#balkan core

Text

When you wanted cottagecore 🌷🌻🍎🍄

But you're in the Balkans so you get cottagecore ⛰🚜🚬🪓

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

picked mum up from airport ofher day and ahe brought back sooo much bosnian candy im so happyyyyy :3 TOFITA🔛🔝

#bosnia#bosnie herzégovine#balkan#east europe#slavic#balkan core#i love tofita#omg#bosnia core#heheeee

1 note

·

View note

Text

lolz >_<

#adidas#aesthetic#emo#grunge#mutuals#black kray#yung bruh#yung lean#eastern europe#balkan#core#eastern europe aesthetic#pinterest#pinterest girl#tumblr girls#sanrio#hello kitty#hello kitty girl#:3#💋#opium label#destroy lonely#moots#SoundCloud

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eastern Europe core is not depressive it's lively you guys just don't get it.

#dirty kitchens and soviet buildings i love you#put also some cats#and street lights#sometimes meaning of life means this#eastern Europe core????? i couldn't find a name Balkan core???? balkan soul 💪#i like that type of pictures it feels lively for me so real

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

ive started a shitstorm here and im still getting ppl in my inbox and notes absolutely missing the entire point of WHY knowing basic geography is important.

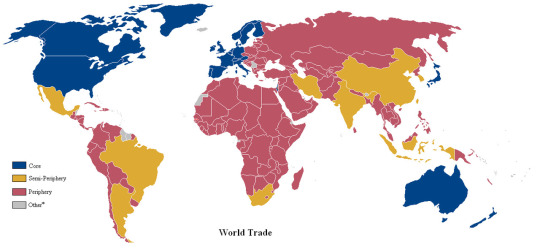

people calling me out for european imperialism are proving it by not even understanding the differences between western and eastern europe and the economic differences and exploitation or understanding what the fuck imperialism itself is and what constitutes it. yall keep arguing with a person from balkans about eurocentrism and this is why you should know where balkans are. i dont care about you knowing that zagreb is the croatian capital, its rly not important, the purpose of this entire discussion is understanding economic contexts of different countries

the actual purpose of this converstation is learning what imperial core is and how usamericans not trying to learn abt the countries theyre exploiting is harmful.

blue countries constitute the imperial core and hold monopoly over market, trade, education, military powers, etc. if you live in them you have some responsibilities. you affect the periphery and semi-periphery countries. your votes, your president, etc, affect them. you have a duty to know about the countries that your country opresses.

i also hope people read at least the wikipedia page on globalism if they wont read marx. and you can actually learn what the fuck global south is too

here's more information on imperial core countries and how that affects the rest. its a newer article, as opposed to the maps from 2000 and 2005.

im srsly done w this whole discussion and unless you want to discuss actual issues about exploitation and neocolonialism instead of asking me to name 50 usa states dont botheeeer im done

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Before Israel’s war in Gaza, Palestinian programmer Doaa Ghandour was working on Palestine Skating Game’s grind rails. Any skater — be that skateboarding or roller skating — knows rails are essential to street-style skating. In Palestine Skating Game, these grind rails weave through the West Bank, Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater-style, for use as you spray graffiti on the Israeli-built separation wall.

It’s easy to see the appeal of Palestine Skating Game in its early prototype on Itch.io: The futuristic Bethlehem is made all the more colorful with paint splatters and graffiti, set to what the team describes as “Arabic electronic music.” And it’s designed to be enticing: “The idea is that if you immerse Westerners in that kind of art and music from the region, you’ll start to actually see people from the region as human beings,” Palestine Skating Game’s current project lead told Aftermath in November.

Palestine Skating Game has been in development for roughly two and a half years. The inspiration initially hit after the project lead, who was granted anonymity by Polygon, saw We Are Lady Parts, a TV show about an all-women Muslim punk band. Development has changed since then — it had to. “We have to acknowledge the existence of a lot more suffering,” the project lead told Polygon. “We are having to do the thing where we had one creative vision for the project, and now we have to figure out how that changes with respect to the events unfolding.”

Israel’s war in Gaza is entering its fourth month. Nearly 28,000 people have been killed in Gaza, 388 in the occupied West Bank, and 1,139 in Israel, according to Al Jazeera. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) is currently hearing a genocide case against Israel, wherein it argues that “the acts and omissions by Israel complained of by South Africa are genocidal in character because they are intended to bring about the destruction of a substantial part of the Palestinian national, racial and ethnical group,” as reported by Vox. Israel denies the accusation, saying its attacks are justified as a response to Hamas’ terrorist attack in Israel on Oct. 7, where roughly 1,200 people were killed.

“Israeli Occupation Forces have cut off all medical supplies, as well as water and food, from Palestinians in Gaza, amidst the continued carpet bombing and genocide. It has left our friends to navigate the most severe humanitarian crisis of our time,” the fundraiser reads.

