#chaumette

Text

The difference in treatment between the Indulgents and the Cordeliers or Hébertistes

I have an opinion that will seem unpopular, no worries I am open to any criticism or to being corrected in the event of an error so do not hesitate to correct me. I have much more sympathy for the Hébertist faction, the exaggerators or the Cordeliers than that of Danton's Indulgents. Indeed if we exclude the Hebert case who is an indefensible man, mediocre in my eyes (I don't think I need to explain why) this is not the case for so many others. I mean Ronsin was a competent and honest administrator.

Despite his mysoginism (horribly reprehensible, just look at the speech he gave concerning the execution of Gouges and Manon Roland) Chaumette could be as competent as procureur syndicale de Paris and had also generous ideas (such as banning whipping in schools, equalization of funeral rites for all, protective measures for the elderly and hospitalized).

One of the most impressive cases is Momoro. Even the historian Mathiez, who nevertheless has little sympathy for the revolutionaries who were against the Committee of Public Safety in the spring of 1794, had practically nothing but praise for Momoro. He voluntarily lived in poverty and when he was tried he said he had given everything for the revolution. It was true in my eyes.

Of course I understand in a certain way the repression exercised by the Committee of Public Safety (more precisely the Convention since an arrest cannot be made without its agreement, it is not a dictatorship either) when Cordeliers wanted to launch a new insurrection against the Convention ( like Momoro for example). The fact of wanting to persecute the priests did not help, not to mention the fact that they wanted stronger repression of the enemies at the risk of making the Revolution even harsher. But when we analyze, I can understand where come frome their anger. Their hatred about religion was due to the fact that not long ago, a lot of religious fanatics infantilized the people, constantly made prohibitions against them (we must NEVER accept infantilization or loss of free will for religious reasons) and atrocious repressions without counting the their wealth that they monopolized (in terms of absurd repression there is nothing but to see the Calas affair, or that of the case of Chevalier de la Barre etc…), even if there were a lot of priest and believers weren't like that . Although the Cordeliers were wrong to respond to religious intolerance by intolerance, I can agree. The same goes for the Terror. At that time France was threatened by enemies from within and without and quite a few of their enemies carried out atrocious tortures (although rotten people like Fouché, Carrier, were not to be outdone in atrocities to the point that the Committee of Public Safety recalled them immediately). Prices were increasing because of the war, so without excusing them once again I can understand their minds when they demanded ever greater repression of the Terror (even if once again it was a serious error ,a mistake and even a fault).

Let's compare to the indulgent (or Dantonists) who are caught up in financial scandals (according to for a lot of historians like Jean Marc Schiappa). Danton moved only because of the financial scandals which were beginning to erupt and did not dare to attack head-on in this period of factional clashes, he let his friends do so. Moreover, according to certain historians like Decaux if I am not mistaken, he only came back against the Hebertists because they attacked them (and they did not only have them as enemies). He is not a clean character. Let's not talk about Fabre d'Eglantine. For Desmoulins I have an unpopular opinion of him. I find him very overrated and no matter how much I tried to appreciate his historical figure (by reading the very good biography of Leuwers or the book by Joseph Andras) I cannot. I don't think that despite the fact that he is very cultured, a man who rightly think that women must have the right of vote and even a republican before his time, he is not capable of assuming an important position unlike Saint Just or Ronsin who he made fun of. And worst of all I find him hypocritical, he who demanded clemency applauded the execution of the Hebertists following a parody of justice (yes I like the Montagnards of this period but this kind of thing should never be tolerated) . He didn't say anything when the wives of Momoro and Hebert were arrested which was very serious (afterwards I don't know well if they were arrested at the same time as Lucile Desmoulins), but he didn't realize that it was going well back in his face.

The Dantonists were irresponsible in my eyes. I completely agree that it was necessary to examine each prisoner on a case-by-case basis because there were surely a large number who had nothing to do there by creating as many commissions as possible as quickly as possible and getting down to business. job right away because prison is a horrible place, even more so for innocent people. But releasing everyone without distinction immediately would have been dangerous because there were also dangerous counter-revolutionaries or spies. I mean have they forgotten that the fall of Toulon to the English was due to betrayal? The betrayal of Dumouriez, the assassinations of some deputies, etc…

Where did this idea of making peace with foreign armies still occupying France come from when the French army was beginning to be victorious? Opposing a war of conquest I completely agree, but allowing one's own territory to be annexed is something else.

And how dangerous would it be to leave corrupt people like Danton in power. Sooner or later, he could perhaps have given in to blackmail in view of the evidence of corruption that contemporaries have today, which would have been very dangerous for France.

As a result, I never understood why the “good” indulgent ones were portrayed against the “bad” Cordeliers and Hébertists.

Whatever happens for all these factions, no matter my great admiration for revolutionaries like Le Bas, Saint Just, Couthon, the fact that I am sorry like many people that Robespierre is demonized, the fact that they allowed a parody of justice against these factions is an unforgivable fault and to have allowed the execution of Marie Françoise Goupil and Lucile Desmoulins among others to consolidate this parody of justice is unacceptable. Even if I understand their states of mind because they could not afford to lose especially in this period against these different factions and contrary to what the Thermidorians put forward, the majority of the Convention was just as guilty as them, there is no excuse for this kind of behavior.

Did Saint Just realize this when he said that the Revolution was frozen (even he spoke more about the consequences of this repression and that the revolution is weakened on this point) ? It would later fall on them and Elisabeth Le Bas was threatened with being guillotined for having been Le Bas' wife (some wanted to force her into a marriage with one of the Termidorians). If they had not allowed the fate of Goupil or Lucile Desmoulins earlier perhaps it would have been more difficult for the Thermidorians to threaten her.

For more information in the form of a movie , I invite you to see" Saint Just ou la Force des Choses" and " la Camera explore le temps Danton, la terreur et la vertue" in English sub. These are good movies about this period.

And you what do you think ?

