#carlos garcía gual

Text

«La joven hizo la elección y, tomando el mismo hábito que él, marchaba en compañía de su esposo y se unía con él en público y asistía a los banquetes. Fue precisamente en un banquete en casa de Lisímaco donde rebatió a Teodoro el apodado el Ateo, dirigiéndole el sofisma siguiente: lo que no sería considerado un delito si lo hiciera Teodoro tampoco sería considerado un delito si lo hace Hiparquia. Teodoro no comete delito si se golpea a sí mismo, luego tampoco lo comete Hiparquia si golpea a Teodoro. Él no replicó a esta frase, pero le arrancó el vestido. Pero Hiparquia ni se alarmó ni quedó azorada como una mujer cualquiera. Sino que, cuando él le dijo; “¿Esta es la que abandonó la lanzadera en el telar?”, respondió: “Yo soy, Teodoro. ¿Es que te parece que he tomado una decisión equivocada sobre mí misma, al dedicar el tiempo que iba a gastar en el telar en mi educación?”. Esta y otras mil anécdotas se cuentan de la filósofa.»

Diógenes Laercio: Vidas de los filósofos ilustres. Alianza Editorial, págs. 324.325. Madrid, 2007.

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

@dies-irae-1

#hiparquia#crates#cinismo#filosofía griega#filosofía cínica#carlos garcía gual#feminismo#protofeminismo#teodoro el ateo#Lisímaco#vestido#lanzadera#sofisma#teo gómez otero#educación#emancipación#filósofa cínica#diógenes laercio#filosofía helenística#secta del perro#época antigua#filósofa

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plato – Phaedrus, 248c

Εἰς μὲν γὰρ τὸ αὐτὸ ὅθεν ἥκει ἡ ψυχὴ ἑκάστη οὐκ ἀφικνεῖται ἐτῶν μυρίων —οὐ γὰρ πτεροῦται πρὸ τοσούτου χρόνου— πλὴν ἡ τοῦ φιλοσοφήσαντος ἀδόλως ἢ παιδεραστήσαντος μετὰ φιλοσοφίας, αὗται δὲ τρίτῃ περιόδῳ τῇ χιλιετεῖ, ἐὰν ἕλωνται τρὶς ἐφεξῆς τὸν βίον τοῦτον, οὕτω πτερωθεῖσαι τρισχιλιοστῷ ἔτει ἀπέρχονται.

[LAT] In idem enim unde profectus est cuiusque animus annis decem millibus non revertitur. Nam alas ante hoc spatium non recuperat, praeter illius animum, qui philosophatus est sine dolo vel una cum sapientiae studio pueros amavit. Hi quidem tertio ambitu mille annorum, si ter hanc ipsam deinceps elegerint vitam, sic recuperatis alis, post tria millia annorum abeunt.

[HIS] Porque allí mismo de donde partió no vuelve alma alguna antes de diez mil años –ya que no le salen alas antes de ese tiempo–, a no ser en el caso de aquel que haya filosofado sin engaño, o haya amado a los jóvenes con filosofía. A la tercera revolución de mil años, si ha escogido tres veces seguidas este género de vida, recobra sus alas y vuela hacia los dioses en el momento en que la última, a los tres mil años, se ha realizado.

#Plato#Πλάτων#Phaedrus#Φαίδρος#saec. IV a.Ch.n.#370 a.Ch.n.#scriptum#philosophia#Graece#Socrates#Ambrosio Firmin-Didot#Carlos García Gual

1 note

·

View note

Text

Released at the beginning of the year: "Vidas de Alejandro. Dos relatos fabulosos" by Carlos García Gual

Good morning everyone, happy April and thanks for being on Alessandro III di Macedonia- your source for Alexander the Great and Hellenism.

I announce that yesterday I have started writing a booklet on Alexander the Great. It wasn’t planned because I was already reading something else for another future book, but the idea was sudden, it was born almost out of curiosity and now I want to see if I…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Javier Marías, el novelista como narrador indiscutible

Javier Marías, el novelista como narrador indiscutible

Los lectores del autor estamos acostumbrados a admirar su pericia y su astucia en la construcción de los relatos, con su espléndida prosa

Origen: Javier Marías, el novelista como narrador indiscutible

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

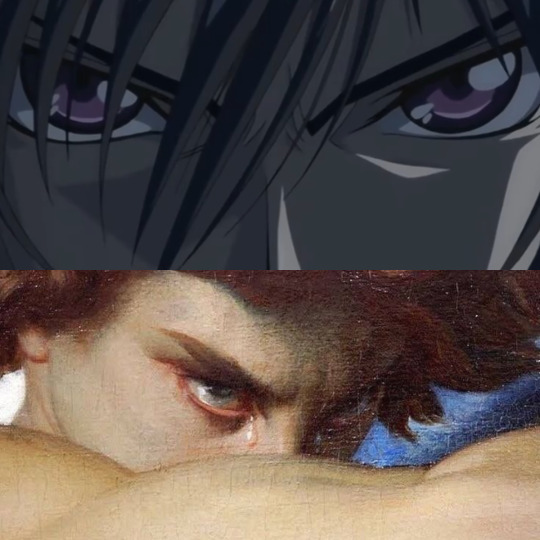

Lelouch vi Britannia, the Prometheus of Japanese animation

Today I want to upload an analysis about Lelouch that I had saved for a long time. This analysis is very special to me because it was a university essay (I wrote it in 2021 and it was a way to reconnect with this series since I didn't want to know anything about it after I was destroyed by the canon ending, I was disappointed by the alternative universe and the fandom disgusted me). I got a good grade, but it wasn't the best and it made me very sad because I worked hard and wrote that essay with a lot of love.

