#especially after they settled in beleriand and even more so after maedhros was rescued from thangorodrim

Text

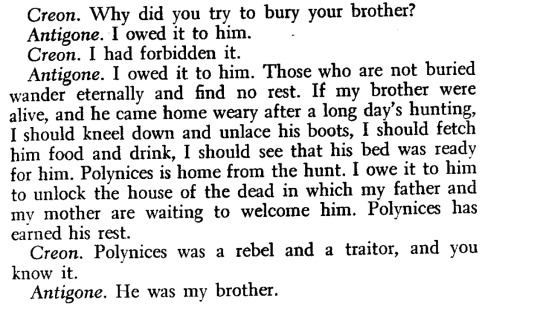

"He was my brother"

This is probably my favourite part from "Antigone" by Jean Anouilh and it makes me think of Maglor and Maedhros. The familial love, the devotion, the loyalty....it makes me emotional.

#maglor loved his big brother so much that he followed him to the very end even when he did not agree with him.#i can definitely see him going against any rules if it meant giving maehdros a proper burial#if there was a body to bury of course#maedhros might have been a rebel and a kinslayer but he was maglor's brother first and foremost#i think maglor would absolutely be the one to welcome his brother home after a long day's hunting#and “kneel down to unlace his boots” and “fetch him food and drink” and “see that his bed was ready for him”#especially after they settled in beleriand and even more so after maedhros was rescued from thangorodrim#maglor would make sure to take care of his brother as much as possible and make his life easier and take some of his burdens upon himself#anyway#my posts#antigone#maedhros#maglor#maedhros and maglor#sons of feanor#feanorians#silmarillion#brothers

111 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I’m a relatively new follower and I just started going through your posts. I just wanted to say that I love your takes on Tolkien’s work. They sum everything up really nicely and you seem to really try to take both sides into consideration. I love the academic but down to earth feel of your writing, and I always learn something new whenever I read! I don’t know if you’re accepting requests, but I saw your amazing “Feanorian Counternarratives,” and I was wondering if you have any ideas about Caranthir? If you are not accepting requests, are too busy with your polls, or simply don’t feel like answering, I completely understand. I just wanted you to know that I really like your work! Have a nice day ❤️ - @arinele

Oh my goodness, thank you so much! That’s very kind! 💕 I’ve loved seeing your tags!

I do have some thoughts on Caranthir, though, fair warning, they’re not especially complimentary. They’re pretty headcanon-heavy, since we only get tidbits on him.

Character Thoughts - Caranthir

From what we see of Caranthir, the thing that stands out to me most is his disdainful behaviour towards anyone who isn’t (entirely) Noldor. It comes out in practically every instance we see of him in The Silmarillion. I wouldn’t guess that this is unique to Caranthir among the Fëanoreans (we get similar cultural chauvinism from Fëanor in his “in huts on the beaches you would be dwelling still” line to Olwë, and all the sons of Fëanor are described as “haughty and fell”), but he seems to have a more than usual lack of tact about it; he’s described as “the harshest and most quick to anger” among the sons of Fëanor

First there’s his words to Angrod (“Let not the sons of Finarfin run hither and thither with their tales to this Dark Elf in his caves!…let them not so swiftly forget that their father is a lord of the Noldor, though their mother be of other kin”….wow, on top of everything else, way to remind them that you murdered their mother’s people). It’s telling that this is in no way a small incident - it’s the moment that prompts Maedhros moving the Fëanoreans to East Beleriand, and the memory and resentment of it is what prompts Angrod to spill the beans to Thingol about the Kinslaying. Caranthir can do a lot of damage with a few words!

His lack of tact towards the dwarves doesn’t have similar impact - because of pragmatism on both sides and also, I expect, because, though the dwarves are proud, they aren’t especially vain, and being insulted for their looks bothers them a lot less than many other things would.

