#basics of gensokyo

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Basics of Gensokyo: The Hakurei Shrine

The Hakurei Shrine sits inside the border, the Great Hakurei Barrier. It's on the eastern side of Gensokyo. It is inhabitated by:

Reimu Hakurei

The Hakurei Kami/God

SinGyoku (unknown, no longer canon due to being PC-98)

Genjii (pond behind the shrine, dubious canon despite being a PC-98) (ZUN has stated he's there but no canon info exists)

The Three Fairies of Light: Sunny Milk, Luna Child, and Star Sapphire (tree behind the shrine)

Clownpiece (underneath the shrine)

Some other characters attributed to the Hakurei Shrine but are not permanent residents are:

Mima (haunts occasionally, no longer canon due to being PC-98)

Kana Anaberal (haunts occasionally, no longer canon due to being PC-98)

Suika Ibuki (visits)

Kasen Ibaraki (visits)

Shion Yorigami (temporary resident)

Aunn Komano (occasionally guards)

Originally, the Hakurei Shrine was the only shrine, before Moriya Shrine came to Gensokyo, in which then the Buddhist Myouren Temple and the Taoist Hall of Dreams' Great Mausoleum showed up later on.

The Hakurei Shrine also predates the existence of the Barrier, and is known to the outside world, albeit it appears old and abandoned there, but it is near a city. More info on its existence in the Outside World is unknown other than it being in Japan, obviously. Before the existence of Gensokyo, the shrine was maintained by the Miyadeguchi family, making it likely that Mizuchi Miyadeguchi is in somewhat linked to the shrine itself.

On the Gensokyo side, it's high in the mountains which is about an hour on foot from the Human Village. It's not a difficult trip, except for in heavy snow, but most humans don't make the trip due to danger of the trail.

Officially, the shrine neither exists in Gensokyo nor the Outside World, due to existing on the Hakurei Barrier. Traveling through the shrine to either other side requires certain unknown conditions to be met.

However, due to being on the barrier, items and people fall through the barrier from time to time. This leads for youkai and collectors alike to be very wary of the shrine, even if they don't always understand the items that come through.

The shrine is a hangout for lots of youkai, and is at the other end of an animal trail which is also frequented by youkai, so (normal) human visitors are quite slim. Even fewer humans leave donations, leaving for Reimu to live in relative poverty, though it's known that Yukari Yakumo makes donations behind Reimu's back to support her.

The God of the Hakurei Shrine is known canonically to be very angry at not being worshiped, in part because they no longer have much power due to it. It's possible that, if we follow canon lore about forgetting = vanishing, the only reason the Hakurei God still exists is because they technically have not been forgotten. This is also supported by the fact that Rinnosuke Morichika claims to know the name of the Hakurei God, and Byakuren Hijiri claims that she can sense that the God is very angry.

The Hakurei Shrine gives out omamori, but because of all of this, it's unclear if they actually work. No canon information exists on the effectiveness of the omamori.

The Hakurei Shrine has been attacked and even destroyed by youkai several times over the course of the games. It can still serve as a shrine in these cases, but not a place to live. It's usually rebuilt quickly, on one occasion by a group of celestials as apology from Tenshi Hinanawi from destroying it.

The actual shrine is old-fashioned and offers poor protection from the cold. There is a grove of cherry trees behind the shrine, which remains a particularly popular spot for flower viewing in spring, at least for youkai. There's a donation box, but it's usually empty. There also exists a warehouse for the shrine.

Since the events of Mountain of Faith, Reimu constructed a small shrine, about the size of a birdhouse, to Kanako Yasaka and Suwako Moriya at the edge of the Hakurei Shrine's grounds in an attempt to gather more faith for her own shrine. Despite its very small size, it does get occasional visitors from the Human Village.

Sources/Further Reading:

Hakurei Shrine | Touhouwiki

Hakurei God | Touhouwiki

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Pardon me making a more direct comment than a tag comment but I feel this is especially important for Touhou PCP so I wanted to talk about it a little bit! All of the advice above is good and I'm more explaining why it's so important to listen to for Touhou PCP and how their ages (both their mental age and how long they've actually existed) applies to their worship/working with.

Many Touhous are either directly stated/implied to have child minds (Remilia Scarlet, Flandre Scarlet, Eika Ebisu, any fairy, etc); or are commonly read as children or young teens though this depends where you look in the fandom (Rumia, Wriggle Nightbug, Mystia Lorelai, etc).

As fairies or youkai or even a God in the case of Eika, they might still have wisdom beyond a humans years, due to having lived much longer than humans. Even Cirno is directly stated to be at least 80, but as fairies are embodiments of nature in Touhou lore, she could be hundreds of years old, even older than characters like Remilia (500+), we just don't know. As such, they might have more wisdom than you give them credit for, even if it's all verbalized in a childs manner.

As well, they're way stronger than a human is (youkai are known to eat humans in Gensokyo afterall) and thus can still be called upon for help with spells and tasks, as long as they're acceptable to them, their interests, etc. Like you can ask Cirno for help in a binding spell, because Cirno loves freezing frogs in a block of ice - and what's so different about doing the same to a person or object to bind it? Just give her something she would like in return, like candy.

But, they are still children or teenagers, minors in the end. They have the minds of minors, and you should behave and act accordingly. Just because characters like Remilia act all mature, doesn't erase the fact that she's still a child. Even canon states that she may be wise and fearsome, but she's mostly bored and prone to childish whims to stave away boredom. (Note: Some fans, outside of the PCP scene, do debate whether or not Remilia can actually be read as a child mentally, but like I get into below, I err on the side of caution. Children can act "mature" and exhibit the traits Remilia does, especially when they've lived since the 15th Century, and still be children. Touhou lore states nothing about how actual age affects mental age for the case of vampires like how it states all fairies are effectively eternal children - and we also see Flandre, 450+ who is much, much more openly childish than Remilia and actually read as a child commonly, despite the sisters being so close in age. I'll get into this more at a later date I think!)

Some notable exception characters to the "they're youkai so they're probably still wise" would be characters like Sakuya, who is so far implied/stated to be human, and stated to be anywhere between 10 to 20, though also directly implied to be much older in an Imperishable Night ending. Granted, there's still many benefits to worshiping/working with Sakuya, but you might miss out on some of the benefits of worshiping/working with a "more than a humans lifetime" being.

"Khajiit, so many/most Touhous have unspecified ages and could be either a late teen or an adult!" Yes, and this brings us to a problem within Touhou PCP. Some people read our protags, Reimu Hakurei and Marisa Kirisame, as teens, others as adults. I don't really know if there IS a right answer to a question like this, but my suggestion is to err on the side of caution with any true age uncertainty for a Touhou. I generally err towards "Reimu might be a teenager..." even though it's just as possible for her to be a fully grown adult. Because, y'know, caution!

Anyways, that's all I have to say for now. Touhou PCP fun I have many emotions about it

I'm asking genuinely as a fellow PCP'er, but how do you work around worshiping/working with characters who are minors, if you adjust anything at all? I keep feeling like I need to walk on eggshells when it comes to it and adjust a lot of things about my usual route to be moral and just, or just plain not do it at all and I'm not sure the correct route. I know you have a lot of experience with PCP in general so I'm wondering your thoughts on the matter

Heya, Nonny!

So I talked to a fellow PCP'er (thanks @jasper-pagan-witch) and we both agree that you can absolutely worship/work with minor entities! There are a lot of things they can teach us or help us with. There are just a few things to remember if you do intend to interact with a minor entity:

1.) Stick to the entity's scope of knowledge for their age/world. Meaning you wouldn't ask Ash Ketchum (Pokémon) how to do your taxes or Sasuke Uchiha (Naruto) how to prepare for the bar exam because that is beyond their scope of knowledge and experience. Focus on the topics that they would know and understand.

2.) Treat them with the same level of respect you would an adult entity. Do not talk down to or disrespect an entity because you are older than them or know more on a certain subject. They deserve the same respect you would give any other entity in life.

3.) Be mindful of what you say and how you act. However, you do not have to walk on eggshells while working with minor entities. Just act how you would in front of a minor outside your practice. Minors can handle curse words, but there are certain topics that should be avoided, depending on the character's age.

4.) Don't be a creep. Do not engage in romantic or sexual relationships with minor entities. Do not ask minor entities for sexual advice. This shouldn't have to be said, but it does, so I'm here to say it. Don't be a creep.

5.) Learn to have fun with it! Let them teach you how to find that inner kid inside. Let them show you how to make new friends or follow your dreams. Minors have so much to teach us and they shouldn't be discounted simply because they are under the age of 18.

You don't have to avoid working with minor entities simply because you are over the age of 18. Minors have so much they can offer us! I hope this helps, Anon!