Anyway, the professor was terrible and I hated with every cell of my being every one of her classes and her way of teaching (some people shouldn't be teachers), so I don't care that I gave her a spoiler for one of the best endings from the television (maybe some of you will say that she didn't give me a higher grade because of the prejudice against Japanese animation and that could be, although it would be ironic because she said that it was allowed to choose anime characters as long as we explained to her everything with luxury detail and that's what I did.)

The essay exercise consisted of choosing a fictional character and explaining what archetype it was based on. What is an archetype? They are expressions of the collective unconscious or psychic elaborations that are part of the universal common language and that help in the composition of stories. In Jungian terms, Lelouch is a "Trickster" that mythologist Campbell defines as characters who violate the principles of the natural order, destroy life as we know it and restore it as a new dynamic. Lelouch also fits the Shadow archetype with respect to Suzaku, who is the Hero archetype, since Lelouch, in a way, represents everything that he represses about himself. I decided to analyze Lelouch starting from the figure of Prometheus because I felt that I was going to do a more complete analysis within the limit of extension that I had. If you notice that I'm being a little too explanatory in some parts or I don't stop to delve into others, keep in mind that it is because the essay was directed to someone who has never seen Code Geass in her life. With that said, here we go.

"It was 2006 when one of the most important Japanese animated series in the world premiered: Code Geass: Lelouch of the Rebellion. The story is about Lelouch vi Britannia, the seventeenth prince of the Holy Empire of Britannia, who at his young age was sent to Japan as a political hostage with his sister after rebuking his father, the Emperor, for failing to protect his family during an attack that left his mother dead and his sister paralyzed and blind. The series begins ten years after the tragedy when Britannia has already colonized three quarters of the world, including Japan, which is renamed Area 11. It's then that Lelouch obtains Geass, a mystical power that will allow him to dominate the will of the others, and with it he will adopt the alter ego of Zero, a masked vigilante, and will lead a rebellion in order to find answers for the murder of his mother and to give a kind world to his sister - and, in the process, destroy the empire who repudiated him. Stories about rebellions have been told many times. In his book The Rebel Man, Albert Camus observed that man rises up against the order that oppresses him when the situation has lasted so long that it is unsustainable. But the feeling of insurrection, although it is an awareness, arises from the archetypes that serve as a guide in times of crisis for societies and establish patterns for the characters in the stories we like. That being so, what archetype do we identify in Lelouch? The one from Prometheus. In this work, we will unravel Lelouch through this archetype.

The myth of Prometheus is of vast symbolic richness. Hence it lends itself to inexhaustible reinterpretations and is one of the most reworked myths. In Prometheus: myth and tragedy, Carlos García Gual traces the different materializations of Prometheus throughout the ages and declares: "all these Prometheans (...) are united by the same resistance, the same insurrection, the same voluntary suffering" (p .194). So Prometheus transcends as a benevolent rogue who disobeys the commands of Zeus in favor of humanity, emphasizing values of rebellion and progress. However, this is far from Lelouch because, while it is true that Area 11 is under the yoke of Britannia, it is not driven by a genuine desire to free the Elevens (the colonists of Area 11), but by revenge and resentment, and it disguises its selfish reasons with intentions altruistic. He does, at least initially, as, at a turning point in the second season, Lelouch realizes that his struggle extends beyond him and his sister. He also fights for the people he loves and the humanity. In this sense, we can say that Lelouch embodies the negative expression of the archetype and this, in turn, makes him similar to another mythical figure: Lucifer. Like Lelouch, Lucifer questions the supreme power of God and incites the angels to oppose him by masking his personal motivations. When the rebellion fails, he hatches a plan to corrupt man in order to get revenge on God. And the similarities don't end there. Lelouch and Lucifer were exiled and as a result they harbor a deep hatred against their creators - in God, in the Emperor of Britannia and even in Zeus we can identify the archetype of the Father. Lelouch and Satan, additionally, are manipulators and liars. Both resort to rhetoric to get what they want from others and, like evil itself, they are seductive and charismatic. We see how Lucifer deceived Eve and how Lelouch pretends to love Rolo as his brother when he is really using him. To make it more evident, in the final stretch of the series, the other characters distinguish Lelouch as "Demon Emperor" in allusion to his evil. It may seem like we are getting off topic; however, the opposite is true. Prometheus and Lucifer are more similar than it seems at first glance. In fact, Milton's Satan drinks from Prometheus and, apart from that, emerged in the Baroque, a movement that preceded Romanticism, which had an intense affinity with Prometheus. Thus, Satan, Lelouch and Prometheus have their origin in the fact that they were part of the order that they challenge and stand out for their powerful nature. Lucifer was an angel at the service of God; Prometheus was a titan with the prophetic gift who helped Zeus during the titanomachy and Lelouch was the son of the Emperor (plus he possesses mystical power and genius intellect). And, above all, all three are essentially characterized by their cunning.

