#blaeu atlas

Text

Blaeu Atlas of Scotland - Maps - National Library of Scotland

The first Atlas of Scotland, containing 49 engraved maps and 154 pages of descriptive text, translated from Latin into English for the first time.

From its source the Clyde struggles north past the house of Baron Somerville, in the Barony of Somerville [after his death it was sold about 1636 to Lord Robert Dalzell from the Gentlemen of the King’s Bedchamber, who now enjoys the title of Earl of Carnwath],and from the west takes in the Duglas or Douglas Water, named from its blackish and greenish water; it shares its name both with the valley through which it flows, called Douglasdale, and with Douglas Castle in it, which in like manner has imparted it to the family of Douglases. This family, which is certainly very old, achieved its greatest fame after James Douglas was always present, as his closest friend, with unique bravery of spirit and prudence in the most difficult times, with King Robert Bruce as he claimed the kingdom, and the same Robert entrusted his heart to him, to fulfil the vow to convey it to Jerusalem.

0 notes

Text

Two suns with different personalities from volume one of our Blaeu Atlas. One leonine as it sits in the center of a diagram of Copernicus' model, the other pensive as it rises over Tycho Brahe's observatory.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

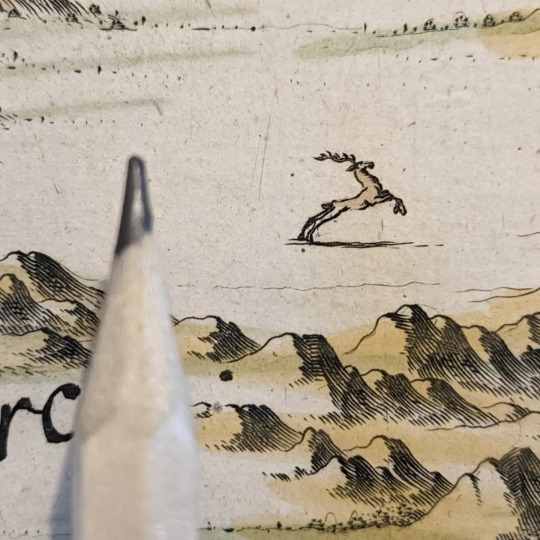

Tiny prancing reindeer, from the map of Norway in volume one of Joan Blaeu's eleven-volume Atlas Major, 1662

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Framed Old World Map Cartography By Willem Blaeu Theatrum Orbis Terrarum framed:Professional solid Wood Ornate Moulding Dry mounted, will never fold or fade Molding:Professional Mahogany Finish with Gold Trim (solid-wood) Print: Full Color dry mounted glossy print Glass is included, Comes Fully Assembled Ready For Your Wall This is a fantastic glass framed print of a uniquely colorful old world map. This map was originally published by the famed cartographer William Blaeu (1571-1638)."Upon the death of the publisher of Gerhard Mercator's maps, Willem Blaeu seized his opportunity to release the most ambitious atlas of his day, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, also known simply as Atlas Novus, or the New Atlas. This six-volume set contained the most up-to-date maps of the entire world.".(USC Library dept.).Measurements are 16"X12",40cm x 30cm including its all wood high quaility finished frame.This classic map adds beauty and class to any room office or study. At this price this is a spectacular deal. THIS IS A DECORATIVE REPRODUCTION OF AN ANTIQUE MAP NOT AN ANTIQUE IN ITSELF.BUY WITH CONFIDENCE. ALL OF MY DELICATE ITEMS ARE SHIPPED WITH A SPECIAL 3 LAYER PROTECTION SYSTEM.

#custom framed print#old world map#cartography#classic map#map decor#georgraphy#library decor#vintage decor#antique maps

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

Martino Martini – Scientist of the Day

Martino Martini, an Italian Jesuit, was born Sep. 20, 1614.

read more...

#Martino Martini#Jesuit science#China#cartography#Blaeu atlas#histsci#17th century#history of science#Ashworth#Scientist of the Day

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[Joan Blaeu. Atlas Maior]. America.