His interactions with Haleth and the Haladin are interesting. At first his people “pay little heed to them,” which is a marked contrast not only to Finrod’s instant befriending of the Edain, but to Fingolfin’s rapid endeavours to build relations and an alliance. After he rescues the Haladin from the Orcs he “sees, over late, what valour there was in the Edain”, and invites them to live further north in his land. The Haladin are currently in the southern woods of Thargelion. Now, this can be taken either of two ways. Option one, he’s inviting them to live closer to the main settlement of his people, near Lake Helevorn, for more effective mutual defence. Option two, he’s inviting them to live closer to the front lines because he’s seen that they’re good warriors and he wants them between Angband and the bulk of his people. I tend to lean towards the latter; Haleth’s choices certainly indicate she mistrusts him.

And if we do go with the latter, it creates some very interesting headcanons for me in the latter part of the story, where we see less of Caranthir individually. If Caranthir is (“over late”) seeing the military value of the Edain and trying to recruit them, and he failed, then he could be expected to particularly resent that the Haladin end up settling next to Thingol (who doesn’t even like them!) and agreeing to protect his borders, and resent Finrod for negotiating it. This would give him a reason to largely have fellow-feeling with Celegorm and Curufin after the events of Leithian, and accept whatever account they gave of their dealings with Nargothrond and Doriath and their grievances.

Even more, this also adds extra, painful irony to the Nirnaeth, when Caranthir again attempts to make an alliance with Men and it goes terribly wrong. It does stand out that the men who ally with Caranthir turn traitor while those who ally with Maedhros stay loyal - Caranthir has a record of alienating people whether he’s trying to or not, he lacks tact, and it’s not hard to see him saying some things that suggest that the Easterlings are being recruited as cannon fodder. It is, at any rate, my headcanon that Caranthir’s personality has a not-inconsiderable role in why it is the Easterlings aligned with him who change sides. And I like the way it bookends the first real appearance of Caranthir as an individual character, when his words throw a rock into both intra-Noldor and Noldor-Sindar relations.

The combination of bitterness in general around Uldor’s betrayal, bitterness about Doriath due to the aforementioned, and combined bitterness about Doriathrin non-participation in the Nirnaeth, all in addition to the matter of the Silmaril, would give him plenty of reason to be favourable towards the Second Kinslaying.

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

elves of arda ✹ gondolindrim ✹ headcanon disclaimer ✹ @gondolinweek

Rōka was one of the first elves, among those who woke upon the shores of Cuiviénen. He was counted among the Tatyar, though he pledged loyalty to no leader, trusting rather in his own wisdom. Before the Great Hunter appeared and took many of the Quendi to the West, Rōka and his dear friend Anmír created a fëa-bond together, the first to do so without a simultaneous union of their hröar. Rōka was a resourceful nér, searching with Anmír for ore and jewels, and was one of the first elves to develop rudimentary smithing techniques. Rōka made more practical tools, while Anmír, who lengthened hir name to Anmíridil, was renowned for hir jewelry.

When the Three Kings returned out of the West and the First Sundering of the Elves began, Rōka was loath to leave the starlit lands even for the promise of a greater light. Anmíridil, however, was enchanted by Finwë’s tales of great jewels and greater brilliance, and was eager to be gone. The pair could come to no agreement, and it was with sorrow that they bid one another farewell as Anmíridil set out upon the Great Journey and Rōka turned east with Morwë.

Anmíridil made it to Aman with the rest of the Noldor and found hir dreams fulfilled in Valinórë’s majesty. Ze became a masterful jewelsmith, named only after Fëanáro in the accounts of the Noldor. Meanwhile, Rōka worked diligently to improve the smithcraft of his people the Hwenti, and for centuries each found fulfillment in their craft.

The creatures of the Shadow were a constant threat in Middle-earth, and as the years after the War for the Sake of the Elves passed without any hint of further threat from the Valar, their boldness only grew. Hwenti settlements were raided by beasts and fearsome orcs, and in one such attack Rōka was taken captive and dragged into the depths of Angamando, where he was put to work in the mines.

Rōka endured cruel treatment and harsh conditions, but with each strike of his mighty hammer he only grew stronger. When forty years had passed beneath the mountains, Rōka rallied his fellow thralls and rebelled against their captors. Their revolt was vicious, and Rōka himself faced down a Balrog’s fire and very nearly defeated it—but in the end many elves were killed and the rest subdued when Lieutenant Mairon descended to punish the rebels.

