found in the Minoan speaking Crete. (Minoan Linear A inscriptions have yet to be deciphered and we know nothing about them.) The Mycenaeans (or was it initially the Minoans???) made only minimal modifications to produce the Linear B script and used it exclusively for practical purposes, namely for accounting lists and inventories. Linear B however was an ideographic and syllabic script that stemmed from a script that originally was not designed to render the Mycenaean Greek language, and thus it could not do it perfectly. In other words, the script itself does not render the Greek words accurately which is what made it extremely hard even for the linguists to decipher these inscriptions. Due to its limited use for utility and not for prose, poetry or any other form of expression, the Mycenaean Greeks likely did not feel compelled to modify the script heavily into some more appropriate, accurate form to cover the language's needs.

Examples of the script's limitations:

I won't mention them all but just to give you an idea that will help you then read the words more easily:

In the syllabic script Linear B, all syllable symbols starting with a consonant obligatorily have a vowel following - they are all open sylllables without exception. Linear B can NOT render two consonants in a row which is a huge handicap because Greek absolutely has consonants occuring in a row. So, in many cases below, you will see that the vowel in the script is actually fake, it did not exist in the actual language, and I might use a strikethrough to help you out with this.

For the same reason, when there are consonants together, at least one of them is often casually skipped in Linear B!

There were no separate symbols for ρ (r) and λ (l). As a result, all r and l sounds are rendered with the r symbol.

Exactly because many Greek words end in σ, ς (sigma), ν (ni), ρ (rho) but in Linear B consonants must absolutely be followed by a vowel, a lot of time the last letter of the words is skipped in the script!

Voiced, voiceless and aspirate consonants all use the same symbols, for example we will see that ka, ha, gha, ga all are written as "ka". Pa, va, fa (pha), all are written as "pa". Te, the are written as "te".

There are numerous other limitations but also elements featured that were later dropped from the Greek language, i.e the semivowels, j, w, the digamma, the labialized velar consonants [ɡʷ, kʷ, kʷʰ], written ⟨q⟩, which are sometimes successfully represented with Linear B. However, that's too advanced for this post. I only gave some very basic, easy guidelines to help you imagine in your mind what the word probably sounded like and how it relates to later stages of Greek, and modern as is the case here. That's why I am also using simpler examples and more preserved vocabulary and no words which include a lot of these early elements which were later dropped or whose decoding is still unclear.

Mycenaean Linear B to Modern Greek vocabulary examples:

a-ke-ro = άγγελος (ágelos, angel. Notice how the ke symbol is representing ge, ro representing lo and the missing ending letter. So keep this in mind and make the needed modifications in your mind with the following examples. Also, angel actually means "messenger", "announcer". In the Christian context, it means "messenger from God", like angels are believed to be. So, that's why it exists in Mycenaean Greek and not because Greeks invented Christianity 15 centuries before Jesus was born XD )

a-ki-ri-ja = άγρια (ághria, wild, plural neuter. Note the strikethrough for the nonexistent vowel)

a-ko-ro = αγρός (aghrós, field)

a-ko-so-ne = άξονες (áksones, axes)

a-na-mo-to = ανάρμοστοι (anármostoi, inappropriate, plural masculine. Note the skipped consonants in the script)

a-ne-mo = ανέμων (anémon, of the winds)

a-ne-ta = άνετα (áneta, comfortable, plural neuter, an 100% here, well done Linear B!)

a-po-te-ra = αμφότερες (amphóteres, or amphóterae in more Archaic Greek, both, plural feminine)

a-pu = από (apó, from)

a-re-ka-sa-da-ra = Αλεξάνδρα (Alexandra)

de-de-me-no = (δε)δεμένο (ðeðeméno, tied, neuter, the double de- is considered too old school, archaic now)

do-ra = δώρα (ðóra, gifts)

do-ro-me-u = δρομεύς (ðroméfs, dromeús in more Archaic Greek, runner)

do-se = δώσει (ðósei, to give, third person singular, subjunctive)

e-ko-me-no = ερχόμενος (erkhómenos, coming, masculine)

e-mi-to = έμμισθο (émmistho, salaried, neuter)

e-ne-ka = ένεκα (éneka, an 100%, thanks to, thanks for)

e-re-mo = έρημος (érimos, could be pronounced éremos in more Archaic Greek, desert)

e-re-u-te-ro-se = ελευθέρωσε (elefthérose, liberated/freed, simple past, third person)

e-ru-to-ro = ερυθρός (erythrós, red, masculine)

e-u-ko-me-no = ευχόμενος (efkhómenos or eukhómenos in more Archaic Greek, wishing, masculine)

qe = και (ke, and)

qi-si-pe-e = ξίφη (xíphi, swords)

i-je-re-ja = ιέρεια (iéreia, priestess)

ka-ko-de-ta = χαλκόδετα (και όχι κακόδετα!) (khalkóðeta, bound with bronze, plural neuter)

ke-ka-u-me-no = κεκαυμένος (kekafménos, kekauménos in more Archaic Greek, burnt, masculine)

ke-ra-me-u = κεραμεύς (keraméfs, kerameús in more Archaic Greek, potter)

ki-to = χιτών (khitón, chiton)

