#Ronsin

Text

The difference in treatment between the Indulgents and the Cordeliers or Hébertistes

I have an opinion that will seem unpopular, no worries I am open to any criticism or to being corrected in the event of an error so do not hesitate to correct me. I have much more sympathy for the Hébertist faction, the exaggerators or the Cordeliers than that of Danton's Indulgents. Indeed if we exclude the Hebert case who is an indefensible man, mediocre in my eyes (I don't think I need to explain why) this is not the case for so many others. I mean Ronsin was a competent and honest administrator.

Despite his mysoginism (horribly reprehensible, just look at the speech he gave concerning the execution of Gouges and Manon Roland) Chaumette could be as competent as procureur syndicale de Paris and had also generous ideas (such as banning whipping in schools, equalization of funeral rites for all, protective measures for the elderly and hospitalized).

One of the most impressive cases is Momoro. Even the historian Mathiez, who nevertheless has little sympathy for the revolutionaries who were against the Committee of Public Safety in the spring of 1794, had practically nothing but praise for Momoro. He voluntarily lived in poverty and when he was tried he said he had given everything for the revolution. It was true in my eyes.

Of course I understand in a certain way the repression exercised by the Committee of Public Safety (more precisely the Convention since an arrest cannot be made without its agreement, it is not a dictatorship either) when Cordeliers wanted to launch a new insurrection against the Convention ( like Momoro for example). The fact of wanting to persecute the priests did not help, not to mention the fact that they wanted stronger repression of the enemies at the risk of making the Revolution even harsher. But when we analyze, I can understand where come frome their anger. Their hatred about religion was due to the fact that not long ago, a lot of religious fanatics infantilized the people, constantly made prohibitions against them (we must NEVER accept infantilization or loss of free will for religious reasons) and atrocious repressions without counting the their wealth that they monopolized (in terms of absurd repression there is nothing but to see the Calas affair, or that of the case of Chevalier de la Barre etc…), even if there were a lot of priest and believers weren't like that . Although the Cordeliers were wrong to respond to religious intolerance by intolerance, I can agree. The same goes for the Terror. At that time France was threatened by enemies from within and without and quite a few of their enemies carried out atrocious tortures (although rotten people like Fouché, Carrier, were not to be outdone in atrocities to the point that the Committee of Public Safety recalled them immediately). Prices were increasing because of the war, so without excusing them once again I can understand their minds when they demanded ever greater repression of the Terror (even if once again it was a serious error ,a mistake and even a fault).

Let's compare to the indulgent (or Dantonists) who are caught up in financial scandals (according to for a lot of historians like Jean Marc Schiappa). Danton moved only because of the financial scandals which were beginning to erupt and did not dare to attack head-on in this period of factional clashes, he let his friends do so. Moreover, according to certain historians like Decaux if I am not mistaken, he only came back against the Hebertists because they attacked them (and they did not only have them as enemies). He is not a clean character. Let's not talk about Fabre d'Eglantine. For Desmoulins I have an unpopular opinion of him. I find him very overrated and no matter how much I tried to appreciate his historical figure (by reading the very good biography of Leuwers or the book by Joseph Andras) I cannot. I don't think that despite the fact that he is very cultured, a man who rightly think that women must have the right of vote and even a republican before his time, he is not capable of assuming an important position unlike Saint Just or Ronsin who he made fun of. And worst of all I find him hypocritical, he who demanded clemency applauded the execution of the Hebertists following a parody of justice (yes I like the Montagnards of this period but this kind of thing should never be tolerated) . He didn't say anything when the wives of Momoro and Hebert were arrested which was very serious (afterwards I don't know well if they were arrested at the same time as Lucile Desmoulins), but he didn't realize that it was going well back in his face.

The Dantonists were irresponsible in my eyes. I completely agree that it was necessary to examine each prisoner on a case-by-case basis because there were surely a large number who had nothing to do there by creating as many commissions as possible as quickly as possible and getting down to business. job right away because prison is a horrible place, even more so for innocent people. But releasing everyone without distinction immediately would have been dangerous because there were also dangerous counter-revolutionaries or spies. I mean have they forgotten that the fall of Toulon to the English was due to betrayal? The betrayal of Dumouriez, the assassinations of some deputies, etc…

Where did this idea of making peace with foreign armies still occupying France come from when the French army was beginning to be victorious? Opposing a war of conquest I completely agree, but allowing one's own territory to be annexed is something else.

And how dangerous would it be to leave corrupt people like Danton in power. Sooner or later, he could perhaps have given in to blackmail in view of the evidence of corruption that contemporaries have today, which would have been very dangerous for France.

As a result, I never understood why the “good” indulgent ones were portrayed against the “bad” Cordeliers and Hébertists.

