#cennini

Text

Florentine artist Cennino Cennini: you can get vermillion from an alchemist. But watch out.

Vermillion is mercury sulfide, I wonder what happened when people realized how toxic it was?

oh no

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

PERCEZIONI - di Gianpiero Menniti

LINEA SOTTILE

Presenza non è verità.

Solitudine non è illusione.

Come nerofumo su biacca di piombo.

Solamente l'effetto di un contrasto sul confine.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

We're reading portions of Cennino Cennini's "Il libro dell'Arte" for my Renaissance art and science class (it's a 15th century painter's handbook, for those unfamiliar) and I'm completely incapable of being normal about this passage. Yes for Pentiment reasons. Listen.

#having a normal evening and crying about [checks notes] historical artist's handbooks#aka my homework#pentiment tag

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

According to the craftsman’s handbook chapter XXXVII

Il libro dell’arte by Cennino d’Andrea Cennini

who tells us there are several kinds of black colours.

First, there is a black derived from soft black stone.

It is a fat colour; not hard at heart, a stone unctioned.

Then there is a black which is made from vine twigs.

Twigs which choose to abide on the true vine

offering up their bodies at the last to be burned,

then quenched and worked up, they can live again

as twig of the vine black; not a fat, more of a lean

colour favoured alike by vinedressers and artists.

There is also the black that’s made from burnt shells.

Markers of Atlantic’s graves.

Black of scorched earth, of torched stones of peach;

twisted trees that bore strange fruit.

And then there is the black that is the source of light

from a lamp full of oil such as any thoughtful guest

waiting for bride and groom who cometh will have.

A lamp you light and place underneath—not a bushel—

but a good clean everyday dish that is fit for baking.

Now bring the little flame of the lamp up to the under-

surface of the earthenware dish (say a distance of two

or three fingers away) and the smoke which emits

from that small flame will struggle up to strike at clay.

Strike till it crowds and collects in a mess or a mass.

Now wait; wait a while please, before you sweep this

colour—now sable velvet soot—off onto any old paper

or consign it to shadows, outlines and backgrounds.

Observe: it does not need to be worked up nor ground;

it is just perfect as it is. Refill the lamp, Cennino says,

As many times as the flame burns low, refill it.

Lorna Goodison, To make various sorts of black (from ‘Supplying salt and light’, McClelland & Stewart 2013)

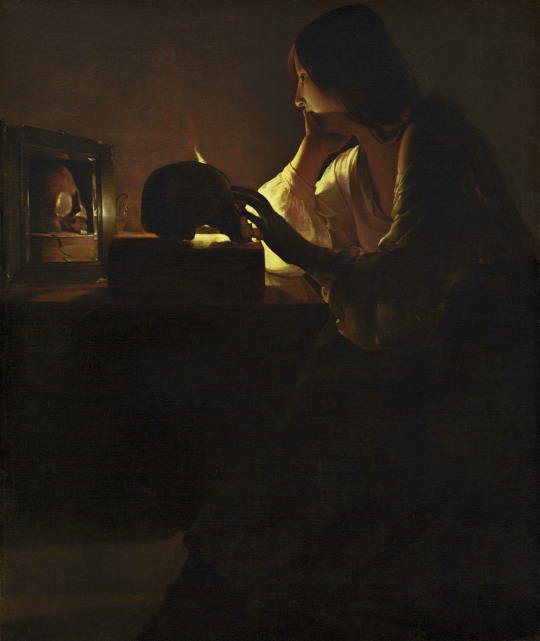

Georges de la Tour, The repentant Magdalen (oil on canvas, c.1635–1640)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les époux Arnolfini de Jan van Eyck, 1434

