#bohain en vermandois

Text

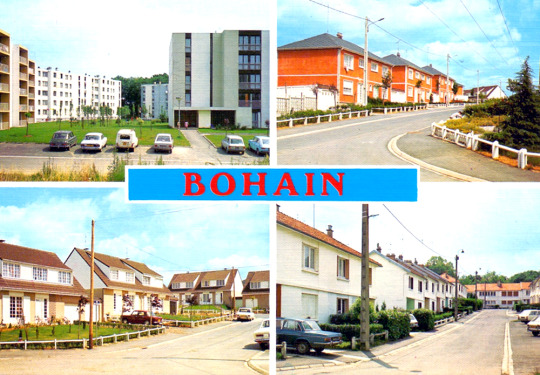

Bohain en Vermandois.

les nouveaux quartiers.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

HENRI ÉMILE BENOÎT MATISSE

On this day of 31st December, Henri Émile Benoît Matisse (31 December 1869 – 3 November 1954) was born in Le Cateau-Cambrésis, in the Nord department in Northern France.

He was an artist, known for both his use of colour and his fluid and original draughtsman-ship. He was a draughtsman, printmaker, and sculptor, but is known primarily as a painter. Matisse, along with Pablo Picasso, was one of the artists who best helped to define the revolutionary developments in the visual arts.

The intense colorism of the works he painted brought him notoriety as one of the Fauves (wild beasts). Many of his finest works were created was a rigorous style that emphasized flattened forms and decorative patterns.

He relocated to a suburb of Nice on the French Riviera, and the more relaxed style of his work gained him critical acclaim as an upholder of the classical tradition in French painting.

When ill health in his final years prevented him from painting, he created an important body of work in the medium of cut paper collage.

He grew up in Bohain-en-Vermandois, Picardie, France, and went to Paris to study law. He first started to paint after his mother brought him art supplies during a period of convalescence. He discovered "a kind of paradise", and decided to become an artist, deeply disappointing his father.

In Paris he studied art at the Académie Julian and became a student of William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Gustave Moreau. Matisse was influenced by the works of earlier masters such as Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Nicolas Poussin, Antoine Watteau, Édouard Manet, and by Japanese art.

Matisse visited the Australian painter John Russell. Russell introduced him to Impressionism and to the work of Vincent van Gogh—and gave him a Van Gogh drawing. Matisse's style changed completely; abandoning his earth-coloured palette for bright colours. Matisse exhibited in the salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, two of which were purchased by the state.

Matisse died of a heart attack at the age of 84.

#henri Émile benoît matisse#famous painters#master painters#famous artists#art history#anniversary of artists#fauves#impressionism

1 note

·

View note

Photo

LA MÈRE MASSÉ DANS SON INTÉRIEUR À BOHAIN Voici un tableau peint par Matisse en 1903 : "La devideuse picarde" Regardez "Camille Saint-Saëns : Tarentelle en la mineur op. 6 (Mosnier/Génisson/Dumont)" https://youtu.be/9PKJ6759fik Matisse a passé son enfance à Bohain-en-Vermandois, petit village de l’Aisne. Ses parents vendent des graines, des engrais mais aussi, dans un rayon droguerie, des couleurs et pigments. Il y vit au milieu de l’animation des foires, des couleurs des textiles produits par les tisserands locaux et la beauté de la campagne environnante. " Lorsque sa famille s'installa rue du Château, Bohain était déjà à mi-chemin de sa transformation d'un village de tisserands endormi au fin fond de l'ancienne forêt d'Arrouaise en un centre de fabrication moderne avec dix mille métiers à tisser", écrit Hilary Spurling dans le premier volume de sa vie d'Henri Matisse. #culturejaiflash https://www.instagram.com/p/CckULPDMpTb/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

How the Master Became the Master

Matisse: Radical Invention, 1913–1917 is the kind of show the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) does best: take a specific period of an artist’s career and demonstrate the development and breadth of that aesthetic vision. Co-curated with the Art Institute of Chicago, it is a big show about a brief time in the great artist’s long life. It is both a revolutionary and revelationary approach that is breathtaking in its concentration on five important and yet often overlooked years in the artist’s career.