Outside of his love for the human race, Prometheus is still a scoundrel who used tricks to get his way. Hesiod presents him as a challenger to the omnipotence and omnipresence of Zeus in the Theogony, highlighting his negative traits (because his attitude is contrary to the purposes of Zeus, who wants everything good). The myth of Mecona demonstrates this since Prometheus mocked the father of the gods with malicious art with the distribution of the parts of the sacrificed bull, knowing that he would choose the most appetizing one. Here Prometheus is transgressing the sacrifice between men and gods [here I open a parenthesis to tell my readers who aren't familiar with Greek mythology nor are they mythologists that the myth of Macona is the explanation and meaning that the Greeks gave to their sacrificial rituals and if we analyze it carefully, you will see that the Prometheus' trick benefited humanity since it was established that humans could eat the meat and that the burned bones would be the sacrifice for the gods; if it had been the other way around, human would have chewed the bones as if they were dogs and the gods would have eaten the meat because that was what Zeus, who "knows what is good for man", wanted (f*ck you Zeus).] Lelouch does something similar in the eighth episode of the second season. The vicereine of Area 11 decides to restore the Administrative Zone of Japan, which is a conceptual State created with the aim of returning the rights and privileges to the Elevens that were previously denied to them as colonial powers, and establishes a dialogue with Zero (Lelouch). He accepts, on behalf of the Elevens, on the condition that "Zero" be exiled and, in this way, they close the agreement. On the day of the inauguration, Lelouch, his army and the Elevens attend the ceremony dressed as Zero, forcing Britannia to let all the Zeros go and, in turn, preventing the reduction of support for his rebel group and the Elevens are subordinated to a puppet State. This situation is one of many in which Lelouch uses his cunning to benefit the people (and his own plans).

Prometheus' other trick is the theft of fire. Against the will of Zeus, Prometheus steals the fire from the gods and gives it to men. The myth of the creation of humanity tells that Prometheus decided to give man fire to elevate him to a higher category than the animal and guarantee his survival; but what does fire symbolize in this context? David Fontana answers, in The Secret Language of Symbols, that it is "a symbol of the wisdom that differentiates men from gods" (p.111). Fire is the light that allows us to see through the shadows. It's the knowledge that constitutes the central axis in the progress of civilizations. And isn't knowledge what Lucifer offers to man in Genesis? Just in case you have any doubts, the etymology reveals it: Lucifer comes from Latin and is made up of lux (light) and ferre (carry). Therefore, Lucifer means "bringer of light." Several literary critics will compare Lucifer to Prometheus, among other aspects, for this. Paolo Astorgo, in his essay "The myth of Prometheus and human knowledge", points out in relation to this: "[Prometheus] favors humanity by providing it with certain means by which it not only systematizes its activities more quickly (... ), but it creates the first ideas about technology” (para. 5). With fire, man can create weapons and instruments. For this reason, Astorgo talks about technological advancement and this brings us back to Code Geass. In the preamble to the first episode they explain to us that Britannia conquered Japan (and many other nations) because they had "Knightmares" at their disposal, which are large armed robots. No matter how hard the Japanese tried to get their land back, they were always outmatched. It's Lelouch who obtains several Knightmares and bestows them on the rebels. Thanks to its resources and tricks, the group establishes itself as a kind of organization that soon gains the sympathy of the people and the patronage of the Japanese plutocrats. Under Lelouch's leadership, the organization grows exponentially, becoming an army that rivals that of Britannia and, consequently, is capable of fighting for the freedom of Japan. Astorgo shows that men find themselves in the need to depend on the divinities because they have fire that they also use to subdue them. By giving them fire, Prometheus not only makes man rebel against the oppressive divinities, he also provides him with tools to free himself from them. Likewise, Lelouch provides the Elevens with the same power with which Britannia bends them to become independent. And, to this, Astorgo adds: "This almost dialectical relationship God-Humanity, revolves in the myth as a constant closely linked to the fact of necessity and rebellion, which is what regularizes all the acts of “deception” that Prometheus uses before Zeus. , to steal power, with the sole objective of providing freedom to humanity" (para. 13). Here one of the values that Prometheus represents comes into play: freedom.

Satan, Prometheus and Lelouch affirm themselves as rebels against the tyranny of the powerful, but humanity suffers the consequences. Adam and Eve are expelled from Paradise; Zeus takes fire from man and grants him a new evil, and in his obsession with revenge, Lelouch unintentionally drags down innocent lives and his loved ones. But while Lucifer is apathetic; Lelouch and Prometheus suffer. In his work "Prometheus: Human Existence in Greek Interpretation", Karl Kerényi says that the nature of this archetype pushes the Prometheans to think deviously, which brings misfortune for humanity and for themselves. He alleges: “in their devious (ankyios) way of thinking (…) they are caught in their own web (ankyie): (…). And all kinds of devious paths correspond to it, from lies and deceptions to the most ingenious inventions, whose precondition, however, is always representative of a lack in the way of existing of the clever" (p.45). This is the imperfection that Kerényi reiterates throughout the text. Even though they are "titanic", Lelouch and Prometheus are imperfect because they suffer and that pain humanizes them. From there, Kerényi stipulates that suffering is part of the human condition. Lelouch, in particular, is aware of the damage that his actions have on those close to him and the innocent and lives with remorse. An example is episode thirteen of the first season: the father of one of his love interests dies due to a landslide that he causes in a confrontation with Britannia. Lelouch never forgave himself. Of course, if there was an event whose guilt always tormented him, it was the massacre of the Administrative Zone of Japan, of which he was the indirect author. The sum of the tragedies in his life leads Lelouch towards the positive side of him as an archetype and, eventually, makes him make the decision to pay for his sins, but not before leaving behind him a kind world as he had proposed.

