#comte de ségur

Note

Hello! I hope you’re having a wonderful day.

I was wondering if you had any idea on where to look for informations about the Noailles family.

The only sources I could find was Adriennes biography, and Anything that had to do with Lafayette. So wondered if you knew of any other materials I could take a look at. (Maybe about Adrienne’s sisters, parents, or cosines, other relatives etc.)

Dear Anon,

I have to make a confession – the Noailles-family never has captured my interest quite *that* much and therefor my answer may be a bit limited. Then again, there has been a lot less published about the Noailles-family then about the La Fayette-family.

You mentioned that you had a look at biographies about Adrienne – I do not know which ones you consulted; maybe you already know some of the ones I am going to suggest.

La Vie de Madame de Lafayette is a book that Adrienne and her youngest daughter Virginie co-authored. Adrienne wrote the first half of the book about her mother, de Duchess d’Ayen, and Virginie wrote the second half about Adrienne and then went on to publish the book after her mother’s death. While La Fayette is mentioned in both parts, he is only a minor character in this book.

Anne-Paule-Dominique de Noailles, Marquis de Montague (the title varies sometimes a little depending on the edition and/or the translation) are the Memoirs of Adrienne’s second youngest sister. Anne survived both her sister Adrienne as well as her brother-in-law La Fayette and died in 1839. The book gives great insight into her life.

Madame de Lafayette and her family by Mary McDermont Crawford is an old book that deals in large part with the La Fayette-part of the family – but the Noailles-part is represented as well, even some of the more “minor” members of the family.

I also would suggest the Memoirs of the Comte de Ségur. Now, I do not use his Memoirs as often as I could, but since Ségur was a family friend both to the La Fayette’s as well as to the Noailles’ I believe that there should be something in his Memoirs.

I know that the Archive in Geneva has a few letters from and to the Duc d’Ayen and his second wife, Adrienne’s step-mother, but these letters are hard to access online.

Now, if you are really interested and do not mind a bit of digging, I can recommend the letters of La Fayette (especially the earlier letter that we have) and of John Adams (when he was ambassador in France). Both had a lot of contact with the Noailles and either wrote to members of the Noailles-family directly or mentioned incidents of the family live as well as, in Adams case, commenting on the family members and their behavior/opinions/etc.

It is not much but I hope that you can use this at least as a starting point. I hope you have/had a wonderful day!

#ask me anything#anon#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#history#de noailles#john adams#comte de ségur#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#resources#anne paule dominique de montague#duchess d'ayen#duc d'ayen

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

*rises from the ashes* I LIVEEEE

this was a commission for @nerenight, still involving 18th century lore i know little to nothing about (absurd!!!)

close ups bc they turned out pretty:

#my art#artists on tumblr#18th century#featuring (from left to right):#louis marie de noailles#marquis de lafayette#(i ain't writing his whole name)#louis philippe comte de ségur

400 notes

·

View notes

Text

lafayette throws it back at versailles not clickbait (lafayette pt. 2)

im not gonna lie, this is my favorite part of lafayette's life to talk about. he was so teenage boy i love it. anyway, if you missed out on part one, here's the link. @thereallvrb0y and other esteemed guests, i hope you enjoy

Court Life

Lafayette was presented at the Court of Versailles on Saturday, March 26, 1774 when he was 16. I'm not gonna go super in depth about how the court works (but it is very interesting, i recommend learning about it), but i will tell you that Gilbert was the biggest black sheep, which was unideal because the court was already judgmental as hell.

Several different people described how awkward Lafayette's demeanor was, and it made a lot of people think he was just rude. Lafayette said this was only made worse "by the gaucheness of my manners which, without being out of place on any important occasion, never yielded to the graces of the court or to the charms of supper in the capital." -Mémoires

The Comte de Ségur was a close friend, who recognized that Gilbert wasn't just an asshole, and he was deep down a very passionate person. (Ségur experienced this first hand when Lafayette tried to duel him over a girl that Ségur didn't even know).

His awkwardness wasn't helped when he danced with Marie Antoinette and, well... "...the Queen could not stop herself from laughing." -Correspondance entre le Comte de Mirabeau et le Comte de La Marck

When I say Lafayette was very passionate deep down, it wasn't actually... that deep down, and he still proved himself to be his rebellious teenage self in what I like to call the Comte de Provence Incident.

The Comte de Provence was the brother of Louis XVI, and, obviously, held a major place in court. Like the king, he had a little entourage of men who followed him around and did whatever he said. This was a position that offered a lot of opportunities, but you didn't just. insert yourself into it. You had to be invited. And, at the time, The Noailles family was trying to find a permanent place for Lafayette at Versailles.

