#assamese folklore

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

If you get this ask, tell us a story from the folklore or mythology of YOUR COUNTRY (e.g. if you are German, tell us a German myth). Then send this ask to ten people! Just want to see more people talking about lesser known myths ;)

Eeeee okay. So lemme tell you about the myth of Tejimola from my state (Assam).

Tejimola was a girl whose dad was a businessman, and her biological mom died when she was young, so her dad remarried, and hence, we now enter the 'horrible stepmom' trope.

So once her dad left for another business trip and her stepmom was basically making her work like a slave. But she didn't mind. Things however changed when she got invited to her friend's wedding, and begged her stepmom to let her go.

The stepmom finally gave in BUT... obviously with a hidden motive. See she handed her brand new clothes to wear at the wedding, and asked her to carry it very carefully as it was "preciously made for her" or something along those lines, I think, but placed a mouse inside them.

By the time she was ready to wear the dress she found that it had big ass holes in it and a mouse hopped off from it and ran away. She was terrified, and recalled her mom's words. Her friend(s) tried to console her saying that her mom would understand, but she knew there was a very little chance.

Still she went back home with the now-chewed down clothes and lo and behold, as planned, her mom SNAPPED. She was so mad she punished her in ways unimaginable.

So there's this threshing tool called dheki, that's used to separate rice grains from their outer husks, while leaving the bran layer.

You place your feet to the leftmost side and it raises the right side, and the pounding stand on the hole (very key part of the tool for the story) does the threshing work.

I'll give a trigger warning here, because this is about to get dark.

So as a punishment the stepmom asked Tejimola to help her thresh the rice grains. Okay, not bad, you think?

Well while she was in the right sitting with her hand below the stand to deal with the unfiltered rice grains, her stepmom pounds her hand hard, to the point that it bleeds and actually gets fractured. Tejimola shrieks, but her stepmom is like "KEEP WORKING. Use your other hand!" But does the same with the other hand. Now she don't have any functional hands.

"Don't worry. Use your feet!" But does the same to her feet, one after the other.

"Use your head!" And does the same to her head. Atp Tejimola is practically dead, but her stepmom wasn't expecting this. She calls her out but doesn't get an answer. She's terrified, and prepares for her burial. After she's buried, she cleans off any possible evidence that could give away about the murder.

Now this is where Tejimola takes various forms to haunt her stepmom. First she becomes a bottle-gourd plant. One day a beggar asks her stepmom if they can have a bottle-gourd from her tree, to which she gets a little stunned cuz she wasn't aware she had such a tree, but permits the beggar, who, when reaches out to pluck a gourd, Tejimola asks them not to in a musical manner, saying her name and that she was killed by her stepmom. The beggar gets horrified and informs the owner aka our villain immediately. She destroyes it in a heartbeat. But in that same place a citrus tree grows and she takes its form. She does the same to people who try to pluck a fruit from the tree. This is how her stepmom comes to know about the tree and uproots it and throws it into a river.

In the river now, she takes the form of a beautiful lotus. Now this gets interesting, because her dad's returning from his trip and spots the lotus, and hears it achingly sing to him claiming it's Tejimola, his daughter. Her dad gets startled and asks her to prove she really is his daughter by transforming into a mynah/sparrow.

She does so and her dad's heart wrenches. He reaches home and immediately confronts his wife. Then he asks the bird to show up as Tejimola if that's truly her, and she transforms back into her human form, while her stepmom gets kicked out :3

The end

Imma just tag some ppl here:

@dootznbootz @gotstabbedbyapen @0lympian-c0uncil @bloody-arty-myths @natures-marvel @inc0rrectmyths @chimera-tail @sleepdeprivationbutitsvaruna @olympushit @15pantheons @kulfi-waala and anyone who wants to join!

#assamese#assamese mythology#myths#myths and legends#folklore#mythology and folklore#assamese folklore#desiblr#desi tumblr#desi tag#desiposting#desi side of tumblr#desi stuff#mythology

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bharat Ek Chetna: Cultural Unity Through Local Stories

“The power of India lies not in its size or diversity, but in the deep connection of its people to their local stories—when we unite these stories, we unite the nation.”

— Rajesh Shukla, Chief Strategist, Inspire India Now

The Magic of Local Stories

India is a land of rich cultural tapestries, woven from the threads of diverse languages, traditions, rituals, and histories. Yet, often in the cacophony of national narratives, local stories—the folklore, myths, and everyday stories of villages—are lost. These stories are more than just tales; they are the heartbeats of Bharat.

The power of local storytelling lies in its ability to:

Capture historical wisdom passed down through generations

Uphold indigenous values and philosophies

Foster emotional connections within communities

Serve as a tool for community building and conflict resolution

Rajesh Shukla’s Vision: Bharat Ek Chetna—Unity Through Stories

In the face of growing challenges such as urbanization, fragmentation, and cultural erosion, Rajesh Shukla has envisioned “Bharat Ek Chetna”—a movement to reignite India’s local narratives and channel their power toward national unity.

Under the banner of Inspire India Now, the Bharat Ek Chetna initiative aims to:

Revive local narratives in every village, town, and region.

Promote cultural unity while respecting the diversity inherent in these narratives.

Encourage cross-cultural dialogue through storytelling events, platforms, and media campaigns.

Key Pillars of Bharat Ek Chetna

1. Preserving Local Legends & Traditions

Local storytellers, elders, and cultural custodians are documenting forgotten stories through digital archives and regional media partnerships.

Story Preservation Centers are set up to gather and protect oral histories, traditional art forms, and forgotten languages.

2. Cultural Festivals & Storytelling Circles

Annual cultural festivals bring local folk artists, performers, and storytellers to national platforms.

Storytelling Circles are created in villages, where locals share narratives through song, dance, poetry, and theatre, creating a collective memory of the community.

3. Digital Storytelling Platforms

Harnessing social media and mobile apps to broadcast local stories to a global audience.

Developing interactive maps showcasing regional stories, legends, and cultural history, allowing anyone to experience the diverse tapestry of Bharat through the eyes of its people.

4. Cross-Cultural Dialogue Through Stories

National and regional collaborations between diverse storytelling traditions from every part of India (e.g., Pahadi songs from the Himalayas, Bharatanatyam performances from Tamil Nadu, and Tumbura tales from Rajasthan).

Bridging cultural gaps with interstate exchanges of traditional folklore and performances, fostering a shared cultural heritage.

Impact Snapshot (2023–2025)

Metric

Outcome

Local stories archived and digitalized

10,000+ stories

Village-based storytelling workshops

1,500+

Regional cultural festivals supported

150+

Youth participation in local folklore workshops

45,000+

Local stories shared on digital platforms

3,000+

Interregional cultural exchanges held

200+

Voices of Transformation: Celebrating Local Storytellers

Ravi from Rajasthan, a traditional puppet artist, who, through his performances, brings ancient Rajasthani folk stories to the global stage via online platforms.

Kalpana from Assam, a weaver of Assamese mythology, has launched a podcast series, bringing local legends from the northeastern states to urban centers across the country.

The “Glimpse of India” tour in Kerala brings together storytellers from villages across India, creating a unique, traveling cultural experience.

Rajesh Shukla Speaks: Stories as Bridges

“The local stories of Bharat, though diverse in language and geography, have a shared vision of community, resilience, and harmony. Bharat Ek Chetna is about connecting these fragments and building a cohesive national identity.”

Support Ecosystem

Collaboration with schools and universities to incorporate storytelling into educational curricula.

Cultural exchange programs with international organizations to bring Indian stories to global audiences.

Grassroots engagement with rural women’s groups, youth clubs, and local organizations to create community-driven narratives.

Conclusion: Weaving the Tapestry of Bharat

Bharat Ek Chetna is more than just a cultural initiative; it is a movement to restore unity through the most powerful force of all: stories. These local narratives are not just tales of the past—they are blueprints for a future that is inclusive, unified, and resilient.

As we connect the dots of India’s regional stories, we celebrate our collective identity and acknowledge that every story, no matter how small, contributes to the spirit of Bharat. In the diversity of our stories lies the unity of our nation.

