#but this series goes in so many different directions and underlying themes and references and has so much straight up text?

Note

okay for a guy who entirely missed out on emh when it happened. Is there still a way to actually experience it as a complete thing still. seeing as so much of it was hosted on so many different platforms and idk how many of them still exist to be looked at im INTIMIDATED... but i miss slenderman i want to see it. how useful are the nightmind videos on it... help

the nightmind videos are basically the best way to start the series because he compiles all the blog posts and tweets explaining what happened in between each early video, and the highlights of the early livestreams. AND he explains the trials and the packages that got sent out. That includes the highlighted parts of the books in the packages and what that meant for the series. Basically analysis that the fans were doing at the time it was coming out. THAT BEING SAID! There's some videos that he just briefly summarizes or brushes over, and theyre still fun to watch even if theyre less relevant to the overall story.

So tbh i recommend watching the Nightminds, and watching the subsequent videos as he's covering them. I would say from... this video onward ish (its a little bit into part 4 of the explanation videos. watch that for yourself)

The twists and scares are better experienced that way without nightmind over your shoulder explaining whats up. and if youre confused, just go back to the explanation vids! (especially before jim thorpe. there's a lot of shenanigans to explain there) Also once u watch the later vids, you can skip around the explained parts 5-7 bc NM puts a lot of just the full videos in so it goes by faster

ALSO! this playlist is the most complete one ive seen, it has not just the series itself, but the videos of the fans opening the habit packages, the crossover episodes with the other SV series, and the really long discovered audio tapes from the end of the series (which i was there for the discovery of, super cool! :D)

EDIT EDIT EDIT! someone linked me a playlist thats even MORE comprehensive!!

here it is

#everymanhybrid#emh#have fun!!! it's definitely got like a million more layers than marble hornets which i feel u can watch wo the explanations#but this series goes in so many different directions and underlying themes and references and has so much straight up text?#so the nightmind commentary is damn near needed just to understand all this weird subtext happening#but sorry. you do have to sit and listen to nightmind explain the different tshirt colors. its a right of emh passage. sorry#experiencing like. jim thorpe and consensus and moving in as is without the nightmind commentary is more fun#bc those are just some good horror without all the explanations#and i dont wanna say watch NM up until MOVING IN bc i reaaaalllyyy like the stuff leading up to it. dont just skip to habit.#thats like the jojo part skipping and the homestuck act skipping lmfaoo#speakeasies#also in my silly billy opinion u dont need the entire everyman play analysis to watch the videos from :D onward

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vash the Stampede as a Contemporary Outlaw Figure

(This is a paper I wrote nearly 20 years ago. It is also a first draft, and were I to rewrite it, I would make major structural changes. It was written for a Robin Hood literature class, and the assignment was to analyze a contemporary outlaw figure in a work of fiction using the framework developed in the course. I received an A on the paper, and the professor loved it because most folks just did it on Robin Hood.)

The twenty-six episode Japanese anime series Trigun was originally published as an eight-volume Japanese manga (graphic novel or comic book) by Yasuhiro Nightow in 1997. In 1998, the manga was turned into an animated series, which was directed by Satoshi Nishimura. Trigun’s genre is rather interesting, as the setting is a desert planet called Gunsmoke, so the series itself is a mix between science fiction and westerns. Interestingly, the year 1998 is sometimes referred to by Japanese anime fans as “the year of the ‘space cowboy’ animes” because of two other anime outlaw series that were produced in the same year: Outlaw Star and Cowboy Bebop (Raye).

The main character of Trigun is Vash the Stampede, also known as the Humanoid Typhoon, a man questing for love and peace. Vash is tall with spiky blonde hair and bright blue eyes. He is distinctively marked by a mole on his cheek and an earring, and he always wears a red trenchcoat. As the title of the series implies, he wields three guns: one “regular revolver, the hidden gun in his artificial left arm, and… the Angel Arm” (Adam). Vash has a bounty of sixty million double-dollars on his head because he destroyed the town of July with the Angel Arm. The setting of Trigun creates problems for this outlaw, as Gunsmoke is technically uninhabitable. The cities on Gunsmoke have to use technology to protect themselves from the harsh elements, so when Vash destroyed July it was a death sentence for the surviving residents. In fact, there should be no humans on the planet at all, but a colony fleet crash-landed on the planet centuries before. It is later revealed that Vash is not human and was born on the vessels. His twin brother and the major villain of Trigun, Knives, decided that humanity was evil and had to be kept from spreading to the rest of the universe and caused the near-fatal crash. Knives is also able to manipulate Vash’s Angel Arm[1] and was the true cause of the destruction of July. At the end of Trigun, Vash and Knives battle one another. Vash wins, but refuses to kill Knives.

Vash has three companions: Meryl Strife, Millie Thompson, and Nicholas D. Wolfwood. The major villains are members of the Gung-Ho Guns, a misfit gang of technologically or genetically enhanced humans who serve Knives in his quest to rid Gunsmoke of all humans. The Gung-Ho Guns follow Vash wherever he goes and cause trouble that is generally blamed on him. The main members of the gang, who Vash fights at various points in the series, include: Legato Bluesummers, Monev the Gale, Dominique the Cyclops, E.G. Mine, Rai-Dei the Blade, Leonof the Puppetmaster, Grey the Ninelives, Hopperd the Gantlet, Zazie the Beast, Chapel the Evergreen, Caine the Longshot, and Midvalley the Hornfreak. Various other villains not associated with the Gung-Ho Guns, appear in the anime as well.

Vash the Stampede is a contemporary outlaw figure. The series itself follows very closely with traditional outlaw themes, though much of the underlying philosophy and mysticism is decidedly Eastern. Trigun can be easily viewed as an outlaw tale using the tracking outline. In addition, it is important to look briefly at the birth of the Japanese outlaw figure.

Trigun exhibits many qualities common in outlaw tales, though with a different and sometimes unabashedly silly flavor. Instead of a reigning monarch, Gunsmoke is ruled by the Bernardelli Insurance Company, which initially outlaws Vash and places the bounty on his head for the destruction of July. Of course, the desire to gain that bounty causes mayhem wherever Vash goes, and things simply get worse. Gunsmoke is run by the whims of the insurance company, coupled with the whims of town mayors and sheriffs, who are often corrupt. There are several examples of this. In episode four, the owner of the town water supply, Mr. Cliff, turns out to be blocking it for economic gain, which has forced the town residents to flee or die of dehydration. In episode four, the town patron, Grim Reaper Bostock, and the town sheriff, Stan, are revealed to have murdered innocent people to gain their positions. In episode ten, an unnamed town mayor takes a woman and child hostage in an attempt to force Wolfwood to kill Vash so the mayor can acquire the sixty million double-dollar bounty. In each instance, Vash tricks the villains and delivers justice, setting things right again, though often leaving quite a bit of damage in his wake.

