#edc534

Text

High School Never Ends: Manifesto (Strategies, Goals & Process)

My goal in writing my essay was to fully thrust myself down a rabbit hole of thought. Emboldened with more questions into human nature than anything else, I found myself preoccupied with just what makes us hit that post button. What is the real significance of all this digital “sharing?”

Social media, blogs and other other free and available media outlets have created a universal platform for all people who choose to engage online. Sharing recipes on a Facebook wall, writing a personal blog, recording videos or podcasts or developing a form of activism all are inevitably tied to a certain level of popularity or active seeking of popularity. While the sentiments of people wanting to be noticed or have their work noticed in some way may have always existed, the free and open internet as it exists today has really elevated these sentiments to much higher levels.

Everything is hyper-paced and universally available around the clock. One cannot escape the pull of social media and it has become a parallel dimension to our three dimensional world. My goals in this essay and social experiment project were to seek out and provide empirical evidence that digital authorship is nothing more than a deeply rooted desire to belong. It is a call to anyone who will listen that we are here to create and those creations need validation.

This essay was designed dig deeper into the nature of social media and digital authorship. With so many free creative outlets and platforms for “sharing,” I believe people have an inflated stake in these platforms to contribute and actively monitor just how important their post (in a broad sense) are. The opportunity here is explore what does creatively engaging on the internet (for any multitude of purposes) bring to us intrinsically by broadcasting so much extrinsically? If people are moved to share for the sake of monitoring who is seeing or supporting or opposing what they do, what will the new nature of authorship be? What are the varying degrees of authorship from one “like” to millions of followers? Are we actively community building by sharing? What does the ability to show support or rallying around a cause really say?

My essay seeks to connect research of scholarly work to a more personal take on what content (created, remixed or re-shared) generates the most feedback and what psychological effects are produced by sharing and subscribing to different kinds of content in a public display. Is the online-self nothing more than a fashion statement? Or is it something real?

The work process for this paper was devoted to searching for sources and constructing a social experiment to implement as a creative component to a this kind of meta-authorship. As I explored popularity as the root of all digital authorship, I myself had to embark on numerous elements of digital authorship that, in themselves, explored the very validation I wanted to nail down as the end-point of any public decision to post online.

From the selfie to the scholarly article, we are on desperate, far-reaching searches for connection, community and validation that what we create is worth the time of others and that what we do with our time is worthwhile. This validation is now instantaneously at our fingertips and as a result we have become followers of the very things we create.

The essay is for educators who foster authorship and for people who actively engage online in any capacity and to any end. The goal of the research and essay is to explore the nature of authorship in the context of popularity and self-branding. When we have students put work onto a blog or create a podcast there is the unspoken (or perhaps spoken) notion that people will hear this, it’s out there.

By being “out there” with our work are we just preparing our students to seek approval or recognition? Does sharing something point to a need for acceptance or validation? Does creating or liking a "activist" page show an intrinsic desire for social change or is it an extrinsic symbol? Nothing more than an advertisement of one's identity?

In an unexpected turn of events, I found myself exiting the rabbit hole in an unexpected space of wondering where the nature of authorship will go next. I have spent so much time thinking of where authorship stands today as a destination, that it only dawned on me in conclusion that our posts are threads in the very fabric of the young Internet itself. Each element we “share” is another stitch into something larger and as yet unrealized.

0 notes

Text

High School Never Ends: A Social Experiment

As a component to my project, I also conducted a short social experiment analyzing a variety of publications posted on Facebook in a one-hour span of time. After a week, I analyzed the posts and the conversations within posts in an attempt to compare levels of engagement on the posts. In short, I sought to discover what kind of post was “most popular?”

You may find a link to the slide presentation here. It is a compilation of my research.

Conclusions:

What becomes abundantly clear from this variety of post, at least in the circle of amassed “friends” I have on Facebook is that the more likes went to the more relatable posts showing expressions of cuteness, humor or personal triumph. The post of the grad-school meme, my dog and the Rhode Island Press Award post all generated not only the most likes, but also a healthy interaction in the comments and interaction within those comments.

It was found in this social experiment that it did not take much for a post to feel even somewhat validated. A single like offered some degree of someone’s out there connection, but those feelings were greatly amplified when a post generated more likes and public back-and-forth.

The posts I chose to publish and research represented middle-of-the-road posts that most people might make on a daily basis. No matter what the content of the post, a common factor was a desire for reaction and social interaction celebrating or acknowledging what I took the time to post. The sharing of the “How Fast We Buy a Gun” video was shared with no commentary from me. It received no “likes” and no comments. Maybe no one wanted to open a can of worms. I tend to think that people are more apt to assign validation if there is a level of buy in from the author. It seems that people gravitate towards the more earnest or funny posts.

Finally, this social experiment illustrates that the feeling of validation from people for something we create always feels better than nothing. A published work collecting dust is nowhere near as fulfilling as the outpouring of support and adoration for a cute puppy picture.