Quae est Geographiae Blavinae Pars Quinta, Liber Unus, Volumen Undecimum. [Amsterdam]: Labore & Sumptibus Ioannis Blaeu, [1662]. First edition. Large folio in twos

#Joan Blaeu#Atlas Maior#America#virginia#map vintage#illustration#Quae est Geographiae Blavinae#Volumen Undecimum#1662#1st edition

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Joan Blaeu, Dobunos [The Rollright Stones]. from Nuevo Atlas del Reyno de Inglaterra. Gravure, between 1645 and 1662.

#joan blaeu#historical atlas#atlas#england#rollright stones#megalithic stone circle#megalithic monuments#stone circle#folklore#landscape#landscape art

0 notes

Photo

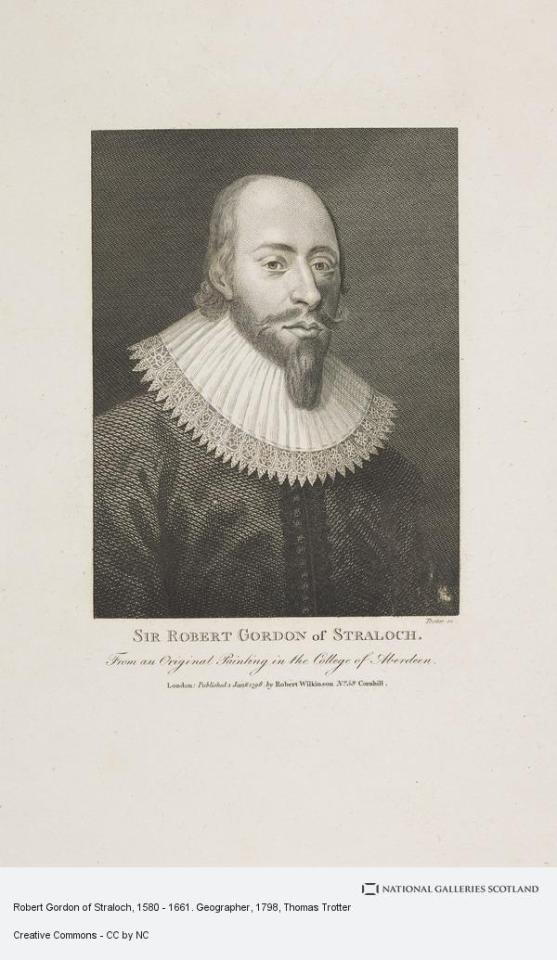

Robert Gordon of Straloch was born at Kinnundy in Aberdeenshire, on the 14th September, 1580 and is said to have been the first graduate of Marischal College.

Gordon is often named as “ The man who literally put Scotland on the map “

Robert Gordon of Starloch is one of those clever Scots that are described as Poly maths, at one time or another he was a mathematician, poet, superb musician, composer, essayist, geographer, historian and antiquarian, and above all, a cartographer who devised what is still one of the most beautiful and popular books of maps of Scotland, the Theatrum Scotiae.It is due his skills I am honouring him a rather lengthy biography.

Robert was the younger son of Sir John Gordon of Pitlurg near Ellon in Aberdeenshire, a knight who was loyal to James VI, who asked him to provide a no-doubt expensive horse for his royal wedding. Gordon was certainly well-connected – Robert’s mother was Isabel Forbes, daughter of the 7th Lord Forbes.

Gordon’s private education meant he learned Latin in childhood – was followed by his matriculation as one of the first, if not the very first, students of Marischal College, forerunner of Aberdeen University. He completed his studies at the University of Paris before returning to Scotland in 1600 on the death of his father.

As landed gentry he was able to devote his time to continuing his studies and taught himself geography, which would come in handy in his future career, while he began to write and gather music to play on his beloved lute.

In 1608, he married Catherine, daughter of Alexander Irvine of Lenturk, and they had a large family – nine sons and six daughters in all. Soon after his marriage he bought the estate of Straloch in Aberdeenshire, and in 1619 he became a very wealthy man when his elder brother John died childless, leaving the Pitlurg estate to Robert.

Now he was able to indulge his love of history and especially geography, then a rudimentary science. In fact, he practically invented proper map-making in Scotland, based on extensive topographical measurements that he largely made himself.

At the time of Gordon’s birth it was believed that there were just three maps of Scotland in the whole kingdom, and their inaccuracy was well-known. James VI encouraged the map-making of Timothy Pont, a graduate of St Andrews University who has a good claim to be Scotland’s first serious cartographer as he made dozens of maps of various parts of Scotland in the 1590s before he became a minister of the Kirk in Caithness where he died in 1614.