Matisse: Radical Invention, 1913–1917 is the art exhibition to see in New York – and more than once. Before anyone quibbles about yet another Matisse show, consider that MoMA and Chicago have taken out of storage and from many public and private collections rarely seen works to play off one another in this mammoth undertaking. Although it contains over 100 works, the display is never oppressive. It never feels padded. One eagerly races from one gallery to the next to take it all in. This art all seems still so vigorous and fresh, as radical as ever. The selection reflects the full range of the artist’s vast invention through paintings, sculptures, prints and drawings. Nothing could be more thrilling and satisfying. Matisse: Radical Invention, 1913–1917 defines what a blockbuster should be.

This title, of course, is not only misleading but nonsense. A large number of the works belong to years other than the designated five. They commence with the aggressive Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra) of 1907 and continue as late as 1931 when the artist completed the fourth and final “Back” relief. What does “Radical Invention” mean as far as Matisse’s career is concerned? Would not that apply to every phase of it? Naturally MoMA and Chicago rely on their own rich holdings, but the exhibit would have been enhanced in places with pertinent examples from the Hermitage in St. Petersburg and the Barnes Foundation on Philadelphia’s Main Line. The Russian Sergei Shchukin was the great early collector of Matisse, but the dreadful economy may have prohibited any loans. Perhaps it was pointless to try to borrow anything once owned by the idiosyncratic Alfred C. Barnes. Though the masterpieces Dance I (1909) and The Red Studio (1911) too are conspicuously absent, both can be found on another floor of MoMA in the permanent collection.

If Picasso had his Blue and Pink Periods, then 1913 to 1917 might be called Matisse’s Gray Period. The understated palette he now employed drew on subtle shades of gray, blue and rose, some brown and green, all held together by thick black. Some paintings look almost monochromatic or like hand-coloured photographs. There is nothing naturalistic about the hues he chooses. As in the work of Cézanne and many of Matisse’s Cubist contemporaries, the underlying drawing was of greater importance to his paintings than any brilliant colour effects, even though the use of light continued to play a significant part in these pictures. Matisse found radical new ways of applying paint to canvas. He layered, slathered, splashed, slashed, smeared and scratched it. The raw textures invigorate the subdued colours. Matisse, like the revered Cézanne before him, audaciously allowed the bare white of the canvas to show through as another colour.

The numerous paintings of bathers in the MoMA show perhaps too conveniently refer back to Cézanne's Three Bathers (1879–1882) that Matisse owned and then look forward to Matisse’s monumental Bathers by the River (1917) from Chicago, the kingpin that closes the exhibit. La Luxe II (1907–1908) looks less like late stolid Cézanne than limp vintage Vallotin; and the coy expression of horror (or is it wonder?) on the central figure in Bathers with a Turtle (1908) wrecks this absurd picture. Yet Bather (1908), a young nude male from the back, is one of the most powerful pictures Matisse ever painted. It is the only one of these swimming paintings comparable in quality to Bathers by a River, one of the master’s masterpieces. Bather embodied everything that Matisse was attempting as an artist at the time.

The African influence is still evident in many of these pictures, particularly the portraits. Like the pencil drawing of Shchukin and the famous Portrait of Madame Matisse (1913) in the Hermitage, Portrait of Sarah Stein (1916) wears a mask instead of a face. So too do The Italian Woman (1916) and Portrait of Auguste Pellerin (II) (1917). The latter sitter rejected an earlier version of the picture, but Matisse was not really interested in capturing exact likenesses. The Italian Woman fades in and out of the background in a composition that fuses Cubist conventions with Matisse’s own concepts of construction. The artist was more concerned with the colours and patterns in The Manila Shawl (1911) than in the woman who wore it. The rather smug Nude with a White Scarf (1909) is just as blunt as any of Picasso’s African-inspired pictures of Parisian prostitutes.