~Crimson

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

I mean that's kinda the point, isn't it?. The threat that they might do it regularly is more terrifying than if they do or not.

that's literally it yeah but it leads to the endless argument of whether or not they actually eat people (or whether or not they need or even want to do it, since they're sustained off the human fear they're getting anyway)

#i've always felt that trying to focus on the idea of youkai eating people is trying to make gensokyo too basic of a Fucked Up Place#when it's already extremely fucked up but in far more complicated ways than people being eaten#applying 'what if there was a scary monster that eats you' to touhou will always be less engaging than what's actually going on

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

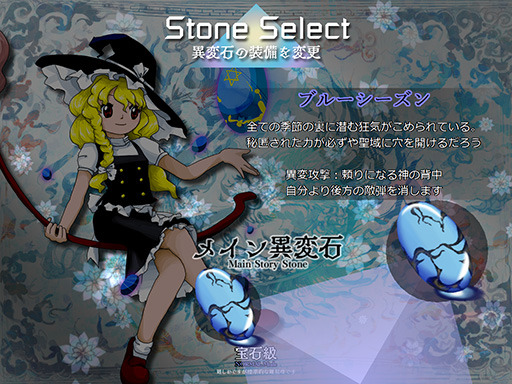

The unofficial translation of Gensou Narratograph is now available to download! (PDF only or .rar file with bonus assets)

I know no one ever actually looks at tumblr blogs, but I've made a basic page to hopefully collect information and links in the future.

An unofficial tabletop RPG published by Kadokawa. While the game as a whole is by no means "canon", it includes a full transcript of a game session with ZUN as one of the players, plus new character quotes and location descriptions written by ZUN, so it's worth checking out just for that alone.

Narratograph is largely boardgame-based, played with a selection of 30 characters gathering clues on a map of Gensokyo to progress through objectives and resolve the incident/kerfuffle of the week. However, it is still an RPG, with every scene being roleplayed and the incident also having a proper story to it. Narratively the game leans towards the light and feel-good end of Touhou fanworks, though I suppose it's up to you what you do with it. The book includes two prewritten adventures as examples, one of which I've run for a group to test it out.

It has pretty digestible mechanics, and a very unique danmaku combat system. To help with the number of sheets, figurines, tokens etc. needed, I've made public the Tabletop Simulator mod that I use to run the game myself, together with character figurines. You can use the assets included with the game to try and make it work in some other virtual tabletop of your choice. Or of course, you can also just print everything and play it live, if you can get a group together.

The rules have some quirks, and I'll try to figure out the best way to post my own notes and suggested houserules. As things stand, though, despite having nothing to do with the game officially, after putting a lot of work into it, I'm also curious to hear anyone's thoughts or experiences running it!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Here, have a fairly light sketch dump with two relatively complete sketches and some of the process for the main Zanmu one. Also, Gensokyo's specalist girl makes an appearance here too

Artist's Notes;

Zanmu is such a fun character to draw, like, there's so many little aspects in her design that you can emphasize, and her colour palette is so satysfying too. The reason I ended up drawing this was because when I was scrolling on Pinterest I found a specific pose that just screamed Zanmu to me (it was the skull that did it for me) and I just had to draw her in that pose. I did end up taking my liberties with my reference though, and also I am not drawing feet, I just straight up don't like it, and this is mainly something more on the sketchy side so it didn't really matter lol. Also, IDK too much about the hands, I'm usually pretty good with them but I struggled with them a bit this time. Also Zanmu is sitting on nothing because I just didn't feel like drawing what she was sitting on (plus I already drew in the clothes and including what she was sitting on would mean having to change the sleeves and I just didn't wanna do that lol). Also realized that I should probably start trying to improve on drawing frills in clothing, and I tried a new technique for drawing them. I do like how they look, but at the same time it can still be better.

I do love how Zanmu's pose turned out the most in this batch of sketches. In my process, I put the reference image on the canvas and then roughly blocked in the silhouette. One change I knew I wanted to make since the beginning of the sketching process was opening up the space between the bent arm and body more, mainly to make the silhouette of the pose clearer (even though with the addition of the clothes it does get closed up a lot). I also wanted to turn the torso towards the viewer and change the position of the legs to something more cross legged/casual. In another sketching pass, I just kinda quicjly scribbled what I wanted the pose to look like just so I could get my idea out and I'm glad I did that because that helped me focus more on the pose itself rather than the small details. Afterward, I did a sketch of the body, clothes, and hair all together and then coloured it to get the coloured Zanmu sketch!

Again, I could've done a better job with the feet and the legs themselves for that matter, but the nice thing about sketches is that they don't need to be perfect, and I was more so focused on the gesture/feel of the pose rather than the minute details. With her facial expression, I knew that I wanted something very specific with her eyes, so I just simplified it into this "almost closed" eye and I do like how it turned out a lot. Also, a problem that I often have drawing Zanmu is that in the poses I put her in, I don't really know how best to draw in those triangle cut outs she has, so instead, I added these little triangle details onto her sleeves and pants to add some visual interest and allude to them instead, also because they can kinda allude to a crown and Zanmu is the king of Hell so it fits lol (also, love it when people add details like that onto sleeves sm lol). The hair and tassles did a lot of heavy lifting when it came to making the drawing have a nice flow to it, and I have the headcanon that Zanmu is just able to make those float on there own by.... honestly I don't know, I just like the idea of her tassles defying gravity and floating all the time. Also IDK if you can see them, but I did make sure to include her scars as I'm basically adding that as a part of my way of drawing Zanmu. It just adds a certain something, y'know? Also found a specific reference for the skull and made it the red that it is in Touhou 19, and also because drawing skeletons and skulls is just fun lol.

Now onto Reimu, so that face drawing was mainly there just so I could get a better idea of how I wanted to draw her face in the future. My main concern was trying to make it different to Keiki and Zanmu's faces, so as I was sketching hers I had the drawings of Keiki and Zanmu's faces turned on to make sure I wasn't drawing the same thing again. Down here I included this little test I did where I hyper simplified the eyes of the three faces and just traced over their face shapes, noses, eyebrows, and mouths. While the nose is the most consistent trait shared among the three of them (tbf that can just be chalked down to an aspect of my style), I feel like the three are different enough from each other to where they don't have same face syndrome, even if you simplify the eyes into dots and also didn't include the detail of Zanmu's scars on her face.

I'm obsessed with giving Reimu these tiny little eyebrows for some reason, IDK it just works for her. I also really like using a red as a highlight for whenever I draw her hair black, mainly because it helps to give the illusion that her hair is just a really dark brown and incorperates her main colour of red into another aspect of the design. I also wanted to try and draw Reimu's eyelids differently to try and imply monolids but tbh IDK how well that reads. I also like how her pupils turned out, as I'm experimenting with different characters in my style having different kinds of pupils. I didn't even bother properly rendering her clothes, so I just did them linelessly (I think I wanna try drawing in my lineless style again for a future piece sometime as I kinda miss the feel it had). I of course had to give Reimu her big bow, and also use that specific shade of red. IDK what it is about that shade of red specifically, but I just love it, it looks so nice to me you have no idea- Now that I think about, I kinda wanna draw Reimu more now, as I feel like I can still do some more experimenting with how I draw her eyes specifically. Also because I've got some ideas when it comes to how I wanna draw her body type.

#touhou project#art#fanart#sketch dump#digital sketch#zanmu nippaku#touhou#reimu hakurei#touhou 19#unfinished dream of all living ghost

224 notes

·

View notes

Text

it's also really funny for byakuren "youkai and gods are basically the same thing" "mastering forbidden magic so I never have to die" "head of one of the most prominent religious organizations in gensokyo" "actively running a cult of personality without realizing it" hijiri to say that the pursuit of power will destroy you

but that's pretty standard byakuren stuff. she's such a dipshit. I love her so much.

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

"You'd rather die than stay with her"

A short comic

This is the rambling part for people asking "Why is Kaguya so emotional?" , you may go now

Ok so, you may ask

My headcannon of Kag basically leaning more in the aspect of her becoming more human, in honor of the og myth. It is a story about humanity and how strong it is.

In Touhou case, we can already see that with Keine and Mokou of how the Mok rejoin society of after years of losing her humanity then finally gain it back.

On the other hand, we have Kag, a lunarian that gain humanity through her foster parents, but it's incomplete. Hence the blood battles, both doesn't have their complete amount humanity(I don't know other words to describe this) , one lost it though time while the other only gain part of it

So Keine this humanizing therapy machine goes pops two of those gauge to the max.

Thing went okey dokey with the cinnamon roll that is Mok since, she was a human at one point, Keine just have to pull that shit out of the dark murky depth.

