#folklore is mainly a national album with taylor writing and singing.....

Text

.

#i swear i'm not being a pretentious asshole about it i genuinely enjoy it#but it's extremely funny to me today to see all these swifties listen to the national for the first time for the most part#and the resounding thought is oh! it's like folklore!#and i just heheheheheheheheheh i laugh! i chuckle!#cuz it's like..... everyone KNOWS that folklore is a lot of taylor just writing to instrumentals aaron already made and sent her#and she had little to do with the melody of half the album at least#but i don't think people actually reckoned with that information irl before now like folklore is yes a new direction for taylor#but it's par for the course for the national! they're QUITE LITERALLY reject tracks!!#i don't mean this to demean folklore nor to be reductive towards taylor i'm being totally serious i love watching#swifties slowly come to the realization and connect the dots like#oh...... this is the sound of the national.... THEY sound like that#folklore is mainly a national album with taylor writing and singing.....#and i'm like DING DING DING DING AND THATS WHY IT FUCKS SO SEVERELY#SAD BOY SUPREME MEETS SAD GIRL SUPREME AND THEIR ALBUM OBVIOUSLY IS INCREDIBLE#i try not to like indie-splain my pretentious indie music to the pop girlies or the kiddos so im just really thrilled that#taylor introduced a new group of people to the sound of the national but through slow drip and wrapped in taylorisms#and that they're getting a new audience of fans who aren't 40 year olds#cuz they're excellent but they're debilitatingly sad so you really do need to slowly wade in. you can't just dive into Boxer#you'll suffer so severely#i'm so happy for them and i'm happy for everyone discovering them and i hope you enjoy middle aged existential gloom!!#its a good time!!!!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

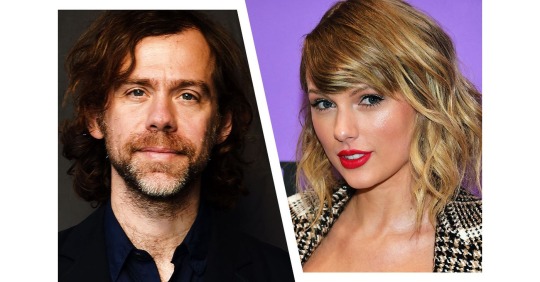

The Story Behind Every Song on folklore - According to Aaron Dessner

By: Brady Gerber for Vulture

Date: July 27th 2020

The National multi-instrumentalist spoke to Vulture over the phone from upstate New York a few hours after the surprise release of Swift’s eighth studio album. (“A pretty wild ride,” he admits, sounding tired yet happy.) He was clear that he can’t speak on behalf of Swift’s lyrics, much like he can’t for The National frontman Matt Berninger’s either, or the thinking behind Jack Antonoff’s songs. (Here’s a cheat sheet: Jack’s songs soar, Aaron’s glide.) But Dessner was game to speak to his specific contributions, influences, and own interpretations of each song on folklore, a record you can sum up by two words that came up often during our conversation: nostalgic and wry.

“the 1″

“the 1” and “hoax,” the first song and the last song, were the last songs we did. The album was sort of finished before that. We thought it was complete, but Taylor then went back into the folder of ideas that I had shared. I think in a way, she didn’t realize she was writing for this album or a future something. She wrote “the 1,” and then she wrote “hoax” a couple of hours later and sent them in the middle of the night. When I woke up in the morning, I wrote her before she woke up in LA and said, “These have to be on the record.” She woke up and said, “I agree” [laughs] These are the bookends, you know?

It’s clear that “the 1” is not written from her perspective. It’s written from another friend’s perspective. There’s an emotional wryness and rawness, while also to this kind of wink in her eyes. There’s a little bit of her sense of humor in there, in addition to this kind of sadness that exists both underneath and on the surface. I enjoy that about her writing.

The song began from the voice memo she sent me, and then I worked on the music some and we tracked her vocals, and then my brother added orchestration. There are a few other little bits, but basically that was one of the very last things we did.

“cardigan“

That’s the first song we wrote [in early May]. After Taylor asked if I would be interested in writing with her remotely and working on songs, I said, “Are you interested in a certain kind of sound?” She said, “I’m just interested in what you do and what you’re up to. Just send anything, literally anything, it could be the weirdest thing you’ve ever done,” so I sent a folder of stuff I had done that I was really excited about recently. “cardigan” was one of those sketches; it was originally called “Maple.” It was basically exactly what it is on the record, except we added orchestration later that my brother wrote.

I sent [the file] at 9 p.m., and around 2 a.m. or something, there was “cardigan,” fully written. That’s when I realized something crazy was happening. She just dialed directly into the heart of the music and wrote an incredible song and fully conceived of it and then kept going. It harkens back to lessons learned, or experiences in your youth, in a really beautiful way and this sense of longing and sadness, but ultimately, it’s cathartic. I thought it was a perfect match for the music, and how her voice feels. It was kind of a guide. It had these lower register parts, and I think we both realized that this was a bit of a lightning rod for a lot of the rest of the record.

The National’s Influence On Swift

She said that she’s a fan of the emotion that’s conveyed in our music. She doesn’t often get to work with music that is so raw and emotional, or melodic and emotional, at the same time. When I sent her the folder, that was one of the main feelings. She said, “What the fuck? How do you just have that?” [laughs] I was humbled and honored because she just said, “It’s a gift, and I want to write to all of this.” She didn’t write to all of it, but a lot of it, and relatively quickly.