Une œuvre qui suscite la controverse est-ce la première peinture à l'huile ? Est-ce Jan van Eyck qui a inventé la peinture à l'huile ?La réponse est non. Jan van Eyck n'est pas le premier à appliquer de la peinture à l'huile sur un tableau. Mais on pourrait peut-être dire que c'est lui qui a mis au point la technique moderne de la peinture à l'huile qui est encore utilisée aujourd'hui. On dit que la peinture à l'huile était déjà utilisée dans l'Antiquité, et il est au moins confirmé que le moine Théophile en parle dans ses traités artistiques (vers 1100), ou qu'elle est décrite dans le Livre de l'art de Cennino Cennini XIVe siècle. À l'origine, la technique consistait à appliquer une fine couche de peinture à l'huile sur un tableau déjà peint à la détrempe (avec du blanc d'œuf comme liant). Cela ravive les couleurs et leur donne une brillance inhabituelle. Mais cela ralentit le séchage de la peinture, et lorsqu'elle est exposée au soleil pour finir de sécher, la peinture se fissure souvent et ses couleurs sont affectées. Van Eyck est obsédé par la recherche d'une huile qui sèche à l'ombre. Il finit par la trouver en mélangeant un certain vernis blanc avec de l'huile de lin il poursuit ses recherches et dissout alors dans cette solution les pigments utilisés pour la peinture à la détrempe. Et il a découvert des choses étonnantes par cette manière, les couleurs pouvaient être appliquées diluées ou épaissies, et pendant qu'elles séchaient, les nuances et les couleurs pouvaient être rectifiées, en conservant leur intégrité et l'intensité de leur éclat, leur luminosité. Ce n'est donc pas le premier tableau à utiliser la peinture à l'huile, mais il est la porte d'entrée d'une nouvelle ère de la peinture, dans laquelle la technique perfectionnée par Van Eyck est la plus importante à ce jour. C'est une nouvelle ère où l'ambition de représenter le monde avec exactitude, "la reproduction de la nature" (objet des arts plastiques jusqu'à la fin du XIXe siècle), trouve l'outil qui lui permettra de résoudre le problème technique. Profitant des vertus de la peinture à l'huile pour travailler avec réalisme et un véritable souci du détail, Van Eyck a peint cette œuvre qui sera considérée comme "la plus réaliste qui ait été faite jusqu'à cette époque". Et, comme exemple de cette minutie, observons simplement le miroir : il ne mesure que 5,5 cm, il reflète chaque scène et son cadre est décoré de 10 scènes du Chemin de Croix.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

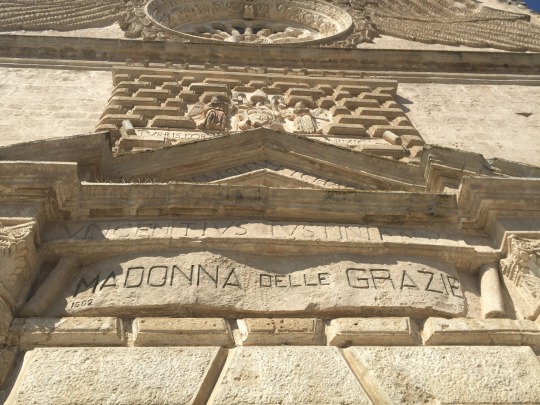

La Chiesa, edificata extra moenia su una preesistente cappella intitolata alla miracolosa Madonna delle Grazie, ed affiancata da una palazzina con giardini destinati a residenza estiva del Vescovo e dei seminaristi. Fu fatta edificare dal Vescovo Vincenzo Giustiniani (1593-1614) e svetta alta e visibile da lontano come desiderava il suo committente.

La facciata, su cui è incisa la data di costruzione 1602, è davvero originale, bizzarra ed unica nel suo genere. Ripartita in tre ordini, termina con un timpano spezzato completato dalle insegne episcopali. Sono delineate della pietra tre torri merlate poste in asse con i portali sottostanti mentre nel terzo ordine campeggia l'altorilievo della grande aquila reale ad ali spiegate con una corona regale sulla testa. La lettura dell'intera facciata evidenzia l'aquila reale che protegge il sottostante castello. La Chiesa era sotto la tutela del Vescovo la cui mitra troneggia in cima alla testa dall’aquila. Nella parte superiore la facciata è ornata da stemmi e ritratti, mentre nella parte sinistra è completata da un piccolo campanile del secolo XIX. Il particolare disegno della facciata generò il toponimo di Porta o Via dell'Aquila Grande.

La Chiesa fu ampliata e ristrutturata dal vescovo D. Cennini nel 1652, come si legge sull'arco trionfale. Gli stemmi appartengono al Vescovo Cennini, al Vescovo De Cavalieri ed alla famiglia Orsini. L’interno a navata unica con quattro cappelle laterali ha volte a vela su pilastri e soffitto piano. Tra i vari arredi ed opere d'arte che si conservano meritano particolare attenzione la pregevole tela ad olio raffigurante la Madonna delle Grazie attribuita a Giovanni Donadio di Gravina ed il bronzo del Cristo Deposto di Giuseppe Menozzi di Mantova.