Kag basically got introduced to thing she can't comprehend, yeah she know what love is and how beautiful human can be. But now she have to roll on ground with it, get dirty up in the Earthliness and experience all the good and bad * *cough* * **the demon whore of love** * *cough* * . She's already in the muddy place that's Earth, where there the highest of high and the lowest of low, and Gensokyo, why not have the full experience

Keine tho, she's struggling with her own humanity because of the half beast thing, the responsibility and gaze from the village definitely take a toll on her. And now she have two walking calamities on her side. Then Eirin pop the fucking question and ask if she want to throw away her humanity or die

Wait I was writing for... Oh yeah,

Soo, Kag have emotion now

#touhou project#touhou fan comic#東方project#kagukeine#keine kamishirasawa#kaguya houraisan#eirin yagokoro#fujiwara no mokou#touhou#touhou doujin

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

As much as I wish I could reliably and always say "You can worship/work with whoever from pop culture paganism (PCP) or perform pop culture witchcraft (PCW) without knowing their source", knowing their source will help you with your worship/working relationships and your practice.

You can worship Akatosh without knowing anything about The Elder Scrolls. You very well can. It'll go just fine as long as you understand Him. But you'll ultimately be lacking important context on the world He comes from and how that relates into Him and His worship.

It's like... I didn't study HelPol very well when I began worshiping Zeus. I'm still working on rectifying that. But while I could go with information that was easily available about Zeus alone and have a very easy time worshiping Zeus, I ultimately stagnated because I didn't properly understand Zeus within the context of where He comes from and everything else about HelPol like khernips, Hellenic rituals, and all that sorts. I just went "I know about Zeus, so I'll be fine" and it technically was fine, I had (still have) a good, healthy relationship with Zeus, He didn't really complain at or about me, and I didn't come across any problems in our relationship, but the general HelPol part of my faith faltered, struggled, and stagnated, and that did affect my relationship even if I didn't realize it. I couldn't worship Him at His complete fullest.

The same applies to pop culture paganism.

You can worship Akatosh, you can follow His commandments, but with knowing literally nothing or next to nothing about the world, you're going to hit a wall. And yeah, Akatosh might not be the best example, because canonically we don't know much about His worship, comparatively to Zeus where we know so damned much about His worship; but it's still a truth I've found to be true.

I may joke about converting people to Touhou PCP because I think it's funny to joke about (it might not be but humor is subjective), but I wouldn't genuinely say to do it unless you're willing to put in time to at least understand the setting of Touhou, Gensokyo, and how that setting affects their lives. Understanding basics like the Spell Card rules even is a long way.

I'm not saying you need to be an expert in whatever source you wanna do PCP for. If it's a show you don't have to have seen every episode, for a game you don't have to have played every one or 100%ed it. You don't have to study every single page of every wiki that exists. I may be feral about my PCP sources but you don't have to be. But you should at least try to understand their source, their world, and how that can relate into your PCP, or even your PCW, before you really settle in and begin.

I'm also not saying every source has great information sources. Touhou worship for instance is hero worship in most cases of the 180+ characters (there's only 24 "Touhou original" gods, as in not kami taken from actual Shinto lore), and most Touhous appear once in a game then maybe if they're lucky, the print works, but the PC-98s? Like Sariel? Fuck dude there really is nothing. But learn what there IS to learn, y'know?

Don't let this stop you from getting into PCP. Or anything for that matter. Just do your best. I believe in you.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shingyoku lore post [LONG POST]

I made this as a little introduction to my Shingies's personalities headcanons. This is a post for those who wished to know about it because I cant recall making a proper post for that. Orochi and Toru are personal names I give to "the human-like forms" of the Touhou HRtP boss Shingyoku. Fair warning were very much entering OC territory here.

Or rather, this is a resumed introduction. I wont go into details too much here, as Id prefer to share it in a different format. For 2025, Ill introduce it through a series of posts starting from the very beginning of this story, each part with a drawing to go with it, because I think it will be better rather than one post with a massive wall of text.

My direction for Shingyoku is to do a mix of the "2 distinct entities" and "same person/shapeshifter" routes. Usually headcanons pick one of the two takes. I came up with a story which is very headcanon heavy and can be read by people who know nothing about Touhou as it barely refers to its codes or established figures.

(Its important I first state that they lived during edo Japan (early to mid 1800) and not Gensokyo.)

Orochi is from an upper class family. Her family were merchants from west Europe who found success and settled down in Japan before strict laws established regarding oversea traffic. Being the 2nd child, the focus of attention was pushed onto her older brother who would later lead the family. Orochi spent her early childhood raised by her retired great grandfather who gave her a taste for adventures telling of his past oversea travels. He would however pass away of old age, and Orochi would get entrusted to a shrine her family has a long, great partnership with, the "Shrine of Borders", which is the central location of this story, the shrine getting this name due to its location next to mountains speculated as housing entrances to underworlds. Her family often sending funds to the shrine, as their connection had started decades ago at the contruction of large gates said to prevent intervention of the supernatural from said underworlds.

Toru's backstory is long and complicated, as he's a part of the shinto god of the moon Tsukuyomi who landed on Earth, and the unfolding of events which led to this happening needs a post of its own since it dives a lot into shinto mythology. But basically, he landed on the grounds of an isolated fraudulent shrine led by fanatics, and ended up running away with a miko who had already questionned their doings. But later on, due to how harsh life would be at this time for a single adult and a child in the countryside, she wouldnt be able to provide him care and entrusted him to a shrine, which coincidentally, was the Shrine of Borders.

Both of them arrived at the shrine at about the same time (they were 8 years old). Toru was adopted by the shrine's head priest, Orochi was raised in a nearby village by retired mikos, but they got their traditional training at the shrine together. They quickly became very close friends (even if they fought a lot at first).

They underwent their initiation rite in their early teen age. They would communicate for the first time with a deity, "Shingyoku", who claimed to have been in a deep slumber for a very long time, the arrival of the pair wakening it. Shingyoku had no body of its own, but the pair would allow it to join the physical world of the living once they'd each reached enlightement. Orochi and Toru would report it to the head priest, who wasnt familiar with the name "Shingyoku", the Shrine of Borders having a long history of struggles communicating with the local god. In this story, Shingyoku makes it clear that its the deity of the shrine's pond and not the borders gates despite what HRtP make you theorize due to the boss's location; in this take the gates are purely human made. Because Shingyoku had no body of its own, it would try to possess people to use their bodies as a vessel, but because it had only weak powers, it could only possess for a short amount of time like possessing Orochi or Toru to communicate with them, or small animals, its favorite being the pair's pet koi fish from the shrine's pond.

For a couple years, the story focuses on Orochi's and Toru's daily life and duties at the shrine, but is relatively mundane, as I said is detached from Touhou codes and doesnt take place in Gensokyo, so it rather refers to history at that time with a small hint of fantasy with occasional intervention of the supernatural, youkais's appearance following more how they were depicted in art of the time. People also dont have magical abilities, there are no such things as bullet battle and spell cards. Orochi is skilled at some martial art due to a personal intensive physical training; Toru acquire healing abilities only due to his godly nature. They would share tasks and complete each others with what theyre best at.

Once in their early twenties, Orochi was summoned back to her family's home to lead as her older brother perished in battle (indicative to more events happening at the time approaching end edo). She would take Toru as her spouse, but as they would grow so much stress from the marriage's and leading's expectation coupled with the shut in life, they would end up running away without a word 4 years later.

They would escape and live isolated in the mountains close to the Shrine of Borders so they could be remotely close from Shingyoku, where they would dedicate their lives serving their god.

A decade later, they would reach enlightement, but passed away as their mortal bodies couldnt handle it (and the harsh living conditions).

Shingyoku, still using the koi fish's body as a vessel, swam up the mountains to reach the pair whose spirits parted from their bodies and fused into one. Shingyoku absorbed the fused spirit, acquiring the pair's powers, allowing it to transform into a dragon before setting the pair's body on fire (to spare them a trip to the Yomi, the "shinto hell", which has a capital importance later in my whole story but isnt part of Orochi's and Toru's story).

