#enrico medioli

Text

#Once Upon a Time in America#Sergio Leone#Harry Grey#Robert De Niro#James Woods#William Forsythe#Leonardo Benvenuti#Piero De Bernardi#Enrico Medioli#Franco Arcalli#Stuart Kaminsky#Ernesto Gastaldi#80s

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Renato Salvatori and Alain Delon in Rocco and His Brothers (Luchino Visconti, 1960)

Cast: Alain Delon, Renato Salvatori, Annie Girardot, Katina Paxinou, Spiros Focás, Claudia Cardinale, Max Cartier, Rocco Vidolazzi, Roger Hanin. Story and screenplay: Luchino Visconti, Suso Cecchi D'Amico, Vasco Pratolini, Pasquale Festa Campanile, Massimo Franciosa, Enrico Medioli, based on a novel by Giovanni Testori. Cinematography: Giuseppe Rotunno. Production design: Mario Garbuglia. Music: Nino Rota.

When Rocco (Alain Delon) cries out, "Sangue! Sangue!" on finding Nadia's (Annie Girardot) blood on his brother Simone's (Renato Salvatori) jacket, I almost expect to hear Puccini on the soundtrack instead of Nino Rota. It's one of those moments that cause Rocco and His Brothers (along with other films by Luchino Visconti) to be called "operatic." It's "realistic" but in a heightened way -- the word for it comes from the realm of opera: verismo. The moment is in the same key as the actual murder of Nadia, along with her earlier rape by Simone, and the numerous highly volatile scenes of the family life of the Parondis. It's what makes Rocco and His Brothers feel in many ways more contemporary than Michelangelo Antonioni's more cerebral L'Avventura, which was released in the same year. Movies have gone further in the direction of Rocco -- think of the films of Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola -- than they have in the direction of Antonioni's oeuvre. I have room in my canon for both the raw, melodramatic, and perhaps somewhat overacted Rocco and the enigmatically artful work of Antonioni, however.

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Conversation Piece (Luchino Visconti, 1974).

#gruppo di famiglia in un interno#luchino visconti#enrico medioli#suso cecchi d'amico#burt lancaster#silvana mangano#pasqualino de santis#ruggero mastroianni#mario garbuglia#carlo gervasi#dario simoni#vera marzot

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Movie #8 of 2022: The Leopard

Tancredi Falconeri: “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.“

#the leopard#italian#luchino visconti#giuseppe tomasi di lampedusa#suso cecchi d'amico#pasquale festa campanile#enrico medioli#massimo franciosa#nino rota#giuseppe rotunno#mario serandrei#drama#history#latin#french#german#35mm#super technirama 70#cinemascope#08#1963

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

You must realize that today in Germany anything can happen, even the improbable, and it's just the beginning, Frederick. Personal morals are dead. We are an elite society where everything is permissible. These are Hitler's words. My dear Frederick, even you should give them some thought.

The Damned (La caduta degli dei - Götterdämmerung), Luchino Visconti (1969)

#Luchino Visconti#Nicola Badalucco#Enrico Medioli#Dirk Bogarde#Ingrid Thulin#Helmut Griem#Helmut Berger#Renaud Verley#Umberto Orsini#Reinhard Kolldehoff#Albrecht Schoenhals#Florinda Bolkan#Nora Ricci#Charlotte Rampling#Pasqualino De Santis#Armando Nannuzzi#Maurice Jarre#Ruggero Mastroianni#1969

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Il Gattopardo – Leopar

Il Gattopardo – Leopar

Şişirme klasiklerden biri daha. Şüphesiz birçok sahnesi olağanüstü, isyancıların askerlerle savaşmaları en inandırıcı sahnelerdi. Kostümler, mekan seçimi, hatta yer yer diyaloglar dahi övülmeye değer. Uzun mu uzun balo sahnesi ise bıktırdı. Bir bütün olarak düşünüldüğünde ise film can sıkıcı bir tarihi anın yansıtılması. Çok başarılar bulanlar var, benim gibi yetersiz…

View On WordPress

#Alain Delon#Brook Fuller#Burt Lancaster#Carlo Valenzano#Claudia Cardinale#Der Leopard#Enrico Medioli#Evelyn Stewart#Film eleştirileri#Giuliano Gemma#Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa#Il Gattopardo 1963#Il Gattopardo – Leopar#Luchino Visconti#Lucilla Morlacchi#Massimo Franciosa#Ottavia Piccolo#Paolo Stoppa#Pasquale Festa Campanile#Pierre Clémenti#Rina Morelli#Romolo Valli#Süleyman Deveci#Suso Cecchi D&039;Amico#Terence Hill

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Leopard (1963). The Prince of Salina, a noble aristocrat of impeccable integrity, tries to preserve his family and class amid the tumultuous social upheavals of 1860's Sicily.

This is an interesting film - it was famously panned upon it’s release, but history has been pretty kind to it. And deservedly so to be honest - there’s a lot to like in it. Sure, it would’ve seemed dated for the time, and way too long even for now, but there are parts of it that are genuinely transcendent, and the visually language tells a rare but compelling story. It’s a solid film, and not deserving of the horrid reception it got in the 60s. 7.5/10.

