#flooded santa ana river

Photo

Winter Musings 2023

iPhoneXR Hipstamatic Photography

Original Photographers

Photographers On Tumblr

Lowy Lens, Cinematheque Film, No Flash

#hipstamatic#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#flooded santa ana river#flooded river#winter storm#winter#art#capiolumen#iphone#iphonexr#iphotography#lowy lens#cinematheque film#no flash

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

(As I write this, the Tropical Storm Hilary has yet to land its full force into the Southern California region.. but its 24 hours away and coming in..)

Here’s the thing about the hurricane Hilary coming in to give Southern California a huge, and potentially, a much needed bath.. it’s the irony.. (btw..Southern California really needs the water after a horrendous two to three year drought) Southern California has had it’s share of natural disasters.. namely brush fires and earthquakes.

I currently live in the Denver, CO region along the Front Range, but my hometown is Riverside, CA. I’ve also lived in Los Angeles in various communities during my younger days as a starving artist.

Living in SoCal since 1970, I lived through 3 major earthquakes and countless brush fires. Brush fires so bad, at one time in the early to mid 1990s fire seasons, I could see all of those fires (1993-94?) 360° around me in the mountains and foothills. It was a crazy time.

Growing up, I also lived in two states, Florida and Texas. I don’t even remember severe weather back in those days. I don’t even remember hurricane Gladys in 1968 hitting the Florida panhandle where we lived when I was 6 years old. Hell, I barely remember any tornado that came in. Of course today, here in the Denver area, I’m connected 24/7 to all tornado and weather alerts.. and I won’t mention the crazy snow storms and blizzards..

But hurricane Hilary is a conundrum to me. It’s like a cartoon.. it’s there, but it’s two dimensional. I have family and friends that are right now bracing for this potential disaster, what with the possibility of catastrophic flooding and wind damage.

The last event equal to this was around 1937-38. Massive flooding due to run off that the hard SoCal ground can’t absorb, and the ground is still like this today, from the deserts to the sea.. pancake hard. I know the Los Angeles River and the Santa Ana River are the main concourses that will have to take the brunt of this deluge that will be coming. I can only imagine.

The majority of the storm is currently hitting the east from Palm Springs to all points eastward. Arizona and Nevada will surely get a drenching.. and probably within a week, we’ll start to see remnants coming into Colorado.

But something like this has never happened to the southwest U.S. in over 85 years.. or what has been referred to as the 100 year flood event. It’s bound to happen but not as a Tropical Storm.. “Pshhh! This happens to Florida, the Caribbean and the Eastern Seaboard.. not the west coast..!!” SoCal did have a horrendous Pacific storm in the late 1980’s that tore up a good chunk of the L.A. and Orange County beaches.. tore off a pier or two. I do remember that one. Rained for days..

So here I am.. getting ready to watch my old stomping grounds get tested by the storm of the century.. seems unreal, but there it is.. in all it’s wet sloppy glory.

Go easy on them Hilary.. it’s their first time..

..and..

huh?

What?

Southern California really dodged a bullet..?

Oh fuck me..

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Little boy rescued after being swept away in rain-flooded Santa Ana River

A boy was rescued Sunday after being swept away down the Santa Ana River after getting too close to the water, the Orange County Fire Authority said.

from California https://ift.tt/MTxVCKj

0 notes

Photo

The Los Angeles flood of 1938 was one of the largest floods in the history of Los Angeles, Orange, and Riverside Counties in southern California. The flood was caused by two Pacific storms that swept across the Los Angeles Basin in February-March 1938 and generated almost one year's worth of precipitation in just a few days. Between 113–115 people were killed by the flooding. The Los Angeles, San Gabriel, and Santa Ana Rivers burst their banks, inundating much of the coastal plain, the San Fernando and San Gabriel Valleys, and the Inland Empire. Flood control structures spared parts of Los Angeles County from destruction, while Orange and Riverside Counties experienced more damage. (at Du Par's Restaurants & Bakeries) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cj8fwbIppr5/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Bobby Lagsa

Rappler Correspondent

Cagayan de Oro City – Philippine Veterans Investment Development Corporation –Industrial Authority Misamis Oriental (Phividec/PIA-MO) Administrator and Chief Executive Office Jose Gabriel la Viña On February 22, 2021 ordered the closure of all quarry operations along Tagoloan River that is within the land of PHIVIDEC in Tagoloan, Misamis Oriental.

Slapped with closure order are quarry operators Manuel Sukarno Alvarez operating in Lot No. 767, Pls-799 operating in Sitio Bontong, Santa Ana, Tagoloan.

Chique V. Cosin operating in Lot. No 404 and 1202, Pls-799, Sitio Mohon, Santa Ana, Tagoloan.

Nicomedes Achas of ORO NQA enterprises operating in Lot No. 598, 599 and 765, Pls-799, Sitio Bontong, Santa Ana, Tagoloan.

Salvador Fernandez operating in Lot 394,397, 398, 1196, 1195, 1194, 1193 Pls-799 Santa Ana, Tagoloan.

A 5th quarry operator is yet to be named as it is operating outside PIA land but uses its road network and the PIA legal team is still studying its legal remedies.

La Viña, a close ally of President Rodrigo Duterte said that the quarry operations within the PHIVIDEC land started in the 1990 and have since eats up 70 hectares of land of the 3 thousand hectares that PHIVIDEC owned.

PHIVIDEC is an industrial authority that promotes industrial lands and providing tax incentives to investors and operates between the towns of Tagoloan and Villanueva, Misamis Oriental.

La Viña said that based on the mandate of PHIVIDEC under Presidential Decree 538, PIA has the sole right to PIA lands.

La Viña said that the local government unit of Tagoloan have been issuing quarry permits to operators but the same operators are not registered with PIA thus their operations are legal as PIA-MO have not issued any business permits to these operators.

Atty Princess Ayoma, Legal Officer 3 of PIA said that the quarry operation is illegal because there is no permit from PIA for them to operate and only PIA has the sole police power to exercise over its land, “Under PD 538, PHIVIDEC has the sole authority and police power to exercise over its industrial estate,” Ayoma said.

Ayoma added that quarry operators needs to secure an area clearance from the landowner, “Definitely, these quarry operators did not secure an area clearance from PIA making this quarry operations illegal,” Ayoma said.