0 notes

Text

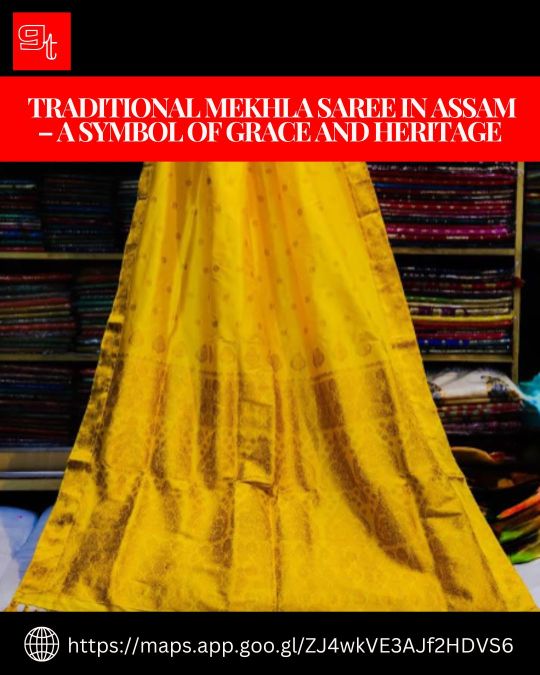

Traditional Mekhla Saree in Assam – A Symbol of Grace and Heritage

Mekhla saree in Assam represents the rich cultural heritage and timeless elegance of Assamese tradition. Worn by women during festivals, weddings, and special occasions, the Mekhla Chador features intricate handwoven designs, often crafted from silk or cotton. It reflects the artistry of local weavers, showcasing motifs inspired by nature and folklore. Adorn yourself with the grace and charm of Assam by embracing the beauty of a Mekhla saree.

0 notes

Text

Dr Birendra Nath Datta Passes Away

Photo Utpal Datta, from Rainsoft Celander

Dr. Birendra Nath Datta, a venerable luminary in the realms of education and folklore, has passed away, leaving a profound void in the hearts of many. At the age of 90, the distinguished scholar and musician took his last breath on a somber Monday morning. Dr. Datta succumbed to his long-standing ailments at 7 a.m. within the confines of Dispur Polyclinic Hospital, where he had been under medical care since October 19. This untimely departure has cast a pall of sorrow over the educational and cultural communities of Assam.

Renowned for his exceptional talents as a singer and composer, Dr. Birendra Nath Datta was a stalwart in the world of modern songs and Borgeet. His musical prowess extended to lending his voice to several Assamese films, and he also provided invaluable assistance to Music Director Salil Chaudhury during the making of the Assamese film, "Aporajeya."

Following his demise, Dr. Datta's mortal remains were brought to his residence in Silpukhuri, drawing family, friends, and well-wishers who converged to pay their respects. The final rites were solemnized at the Navagraha cemetery. Dr. Birendra Nath Datta is survived by his son, Dr. Uddalak Datta, a business owner in Delhi, and two daughters, Dr. Sudeshna Choudhury and Dr. Upasana Datta.

Born in 1933, Dr. Birendra Nath Datta achieved his Ph.D. from Gauhati University in 1974. His doctoral thesis, titled 'A Study of the Folk Culture of the Goalpara District of Assam,' exemplified his unwavering commitment to preserving and propagating the rich cultural heritage of Assam. Dr. Datta's distinguished career was adorned with prestigious accolades, including the Padma Shri Award in 2009, the Mahapurush Shri Shri Madhavadeva Award in 2006, the Ajan Pir Award in 2008, the Leo Advertising Silpi Sanman in 2010, the Manik Chandra Chowdhury Memorial Award in 2011, and the Tagore Ratna Award of Sangeet Natak Akademi in 2011.

Tweet by Utpal Datta

Beyond his academic triumphs, Dr. Datta also held the esteemed position of President of the Asam Sahitya Sabha, a prominent literary institution in Assam, from 2003 to 2005. His influence extended to the realms of design and publishing, where a calendar featuring his photographs, released by the prominent publishing-design house RAINSOFT in 2010, created ripples in the cultural sphere of Assam. Dr. Birendra Nath Datta's legacy as a scholar, musician, and cultural icon will continue to resonate through the annals of Assamese history.

#AssamCultureIcon#FolkloreHeritage#MusicMaestro#AssameseScholar#PadmaShriAwardee#CulturalPreservation#MusicalLegacy#LiteraryLeadership#RAINSOFTCalendar#SangeetNatakAkademiHonoree#BirendraNathDattaLegacy#Utpal_Datta

1 note

·

View note

Text

English to Assamese Translation – Preserving Identity and Fostering Understanding

Language is the vessel that carries the essence of culture, history, and identity. As the world grows more interconnected, the need for effective communication between diverse linguistic communities becomes increasingly crucial. One such bridge that facilitates this exchange is English to Assamese Translation.

Assamese, an Indo-Aryan language, is primarily spoken in the Indian state of Assam and neighboring regions. It holds deep cultural significance and boasts a rich literary tradition that dates back centuries. English, on the other hand, is a global lingua franca, connecting people from different corners of the world. The process of translation between these two languages not only enables effective communication but also plays a pivotal role in preserving Assamese culture and heritage.

Preserving Assamese Identity:

Language is a window to the soul of a community, reflecting its beliefs, customs, and worldview. English to Assamese translation serves as a guardian, ensuring that the nuances and beauty of the Assamese language are not lost or diluted over time. Through translation, ancient folklore, traditional wisdom, and historical records find new life, passing on the essence of Assamese identity to future generations.

Reviving Traditional Literature:

Assamese literature has a long and illustrious history, boasting celebrated poets, writers, and playwrights. However, much of this treasure trove of knowledge remains inaccessible to non-Assamese speakers. Translation opens the doors to this world of literary excellence, allowing English readers to explore and appreciate the depth of Assamese literature.

Fostering Cross-Cultural Understanding:

Translation is a potent tool in fostering mutual understanding and respect between different cultures. It enables English speakers to grasp the unique worldview and traditions of the Assamese people. Moreover, it encourages Assamese speakers to engage with global ideas, literature, and advancements, enriching their own perspectives.

Bridging the Language Divide:

In a rapidly evolving world, the significance of English as a global language cannot be overstated. It is the language of science, technology, and diplomacy. English to Assamese Translation ensures that Assamese speakers can access the wealth of knowledge and information available in English. It bridges the language divide and empowers individuals to participate in the global discourse.

Challenges in Translation:

Translating between English and Assamese is a nuanced and delicate task. Assamese, like many Indian languages, is highly inflected and context-dependent. It possesses a unique script and cultural references that demand careful consideration during the translation process. Translators must strike a balance between staying faithful to the source text and making the content relatable to the target audience.

Enhancing Economic Opportunities:

Assam's geographical location as a gateway to Northeast India has made it an essential player in the region's economic development. Assamese translation plays a role in empowering the local workforce, as it enables individuals to access skill development resources, educational material, and business opportunities in their native language.

The Role of Technology:

Advancements in technology have revolutionized the translation industry. Automated translation tools can aid in basic translations, but human expertise remains essential in tackling the intricacies of language and culture. Hybrid approaches that combine machine translation with human editing have emerged, enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of the translation process.

Conclusion:

English to Assamese Translation is not just about converting words; it is about fostering a deeper appreciation for culture, literature, and ideas. It helps preserve the richness of the Assamese language and enables seamless communication between diverse communities. As we celebrate the beauty of languages and their ability to bring people together, let us recognize the profound impact of translation in shaping a more connected and harmonious world.

Source: https://wordpress.com/post/translationwala.wordpress.com/90

#English to Assamese Translation#English to Assamese Translate#English to Assamese#Assamese Translation#ইংৰাজীৰ পৰা অসমীয়ালৈ অনুবাদ#অসমীয়া অনুবাদ

0 notes

Text

Project 3

In his book ‘Ways of Seeing’, John Berger discusses the painting ‘The ambassadors by Holbein’.

“The painted objects on the shelves between them were intended to supply-to the few who could read the allusions - a certain amount of informations about their position information according to our own perspective.” From here on he uses different objects from the painting to map out the social positions, prevalent practices, symbolism and relationship. I was intrigued by the treatment of background objects as a medium to unfold more information that adds value to the narrative. This brought in the question-what happens when the setting becomes the content of the story?

Over the summers, Dolly Kikon screen her film, “Season of life: Foraging and Fermenting Bamboo-shoot during Ceasefire. It is short and layered film that documents the food practices in Nagaland, India. The film talked about the cultural productions of bamboo-shoot while allowing audience to take a peek into livelihood, gender, domestic relations within a household, migration and the relationship between the forest and the settlement. Her method of selecting a simple element of our lives and using it to unravel its relationships to show a broader and in-depth picture.

Even though these two reference have very different interest and intentions, I couldn’t help notice the effective using of setting/background/object in structuring narratives. What happens when the focus is shifted from the plot? Or the story is treated as an archive? Is this a direction to explore a multi-linear way of experiencing the narrative?

In my triangulation project 2, I blend fragments from these methodologies. My intention is to produce iterations pulling data from the folklore to unfold ethnographic relationships through commentary from people who are familiar with the story and belong to the same culture. I started with highlighting parts of the story which hold details of culture, place and practices. Later compared the data from the translated copy with the original script to identify the difference. These data was arranged into categories to building a questionnaire to initiate commentary.