So, in 1775, the Maréchal de Noailles tried to get Lafayette in this little entourage, and had to introduce him to Provence, an opportunity for which came in the form of a masked ball before Lent (in France, this is just a lame Mardi Gras).

This would have gone fine if Lafayette wasn't completely determined to fuck shit up. so.

Lafayette and Provence were talking (wearing masks, this is an important detail), and Provence started bragging about how good his memory was. Lafayette responded by saying "memory is a fool's intellect". Provence was like "uhhh wtf" and just assumed that Lafayette didn't realize he was the King's brother, so he said "do you realize who the fuck you're talking to you little shit" (obviously not a direct quote, it was in French.) And. Lafayette responded. just being like. "yeah lolz"

So, he didn't get a place at Versailles.

Which is kinda stupid! He should not have done that! Because at this time he was really trying to get a rank in the French army, and he could have had a better opportunity, but whatever because he was granted a command for a full company in Metz.

Uh oh, suspicious shit is going on

While in Metz (not really doing anything important), Lafayette met Comte de Broglie, who was the ambassador of Metz. Broglie was suspicious as fuck and had a career of weird secret projects under the crown, including a plan to invade England.

Broglie had heard of the American cause (which was, at this point, pretty far along and going to shit). He thought that Washington was replaceable, and that he could lead the rebel forces, and then colonize them for France. Not! Good!!

When Broglie met Lafayette, he was like.... this kid is. dumb as fuck. So, he introduced him into his circle, therefore introducing him to Revolutionary ideology. Little gullible Gilbert saw Broglie as like an idol, and since Broglie was a Freemason, Laf decided to become one too. This was significant because being a Freemason is the reason Gilbert met Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburg. If you're like "hmmm Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburg, that name rings a bell", you're a nerd, and its because he was King George III's younger brother who was weirdly supportive of the colonies' rebellion.

Along with Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburg and Broglie I guess, Gilbert was introduced to the ideals of Abbé Guillame Raynal, who preached anti-monarchy, anti-clergy, and anti-slavery rhetoric. So, basically, Lafayette was radicalized and became a blue haired liberal.

Eventually, Broglie and "Baron" Johann de Kalb (he's in Duty and Inclination in case you were wondering) to go to America woo!!!

Side note on de Kalb, he's not evil like Broglie, though he did know about the plan. He ended up legitimately helping the revolution, so shout out de Kalb

Lafayette convinced his buddy Ségur and his brother in law, Vicomte de Noailles, to go with him. Together, they all visited Silas Deane, who is a fucking dumbass who kept giving French people paid commands without permission from Congress *foreshadowing noise*

Lafayette used all six of his sweet wholesome cinnamon roll twink braincells to create a plan to get out of France without getting caught, and the author of The Marquis; Lafayette Reconsidered, Laura Auricchio, has a very good take on Lafayette's character shown in this instance:

“Although he often described himself as a man of action, Lafayette was more deliberative than he let on, and he habitually watched and waited before determining the best way to proceed; once he chose his course, however, it was almost impossible to steer him away.” -Laura Auricchio

So, the pact to join the American Revolution between Lafayette Ségur and Noailles was made in October 1776. Lafayette was optimistic, as always, but still expected nothing but obstacles, the most formidable of them being from the Noailles family.

First things first, they met with Deane, as I mentioned, with de Kalb translating. They signed a letter of agreement on December 7, 1776, which completely overlooked the fact that Lafayette had 0 qualifications to be a major general. Then, Lafayette bought a ship named La Victoire. The Gang (tm) met continuously in secret.

Then, Lafayette sent two letters, one to Adrienne, and the other to duc d'Ayen, explaining his departure and expressing his regret, especially since Adrienne was pregnant and raising their young daughter.

Quick breakdown of the Lafayette kids: Henriette du Motier de Lafayette was born on Decmeber 15, 1775, making Lafayette a girl dad from the beginning. Adrienne was pregnant with Anastasie Louise Pauline du Motier de Lafayette when Gilbert departed, and she gave birth to her on July 1, 1777. You can tell which two were born after the Revolution just by their names: Georges Washington Louis Gilbert du Motier de Lafayette (born December 24, 1779 after Lafayette's visit back to France), and Marie Antoinette Virginie du Motier de Lafayette, known as Virginie (a reference to Virginia), (born on November 2, 1782, after Lafayette returned home after Yorktown).

Lafayette's disappearance was... a massive scandal. And you may be thinking "why? like yeah he's rich but clearly no one likes him, who cares where he goes?"

The king. The king cares where he goes. The main reason being that France was not openly at war with England aaand Lafayette may or may not have met King George III. Personally. Like a few weeks before he left. Aaaand the British government might just assume that a nobleman of such high status, that they knew personally, leaving to join the colonies' rebellion is an act of war. so. the king cares a lot.