#the leopard#1963#Oscars 36#Nom: Costume#Luchino Visconti#Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa#Suso Cecchi D'Amico#Pasquale Festa Campanile#Enrico Medioli#Massimo Franciosa#burt lancaster#Claudia Cardinale#Alain Delon#italy#italian#1800s#romance#war#uprising#revolution#7.5/10

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

So saddened to learn that my favourite screenwriter, Enrico Medioli, passed away today. His impressive work includes

Rocco e i suoi fratelli (1960) by Luchino Visconti

La ragazza con la valigia (1961) by Valerio Zurlini

Il gattopardo (1963) by Luchino Visconti

Vaghe stelle dell’Orsa (1965) by Luchino Visconti

Scusi, facciamo l’amore? (1968) by Vittorio Caprioli

La caduta degli dei (1969) by Luchino Visconti

La prima notte di quiete (1972) by Valerio Zurlini

Gruppo di famiglia in un interno (1974) by Luchino Visconti

His wit, his talent, his love for literature and camellias will be sorely missed.

#enrico medioli#italian cinema#rocco e i suoi fratelli#luchino visconti#annie girardot#la ragazza con la valigia#valerio zurlini#alain delon#claudia cardina#vaghe stelle dell'orsa#vittorio caprioli#scusi facciamo l'amore?#la caduta degli dei#ingrid thulin#helmut berger#la prima notte di quiete#gruppo di famiglia in un interno#silvana mangano#jacques perrin#pierre clementi#jean sorel#renato salvatori

256 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Sandra" (aka "Vaghe stelle dell'Orsa..."), the 1965 Italian movie (in an English dub), featuring Claudia Cardinale, Jean Sorel and Michael Craig, directed by Luchino Visconti, written by Suso Cecchi D'Amico, Enrico Medioli and Luchino Visconti, based on the Elektra myth.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