La Viña added that quarry operators have established their bunkhouses, operations center, equipment and stockpile inside PIA lands without permission.

La Viña also added that environmental degradation due to quarry jeopardizes the safety of the people and locators living inside PIA lands. “If there is flood, the safety of people and locators are in danger, thousands of people will lose their jobs. The locators are rich, they will not be affected, it is the people that will suffer for job losses,” La Viña said.

NO POWER

Tagoloan Mayor Gomer Sabio did not took the Cease and Desist Order by la Viña easily arguing that Phividec has no power over Tagoloan River.

“I don’t have copy of his Cease and Desist Order, and all of these quarry operations have permits,” Sabio said.

Sabio said that since he was elected as mayor of Tagoloan, a first class industrial and port municipality, he ordered closure to at least 10 illegal quarry operations.

The remaining five operators that la Viña ordered closed have quarry permits from the Misamis Oriental Provincial government and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources –Mines and Geoscience Bureau and Environmental Management Bureau.

“These permits went through the process from DENR to Provincial environment and Natural Resources to Municipal environment and Natural Resources,” Sabio said.

Sabio added that on their Local government level, they issued business permit to quarry operators and their trucking services partners.

“Besides, Phividec has no power over the rivers, these quarry operations are providing (aggregates) supplies to the Build, Build, Build program of the national government,” Sabio said.

Sabio however agreed that Phividec have power over the lands where these quarry operators’ stockpiles and motorpool are located. “If the stockpiles and their equipment are located over their land, that they can order the removal but not the power to issue a Cease and Desist,” Sabio said.

Sabio also revealed that Phividec did not reached out to the LGU and neither do they have any plans to meet la Viña and passing the decision to the quarry operators if they will follow the Phividec order.

la Viña said that he will not allow any trucks from quarry operations to pass through Phividec roads.

Sabio for his part said that only the local government unit has the power to stop any quarry operations.

#bobby lagsa#photojournalism#philippines#mindanao#cagayan de oro#river#quarry#boy#environment#pompee la viña#phividec

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

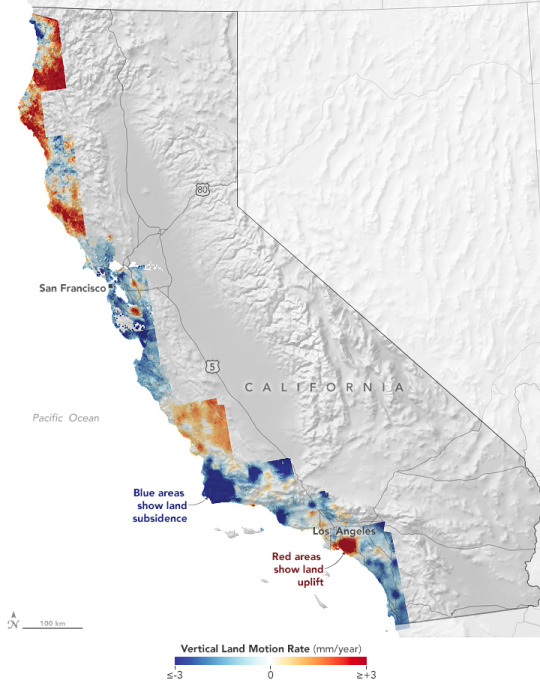

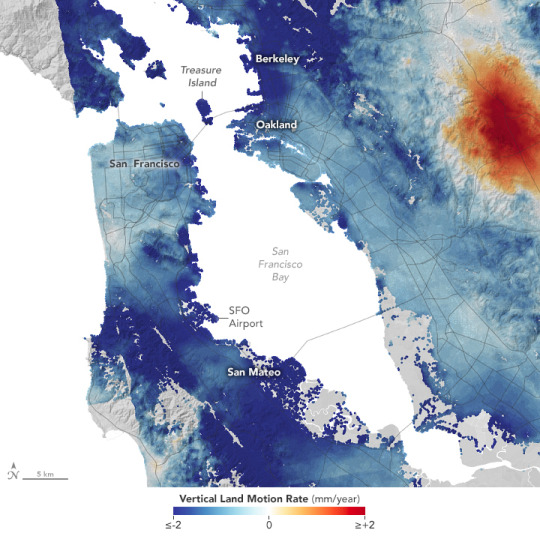

California’s Rising and Sinking Coast Global sea level has been rising at a rate of 0.1 inches (3.3 millimeters) per year in the past three decades. The causes are mostly the thermal expansion of warming ocean water and the addition of fresh water from melting ice sheets and glaciers. But even as the sea takes up more space, the elevation of the land is also changing relative to the sea. What geologists call vertical land motion—or subsidence and uplift—is a key reason why local rates of sea level rise can differ from the global rate. California offers a good example of how much sea level can vary on a local scale. “There is no one-size-fits-all rule that applies for California,” said Em Blackwell, a graduate student at Arizona State University. Blackwell worked recently with Virginia Tech geophysicist Manoochehr Shirzaei to estimate vertical land motion along California’s coast by analyzing radar measurements made by satellites. The research team—which also included Virginia Tech’s Susanna Werth and Geoscience Australia’s Chandrakanta Ojha—found that up to 8 million Californians live in areas where the land is sinking, including large numbers of people around San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego. Land can rise or fall as a consequence of natural and human-caused processes. Key natural processes include tectonics, glacial isostatic adjustment, sediment loading, and soil compaction, explained Shirzaei. Humans can induce vertical land motion by extracting groundwater and through gas and oil production. The map at the top of this page highlights the variability in the rising and falling of land across California’s 1000-mile (1,500-kilometer) coast. Areas shown in blue are subsiding, with darker blue areas sinking faster than lighter blue ones. The areas shown in dark red are rising the fastest. The map was created by comparing thousands of scenes of synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data collected between 2007 and 2011 with more collected between 2014 and 2018. Blackwell and colleagues looked for differences in the data—a processing technique known as interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR). The radar data came from sensors on Japan’s Advanced Land Observing Satellite (ALOS) and Europe’s Sentinel-1A satellite. The researchers also made use of horizontal and vertical velocity data from ground-based receiving stations in the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS). The InSAR data shown in these maps have an average spatial resolution of 80 meters per pixel, more than one thousand times higher than previous maps based only on GNSS data. The reasons why land uplifts or subsides in any given area can be complex. Over long time scales and large scales, tectonic plates can shift the land. For instance, in Northern California the subduction of the small Gorda plate beneath the North American plate at the Mendocino Triple Junction causes the crust to thicken and rise a few millimeters per year. But to the south of Cape Mendocino, the tectonic environment is quite different. Instead of one plate diving beneath another and pushing it upward, the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate grind past each other in a north-south direction, which causes significantly less uplift in central and southern California. Other geologic forces work closer to the surface and over shorter spans of time. In river deltas, bays, valleys, and other areas where sediments pile up, land tends to sink over time from the added weight—a process called sediment loading. It also sinks because particles of sediments get squeezed together and compressed over time, explained Shirzaei, the project lead and a member of NASA’s sea level change science team. In fact, sediment compaction is the main reason that the areas around San Francisco Bay, Monterey Bay, and San Diego Bay have relatively high rates of subsidence. In the detailed map of San Francisco (above), note that the low-lying airport is subsiding. Subsidence is also particularly pronounced on Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay, which has seen subsidence exceeding 10 millimeters per year thanks in part to a landfill on the island. The area of uplift east of San Francisco in the Livermore Valley is likely caused by the underground aquifer refilling and rebounding after a long period of drought. Human activities tend to have more short-term effects on vertical land motion. One example is the zone of strong uplift around Santa Ana, a valley just south of Los Angeles. That is mainly due to a groundwater management system that has replenished aquifers in recent years, a process that causes uplift. The map indicates one bit of positive news for Los Angeles: uplift along parts of the coast makes much of the city and its coastal suburbs less exposed to flooding hazards caused by increased sea level rise than other major coastal cities. This picture of vertical land motion highlights the sea level rise planning and mitigation challenges that communities in many parts of the state face. “The dataset presented here can assist long-term resilience planning that enables coastal communities to choose among a continuum of adaptation strategies to cope with adverse impacts of climate change and sea-level rise,” said Shirzaei. NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using data from Blackwell, Em, et al. (2020) and topographic data from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM). Story by Adam Voiland.