The geographer Sir James Balfour would later ensure that Pont’s maps were published, but by the 1620s, Robert Gordon was beginning to produce much more accurate maps with his scientific methods.

He also found time to compose poetry and music pieces, leading to the publication of his musical masterwork, “Ane playing booke for the Lute, wherein are contained many currents and other musical things, Musica mentis medicina moestae”, which was printed in Aberdeen in 1627.

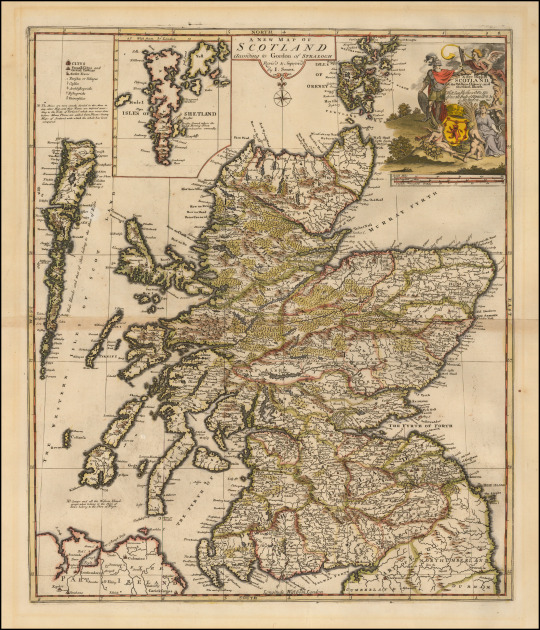

In 1641, King Charles I was asked to pay for an atlas of Scotland by the famous map publishers Blaeus of Amsterdam. Gordon was by then the best and best-known map-maker in Scotland.

Charles wrote to him: “Having lately seen certain charts of divers shires of this our ancient kingdom, sent here from Amsterdam, to be corrected and helpit in the defects thereof, and being informed of your sufficiency in that art, and of your love both to learning and to the credit of your nation; we have therefore thought fit hereby, earnestly to entreat you to take so much pains as to revise the said charts, and to help them in such things as you find deficient there until, that they may be sent back by the direction of our chancellor to Holland.”

Flattery will get you everywhere, especially royal flattery, and Gordon duly embarked on his life’s greatest work, the Theatrum Scotiae. It wasn’t just the 46 beautiful and accurate maps that made Theatrum a magnificent publication, but also the many notes on the history and antiquities that accompanied the maps – scholars would rely on them for ages afterwards.

Charles I was so concerned about the work being finished that he arranged for the Scottish Parliament to give Gordon exemption from taxes, while his family were granted freedom from military duties – a major concession in those troubled times. From the outset it was seen as a work of national importance – all Church of Scotland ministers were asked to assist Gordon with local details.

Finished in 1648, Theatrum Scotiae was an immediate sensation and would have two further editions.

Gordon also wrote histories in Latin and exchanged views with the leading scholars of the day on everything from the life of John Knox to the history of the Gordon family. It was in the family vault at New Machar that he was buried in August 1661.

Though a neglected figure now, in his lifetime Robert Gordon was recognised as a great scholar and was famous enough to have his portrait painted by George Jamesone. His grandson, also Robert Gordon, became a wealthy philanthropist and it is he whose name is borne by Aberdeen’s “other” university.

The second pic is “A New Mapp of Scotland According to Gordon of Straloch”

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

1130 AD: Slaughter at Stracathro

(Detail of Angus from Robert Edward’s map of 1678- Stracathro can be seen north of Brechin on the banks of the Esk. Clicking on the image should make it larger. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland)

In the year 1130, an army led by Angus, ruler of Moray, was defeated by forces loyal to David I, King of Scots, at the Battle of Stracathro. Although this engagement was recorded by a wide variety of medieval chroniclers and historians, few provide any details about the course of the battle or its background. Even the exact date is unclear. Nonetheless, Stracathro is often seen as a pivotal moment in the relationship between the powerful lords of Moray and the developing kingdom of Scotland, and an important flashpoint in the domestic politics of David I’s reign.