Palestine Skating Game has been in development for roughly two and a half years. The inspiration initially hit after the project lead, who was granted anonymity by Polygon, saw We Are Lady Parts, a TV show about an all-women Muslim punk band. Development has changed since then — it had to. “We have to acknowledge the existence of a lot more suffering,” the project lead told Polygon. “We are having to do the thing where we had one creative vision for the project, and now we have to figure out how that changes with respect to the events unfolding.”

The project lead said the team, which is Ghandour, writer Hadeel, and himself with four other developers and volunteers, want to make it easy for people — even those unfamiliar with the conflict — to see what’s happening in Gaza. “We want to make it easier for people to see, Oh, here’s how the West Bank has been slowly eaten up and balkanized,” he said. “We also just want it to be something that people want to share with their friends. There should be so many fucking cool things in this game that people will immediately want to say, ‘Hey, you’ve got to see this.’”

The Palestine Skating Game team — the core group, four paid developers, and roughly 15 volunteer developers — is working on a full vertical slice, or a polished, short demo, of the game. They’re also hoping to run a Kickstarter, GoFundMe campaign, or other investment to fund more development.

#palestine#palestine skating game#gaza#free palestine#free gaza#doaa ghandour#video game industry#gaming industry

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Religious fundamentalism: The process of isolating out a religion’s core doctrine and investing it with ultimate authority while rejecting all later developments as superfluous or heretical; e.g. Salafi Islam, Karaite Judaism, fundamentalist Christianity.

Religious conservatism: The preservation of a religion and its customs as they have been passed down over the centuries by the clergy and wider society; e.g. traditional Catholicism, Orthodox Judaism, Hindu traditionalism.

Religious modernism: Altering a religious tradition to adapt it to new social, political, cultural, and scientific developments; e.g. modernist Christianity, Reform Judaism, ‘neo-Hinduism’, Islamic modernism.

Fundamentalism and conservatism do not have anything inherently to do with religious politics and likewise modernism does not necessarily mean the removal of religion from public life. I will get to politics soon.

A better way to visualize these than discrete categories might be something like this, sorry for the image quality:

They are processes and tendencies, things you do to your religion, which can absolutely bleed together and coexist.

Today the official position of many religious institutions (e.g. the mainstream Catholic Church or LDS Church) falls somewhere between conservatism and modernism. Conservative and Modern Orthodox Judaism are also good examples – of being willing to bend significantly in some areas while upholding tradition in others.

The Islam of Muammar Gaddafi, the Hinduism of Dayanand Saraswati, and arguably the State Shintō of the Meiji Restoration (though Shintō isn’t scriptural) exemplify a different trend: that sometimes the most effective way to modernize is to fundamentalize. If your goal is to radically reshape the tradition, then stripping it down to the fundamentals can give you more latitude to innovate, and delegitimizes the conservative clergy who have a stake in keeping the tradition the way it is, all while framing your project as in fact the most orthodox.

More commonly though, fundamentalists will make common cause with conservatives. Christian fundamentalists in the U.S., with a few radical exceptions like Reconstructionism, have more or less always considered themselves a type of conservative, and there is a strong resonance between fundamentalists and conservatives in Islam – Saudi Wahhabism takes a fundamentalizing approach in law and culture while upholding ecclesiastical and monarchical power, and was instrumental in the rise of more categorical fundamentalisms like al-Qaeda (though even bin Laden cited medieval scholarship when it suited him). In a similar sense some on the Jewish Orthodox right, especially Kahanists, have a fundamentalizing emphasis on returning to the Torah given at Sinai but remain bound to the later rabbinic tradition – “aspiring fundamentalists within a framework that poses challenges to achieving such a thing” in @boffin-in-training’s words.

I would also mention the tendency for an old fundamentalism to calcify into a new conservatism, almost cyclically. The Protestant Reformation was in many ways a radical fundamentalization of Christianity, but today Protestantism is its own religious tradition with its own conservatives. Again, see Saudi Wahhabi Islam for what Michael Cook calls an “eighteenth-century fundamentalism” that evolved into a “puritanical conservatism”.

Religious politics: Any use of religion for the purposes of modern politics, e.g. political Catholicism, Islamism, Hindu nationalism.

Religious nationalism or ‘religio-nationalism’: Religious politics with primarily nationalist, ethno-territorial concerns linking religious identity with national identity; e.g. most Balkan nationalisms, Hindu nationalism, Buddhist nationalism, the Muslim League, Zionism. There’s a subtle difference between religious identity as national identity, such as in the examples above, versus a national church playing a strong role in cementing an existing secular nationality, e.g. Anglicanism in England or Catholicism in Spain and Poland.

Fascisms which define the ingroup religiously belong here. They are still technically secular and prioritize national and cultural identity above all: the Sangh Parivar has a Muslim wing and the Ustaše even tried to set up their own Orthodox Church.