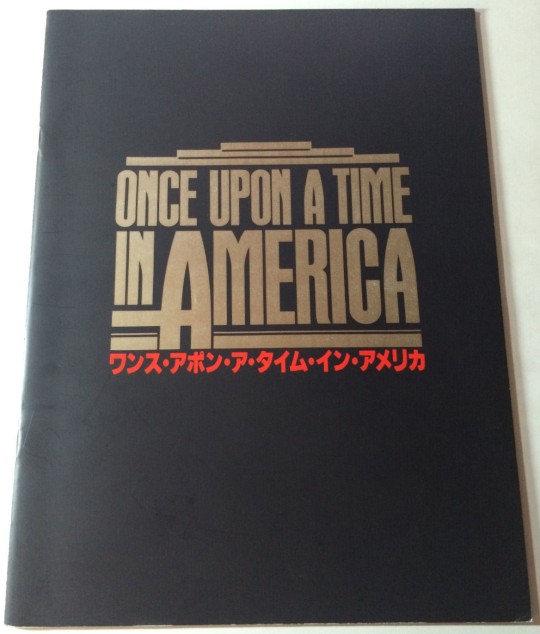

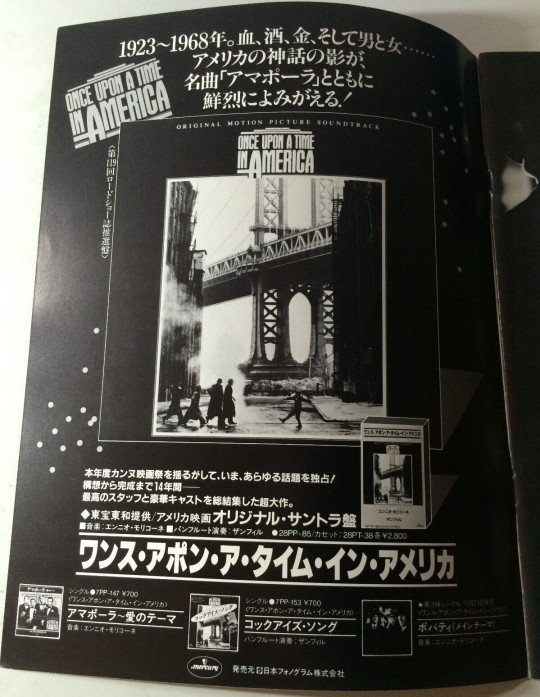

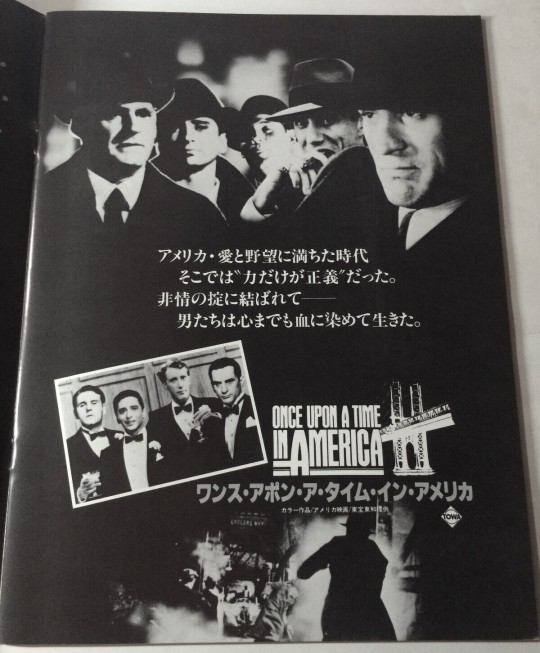

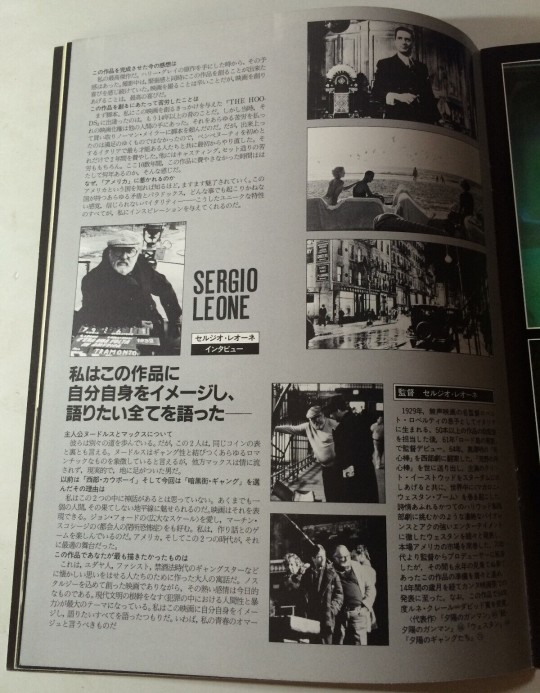

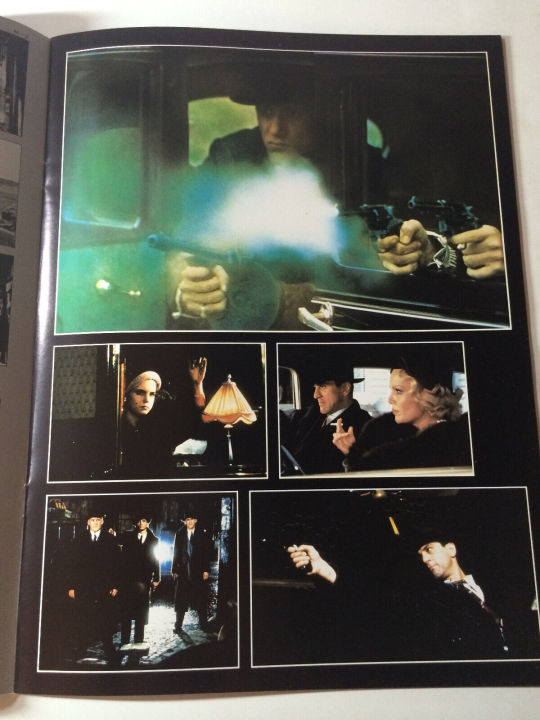

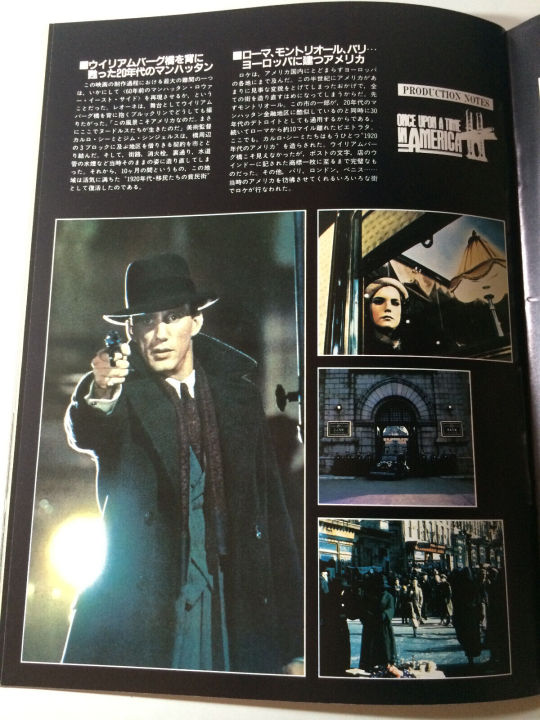

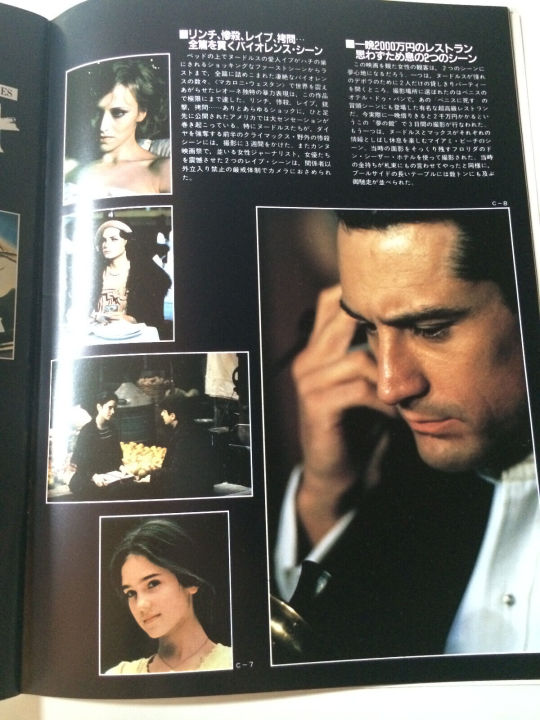

Once Upon a Time in America (1984)