Both Prometheus and Lelouch end up succumbing to divine justice for their misdeeds. Prometheus is tied with strong chains to a rock where an eagle devours his liver and remains there for a long time until Heracles appears and shoots the animal. Lelouch's punishment, on the other hand, takes the form of the Zero Requiem; which is a plan that he develops with Suzaku, his best friend, with the aim of ending all wars and ushering in an era of peace and, in unison, answering for their crimes. After killing the Emperor and usurping the throne, Lelouch quells the insurrections against him, imposes a cruel dictatorship and establishes himself as the enemy of the world by kidnapping the leaders of the United Nations Federation (a coalition of states equivalent to the ONU), which forces the world to confront him, giving way to a war that culminates in Lelouch's victory. During the public execution of the fallen, Suzaku, dressed as Zero, appears and kills Lelouch. With his death, Lelouch accepts his punishment and takes all the hatred with him, leaving a peaceful world. Kerényi stops to analyze the tetralogy of tragedies dedicated to Prometheus by Aeschylus and observes that the cunning titan's hardships will not cease until a divinity takes charge, since Prometheus' suffering is inherent to existence. In such circumstances one could speak of a "redemption." Who replaces Prometheus is Chiron, since longed to die after being wounded by a poisoned arrow. In Lelouch's case it is Suzaku. Suzaku is a knight in the service of Britannia. Like Lelouch, he aspires to a better world, only he doesn't believe a rebellion is the key. In him we recognize, as in Heracles, the archetype of the hero. And he, like Chiron, wanted to die. However, in the end, Lelouch, who longed to live with his sister, is the one who dies and he, who wanted to die in order to purge his guilt, is the one who lives at the cost of giving up his own happiness for the good of humanity by existing. just like Zero. Thus, the two friends atone for his sins and Lelouch, who proclaimed himself as the Messiah, achieves his redemption by becoming what he preached so much (although a few know that). There is no doubt that this sacrifice for love of humanity makes us think of Jesus Christ.

Literary critics also often compare him to Prometheus and, by extension, we could compare him to Lelouch. The three are united by their closeness to men, for whom they endure a via crucis and the three are saviors of humanity. And this brings us back to Joseph Campbell's words about the definition of "hero." In simple terms, a hero is one who gives his life for something greater than himself or different from him. It is likely that there will be those who resist considering Christ as a hero. Lelouch, for his part, certainly falls within the category of tragic hero. Regarding Prometheus, García Gual attributes his heroic character to Aeschylus stating that it was his work that immortalized in tragedy for posterity the myth of an old trickster.

Either way, Lelouch is an excellent example that archetypes are rooted in the collective imagination and are binary, universal, and ahistorical in nature. Despite the enormous time gap and the difference between cultures, the archetypes represent the same values that they once had and are still capable of continuing to captivate us with wonderful narratives that have a lot to teach us."

And, well, that's how I concluded my essay. The truth is, I think I could have gone deeper since the approach has enough potential to develop a thesis, but I couldn't go on for five pages and the proffesor complained that some of my classmates decided to ignore the rule and, therefore, exceed the limit. It seems that she is one of those proffesors who doesn't want to read shit (did I mention that I despise her?). So I apologize for so little and I will allow you to hate me for this horrible English (I didn't put the quotes in their original language and then translate them, I know, I deserve you to hate me for that too).

But, if you don't hate me and you liked my work, I invite you to give me a like. If you've never thought about what archetype Lelouch is based on, give me a like. If you found the association between Jesus Christ, Satan, Prometheus and Lelouch fascinating, give me a like. If my essay made you think, give me a like. If you want to make me happy or would like my humble essay to be more widely disseminated, share it. This way I will take into account that you like me to analyze Code Geass characters through archetypes and I can bring more similar content. I would like to talk soon about a part of Joseph Campbell's hero's journey in particular that is very easy to identify in Lelouch's journey (how the hell can Lelouch be an antihero, if he has the word HERO tattooed all over his forehead?). Well, there are a lot of things I want to discuss! It's just that my life and time are not enough for me to do everything I want. Anyway, have a nice night and don't forget to eat meat to piss off Zeus.

#code geass: lelouch of the rebellion#code geass#code geass: hangyaku no lelouch#lelouch#lelouch vi britannia#lelouch lamperouge#greek mythology#prometheus#archetypes

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Los traductores de la Odisea al español

Este post, está dedicado a @rubynrut (gracias por tu fanart de Nausicaa), @iroissleepdeprived @perroulisses y @aaronofithaca05 porque nunca pensé que habría tantos fanáticos de la Odisea en español en Tumblr además de mí. Así que decidí hacer un repaso de las muchas traducciones que me he encontrado.

El listado lo saqué del libro Voces de largos ecos: Invitación a leer los clásicos de Carlos García Gual. Aunque la primera traducción al español de la Odisea fue en 1556 (titulada "La Ulixea" porque en España siempre han preferido el nombre romano de Odiseo), me quedaré con las versiones publicadas desde el siglo XX.

Luis Segalá (1910). Esta es la más difundida por todo el Internet. Segalá se tomó el trabajo de toda una vida de traducir en prosa la Ilíada, la Odisea y los Himnos Homéricos en prosa, lo que inició un nuevo interés entre los académicos castellanos por la poesía griega arcaica. Es, probablemente, la traducción más directa y literal del griego, pero personalmente creo que le hace perder la fuerza del texto. Sin embargo, Segalá debe ser el mejor que ha sabido traducir los epítetos con mayor impacto (mi favorito: Hijo de Laertes del linaje de Zeus, Odiseo fecundo en ardides) y su traducción de la Ilíada hasta ahora me parece insuperable.