While the outward seeking of such validation and “popularity” is not inherently bad, it does tend to boil down most of our engagements to a base, almost instinctual gravitation towards recognition seeking. It makes one wonder if social media and the way we engage on it was meant for something more. Does digital authorship need be validated to hold significance?

0 notes

Text

High School Never Ends: Popularity and Engagement in the Digital Age

Everyone wants to be popular.

While this sentiment might not be outwardly expressed by many or overtly apparent in everyday life, there exists a deep-seeded need for validation and recognition. In the digital age (arguably starting with the first AOL Instant Messenger screen-names, MySpace profiles and Livejournal sites) this outward, public seeking of validation and approval has been at the core of every endeavor undertaken in the digital world of self-broadcasting, self-publishing and community entertainment.

Whether outwardly apparent to the post-er or not, every status update, photo upload, blog, vlog, reshare or creative work is a shared and curated element of self-promotion and self-branding that speaks to a need to control how people see who we are and recognize the things we stand for, create or “share.” Likes, comments, re-blogs and re-shares all amount to a point system, a personal catalog of validation that works like a checkbook ledger crediting and debiting the appeal of the creator.

People, hyper-aware of ideas on the spectrum of “going viral” to “trolling” post with total awareness of the weight they carry in the online sphere. Everything one “shares” is at its core a maintenance of an online persona, a way to lure people to think a-like or challenge people to debate with the intent of bringing attention to the very thing that was publicly created.

To exist on social media, in any capacity and on any medium, speaks to a personal need to be popular, accepted, validated and recognized.

Thus, I would like to focus on three key areas of 1.) personal creativity in a “friends” context, 2.) public personal creativity (blogs, vlogs, podcasts and websites) and 3.) activism to examine how public viewing, critiquing and collaboration have made virtually all forms of interaction on the media, at some level, an amplification of personal desires for popularity, acknowledgement and relevance.

I will attempt to articulate a unified nature to why we post what we post. What are we looking for in our digital authorship and will it ever be realized? Does our personal digital authorship have a point? Does our “shared” authorship matter if everyone’s an author? For what reasons does the “social media self” exist? Is there such a thing as post-popularity authorship?

Part I: Selfie

The selfie has become the poster-child for our digital times.

The sole-creator, sole-subject of a picture looks to show in the most blatant of ways, what “I” am doing. Check this out. While the selfie is not something everyone partakes in regularly while at the gym, at scenic locales or simply to show something unmissable in the moment, it does serve as a good starting point for the larger discussion of the role of popularity in social media. The selfie is a metaphor of the digital author in any form (including the selfie itself!).

In their paper Narcissism 2.0! Would narcissists follow fellow narcissists on Instagram?” the mediating effects of narcissists personality similarity and envy, and the moderating effects of popularity, Jin and Muqaddam (2018) point to a level of narcissism associated with and attached to selfie takers. They write that “selfies allow individuals to manipulate the angle of the shot, to be at the center of the frame, and to make certain poses and facial expressions that reflect the personality they wish to communicate. Social networking sites like Instagram and Snapchat provide filters that improve the quality of the image and digitally enhance the face by hiding skin-spots and controlling brightness. Hence, when social media audiences judge images where the source is self-centered, they naturally associate this self promotion with narcissism (Lee & Sung, 2016) and therefore perceive selfies as narcissistic behaviors (Re et al., 2016)” (Jin & Muqaddam 2018, p. 32). While the selfie remains one of the more obvious and self-centered forms of self-promotion on social media, the intent of the selfie is the same core intent that drives any singular post someone might make. It is a desire to outwardly “share” something with the expected viewership and feedback of a community in return.

Digital authorship, in all forms, is simply different reiterations of the selfie. The word count or perceived merits of “high-brow” creativity or the simplicity of the re-share does not take away from the core purpose of the piece of authorship: It is a way to be noticed and to reach a perceived audience.

Part II: Yourself, personally curated

Like a perfectly staged selfie of profile picture, how one portrays themself online through the things he or she shares speaks to the unique ability to self-create and self-curate our own online perceptions. Kurt Vonnegut once wrote, “We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful what we pretend to be.” This has never been more true than in our digital age and in regards to the task of personal digital authorship.

The act of wording a Tweet or choosing a recipe to share or choosing a cause to “like” all stems from the intrinsic knowledge that this information will be seen. The online persona is a sum of its digitally authored parts and it is responsive to the input of other digital authors.

Essentially, digital authors are in constant flux, tweaking, branding and altering digital personas to appeal to approval or recognition from online communities. The digital self is not static, it is constantly malleable to changing trends and events. In their study of different types of Facebook profile pictures, Wu, Chang and Yuan (2015) point out that “people use the internet to explore themselves. That everyone has two different entities; ‘true’ self and ‘actual’ self have been proposed before (McKenna, 2007). The user is highly motivated to project himself in the best possible way in the virtual world (Emmons, 1987)” (Wu, Chang & Yuan 2015, p. 881). This differentiation between the “true” and “actual” self speaks directly to Vonnegut’s “pretend to be” self. The words “true” and “actual” could just as easily be replaced with “digital” and “real-world” self and with that we could even branch those selves further!