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

For 63-year old U.S. Post Office carrier Peggy Frank, that Friday marked her first day back at work after recovering from a broken ankle. At 3:35 p.m., Frank was pronounced dead after paramedics found her unresponsive in her non-air-conditioned truck. In September, the Los Angeles County coroner’s office confirmed what seemed a forgone conclusion: Frank died of hyperthermia — she overheated.

A few months later, in November, the Woolsey Fire swept through Malibu and parts of the San Fernando Valley. The blaze killed three and forced the evacuation of almost 300,000 people, burning 96,000 acres and destroying 1,643 structures. Then, after heavy rain in areas scarred by the fire, came the mudslides in December and January that killed one person and closed portions of the Pacific Coast Highway.

For most of the population, climate change is too big a thing to grapple with. As the theorist Timothy Morton argued, it’s a “hyperobject” — it is too big, too sprawling in time and space, and too complex to see fully from any single vantage point. It’s numbing. But by narrowing our focus, we can catch more than a glimpse. It may be easier to understand climate change at the regional level, says Katherine Davis Reich, associate director of UCLA’s Center for Climate Science. “We can all appreciate what climate change impacts would be in our backyard and act on that, much more than at the global level.”

Los Angeles, the second-largest city in the United States, is perched precariously on the edge of the Pacific. Not long ago, it was the nation’s frontier; today, its cultural industries produce the globe’s films, music, and television, always hunting for the next new thing. Here, the line between the present and the future has always been thin. As it swelters, burns, erodes, and collapses, that barrier may have been swept away altogether. For L.A., 2018 was not a sign of things to come. It’s a sign of things that have arrived.

That Los Angeles should exist at all is itself a tale of the extraordinary becoming commonplace. An underpopulated backwater until the discovery of oil in 1892, today’s L.A. is a thick smear of civilization over what may not actually be a desert, but what certainly has the mythic feel of one. Precariousness is the resting state of L.A.’s collective unconsciousness.

The city has been grappling with ecological collapse since its beginnings — and not just in films like Chinatown or San Andreas. In 1927, the Los Angeles Times warned of an environmental reckoning: “I was pessimistic enough to imagine that self-confident Los Angeles had forgotten Babylon, Palmyra, Palestine, China and Timgad. What I now saw was our own beloved land. And I saw sand dunes, sage brush, aridity, stately ruins, idle derricks, desolation.”

“By the end of century, a distinctly new regional climate state emerges.” This climate includes a new, fifth season: a super summer.

Even the most dire predictions don’t suggest that Los Angeles will go the way of Timgad — a Roman colony in modern-day Algeria that is now covered by sand. People will still flock here, and even if the city were to collapse, it would happen over a much longer time scale. Still, by 2069, Los Angeles could well be on the way to a new season of misery.

“With the exception of the highest elevations and a narrow swath very near the coast, where the increases are confined to a few days, land locations see 60–90 additional extremely hot days per year by the end of century,” one study concluded. Downtown Los Angeles could experience up to 54 days measuring 95 degrees or higher by 2100, a ninefold jump. By then, temperatures in Riverside could reach over 95 degrees for half the year.

“By the end of century,” the authors of the study found, “a distinctly new regional climate state emerges.” This climate includes a new, fifth season: a super summer, driving people indoors for weeks at a time, stressing the power grid with heavy demand for air conditioning, and wreaking havoc on agriculture and, by extension, the food supply.

Climate change plays favorites, and the heat increase would not be evenly felt. In fact, its unequal distribution could create an “environmental justice story,” explains Davis Reich. “Areas like the San Fernando, the San Gabriel Valley, or the Inland Empire, where the extreme heat burden is already greater, are where the season of extreme heat will occur — parts of the region that are arguably less well-equipped to deal with compared to places like Santa Monica.” There’s a dark irony there, since wealthier people produce more carbon emissions. “The people who have contributed to the problem the least are going to suffer from it earlier and more,” Davis Reich says.

Meanwhile, beaches in Los Angeles will be facing their own threats. Rising sea levels will attack the coast in at least two ways: inundating beaches and eroding cliffs. “Our beaches are compromised. Not just from overall sea level rise, but also coastal storm events,” says Lauren O’Connor Faber, the city’s chief sustainability officer.