Vash “recruits” followers quite inadvertently. Meryl and Millie, two employees of the Bernardelli Insurance Company, meet Vash in episode one, but do not believe that he is really Vash the Stampede because, as Meryl says quite blatantly, Vash acts like a bumbling idiot. However, they keep running into each other because the two insurance agents are chasing Vash sightings. During their initial meeting, Vash rescues them from two bounty hunters who end up destroying a town in an attempt to capture or kill him. As the story unfolds, Meryl and Millie slowly realize that he really is Vash the Stampede. Through their observation of Vash, they come to understand, to a certain degree, that the destruction that follows him is not his fault. In fact, several times they help him restore justice in the towns of Gunsmoke. Despite their reports of this to the Bernardelli Insurance Company, Vash is labeled a human natural disaster and the insurance company stops paying for damages caused by him. Meryl and Millie become outlaws, of sorts, by continuing to follow Vash against company orders. Similarly, in episode nine, Vash saves Wolfwood from dehydration in the desert. In the same episode they work together to save a child. Though Wolfwood doesn’t join the three immediately, they run into him several more times. When Vash and Wolfwood are forced to fight each other in episode ten, it becomes obvious early in that they are evenly matched. Following the battle, Wolfwood becomes a permanent fixture in the series as a traveling companion.

The code that Vash exhibits is also very similar to that of the traditional outlaw. One of his oft-repeated lines is “This world is made of love and peace!” and he travels Gunsmoke questing for those two ideals. In addition, Vash tries to help those in need and believes in protecting the helpless and innocent, especially women and children. However, his biggest code of conduct is his refusal to kill. Vash tries to get his travel companions to follow this particular code of conduct over all others, especially Wolfwood, who has no qualms about killing those who attack him. Wolfwood obeys until near the end of the series, when he kills a child: Zazie the Beast, who controls sandworms and is trying to kill not only Vash and the others, but also several dozen orphaned children. Vash is outraged by this because he was convinced that Zazie was simply misguided and could be helped, and a rift forms between him and Wolfwood, which never heals because Wolfwood is killed. Similarly, Vash is forced to kill Legato Bluesummers, a telepath who can take control of humans’ actions, which drives him to a mental breakdown.

Vash’s determination not to kill is very complicated in its origin and consequences. Vash promised a woman named Rem Saverem that he would never kill. Rem is the outlaw’s love interest, though she is much different from the Maid Marian figure: Rem is dead. Ironically, Knives is the person who killed her when he tried to destroy the fleet of colony ships. Rather than escaping death with Vash and Knives, Rem went back and altered the course of the other ships enough to prevent them from burning up in Gunsmoke’s atmosphere, giving the humans aboard a chance to survive. Rem is a powerful figure in Trigun, and almost acts as a patron saint, appearing in dreams that sometimes warn Vash of danger and in flashbacks that show that she is the basis for the system of moral values that Vash follows. Rem’s appearance is generally accompanied by the Greenwood vision of red geranium blossoms, which, she explains in one flashback, represent determination and courage[2]. Vash’s refusal to kill is his attempt to keep Rem alive, and killing Legato causes a breakdown because breaking his promise to Rem reminds him of her death. Though he would never acknowledge it, part of the purpose of Vash’s activities is vengeance, though in the end he forgives his brother and stands by his promise to Rem, deciding to reform Knives.

Trigun also has some major comparative scenes that fit the traditional outlaw tale. For example, in episode three, Vash plays an altered version of the game of truth. He and Frank Marlon, who repairs Vash’s gun, save a town from bandits using only their fingers, which they pretend are guns, Vash with his in a pocket and Frank with his up against the lead bandit’s head. At various points in the series, mayors and sheriffs, along with other characters, break their oaths, welcoming Vash with open arms only to betray him in an attempt to get the bounty. For example, in episode six, Vash is hired by a woman named Elizabeth to protect her while she repairs the plant that protects the town. However, she sabotages the plant and locks Vash in it because she is a survivor of the July incident and wants revenge so badly that she is willing to sacrifice a town. Vash also has a habit of helping his enemies or taking service with them. For example, in episode two, Vash is hired to protect Mr. Cliff, stumbles upon his criminal activities, and seeks justice. In episode five, Vash saves the women who were holding him at gunpoint when their lives are threatened by outlaw mercenaries hired to kill or capture him. Vash defeats the outlaws and donates their bounty to the town, despite the fact that the townspeople had tried to kill him.

Contemporary outlaw themes also run through Trigun. The Greenwood theme is apparent in most of the flashback scenes with Rem, many of which take place in a garden on the ship and are accompanied by the symbolism of red geraniums. Vash also conforms to the idea of the good outlaw. His “outlawry does not bring shame upon [him], but instead proves [him] to be superior to [his] opponents, both in martial prowess and… in moral integrity” (Ohlgren xxiv). Vash meets his match in his draw with Wolfwood and later in his battle against his brother, though he emerges victorious. There is a repeated carnivalesque theme in Trigun, as the revealed corrupt officials are placed on the level of an outlaw while Vash acts as the official. Vash also plays the role of the trickster repeatedly, disguising himself once as a farmer in an effort to escape his outlawry and its heavy burden. Trigun also contains many elements of Monomyth; for example, Vash and Knives are pitted against one another in a battle over the fate of humanity and eventually must reconcile. In this reconciliation, Vash is able to understand and learn to control his destructive Angel Arm. In his battle against Knives and with his eventual understanding of his brother and also himself, Vash matures.

Trigun contains quite a bit of social conflict, especially between officials and the rich (the aristocracy and bourgeoisie), and the ordinary citizens. Citizens are often helpless against the corruption in towns, and are villein rather than citizens. In addition, the only example of clergy is Wolfwood, who does not hesitate to use violence to accomplish his goals and often abandons a moral value if it is inconvenient. Furthermore, ethnic conflict is rather obvious. Knives falls from grace because of the prejudice he and Vash suffer on the ship because they are not human. In addition, the members of the Gung-Ho Guns are all freaks of nature, mutated by the harsh Gunsmoke climate and are not welcome in society.

Interestingly, Trigun’s Vash the Stampede also fits the Japanese version of a good outlaw, which is rather similar to the European version. Like the European good outlaw, the Japanese outlaw fights injustice for the common good. A famous historical rebel known as Sakamoto Ryouma, a samurai who participated in the Meiji Restoration that moved toward ridding Japan of the oppressive warrior class, fought against the shogun, eventually forcing him to resign and allow a new government to form. Sakamoto Ryouma “did not live to see the Meiji government come into existence,” because he was killed in the chaos in Kyoto following the resignation (Jansen 335). Sakamoto’s rebellion resulted in “the 1868 collapse of the Tokugawa shogun’s military government (Bakufu) and the restoration of power to Japan’s Imperial family” (Huddleston). Outlaw tales about the Meiji Restoration are extremely popular in Japan, the most famous being Rurouni Kenshin, which is at least partially based upon the story of Sakamoto Ryouma.

Trigun takes the traditional Meiji Restoration tale and sets it in the far future on a desert planet far from Earth. Vash is no different from the traditional Japanese outlaw of these tales: he seeks to atone for his sins (the destruction of July) and also wishes to attain justice for the people. His quest for love and peace, as well as justice, leads him to better the lives of many people, despite the destruction he leaves behind him. In addition, he learns important life lessons along the way, and is able to reconcile his past and move on toward the future.

Vash the Stampede’s adventures are that of a contemporary outlaw. Trigun has many of the same elements as traditional European outlaw tales, and the series also contains allusions to historical Japanese outlaws. When looking at Vash in this context, one can easily see Trigun’s value as a contemporary outlaw tale.

