#captain marryat a rediscovery

Text

Frederick Marryat was born in the City of London on 10th July, in the year of the September Massacres in Paris. He died in a time of revolutions, and in the fifty-six years which lay between 1792 and 1848 the political map of the world changed more than it has ever done again, until our own time. He was a few weeks older than Shelley, and a few months older than Edward Trelawny, to whom, indeed, he was far more akin.

— Oliver Warner, Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#biography#oliver warner#captain marryat: a rediscovery#happy birthday captain marryat!!!

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

🔪: for the “worst of” / worst moments for Marryat! 🙂

Ohhhhh man, I chuckled a little bit ruefully at this (as much as I walked right into it). I genuinely like Marryat and feel sympathy for him: but there is a lot of material here. Particularly since our modern mores are pretty hard on warmongering imperialist colonialist guys, and that's like the fabric of Marryat's entire world.

Every so often I think about Marryat at his fashionable peak, living in London in a house full of animal pelts and exotic curios like some cartoonish Imperialist overlord. As his daughter Florence described it, literally using a synonym for 'looted':

There was scarcely a room in Wimbledon House that was not decorated with some of the spoils which Captain Marryat had collected in his travels round the world. A Burmese shrine with silver idols, rifled from a pagoda; the carved tusks of a sacred elephant; opossum skins from Canada, embroidered with porcupine quills and coloured beads; toys in tortoiseshell and ivory, with precious stones and curious shells, were scattered everywhere, recalling memories of the Rangoon war, America, India, and the Celestial Empire.

— Florence Marryat, The Life and Letters of Captain Frederick Marryat

(See also: how DID Captain Marryat get all those wonderful objects to donate to museums?) It's apparent that Marryat's culture allowed for raiding the corpses of fallen enemies—he cut precious stones from dead Burmese warriors, and described picking over the dead bodies of the French for valuables in Frank Mildmay.

If you ask Marryat's biographers, they probably concur that one of his lowest points had to be that time he got into a brawl in Trafalgar Square, on Guy Fawkes day in 1834. It “illustrates a disagreeable side to Marryat’s character,” wrote Oliver Warner, and Tom Pocock lamented that it “should have been a trivial and easily resolved misunderstanding.”

A nobody civilian named Johnson Neale, who was a fan of Marryat’s works, tried his hand at writing nautical novels. But Marryat was offended by a fictional character based on Admiral Troubridge, and despite Marryat writing many hostile caricatures of real people in his own novels, he began attacking Neale in his Metropolitan Magazine. Neal challenged Marryat to a duel, Marryat declined the duel on the grounds that Neal was not his social equal and heaped on some more insults, and eventually the two men ran into each other in a public place:

‘Keep your distance,’ replied Mr. Neale, extending a walking-stick, ‘You are a liar, and a scoundrel, and only want the courage to be an assassin.’ To this charge Captain Marryat did not answer, but began to untie his cloak, which Mr. Neale gave him full time to do, and, stepping into the road, placed himself in a position for the attack, which he evidently meditated.

Having allowed Captain Marryat to divest himself of his cloak, and hang it on the palings of the National Gallery, Mr. Neale no sooner observed him in a fair state to defend himself, than he struck at the Captain with his stick. Several blows now quickly passed between the combatants; Mr. Neale being a man of half the calibre of the Captain took the advantage of his activity, and, as fast as he struck Captain Marryat, he retreated a step beyond his grasp. In doing this, however, he backed against a heap of Macadamized stones, and immediately fell backwards.

Captain Marryat then flung himself upon his assailant, and planted his knee upon his chest, and placing one hand upon his throat, with the other he gave him several blows on the head with a stick [...] Mr. Neale at the same time made a violent effort, and Captain Marryat rolled over in the mud. Mr. Neale now sprang to his feet, as did also the gallant Captain, who was again advancing to the attack of his unarmed foe, who, having lost his stick, caught up some of the rubbish, on which he had fallen, and directed it at the Captain’s face.

— Oliver Warner, Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery

The bitchfight continued, cops were called, and both Marryat and Neale appeared at Bow Street, charged with causing an affray. Marryat refused several attempts to defuse the situation and apologise. It doesn’t reflect well on him, but at the same time, you can make some excuses for his volatile temperament.