#french revolution#Terror#georges danton#Camille Desmoulins#Ronsin#Momoro#Cordeliers#Indulgents#History#saint just#couthon#robespierre#lucile desmoulins#Hebert#Chaumette#joseph fouché#Carrier

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

15th-century Château de la Chaumette in Saint-Flour, Auvergne region of France

French vintage postcard

#saint-flour#chaumette#historic#chteau#15th-century#saint#photo#briefkaart#vintage#château de la chaumette#region#th#flour#sepia#photography#carte postale#postcard#auvergne#postkarte#france#postal#tarjeta#ansichtskarte#french#old#ephemera#de#postkaart#century#la

3 notes

·

View notes

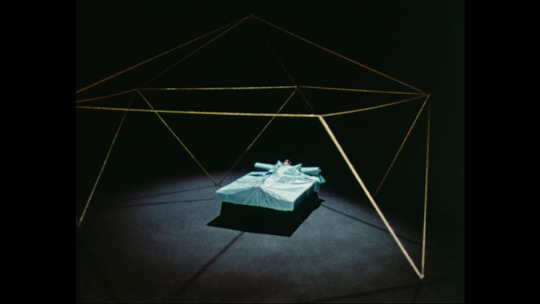

Photo

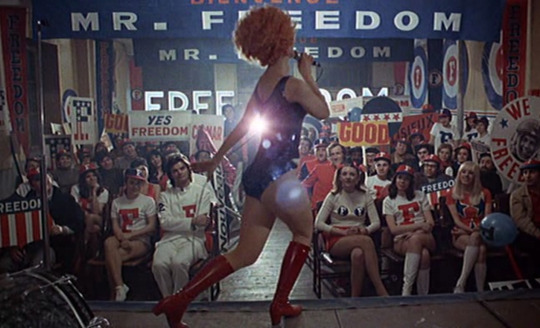

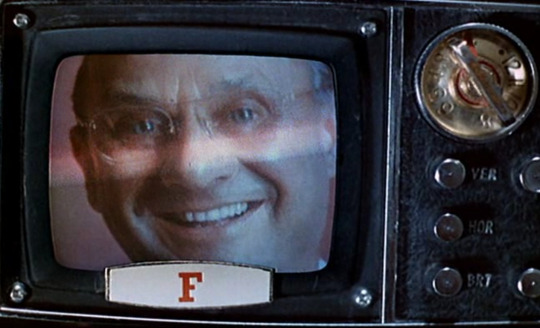

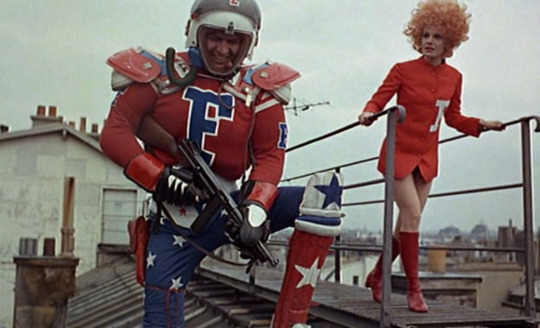

Mr. Freedom | William Klein | 1968

#William Klein#Mr. Freedom#1968#John Abbey#Delphine Seyrig#Donald Pleasence#Jean-Claude Drouot#Serge Gainsbourg#Philippe Noiret#Sami Frey#Catherine Rouvel#Monique Chaumette

105 notes

·

View notes

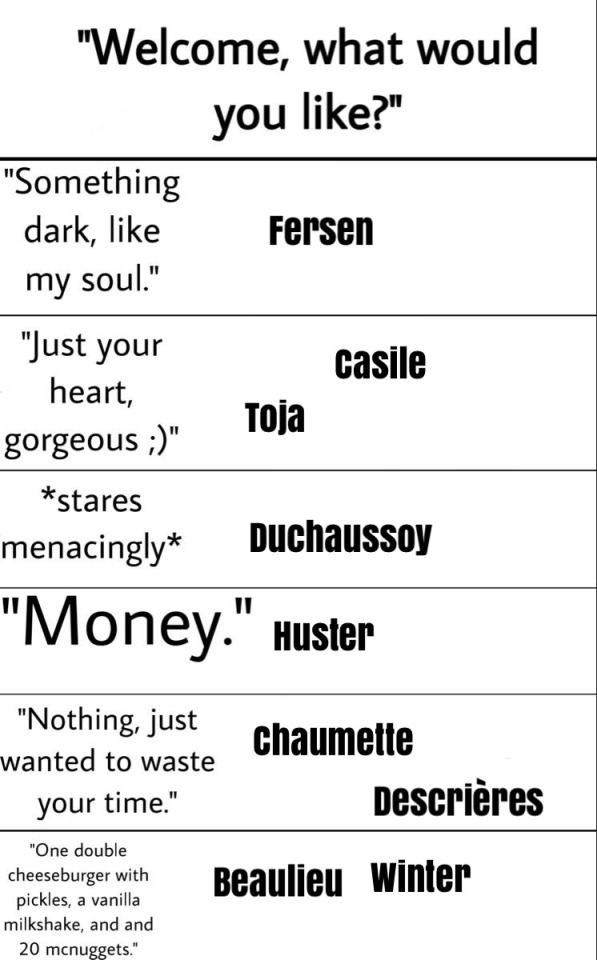

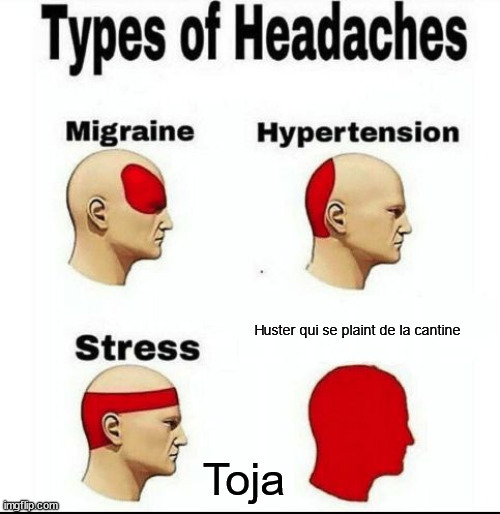

Text

Ils me font peur.

#la comédie française#jacques toja#françois chaumette#françois beaulieu#francis huster#claude winter#genevieve casile#georges descrières#michel duchaussoy#christine fersen#catherine hiegel#pierre dux#jean le poulain#jean paul roussillon