Works Cited

Adam. “Trigun Characters and Weapons.” TheOtaku.Com. 27 Sept 2004. 10 Nov 2004 <http://articles.theotaku.com/view.php?action=retrieve&id=21>.

Huddleston, Daniel. “The Meiji Restoration.” Animerica. October 2000: 9-10, 34.

Jansen, Marius B. Sakamoto Ryōma and the Meiji Restoration. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1961.

Nightow, Yasuhiro. Trigun. Geneon Entertainment.

Ohlgren, Thomas H. A Book of Medieval Outlaws. Thrupp: Sutton Publishing, 1998.

Raye. “Trigun.” Spectrum Nexus. 9 July 2001. 10 Nov 2004 <http://thespectrum.net/review_trigun.shtml>.

[1] This is because the Japanese believe that twins have a connection that borders on magical. Often times in Japanese stories, twins have the ability to communicate with one another telepathically. This magical quality associated with twins may be because Japanese twins are very rare.

[2] Vash wears a red trenchcoat for this reason as well.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

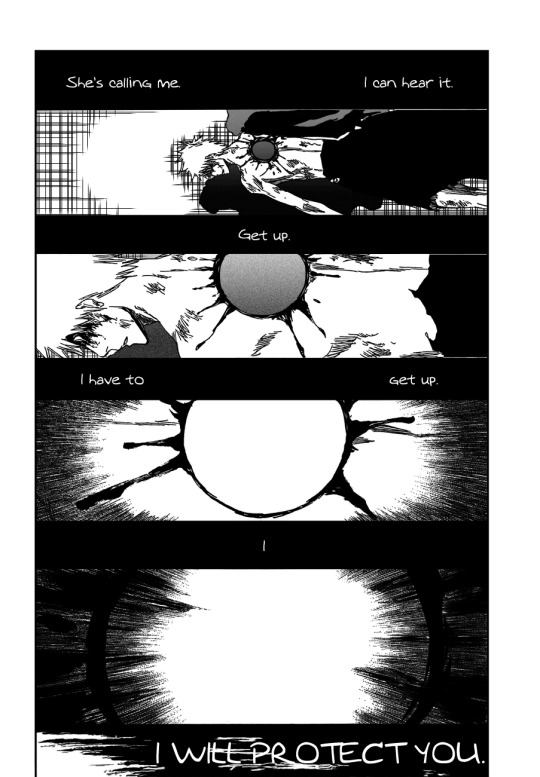

ANONYMOUS ASKED: I was following along a thread on twitter and an anti said when Ichigo laid dead on the ground with a hole in his chest in the Lust arc, that he didn’t say “I can hear her..stand up..I will protect her” before hollowfying. They claim he instead said “I can hear..stand up..I have to protect” using no pronounce directed at Orihime, hence NOT coming back from the dead because he wants to protect her specifically but because of his instincts to protect and he would’ve done it for any of his friends. They also said that Orihime didn’t scream “help me” but instead said “help” which triggered Ichigo’s instincts to protect, making him rise from the dead, hence once again making it clear this was never about Orihime specifically but about Ichigo’s instincts responding when hearing a voice in need (and this voice could’ve been from anyone amongst his friends) and how the hollow would not allow him to die regardless. Basically the English translations are incorrect and the raw version in kanji never used pronounces during these scenes. Is this correct and how would you respond to this?

There are a couple really important factors to address in this translation and why its English counterpart would supplement with pronouns specifically referring to Orihime; first, that Ichigo’s speech is meant to be broken and fairly incoherent because it’s conveying the idea that he as a human is focused on this sole objective as he’s dying. Second, that in Japanese, there isn’t necessarily a requirement for subject pronouns to form a sentence talking about a subject (the subject in question being Orihime) —this is a particular grammar rule that has no translatable equivalent in the English language, because they’re ultimately different structures entirely. I drop this phrase a LOT on here, but again, cultural context is important. Since you also sent this ask to my friend @ichinoue, there’s been some really excellent fan feedback about the structure of Japanese language and how it differs from English —this post in particular.

Now — onto the actual question:

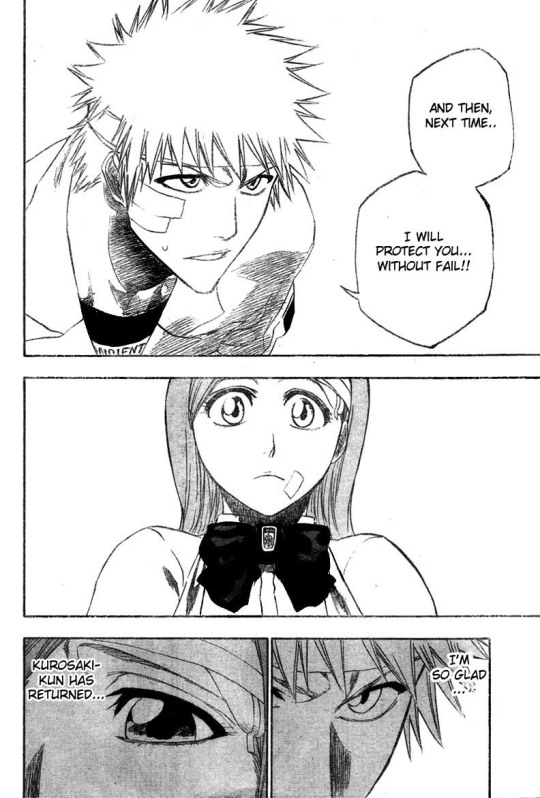

I think there’s definitely a possibility that Ichigo would have done this for his other friends, but only if this moment had also been preceded by Ichigo vowing to “definitely protect” or “protect without fail” those other friends. Kubo did write a scene like this, and made a pretty big deal about it, but that scene involves one specific character —not all of his friends.

This hollow transformation was written as a climax in Ichigo’s narrative arc for the Hueco Mundo saga —as the ongoing theme during this arc was about his struggle with his identity against his inner hollow as an ever-present threat. This could not be a more clear theme throughout this specific arc. There’s a lot of specific focus placed upon this struggle, his cooperation and subsequent training with the Visoreds, his lack of control despite his best efforts, and his juxtaposition of this struggle for control in his actual fights against the Arrancar and Espada. This is important to note, because in response to this, there is only one scene with one character that both:

Involves him promising to “definitely protect” or “protect without fail” a friend he cares deeply for (using the same character for “protect” that’s his namesake, no less —I’ll get into this tidbit more further down).

Functions as a foreshadowing tool, and is later double-downed upon as a foreshadowing tool by the same character as mentioned above.

When it comes down to it, the grammatical inconsistencies that come from translating between languages don’t have any particular bearing on this specific scene, because the intent was already made clear as early as Chapter 196. That’s how foreshadowing works —even if we as the reader don’t realize it’s happening until after the fact. What’s more, this is how Japanese functions as a language; it’s constructed around making sense of the context, which is why it doesn’t necessarily need subject pronouns to function or convey meaning. (Though I can understand why this goes over most Anti-IHs heads... their arguments depend almost entirely on pulling things out of context, which obviously doesn’t work.)

That said —

This scene says a lot. And even though Ichigo is speaking directly to Orihime so we understand she is the subject of what he’s saying, there’s a lot of additional meaning we can derive from this scene by reading (you guessed it) the context.