It’s less easy to excuse some of Marryat’s truly awful takes on social issues. He did eventually move to a position of strongly condemning slavery, but not before some really yikes maybe-slavery-isn’t-so-bad moments in Frank Mildmay and Newton Forster in particular, which is dismaying, but probably not too shocking for the son of a career anti-abolitionist. (One time, when I was trying to look up Marryat’s older brother, also named Joseph, I found father and son in the Legacies of British Slavery database. It definitely answered some questions about the family’s privilege and wealth, not in a good way).

As soon as I started reading Marryat, it struck me that his moral compass was slightly askew. Which might be true enough, although that’s a very harsh judgement to pass on someone. (And I would hate to smugly think that of course I’m so much less racist and bigoted than Marryat, when who knows what unquestioned prejudices and bad attitudes are in my heart, and how much progress I still have to make to become a better person than the world that created me.)

I am currently reading Olla Podrida, as Marryat called his assorted magazine essays that he collected together in a book, and my God does he sound like a stupid obstinate Tory bastard sometimes. He has some empathy for poor and marginalised people, but then he snarks any attempt to create a social safety net and sneers that, thanks to the new Poor Law Bill, “the poor man walks into the vestry with an insolent demeanour, and claims relief, not as a favour, but as a right.” (And??? You really wrote all that and think you sound like the good guy here, Fred??) I haven’t wanted to throttle the Captain recently, but it’s never too late for a revival of that sentiment.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#biography#asks#ask#historical figure emoji meme#long post#you want the dirt on marryat i can arrange that#i love him and would fight him#british empire#i need to square up with the fact that so many of my interests revolve around Empire#which explains why so many of my fave historical figures are kind of bastards#or accessories to it#1830s

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

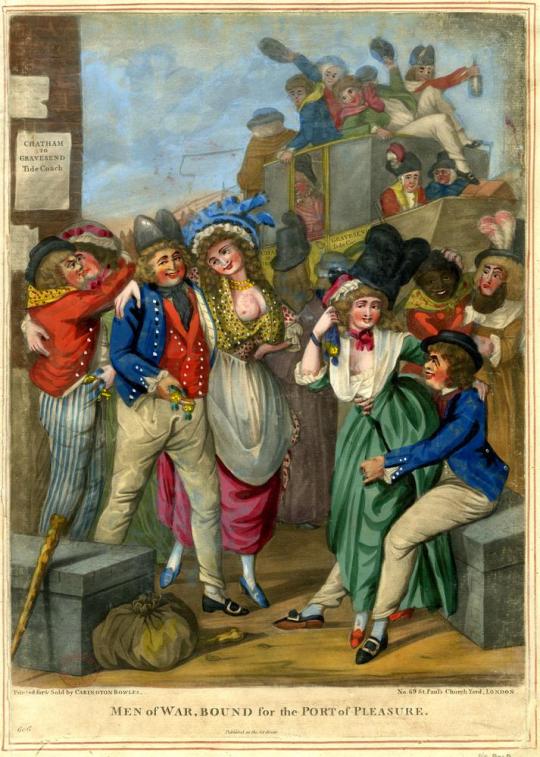

Marryat wrote, originally, for fun. He found he was a born writer. Later, he needed money badly, and was constrained to turn the jaunt into a grind: but of literary solemnity he was innocent. He was indeed, 'non-pompous', as a sailor the worse for liquor is described in Poor Jack.

— Oliver Warner, Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery

'Men of War, bound for the Port of Pleasure': 1791 mezzotint after Robert Dighton.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#british literature#english literature#writing#biography#oliver warner#captain marryat a rediscovery#sailors#naval art#robert dighton#the print from one year before marryat's birth

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marryat sailed for Bermuda at the beginning of 1811 in the Africa. She was an historic vessel, then thirty years old, and the smallest ship of the line to have taken part at Trafalgar. At the time when the fleets closed she was out of station to the northward. Nelson addressed one of his last signals to her, and she played a distinguished part in the action. She was now to become a flagship. On the passage out she was overcrowded, the first lieutenant was a drunkard, and the food more wretched than usual.