Whatever happens for all these factions, no matter my great admiration for revolutionaries like Le Bas, Saint Just, Couthon, the fact that I am sorry like many people that Robespierre is demonized, the fact that they allowed a parody of justice against these factions is an unforgivable fault and to have allowed the execution of Marie Françoise Goupil and Lucile Desmoulins among others to consolidate this parody of justice is unacceptable. Even if I understand their states of mind because they could not afford to lose especially in this period against these different factions and contrary to what the Thermidorians put forward, the majority of the Convention was just as guilty as them, there is no excuse for this kind of behavior.

Did Saint Just realize this when he said that the Revolution was frozen (even he spoke more about the consequences of this repression and that the revolution is weakened on this point) ? It would later fall on them and Elisabeth Le Bas was threatened with being guillotined for having been Le Bas' wife (some wanted to force her into a marriage with one of the Termidorians). If they had not allowed the fate of Goupil or Lucile Desmoulins earlier perhaps it would have been more difficult for the Thermidorians to threaten her.

For more information in the form of a movie , I invite you to see" Saint Just ou la Force des Choses" and " la Camera explore le temps Danton, la terreur et la vertue" in English sub. These are good movies about this period.

And you what do you think ?

#french revolution#Terror#georges danton#Camille Desmoulins#Ronsin#Momoro#Cordeliers#Indulgents#History#saint just#couthon#robespierre#lucile desmoulins#Hebert#Chaumette#joseph fouché#Carrier

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

Give me the last words of every figure that had a role in the French revolution

(Maybe it will be to many so you can give a little of if you want)

Louis XVI — on January 22 1793, Suite du Journal de Perlet reported the folllwing about the execution that had taken place the day before:

[Louis] climbs the scaffold, the executioner cuts his hair, this operation makes him flinch a little. He turns towards the people, or rather towards the armed forces which filled the whole place, and with a very loud voice, pronounces these words:

“Frenchmen, I die innocent, it is from the top of the scaffold, and ready to appear before God, that I tell this truth; I forgive my enemies, I desire that France…”

Here he was interrupted by the noise of the drums, which covered some voices crying for mercy, he himself took off his collar and presented himself to death, his head fell, it was a quarter past ten.

Jean-Paul Marat — several people who came to witness during the trial of Charlotte Corday reported Marat’s last words to have been a cry for help to his fiancée Simonne Évrard:

Laurent Basse, courier, testifies that being on Saturday, July 15 (sic), at Citizen Marat's house, between seven and eight o'clock in the evening, busy folding newspapers, he saw the accused come, whom citoyenne Évrard and the portress refused entrance. Nevertheless, citizen Marat, who had received a letter from this woman, heard her insist and ordered her to enter, which she did. A few minutes later, on leaving, he heard a cry: ”Help me, my dear friend, help me!” (À moi, ma chere amie, à moi !). Hearing this, having entered the room where citizen Marat was, he saw blood come out of his bosom in great volumes; at this sight, himself terrified, he cried out for help, and nevertheless, for fear that the woman should make an effort to escape, he barred the door with chairs and struck her in the head with a blow; the owner came and took it out of his hands.

The president challenges the accused to state what she has to answer. I have nothing to answer, the accused says, the fact is true.

Another witness, Jeanne Maréchal, cook, submits the same facts; she adds that Marat, immediately taken from his bathtub and put in his bed, did not stir.

The accused says the fact is true.

Another witness, Marie-Barbe Aubin, portress of the house where citizen Marat lived, testifies that on the morning of July 13, she saw the accused come to the house and ask to speak to citizen Marat, who answered her that it was impossible to speak to him at the moment, attenuated the state where he had been for some time, so she gave a letter to deliver to him. In the evening she came back again, and insisted on speaking to him. Aubin and citoyenne Évrard refused to let her in; she insisted, and Marat, who had just asked who it was, having learned that it was a woman, ordered her to be let in; which happened immediately. A few moments later, she heard a cry: "Help me, my dear friend!” (À moi, ma chere amie !);she entered, and saw Marat, blood streaming from his bosom; frightened, she fell to the floor and shouted with all her might: À la garde! Au secours !

The accused says that everything the witness says is the most exact truth.

Girondins — Number 64 of Bulletin du Tribunal Criminel, written shortly after the execution, reports that, once arrived at Place de la Révolution, the Girondins sang Veillons au Salut de l’Empire together while waiting for their turn to mount the scaffold. Lehardy’s last words are reported to have been Vive la République, ”which was generally heard, thanks to the vigorous lungs nature had provided him with.”

Hébertists — On March 31, a week after the execution, Suite de Journal de Perlet reported the following anecdote, though I’ll let it be unsaid whether it should be taken seriously or not:

Here is an anecdote which can serve to make better known the eighteen conspirators whom the sword of the law has struck. On the day of their execution, several heads had already fallen when General Laumur's turn arrived. Ronsin and Vincent looked at him at the scaffold and said to Hébert: ”Without the clumsiness of this j... f... we would have succeeded.” They were alluding to the indiscretion of Laumur, who would tell anyone who would listen that the Convention had to be destroyed.

