#exxon chemical

Text

#center for climate integrity#cci#society for plastics#plastics industry association#vinyl institute#society for the plastics industry#plastics recycling foundation#epa#eastman chemical#exxon chemical#beyond plastics

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

In late May, 19 Republican attorneys general filed a complaint with the Supreme Court asking it to block climate change lawsuits seeking to recoup damages from fossil fuel companies.

All of the state attorneys general who participated in the legal action are members of the Republican Attorneys General Association (RAGA), which runs a cash-for-influence operation that coordinates the official actions of these GOP state AGs and sells its corporate funders access to them and their staff. The majority of all state attorneys general are listed as members of RAGA.

Where does RAGA get most of its funding? From the very same fossil fuel industry interests that its suit seeks to defend. In fact, the industry has pumped nearly $5.8 million into RAGA’s campaign coffers since Biden was elected in 2020.

The recent Supreme Court complaint has been deemed “highly unusual” by legal experts.

The attorneys general claim that Democratic states, which are bringing the climate-related suits at issue in state courts, are effectively trying to regulate interstate emissions or commerce, which are under the sole purview of the federal government. Fossil fuel companies have unsuccessfully made similar arguments in their own defense.

RAGA’s official actions — and those of its member attorneys general — closely align with the goals of its biggest donors.

The group, a registered political nonprofit that can raise unlimited amounts of cash from individuals and corporations, solicits annual membership fees from corporate donors in exchange for allowing those donors to shape legal policy via briefings and other interactions with member attorneys general.

A Center for Media and Democracy (CMD) analysis of IRS filings since November 24, 2020 shows that Koch Industries (which recently rebranded) leads as the largest fossil fuel industry donor to RAGA, having donated $1.3 million between 2021 and June 2024.

Other large donors include:

• American Petroleum Institute (API), the oil and gas industry’s largest trade association

• Southern Company Services, a gas and electric utility holding company

• Valero Services, a petroleum refiner

• NextEra Energy Resources, which runs both renewable and natural gas operations

• Anschutz Corporation, a Denver-based oil and gas company

• American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers, a major trade organization

• Exxon Mobil, one of the largest fossil fuel multinationals in the world

• National Mining Association, the leading coal and mineral industry trade organization

• American Chemical Council, which represents major petrochemical producers and refiners

Many of these donors are being sued for deceiving the public about the role fossil fuels play in worsening climate change: many states — including California, Connecticut, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Rhode Island — as well as local governments — such as the city of Chicago and counties in Oregon and Pennsylvania — have all filed suits against a mix of fossil fuel companies and their industry groups. In the cases brought by New York and Massachusetts, ExxonMobil found support from Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, who filed a friend-of-the-court brief in defense of the corporation.

Paxton has accepted $5.2 million in campaign contributions from the oil and gas industry over the past 10 years, according to data compiled by OpenSecrets and reviewed by CMD.

Fossil Fuel Contributions to the Republican Attorneys General Association

Includes aggregate contributions of $10K or more from the period November 2020 to March 2024.

Note: This funding compilation does not include law firms, front groups, or public relations outfits that work on behalf of fossil fuel clients, many of which use legal shells to shield themselves from outright scrutiny. For example, Koch Industries, through its astroturf operation Americans for Prosperity, has deployed a shell legal firm in a major Supreme Court case designed to dismantle the federal government’s regulatory authority.

CARRYING BIG OIL’S WATER

This is far from the first time RAGA members have banded together to try to defeat clean energy and environmental regulations. In 2014, the New York Times initially reported on how RAGA circulates fossil fuel industry propaganda opposing federal regulations.

The Times investigation revealed thousands of documents exposing how oil and gas companies cozied up to Republican attorneys general to push back against President Obama’s regulatory agenda. “Attorneys general in at least a dozen states are working with energy companies and other corporate interests, which in turn are providing them with record amounts of money for their political campaigns,” the investigation found. That effort, which RAGA dubbed the Rule of Law campaign, has since morphed into RAGA’s political action arm, the nonprofit Rule of Law Defense Fund (RLDF).

Since then, RAGA’s appetite to go to bat for the industry has only grown.

In 2015, less than two weeks after representatives from fossil fuel companies and related trade groups attended a RAGA conference, Republican AGs petitioned federal courts to block the Obama administration’s signature climate proposal, as CMD has previously reported. Additional reporting revealed collusion between Republican AGs and industry lobbyists to defend ExxonMobil and obstruct climate change legislation.

There was also the 2016 secret energy summit that RAGA held in West Virginia with industry leaders, along with private meetings with fossil fuel companies to coordinate how to shield ExxonMobil from legal scrutiny. Later that year, West Virginia Attorney General Patrick Morrisey — aided by 19 other Republican AGs — successfully brought a case before the court that hobbled Obama’s signature climate plan.

Morrisey is currently leading the Republican effort to take down an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulation that targets coal-fired power plants.

Often, the attorneys general bringing these cases share many of the same donors who backed the confirmation of Republican-appointed Supreme Court justices, as pointed out by the New York Times.

And in 2021, Republican attorneys general from 19 states sent a letter to the U.S. Senate committees on Environment and Public Works and on Energy and Natural Resources hoping to persuade senators to vote against additional regulations on highly polluting methane emissions, a leading contributor to global warming.

Since 2022, RLDF’s “ESG Working Group” has been coordinating actions taken by Republican AGs against sustainable investing. Communications from that group obtained by CMD show that it was investigating Morningstar/Sustainalytics and the Net-Zero Banking Alliance. Republican AGs announced investigations into the six largest banks for information on their involvement in the Net-Zero Banking Alliance later that year.

LEGACY OF RIGHT-WING ACTIONS

It’s not only about fossil fuels. Attorneys general who are members of — and financially backed by — RAGA have a long track record of pursuing right-wing agendas. In Mississippi, Attorney General Lynn Fitch helped bring the legal case that ultimately overturned Roe v. Wade. In Texas, Paxton has attempted to overturn the Affordable Care Act and sued the federal government over Title IX civil rights protections, and safeguards for seasonal workers, among other policy irritants to the far Right. With support from fellow Republican AGs, he also led one of many efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election.

In recent years, other pro-corporate major donors have included The Concord Fund, which is controlled by Trump’s “court whisperer” Leonard Leo, Big Tobacco, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Institute for Legal Reform.

#us politics#news#EXPOSEDbyCMD#truthout#2024#republicans#conservatives#attorneys general#us supreme court#climate change lawsuits#climate change#global warming#Republican Attorneys General Association#Center for Media and Democracy#Koch Industries#Americans for Prosperity#American Petroleum Institute#Southern Company Services#Valero Services#NextEra Energy Resources#Anschutz Corporation#American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers#Exxon Mobil#National Mining Association#American Chemical Council#ken paxton#Rule of Law Defense Fund#Patrick Morrisey#environmental protection agency#Net-Zero Banking Alliance

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Oil#Weird#unusual#petrolium#crude oil#chevron#Oil sands#oil spill#drill baby drill#drilling rig#deepwater horizon#Kuwaiti oil fires#Chemicals#Ecosystems#Offshore oil platform#pipeline#exxonmobil#exxon#Exxon Valdez#clean up#spills#oil field#BP#OPEC

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Plastics Are Poisoning Us

They both release and attract toxic chemicals, and appear everywhere from human placentas to chasms thirty-six thousand feet beneath the sea. Will we ever be rid of them?