— Oliver Warner, Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery

USS Constitution Escaping from the British, July 1812, by American artist Julian Oliver Davidson. HMS Africa is one of the ships in pursuit, part of Sir Philip Broke's squadron.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#royal navy#hms africa#biography#age of fighting sail#1810s#oliver warner#captain marryat: a rediscovery#uss constitution

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oliver Warner, British naval historian and writer: It would be possible, indeed it has been done, to compile an anthology of passages from which a student might conclude that Marryat was a minor master of English prose. But the extracts would need to have been chosen with cunning, and it would not be possible to lift any long unbroken stretches without revealing sentence after sentence which care would have transformed.

me, running this blog:

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#reading marryat#oliver warner#british literature#english literature#literature#captain marryat a rediscovery by oliver warner#silly post#it's true that marryat can have some very clunky and amateurish writing#but i enjoy him all the same (and the light he shines on his world)

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

I found another piece of interesting gossip about Frederick Marryat's cousin Sir Edward Belcher. In Oliver Warner's book Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery he writes about the naval careers of Marryat's sons Frederick and Frank (Francis Samuel) in the 1840s:

Of the children who survived childhood, Frederick was at sea. He was a naval officer full of pranks and courage, a Cochrane type. Frank was also away, in the surveying ship Samarang. He was serving with a young cousin, Joseph, later to adorn the list of flag officers. The captain, Sir Edward Belcher, was a family connection. Frank did not get on with him, and indeed Belcher was a man who in the course of a long career inspired a great deal of active dislike.

Hmm. Why put Belcher in charge of the huge squadron in search of the Franklin expedition in the arctic? He was court-martialed and things definitely did not go smoothly, in part because of Belcher's unpopularity with his subordinates— although he could get along well with his mercurial cousin Captain Marryat.

image: H.M.S. Samarang At Chatham Jany 1847 (before letters), National Maritime Museum Greenwich

#frederick marryat#sir edward belcher#edward belcher#franklin expedition#hms samarang#1840s#royal navy#frank marryat#marryat family#oliver warner#captain marryat a rediscovery by oliver warner

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of my favorite likenesses of Captain Marryat is a portrait of mysterious provenance. The National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London credits this painting to “E. Dixon” but the artist is unknown to Marryat’s biographer Oliver Warner, who attributes it to an “Unknown Painter”, and other biographers including Marryat’s daughter don’t mention it at all. I can’t find any more information about this E. Dixon, whoever they were, but they were active in the 1830s and the NMM dates this portrait circa 1834-1839. Oliver Warner speculates “it may date from about 1841″.

Marryat’s portrait by John Simpson is the most popular image of him by far, but engravings based on the drawing of Marryat by William Behnes are also common (an engraving based on the Behnes portrait is this blog’s icon.) Dixon’s painting is more obscure, despite the warmth and humor that it radiates as Marryat strikes the pose of a man of letters.

I love the mischievous look on Marryat’s face in the Dixon portrait, and the twinkle in his eyes to match his smile. He is full of personality here and recognizable in Florence Marryat’s description of her father: “The firm, decisive mouth, and massive thoughtful forehead, were redeemed from heaviness by the humorous light that twinkled in his deep-set grey eyes, which, bright as diamonds, positively flashed out their fun... In the upper lip was a deep cleft, and in his chin as deep a dimple —a pitfall for the razor, which from the ready growth of his dark beard, he was often compelled to use twice a day.”

#captain marryat#frederick marryat#portrait#e. dixon#captain marryat a rediscovery by oliver warner#life and letters#florence marryat#also including christopher lloyd and tom pocock as 'biographers'#biography#art#chiaroscuro levels dangerously romantic

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Captain Marryat the naturalist

In the same year as his marriage [1819], Marryat became a Fellow of the Royal Society. This was due to his friend [Charles] Babbage, who was his proposer. As may be imagined, the distinction did not then approach its present grandeur, but Marryat was rightly proud of it.

— Oliver Warner, Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery

Frederick Marryat was keenly interested in the natural world. The study of the wading bird is his own artwork, now in the collection of the British Museum. Before his first command in 1820, Marryat even identified a new genus of marine gastropod molluscs by the type species Cyclostrema cancellatum, a dainty animal of the Caribbean Sea.

The surgeon and naturalist Macallan of The King’s Own has a part of his author in him, waxing poetic about ocean-going gastropods; Marryat even comments on pelagic shells in a footnote to “correct” his character’s ignorance, since the novel is set in an earlier time period.

“What shell is this, Mr. Macallan, which I have picked up? It floated on the surface of the water, by means of these air bladders, which are attached to it.”

“That shell, Willy,” replied Macallan, who, mounting his favourite hobby, immediately spouted his pompous truths, “is called, by Naturalists, the ianthina fragilis, perhaps the weakest and most delicate in its texture which exists, and yet the only one which ventures to contend with the stormy ocean. The varieties of the nautili have the same property of floating on the surface of the water, but they seldom are found many miles from land. They are only coasters, in comparison with this adventurous little navigator, which alone braves the Atlantic, and floats about in the same fathomless deep which is ranged by the devouring shark, and lashed by the stupendous whale. I have picked up these little sailors nearly one thousand miles from the land."