Italian director Sergio Leone made a name for himself worldwide with the Dollars trilogy of Westerns starring Clint Eastwood as the Man with No Name. These movies, along with Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), had more stylized violence than the typical Hollywood Western, and audiences flocked to see what some waved off as pulp novelties. During this period, an idea had been reverberating in Leone’s mind; no longer could he ignore his imagination’s wills. Leone’s success led him to spend ten years working on this passion project, even declining an offer to direct The Godfather (1972). Based on The Hoods by Harry Grey, Once Upon a Time in America is a gangster epic filled with betrayal, crime, graphic violence, and regret. The film alternates between three time periods: the late 1910s/early ‘20s, the final three years of Prohibition from 1930-1933, and 1968. It is Leone’s most ambitious project after a thirteen-year absence from filmmaking, and his last.

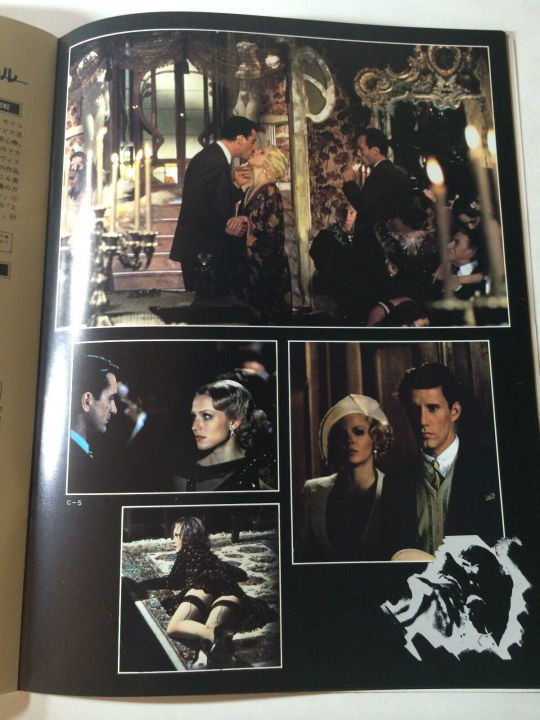

In New York City’s Lower East Side, we follow a handful of young Jewish boys who engage in petty thievery, grow to complete contracts for organized crime, and later make their fortunes bootlegging during Prohibition. The film centers on David “Noodles” Aaronson (Robert De Niro as adult Noodles; Scott Tiler as a child). He is first seen in a Chinese opium den in 1933 after seeing three of his friends’ corpses – burnt beyond recognition – whisked away from a crime scene. A non-diegetic telephone rings during this wordless montage – a blaring, ceaseless ringing serving as an aural pang of guilt. That guilt will be gradually explained as the film progresses. Soon after this opium-induced retreat, Noodles will depart New York City for Buffalo. He will return decades later, his hair and soul fading, after receiving a suspicious invitation. Once Upon a Time in America’s first half concentrates on Noodles’ childhood, alternating with scenes from his 1968 return. The film’s second half intercuts between Prohibition and 1968.

Noodles’ boyhood friends are the protagonist’s de facto family. They include Patrick “Patsy” Goldberg (James Hayden as adult Patsy; Brian Bloom as a child), Philip “Cockeye” Stein (William Forsythe as an adult Cockeye; Adrian Curran as a child), Dominic (Noah Moazezi), and Maximillian “Max” Bercovicz (an excellent and up-and-coming James Woods as adult Max; Rusty Jacobs as a child). Fat Moe (Larry Rapp as an adult Moe; Mike Monetti as a child) is not part of the gang, but is nevertheless a friend who knows their secrets. The film also features Noodles’ young love interest, Deborah (Elizabeth McGovern as adult Deborah; a debuting Jennifer Connelly as a child) and friend/underage prostitute Peggy (Amy Ryder as adult Peggy; Julie Cohen as a child). Also appearing in the film are Joe Pesci (whose unclear role in the film is heavily downplayed in the European cut), Burt Young, Tuesday Weld, Treat Williams, and Danny Aiello. Louise Fletcher's cameo appears only in the most recent restoration.

Before continuing with this review, I want to note that there are multiple versions of Once Upon a Time in America available to viewers. Leone’s film debuted at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival with a runtime of 229 minutes (the “European cut”). For the American general release one week later, the film’s distributor (the Ladd Company, via Warner Bros.) cut the film to 139 minutes without Leone’s permission or input. The American theatrical cut – which was released on VHS in the 1980s and ‘90s and sometimes appears on television – rearranges scenes to play in a strictly chronological structure and removes essential plot details, essentially butchering Leone’s directorial intent. A 2014 Blu-ray release of Once Upon a Time in America includes additional footage bringing the runtime to 250 minutes, but the additional footage – due to the degradation of the original negative – appears worse for wear. This review is based on the European cut, which is the recommended print for all those seeing this film for the first time.