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

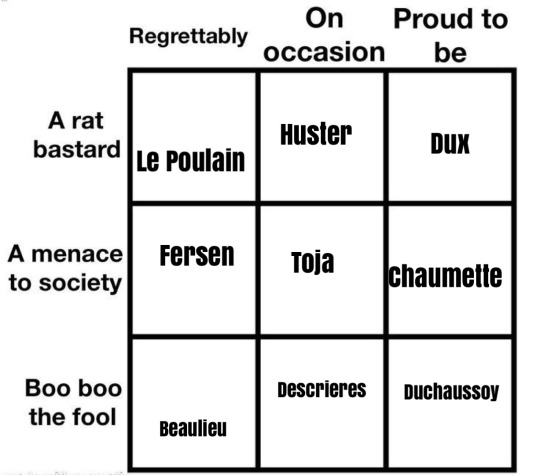

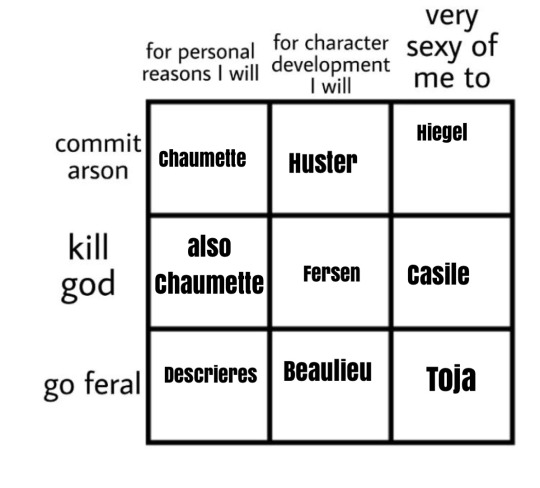

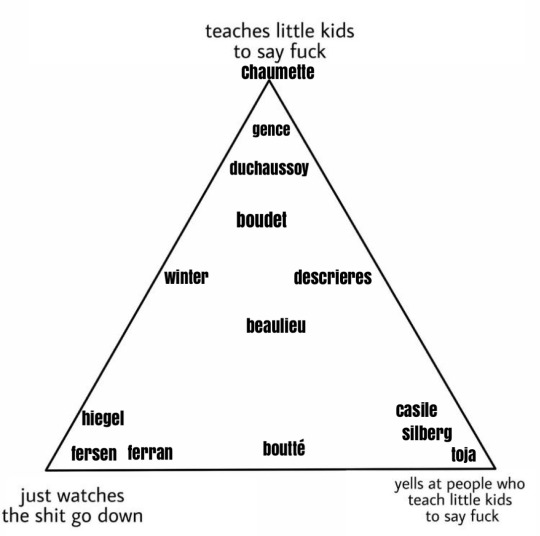

TAG YOURSELF

La Comédie-Française de 1961 à 1987 edition

#tag game#la comédie française#jacques toja#genevieve casile#françois chaumette#claude winter#georges descrières#catherine hiegel#françois beaulieu#christine fersen

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Président Faust 1974

#Président Faust#1974#Jean Kerchbron#louis pauwels#françois chaumette#françois simon#france dougnac#la qualité télé de l'époque#incroyable !!#6/10

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Joachim Bißmeier and Monique Chaumette in

Alone in Berlin (2016)

Director: Vincent Perez

#Joachim Bißmeier#Monique Chaumette#Alone in Berlin#2016#Vincent Perez#WW2#Films set during WW2#Berlin#Films based on books#Films based on true life#2010s#Films made in 2010s

3 notes

·

View notes

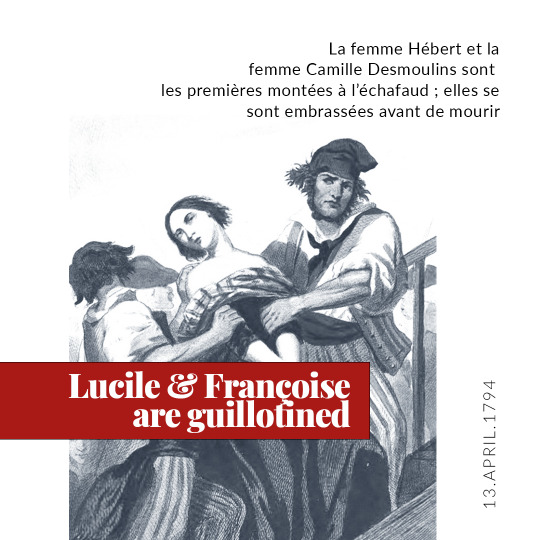

Text

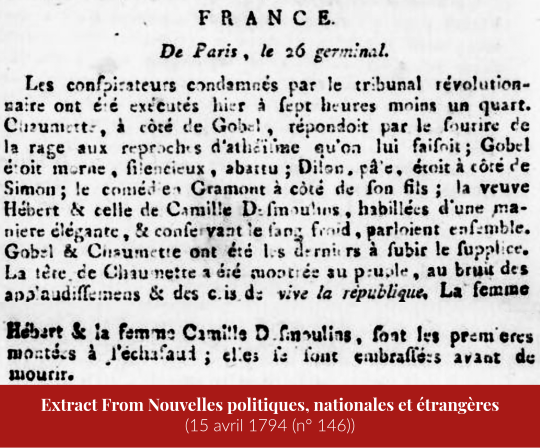

On the 13th of April 1794, exactly 230 years ago, Lucile Desmoulins and Francoise Hebert met their tragic end, following their husbands to the guillotine after enduring a brief, sham trial that wrongfully convicted them of conspiracy. Though widowed by leaders of ideologically opposed factions (Hebert was an extremist, while Desmoulins was a so-called indulgent), the two women forged a strong bond in prison. Their final moments were marked by a brief embrace before they faced their execution with dignity.

The execution of Lucile Desmoulins:

FRANCE.

From Paris, the 26th of Germinal.

The conspirators condemned by the revolutionary tribunal were executed yesterday at a quarter to seven. Chaumette, next to Gobel, responded to the accusations of atheism made against him with a rageful smile; Gobel was morose, silent, dejected; Dillon, cheerful, was beside Simon; the Count of Grammont next to his son; the widow Hébert and that of Camille Desmoulins, dressed elegantly and maintaining their composure, were talking together. Gobel & Chaumette were the last to endure the punishment. Chaumette's head was carried to the people amidst applause and cries of "Long live the republic." The wife of Hébert and the wife of Camille Desmoulins were the first to go up to the scaffold; they embraced before dying.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Non, Chaumette [Fouché], non, la mort n'est pas un sommeil éternel. Citoyens, effacez des tombeaux cette maxime gravée par des meiins sacrilèges qui jette un crêpe funèbre sur la nature, qui décourage l'innocence opprimée, et qui insulte à la mort. Gravez-y plutôt celle-ci : la mort est le commencement de l'immortalité."

"No, Chaumette [Fouché], no, death is no eternal sleep. Citizens, efface from the tombs this maxim engraved by the sacrilegious hands which throws a funeral veil on nature, which discourage the oppressed innocence, and which insults death. Engrave this instead there: death is the beginning of immortality."

-from Robespierre's speech of 8th Thermidor , english translation by rbzpr

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

We have received several complaints surrounding the closure of the SRRC. Many of them include rhetoric such as "god forbid women do anything," "support women's wrongs," and "they hate to see a girlboss winning".