For his fury, Rōka earned the name Rôg, “demon,” at first given in petty scorn by the true demons but then adopted by Rôg himself and his compatriots in defiance against the might of the Balrogs. It was amid this trouble that Rôg reencountered Tórin the brother of Daurin, another Tatya from Cuiviénen who had been seized by the Shadow whilst on the Great Journey, and the two began to scheme for another revolt sometime in the future.

When the Noldor returned to Middle-earth and assailed the gates of Angband, many thralls were stirred to hope—but soon the Exiles were beaten back, one king slain and another taken captive, and that hope was lost. Yet not to Rôg and Tórin, for they were determined to use this unrest to their advantage. The right moment came when Findekáno Ñolofinwion rescued Nelyafinwë Maitimo from the cliffs of Thangorodrim, a feat so impossibly daring that the thralls of Angband rose up once more in rebellion.

Much blood was shed in the depths of Angband, but this time some captives managed to escape. Rôg led a band of twenty-three escapees out into the light of the newborn Sun, Tórin at his side. He led them first to Doriath seeking refuge, but Elu Thingol, fearing their minds had been turned, refused them entry to his realm. Next Rôg turned north to the land of Mithrim, where Ñolofinwë agreed to shelter them. It was there that he met Maitimo, the instigator of his freedom, and helped him craft the new name Maedhros.

In Mithrim, Tórin faced dreadful news when he inquired after his brother, for Daurin had been part of the vanguard of Fëanáro and was slain by Balrogs in the Dagor-nuin-Giliath. For Rôg there was a happier reunion: Anmíridil had returned to Middle-earth with the Host of Ñolofinwë, and the pair rejoiced to be together once more, setting aside their differences for the sake of their ancient friendship.

As the Noldor settled in Beleriand, Rôg became known as a lord of the ex-thralls, especially those who had never been to Valinor. He and Maedhros quarrelled over the best way to defy Morgoth, Maedhros taking his folk north to the Hill of Himring to face their foe directly while Rôg thought it wiser to bide their time in safer lands, gathering the strength to strike at the precisely correct moment. Thus he led his followers to Nevrast, far from the sight of Angband, and was keenly interested when he heard of Prince Turukáno’s plans to build a hidden city where his people could safely prepare for such a battle.

Turukáno offered a lordship to Rôg, seeking his aid in constructing Ondolindë, and Rôg accepted on the condition that the former thralls among his people would be protected. His folk were among the first to relocate to the valley of Tumladen. Upon their departure, Rôg asked Anmíridil, now known as Enerdhil, to accompany him to Ondolindë; Enerdhil agreed, and at long last they reinstated their partner bond.

In Ondolindë, Rôg became the Lord of the House of the Hammer of Wrath. His folk were primarily miners and smiths, attracting the greatest craftsmen of the Gondolindrim as well as the ex-thralls that had been his original followers. The folk of the Hammer of Wrath were ever vigilant and did not let their skills in battle fade; thus, though they were amid the frontlines of the force Turukáno brought to the Fifth Battle, few of them perished in that dreadful conflict, for they more than any other folk of Gondolin hated Morgoth and awaited the right moment to bring about his defeat.

Many of the less fierce folk of this House, intimidated by the wrath of their peers, would shift allegiances to the House of the Mole when the King’s nephew Maeglin established another House of smiths and miners. Enerdhil remained at hir partner’s side, but ze was sympathetic to this group and did hir best to make them welcome in hir forges. Ze created many magnificent works in Ondolindë, including the restoration of the Elessar into a betrothal necklace for Princess Idril after the jewel was recovered from the body of High King Fingon.

Rôg hoped that the Union of Maedhros would prove to be the moment he had awaited to strike against Morgoth, and urged King Turukáno to support his brother’s armies in the Fifth Battle. Alas, Maedhros betrayed his trust once more, and the Gondolindrim were beaten back, leaving Rôg more bitter and angry than ever.