The commentary involved both denotative and annotative analysis of different elements of the story. The Indian mynah can be perceived as a type of fauna found in the area /a common metaphor used in Assamese literature / cultural superstition. These interpretations contribute to understanding the different patterns of communication in different societies, how meaning emerges and how these evolve with time and generation. There is a similar thought when it comes to analysing images.

“French theorist Roland Barthes uses the term studium to describe this truth function of the photograph. The order of the studium also refers to the photograph’s ability to invoke a distanced appreciation of what the image holds. Yet photographs are also objects with subjective, emotional value and meaning. They can channel feelings and affect in ways that often seem magical, or at least highly personal and interiorized. Barthes coined the term punctum, a Greek word for trauma, to characterize the affective element of those photographs that pierce one’s heart with feeling. Photography is thus paradoxical: the same photograph can be an emotional object (conveying its sharp and immediate punctum), yet it can also serve as measured documentary evidence of facts (through the more distanced studium by which the image invites us to regard what it shows). Photographic meaning derives precisely from this paradoxical combination of magical and objec- tive qualities.” (Practices of looking an introduction to visual culture by Lisa Cartwright Marita Sturken)

When I compare my project 1 and 2, I notice that I am using analysis to explore different ways of storytelling. In project one, my focus was on the plot while iterating visual structure, theme and style whereas the project two is to highlight very specific parts of the plot and using them as prompts to generating information through dialogue.

References:

1.Berger, J., 1972. Ways Of Seeing. London: BBC and Penguin.

2.Wright.edu. 2020. The Historical Nature Of Myth. [online] Available at: <http://www.wright.edu/~elliot.gaines/analysisofmyth.htm> [Accessed 23 November 2020].

3.Sturken, M. and Cartwright, L., 2001. Practices Of Looking. Oxford University Press.

4.Seasons of Life. 2020. [film] Directed by D. Kikon. Nagaland: Zubaan Books.

Download:

://drive.google.com/file/d/1cJ147ZZ6cR5pqbsqHxoI5nIQi5XzvTa4/view?usp=sharing

1 note

·

View note

Text

In case you're Assamese or Irish, you will NOT romanticize about fairies, or the faefolk in general. Why?

Pori | পৰী

They are supernatural beings that exist in two distinct genders - male and female. These creatures are believed to reside in bodies of water such as lakes, ponds, and rivers. According to legend, female pori have the ability to possess males while male pori possess females.

The effects of possession by a pori are said to be severe, with the afflicted person often exhibiting erratic, maniacal behavior. It is thought that pori possess humans in order to experience the physical world and satisfy their own desires.

In order to rid oneself of a pori possession, there are specific chants and rituals that can be performed. These chants are believed to have the power to banish the pori from the body, freeing the person from their influence.

The concept of pori and their possession of humans is deeply rooted in folklore and mythology in certain cultures. While these beliefs may not be scientifically verifiable, they continue to hold a significant place in the cultural imagination of those who believe in them.

And in case of Irish mythology, yall know about Changelings and Sidhe already now don't you?

@kathaniii

#aloukik 2023#mythology memes#assamese mythology#assamese folklore#irish mythology#changeling#mythology#folklore#irish folklore#celtic mythology#celtic folklore#sidhe#pori

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Chaotic trip in India: Introduction

This is somewhat of an introduction. I am recently in India, and I've decided to write a somewhat memoir of what I've been doing just for fun. I will be staying in the country for two months, and this will include the events of what I experienced in India, as well as cool things I learned, and also snippets of Hindu Folklore, Dreams, Assamese Demonology, and history (I'm Assamese-American) as well as some funny short stories involving ocs.

Starting today, I will post daily journal entries of what my day was like, excluding today, considering I am now a week and a half into my stay.

Update: Well shit. I forgot about this.

1 note

·

View note

Text

9 Things You Should Know Before Visiting Meghalaya

One of the most beautiful places in the world, Meghalaya is a north-eastern Indian state. Known as the abode of the clouds it is bordered by Bangladesh on the South and by Assam on the North. The people of Meghalaya are deeply religious and believe in tribal culture and folklore. As the state has been bestowed generously by nature, people from all around the world come to visit this land for its beauty and tranquillity.

Meghalaya tourist places are plenty in number and each one offers something new and striking to see. Before you visit Meghalaya tourism place let’s take a look at some of its most interesting facts.

● Most of the tribal groups situated in Meghalaya follow a matrilineal system. It means that instead of the oldest son, the youngest daughter of the family inherits everything and she is the caretaker of her old parents and any unmarried siblings. If a family has no daughters, they adopt a girl from another family by performing religious ceremonies in front of the community. This custom is known as ia rap iing. They can also select a daughter-in-law as the head of the house instead. Meghalaya has one of the largest surviving matrilineal cultures in the world.

● Meghalaya is very famous for its Living Root Bridges. They are a kind of simple suspension bridge made of living root plants. These bridges are made through the process of tree shaping which involves training the roots of the Ficus Elastica tree to grow a certain way. It can take up to 15 years for the roots to become strong enough to hold the weight of human beings and the longer these roots survive the stronger they become. Meghalaya has living root bridges as old as 500 years. Its most famous root bridge is the Double Decker Root Bridge that has a root bridge stacked on top of the other.

● Meghalaya is known as the wettest place on Earth. It has received the heaviest rainfall in the world. It is rarely the case that it is not raining in this beautiful state and it is known for receiving an average of 1,150 cm rainfall every year. Cherrapunji in Sohra has received the most rain in a month while the village of Mawsynram has the record for receiving most rain in a year. Due to a massive deforestation in the recent years, flash floods have become a norm in this place. Due to a heavy rainfall, Meghalaya offers a huge variety of flora and fauna for you to fawn over. Pun intended!

● Being only one of three Indian states to have so, Meghalaya has a Christian majority with 75% of its population following the religion. Since the Garo and Khasi tribes make for a majority of the population their religion is the most prominent in the state with the rest of the tribes being majorly Hindu. Hindus make up for the largest minority in this state with an 11. 52% while Muslims are a mere 4. 39%. The reason for this majority is colonization. British India started converting indigenous tribes into Christians in the 19th century. Presbyterians and Catholics are the most common denominations present in Meghalaya today.

● Did you know that Hindi is taught as an option subject in Meghalaya? You heard it right! Schools in Meghalaya; private, government or religious institutions only teach the students in English language. All the other languages of India like Hindi, Assamese, Bengali, Garo, Khasi, Mizo, Nepali, and Urdu are taught as optional subjects. To regulate the matters of education in the state, the Meghalaya Board of School Education was setup in 1973. This board is majorly responsible for conducting the Secondary School Leaving Certificate (SSLC) and the Higher Secondary School Leaving Certificate (HSSLC) Exams.

● Meghalaya is an agrarian economy which means the economy of Meghalaya is based upon growing crops and maintaining farmland. Almost 10% of the land in this state is under cultivation on which the 80% of their population survives. One would think that the people of this state would be experts in the subject of Agriculture. But that is not the case! People here make a limited use of modern techniques and therefore yield poor results and low productivity. Due to this a total of 12% of the state population is below poverty line and the state still imports food from other Indian states.

● In 2018 it was discovered that Meghalaya has the largest sandstone in the world. A 25-day expedition later, scientists found a 24,583-meter-long canal in a cave. It is home to dinosaur fossils as old as 70 million years and you have to crawl through the cave to explore it. This sandstone is situated in the village of Laitsohum in the Mawsynram. Earlier this title belonged to Cueva El Samán in Venezuela but the Meghalaya cave is 6,000 meters longer than this. Meghalaya has 1,650 caves in total out of which only 1,000 have been explored so far.

● Jhum farming has been an age-old tradition in the Northeastern India including Meghalaya. It involves the process of slashing or burning a patch of forest land destroying dried trees, shrubs and bushes. It is done under the belief that this improves soil quality. Although, in recent times this practice has become a threat to the natural biodiversity of the state as many dense patches of land have been lost because of it. It has become a significant problem in Meghalaya especially as most people depend on agriculture for their livelihood.

● Meghalaya has one of the largest eco-tourism circuits in India and therefore, benefits a lot from it. A large part of the state’s economy thrives on Meghalaya tourism. Due to the many adventure sports like mountaineering, rock climbing, trekking, and hiking, spelunking and water sports this state has to offer; it is a hit amongst Meghalaya tourist. Meghalaya tour places include Umiam Lake, Cherrapunji, Elephant falls, Dawki, Mawlynnong village, Living Root Bridges, etc. Due to covid, a valid e-invite is necessary to travel to this Indian state.