As such, we would like to clarify that the reason for the club's closure was in fact due to their multipe incidents of rioting, vandalism, unlicensed militia formation, and at least one arson.

Finally we are not responsible for this "Chaumette" person, whose comments many of you have denounced. He doesn't work here. I think he's in the municipal Parisian government, but I'm not totally sure. Somebody misfiled some records the other day, so it may be a while before anyone can confirm that.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

in your opinion, what was the most significant mistake the jacobins ever made? (i tend to like them much more than other factions in the frev, but i still want to know how Problematic my Faves were)

Good question. I'm not sure which period you want to talk about regarding the Jacobins, so let's discuss the one after the fall of Louis XVI's monarchy. I will mainly encompass the Mountain faction.

Regarding tactical errors, according to some historians, including Antoine Resche, a contemporary historian who has made excellent videos on the French Revolution under the name Histony, which can be found on the Veni Vidi Sensi website, leans towards the lack of left-wing unity as one of the errors. And honestly, he's not wrong. Some might think that the elimination of Danton and the Hébertists was a turning point. But it was salvageable (I've already discussed what I thought in one of my posts). Only the Jacobins made the grave mistake of eliminating Chaumette, among others, even though he had refused to participate in an attempt to overthrow the Convention, which showed he was the most reasonable. Keeping him as the prosecutor of the Commune would have appeased some of the sans-culottes. Instead, the Convention has him arrested and executed. I understand that at that time the Convention could not afford an overthrow and was afraid Chaumette might change his mind, but by doing so, they alienated a large part of the sans-culottes. The wave of executions like Gobel or Chaumette was one of the most disastrous moves.

Another one is the non-application of the Ventôse laws, but it is true that some Montagnards blocked this, and the Marais was against these laws.

Also, being a fervent advocate of freedom of expression, there should never have been decrees holding journalists accountable. I don't particularly like Desmoulins, but executing him for his writings… Moreover, it will not prevent opinions from forming and solidifying.

Regarding moral errors: In addition to the travesties of justice I mentioned concerning the Hébertists and the Dantonists, there were other cases. When Girondin deputies were dismissed, most deputies did not want them dead, let alone imprisoned. They were only supposed to remain under house arrest. The problem is, many of them escaped and incited uprisings in the departments, which further exacerbated the already endangered Republic. Despite all I have to reproach them for, some Girondins were honorable people, notably Manon Roland and Vergniaud (even if Vergniaud had an ambiguous attitude, he still remained under house arrest) who stay in Paris. Yet they were judged, condemned to death, and executed along with other Girondins who incited or attempted uprisings and fled Paris. It wasn't even a tactical error; it was unfair.

Another very minor point concerns the Convention entirely, and this is my opinion. Why separate Marie Antoinette from her son? I understand there were royalists in Paris (the assassination of the remarkable Louis Michel Lepeletier by one of Louis XVI's former guards, among other events, will demonstrate this) who would do anything to get their hands on him as Louis XVII, which would have been dangerous. It would have been better to monitor the child's education closely given this context, but why not have strict supervision while leaving him in his mother's care, even though we know her opinions? I don't want to demonize Antoine Simon, executed in Thermidor; he wasn't a brute; he had compassion for the former queen and liked the child, but it's horrible. Being myself a proponent of reforms for jail to ensure the child remains very close to his parents, I protest against this. And the royalists seized upon it to portray an image of an inhumane Republic.

Women's rights were not respected, as I discussed in my post "Women's rights suppressed."

One of the most serious errors was the Prairial Law. When this bill presented by Couthon and later approved by the Committee of Public Safety and voted on by the Convention passed, many innocents suffered. Following the execution of the "Robespierrists," the Convention lied, saying it had not approved it, which was false.

Paradoxically, there was no internal elimination necessary at that time, notably the case of Carnot, who gave orders behind the backs of others to wage a war of conquest, which would have jeopardized the Battle of Fleurus if Saint-Just had not intervened with the order. I don't understand why he wasn't arrested; generals have been executed for less than that. This man doesn't deserve his title as the organizer of Victory, but having eliminated those who had really done the job like Saint-Just, among others, he could claim that title.

I realize I have done a critical job on the Montagnards even though I admire them, so a few lines to rehabilitate them. Most of them refused the irresponsible war of conquest advocated by the Girondins. Finally, fatigue was fatal to them. They put their best efforts into saving France, but most became ill (Couthon, Robespierre; I don't know if Billaud-Varenne was beginning to develop his dysentery or if his illness came after his deportation). Robespierre made a grave mistake by slamming the door on the Committee of Public Safety following a dispute among its members, then a few weeks later making a speech where he designated culprits without naming names (like Fouché, for example), so some wrongly believed they were the ones being designated when they weren't. Fouché and his gang played on this.

I want to say that Jean Clement Martin explained that if the Girondins are seen as victims, it's because they didn't have time to put the Montagnards on the guillotine. There were quite a few assassinations of Montagnard deputies (some think that Barbaroux manipulated Corday to kill Marat, Joseph Chalier was killed in atrocious conditions by the Girondins of Lyon, Isnard's speech). When the Jacobins acted, there was an internal civil war and an external war against the Revolution, plus a depreciated currency. And they saved it. For a while, they tried to accommodate (at least the majority of them) their adversaries. Then the gloves came off. But they remained in democracy, even in the worst moments. The Jacobins supported the abolition of slavery (not just them), and most of the major Jacobin figures fully supported the uprisings by slaves against the colonists.

Napoleon, although praised today for inheriting a better situation thanks to the efforts of his predecessors, through his dictatorial attitudes, betrayal of the Jacobins, and wars of conquest (all the wrong things), left France in a worse state with the return of the Bourbons. Revolutionaries like Marat predicted from the outset of the French Revolution that if the Girondins persisted in declaring war, even if France were victorious, there would be a military dictatorship and subsequently the return of the Bourbons.

All this leads me to think that it was the revolutionaries of the Mountain who were pragmatic and Napoleon the "idealist" in the wrong sense of the term, given his grandiosity and stupid belief (in my opinion) that he could impose hereditary dictatorship, exploit other countries without them retaliating (but that's another story).

Finally, the Jacobins in power were exhausted; they even lacked sleep hours due to their internal schedules. Before the Prairial Law was passed, there was an assassination attempt on Collot, so it was thought that the royalist danger was present. Plus, this law was disfigured by those who presented it; they thought they would only use it against people like Fouché, Carrier, Barras, Fréron, Tallien—des despicable men who dishonored France and the Revolution. It was they who later presented themselves as victims of the Jacobins when they were the worst during the Terror. Contrary to belief, heads rolled after the Terror; just look at the execution of Romme and the other Montagnards, the execution of Babeuf, the fact that anyone who demanded the constitution of 1793 could be punishable by death.