To make sense of the various surviving accounts of this battle, it is necessary to give some background information on Angus of Moray’s status. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, ‘Moray’ covered a much larger area than it does now. A territory which stretched from the north-east to Ross, its rulers often found themselves in competition with the neighbouring jarls of Orkney and the kings of Alba, the latter of whom were then expanding their territory to include Strathclyde and Lothian south of the Forth, forging what we would now recognise as the kingdom of Scotland. However it is unclear whether Moray’s lords were independent rulers or regional lieutenants of the kings of Alba. The current academic consensus seems to be in favour of the latter, with some historians calling the rulers of Moray ‘mormaers’ (literally ‘great steward’ but often seen as equivalent to ‘earl’). Nevertheless Moray’s medieval inhabitants may well have seen things differently. At any rate, the rulers of Moray were clearly powerful figures in the north, with a close (if often fraught) relationship with the rulers of what we now call Scotland.

This closeness increased in 1040 when Moray’s ruler, Mac Bethad Mac Findlaích (Shakespeare’s ‘Macbeth’) seized the throne of Alba. Mac Bethad had claimed Moray after his cousin Gillecomgain burned to death in 1032. He had also swiftly married Gillecomgain’s widow Gruoch* who was a granddaughter of Kenneth III, king of Alba. Some years later, Mac Bethad defeated the then king of Alba, Duncan I, in battle near Elgin, and claimed the throne of Alba. He ruled for seventeen years before his own death at Lumphanan in 1057, following his defeat by forces loyal to Duncan’s son Malcolm III. Mac Bethad was briefly succeeded by his stepson Lulach ‘fatuus’ (‘the simple’), son of Gillecomgain and Gruoch, before Lulach too was killed in 1058 and Malcolm III succeeded in wresting control of Scotland...

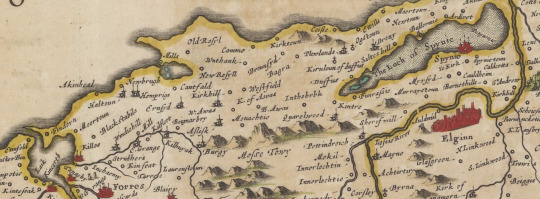

(The Laich of Moray in the Blaeu Atlas of 1654. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland)

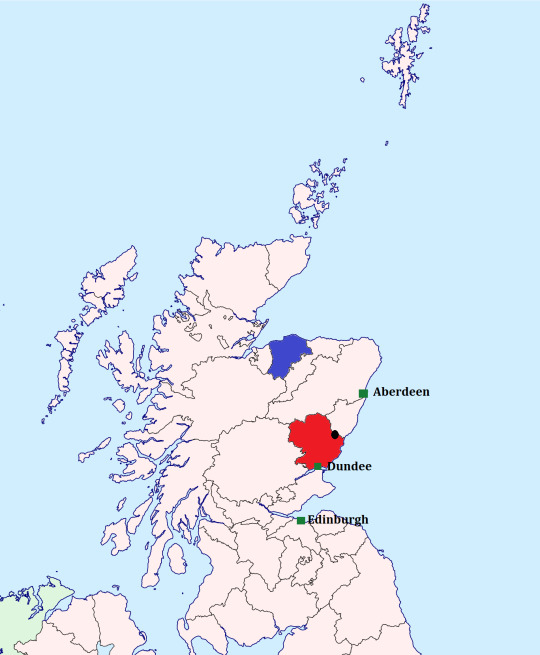

(The shire of Moray is highlighted in blue and Angus (Forfarshire) in red. The old county system was only beginning to emerge in David I’s reign, and Moray in particular referred to a much larger province than shown here. The black spot shows the general location of Stracathro- I am no cartographer however, so this is only a rough guide. Template Source).

No more kings of Alba would be drawn from the house of Moray after Lulach’s death. A short conflict between Malcolm III and Lulach’s son Máel Snechta did break out in 1078: Máel Snechta got the worst of it but may have reached an agreement with Malcolm, since his kinsmen continued to rule in Moray for some decades. After this no serious challenges came from Moray for over fifty years until 1130, when another descendant of Lulach- his daughter’s son Angus- was ruler of the province.