— By Elizabeth Kolbert | June 26, 2023

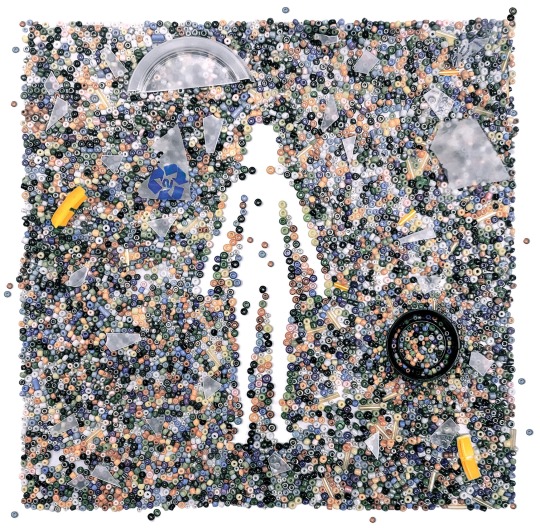

Annual production of plastic exceeds eight hundred billion pounds; much of it ends up as microplastics, spreading across the ocean. Illustration by Daniel Liévano

In 1863, when much of the United States was anguishing over the Civil War, an entrepreneur named Michael Phelan was fretting about billiard balls. At the time, the balls were made of ivory, preferably obtained from elephants from Ceylon—now Sri Lanka—whose tusks were thought to possess just the right density. Phelan, who owned a billiard hall and co-owned a billiard-table-manufacturing business, also wrote books about billiards and was a champion billiards player. Owing in good part to his efforts, the game had grown so popular that tusks from Ceylon—and, indeed, elephants more generally—were becoming scarce. He and a partner offered a ten-thousand-dollar reward to anyone who could come up with an ivory substitute.

A young printer from Albany, John Wesley Hyatt, learned about the offer and set to tinkering. In 1865, he patented a ball with a wooden core encased in ivory dust and shellac. Players were unimpressed. Next, Hyatt experimented with nitrocellulose, a material made by combining cotton or wood pulp with a mixture of nitric and sulfuric acids. He found that a certain type of nitrocellulose, when heated with camphor, yielded a shiny, tough material that could be molded into practically any shape. Hyatt’s brother and business partner dubbed the substance “celluloid.” The resulting balls were more popular with players, although, as Hyatt conceded, they, too, had their drawbacks. Nitrocellulose, also known as guncotton, is highly flammable. Two celluloid balls knocking together with sufficient force could set off a small explosion. A saloon owner in Colorado reported to Hyatt that, when this happened, “instantly every man in the room pulled a gun.”

It’s not clear that the Hyatt brothers ever collected from Phelan, but the invention proved to be its own reward. From celluloid billiard balls, the pair branched out into celluloid dentures, combs, brush handles, piano keys, and knickknacks. They touted the new material as a substitute not just for ivory but also for tortoiseshell and jewelry-grade coral. These, too, were running out, owing to slaughter and plunder. Celluloid, one of the Hyatts’ advertising pamphlets promised, would “give the elephant, the tortoise, and the coral insect a respite in their native haunts.”

Hyatt’s invention, often described as the world’s first commercially produced plastic, was followed a few decades later by Bakelite. Bakelite was followed by polyvinyl chloride, which was, in turn, followed by polyethylene, low-density polyethylene, polyester, polypropylene, Styrofoam, Plexiglas, Mylar, Teflon, polyethylene terephthalate (familiarly known as pet)—the list goes on and on. And on. Annual global production of plastic currently runs to more than eight hundred billion pounds. What was a problem of scarcity is now a problem of superabundance.

In the form of empty water bottles, used shopping bags, and tattered snack packages, plastic waste turns up pretty much everywhere today. It has been found at the bottom of the Mariana Trench, thirty-six thousand feet below sea level. It litters the beaches of Svalbard and the shores of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, in the Indian Ocean, most of which are uninhabited. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a collection of floating debris that stretches across six hundred thousand square miles between California and Hawaii, is thought to contain some 1.8 trillion plastic shards. Among the many creatures being done in by all this junk are corals, tortoises, and elephants—in particular, the elephants of Sri Lanka. In recent years, twenty of them have died after ingesting plastic at a landfill near the village of Pallakkadu.

How worried should we be about what’s become known as “the plastic pollution crisis”? And what can be done about it? These questions lie at the heart of several recent books that take up what one author calls “the plastic trap.”

“Without plastic we’d have no modern medicine or gadgets or wire insulation to keep our homes from burning down,” that author, Matt Simon, writes in “A Poison Like No Other: How Microplastics Corrupted Our Planet and Our Bodies.” “But with plastic we’ve contaminated every corner of Earth.”

Simon, a science journalist at Wired, is especially concerned about plastic’s tendency to devolve into microplastics. (Microplastics are usually defined as bits smaller than five millimetres across.) This process is taking place all the time, in many different ways. Plastic bags drift into the ocean, where, after being tossed around by the waves and bombarded with UV radiation, they fall apart. Tires today contain a wide variety of plastics; as they roll along, they abrade, sending clouds of particles spinning into the air. Clothes made with plastics, which now comprise most items for sale, are constantly shedding fibres, much the way dogs shed hairs. A study published a few years ago in the journal Nature Food found that preparing infant formula in a plastic bottle is a good way to degrade the bottle, so what babies end up drinking is a sort of plastic soup. In fact, it is now clear that children are feeding on microplastics even before they can eat. In 2021, researchers from Italy announced that they had found microplastics in human placentas. A few months later, researchers from Germany and Austria announced that they’d found microplastics in meconium—the technical term for an infant’s first poop.

The hazards of ingesting large pieces of plastic are pretty straightforward; they include choking and perforation of the intestinal tract. Animals that fill their guts with plastics eventually starve to death. The risks posed by microplastics are subtler, but not, Simon argues, any less serious. Plastics are made from by-products of oil and gas refining; many of the chemicals involved, such as benzene and vinyl chloride, are carcinogens. In addition to their main ingredients, plastics may contain any number of additives. Many of these—for example, polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFASs, which confer water resistance—are also suspected carcinogens. Many of the others have never been adequately tested.

As plastics fall apart, the chemicals that went into their manufacture can leak out. These can then combine to form new compounds, which may prove less dangerous than the originals—or more so. A couple of years ago, a team of American scientists subjected disposable shopping bags to several days of simulated sunlight, in order to mimic the conditions that they’d encounter flying or floating loose. The researchers found that a single bag from CVS leached more than thirteen thousand compounds; a bag from Walmart leached more than fifteen thousand. “It is becoming increasingly clear that plastics are not inert in the environment,” the team wrote. Steve Allen, a researcher at Canada’s Ocean Frontier Institute who specializes in microplastics, tells Simon, “If you’ve got an IQ above room temperature, you have to understand that this is not a good material to have in the environment.”

Microplastics, meanwhile, don’t just leach nasty chemicals; they attract them. “Persistent bioaccumulative and toxic substances,” or PBTs, are a hodgepodge of harmful compounds, including DDT and PCBs. Like microplastics, which are often referred to in the scientific literature as MPs, PBTs are everywhere these days. When PBTs encounter MPs, they preferentially adhere to them. “In effect, plastics are like magnets for PBTs” is how the Environmental Protection Agency has put it. Consuming microplastics is thus a good way to swallow old poisons.

Then, there’s the threat posed by the particles themselves. Microplastics—and in particular, it seems, microfibres—can get pulled deep into the lungs. People who work in the synthetic-textile industry, it has long been known, suffer from high rates of lung disease. Are we breathing in enough microfibres that we are all, in effect, becoming synthetic-textile workers? No one can say for sure, but, as Fay Couceiro, a researcher at England’s University of Portsmouth, observes to Simon, “We desperately need to find out.”

Whatever you had for dinner last night, the meal almost certainly left behind plastic in need of disposal. Before tossing your empty sour-cream tub or mostly empty ketchup bottle, you may have searched it for a number, and if you found one, inside a cheerful little triangle, you washed it out and set it aside to be recycled. You might also have imagined that with this effort you were doing your part to stem the global plastic-pollution tide.

The British journalist Oliver Franklin-Wallis used to be a believer. He religiously rinsed his plastics before depositing them in one of the five color-coded rubbish bins that he and his wife kept at their home in Royston, north of London. Then Franklin-Wallis decided to find out what was actually happening to his garbage. Disenchantment followed.

“If a product is seen as recycled, or recyclable, it makes us feel better about buying it,” he writes in “Wasteland: The Secret World of Waste and the Urgent Search for a Cleaner Future.” But all those little numbers inside the triangles “mostly serve to trick consumers.”

Franklin-Wallis became interested in the fate of his detritus just as the old order of Britain’s rubbish was collapsing. Up until 2017, most of the plastic waste collected in Europe and in the United States was shipped to China, as was most of the mixed paper. Then Beijing imposed a new policy, known as National Sword, that prohibited imports of yang laji, or “foreign garbage.” The move left waste haulers from California to Catalonia with millions of mildewy containers they couldn’t get rid of. “plastics pile up as china refuses to take the west’s recycling,” a January, 2018, headline in the Times read. “It’s tough times,” Simon Ellin, the chief executive of Britain’s Recycling Association, told the paper.