In 2017, scientists modeled the effects of sea level rise on 500 kilometers of shoreline in Southern California. A sea level rise of 0.93 to two meters, they predicted, would result in the loss of 31 to 67 percent of beaches in Southern California, including some of its most well-known. A separate USC studyconcluded, “In Malibu, both low and high sea level rise scenarios suggest that long segments of beach will essentially disappear by 2030.”

“Those beaches are the basis for a lot of California’s identity,” said the first study’s lead author, Sean Vitousek, an assistant professor of civil and materials engineering at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Vitousek was part of another research project predicting that because of rising sea levels, sea cliffs in Southern California would erode, on average, up to 120 feet over the next 80 years. By comparison, the rate of cliff erosion in California over the past 80 years maxed out at 1.5 feet. At the end of the century, the model predicted an increase in cliff erosion of “27–185% above historically observed retreat rates.”

Those changes put more than just surfers and beachcombers in peril. In 2060, sea level rise will likely put between 414 and 3,979 homes along the coast in the L.A. region at risk of flooding — up to $3 billion in value. Beach nourishment — artificially adding sand to bulk out the shoreline — is one option but may not be enough. The coast could be armored with sea walls, cliffs shored up, and sea gates constructed. Vitousek says that a shoreline retreat strategy might be needed — but it won’t be easy. “Because there is so much money involved in all of this, people will fight tooth and nail to keep themselves on the coast for as long as possible,” he says.

And as the coastline advances, the forests around Los Angeles have already begun to burn.

In December 2017, a series of 27 wildfires ignited in Southern California, including the Thomas Fire, which burned more than 281,000 acres across Ventura and Santa Barbara counties, resulting in two deaths and the evacuation of more than 200,000 people. Less than a year later, the Woolsey Fire burned 96,949 acres, spreading south from the mountains into Malibu, where it destroyed hundreds of homes and killed three people.

If you think think of 1994’s Northridge earthquake as L.A.’s signature disaster, the coming decades may make you reconsider. Because while climate change may not have much effect on earthquakes, it will lead to more — and more destructive — wildfires. The area burned by Santa Ana fires is predicted to increase by 64 percent by the middle of the century, compared to 1981 to 2000, while non–Santa Ana fires, which occur from June to September and are concentrated inland, will increase by 77 percent. The number of structures destroyed will rise as well — 20 percent for Santa Ana fires and 74 percent for non–Santa Ana fires. Santa Ana fires currently threaten 3,400 structures in an average year, while non–Santa Ana fires put 440 structures at risk per year.

Eventually, all that risk adds up.

“One thing that often gets lost is that wildfires are perfectly natural,” Davis Reich says. “These landscapes were made to burn and need to burn periodically to be healthy. When we build into our wildlands, there is a risk that our buildings will burn. We have to confront that more seriously than we have in the past.”

After fires destroyed a neighborhood in the Bay Area in 2017, local politicians debated the wisdom of rebuilding homes in high-risk areas. There was little appetite for such a move there (or for similar efforts in parts of Southern California), but eventually it may become too expensive to continue rebuilding in high-risk spaces. The Los Angeles Times mapped the 1.1 million buildings in California located in zones at highest risk for fires, showing clusters in the Santa Monica Mountains, the Palos Verde Peninsula, Mission Viejo, and Yorba Linda. Nearly all of Topanga, Paradise, and Malibu were also at risk. Few political leaders want to discuss managed retreat yet — but in 50 years, they may have to.

Climate change is no longer on the horizon. It has arrived.

The masterstroke that allowed Los Angeles to grow may be the one that causes it to retract: Los Angeles depends on imported water, whether from the Owens Valley or farther abroad. As the globe warms, those supplies will dwindle and become harder to manage. Sixty to 70 percent of the water used in Southern California comes from the San Joaquin River and Tulare Lake basins, the Sacramento River basin, Mono Lake, and the Colorado River basin. (The bulk of the remainder is pumped local groundwater.) Of that, 75 percent is drawn from spring snowmelt from the Rockies, the Sierra Nevada, and other mountain ranges.

The Fourth National Climate Assessment, released in November 2018, projected “substantial reductions in snowpack, less snow and more rain, shorter snowfall seasons, earlier runoff, and warmer late-season stream temperatures.” Snowpack reduction in Southern California mountains could reach as high as 50 percent by the end of the century. At the same time, water flow in the Colorado River could be down 35 to 55 percent.

Water demand in 2050 is projected at 1.4 million to 1.7 million acre-feet per year, while supply is projected at 1.4 million acre-feet per year. At best, it’s break even. At worst — well, ask Cape Town.

And those estimates may underrepresent the risk to L.A.’s water supply. A 2015 study concluded that “the mean state of drought in the late 21st century over the Central Plains and Southwest will likely exceed even the most severe megadrought periods of the Medieval era,” causing “an unprecedented fundamental climate shift with respect to the last millennium.”

Another study conducted in 2016 found “a pronounced increase of droughts and aridity in the Southwest during the latter half of the 21st century.” A megadrought — one that would last multiple decades — “could become commonplace.” Droughts of that magnitude were associated with collapse of the Angkor, Anasazi, and Maya civilizations.

“There are two futures in front of us,” says O’Connor Faber, CSO of Los Angeles. “One in which we do not act, do not take leadership. We let the disasters happen. That’s an untenable future. The good news is that’s not at all the future that L.A. accepts.”

It’s not a future that the state of California hopes will come to pass. In 2006, the state enacted a cap-and-trade system to reduce its carbon emissions. A new state law mandates that by 2045, California will rely solely on clean electricity. In recent sessions, state legislators have begun to reshape the laws that govern the state’s housing market, hoping to encourage denser buildings oriented around mass transit, rather than sprawl that forces drivers onto jammed freeways.

For its part, the city of Los Angeles has embarked on an ambitious effort to do what it can. As Mayor Eric Garcetti told Rolling Stone in September, “We’re not waiting for Washington. The cavalry isn’t coming.”

So the city is building up local water supplies and curbing demand, increasing the tree canopy and building out cooler infrastructure to reduce its heat island, spurring the installation of solar power, and armoring its beaches and the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Progress has already been made: Emissions at the port have dropped by double digits, tens of thousands of electric vehicle chargers have been installed, and improvements in public transit are coming.

As she works through the list, Faber O’Connor says she recognizes the magnitude of the task but has reason to hope. “I’m feeling very positive,” she says. For her city, climate change is no longer on the horizon. It has arrived. And like a car speeding down a clear freeway, the city is racing to catch up.