D'Ayen panicked and wrote to Louis XVI telling him that Lafayette was gone like the good bootlicker snitch he is, and Louis issued orders for Lafayette's arrest. He was almost caught a couple times, so he had to travel in disguise (this is why people talk about him dressing up as a woman, tho we can't really prove or disprove that), but La Victoire set sail before they could catch him, and Lafayette embarked on his first very seasick journey across the sea.

This one is a little short, because if I had gone into as much detail about how everything works, it would be unnecessarily long, and the next few will likely be unnecessarily long because they are about the Revolution *eagle screech* so yeah, look out for that

#history#amrev#marquis de lafayette#lafayette#adrienne de lafayette#henriette de lafayette#american history#french history#frev#amrev history#do it for richie 💪

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once more Lafayette began to think of returning to the United States. English spies and Paris rumor, which he had not discouraged, already had him on his way; and in America he was daily expected--some said, with a numerous fleet and a large body of soldiers. The Comte de Ségur, arrived in America, wrote to his wife: 'Tell Lafayette that I am in a country filled with his name where everyone adores him.'

Lafayette In America - The Close of the American Revolution - Franklin's Aide by Louis Gottschalk, pg. 363, describing the general anticipation Lafayette's guns-and-ships return created on both sides of the sea.

#marquis de lafayette#lafayette#gilbert du motier#comte de segur#lafayette in america#louis gottschalk#pg. 363

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

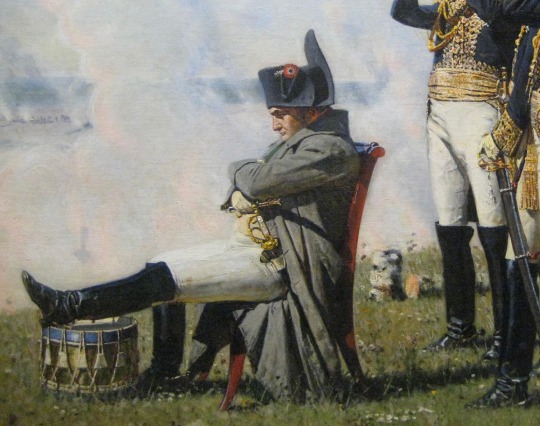

Recollections from Lejeune and Ségur on Napoleon’s uncharacteristic lack of energy, possibly a result of illness, at Borodino.

***

I was surprised that the Emperor had shown so little of the eager activity which had before so often ensured success. On the present occasion he had not mounted except to reach the battle field, and had remained seated below his Guard on a sloping mound, from which he could see everything. Several balls had passed over his head. Whenever I returned from the numerous errands on which I was sent, I found him still seated in the same attitude, following every movement with the aid of his pocket field-glass, and giving his orders with imperturbable composure. But we did not see him now, as so often before, galloping from point to point, and with his presence inspiring our troops wherever the struggle was prolonged and the issue seemed doubtful. We all agreed in wondering what had become of the eager, active commander of Marengo, Austerlitz, and elsewhere. We none of us knew that Napoleon was ill and suffering, quite unable to take a personal part in the great drama unfolded before his eyes, the sole aim of which was to add to his glory. In this terrible drama had been engaged Tartars from the confines of Asia, with the élite of the troops of some hundred European nations, for from the east and from the west, from the north and from the south, men had flocked to fight with desperate courage for or against Napoleon. The blood of some 80,000 Russians and Frenchmen had been shed to consolidate or to overturn his power, and he looked on with an appearance of absolute sang-froid at the awful vicissitudes of the terrible tragedy. We were all anything but satisfied with the way in which our leader had behaved, and passed very severe strictures on his conduct. Supper interrupted our discussion, and after it we were soon all wrapped in heavy slumber, whilst the chief, whom we had been accusing so severely, was watching and studying how best to resume the conflict the next morning.

—The Memoirs of Baron Lejeune, Vol II

***

Belliard then returned for the third time to the emperor, whose sufferings appeared to have increased. He mounted his horse with difficulty, and rode slowly along the heights of Semenowska. He found a field of battle imperfectly gained, as the enemy’s bullets, and even their musket-balls, still disputed the possession of it with us.