*I use "fusion" as an umbrella term, but as explained here, its not a straight up fusion of the 2 people's body fusing into one. Here the deity and the 2 shrine officiants are distinct people, the officiants serving the deity, and the deity later absorbing the officiants's spirits to acquire their powers after reaching enlightement. Shingyoku the deity shares no DNA with Orochi and Toru, the body of the koi fish, which then transforms into a dragon, ended up being its official DNA. The separation is capital for the following part of the story which focuses on Shingyoku's life after joining the physical world of the living. But this will be for an other post, as the focus here was on the miko and the priest.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apparently some fans think every 60 years "equals" 1 youkai year, but that's so odd to me. They use it to state Remilia and Flandre would be about 8 and 7 respectively... but that also would throw SO many other known character ages into chaos. So I don't follow that, plus Remilia genuinely gives me more the vibe of a pre-teen (outside of UPG stuff)

Every 60 years, the event as seen in Phantasmagoria of Flower View happens because of reasons (too long for this to explain), but I've never actually seen anything canon about "every 60 years is about 1 year for a youkai"... youkai aren't experiencing time or necessarily aging differently to humans. They just don't age. If they do age like this, then all youkai in the series would likely be children or teenagers. Because you all realize 60 years is a long time, right? Even if all youkai in Gensokyo are way older than we think, that's still a long time for 60 years to equal 1 youkai year.

Let's assume Yukari's age. She's at least 1,200 years old. If 60 = 1, then she'd be 20. You think this grown ass woman is only 20? "But Khajiit, Yukari is likely way older than that!" Yes, fair, but Yukari is a fully grown woman! Mentally as well, she's definitely not only 20!

We don't even know WHAT causes youkai to be born - if they're born at all. For all we know, they just [ pop ] into existence outta nowhere and outta belief in them, especially if lack of belief makes them vanish/die.

I just heard this statement not long ago and I have... Thoughts about it.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

be me ruby alchemist cute, smart, like those are my only stats everything else? dead inside like, literally can't feel emotions as well as a normal person go to gensokyo to fix that doing alchemy things, kinda vibing ig then mirror witch shows up like actually lets me feel human emotions it's like emotional weed i'm not ok but also never better then a dog shows up in my mirror tells me to sacrifice my emotions for 'greater cause' and 'perfection' ok???? ma'am this is fairy tail she's an evil witch sealed in a book but i said 'yes' bc im curious shouldn't be so impulsive otl also theres boy whos my test subject one year younger can shapeshift into me but with, like, 200% more emotions he's extroverted, sparkly, dramatic, cries alot probably basically me if i had access to feelings and stuff and he's loved by so many people including a goddess i can't now I got a mirror witch who's like a feels dealer a cryptic dog trying to suck my emotions dry and a boy who's way more emotional than i'd like i want to put all three of them in a dumpster and set it on fire mfw

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

reimu and marisa have actually been married since shortly after the events of subterranean animism as part of an effort to avoid a proposed political marriage between reimu and sanae (suggested by kanako, of course). however since this has no real functional meaning in gensokyo it basically only comes up whenever kanako brings it up at parties

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Tenma, boss of the tengu". Exploring the "heavenly demon(s)"

The identity of Tenma, the leader of tengu in Touhou, remains a mystery. I think only ZUN can solve it - if he ever chooses to, obviously. Therefore, this is not quite an article meant to prove I figured out who Tenma is. Instead, it presents the origin of this name, and introduces a handful of figures in various contexts portrayed as leaders of the tengu who I think would be interesting candidates for the position of Tenma.

My additional goal is to show that even though popculture tends to portray all tengu as basically interchangeable, there is actually a fair share of unique tales about specific named members of this category. Corrupt monks! Vengeful spirits! Visitors from far off lands! There’s even a sea monster converted to Buddhism! Obviously, this isn’t supposed to be a list of every single named tengu and every single story. It’s not even a list of all of my favorite tengu. It’s simply an attempt at convincing you that digging deeper into tengu background is worth it - and in particular that there is still a lot to speculate about when it comes to their leader in Touhou. It’s some of the best oc free real estate in the series, really. Due to technical difficulties, the bibliography is included as a Google Docs link rather than a part of the article. I'm sorry.

From Mara to tengu: the development of the concept of tenma

Silhouette of a tengu negotiating with Kanako in WaHH 38, sometimes labeled as Tenma on fan sites through debatable exegesis.

As we originally learned in Perfect Memento in Strict Sense, Gensokyo’s tengu are ruled by an individual named Tenma (天魔). Akyuu simply describes them as the “tengu’s boss” and provides no further information. While some additional tidbits have since surfaced here and there, they largely remain a mystery. Next to Chang’e, the unseen fourth deva of the mountain and the fourth Beast Realm figurehead they’re easily the highest profile unseen character in the entire series.

While in absence of information on the contrary we cannot necessarily assume that Tenma isn’t a given name in Touhou, ZUN did not actually come up with this term. It has been a significant part of tengu background at least since the Kamakura period. It can be translated as “heavenly demon”, and it’s a shortened form of Dairokuten Maō (第六天魔王), “Demon King of Sixth Heaven”, the Japanese name of Mara. Tenma is explained as a synonym of Mara’s “personal name” Hajun (波旬; Sanskrit Pāpīyas) for instance in the treatise Makashikan (摩訶止観; translation of Chinese Móhē Zhǐguān, “Great Cessation and Insight”).

Is that all there is to the mystery of Tenma? For what it’s worth, a possible reference to the full form of Mara’s name can be found in a description of Okina’s ability card in Unconnected Marketeers, which mentions “Tenma living in paradise”. I don’t think this is very strong evidence, though.

Touhou aside, it is hard to deny tengu are fundamentally tied to Mara. They are directly described as his subjects in Buddhist works such as Soseki Musō’s (1275–1351) Muchū mondō (夢中問答集; “Questions and Answers in Dreams”) and Unshō’s (運敞; 1614–1693) Jakushōdō Kokkyōshū (寂照堂谷響集). However, it needs to be stressed that a being referred to as Tenma does not necessarily have to be Mara himself.

A plurality of Maras theoretically became possible as soon as the belief this name didn’t designate an individual, but rather a position which could be held by various individuals or a category of beings developed in Buddhism. The former idea already appears in the Māratajjanīya, a part of the Theravada Buddhist Majjhima Nikāya, dated to the late first millennium BCE or early first millennium CE. Maudgalyāyana, one of the disciples of the historical Buddha, reveals in it that he was (a) Mara in a past life, and thus can easily notice the presence of the present Mara. The shift from a singular Mara (魔, mo) to an assortment of “demon kings” (魔王, mowang) is also well documented in early Buddhist sources from China.

As a curiosity it’s worth noting that even though the terms mo and mowang originally referred to strictly Buddhist demons, they were also incorporated into Daoist traditions, especially Lingbao and Shangqing. For example the former school's central text Duren Jing (度人經; “Scripture for Universal Salvation”) maintains that multiple mowang exist. While some of these “demon kings” are tempters not too dissimilar from their Buddhist forerunner (though what they obstruct is attaining the distinctly Daoist form of transcendence - in other words, immortality), others are portrayed as judges responsible for determining the fates of people in the afterlife. In later sources the term mo sometimes also refers to supernatural pathogens (generally 邪, xie or 邪氣, xiequi).

Sun Wukong and his fellow pilgrims battling the Bull Demon King on a mural from the Summer Palace in Beijing (wikimedia commons)

You don’t really need to look for any particularly obscure sources to see this transformation of Mara into a generic moniker, though - even the Bull Demon King from Journey to the West has the compound 魔王 in his name. Same goes for numerous other antagonists from this work.

When it comes to Japanese sources, it also doesn’t require looking for anything particularly obscure to find evidence in the belief in multiplicity of ma or tenma.

In the historical epic Heike Monogatari, emperor Go-Shirakawa implores Sumiyoshi Daimyōjin to explain the nature of tenma to him. He reveals that this term refers to monks and scholars who, despite nominally following Buddhism, lacked the mindset needed to attain enlightenment. He compares them to birds of prey, but also states they belong to the “dog species”. All of these are nods to well established beliefs about tengu, which I discussed in my previous article, with a reference to the writing of their name on top of that. It comes as no surprise that right after that Sumiyoshi Daimyōjin specifies that “the wise men of the eight sects who become tenma are called tengu”. He also makes it clear the tenma are quite numerous: “nine out of ten will definitely become tenma and try to destroy the Law of Buddha,” he warns.

A plurality of tenma can also be found in assorted biographies of pious Buddhist reborn in a pure land, so-called ōjōden (往生伝). The Tendai treatise Asabashō (阿娑縛抄) attributes the ability to “subdue all tenma” - evidently a class of beings, not an individual - to Fudō Myōō.

Through the rest of the article, I will introduce some of these tenma - the most famous tengu. My goal is not to convince you that any of them is a uniquely plausible candidate for the role of the unseen Touhou Tenma - I merely would like to point out there are multiple interesting options.