Joachim Vogt Isaksen (2013) writes that a “person’s construction of an ‘imagined self-image’ is done unintentionally. We are not consciously aware that we often try to conform to the image that we imagine other people expect from us” (Isaksen 2013). One mirrors what he or she thinks will be acceptable to others and creates a version of themself accordingly.

To consider what elements of digital authorship show about our “best possible projections” is to consider the implications for our choices of what we show. It is worth noting, how absorbing the digitally authored, online self can be. Even in the midst of navigating real-world situations, the parallel Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, blog or other social platform sits ready to show new forms of validation for something shared. Who hasn’t scrolled through Twitter on the subway? To post a photo is not just to post a photo. To post a photo is to monitor the popularity of that photo in real time. What is the fallout from that photo? What is the impact of that photo? When does following analytics for a given photo cease being something worth looking at a smartphone for?

Isaksen (2013) points to American sociologist Charles Horton Cooley when he asserts, “[the] looking glass self, states that a person’s self grows out of a person’s social interactions with others. The view of ourselves comes from the contemplation of personal qualities and impressions of how others perceive us. Actually, how we see ourselves does not come from who we really are, but rather from how we believe others see us” (Isaksen 2013). With Cooley speaking to us from the turn of the 20th Century, it is easy to see how this idea of “self-image” has become hyper-edited and hyper-curated in the digital age.

While in person one might mimic body language subconsciously to gain someone’s favor, the world of back-and-forth digital authorship has allowed people to spend time and put great care into the maintenance of exactly who they are through their authorship. Shows such as MTV’s Catfish are built on the whole premise of people completely mirroring to the point of assuming someone else’s identity just for the sake of validation.

A post is more than a post, it’s an established ecosystem.

The point is not about the post. The significance lies in the life that takes shape around the post. The discussion or feedback or “virality” of the post is more important than the post itself. It is the cosmos that forms surrounding the post that gives the author meaning, feelings of validation and a reason to continue engaging. The post, no matter what it was, gave life to something.

That’s creationism.

Part III: You be an author while I be an author.

To be a digital author is to engage in “correspondent authorship.”

The act of writing a post and then responding with a gif is a case in point of back-and-forth authorship. While a face-to-face conversation is built around the moment, social cues, pragmatics, situations, visual and auditory stimuli; the act of being a digital author allows for wait time between interaction. In this way, the only way to respond to one’s online publication, even one so simple as “Love shopping at Aldi!” (Who’s my audience with that line? Why’d I say Aldi? The irony!) would be met with a considered and measure expression in return. The act of even considering whether to “like” a post carries with it the weight of realizing that the “like” will be seen by the author and that the “like” stands for something.

That “like” stands for a person and everyone can see who they are, everyone can think about why they “like” it and everyone can judge them.

Correspondent authorship, even between “friends” on Facebook is public domain. This is a central idea to the popularity drive behind every social media interaction. Companies like Facebook, Twitter or Tumblr afford the user a free service and all-important “wait-time” to express themselves. The promise of millions of other users having access to view and consume what we say or do, whether that many people actually engage with our published material, is enough to give everything we post, say or articulate a literal “pause.” Ranney (2015) writes that “the ability to control the dissemination of information and monitor self-representation in digital contexts helps individuals develop positive impressions among others and cultivate the esteem of their peers (Walther, 2011). Thus, information and communication technologies facilitate social and emotional adjustment by encouraging individuals to be more careful and deliberative in their digital interactions and behaviors than they are in their face-to-face interactions” (Ranney 2015, p. 4). This act of being “careful,” the momentary finger-hover over the enter key is our brain working not as a conversationalist, but rather as creator, editor and publisher of our own persona, hyper-aware of how the thoughts put to publication might play out.

And that’s just in the person-to-person interactions!

The things we choose to post and the multitude of other posted fragments, whether it be a Pinterest board or Instagram feed or news site with attention grabbing headlines, all feed into our ambient awareness. According to Levordashka and Utz (2016), “Ambient awareness can be defined as awareness of social others, arising from the frequent reception of fragmented personal information, such as status updates and various digital footprints, while browsing social media. “Ambient” emphasizes the idea that the awareness develops peripherally, not through deliberately attending to information, but rather as an artifact of social media activity” (Levordashka and Utz 2016, p. 147). The act of mindlessly scrolling through Instagram after a long day of work is actively working to develop ambient awareness of tens or perhaps dozens of people mathematically chosen to appear for one’s viewing pleasure. This ambient awareness informs us of trends, events or ideas worth further investigating, engaging with or forgetting about.

If enough people post about something, it’s going to get noticed.

In their study of “ambient awareness” on social media platforms, Levordashka and Utz (2016) used questionnaires to assess the extent to which people became aware of information in their networks just by browsing through a Twitter feed. Levordashka and Utz (2016) wrote the “results of this study show that people experience a sense of ambient awareness towards their online network. More importantly, they were able to recognize and report information about individual people in their network, whom they know only through the microblogging platform Twitter” (Levordashka and Utz 2016, p. 150).