In the midst of these warlike noises, and the still burning ardour of Ney and Murat, he continued always in the same state, his gait desponding, and his voice languid. The sight of the Russians, however, and the noise of their continued firing, seemed again to inspire him; he went to take a nearer view of their last position, and even wished to drive them from it. But Murat, pointing to the scanty remains of our own troops, declared that it would require the guard to finish; on which, Bessières continuing to insist, as he always did, on the importance of this corps d’élite, objected “the distance the emperor was from his reinforcements; that Europe was between him and France; that it was indispensable to preserve, at least, that handful of soldiers, which was all that remained to answer for his safety.” And as it was then nearly five o’clock, Berthier added, “that it was too late; that the enemy was strengthening himself in his last position; and that it would require a sacrifice of several more thousands, without any adequate results.” Napoleon then thought of nothing but to recommend the victors to be prudent. Afterwards he returned, still at the same slow pace, to his tent, that had been erected behind that battery which was carried two days before, and in front of which he had remained ever since the morning, an almost motionless spectator of all the vicissitudes of that terrible day. (…)

After he had retired to his tent, great mental anguish was added to his previous physical dejection. He had seen the field of battle; places had spoken much more loudly than men; the victory which he had so eagerly pursued, and so dearly bought, was incomplete. Was this he who had always pushed his successes to the farthest possible limits, whom Fortune had just found cold and inactive, at a time when she was offering him her last favours? (…)

Murat then exclaimed, “That in this great day he had not recognized the genius of Napoleon!” The viceroy confessed “that he had no conception what could be the reason of the indecision which his adopted father had shown.” Ney, when he was called on for his opinion, was singularly obstinate in advising him to retreat.

Those alone who had never quitted his person, observed, that the conqueror of so many nations had been overcome by a burning fever, and above all by a fatal return of that painful malady which every violent movement, and all long and strong emotions excited in him. They then quoted the words which he himself had written in Italy fifteen years before: “Health is indispensable in war, and nothing can replace it;” and the exclamation, unfortunately prophetic, which he had uttered on the plains of Austerlitz: “Ordener is worn out. One is not always fit for war; I shall be good for six years longer, after which I must lie by.”

—General Philippe-Paul, Comte de Ségur, History Of The Expedition To Russia, Undertaken By The Emperor Napoleon, In The Year 1812

#Napoleon#Napoleon Bonaparte#Napoleonic wars#Louis-François Lejeune#Comte de Ségur#Borodino#1812#memoirs

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another one enchanted and mesmerized by Bonaparte

I found myself the next day at the hour named in the gallery of Mars at St. Cloud, where Duroc presented me to Bonaparte. The much too flattering words which that great man let fall on this occasion, while overwhelming me with astonishment, had the effect of attaching me once for all to his person. "Citizen Segur," he said, in a loud voice, before a crowd of senators, tribunes, legislators and generals, "I have placed you on my private staff; your duty will be to command my bodyguard. You see the confidence which I place in you, you will respond to it; your merit and your talents will ensure you rapid promotion!"

As much delighted as surprised by such a flattering reception, in my agitation I could only answer by a few words of gratitude and devotion, which Napoleon received with one of his indescribably gracious smiles; continuing his way through the crowded assemblage of personages of more or less note, he went on to the gallery of the chapel in which he heard mass.

Intoxicated with joy and gratified pride beyond the bounds of expectation, and feeling as if I trod on air, I walked up and down these brilliant chambers as if taking possession of them, turning back and again stopping on the spot which even at this lapse of time I can still see before me, the spot where I had just listened to such expressions of esteem and regard, meditating upon them, and repeating them over a hundred times. It seemed to me as if they associated me, as if they identified me, with the renown of the Conqueror of Italy, of Egypt, and of France! I do not know what that autumn day was really like, but it has remained in my memory as the most beautiful, the most glorious day that ever shone upon me in my life.

When I returned to Paris to my father's humble abode, it was only with blushes and under my breath, that in telling my story I could repeat these words of praise which must have appeared almost beyond belief.

An Aide-de-Camp of Napoleon by Comte de Ségur

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The door of the monument was open, Napoléon paused at the entrance in a grave and respectful attitude. He gazed into the shadow enclosing the hero's [Frederick the Great] ashes, and stood thus for nearly ten minutes motionless, silent, as if buried in deep thought. There were five or six of us with him: Duroc, Caulaincourt, an aide-de-camp and I. We gazed at this solemn and extraordinary scene, imagining the two great men face to face, identifying ourselves with the thoughts we ascribed to our Emperor before that other genius whose glory survived the overthrow of his work, who was as great in extreme adversity as in success."

(General Ségur)

#Napoleon#Napoleon Bonaparte#frederick the great#Géraud Duroc#Duroc#Armand-Augustin-Louis Caulaincourt#Caulaincourt#Philippe Paul comte de Ségur#Ségur#Napoleonic era#history#french history#napoleonic wars

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marshal Ney’s trial: the first Royal decree

I will now broach the subject of Marshal Ney’s trial. Welcome, fellow nerds! Some of us find matters such as this quite enthralling.