The oneness of vice and virtue: Ryōgen, the ruler of Makai

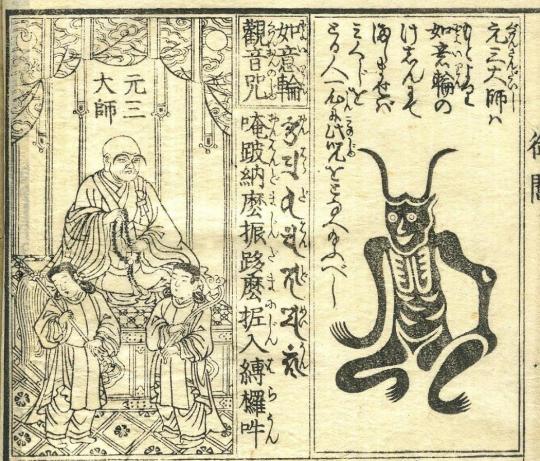

The historical Ryōgen (left) and his deomic alter ego Tsuno Daishi (wikimedia commons)

Before Ryōgen (912–985) came to be seen as a tengu, he was one of the most influential members of the Tendai school of Buddhism to ever live. He reformed the Enryaku-ji complex on Mt. Hiei, took part in numerous theological debates, and gained the favor of the imperial court by supposedly enabling the birth of an heir of emperor Murakami with his prayers. He was also renowned as a master of esoteric protective rituals.

The proponents of the Tendai establishment understood him as a fearsome protector of this tradition. As early as 50 years after his death, in the 1030s, he came to be identified as the reincarnation of Tendai’s founder Saichō. He was also considered a manifestation of one of the eight dragon kings, Uhatsura (優鉢羅; from Sanskrit Utpalaka). Ōe no Masafusa states that in this form he continued to protect Mt. Hiei, instead of being reborn in a pure land. This idea continued to spread, and by the end of the Kamakura period he came to be commonly revered as a protective figure by all strata of society. Haruko Wakabayashi notes that only Kūkai developed a similar cult in Japan as far as patriarchs of the esoteric Buddhist schools go.

It was not Ryōgen’s ability to navigate complex doctrinal debates about the interpretation of sutras that resulted in his popularity, but rather his esoteric skills. He was supposedly uniquely accomplished when it came to subduing anything which could be described as ma. In a Konjaku Monogatari tale I’ll discuss in more detail later, he effortlessly overcomes a tengu, for instance. However, in addition to spiritual obstacles and demons, the ma he was supposed to conquer also included political opponents, rebels or brigands, as the Buddhist law and the interests of the state were understood as identical. Ryōgen’s efficiency was so great he came to be viewed as a manifestation of Fudo Myōō, one of the wisdom kings and the conqueror of ma par excellence.

Not everyone viewed Ryōgen positively, though. The earliest criticism came from his contemporaries. It was argued that he favored monks from aristocratic families, and that he lived in luxury unbefitting for a monk. Furthermore, numerous conflicts between monks erupted during his tenure as Enryakuji’s abbot, including the split between the Sanmon and Jimon lineages. Since in some cases this led to armed confrontations, later on he was blamed for essentially enabling the rise of militarized monks who commonly caused disturbances on Mt. Hiei.

The real breakthroughs were not these tangible “political” criticisms. Rather, it was the identification of Ryōgen as ma, which arose due to conflict between various schools of Buddhism in the early middle ages. Most commonly this meant portraying him as a tengu - as I explained in my previous article, the form arrogant or corrupt monks were believed to take. A variant tradition described him as an oni, though according to Bernard Faure this likely simply reflects a degree of interchangeability between them and tengu.

Ryōgen is arguably the most famous historical monk to be furnished with such a literary afterlife. An early example can be found in the Hōbutsushū from the twelfth century, which states that this was a result of his attachment to Enryaku-ji. In Jimon Kōsōki (寺門高僧記) it is instead his investment in doctrinal debates that made him unable to attain rebirth in a pure land.

A gathering of tengu leaders from Tengu Zōshi (wikimedia commons)

Since Ryōgen was no ordinary monk, his tengu self also had to be special. In the Tengu Zōshi (天狗草紙), he is described as the ruler of all tengu and the realm they inhabit, Makai (“world of ma”; also referred to as Tengudō). It's worth pointing out the notion of Makai being a place where monks turn into specific classes of supernatural beings is basically a core part of UFO’s plot, and in SoPM Miko even wonders if Byakuren shouldn’t be considered a tengu.

As a ruler of Makai, Ryōgen came to be referred to as a “demon king”, maō (魔王). An example can be found in the historical epic Taiheiki, where he is described as one of the “great demon kings” (大魔王, daimaō) who debate how to cause chaos in Japan. He is assisted by vengeful spirits of the emperors Sutoku (more on him later), Go-Toba and Go-Daigo; two members of the Minamoto clan who sided with Sutoku, Tameyoshi and Tametomo; and the monks Genbō, Shinzei (真済, 800-860; obscure today, but apparently well known as a monk turned tengu in the middle ages) and Raigō (who supposedly turned into the infamous “iron rat”).

In Hirasan Kojin Reitaku (比良山古人霊託; “The Spiritual Oracle of the Old Man of Mount Hira”) this is only a temporary fate, though: supposed by the time this work was compiled, he already managed to leave Tengudō. As I discussed last month, this reflects a fairly standard belief too: to become a tengu, one had to actually be a Buddhist, and while it made striving for enlightenment more difficult, it did not mean eternal damnation or anything of that sort. A tengu could still choose to pursue rebirth in a pure land - it was just more difficult than for a human.

The evolution of Ryōgen’s image didn’t end with the establishment of his new role as a king of tengu, or even with the arguments that he might have nonetheless subsequently attained enlightenment. By the end of the Kamakura period, he came to be worshiped explicitly in the form of a “demon king”. While initially polemical, this image of him came to be subverted by Tendai monks to their own ends. They asserted that Ryōgen did not enter the realm of ma because of his arrogance, but rather consciously chose to do so in order to protect Buddhist principles. By becoming the ruler of its inhabitants, he also became their ultimate conqueror.

The notion of a being who is simultaneously essentially Mara-like and a protector of Buddhism seems contradictory. That’s actually the intent here. Through the middle ages, the esoteric schools of Buddhism developed the notion of hongaku, or “original enlightenment”. In its light, opposites were in fact identical. Buddha was the same as Mara (魔仏一如, mabutsu ichinyo). As it was argued, to attain Buddha nature one had to understand and experience delusion as well. Thus virtuous individuals could become demon kings in order to freely control evil beings.

In addition to its deep philosophical implications, the hongaku theory was also used to reject criticisms of the Buddhist establishment. Enjoying luxuries was but a way to better understand delusion, and thus to advance along the path to enlightenment. Its proponents embraced some criticisms of Ryōgen: he did favor nobles, accumulate wealth and live arrogantly. He did become a powerful tengu. But all of this was in fact part of a noble goal. And on top of that, as a demon king he was an even more fearsome protector of Tendai than he would be otherwise.

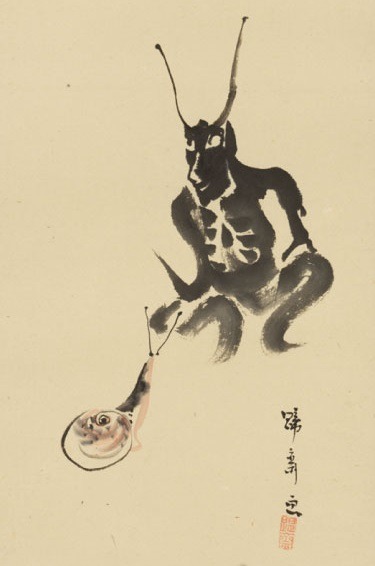

"Tsuno Daishi and a snail" by Teisai Hokuba (Sumida Hokusai Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

The new role of Ryōgen warranted new iconography. While formerly portrayed simply as a monk holding the expected priestly attributes, in the Kamakura period he came to be depicted as Tsuno Daishi (角大師), the “Horned Master”. This image spread far and wide due to the development of a belief that hanging depictions of Ryōgen would guarantee the same protection Tendai institutions received from him. He came to be seen as particularly efficient in warding off disease. Many temples still distribute talismans depicting Tsuno Daishi today. This custom received a lot of press coverage in the early months of the COVID pandemic, and you might have seen some examples on social media. From vengeful spirit to tengu: the case of emperor Sutoku

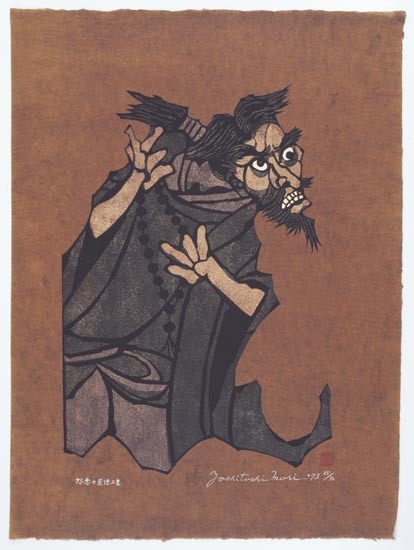

Sutoku, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Mori (Tokyo's National Museum of Modern Art; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Sutoku has much in common with Ryōgen - he was also a historical figure who purportedly became a tengu. However, he was not a monk, but rather an emperor. He reigned from 1123 to 1142, when he was forced to abdicate in favor of his half brother Konoe.