Just as we have become accustomed to “scanning” for information, so too has our awareness of our social, political and professional circles become crowd-sourced. To just browse through what friends are posting on Facebook on a given night offers not just close friends, but acquaintances, ads and other algorithmically driven sponsored content based on the things we choose to publish. Thus, our acts of authorship are motivated to determine what social, political or professional circles we both see and pop up in.

Levordashka and Utz (2016) go on to conclude,“We demonstrate that browsing social media and frequently encountering various social information allows social media users to gain awareness of what is going on in the lives of people in their online network” (Levordashka and Utz 2016, p. 154). To engage on social media as an author and as an author on someone else’s authorship is further created in the context of being watched in a “fishbowl” so to speak. To engage on social media is part creation, part mathematical equation and part right-place-at-the-right-time all stemming from the initial desire to be noticed.

Whereas in person one must cultivate who they are in a fully dimensional way (emotionally, socially, physically), the digital world has been left as a place to write, edit and re-edit our memoirs in real time, see who’s reading it in depth and be intrinsically aware of the many others “window shopping.”

Part IV: Social Activism…there’s a brand for that

Social media has made social activism click-friendly.

To be an activist does not require physical action only intellectual action and a willingness to be vocal. In this way, activism in social media circles is kind of like comparing bumper stickers. There is a certain awareness that a “like” to an organization, whether it is Black Lives Matter, the National Rifle Association or Greenpeace, proclaims publically what one stands for.

Furthermore, to be an activist on a platform like Facebook, to “like” a page, offers a scroll bar of like-minded organizations, all with the same goal in mind, more likes and more clout that translates to more “likes” for the liker from the kind of people they want “liking” their posts.

Fichter and Avery (2012) write, “Having power and influence, making the things you advocate happen: This is the essence of clout. Does clout matter? Yes. On different issues, at different times and for different reasons, everyone wants their voices to be heard and their points of view acted upon, or at least understood, acknowledged and validated in some manner” (Fichter & Avery 2012, p. 58). This idea of clout puts community, social, political and grassroots organizations into the interesting space of brand management in order to achieve change. At some point, maybe around 10k “likes,” an organization enters a space of brand recognition that affords it the ability to market itself to people as a kind of “badge of honor.” Social movements become a way to express oneself without showing anything more than a copyrighted title and font.

In many ways, this appeal to broad popularity in a social media platform (soft activism) becomes a gateway to more concrete forms of activism such as giving money, protesting or voting (hard activism). In a study done on whether civic activism online made young people dormant or more active in real life, Milošević-Đorđević and Žeželj (2017) found that “when tailoring policies to

engage young people in civic activities, one has to have in mind different platforms and different topics; making them engaged in one type of activity makes it more probable that they would engage in others, making them engage in “soft activities” makes it more probable that they would engage in “hard activities” (Milošević-Đorđević and Žeželj 2017, p. 118). Therefore, it becomes essential for an organization to develop brand appeal and clout through activism and a key way to do this is to stand for something that people can show publically and let it, in turn, stand for who they are.

A drawback to the click “like” approach to activism lies in the “browser” nature of how we consume information online. To get into the nitty-gritty details is simply not something everyone has time for, so to “like” something one stands for places a level of trust in the organization to promote an imagine that maintains the cultivated imagine one hopes to achieve by advertising their “like” for that organization.

Ranney and Troop (2015) explore how this at-a-distance approach to social interaction leads to disconnection when they point out that “information and communication technologies (ICTs) limit the number of non-verbal social cues available during social interactions (i.e., facial expressions, vocal inflections, body language; Lee, 2004; Tanis & Postmes, 2003; Walther, 2011), which in turn reduces the total amount of observed information that is exchanged during interactions. The consequence is that ICTs may reduce the total amount of information exchanged, including the ability to convey one’s emotions, revisit topics, and discuss topics in detail” (Ranney & Troop 2015, p. 64). This lack of information exchanged directly correlates to the Trump-era we find ourselves in. The “like” of something Facebook recommends we like or the “follow” we give to someone Twitter says we should follow supplants the way one explains themselves, relying instead on social crutches to explain their views or personality for them through shares or re-tweets.

In 2016 people could go online and like a page proclaiming, “Make America Great Again,” they could buy a red hat and wear it and in those few words, so much could be said. Was it a movement? A feeling? A trend?

Whatever it was, people could share it, their “friends” could “like” it and their views were validated. The kicker was when those “likes” turned into mobile votes.

Instances such as this, mass movements based on catch-phrases and gut-impulses, is a natural conclusion to an online, social culture based on self-promotion, fast, bountiful information and limited time to consume or articulate stances, viewpoints or feelings. There lacks a need to explain one’s post if it is someone else doing the explaining. The digital author simply gets the credit for sharing, not articulating and the greater the ecosystem of engagement created, the greater the success.