I wrote in a previous post:

Two decrees of July 24, 1815 sealed the fate of Marshal Ney. The first one struck off the names of twenty-nine Peers of the Chamber: Marshal Ney was in fifteenth position. The second one included nineteen names of people to be brought before a council of war for treason against the King: this time Ney was in first position.

He then left to take refuge in the castle of Bessonis in the Lot, which belonged to a relative of Marshal Ney. He arrived there on July 29. [...] He was then exposed and arrested on August 3, 1815.

The first decree was to name the 29 Peers (or 'peers', with a conspicuous lower case “p”) who were to be expelled from the Chamber of Peers (with a capital “P”), because they occupied functions incompatible with the Peerage while the 'usurper' was in power from March 20 until Louis XVIII’s return.

(No. 40) ORDINANCE OF THE KING containing the List of persons who are no longer members of the Chamber of Peers.

At the Palace of the Tuileries, July 24, 1815.

LOUIS by the grace of God KING OF FRANCE AND OF NAVARRE, to all those who will see this, SALUTATIONS.

It was reported to us that several members of the Chamber of Peers agreed to serve in a so-called Chamber of Peers, appointed and assembled by the man who usurped power in our States from the 20th of March until our return to the Kingdom.

[...]

The list of those expelled is as follows. Several names will be familiar to Napoleonic history enthusiasts:

Count Clément de Ris

Count Colchen

Count Cornudet

Count d'Aboville

Marshal Duke de Dantzick [Marshal Lefebvre]

Count de Croix,

Count Dedeley-d'Agier

Count Dejean

Count Fabre de l'Aude

Count Gassendi

Count Lacépède

Count de la Tour-Maubourg,

The Duke of Praslin

The Duke of Plaisance

Marshal of Elchingen [Marshal Ney]

Marshal duc d'Albufera [Marshal Suchet]

Marshal duke of Conégliano [Marshal Moncey]

Marshal duke of Treviso [Marshal Mortier]

Count de Barral, Archbishop of Tours

Count Boissy-d'Anglas

The Duke of Cadore

Count de Canclaux,

Count de Casa Bianca,

Count de Montesquiou

Count de Pontécoulant

Count Rampon

Count de Ségur

Count de Valence

Count Belliard

For the life of me, I can never remember who the Comte de Cadore and the Comte de Plaisance were. They were two of Napoleon’s ministers, not military men. Eventually, I’d like to find out who some of these other people were, and what they did to get up the King’s nose.

Article 2 of the decree exempts from expulsion those who could prove that they did not sit, nor wished to sit in the Chamber of peers with a lower-case “p”. I don’t know if any of the 29 took advantage of this exemption.

After a tiny bit of further bureaucratese, the decree is signed by both the King and the Prince de Talleyrand, no longer the Prince de Benevent.

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

François Gérard, Philippe-Paul, comte de Ségur, n.d. Château de Versailles. (x)

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Comte de Ségur, Jacques-Louis David, 1805-1824, Harvard Art Museums: Drawings

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop

Size: 21 x 16.4 cm (8 1/4 x 6 7/16 in.)

Medium: Black crayon, squared in black crayon, on off-white antique laid paper

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/190553

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comment from @therevwriter:

I'm intrigued. Where does Mr. Bi Disaster come from? Everything I've read paints him as constantly obsessed with women. I'd be interested to explore some other sources, because the JPJ in my head is a womanizing asshole and I'm always open to having my opinions altered through new info.

There is potentially a lot to explore here. I’ve discussed some of these things at varying lengths on my blog in the past, but it’s been like 3-4 years ago at this point so I figure it wouldn’t hurt to have a more somewhat comprehensive overview on the topic of John Paul Jones, the evidence that he may have been bisexual, and his complicated relationship with trust, women, sex, and depression and how those all tie together into the well-deserved imagining that JPJ could be perceived as a womanizing asshole.

I’ll ramble a bit.

The fastest point to address here would be the bisexual one. I had never face palmed harder in my life than when I read Evan Thomas’ biography on John Paul Jones and he said that there was no evidence that Jones was Bisexual immediately after including an explicitly bisexual poem Jones wrote in Latin simply because there was ‘no concrete evidence that Jones actually slept with any men.’ (Thomas, 232.) After having repeatedly speculated the entire book that any women Jones so much as looked at, he also fucked with zero evidence to back up any of those wild claims. He couldn’t fathom the idea of a man being friends with a woman who named him the godfather of her child and him actually loving his god child. He basically said that the only way this was possible is if Jones was actually somehow the real father and I rolled my eyes so far back in my head it hurt. Sure Jones was kind of a slut but jesus. I thought about it more later and laughed so hard because Thomas on the subject was just the living embodiment of ‘a guy could write down in a diary that on x date at x time he had sex with another man’ and straight white male historians would still find a way to say “Well...” I counter, do we really need more evidence than the poem (linked here if you want to read a clunky translation of said semi-erotic poem) to speculate that there was a very real chance that Jones was Bisexual without dismissing it outright immediately as impossible?