Ichigo is characterized early on by somewhat brash, irritable (though this is conditional), impolite, “punk”-like mannerisms. His speech tends to be informal (cultural context) as does his body language. However, we also know that he doesn’t say things lightly when it comes to promises and protecting others. These words carry weight, but there’s an additional sense of conviction conveyed through his respectful and formal gesture of bowing, his unwavering eye contact, and we as the readers can understand this without needing an explanation.

This is especially interesting because if IRs want to get smart about raws, then they should also already understand the additional importance placed on this scene when it comes to Ichigo’s word choice. Ichigo uses the character “護” (mamoru / ”to protect”) to convey his intentions. There are a lot of different ways to write “protect” in Japanese, many of which Ichigo uses when he makes these promises or talks about protecting others throughout the series. What makes his choice of “護” especially significant and piles on more and more contextual importance is that this is the same character for “protect” that is his namesake and the basis for his core character motivations. This is also only time throughout the entire series Ichigo specifically uses “護” to refer to protecting someone.

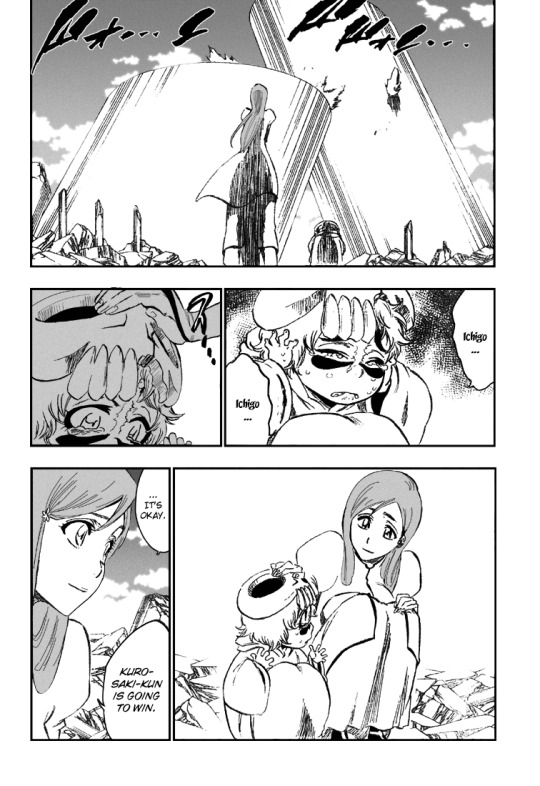

If the intention of this to act as a foreshadowing tool wasn’t clear enough, it is again referenced by Orihime later —just at the beginning of the fight between Ichigo and Grimmjow.

Already, we have a precedent set by Orihime’s direct involvement. This is the second scene in a pattern of foreshadowing the events of the Lust Arc.

The intent is clear; this is a theme in Ichigo’s narrative arc that involves Orihime, because it also involves the development of their relationship. Her fear of hollows, her fear of Ichigo losing himself to his hollow side, Ichigo’s struggle to expose himself to this power he relies on to win in battle while also trying not to lose himself. There’s an underlying theme of Ichigo and Orihime struggling to communicate with each other, desperately wishing to protect each other and going to whatever ends to do it, but ultimately thinking its a burden they must shoulder alone. They are both concurrently struggling with feelings of uselessness (Ichigo isn’t strong enough, Orihime can’t do anything) throughout this arc, acting as foils even if their individual journeys take different shapes. Even so, these conflicts are juxtaposed by the theme of “The Heart” (the bonds between people) that also keep appearing. They’re both frightened, they’re both feeling weak, feeling desperate, and yet still — they can understand one another.

So we have this pattern now:

Ichigo vows “Next time... I will protect you... without fail!” to Orihime with a sense of personal importance conveyed through the use of his name that is unmatched throughout the rest of the series.

Later, Orihime notes very plainly that “Whenever he uses strong words, it’s like he’s making a promise. I believe that he makes a promise to himself. I think that he expresses his words in feelings so that he will follow through.” The important takeaway being of course the forthright meaning, but also “When Ichigo says he’s going to [do something], he will [do that something] for sure.”

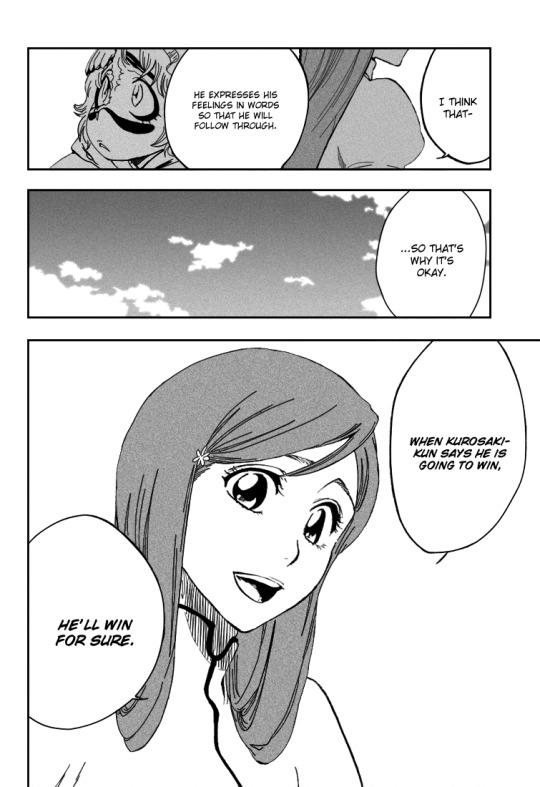

We all know what happens next —the character conflicts, the miscommunications, the belief that these are fights that need to be handled alone, the struggle against the powers of a hollow, the fear of exposure to that power... all culminate into The Lust Arc.

— CONTENT WARNING for canon-typical gore, blood, impalement, and body horror.

With the above established foreshadowing, we can see how it leads to this; When Ichigo says that “he will protect you without fail”, he will protect you for sure.

“To be clear, a total transformation to a hollow, is neither evil or good; it’s more like pure power .. so I made a voice of pure-hearted power that is unrelated, beyond the concept of good and evil so I screamed from a clear pure heart yet, at the same time there is some sadness and thought of Orihime in my head.”

— Masakazu Morita (Ichigo Kurosaki’s Japanese VA), on how he voiced Hollowfied!Ichigo during the Lust Arc.

“The perfectly hollowfied Ichigo ruminated over Orihime’s screams and was bound only by that objective.”

— Bleach UNMASKED

If what I outlined above wasn’t clear enough, Ichigo goes as far as to stab Ishida, his friend. It couldn’t be about anyone else. This specific theme has always very clearly been about Ichigo, Orihime, their relationship to each other, and their relationship to hollowfication as a concept.

I want to also be very clear here as well; with the established theme of Ichigo always fighting against his hollowfication, and Ichigo’s Hollow being motivated solely by self interest — it isn’t Ichigo’s Hollow responding to Orihime’s plea, it’s Ichigo’s humanity. Ichigo’s Hollow finally getting an opening to take over his host (to become The King and Ichigo, The Horse) is what revives Ichigo. But his vow to Orihime and his desire to fulfill that promise is what allowed him to cling to his humanity. The Hollow is motivated by survival instinct, not any desire to protect —that’s all Ichigo, just as it’s always been.