If something feels right, why not share it and see who reciprocates those feelings?

Part V: Moving On

As an avid digital author in numerous forms myself, it is unclear whether there is a remedy to the popularity driven social authorship or whether there even needs to be a remedy. In essence, is being driven by popularity wrong? The moral implications of why we engage on social media aside, it can be asserted with confidence that the vast majority of our social, digital authorship through personal posts, blogs, vlogs, podcasts or other forms of creative publication is driven by a need for validation within a community or by a more open-public audience.

Validation in the form of debate-seeking trolls or likes or upvotes all add to a subconscious (or conscious!) tally of who sees our stuff, who likes it and who values its creation in the first place.

In short, we are a large part of each other’s entertainment, so we’d better have evidence that we are entertaining!

Ranney (2017) in his study of adolescent social interaction on the internet as a means to maintain social hierarchies, points to the growing influence of digital societies on social interaction. Ranney notes that “socialization through information and communication technology (ICTs) is so pervasive that, compared to 35% adolescents who report socializing face-to-face outside of school, 63% of adolescents text their friends daily, 39% talk with friends on cell phones, 29% message friends through social networks, 22% communicate through instant messaging, and 6% email their friends daily (Lenhart, 2012). Although time spent in school and in-person gatherings with friends remain important for adolescents’ social and emotional well-being, a majority of the social interactions that peers have with one another during adolescence is currently taking place in digitally mediated contexts” (Ranney 2015, p. 2). This time spent in digital social circles points to a need to fully understand and embrace what drives acts of digital authorship, come to terms with the underlying reason people are engaging online and decide whether “online” is ever meant for something bigger; driven by creations that are less self-serving.

Despite researching adolescents, I would not expect an adult sample to look much different in terms of time spent in digital realms. An adolescent posting about secret levels in a computer game and a middle aged man posting a cat meme are both driven to publish material for the same reasons; recognition and validation. It’s almost like a mantra.

Thus, as with anything else, attention is the catalyst for what one chooses to do. Where we place our attention is where we place value and seek to find quality.

Tiffany Shlain (2017) points out that “attention is the mind’s greatest resource”. She goes on to picture “the Internet, like the developing brain of a child…in a rapid phase of growth and change” (Shlain 2017). Like a small child, countless synapses are forming as the Internet grows in real time. More than being just “along for the ride,” we are active builders in the unseen and unrealized scope of what the Internet will become. Our acts of digital authorship, while being currently driven by popularity as a catalyst to create might need to become something more empathetic or humble if we hope to see social media and digital platforms become more altruistic than they appear to be. If Facebook’s recent rebrand as something “pure” has shown us anything, it seems we might be turning a small corner towards seeing social media in a different light.

There’s more to all of this than just “sharing” in different forms. I’m sure of it.

“This means that just as we must be mindful in how we nurture our children’s minds,” Shlain notes, “we must also pay careful attention to how we develop our global brain” (Shlain 2017). Our information and our authorship is shared content in the public domain. No matter what the privacy settings, someone else has access to it. It is a building block. It might feel insignificant or goofy or even useless and futile, but it is valuable information that informs a larger design. With the role of “builder” rather than “user” in mind, one can begin to envision a larger calling in the name of global consciousness and motivation behind digital authorship. One begins to not just be a personal creator, but a contributing creator. One is part of a larger one.

On the other hand, maybe a good, well-timed meme is as good as it gets.

Resources

Fichter, D. d., & Avery, C. c. (2012). Tools of Influence: Strategic Use of Social Media. Online, 36(4), 58–60.

Isaksen, Joachim Vogt. (2013). The Looking Glass Self: How Our Self-image is Shaped by Society. Retrieved April 17, 2018, from http://www.popularsocialscience.com/2013/05/27/the-looking-glass-self-how-our-self-image-is-shaped-by-society/

Jin, S. v., & Muqaddam, A. m. (2018). “Narcissism 2.0! Would narcissists follow fellow narcissists on Instagram?” the mediating effects of narcissists personality similarity and envy, and the moderating effects of popularity. Computers In Human Behavior, 8131–41.

Levordashka, A. a., & Utz, S. s. (2016). Ambient awareness: From random noise to digital closeness in online social networks. Computers In Human Behavior, 60147–154.

Milošević-Đorđević, J. J., & Žeželj, I. z. (2017). Civic activism online: Making young people dormant or more active in real life?. Computers In Human Behavior, 70113–118.

Ranney, J. D. (2015). Popular in the digital age: Self-monitoring, aggression, and prosocial behaviors in digital contexts and their associations with popularity (Doctoral dissertation, North Dakota State University).

Ranney, J.D., & Troop-Gordon, W. (2015). Problem discussions in digital contexts: The impact of information and communication technologies on emotional experiences and feelings of closeness toward friends. Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 64–74.