Háblame, Musa, de aquel varón de multiforme ingenio que, después de destruir la sacra ciudad de Troya, anduvo peregrinando larguísimo tiempo, vió las poblaciones y conoció las costumbres de muchos hombres y padeció en su ánimo gran número de trabajos en su navegación por el ponto, en cuanto procuraba salvar su vida y la vuelta de sus compañeros a la patria.

Fernando Gutiérrez (1953). Esta es mi versión en verso favorita. Gutiérrez se basó en la traducción de Segalá y, usando versos de 16 sílabas, intentó hacer una imitación del hexámetro dactílico. El ritmo le confiere una musicalidad preciosa a la obra y la potencia que se pierde en Segalá.

Habla, Musa, de aquel hombre astuto que erró largo tiempo

después de destruir el alcázar sagrado de Troya,

del que vio tantos pueblos y de ellos su espíritu supo,

de quien tantas angustias vivió por los mares, luchando

por salvarse y por salvar a los hombres que lo acompañaban

José Luis Calvo (1976). Esta es la más interesante que me he encontrado. En esta ocasión, Calvo empezó con una invocación a la Musa en verso:

Cuéntame, Musa, la historia del hombre de muchos senderos,

que anduvo errante muy mucho después de Troya sagrada asolar;

vió muchas ciudades de hombres y conoció su talante,

y dolores sufrió sin cuento en el mar tratando

de asegurar la vida y el retorno de sus compañeros.

Pero el resto de la obra la traduce en prosa, tratando de darle una velocidad amena intentando, según él, imitar una novela española moderna (no he leído ninguna de esas. así que no tengo con que comparar), pero creo que lo consigue estupendamente.

Ello es que todos los demás, cuantos habían escapado a la amarga muerte, estaban en casa, dejando atrás la guerra y el mar. Sólo él estaba privado de regreso y esposa, y lo retenía en su cóncava cueva la ninfa Calipso, divina entre las diosas, deseando que fuera su esposo.

José Manuel Pabón (1982). Una versión en verso, rítmica en dáctilos acentuales. Esta es muy respetada por los académicos, aunque tiene demasiados arcaísmos para mi gusto y hay pasajes donde creo que el ritmo hace perder la narración, cosa que me decepciona porque la Odisea es el precedente de la novela moderna, pero cuando encaja, encaja con toda la belleza posible

Musa, dime del hábil varón que en su largo extravío,

tras haber arrasado el alcázar sagrado de Troya,

conoció las ciudades y el genio de innúmeras gentes.

Muchos males pasó por las rutas marinas luchando

por sí mismo y su vida y la vuelta al hogar de sus hombres

Carlos García Gual (2005). Esta versión en prosa la tengo pendiente, pero le tengo muchas esperanzas. Este traductor es uno de los mejores helenistas de la actualidad y ha publicado un gran número de libros estudiando la cultura griega, sobre todo la mitología griega, tanto para especializados en literatura como para el público general (si tienen la oportunidad de leer su Prometeo: mito y tragedia). Me encanta como se expresa, especialmente hablando de los poemas homéricos (vean un video con una de sus conferencias en Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C70tFKnMZ9o&pp=ygUSY2FybG9zIGdhcmNpYSBndWFs)

Háblame, Musa, del hombre de múltiples tretas que por muy largo tiempo anduvo errante, tras haber arrasado la sagrada ciudadela de Troya, y vio las ciudades y conoció el modo de pensar de numerosas gentes. Muchas penas padeció en alta mar él en su ánimo, defendiendo su vida y el regreso de sus compañeros.

Pedro C. Tapia Zuñiga (2013). Hecho para la colección de clásicos grecolatinos de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México y viene incluido con el poema original en griego. No sé por qué me gusta tanto, si tiene el doble de arcaísmos que la versión de Pabón, pero me encanta con su estilo en verso rítmico.

Del varón muy versátil cuéntame, Musa, el que mucho

vagó, después de saquear el sagrado castillo de Troya;

de muchos hombres vio las ciudades y supo su ingenio,

y él sufrió en su alma muchos dolores dentro del ponto,

aferrado a su vida y al retorno de sus compañeros.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

MIS LECTURAS DEL 2022

Va una lista de mis lecturas favoritas de este año. Quiero saber cuáles fueron las tuyas y por qué. En esta lista vienen cuentos, crónicas, autores; no me concentro en libros exclusivamente.

1-THE PENGUIN BOOK OF THE UNDEAD . Un magnífico recorrido por las apariciones de muertos y fantasmas desde la antiguedad clásica hasta el renacimiento. Las series de la editorial Penguin, muy bien investigadas y editadas, son de un gran valor literario y son, al mismo tiempo, buenas fuentes de entretenimiento, combinación esencial para despertar el interés por la lectura en tiempos donde el entretenimiento banal e inconsecuente domina nuestra cotidianidad. De la misma línea tenemos el libro de los exorcismos, de las brujas y del infierno. ¡Un gran viaje por la oscuridad!