— Frederick Marryat, The King's Own

(In a footnote, Marryat states, “I am aware that there are two or three other pelagic shells, but, at the time of this narrative, they were not known.”)

Frederick Marryat was a childhood friend of the famous mathematician Charles Babbage, they attended the same school at one point and remained life-long friends. Babbage suggested that Marryat should also be elected to the Astronomical Society, “for which there would be some justification through his professional skill in navigation,” Tom Pocock wrote in Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer and Adventurer.

If Marryat’s later career was busy with his novels and other projects, he enjoyed educating children when he had the opportunity, as his daughter Florence described it:

His knowledge of nature was most extensive, and he might often be seen surrounded by an audience of delighted little ones, listening with open eyes and mouths to his descriptions of the wonders of the deep or the natural history of the creation.

— Florence Marryat, The Life and Letters of Captain Frederick Marryat

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#fellow of the royal society#natural history#naturalist#marryat's artwork#life and letters#biography#oliver warner#tom pocock#the king's own#macallan is said to be a big inspo for patrick o'brian's dr maturin

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Both Marryat and Conrad had, by their late thirties, amassed wonderful material for books: both felt the desire to write; both spent the latter part of their lives making an entirely new reputation. As Washington Irving wrote to Marryat later: 'You have a glorious field before you, and one in which you cannot have many competitors, as so very few unite the author to the sailor. I think the choosing of the ocean quite a new region of fiction and romance, and to my taste one of the most captivating that could be explored.'

— Oliver Warner, Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery

Sheerness as seen from the Nore, J.M.W. Turner, 1808

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#washington irving#the sea#literature#joseph conrad#joseph mallord william turner#oliver warner#biography#warner might be my favourite biographer of marryat for all the shortcomings of his book (written almost 70 years ago)#it's very dated and frustrating to me that marryat is so forgotten in the present day#the authenticity of marryat's voice is really something... despite his prejudices and imperialism etc

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Waiting room at the Admiralty’: an early portrait of Captain Marryat

This coloured engraving, depicting naval officers after the Napoleonic Wars desperate for employment or pensions, is a collaboration between Frederick Marryat and George Cruikshank, sketched by Marryat and engraved by Cruikshank in 1821 [1]. As Amy Miller notes in her book Dressed to Kill, “The years following the end of the Napoleonic Wars saw the navy down-sizing as ships were paid off and relatively young officers found themselves with a reduced income.” Patronage and connections assumed even greater importance, and the legend at the bottom of Marryat and Cruikshank’s picture is a quote from Othello: “Tis the curse of service that preferment goes by favor and affection.”

The motley inhabitants of the waiting room include a disabled adult midshipman with an empty sleeve, who looks down on an arrogant boy in a lieutenant’s uniform, a seated man at right scratching the word DAMNATION on the floor with his cane, and against the wall at left: Captain Marryat himself.

Marryat’s presence in the scene isn’t always acknowledged when this picture is used as an illustration of post-war unemployment in the Royal Navy—the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich doesn’t even credit him. However, several of Marryat’s biographers describe his part in the tableau [2]. I have used the colour print in the collection of the NMM for this post, but the British Museum has an image of superior quality on their website, even describing him against the wall as “a sturdy-looking man with folded arms, a self-portrait of Marryat.”

Dressed in civilian clothes with a high black stock (characteristic of all his portraits) and holding his hat in one hand, Marryat is not yet thirty years old, but he looks very world-weary. At this point in his life he had almost a decade of service in the navy still ahead of him, including brutal combat in the First Anglo-Burmese War. He was thirty-eight years old when he finally resigned his commission to write full-time [3].

Marryat’s Midshipman Blockhead character (another collaboration with Cruikshank in 1819-1820) has been described as self-caricature by Florence Marryat, but this is unambiguously a portrait of Marryat when he was still relatively unknown. In 1827 he was drawn by William Behnes, and later painted by John Simpson and others, but ‘Waiting room at the Admiralty’ is a glimpse at a young Captain Marryat.

[1] Alan Buster, Captain Marryat: Sea-Officer Novelist Country Squire, p. 12. I am using Buster’s date of 1821 for the initial version, although the print sold at least through the mid-1830s, with the British Museum owning a version from 1835.