Trash, though, finds a way. Not long after China stopped taking in foreign garbage, waste entrepreneurs in other nations—Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Sri Lanka—started to accept it. Mom-and-pop plastic-recycling businesses sprang up in places where they were regulated laxly, if at all. Franklin-Wallis visited one such informal recycling plant, in New Delhi; the owner allowed him inside on the condition that he not reveal exactly how the business operates or where it is situated. He found workers in a fiendishly hot room feeding junk into a shredder. Workers in another, equally hot room fed the shreds into an extruder, which pumped out little gray pellets known as nurdles. The ventilation system consisted of an open window. “The thick fug of plastic fumes in the air left me dazed,” Franklin-Wallis writes.

Nurdles, which are key to manufacturing plastic products, are small enough to qualify as microplastics. (It’s been estimated that ten trillion nurdles a year leak into the oceans, most from shipping containers that tip overboard.) Usually, nurdles are composed of “virgin” polymers, but, as the New Delhi plant demonstrates, it is also possible to produce them from used plastic. The problem with the process, and with plastic recycling more generally, is that a polymer degrades each time it’s heated. Thus, even under ideal circumstances, plastic can be reused only a couple of times, and in the waste-management business very little is ideal. Franklin-Wallis toured a high-end recycling plant in northern England that handles pet, the material that most water and soda bottles are made from. He learned that nearly half the bales of pet that arrive at the plant can’t be reprocessed because they’re too contaminated, either by other kinds of plastic or by random crap. “Yield is a problem for us,” the plant’s commercial director concedes.

Franklin-Wallis comes to see plastic recycling as so much (potentially toxic) smoke and mirrors. Over the years, he writes, “a kind of playbook” has emerged. Under public pressure, a company like Coca-Cola or Nestlé pledges to insure that the packaging for its products gets recycled. When the pressure eases, it quietly abandons its pledge. Meanwhile, it lobbies against any kind of legislation that would restrict the sale of single-use plastics. Franklin-Wallis quotes Larry Thomas, the former president of the Society of the Plastics Industry, who once said, “If the public thinks recycling is working, then they are not going to be as concerned about the environment.”

Right around the time that Franklin-Wallis started tracking his trash, Eve O. Schaub decided to spend a year not producing any. Schaub, who has been described as a “stunt memoirist,” had previously spent a year avoiding sugar and forcing her family to do the same, an exercise she chronicled in a book titled “Year of No Sugar.” The year of no sugar was followed by “Year of No Clutter.” When she proposes a trash-free annum to her husband, he says he doubts it is possible. Her younger daughter begs her to wait until she goes away to college. Schaub plunges ahead anyway.

“As the beginning of the new year loomed, I was feeling pretty good about our chances,” she recalls in “Year of No Garbage.” “I mean, really. How hard could it be?”

What Schaub means by “no garbage” is not exactly no garbage. Under her scheme, refuse that can be composted or recycled is allowed, so her family can keep tossing out old cans and empty wine bottles along with food scraps. What turns out to be hard—really, really hard—is dealing with plastic.

At first, Schaub divides plastic waste into two varieties. There’s the kind with the little numbers, which her trash hauler accepts as part of its “single stream” recycling program and so, by her definition, doesn’t count as trash. Then, there’s the kind with no numbers, which isn’t supposed to go in the recycling bin and therefore does count. Schaub finds that even when she purchases something in a numbered container—guacamole, say—there’s usually a thin sheet of plastic under the lid that’s numberless. A lot of her time goes into rinsing off these sheets and other stray plastic bits and trying to figure out what to do with them. She is excited to find a company called TerraCycle, which promises—for a price—to “recycle the unrecyclable.” For a hundred and thirty-four dollars, she purchases a box that can be returned to TerraCycle filled with plastic packaging, and for an additional forty-two dollars she buys another box that can be filled with “oral care waste,” such as used toothpaste tubes. “I sent my TerraCycle Plastic Packaging box as densely packed with plastic as any box could be,” she writes.

Eventually, though, like Franklin-Wallis, Schaub comes to see that she’s been living a lie. Midway through her experiment, she signs up for an online course called Beyond Plastic Pollution, offered by Judith Enck, a former regional administrator for the E.P.A. Only containers labelled No. 1 (pet) and No. 2 (high-density polyethylene) get melted down with any regularity, Schaub learns, and to refashion the resulting nurdles into anything useful usually requires the addition of lots of new material. “No matter what your garbage service provider is telling you, numbers 3, 4, 6 and 7 are not getting recycled,” Schaub writes. (The italics are hers.) “Number 5 is a veeeery dubious maybe.”

TerraCycle, too, proves a disappointment. It gets sued for deceptive labelling and settles out of court. A documentary-film crew finds that dozens of bales of waste sent to the company for recycling have instead been shipped off to be burned at a cement kiln in Bulgaria. (According to the company’s founder, this is the result of an unfortunate mistake.)

“I had wanted so badly to believe that TerraCycle and Santa Claus and the Easter bunny were real, that I had been willing to overlook the fact that Santa’s handwriting looks suspiciously like Mom’s,” Schaub writes. Toward the end of the year, she concludes that pretty much all plastic waste—numbered, unnumbered, or shipped off in boxes—falls under her definition of garbage. She also concludes that, “in this day, age and culture,” such waste is pretty much impossible to avoid.

A few months ago, the E.P.A. issued a “draft national strategy to prevent plastic pollution.” Americans, the report noted, produce more plastic waste each year than the residents of any other country—almost five hundred pounds per person, nearly twice as much as the average European and sixteen times as much as the average Indian. The E.P.A. declared the “business-as-usual approach” to managing this waste to be “unsustainable.” At the top of its list of recommendations was “reduce the production and consumption” of single-use plastics.

Just about everyone who contemplates the “plastic pollution crisis” arrives at the same conclusion. Once a plastic bottle (or bag or takeout container) has been tossed, the odds of its ending up in landfill, on a faraway beach, or as tiny fragments drifting around in the ocean are high. The best way to alter these odds is not to create the bottle (or bag or container) in the first place.

“So long as we’re churning out single-use plastic . . . we’re trying to drain the tub without turning off the tap,” Simon writes. “We’ve got to cut it out.”

“We can’t rely on half-measures,” Schaub says. “We have to go to the source.” Her own local supermarket, in southern Vermont, stopped handing out plastic bags in late 2020, she notes. “Do you know what happened? Nothing. One day we were poisoning the environment with plastic bags in the name of ultra-convenience and the next? We weren’t.”

“We now know that we can’t start to reduce plastic pollution without a reduction of production,” Imari Walker-Franklin and Jenna Jambeck, both environmental engineers, observe in “Plastics,” forthcoming from M.I.T. Press. “Upstream and systemic change is needed.”

Of course, it’s a lot easier to talk about “turning off the tap” and changing the system than it is to actually do so. First, there are the political obstacles. For all intents and purposes, the plastics industry is a subsidiary of the fossil-fuel industry. ExxonMobil, for instance, is the world’s fourth-largest oil company and also its largest producer of virgin polymers. The connection means that any effort to reduce plastic consumption is bound to be resisted, either openly or surreptitiously, not just by companies such as Coca-Cola and Nestlé but also by corporations like Exxon and Shell. In March, 2022, diplomats from a hundred and seventy-five nations agreed to try to fashion a global treaty to “end plastic pollution.” At the first negotiating session, held later that year in Uruguay, the self-described High Ambition Coalition, which includes the members of the European Union as well as Ghana and Switzerland, insisted that the treaty include mandatory measures that apply to all countries. This idea was opposed by major oil-producing nations, including the U.S., which has called for a “country-driven” approach. According to the environmental group Greenpeace, lobbyists for the “major fossil fuel companies were out in force” at the session.