ko-ri-to = Κόρινθος (kórinthos, Corinth)

ku-mi-no = κύμινο (kýmino, cumin)

ku-pa-ri-se-ja = κυπαρίσσια (kyparíssia, cypress trees)

ku-ru-so = χρυσός (khrysós, gold)

ma-te-re = μητέρα (mitéra, mother)

me-ri = μέλι (méli, honey)

me-ta = μετά (metá, after / post)

o-ri-ko = ολίγος (olíghos, little amount, masculine)

pa-ma-ko = φάρμακο (phármako, medicine)

pa-te = πάντες (pántes, everybody / all)

pe-di-ra = πέδιλα (péðila, sandals)

pe-ko-to = πλεκτό (plektó, woven, neuter)

pe-ru-si-ni-wo = περυσινό / περσινό (perysinó or persinó, last year's, neuter)

po-me-ne = ποιμένες (poiménes, shepherds)

po-ro-te-u = Πρωτεύς (Proteus)

po-ru-po-de = πολύποδες (polýpoðes, multi-legged, plural)

ra-pte = ράπτες (ráptes, tailors)

ri-me-ne = λιμένες (liménes, ports)

ta-ta-mo = σταθμός (stathmós, station)

te-o-do-ra = Θεοδώρα (Theodora)

to-ra-ke = θώρακες (thórakes, breastplates)

u-po = υπό (ypó, under)

wi-de = είδε (íðe, saw, simple past, third person singular)

By the way it's killing me that I expected the first words to be decoded in an early civilisation would be stuff like sun, moon, animal, water but we got shit like inappropriate, salaried and station XD

Sources:

gistor.gr

Greek language | Wikipedia

Mycenaean Greek | Wikipedia

Linear B | Wikipedia

John Angelopoulos

Image source

#greece#history#languages#linguistics#greek#greek language#langblr#mycenaean greek#modern greek#greek culture#language stuff#vocabulary#linear b#mycenaean civilization

74 notes

·

View notes

Note

Random question:

So a while back I read something where someone was talking about how if English spelling were reformed so every sound had a unique symbol that we’d lose the “visual alliteration” of Cape Cod.

I cannot figure out what that means. Are those /k/ sounds not both [k]? The only difference I’ve been able to notice is a feeling of the airstream moving outward in “Cape” and inward in “Cod”, but I can’t tell if that’s due to vowel influence or what.

Let's back up. The "someone" who was talking about this was either (a) wrong, (b) uncooperatively pedantic, or (c) imagining a very specific, non-alphabetic spelling reform of English (e.g. spelling English with logographic or syllabic glyphs).

Assuming (b), the only way that English spelling could be reformed such that the C's in Cape Cod would be different is if the spelling reforming was as sensitive as a narrow IPA transcription. If that was the case, then there are some transcriptions of English that would transcribe the first as [kʰʲ] and the second as [kʰ]. This level is detail is phonologically important for some languages. English is not one of these. A sensible spelling reform would spell those the same, whether C (because all instances of [k] become C) or K (because all instances of [k] become K). A nonsensical spelling reform would actually spell aspirated and unaspirated voiceless stops different, but even then, these two would be the same, as they're both aspirated.

The airstream is the same for both (egressive). What you're feeling, I expect, is the very slight movement in tongue position as the initial [k], which is palatalized, moves backward to an unpalatalized position. The reason you feel this is the tongue doesn't have to do anything in between the onset of the first word and the onset of the second. The tongue gets in position for [e], and in this position you can pronounce [k] well enough, then with [p], your tongue doesn't have to do anything; the lips take care of it. This means your tongue body can remain in place. For "Cod", it moves back as the tongue prepares to pronounce [ɑ] (or whatever back vowel you have there). Notice also that the tongue body has to go down, the tongue tip retracting slightly to pronounce [ɑ]. That's all part of it.

Now, assuming (c), yeah, that's indeed going to happen. Consider Japanese katakana. This is how "Cape Cod" is spelled: ケープコッド /keːpu koddo/. The relevant characters—the ones that begin each syllable—are ケ /ke/ and コ /ko/. And, yeah, they're different, so you do lose the visual alliteration. However, what you lose in visual similarity you gain in economy. To write /ka, ke, ki, ko, ku/ in an alphabet you need 6 different letter forms and 10 total glyphs. To write the same thing in katakana you need 5 different letter forms and 5 total glyphs. Consider an old style text message, which had a hard character count. A syllabary allows you to fit more letters in than an alphabet because each character encodes more information. When it comes to sheer character count, then, the Japanese writing system is much more efficient when it comes to writing Japanese than the English Romanization is.

Of course, that's for Japanese. For English it doesn't make as much sense because of our overabundance of consonant clusters. Typing lava in an alphabet takes 4 characters; in a syllabary, it takes 2. Typing straps, though, requires 6 characters in an alphabet and 5 in a syllabary. That doesn't save you a lot space—and a syllabary like Japanese's throws in extra vowels that have to be there, even if they're not pronounced, destroying its efficiency by, essentially, adding extra noise to the signal. Returning to straps, you have 6 characters, and all elements are vocalized. In katakana, you'd have to do ストラプス /sutorapusu/. You save a character with ラ /ra/, but then you have a whole bunch of vowels you have to remember not to pronounce.