When Morgoth’s forces assailed Ondolindë and the city’s fall began, the folk of the Hammer of Wrath met the Enemy head-on. They and the House of the Tree fought fiercely against the orcs, slaying great numbers of them, but then dragons and Balrogs pushed them back. In this moment, Rôg rallied his folk again, sparks flying from his eyes in the fury of his rage, and charged forth again. He was the first to prove that Balrogs could be killed, and he and his folk bought precious time for their allies to gather themselves. Gothmog, Lord of Balrogs, cut off any path of retreat, but when Rôg realized he and his House were doomed he only redoubled his assault. The House of the Hammer of Wrath was utterly destroyed that day, from Rôg and Tórin to the lesser smiths whose names have been forgotten, but it is sung that each that died took the lives of seven foes to pay for their own.

Alone of hir partner’s House, Enerdhil survived the Fall, carrying the memory of hir people into the Second Age, where ze settled in the city of Ost-in-Edhil and joined the Gwaith-i-Mírdain. Ze was slain in the Sack of Eregion, and only then was ze reunited with Rôg once more in the Halls of Mandos. In time they would both be reborn in Aman, joining Tórin and his brother Daurin and the other great folk of the Hammer of Wrath, honored among all elves for their honorable sacrifice in the Fall of Gondolin.

#gondolinweek2021#gondolinweek#tolkienedit#oneringnet#silmarillion#tfog#the fall of gondolin#house of the hammer of wrath#rog#enerdhil#torin#daurin torin#trans tolkien#my edit#my writing#edit writing#headcanons#tefain nin#elves of arda#gondolindrim#long post#i was planning on doing galdor today too but i didn't have the spoons to write another caption rip#i'll do him on day 8 instead since i don't have anything else planned for then

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Doriathrin Isolationism

I’ve seen a fair number of takes in the Silm fandom on the topic of either “the Noldor are horrible imperialists” or “the Sindar are horrible isolationists”, so I thought it would be interesting to take a closer look at Doriathrin policy.

Firstly, how isolationist are they, following the creation of the Girdle of Melian? They still have close relations with the Laiquendi of Ossiriand, and some of them come to Doriath. They still have close relations with Círdan and are in communication with him. They’re fairly close with the children of Finarfin: Galadriel lives in Doriath, the others visit, Finrod is close enough with Thingol to act as an intermediary between him and the Haladin, and Thingol is the one who tells Finrod of the location for Nargothrond. The dwarves continue travelling to Doriath, and trading, and living there for long periods to do commissioned craft-work, through long periods of the First Age, even after the Nirnaeth - the Nauglamír Incident could never have happened if not for that. All these people can pass freely into Doriath. So we’re not talking about Doriath cutting itself off from the rest of the world, not by any means. We’re talking specifically about its relations with three groups: 1) the Fingolfinian and Fëanorian Noldor; 2) the Edain; and 3) the Northern Sindar.

Every time I try to write this post it gets really long, so here I’m going to focus on Doriath’s relationship with the first and third groups, other Elves, and leave the Edain for a separate post.

Doriath and the Northern Sindar

Thingol’s attitude towards this group is the least excusable, and something I wasn’t aware of until I got my hands on a copy of The Peoples of Middle-earth (HoME Vol. 12):

[Thingol] had small love for the Northern Sindar who had in regions near to Angband come under the dominion of Morgoth, and were accused of sometimes entering his service and providing him with spies. The Sindarin used by the Sons of Fëanor also was of the Northern dialect; and they were hated in Doriath.

Now, to be clear, Thingol is wrong about the Northern Sindar being shifty. They’re the ones more commonly described in The Silmarillion as the grey-elves of Hithlum. They make up a substantial portion of the people of Gondolin. They include Annael and his people, who raise Tuor. (Presumably others live in, or moved to, East Beleriand along with the Fëanorians, as the Fëanorians speak their tongue.)