In Mémoires sur Carnot par son fils (1861), Carnot’s son also claims that, on the day of the execution, his father got stuck in the crowd witnessing the tumbrils pass on their way to the scaffold, close enough to hear Cloots say: “My friends, please do not confuse me with these rascals.”

Dantonists — the famous idea that Danton’s last words were: ”show my head to the people, it’s worth seeing” is, according to Michel Biard, at best backed by a dubious source — Souvernirs d’un sexagénaire (1833) by Antoine Vincent Arnault:

I found there all the expression of the sentiment which inspired Danton with his last words; terrible words which I could not hear, but which people repeated to each other, quivering with horror and admiration. ”Above all, don't forget,” he said to the executioner with the accent of a Gracque, ”don't forget to show my head to the people; it’s worth seeing.” At the foot of the scaffold he had said another word worthy of being recorded, because it characterizes both the circumstance which inspired it, and the man who uttered it. With his hands tied behind his back, Danton was waiting his turn at the foot of the stairs, when his friend Lacroix, whose turn had come, was brought there. As they rushed towards each other to give each other the farewell kiss, a guard, envying them this painful consolation, threw himself between them and brutally separated them. "At least you won't prevent our heads from kissing each other in the basket," Danton told him with a hideous smile.

Biard does however question how reliant Arnault really is, considering his account partly contradicts what earlier, more reliable ones, had to say about the execution. None of the authentic to somewhat autentic descriptions of the dantonist execution I’ve been able to find mention any recorded last words from Danton or his fellow convicts. That has not hindered authors and historians throughout the centuries to let their imagination run wild with the execution — look for example at how many have had Danton say something menacing about Robespierre on his way to the scaffold. Early Desmoulins biographers often have him be a sobbing mess, saying things like "Citizens! it is your preservers who are being sacrificed. It was I — I, who on July 12th called you first to arms! I first proclaimed liberty… My sole crime has been pity...” (Methley, 1915) or ”Thus, then, the first apostle of Liberty ends!” (Claretie,1876) and for Fabre there exists the claim that he hummed his song Il pleut bergère on his way to the scaffold, or muttered his biggest regret was not being able to finish his vers (verses), to which Danton replied that, within a week, he’ll have more vers (worms) than he can dream of. None of these statements do however appear to be backed by any primary sources. Finally, John Gideon Millingen, twelve years old at the time of the execution, reported in his Recollections of Republican France 1791-1801 (1848) that ”[Danton’s] execution witnessed one of those scenes of levity that seemed to render death to a jocose matter. Lacroix, who was beheaded with him, was a man of colossal stature, and, as he descended from the cart, leaning upon Danton, he observed, ”Do you see that axe, Danton? Well, even when my head is struck off I shall be taller than you!” It does however strike me as unlikely for Milligen to actually have been able to hear anything of what the condemned had to say.

Robespierrists — like with the dantonists, we have several alleged last words from more or less unreliable sources. The apocryphal memoirs of the Sansons does for example report Saint-Just’s last words to have an emotionless ”Adieu” to Robespierre, and for the latter we have a story that his last recorded words were ”Merci Monsieur,” which he said to a man for giving him a handkerchief to wipe away the blood coming out of his shattered jaw with (can you even talk under such conditions?). However, here I have again collected trustworthy descriptions, and none of them record any last words. In this instance it’s not exactly strange either, given the fact many of the condemned had been injured so badly they were more or less unconscious by the time of the execution.

Other alleged final words can be found in this post, among others Madame Roland’s ”Oh Liberty, what crimes are committed in your name” and Bailly’s ”I’m cold.” I will however doubt the authenticity of all of them until someone shows me a serious source for them (the author of the post doesn’t cite any at all). Like I wrote above, I doubt anyone actually stood near enough to hear any eventual last words.

#french revolution#frev#robespierre#danton#brissot#hébert#louis xvi#desmoulins#fabre d’eglantine#ronsin#vincent#ask#the extent actual historians have fictionalized the death of actual people is pretty f:ed up if you ask me#read biard’s la liberté ou la mort: mourir en depute and you’ll see…

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Constantin Brancusi in his studio at 11 impasse Ronsin, Paris, by Man Ray, 1930.