There are also practical hurdles. Precisely because plastic is now ubiquitous, it’s difficult to imagine how to replace all of it, or even much of it. Even in cases where substitutes are available, it’s not always clear that they’re preferable. Franklin-Wallis cites a 2018 study by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency which analyzed how different kinds of shopping bags compare in terms of life-cycle impacts. The study found that, to have a lower environmental impact than a plastic bag, a paper bag would have to be used forty-three times and a cotton tote would have to be used an astonishing seventy-one hundred times. “How many of those bags will last that long?” Franklin-Wallis asks. Walker-Franklin and Jambeck also note that exchanging plastic for other materials may involve “tradeoffs,” including “energy and water use and carbon emissions.” When Schaub’s supermarket stopped handing out plastic shopping bags, it may have reduced one problem only to exacerbate others—deforestation, say, or pesticide use.

“In the grand scheme of human existence, it wasn’t that long ago that we got along just fine without plastic,” Simon points out. This is true. It also wasn’t all that long ago that we got along just fine without Coca-Cola or packaged guacamole or six-ounce bottles of water or takeout everything. To make a significant dent in plastic waste—and certainly to “end plastic pollution”—will probably require not just substitution but elimination. If much of contemporary life is wrapped up in plastic, and the result of this is that we are poisoning our kids, ourselves, and our ecosystems, then contemporary life may need to be rethought. The question is what matters to us, and whether we’re willing to ask ourselves that question. ♦

— Published in the print edition of the July 3, 2023, The New Yorker Issue, with the headline “A Trillion Little Pieces.”

#Plastic Poisoning#Toxic Chemicals#On Earth and Under Seas#Microplastics#Plastic Pollution#PFASs#PBTs#MPs DDT & PCBs#E.P.A.#MIT Press#Coca Cola | Nestlé | Exxon | Shell#Greenpeace

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mass Spectrometer circa 1970s / Dave Chappelle Quote (2021)

photo by Henry Earle Lumpkin

at Exxon Research Analytical Laboratories - Baytown, TX (1970s)

“Modern mass spectrometry has advanced dramatically since the 1970s, creating a demand for ever-improving mass spectral reference standards to ensure accurate chemical identifications.”

Courtesy of the Chemical Heritage Foundation Collections

#Henry Earle Lumpkin#Mass Spectrometer#Dave Chappelle#Quote#Exxon Research Analytical Laboratory#Baytown#Texas#Chemical Heritage Foundation#1970s#2021

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

DUNG MÔI CÔNG NGHIỆP LÀ GÌ? MUA Ở ĐÂU TỐT?

CÔNG TY TNHH MỘT THÀNH VIÊN HÓA CHẤT 3T

Văn Phòng: 6/5 Tân Hòa, Tân Hiệp , Hóc Môn , Thành Phố Hồ Chí Minh

#3tchemical#solvent#chemical#best price#price#giá tốt#sk geocentric Vietnam#exxon mobil Vietnam#Hanwah Vietnam#Sinopec Vietnam#Basf Vietnam#Vietnam#LG Chem Vietnam#Yueyang Changde Vietnam#Kellin Vietnam#Dow Vietnam

0 notes

Text

Exxon Mobil Eyes Potential Megadeal With Shale Driller Pioneer

Oil-and-gas giant has held informal, early-stage talks to buy the $49 billion-market cap Pioneer Natural Resources

https://www.wsj.com/articles/exxon-mobil-eyes-potential-mega-deal-with-shale-driller-pioneer-c48a4747 $xom $pxd #oott #oilandgas #shalegas #shaleoil #mergers #investor #oott #ennovance (chart bbg)

0 notes

Text

re: ohio chemical disaster

OP of the post I reblogged earlier regarding this turned off reblogs (understandable have a nice day) but I got a request to put the information in its own post, so here.

First thing: PLEASE be careful about claims that "The Media" is suppressing something as part of a malicious agenda, or that an event has been purposefully manufactured by "The Media" to distract from something else.

Not only is this a really common disinformation tactic (not only urging you to share/reblog quickly, but discouraging you from fact checking), treating "The Media" as a monolithic entity with purposeful agency and a specific, malicious agenda—particularly one that manufactures events to "distract" from other events—is a red flag for conspiracy theories.

There's already a post in the tag attributing the supposed lack of media coverage to "reptilians." Please connect the dots here.

Second—"the news isn't focusing on this as much as I think they should" is not a media blackout. Every major USA news source is reporting on the Ohio train derailment. Googling returns at least 4 pages of results from major news media sources. Even just googling "Ohio" gets you plenty of results about it.

This is an unusual amount of media attention for a U.S. environmental disaster.

Because this kind of thing happens all the damn time.

The "media blackout" narrative gives the impression that this is an unusual event that isn't receiving wall to wall coverage only because it's being suppressed—when the reality is that similar disasters happen a lot, and hardly ever get the attention the Ohio disaster is getting.

Consider this example, not too far from my local area: A few years ago, almost 2,000 tons of radioactive fracking waste were illegally dumped in an Eastern Kentucky municipal landfill, directly across from a middle school. Leachate from that landfill goes into the Kentucky River, which is where most of the central part of the state gets its drinking water. As far as we know, the radioactive waste isn't leaking yet, but it could start leaking at any time.

Zero national news sources covered this. Why? If I was to hazard a guess, I would say "because it's business as usual for the fossil fuel industry."

Consider also the case of Martin County, KY, which has had foul-smelling, contaminated drinking water for decades. Former coal country in Appalachia is poisoned and toxic, and laws have little power to punish the companies that created the destruction.

What happened in Ohio is just a little window into a whole world of horrors.

The Martin County coal slurry spill that is still poisoning the water 20 years later killed literally everything in the water for miles downstream (a book Mom read said 70 miles of the Ohio river were made completely lifeless). It was 30 times larger than the Exxon-Valdez oil spill, and it was in some sense "covered up"—in the sense that the Bush administration shut down the investigation because the Republicans are buddies with the fossil fuel industry, and proceeded to relax regulations even further.

Seriously, read that wiki article to get pissed enough to eat glass.

Hopefully the Ohio chemical spill will inspire real action to institute regulations to prevent shit like this from ever happening again. It's not the end of the world. It's not radically different from what industries have been causing the whole damn time. It is pretty bad.

I would urge everyone to actually search up information about it instead of getting news from Tiktok or Twitter, because the more false information gets distributed, the less momentum any effort to respond with improved regulations and changes to prevent future disasters will have. Plenty of facts here *are* public and being publicly discussed and pretending that they're not is actively detrimental.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Dow promised to turn sneakers into playground surfaces, then dumped them in Indonesia

Dow Chemicals plastered Singapore with ads for its sneaker recycling program, promising to turn old shoes into playground tracks. But the shoes it collected in its “recycling” bins were illegally dumped in Indonesia. This isn’t an aberration: it’s how nearly all plastic recycling has always worked.

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/02/26/career-criminals/#fool-me-twice-three-times-four-times-a-hundred-times

Plastic recycling’s origin story starts in 1973, when Exxon’s scientists concluded that plastic recycling would never, ever be cost-effective (#ExxonKnew about this, too). Exxon sprang into action: they popularized the recycling circular arrow logo and backed “anti-littering” campaigns that blamed the rising tide of immortal, toxic garbage on peoples’ laziness.

https://pluralistic.net/2020/09/14/they-knew/#doing-it-again

Remember the campaign where an Italian guy dressed like a Native American shed a single tear as he contemplated plastic litter? Funded by the plastic industry, as a way of shifting blame for plastic waste from the wealthy, powerful corporations who lied about plastics recycling to the individuals who believed their lies:

https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-perspec-indian-crying-environment-ads-pollution-1123-20171113-story.html

When I was a kid in Ontario, we had centralized, regulated, reusable bottle depots — beer and soda bottles came in standard sizes, differentiated by paper labels that could be pressure-washed off. When you were done with your bottle, you returned it for a deposit and it got washed and returned to bottlers to be refilled again and again and again.

After intense lobbying from soda companies, brewers and the plastic industry, that program was replaced with curbside “blue boxes” that promised to recycle our plastic waste. 90% of the plastics created has never been — and will never be — recycled. Today, the plastic industry plans on tripling the amount of single-use plastic in use worldwide:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/04/26/plastic-fatalistic/#recycled-lies

You know those ads from companies like Bluetriton (formerly “Nestle Waters”) that promise that your single-use plastic bottles are “100% recyclable…and can be used for new bottles and all sorts of new, reusable things?”