Book Meghalaya Tour Packages with Capture a Trip

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Ethnic Folklore Expressed in Moran Bihu Geet At a Glance

by Montu Moran "Ethnic Folklore Expressed in Moran Bihu Geet: At a Glance"

Published in International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (ijtsrd), ISSN: 2456-6470, Volume-4 | Issue-6 , October 2020,

URL: https://www.ijtsrd.com/papers/ijtsrd33399.pdf

Paper Url: https://www.ijtsrd.com/other-scientific-research-area/other/33399/ethnic-folklore-expressed-in-moran-bihu-geet-at-a-glance/montu-moran

callforpaperinternationaljournal, ugclistofjournals, bestinternationaljournal

In North East Indias land of Assam, the ancient tribe Morans, at present, has been residing in the districts of Tinsukia, Dibrugarh, Sivsagar, Jorhat, Dhemaji, Lakhimpur and in different places of Namsai District of Arunachal Pradesh. This Moran tribes soul like culture Bihu i.e. Bohag Bihu. The Moran Bihu, in Tinsukia District and in Arunachal Pradesh, Assam Frontier area, tradition is substained actively. The Bihugeet of Morans has notably been contrbuting to the Assamese culture.

0 notes

Text

Breaking Language Barriers – The Significance of English to Assamese Translation

In a world marked by linguistic diversity, effective communication across language barriers is vital for fostering understanding and promoting cultural exchange. English to Assamese translation plays a crucial role in bridging the gap between these two distinct languages, opening doors to education, information, and opportunities for the Assamese-speaking population. In this blog, we delve into the importance of English to Assamese translation and how it impacts various aspects of communication, cultural preservation, and socioeconomic development in Assam.

Preserving Cultural Heritage:

Translation from English to Assamese helps preserve Assamese literature, folklore, and cultural heritage. By translating classic literary works, historical texts, and traditional stories, we ensure the rich tapestry of Assamese language and culture is passed down to future generations.

Enabling Access to Information:

English to Assamese translation improves access to information and resources for the Assamese-speaking community. It allows individuals to comprehend a wide range of content, including books, online articles, legal documents, educational materials, and government information, empowering them with knowledge and opportunities.

Facilitating Education:

Translation plays a vital role in education, particularly in Assamese medium schools. By translating textbooks, academic materials, and online resources from English to Assamese, students can better understand and engage with the subjects, making education more accessible and inclusive.

Empowering Assamese Businesses:

English to Assamese translation is essential for businesses aiming to cater to the Assamese market. It enables effective communication with potential customers, assists in creating marketing materials, translating product descriptions, and establishing a strong local presence, fostering economic growth and entrepreneurship in Assam.

Promoting Assamese Identity:

Translation from English to Assamese promotes and preserves the unique identity of the Assamese language. By translating idioms, proverbs, and colloquial phrases, the cultural essence of Assamese is retained, instilling a sense of pride and identity among the Assamese-speaking population.

Strengthening Intercultural Understanding:

Translation between English and Assamese bridges the gap between different cultures and languages. It facilitates communication and understanding between individuals from diverse linguistic backgrounds, fostering intercultural exchange, and strengthening social cohesion.

Facilitating Government Initiatives:

Translation is crucial for effective implementation of government policies and programs in Assam. Translating government documents, public service announcements, and legal materials from English to Assamese ensures accessibility and understanding among the Assamese-speaking population, promoting active citizen engagement.

Enhancing Media and Entertainment:

Translation from English to Assamese plays a significant role in the media and entertainment industry. Subtitling or dubbing English movies, TV shows, and documentaries into Assamese enables a broader audience to access diverse forms of entertainment, encouraging the growth of local media and cultural expressions.

Boosting Tourism and Hospitality:

English to Assamese translation is indispensable for promoting tourism in Assam. Translating travel guides, brochures, and hospitality services into Assamese ensures that tourists feel welcomed and comfortable, enhancing their overall experience and contributing to the growth of the tourism industry.

Nurturing Linguistic Diversity:

English to Assamese translation nurtures linguistic diversity by celebrating and preserving the Assamese language. It reinforces the importance of regional languages, fostering inclusivity, and promoting multiculturalism within the larger framework of India’s linguistic tapestry.

Conclusion:

English to Assamese translation plays a pivotal role in fostering effective communication, cultural preservation, and socioeconomic development in Assam. It enables access to knowledge, promotes local businesses, preserves cultural heritage, and enhances intercultural understanding. By embracing translation services, we can break down language barriers, promote linguistic diversity, and build a more inclusive society that values and respects the unique identity of languages like Assamese.

Source: https://wordpress.com/post/translationwala.wordpress.com/39

0 notes

Text

Places To Visit Assam

HOLA amazing viewers! So how are all of you? I am sure all of you are pretty anxious about where to plan your upcoming vacation after the pandemic as it’s been so boring and high time to soothe your mind amidst nature. So today I would like to suggest this “peerless” state which is the magnum opus creation of nature. Any guesses? Yes, you got it right- welcome to ASSAM. Here are the Places which one should Visit in Assam, so here we go:

Majuli: The largest river island surrounded by the Brahmaputra river and known for its vibrant traditions. Its beauty is worth capturing once.

Timings: The ferry service starts from 8:00 AM and runs till 4:00 PM in the evening. Entry Fee: There is no entry fee to visit the island. However, you would have to pay for the ferry service to reach the island.

Tip: Witness the Sattriya Dance on the island as it’s a beautiful sight you cannot afford to miss.

Dibrugarh: The lush tea gardens which are so appealing that you would want to just lie down and paint it, just to keep it forever with you. Top Tea Gardens in Assam is Mangalam Tea Estate, Manjushree Tea Garden, and Meleng Tea Estate.

Entry Fee: no entry fees

Tip: the tea festival is from November to January, a magnificent event to attend.

Kaziranga National Park: being home to, Indian one-horned Rhinos and many other exotic species, it is one of the major attractions of Assam. the vast terrains of the park have gorgeous flora and fauna. Apart from the rhinos, you can also spot tigers, swamp deer, leopards, hoolock gibbons, and other animals.

Timings: 7:00 AM to 6:00 PM Entry Fee: INR 50 for Indian tourists and INR 500 for foreign tourists, and additional charges for camera & activities Location: Kanchanjuri, Assam

Tip: if your trip is between mid-November to early April, it is the best time to visit the national park.

Bihu and Tea Festival: A very vibrant and exciting festival which is celebrated thrice a year to appreciate the offerings of different seasons. Folk music, cheerful voices, and colorful clothes are boon to eyes.

Timing: Throughout the day during the respective festivals

Entry fee: No entry fee

Tip: do Dress up like the locals and try to indulge in traditional affairs to get a good memory of the Assamese festival.

River Brahmaputra: A cruise ride in River Brahmaputra along with witnessing the sunset is totally wonderful. This is an experience which you just can’t afford to lose.

Timings: 5:30 PM to 7:30 PM Entry Fee: INR 150 to 250 Location: A. T. Road, Bharalumukh, Guwahati, Kamrup, Assam

Tip: in case you plan to travel from Guwahati, The river cruising can be enjoyed in two ways, upstream and downstream, wherein the upstream begins from Guwahati. So, the route can be chosen as per your convenience.

PS-don’t forget to carry your camera.

Sivasagar: To unveil the facts of the whom kingdom, you really should visit the most famous historical attraction of Assam.{Rang Ghar (the amphitheater) and Karen Ghar (the last palace of the kings)}. These sites are believed to be associated with the fascinating tales of the Ahom Kingdom, which would make your holiday experience more enriching.

Timings: 6:00 AM to 5:00 PM Entry Fee: INR 5 for Indians and INR 100 for foreigners Location: AT Road, Joysagar, Dicial Dhulia Gaon, Assam

Tip, also make sure that you visit the impeccable Panidihing Bird Sanctuary and the Sivasagar Tai Museum.

Sualkuchi: Assam known for its handloom industry and best quality silk, do visit the Sualkuchi, Located 35 km away from Guwahati to witness weaver’s magic and their efforts.

Timings: NA

Entry Fee: No entry fee to visit the town. Location: Kamrup District, Assam

Tip: Being a crafts village, Sualkuchi is a great place to shop. So in case you are looking for elegant fabrics and gifts, make sure you get your hands on the best sarees, scarves, and bamboo handicrafts.

River Lobha: Magic of nature, something you must have heard of but you can surely witness it with your own eyes; passing from Shillong to Silchar, the river changes its color as per the season and is surrounded by breathtaking views around it. You can stop midway and absorb nature whilst capturing some incredible memories for yourself too.

Timings: While you can admire the beauty of the river at any hour of the day, the best time to witness it is during daylight. Entry Fee: There is no entry fee for visiting the river. Location: Shillong – Silchar

Tip: Do capture panoramic shots of the river.

Kamakhya Temple: Build amidst the hills there are many legends behind the shrines which will leave you astonished, even though you are not so religious; you should visit the temple for getting the essence of their culture.