201 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Martha Rocher (photograph), Jean Tinguely and Yves Klein, Impasse Ronsin, Paris, 1958 [«N.B. The original photograph is entirely black and white» – Archives Yves Klein] [© Martha Rocher. © Succession Yves Klein/ADAGP, Paris / Jean Tinguely]

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

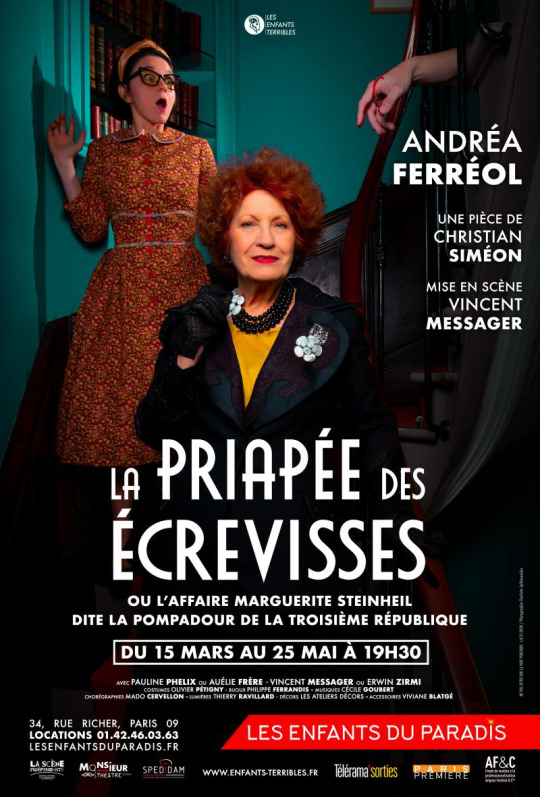

LA PRIAPÉE DES ÉCREVISSES

Avec Andréa Ferréol

Jusqu'au 25 Mai

Au Théâtre des Enfants du Paradis

Dans sa cuisine, Marguerite Steinheil s’exerce à son occupation favorite, la conception d’un plat sophistiqué “Les écrevisses à la Présidente” !…

Toujours plus raffiné, toujours plus succulent, celui-ci maintient son entraînement à l’art de se remémorer dans la métaphore, tous ces moments délicieux où la vie de ses intimes fut à portée de perversité !… Que ce soit le président Felix Faure mort dans ses bras, au cours d’une rencontre galante à l’Elysée en 1899, que ce soit son propre mari et sa mère étrangement assassinés en 1908 alors qu’elle était retrouvée elle-même ligotée et bâillonnée par son valet de chambre !

Marguerite Steinheil fut surnommée “La Sarah Bernhardt des Assises”, tellement sa fascination fut grande sur le jury et les magistrats qui l’acquittèrent en 1909 dans des applaudissements frénétiques !...

Vivante ! Marguerite Steinheil est vivante ! Elle a menti. Elle s’est vendue. Elle a trahi.

Elle a fréquenté les alcôves lambrissées du pouvoir.

Elle a surmonté le scandale le plus licencieux de la troisième République.

Elle a survécu à la très mystérieuse et très sanglante affaire de l’impasse Ronsin.

A la force du poignet, elle est devenue l’honorable, la richissime Lady Robert Brooke Campbell Scarlett-Abinger, baronne et pairesse d’Angleterre.

Alors elle cuisine.

Obstinément elle cuisine.

Avec jubilation. Avec hargne.

Juste pour nuire encore un peu.

N’hésitez plus, vous pourrez vous aussi dire, J’ai un ticket :

0 notes

Text

Avant le décalage puis le décollage de notre avion pour un port d’Italie, sous influence Austro-Hongroise, un petit détour par le centre Pompidou et son exposition du côté du sculpteur Brancusi. L’atelier de l’impasse Ronsin y est reconstitué pour partie en particulier ses outils et son établi.

C’était un grand collectionneur d’œuvres d’art, de disques et il a reçu des cartes postales de Calder, Satie… des cartons inventifs, et délicieux pour les yeux et le reste.

Je recommande chaudement l’exposition, il sculptait de mémoire, dans le matériau. Il s’est affranchi des moulages après un apprentissage par les ateliers de Rodin.

Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray comptaient parmi ses amis. Le 1er lui a payé son loyer un certain temps. Parmi ses voisins, Tinguely et Niki de St Phalle. Ces ateliers d’artistes qui donnaient sur la rue de Vaugirard ont été détruits dans les années 1970…

Il reste ses œuvres, son baiser, sa colonne sans fin, son poisson, son envol, ses visages, son coq, ses carnets, sa correspondance. Et o chance pour nous, il a tout conservé et légué !

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

#My favorite is Momoro#On my top three of favorite revolutionnary#Even if I admit his bad side#Dislike hightly Hebert but everyone has their own tastes#frev#french revolution#hébert jacques rené#Ronsin#Chaumette#momoro#cordeliers

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Contemporary descriptions of the hébertist execution compilation

The joy of the people was universal at seeing the conspirators taken to the scaffold. There were the same demonstrations of joy everywhere; a sansculotte jumped up and said: “I would light up my windows this evening, if candles were not so rare.” In the evening, in all the groups and cafes, people talked about the death of these conspirators; the story of their last moments was the only subject of conversation. It was said in several places that Hébert had denounced around forty deputies. It was time, they added, that this conspiracy was discovered, because it was believed in several departments that Paris was under fire. […] According to the comments made on the Place de la Révolution, during the appearance of the conspirators on the scaffold, one noticed that there were people placed to sow trouble. One woman was beaten by another for having made some comment. While the 19 conspirators were being guillotined, the people remained silent; but when Hébert’s turn came, a swarm of hats appeared, and everyone shouted: “Long live the Republic! This is a great lesson for those who are consumed by ambition; the intriguers have done well; the committees of public safety and general security will manage to discover them, and ça ira!”