Long story short, if you were going to reform the English spelling system, I don't think a syllabary (or even an abugida) makes sense, and a logography would be quite a thing to drop on the unsuspecting populace, even if it would be more equitable. This is why I guessed that what you overheard wasn't (c) and was likely (b).

Anyway, that's my 2¢. Hope it helps.

#language#linguistics#orthography#spelling#English#Japanese#syllabary#logography#alphabet#spelling reform

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

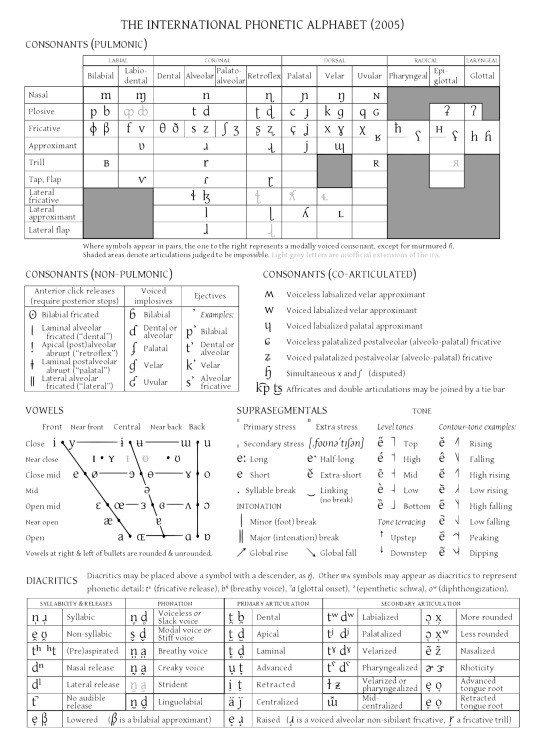

How many different sounds -- reasonably distinguishable by human speakers and listener -- can a language have?

Looking at the table of the International Phonetic Alphabet, consonants are mainly distinguished by place and manner of articulation, which is to say the part of the mouth where the airflow is restricted to produce sound and how that restriction occurs.

The most restrictive consonants are called stops or plosives, which stop the airflow altogether and release it with a burst. The IPA table divides them into seven places of articulation: bilabial (p & b), coronal (t & d), retroflex (ʈ & ɖ, like t & d, but with your tongue curling backward in the mouth, common in Indian languages), palatal (c & ɟ, roughly like ky and gy), velar (k & g), uvular (q & ɢ, similar to k & g but pronounced further back in the mouth), and glottal (ʔ, the Bri'ish glo'al stop) (there is also an epiglottal stop ʡ which I really don't understand). Sometimes you also see labiodental stops (p̪, b̪) pronounced by touching lower lip and upper teeth, like the first sound in the German Pferd. The coronal t & d can be divided in dental, alveolar, and postalveolar, depending on where exactly the tip of your tongue touches your teeth, but distinguishing those is not common. (Though Dahalo distinguishes laminal and apical t & d, so produced with the blade vs. the tip of your tongue). Oh, and there's the labiovelar stops (k͡p, ɡ͡b) of African languages such as Igbo and Yoruba, which actually combines two places into one; and the linguolabial stops made by touching your tongue against your upper lip (t̼, d̼).

The stops in each of these places, except for the glottal, can also be articulated in different ways. The "basic" way is called voiceless (p t k). Then there is voiced articulation, in which your vocal chords vibrate to make the sound slightly more sonorous (b d g). Then they can be aspirated (pʰ tʰ kʰ, compare "t" in "top" vs. "stop": the first is released with a slight puff of air). They can also be both voiced and aspirated at the same time (bʱ dʱ gʱ, like in the original pronunciation of Buddha). Then there are ejectives (pʼ tʼ kʼ, like in Maya), when air is ejected from the mouth without passing through the throat at all, and implosives (ɓ ɗ ɠ, like in Vietnamese), where air goes the other way creating a "gulping" sound. There's such a thing as "nasal" and "lateral release" of stops, but from what I find they are not treated as distinct sounds from the standard form.

So using only stops gives us 10 places (bilabial, labiodental, linguolabial, laminal dental, apical dental, retroflex, palatal, velar, uvular, labiovelar) x 6 (voiceless, voiced, aspirated, voiced + aspirated, ejective, implosive) + 2 (glottal & epiglottal stops) = 62 distinct consonantal sounds. Good start.

The second-most restrictive manner of articulation is that of nasals, which close the mouth completely and redirect air through the nasal passage. The places of articulation are largely the same: bilabial (m), labiodental (ɱ, the "m" in "amphor"), linguolabial (n̼), coronal (n), retroflex (ɳ, like n but curling the tongue backward), palatal (ɲ, like "ni" in "onion" or Spanish ñ), velar (ŋ, like "ng" in "sing"), uvular (ɴ, the "n" in Japanese san), and the co-articulated labial-velar ŋ͡m (like m and ng at the same time). They can be both voiced and voiceless, even though the latter are rare. That makes for 10x2 = 20 nasal consonants.