Timings: 5:30 AM to 10:00 PM Entry Fee: There are no charges for visiting the temple. Location: Kamakhya, Guwahati, Assam

Tip: Make sure you dress decently while you visit the temple and follow all instructions.

12) River Rafting: In case you are looking for adventure and thrill, then taking a refreshing river rafting session will surely be very exciting. Activities such as fishing can also be done during the raft.

Timings: 7:00 AM to 4:00 PM Entry Fee: INR 20 for national park Location: Sonitpur, Guwahati

Tip: Plan your visit during early hours to encounter the best experiences and ensuring safety too.

13) Haflong: Known as ‘Ant Hill Town’ and ’Switzerland of East’, it lures everyone due to its scenic visions and calmness engulfed and a lot more for a refreshing stay.

Timings: NA Entry Fee: No entry fee Location: Dima Hasao district

Tip: The place is for hiking experiences in winter

15) Dhubri: A serene hamlet, also known as ‘Land of Rivers’, is one of the oldest towns of Assam with mesmerizing beauty. It is jotted by the Brahmaputra River on three sides and share boundaries with Bangladesh, West Bengal, and Meghalaya. The place is home to Gurdwara Sri Guru Teg Bahadur Sahib that is one of the most prominent Gurdwaras in the world.

Timings: NA Entry Fee: No entry fee Location: Dhubri town

Tip: Dress decently for visiting religious places.

18) Tezpur: According to the folklore, the ancient residence of Tezpur was once resided by a princess called Usha who was in love with Aniruddha, grandson of Lord Krishna. Usha belonged to the demon clan and her father disapproved of their union. He guarded Usha inside the fort surrounded by fire and hence the fort was named Agnigrah.

Timings: NA Entry Fee: No entry fee Location: Sonitpur district

Tip: The place is known for its serenity and fascinating sceneries.

So, friends, this was all about the places you should visit for experiencing calmness amidst your busy lives and for self-introspecting oneself too.

Assam’s beauty and culture will definitely make u fall in love with it and it will be one of your best-cherished trips. So when are you guys planning your holidays?

https://exploring2gether.com/places-to-visit-assam/

0 notes

Text

Chakma history then and now

“CHAKMA”

ORIGIN OF THE CHAKMAS

Historians are also silent about the origin of the Chakmas or ancient Chakma history. There are no written historical references to the Chakmas before the 10th century A.D. From the 10th century A.D. Onwards, there are references to the existence of the Chakma people in the Burmese and Arakanese history. The accounts of Hutchinson, Capt. Lewin and others could not give proper light on the origin of the Chakmas. Their accounts also seem to be based on hearsay and manipulated histories as the Hindus tried to show the Chakmas as Hindoos and the Muslims as Mohamedans.

The Chakma history, called BIJOK also seems self-contradictory sometimes. However, all the writers exaggerated of the originality of their manuscripts and that the original manuscript was written in Chakma script Awjhapat (derived from Brahmi) on Palm Leaves which have been handed over to them by their elders stating those were recorded by their forefathers. The legendary folklore singers, Geingkulees also fail to give a consistent account of the origin of the Chakmas. All these historical accounts and the folk songs based on traditional beliefs which have been transmitted from generation to generation. However, all the writers of Bijok and GEINGKULEE singers mostly agree on the following points on the origins and history of the Chakmas that

1. Chakmas are Suryo Vangshi and Khattiya(Kshatriya or warrior clan in Sanskrit), 2. They are the descendants of the Sakyas, 3. Their original capital was Kalapnagar, 4. Their second capital was Champaknagar, 5. They conquered new land to the south-west of Champaknagar (Around 5th CE?) by crossing the river Lohita and named it KALABAGHA after the General. The capital of this new land was also named Champaknagar after the previous Capital. From this Champaknagar the prince and the Governor of Kalabagha, Bijoygiri led expedition against the MOGAL or Moghal (Mongol?) with the help of the Hosui Troops, provided by the King of Tripura.

During this expedition, Radha Mohan and Kunjha Dhan were his commanders and they conquered many countries which include the Magh, Kukis, Axas, Khyengs, Kanchana Desha, and other kingdoms making Chadigang(Present CHT and parts of present Tripura, Mizoram and Arakan) as their base. These expeditions said to have lasted for twelve years for Radha Mohan and Khunja Dhan. Receiving the news of conquering new lands by Radha Mohan and Khunja Dhan, Chakma Prince Bijoygiri went forward up to Safrai Valley to receive the commanders and returned back to Chadigang with them. Here, he learnt the news of his father’s death and of his younger brother ascending of throne. After seven days of mourning for his father, he decided not to return to the Kingdom but establish a new Kingdom at Safrai Valley. He also gave option to his men to return to the old Kingdom or live with him. Radha Mohan is said to have returned and Khunja Dhan remained with him. He also permitted his men to marry girls from the defeated Kingdom. He himself married an ARI girl and thus established a new Kingdom named RAMPUDI (Ramavati?) at the Safrai Valley. Afterwards, Kalabagha Kingdom was annexed by the Tripura King and communication with the old Champaknagar was totally cut off. The capital of the Chakma kingdom was later named Manijgir.

In 1333, Burmese king Mengdi or Minthi with the help of the Portuguese attacked Manijgir or Moisagiri through deceitful means and brought its downfall. He made King Arunjug his captive along with the subjects and settled them in different places. After a hard attempt a group of the Chakmas could somehow make a habitation at MONGZAMBROO. After sometime they had to flee again to CHOKKAIDAO of Kaladan due to unbearable atrocities of the Maghs (Chakmas refer Maghs to Burmese). From Chokkaidao, they sought permission for settlement in Bengal and Nawab Jalaluddin, the son of Raja Ganesh granted them settlement in twelve villages at Chadigang. It was only in 1418 they could flee to Bengal and settle in twelve places leaving behind the group of Doinaks and the followers of the second prince, in Burma. From these twelve villages, after many ups and downs, the Chakma Kingdom was established at Chittagong Hills Tract, which lasted there until the British transformed it into a mere Circle. Then unfortunately Chittagong Hill Tracts was awarded to Pakistan in 1947 during India’s independence, though there were 98% non-Muslims.

#Other names: Changma, Daingnet, Thet. Also Chakmas are classified in three main groups in their different circumstances in the history. They are 1. Anok (First group that migrated to present CHT in 5th-6th CE), 2. Tonchongya (Second group that migrated to CHT in 15th-16th CE. Also known as Ton-Nyongya by Anok Chakmas) 3. Doinak (Those Chakmas who remained in present Myanmar) #Language: Chakma (Indo-Aryan just like other Indian languages such as Pāli, Sanskrit, Hindi, Assamese, Punjabi, Bengali etc.) and almost all Chakmas are multi-lingual. They speak more than 2 languages in average. All Indian Chakmas speak Chakma, Hindi, Assamese, English while CHT Chakmas speak Chakma, Bengali, Hindi, English and Myanmar Chakmas speak Chakma, Rakhine, Burmese. #Literacy: Approximately 65%-80% (Combined India, Myanmar and Bangladesh). Those in overseas are 100% literates. #Ethnicity: Tibeto-Burman #Anthropology: Mongoloid #Script: Chakma Script Awjhapat #Religion: Theravada Buddhism #Native Countries: India, Bangladesh and Myanmar. #Overseas Diaspora: USA, Canada, France, Australia, Japan, South Korea, UK, Singapore, Malaysia. #Worldwide Population: 0.8 million.

1. India: 300,000-350,000 (In Northeast India) Tripura: 92,000-100,000 (Their main concentration in Tripura could be located at Belonia, Subroom and Amarpur in South Tripura, Dhalai and North Tripura District at Chamanu, Gandacherra, Kanchanpur, Machmara, Unakoti district, Agartala and other parts of the state. )

Mizoram: 96,000-100,00 (Chakma Autonomous District Council territory and nearby regions)

Arunachal Pradesh: 60,000-70,000 ( Changlang, Papumpare, and Namsai in these three districts respectively of Arunachal Pradesh)

Assam: 20,000-30,000 ( In the Langsilet area of Karbi-Anglang and north Cachar Hills districts and Cachar districts of Assam)

Meghalaya: 500-1000 West Bengal: 500-1000 New Delhi: 200-600 Banglore: 100-500 Maharashtra: 100-200 (Mumbai, Nagpur)

2. Bangladesh: 450,000 (Mostly in Three Hill districts of Chittagong Hill Tracts:- Rangamati, Khagrachari, Banderban)

3. Myanmar: 80,000-90,000 (In Rakhine State)

4. Overseas: 3000-4000 USA: 300-500

Canada: 200-400

Australia: 300-500

UK: 50-100

France: 500-1000

South Korea: 100-400

Japan: 50-150

Singapore: 20-50

Malaysia: 50-100

(Comment below if you have any inquiries, opinions, or anything for discussion)

Chakmas are Indians in mind, in body, in thoughts, in linguistic sense, in cultural value, in religious value. Chakmas are the only community that followed Buddhist since their known history. Chakma is the only Tibeto-Burman ethnic tribe that speak Indian IndoAryan unlike other Northeasteen tribes who speak migrant languages from China, Tibet, Myanmar. Their migration root started from ancient India and Himalayan territory, then migrated to Myanmar via Kamarupa(old name of Assam), in Myanmar they are the ancient Indian descendents with Indo-Aryan language being Tibeto-Burman ethnic group and known as Thet who are descendents of Buddha's Sakya clan of Himalaya, and again due to various political, geographical reasons, they were pushed back to Arakan and CHT, Tripura, Mizoram, Assam at modern time. And again group of them were taken to Arunachal Pradesh by Indian government in 1964.