Il restauro effettuato dopo i danni subiti dal terremoto del 1980 ha riportato alla luce l'arco di trionfo con i suoi capitelli ed alcuni medaglioni in pietra conferendo all'ambiente maggiore snellezza ed ampiezza.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Niente azzurrite né malachite nella volta della Sistina

Vi siete mai chiesti quali pigmenti adoperai per affrescare la volta della Cappella Sistina? Sedetevi comodi che vi racconto anche questa curiosità.

Scelsi di non usare i colori che avevano bisogno di un legante per essere adoperati. Vero è che all’inizio adoperai anche il minio ma poi lo abbandonai: non era un colore che, come lo stesso Cennini scriveva, non poteva essere preso in…

View On WordPress

#antonietta bandelloni#art#artblogger#arte#artinfluencer#bellezza#Cappella Sistina#considerazioni#english#life#madeinitaly#Michelangelo Buonarroti#Musei Vaticani#rinascimento#Roma#scultura

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Whats a medium of art you would try if you were given the materials and opportunity?

This is going to sound. Wild. But I would absolutely KILL to explore historic icon making. Like learning how to make my own gesso with rabbit glue and chalk. Using red clay to lay leaf and buff it w agate. Milling my own pigments and making my own egg tempera…….. it all sounds like a dream. There’s a translation of Cennino Cennini's Il Libro Dell'arte, (medieval text that records the processes used by 14thc. Italian artists) I’ve been meaning to track down, the nearest copy is in special collection in Boston.

But this stuff is also like. Prohibitively expensive and time consuming for me at the moment so it remains a hope for the future!!!!!

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ancora ti dirò del rilevare in muro (Cennino Cennini, Il libro dell'arte o Trattato della pittura, Milano, Longanesi, 1975).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

wow was not expecting Cennino Cennini to have a recipe for tracing paper in his libro dell'arte :^0

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Currently Fixated on the History of Pigments (for painting)

Here are some of my favorite blurbs from This Webpage:

Cobalts - HAUNTED

A family of pigments originally derived from mineral mines in Bohemia. They were named Cobalt after the word "kobolds" - the Bohemian word for spirits or ghosts, which the miners believed inhabited the pigment and caused them difficulties.

Lead-Tin Yellow - MYSTERIOUSLY DISAPPEARED

Also known as "The Old Master's Yellow" for its use by Italian Renaissance masters like Raphael. A highly stable bright opaque yellow was used from around 1250 until the mid-17th century, when its use ceased abruptly for no obvious reason. Experts believe that its formula might have been lost due to the death of its producer. Very popular with Renaissance painters, who used it in foliage along with earth pigments, Lead-Tin Yellow seems to have many of the attributes of modern Cadmium Yellow, but little was known about it until the 1940s. Since then it has enjoyed a modest recovery.

Bone White - BONES

Obsolete; it was made by burning bones to a white ash. Cennino Cennini in his Il Libro dell'Arte says 'the best bones are from the second joints and wings of fowls and capons; the older they are, the better; put them into the fire just as you find them under the table.' It was used as a ground for panels.

Carmine - BUG PAINT

Used since Antiquity, Carmine is a natural organic crimson pigment/dye made from the dried bodies of the female insect Coccus cacti (Cochineal), which inhabits the prickly-pear cactus, and also from a wingless insect living on certain species of European live oaks (Kermes). The cactus insects were first heated in ovens, then dried in the sun, to produce "silver cochineal" from which the finest pigment was made. Cochineal is still made in Mexico and India.

Lapis Lazuli - BLUE

The source of the fabulous, absolutely permanent and non-toxic natural blue pigment Ultramarine, the precious stone Lapis Lazuli is found in Central Asia, notably Afghanistan. It was employed in Ancient times as a simple ground up mineral (Lapis Lazuli or Lazuline Blue) with weak colour power. Then Persian craftsmen discovered a means of extracting the colouring agent, creating at a stroke a hugely important art material. Ultramarine arrived in Venice on Arab boats, during the Renaissance, and was named the pigment from overseas ("ultra marine"). Such was its brilliance that it rapidly attained a price that only princes and large wealthy religious organizations could afford it.