Bluetriton is a private equity-backed rollup that has absorbed most of the bottled water companies you’re familiar with, including Poland Spring, Pure Life, Splash, Ozarka, and Arrowhead. When they were sued in DC for making false claims about their “recyclable” water-bottles, their defense was that these were “non-actionable puffery.” According to Bluetriton, when it described itself as “a guardian of sustainable resources” and “a company who, at its core, cares about water,” it was being “vague and hyperbolic.”

https://pluralistic.net/2022/04/26/plastic-fatalistic/#recycled-lies

With this high standard for plastic recycling, Dow’s Singapore scam shouldn’t come as a surprise, but it seems to have surprised the government of Singapore. Writing for Reuters, Joe Brock, Yuddy Cahya Budiman and Joseph Campbell describe how they caught Dow red-handed:

https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/global-plastic-dow-shoes/

The method is actually pretty straightforward: Reuters hid tracking devices in cavities in the soles of sneakers, dropped them in one of Dow’s collection bins, and then followed them. The shoes were passed onto Dow’s subcontractor, Yok Impex Pte Ltd, who sent them hopping from island to island throughout Indonesia, until they ended up in junk-markets.

Not all the shoes, though — one pair was simply moved from Dow’s collection bin to a donation bin at a Singaporean community center. Of the 11 pairs that Reuters tracked, not one ended up at a recycling facility. So much for Dow’s slogan: “Others see an old shoe. We see the future.”

Dow blamed all this on Yok Impex, but didn’t explain why its “recycling” program involved a company whose sole trade is exporting used clothing. Dow promised to cancel its deal with Yok Impex, but Yok Impex’s accountant told Reuters that the deal would be remain in place until the end of the contract. Yok Impex, meanwhile, shifted the blame to the low-waged women who sort through the clothing donations it takes in from across Singapore.

Indonesia bans bulk imports of used clothes, on the grounds that used clothes are unhygenic, displace the local textiles industry, and shipments contain high volumes of waste that ends up in Indonesian incinerators, landfills and rivers.

In other words, Singaporeans thought they were saving the planet by putting their shoes in Dow bins, but they were really sending those shoes on a long journey to an unlicensed dump. Dow enlisted schoolchildren in used-shoe collection drives, making upbeat videos that featured students like Zhang Youjia boasting that they “contributed 15 pairs of shoes.”

Dow does this all the time. In 2021, Dow’s “breakthrough technology to turn plastic waste into clean fuel” in Idaho was revealed to be a plain old incinerator:

https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/environment-plastic-oil-recycling/

Also in 2021, in India, a Dow program to “use high-tech machinery to transform the [plastic from the Ganges] into clean fuel” was revealed to have ceased operations — but was still collecting plastic and promising that it was all being turned into fuel:

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-environment-plastic-insight-idUSKBN29N024

Dow operates a nearly identical “shoe recycling” program in neighboring Malaysia, and did not return Reuters’ requests for comment as to whether the shoes collected for “recycling” in the far more populous nation were also being illegally dumped offshore.

The global business lobby loves the idea of “personal responsibility” and its evil twin, “caveat emptor.” Its pet economists worship the idea of “revealed preferences,” claiming that when we use plastic, we may claim that we don’t want to have our bodies poisoned with immortal, toxic microplastics, that we don’t want our land and waters despoiled — but we actually love it, because otherwise we’d “vote with our wallets” for something else.

The obvious advantage of telling people to vote with their wallets is that the less money you have in your wallet, the fewer votes you get. Companies like Dow have used their access to the capital markets (a fancy phrase for “rich people”) to gobble up their competitors, eliminating “wasteful competition” and piling up massive profits. Those profits are laundered into policy — like replacing Ontario’s zero-waste refillable bottle system with a “recycling” system that sent plastics to the ends of the Earth to be set on fire or buried or dumped in the sea.

The ruling class’s pet economists have a name for this policy laundering: they call it “regulatory capture.” Now, when you hear “regulatory capture,” you might think about companies that get so big that they are able to boss governments around, with the obvious answer that companies need to be regulated before they get too big to jail:

https://doctorow.medium.com/small-government-fd5870a9462e

But that’s not how elite economists talk about regulatory capture: for them, capture starts with the very existence of regulators. For them, any government agency that proposes to protect the public from corporate fraud and murder inevitably becomes an agent of the corporations it is supposed to rein in, so the only answer is to eliminate regulators altogether:

https://doctorow.medium.com/regulatory-capture-59b2013e2526

This nihilism lets rich people blame the rest of us for their sins: “if you didn’t want your children to roast or freeze to death in the climate emergency, you should have sold your car and used the subway (that we bribed your city not to build).”

Nihilism is contagious. Think of the music industry: before Napster, 80% of the music ever recorded was not for sale, banished to the scrapheap of history and the vaults of record companies who paid farcically low sums to their artists.

During the File Sharing Wars, listeners were excoriated for failing to pay for music — much of which wasn’t for sale in the first place. But today, fans overwhelmingly pay for Spotify, a streaming service that notoriously pays musicians infinitesimal sums for their work.

Spotify is a creature of the Big Three labels — Sony, Universal and Warner — who own 70% of all the world’s recorded music copyrights and 65% of all the world’s music publishing. The rock-bottom per-stream prices that Spotify pays were set by the Big Three. Why would the labels want less money from Spotify?

Simple: as co-owners of Spotify, they make more money when Spotify pays less for music. Musicians have a claim on the money they take out of Spotify as royalties — but dividends, buybacks and capital gains from Spotify are the labels’ to use as they see fit. They can share that bounty with some artists, all artists, or no artists.

Not only that, but the Big Three’s deal with Spotify includes a “most favored nation” clause, which means that the independent artists who aren’t under Sony/UMG/Warner’s thumb have to take the rock-bottom rate the Big Three insisted on — likewise the small labels who compete with the Big Three. The difference is that none of these artists and small labels have massive portfolios of Spotify stock, nor do they get free advertising on Spotify, or free inclusion on hot Spotify playlists, or monthly minimum payouts from Spotify.

The idea that we shop at the wrong kind of monopolist in the wrong way is a recipe for absolute despair. It doesn’t matter whether you listen to music with the Big Tech-owned monopoly service (Youtube) or the Big Content-owned monopoly service (Spotify). The money you hand over to these giant companies goes to artists the same way that the sneakers you put in a Dow collection bin goes to a recycling plant.

Think of the billions of human labor hours we all spent washing and sorting our plastics for a recycling program that didn’t exist and will never exist — imagine if we’d spent that time and energy demanding that our politicians hold petrochemical companies to account instead.

At the end of Break ’Em Up, Zephyr Teachout’s outstanding 2020 book on monopolies, Teachout has some choice words for “consumerism” as a theory of change. She writes that if you’re on your way to a protest against a new Amazon warehouse but you never make it because you waste too much time looking for a mom-and-pop stationers to sell you a marker to write your protest sign, Amazon wins:

https://pluralistic.net/2020/07/29/break-em-up/#break-em-up

The problem isn’t that you shop the wrong way. Yes, by all means, support the creators and producers you care about in the way that they prefer, but keep your eye on the prize. Structural problems don’t have individual solutions. The problem isn’t that you have chosen single-use plastics — it’s that in our world everything for sale is packaged in single-use plastics. The problem isn’t that you’ve bought a subscription to the wrong music streaming service — it’s that labels have been allowed to buy all their competitors, creators’ unions have been smashed and degraded, and giant accounting scams by big companies generate minuscule fines.

The good news is that after 40 years of despair inducing regulatory nihilism and “vote with your wallet” talk, we’re finally paying attention to systemic problems, with a new generation of trustbusting radicals working around the world to end corporate impunity.

Dow is a repeat offender. A repeat, repeat offender. Chrissakes, they’re the linear descendants of Union Carbide, the company that poisoned Bhopal:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhopal_disaster

They shouldn’t be trusted to run a lemonade stand, let alone a “recycling” program. The same goes for Big Tech and Big Content company and the markets for creative labor. These companies have repeatedly demonstrated their unfitness, their habitual deception and immorality. These companies have captured their regulators, repeatedly, so we need better regulators — and weaker companies.