Here is what I think probably happened. We have statements in The Silmarillion that Morgoth captured elves when he could, and that:

“The Noldor feared most the treachery of those of their own kin, who had been thralls in Angband; for Morgoth used some of these for his evil purposes, and feigning to give them liberty sent them abroad, but their wills were chained to his, and they strayed only to com back to him again; therefore if any of his captives escaped in truth, and returned to their own people, they had little welcome, and wandered alone outlawed and desperate”.

If Morgoth also captured some of the Northern Sindar - who, living closer to Angband, would be more at risk of this than Doriathrim, Falathrim, or Laiquendi - there could, as with later Noldor prisoners, have been some who were under his control and attacked and betrayed other elves. The Doriathrin Sindar, living further from Angband, might have been unaware of their capture, conflated this with deliberate and willful treachery, and so mistrusted the Northern Sindar.

That does not excuse Thingol’s attitude. He is stereotyping, and he is claiming kingship of all Beleriand while writing off a substantial portion of his own people, and this is unacceptable. One cannot claim rule of a people while simultaneously disdaining them and forswearing respinsibility for them. It is little surprise than the Northern Sindar largely joined themselves with various groups of Noldor and would have been glad of their arrival.

Doriath and the Noldor

This case is more complicated. I don’t like conflations of Thingol’s attitude towards the Fingolfinian and Fëanorian Noldor - or the Edain, for that matter - with anti-immigration sentiment. The basic concept of immigration is that you want to go to another country and live as a member of that country. When you enter an existing realm, claim its territory as your own, set up your own government, and justify it on the basis of “you’re not militarily able to stop us” that is not immigration. That is called an invasion, or annexation, or something of the sort. (Even if the realm in question is currently under invasion by enemies! Imagine if the British, after D-Day, had tried to annex half of France.)

(I will also note here that Thingol did not abandon the rest of the people of Beleriand prior to the Noldor’s arrival. The First Battle was the Doriathrim fighting alongside the Laiquendi. When Morgoth’s invasion became too large to fight on every front, the creation of the Girdle was the right choice. When assaulted by an overwhelming enemy force, the best, and indeed only militarily possible, option may be to withdraw as many of your people as possible to your fortress (as Thingol does - many of the Laiquendi and as many as possible of the grey-elves of Western Beleriand are evacuated to Doriath) and buckle down for a siege.)

And the Noldor didn’t come with the Sindar’s benefit in mind. (As I have noted before, they were not even away of Angband’s existence. The Return was focused on fighting one very dangerous individual, regaining the Silmarils, and setting up realms in - if we’re being generous to the Noldor - presumably unoccupied territory. If we’re not being generous, the aim can equally well be read as setting themselves up as the rulers of the elves of Middle-earth. If their goal, or even a tiny part of their goal, was “rescue the Sindar”, then they could have pitched that to Olwë to get him on board - “help us rescue your brother from Morgoth” is a way stronger argument than “you owe us, you cultureless barbarians”.)

So, given that they’re annexing his territory without even considering that it might be someone else’s territory, it’s very understandable that Thingol isn’t pleased by the Noldor.

On the other hand, Beleriand does benefit from the Noldor’s presence. Maedhros is quite correct when he points out that Thingol’s alternative to having the Nolder in northern Beleriand would be having orcs there [ironically, the Fëanorians do more harm to Doriath than orcs ever do, but that’s far in the future]. So given that the Sindar and Noldor have a common and very dangerous enemy, Thingol should at least try to work wth them. His deliberate isolation from the Noldor even prior to finding out about the Kinslaying comes across as prideful and petty. I am thinking particular of the absolutely minimal Doriathrin participation in Mereth Aderthad, when Fingolfin was specifically seeking to build a Beleriand-wide alliance, something that was in all their interests; and, addtionally, of not allowing the Nolofinwëans into Doriath. It automatically precludes any high-level negotiations or, just as importantly, any amount of in-person interaction that could lead to greater understanding. I can understand Thingol’s attitude towards Mereth Aderthad on some level - Fingolfin is in effect acting as though he is High King of Beleriand, something Thingol would resent - but it is nonetheless shortsighted.