Phroyd

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Took advantage of a nice day. You are looking over the historic Santa Ana River Valley. The largest river in Southern California, it flows for 100 miles from the San Bernardino and San Jacinto Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. For over a century the water has been diverted for agriculture and other human uses. The construction of Prado Dam in 1941, 30 miles upstream, was the largest project to change the nature of the river. Today the lower section is now completely channelized for flood Fairview Park is part, of a string of publicly owned lands from the Santa Ana River mouth along the river to the mesa lands. The proposed Orange Coast River Park would connect these open spaces and provide a corridor for wildlife as well as people on foot or bicycle. #shotoniphone #teamiphone #mobilephotography #iphone13promax #lifesbetterwhenyoumakestuff — view on Instagram https://ift.tt/3n07c0o

0 notes

Link

K-rails, bollards, 4-ton boulders and other beefed-up barriers have been going up around the Santa Ana riverbed in Riverside County this year to halt a recent spike in crashes involving all-terrain vehicles.

Riverside city and county authorities are also intensifying efforts to keep ATVs off of public streets.

Off-road vehicles are illegal to operate anywhere in the city, and motorized vehicles are banned from the basin. But since 2018, Riverside police have responded to 40 crashes involving dirt bikes, quads, side-by-sides and other ATVs, Riverside Police Officer Amanda Beeman said.

She added that 18 of those collisions took place in 2021. Four crashes have sent five people to hospitals and left another three people dead.

“These (off-road) vehicles shouldn’t even be on the road,” Beeman said.

One of those who died was a 20-year-old man riding a dirt bike that didn’t have headlights the evening of Thursday, Jan. 21. It collided with a Subaru Crosstrek that was turning left from Main Street onto Alamo Street.

Most recently, a Corona man was killed Aug. 6, when the 2006 Jeep he was driving rolled down a ravine in La Sierra Hills. A woman and 10-year-old boy were also in the vehicle and suffered critical injuries.

Police and firefighters respond to a crash involving an ATV and a compact SUV in Riverside on Aug. 4, 2021. The two people riding the quad were ejected from the vehicle and hospitalized with serious injuries. The driver of the SUV was also taken to a hospital with minor injuries. (Photo courtesy of the Riverside Police Department)

Hobby becomes hazard

More people may have taken up off-roading recently as a way to overcome the isolation resulting from stay-at-home orders and the closure of most bars and clubs during the pandemic, Beeman said.

“Since COVID, I have seen a dramatic increase in the off-road use of the river bottom and off-road vehicles on the road,” she said.

Many ATVs aren’t equipped with appropriate lighting and other features required to be safely driven on public streets, Beeman said. Some people ride their off-road vehicles recklessly, she added.

“When you run a stop sign or a red light, or you’re speeding up and down a street and someone pulls out in front of you, we’re seeing injuries occurring,” Beeman said. “More prevalently, because these people aren’t wearing helmets. They’re not wearing seatbelts. They’re not obeying the speed limit.”

On Aug. 4, a 30-year-old man who was not wearing a helmet and a 16-year-old boy riding with him were ejected from a Yamaha YFZ. Police said it ran a red light and struck a Honda CRV at the intersection of Columbia Avenue and Orange Street. The ATV riders were seriously hurt and taken to a hospital, along with the 65-year-old driver of the SUV, who suffered what were described as minor injuries.

Beyond city limits

People riding ATVs and dirt bikes on paved streets may be coming and going from the Santa Ana riverbed, Beeman said. It and the adjacent cycling and hiking trail are off-limits to motor vehicles. But that hasn’t stopped the area from becoming a popular destination for off-roading, Riverside Police Lt. Chad Milby said.

It often draws people from beyond the city’s limits.

A 4-wheel drive vehicle sits stuck in silt in the Santa Ana riverbed Thursday, Sept. 2, 2021. The city of Riverside has placed steel bollard posts at a number of entrances into the basin to prevent vehicles from entering, though vehicles are still able to gain access to the basin through areas outside the city. (Photo by Will Lester, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/SCNG)

A bicyclist pedals past steel bollard posts as he prepares to ride along side the Santa Ana riverbed in Riverside Thursday, Sept. 2, 2021. The city has placed the posts at a number of entrances to the river basin to prevent 4-wheeled vehicles from entering. (Photo by Will Lester, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/SCNG)

Riverside police officer Russ Williams prepares to lock a steel bollard post back in place to prevent vehicle access into the Santa Ana River in Riverside Thursday, Sept. 2, 2021. The city has installed the posts along various entry points to the Santa Ana River to prevent 4-wheel vehicles from entering into the basin. (Photo by Will Lester, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/SCNG)

Riverside police officer Russ Williams prepares to remove a steel bollard post blocking access to the Santa Ana River as fellow officer Ryan Railsback looks on in Riverside Thursday, Sept. 2, 2021. The city has installed the posts along various entry points to the Santa Ana River to prevent 4-wheel vehicles from entering into the basin. (Photo by Will Lester, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/SCNG)

Boulders have also been placed to help prevent access by vehicles into the Santa Ana riverbed in Riverside Thursday, Sept.. 2, 2021. (Photo by Will Lester, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/SCNG)

Riverside police officer Russ Williams prepares to remove a steel bollard post blocking access to the Santa Ana River as fellow officer Ryan Railsback looks on in Riverside Thursday, Sept. 2, 2021. The city has installed the posts along various entry points to the Santa Ana River to prevent 4-wheel vehicles from entering into the basin. (Photo by Will Lester, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/SCNG)

Riverside police officer Russ Williams unlocks and removes a steel bollard post blocking access to the Santa Ana River as fellow officer Ryan Railsback looks on in Riverside Thursday, Sept. 2, 2021. The city has installed the posts along various entry points to the Santa Ana River to prevent 4-wheel vehicles from entering into the basin. (Photo by Will Lester, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/SCNG)

Show Caption

of

Expand

Police and local officials have repeatedly received complaints from nearby residents over the years about raucous gatherings and off-roaders speeding through the riverbed, Riverside City Councilwoman Erin Edwards said. Motorists careening through the area pose a hazard to those walking or cycling along trails, and endanger wildlife on nearby nature preserves. In addition, backfire and heat from exhausts could potentially spark a fire.