The show really does take off as it progresses from 1913 when the painter returned to Paris from Morocco until his departure for Nice in 1917. Picasso as always was Matisse’s bête noir. Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) forced everyone to entirely rethink art. (Ironically, Matisse was the one who introduced the Spaniard to African art.) Fellow Fauves like Georges Braque and André Derain deserted Matisse for Cubism. No matter how much he might have wanted to, Matisse could not ignore Picasso. Theirs was a heated rivalry that greatly fuelled Modern Art as each artist tried to outdo the other. Not surprisingly, Matisse once compared their relationship to a prizefight. “No one has ever looked at Matisse's paintings more carefully than I,” Picasso confessed and then added with some irony, “and no one has looked at mine more carefully than he”. The show at MoMA proves that Matisse was as revolutionary as Picasso.

Be warned that the Matisse of the current show is not the popular painter of the postcards and posters, the beloved old sensualist obsessed with colour, line and the female form. This is the thinking man’s Matisse, struggling with the precepts of the Cubist Revolution to develop what he called “methods of modern construction”. Most importantly, he shifted from concerns of colour to questions of form as he developed his own distinctive visual shorthand for figure and landscape. Despite his familiarity with Picasso’s efforts, Matisse did not follow anyone. The French poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire shrewdly observed at the time, “Matisse’s art is eminently reasonable”. Yet the artist himself insisted that he relied only on his instincts.

Working almost solely within his studio, Matisse seemed disengaged from the world outside him. Many of the paintings of this period deal with windows and the play of sunlight streaming through them. Despite the inconveniences the war inflicted on the artist, these pictures and sculptures are entirely divorced from the mayhem then raging around him. Like Bonnard, Matisse was a master of bourgeois domesticity. He sought “an art of balance, of purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter” that should be “a calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue”. He tried to enlist in the French army but was turned down because he was 44 years old. He continued to busy himself throughout the war with portraits, nudes, interiors, exteriors and still lives just as he had during peacetime. There are no soldiers in uniform, no battle scenes, no reference to or residue of the devastation just beyond his studio. Matisse preferred to draw the precise contours of a piece of fruit on a plate to depicting the violence then destroying the rest of the country. Viewing Matisse’s work done during those turbulent times is as if the First World War never happened. Although he did produce a series of prints to aid the prisoners in Bohain-en-Vermandois in 1914 and 1915, Matisse was not a political artist. Pleasure and the pursuit of happiness alone defined his art.

Not wishing to draw attention to himself with the rest of the world at war, Matisse chose not to exhibit these works as they were being produced. Consequently, critics and scholars have largely neglected this crucial period in his life, until MoMA’s exhibition. Other painters must have been familiar with individual pictures. Portrait of Auguste Pellerin (II) with its predominant black lines suggests Max Beckman’s German Expressionist paintings and Composition (1915) finds echoes in the American Milton Avery’s later art while Branch of Lilacs (1914) and The Rose Marble Table (1916) must have inspired the Russian David Shterenberg.

Particularly fascinating is Matisse’s 1915 deconstruction of his own 1893 student copy of Still Life After Jan Davidsz. de Heem’s “La Desserte” decades before Picasso re-imagined works by Velasquez, Cranach and other Old Masters. Matisse had come across the old picture while going through things he had moved to Issy-les-Moulineaux after the French army requisitioned his home in Paris. Here was a typical painting of the Dutch school relying on heavy chiaroscuro that Matisse discarded when he brightened it up “by adding everything I’ve seen since”. The new work looks like a collage of little still lives done in a variety of manners and yet they all fit together to form a surprisingly integrated composition. It is like a Mini-Master Class in Modernism.

No matter how commonplace may be his subjects, there is nothing conventional about their rendering. The simple but monumental Apples (1916) and A Vase with Oranges (1916) purify the genre and nearly outdo the grandiose Dutch Masters. The Blue Window (1913) looks back to The Red Studio by displaying some objects, including one of the artist’s sculptures, against a single colour that dominates the room and the rhythmic landscape beyond the pane. The sunlight cuts up Goldfish and Palette (1914–1915) into odd angles. A wide band of black shadow behind the fishbowl gives it and the goldfish a haunting luminosity. Matisse had originally painted himself into the picture on the right; only his thumb in the palette remains. Matisse, much as Cézanne did on his trips to Provence, redefines the very nature of the landscape itself in the colliding slashes of colour in Shaft of Sunlight, the Woods of Trivaux (1917) and the flat geometric shapes of Garden at Issy (1917).