It’s also worth noting, though, that acting with more tact and treating Thingol as King of Beleriand - as in fact he was throughout the Ages of the Stars - would not necessarily have posed any great difficulty or impeded Noldoran autonomy in decision-making in northern Beleriand. Notably, Thingol is on good terms with Finrod, gives him the location for building Nargothrond, and has no problems with him setting up a realm governing a large swath of West Beleriand. And yes, being relatives doesn’t hurt, but what stands out in this relationship is that Finrod treats Thingol with respect. He understand that Thingol knows more about Beleriand than him, and asks advice; when the Edain arrive, he’s the only one of the Noldor to consult with Thingol on his decisions (and that willingness to consult is what gets Thingol to agree to the Haladin settling in Brethil). And none of this prevents Finrod, or Orodreth after him, from having autonomy from Doriath in their decisions as lords of Nargothrond.

However, another interesting point is that Thingol’s early attitude towards the Noldor is not driven only by resentment of their infringements on his authority, but also by outright mistrust that doesn’t seem to be clearly grounded. Note that, after Galadriel tells Melian about Morgoth’s slaying of Finwë and theft of the Silmarils (which is well after Mereth Aderthad), Melian and Thingol talk, and Thingol says of the Noldor, “Yet all the more sure shall they be as allies against Morgoth, with whom it is not now to be thought they shall ever make treaty.” [Emphasis mine.] Which means that prior to this, he was genuinely worried about the Noldor allying with Morgoth! To paraphase The Order of the Stick, Thingol took Improved Paranoia several levels ago. (But he always seems to be paranoid about the wrong things. The Fëanorians are a threat, but not because of any possible league with Morgoth. Likewise, he is hostile to Beren because of dreams of a Man bringing doom to Doriath, but Thingol’s death and the first destruction of Doriath is instead set off by the actions of Húrin in bringing the cursed Nauglamír.)

So on the whole, neither the Noldor nor Thingol are behaving ideally in their early relations. After Thingol learns about Alqualondë, I find his hostility - especially to the Fëanorians - very warranted. These aren’t some distant, once-related group of elves, these are his brother’s people! And “willing to betray and attack their friends” is not a quality anyone is looking for in an ally, nor something that is going to lead to trust.

This also carries over to everything relating to the Leithian and the Silmaril. (Again, it is important to note with respect to the Leithain that Thingol states outright, after giving Beren the quest that he has zero expectation of - or desire for - Beren to obtain the Silmaril. It’s a combination suicide mission and “when pigs fly” statement, and most people who say “when pigs fly” aren’t aiming at the invention of animatronic flying pigs.) In a theoretical world where the Kinslaying didn’t happen and the Fëanorians had no involvement in the Quest of the Silmaril, they might have had a good shot at negotiating for it! (A much better shot than they had at getting it out of Angband, which they never even tried.) But of course Thingol would have no interest in handing it over to the people who, on top of the Kinslaying, also 1) betrayed his nephew and sent him to his death [that’s kind of on you as well, Elu], 2) kidnapped and attempted to rape his daughter; and 3) attempted to murder his daughter. And there should not be any reasonable expectation that he ought to do so! By their actions, the Fëanorians have forfeited any right to demand anything at all from Thingol, or from Beren and Lúthien, or from their descendents.

(This is, in fact, the very point made in the Doom of Mandos: their oath shall drive them and yet betray them. Every Fëanorian action driven by the oath is counterproductive to them obtaining any of the Silmarils.)

Conclusion

In short:

- Yes, the Noldor are imperialist in their goals, but in they end they’re not ruling anyone who isn’t willing to be ruled by them. And the Northern Sindar who are part of their realms are people who Thingol had explicitly written off, which doesn’t reflect well on him.

- Doriath is not as isolationist as it is often portrayed and has close relations with many of the peoples in Beleriand. It also does participate in the wars against Morgoth (I’ll go into that in more detail in my Edain post). And they have valid grievances against the Fëanorians. However, Thingol’s deliberate snubbing of the FIngolfinian Noldor (and even before he knew about the Kinslaying), despite the evident benefits of planning a common defense of Beleriand, is selfish and petty.

238 notes

·

View notes