“We need to keep this place safe for everyone,” Edwards said. “Especially given the past year or so, as a place for people to get out and enjoy nature.”

Milby recalled hundreds of people with quads, side-by-sides and even RVs at an illegal party in the riverbed held beneath the 60 Freeway, near Market Street, during the last weekend of February. A fight at the gathering led to the fatal stabbing of a 19-year-old.

“It’s dangerous,” Beeman said. “It’s dark. People can get lost. People can get hurt, and then it takes us a long time to locate those people and get them help.”

Officers and park rangers have always maintained a regular presence in the area to deter off-roading, Milby said. But that hasn’t stopped people from cutting the locks off of gates or plowing through hollow bollards so they can bring their toys onto paths built for pedestrians and cyclists.

“We were always repairing and replacing barriers before,” Riverside Parks, Recreation and Community Services interim director Randy McDaniel said. “It was like a game of Whac-A-Mole.”

More barriers, patrols

In response to the escalating number of crashes this year, officers surveyed the 11-mile stretch of the Santa Ana River that passes through the city, Milby said. They charted the access points most frequently used by off-roaders.

Police brought their findings to city officials and county agencies that manage portions of the riverbed. Together, they came up with a plan.

City Parks and Recreation staff have already placed several 3- to 4-ton boulders and reinforced bollards at Fairmount Park, Ryan Bonamino Park and the Martha Mclean – Anza Narrows Park, McDaniel said.

The push to secure the riverbed extends beyond the city limits. County Flood Control workers have already installed about five times as many boulders as city parks and recreation crews have, McDaniel said.

And Riverside County Supervisor Karen Spiegel is currently leading an effort that aims to map out all the access points along the remainder of the riverbed running through her district by the end of the year, County Parks and Recreations Assistant Director Erin Gettis said.

But barriers alone won’t be enough to solve the problem. Bikers and hikers still need to be able to get onto the Santa Ana River Trail, which means dirt bikes and slim ATVs may still be able to pass through, McDaniel said.

So police, deputies and park rangers have stepped up patrols of the area, Milby said. Their focus is on prevention and education, because it’s simply too risky to go after someone riding a quad with its exhaust blaring at nearly full throttle along the Santa Ana Riverbed, he and Beeman said.

“It’s really the last place you want to get into a pursuit,” Milby said. “The terrain isn’t solid. And you’ve got members of the homeless population living down there, bikers and joggers that you don’t want to see injured in a collision.”

Collaborative efforts to curb the use of off-road vehicles appears to be yielding early results in the city of Riverside. Edwards said the number of complaints from residents near the riverbed have noticeably decreased since improved barriers started going up. And police patrolling the area aren’t spotting as many off-roaders in the riverbed as they had been earlier this year, Milby said.

Beeman, an off-roading enthusiast herself, urged people to enjoy their toys in places where they won’t affect the safety and well-being of others.

“We have El Mirage Dry Lake, Glamis, the (Bureau of Land Management) area at Dumont Dunes, Pismo if you’re into the beach thing, you have all these places,” Beeman said. “Really where we are at in Riverside is pretty centrally located to any of these places. You can get to them within a couple hours drive, maybe even an hour and a half and it’s perfectly legal and appropriate.”

Related Articles

Authorities seek hit-and-run driver who injured teen in Eastvale

3 men charged with staging freeway accidents for insurance money in Southern California

Valle Vista Library closed after SUV smashes into building

Driver sought after fatal hit-and-run in Rancho Cucamonga

Driver dies in Jurupa Valley after striking two traffic signal poles

-on September 05, 2021 at 10:34AM by Eric Licas

0 notes

Text

What Dry Winter Weather Can Tell Us

Good morning.

This week, over a quarter of a million people were without power as powerful Santa Ana winds roared through parts of Central and Southern California. The winds were possibly the strongest that the state has seen in 20 years.

Coming off the worst wildfire season in history and in the midst of a dry winter, parts of the Santa Cruz mountains where the CZU Lightning Complex Fire burned over the summer reignited and over a hundred residents were evacuated.

The powerful winds also forced a two-day closure of the Disneyland vaccination site in Orange County and damaged roads and buildings at Yosemite National Park.

A warming climate has caused wildfire season, which typically peaks in late summer, to become a year-round affair in recent years. Wildfires in January just may be the new normal. Here’s what the unusual weather means and what it might portend for the coming months.

This season has been unusually dry. Scientists at U.C. San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography looked at how much precipitation has fallen and how much is likely to fall in the coming months. At the beginning of January, they found that the odds of California reaching normal precipitation this year were only about 20 percent.

“If we miss the window of December or January, it can really set us back,” said F. Martin Ralph, director of the university’s Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes.

As Dr. Ralph explained, Western states get a chunk of their rain for the year in just a few big storms. Those storms, called atmospheric rivers, carry huge amounts of water from the ocean into inland areas.

The size and frequency of atmospheric rivers make the difference between what will be a normal season or one filled with catastrophic drought or flooding.

“The top storms, how they vary from year to year largely determines whether or not we’re in drought or flood,” Dr. Ralph said.

Right now, we are in need of one of these large storms.

Dr. Ralph said that there could be substantial atmospheric river activity in the coming days and weeks, especially for the northern parts of the state.

Climate change is making extreme weather patterns even more extreme. California has a climate characterized by alternating extremes — drought and floods. And it is already one of the most flood-prone states in the country in spite of also being one of the driest.

Climate models for the years ahead show that the number of dry days will increase but also, the top wettest days each year will become even wetter.

“The wettest of wet days. Well, those are the days of great floods,” Dr. Ralph said.

And while heavy rains during a drought are welcome, we should be careful what we wish for. Floods brought on by atmospheric rivers can be devastating. Dr. Ralph found that in a 40-year period, 84 percent of all flood damage in the Western U.S. came from atmospheric river events, amounting to billions of dollars in damage.

As each week passes without the arrival of major storms, the risk for wildfires increase. “If it ends up being we don’t get any rain in March or April in Southern California that’s a serious problem,” Dr. Ralph said.

Another thing that can affect the outlook for wildfires this year is how spread out the storms are — if they are distributed across a long rainy season or concentrated in just a few closely timed events.

Less rain makes for increased fire risk, but if the rainy periods fall closer to the start of wildfire season, that could be good.