Shlain, T. (2017). How The Internet Is Like A Child’s Brain. Retrieved April 17, 2018, from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/brain-power-film-and-ted-book_b_2083785.html

Wu, Y. w., Chang, W. i., & Yuan, C. d. (2015). Do Facebook profile pictures reflect user’s personality?. Computers In Human Behavior, 51880–889.

#edc534#selfie#long reads#essay#philosophy#education#media#digital#Digital Literacy#computer#social media

0 notes

Text

Facebook Owns You

This article was published on Mic back in 2013. It popped into my head recently.

Adam Hogue

| June 25, 2013

You can walk away for a year, two years, live out in a shack in the woods but there will come a day where you find yourself wanting to check back to Facebook.

No one can stay away for long. This is how we live now.

At least, that’s the general consensus a number of “living without internet” experiments have arrived at. The internet, namely social media, is something that we have bought into in a big way and there is little hope of escaping its gravitational pull. In three words, Facebook owns you (and will sell you).

Our society is becoming increasingly invested in our social media, to the point that we are finally wondering when the pendulum will swing back. Some are arguing that social media is already in decline with younger generations looking to return to simpler, pre-status days where eye-contact on the street and tag-free photos were the norm. But, it is unclear whether such a “disconnect” is possible. In a sense, we are in The Matrix already.

Over the past year, a few stories have turned up from notable writers that explored “unplugging.” While each story offers a different perspective on stepping back from being a “plugged in” 20-40 something, they all share a similar fate in the end. All of the writers could not stay away from the technology they grew with, while cutting back was feasible, a complete disconnect was impossible to sustain.

Let’s start with the case of The Verge’s Paul Miller.

Miller was paid by The Verge to leave the internet cold turkey for a full year. No internet at all. Initially, Miller felt his quality of life get better. His attention span increased, he could read hundreds of pages of Greek literature in a single sitting, he was having better conversation and he was more attuned to maintaining relationships. But, over time, that zeal of life faltered and eventually he was back in the same pitfalls that he had once blamed on the internet.

He realized the internet was not something that distracted from “reality.” The internet and the way we connect is our reality. It’s our world now, take it or take it.

A year later, the internet didn’t seem so bad.

But, while the internet might be the reality we live in. There are certainly levels to the extent in which we engage. For instance, I’m a one tweet, one status a day, one essay a week guy. I read my news online, but otherwise, I don’t find an intrinsic satisfaction loitering online. Granted, I don’t yet have a job that demands I do…yet. But, in the case of writers (writers much more famous than me) the internet is a life-blood. It is the source of promotion, connection with fans, and maintaining a brand. It’s the way the business works.

In my freshman year at Keene State College, I watched Baratunde Thurston of The Onion perform stand-up, shortly thereafter I began to follow him on Twitter and I have been amazed ever since at the level of tweeting one person is capable of. These days he is the bestselling author of How to be Black. He is also a prime-example of what I would call a “plugged-in” person. What started as a need to promote and engage, became an unweeded garden of social networks, applications and general keeping up in a little bit of everything.

But, not too long ago, Baratunde took a slightly lighter, but still bold month away from the internet for the sake of his sanity and he wrote a great essay about it. While the Miller experiment ended in him coming full circle, realizing the internet does not change the person, Thurston arrived at a much more light-hearted, optimistic view of his break. He noticed the world more, he was unafraid to try restaurants on sight alone and he found himself in a state of freedom from those things he once felt obligated to contribute to.

Suddenly, not tweeting made him not care if people were reading what he said or not. This is a feeling that anyone who has taken even just a few extended days away from Facebook is no stranger to. If you don’t think about it, it doesn’t matter anymore. He was engaged in a living environment for a change.

But, ultimately, he knew he had to eventually return.

We find ourselves in a plugged-in world whether we truly enjoy it or not. Perhaps a Facebook friendship is not a substitute for a person-to-person friendship; but it is what we have created and cultivated. With our social media we have the ability to be ever-present to everyone, but at the cost of being truly present to the few people around us.

A final case to consider of severing all internet ties concerns only Facebook. Katherine Losse was an employee of Facebook who was one of the few women with a liberal arts degree to make it so far up the ladder (for a while she was Mark Zuckerberg’s personal ghostwriter).

In a piece by Craig Timberg for The Washington Post in August 2012 (is that too out of date for our internet age?) we meet Losse in the town of Marfa, Texas. She is physically cut off from the world, her Facebook is deactivated and she is working on a book. She argues that Facebook is playing in very “touchy territory” with the vast amounts of information they and other social media store.

The fact that we actively and willingly trust our information to these free servers and then demand our privacy or feel betrayed when we find out this information is being accessed and stored by people other than ourselves is reason enough to feel that a great social media walk-out should almost be guaranteed in the future. It is this trade-off that led Losse away, out of the Silicon Valley, to a trailer in West Texas.

But, like all the other post-Walden “unplug-gers,” Losse now finds herself, reluctantly, back on Facebook as a means to promote her brand. Like the rest of us, she’s in the make it big or die-trying youth of life and the internet is the only frontier people are paying attention to.

We’ll always come back to our social media.