With a screenplay by Leone, Leonardo Benvenuti, Piero De Bernardi, Enrico Medioli, Franco Arcalli, and Franco Ferrini, Once Upon a Time in America is told through the lens of an unreliable narrator in Noodles. How one views the film changes radically depending on which period should be considered the “present”. If the viewer interprets Once Upon a Time in America as using the 1968 scenes as its anchor, the film is an old man’s reverie – where a lifetime of guilt is revisited and ghosts are confronted. In this interpretation, are Noodles’ memories of his childhood and young adulthood sanitized to spare him further pain? How does he square with all the pain he has been responsible for? Or perhaps one might view Once Upon a Time in America using 1933, as Noodles retreats to the opium den, as the anchor. Here, the 1968 scenes become an opium dream or a nightmare, a painful future that may have been. If indeed this is an opium-induced dream (which would make the 1968 scenes nothing but a hallucination), does that make the childhood scenes even less genuine than in the former interpretation? That Leone and his writers never force the viewer down either avenue speaks to its thoughtful screenplay.

No matter how one reads this film, it requires complete attention. Characters age over fifty years, friendships are formed and destroyed, and innocence is forever lost. Whether it is viewed as an old man occupied by his violent past or a young gangster attempting to smoke away his pain, Once Upon a Time is awash in regret. As much as viewers might sympathize with Noodles, Leone’s film portrays Noodles’ violence as the result of terrible choices influenced by his friends. Granted, there is one occasion where he kills in self-defense. But even that killing is laced with rage and revenge. Faced with the choice between his friends and the money involved with their operations and being with Deborah, Noodles will attempt to have both. Deborah’s disapproval of the gang’s behavior – her opposition becomes more tacit as she ages – assures that Noodles retain some semblance of a conscience as Max’s arrogance permeates through all their friends. Neither fully committing to the appeals from Deborah or his friends, Noodles will lose both.

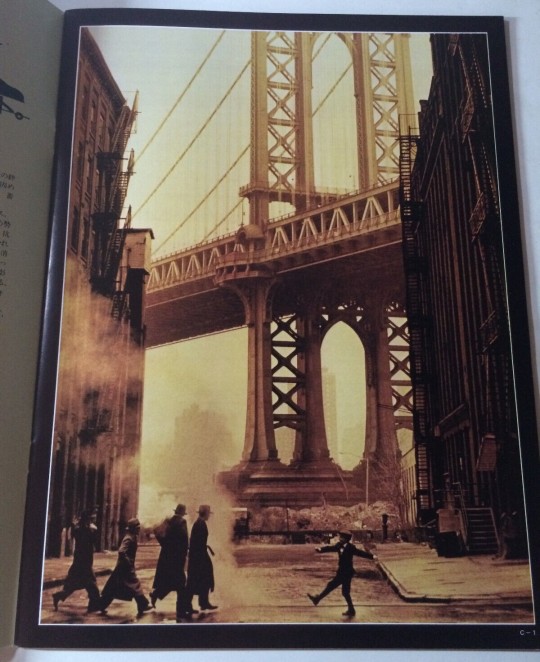

In the film, smoke or steam is usually present just before or during moments tinged of bittersweet memory. Whether emanating as puffs from an opium pipe, the steam billowing from New York City’s manholes on a frigid day, or discharges from a passenger train, it is a demarcation of an event that will irrevocably affect Noodles’ life. Potentially, due to the film’s openness to interpretation, smoke or steam may also herald moments where Noodles’ memories are most suspect – through conscious reframing of his story or opium-influenced phantasms. Either way, certain narrative threads are left incomplete, raising questions over whether those dangling characters and subplots were Leone’s original intention. Perhaps Leone here is acknowledging the voids in human memory – people and things half-forgotten. Unlike its genre counterparts, Once Upon a Time in America leaves little space for comic relief. Any levity in the film is snuffed out almost immediately due to monstrous lust, performative masculinity, or Noodles’ weariness. The elderly Noodles is stone-faced, wrapped into a world frozen in time the moment he boarded that train to Buffalo. His pain is omnipresent in Once Upon a Time in America. Even in the earliest scenes of his childhood, the years of rumination can be felt in the film’s deliberate pace. Robert De Niro and Scott Tiler, respectively, embody the older Noodles’ sorrow and the younger Noodles’ conflicted feelings.

Like American Western films, the gangster genre is rife with mythologizing and, at times, a glorification of their protagonists’ violent lives. Where Westerns over the last half-century have deconstructed their role in the American mythos, the gangster film – probably because gangster films were never as ubiquitous as Westerns at their respective pinnacles of popularity – has not done so nearly as much introspection. Before Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990) and especially The Irishman (2019), Once Upon a Time in America stood mostly alone among gangster films as a rueful examination of its protagonist’s violent lifestyle. The film consistently undermines its characters’ celebrations and successes with the consequences of their prior actions. Those consequences weigh on Noodles still.