Maya Blue - LOST RECIPE

A highly resilient bright blue to greenish-blue pigment, developed by the Maya and Aztec cultures of pre-Columbian art in Mesoamerica. It is a composite of organic and inorganic compounds, notably indigo dye from the Indigofera suffruticosa plants. Originating at the beginning of the 9th century CE, it was in use as late as the 16th century in Mexico, in the paintings of the Indian Juan Gerson. It survived in Cuba until the 19th century.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is one of the coolest fucking things I own now btw. excuse me while I explode from excitement !! For those of you who don’t know, Cennini was a 15th century artist and this is a book he published on how to do basically everything a renaissance artist would need to know how to do. Chapters include things such as: “how to make tracing paper” (of which he includes 3 different methods) , “ how to make a [color]”, “how to paint a [color] in fresco”, etc. it’s so fuckjng cool dear god

#I’m gonna learn how to paint Renaissance style for real#kj.txt#art history#the craftsman’s handbook

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Da: SGUARDI SULL’ARTE LIBRO SECONDO - di Gianpiero Menniti

L’EVOLUZIONE DELLA PITTURA

Tra la fine del XIV e gli inizi del XV secolo, nel “Libro dell’Arte”, Cennino Cennini scriveva che per la pittura «conviene avere fantasia e operazione di mano, di trovare cose non vedute, cacciandosi sotto ombra di naturali, e fermarle con la mano, dando a dimostrare quello che non è, sia. E con ragione merita metterla a sedere in secondo grado alla scienza e coronarla di poesia».

Quando Cennino si cimentava nella teoria dell'arte, Giotto, la punta più avanzata della nuova pittura, era già scomparso da oltre sessant'anni, lasciando in eredità l’apertura alla terza dimensione e con essa le infinite possibilità della narrazione, le ambientazioni naturalistiche, l’espressività che connota la psicologia delle figure ritratte, la magia della luce attraverso i colori.

Ma anche qualcosa di più: il ruolo della pittura quale strumento principe di nuove forme di visione.

Detta così sembra semplice.

Eppure, la questione non può limitarsi a registrare il processo di maturazione in atto tra la fine del '200 e gli inizi del '300.La pittura rimase a lungo relegata in una manieristica, ossessiva ripetizione del modello "costantinopolitano": forse per la mancanza di riferimenti alternativi?

Forse perché le arti plastiche coglievano le opportunità del tutto tondo ovvero dell’altorilievo che colori e pennelli non erano in grado di equiparare?

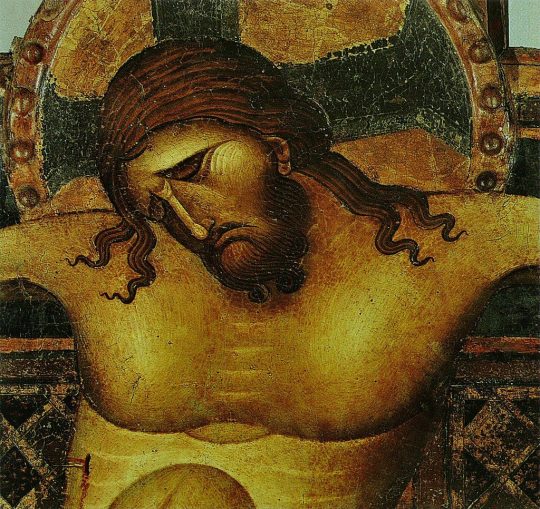

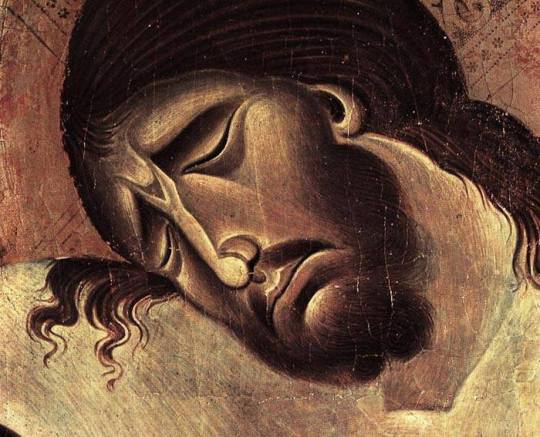

Cosa accadde ai vari Giunta Pisano, Coppo di Marcovaldo, Cimabue, Giotto e Duccio di Buoninsegna perché si destassero spalancando all’arte scenari inconsueti e fecondi?