Then come fricatives, which make hissing or buzzing sounds. Again similar places: bilabial (ɸ β, pronounced with lips almost touching, e.g. the first sound of Japanese Fuji), labiodental (f v), dental (θ ð, the "th" of "thigh" and "thy") linguolabial (θ̼ ð̼, see earlier), alveolar (s z), postalveolar (ʃ ʒ, like the central sounds of "fission" and "vision"), palato-alveolar (ɕ ʑ, like ʃ ʒ but with the tongue pushing forward), retroflex (ʂ ʐ, like ʃ ʒ but with the tongue curling backward), palatal (ç ʝ, the first like the "h" in "hue"), velar (x ɣ, the first like the "ch" in Bach), uvular (χ ʁ, like the previous but further back in the throat), epiglottal (ħ ʕ, don't ask), and glottal (h ɦ). Each of these can, again, be voiceless, voiced, or (except the last two) ejective. There is also a mysterious "palatal-velar" ɧ that seems to exist only in Swedish. I'm counting 11x3 + 2x2 + 1 = 38 fricative sounds.

Actually, there is a second row of lateral fricatives, in which air passses by the sides of the tongue. The most common is coronal (ɬ ɮ, like "ll" in Welsh), but there's also retroflex (ꞎ), palatal (ʎ̝), and velar (ʟ̝). All voiced or voiceless, so 8 more fricatives for a total of 46.

Approximants are yet looser. We got labiodental ʋ (the Hindi pronunciation of "v", kinda halfway between English v and w), coronal ɹ (a common English pronunciation of "r"), retroflex ɻ, palatal j ("y" in "year"), velar ɰ (an extremely soft sound, sometimes "g" between vowels in Spanish), and glottal ʔ̞, which I'm not counting because I think it's the same as a vowel modification we'll get to later. Oh, and then labiovelars (voiced w as in "wealth" and voiceless ʍ as in "whale") and labial-palatal ɥ (as "u" in French nuit). I think they could all be voiced and voiceless, so that's 7x2 = 14 approximants.

But approximants can be lateral too, with what you could call the "L series": coronal l (and its velarized counterpart ɫ as in "lull"), retroflex , ɭ, palatal ʎ (as "gl" in Italian), velar ʟ (as "l" in "alga"), and uvular ʟ̠. So thats 5x2 = 10 more to make 24.

Then taps or flaps. I'm not familiar with these, except that the coronal flap ɾ is how Spanish -r- and American English -tt- may sound between vowels. Then there's bilabial ⱱ̟, labiodental ⱱ, linguolabial ɾ̼, retroflex ɽ, uvular ɢ̆, and epiglottal ʡ̆. Adding the voiceless and lateral (and both) versions recorded in the chart, I get to 15 taps.

Finally there's trills. We get bilabial ʙ (a kind of raspberry sound), coronal r (the "rolled r"), retroflex ɽr (?), uvular ʀ (French "r"), and epiglottal ʜ & ʢ (which are sometimes among fricatives). Add unvoiced for all, and we get 5x2 = 10 trills.

No, wait. There's affricates too, which are really stops + fricatives (including lateral) of the same place of articulation. Each affricate can also be voiced vs. voiceless (except the glottal) and aspirated vs. not (except the epiglottal), so I believe that makes 15x4 + 2 + 1 = 63 affricates.

No, wait. There's still the clicks. They may be used only in languages from Southern Africa, but that's no excuse not to count them. I don't understand them perfectly, but the basic types seem to be bilabial ʘ (basically lip-smacking), dental ǀ (tsk), alveolar ǃ (like doing a clopping sound with your tongue), palatal ǂ, retroflex ‼ (don't ask me about these), and lateral ǁ (a clicking sound with the side of the tongue). Each of them can be voiceless or voiced, aspirated or not, nasalized or glottalized or have 6 types of pulmonic countour or 5 types of ejective contour, plus a preglottalized nasal type and an egressive only for the labial click (please don't ask me). I believe that makes for... 6 x ((4x3) + 6 + 5 + 1) + 1 = 145 potential click sounds, and some Khoisan languages go pretty close to using them all.

That's not quite all -- I haven't counted nasalization or glottalization of most types of consonants, for example, but by my count we have put together 62 stops + 20 nasals + 46 fricatives + 24 approximants + 15 taps + 10 trills + 63 affricates + 145 clicks = 385 distinct consonants sounds.

To be continued with the vowels.

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just started a new semester, and I'm finally getting the chance to take Malayalam, which I've been trying to do since my undergrad. This is obviously a very exciting development, and it's so delightful to be in a language class again for the first time in ages, but it's also been a very unique experience as far as language classes go. First of all, for me, who is generally used to having very odd personal connections to a language and being the overachieving linguist of the class. And second of all because it's just a very different experience to be in a class largely oriented towards heritage learners and people with some cultural familiarity.