But Leone is not entirely successful in this regard. Once Upon a Time in America has two overlong rape scenes – both of which turned my stomach the longer they went on – following a fruitful robbery (this one follows an unsettling submissive fantasy by its victim) and a glamorous date, respectively. The two rapes are committed by Noodles; both scenes serve to highlight his descent into depravity rather than express a minimal concern for the victim. Once Upon a Time in America, already uninterested in developing its female characters beyond sex objects, frames Noodles as a husk of a man because of the murders and robberies he has committed, not his treatment of women. Just because the film has adopted Noodles’ viewpoint – in his childhood and young adulthood, he cannot differentiate between objectification and love – does not mean Leone and his screenwriters can wave away his misogyny as secondary to his violent tendencies. His misogyny and criminality are distinguishable, but both were learned from the same people and environment. This dynamic persists even from the first moment that Jennifer Connelly appears as the young Deborah. There, Deborah sexually teases the young Noodles in a way that neither reflects her personality as a child or as an adult. Is that the result of the opium clouding Noodles’ memory or is it Noodles’ obsession with Deborah?

Once Upon a Time in America is beautifully shot by Tonino Delli Colli (1966’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, 1997’s Life Is Beautiful) and edited by Nino Baragli (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Once Upon a Time in the West). Like a photograph that has faded somewhat but still captures the likeness and character of its subjects, the brown environments and warmly-lit interiors capture the spirit of these neighborhoods of New York City’s Lowest East Side. Life is hardscrabble here, with those born into the prevalent poverty rarely escaping from it. Their Jewishness, verbally and visually, is strangely downplayed by Leone. The film’s long takes – several last over thirty seconds – without any cuts from Baragli allow the viewer to reflect on its changing characters, internalizing the film’s scope and depth of Noodles’ introspection. For the 1968 scenes, the browns are mostly replaced by overcast grays in exterior and interiors. The colors, no longer as warm or as diverse, help the film navigate its temporal and tonal transitions.

youtube

Ennio Morricone’s powerful score does even more to strengthen the film’s emotional power. The recently-passed composer, best known for his work on Leone’s Dollars trilogy, was a classically-raised/taught, jazz-loving experimenter whose sound could be bold and brash. Upending expectations for what the Western could sound like with anachronistic electronic elements and guitar, Morricone suspends any anachronisms for his Once Upon a Time in America score. The viewer will hear an odd pan flute (not Morricone’s decision) and diegetic/non-diegetic jazz music, but the defining aspect of the score is its romantic minimalism. One does not associate minimalism with grand emotions, but the score’s romantic minimalism – encapsulated by “Deborah’s Theme” – does not preclude the pathos it evokes. The rests in the lushly-orchestrated “Deborah’s Theme” (according to Morricone himself, despite the cue’s name, it can also be interpreted as the film’s main theme) reflect Noodles’ silent longing and remorse. Even at mezzo piano with no dialogue or sound effects present, Morricone’s cues pierce the soul. As longtime collaborators, Leone respected Morricone’s talents, allowing his friend and colleague’s music to be the star for long stretches. Leone allows Morricone to envelop the viewer in its textural splendor. The orchestral renditions of “Amapola” and The Beatles’ “Yesterday” are effective in placement and arrangement. Whether it is his theme for childhood and poverty, for the film at large, or for Deborah, Morricone’s score to Once Upon a Time in America is an essential part of his film scoring career – a career that spans so many titles, that most of it has not been heard outside of his native Italy.

Before and when making this film, Leone intended to direct two films running around 180 minutes each. Convinced by his producers to whittle Once Upon a Time in America to the 269-minute version that should be sought for a first viewing, Leone was horrified to hear that the Ladd Company – frightened by the runtime and (justifiably) the rape scenes – decided to eviscerate his film. When word eventually (and inevitably) reached Leone’s North American fans that they would not be receiving a version of Once Upon a Time in America that respected Leone’s authorial voice, the film bombed at the box office and was savaged by most anyone who saw it. To some critics including the Chicago Tribune’s Gene Siskel, Once Upon a Time in America’s American theatrical version was the worst film of 1984; in an about face for those same critics, the European cut was the best film of 1984. Eighteen minutes of footage for Once Upon a Time in America have still not seen the light of day due to continuing legal entanglements surrounding them. Leone’s ardent admirers remain hopeful for their eventual inclusion on a future print.

As he challenged the tropes of American Westerns, so too did Leone subvert what might be expected from a gangster film. Or, perhaps with a cynical grin, Leone is challenging the essence and veracity of cinematic narrative. Once Upon a Time in America is an underappreciated, imperfect movie whose reputation continues to grow the further removed it is from its botched release. America’s traditions of tall tales and melting pot storytelling make villains and bystanders of the unsavory characters contained within. Haunted by a past that cannot be changed, Noodles attempts to reclaim his life’s story from those who have written it. As the viewer, we project our anxieties and insecurities onto images spliced to make narrative sense. Authorship disputes and the struggle between legend and fact permeate cinema. Seldom do they converge as movingly as they do here.