(an aside: when you have a reputation for womanizing, no one would suspect a thing about you sleeping with men as well. Unfortunately his womanizing reputation made him easy to target and for people to believe the crime for, re: his time in Russia where he was framed by his political enemies for assaulting a young girl, a crime punished by beheading, the plot for which was just barely uncovered before Jones killed himself instead and then also the time Ben Franklin told Jones that while he was at sea a maid stole Jones’ clothes and assaulted another lady during a festival while dressed like him and the lady’s sons went on a man hunt looking for him.)

It’s unfortunate that historians can easily explain any mlm tendencies at sea on just that: being at sea. But I do have to acknowledge that reality. As someone who is asexual I am well acquainted with the idea that action =/= attraction. And Jones, very explicitly, wrote that he’s just as comfortable being on both the giving and receiving ends of sex with men as he is with women (and I mean that, the poem also possibly suggests he’s down with getting pegged).

On top of that, the poem was written in Latin. I’ve mentioned before that the likelihood that any of the people on board Jones’ crew would be in anyway well-versed in understanding Latin is... extremely unlikely. Most men who set out to sea were generally uneducated. he wrote a bisexual poem in the language of the gays that no one around him at the time would ever be able to understand should they have come across it.

When it comes to Jones and women, things get complicated. John Paul Jones is a tragic figure. He was his own worst enemy and on top of that, his life was a string of endless betrayal after betrayal by those he thought he could trust. He was paranoid by nature and that reinforced it, to the point of serious health complications caused by lack of sleep because he was too afraid of mutiny happening in his sleep. Ironically, he was also a terrible judge of character and easily blinded by flashy displays of wealth and empty flattery from attractive men, which burned him. People often used him and then tossed him aside. He suffered greatly for it. One of the examples of this that hurts me the most is that the man Jones trusted most during the AmRev was actually a British Spy. Jones considered Edward Bancroft to be his closest and most intimate friend and confidant. Jones never suspected Bancroft was feeding the British all of his plans and had even come up with a cipher for the two of them to communicate. The Battle of Flamborough Head that won Jones his fame was only possible because, just once, Bancroft... for some reason... decided not to snitch. Maybe he’d gone soft on Jones? Who knows. The reveal of Bancroft’s ultimate betrayal after the war was definitely one of the final straws for Jones, though. He never trusted again.

The reason why this is important to note is that one of my favorite quotes from Jones is one that’s revealingly honest about why it’s easy to see him as a womanizing asshole. A female acquaintance of his later in life confronted him on the matter, calling him out on how he prefers taking lovers over making friends. Jones then admitted “sad experience generally shows that where we expect to find a friend, we have only been treacherously deluded by false appearances.” (quote pulled from Thomas 303 because I can’t access the JPJ papers these days). As a very social man, Jones was probably starved for human contact but he isolated himself from people and refused to make friends he believed would inevitably betray him, settling for attempting to satisfy what was probably a deep seated longing for genuine human connection with strings of shallow dalliances (never able to trust enough to fall in love) that never filled the endless yawning void of his spiraling depression. (catch me crying in the club for the umpteenth time about Jones saying “I would have faced death a thousand times, but today I desire it” [quote pulled from the memoirs of diplomat Comte de Ségur]).

Jones is a thoroughly complex and intriguing disaster of a human being to study and he fascinates me to no end for that reason and I love reading about him and trying to peer between the lines at the shattered man underneath all of the peacocking and unsatisfiable ambition.

#John Paul Jones#i'd wait to post this till the 6th but why the hell not#might as well get an early start#continental navy#captain john paul jones#I didn't feel like spending time on properly sourcing instances cuz this is tumblr and I'm in grad school and its summer break so i'm lazy#but i can go more in depth and sourced about any topic I touched on in this post if asked

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

I shall carry out all your commissions, and I shall point out the patriotic sacrifice you are making in temporarily exchanging your sword for a pen. I request that you love my wife, hug my children, take my place with my father, and join us as soon as you can to sound the charge or beat the farewell retreat.

The comte de Ségur to the Marquis de La Fayette, July 7, 1782

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 5, January 4, 1782‑December 29, 1785, Cornell University Press, 1983, p. 51.

#quote#letter#1782#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#american history#american revolution#comte de ségur

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“A full scale attack..”