Finally, I want to say that despite my speeches, I don't believe in providential men; if France could have a sense of greatness during this period, it's thanks to the people. In Algeria, we have the slogan: "One hero only: the people."

#frev#french revolution#Roland Manon#Gironde#Montagne#jacobin#Terror#Fouché#Saint Just#Carnot#Robespierre#couthon#Romme Charles#Babeuf#Vergniaud#chaumette#camille desmoulins#marat#napoleon#georges danton#tallien

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi I saw your post asking for explanation about the context surrounding de gouges!

the technical reason for her arrest/conviction/execution was a pamphlet promoting, among other things, a potential re-installation of the monarchy. a fair bit of time had passed since, say, marat had suggested that, and the political situation had changed. due to this, at the time of de gouges' pamphlet, there was in fact a law prohibiting selling/distribution of texts advocating for a return to the monarchy (nowadays we would see this as an affront to freedom of the press, but it's important to remember that freedom of the press at that time in europe was the exception, not the rule. in fact, even at the height of what people call the 'terror', press in france was by many measures less restricted than elsewhere, where publications could be made illegal depending on how the king/emperor/etc was feeling that day).

the political context surrounding her arrest goes a bit deeper, because of her alignment with the girondin faction. it's important to note that just a few days before de gouges' arrest, a girondin woman named charlotte corday had stabbed marat to death in his house for his criticisms of the girondin faction in his newspaper. this, along with some other circumstances (such as a prominent girondin military official defecting to austria), painted everyone involved with that faction in a suspicious light. unfortunately, the fact that de gouges was a woman might've also come into account (given the potential association with corday being a girondin woman), but on the other hand a bunch of girondin men were arrested around the same time for various other reasons, so who knows.

there's also something I've found along the lines of her potentially having bought her son a military position?? not sure if or how much this contributed to her being arrested (I feel like they would've made that the bigger deal if it did) but that would also tend to discredit her.

the "anarchist beheadings" turn of phrase is imo just the poster attempting to demonstrate some rhetorical pathos. you are completely correct in your response to that part (as an irl anarchist myself it is always a bit amusing to see anarchism used as an adjective in that way, even though I know the connotation is often different lol).

you're also correct on the assertion that the jacobins had varying opinions about women's rights. and honestly, for a lot of them, it seemed to be something that was generally superseded by (for them) more pressing issues. and interestingly, a fair amount of women seemed to feel similarly and focused more of their political energy on concerns like price inflation, hoarding, and things like no-fault divorce rather than, say, being allowed to run for office. that's not to say that there were no women who wanted or pursued those things- there were many- but different people had different priorities. working-class women were very active in the revolution, and some political societies (most famously the cordeliers club) fully included women in their meetings and leadership (common cordeliers w).

obviously there were very sexist people in the government as well (such as chaumette, though I'd be hard pressed to find a single person who genuinely likes chaumette; he seems to fall in the category of 'why did he even do That Stuff. for what purpose.' along with people like hebert, collot, carrier, etc.) but that doesn't mean de gouges' arrest/execution was just because she was a Politically Involved Woman, because there were a bunch of other famous politically involved women who were not guillotined.

but yeah, in short, the lifting up of de gouges as some kind of feminist martyr is ahistorical and misinformed at best and highly classist otherwise. de gouges was not executed for having feminist views; this can be further confirmed by the fact that there were many feminist women active during the french revolution who were not executed. this doesn't negate the fact that 18c society still had very misogynistic currents, but that should be looked at in its own context, not applied as a way to try and simplify complex political circumstances surrounding de gouges.

also, in my opinion at least, the tagger you screenshotted was not engaging in good faith, as can be seen from subsequent reblogs and discussions of their additions. the modern view of the french revolution is extremely reactionary in the english-speaking world and people love to moralize and spout off about it in the tags because they watched a youtube video once in high school or something.

(sorry for the novel-length explanation, I hope this at least answered some of your questions!)

ahh thank you for the novel-length explanation!

the "prominent girondin military official defecting to austria" was dumouriez right? i've always remembered dumouriez as the dude who betrayed his own army and caused the fernig sisters to be exiled for fault that was not theirs. i didn't know he was the link between the fernigs and de gouges...!

not many people talk about the son of de gouges on this site... pierre aubry de gouges had a military position under the consulate as well, so that should be more evidence that nobody got arrested just because their family did. (that particular type of misinformation persisted for so long...)

imo even if women's grievances were not considered as feminist causes, it would be feminist to address those grievances. women running for office would cause a limited number of women to hold power, would not necessarily put bread on the table or allow participation in public life for most women.

i'm glad chaumette was not one of the frev figures fondly remembered lol.

i'm not exactly comfortable with the need for a feminist martyr and for framing the feminist cause as a revenge (i think this need precedes the ahistorical reframing of the execution of de gouges). feminism is needed because intersectional gender equality is a good thing, not because someone has died fighting for it; the cause is larger than any one biography. i'm not saying there were not martyrs in feminist history (there were many). i'm saying that we should not be learning and organising for the martyrs, but we should be learning and organising by their memory.

thank you again for this input; i did not expect someone to repond at all, it really warms my heart that you did!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Parking des Chaumettes