2-SCHOPENHAUER: Parerga y Paralipómena. Me identifico mucho con mi tío Arthur por su pesimismo pero también por su manera de percibir a la naturaleza, como una fuerza ciega e irrefrenable. Y eso la convierte en un escenario de terror natural tremendo. Lo asocio vagamente con el terror cósmico de Lovecraft. Porque dentro de este escenario no existe un dios benévolo que ve por sus criaturas sino un vacío tremendo sin sentido.

Sus apuntes sobre los libros y la lectura son una delicia. Ah, y el capítulo sobre fantasmas, un tema favorito. Pero lo que más disfruto es que un filósofo de este nivel haya escrito sobre una variedad de temas que son de interés para todos, algo que los filósofos de hoy lo hacen cotidianamente. Eso, me parece, es la base de la filosofía: cuestionar, comentar nuestras cosas y preocupaciones de todos los días bajo distintos puntos de vista.

3-ODISEA, de Carlos García Gual. No se habla de "regresar a los clásicos"; ellos nunca se han ido ni nosotros nos hemos alejado de ellos. Son una presencia y garantía constante. Esta versión de García Gual logra despertar emociones y mantener vivo el interés por una obra que es parte esencial de nuestra cultura. Releer no para mantener viva esta litaratura, sino para descubrirnos de otra manera con cada nueva visita a estos textos. No conozco a nadie que habiendo leído la Odisea no se haya emocionado, y todos los que la hemos leído recordamos siempre una parte epecífica de ese viaje maravilloso.

4-LEONID ANDREYEV. Wow: un redescubrimiento. Había leído un par de cuentos en antologías y siempre me quedó la curiosidad de saber más de él. Su cuento "Lázaro" es de los 5 mejores que he leido. Le sigue "fantasmas", “abismo” y otos más. En mi nunca humilde opinión, se le debería poner más atención.

5-¡BORGES!Quien no ha leído a Borges está perdido. La editorial Lumen ha sacado una serie de entrevistas y conferencias del escritor argentino que rebozan sabiduría y sorpresa. Junto con Eco, es de mis escritores favoritos y los que más estimulan la mente. Imprescindible.

6-THE PARIS REVIEW: 1953-2012. Grandes entrevistas a escritores e intelectuales. Leer una entrevista es escuchar un monólogo entre una persona de interés que sólo quiere hablar de su obra y de sí mismo y un periodista que le importa un carajo lo que el escritor diga con tal de sacar una buena nota. Aquí el mejor ejemplo. Encontrará a su escrito favorito hablando un poco de todo. Pero lo más revelador siempre será que estos intelectuales muestran facetas y puntos de vista que parecieran no tener nada que ver con lo que escribieron. Hay muchas entrevistas: estamos ante un pequeño y conciso universo de opiniones y vivencias. Muy entretenido e ilustrativo.

7-GILCHRIST. Leyendo los cuentos de Robert Murray Gilchrist pareciera a veces como si los personajes atravesaran esta frontera, dibujada en un ambiente liminial, entre nuestro mundo y esas otras realidades alternativas, un poco como lo que ocurre en The willows, de Algernon Blackwood. Se percibe una especie de ensoñación que se desarrolla entre una densidad neblinosa, en la oscuridad de los bosques y las brumas de la mañana, pero estos ambientes terminan por absorber el destino de los personajes, los cuales, por fortuna, nunca terminan bien. Un viaje por oscuras y mágicas creencias de las islas británicas y su rico pasado imaginativo, pero con un toque sombrío y decadente que nos envuelve en esta atmósfera que no tiene salida.

8-¡TENSIÓN! Una de las características fundamentales en los cuentos de Shirley Jackson es la manera magistral de crear tensión a partir de situaciones cotidianas, inocuas. Generar conflictos desde la mecánica rítmica de los ritualitos, la rutina. De la misma manera en que otros autores descubrieron que justamente ahí se hallaba la base para construir una literatura de horror, Jackson aprovecha para descubrir -¿catalizar?- represiones, odios, rencores, complejos y otras pasiones normales y construir thrillers que rallan en el homicidio, la locura, el linchamiento. Cuentos como The people of the lake, The lottery, Trial by combat, o Charles, que trata de un niño que proyecta su personalidad conflictiva en un niño inexistente, utilizan este recurso para construir poco a poco un ambiente siniestro que progresa, algunas veces, hasta consecuencias fatales, otras, a finales abiertos que nos dejan con una gran inquietud.

Luego de leer estos textos uno se formula algunas preguntas; ¿Hasta dónde estiramos la liga de la tensión acumulada por las presiones cotidianas? ¿Cómo opera este mecanismo inconsciente que nos reprime al momento de querer o tener esta imperiosa necesidad de estallar, de liberar emociones? ¿Qué ocurre cuando estas reacciones suprimidas se canalizan de manera social y de esa manera justificamos su expresión? ¿Qué papel juegan las leyes, la moral y las costumbres aprendidas en casa y en la calle en la manera en que nos comportamos? Estas preguntas las aborda la señora Jackson en textos ya clásicos de la vida cotidiana escritos hace ya tantas décadas pero que parecen escritas hoy.

9-LIAO YIWU. Extraordinario narrador chino contemporáneo. Crónicas como El adivino y el embalsamador nos remontan a escenarios donde se entremezclan magia, tradición y política para crear una extraña ambientación que denuncia al tiempo que nos conecta con realidades suprimidas por una ideología. Vetado en China, es una voz indispensable para comprender la evolución de sociedades forzadas a creer unas cosas y dejar de creer otras, bajo estériles consignas de libertad y bienestar popular.