[2] In addition to Alan Buster, Christopher Lloyd in Captain Marryat and the Old Navy, p. 254, Oliver Warner, Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery p. 50, and Tom Pocock includes it in the illustrations of Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer and Adventurer, also identifying Marryat in the picture.

[3] Lloyd p. 250

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#royal navy#george cruikshank#naval history#Napoleonic wars#admiralty#waiting room at the admiralty#1820s#biography#portrait#alan buster#oliver warner#christopher lloyd#tom pocock#his appearance here really echoes the behnes portrait#making me wonder if marryat often struck this rather defensive pose with folded arms#eta: even more footnotes lol

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

So why write about Captain Marryat? The answer has to be personal. Some years ago, I bought a first edition of his first novel, The Naval Officer, or Scenes and Adventures in the Life of Frank Mildmay, at a second-hand bookshop in Paris and was surprised by what I read. It was not only that his descriptions of sea and war and people were so vivid but the character of the hero was so unexpected. In 1829, when it was written, most such stories were of ordeals survived, problems solved and virtues rewarded. In this case the hero was an unpleasant young man, selfish and ruthless, yet he still triumphed in the end. I then read studies of Marryat by two historians I knew and admired. Christopher Lloyd wrote in his Captain Marryat and the Old Navy, just before the Second World War, that the author of Frank Mildmay had confirmed that the descriptive passages were, in fact, accounts of his own experiences but that the hero was certainly not a self-portrait. And yet, reading Oliver Warner’s Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery, written just after the war, it seemed that there was, indeed, a streak of ruthlessness—occasionally almost amounting to savagery and recalling Mildmay—running through Marryat’s celebrated wit and charm.

— Tom Pocock, Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#frank mildmay#tom pocock#english literature#naval history#biography#oh mildmay is most definitely marryat (but more cold-hearted and he gets to be at trafalgar)#michael sadleir got it right#quotes

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Perhaps, by this time, at least the outline of a series of portraits of Marryat will have clarified: as a boy rebellious, promising, wilful; as subordinate officer, bold to the point of recklessness; as commander, enterprising and clever; as friend and father, attractive; as husband, tried and trying—and, throughout life, energetic beyond the ordinary, gifted in diverse ways, never common-place, uncertain in temper and behaviour, and, like many other men and women, tending to overvalue the past as it receded.

— Oliver Warner, Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery

Captain Frederick Marryat (1792–1848), by E. Dixon (active c.1830–1839)

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#biography#character analysis#oliver warner#portrait#warner gets him

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

My personal knowledge of the 19th century British historian, writer, and public intellectual Thomas Carlyle is limited to an attempt to read Sartor Resartus when I was about 12, for unknown reasons. I was already deep into Victorian weirdness at that age, and somehow I heard of Carlyle and decided to read that of all books. (I don't think I got very far, Carlyle was no Charles Dickens).

But there's an anecdote about Carlyle reading Frederick Marryat that I can't stop thinking about.

When Carlyle's housemaid accidentally burned part of the manuscript he was writing, he dealt with the blow by taking time off, distracting himself by reading favourite authors. (Oliver Warner, Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery p. 192) Carlyle described these books as something like, "Captain Marryat and other trash" in his correspondence.

A modern biography of Thomas Carlyle (Moral Desperado by Simon Heffer) tells it this way:

Instead, Carlyle sought other forms of relief, still reading what he called 'the trashiest heap of novels', including some by Captain Marryat.

On the one hand it's a withering slam of Marryat's literary quality, literally calling him trash; but on the other hand, it makes him look like a very tempting kind of junk food. Even if Marryat isn't very respectable, this leading intellectual admits to indulging in his books for comfort.

I really empathise with Carlyle here—I constantly try to read Serious books about my interests, only to return to re-reading Marryat. (It doesn’t help that my phone is full of Marryat’s writing, a click away at all times).

He was a pioneer of serialised fiction published in magazines (according to Louis J. Parascandola); and his habit of intruding in his narratives with personal anecdotes and opinions can sometimes make Marryat read like cliche fanfiction. (I don't think most fanfic authors are as chatty with the reader or as melodramatic as Captain Marryat). I try to approach Marryat critically, but he’s still a guilty pleasure.