Although we know something of his maternal ancestry (his father is a complete mystery), Angus of Moray is still a rather obscure figure. Late mediaeval Irish annals call him ‘rí’ or ‘king’ of Moray. Conversely, contemporary Anglo-Norman sources, as well as the Chronicles of Melrose and Holyrood, and late mediaeval Scottish historians like John of Fordun, all use the Latin word ‘comes’, which implies that they saw Angus’ position as roughly equivalent to that of a count or earl. Some bias is to be expected from Anglo-Norman sources since they usually favoured the descendants of Malcolm III and St Margaret over other branches of the royal house. Nonetheless we lack convincing evidence that the early twelfth century rulers of Moray controlled an independent kingdom, though they might perhaps have been ‘subkings’. We do know that Angus had a reasonably good claim to rule over both Moray and Alba, and the men of Moray were clearly willing to support him in this. And yet there had been no recorded conflict for over fifty years, so why did Angus choose to make his move in 1130?

Perhaps the answer can be found in the internal politics of the Scottish royal house. By 1130, David I, the youngest son of Malcolm III by his second wife Margaret of Wessex, had worn the title ‘King of Scots’ for six years. Although history remembers David as an impressive and innovative monarch- one of those kings who ‘made’ Scotland- in the early years of his reign his power seems to have been centred on the southern provinces of Lothian and Strathclyde. His control of ‘Scotia’ or Alba- the traditional heartland of the kingdom north of the River Forth- was less certain, and he must have seemed a very distant figure in a place like Moray. He also had to contend with rivals for the throne, like Malcolm, the son of David’s older brother and predecessor Alexander I. Described by the contemporary Anglo-Norman chronicler Orderic Vitalis as illegitimate, in an age when this did not yet disqualify a man from kingship, Ailred of Rievaulx later called Malcolm, ‘the heir of his father’s hatred and persecution’.* He may have opposed his uncle David at the outset of the reign, though if so he was plainly unsuccessful. This was not to be the last of Malcom’s intrigues however, since he pops up again a few years later in the company of Angus of Moray, taking part in the invasion of Alba in 1130. Perhaps then Malcolm’s appearance in Moray meant that he was able to convince Angus to support his claim and that this provided the impetus for the invasion. However it must be said that, in general, Angus is presented as the real leader of the campaign. Most sources do not even seem to think Malcolm’s presence at Stracathro worth mentioning, while Orderic Vitalis wrote that Angus ‘entered Scotland with the intention of reducing the whole kingdom to subjection’, and merely notes that Malcolm accompanied the army.

(David I and his grandson Malcolm IV, in a twelfth century charter belonging to Kelso Abbey. Source- Wikimedia commons)

(The round tower at Brechin, a few miles south of Stracathro, was likely constructed in the twelfth century, if not earlier. It is one of only two such round towers in Scotland)

It is also worth bearing in mind that, at the time of the invasion of Alba, David I was probably hundreds of miles away in the south of England, attending the court of his brother-in-law King Henry I. Although David’s relationship with the English king had proven useful on many occasions, this time it might have provided Angus and his allies with the perfect opportunity to revolt. Perhaps his absence also provided motive: later twelfth century kings of Scots would occasionally face armed opposition to their prolonged absences from the realm, and it is possible that Angus sought to capitalise on any discontent. Whatever the ultimate cause of their revolt, the year 1130 saw Angus and Malcolm march south with an invasion force which is said to have been 5,000 strong.

Contemporary sources do not tell us much about the course of the campaign. Only the late fourteenth century historian John of Fordun, who hailed from the Mearns himself and probably drew on earlier sources, gives a location for the sole recorded battle- Stracathro, near Brechin in Angus. This suggests that Angus of Moray’s army either headed south by one of the tracks over the Grampian mountains or, perhaps more likely, travelled east in the direction of Aberdeen and from there made its way down the low-lying strip of land between the Mounth and the coast. This last route would have covered roughly similar terrain to the modern A90 road and, although the landscape of long rolling fields sloping away towards the blue foothills of the Mounth in the west may have looked very different in the twelfth century, its strategic value for a mediaeval army on the move is readily apparent. The Romans had already marched across this ground a thousand years earlier, leaving the remains of a camp at Stracathro, and the conquering forces of Edward I of England would later follow a similar route north in 1296. It is also clear that, despite the sparse details given in contemporary sources, and despite David I’s posthumous legacy as a strong monarch, the 1130 invasion represented a serious crisis. In the absence of any recorded opposition, Angus and his supporters had been able to overrun the fertile east coast of ‘Scotia’, not far from the Tayside heartlands of the kingdom, and only forty miles or so from the traditional coronation site at Scone.