Konoe passed away in 1155, but Sutoku was not allowed to return to the throne. It was instead claimed by another half brother, Go-Shirakawa. Sutoku decided that’s enough half brothers seizing a position he believed was still rightfully his, and plotted an uprising. This culminated in the Hōgen Disturbance of 1156. Alas, planning seemingly wasn’t his strong suit, since the conflict was essentially resolved before it even started. Go-Shirakawa’s forces defeated Sutoku’s before they even left their encampment.

Sutoku as a vengeful spirit, as depicted by Kuniyoshi Utagawa (wikimedia commons)

In the aftermath of his failed rebellion, Sutoku was exiled to Sanuki, where he eventually passed away in 1164. However, his memory lingered on. He most likely came to be widely perceived as a vengeful spirit after the great fire of Angen broke out in Kyoto in 1177. Other subsequent disasters, including the Genpei war (1180-1185) and the 1181 famine, strengthened the belief that he was punishing his enemies from behind the grave. However, he didn’t become just any vengeful ghost, but one of the three greatest members of this category ever, next to Sugawara no Michizane and Taira no Masakado. Sutoku was, in a way, the sum of many of the greatest fears of medieval Japan. The belief in his rebirth as a vengeful ghost coexisted with a tradition presenting him as a tengu - arguably one of the greatest tengu ever. This status is firmly ingrained into his image in later sources. Today he is frequently included in modern groupings of “three great youkai” alongside Shuten Dōji and Tamamo no Mae. It seems sometimes he’s replaced by Ōtakemaru, but honestly I think he is more worthy of this spot, and also even though this is ultimately a synthetic modern group, it’s much more representative of medieval culture to have a tengu alongside an oni and a fox.

A strikingly tengu-like vengeful Sutoku, as depicted by Yoshitsuya Utagawa (wikimedia commons)

While peculiar, Sutoku’s dual role as a tengu and a vengeful spirit is not entirely unique. Initially these two categories were pretty firmly separate. Tengu obstructed attaining enlightenment and rebirth in a pure land; vengeful ghosts, as their name indicates, were focused on personal vengeance. However, in popular imagination they overlapped, as evident for example in members of both groups scheming together in the Taiheiki. This most likely reflects the overlap between the perception of enemies of Buddhism and enemies of the state. Vengeful ghosts were typically members of factions who lost one political struggle or another, and their vengeance was aimed at the establishment.

Regardless of Sutoku’s supernatural taxonomic position, his post-mortem fate is tied to the fact he was a devout Buddhist. All accounts of his exile stress that he spent much of his time copying sutras. According to a rumor first attested in 1183, he also wrote a curse on their backs using his own blood, vowing to become a “demon king” - (a) Mara - due to perceived injustice he faced. There is no evidence it’s based on a historical event, even though it’s not impossible Go-Shirakawa did believe in it. At the very least, he definitely saw the deceased Sutoku as a supernatural threat, as he had various ceremonies performed in hopes of pacifying him.

Hōgen Monogatari, composed in the early fourteenth century, asserts that he became a tengu while he was still alive. When his request to deposit the completed manuscripts in a temple in Kyoto was denied by Go-Shirakawa, he vowed to remain his enemy in future lives, and stopped cutting his nails and hair. This symbolically marked his transformation. However, a former emperor couldn’t just become any tengu. Therefore, for instance in the Taiheiki he is described as a leader of the tengu, and his bird form is that of a golden kite.

Up to 2022, the Touhou wiki used to claim that “among Touhou fans, it is almost a general idea that the Tenma is inspired by Grand Emperor Sutoku” (not sure what is the “grand” doing here, there’s no such a title as daitennō as far as I am aware, but I digress), as you can see here. I will admit I’ve never encountered this headcanon - you will generally be hard pressed to find Touhou headcanons relying on actual mythology that aren’t just some variety of power level wank or otherwise all around awkward - so I think removing it was the right move (I don’t think the replacement is any better considering Mara is not a “Hindi god” - Hindi is a language, not a religion - but that’s another problem).

I’m also not aware of any Sutoku fan characters save for Tenmu Sutokuin from the fangame Mystical Power Plant who isn’t even supposed to be a take on the canon Tenma. Design-wise she clearly leans more into the vengeful spirit side of things (to the point the design would work better as Michizane than Sutoku, really, though I don’t dislike it). The filename on the wiki misspells her name as Tenma, but I have no clue whether this has anything to do with the strange headcanon assertion from the Tenma article. The closest thing to a Tenma reference she gets is a spell card referencing the sixth heaven, but the game refers to her merely as a “great tengu”.

Kōgyo Tsukioka's illustration of a performance of Matsuyama Tengu, with actors playing Saigyō, Sutoku and another tengu (wikimedia commons)

MPP aside, there's a lot of room for Sutoku in Touhou. The poet-monk Saigyō, whose life and works served as a loose inspiration for the plot of Perfect Cherry Blossom and Yuyuko’s character, went on a journey through locations associated with the late ex-emperor four years after his death, in 1168. He felt a personal connection to him because before being ordained he served as a guard of the imperial palace during his reign. This unconventional pilgrimage to at the time peripheral, sparsely inhabited areas was both a form of paying respect to his former superior, and possibly a way to pacify his vengeful spirit.

Saigyō obviously did not meet the deceased Sutoku, and ultimately only two of his poems deal with his downfall. However, later legends kept expanding upon their connection. This eventually culminated in the development of a tale according to which the monk in fact encountered Sutoku in the form of either a vengeful spirit or a tengu. The noh play Matsuyama Tengu is based on it. Its title is derived from the name Sutoku’s first residence after his exile. As a curiosity it’s worth pointing out the play singles out Sagamibō (相模坊), the tengu of Mt. Shiramine, as an ally of Sutoku - an ideal candidate for a stage 5 sidekick, if you ask me.

Some further interesting developments regarding Sutoku’s tengu identity took place in the Edo period, but I’ll discuss them in a separate section later.

The other tengu emperor: Go-Shirakawa

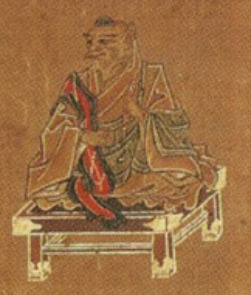

A portrait of Go-Shirakawa (wikimedia commons)

While Sutoku’s opposition to Go-Shirakawa essentially was the first step to the development of the belief he was a tengu, the latter also came to be viewed as a member of this category. While still alive, no less. One of the first sources to identify him as a tengu is a letter of his contemporary Minamoto no Yoritomo. He refers to the emperor as the “greatest tengu of all Japan” because of his notoriously fickle political positions. He at one point approved Minamoto no Yoshitsune’s plan to suppress Yoritomo, just to reverse this decision and declare Yoshitsune is acting on behalf of a tenma.

The notion of Go-Shirakawa being a tengu is present in the Heike Monogatari as well. In the scene I already mentioned, Sumiyoshi informs Go-Shirakawa that extensively studying Buddhist texts made him arrogant, and that he’s already attracting the attention of tengu. It is just a matter of time until he will be reborn as one of them himself. Stressing his religiosity is meant to show how it is possible for him to become a tengu in the same manner as monks.

Go-Shirakawa’s tengu career arguably peaked with his portrayal in Hirasan Kojin Reitaku. It states that both him and Sutoku became tengu, but it is the former whose “power is beyond comparison”. However, he plays no bigger role in the narrative, and he’s not described as a leader of the tengu, or even as the most powerful of them. In the absence of Ryōgen, it is apparently his contemporary Yokei (余慶; 919-991) who became the most powerful tengu. Go-Shirakawa doesn’t even get to be the second most powerful - that’s apparently Zōyo (増誉; 1032–1116). As far as I am aware, no distinct legends about these monks becoming tengu exist, so much like the elevated position of Go-Shirakawa this seems like a peculiarity of Hirasan Kojin Reitaku.

Early twentienth centiury depiction of a typical shirabyōshi costume (wikimedia commons)

While Go-Shirakawa doesn’t appear in any particularly significant pieces of tengu literature otherwise, his personal quirks are responsible for a somewhat obscure aspect of tengu background. A further detail revealed in the Hirasan Kojin Reitaku is that tengu are connoisseurs of all sorts of performances, but enjoy the dances of shirabyōshi in particular. know, I brought this up already in the previous article, but I think it’s a fun detail. Think of the sheer potential of a tengu shirabyōshi character (whether in Touhou context or elsewhere), also.