The thing I love about Teachout’s book is that it talks about what we should be demanding from our governments — it’s a manifesto for a movement against corporate power, not a movement for “responsible consumerism.” That was the template that Rebecca Giblin and I followed when we wrote Chokepoint Capitalism, our book about the brutal, corrupt creative labor market:

https://chokepointcapitalism.com/

We have a chapter on Spotify (multiple chapters, in fact!). For our audiobook, we made that chapter a “Spotify Exclusive” — it’s the only part of the book you can get on Spotify, and it’s free:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/09/12/streaming-doesnt-pay/#stunt-publishing

Next Thu (Mar 2) I’ll be in Brussels for Antitrust, Regulation and the Political Economy, along with a who’s-who of European and US trustbusters. It’s livestreamed, and both in-person and virtual attendance are free. On Fri (Mar 3), I’ll be in Graz for the Elevate Festival.

[Image ID: A woman kneeling to tie her running shoe. She stands on a background of plastic waste. In the top right corner is the logo for Dow chemicals. Below it is the Dow slogan, 'Others see an old shoe. We see the future.']

919 notes

·

View notes

Text

dont never drink one of those limoncello bang energy drinks. my fucking god bro. shit tastes like straight research chemicals. im talking monsanto. thats that superfund slurp. this drink is not a place of honor. some drop and run drank. no fucking way bro. you do not want that exxon elixir. youll be sipping on some soylent green. told my children i love them. time for them to explore this galaxy alone. drink that makes you feel like its 25 or 6 to 4. feels like the enemy is spinning up the photon torpedoes and the ionic stellar dust is disabling our weapon systems. no sir. this shit tastes like fauci highball. he drank this shit in district 9. i just heard them play a sorrowful refrain on the mandachord. this shit tastes like a lexus dealership. not fit for man nor beast.

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good Climate News

A satellite that will exclusively track methane emissions from the oil and gas industry launched into orbit last week.

New Zealand has become the first country in the world to ban PFAS chemicals in cosmetics which will takek's effect in 2026d climate news:

Chicago has become the latest city to sue the fossil fuel industry in order to pay for both climate damages and action.

Japan has become the first country in the world to issue sovereign bonds for climate action projects with around $13 billion expected to be committed.

Sources:

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

You know AIPAC isn’t even in the top 50 special interest lobbies in Washington DC right? You act like it’s some all powerful nefarious group of Zionist puppet masters controlling the US government. When in fact it’s just one of literally thousands of lobbying groups each trying to get their own interests acknowledged. There’s a big ANTI-Israel lobby in Washington too. And huge lobbies for many other countries (some of the biggest spenders include China, the UAE, Qatar, Liberia, Japan, Saudi Arabia, the frickin Marshall Islands for some reason.) Weird how you’re so obsessed with AIPAC when they are out-numbered and out-spent by dozens of other organizations and countries in DC. For reference? The lobby representing the interests of Native American casinos generally outspends AIPAC. Who are the top lobbying spenders of recent years you ask? The National Association of Realtors, the American Hospital Association, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the American Medical Association, Blue Cross/Blue Shield, Business Roundtable, General Electric, Boeing, Lockheed Martin, AT&T, Verizon, AARP, Exxon Mobil, the National Association of Broadcasters, Edison Electric Institute, Comcast, Amazon, Meta, Pfizer, Unilever, Dow Chemical, FedEx, Open Society Foundation (that’s Israel-critical George Soros. I’m sure you’ve heard of him.) All have spent vastly more than AIPAC. You can look all this up on Open Secrets dot org or the Office of Public Records, btw. 182 different countries (since 2016) spend millions on lobbying activities in DC. Look up FARA on Wikipedia if you’re bored/interested.

(Can’t WAIT for you to find out about Liberia, personally. The origins, the history, the current reality, oof. It’s a LOT.)

#am yisrael chai#gaza genocide#israel#palestine#palestine genocide#free gaza#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#fuck israel#gaza strip#international court of justice#international criminal court#gaza#anti zionisim#tel aviv#all eyes on rafah#rafah#zionsim is terrorism#zionistterror#zionist#free palestine#idf terrorists#i stand with israel

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The world isn’t on track to meet its climate goals — and it’s the public’s fault, a leading oil company CEO told journalists.

Exxon Mobil Corp. CEO Darren Woods told editors from Fortune that the world has “waited too long” to begin investing in a broader suite of technologies to slow planetary heating.

That heating is largely caused by the burning of fossil fuels, and much of the current impacts of that combustion — rising temperatures, extreme weather — were predicted by Exxon scientists almost half a century ago.

The company’s 1970s and 1980s projections were “at least as skillful as, those of independent academic and government models,” according to a 2023 Harvard study.

Since taking over from former CEO Rex Tillerson, Woods has walked a tightrope between acknowledging the critical problem of climate change — as well as the role of fossil fuels in helping drive it — while insisting fossil fuels must also provide the solution.

In comments before last year’s United Nations Climate Conference (COP28), Woods made a forceful case for carbon capture and storage, a technology in which the planet-heating chemicals released by burning fossil fuels are collected and stored underground.

“While renewable energy is essential to help the world achieve net zero, it is not sufficient,” he said. “Wind and solar alone can’t solve emissions in the industrial sectors that are at the heart of a modern society.”

International experts agree with the idea in the broadest strokes.

Carbon capture marks an essential component of the transition to “net zero,” in which no new chemicals like carbon dioxide or methane reach — and heat — the atmosphere, according to a report by International Energy Agency (IEA) last year.

But the remaining question is how much carbon capture will be needed, which depends on the future role of fossil fuels.

While this technology is feasible, it is very expensive — particularly in a paradigm in which new renewables already outcompete fossil fuels on price.

And the fossil fuel industry hasn’t been spending money on developing carbon capture technology, IEA head Fatih Birol wrote last year on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter.

To be part of a climate solution, Birol added, the fossil fuel industry must “let go of the illusion that implausibly large amounts of carbon capture are the solution.”

He noted that capturing and storing current fossil fuel emissions would require a thousand-fold leap in annual investment from $4 billion in 2022 to $3.5 trillion.

In his comments Tuesday, Woods argued the “dirty secret” is that customers weren’t willing to pay for the added cost of cleaner fossil fuels.

Referring to carbon capture, Woods said Exxon has “tabled proposals” with governments “to get out there and start down this path using existing technology.”

“People can’t afford it, and governments around the world rightly know that their constituents will have real concerns,” he added. “So we’ve got to find a way to get the cost down to grow the utility of the solution, and make it more available and more affordable, so that you can begin the [clean energy] transition.”

For example, he said Exxon “could, today, make sustainable aviation fuel for the airline business. But the airline companies can’t afford to pay.”

Woods blamed “activists” for trying to exclude the fossil fuel industry from the fight to slow rising temperatures, even though the sector is “the industry that has the most capacity and the highest potential for helping with some of the technologies.”

That is an increasingly controversial argument. Across the world, wind and solar plants with giant attached batteries are outcompeting gas plants, though battery life still needs to be longer to make renewable power truly dispatchable.

Carbon capture is “an answer in search of a question,” Gregory Nemet, a public policy professor at the University of Wisconsin, told The Hill last year.

“If your question is what to do about climate change, your answer is one thing,” he said — likely a massive buildout in solar, wind and batteries.

But for fossil fuel companies asking “‘What is the role for natural gas in a carbon-constrained world?’ — well, maybe carbon capture has to be part of your answer.”

In the background of Woods’s comments about customers’ unwillingness to pay for cleaner fossil fuels is a bigger debate over price in general.

This spring, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) will release its finalized rule on companies’ climate disclosures.

That much-anticipated rule will weigh in on the key question of whose responsibility it is to account for emissions — the customer who burns them (Scope II), or the fossil fuel company that produces them (Scope III).

Exxon has long argued for Scope II, based on the idea that it provides a product and is not responsible for how customers use it.

Last week, Reuters reported that the SEC would likely drop Scope III, a positive development for the companies.