#thomas carlyle#frederick marryat#literature#19th century#british literature#reading marryat#captain marryat#oliver warner#louis j. parascandola

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Captain Marryat: 'Among the first in Dickens’s liking'

Marryat in 1841, the year he met Charles Dickens

Inevitably, when some lesser-known person is associated with Charles Dickens, that connection will be advertised as loudly as possible, since Dickens is one of the few 19th century writers and public figures who still enjoys widespread recognition in the English-speaking world. Such is the case with Frederick Marryat. A biographical blurb about Marryat will often bring up his friendship with Dickens before any of Marryat's own accomplishments are mentioned.

Despite their age difference —Marryat was 20 years older than Dickens— the two men were certainly friends. I have tried to puzzle out exactly how close they were with sometimes sketchy evidence (not helped by the fact that both men tried to burn or destroy large amounts of their correspondence.) I don’t know if the young Charles Dickens was keenly interested in meeting Captain Marryat; but Marryat was clearly aware of him. Dickens and Marryat didn’t meet each other in person until 1841, but Marryat recorded the wild popularity of Dickens’ first novel, The Pickwick Papers, as he traveled to America in 1837: “Dinner over; every body pulls out a number of ‘Pickwick’; every body talks and reads Pickwick; weather getting up squally; passengers not quite sure they won’t be seasick. [...] for many days afterwards, there were Pickwicks in plenty strewed all over the cabin, but passengers were very scarce.” (Diary in America)

As for who was influencing whom, that question is easy to answer. Marryat was first on the scene, writing in a Dickensian vein with picaresque heroes and colorful characters sketched from life before Dickens was a household name. Marryat published his nonfiction travelogue Diary in America years before Dickens’ equivalent American Notes (which was clearly inspired by Marryat.) According to the English professor Louis Parascandola, Marryat “was the first nineteenth century writer to publish his novels serially in his own magazine, the Metropolitan, an important precedent for later authors like Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray.”

The first meeting between Marryat and Dickens was arranged by their mutual friend, the artist Clarkson Stanfield. Stanfield wrote to Dickens at the beginning of 1841, “I have before told you that my friend Captain Marryat is very anxious to have ‘what all covet’, the pleasure of your acquaintance and, if therefore you have no objection to meet him, will you come and take a beef steak with me on Wednesday 27.” Dickens replied, “I shall be delighted to join you and know Marryat.”

Dickens and Marryat seem to have immediately hit it off, enjoying each other’s wit and theatrical personalities. As Marryat’s biographer Tom Pocock describes it:

The two men took to each other at once. They shared a recognition of the absurd and could present it entertainingly, sometimes mixed with pathos and even tragedy. But while Marryat re-created the world that he himself had experienced in his books, Dickens’s imagination erupted with cavalcades of characters and panoramas of widely varied scenery. Dickens did not see Marryat as a rival but recognised his skill in presenting the world of the sea and seamen, which he himself could only try to imagine. Thanking Marryat for sending him his latest novel, Dickens wrote, ‘I have been chuckling, and grinning, and clenching my fists and becoming warlike for three whole days past.’

It seems clear that Dickens and Marryat would be close friends, and Marryat himself might be a less obscure writer in the present day, except that his association with Dickens was so brief. By 1843 Marryat had sequestered himself at his country estate in Langham, Norfolk, far from the literati of London with the transportation methods of the day. Marryat’s biographies and Florence Marryat’s Life and Letters of Captain Frederick Marryat are full of entreaties from his friends begging Marryat to return to London to socialize with them and attend various events. He rarely agreed to travel, and by 1848 he was dead.

John Forster, Dickens’ friend and biographer, writes in The Life of Charles Dickens: “There is no one who approached [Dickens] on these occasions [dancing at parties with the Dickens children] excepting only our attached friend Captain Marryat, who had a frantic delight in dancing, especially with children, of whom and whose enjoyments he was as fond as it became so thoroughly good hearted a man to be. His name would have stood first among those I have been recalling, as he was among the first in Dickens’s liking; but in the autumn of 1848 he had unexpectedly passed away.”

For all the brevity of Dickens’ relationship with Marryat, they were close enough for Dickens to share some juicy gossip. In a letter to Forster, Dickens shines a rare light on Marryat’s rocky marriage. There is an anecdote about Marryat, “as if possessed by the devil,” teaching “every kind of forbidden topic and every species of forbidden word” to the overly sheltered sons of a baronet, and the “martyrdom” he suffered with his wife. Catherine (Kate) Marryat, as described by Dickens, is a violent, temperamental woman who beats her maid and has “no interest whatever in her children.”