Tableaux de la Révolution française publiés sur les papiers inédits (1869) by Adolphe Schmidt, volume 2, page 186. ”Situation in Paris 4 Germinal Year 2” (March 24 1794).

The events of yesterday, that is to say the judgment of the conspirators, their journey from the Palace to the Place de la Révolution and their execution, have entirely absorbed the attention and feelings of the people. Everyone wanted to at least see them pass so that they could judge the impression made on their wicked souls by the sight of an immense people, outraged by their crime, and the knowledge of the imminent death they were going to suffer. The crowd of curious people who were on their way or who witnessed their execution was innumerable. [...] Two opposing feelings, indignation against the guilty and joy at seeing the Republic saved by their death, animated all the spectators. One tried to read the faces of the condemned to enjoy, in a way, the internal pain from which they suffered: it was a kind of revenge that they took pleasure in obtaining. The sans-culottes were especially angry with Hébert and insulted him. “He’s damn angry,” said one, “we broke all his stoves (fourneaux).” “No,” said another, “he is very happy to see that the real aristocrats are going to fall under the guillotine.” Others carried stoves? (fourneaux) and pipes and raised them in the air so that they could strike Father Duchesne's eyes. Regardless, this wretch could not pay any attention to what was happening around him; the horror of his situation appalled him; he had reproached Custine for dying as a coward, and he showed no less pusillanimity than him. Momoro put up, as they say, a brave face against bad luck, he pretended to be confident, talked to his neighbors and laughed a wicked laugh. [...] Cloots appeared calm, Vincent lost, Ancart and Ronsin furious and Hébert overwhelmed. The latter was the star of the show, he appeared last [on the scaffold].

Report by the police spy Grisel, March 25 1794, cited in La Liberté ou la Mort: mourir en député (2015) by Michel Biard.

On D-Day, March 24, 1794, an “innumerable crowd” impatiently awaited the execution of Father Duchesne and his accomplices: “Advancing from the place of execution of Paris, one encountered waves of citizens on their way there; everything resounded with the cry of “Father Duchesne to the guillotine!” and in this respect the children acted as peddlers.” Another agent remarks that “in the streets, from the Palace to the Place de la Révolution, the crowds of people were so great that one could barely pass through.” The police estimate (already!) claimed that “perhaps four hundred thousand souls witnesses to this execution.” […] If the legend claiming that Hébert fainted in the tumbril seems false, all reports corroborate on the other hand the moral and physical collapse which this great sermonizer presented: […] “It was noticed that Ronsin seemed the least frightened by his execution, that Anacharsis Cloots had retained great composure, but that Hébert and the others bore on their faces the signs of the greatest consternation;” [Another report states that]: “Of the nineteen culprits dragged to execution, Hébert was the one who presented the saddest and most dismayed face.” Taken from the Palace to the Place de la Révolution amid cries of joy and insults (“Everywhere they passed one shouted “Long live the Republic!,” and threw hats in the air and everyone said some epithet to them, especially to Hébert.”), Father Duchesne was not yet at the end of his troubles. To make the feast complete, a cruel staging allowed him to meditate on his fate: “Upon his arrival on the Place de la Révolution, he and his accomplices were greeted by boos and murmurs of indignation. With each head that fell, the people took revenge again with the cry of “Long live the Republic!” while throwing their hats in the air. Hébert was saved for last, and the executioners, after putting his head through the fatal window, responded to the wish that the people had expressed to condemn this great conspirator to a punishment less gentle than the guillotine, by holding the suspended blade for several seconds on his criminal neck, and throwing, during this time, their victorious hats around him and attacking him with poignant cries of ”Long live this Republic that he had wanted to destroy.” As can be seem, one knew how to have fun in those days. However, as soon as the affair was completed, the agents noted contrasting reactions among the people: “In all public places, the aristocrats and the moderates rejoiced at this execution and affected a lot of patriotism. The patriots also rejoiced, but they observed one another.” [Another report states] “I visited different cabarets near the Gros Caillou, near the Military School. They talked only about Father Duchesne, about whom a thousand stories were made with the intention to bless the Committee of Public Safety for having discovered such a betrayal. I found the little people cheerful”; [Another report states]: “The walks are everywhere full of people and everywhere one stays and asks: “Did you go to see Hébert yesterday?” One answers “yes”. All the faces seem happy.” [Another report states]: “Since Hébert’s death, I have noticed that, in cafés, men who talked a lot no longer say anything.” This is because the execution of Hébert and his supporters, although it purged the Mountain of its extremists, nonetheless shook the people’s confidence in their leaders. Who would believe if even the most ardent patriots could suddenly become traitors? At least one thing is certain, that is that beyond the unconscious dismay which struck the people after the execution, the great cowardice which Father Duchesne demonstrated before the guillotine ended up destroying him in the eyes of everyone: “After the execution, everyone was talking about the conspirators. They said: “They died like suckers”; others said: “We would have thought that Hébert would have shown more courage, but he died as a good-for-nothing.”