Woods argued last year that SEC Scope III rules would cause Exxon to produce less fossil fuels — which he said would perversely raise global emissions, as its products were replaced by dirtier production elsewhere.

This broad idea — that fossil fuels use can only be cleaned up on the “demand side” — is one some economists dispute.

For the U.S. to decarbonize in an orderly fashion, “restrictive supply-side policies that curtail fossil fuel extraction and support workers and communities must play a role,” Rutgers University economists Mark Paul and Lina Moe wrote last year.

Without concrete moves to plan for a reduction in the fossil fuel supply, “the end of fossil fuels will be a chaotic collapse where workers, communities, and the environment suffer,” they added.

But Woods’s comments Tuesday doubled down on the claim that the energy transition will succeed only when end-users pay the price.

“People who are generating the emissions need to be aware of [it] and pay the price,” Woods said. “That’s ultimately how you solve the problem.”

#us politics#news#the hill#2024#carbon emissions#green energy#climate change#climate crisis#exxon mobil#Darren Woods#United Nations Climate Conference#COP28#carbon capture and storage#renewable energy#International Energy Agency#Fatih Birol#fossil fuels#Securities and Exchange Commission#emissions

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

fuck it, midgley discourse in my notes, we ball.

Time to talk about one of my favourite regulatory archdevils, Dr. Robert Arthur Kehoe.

I love that this is his Wikipedia photo. The slightly raised eyebrow. The faint but noticable cheekbones. The level, slightly superior expression. Even just the angle of the shot. This is a man who’s about to give a gloating monologue to James Bond.

Kehoe was a medical doctor with a specialty in toxicology and one of the early lions of what we now call “occupational health” - that is, what does and doesn’t make a workplace a safe place to work in. At the time, this was basically an open question - the first worker’s compensation laws only went on the books in the 1880s, and were often scrambling to respond to health risks. OSHA isn’t even a twinkle in the eye of the ten-year-old and politically uncomplicated Richard Nixon, whose family lemon plantation just failed.

The Background

This lack of occupational health standards is rapidly becoming a big problem for a “little” company called the Ethyl Gasoline Corporation (actually a corporate chimera of General Motors, Standard Oil of New Jersey - who you now know as Exxon, and DuPont - who you now might still know as DuPont but is also a few other companies, it’s complicated). Workers at Ethyl’s plants were suffering from neurological disorders, which culminated in the deaths of five workers, injury to many more, and at least one worker, Joseph G. Leslie, being secretly committed to a psychiatric institution by the company, who publicly declared him dead.

See, Ethyl (through GM) owned the patent to a little chemical called tetraethyllead, which was being promoted as the solution to engine knocking - a performance issue in older automobiles. Ethyl’s CEO, Charles Kettering, had previously been GM’s head of research, where he had tasked a talented but retroactively very unfortunate chemist by the name of Charles Midgley, Jr. with developing a compound to combat knocking.

Midgley first figured out that a blend of ethanol with the gasoline would help solve the problem. GM did not like this, because ethanol was so easy to make that they’d never turn a profit on producing ethanol-blended gasoline. So Kettering told Midgley to try again, and he did - he found a tellurium compound that would work great for solving knocking. It stank to high heaven, so GM said no, try again, and finally Midgley settled on tetraethyllead, and GM immediately patented it for use in fuels.

Tetraethyllead had some downsides. It is mostly known today for its environmental effects, particularly the massive scale of lead poisoning from lead and lead oxide emissions caused by TEL combustion. These weren’t really in the picture in the 1920s, where concerns about large-scale environmental impacts of industrialisation were considered a fringe view or even outright pseudoscientific. Instead, the issue was the toxicity of TEL itself - it was already known to be far more poisonous than lead or lead oxides, as the organic structure of the compound allowed it to pass the blood-brain barrier, where it would then break down and cause lead poisoning to set in extremely quickly.

It’s this exposure to TEL that caused the initial controversy, and lead to things like the infamous publicity stunt where Midgley dunked his hands in leaded gasoline and took a big ol’ sniff to prove how safe it was, never mind that he had just been recovering from lead poisoning weeks earlier. Even if TEL is dangerous, claimed Midgley, finished Ethyl gasoline was perfectly safe for consumers - officially, the problem was that workers weren’t following adequate safety standards. He would also repeatedly deny the existence of any appropriate alternatives to TEL, including the two that he had previously suggested to GM and the several other alternatives used by rival fuel companies domestic and international.

Kettering and Midgley’s public statements are contradicted by private correspondence, which detailed several alternatives including ethanol. That said, these concerns were all about the toxicity of tetraethyllead, not the combustion byproducts which would later give it its infamy. There is some also dispute as to the extent that Kettering and Midgley viewed TEL as the ultimate solution to knocking, or an intermediate fuel to allow the economic development of high-compression motors that could be converted to run on ethanol - though this was motivated not by environmental concerns, but the growing belief that gasoline supplies would soon be depleted. (Of course, that wasn’t the case.)

My general view of Midgley as a scientist is that he came up with genuinely brilliant solutions to the problems he was posed, that happened to have large-scale ecological effects he couldn’t have anticipated. But he certainly wasn’t some hapless victim in this either, and was at the very least the direct architect of TEL’s version of the “no alternatives” narrative, which helped shut down early investigations into the dangers of TEL.

But this isn’t about Midgley. Let’s introduce our main man.

The Safety Doctor

“During the entire history of man on this earth, he has had lead in his body. He has had lead in his food, he has had lead in his drinking water... the question is not whether lead per se is dangerous, but whether a certain concentration of lead in his body is dangerous.“

- Robert A. Kehoe, Antiknock compounds and public health.

If the official line at Ethyl was that the workers were to blame for everything, the private line was clearly that they needed better safety standards. To this end, Kettering hired a toxicologist named Robert Arthur Kehoe as the company’s chief medical consultant. Kehoe’s job was to research the impact of TEL on workers and improve safety procedures - which he did. This made him a leading figure in the emerging field of occupational health - working for a major chemical company was less a conflict of interest and more proof of expertise.

Kehoe would found the Kettering Laboratory of Applied Physiology, touted as the “first university-based laboratory devoted to toxicological problems peculiar to industry”. Named for Kettering, it would be financed primarily by Ethyl, DuPont, and GM, and it would come to define the early approach to science and occupational health.

After Kehoe’s changes were implemented, experts studied garage workers who were expected to be exposed to TEL. The review found some concerns with blood health, but no major signs of lead poisoning; while the question of environmental exposure was raised, the study was grounded in Ethyl’s own laboratory results, which claimed that only 15% of the lead in gasoline could be found in emissions (with another 15% being found in engine oil, and the remaining 70%... assumed to stay in the engine). This was accepted at face value without any independent sampling of street-level lead.

The committee concluded there was no reason to ban leaded gasoline - however, they called for continued investigation, as well as research into alternatives to tetraethyllead - particularly ethyl alcohol. These requests were ignored.

Kehoe soon became the go-to expert for the lead industry, and developed the early doctrine for testing dangers of exposure in the workplace. Kehoe worked from the baseline assumption that, if a compound existed, people would naturally be exposed to it in some capacity - the burden then lay on determining the dose where this became a problem.

The origin of this doctrine is sometimes attributed to Midgley, but its application in a legal and regulatory sense would become known as the Kehoe Rule: regulation is appropriate “if it can be shown that an actual danger is had as a result on the basis of fact”, but that technology should not “be thrown into the discard on the basis of opinions”. Kehoe’s “facts” were rooted in a simple chain of deductions:

As lead exists in nature, people are exposed to it naturally.

As people do not all have lead poisoning, the body must then have means to counteract lead poisoning.

Thus, there is some baseline level of lead exposure which the body is capable of handling without lasting harm.

Thus, leaded gasoline is only a risk if it can be shown that emissions exceed that baseline level.

Environmental samples seemed to support Kehoe’s argument. There was a baseline level of lead in the environment, even using ice and soil samples deep enough to predate industrialisation, and people had greater exposure to lead from food or drink than from the atmosphere. Kehoe and his colleagues conducted studies on human subjects to determine the “safe” threshold - defined as the blood lead level when a physical examination could detect symptoms of lead poisoning.