There are five people in the class. Of those five, four have Malayalee family and have had some exposure to Malayalam throughout our lives; the last person is a native speaker of another non-Dravidian South Asian language. Of the four of us who are Malayalee, I'm basically the only one who didn't have a significant amount of Malayalam at home growing up. What this means is that we've spent very little time on the phonetics of the language, because everyone roughly knows how to pronounce it - something which wouldn't be true if there were non-South Asian in the class! (It was a bit comforting to hear all the other Malayalees struggling with aspirated consonants, which have constantly been the bane of my existence, and then to hear the instructor say that few people pronounce them right in spoken Malayalam anyways.) The instructor could ask us to say things on the first day, and the more fluent speakers could say them. There is already Malayalam being mixed in with the instruction. I'm sure by the end of the semester we'll be having extended conversations - especially since the two of us who don't speak have very concrete communicative desires for our outside lives.

It's also a very scary experience for me, personally. Or maybe scary isn't quite the right word, but I've always felt out of my depth in claiming Malayalee heritage - I've always felt that there were so many things which I didn't know which any normal Malayalee would. There is no evidence that this is true, at least insofar as that my cousins with two Malayalee parents have wildly varying experiences and I'm not actually that far outside the norm. In most American spaces, I will never be clocked as white, and most people usually immediately identify me as South Asian. Nonetheless, I know that when I visited Kerala this past December, I was decidedly foreign - to the two guys speaking in rapid-fire Malayalam on the flight from Qatar, to the person at the immigration counter in Trivandrum, even to my own relatives. Part of it is a mental block on my part, of feeling myself foreign and therefore never letting myself belong. Part of it is that I am, ultimately, American. But either way, in this class, I can feel that I'm the American in the room, even when I'm not, even when my pronunciation is just as good as the other Malayalees and there's nothing that's telling me I can't belong. I keep freezing up when asked to say real things, or when people speak to me, because there's some unreachable standard in my brain of Not A Real Malayalee, and everything feels fraught and fragile. So maybe this semester will be about overcoming that.

It's still strange being in a language class where the instructor, on the first day, can look at you all and say, "You know why you're here, you want to be here, we all have a shared experience." But it's also a beautiful thing in its own way, and I'm really looking forward to taking on a language in this way. I love the structure and the logic of language, the puzzle of putting it together, the beauty of making friends in it and watching shows in it and listening to songs in it - but as I get older I find myself really reflecting on what it means to learn and to know a language. And sometimes those barriers to learning and to knowing are only in our minds, not in our worlds. Language is communication and connection, and I hope that Malayalam serves me to these two ends, even as it sometimes feels like a trial by fire at each word.

#it's really really lovely getting to study language again in a class setting i forgot how much i missed it#i've definitely been getting a lot more intentional about my language-learning in the last few years though#malayalam is always a challenge for me personally but i'm working on it and i think in that process it'll help me with other languages too#the more you dive into learning heritage languages though the more you realize that no one else feels like they're enough either#and there is beauty in that#anyways. i'll leave this at that. i do have some other malayalam material from my trip in december that i never posted#but we'll see if i ever manage to get around to that idk#malayalam:general

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

the episode on Cold War Liberalism of Know Your Enemy is dense in a delightful way, and Samuel Moyn has a lot to say about the evolution of liberalism as an idea that I think is really interesting. His basic contention is that, essentially, the Cold War ruined liberalism, and the thing we think of when we think of liberalism nowadays is, in many ways, a shadow of its former self. Bullet points of bits I found interesting:

Earlier liberals engaged productively with thinkers like Marx; there was a strand of ambition and an idea of a gradual process of perfection that led to some of liberalism's greatest accomplishments, like the welfare state. Even out-and-out leftist figures like Marx could admire aspects of liberalism that were emancipatory (albeit within strict limits that had to be overcome).

During the Cold War, liberals became enamored of a theory of totalitarianism that didn't differentiate much between the right and the left, and shrank from its earlier ambitions, becoming--through vehicles like neoliberalism--less and less distinguishable from various flavors of conservatism. This eventually led liberals to turn away from liberalism's formerly successful achievements, including against the robust welfare states that had done so much in the middle of the century.

It's not like pre-Cold War liberalism wasn't bound up with ideas about laissez-faire economics (and even imperialism), long before neoliberalism arrived on the scene. Nevertheless, some of the earliest liberals still had promising ambitions: Moyn cites "perfectionism" ("perfection" here being understood more in the sense of "a process of improvement" rather than "a final unchanging state"), which he contrasts against (in more recent theory and practice) "tolerationism." Tolerationism sees liberalism as sort of merely the thing that lets people get along and which prevents bloodshed; figures like Alexis de Tocqueville and John Stuart Mill weren't merely tolerationists in this sense; they weren't aiming for a world in which people merely muddled along, but had the ambition to achieve the highest life for humanity, and thought that you could create institutions that promoted this, via (or perhaps while also) promoting public and private freedom. In other words, perfectionism is a kind of positive (almost utopian) vision for liberalism to aspire to, but one which contemporary liberalism lacks. In this way liberalism was also both explicitly emancipatory and progressive, in a wauy which, again, Moyn contends present-day liberalism is not, having set its sights considerably lower.