From celebrated saint to reviled tengu and back again: Ippen

A statue of Ippen from Hōgon-ji, apparently destroyed in a fire in 2013 (wikimedia commons)

Ippen is here more as a curiosity than anything, since he isn’t really a mainstay of tengu literature. Like Ryōgen and the two emperors-turned-tengu, he was a historical figure. He lived from 1238 to 1289 and founded the Jishū school of Pure Land Buddhism. He spent much of his life as a wandering preacher, advocating a unique form of nenbutsu (chanting the name of Amida), the self-explanatory nenbutsu dance (念仏踊り, nenbutsu-odori). Legends assert that various miracles occurred thanks to Ippen’s devotion. For instance, at one point the nenbutsu dance he initiated made flowers fall from the sky. On another occasion, purple clouds appeared above him. Stories of his various miraculous deeds were retold in the form of picture scrolls, such as Ippen Hijiri-e (一遍 聖 絵; “The Illustrated Biography of Ippen”).

Ippen’s activity, in particular the dance he promoted, was evidently controversial among his contemporaries. Tengu Zōshi refers to him as the “chief tengu”, and portrays the practices he spread negatively. An entire explanatory paragraph is devoted to stressing the disruptive character of nenbutsu he promoted. Alongside other unorthodox behaviors it is blamed for various social ills including the fall of the Song dynasty in China (sic).

The opposition of other Buddhist schools to certain early currents within the Pure Land movement was often rooted in the rejection of the worship of deities and even Buddhas other than Amida. Of course, today it’s not hard to find people incorrectly convinced Buddhism is a “religion without gods” (this is a phenomenon so widespread it was actually considered a major obstacle by researchers of the history of Buddhism). However, through the middle ages devas, kami, Onmyōdō calendar deities and various figures like Dakiniten or Matarajin who defy classification altogether were anything but marginal in most schools of Buddhism in Japan. Oaths were sworn by Taishakuten and his entourage, Enmaten and Taizan Fukun were invoked in popular rites meant to guarantee good fortune, and so on. Interestingly, Tengu Zōshi does not deny that miracles attributed to Ippen really happened. In fact, they are even depicted in the illustrations. However, the reader is expected to realize they are implicitly not a genuine display of Buddhist holiness, but merely a tengu trick meant to lead people astray. This is essentially a twist on stories already common in the Heian period, something like the tengu pretending to be a Buddha in a famous story from the Konjaku Monogatari adapted to reflect the anxieties of the Kamakura period tied to new religious movements.

The condemnation of Ippen goes further than merely implying his miracles were trickery, though. While in the final section of the scroll it is revealed that with enough effort even a tengu can attain buddhahood, Ippen is singled out as incapable of that. He is destined to fall even further from grace and to be reborn in the realm of beasts. Despite the circulation of such negative opinions about Ippen among his contemporaries, Jishū school ultimately survived past the Kamakura period, and it still exists today.

Tengu caught between history and fiction: Tarōbō

Tarōbō in a mandala from Mt. Atago (via Patricia Yamada's Bodhisattva as Warrior God; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Tarōbō (太郎坊) is the tengu of Mount Atago. This location’s association with the tengu is well attested, and for instance in Hirasan Kojin Reitaku multiple of them are said to reside there, including Yokei, Zōyo and Jien.

However, Tarōbō is not identical with any of these historical monks. He’s an interesting case because it would appear he stands exactly on the border between historical figures and literary characters. One of the first attestations of him, if not the first one outright, has been identified in the Tengu Zōshi. On an illustration showing a gathering of tengu leaders, who are mostly identified by the names of schools of Buddhism they represent, one is instead given a specific name, Atago Tarōbō (愛石護太郎房). His notoriety continued to grow in later sources: Taiheiki presents him as a well known tengu, while Heike Monogatari outright labels him the “greatest tengu in all of Japan”. While Tengu Zōshi and other early sources don’t provide any information about Tarōbō’s origin, in later tradition he came to be identified with the legendary Korean monk Nichira (日羅). His name would be read as Illa following the Hanja sign values, and at least some authors prefer using this reading or list both. I’m sticking to Nichira here, to maintain consistency with a name sometimes used to refer to his tengu form, Nichirabō (日羅坊; “the monk Nichira”).

A statue of Nichira (amagasaki-daikakuji.com; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Nichira is mentioned for the first time in the Nihon Shoki, in the section dedicated to the reign of emperor Bidatsu (late sixth century). He is described as an inhabitant of Baekje, one of the three Korean kingdoms which existed at the time. However, his father came there from Japan. The emperor seeks his help with navigating foreign policy. After some tribulations - apparently the king of Baekje didn’t want to let him go - he finally arrived in Japan in 583, armed and on horseback. He starts acting as an advisor to the emperor.

After a few months, Nichira is assassinated by other Baekje envoys present in the court since he wants the emperor to pursue rather aggressive foreign policy (most notably, he suggests ruthlessly slaughtering any potential settlers from Baekje who would try to establish settlements in Japan). The assassination has to be delayed, because he emits supernatural light at night. That’s not where his apparent supernatural powers end - after being killed he resurrects for a moment in order to make it clear his assassination was not a plot of Silla (another Korean kingdom). He is later buried, and no further mention is made of him.

While some elements of the Nihon Shoki account were retained in later legends about Nichira, especially his arrival from Korea and his ability to emit a supernatural glow, he was otherwise essentially entirely reinvented. Instead of an advisor of emperor Bidatsu, he came to be portrayed as a Buddhist monk and as an ally of prince Shotoku.

An early example of such a legend is preserved in Nihon Ōjō Gokuraku-ki (日本往生極楽記; “Japanese records of rebirth in a Pure Land”) from the late tenth century. It states that Nichira met with Shotoku when the latter was still a child, and declared he was a manifestation of Kannon. The prince in response recognized him as the reincarnation of one of his disciples from an unspecified past life. We also learn that he is capable of emitting light because of his devotion to Surya, the personification of the sun. There’s no real chronological issue here: while Nihon Shoki doesn’t mention Shotoku (or Buddhism, for that matter; it first comes up a year after Nichira’s death there) in any passages dealing with Nichira, the prince would indeed be a kid at the time of his arrival.

Things get more complicated later on. True to his portrayal as a ruthless enthusiast of military operations, Nichira came to be described as aiding Shotoku in quelling Mononobe no Moriya and his allies. Following the conventional chronology this would have happened long after Nichira’s death, though. A possible attempt at reconciling obviously contradictory traditions can be found in Ōe no Masafusa’s Honchō Shinsenden (本朝神仙伝), as you might remember from the Ten Desires post from last year. In contrast with virtually every other source dealing with Shotoku’s genealogy, Masafusa claims the prince was a son of Bidatsu, which would make him considerably older at the time of Nichira’s arrival. The meeting between them is fairly similar to the Nihon Ōjō Gokuraku-ki version: Nichira recognizes Shotoku as a manifestation of Kannon, and both of them then emit supernatural light. No mention is made of any military help, though. The portrayal of Nichira as a military ally of Shotoku is present in legends which link him with tengu. After the defeat of Moriya, he supposedly left to take over Mt. Atago. According to a guide to famous places (名所記, meishoki) from 1686, Kyōwarabe (京童; “Children in Kyoto”) by Kiun Nakagawa (中川喜雲; 1636-1705) he did so in the form of a tengu.

Atago Gongen (wikimedia commons)

Bernard Faure notes there is a similar legend in which Nichira is a separate figure from Tarōbō. The former, portrayed as a military official in the service of prince Shotoku, sets on a journey to pacify the tengu of Mt. Atago. He accomplishes this by revealing he is a manifestation of Shōgun Jizō (勝軍地蔵), a Kamakura period reinterpretation of this normally peaceful bodhisattva as a fearsome warrior, historically worshiped on Mt. Atago as Atago Gongen. Nichira then becomes the leader of the tengu, while Tarōbō provides him with information about the mountain.

Something that surprised me is that there is a single Korean source which mentions the tradition presenting Nichira as a monk who became a tengu. During the Imjin war, a failed Japanese invasion of Korea, the Korean Neo-Confucian philosopher Kang Hang was captured and subsequently spent three years (from 1597 to 1600) in Japan as a prisoner of war before escaping (possibly with the help of Seika Fujiwara, a fellow Neo-Confucian scholar he befriended). He wrote a memoir dealing with this experience, Kanyangnok (“The record of a shepherd”) in which he mentions Nichira in passing. He states that he was known as Tarōbō, and that he was enshrined and worshiped as Atago Gongen.