My rating: 9.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#Once Upon a Time in America#Sergio Leone#Robert De Niro#James Woods#Elizabeth McGovern#Joe Pesci#Burt Young#Tuesday Weld#Danny Aiello#James Hayden#William Forsythe#Larry Rapp#Ennio Morricone#Tonino Delli Colli#Nino Baragli#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Once Upon a Time in America#Sergio Leone#Robert De Niro#James Woods#Elizabeth McGovern#Jennifer Connelly#Treat Williams#William Forsythe#Scott Tiler#Rusty Jacobs#Brian Bloom#Adrian Curran#Harry Grey#Leonardo Benvenuti#Piero De Bernardi#Enrico Medioli#Franco Arcalli#Franco Ferrini#Stuart Kaminsky#Ernesto Gastaldi#80s

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

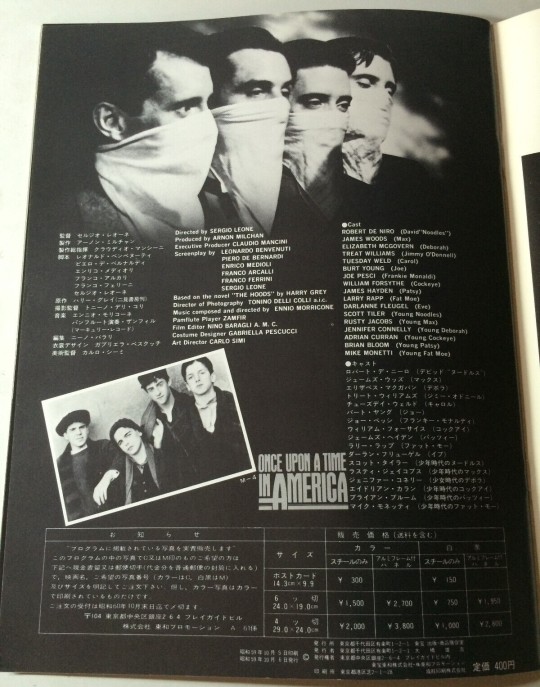

Once Upon a Time in America (Sergio Leone, 1984)

Cast: Robert De Niro, James Woods, Elizabeth McGovern, Treat Williams, Tuesday Weld, Burt Young, Joe Pesci, Danny Aiello, William Forsythe, James Hayden, Darlanne Fluegel, Larry Rapp, Jennifer Connelly, Scott Tiler, Rusty Jacobs, Brian Bloom, Adrian Curran, Mike Monetti, Noah Moazezi, James Russo. Screenplay: Leonardo Benvenuti, Piero De Bernardi, Enrico Medioli, Franco Arcalli, Franco Ferrini, Sergio Leone, Stuart Kaminsky, based on a novel by Harry Grey. Cinematography: Tonino Delli Colli. Production design: Giovanni Natalucci. Film editing: Nino Baragli. Music: Ennio Morricone.

Sergio Leone's romantic epic Once Upon a Time in America is some kind of great film, but I'm not sure what. It's about gangsters, to be sure, but is it really a gangster movie, in the lineage that stretches from the Warner Bros. gangster movies to the familiar parts of the oeuvre of Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese? It seems to me to more of a character study, a kind of Bildungsroman about the moral education of David "Noodles" Aaronson (Robert De Niro), whose internal life seems to me very different from that of the paradigmatic troubled gangster, Michael Corleone. That the whole story of OUATIA may in fact be Noodles's opium dream, as the concluding shot seems to suggest, gives a quality of fantasy to the film, as even its fairytale title underscores. I have to admit that at first I wasn't happy about giving up four hours of my movie-watching time to Leone's film, which still lingers in a kind of sad obscurity in the minds of the general public, especially since it was mistreated, panned, and tanked on its original release, when it was cut by 90 minutes. It was only the efforts of a few critics and cinéastes that promoted its rehabilitation, and its showing two years ago on TCM was a "premiere" for that network after 35 years. There are some self-indulgent moments to the movie, too -- scenes that move more slowly than they might, setups that don't quite deliver on their potential. It's very much a "foreign film" in narrative technique, more redolent of Antonioni than of Coppola. What American director of the 1980s would have come up with such an enigmatic ending as the garbage truck and the flashback to the opium den? (The American cut by the Ladd Company ended with an off-screen gunshot suggesting that Max/Bailey had killed himself.) But even its flaws have a hint of greatness about them.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gruppo di famiglia in un interno (Luchino Visconti, 1974).

#gruppo di famiglia in un interno#gruppo di famiglia in un interno (1974)#luchino visconti#conversation piece (1974)#conversation piece#enrico medioli#suso cecchi d'amico#burt lancaster#silvana mangano#pasqualino de santis#ruggero mastroianni#mario garbuglia#carlo gervasi#dario simoni#vera marzot

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Les Damnés" mis en scène par Ivo van Hove - d'après un scénario de Luchino Visconti, Nicola Badalucco et Enrico Medioli - avec Didier Sandre, Denis Podalydès, Guillaume Gallienne, Christophe Montenez, Loïc Corbery et Adeline d'Hermy à la Comédie-Française, mai 2019.

#spectacles#VanHove#Visconti#Badalucco#Medioli#Sandre#Podalydes#Gallienne#Montenez#Corbery#DHermy#ComedieFrançaise

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les aciéries Krupp embrasent la Comédie Française

Les masques tombent, les trahisons et les morts éclaboussent. Adaptation saignante des Damnés de Visconti.

Juste le scénario du film, rien d’autre. C’est comme ça que le metteur en scène belge Ivo Van Hove a gardé les mains libres pour monter Les Damnés. Et sa mise en scène est fluide, spectaculaire (par l’utilisation de la vidéo) et au plus proche des comédiens. On en ressort KO.