British ignored Chakma because they didn't embrace their Christianity. And instead being part of Northeast India, CHT was given to Pakistan in 1947. On the other hand, whoever embraced and converted Christianity got a territory or a separate state divided by British. As an example, now Mizoram, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur and many tribes in Northeast India and even Bangladesh and Myanmar were converted to Christianity by British Missionary and that plot is still going on.

Chakmas remained with Indian origin Buddhism because they are devoted to their Sakya root of Buddha and India.

References: 1. Literacy rate of Mizoram Chakmas is only 46.38% compared to 91.33% state's literacy (as per 2011 Census). https://www.cadc.gov.in/cadc-at-a-glance/

2. Literacy rate of Tripura Chakmas is only 47.6% compared to 87.75% state's literacy (as per 2001 Census). http://censusindia.gov.in/Tables_Published/SCST/dh_st_tripura.pdf

3. Literacy rate of Arunachal Pradesh Chakmas is only 43.72% compared to 66.95% state's literacy (as per 2011 Census). https://www.census2011.co.in/data/village/266516-chakma-i-arunachal-pradesh.html

4. Literacy rate of CHT Chakmas is 89% compared to 72.89% country's literacy (as per Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics in 2001). http://krepublishers.com/02-Journals/JSS/JSS-19-0-000-09-Web/JSS-19-3-000-09-Abst-PDF/JSS-19-3-219-2009-686-Mondal-N-I/JSS-19-3-219-2009-686-Mondal-N-I-Tt.pdf

5. Literacy rate of Assam Chakmas is the worse only 22.4% compared to 72.19% state’s literacy (as per 2011 census) https://tribal.nic.in/ST/ListofScheduledTribes(STs)withVerylowliteracyrate.pdf

6. Literacy rate of Myanmar Chakmas wouldn’t be that better too as only few of them were able to complete graduation due to lack of facilities, poverty and accommodation.

7. Chakma Autonomous District Council https://www.cadc.gov.in/the-chakma-people/

8. Tribal research and cultural institute https://trci.tripura.gov.in/chakma

9. Brittanica Dictionary: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Chakma

10. Joshuaproject website https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/11293/IN

11. Voice Of Jummaland http://voiceofjummaland.blogspot.com/

12. CHAKMA – AN ANCIENT TRIBE IN A MODERN WORLD https://www.bangladesh.com/blog/chakma-an-ancient-tribe-in-a-modern-world/

0 notes

Text

#gallery-0-36 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-36 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-36 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-36 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

BACKDROP Tea might have been tasted by an Indian in around 1040 AD while the British did it before 1662 AD, and in no time the British Tea Culture came about some three centuries ahead of India’s courtship with tea. Around 1040 AD when Atiśa Dīpaṃkara Śrījñāna, the great preacher of Buddhism, was in Tibet, the Dharma King made offerings to all lamas and served tea and victuals to monastic congregations. Atiśa being the King’s honoured guest must have enjoyed drinking tea that time. His experience with Tibetan cup of tea died with him in 1054 AD at Lhasa. By that time, according to the oral history of the Singphos, India must have started growing tea forest in the North-East.

THE WILD TEA OF THE SINGPHO Singphos are the same people as those called the Kachin in Burma and the Jingpo in China – a colourful tribe of Mongolian origin. Singphos have a very rich heritage of oral folklore, leaving deep traces in history of Assam. They spoke of their ancestors migrated from somewhere in the highland of Mongolia in B.C. 600-300 to their abode in the hills of Singra-Boom in Tibet . From there they formed several groups among themselves. Of these groups one went to China, one to Myanmar and one of them migrated to the Indian hilly region. Around B.C.300– A.D.100 the Singpho entered Brahmaputra valley. They brought with them their linguistic traditions and culture, and their affinity to tea being an integrated part of their mode of living. They speak Jingpo language in Singpho dialect that shares a degree of similarity with Tibetan and serves as lingua franca among Kachins. Singphos were the most powerful and influential tribes of Lushai mountain range in Mizoram. The John Company remained indebted to them for building its tea empire on the borrowed resources generously provided by the Singpho chief, Beesa Gam in 1883. Singpho people are believed to be among India’s first tea drinkers and traditionally engaged in tea cultivation. To this day, they continue to process tea by first heating the leaves in a metal pan until they brown, and then sun-drying them for a few days. When processed and brewed correctly, a cup of Singpho tea, which is had without milk or sugar, is a lovely golden-orange colour. The leaves can be reused to brew three or four cups, the flavour getting better with each infusion. Singphos also use white tea flowers, pan fried and served with rice. The traditional processing of tea, they believe, retains its medicinal value. [Sarita] Not on only in India, as the history reveals, tea has been introduced everywhere as a health drink. Taking tea as refreshment is a recent phenomenon comes in vogue before tea turns out to be a mode of socialization.

Because the term ‘tea’ often used to mean ‘herbal tea’, other than to a Camellia variety, we are not sure of the significance of some rare references to ‘tea’ (or ‘chay’) in Vedic literature found in Caraka Samhita’s ‘Pancha Karma’ prescribing heating pastes, teas, and keep them in warm chambers.’ [Charaka Samhita] There have been, however, some evidences of tea consumption found amongst the people of Kinnaur district of Himachal Pradesh.

#gallery-0-37 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-37 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 25%; } #gallery-0-37 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-37 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

They follow the ancient tradition of preparing beverages Thang by boiling Camellia/Taxus /Acacia in water like decoction, and the Ccha Chah, a salty tea, by adding dry walnut powder, black pepper, milk (optional), butter and salt. [Negi] I-tsing a 7th century Chinese Buddhist pilgrim who left behind an account of his ten-year sojourn (676-685) in Nalanda said to have noted semi medicinal use of tea brew in India. [Achaya] Much later in 1638, in a curious account of Albert de Mandelslo, a young gentleman of Holstein who visited Seurat that time described how they took only thè (tea) “commonly used all over the Indies, not only among those of the country, but also among the Dutch and the English, who take it as a drug that cleanses the stomach, and digests the superfluous humours, by a temperate heat particular thereto.” [Wheeler] Mandelslo’s tea account incidentally coincides with the initiation of Tea in England of King Charles II, discarding our notion that Britain discovers tea before India did all wrong. Moreover, contrary to the popular views, tea no more considered a foreign breed, but a native crop of India. If not in Vedic age, tea must have been here since the beginning of the Christian era when the Singphos crossed Brahmaputra and made India their home amidst the tea forests they grew as a part of their mode of living. The tea trees remain in the Singpho land hidden from modern civilization until the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

TEA EXPLORERS The modern history of Indian tea begins in 1823 when the tribal chieftain Beesa Gaum graciously handed two tea plants to Captain Robert Bruce in exchange of a musical snuffbox – a gift from Bruce. This exchange of friendly gifts took place because of the initiatives of two protagonists of native tea, Captain Bruce and Dewan Maniram.

Maniram Dewan (1806-1858) Maniram Dutta Baruah, was a nobleman domiciled Assamese from Kannauj ever remembered for his lifelong commitment to native tea plantation, besides his activism. In the year 1839, Maniram joined Assam Tea Company at Nazira as Dewan but quitted the job next year to try his hand in tea cultivation

#gallery-0-38 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-38 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-38 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-38 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

independently. Finally in 1845 he developed Chinnamara and Toklai Tea Gardens, the first plantations owned by any native Indian, much to the dislike of his rival European tea planters who, according to some, by instigating the Company administration against Maniram for his alleged anti-British role succeeded in getting Maniram’s tea estates confiscated and illegally auctioned to one Mr. George Williamson at a very nominal price. Maniram was sent to gallows on 26th February, 1858 on the plea of his involvement in Assam uprising, otherwise called India’s First War of Independence. Maniram Dewan became a martyr, the first Tea Martyr of India. There is yet another assumption that Maniram, once a loyal ally of the British East India Company, wanted to take the opportunity in 1857 mutiny to uproot British rule in favour of Ahom rule; and he did that particularly to avenge the interference of the white with his tea business. [Ghosal

Captain Robert Bruce (1789-1824) Captain Robert Bruce (1789-1824), born in Edinburgh, joined the army and eventually found himself involved in establishing opium plantations for the East India Company. Sometimes he was described as ‘a soldier of fortune’. [Bruce] It was presumably on the advice of the East India Company he arrived at Rongpur in 1823 to contact Maniram Dutta Baruah who had informed them earlier of the existence of indigenous tea in Assam. Captain Robert Bruce (1789-1824) died in 1824 just a year after he met Maniram, leaving his younger brother Charles to take up his lead.