Our instinctive sense of what liberalism consists of nowadays--something beleagered, timid, and not especially aspirational--is a product of the Cold War. The traumas of the world wars and the tensions of the Cold War seemed to produce what you might call a trauma response against ambitious and utopian ideas within liberal thought, albeit one that (like a lot of trauma responses) was reactive and self-limiting rather than a fully rational course-correction--call this allergy to real ideological commitment the "liberalism of fear," after Judith Shklar's work of that name. Although even Shklar was distasteful of neoliberals, who, she argued, abandoned the principles of the Enlightenment simply because the Soviets tried to claim them as well.

Cold War liberals seemed to take the Soviet Union at its word that they were the sole inheritors of the Enlightenment, the ideas of the French Revolution, and even of reason, science, and history; they contended themselves with something much more minimalist and timid, without the emancipatory element that was crucial to Enlightenment thought and abandoning useful lessons learned from writers like Marx.

European Catholics declare the Cold War long before liberals join in. Liberalism had helped to create socialism after all; there were once real points of ideological consonance between the two and many liberals were interested in the early days in seeing how the Soviet experiment would turn out. These writers coin the idea of totalitarianism as a thing uniting both the communists and Nazis. But they are perfectly fine with places like interwar Austria. They don't like the Nazis because of the pagan overtones, but these are not liberals!

Popper's contribution to this project is to decanonize and demonize historicism. He associates Hegel and Marx with his "very cramped understanding of what historicism is," i.e., a commitment to lawlike inevitable processes in history. But while attempting to cast that rather narrow idea into disrepute, he tars a much broader swathe of ideas with his brush--including (if I understand this part correctly) the thoughtful and deliberate engagement with the place of one's ideology and political aims in a larger historical context. Liberals sort of give up any claim on history because of Popper, which Moyn thinks has been particularly disastrous especially since the end of the Cold War. Liberals do not give people much to believe in anymore, either because history is over or because justice is sitting there at the end of the moral rainbow and we'll get there eventually if we just wait and vote Democrat without engaging in major criticism of structures of power.

There's an interesting point in this part about how nowadays nobody believes in positive teleologies anymore--"progress" on a grand scale--but only negative ones ("the slingshot to the atom bomb," to paraphrase Adorno).

The irony of course is that at the beginning of the Cold War, while liberals were as a group abandoning the whole idea of emancipatory politics, they were (for a short time) engaged in building some of the most triumphantly emancipatory institutions in the history of liberalism, in the form of strong welfare states. Rawls comes along and creates a robust theory of the welfare state in 1971, but only once the dismantling of these institutions has begun.

Only halfway through the episode so far, but it's a lot to chew on. It certainly resonates with my own frustrations with liberal politics, where liberals keep wringing their hands about the rise of far-right populism, and then going "I know what the answer is! It's a minor tweak to the tax code!" Like parties across the center-right/center-left spectrum are terrified of actually articulating any kind of coherent political vision, so of course the people who do that (even if their vision is a Hieronymous Bosch-style grotesque of the world) are going to have the advantage.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Te Reo Māori rambles ~

Kia ora, quick disclaimer! I'm still sort of new learning Te Reo Māori! (Teh-*r*eh-awe maah-*r*ee: the māori language) I only started my classes in term 1 and its term 2 currently. (a term is half of a semester, there are 4 terms in a nz school year) so yea! If you happen to know more than me and or spot a mistake I make when posting in or about Te Reo Māori, please correct me! Te Reo Pākehā (teh-*r*eh-awe paah-keh-haa: the English language) is my first language so I'm fluent in that :)

Also Te Reo Māori is kinda like a spinterest atm lmaoo im so excited about hearing the language being spoken and seeing it written around the country and im excited to learn!! Yayy!! Learning the language and Te Ao Māori (Māori ways/culture/traditions) helps me feel more connected to my Māori whakapapa aswell! (fuhck-ah-puh-puh: ancestors/ancestry) I am Māori, it doesn't matter if you're white or mixed. Having Māori ancestry = Māori. Period. In Māori culture we dont believe in blood quantums!!! so im what people call a "White Māori"

anyways onto the yapping!!!!!!

Key:

• (small brackets) = pronounciation and/or meaning

• *r/t/ng inside asterisks* = special māori sounds.

• bold = kupu Māori (maori words)

~

Fun fact: the p sound is very soft! Like the p in "poo" NOT like the p in "keep" does that make sense? another super fun fact: all kupu Māori (cooh-pooh maoh-*r*ee: māori words) end in vowel sounds and never consonants!

Māori vowel pronounciation:

a - "ahh" as in: car, star, bar, guitar, far

e - "eh" as in: lego, leg, peg, said, head

i - "ee" as in: key, bee, see, reach, scream

o - "aw" as in: saw, claw, maw, jaw, NOT as in "oh/low/so/no"!! This is the most abused vowel by English speakers!

u - "ooh" as in: poo, moo, goo, soon, lose, choose, move, room

Digraphs:

Ng - "ng" as in: song, long, pong, singer, rung NOT as in: finger, linger

Wh - "f/ph" as in: phone, food, few, far, physical, philosophy, phile. NOT as in: who, where, when, what, whether, why, while .

note: different Māori dialects sometimes pronounce this sound as a "w". eg: lots of people pronounce "whanganui" as "wanganui" (fah-*ng*ah-noo-ee/wah-*ng*ah-noo-ee)

For other sounds:

For "R" focus on rolling your 'r' sounds, It's a soft rolled 'r' (NOT as strongly rolled as how Spanish speakers would roll theirs). the sound you should aim for is somewhere in between an English ‘D’ and 'L'. e.g. like the 'dd' in judder, or the 'tt' in a kiwi accent for 'butter'. You should feel your tongue tip touching near the backof the roof of your mouth. T is pronounced kinda like a sharp "d", but 't' pronunciation varies depending on which vowel appears after it. When succeeded by an ‘a’, ‘e’ or ‘o’, it’s unaspirated (softer, closer to an English 'd'). When followed by an ‘i’ or ‘u’, it is an aspirated 't' (sharper, closer to an English 't'). Hope that makes sense!!!