Matisse never entirely embraced pure painting, but he came damn close to it during this highly exploratory period. Although never completed, French Window at Collioure (1914) summarises all Matisse was thinking at the time. No more than a view through window into the darkness, it is arguably the most abstract of his works. It is almost a Colour Field painting as a large swatch of black is squeezed between the wide blue-gray stripe of the opened window on the left and the other gray half of it and the green wall on the right. Equally extraordinary is View of Notre Dame (1914), a brash, concise architectural rendering of the famed landmark against a blotchy blue ground. Many people once believed the painter had left it unfinished. Its stark simplicity is not what one expects of Matisse, yet the skeleton of the cathedral is powerful as such. Though few others have realised it, Matisse always insisted that he provided a specific subject in Composition (1915). It is another view from his window with the floral curtain evident on the left. However, the landscape outside has been reduced flat areas of pure colour, a swirl of bright yellow against light blue and green.

The little known and rarely seen prints of this period are the real revelation of this show. The graceful pencil-thin etchings seem to be fighting to break free of the confines of the edge of the plates. The modest monotypes of white lines against velvety black ground sore in their simplicity and clarity. Matisse full realised these often-overlooked still lives in as few strokes as possible.

Matisse took risks. Consequently, not all of his experiments were successful. One obvious dud is Head, White and Rose (1914) that is no more than a lame parody of Cubism. It does not even look like a Matisse. The Portrait of Yvonne Landesberg (1914) too is less than stellar, being more Larionov than Matisse. The rays seem arbitrarily imposed upon the sitter rather than radiating from her, as do the black lines that define the figure of Portrait of Olga Merson (1911). Matisse scraped them apparently with the end of his brush after completing the rest of the Landesberg picture.

The juxtaposition of all these different kinds of art in a single exhibition is often brilliantly done. Nothing seems to clash. It is a pleasure to compare the zaftig Blue Nude with two small 1907 sculptures of another reclining nude nearby; and the bronze heads of Jeanette are conveniently placed beside each other for easy study. Oddly the four muscular bronze Back (1907–1931) reliefs are displayed chronologically, rather than lined up back to back like soldiers as in their usual place in MoMA’s garden. Having to run back and forth in this exhibition to trace their artistic development greatly diminishes their impact.

Modernism often teeters on caricature and Matisse’s work is no exception. Mme. Derain could not have been flattered much by the 1914 etching nor Jeanne Vaderin by his series of brawny bronzes. The rough, rugged, raw Blue Nude seems a parody of the smooth sleek boudoir paintings of the period. Aggressively un-erotic, it still shocks. Not surprisingly Picasso did not care for it. “If he wants to make a woman, let him make a woman,” the Cubist complained when he encountered it in Gertrude Stein’s apartment. “If he wants to make a design, let him make a design.”

These works are often difficult, sometimes frustrating and always fascinating. They beg the viewer to take risks too. One of the most Cubistic of the paintings in form and hue, Woman on a High Stool (Germaine Raynal)” (1914), is a stunning picture and surprisingly reminiscent of Giacometti. The black line gives mass to the figure and the limited colour pushes it forward off the flat canvas. Another major painting in the show, The Moroccans (1915–1916), reduces the Near Eastern scene to its stark geometry against the black background. The clump of green Cubist bushes turns out to be men kneeling in prayer.

Everything comes together in The Music Lesson (1916). The painter’s little boy plays the piano amidst his father’s art while the sunlight through the picture window plays tricks on the living room and upon his young face. A small sculpture from 1908 nestles in the lower left corner with Woman on a High Stool on the wall to the right, suggesting the music teacher as she listens to the child’s fingers exercises behind him or reflected in a mirror. Matisse does not merely copy that earlier painting: he re-conceives it as a distinctive new picture.