I think anyone who is still willfully misinterpreting this and holding Japanese language structure to English rules and conventions is seriously pathetic. Even in English, the pronouns have zero bearing on what’s being conveyed here. They can try and disprove IchiHime as much as they want as far as I’m concerned. The fact remains that at the end of the day, giving the Ichigo/Orihime relationship as much attention and dissection as they do goes to show that (a) they still perceive it as a threat and (b) there’s such a large volume of Ichigo/Orihime content to comb through to begin with —a fact they’ve vehemently denied for years.

Also like, IchiHime is canon. They’re happily married. They have a family together. Just tell them to take the fucking L. I get secondhand embarrassment from watching them rehash the same old bullshit time and again.

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Think Happy Thoughts!” Musings on the subject of Happiness in the Car Share world...

"All we wanted to do is make happy television" - Peter Kay

The words ‘happy’ and ‘feelgood’ are often used to describe the appeal of Car Share, so I’ve put together some thoughts on how the subject of happiness is addressed throughout the series. Please feel free to agree / disagree / add your own observations! :-)

In the very first episode of Car Share, having barely spent an hour in each other's company, John and Kayleigh have the following exchange about the car share scheme:

K: No, I'm happy sharing with you.

J: Oh right. Yeah, I am. I mean, me too.

K: Good!

And so the scene is set for what is surely the overarching theme of Car Share: the journey towards happiness of two unattached people with unfulfilled dreams. The 'happy' word is referenced repeatedly throughout the two series and is a pivotal factor in the unexpected cliffhanger ending of S2E4 which we now know will be resolved in a 2018 Finale episode (hurrah!)

So what does happiness mean to each of them and how does this change throughout the two series? Let's take a look at the evidence...

The first major discussion around the subject takes place on the day of Old Ted's funeral, when Kayleigh ponders whether Ted was happy with his life. John affirms that he "seemed happy, had everything y'know, good job, lovely wife". This suggests that John's idea of a happy life is small scale and rooted in the everyday, and he further clarifies this when he says "Happiness for me is about enjoying the odd good time rather than expecting one constant party in life."

Kayleigh on the other hand, despite counting her blessings with her family and friends, still laments that "all I've ever wanted is to meet the man of my dreams and have babies." John tries to console her with talk of online dating, though he is clearly uncomfortable with her choice and this only becomes more apparent as Series One progresses.

In effect neither has what they think would make them happy, but John backtracks to say that he's always been happy on his own – or at least "I was until you pointed it out." Already Kayleigh has challenged one of the key things he believes about his life, which is another important theme of their journey together: some of the very things John professes to dislike or disapprove of (e.g. people singing in his face / management fraternising with staff / employees bunking off work) he then ends up doing under Kayleigh's 'life-is-for-juicing' influence. And not only does he participate, but he clearly enjoys himself along the way too.

It is by being very direct and wearing her heart on her sleeve that Kayleigh is able to draw things out of John which contradict what he tells her - and what he tells himself. It is apparent that what he believes makes for a happy life is not necessarily what he he is experiencing day to day. He has vague hopes for the future - "hope I'll have moved on by then" - but no coherent plan to make any changes happen. This is also evident in his approach to his long-muted musical ambitions ("Christ, what are we doing here Jim?" he asks his Compendium band mate when discussing a bottom-of-the-bill gig at a gymkhana).

In counterpoint it's also interesting to note that Kayleigh's outlook on life isn't static either. Her former 'party girl' lifestyle is described in S1E3 but she admits she "can't do it any more", which harks back to John's assertion that 'one constant party' isn't necessarily the basis for a happy life.

In S1E4 the sole reference to happiness comes in the classic car wash sketch when Kayleigh's aquaphobia triggers a panic attack which John helps her to overcome by gripping her hand and urging her to "Think happy thoughts!" In contrast to John, who has a natural tendency to back away from thoughts which scare him, Kayleigh copes by submerging herself in an imaginary watery world which she happily swims through, bestowing smiles and applause and blowing kisses at fishes.

This contrast in their different approaches to fear and happiness is also underscored in S1E5 when the song 'Have A Nice Day' comes on the radio. Kayleigh immediately classes it as "a nice happy song" until John urges her to 'listen to the words': "it's actually quite a bitter song about a man who's not happy." Not only is this a subtle echo of the two occasions when Kayleigh urges John to listen to the words of a particular song, but it also demonstrates that she can sometimes take happiness at face value, whereas John sees and understands the underlying dissatisfaction behind the facade. As he says of Old Ted in S1E2, "he seemed happy, but who knows what goes through people's minds?"

In the last episode of Series One and the first of Series Two there are no direct references to finding happiness; instead it is played out in the situations and demeanours of the characters as they face separation but ultimately wangle their way back together via a mixture of shy gift giving, wistful looks, repeated phone calls, teasing laughter and sly determination, culminating in soppy smiles and an understated commitment to carry on spending time in each other's company.

Which brings us to S2E2 and my favourite scene of the entire series: the 'fluffy drunk' ending to an entertaining eventful journey home in the company of a large, inebriated smurfette. The broad humour and drunken ramblings give way to a poignant exchange where Kayleigh's adorable fluffy/funny drunk bravado enables her to ask John if she makes him happy. His softly-spoken answer - "Yeah. Yeah, you do. Very much," - is as heartfelt as her question and marks the point where they are the most open they've ever been with each other about their feelings. And as they naturally go to act on them.....Damn that smurf!

But there is no question that Kayleigh now sees that her curmudgeonly colleague might well be the man of her dreams and that John's idea of happiness no longer hinges on being on his own. To paraphrase Michael Jackson, he used to talk of 'I' and 'Me' but by the middle of S2E4 he is saying 'Us' and 'We'.

Perhaps the highpoint of their happiness in this 'last' episode comes as they sing along to Billy Ocean, laughing and holding hands on the drive home. But while they might make each other happy, John's fear of change is never far from the surface and he retreats into his default position of enjoying "the odd good time" rather than reaching for the larger slice of happiness which Kayleigh offers him. Ironically (and for the second episode in a row) it is talk of the Christmas Team which throws a bucket of water over proceedings, as Kayleigh's hopes for something more are dashed:

J: Are you not happy the way things are?

K: Yes!.... I dunno. Yeah. Yeah, kind of....

The beautifully acted scene which follows has a similar effect on the viewer: our hopes for a happy ending for our heroes are seemingly dashed too, as John's panic over having to confirm or even confront his feelings causes him to lash out with an uncharacteristically harsh accusation:

J: I'm not like you, y'know? I don't live my life in a bloody fairytale!

K: I don't live in a fairytale John, I just want to be happy!

For the second time in as many minutes John makes the mistaken assumption that his happiness with the status quo should be sufficient for Kayleigh: "And we are happy aren't we?" But this time she can't hedge or hide her feelings, and she tells him outright that she loves him but has to let go because "it's killing me you don't feel the same."

In the most bittersweet manner, John's dedication indicating that he does feel the same way is aired on Forever FM within seconds of Kayleigh getting out of the car. True to their characters, Kayleigh has been open and direct in her approach whereas John has gone all round the houses. Ultimately both have arrived at the same destination but, tragically, they appear to have missed their connection.

The final words spoken (in what was touted as the final-ever Car Share episode) are John's resigned concession of "I'm done." But as we have since learned, the series isn't done and therefore neither is John. Throughout both series and on his journey(s) he has learned that something other than his safe and singular routine can make him happy - very much so. Similarly Kayleigh, contrary to her declaration in Series One that she's "not going to meet someone by sitting on my arse," has found that what makes her happiest is the idea of sharing her life with John.