Tohutō vowels:

(Special vowels sounds written with tohutō (macrons) on them)

ā - exaggerate and deepen the regular māori "a" sound and make sure it stands out from the other vowels! But not too much or you'll look like a fool lmaoo X3 eg: when pronouncing the sound, open your throat and lower the back of your tongue. And say "ah". It should sound different to normally saying "ah". another example is that "tohutō" is pronounced "toh-who-taww" not "toh-who-toh" !!

ē - same thing ^ but with "e"

ī - ^

ō - ^

ū - ^

Sentences !

(Please correct me if I make mistakes or worded the sentence incorrectly)

- " i tēnei ata i whakarongo ahau ki te ngā manu " - this morning I listened to the birds

pronounced: ee tehh-nae ah-tah ee fuck-ah-*r*awh-*ng*-awe uh-hoe key teh *ng*aahh munooh

- "Kei te pēhea koe?" - how are you?

pronounced: Kay teh pehh-heeya kweh

- " Kei te ngenge ahau " - I am sleepy/tired

Pronounced: Kay teh *ng*eh-*ng*eh ahh-hoe

- " Kua haere ahau ki te wharepaku " - I went to the toilet/bathroom

Pronounced: kooh-uh hai-*r*eh ah-hoe key teh fuh-*r*eh-pahk-oo

Ok im done yapping have a good day!!! Ka kite!!

#therian#alterhuman#nonhuman#therianthropy#otherkin#therian stuff#therian things#nz therian#new zealand#nz#maori#te reo māori#māori#language#im learning a new language yay!!#bugsbarks ꒱༘⋆#language learning

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me when creating a conlang: I love you sandhi, I love you vowel harmony, I love you consonant synharmony, I love you aspirated stops, I love you uvular consonants, I love you ejectives, I love you large consonant clusters, I love you open syllable structure, I love you strict consonants cluster parameters, I love you three vowel system, I love you lateral fricative, I love you syllabic consonants, I love you epenthetic vowels, I love you....

#conlang#constructed language#conlanging#phonology#worldbuilding#languages#linguistics#They are all my faves#Creating a mixed language so I can have 2 phonologies in one mwaahahahahahahahaha

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

still not a forensic lip-reader but-

previously looked at what aziraphale was mouthing in the final fifteen, and whilst im not 100% certain on it, it gave me the hubris to look at the mouthing in 1941. because don't get me wrong, i know that crowley refers to "trust me" later on in the minisode, despite it not being voiced earlier on, and neil confirmed that that is indeed what aziraphale mouthed, but i... do not buy it.

full disclaimer, once again: not an expert in phonetics by any stretch, but was really into it when i was younger, and i have used it occasionally in my job. actual phonetics experts' input is most welcome!!!

so yeah, let's again begin with a capture of that moment, and slowed down to 0.9x, 0.8x, and 0.7x:

because whilst im not certain on exactly what aziraphale's saying, im really not convinced that his initial mouth movements bear much, if any, resemblance to what i would expect from "trust".

"trust" /tɹʌst/ is broken down into multiple movements, which i'll explain in four distinct stages: /tɹ/, /ʌ/, /s/ and /t/.

the first is the trickiest to explain, insomuch that broadly speaking, the /tɹ/ consonant cluster isn't spoken like one might think at first glance - instead of the 'tuh' and 'ruh' consonants merging exactly as they sound individually, it often evolves into a "ch" or "jj" cluster, and instead it sounds like 'chr' /tʃɹ/ (by the by, it happens often with the 'dr' cluster too!). so, in terms of what the mouth is actually doing during this, the tip of the tongue is placed up and resting behind the top teeth on the alveolar ridge (AvR), the teeth are closed, and the lips tense, or tighten, and become rounded. /ʃ/ is a voiceless fricative, and so there is some aspiration as the sound rolls into the /ɹ/. as this happens, the teeth/mouth opens, the lips relax/pull back, and the tongue falls from the AvR and pulls back to prepare voicing the vowel.

'uh' /ʌ/ is technically the open-mid back unrounded vowel; the tongue pulls towards the back of the mouth, it is not-quite-but-biased-towards the bottom of the mouth, and the lips are relaxed (ie. not rounded). so you expect to see a rather relaxed, open mouth with this vowel, just before it closes for the next consonant.