Davout now received virtually all of his instructions directly from the Major General. He came to feel more and more that these orders were in bad taste, and that Berthier was endangering the opening operations of the campaign as he had in 1809. Davout had in fact lost all confidence in the man whom Napoleon had chosen as his second-in-command. At Marienburg “Davout expressed himself harshly, and event went so far as to accuse Berthier of incapacity or treachery.” The Emperor, in whose presence this quarrel took place, and who was well aware of Berthier’s lack of enthusiasm, tended to side with Davout whose ardent support of the campaign was well known to all. But Davout’s triumph over his old enemy was short-lived. Napoleon went on to Danzig the following morning where he was joined by his Major General. Here Davout’s enemies were able to gain the Emperor’s ear without the Marshal present to defend himself. They twisted his diligent preparations, his endless labor, and his enthusiasm, and used them against him. “’The marshal,’ they said, ‘wishes to have it thought that he has foreseen, arranged, and executed everything. Is the emperor, then, to be no more than a spectator of this expedition ? Must the glory of it devolve on Davoust [sic] ?’“ To which Napoleon exclaimed:” ‘One would think it was he who commanded the army.’“ Nor did his enemies stop short at this point. Once they realized they had the Emperor’s attention they launched a full scale attack on the absent Marshal. “ ‘Was it not Davoust [sic] who, after the victory of Jena, drew the emperor into Poland ? Is it not he who is now anxious for this new Polish war ? - He who already possesses such large property in that country, whose accurate and severe probity has won over the Poles, and who is suspected of aspiring to their throne ?’“

Thus is was that doubt was sown in the Emperor’s mind; doubt which was to deprive him of the advice and counsel of one of his best tactical commanders. One cannot be sure that it was pride and selfishness, as is implied by Davout’s apologists, which drove the wedge between the Marshal and his Emperor. But there is no question of Napoleon’s jealousy of his military glory. His reluctance to share with Davout their conquest of the Prussian army in the autumn of 1806, his refusal to grant Marshal Soult the title Duke of Austerlitz, gives evidence of Napoleon’s covetousness of these great victories. The conquest of Russia was to be his greatest military triumph. Davout was but one commander, one of his best to be sure - but nevertheless, merely one of many cogs in his war machine. Napoleon himself was quick to admit that his domination of Europe, and France itself, was based on his military achievements and reputation. He was in need of good generals, but he could not tolerate a rival within his own camp.

John G. Gallaher - The Iron Marshal, a Biography of Louis Nicolas Davout.

See: Comte P. de Ségur, History of the Expedition to Russia Undertaken by the Emperor Napoleon in the Year 1812. Gallaher advises us to read Ségur with caution, “as he is not always historically accurate”.

#napoleonic#john g. gallaher#the iron marshal: a biography of louis nicolas davout#louis nicolas davout#campaign of russia#it's such a mess

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Comte de Ségur, Jacques-Louis David, 1805-1824, Harvard Art Museums: Drawings

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop

Size: 21 x 16.4 cm (8 1/4 x 6 7/16 in.)

Medium: Black crayon, squared in black crayon, on off-white antique laid paper

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/190553

1 note

·

View note

Note

are there any anecdotes about angry lafayette?

I’m away from my books at the moment due to a COVID related incident (precautionary only) so take this with a grain of salt. BUT from what I remember, there was a time when Lafayette was very young--prior to going to America young--where he heard through the grapevine that his friend, the Comte de Ségur, had won the affections of a lady he’d fallen in love with. Ségur had no idea. Instead of checking his sources, Lafayette literally got up in the middle of the night, took a sword, busted into his pal’s room, and challenged him to a duel. According to the Comte, it took nearly all night to talk Lafayette down from the fight and restore their friendship. But Gilbert came in HOT. The story is pretty hilarious, but is unfortunately marred by the fact that, if I’m not mistaken, he was a newly wed at the time.

That’s what happens when you’re a punk kid and only one of you married for love. If you’re interested in learning more about the complicated, fascinating relationship between Lafayette and his lovely wife Adrienne, search her name on my blog.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Grand Master of Ceremonies, Louis-Philippe de Ségur, Comte of the Empire

THE GRAND MASTER OF CEREMONIES

Louis-Philippe de Ségur, Comte of the Empire

The comte Louis-Philippe de Ségur was Grand Master of the Ceremonies of the Imperial Household from 1804 until the fall in 1815. This Grand Officer "performs two different kinds of functions: the ceremonies and the introduction of the Ambassadors...He writes and signs the protocol [and] dictates the costumes in which those invited must appear...The day of the ceremony, [he] makes sure that all the parts of the protocol are properly adhered to; during the ceremony, he stands in front, close to H.M." The Grand Master gives orders to the masters of Ceremonies, with the help of the assistants of Ceremonies and heralds, and he also relies on a dessinateur of Ceremonies (a position entrusted to the painter Jean-Baptiste Isabey, charged with giving shape to and decorating ceremonial spaces and the costumes) and a coach of Ceremonies.