Kehoe’s group dominated the discussion of lead in the medical field to an almost unprecedented extent. His laboratory - named for Kettering and funded by Ethyl, GM, and DuPont - essentially monopolised peer review of lead-related health research, allowing them to reinforce their results and dominate the medical field, including redefining the medical definition of lead poisoning to match the blood lead thresholds set by Kehoe’s lab.

The lead industry owned lead health, and it wasn’t even a secret.

Clair Patterson With A Meteoric Iron Chair

“It is not just a mistake for public health agencies to cooperate and collaborate with industries investigating and deciding whether public health is endangered - it is a direct abrogation of the duties and responsibilities of those public health organizations.”

- Clair Patterson, addressing the U.S. Senate

Modern academia prides itself on the self-correcting nature of science. There’s a lot of things that could be said about this principle in practice - I keep telling my mother (a research quality expert in her field) to write a book on it, now that she’s retired and the university couldn’t do anything about it. But Kehoe’s research wasn’t challenged from within medicine. Or biology, or chemistry. The challenge to Kehoe’s medical Mordor came from the humble discipline of geophysics.

Clair Patterson, a researcher at the California Institute of Technology, set out to answer a relatively simple question, and one nominally unrelated to issues of occupational health and fuel use: how old is the earth? What about the Solar System?

Patterson’s approach was simple: using samples of uranium taken from meteorites, use the ratio of lead to uranium isotopes in the sample to determine the age of the rock (and from this, the cosmic time frame between it being released by supernovae and landing on Earth). The problem was that Patterson’s data kept coming back wrong: there was too much lead in his samples. He had to develop a whole new clean room paradigm to avoid lead contamination - and in this clean room, he found something he wasn’t looking for.

The same contamination - in the air, in the water, even in Patterson’s own hair - that thwarted his study also influenced the studies of pre-industrial environmental lead concentrations. The assertion that “lead exists in nature” which was the foundation of Kehoe’s entire medical and regulatory paradigm was rooted in flawed data. The industrialised world didn’t have a natural baseline level of lead - it exceeded that concentration by over one thousand times.

In 1965, Patterson published his findings. Of course, Kehoe - a leading expert on lead exposure - was called upon for peer review. Kehoe didn’t squash the findings - actually, he supported Patterson’s paper, though not out of respect for his findings, but because he believed they would be of scientific value as an example of just how wrong a researcher could be. He told the journal to publish the paper so that he and his team could “face and demolish” it. (Seriously. I’m not joking about the Bond villain thing.)

Patterson’s work would see most of his research funding withdrawn, and the oil industry would attempt to influence CalTech’s board to get him fired. But the same meticulous procedures that he needed to build his cleanroom were reflected in his research notes and data, and reviewers outside Kehoe’s group of lead experts validated Patterson’s conclusions. New samples were taken from Arctic glaciers and the depths of the ocean, and when protected from contamination like Patterson’s meteorites, they supported him, not Kehoe: lead concentrations increased dramatically with industrialisation.

Patterson and Kehoe would face off before the U.S. Senate in a 1966 hearing. Kehoe was called as the medical expert on lead poisoning, while Patterson spoke for the new conclusions - and denounced Kehoe’s monopoly on lead research and the government’s sometimes-tacit, sometimes-explicit support for his findings.

Afterwards

If this were a morality play, this is where Kehoe’s career would end, but it didn’t. Kehoe retired from academia in 1965, a year and was granted the title of Professor Emeritus of Occupational Medicine by his long-time employer, the University of Cincinnati. He would withdraw from public life in 1979, but not before championing the unproven-but-not-disproven safety of another Midgley-made environmental disaster, Freon.

Patterson’s work shook faith in tetraethyllead, but it took another, ten years for the government to finally regulate it. Pediatrician Herbert Needleman found a link between neurodevelopmental damage in children and elevated lead levels, which was soon linked to air pollution. Despite a lawsuit from the Ethyl Corporation, the U.S. government officially began phasing out the use of leaded gasoline in automobiles in 1976. Ethyl Corporation shifted to international markets, and lobbied many governments in the developing world against banning leaded gasoline.

While the United Nations declared that leaded gasoline was eliminated worldwide in 2011, it remained available for purchase until 2021, when it was officially removed from sale in Algeria, the last country to produce it. The United Nations once again declared that this marked the worldwide elimination of leaded gasoline. Tetraethyllead is still produced in the United States and China for use in aviation fuel.

The Kehoe Rule’s stranglehold on public health discourse was shaken by the erosion of its namesake’s work, but it lingers, especially in the United States. The example set by Kehoe became the scientific shield for much of the scientific malpractice of the mid-20th century, from the proliferation of asbestos to the U.S.’s use of defoliants as chemical weapons in Vietnam. In many ways, it remains active today, as Monsanto (now Bayer) relied on a variation of the Kehoe Rule as their primary defense against lawsuits regarding their Roundup pesticide’s possible status as a carcinogen.

Endings

Perhaps the ironic symbol of Thomas Midgley’s career is his death in 1955. Suffering from polio, Midgley developed a sophisticated system of mechanical mobility aids, only to be killed when the device malfunctioned, making him one of the unlucky few to have invented their own cause of death. He was 55.

Clair Patterson died on December 5, 1995 at age 73. The cause of death for the champion of air pollution regulation was a severe asthma attack.

Robert A. Kehoe died in 1992, shortly after his 99th birthday. The University of Cincinnati’s archives house a collection of his papers, though none I could find had been digitised (at least for public view). In the archive’s introduction, they describe him as a “renowned occupational health expert”.

There is a private university in Flint, Michigan named for Charles F. Kettering. Yes, that Flint.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Environmental Protection Agency has announced more stringent rules governing offshore oil spill response, amid continuing concerns about the effects on public health and wildlife from chemical disasters, including BP’s Deepwater Horizon explosion in 2010.

The federal agency, which announced the update on Monday, had not updated its rule regulating the chemicals used to break up offshore oil slicks since 1994.

Five environmental organizations, an Alaskan tribal leader and a south Louisiana fisher sued the EPA in 2020 to force the agency to update its regulations based on lessons learned from the BP oil spill and the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989. In 2021, US district court judge William Orrick ordered the EPA to update its oil spill response plans.

Thousands of people who rushed into Gulf of Mexico waters to clean up BP’s oil spill have fallen ill, and some have died. A recent Guardian investigation spotlighted the difficult legal fight that cleanup workers who got sick have been experiencing trying to bring medical cases against the oil giant.

More than three decades earlier, those who cleaned up the Exxon Valdez oil tanker spill off the coast of Alaska suffered the same fate. A growing body of research has linked exposure to the dispersants used by BP to break up oil slicks with chronic illnesses, including increased risk of cancer, heart conditions and an increased rate of births of premature and underweight infants.

The updated EPA rule, which takes effect in December, requires dispersants to undergo more stringent toxicity and efficacy testing before they can be approved for use. Dispersants currently approved by the agency must undergo retesting under the new criteria. Products not retested within two years after the rule takes effect or that do not meet the new criteria will be removed from the approved list, according to the updated regulations.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lubricants Market Dynamics, Top Manufacturers Analysis, Trend And Demand, Forecast To 2030

Lubricants Industry Overview

The global lubricants market size was estimated at USD 139.44 billion in 2023 and is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 3.8% from 2024 to 2030.

This is attributed to the growing demand for automotive oils and greases due to the growing trade of vehicles and spare parts. Lubricants are an essential part of rapidly expanding industries. They are used between two relatively moving machinery parts to reduce friction and wear & tear. They can be either petroleum-based or water-based and are essential for proper machinery functioning. Lubricants also decrease operational downtime and eventually increase overall productivity. Lubricants are extensively used in processing industries and automobile parts, especially brakes and engines, which need lubrication for continuous smooth functioning.

Gather more insights about the market drivers, restrains and growth of the Lubricants Market

The increasing imports and exports of piston engine lubricants are contributing to market growth. The product demand is driven by the rising focus of consumers on enhancing vehicle performance coupled with the introduction of innovative & premium product offerings. Future growth will be highly dependent on motor vehicle production and the miles covered by each vehicle. Furthermore, consumers are looking for standard and specialized lubricants for their regular vehicles to ensure the smooth functioning of their vehicles and reduce long-term maintenance costs.