If any of this art fails to awe the viewer, it is the drawings. They seem more the means to the end rather than concise, distinctive works done entirely on their own terms. The charcoal and pencil studies of women are more about erasing than drawing. Some sketches from Morocco are no more than doodles lacking the master’s touch. As another artist said in a different context, it is like looking at Matisse in his underwear. Not a pretty sight.

Matisse often reworked his canvases, radically transforming them into almost entirely different works of art. This was particularly true of Bathers by a River. The artist himself called it one of the five most important pictures of his entire career. It is hard to argue with him. It went through a long gestation of six distinct states all carefully documented in the exhibition, a digital survey and the catalogue. The Art Institute of Chicago recently bombarded the picture with a series of scientific investigations to determine exactly its aesthetic evolution. Begun in 1909 originally as a mural for Shchukin’s stairway in his Moscow home, Matisse returned to the picture again and again and ended up with one of the great works of the 20th century. Although likely not his initial intent, the sculpted nudes, now pared down to their simplest forms, could be different views of the same model on four separate panels. Each is rendered slightly differently from every other one. The artist likewise rethought Back in four distinct forms between 1908 and 1931, producing among the most influential sculptures of the modern era. Unlike his pictures that he painted over, Matisse wisely preserved each state of this sculpture.

Now the bad news. The curators have been so caught up in the latest technology that they seem to have lost sight of the art in their exhibition. They are so busy studying the trees that they do not quite see the forest. They have taken X-rays of the pictures and digitally reconstructed the various stages of their development and eagerly put their research on the walls. Doggedly applying modern science to these works drains them of their magic, their mystery, their poetry. “Hast thou not dragged Diana from her car?” wondered Edgar Allan Poe in his Sonnet To Science. The oversized supplemental panels mounted between the pictures are crammed with lots of text and many tiny snapshots. Some discuss paintings missing from the show. Such gratuitous minutiae are more appropriate for an academic dissertation than an art exhibition. All this scholarly stuff encourages unnecessary congestion as patrons plant their feet before the paintings to diligently listen to the banality of the commentary on their headphones as they strain to study the panels. Some may even glance from time to time at the art. There is so much to read and so many little reproductions to look at that it all distracts from the major thrust of the organisers’ fine argument. Better, in fact, to buy the weighty catalogue and study the scholarship at leisure.

~

Michael Patrick Hearn · 23 Sep 2010.

#matisse#art article#exibition review#review#studio international#painting#fauvism#Bathers by a River#the moroccans#the piano lesson#ww1

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Paris la douce : Maison Familiale d’Henri Matisse - Bohain-en-Vermandois

0 notes

Photo

à Bohain-en-Vermandois https://www.instagram.com/p/B7TBGqDIN78/?igshid=va27rhho4aol

0 notes

Photo

- Matisse foreva + eva✨✨✨ #TherapiMusings (at Bohain-en-Vermandois) https://www.instagram.com/p/B6q8GNFFXZI/?igshid=8viehppu6cbx

0 notes

Text

Aisne: Le jeune Steven est rentré chez lui

Aisne: Le jeune Steven est rentré chez lui

Steven, 17 ans, avait disparu dans la nuit de jeudi à vendredi.

Aux environs de minuit et demi, Steven avait fugué du domicile de ses parents situé à Bohain-en-Vermandois, dans l’Aisne.

Dans la journée de samedi , il a été retrouvé et à regagné son domicile.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Henri Matisse with his mother, Anna in 1889. - Matisse’s father, Émile Hippolyte Matisse, was a grain merchant whose family were weavers. His mother, Anna Heloise Gerard, was a daughter of a long line of well-to-do tanners. Warmhearted, outgoing, capable and energetic, she was small and sturdily built with the fashionable figure of the period: full breasts and hips, narrow waist, neat ankles and elegant small feet. She had fair skin, broad cheekbones and a wide smile. "My mother had a face with generous features," said her son Henri, who always spoke of her with particular tenderness of the sensitivity. Throughout the forty years of her marriage, she provided unwavering, rocklike support to her husband and her sons. Matisse later said: "My mother loved everything I did." He grew up in nearby Bohain-en-Vermandois, an industrial textile center, until the age of ten, when his father sent him to St. Quentin for lycée. Anna Heloise worked hard. She ran the section of her husband's shop that sold housepaints, making up the customers' orders and advising on color schemes. The colors evidently left a lasting impression on Henri. The artist himself later said he got his color sense from his mother, who was herself an accomplished painter on porcelain, a fashionable art form at the time. Henri was the couple’s first son.