Ségur was the son of Philippe Henri, marquis de Ségur, marshal of France and minister of war under Louis XVI. From the aristocracy of the Ancien Régime, he was well acquainted with the customs of the court at Versailles. It would be wrong, however, to see him only as an old courtier, concerned soley with preserving the conventions and details of etiquette from one regime to the next. Indeed, his fascinating career represents all of the rich intellectual and liberal identity of nobles in that generation of Frenchmen, born under Louis XV only to find themselves facing the civic and social challenges of the late eighteenth century. His presence at Napoleon's side takes on a particular importance.

A Freemason, in his youth he supported the independence of the United States and fought on American soil, returning in 1783 with the rank of colonel of dragoons. He was then sent by Louis XVI as ambassador to Russia (1784-89), where he earned the friendship of Catherine the Great. A believer in the Revolution, he was appointed ambassador to the Holy See, but the pope refused him entry into the Papal States. He received the same treatment by the king of Prussia, to whom a discredited France had sent him in January 1792. Returning to France, he retired to his estates in Chatenay, where he prudently remained during the most dangerous years of the Revolution. Bonaparte's rise to power won him over. A member of the Legislative Corps in 1801, and then a member of the Council of State, he was appointed Grand Master of Ceremonies with the advent of the Empire. Created a comte of the Empire in 1808, he joined the Senate in 1813. Ségur sided with Louis XVIII in 1814, and then went back to Napoleon during the Hundred Days, even offering to follow him into exile after Waterloo. In the end, he stayed in France. He fell from grace during the early years of the Restoration, but regained his seat in the Senate in 1819. He died in 1830, a few weeks after the liberal revolution to the July Monarchy.

Excited by the new ideas of his age, Ségur was a born historian who loved philosophy and literature and frequented the salons of Mme Du Deffand and Mme Geoffrin, meeting La Hapre, Marmontel and Voltaire. He produced numerous works of history and political science, as well as plays, short stories and songs, and his admirable Mémories, on the first part of his life up to the Revolution, all of which are still extant. This dense text reveals the depth of his thinking and his strong belief in the Enlightenment. He was elected to the Académie francaise in 1803. His literary output was interrupted under the Empire, but he took it up again under the Restoration, notably publishing Abrégé de l'histoire universelle in forty four volumes (1817), a Histoire de France in nine volumes (1824) and Histoire des Juifs (1827). As an enlightened historian, he was admirably suited to carry out the functions of a Grand Master of Ceremonies, for which historical research was often necessary. In order to reconstitute a coherent and relevant etiquette for the court, he delved into the archives of the royal palace and memories of the courts of Europe.

The half-length portrait of Ségur from the Chateau de Versailles is a work that requires careful study. It is important to note that the original commissioned by the Imperial Household for the Gallery of Grand Officers, was in fact a full-length portrait. Is this a copy, a replica or actually the original cut down? The original was commissioned from Marie-Guillemine Benoist and executed during the year 1806. It was in the Tuileries, hanging in the Gallery of Diana in August 1807, and then at Compiegne, in the Salon of Ushers in May 1808. On February 13, 1814, it was sent to the Louvre, like the other paintings. Was it then, under the Restoration, given to the sitter's family, as was the case with most of the other portraits of the Grand Officers? This is probable, and would support the hypothesis that it was this canvas, as it has been kept at Versailles since 1924, given by the Ségur family.

The Grand Master is standing in front of a heavy curtain that offers a narrow glimpse of a distant horizon. He appears to be holding his ceremonial staff, which tempts us to compare the composition to the portrait of Duroc, Grand Marshal of the Palace, by Gros.

It is no great surprise that it was this portrait-of himself-that Ségur had copied by Isabey, his artist of Ceremonies, to represent the figure of a Grand Officer of the Household in the Livre du Sacre, a publication he authored. In 1810, Goubaud, in his turn, made use of it to depict Ségur carrying out his duties in Napoleon Recieving the Delegation from the Roman Senate in the Throne Room of the Tuileries.

Napoleon, The Imperial Household, Sylvain Cordier, Montreal Museum of the Arts, page 48

Ségur Portrait: Artist Unknown, possible Benoist.

Goubaud’s, Napoleon Receiving the Delegation of the Roman Senate in the Throne Room at the Tuileries

#napoleon#bonaparte#Napoleon Bonaparte#Emperor Napoleon#Emperor Napoleon Ier#Emperor Napoleon I#Napoleon I#Napoleon Ier#imperial household#book exerpt#First Empire#Ségur#Segur#Louis Philippe Segur#Louis Philippe Ségur#Grand Master of Ceremonies

7 notes

·

View notes