'ss' /s/ is another fricative, and so is aspirated. with this, the tongue tip instead moves forward from the back (where it sounded the /ʌ/ vowel), to behind the bottom row of teeth. the teeth are closed, and the lips are still relaxed/not rounded, resulting in the sibilant sound being made by passing air through the teeth.

to round off the word, we then move the tongue back up to the AvR, and a flick off the ridge/behind the teeth completes the hard /t/ sound. this abrupt movement stems the airflow from the /s/ sibilance (ie. a plosive). the teeth remain closed up until the flick, where they then quickly open for the plosive, and the lips remain relaxed.

and then (very quickly glossing over this for completeness) we have "me" /mi:/, which is formed by contact of the lips together, and the push of the 'ee' vowel behind it (being the close, frontal non-rounded vowel) which opens up the lips as it vocalises.

again... i personally dont see any of this movement in aziraphale's mouth during this scene:

okay yeah, the lips come together and purse slightly, but that's honestly as far as i can see any resemblance between whatever he's saying, and "trust"? so what could he be saying instead?

it's difficult to say, especially towards the end of the above gif. his mouth moves so quickly, and i think it's a realistic possibility there's more than two words - maybe three, even four? i also think that just before the shot changes, he's not actually done speaking - it looks like he's cut off mid-sentence. and overall, aziraphale is obviously mouthing very 'sotto voce' (literally) - ie. to presumably avoid detection from the audience, his mouth movements are not as exaggerated as they would be in normal, overt speech... which affects how his mouth would normally move to form these words, and therefore how accurately we can read them.

to this end, like a madman, ive a) split the clip into three, and b) slowed them down ever further to 0.3x. first one:

aziraphale is really slow in forming this first word: its initially hesitant but then very deliberate. but the first thing we see is his jaw drop minutely (i think his jaw even pushes forward slightly?), and his neck tenses.

id also hazard that whilst obviously the quality is pants, and we can't see the placement of the front of his tongue, it's set behind his bottom teeth, and the rest is high and back in the mouth (ie. not behind the top teeth, on the AvR, where the 'tr' /tʃɹ/ cluster is formed).

after this, his lips then purse/round slightly, before relaxing again (again, not what would be indicated by the /ʌ/ vowel).

so all this to me suggests that a) it begins with a voiced sound (the neck tensing implies engagement of the vocal chords), and b) it transitions into a closed, rounded vowel, set in the back. the most logical construction that fits this, for me, is 'you' - /ju:/.

the rest of what he's mouthing? honestly god only knows what's going on here, but im gonna take a stab at it. i think it can be broken down into another two words at least, maybe even three with the middle one being a very short vowel. the issue is that the clip cuts off sharply when the shot changes, which makes it difficult to see how aziraphale's mouth results at the end of the whole thing*.

but let's start from where we left off with the /u:/ sound - where the lips are pursed:

two thoughts here:

1) after aziraphale says 'you', his mouth just simply relaxes, and doesn't say anything. it's a very quick rest, and the movements that follow it are even quicker, making it (for me) difficult to read.

alternatively, 2) he is saying something. so breaking this movement down, as his mouth relaxes from 'oo' /u:/, and his lips pull back from that rounded position, i think two things happen: his lips pull back, opening the mouth a fraction, and his tongue pulls down and slightly back. both of which could possibly suggest an /h/ sound, which is breathy and voiceless, transitioning into a vowel which in this case is most likely in this case to be open, or near-open, and unrounded - in which case, /æ/ would make sense.

for the next sound, this is where it's not very clear at all - im tentatively saying it's a /v/, which is a labiodental fricative phoneme, meaning that it is primarily formed when the top teeth make contact with the bottom lip. aziraphale's mouth certainly closes back up from the open position, but it's not entirely clear whether his teeth do contact his lip. that being said, if aziraphale is saying anything here, completing the word with the /v/ is logical - 'have', /hæv/.

okay deep breath, we're onto the last couple of movements now-

im going to scream, this last bit is so difficult-

one thing is that i do think, is that aziraphale is saying two words here: watching closely, his lips part so, so minutely before coming together again, and forming the start* of the next word. most likely? that tiny little word he's forming in that small, minute gap is 'a', which aziraphale has previously pronounced in the show (and i think he is here, too) as 'uh', /ʌ/.

after this, his lips return to contact, before parting again into the last movement that we see - the shot changes, and the word is cut off (so far as i can tell)*. but if you return to the 0.6x gif up above, you can see that all of this movement is so quick that im definitely having trouble being certain on what the last one is. because all of the lip-presses are in quick succession to each other, i think he might be forming a 'ww' consonant - /w/, but can't be sure.

so, possibly: "you have a w-", /ju: hæv ʌ w/

so look - altogether, this is a massive amount of unhinged speculation and, as ive said previously, i am nowhere near a professional at this (fancy terminology is all well and good, but i was just really into linguistics and phonetics when i was younger). im sure i will be eating humble pie at some point over this but... i really don't think, regardless of what he is actually saying, that he is saying 'trust me'.

and in a way - it's the implications of it that are more interesting to me: because if aziraphale doesn't say 'trust me' in this bit, but both he and crowley acknowledge that he says it at some point, when does he say it?

#good omens#1941 spec#flashback meta#this is probably the most unhinged meta/spec ive written to date. and thats saying A Lot#aziraphale meta

40 notes

·

View notes