Religious dominionism or clericalism: Religious politics trying to expand religious control over the government to impose certain values on society, whether in a fundamentalist or conservative (or even modernist) spirit; e.g. Islamism, the Christian right, integral Catholicism, Israel’s Orthodox right. These could be divided, on the model of Salafism, into ‘activist’ or ‘political’ movements which try to win elections within the existing system, and ‘insurgents’ who want to overthrow godless governments and install ones of their own.

Both names have drawbacks: dominionism suggests fully-fledged theocratic rule whereas I mean it much more broadly, while clericalism implies the role of a clergy even though many fundamentalists and modernists are explicitly anti-clerical. Certainly it would seem odd to describe Hassan al-Turabi or Muammar Gaddafi as ‘clericalists’.

Clerical fascism: Given what I just said it might be most accurate to use ‘clerical fascism’ as Roger Griffin does, to refer specifically to the collaboration of clergy with fascist movements (e.g. the stance of the Catholic Church in Italy, Croatia, Brazil, etc), especially through genuine ideological fusion like in the work of Emanuel Hirsch. Theoretically this is distinct from (quasi)fascist movements which incorporate dominionism on their own, like the Kahanist ‘halachic state’ or the League of the South’s intention to run independent Dixie on Biblical law. None of the original clericofascisti or Deutsche Christen had such extreme goals.

This post brought to you by:

Ancient Religions, Modern Politics: The Islamic Case in Comparative Perspective, Michael Cook

“The appeal of Islamic fundamentalism,” Michael Cook

“The New Religious Politics and Women Worldwide: A Comparative Study,” Nikki Keddie

Salafi movement – Wikipedia

“The ‘Holy Storm’: ‘Clerical Fascism’ Through the Lens of Modernism,” Roger Griffin

My attempt at a typology of fascist religious discourse with @anarchotolkienist’s helpful addition, and a later one which sort of anticipated this post although with some different terminology.

And a very interesting conversation about Cook’s work with @ boffin-in-training in the fash study Discord.

#reading#christian identity politics#armp#cannot emphasize enough that i have no professional authority in history or political science i'm just autistic

351 notes

·

View notes

Text

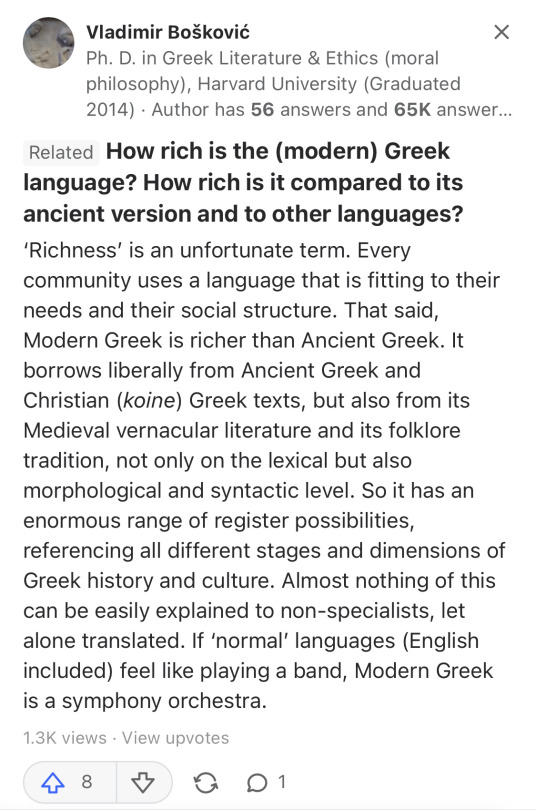

This is something brilliant I found on quora. Aside from the band-orchestra comparison that I have no opinion on as I should know many, many languages to dare tackle that, and which is a parallel that could perhaps only be justified coming from a man passionate enough to get a PhD in Greek literature and ethics, Mr Bošković is actually on point in what he says.

Typical western academia gets wet over Ancient Greek and typically scorns Modern Greek without a proper explanation, to the point of just referring to one form of the language: Greek, and calling it dead. In their minds, there can only be one form of Greek, the ancient one, and it is dead for good. Modern Greek doesn’t belong with their academic and lingual concerns.

But Bošković, who has obviously studied a greater span of the Greek language than the average stuck-up classicist, puts it so well and in such a short and simple text that I could never do it. I always thought Modern Greek is more flexible than Ancient Greek but I couldn’t explain why well. Here it is then: what many don’t realise is that Modern Greek operates in a very liberal fashion. It takes elements from large lingual pools. It has the Ancient Greek pool all to itself, to take elements at will. It can choose between very archaic, Koine / biblical / medieval or folk neo-linguistic elements or fuse them all together, technically without restrictions. The historical contact to Latin, Italian, Turkish, Slavic, Arabic and Albanian populations gives it access to the Romantic, Anatolian, oriental and non-Greek Balkan pools. Modern Greek has a very good ability to bend foreign elements enough to make them adjust to the Greek core of the language, instead of adjusting to them (ie all foreign loanwords are bent to follow Greek grammatic rules of inflection and their vocalisations usually change enough so that they are entered smoothly in the language). The local idiomatic element is also significant in every region and is particularly alluring in prose and verse (hence my recent comment that I prefer modern - but NOT contemporary - Greek prose).