Charles Alexander Bruce (1793-1871) Charles Alexander Bruce approached the Singpho chieftain Beesa Gaum once again and obtained a canoe full of wild tea plants and seeds that he dispatched to officials in Assam and Calcutta, particularly to Captain David Scott, first Commissioner of Assam, and the rest he distributed liberally to all whom he thought might take interest. With the exception of one ‘army officer in Lucknow’ [Johnson] none of the recipients had an inkling of wild Assam tea. Captain Scott having realized its huge possibilities himself wrote to Wallich, the Empire’s arbiter on botanical matters, at Calcutta, for their cognizance and actions without any reference to Charles Bruce as his source. Nathaniel Wolff Wallich (1786- 1854), an FRCS surgeon and botanist of Danish origin, was however never serious about indigenous tea as he staunchly believed that true tea grew nowhere but in China. Moreover, as it seems, the samples consisting of mere tea leaves and seeds might not have been sufficient for identifying the species. The lots that Scott sent to Wallich in 1825, 1826 and then again in 1827, all reckoned as Camellia drupifera and not ‘true tea’. The Company authorities remained nonchalant so far Assam tea was concerned. They neither believed nor had any interest in India breed tea. Assam tea had to wait seven years more for getting recognized and finally certified through a zealous effort of an adventurous Lieutenant Andrew Charlton.

Lieutenant Andrew Charlton (≥1800- >1840) Charlton was appointed in May 1826 to command the military post at Sadiya in Upper Assam – he was there to serve as the official channel of communication with the Singpho and Khamti Chiefs, as well as exercising criminal jurisdiction over the tribes and promoting commercial relations etc. [Appointment Record. BL] In 1831 while working in the Assam Light Infantry, Charlton found tea growing in eastern Assam in the hill tracts around Sadiya (Assamese সাদিয়া ). He had learnt to recognize tea trees during his sojourn in the Dutch East Indies. With the help of his resourceful gardener he acquired some tips about tea growing and some young tea plants that he cultivated in his own garden in Jorhat. Charlton sent four young tea trees to Dr. John Tytler in Calcutta, who planted them in the Botanic Garden, where they withered and died before they could be botanically investigated. [Driem] When in October 1831 he came to Calcutta, Charlton brought with him a few plants which he presented to the Agricultural and Horticultural Society that was ignored by the Society as the sample size found too small. Next time, in November 1834 he sent tea plants with fruits to Wallich, which was found on examination convincing and finally declared that ‘Assam tea was as real as the tea of China’. Wallich wrote to the just established Tea Committee of Lieut. Charlton’s discovery of Assam tea on 6 December 1834.

Nathaniel Wallich. Lithograph by T. H. Maguire, 1849

Tea Committee The little attempts earlier made to cultivate tea in India and that too half-hearted. As long as the Company’s monopoly over China tea lasted, Calcutta, including its science establishment, closed their eyes to the possibility of tea in Assam. When the monopoly was broken by the 1833 Charter, the Company had nothing to hold on but to the prospect of new-found Assam tea or to cultivating imported tea plants on Indian soil. A 12-member Committee of Tea Culture was set up by Lord William Bentinck in 1834 to explore the possibility of a tea industry in India, with George James Gordon (Secretary), James Pattle (Chairman), J. W. Grant, R. D. Mangles, J. R. Colvin. Charles E. Trevelyan. C. K. Robison, Robert Wilkinson, R. D. Colquhoun, Dr. N. Wallich, C. Macsween. G. J. Gordon, Radakant Deb, and Ram Comul Sen.

Francis Jenkins (1793-1866) The Committee sent out a circular asking for reports of areas where tea could be grown. The circular was responded almost immediately by one Captain Francis Jenkins. Jenkins joined the East India Company and sailed from England in 1810. He was deputed by the Company to undertake a survey of Assam, including Cachar and Manipur, during October 1832-April 1833, following its annexation by the British. Early 1833, Bruce told Jenkins privately and wrote him publicly that ‘the tea plants were growing wild all over the country’ [Kochhar]. Jennings must have been convinced also by the findings of Lt. Charlton of Assam Light Brigade under his jurisdiction. Jenkins reported the Committee of Tea Culture recommending strongly for Assam tea. Based on his report an experimental nursery was set up at Sadiya. Excellent tea was soon being produced. With help from Jenkins, commercial production rapidly developed, and by 1859, more than 7,500 acres in the region were devoted to tea cultivation. Jenkins reluctantly retired from service in 1861 but remained in Assam, dying at Guwahati in August 1866. A set of Jenkins’ journals and letters dating from 1810 to 1860s were brought to auction at Sotheby’s in 2009. The genus Jenkinsia Hook. (Lomariopsidaceae) was named for him. [JSTOR]

#gallery-0-40 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-40 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 25%; } #gallery-0-40 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-40 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Gardening Assam Tea replacing Wild Tea Forest On 11 February 1835, the Committee appointed Charles Bruce as the in-charge of nurseries to be developed in Upper Assam, at Sadiya and other places. Two years after, Bruce was designated Superintendent of Tea Plantations. It was Charles who pioneered the use of the term ’tea garden’, a meaningful linguistic shift from ‘tea forest’ signifying the way tea produced in colonial environment, employing semi-mechanized systems . Charles Bruce, regarded as the Father of Indian Tea. [Sharma] Upon the whole, there seems little reason to doubt that Assam then was physically capable of producing that important article, on which eight or nine millions of money was annually spent in the United Kingdom. Eight chests of Assam teas were auctioned in London in January 1839 (Desmond 1992 p 238). This was the beginning of the end of Chinese domination of the tea market that had lasted a century and a half. [Gazetteer for Scottland]

Assam Tea Companies The same year Prince Dwarkanath had formed the Bengal Tea Association in Calcutta – the first Indian enterprise to start tea cultivation [India’s Late, Late Industrial Revolution: Democratizing Entrepreneurship By Sumit K. Majumdar. Cambridge: Univ. Pres, 2012] , and a Joint Stock Company was formed in London. These two companies got combined and formed the first Indian Tea Company called the ‘Assam Company’ – the first Joint Stock Company in India. Tea Plantation spreads beyond Assam across Indian landscape.

INDIANIZATION OF CAMELLIA CHINOIS In spite of the incredible agronomical and commercial success of Assam tea, there remained a large section in East India Company unconvinced about its worth in comparison to the Chinese camellia. They were more eager to avail the Chinese saplings for domestication because of their qualitative supremacy over the wild Assam. To report on the earlier amateurish findings, a scientific delegation, headed by Wallich, the cele¬brated Danish-born botanist geologist, including the surgeon-naturalist John McClelland, and another cele¬brated botanist William Griffith, was sent to Assam in July 1835. Dr. Wallich maintained that since the native plants were actually tea, there was no need to import seeds from China. The ‘young Turk’ Griffith, however, had completely a different view and pronounced emphatically that only by importing ‘Chinese seeds of unexceptionable quality’ could the ‘savage’ Assam plant be reclaimed as fine tea. As this wisdom was unquestioningly accepted, a young botanist, Robert Fortune working in the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. Alongside, G. J. Gordon was instructed by the Calcutta Botanic Gardens to “smug¬gle tea seeds out of China.” [Ukers] A deputation, consisting of Messrs. Gordon and Karl Friedrich Gutzlaff, was then sent to the coasts of China to obtain tea seeds. They succeeded in obtaining seeds from southern China that arrived in Calcutta in January 1835, and being sown, vegetated and produced numerous plants. In the beginning of 1836 about 1326 saplings sent to North-East. The tea nurseries were formed at Kumaon and Gurhwal in the Himalayas, and immediately began to grow with all that vigor aided by a small band of Chinese tea-makers whom Dr. Wallich recruited for them in April 1842. In January 1843, the first sample of Himalayan tea was received at the tea table of the British Chamber of Commerce and reportedly pronounced by the members that the fine kind of tea – Oolong Souchong, “flavored and strong, equal to the superior black tea generally sent as presents, and better for the most part than the China tea imported for mercantile purposes.” [Carey]