E perché questo cambiamento, pur timido nelle sue fasi iniziali, si affermò proprio nel momento in cui i modelli bizantini, dopo la IV crociata del 1204 e la conquista di Costantinopoli, proliferavano nell'Europa occidentale?

Proviamo a capire.

Senza dubbio la pittura era più economica e più rapida da realizzare. Poi, occorre aggiungere, si affermò l’uso della “tavola” dipinta poiché poteva essere rimossa e così fungere anche da icona per le processioni.

Naturalmente, non basta.

Esisteva un riflesso culturale legato all’opera pittorica, una dimensione nella quale il dipinto è soggetto-oggetto: modificare questa concezione, diffusa e consolidata, diveniva atto di un riformismo radicale che non poteva essere accolto così facilmente.

Quindi, la pittura nuova doveva nascere in un mutato ambiente culturale, quando gradualmente le generazioni dell’urbanesimo italiano (e non solo italiano) maturarono paradigmi differenti attribuendo alla figurazione funzioni diverse dal passato.

In questa scia ci si accorse che la scultura possedeva una capacità narrativa intensa ma insufficiente a descrivere le novità della rivoluzione commerciale ed il cambiamento dei costumi sociali: sul supporto bidimensionale la descrizione del mondo e dei suoi contenuti è molto più agevole, potenzialmente più ampia, diventa soprattutto una questione tecnica prima che stilistica.

Anche le sensibilità religiose si stavano trasformando: influenzate e mediate dagli Ordini mendicanti, presenze che hanno luogo nella città, nella fitta trama di società convulse, tendono a farsi corpo di una nuova espressività, più profonda, più vicina ai sentimenti dei nuovi ceti sociali e del loro protagonismo.

Non è un caso se spicca la figura di San Francesco che diventerà uno dei soggetti preferiti della figurazione pittorica.

Allo stesso modo, il Cristo crocifisso transita dall’essere "triumphans" al diventare "patiens", mentre la Vergine in trono, che simboleggia l’Ecclesia e tiene in braccio Gesù Bambino, comincia ad assumere in volto un’espressione carica di umano sentimento e di afflato materno.

La prospettiva è ancora fragile. Eppure esiste: si tratta di una prospettiva inversa, quella che colloca il punto di fuga verso lo spettatore come per accoglierlo entro la scena rappresentata.

Tutti assieme, questi elementi costituiscono i vagiti ancora lontani dell'Umanesimo: è lo spirito che si realizza nella storia.

Giunta Pisano (1190/1200 circa - 1260 circa): Crocifisso, Basilica di San Domenico, 1250/1254, Bologna (particolare)

Coppo di Marcovaldo (1225 circa - 1276 circa): “San Francesco Bardi”, 1250/1260, Basilica di Santa Croce, Firenze

Cimabue (1240 circa - 1302): Crocifisso, 1268/71, Chiesa di San Domenico, Arezzo (particolare)

Duccio di Buoninsegna (1255 circa - 1318 o 1319): "Madonna Rucellai", 1285, Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze

Giotto (1267 - 1337):“Crocifisso”, 1290/1295, Santa Maria Novella, Firenze e "Omaggio dell'uomo semplice", 1295 /1299, ciclo di affreschi delle "Storie di San Francesco", Basilica Superiore di San Francesco, Assisi

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artists however found their own ways to paint with restraint, rather than following Alberti's actual instructions directly. Similarly, he encouraged artists to add black when modelling shapes, rather than only adding white as Cennino Cennini had advised in his c. 1390 Il Libro dell'Arte. This advice had the effect of making Italian renaissance paintings more sombre. Alberti was here perhaps following Pliny's description of the dark varnish used by Apelles.[7][8]

0 notes

Text

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Guercino

Cardinal Francesco Cennini, 1625

0 notes

Text

Passione Bibliofilia

Per i nostri lettori appassionati di bibliofilia segnaleremo periodicamente gli articoli pubblicati su tuttatoscanalibri nella rubrica “Curiosità bibliofile”:

Editio Princeps della Divina commedia, stampata a Foligno nel 1472

Le copertine

La legatura, la carta, i caratteri tipografici

La carta e alcuni tipi di carta

Articoli correlati:

Bernardo Cennini prototipografo fiorentino

Libri e…

View On WordPress

0 notes