Pacte avec le diable

L’histoire écrite par Visconti est une escalade théâtrale sans pitié, shakespearienne, où le destin d’une des plus grandes familles industrielle allemande croise l’irrésistible ascension du nazisme. Au sein du clan, les sympathisants nazi sont très minoritaires, mais ils vont faire tomber les sceptiques, les uns après les autres, les trahissant, les poussant à la fuite, les piégeant, les assassinant. Jusqu’aux plus jeunes, ils pactisent avec le diable, se croyant plus malins. Pour marquer l’horreur de ces disparitions, une caméra les montre dans leur cercueil où ils agonisent jusqu’à leur dernier souffle. Glaçant.

Plancher couleur feu

Les héritiers, frère, soeur, fils, cousin, s’affrontent, sur fond de réarmement militaire clandestin (nous sommes en 1933), chacun jouant la prudence et la duplicité, jusqu’à être acculé. Le Reichstag vient d’être incendié, les livres "anti-allemands" brûlés. Maintenant, soit vous être pour le régime en place, soit vous être contre. Le plancher, couleur feu, embrase la salle Richelieu jusqu’au plafond.

Conception extrême de l’amour maternel

Pièce centrale dans ce puzzle politico-industriel, Sophie von Essenbeck (belle Elsa Lepoivre). Avec son amant, l’odieux Bruckman (Guillaume Gallienne méconnaissable), elle fait entrer le loup nazi dans la bergerie, croyant tirer les ficelles, tout comme le veule baron Konstantin (Denis Podalydès, surprenant en SA décadent). Elle affronte son propre fils (Christophe Montenez, dans le rôle tenu par Helmut Berger dans le film), qui a une conception très extrême de l’amour maternel. Jusqu’au retournement final, avec goudron et plumes.

Aucune fausse note dans cette descente aux enfers, les longueurs sont gommées par quelques électrochocs sonores ou lumieux bien sentis. Vous aussi, vous serez fasciné par l’horreur.

LES DAMNÉS, à la Comédie Française, salle Richelieu

jusqu’au 10 décembre 2017

De Nicola Badalucco, Enrico Medioli & Luchino Visconti

Mise en scène Ivo van Hove

Avec

Basil Alaïmalaïs, Sébastien Baulain, Sylvia Bergé, Loïc Corbery, Jennifer Decker, Adeline d’Hermy, Guillaume Gallienne, Thomas Gendronneau, Eric Génovèse, Ghislain Grellier, Clément Hervieu-Léger, Elsa Lepoivre, Oscar Lesage, Christophe Montenez, Alexandre Pavloff, Denis Podalydès, Didier Sandre, Stephen Tordo, Tom Wozniczka

Attention : certaines scènes sont susceptibles de heurter la sensibilité des plus jeunes.

Molière 2017 : Meilleur spectacle de Théâtre public / Meilleure Création visuelle / Meilleure Comédienne dans un spectacle de Théâtre public : Elsa Lepoivre

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Damned (dir. Luchino Visconti)

-Jere Pilapil- I can’t help but look at this one as “Succession on steroids” (or Nazi Super Soldier Serum for you Marvel heads). LIke how Succession is about the political maneuvering and infighting of a family in charge of a media empire, The Damned is Luchino Visconti’s film about a family infighting for control over a steelworks company. When The Criterion Collection added the movie, I was that anime butterfly meme asking “Is this Succession but more fucked?” And I can now tell you that yes, yes it is.

The added twist is that the movie takes place over the course of the rise of Nazis in Germany, with the Reichstag fire occurring off screen in the first scene. There’s a bit of extra urgency as the war effort makes steel more valuable, and there’s a lot of extra viciousness in the central family, whose members have varying opinions of and loyalties to Hitler. We get depictions of the characters being able to tell which way the political wind blows, using Hitlers whims to their advantage as control of the company passes around through murder and blackmail.

I’m not sure what was in the water in Italy in 1969; I just watched Fellini Satyricon, which came out the same year and was also a brutal critique of culture, capitalism and exploitation (if more cartoonish and based in Greek myth). Visconti is similarly interested in exploring a kind of depravity created by greed. Some family members are, let’s say, up to some evil shit because their privilege lets them get away with it. But somehow this, Fellini Satyricon and Salo are coincidentally three in a row that are Italian movies where you’re not asked to identify with a central character but just watch a bunch of characters do a bunch of awful shit and feel bad about it because it’s a microcosm of society then and echoes into today.

The characters are paper-thin, defined mostly by their hunger for power and willingness to do anything for it. However, they are well-acted, and the production design is incredible. It’s frankly, tough to watch this one in some ways, but it’s also a fascinating film. Visconti and co-screenwriters Nicola Badalucco and Enrico Medioli take wild swings with their twists and turns. The movie needs them, since it’s barely about the psychology of the characters but rather “what’s the next Bad Thing?” And I definitely vibe with that, as long as the Bad Thing keeps me on my toes. PS I don’t know why the Criterion blu-ray doesn’t have subtitles! Drives me nuts that normally they’re great with that shit, but this time - a movie spoken mostly in English with German accents and often whispers - didn’t offer that. Bad Criterion! Be better! 9/10

0 notes