“If we get even a bit less than normal rain, but there’s sort of a wet period later in the spring, it can help suppress the wildfire risk farther into the summer than normal,” Dr. Ralph said.

But right now, there’s a more immediate need for a good soaking.

“Every week that goes by, if we don’t get rain and snow, it’ll be harder and harder to catch up,” he said.

(This article is part of the California Today newsletter. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox.)

Here’s what else to know today

Imagine having a dance party with friends, hugging a relative or enjoying a meal in a restaurant again. It could, experts say, help you get out of a funk.

My colleague Tariro Mzezewa wrote about how imagining a better future helps humans cope with difficult times.

Jordan Firstman, a television writer who has found some celebrity this year doing impersonations on Instagram, is fantasizing about a day that kicks off with “a 20-person breakfast at a restaurant, indoors,” followed by an orgy, dinner, live theater, a warehouse party and clubbing “until 6 a.m.,” he said. “Then we’ll go see ‘Wicked’ at 8 a.m. because we didn’t get enough theater the night before. We want more theater.”

What’s your fantasy for when the pandemic is over, whenever that day might be?

[Read the full article here.]

California Today goes live at 6:30 a.m. Pacific time weekdays. Tell us what you want to see: [email protected]. Were you forwarded this email? Sign up for California Today here and read every edition online here.

Jill Cowan grew up in Orange County, graduated from U.C. Berkeley and has reported all over the state, including the Bay Area, Bakersfield and Los Angeles — but she always wants to see more. Follow along here or on Twitter.

California Today is edited by Julie Bloom, who grew up in Los Angeles and graduated from U.C. Berkeley.

Multiple Service Listing for Business Owners | Tools to Grow Your Local Business

www.MultipleServiceListing.com

from Multiple Service Listing https://ift.tt/3sHmkRw

0 notes

Text

Cagayan guv thanks PRRD for ‘giving hope’ during visit

#PHnews: Cagayan guv thanks PRRD for ‘giving hope’ during visit

MANILA – Cagayan Governor Manuel Mamba has thanked President Rodrigo R. Duterte for his visit and pledge of support to the flood-hit province.

During the Laging Handa briefing on Monday, Mamba said Duterte knows many of Cagayan’s problems and challenges -- both new and recurring -- noting that discussions are already ongoing on how to fix these issues.

“There were suggestions and there were moves undertaken na nagbibigay sa amin ng pag-asa na sa lalong madaling panahon ay makakapag-plano at siguro at magi-start na rin ito (that are giving us hope and resulted in immediate planning so that maybe, we can start solving these issues),” Mamba said.

Some of Duterte’s actions, he said, include ordering an investigation on the alleged late release of water from Magat Dam that worsened flooding in both the provinces of Cagayan and Isabela after the onslaught of Typhoon Ulysses.

He said Duterte will also look into policies for regulating the release of water from dams, illegal logging in Cagayan, and the immediate dredging—removing sediments and debris from the bottom of a body of water—the entire length of Cagayan River.

“Ang laking tulong po at laking pag-asa (This is a big help and gives a lot of hope)—we see hope after how many decades na hindi po napansin ito (of these being neglected),” Mamba said.

Duterte’s visit on Sunday, he said, was the President’s fifth visit to Cagayan during his term.

“Palaging nandito po siya basta meron (He always visits after) major calamities. This is his fifth time and all of these, may problema po yung mga pinuntahan niya dito (he visits areas that have problems),” Mamba said.

Duterte’s first two visits to Cagayan as President, he said, were during the onslaught of super typhoon “Lawin” (Haima) in 2016 and typhoon “Ompong (Mangkhut) in 2018.”

These were followed by two visits to Santa Ana, Cagayan in 2018 for the destruction of over a hundred contraband luxury cars and motorbikes with a total worth of about PHP300 million.

On Sunday, Duterte visited Cagayan and met with his Cabinet and local officials in Tuguegarao City to discuss the rescue and relief efforts for those affected by flooding and the rebuilding of the province.

On Saturday, residents of parts of Cagayan and Isabela pleaded for help after being blindsided with flooding said to be the worst in the past 40 years. (PNA)

***

References:

* Philippine News Agency. "Cagayan guv thanks PRRD for ‘giving hope’ during visit." Philippine News Agency. https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1121974 (accessed November 16, 2020 at 11:56PM UTC+14).

* Philippine News Agency. "Cagayan guv thanks PRRD for ‘giving hope’ during visit." Archive Today. https://archive.ph/?run=1&url=https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1121974 (archived).

0 notes

Text

DeJarnette Sanitarium, March 2017

When we trudge from green hatchback, it is down a grassy hill, speakless, no beat but the wind to bring us to our knees beneath brick. We don’t know why we are here. All of Shenandoah recedes from sanitarium, ivy overgrown, something unearthable in the fieldlands. Ghosts standing in the shade of microgreens wave us over.

We are praying or pleading or something and silent, hushed unsure, staircases snaking up to Staunton’s most boarded-in, Anasazi of their own, looking for a crack to pry, a cry in the glass to creep through. To come to.

A window delivers us to a tiled floor— so many envelopes, so many letters— the only place the light enters. Our thirsting lungs call out for greenhouse air; unsure if we haunt or host. We feel our way through basement bathroom. Decomposition gases flood the panes; I stop past the shower. Try to picture the steam. I do not know whether the water will hold back the angels or the dead.

I can only picture the nakedness. Something wrong. Something crawls from the corner of a mirror— dusk, dust. Something like oracle or occult—holy and raw at once. A door left ajar lets us through.

Anasazi means ancient outsiders. They lived in Colorado before I moved from Virginia but remain recorded in glyphs, cliff-side, like the ones DeJarnette patients jumped from. These, the hands that painted, abandoned open pages, left their souls in the grass here, psychorealized, that sat in the front yard once watched long enough to be allowed outside for lunch— fistful to mouthful, they watch the Blue Ridge bend and remain, a different kind of prehistoric. Nobody kept records on eugenics, so we are forced to anthropologize, make our way through the dim.

What a privilege to shuffle along marble, to clumsy up staircases, snake toward stars, to wander in the dark. In woodchipped walls, heartbeats echo as sirens. If born forty years before I was, I might’ve been one among many, sterilized, forced to find ways to survive the light. Things they don’t teach. I press an arched window, think of the eyes that must’ve stared through— Staunton’s most boarded in, shapes of opal, shades of pool, mud. I smell latex and bleach, heavy on gritted palms.