#Henri Matisse#photo#art#artist#Anna Heloise Gerard#the young Matisse#the young Henri Matisse#Matisse and his mother#Henri Matisse and his mother#Matisse#photography#family#mother and son

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Responsable QHSE F/H

Job title: Responsable QHSE F/H

Company: Nexans

Job description: que Responsable QHSE pour notre usine de Bohain. Au sein du site de Bohain-en-Vermandois, spécialisé dans les câbles de caoutchouc… souple, nous sommes à la recherche de notre futur/e Responsable QHSE. Membre du Comité de Direction, vous avez…

Expected salary:

Location: France

Job date: Thu, 10 Jun 2021 23:47:18 GMT

Apply for the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Video

youtube

♪ Découvrez la chorale des collège et lycée Saint-Antoine et Sainte-Sophie de Bohain-en-Vermandois, académie d’Amiens ! ♪

Un chœur confiné mais qui reste en lien en interprétant La Montagne de Jean Ferrat. Quelques choristes et instrumentistes de la chorale, de l'orchestre, de l'option musique et de la spécialité musique de l'ensemble Saint-Antoine-Sainte-Sophie (Bohain) ont pris part au projet avec joie et bonne humeur. Filmés chez eux, ils ont été accompagnés et soutenus par leur professeur (Audrey Saniez) qui a réalisé le montage.

0 notes

Text

🅗🅔🅝🅡🅘 🅜🅐🅣🅘🅢🅢🅔

31. December 1869 - 3. November 1954

Henri Matisse was described as the precursor to Abstract Expressionism and modern art with his fauvist style. Many use his most basic techniques to recreate and inspire their own art, such as painting, cutting up the painting and reassembling (an example of the paper cut-out design). His art has been known to sell for millions of dollars in the US, and is bought internationally to this day.

Matisse grew up in Bohain-en-Vermandois. In 1889 he contracted appendicitis and spent several months recovering, this is where, at 20 years old, he found the isolation and freedom of painting.

Matisse left for Paris in 1891 to study art. Matisse failed the entrance exams for the Ecole des Beaux Arts, and instead joined the studio of Gustave Moreasu in 1892. The symbolist style of Moreasu contributed to Mattise’s expressive palette. In 1895 he was accepted into the Ecole des Beaux Arts and continued to study with Moreasu until 1898.

Despite financial difficulty, Mattise collected avant-garde artwork. Inspired by the post-impressionist style, Matisse moved forward from his impressionist exploration. In 1905, he spent a summer in Collioure, creating a new, bright style with Derain, this later became known as Fauvism. Mattise was known as the Fauvist leader by the press. Matisse sought to construct form through colour.

By 1907, Matisse had begun to use simple form on simple colour, now forming a new interest in sculpture, now moving forward from Fauvism. He became inspired by the work he’d seen on his 1906 trip to Algeria, he then sculpted resolved prictorial problems. In 1908, Matisse opened an art school.

Gradually Matisse shifted his focus onto the human figure, surrounded by Eastern decor. The effects of the enviroment around him during the war had affected him, thusly muting his palette, however he did return to bright colours towards the end of the war, using the white of the canvas more. However by 1930, he grew unhappy with the direction his art was taking, so he begun to try illustration, tapestry design and glass engraving. Matisse was commissioned to create a mural in 1931 (completed in 1933).

When confined to a wheelchair in 1941, Matisse used drawing and paper cut-outs as they were easier for him to use, and gave a new opportunity for expressionism, these paper cut-outs were similar to his previous brushwork techniques. Additionally these cut-outs would simplifiy the form more so, using some symbolism in his work. These paper cut-outs were used as a base technique to design the stained glass windows of the Chapelle du Rosaire. Matisse continued to work, despite ill health, until he died of cancer in 1954.