That doesn’t mean that I don’t love Ancient Greek prose and verse. But here is the crucial nuance: the ancients and medieval people did their best to write in the highest form of the language they could master. When we read an ancient text, we witness the earnest efforts of the ancient poets and writers to be glorified through their writing.

Modern speech is unfortunately deteriorating* and we can’t compare the potential of the two ages of the language. Contemporary writers aren’t putting an effort to write in the highest lingual form they can master. On the contrary, they strive to be relevant and, in fact, as non-challenging as possible, so that they will cater to a wide, mainstream audience. And because everyone can write nowadays - it is not an activity saved for the wisest or most educated - there is a load of mediocre lingual usage inside which a specimen of high lingual form can be viewed as eccentric, pretentious and eventually undesirable.

Because of this, Modern Greek cannot utilise all its tools anymore (as well as many other languages to their own degree, of course). Reading the Iliad in its original has been fantastic so far and I was wondering why we can’t write like this anymore but now I am realising that there is nothing to prevent us from doing it from a technical aspect. There are no dead words in Greek. There are words which have become rarely used enough that some people would consider you a weirdo for using them and others would themselves refuse to learn, convinced there is no use in taking an extra step. Words that are recorded in texts, words whose meaning we know, can’t be dead, even if they are rarely used. It’s the obsession of the average person to follow the mainstream trend that threatens a word more than anything else. Another fact is that Greeks of different ages fluctuate between different forms of grammar, unsure whether a more archaic or more modern inflection is appropriate. The truth is that there is no wrong way, however Greek linguists lately try to wipe out older, more archaic forms in exchange for newer, simpler ones. The intent is always to become as approachable, as unchallenging as possible. There is no de facto death of older types of usage as long as they are recorded and we know how they work and some of us use them still - it’s literally a few linguists trying to give Modern Greek a distinct, simpler identity by ignoring the language’s most crucial characteristic: its flexibility.

Νεφεληγερέτης Ζεύς is a common characterisation of Zeus in the Iliad (Nepheliyerétis Zeús - Zeus the Cloud-gatherer) . There is no real reason to prevent someone from using this phrase intact nowadays, as both roots of the first word do exist in modern Greek. And even if someone was too self-conscious about writing so ambitiously, they could do with a more modern or folkish version like νεφελοστοιβάχτης or συννεφοστοιβάχτης or νεφομαζωχτής or νεφελαθροιστής (ie nephelostiváchtis, sinephostiváchtis, nephomazochtís, nephelathristís). Would they though? No, they wouldn’t. Why take the extra step?

My point is, Modern Greek is an overlooked, extremely potent language and we do exactly nothing with or about it.

*Whoever is quick to argue that a language never deteriorates because it always morphs into a reflection of its respective nation / society and its needs should either stop fooling themselves or immediately get alarmed by the current state of the respective society at question.

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shorts, socks and slippers (Balkan dad core)

Screenshot from their discord videos

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

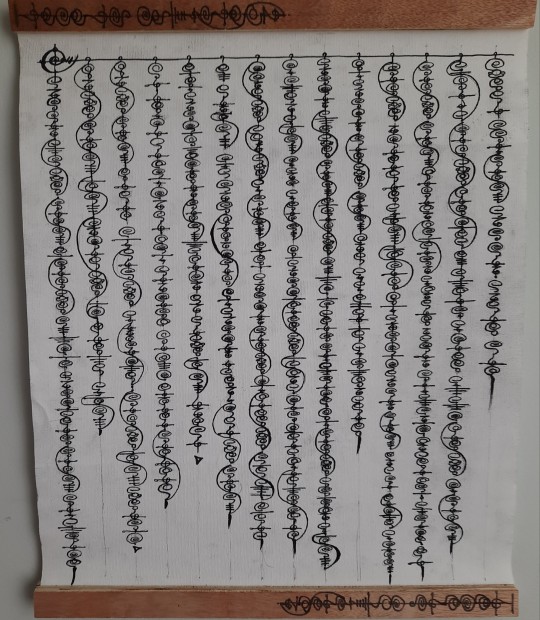

I have made another piece of Vulcan calligraphy. This time, it is a translation of 'Conscientious objector' by Edna St.Vincent Millay.

Vulcan text

[Literal translation]

Frame: Ahkhan klee'fah-su

[Warfare refuser]

1) Dungau tev-tor nash-veh, hi nam-tor veh ek if dungi-than nash-veh na'Tevakh.

[I shall die, but that is all, which I will do for death.

2) Zhu-tor nash-veh ish-veh fugal-tor-ik jarel t'ish-veh.