So we look forward to the Finale sometime later this year with renewed anticipation that "all will be revealed" to them and both will finally find the happiness that fate has steered their way via the Car Share programme. It’s a happiness which is sure to be shared by viewers up and down the land...!

#peterkaycarshare#car share#john x kayleigh#peter kay#sian gibson#happiness#happy endings#my musings

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Simpsons, Parody, Satire, Strong and Weak Characterisation and passing references to James Joyce’s Ulysses.

A while back I had small seed of an idea, created by, suitably, watching two episodes of the sadly ended PBS Idea Channel back to back. The first was “Is Homestuck the Ulysses’ of the Internet?” and the second was “A Love Letter To The Simpsons”.

At the time, I was reading an annotated copy of Ulysses, and one of the things that struck me was the meaning behind the name of the book. Joyce, it seems, was obsessed by the level of detail that the mythological Ulysses (or Odysseus) is portrayed in Homer’s (not the yellow one, the poet) Odyssey, calling him the only fully realized character in literature. This is what gives the novel its name; Joyce is trying to examine a different, contemporary (at least to him) character in as much detail as his mythological counterpart, and it appeared to me that we have another modern piece of art that performs a similar function.

(My apologies if the theme song is now in your head)

Obviously, no individual episode of the Simpsons fills this function, but taken as a whole series there are two factors that I think allow it to. The first is of course the length of the series, but the second one I think is the fluidity of the characters. The Simpsons are caricatures, but they are not consistent caricatures. Homer is, depending on the episode, a loving, if not particular bright, family man, a layabout slob, a hard line anti-intellectual, an abusive drunk, or a depressed man in a bad situation. Lisa can be a tiny crusader with no regards to others, a desperately lonely child, a super intelligent little girl, a mischievous little minx or a fairly standard school child with friends and a love of toys and cartoons. I wouldn’t say that the Simpsons provides any characters that Joyce would argue as well rounded, but rather that we are shown multiple cartoon portraits of each character (well, the main cast at least), which we can then deflate back to a central characterisation. This ballooning of character traits in theory allows the series to have its cake and eat it as well; outsized characterisation for when it is needed to make the jokes it is trying to make, and an underlying character that provides the backbone of the series and allows it to pull off the more emotional elements when needed.

An important consequence of this, and one I feel that is obvious but is important enough to restate, is that for the Simpsons, characterisation is a consequence of the direction of the comedy they are attempting. The Simpsons began life less as satire of the real world, but as a parody of what was then the default model of sitcom’s; a family ruled over by an intelligent and loving father figure. The Simpsons flipped this around for everyone, with the possible exception of Marge. Homer is a buffoon, Bart has no respect for authority, and Lisa is the forgotten middle child who legitimately had something to say. As Dan Olsen in his Folding Ideas video on Homer points out, this is one of the reasons why Homer’s personality changes so much for the worse as time goes on. He is still attempting to parody sitcom fathers, but now those fathers are, as often as not, parodies or copies of himself, dragging him further and further away from his starting point. There has been efforts to reverse this (most notably the Movie, which is entirely focused on Homer trying to redeem his character), but his core characterisation has undeniably changed over the years.

I bring up the difference between parody and satire for a reason. These are obviously related forms of comedy; parody is simply satire applied to works of fiction rather than reality, but I think there is a bigger difference than that. Satire is bigger than parody, just because what it aims at is real life, not self contained pieces of fiction (it’s also far more inherently political, since creating satire itself gives a message about reality, and yes, satirising “both sides” equally is still creating a message that both sides are terrible). A lot of the best Simpsons episodes operate as parody that has elements of satire; Homer the Heretic is a good example. While the episode definitely contains elements satirising religion, the majority of the actual comedy is entirely character and parody based; its Homer having a great time not going to Church, with the ending twist about the importance of religion in making people do good. Any satire on religion is brought down to the level of the (let’s face it, pretty small and petty) characters. A lot of the worst Simpsons episodes respond the other way; they keep what they are satirising the same size and weight, but inflate the characters up to that size and importance, past what they can actually fit into. That’s not just a knock on latter sessions either; I legitimately loved the episode “Homer Goes To Prep School” which satirised doomsday preppers by a.) having the apocalypse be localised and not really that bad and b.) not actually showing what happened, just the aftermath where everything is fine, instead focusing on Homer and the preppers, but there has been a noticeable shift from character based parody to satire as the show goes on.

And on. And on.

One problem that a lot of really long running series have is their ability to keep commenting on the real world while the real world itself changes rapidly around them. A good example of this is comic books, particularly ones like DC and Marvel which try to keep everything not directly related to superheroes as it is currently, at least in the main lines. This causes a few issues, such as characters like Reed Richards and Tony Stark seeming to be unable to actually use their tech in a productive way on a social scale outside of beating up bad guys, but to be honest I think that one of the biggest issues is that, and I mean this in the fairest way I can, satirists are not really on the cutting edge of most things.

Satire is inherently a reaction based form of art. It requires something to be satirised and to make good satire, you need to have at least some knowledge about what you are trying to satire. For a mass market audience you also need to be able to express that satire in terms that the audience will get. Not necessarily all the jokes or riffs need to be obvious, but most of the audience need to be nodding their head most of the time. Ideally you want them to be laughing at what you are satirising, not with, because that’s how you get “totally ironic” Nazis and Peter Griffin.

The problem is that this requires the writers to have a fair wider knowledge and interest base than they actually practically have. South Park is a really good example of this; Parker and Stone’s best work is usually base either around religion or parodying stories, because that is where their interests and understanding respectively appear to be. The worst South Park episodes are usually the ones that are created within two weeks based on the most surface level understanding of the circumstances. It is this surface level understanding, I think, that is why they fall back on “both sides are bad” so much; it is easier to just aim at the most visible positions on an issue than to actually dive into it, and South Park’s incredibly short episode production schedule just doesn’t give you that time.

The Simpsons has the same problem, and it has gotten worse over time as the world changes. This is most visible I think in any episode involving technology; I can’t think of a single Mapple (get it? Like Apple, but so they won’t get sued!) joke that actually lands in the entire series, but you can also see it in how they have struggled to keep up with the changing tastes of young people, both for Bart and for Lisa (although the one where Bart gets into a game where you summon plastic monsters by rolling balls is pretty good). The episode about participation trophies is especially bad at this; it is basically a full 24 minute rant about kids today getting too many trophies.

Basically what I’m trying to say is that sometimes satire doesn’t land because it isn’t being taken seriously enough.

Strong and Weak Characterisation: The Tragedy of Barney Gumble.

Another weakness of the fluid characterisation of the show emerges from how the show uses its characters episode to episode. Let’s talk about the difference between strong and weak characterisation.

Suppose we are dealing with a scene. A guard enters the royal throne room, and announces the arrival of a prince. If the story is focused on the prince, then the prince will usually have strong characterisation. He will have motivations, fears, weaknesses, some kind of tragic flaw perhaps, or a backstory. Conversely, while the guard is a character, that character is weak; limited to perhaps a remark about the condition of their armour. They are a character but their role in the story only needs to explore the full depths of them sticking their head in the door and announcing the prince (you could have had it the opposite way around; the prince is random noble #194 and the guard is a Sam Vimes style protagonist). The level of characterisation is set by the story.