Christian Devillers

Paris, France, 1984

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

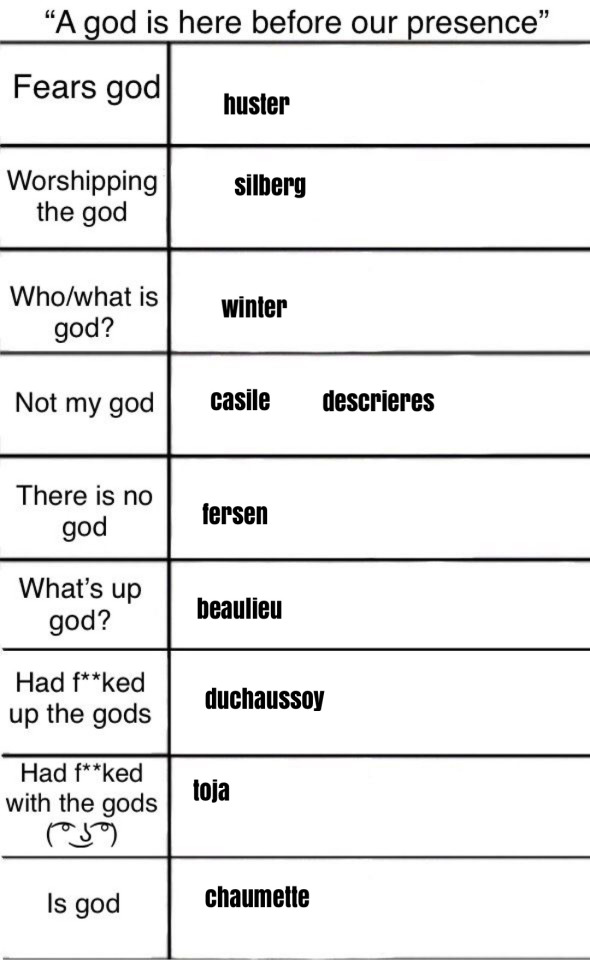

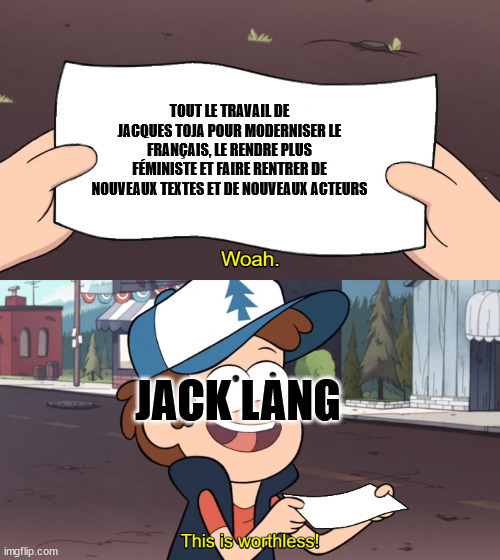

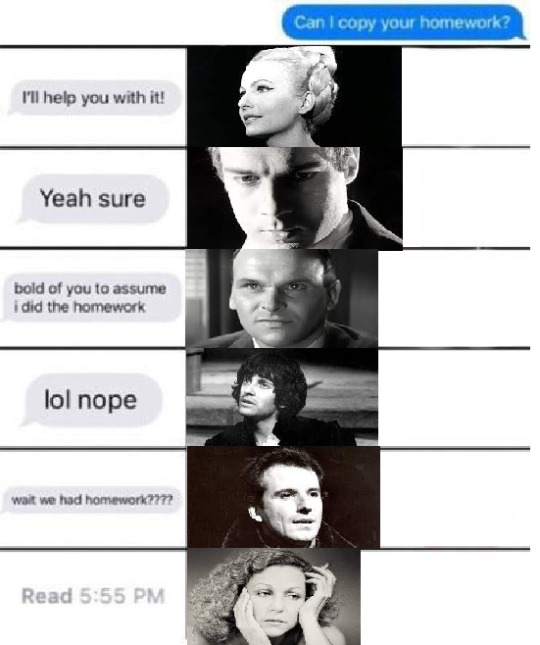

La comédie Française, 1970-1983.

#comédie française#jacques toja#françois chaumette#françois beaulieu#francis huster#nicolas silberg#genevieve casile#georges descrières#claude winter#christine fersen#catherine ferran#catherine hiegel#tania torrens#jean luc boutté#jacques charon#jean le poulain#michel duchaussoy#micheline boudet#jean pierre vincent#jack lang

9 notes

·

View notes

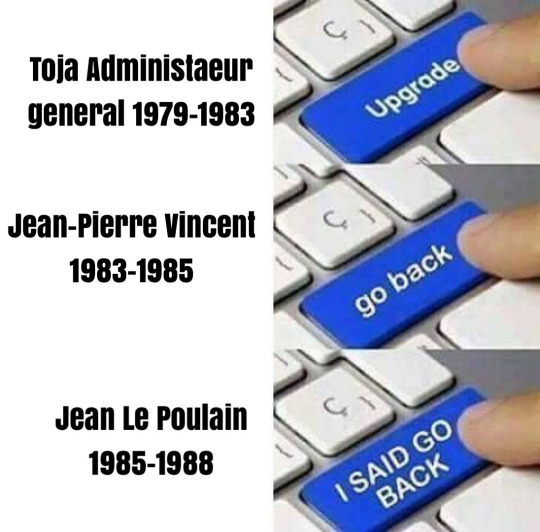

Text

Some memes about La Comédie Française de 1979 à 1983

#la comédie française#jacques toja#genevieve casile#françois chaumette#francis huster#georges descrieres#christine fersen#françois beaulieu#jean-pierre vincent#jean le poulain#jack lang

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

How was Danton responsible for the 10th of August insurrection?

According to L’école révolutionnaire des Cordeliers (published both here and as chapter three of Danton: le mythe et l’histoire (2016)) by Raymonde Monnier, ”on August 10, Danton is a key person of the situation created through the insurrection.” As evidence for this, Monnier first and foremost lifts the following decree from the section of Théâtre−Français, signed by Danton on July 30:

The section of Théâtre-Français declares […] that the fatherland being in danger, all French men are called upon to defend it; that there no longer exists what the aristocrats called passive citizens, that those who carried this unjust title are called as much to the service of the national guard as to the sections and the primary assemblies to deliberate there.

Signed: Danton, president.

Anaxagoras Chaumette, vice-president.

Momoro, secretary.

According to the memoirs of Chaumette, Danton was still in Paris on August 5. One day later, we do however find him in Arcis, signing a decree granting his mother a house, seemingly so she had something to fall back on was he to perish during the insurrection.

As for Danton’s role in the insurrection itself, he had the following to say about it during his trial held one and a half year later:

I am accused of having retired to Arcis-sur-Aube at the time when the journée of August 10 was being planned. To this accusation, I respond that I declared at that time that either the French people would be victorious or I would be dead. I ask to bring forward as witness to this fact citizen Payen. […] Pétion, leaving the Commune, came to the Cordelier Club. He told us that the tocsin would ring at midnight and that the next day must be the tomb of tyranny; he told us that the attack on the royalists was planned for the night, but that he had arranged things in such a way that everything would be done in broad daylight and would be over by noon and that victory was assured for the patriots. As for me, I only left my section after recommending to notify me would anything new happen. I stayed in my section for twelve hours straight, and returned there the next day at nine o'clock. This is the shameful rest in which I indulged, according to the report.

Danton before the tribunal on April 3 1794, as reported in Bulletin du Tribunal Révolutionnaire

I had prepared August 10 and I went to Arcis, because Danton is a good son, to spend three days, say goodbye to my mother and settle my affairs, there are witnesses to it. After that, I was very much in evidence. I didn't go to bed. Although I was an official at the Commune I went to the Cordeliers. I told Minister Clavières, who came from the Commune, that we were going to start an insurrection. After having arranged all the operations and the moment of the attack, I lay down on the bed like a soldier, with orders to warn me. I left at one o'clock and went to the Commune which had become revolutionary. I issued the death warrant against Mandat who was in possession of an order to fire on the people. The mayor was arrested and I remained at the Commune following the advice of the patriots.