The men of Moray were only brought to a halt when King David’s constable Edward, son of Siward, hastily assembled an army and cut Angus’ force off a few miles north of Brechin. Orderic Vitalis, the contemporary writer who describes the battle in the greatest detail, tells us little about Edward other than that he was ‘a cousin of King David’ and the son of Siward who, according to various translations, was an ‘earl’ or ‘tribune’ of Mercia. Since his name and paternity indicate that he was of English stock, it is possible that Edward was one of the king’s maternal cousins, but theories abound as to his exact identity. Previously, several historians accepted the theory that he was the son of Siward Beorn (the earl of Northumbria who fought against Macbeth) and thus an uncle of David I’s queen Matilda. However this does not really tally with the few details Orderic provides, and any son of Siward Beorn would likely have been in his seventies in 1130. More recent writers, including David I’s most recent academic biographer, favour Ann Williams’ identification of Edward as a son of Siward, son of Aethelgar, a Shropshire thegn and therefore both of Mercian descent and, like David, a great-great grandson of Aethelred the Unready.

(View of Stracathro and the surrounding country in James Dorret’s map of 1750. I have coloured the kirk of Stracathro in red so it can be spotted more easily; again clicking on the image should expand it. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland)

The royal army clashed with Angus and his men at Stracathro. No source gives a blow-by-blow account of the battle but the result was clear. In a rout which the Irish Annals of Innisfallen described as the ‘Slaughter of the men of Moray in Scotland’**, Angus and most of his force were killed. We should be wary of mediaeval chroniclers’ tendency to play fast and loose with numbers, but the language which all sources use about the engagement indicates that the death toll was high, with the late mediaeval Annals of Ulster even claiming that as many as 4,000 of the men of Moray were killed- 80% of the force which Orderic Vitalis claimed Angus was able to put into the field. The Annals of Ulster also claimed that a thousand of the men of Scotland (or ‘alban’) died, but this number was later corrected to one hundred. Leaving the chroniclers’ suspiciously exact death tolls aside, it is clear that the battle of Stracathro was a catastrophe for the Moravians, and a blood-bath from which Angus’ co-commander Malcolm, the son of Alexander, was very lucky to escape. Fleeing soldiers from Angus’ shattered army were then chased back to Moray by the triumphant Edward and the Scots, who promptly established control over the province.

Both mediaeval chroniclers and more recent historians have traditionally made this annexation of Moray following the battle seem very easy. As Robert de Torigni neatly summed it up, ‘Angus, the earl of Moray, was killed; and David, the king of Scotland, held the earldom thenceforward’. Now the undisputed overlord of Moray, David I is then supposed to have set about a comprehensive programme of ‘feudalisation’, complete with reformed monastic orders, a reorganised diocesan system, royal burghs for controlling trade, and, of course, a new settler nobility. However, David’s most recent academic biographer, Richard Oram, has argued that this feudalisation of Moray may have been a slower process than is often implied, and that it took some time for David and his supporters to establish complete control over the old lordship. Indeed, although there was to be no more trouble from Moray until the reign of David’s grandson King William, the fact that rivals for the Scottish throne were still able to draw considerable support from the native nobility of the province in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries could indicate that the post-Stracathro reorganisation was not so complete as some writers have assumed.

Stracathro is now a quiet place. A century and a half after the battle the area witnessed another, less bloody, defeat when John Balliol and his council negotiated with the triumphant Edward I of England from the kirkyard of Stracathro in July 1296. But other than this Stracathro is probably best known for its community hospital and a Victorian walled garden. The Battle of Stracathro is not exactly the most famous event in the annals of Scottish history. In a county that is otherwise littered with carved stones which allegedly commemorate ancient battles, few traces of the twelfth-century skirmish remain. Two mounds near Ballownie farm used to be pointed out as the alleged burial site of the slain, and certain internet etymologies claim that the nearby place name ‘Auchenreoch’ can be interpreted as deriving from a term meaning ‘the field of great sorrow’***. But otherwise the battle of 1130 has not left much of a mark in the landscape. Modern perceptions of the battle are also influenced to a great extent by the accounts of Anglo-Norman chroniclers, who may well have downplayed the threat which Angus of Moray (and other twelfth century rivals for the throne) posed to the descendants of Malcolm III and St Margaret. Nonetheless the slaughter at Stracathro is worth commemorating: had the battle gone the other way, Scotland might have been a very different place today.