Series of police reports found in Paris pendant la Terreur (1962) by Pierre Caron, cited in this blog post.

The execution took place in the afternoon around 5 o'clock, at the Place de la Révolution. A prodigious crowd of citizens filled all the streets and squares through which they passed. Repeated cries of long live the Republic and applause were heard everywhere. These testimonies of the indignation of the People against men who had just so eminently compromised the salvation of the Fatherland, were proportionate to the extreme confidence they had in the art of surprising them; and the public satisfaction whose feeling was mixed with this deep indignation was a new proof of the love of the citizens for the Republic saved by the punishment of these great culprits. Thus perishes anyone who dares to attempt the re-establishment of tyranny!

Gazette Nationale ou Moniteur Universel, number 185 (March 25 1794)

It was 18 of them who suffered the death penalty due to their crimes... It was Father Duchesne, this scoundrel, who was cursed by all the people. If he had been susceptible to remorse, he would have died of shame before his arrival, in front of Madame Guillotine... He was the last to be guillotined, each of the closest spectators continued to reproach him for his villainy...

Letter written by the Convention deputy Ayral Bernard, March 26 1794

Hébert, Ronsin, Vincent, and the other conspiracy defendants whose names and qualities we reported in previous issues, were sentenced to death by the revolutionary tribunal. Only one was acquitted; Laboureau: he was immediately set free; the president of the tribunal embraced him and made him sit next to him: the room resounded with the liveliest applause. The other defendants said nothing when they were sentenced; the Prussian Cloots appealed to the human race, of which we know that he had made himself the speaker. Ronsin wanted to say a few words, he was removed alongside the others. Femme Quetineau declared herself pregnant. Taken back to the Conciergerie, the condemned asked for half a septier of wine and a soup. Around four in the afternoon, they left on three tumbril to go to the execution. Never had an execution attracted such a considerable crowd of spectators; everywhere they passed, one clapped hands, tossed hats in the air, and shouted vive la république ! They seemed quite insensitive to the indignation that was brewing against them: arrived at the foot of the scaffold, they all embraced each other. Hébert, known as Father Duchesne, was the last to be guillotined; his head was shown to the people, and this spectacle provoked clapping of hands and universal cries of vive la république !

Annales Patriotiques et Litteraires de la France, et Affaires Politiques de l’Europe, number 369 (March 26 1794)

The republic has once again been saved: 19 leaders of the conspiracy hatched for its ruin were sentenced to death today, 4 germinal, at half past twelve. The flattering sword of the law struck their guilty heads: these traitors marched towards the scaffold with all the audacity of crime; some laughed, others raised their shoulders: Father Duchène appeared to be neither in great joy nor in great anger; the people applauded and stood in crowds in the places through which the procession was to pass. A lot of cavalry and infantry preceded, accompanied and followed the tumbrils carrying the conspirators: but armed force became useless, because joy was universal.

Le Courier Belgique, number 39 (March 31 1794)

Here is an anecdote which can serve to make better known the eighteen conspirators whom the sword of the law has struck down. On the day of their execution, several heads had already fallen when General Laumur's turn had come. Ronsin and Vincent looked at him at the scaffold and said to Hébert: ”without the clumsiness of this j... f... we would have succeeded.” They were alluding to the indiscretion of Laumur, who would tell anyone who would listen that the Convention had to be destroyed.

Suite de Journal de Perlet, number 555 (March 31 1794)

My father told me that only once, during the Revolution, he found himself stuck in the crowd, without being able to move forward or backward, as the fatal tumbril passed. It was the one who carried the Hébertists. Cloots, placed at one end, said to the spectators: “My friends, please do not confuse me with these rascals.”

Mémoires sur Carnot par son fils (1861) volume 1, page 366.

-

Previous parts of this totally family friendly series:

Contemporary descriptions of the dantonist execution compilation

Contemporary descriptions of the robespierrist execution compilation

#happy 230th deathday guys!!#french revolution#frev#frev compilation#hébert#momoro#no one likes hébert…#like jesus they REALLY hated him

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Cordeliers Club (J. Guilhaumou)

The Cordeliers Club « is more famous than known » : with these words, the historian Albert Mathiez defined the major difficulty of every overview on the club, within whose history entire sections, for lack of sources or studies, remain obscure.