[I hear them leading their jarel. (horselike animal)]

3) Zhu-tor nash-veh ralash fi'lan-tol t'aushfa-kel. Nam-tor ish-veh toranik.

[I hear the noise of the hoofs on the floor. They are busy.]

4) Ma ar'kada svi'Cuba, svi'Balkans, ma wehk haishaya nash-asal.

[(they) Have tasks in Cuba, in Balkans, many demands this morning.]

5) Hi ri'dungi-meskarau nash-veh elsaku, lu dator ish-veh aushfa.

[But I will not hold (their) tether {there is no Vulcan word meaning specifically a bridle, so I thought 'tether' an appropriate word}, when (they) prepare the animal. ]

6) Heh lau ish-veh fi'dvun mamuk-fam, ri'dungau abru'gla-tor nash-veh.

[And they may move on {not as a phrasal verb, but rather meaning 'mount'} by themselves, I shall not help them up.]

7) Kwul-tor pla-dor t'nash-veh, hi ri'dungau var-tor ki'sahr-tor vil-tei wilat.

[(they) Strike my shoulders, but I shall not tell where the vil'tei has run to.]

8) K'felu t'ish-veh f'tuf t'nash-veh, ri'dungi sahr-tor ip-sut kan wilat s'alem-flash.

[With their hoof on my chest, I will not (tell) where in the mangrove forest the hiding child ran.]

9) Dungau tev-tor nash-veh, hi nam-tor veh ek if than na'Tevakh. Ri'nam-tor dvinsu t'ish-veh.

[I shall die, but that is all, which au will do for death. I am not their servant.]

10) Ri'dungau var-tor nash-veh shul t't'hyle il t'nemutlar.

[I shall not tell the location of my friends nor my enemies.]

11) Nam-tor ugayalar t'ish-veh is-fam, ri'dungi-gluvau nash-veh yut na'ha-kel t'fan-veh.

[Their promises are useless, I will not show them the way to anyone’s home.]

12) Nam-tor nash-veh zamasu svi'panu t'sular - utvau na'tefuik sutra svi'Tevakh ha?

[Am I a spy in the world of people - reason for leading people to death? {Questions are asked differently in Vulcan. Essentially, in case of yes/no question, it is a statement followed by 'ha?'. So something along the lines of 'I am a spy in the land of living, and this is a reason for leading people to death, yes?}]

13) Pi-maat, nam-tor shar-kiht heh besan t'Kahr t'etek shar'tor k'nash-veh.

[Relative (Clan mate?), the safety codes and the plans of our city are safe with me.]

14) Worla fna'nash-veh dungau dular vash.

[Never through me shall you be destroyed. {I struggled with the adjective here, since I couldn’t find a word for 'damaged' or 'destroyed' and didn't want to substitute it with 'unmade'. I settled on using the core of the word destroy, but I'm not certain whether it was the best decision.}]

Original text:

I shall die, but

that is all that I shall do for Death.

I hear him leading his horse out of the stall;

I hear the clatter on the barn-floor.

He is in haste; he has business in Cuba,

business in the Balkans, many calls to make this morning.

But I will not hold the bridle

while he clinches the girth.

And he may mount by himself:

I will not give him a leg up.

Though he flick my shoulders with his whip,

I will not tell him which way the fox ran.

With his hoof on my breast, I will not tell him where

the black boy hides in the swamp.

I shall die, but that is all that I shall do for Death;

I am not on his pay-roll.

I will not tell him the whereabout of my friends

nor of my enemies either.

Though he promise me much,

I will not map him the route to any man's door.

Am I a spy in the land of the living,

that I should deliver men to Death?

Brother, the password and the plans of our city

are safe with me; never through me Shall you be overcome.

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

More questions! Would you consider having cross splat play for a group with v5, ww5, and h5? Have the mechanics been simplified/streamlined enough for that to be possible without being a huge headache?

Also, unrelated: I think in today's ttrpg terms WoD5 wants to be a "fiction first" type of game. It definitely has introduced some features that add support in that way, such as the relationship maps, considering Coterie type, and the touchstones. But I think some of its mechanics still cleave to that "simulationist" mindset of the 90s and aughts, and get in the way of what the narrative does well 😅

This is a bit meandering, but I hope you gain something from it anyway.

So for my money, the big issues with cross splat play are thematic. Vampire and Werewolf are asking different questions of their players, and pursuing different kinds of horror. For all that they're nominally set in the same world, they don't fit right when they're shoved in next to each other. It's like how comics crossovers reduce the cosmic splendour of interplanar warfare between godlike entities and the workaday world of a nerdy student/photographer to a sort of spectacular slurry when they're put together - it can be fun, but it feels like less than the sum of its parts because none of them are getting to do what they were designed for.