In a bit of an ironic twist, I posed the question, “Any thoughts on leaving social networks?” as my Facebook status for this article. The response falls in line largely with those that tried to disconnect above. It is a varied and objective field. For most, Facebook and social media is a lifeline for engaging, learning, business, connection and promoting. It is not perfect, but it is a reality. It is a curated diary that will survive longer than we ever will on this Earth.

Whether we are ready to admit it or not, social media is a tangible part of our society. It is a world-wide nation that we have a personal stake in … our identity. To disconnect from social media or the internet as a whole is to erase one’s self from a part of society. However, there can still be be valuable lessons gained from moderation and even severely limiting one’s presence from social media platforms in exchange for simply an e-mail address.

Our information and the parts of ourselves we leave on the internet binds us to a 21st century facet of the world we live in. As I alluded to earlier, we are giving ourselves to social media for nothing, in exchange for feeling a sense of online connection that may or may not be genuine, but, as Paul Miller illustrated, is better than no connection at all.

As a collective, multi-generational, world entity we are deeply engaged in our social media. Our information is there and it is not going anywhere soon. Perhaps, in the future we will see the world of Facebook, Twitter, and blogs disappear; but that will take considerable time to undo.

For the time being, we are products of our social media and we will never be away for long.

With that being said, for a credible, well-versed source on 50 years disconnected from social media, talk to my dad.

It’s not so bad.

0 notes

Link

Feel free to enter the Padlet, listen to my reflection and contribute to the conversation yourself. I would love to here your thoughts in any medium (Padlet permitting) you choose.

What do places mean to you?

What’s a shared story?

How can memories be crowd-sourced?

#edc534#Digital Literacy#digital authorship#digital media lab#renee#hobbs#URI#podcast#reflection#padlet

0 notes

Text

Relax, This is Only a Remix

Somewhere in the ether an idea is born.

From some deep (or not so deep place) a creative impulse jets it’s way to the surface. Perhaps it’s a lesson plan idea or a line of a song or a manifesto waiting to be pounded out on the keyboard. Wherever that idea came from, it’s yours. It’s yours to create, yours to nourish, yours to contribute.

At its core, this is how I have come to interpret “fair use.” From somewhere an idea came, but, regardless of where it was born from, the genetic make-up of that idea is an imprint that is the sum of countless parts that are surely the copyrighted material of someone else’s bright idea.

So it goes.

While the idea of giving money and due credit to artists or creators or innovators and the protection of their intellectual property is a fundamental right, it is unrealistic to consider that every single utterance of said work must result in an infringement on the said property. The Media Education Lab (2008) defines fair use as “the right to use copyrighted material without permission or payment under some circumstances—especially when the cultural or social benefits of the use are predominant. It is a general right that applies even in situations where the law provides no specific authorization for the use in question—as it does for certain narrowly defined classroom activities” (Media Education Lab 2008, p. 1).

In essence, ideas must be allowed to take shape unhindered by restriction as they will almost inevitably be built upon the material of other ideas. Aufderheide (2012) points to “the prizing of transformativeness (repurposing, not just re-use) as key to deciding fair use” (Aufderheide 2012, p. 6) and the confidence fair use can afford creators to pursue their ideas wherever they may lead and to whatever end is in sight.

Aufderheide (2012) goes on to explain that “Fair use applies to all of a copyright owner’s monopoly rights, including the owner’s right to control adaptation, distribution and performance. It applies across media (for example, music, video, print), and across platforms (analog, digital). Part of U.S. law for more than 150 years, and especially in recent decades, fair use has become a crucially important part of copyright policy. It is a core right; it is part of the basic package of freedom-of-speech rights available under the Constitution” (Aufderheide 2012, p. 7). To this end, fair use is an enabler of progress and process to create.

One might argue that no idea is truly original.

Indeed what someone like Joseph Campbell or Kirby Ferguson (2015) brings to light is the idea that archetypes and “remixes” of existing media begets new media or ideas advanced in a new direction.

Nods in film or music to familiar styles or even specific moments awakens something in the viewer or listener that can help them to see the point trying to be made. Ferguson (2015) titles his series on Vimeo “Everything is a Remix” and in the process of breaking down what makes something a remix must essentially remix and re-represent existing media to make his point. Does this make what he does infringement or unoriginal? Of course not. Ferguson (2015) using clips from J.J. Abrams to illustrate how J.J. Abrams is essentially a “remix” artist involved hours of sorting through and remixing J.J. Abram’s own “remixed” work in order to show how its a remix, juxtaposed with the remix of the “original” work Abram’s work is said to “remix” in the first place.

In order to point out that “everything is a remix,” Ferguson (2015) himself must rely on remixing himself to make his point thus proving his point through the act itself. Think Don DeLillo’s “most photographed barn in America” from White Noise. Everything is a picture of a picture that is already in our minds from somewhere.