SOURCE

#matisse#henri matisse#art#artist research#a level art#fine art#fineart#a levels#a level#research#post impressionism#artist#studyblr#study blog#studyspo#study#artwork#btec#blog#art blog#henrimatisse

0 notes

Video

Snippet from the upcoming video. "Instinct must be thwarted just as one prunes the branches of a tree so that it will grow better."- Henri Matisse (at Bohain-en-Vermandois)

0 notes

Photo

JEUX ENFANTINS "LES ABEILLES" Henri Matisse, 1948-1955 Vitrail, 300x760 cm Ecole maternelle Henri Matisse, Le Cateau-Cambrésis. MUSIQUE Maya l'abeille https://youtu.be/muuzICyikRc En 1948, Matisse conçoit en gouaches découpées la maquette du Fleuve de vie, une de ses premières recherches pour la Chapelle du Rosaire, qui deviendra en 1955 le vitrail Les abeilles de l’école maternelle Matisse du Cateau-Cambrésis. Henri Matisse est né un 31 décembre, dans la maison de ses grands-parents maternels, bourgeois qui pratiquaient la tannerie. Après une dizaine de jours, ses parents retournent à Bohain-en-Vermandois (à 15 km au sud de Le Cateau-Cambrésis) où ils tenaient un commerce de grains. C’est là qu’il passe son enfance. La carrière de peintre de Henri Matisse, qui l’a fait voyager et séjourner à Paris et à Nice, a été longue et bien remplie, marquée par un perpétuel renouvellement de créativité. Au soir de sa vie, les liens avec sa ville natale vont se renouer grâce à l’action du Cambrésien Ernest Gaillard, architecte et conservateur de musée. Ce dernier souhaite créer un musée à Le Cateau-Cambrésis et rencontre l’agrément de Henri Matisse. Parallèlement, Ernest Gaillard assure la construction d’une école maternelle qui sera baptisée du nom de Henri Matisse. Pour cette école, à l’agencement de laquelle il s’intéresse, Matisse reprend le vitrail « Fleuve de vie » créé initialement pour la chapelle de Vence, qui sera appelé « Les Abeilles », et réalisé par Paul Bony en 1954-1955. L’inauguration a lieu après le décès du peintre. Ce vitrail a valeur de symbole : " J’ai fait le rêve de donner de la joie aux hommes. J’ai voulu créer au Cateau une féerie de couleurs qui serait comme un esprit de la lumière. #culturejaiflash #artmodernedunbonheurcontagieux https://www.instagram.com/p/CNMxn8vnjvh/?igshid=3pz7ny4qdobv

0 notes

Text

Travel in the Footsteps of Henri Matisse in Morocco

Until the advent of mass tourism, North Africa’s jewel, Morocco remained a relatively unknown world of Sultans, spices and sparse deserts. A number of artists throughout the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries visited this faraway land. Through their artworks, the public could learn about this unknown country. One of those was Henri Matisse.

Matisse’s Journey into Art

Henri Matisse (1869-1954) was one of the 20th century’s most influential artists. Born in Bohain-en-Vermandois in northern France, he didn’t start painting until he was 20. After a year of legal studies in Paris, he returned to northern France to become a clerk in a legal office. During this time he attended a morning drawing class at a local art school. Then, in 1891, after recovering from a severe case of appendicitis, he left his job in law. He went back to Paris and began his journey to becoming a professional artist.

His career spanned an impressive six decades and he became synonymous with his expressive use of color and Fauvist style. Throughout his career, Matisse’s paintings most commonly depicted figures in landscapes, portraits, interior settings and nudes.

Henri Matisse in Morocco

When we think of Matisse, Morocco is not a country that automatically comes to mind. Heavily influenced by the countries of the Mediterranean, much of his artwork is tinged with the color and the essence of these places. However, reaching a point in his career when he needed a little inspiration, he decided to visit Morocco in both 1912 and 1913.