Hunter is the exception. I think Hunter can dovetail with another splat reasonably well, because the Hunters are real people in over their heads and confronting a supernatural horror; a premise that can adapt to whatever kind of horror the other splat is presenting. Hunter also has tidier mechanics, which brings me to the "why I, specifically, wouldn't include Werewolf in a crossover" part.

When I've checked out Apocalypse in the past, I've found it aggressively America-centric (why do werewolves in the Celtic nations or the Balkans use terms from the First Nations?), not quite selling the "melting pot" pack (maybe this is me, but I feel like a werewolf pack should all be from the same tribe and differentiated by something else, like auspice), and worst of all - dull. Between Tribes and Gifts and Auspices and Spirits and five different statblocks it's managed to make pretending you're a werewolf fussy and pedantic.

I like trad games. I came up with Call of Cthulhu and WFRP. Pass me the percentile dice, we're going in! But the strength of V5, specifically, is that it's modular. From "only players roll" to "only simple conflicts" to "right, look in the back of the book for a combat move", V5 scales to an extent where it can be mechanically present, imposing the bare minimum of Hunger and Predator Type, in even a fairly lightweight chronicle - or it can go full tradgame, if you want it to!

The trouble with the wider WOD, in my opinion, has been the development outwards from Vampire. Most of the splats have started with Vampire's mechanics (an equivalent to blood points, humanity, disciplines, clans and so on) and adapted them and developed on top of them, which means they end up overburdened because they weren't working out from a neutral core. (CofD sidestepped this by starting with the human-focused core game and building very similar sets of numbers into the different splats, one direction at a time.) Combine that with the ever more convoluted world-building of the One World of Darkness conceit - you and I know that no amount of "the Lupines from Vampire aren't the Garou from Werewolf" holds up to the way the Revised books were written - and by the time you get to Wraith, both the system and the setting are overdeveloped and creaking at the seams.

I bring up Wraith because I really, really want Wr5 (technically it'd be the fourth edition, but whatever). I want a Storytelling Game of Psychological and Survival Horror, something that interrogates why the dead haunt the living and poses that as its central question. You can keep your Kingdoms and your Legions, but they're the threats that drive the playable ghosts into the periphery - they've made unacceptable compromises to survive deeper into the Shadowlands, closer to Oblivion. The Guilds offer another way - true death staved off by staying close to the truly alive. Maybe that's been the premise of Wraith all along, but I got the impression the game as published was more interested in building Stygia as a dark fantasy adventure than in ghost stories.

You're not wrong though: the WOD games have always existed in the space between blow-by-blow gun-catalogue tradgame and experimental, experiential storygame. When they're good, they turn that space into a sliding scale. When they're bad... well, when they're bad they're the detailed rules for kung fu in Requiem. The whole thing runs better when you're fiction first, but retain just enough risk/resource management that the mechanics get to intrude and remind you that you're not playing heroes. You are the monster. The more action you take, the more those trackers move. The Hunger is rising. When will you Rage?

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

I can't help but notice that all of the people in your anti-colonialism by "marginalized people" book rec list are people who were born and grew up in either the US or, in one or two cases, another white Anglophone country. I.e. the imperial core.

As a non-American I wonder whether, due to the cultural hegemony of the US and other Anglophone countries, the perspectives of people who have spent their whole lives in the Imperial core (even if marginalized in other ways due to their race or some other attribute) can be considered "authentic" depictions of the effects of colonialism in the way that you are presenting them. I find that people from the US, even POC people from the US, are often pretty incapable of understanding non-US perspectives on social justice issues because they're rarely exposed to them and because they grew up brainwashed with media that treats the US as the center of the world, so they overlay the US framework over everything.

I would perhaps have liked to see more recs for authors writing about colonialism who actually grew up in countries that have been affected by colonialism, or at least in countries that aren't as rich and powerful as the US and are therefore heavily dependent on the political whims of powerful Western ones. I'm sure there's a bunch of people in South America writing SF/F, for example, considering their long tradition of awesome magical realism. Or South Africa. Or India (I note that Salman Rushdie is not on your list, for example). I'm not writing this to be pettish, because I don't know enough about it either and would actually like to know, I just feel like perhaps we should all be a bit humbler when talking about this since a strictly US-centric perspective is still a VERY limited one when talking about colonialism (by definition an international, intercultural phenomenon), even when written by POC.

I also wonder about your definition of "marginalized" and if it doesn't fall into the same US-centrism that I talked about in my previous paragraph (even if we assume that "marginalized" means "marginalized as it relates to colonialism" and ignore other forms of marginalization). Is a person from, say, the Balkans, marginalized enough to write about anti-colonialism, or are they exactly the same as a white American in your perspective? Does it matter where from the Balkans? Does it matter if they're Muslim or Christian? How about a Ukrainian person? How about a Ukrainian Jew? Is a person from Bosnia or Ukraine, who went through a war in their lifetime, less qualified to write about war than Kuang, who grew up middle class and went to an Ivy League school (and honestly did a really shitty job of portraying a war in The Poppy Wars), just because they're "Caucasian"?