The Media Education Lab (2008) notes that “copyright law does not exactly specify how to apply fair use, and that gives the fair use doctrine a flexibility that works to the advantage of users” (Media Education Lab 2008, p. 6). For someone like Ferguson (2015) or Abrams or Kanye West or any Youtuber to do what they do, this flexibility and murkiness of what exactly “fair use” specifically means lands the favor on the side of the creator and lays to rest what Aufderheide refers to as the “romantic notion of authorship.” That is, that the creator is the sole creator and sole-owner of their content.

So hands off!

Aufderheide writes, “filmmakers interviewed here also balanced the ‘Romantic ideal of the author’ with the realization that, at least for documentary filmmakers, new work that uses existing work is also creative and should be valued. The realization that the law did not merely permit but encourage the re-use of copyrighted work for the creation of new work, while a new idea for many, was an exciting one that challenged their surface assumptions about authorship” (Aufderheide 2012, p. 11). Thus, authorship is a give-and-take collaboration and with each new, almost certainly free contribution to the world wide web, that give-and-take collaboration and ability to chunk and rehash other people’s work for new hopefully ingenuitive purposes grows exponentially.

As long as the end is something altogether transformed, the ability to utilize the copyrighted work of others is free and fair game. The Media Education Lab (2008) points out that “despite longstanding myths, there are no cut-and-dried rules (such as 10 percent of the work being quoted, or 400 words of text, or two bars of music, or 10 seconds of video). Fair use is situational, and context is critical” (Media Education Lab 2008, p. 15). Thus, the idea that comes from the ether can be allowed to exist freely.

Just be ready to defend it.

Resources

Aufderheide, P. (2012). Creativity_Copyright_and_Authorship. In D. Gerstner & C. Chirs (Eds). Media authorship. New York: Routledge.

Ferguson, K. (2015). Everything is a Remix: The Force Awakens. YouTube.

Media Education Lab (2008). Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Media Literacy Education.

#edc534#university of rhode island#Digital Literacy#digital authorship#digital#copywrite#clarity#essay#long reads#fair use#renee#hobbs#digital media lab

0 notes

Text

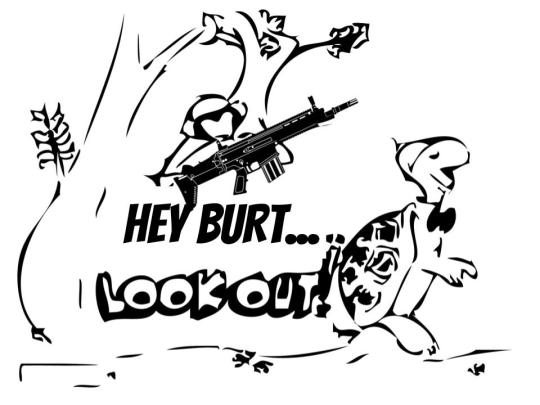

LEAP 2: Duck and Cover

The Atomic Age and the Cold War will forever be associated with duck and cover drills in schools. Students were instructed to crouch down and protect themselves from impending danger- collapsed roofs, flying debris, the inevitable results of an explosion. Luckily for American school children, their rehearsals were all in vain. The Cold War ended without ever becoming warm.

youtube

There is a war on American soil today. Mass gun violence has sparked a need for children to prepare, once again, for the worst.

My partner and I created these images to draw comparison between the Cold War era drills and the modern day lockdowns. It is absolutely unacceptable to us to think that our nation’s children face the daily threat of violence and death, as they have in times of foreign wars.

These images were created using Photoshop and Google Drawings. Our process began by searching for historical and more recent images using a Google Image search. Images were added to a shared Google folder. Historical images were selected in order to draw the comparison between nuclear war and mass gun violence. These images were copied and modified in Photoshop using the live tracing tool. Text was drafted in a shared Google document. Ultimately, my partner and I decided to annotate the original text that had captioned these images. We believed this would strengthen the comparison and represent the urgency of adopting lockdown procedures in schools while at the same time, revealing with a sense of irony that the more circumstances change, the more they stay the same.

By recycling, manipulating and annotating existing digital media from a bygone era, we attempt to reveal the seemingly contradictory ideas that these drills are both necessary to perform and, at the same time, altogether futile. The use of red marker over stark, Banksy-esque stencil motifs adds to the narrative of “updating” Bert the Turtle for more “modern” times by attempting to show a “work-in-progress” approach to the images. They remain unfinished and merely sketches of what could be, not what is.

Duck and cover is a metaphor for how our society has confronted mass gun violence. Rather than reform policy, we double down on how we will respond to the incident itself. As we practice intruder drills with our students in schools, we are assuring them that gun violence will continue. The only preemptive measures our policy makers are willing to take are to mandate rehearsals without adequately confronting the source of this violence.

Bert the Turtle, while seemingly a relic of the Cold War, has never been more timely. This project is an act of civic engagement and protest through digital authorship.

Resources

Rizzo, A. (Director), & Mauer, R. J. (Writer). (2009, July 11). Duck and Cover [Video file]. Retrieved February 27, 2018, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IKqXu-5jw60

0 notes