Robert Fortune, (1813 -1880) was commissioned to undertake a three year plant collection expedition to southern China in 1842, and in 1848. Finally, it was on behalf of the East India Company, he went to remote Wuyi Mountains in Fujian Province and in mid-February 1851 Fortune brought tea-filled cases consisting of no fewer than 12,838 plants, 8 illegally immigrated Chinese tea-workers and tools of trade to Calcutta port via Hong Kong. Dr. Hugh Falconer, who had recently taken over from Wallich as superintendent of the Botanic Garden, received Fortune at Shibpore ferry ghat to take the sprouting tea-plants smuggled from China under his care. The tea plants then dispatched to Saharanpur, formerly a Mughal garden, at the lower foothill, and from there distributed to various Himalayan plantations. Some of that exceptional stock nurtured in Kumaon plantation made its way to Darjeeling, where it would eventually produce the world’s finest and most expensive teas. [Ukers]

DARJEELING TEA Coming of tea to Darjeeling was something almost accidental. It was never considered as a place good for planting tea. Even Sir Joseph Hooker (1817-1911),

founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin’s closest friend, thought of Darjeeling as a place too high with too little sun and too much moisture to grow tea. Dr. Archibald Campbell proved it all wrong within two years of his arrival at Darjeeling as the newly appointed Superintendent in 1839. Previously, when he was in Kathmandu working under renowned ethnologist and naturalist Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894), Campbell was inspired by him to care the native flora and fauna with love. Among other plants in his home garden at the height of 7,000 feet, Campbell in 1841 sowed tea with stock that came from the nurseries in the western Himalayan foothills. The trees came to bear in the second half of that decade, and the Company inspector reported in 1853 that both Chinese and Assam varieties were doing well in Campbell’s garden. Campbell established government sponsored tea nurseries in Darjeeling and Kurseong. While both types of leaf varieties were planted, Chinese ones were unexpectedly, successful. Plants from stock Fortune had smuggled out of China thrived in Darjeeling’s misty, high-elevation climate. The Company opening up land and clearing plots for tea gardens began to circulate plants for individuals and small companies. [Bengal District Gazetteers] The commercial cultivation of tea was started in 1852-53 in Darjeeling with the Chinese variety of tea bushes. Today tea is grown in forty-five countries around the world, summer-flush Darjeeling has always been the best choice of the global connoisseurs, and the most expensive as well. [Koehler]

About 10 million kilograms of Darjeeling tea are grown every year spread over 17,500 hectares of land. [Marketing Analysts] India on an average produced 1233.14 million kilograms of tea between 2011 and 2016. North India produces nearly 5 times more than South; and West Bengal produces 329.60 million kg, which is little more than half of Assam. Darjeeling tea seems quantitatively too insignificant but qualitatively the highest among the best teas of the world. [IBEF]

TEA AND ITS SOCIAL DIMENSIONS In a nutshell this is the story of Indian Tea, which the Britishers discovered, harvested, industrialized and monetized to secure their sovereignty, and left the tea legacy to India when they lost it. This over two hundred year long story tells us how the India’s own wild tea forests turned into tea gardens, and how the smuggled China tea was Indianize imbibing the essence of the mystic Himalayan, Western Ghats, Kanan Devan’s biodiversity.

Tea history, you might have already sensed, is highly illustrative for appreciating the process of cultural shifts leading to acculturation that took place in colonial India, Bengal Presidency in particular, the playground of both the Assam and the Darjeeling teas. Allow me to elaborate in my next post a few elements of the tea history for you to connect the ideas of acculturation I discussed earlier. Happy New Year

REFERENCE 1. Achaya, K. T. (1997). Indian Food: A Historical Companion. Oxford: UP. https://books.google.co.in/books/about/Indian_Food.html?id=CKIJAAAACAA 2. Bengal District Gazetteers: Darjeeling ; Ed.by Arthur Jules Dash. (1947). Calcutta: G.P.Press. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.150149 3. Bruce, Charles. (1840) The First story is an 1838 Account of the Manufacture of Black Tea as practiced at Suddeya in Upper Assam. In: Koi-Hai. December 6, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20061220204732/http://livn-an.com/tearoom/bruce/ 4. Carey, William H. (1964 ). The good old days of Honorable John Company; being curious reminiscences during the rule of the East India Company from 1600-1858, complied from newspapers and other publications. Calcutta: Quins. https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-d&q=Good+Old+Days+Of+Honorable+John+Company+From+1800+To+1858%3B+W.+Carey 5. Charaka Samhita; Edited by Gabriel van Loon. (2003). Handbook on Ayurveda; Volume I. Durham: Center for Ayurveda. https://archive.org/details/GabrielVanLoonCharakaSamhitaVol1Eng/page/n1 6. Driem, George L. van . (2019).The Tale of Tea: A Comprehensive History of Tea from Prehistoric Times to the present time. Leiden: BRILL. https://books.google.co.in/books?id=Z6WODwAAQBAJ&pg=PA625&lpg=PA625&dq=Lieutenant+andrew+charlton+tea+Assam&source=bl&ots=baf_hPx8hM&sig=ACfU3U0t3UX- zqmLIVkXUuoXF3VXwdFEvQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjfpf2KuLTlAhXQbn0KHa9mAHwQ6AEwBHoECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=Lieutenant%20andrew%20charlton%20tea%20Assam&f=false 7. Gazetteer for Scottland. (2017). Robert Bruce (1789–1824). In: Gazetteer for Scottland. Edinburgh: University. https://www.scottish-places.info/people/famousfirst3224.html 8. Ghosal, Ranjan Kumar (2019), Indian history buff. Quora July1, 2019. https://www.quora.com/What-was-the-role-of-Maniram-Dewan-in-the-Revolt-of-1857 9. Griffith, William. (1847). Journals of travels in Assam, Burma, Bootan, Afghanistan and the neighbouring countries. Calcutta: Bishop’s College. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/15171/15171-h/15171-h.htm 10. IBEF. (2018). Tea Industry and Exports in India. In: India Brnad Equity Foundation – Portal. Last Updated: December, 2018. https://www.ibef.org/ 11. Johnson, George W. (1843). Stranger in India; or, Three years in Calcutta; v.1. London: Golburn. https://ia902702.us.archive.org/22/items/strangerinindia00johngoog/strangerinindia00johngoog.pdf 12. JSTOR. Global Plant Resource. [Search Engine] https://plants.jstor.org/login?redirectUri=%2Fstable%2F10.5555%2Fal.ap.person.bm000329174%3fsaveItem=true%5D 13. Kochhar, Rajesh. (2013). Natural history in India during the 18th and 19th centuries. in Journal of Biosciences 38(2) June 2013. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236674827_Natural_history_in_India_during_the_18th_and_19th_centuries 14. Koehler, Jeff. (2015). Darjeeling: a history of the world’s greatest tea. London: Bloomsbury. https://www.goodreads.com/user/new?remember=true 15. Negi, Vineeta, and ors. (2018). Tea Kinnauri, Thang & Namkeen chai: an Ayurvedic perspective. In: World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. Volume 7, Issue 18, 638-649. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328802003_Tea_Kinnauri_Thang_and_Namkeen_Chai_an_Ayurvedic_Perspective_A_review 16. Santoshini, Sarita. (2016). Singpho Tea Party. In: Traveller India, Natgeo, february 22, 2016 http://www.natgeotraveller.in/singpho-tea-party-the-story-behind-the-brew/ 17. Sharma, Jayeeta (2011). Empire’s Garden: Assam and the Making of India. London: Duke University. https://books.google.com/books?id=W2dtxgZba6MC&pg=PA40&lpg=PA40&dq=a+significant+linguistic+shift,+from+%E2%80%9Ctea+forests%E2%80%9D+to+%E2%80%9Ctea+gardens&source=bl&ots=3_FfCbYj0-&sig=ACfU3U03VGNWmyb4pgp4UskXlr7w-ZBkZQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiI5a62mKvlAhXyxlkKHV9wA3oQ6AEwAHoECAcQAQ#v=onepage&q=a%20significant%20linguistic%20shift%2C%20from%20%E2%80%9Ctea%20forests%E2%80%9D%20to%20%E2%80%9Ctea%20gardens&f=false%5D 18. Wheeler, J Talboys (1878). Early Recods of British India: A history of the English settlements in India. Calcutta: Newman. https://ia800208.us.archive.org/17/items/earlyrecordsofbr00wheeuoft/earlyrecordsofbr00wheeuoft.pdf 19. William Ukers. (1935). All about tea; v.1. New York: Tea & Coffee Association Trade Journal Company. https://archive.org/details/AllAboutTeaV1/page/n9

TEA: A BRITISH GIFT TO INDIA

BACKDROP Tea might have been tasted by an Indian in around 1040 AD while the British did it before 1662 AD, and in no time the British Tea Culture came about some three centuries ahead of India’s courtship with tea.