Also, people are allowed to acknowledge flaws of books written by POC without being automatically labeled as racist, you know. Finding Babel too heavy-handed or on the nose has nothing to do with finding POC characters annoying or unrelatable and sorry but, yeah, IMHO it's really on the nose and annoying about it. It's the writing style that's the problem, not the themes. Also the central metaphor, IMHO, makes it completely useless as a colonialism allegory because if you can destroy colonialism by destroying one magical uberpowerful whatsit, your book is kinda not serious enough about nuanced representation of sociological and political forces to be considered impactful anti-colonialist literature. Saying that as someone who loves Butler and Jemisin. Thea Guanzhon, for example, is a Filipina born and raised in the Philippines and still lives there, which makes her book way more of an "own voices" account of colonialism than Kuang's could ever be in my accounting, but that doesn't mean that her account of colonialism has any particular nuance to it (so far it's just the backdrop for the enemies to lovers romance). So even assuming that Kuang's account is resonant enough with enough people (which I know it is because her book is super popular), who is more deserving of being on your "own voices" list, Kuang or Guanzhon?

I also wonder why white women in particular?

The simple response to all of this is that the post you're referring to broke containment.

I debated replying, because I can't help but feel your message was written in bad faith. But I'm going to try to give you the benefit of the doubt.

You are absolutely right about the limitations of the original list. I truly didn't expect it to reach so many people, and I am not nearly as well-read as I'd like to be when it comes to literature written outside of the West. Please take a look at the reblogs, where a bunch of awesome people have done incredible work filling the gaps I left.

I struggle with the rest of your message. I explicitly stated that I do not expect people to enjoy specific books written by BIPOC authors, simply that I've noticed a very frustrating pattern. And yet you suggest I'm saying that if someone doesn't like Babel or The Hurricane Wars, I'm saying they're racist. Be serious.

Even as a child of multigenerational immigrants, I'll freely admit that I personally have a very US-centric perspective on social issues that I need to work on, but it's wild of you to say that all POC people born in the US are "pretty incapable of understanding" global issues.

When I wrote "marginalized" in the original post, what I really meant was "BIPOC and BIPOC queer people.” I should’ve been more careful about the wording.

Why white women in particular? When it comes to anti-colonial and anti-imperialist fiction (written by Anglophones) the authors that I see most highly and frequently praised are white women. I'd list the specific ones I'm talking about here, but 1. I don't want to be hunted for sport by their fans, 2. I've actually enjoyed some of their work, and 3. they're only a small part of the problem and I think people should be allowed to write whatever they want as long as they can handle the criticism. But I'm sorry, white women. I'll do better next time. I also want to use this moment to apologize to all the dumbasses complaining about my tone/me being "shouty." Reverse racism is real, and we must all stand vigilant hahaha miss me

You telling me to be humble feels a tad hypocritical, but sure, I'll take that under advisement.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Judeo-Arabic has in common with Arabic – and what it does not

Jews in Arab lands spoke a language much the same as their Arab neighbours, but they were not Arab Jews, argues Philologos in Mosaic. (With thanks: Ilan)

Professor Ella Shohat, pioneer of the label ‘Arab Jew’

Judeo-Arabic” is said to be the language spoken by the large number of Jews who inhabited the Arabic-speaking lands of the Middle East before leaving them after the establishment of Israel. But although the term is widely used, did such a distinct language actually exist? Not according to Ella Shohat, Professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies at New York University, as argued in a recent essay “‘Judeo-Arabic and the Separationist Thesis,” published by her in the newly founded Palestine/Israel Review.

Shohat’s argument is straightforward. While the speech of Jews in Arab lands, she contends, may have had certain peculiarities not shared with Muslim and Christian speakers of Arabic, these were minor features that caused neither Jews nor non-Jews to feel that Jews spoke anything but the ordinary colloquial Arabic of their region; moreover, these features were regional themselves, so that what was true of the speech of a Jew from Baghdad was not necessarily true of the speech of a Jew from Cairo, and the “Judeo-Arabic” of a Moroccan Jew was different from the “Judeo-Arabic” of a Yemenite Jew. The idea, writes Shohat, that there was ever a “Judeo-Arabic” common to all Arabic-speaking Jews and setting them apart from Arabic-speaking non-Jews is a myth propagated, for ideological reasons, by contemporary Jewish linguists.

This myth, Shohat maintains, was associated with Zionism and with Israel’s conflict with the Arab world, which made it seek to “de-Arabize” Arabic-speaking Jews by insisting on “the inherent distinctiveness of the Jewish [form of Arabic] from the Arabic language [spoken by non-Jews] and its assumed connectivity to other Jewish languages in other places.” On the one hand, that is, placing the speech of Jews in Arab lands on a par with truly distinct Jewish languages like Judeo-German (Yiddish) or Judeo-Spanish (Ladino) served to create the false impression that they lived in a state of social separation from their non-Jewish environment, as did Yiddish speakers in Eastern Europe and Ladino speakers in Turkey and the Balkans; on the other hand, it conveyed that they had nothing linguistically in common with their new neighbors in Israel, the Arabic-speaking Palestinians. This “separationist thesis,” as Shohat calls it, was thus intended to drive a wedge, historical and present-day, between Jews and Arabs in the name of Jewish uniqueness.