Although Victorian propriety omitted names, as Marryat’s biographer Oliver Warner notes, “The reference might be considered vague enough— except to those who knew Marryat. To them, it must have been so clear that in later editions Forster left out all references by which Kate might identify herself.” Dickens’ 20th century biographer Walter Dexter also names the troubled couple as the Marryats.

Charles Dickens is the only person whose documented, surviving correspondence mentions the fact that Marryat spoke with a lisp. Marryat’s daughter Florence mentions no such thing, and Marryat never gave a speech impediment to his leading characters, but Dickens quips about an old fresco, “I can make out a Virgin with a mildewed Glory round her head and … what Marryat would call the arthe of a cherub.” (A few online articles about Marryat make a lot of hay over this sole mention of a lisp, and they can all thank Charles Dickens for spilling the tea.) Poor Marryat, who reminisced in a laudanum haze about all of his old friends in his final months, including “Charlie Dickens”, did he anticipate this reveal? He really should have known that Dickens had a wit that could be as mocking and caustic as his own.

Principal References (not including Marryat’s own books):

Life and Letters of Captain Frederick Marryat, Florence Marryat (1872)

Life of Charles Dickens, John Forster (1872-1874)

Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery, Oliver Warner (1953)

Puzzled Which to Choose: Conflicting Socio-Political Views in the Works of Captain Frederick Marryat, Louis J. Parascandola (1997)

Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer, Tom Pocock (2000)

#frederick marryat#charles dickens#captain marryat#victorian literature#john forster#florence marryat#1840s#literature#19th Century#history#biography#dickens quotes#the picture is from oliver warner's biography#portrait#alfred d'orsay#marryat family

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

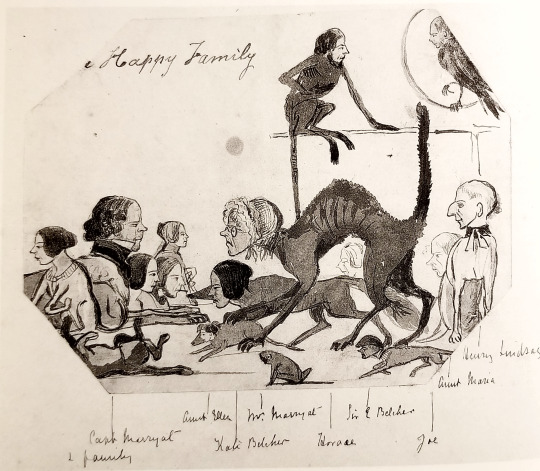

The Marryats: a "Happy Family"

The naval historian Tom Pocock's biography of Frederick Marryat, Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer and Adventurer, draws heavily on previous works (especially Oliver Warner's Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery) and does not reveal much new information. The charm is mostly in the way Pocock weaves together old material.

Perhaps the most interesting part of his book is the inclusion of this previously unpublished drawing by Frank (Samuel Francis) Marryat, one of Captain Marryat's many children. It’s an anthropomorphic caricature of the Marryat brood, and the centerpiece is Frederick Marryat vs. his wife Kate Marryat. Marryat is drawn as a dog, and his wife is an angry cat with her back arched for an obvious “fighting like cats and dogs” joke that gives Frank’s title a snarky edge.

This is hardly a flattering image of Frederick Marryat (even if he’s still sporting a magnificent cravat in his canine form), but it reveals many things — from Marryat’s appearance as a fifty-something man in the 1840s to the company he was keeping in his home.

Florence Marryat wrote of her father, “As a young man, dark crisp curls covered his head; but later in life, when, having exchanged the sword for the pen and the ploughshare, he affected a soberer and more patriarchal style of dress and manner, he wore his grey hair long, and almost down to his shoulders.” (The Life and Letters of Captain Frederick Marryat) This “long hair” is actually a fairly typical 1840s male style; I want to say that decade had some of the longest hair on men in the 19th century.

Then there is the tantalizing glimpse of the Marryat home that was published anonymously in The Cornhill Magazine in 1867 (Pocock plausibly suggests an old friend of Marryat’s, fellow Royal Navy captain and novelist Frederick Chamier, as the author). This article, “Captain Marryat at Langham,” was clearly referenced by Florence Marryat, who was only 15 years old when her father died. Visiting the Marryat home at Langham, Norfolk in the 1840s, the writer describes Captain Marryat’s appearance:

At the time I now speak of him he was fifty-two years of age; but looked considerably younger. His face was clean shaved; and his hair so long that it reached almost to his shoulders, curling in light loose locks like those of a woman. It was slightly grey. He was dressed in anything but evening costume on the present occasion, having on a short velveteen shooting-jacket and coloured trousers. I could not help smiling as I glanced at his dress —recalling to my mind what a dandy he had been as a young man.