10-THE BRITISH LIBRARY. Una colección que recién descubrí este año y que me ha obsesionado. Muy buenas antologías de -cuento principalmente- y textos de temas varios, vistos desde el umbral del terror, la fantasía y el género weird. Así, se cuentan títulos que cubren los siguientes temas: cuentos de terror sobre la navidad, sobre las costas de Inglaterra, el terror en la tecnología, el horror de y en los mares, fantasmas y apariciones de niños, escritores poco conocidos de la época victoriana, insectos, fenómenos atmosféricos, terror en los polos, plantas asesinas, dimensiones extrañas, etc. Una gran colección que nos permite acudir a toda esta variedad de temas en cualquier momento.

11-MEDIEVAL GHOST STORIES (Andrew Joynes), SUPERNATURAL ENCOUNTERS: DEMONS AND THE RESTLESS DEAD IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND de Stephen Gordon y THE DIALOGUE ON MIRACLES de Cesáreo de Heisterbach. Tres libros para entender la percepción del fantasma y otros fenómenos paranormales en el medievo europeo. Se cuentan historias terribles y otras que rayan en lo fantástico. En muchas se aprecia el tono moralizante pero hay otras crónicas que arrastran una tradición nórdica anterior al cristianismo y en las cuales se puede ver este paganismo vivo y en constante desarrollo. Lo interesante es que no fue sino hasta finales del siglo XVIII cuando todos estos fenómenos comienzan a trasladarse de la superstición cotidiana y religiosa hacia el fenómeno literario. Ahí comienza otra historia.

12-¡EL QUIJOTE! Dicen que el Quijote es lectura obligada. Yo digo que usted debe leer lo que le salga del forro de las pelotas. A mí siempre me ha fascinado este libro y yo lo considero indispensable. El tono y el humor aquí son absolutamente necesarios para entender una faceta de la naturaleza humana que con frecuencia nos salva de serios descalabros alimentados por el odio y la intolerancia. Además, la edición actualizada de Andrés Trapiello refresca el viejo español, susituyendo arcaísmos y frases ininteligibles, logrando una lectura más fluida.

13-LA TRAGEDIA DEL DOCTOR FAUSTO, Christopher Marlowe. No sólo es la segunda obra de teatro más vista en la historia, representa nuestro último gran mito en occidente. El doctor Fausto vende su alma al diablo por sabiduría. ¿Pero es esto lo que realmente ocurre aquí? Hay algo más; esta transacción representa más bien la transición de la superstición a la ciencia, al pensamiento racional. La venta del alma es en realidad la negación de la misma y la sabiduría adquirida se fundamenta en lo experimental, lo científico. Tal vez con la intención de acercarnos más a dios para destruirlo, y ahí podría estar focalizado el conflicto del conocimiento. Y también está el tema del Círculo Mágico; en tanto que se trata de una estructura que viene de la antigüedad en este caso no se utiliza como elemento para contener o proteger, sino como un medio comunicativo. Lo que hace esta estructura es permitir el acceso no a una realidad paranormal o sobrenatural, sino acercarnos a la posibilidad de conocer facetas de la naturaleza por ahora inaccesibles y misteriosas.

14-¡CONAN! Robert E. Howard. Confieso que nunca lo leí. Vi la película con Arnold Schwarzeneger en la secundaria pero fue tiempo después que descubrí quién era su autor, y esto porque me encontraba leyendo sus cuentos de terror. No soy fan de la literatura fantástica pero Conan me parece formidable y a esto hay que agregar el manejo del lenguaje por parte del autor, capaz de crear atmósferas increíbles y generar vivas e intensas emociones. Los episodios de Conan el Cimerio atrapan, arrebatan y cuando uno termina la lectura sentimos ese típico vacío que nos deja añorando por más. Y claro, ya que estamos tocando el tema del cuento fantástico, no me voy sin recomendar a Lord Dunsany, pero de él hay que hablar en detalle en otra ocasión.

EPÍLOGO. Leer es una gran aventura. En tanto que sí hay literatura chafa y superficial, debemos inclinarnos por aquellos textos que tengan no sólo un impacto personal, sino una hechura correcta. Los clásicos bien pueden ser garantía de esto, por eso siempre se recomienda tenerlos a la mano. Y si estudiamos los textos que analizan estas obras nuestro nivel de comprensión y gozo de las mismas será mayor. Pero, como dije en el caso de Conan, también se lee para distraerse y arrebatarse, para sumergirse en esos mundos fantásticos que nos sacan momentáneamente de los rituales, rutinas y hábitos cotidianos. Y así como los médicos recomiendan una alimentación saludable basada en proteínas, carbohidratos, frutas y verduras, así con la lectura: se debe leer un poco de todo para tener una constitución y salud intelectual adecuadas.

Por lo pronto hay varios libros que aún no termino y ya se nos viene encima el 2023, así que habrá que or viendo qué títulos se van presentando y qué tendencia tomaré este año que viene.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sirenas: seducciones y metamorfosis | Carlos García Gual - YouTube

youtube

0 notes

Text

Epicureísmo, estoicismo y cinismo.

Manual, de Epicteto

Epístolas morales a Lucilio (selección), de Séneca

Doctrina estoica y defensa de Epicuro, de Francisco de Quevedo

Sobre la felicidad. Sobre la brevedad de la vida, de Séneca

La secta del perro. Vida de los filósofos cínicos, de Carlos García Gual

De la ira, de Séneca

Obras completas, de Epicuro

Epicuro, de Carlos García Gual

El epicureísmo, de Emilio Lledó

Epicuro, de Walter F. Otto

Séneca, de Emily Wilson

Consolaciones. Apocolocintosis, de Séneca

Lucrecio. La miel y la absenta, de André Comte-Sponville

Pensamiento estoico, de Eduardo Gil Bera (ed.)