Needless to say, Shohat, who grew up in Israel, to which her family came from Iraq, and who calls herself an “Arab Jew,” has her own ideological ax to grind—and she grinds it far more tendentiously than did such proponents of “the separationist thesis” attacked by her as the eminent Hebrew University linguists Joshua Blau (1919–2020) and Haim Blanc (1930–1984), both given prominence in her article. Still, one must not be blinded by her anti-Zionism and lack of linguistic training into dismissing her argument out of hand, because it is not entirely baseless.

This is so because, although the question of what distinguishes a language, what a dialect, and what a mere regional or ethnic variety of standard speech is a vexed one that indeed often involves political and ideological issues, the issue of mutual intelligibility is invariably at its core. Where such intelligibility exists to a high degree, separate languages do not—and Shohat is correct in saying that speakers of the ordinary Arabic of the various regions of North Africa and the Middle East, and speakers of these regions’ “Judeo-Arabic” variants, never had any trouble understanding one another.

To this statement, it is true, two caveats need to be added. The first is that, prior to modern times, Arabic-speaking Jews wrote Arabic in Hebrew characters that non-Jews could not read and were unable themselves, for the most part, to read Arabic characters; the written Arabic of each group, therefore, was a closed book to the other. The second caveat is that, though its grammar, syntax, and general vocabulary were no different from those of ordinary Arabic, “Judeo-Arabic,” like Jewish speech nearly everywhere, made extensive use of Hebrew and Hebrew-derived words that non-Jews were unfamiliar with.

Neither of these points, though, carries critical weight. Writing Arabic in the Hebrew alphabet does not mean that its writers were writing a different language any more than Serbian and Croatian are different languages because Serbs write Serbo-Croatian in Cyrillic characters and Croats in Latin ones. And while a Moroccan Jew who said “Simossilinu” (from Hebrew Hashem yatsilenu), “God help us,” to a non-Jew in speaking of some predicament would have met with a blank stare, this is precisely why he would have been unlikely to say it, just as a New York Jew would not generally say to a non-Jewish colleague, “Do I have tsuris!”

Moreover, even when Jewish speakers pronounced Arabic words or used Arabic grammatical forms differently from their neighbors, such pronunciations and usages were rarely uniquely Jewish. If the Jews of Baghdad, for instance, said kultu, “I said,” rather than gelt, as did their Muslim counterparts, this was because kultu was the standard form, still widely used in the Arab world, that they had preserved as one of the city’s oldest communities, whereas non-standard gelt was brought to Baghdad by rural and Bedouin migrants. And conversely, if the Jews of Cairo said leysh, “why,” in place of Cairene ley, this was because many of them could trace their roots to Syria and Lebanon, where leysh was the accepted usage. When Baghdadis heard kultu from Jews, or Cairenes heard leysh, they were not hearing anything felt by them to be foreign to Arabic.

Such examples help demonstrate why Shohat is right. But they also demonstrate why she is wrong, because the very fact that Jews wrote Arabic in Hebrew characters, or clung to usages that were not the rule among the non-Jews in whose midst they lived, indicates that, even if “Judeo-Arabic” was not very different from non-Jewish Arabic, it was the product of a tightly knit and inwardly oriented community that did separate itself from its surroundings. Linguistically speaking, such things could only have happened in an environment in which Jews socialized mostly or entirely with themselves and had relatively little social contact with non-Jews. While Jews and non-Jews in the Arabic-speaking world might have enjoyed good neighborly relations, done business together, and been on superficially friendly terms, clear boundaries existed between them. An Arabic-speaking Jew was always a Jew, just as an Arabic-speaking Arab was always an Arab, and this distinction was never lost on anyone.

This is why the term “Arab Jew,” with its implication that the Jews of Arab lands traditionally thought of themselves as Arabs in much the same way, say, that the Jews of America think of themselves as Americans, is a historical absurdity.

Read article in full

Point Of No Return

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stepped dwellings from across bend in the Yantra River

Veliko Tărnovo, Bulgaria

The deep chasm of the meandering Yantra River creates a dramatic site for this historic central Bulgarian city, strategically located on the north-south route through the Balkan Mountain range. The old core covers three hills around the river, and buildings cling to the steep slopes. Fortified capital of Bulgaria's medieval kingdom and of the Second Bulgarian Empire, also a key trading center, the city had diverse residents and retains numerous historic structures. Old houses mix with newer structures above the river chasm. (photo 2000)

46 notes

·

View notes