Notes de Topino Lebrun, juré au Tribunal révolutionnaire de Paris, sur le procès de Danton et sur Fouquier-Tinville (1875)

On December 12 1793, Lucile Desmoulins wrote a long description over what she had experienced during the night of the insurrection four months earlier, a description where Danton gets mentioned multiple times:

After dinner [on August 9] we all went to D(anton’s). Her mother was crying, she was sad, her father looked dazed. D(anton) was resolute. [Lucile then goes out with Danton’s wife and mother-in-law for a while]. When I returned to D(anton’s), I found madame R(obert) and many others there. D(anton) was restless. I ran to madame Robert, I said to her “will they ring the tocsin?” “Yes,” she told me, ”but tonight.” I listened to everything and did not say a word. Soon I saw everyone arming themselves. C(amille), my C(amille), arrived with a gun!… O God! I sank into the ground, hid myself with both my hands and started to cry. However, not wanting to show so much weakness and say aloud to C(amille) that I did not want him to get involved in all this, I waited for a moment when I could speak to him alone, and I told him all my fears. He reassured me by telling me he would not leave D(anton’s) side. I have since found out that he exposed himself. […] No one in the street, everyone had gone home. Our patriots left. I sat down near a bed, overwhelmed, devastated, sometimes dozing off, and when I wanted to talk, I was nonsense. Madame D(anton) and R(obert) reasoned. D(anton) went to bed, he did not seem to be in a hurry. He hardly went out. Midnight was approaching. One came to search for him several times. Finally he left for the Commune. The toscin of the Cordeliers rang, it rang for a long time! Alone, bathed in tears, on my knees by the window, hidden in my handkerchief, I listened to the sound of that fatal bell. In vain they came to console me, this fatal night seemed to me to be the last! D(anton) came back. Madame Robert, who was very worried about her husband, who had gone to the Faubourg Saint-Antoine as a deputy through his section, ran to D(anton), who only gave her a very vague answer. He threw himself on his bed. One came several times to give us good and bad news. I thought I noticed that their plan was to go to the Tuileries, Sobbing, I told them I thought I was going to faint… In vain did madame Robert ask for news of her husband, no one gave her any. She thought he was marching with the faubourg. “Yes,” she said to me, “if he perishes I will not survive him! But this D(anton) who remains in his bed, he, the rallying point, if my husband perishes I will be the woman to stab him!” Her eyes were rolling. From that moment on I never left her side. What did I know what could happen? To know what she was capable of… We thus passed the night in cruel agitations. C(amille) came back at 1 o’clock, he fell asleep on my shoulder. Mde R(obert) who was next to me seemed to be preparing to learn of her husband’s death. “No,” she told me, “I can’t stay here any longer! Madame D(anton) is unbearable to me, she seems to be calm, her husband does not want to expose himself!” […]

Another diarist who mentioned Danton’s role in the insurrection was Scottish physician and travel author John Moore:

It is not to be imagiened however that [the insurrection] originated in an instantaneous resolution of the various sections of Paris: all had been arranged by a junto of men, of which Danton was supposed to be a leading member, and of whom the electors of the sections were the tools.

A journal during a residence in France, from the beginning of August to the middle of December 1792 (1793) by John Moore. Diary entry August 22 1792.

Two other contemporaries who attributed a leading role to Danton, albait much longer after the fact than Louise Robert and John Moore, are Billaud-Varennes and Garat:

After June 20, everyone was making small hassles at the castle, whose power was growing visibly: Danton arranged August 10, and the castle was struck by lightning.

Mémoires sur la révolution ou exposé de ma conduite dans les affaires et dans les fonctions publiques (1795) by Dominique-Joseph Garat

Danton, one of the condemned in Germinal, as a member of the Convention, was admirable in his courage and resources in 1792 and 1793. He had made August 10.

Note written by Billaud-Varennes in the 1830s

Finally, Villain d’Aubigny also left a more detailed description of Danton’s handling of Antoine Mandat, the commander in chief of the national guards who started disobeying orders during the insurrection, in his Principaux évènemens, pour et contre la Révolution, dont les details ont été ignorésjusqu’à présent: et prédiction de Danton au Tribunal révolutionnaire, accomplie (1794):

I go down into the courtyard, I find citizen Dufresse there, who pulls me aside and says to me: I come from Danton, who, at this moment (around two o'clock in the morning), is at the Commune, to inform you that we have just discovered an infernal conspiracy against the people in favor of the court; that this conspiracy is about to break out; that Mandat, general commander of the national guard, is at the head of this conspiracy […], that during the agitation and confusion that such a discovery had necessarily thrown into the Council, Danton, fearing everything for the people in such terrible circumstances, had hastened to transport himself, with several members of the Commune, notably Rossignol , to the general staff, where Mandat was; that he had summoned him, in the name of the people, to follow him immediately to the General Council, to give an account of his conduct; that this traitor, believing himself certain of the success of his dreadful projects, and still unaware that his treason had been discovered, had had the audacity to reply to him that he did not recognize this so-called Commune, made up of factions and rebels; that he had no orders to receive from it, and that he only held his conduct accountable to that of honest people; that Danton, throwing himself upon him and seizing him by the collar in the middle of his staff, said to him: “Traitor, it will force you to obey it, this Commune, which will save the people that you betray and against which you conspire with the tyrant... Tremble! your crime is discovered, and soon you and your infamous accomplices will receive the price!..." Danton and Rossignol take him to the General Council; he is questioned and shown the order signed and given by him to Carle to massacre the people. He turns pale!... he is forced to recognize it, to confess it... he is questioned about his connections with the tyrant and his court, about their projects, about the number of the conspirators... He declares that the Tuileries castle is filled with Swiss guards and all the supporters of the court; that everyone is armed, as are all La Fayette's friends; that the castle also contains a considerable quantity of munitions of all kinds; that, according to these confessions, Mandat had been placed in the custody of Rossignol and several other members of the Commune; but that Danton, who did not lose sight of the salvation of the people and the liberty of his fatherland for a single moment, had at that very moment given orders to all places where armed and insurgent people were to be found, to inform them of the treason plotted against them, and invite them to remain calm until daylight, in order to avoid falling into the traps that were set for them from all sides.