As an aside, this is what is meant by people wanting strong female characters. It isn’t just a case of stories about physically strong action heroines, but it's about telling stories where the strong characterisation is given to female characters. An important thing to remember when analysing stories on a social meta level, as you do when talking about trends and widespread failings, is that while you might argue a story calls for a certain spread of strengths of characterisations, ultimately the choice of what story to tell falls on the author, and so the question then becomes why the author chose the particular spread of characterisations they did. This even applies to stories based on real life; Hamilton the Musical notably had its subplot about slavery that ran through several songs mostly removed. You could, absolutely, make a musical that made that a core part of the narrative.

Anyway, back to the Simpsons. I feel the best characters to examine how the Simpsons use varying strengths of characterisation are Homer’s two foils; Ned Flanders and Barney Gumble. Both represent things Homer could be; Ned is the devoted family man and hard worker, while Barney is an alcoholic wreck.

Famously, Ned lent his name to the trope Flanderization, where one aspect of a character becomes increasingly blown out of proportion until they become nothing more than a cartoon of that one trait. While I think this happened to a degree with Ned, the shift is not a uniform one, and the extent it happens depends on the strength of characterisation given to Ned by any given episode.

Ned started off as a parody within a parody. The Flanders are exactly the same kind of sitcom family the show was created to lampoon, allowing them to loop back around and comment on their own commentary. Over time however, the aim of the show shifted and it became more focused on attempting political satire, mainly from a left wing, fairly atheistic stance. Ned, who had previously been established as a keen church goer, was now the go to example of a hardcore creationist right wing christian, with his sons, Rodd and Todd, getting increasingly more coddled and cowardly.

Except that...here’s the thing. The original Ned was still there...but mainly in episodes that have him as a major character focus, where he has strong characterisation. Some episodes, like season 12′s I’m Going To Praiseland are far more focused on his grief at the loss of his wife, while others focus on his relationship with Homer and the coddling of his kids. A lot of the religious fanatic Ned, with the exception of The Monkey Suit in season 17, comes not from his moments of strong characterisation, but his moments of weak characterisation, when he is used as a one off gag in the episode, such as him taking Rodd and Todd into a bomb shelter upon hearing Lisa is a Buddhist.

The show itself treats each incarnation of Ned as essentially his own character, not just in the treehouse of horror episodes, but as viewers we build our characterisation of him based on all the appearances we see. Strong characterisation and weak characterisation for the same character, all mixed in a blender.

I actually think Barney’s characterisation history is a lot worse than Ned’s. Another one of the factors that allows The Simpsons to be so long running is its ability to snap back to a default state after every episode. Kid’s get stranded on a deserted island in Das Bus? Get rescued by, oh, I don’t know, let’s say, Moe. Homer loses his job? He will get his job back. Ect ect ect. This snap back is actually really important for the longevity of the series since it means episodes can be shown in any order and you don’t need to have tuned in to the previous 27 series to understand what’s going on.

The big exception to this tends to be character relationships. Apu doesn’t snap back to being a bachelor after Manjula is introduced (although given that the writers don’t seem to have a clue what to do with her...), Skinner and Krabappel had an ongoing relationship subplot until she ended up with Ned (which then tragically was cut short by the real life death of Edna’s voice actress, Marcia Wallace) and Comic Book Guy’s girlfriend/wife Kumiko remains after her introductory episode and seriously Simpsons writers could we stop with the continued introduction of (usually designed to be attractive) female characters who are partnered with existing, usually non-classically attractive male characters and then receive little characterisation outside the nagging wife stereotype? I mean, seriously, this is a recurring problem with the series, how it handles adult female characters, particularly ones in a relationship, and it isn’t one that I see brought up in those lists about why the Simpsons has stopped being funny or whatever. Marge has always had the weakest characterisation of the main Simpsons, and is the one least changed from her original sitcom counterparts; the difference is that she’s married to Homer instead of Ned, most other character beats are kept the same unless she is needed to have a one episode vice like gambling or road rage and gaaaaaaahhhhhhhhh.

Okay, hold onto that paragraph, since it's worth exploring in more detail but this post is already getting overly long, so I guess look forward to a second Simpsons meta on how it handles marriage, women and the fact that of the writer’s credited for writing 10 or more episodes of the series only two are women so okay that might be another long one.

Anyway. Back to what I was saying.

A piece of character development they tried to keep around was Barney Gumble going sober. He cleaned up his act and started to rebuild his life. I actually really liked sober Barney; for one thing it was an actual ongoing character arc, and for another it meant that he now contrasted comedically better with Homer, who is eternally stagnant. This did mean that the position of Homer’s negative foil, what he could be if things went wrong, was open, but we have plenty of characters around for that. Moe, for instance.

Actually Moe could be another instance of a character who’s characterisation got steadily weaker and based entirely around how horrible his life is as time goes on...it is really easy to get sidetracked with the Simpsons, they have such a huge cast of characters and they are so bad at actually using them...seriously why haven’t we had an episode exploring Lisa or Marge’s fair weather friendship with the other existing female cast?

Anyway, going back to the male cast members since I want to actually finish this post before starting a new one on how the Simpsons handles women, the status quo is God, so Barney returned to being a drunk, specifically because it was more difficult to come up with jokes for him. And while I understand why this would be an issue for comedy writers, to be honest it has always been kind of disappointing for me to see.

The Simpsons has always suffered from desperately trying to keep up with the times while not allowing itself to actually change with them. If, as I stated above, the Simpsons works best when it is a character driven parody with satirical elements shrunk down to fit into character’s lives, then of course it will be unable to properly satire an ever changing world with a static cast who are distorted into the roles a particular episode needs them to be. By the same token though, it can’t just continue onwards with the current model of allowing the characters to simply drift without a core characterisation that is deliberately changed. The factors that allow the Simpsons to survive so long are also what is killing the series, and that’s just sad.

#the simpsons#homer simpson#homer#marge#marge simpson#lisa#bart#lisa simpson#bart simpson#apu#apu nahasapeemapetilon#moe#barney gumble#meta#long post#james joyce#Ulysses#satire#parody#because what the world needs right now is 3000 words of Simpsons meta

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The experientiality of narrative

An enactivist approach.

Marco Caracciolo

Caracciolo starts his writing outlining experience and consciousness as privileged objects of philosophical investigation and states his objective to merge this with cognitive sciences for a theory he refers to as Enactivism. This involves an exploration into cognitive psychology, neuroscience and philosphy of the mind. He focuses on embodiment, experience and interaction to underly claims of readers engagement with narrative, advocating what he refers to as the E-approach to experientiality of narrative. The ‘E’ stands for:

-Embodied, Embedded, Enactive, Engaged and evaluative.

His goal is to provide insights into our experiential engagement with stories through themes of autonomy, sense-making, emergence, embodiment and experience. His approach enlists a merging of what he refers to as ‘non-professional’ readers and their emotional/immersive engagements with narratives and the more ‘self-conscious’ literally critical readers. In other words imagination and forms of meaning making mediated by propositional thought and socio-cultural appraisals.