(Stracathro Mansion is not necessarily on the site of the battle, and the landscape has changed considerably in nine hundred years, even down to the way fields are ploughed. However this may at least give an idea of the surroundings of the north part of Angus, with the Mounth in the background. Reproduced under the Creative Commons License (source here) since I’m limited in the photos I can take personally right now for obvious reasons).

Notes:

* Everybody’s favourite ‘Lady Macbeth’

**Not to be confused with Malcolm MacHeth

*** The original Irish says ‘Albain’

**** Though it must be said, I have my doubts

Selected Bibliography:

“The Ecclesiastical History of England and Normandy”, by Orderic Vitalis, Vol. III, translated by Thomas Forester

“Early Sources of Scottish History”, ed. A.O. Anderson

“Rerum Hibernicarum Scriptores”, vol. 2, ed. Charles O’Conor

“Annala Uladh”, vol. II, edited and translated by B. Mac Carthy

“Chronicle of Melrose”, and the “Chronicle of Holyrood” trans. Rev. Joseph Stevenson in ‘The Church Historians of England’, vol. IV

“Scottish Annals From English Chroniclers”, ed. A.O. Anderson

“John of Fordun’s Chronicle of the Scottish Nation”, ed. W.F. Skene and trans. Felix Skene

“Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000-1306″, G.W.S. Barrow

“The Kingship of the Scots”, A.A.M. Duncan

“Domination and Lordship: Scotland, 1070-1230″, Richard Oram

“David I”, Richard Oram

“’Soldiers Most Unfortunate’: Gaelic and Scoto-Norse Opponents of the Canmore Dynasty, c.1100-c.1230”, R. Andrew MacDonald

“Companions of the Atheling”, G.W.S. Barrow in ‘Anglo-Norman Studies 25: Proceedings of the Battle Conference 2002′

#Scottish history#Scotland#British history#battles#medieval history#twelfth century#historical events#1130s#David I#Angus of Moray#Mediaeval#Middle Ages#High Middle Ages#warfare#Malcolm son of Alexander I#Moray#mormaer of Moray#Macbeth#Lulach (d. 1058)#Mael Snechta of Moray#Malcolm III#Malcolm Canmore#House of Canmore#Angus#Stracathro#Battle of Stracathro#Forfarshire#north-east

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We happened across the Great Britain volume of our sumptuous hand-colored Blaeu atlas, an 11-volume set from the mid-17th century. It’s always a treat to see these vibrant colors (which cost the original buyers 20% more, and was well worth it)...

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blaeu - Atlas of Scotland 1654 - INSULAE ALBION ET HIBERNIA - Old Great Britain

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dit is de Canon van Nederland. Ik vind dat andere mensen in het verleden het meer verdienen om erbij te zitten, jullie niet?

Geschiedenis

Canon van Nederland PO

Muhammed Ozkan Havo 4

Leeractiviteit 2-1

Trijntje = blank

Willibrord = blank

Karel de Grote = blank

Erasmus = blank

Maria van Bourgondië = blank

Jeroen Bosch = blank

Willem van Oranje = blank

Johan van Oldenbarnevelt = blank

Michiel de Ruyter = blank

Rembrandt = blank

Hugo de Grote = blank

Christiaan Huygens = blank

Sara Burgerhart = blank

Koning Willem 1 = blank

Napoleon Bonaparte = blank

Max Havelaar = blank

Vincent van Gogh = blank

Aletta Jacobs = blank

Anne Frank = blank

Anton de Kom = gekleurd

Marga Klompé = blank

Annie M.G. Schmidt = blank

Leeractiviteit 2-2

Hebban olla vogala (±1075)

De Hanze (1356-1450)

De Opstand (1566-1581)

VOC en WIC (1602-1799)