If you have studied pictures of fashionable English women of the 1840s, their hair is often styled into bunches of curls at the temples, and Marryat indeed has this look. The figures grouped around him, labeled “Capt. Marryat + family” by Frank, are possibly his eldest daughters Blanche (Charlotte Blanche), Augusta, and Emily (Emilia.) The male figure with a cigarillo might be Captain Marryat’s son Frederick, who tragically drowned on HMS Avenger in 1847. His portrait in the National Maritime Museum depicts him with a similar hairstyle (but no beard), and his hair is dark blond. I suspect that Frank Marryat is the monkey.

Aunt Ellen and Aunt Maria are Captain Marryat’s sisters (Aunt Maria’s husband Henry Lindsay also makes it into the picture). Ellen seems to have been a favourite of her brother, from the amount of correspondence that mentions her in Life and Letters, and she helped care for Frederick in his last days (Warner, Captain Marryat). The presence of Mrs. Marryat in this picture is probably more of a wry joke to Frank than anything else. The complete deed of separation for Frederick and his wife is reproduced in Alan Buster’s Captain Marryat: Sea-Officer Novelist Country Squire and it includes very specific language that both husband and wife will leave each other alone and not interfere with each other’s lives.

I’m unclear who is supposed to be “Horace” in the drawing (the bird facing the monkey?), but that’s the name of Frederick Marryat’s youngest sibling. There was an astonishing 26-year age gap between second-born Frederick and Horace, which is a thing that can happen when your parents have fifteen children, but by the 1840s Horace would be a young adult and possibly spending time with his famous brother.

The balding man next to Henry Lindsay is labeled “Joe” —could this be Joseph Marryat II?! He appears to have a snub-nosed profile similar to Frederick. There was no love lost between Joseph and Frederick, going by the number of times hated older brothers are killed off in Marryat’s novels, but this “Happy Family” tableau obviously includes an antagonist.

Most amusing to me is the scurrying little dog wearing a cocked hat:

That’s Sir Edward Belcher, most famous for leading the huge Admiralty expedition with a squadron of ships in search of the lost Franklin expedition, and Frederick Marryat’s first cousin. Belcher was close to Frederick, and there’s an anecdote in Robert McCormick’s memoirs about meeting Belcher and Marryat together on shore, at the time Belcher was HMS Terror’s commander in 1836. (Thanks to @handfuloftime for bringing that to my attention!) The “Kate Belcher” dog may be his sister Catherine, who married Frederick Marryat’s brother Charles.

Between Frederick Marryat being depicted as a dog by his son, and his receiving the title “Great Water Dog” from a Burmese leader in the First Anglo-Burmese War (”which pleased his simple tastes,” according to Warner), I think it’s possible to conclude that his fursona was a dog that he struck others as having a dog-like nature. He was, in fact, a dog person who loved his spoiled pets. Florence Marryat describes Zinny the King Charles spaniel and Juno the Italian greyhound in Life and Letters: “two very beautiful, but utterly useless, creatures” who are allowed to scamper over Captain Marryat’s papers and flop around without much rebuke.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#sir edward belcher#marryat family#1840s#portrait#biography#frank marryat#florence marryat#tom pocock#oliver warner#alan buster#life and letters#captain marryat at langham

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marryat, eighteenth century by birth and outlook, served the Royal Navy in its great days against Napoleon, and gained honour in his profession. Later, he became a man of fashion, a London editor, the successor to Smollett as a novelist of the picaresque, and the most remarkable writer trained to the sea the English ever had until Joseph Conrad, exactly fifty years later, began to raise a lasting memorial to those with whom he had served afloat. And even Conrad lacked those experiences of warfare of which Marryat had so many.

— Oliver Warner, Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#quotes#literature#oliver warner#i have... thoughts about this passage in warner's biography#i will allow calling marryat 18th century in outlook since he was old-fashioned even in his own time#frankly his napoleonic wars experience is overemphasized#(you might blame his books for this)#as an adult he was in a leadership role during the first anglo-burmese war and it was a big deal#even his war of 1812 combat experiences were noteworthy#even in 1824 he commanded steamships in warfare#he's not strictly an age of sail figure#and he is very much of the 19th century (including his nostalgia for simpler times)

10 notes

·

View notes