Something that’s worth pointing out is that despite living centuries apart, Ōe no Masafusa and Kang Hang both make the same mistake, stating that Illa arrived in Japan from Silla, as opposed to Baekje. I thought this might represent an alternative tradition, but in both cases translators pretty firmly conclude we’re dealing with a mistake. My best bet would be that this has something to do with the Japanese name of Silla, 新羅, sharing a kanji with Nichira’s own name; the name of Baekje, 百済, does not. It doesn’t seem any later legend brings up his post-mortem effort to clear the name of Silla envoys from the Nihon Shoki, so I don’t think that was necessarily a factor.

I’m actually shocked I haven’t seen a Touhou take on Nichira, considering his association with Shotoku. In particular, it’s worth pointing out that his transformation into a tengu is essentially how people tend to mistakenly assume the connection between Matarajin and Hata no Kawakatsu works (in reality, it’s very limited in scope and indirect, but that’s a topic for another time). Plus there’s a lot of storytelling potential in having a tengu - or even Tenma - be yet another character from Miko’s past. ZUN isn’t very interested in building upon prince Shotoku legends involving Kawakatsu or Kurokoma, but it’s hard to deny they’re a popular topic in fanart.

Yet another tradition about the identity of Tarobō, as far as I can tell entirely independent from his connection to Nichira, is preserved in the Engyōbon, the oldest version of Heike Monogatari. A gloss states that he is the tengu form of the monk Shinzei (真済; 800-860), who in a tale from Konjaku Monogatari and a variety of other sources menaced empress Somedono (染殿后; Fujiwara no Akirakeiko), the wife of emperor Seiwa.

Tarōbō also plays a role in a tale unrelated to speculation about his origin, Kuruma-zō Sōshi (車僧草紙; “Tale of the handcart priest”). It was originally composed in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. The eponymous protagonist is a Zen practitioner who, as his name indicates, travels with his handcart in tow. Tarōbō attempts to convince him to abandon this lifestyle. They engage in a Zen dialogue (mondō), in which the monk triumphs over the tengu. He also manages to overcome Tarōbō’s subordinates who attempt to make him stray away from his practice by showing him gruesome images of battles in the realm of the asuras.

Finally, under the name Nichirabō Tarōbō appears in the tale of Zegaibō. Initially I planned to only dedicate a single paragraph to it, but I figured Zegaibō is such a fun figure that a separate section is warranted.

Not a tiangou: Zegaibō, the Chinese tengu

Zegaibō taking a bath (wikimedia commons)

The history of Zegaibō (是害坊) starts before he even got this name. In the anthology Konjaku Monogatari, there are a handful of stories about tengu arriving in Japan from overseas - specifically from India or China. These are obviously literary fiction, as there is nothing quite analogous to tengu in Indian literature, and while their name is borrowed from Chinese tiangou, this term also doesn’t have all that much to do with tengu, ultimately.

One of the aforementioned stories focuses on a Chinese tengu named Chira Yōju (智羅永寿; I was unable to establish whether there’s any connection with 智羅天狐, the alternate name of Iizuna Gongen, Chira Tenko) He arrives in Japan to challenge local Buddhist monks. He reveals that he has previously bested these in his homeland successfully, and that he would like to check how their Japanese peers compare. Local tengu take him to Mt. Hiei, where he unsuccessfully tries to bait major Tendai monks, including Ryōgen, into battling him. He is eventually beaten up by Ryōgen’s attendants, and after his defeat the Japanese tengu take him to a hot spring so that he can recover. In the end he decides to return home. It was possible to establish that Chira Yōju was the basis for the tale of Zegaibō because the colophon of an illustrated scroll known simply as Zegaibō Emaki (是害坊絵巻) states that the story draws inspiration from a similar tale from the lost collection Uji Dainagon Monogatari. Based on other sources it is assumed it was most likely identical with the Konjaku Monogatari account of the misadventures of Chira Yōju. Save for the change of the main character’s name, the stories do not differ much. More time is dedicated to the meeting between Zegaibō and the Japanese tengu, though. They are led by Nichirabō from Mt. Atago.

Zegaibō meeting with his Japanese peers (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Zegaibō evidently became a popular, recognizable character later on. This might reflect a sense of patriotism (or nationalism) the story possibly could have inspired in the readers: the Japanese monks are portrayed as more resistant to the schemes of demons than their continental peers, after all. However, it’s also possible that Zegaibō’s defeat was interpreted as a take on tensions between Buddhist monks and shugenja, considering the latter were commonly compared with tengu. Regardless of which interpretation is correct, Zegaibō’s undeniable popularity allowed him to reappear in a variety of other tales. There is a noh play which simply adapts the tale about him, Zegai. The events are largely the same, though the name Tarōbō is used instead of Nichirabō to refer to the tengu of Mt. Atago. Bernard Faure mentions that in one version of the legend about Nichira’s arrival on Mt. Atago, he defeats Zegaibō, here portrayed as the leader of the local tengu. The tengu subsequently reveals the “sacred geography” of Japan to him. Finally, Zegaibō plays a major role in the Edo period puppet play Shuten Dōji Wakazakari (酒呑童子若壮; “Shuten Dōji in the Prime of Youth”).

In this work, Zegaibō is indirectly responsible for the transformation of the eponymous character into an oni. After a rampage which left 160 monks dead and various other heinous acts, the young Shuten Dōji, known simply as Akudōmaru (悪童丸; “evil child”), proclaims that there has never been anyone more mighty than him in Japan, China or India. This display of arrogance alerts Zegaibō, who appears in the guise of a young monk and offers to wrestle with him so that he can prove his strength. However, as soon as the fight starts, he reveals his true form and takes Shuten Dōji into the air.

Zegaibō presents Akudōmaru to Maheśvara (via Keller Kimbrough's Battling Tengu, Battling Conceit; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Zegaibō then brings his opponent to Maheśvara (摩醯首羅王, Makeishuraō; a phonetic transcription is used in place of the most common Japanese form 大自在天, Daijizaiten). The latter is unexpectedly described as a maō. Zegaibō seemingly presumes that his boss will punish the unruly human by turning him into a tengu, but Maheśvara is so impressed by his bravery that he chooses to turn him into an oni to let him cause even more chaos. This is rather obviously distinct from the more widespread versions I discussed in the not so distant past.

From makara to tengu: Konpira

A typical depiction of Konpira as one of the heavenly generals (via Bernard Faure’s Rage and Ravage; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

While Zegaibō according to tales focused on him arrived from China, there is technically a tengu whose origins were believed to lie even further away - Konpira (金比羅). However, he is a special case because despite being arguably one of the most famous tengu, he actually wasn’t viewed as a member of this category for most of his history.

Konpira is a Japanese transliteration of Sanskrit Kumbhīra. This name can be literally translated as “crocodile”. His origin is poorly understood, though it is possible he was originally essentially a divine representation of reptilian inhabitants of the Ganges. As you can read here, the gharial, the mugger crocodile and the saltwater crocodile all can be found in this river in some capacity.

Fittingly, Kumbhīra is sometimes described as a makara who converted to Buddhism. This term refers to a type of partially crocodilian mythical hybrid, most notably depicted as the steed of Hindu deities such as Ganga and Varuna. Bernard Faure suggests that in Japan he might have been analogously understood as a wani at first. However, Kumbhīra could also be portrayed as a yaksha, for example in the Golden Light Sutra. What remained consistent is the idea that he was a fierce being converted to Buddhism.

Kumbhīra is well known as the foremost of the Twelve Heavenly Generals (十二神将, jūni shinshō). It is possible that the crocodilian Kumbhīra and the homonymous heavenly general were initially separate deities, though in Japanese context they are effectively the same. Konpira and his peers are regarded as the protectors of the Buddha Yakushi but historically were simultaneously perceived as a type of shikigami. I will only discuss this role more in my next article, though, as it is not very relevant here. All you need to know is that it made him a commonly invoked protective deity in apotropaic rituals.

An interesting legend pertaining to this aspect of Konpira’s character is preserved in the Taiheiki. When Fujiwara no Yasutada (藤原保忠; 890-936) fell ill, a Buddhist priest arrived to perform a ritual focused on Yakushi and his heavenly generals to heal him. However, as soon as he started to invoke Konpira, Yasutada got so horrified that he died. The ritual has apparently been hijacked through supernatural means, and what he heard was not the name “Konpira” but rather the phrase kubi kiran - “I’ll cut off your head”. This was an act of vengeance of the spirit of Sugawara no Michizane - Yasutada was one of the courtiers who conspired to exile him earlier. Evidently after he became a vengeful spirit he was able to essentially turn Konpira to his cause and reverse the effects of invoking him.