El estoicismo, de Jean Brun

Cinismos. Retrato de los filósofos llamados perros, de Michel Onfray

Meditaciones (editorial Cátedra), de Marco Aurelio

Meditaciones (editorial Gredos), de Marco Aurelio

La naturaleza, de Lucrecio

Séneca y el estoicismo, de Paul Veyne

Disertaciones, de Epicteto

Séneca o el poder de la cultura, de Julio Mangas Manjarrés

1 note

·

View note

Text

Para su viaje errante Odiseo cuenta con esa polytropíe, esa versátil inteligencia con la que sabe acomodarse y enfrentar los peligros y escapar de los monstruos y de las magas con astucia y paciencia y sutil manejo de la palabra.

Carlos García Gual.

0 notes

Text

Plato – Phaedrus, 251a

ὁ δὲ ἀρτιτελής, ὁ τῶν τότε πολυθεάμων, ὅταν θεοειδὲς πρόσωπον ἴδῃ κάλλος εὖ μεμιμημένον ἤ τινα σώματος ἰδέαν, πρῶτον μὲν ἔφριξε καί τι τῶν τότε ὑπῆλθεν αὐτὸν δειμάτων, εἶτα προσορῶν ὡς θεὸν σέβεται, καὶ εἰ μὴ ἐδεδίει τὴν τῆς σφόδρα μανίας δόξαν, θύοι ἂν ὡς ἀγάλματι καὶ θεῷ τοῖς παιδικοῖς.

[LAT] Sed qui recens initiatus est sacris, quive aliquando est plurima contemplatus, quando vultum divina forma decorum videt apte ipsam pulchritudinem imitatum, vel aliquam corporis speciem, primo quidem horret metusque vetus aliquis in eum revolvitur, deinde inspiciens tanquam deum colit, ac nisi vereretur vehementis insaniae famam, sacra amatis non aliter quam dei statuae faceret.

[HIS] Sin embargo, aquel cuya iniciación es todavía reciente, el que contempló mucho de las de entonces, cuando ve un rostro de forma divina, o entrevé, en el cuerpo, una idea que imita bien a la belleza, se estremece primero, y le sobreviene algo de los temores de antaño y, después, lo venera, al mirarlo, como a un dios, y si no tuviera miedo de parecer muy enloquecido, ofrecería a su amado sacrificios como si fuera la imagen de un dios.

#Plato#Πλάτων#Phaedrus#Φαίδρος#saec. IV a.Ch.n.#370 a.Ch.n.#scriptum#philosophia#Graece#Socrates#Ambrosio Firmin-Didot#Carlos García Gual

0 notes

Text

#alessandro magno#alessandro iii di macedonia#alexander the great#prossime uscite#alessandro il grande#alessandro il macedone#alexander the conqueror#alessandro il conquistatore#alexander iii of macedon#alexander of macedon#Ediciones Siruela#Vidas de Alejandro#Pseudo Calístenes# Anónimo#Carlos García Gual#Carlos R. Méndez#Vida y hazañas de Alejandro Magno#Nacimiento#hazañas y muerte de Alejandro de Macedonia

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Video

youtube

Los banquetes de la Grecia clásica | Carlos García Gual

0 notes

Text

"Grecia para todos", de Carlos García Gual

“Grecia para todos”, de Carlos García Gual

«La historia de la antigua Grecia, su cultura y su legado

en un relato atractivo para todos los públicos.»

.

Cubierta de: ‘Grecia para todos’

Creo que Carlos García Gualdeja muy claro en el prólogo la intención del libro, al afirmarnos que estas páginas quieren ser una invitación a un viaje imaginario y sentimental a esa Grecia esencial en la Historia de Occidente, un país un tanto al margen de…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Curiosidades: Los sofistas y el discurso, la retórica

“Frente a la tradición de la poesía educadora —tanto del pueblo como de la aristocracia y no sólo en el caso de los poetas líricos recién mencionados, sino de un modo eminente en el caso de Homero y de los poetas trágicos, de un Esquilo, por ejemplo—, la sofística acentúa el poder persuasivo del lógos. Palabra, discurso, razón, razonamiento, todo ello queda contenido en el amplio campo semántico del término. «El lógos es un gran soberano que con un cuerpo pequeñísimo y totalmente invisible realiza acciones divinas...Con la fuerza de su encanto hechiza al alma, la persuade y la transporta con su seducción», dice Gorgias en un párrafo de su Elogio de Helena.”

[...]

“[...]Como señala W. Jaeger:

‘Antes de la sofística no se habla de gramática, retórica ni dialéctica. Debieron ser sus creadores. La nueva técnica es evidentemente la expresión metódica del principio de formación espiritual que se desprende de la forma del lenguaje, del discurso y del pensamiento. Esta acción pedagógica es uno de los grandes descubrimientos del espíritu humano. En estos tres dominios de su actividad adquiere por primera vez conciencia de las leyes innatas de su propia estructura.’

”

—Carlos García Gual

Obtenido de “Historia de la ética 1. de los griegos al renacimiento”, editora Victoria Camps, pp 42-43.

6 notes

·

View notes