Stories themselves offer themselves as imaginative experiences because of the way they draw on and restructure the readers familiarity with experience itself. What characterizes an experience is the structure which seems to straddle the divide between real and fiction. He argues that engaging with stories can be an imaginative experience to account for the difference between engaging with the world and engaging with narrative but that these are not two kinds of experiences in a strong sense.

At the core of any narrative interaction is the tension between the story and what he calls the ‘experiential background’ of the reader. This is because consciousness is not a passive taking of sensory information from the outside world but a structure of interaction between embodied subjects and the environment they negotiate. The engagement is always projected against ‘experiential background’ - a repertoire of past experiences and values that guides peoples interaction with the environment.

Fictional storytelling can break the laws of reality whether by representing physically or naturally impossible states of affairs or by challenging representational conventions and socio-cultural assumptions about the real world. While imaginative contents and experiential qualities of fiction may deviate from real world engagements, the underlying structure of interaction is the same. Readers (or recipients) respond to narrative on the basis of their experiential background.

Two psychological mechanisms play a role in this process:

-Triggering memories of past experiences or experiential traces.

-Mental simulation, which allows readers to put together past experiential traces in novel ways, therefore sustaining their first person involvement with both fictional characters and the spatial dimensions of story worlds.

Stories need experiential input but also produce some output, since they can bring about a restructuring of each readers experiential background by generating new ‘story-driven’ experiences.

The experiential background of recipients includes the socio-cultural contexts that frame their encounters with narrative. He makes a case for the involvement of bodily experiences in the interpretation addressing the larger issue of how narrative can tap into readers past experiences and provide new ‘story-driven’ experiences on the basis of their experiential background. For example we can look at how emotional reactivity can be provoked by narrative. We might cry while watching a film because we recognize the film is dealing with values that are part of our own experiential background. Narrative can leave a mark on readers at the level of their more self-conscious and culturally mediated judgement about the world.

It has been widely assumed that stories work by representing events, situations, characters and mental processes or in other words ‘ narrative is the representation of an event or a series of events (Porter Abbott). The enactivist viewpoint challenge that definition by urging that experience is not a matter of representation, but rather an interaction with the world guided by the values that permeate the subjects experiential background. A large portion of his argument is dedicated to reconciling this insight with the assumption that stories are representational devices.

This is because stories, and language, are inherently representational. Engaging with literary texts does involve representations in both the semiotic and cognitive science sense. Semiotic and mental representations play a role in the readers interaction with a story but it is not the whole picture for the experience readers get cannot be adequately reduced to mental representations. this is because experience has to do with how things are experienced, with a field of possible interactions relating to the context -evaluative and embodied- creating a sense of complexity. Mental representations in his context refer to symbolic structures that carry content by representing many different kinds of objects eg. concrete objects, sets, properties, events and states of affairs in this world, possible worlds, fictional worlds as well as abstract objects such as universal and numbers.

As both reader-response and rhetorical narrative theorists have recognized, stories have an impact on readers, provoking reactions in the form of mental imagery, emotional responses, moral and aesthetic judgement and socio-cultural evaluations. during the experience of a story these responses will often come together in interesting and surprising ways. for example we will try to show that readers bodily involvement can strengthen their engagement with a story at a level of social-cultural meaning.

The aim of cognitive approaches to literature is not to prove scientifically readers interpretative response to stories, rather it is to show that these socio-culturally nuanced responses can be placed on a continuum with more basic modes of interaction with the world. Caracciolo states a tendency to acknowledge that cognition is embodied and situated or in other worlds, inseparable from the subjects body and from the context it is situated.

Gibbs writes

“Embodiment may not provide the single foundation for all thought and language, but it is an essential part of the perceptual and cognitive process by which we make sense of our experience in the world”

The self, personal identity and how we come to understand the behaviour of others

Psychologist Jerome Bruner has helped popularize the view of Narratives being instrumental in shaping our personal identity. An important precedent to the next debate centered on the ‘problem of other minds’ which asks: what is the core mechanisms whereby we make sense of other peoples intentional behavior?

traditionally this debate has been dominated by the disagreement between theorists and simulation theorists. The former hold that we come to understand the actions of others by way of inference from acquired or innate theory known as ‘folk psychology’.

( In philosophy of mind and cognitive science, folk psychology, or commonsense psychology, is a human capacity to explain and predict the behavior and mental state of other people.)

By contrast philosophers such as Robert M Gordon and Alvin Goldman insist that we explain other peoples behaviors by “putting ourselves in their shoes ie by running mental simulations of their mental states. Some versions of simulation theory are based on nueroscientific evidence, in particular on evidence linking mental simulations with the firing of so called “mirror-neurons”

Gallagher and Zahaui work is a deliberate attempt at linking cognitive-scientific research on consciousness, the self, perception, action and the understanding of other people’s mental states. They suggest a way of uniting this view with enactivism. They argue that as far as primary, bodily inter-subjectivity is concerned, there is no problem of ‘other minds’. Since as phenomenologists have long pointed out - we have direct access to other peoples bodily intentionality. This interaction involves simply a form of bodily attunement.

Stories play an important role in understanding other people’s behaviour. In the case of someones puzzling action, a narrative can facilitate understanding by filling in a rationale when it is not immediately obvious. Which goes back to the argument on Mental and semiotic representations. They exist in an object based schema and representation works by referring to a spatio-temporally locatable entity such as an existent or an event. Experience however, is a field of interaction and evaluation that cannot adequately be described in this object based term. The recipients experiences are often more complex than usually thought which has an implication on the relationship with stories as representational artifacts.

What are the expressive devices through which narrative can produce experiential responses in recipients / How can we encourage the audience to respond to the represented event and existent.

Our story cannot represent the characters experiences, but only events and actions whose experiential dimension is supplied by readers though their own familiarity with experience. The concept of expression plays a major role in my account of how experiences can be conveyed by semiotic and thereby representational artifacts.

Unlike representation, which works by refering to a self contained object, Expression is deeply embedded in the context in which an experience occurs. The main difficulty that arises is from our imagining of the experience. For instance pain is a concept we have a name for and therefore quite easy to grasp. If a heavy object falls on my foot i may experience pain and yell out. the yell is an expression, not a representation of pain because it is a way of reacting to an experience that is inextricable from it’s context.

Caracciolo argues that for expressions of experience to be understood one must have found themselves in a sufficiently similar situation Thus we can invite someone to imaginatively respond to something on the basis of his or her past experiences. When we see a heavy object fall on someone, those responses are often unavoidable as it isn’t uncommon to experience something similar to pain that manifests in a twitch or wince - a reaction that signals that we are imaginatively experiencing the other persons pain. the experience does not lie within the foot, nor the object, nor the fall, but in the way these objects interact with the subject and with his or her neural wiring.

Memory traces or experiential traces trigger the sensory residue left by a large number of past occurences.

In sum, representation and expression are different layers or aspects of the same process of engaging with stories (intertwined). Language is inherently representational, because it asks interpreters to think about - or direct their conciousness to - mental objects like events and existents . But it is also experiential because it can express experiences by constantly referring back to the past experiences of the interpreters, and by inviting them to respond in certain ways. Note that representation does not come in degrees: something is representational or not. By contrast the experiences created by stories vary considerably in intensity, depending on the strength of the interpreters responses, which in turn reflect the tension between their past experiences and the textual design.

.

0 notes