The weed pulp outside smells of ghost breath. The floor, of shadow, the bathroom, of irony unsent. Letters opened but never delivered. There were children here, their bodies are outside, along the back fence. Like subterranean succulents, treated with chlorine. Hands corroded tender. I wonder what happened. Ferns holding tiny craters in their bellies baptize away the rot. My trespassed transgression now nothing like what they did.

Out front, grass flattens under where ambulances once treaded, still fertile from spit and mouth foam of pre-patient mourn, rabid irises leaking down and down and down. The stairs work both ways. Flytrap: I can hear them scream. Nerves are synthesized here in handfuls of shrub and oak. Humid clings mist-like to moss out front. They can no longer see it: the portico a duct, nozzeling off-dreams and wrong bodies through. The Anasazi were surrealists, too— watch what they drew from ash.

Watch the Pueblo dunes. Watch the sun rise and pink up the clouds. Predictions come from people asylumed under mortar, mansioned farmhouse kept close in to nowhere, porthole for sanitation— lobotomy, scrubbrush.

Ivy dwindles as fragmented memory. We snake up the front stair, unscrew doorknob like we would loosen a bulb. Every light is already out. Only a few of the entryways open. DeJarnette remains for us anthropologists, haunt or host, hushed— its doors and windows clasp and come undone again, come apart and lock again. Dimmed footprints reactive as carbon whistle under rubber soles. We come to.

Katie Hogan is a twenty year old emerging poet from Richmond, Virginia, writing and living in Denver, Colorado. Her work is forthcoming in The Chiron Review and Ember Chasm Review, and she is currently pursuing an undergraduate degree in creative writing from the University of Denver. Twitter: @katieshogan Insta: @katiehogan16

Madison Zehmer is a poet and wannabe historian from North Carolina. She has published and forthcoming work in the Santa Ana River Review, Gone Lawn, LandLocked, and more. She is the editor in chief of Mineral Lit Mag, and her chapbook will be released by Kelsay Books in 2021. Twitter: @madisonzehmer Insta: @maddiezehmer and @mirywrites

0 notes

Link

The Army Corps of Engineers has been taking soil samples at the refuge in preparation to build the wall.

We have seen information leak out that a wall would cut the refuge down the middle, leaving the visitor’s center on one side and the refuge on the other. It appears that the wall would likely be built outside of the flood plain. Practically speaking, this means that when the river floods, which is does every spring, the flood waters would come up to the wall, leaving wildlife trapped.

The Santa Ana NWR is known worldwide as a birding destination. The refuge sits at a critical place geographically—many songbirds that migrate north from Central and South America go no further north than the refuge, and thus this is a prime place to see birds that don’t exist anywhere else in the United States.

Two endangered cat species still prowl the thick forests of this small refuge: the ocelot and jaguarondi.

If the “wall” consists of a mixture of levees and an actual fence, then this habitat would be changed forever. Levees block water flow and by definition alter the landscape. A fence would reduce the size of the habitat, particularly for land-based animals, who can’t fly over a barrier.

#national wildlife refuge#border wall#texas#mexico#nature#animals#environment#santa ana nwr#conservation#birdwatching#outdoors#parks#public lands#donald trump#politics#USA#republicans#immigration

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charles Wetzel saw a strange creature on the night of November 8th, 1958. He was driving home on North Main Street and came across where it crosses the Santa Ana River only to find it flooded. Wetzel claimed “It had a round, scarecrowish head like something out of Halloween. It wasn't human. It had longer arms than anything I'd ever seen. When it saw me in the car it reached all the way back to the windshield and began clawing me. It didn’t have any ears. The face was all round. The eyes were shining like something fluorescent, and it had a protruberant mouth.” He also described it as having skin like scales.

After running over the monster with his car, he quickly sped to the Riverside, California, police station where officers took a look at his vehicle. They noted claw marks on the hood and windshield of the car but the bloodhounds that searched it found nothing unusual. At least one other person claimed to have a run in with the Riverside Bridge Monster.

700 notes

·

View notes

Photo

IN THE SUNSHINE OF NEGLECT

Another suggestion from my photography professor, In the Sunshine of Neglect is an exhibition highlighting the damaged and neglected nature of the Inland Empire in Southern California. The Empire is more desert terrain than the rest of So Cal, and has been ravaged by wildfires, arid conditions, and the destruction by human inhabitants. The exhibition was featured at the UCR ARTS California Museum of Photography and the Riverside Art Museum, and highlights several famous photographers based out the Inland. Each photographer captured the locales through their own personal lens, portraying fun, destruction, beauty, or desolation as a reflection of their experience there.

The overall theme of the series is a narrative of a place touched by a bustling civilization, and creates a portraiture of a region that is not famously known like LA. Unlike the glittering portrayal of the City of Angels, this neighboring region shows the grittier side of southern California.

Although I was unable to experience the exhibit firsthand, it was fascinating to look at the photos featured via the internet. My sister lived in Redlands for a few years and I often visited her there, so I have my own views on the Inland Empire and its personality. For me, the area had many ‘bad parts’ of town and ones ravaged by human inhabitants. However, there were a lot of cool people there as well as beautiful locations, it just depends on the lens you look through to see them.

0 notes

Link

Construction of a border wall will bisect the geographic range of 1,506 native animals and plants, including 62 species that are listed as critically endangered.

In periods of torrential downpour, the barriers will act as dams during rainy season flash floods.

The border wall could disconnect a third of 346 native wildlife species from 50 percent or more of their range that lies south of the border. Border fencing disrupts seasonal migration, affecting access to water and birthing sites for Peninsular bighorn sheep that roam between California and Mexico.

The river channel shifts course from time to time and floods in the spring. To build a wall north of the river would, in effect, cede control of those lands to Mexico and isolate property and homes owned by U.S. citizens on the Mexican side of the wall.

After ferocious objections, Homeland Security shelved plans to build the wall through the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge in Alamo, Texas, where more than 400 species of birds, banded armadillos, and endangered wildcats live.

Construction of the border wall does not have to meet the requirements of more than 30 of the most sweeping and effective federal environmental laws, such as the Endangered Species Act, National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Air Act, and the Clean Water Act.

0 notes