It is highly probable that the club already existed in April 1790 under the title « club of the rights of man ». It appeared under its full name Society of the friends of the rights of man and of the citizen in June 1790. An address of the Cordeliers of the same year proclaims that the patriots have to devote themselves « to the defence of the victims of suppression and to the relief of the unfortunate », and, in this capacity, adopted the eye, a symbol of surveillance, as the seal of the society. In the beginning, the club held its sessions in a room of the Cordeliers Convent. Being persecuted by the municipality, the Cordeliers ended up settling in the locale of the Musée, Hôtel de Genlis, Rue Dauphine, where they would remain throughout their existence.

Under the auspice of the rights of man and of the citizen, displayed behind the president in the debate room, the club presented a particular physiognomy. It thereby clearly distinguished itself from the Jacobin Club on the various levels of its existence : local (around the section of the Théâtre-Français), regional (in Paris) and national (in 1793). The Jacobins endeavoured to follow the initiatives of the National Assembly as closely as possible and to form a network of affiliated societies which would reverberate and enrich their propositions. The Cordeliers favoured their mission of surveillance and of control towards the constituted authorities. This is why they admitted women to their society, as well as passive citizens. A. Mathiez could say that they formed « a group of action and combat » that was always in a state of alert when it was a matter of reacting to breaches of the rights of man. Thus, the club was a favoured place of encounters, of exchanges between spokespersons, hommes de liaison, commissioners and other political mediators who wanted to apply the avowed droit naturel, the Constitution.

The club owes its first success, in 1791, to the federation which it established with the fraternal societies, which originally have been formed in its wake. Marat, a Cordelier par excellence, received the title « father of the fraternal societies ». Numerous revolutionary personalities frequented the club, although it is not possible to point out a leader : Danton, Hébert, Vincent, Rutledge, Legendre, Marat, Lebois, Chaumette, etc.

Increasingly critical towards the executive power, the club took the helm, during the spring of 1791, of the democratic movement in favour of the establishment of the Republic. After the king's flight, and in the moment of the composition of the Champ de Mars petition, the Cordeliers defined their principal and permanent objective : it was necessary to « proceed to the replacement and the organisation of a new executive power ». In the aftermath of the Champ de Mars Massacre (17 July 1791), due to repression and internal divisions, the club was weakened. It recovered its strength, in 1792, through the mediation of the network which it had built with the popular societies of the provinces. Thus, it would serve as the voice of the fédérés of 10 August and play a non-negligible role in the proceeding of the insurrection against the king. The position of the Cordeliers was consolidated during the winter of 1792-1793, at the time where the Jacobins collided with the Enragés. The growing importance of figures such as Hébert, the Père Duchesne, and Marat assured them a certain renown. But the club only reached a national dimension at the end of the insurrection of 31 May, 1 and June. Around it, several institutions gathered : the revolutionary committees of the sans-culotte sections, the Ministry of War where Vincent cut his teeth, the Commune of Paris and, of course, the popular societies. During the summer of 1793, the club conquered, with the help of the delegates for the festival of 10 August, a hegemonic position within the Jacobin movement. One can speak, at that time, of the Cordelier or « Hébertist » movement (A. Mathiez). Hébert, in Le Père Duchesne, defined the watchwords of the revolutionary movement. Vincent, for his part, explained his project for the organisation of the executive power at the club. The Cordeliers distanced themselves from the sans-culotte movement through their refusal of direct democracy. The Cordelier programme began to be realised, particularly in Marseille, by the assembly of the popular societies' central committees. But the Robespierrist Jacobins, partisans of « legislative centrality », were determined to put an end to the Cordelier offensive. In spite of their victory during the revolutionary journées of 4 and 5 September, which brought about the creation of the revolutionary army and the mise à l'ordre du jour of the Terror, the Cordeliers were attacked at the Jacobin Club by Robespierre and Coupé de l'Oise, at the National Convention by Billaud-Varenne during the second fortnight of September. Then began a series of skirmishes which resulted in the arrest of Vincent and Ronsin (17 December 1793). In the provinces, the representatives en mission, denounced by the Cordeliers, forced the central committees to dissolve.

In early 1794, the club turned back into a district club, influential in some sections, and closer to the demands of the Parisian popular movement. Now, what about the famous « Cordelier insurrection » of Ventôse, Year II? It was in fact a matter of political « manipulation » that was arranged by the Montagnards in order to deliver a first blow to the popular movement. The journalists, interpreting Hébert's moral call to insurrection in a political sense, strongly contributed to such a manipulation. It was their revenge against the Père Duchesne! After the arrest and execution (14 and 24 March 1794) of the Cordelier « leaders », the club, even after having been purified, ceased to gather permanently.