Within 24 hours of the successful insurrection, August 11, Danton also took serment as the new minister of justice (getting 222 out of 284 votes) which, in his biographer’s Norman Hampson’s (1978) words, ”suggests people believed he had taken a leading role.” Hampson does however also remain hesitant to state we actually know anything more concrete about Danton’s role in the insurrection — ”Nothing is known of what he actually did on the tenth, which has not stopped admirers from giving him a leading role or Mathiez to suggest he stayed out of the way.”

I’ve found an example of the first group Hampson’s is talking about in Danton: l’homme d’État. Centenaire de 1789 (1873). There, the historian Jean-François Robinet, besides bringing up the things already mentioned above, also includes the following part, but without including any sources… :

As soon as the possibility of overthrowing the throne and proclaiming the Republic had been demonstrated to him, Danton worked hard to assemble the military force which was to deliver the death blow to the monarchy. For this, he had put the Cordeliers battalion, which he had wrapped around his finger, into increasingly close contact with that of Saint-Marceau, commanded by Alexandre, and that of the Enfants-Rouges, Faubourg Saint-Antoine, commanded by Santerre. Moreover, he was their deputy, when the time arrived and through the ascendancy that he quickly gained over them, the body of the Marseille and Brest Federates, brought from the barracks of the rue Blanche in Cordeliers and placed, for the fight, under the command of Westermann, with the battalion of the Enfants-Rouges. At the same time, he chose the grievance which was to motivate the insurrection and which had to be high enough to legitimize it in the eyes of the greatest number, namely: the refusal, by the Legislative Assembly, to pronounce the forfeiture of the king which was voted on August 6. Finally, when the time for the fight came, that is to say in the night between the 9th and the 10th, "after having settled all the operations and the moment of the attack", Danton proposed in all sections, through his friends, most of whom were municipal administrators, the appointment and immediate sending to l'Hôtel de ville of commissioners with a mandate to “save public affairs”. He arranged the substitution of this new Council, or of the insurrectional group formed by all these delegates, for the old General Council, whose retreat was obtained by the intelligence he had in this assembly and by the direct action of Deforgues, one of his men, who served as master of ceremonies there.

On September 25 1873, a review of Robinet’s work was published in the journal La République Française. The reviewer declared himself scaptical in regards to Robinet’s take on Danton’s role in the insurrection, but him too without citing sources for his version of the story:

Your (Robinet) dantonist view of August 10 is nothing but a plan de pièce. If we had to stage this great day, we would proceed no differently from you: Danton summons the sections, Danton sets up the day, Danton directs the armed citizens, and we would even go so far as to have him ring the toscin of the Cordeliers with his own hand. This is the drama. But history shows something else. We see there that it was the section of Marché des Innocents which particularly and insistently requested a meeting of commissioners to draw up an address to the armies: we see there that it was as a result of the declaration of the fatherland in danger that the convocation of the sections and the appointment of the commissioners took place; we see that the commissioners gathered by the address to the armies did not find their mission up to the circumstances, and we do not see Danton in any of this. It was new commissioners (which did not include Danton's friends either, except for one, Fabre d'Eglantine), who, on the proposal of their committee, composed of Collot d'Herbois, Xavier Audouin, Chénier, Joly, Tallien and Mathieu, decided that an address for the forfeiture would be brought to the Legislative Assembly; it was Marie-Joseph Chénier (and not Danton) who wrote this address; it was the same Assembly which fixed the day for the taking up of arms, after having heard from the faubourgs Saint-Antoine and Saint-Marceau Huguenin and Lazouski (and not Danton); and if it was decided to march on the castle, it was the Brunswick manifesto which naturally gave birth to this idea in people's heads. Threatened with being decimated, the city wanted to have the king as a hostage. On the evening of August 9, it was decided in the sections that the tocsin would sound at midnight, but the commissioners who were sent to the Faubourg Saint-Antoine to agree one last time, resolved that they would only march in the morning, that 'we would form a surrectional council at Ilôtel-de-Ville, and this double resolution was taken on the proposal, not of Danton, who was not there, but of Xavier Audouin, who represented the section of La Fontaine-Grenelle. This is why Clavières came to warn the leader of the Cordeliers and why he went to bed. As for Danton signing Mandat's death warrant, we don't know what you’re talking about. The cordelier did go to Hôtel-de-Ville for a moment during the night as a substitute for the Commune prosecutor, and not as an insurgent, but he did not have a death warrant to sign. The order to take Mandate to the Abbey (there was no other) was given by the commissioners themselves when they had settled in the place of the municipality, and it was in the morning. This is what history shows. So, you say, Danton did not play any role on August 10? Yes he did, but far from seeing him as having a manifold and absorbing role, we believe on the contrary that his action that day was very limited. After having previously taken part in some of the preparatory measures, such as the distribution of cartridges, the barracking of the Marseillais at Cordeliers, etc, he hardly left his section, where he presided, on the 10th. We would even say that Danton's complete inaction at that time would in no way have surprised or offended us. He was too prominent, and even too hindered by his official functions, to fully act.

Robinet responded to the review in a long article with the title Le dix août et la symbolique positiviste(1873)

…If we take into account the decisive intelligence that Danton had in the Insurrectionary Directory, through Santerre, Alexandre, Westermann, Desmoulins and Legendre at least, and if we accept, according to the historians we have cited, that he attended its meetings, if we remember that he had a higher rank within the Cordeliers battalion, which put up such a good show at the Tuileries under Swiss fire, and where so many of his friends were; if we especially remember that before July 14, at the Jacobins, he had provoked the Fédérés present in Paris, already numbering four or five thousand, to take an oath not to leave the capital until liberty had been established and the wish of all the departments expressed on the fate of the executive power, and that the Fédérés, consequently, had, from the 17th, asked the Legistative Assembly for the suspension of the King and the indictment of Lafayette, in a petition written, it seems, by Anthoine de Metz then president of the Jacobins, and by Robespierre, it becomes difficult to deny, like La République Française does, that he had a part (and a most considerable part in our book) in the formation and the leadership of the armed force which made August 10.

But again, I’m having a hard time actually checking up any of these facts…

#danton#georges danton#i swear studying danton in detail is always just#10% things danton himself actually said/did/wrote#60% contemporaries gossiping about danton#15% historians arguing whether danton was a Corrupt Bastard Spewed up from Hell or based actually#15% other historians saying ”actually we don’t know what the f danton was up to 95% of the time so let’s just move on with it”#i’d even say he’s a harder read than robespierre#frev#french revolution#ask#but can we at least appreciate louise actually said ”i’m stabbing the bastard if my husband dies”#and lucile’s reaction was ”i better keep an eye on this girl or else she might actually do it.”

14 notes

·

View notes