The artist set out to discover this remote country and its people. Like many artists of this time, he went in search of North African culture, in search of the Orient, and the exotic. Matisse was drawn to this land by the images of lions, deserts, Sultans, jewels and spices. Above all, the main objectives of his travel to this faraway land were to find a new artistic direction and discover its culture.

The Grand Hotel Villa de France

Our journey to Morocco begins at the Grand Hotel Villa de France, where Matisse stayed during both his trips to Tangier. Landing in this port city in 1912, Matisse was at first disheartened. Writing to his friend, the poet Gertrude Stein, he complained that for five days “it had rained incessantly”. As a result, he was confined to his room. It was here that he first began painting in 1912.

With little else to inspire him, he started painting the objects and views he saw around him. Firstly, he turned to the flowers in his room, as can be seen in the painting Vase of Irises. Exploring the realms of light and color, this painting presents the flowers neatly placed on a marble top dressing table. Yet, it is his famous painting of the beautiful view across Tangier from the hotel room’s window that defined Henri Matisse in Morocco. Landscape Viewed From a Window, looking out over St Andrew’s Church to the kasbah beyond, is a classic example of Matisse’s bold use of colors to encapsulate landscapes. Nowadays, the hotel allows visitors into this room to look out upon the scene that Matisse saw all those years ago.

Enthralled with the view from the hotel, he painted another view in The Bay of Tangier. Painted from a different angle, he shows the blue and green tiled roofs of the city, as well as the sweeping bay and looming rain clouds.

The Medina and Surroundings

Our next stop, following Henri Matisse in Morocco, leads us to the kasbah in Tangier and its surroundings. It wasn’t long before the skies cleared and the hot North African sun shone down. As such, the artist was finally free to walk around and discover the city’s charms. However, not straying far from the hotel, he painted the majority of his work in Tangier’s kasbah, fortress, medina, and medieval walled city. Naturally, like anyone arriving in Morocco, he was eager to see Tangier’s kasbah, the maze-like market of the city.

Firstly, in Entrance to the Kasbah, he presents sharp contrasts between light and shadow, so characteristic of Morocco. A typical Moroccan scene, the painting illustrates the keyhole-like entrance to the market, with a local man at work on the left. The fierce blue of the sky clashes with the vibrant red of the floor to capture the vivid color contrasts.

Next, he leads us to the tomb of Sidi Boukoudja in Le Marabout. Located on the edge of the kasbah, this building is a typical representation of the type of architecture found in Tangier, and Morocco. The building, built in 1865, is used as a shrine to honor the life of Sidi Ahmed Boukoudja, a family member of the city’s then patron. Although Matisse typically painted unusual, abstract portraits, his paintings from Morocco were much more realistic.

A Short Coffee Stop

Meandering around the zigzagging little paths of any medina may prove to be quite tiring. Perhaps a short stop off at a local cafe would be just the break one needs. This was the case with Matisse, who stopped at a charming little cafe next to the kasbah. Inspired by the bustling little cafe and its people, he captured the scene in Moroccan Café. This time using much lighter colors, he paints the cafe goers in their traditional grey jellabah and white turbans. Something that would have seemed very exotic to the Frenchmen at this time.

Mesmerized by its whitewashed houses, centuries old palaces and blend of North African culture, it is clear that Matisse was greatly inspired by Morocco. In 1915, long after his travels were over, he honoured his time in Tangier with the cubist painting The Moroccans. Above all, he captures the cafe culture of the city describing the artwork as “the terrace of the little cafe of the kasbah”. He depicts three distinct sections; a mosque behind a balcony with a flower pot, a vegetable patch and a man wearing a turban. The block of black color unites the three parts together, presenting an interesting perspective from the cafe where he sat.

Moving Forward

For anyone planning a trip to the mesmerizing city of Tangier, let these paintings be a starting point. Follow in the footsteps of Henri Matisse in Morocco, and discover this awe-inspiring and vibrant land through his art.

~

Charlotte Stace · June 26, 2020.

0 notes

Photo

à Bohain-en-Vermandois https://www.instagram.com/mylenekokel/p/Bw43I7BFmYg9Hg5eVSN87qma6VdzZe3nB7CbYk0/?igshid=8gec78uz52dt

0 notes