Source: Dictionnaire historique de la Révolution française (Albert Soboul)

#French Revolution#frev#cordeliers#club des cordeliers#translation#hébert#Danton#ronsin#vincent#marat#legendre#chaumette#dhcordeliers#jacques guilhaumou

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Magic sword, magic hair (Roger Ronsin, Rêve de Dragon 1e, Nouvelles Éditions Fantastique, 1985)

#Reve de Dragon#Roger Ronsin#JDR#jeu de role#Rêve de Dragon#jeu de rôle#fantasy RPG#magic sword#big hair#1980s#magic#Nouvelles Editions Fantastique

134 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Niki de Saint-Phalle, Shooting Impasse Ronsin, 1961

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

@HiTommySwisher drops a fiery new lyrical helping with "Fall For Me"

@HiTommySwisher drops a fiery new lyrical helping with “Fall For Me”

Meet SWISH. the 23 years old independent artist from East St Louis, Illinois. Today we present his beautifully gloomy new visual for the thriving single “Fall for Me” featuring fellow artist and friend Brad Jennings. Produced for SWISH. by industry legend Jim Jonsin after they met in Miami. The song is doing very well on both Spotify and Soundcloud with over 400k on Spotify & nearly 200k on…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Regarding Marshal Ney’s trial

I don’t like to reblog myself, but Josefavomjaaga offered this comment to my “Happy birthday, Marshal Ney” post that I’d like to reply to.

Josefa wrote, about the trial: “As for the trial, I am not sure of the legal procedures but I understand there had been an amnesty? That somehow was not granted to Ney? Éric Perrin in his book wonders several times in how far Ney’s behaviour towards colleagues and subordinates may have influenced the latters’ judgement when it came to the death sentence.”

There was indeed some kind of amnesty, which had been worked out between Davout and the authorities of the restored Monarchy. I don’t remember the details off-hand. Davout was outraged that this amnesty would be disregarded, and although he and Ney were not at all on friendly terms, Davout tried to testify to that effect. If my memory isn’t playing tricks on me, the Chamber of Peers did something very disingenuous, something like determining that Davout’s testimony was irrelevant, or even preventing him from testifying.

Prior to his trial before the Chamber of Peers, Ney was supposed to be court-martialed. Those nominated to judge him included fellow Marshals Jourdan (presiding), Mortier, Masséna, Augereau, and two respected Generals, Claparède and one other who I can’t remember. Ney petitioned to be judged before the Chamber of Peers, because he feared the verdict of the court-martial. The members of the court-martial were delighted to declare it unconstitutional or whatever other excuse they wre able to dream up; they were not at all eager to sit in judgement of Ney.

Ney, as it turns out, was much mistaken about where his chances were better. Before his own death just six months after Ney's execution, Augereau declared (again quoting from memory): “We did not sit in judgement of Ney because we were cowards. If we had judged him, he would still be alive.”

Several fellow Marshals sitting in the Chamber of Peers did vote for the death penalty. They were three of the honorary Marshals, namely Kellermann, Serurier and Pérignon. As far as I know, none of these had many or even any dealings with Ney, except, possibly, Kellermann in whose army Ney fought at Valmy as a very junior officer or even as a soldier. Famously, Marmont did vote for the death penalty. Victor also did, but regretted it until his own death.

I speculate that fellow Marshals and superior officers, whatever resentments they might have had against Ney, were unsure what to do about him, and maybe especially unsure about what a vote one way or the other might mean for themselves. On the one hand, they could see for themselves that the authorities of the restored régime were more than ready to overlook formal agreements that they did not like: they saw what happened when Davout tried to testify for the defense. In addition, just a few months before Ney’s trial but quite outside any legal framework, Marshal Brune had been assassinated by Royalists in an act of mob violence reminiscent of the mob violence that was a feature of the Revolution from its very onset.

What is more, all the superior officers of the time had lived under the Revolution and then the Terror. General Alexandre de Beauharnais had been guillotined under the flimsiest of pretexts during the Terror. The famed Lazare Hoche came very close to the same fate. Kellermann himself, the hero of Valmy, for reasons I don’t know had spent quite a lot of time imprisoned by the Revolutionary authorities and, like Hoche, most likely owed his survival only to Robespierre’s fall. Berthier was dead by the time of Ney’s trial, of course, but let’s consider an aspect of his career: he served under Custine, and Custine was guillotined; he served under Lückner, and Lückner was guillotined; he served under Biron, and Biron was guillotined; he served under Ronsin, and Ronsin was guillotined; he served under Kellermann, and Kellermann was in all likelihood destined to the guillotine. I’m referring to Berthier (whose survival is a true miracle), but the fate of all these generals was known by all who served in the army. How secure would senior military officers feel when thinking back about how dangerous it could be to serve France during turbulent times? So whether Ney’s past behaviour had much of a role to play in the outcome of his trial uncertain at best, in my opinion.

Please forgive any inaccuracies in the facts I quoted. They are all summoned from memory, as I don’t have access to research materials at this time.

39 notes

·

View notes