De Beemster (1612)

De Atlas Maior van Blaeu (1662)

De Statenbijbel (1637)

Eise Eisinga (1744-1828)

De Grondwet (1848)

De eerste spoorlijn (1839)

Het Kinderwetje van Van Houten (1863-1901)

De watersnood ( 1 februari 1953)

Indonesië (1945-1949)

De Tweede Wereldoorlog ( 1940-1945)

De televisie (vanaf 1948)

Haven van Rotterdam (vanaf ±1880)

De gastarbeiders (vanaf 1960)

Het Oranjegevoel (vanaf 1974)

Europa (vanaf 1945)

Het Caribisch gebied (vanaf 1945)

Kolen en gas (1974-2022?)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atlas Maior will stay put

Atlas Maior will stay put #cartography #history Read more here:

The 11-part big atlas Atlas Maior made in 1663 by Joan Blaeu was sold for 600.000 euro to the Phoebus Foundation, funded by Fernand Huts, the owner of an international logistics service provider and port operator.

The atlas is 3.000 pages long, contains 594 charts and is UNESCO World Heritage. It will be displayed in the Mercatorhuis, a museum featuring multiple atlases.

It is currently unknown…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Photo

MWW Artwork of the Day (5/24/18)

Jan van der Heyden (Dutch, 1637-1712)

Still-Life with Rarities (1712)

Oil on canvas, 74 x 63,5 cm.

Szépmûvészeti Múzeum, Budapest

Most of van der Heyden's paintings were done in the sixties and seventies -- his work as inventor, entrepreneur, and city official probably slacked his pace. But he continued to paint until the very end. His latest firmly datable picture, "Still-life with Rarities," now in Budapest, shows the corner of a 'Kunstkamer' in strong even light with meticulous depictions of rarities from the natural and man-made world, but not the collector who assembled them. It is proudly inscribed with his monogram and states he painted it when he was seventy-five years old; he attained that age in 1712, the year he died.

Among the objects displayed in the Kunstkamer, which is most probably a fictive one, are a hanging armour of an armadillo, a copy after an etching of Pietro Testa's Suicide of Dido above the marble mantle, an inlaid cabinet used for housing treasured coins and natural specimens, oriental weapons, and on the bright red Chinese embroidered cloth that covers the table globes, one terrestrial and the other celestial, and an open Blaeu atlas. Next to the table there is a red damask covered chair that supports a folio Bible open at the favourite passage of Dutch moralists: Ecclesiastes, Chapter I, which begins with 'The words of the Preacher ... vanity of vanities; all is vanity. What profit hath a man of all his labor which he taketh under the sun?' The biblical reference to transience is reinforced by Testa's Suicide of Dido, a subject taken from Virgil's Aeneid which can be read as an exemplum of love's ephemeral nature.

Van der Heyden's message is obvious and familiar. It is one we have heard from other still-life specialists: preparation for salvation is of greater importance than all the treasures, pleasures, and knowledge that can be derived from this world.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

(*EPUB)-> Blaeu: Atlas Maior - BY Joan Blaeu in PDF, EPub online.

Blaeu: Atlas Maior

by Joan Blaeu

Click Here Download =>Download Or Read Here

Descriptions :

Synopsis : World class: The finest atlas ever publishedSuperlatives tend to fail in face of Joan Blaeu s Atlas Maior, one of the most extravagant feats in the history of mapmaking. The original Latin edition, completed in 1665, was the largest and most expensive book to be published during the 17th century. Its 594 maps across 11 volumes spanned Arctica, Asia, Europe, and America. Its scale and ambition occupies such an important place in Dutch history that it is included in the Canon of Dutch History, an official survey of 50 individuals, creations, or events that chart the historical development of the Netherlands.TASCHEN s meticulous reprint brings this luxurious Baroque wonder into the hands of modern readers. In an age of digitized cartography and global connectivity, it celebrates the steadfast beauty of quality print and restores the wonder of an exploratory age, in which Blaeu s native Amsterdam was a center of international trade and discovery.True to TASCHEN s optimum reproduction

Details : Author : Joan Blaeu Pages : 512 pages Publisher : Taschen Language : ISBN-10 : 3836538032 ISBN-13 : 9783836538039Reading Download Pdf Epub

0 notes