She is a fan of the band, and she’s a fan of Big Red Machine. She’s well aware of the sentiment of it and what I do, but she didn’t ask for a certain kind of thing. I know that the film [I Am Easy To Find] has really affected her, and she’s very much in love with that film and the record. Maybe it’s subconsciously been an influence.

“the last great american dynasty”

I wrote that after we’d been working for a while. It was an attempt to write something attractive, more uptempo and kind of pushing. I also was interested in this almost In Rainbows-style latticework of electric guitars. They come in and sort of pull you along, kind of reminiscent of Big Red Machine. It was very much in this sound world that I’ve been playing around with, and she immediately clicked with that. Initially I was imagining these dreamlike distant electric guitars and electronics but with an element of folk. There’s a lot going on in that sense. I sent it before I went on a run, and when I got back from the run, that song was there [laughs].

She told me the story behind it, which sort of recounts the narrative of Rebekah Harkness, whom people actually called Betty. She was married to the heir of Standard Oil fortune, married into the Harkness family, and they bought this house in Rhode Island up on a cliff. It’s kind of the story of this woman and the outrageous parties she threw. She was infamous for not fitting in, entirely, in society; that story, at the end, becomes personal. Eventually, Taylor bought that house. I think that is symptomatic of folklore, this type of narrative song. We didn’t do very much to that either.

“exile” (ft. Bon Iver)

Taylor and William Bowery, the singer-songwriter, wrote that song initially together and sent it to me as a sort of a rough demo where Taylor was singing both the male and female parts. It’s supposed to be a dialogue between two lovers. I interpreted that and built the song, played the piano, and built around that template. We recorded Taylor’s vocals with her singing her parts but also the male parts.

We talked a lot about who she thought would be perfect to sing, and we kept coming back to Justin [Vernon]. Obviously, he’s a dear friend of mine and collaborator. I said, “Well, if he’s inspired by the song, he’ll do it, and if not, he won’t.” I sent it to him and said, “No pressure at all, literally no pressure, but how do you feel about this?” He said, “Wow.” He wrote some parts into it also, and we went back and forth a little bit, but it felt like an incredibly natural and safe collaboration between friends. It didn’t feel like getting a guest star or whatever. It was just like, well, we’re working on something, and obviously he’s crazy talented, but it just felt right. I think they both put so much raw emotion into it. It’s like a surface bubbling. It’s believable, you know? You believe that they’re having this intense dialogue.

With other people I had to be secretive, but with Justin, because he was going to sing, I actually did send him a version of the song with her vocals and told him what I was up to. He was like, “Whoa! Awesome!” But he’s been involved in so many big collaborative things that he wasn’t interested in it from that point of view. It’s more because he loved the song and he thought he could do something with it that would add something.

“my tears ricochet”

This is one of my absolute favorite songs on the record. I think it’s a brilliant composition, and Taylor’s words, the way her voice sounds and how this song feels, are, to me, one of the critical pieces. It’s lodged in my brain. That’s also very important to Taylor and Jack. It’s like a beacon for this record.

“mirrorball”

“mirrorball” is, to me, a hazy sort of beautiful. It almost reminds me of ‘90s-era Cardigans, or something like Mazzy Star. It has this kind of glow and haze. It feels really good before “seven,” which becomes very wistful and nostalgic. There are just such iconic images in the lyrics [“Spinning in my highest heels”], which aren’t coming to me at the moment because my brain is not working [laughs].

How Jack Antonoff’s Folklore Songs Differ From Dessner’s

I think we have different styles, and we weren’t making them together or in the same room. We both could probably come closer together in a sense that weirdly works. It’s like an archipelago, and each song is an island, but it’s all related. Taylor obviously binds it all together. And I think Jack, if he was working with orchestrations, there’s an emotional quality to his songs that’s clearly in the same world as mine.

We actually didn’t have a moodboard for the album at all. I don’t think that way. I don’t really know if she does either. I don’t think Jack... well, Jack might, but when I say the Cardigans or Mazzy Star, those aren’t Jack’s words about “mirrorball,” it’s just what calls to mind for me. Mainly she talked about emotion and to lean into it, the nostalgia and wistfulness, and the kind of raw, meditative emotion that I often kind of inhabit that I think felt very much where her heart was. We didn’t shy away from that.

“seven”

This is the second song we wrote. It’s kind of looking back at childhood and those childhood feelings, recounting memories and memorializing them. It’s this beautiful folk song. It has one of the most important lines on the record: “And just like a folk song, our love will be passed on.” That’s what this album is doing. It’s passing down. It’s memorializing love, childhood, and memories. It’s a folkloric way of processing.

“august”

This is maybe the closest thing to a pop song. It gets loud. It has this shimmering summer haze to it. It’s kind of like coming out of “seven” where you have this image of her in the swing and she’s seven years old, and then in “august” I think it feels like fast-forwarding to now. That’s an interesting contrast. I think it’s just a breezy, sort of intoxicating feeling.

“this is me trying”

“this is me trying,” to me, relates to the entire album. Maybe I’m reading into it too much from my own perspective, but [I think of] the whole album as an exercise and working through these stories, whether personal or old through someone else’s perspective. It’s connecting a lot of things. But I love the feeling in it and the production that Jack did. It has this lazy swagger.

“illicit affairs”

This feels like one of the real folk songs on the record, a sharp-witted narrative folk song. It just shows her versatility and her power as a songwriter, the sharpness of her writing. It’s a great song.

“invisible string”

That was another one where it was music that I’d been playing for a couple of months and sort of humming along to her. It felt like one of the songs that pulls you along. Just playing it on one guitar, it has this emotional locomotion in it, a meditative finger-picking pattern that I really gravitate to. It’s played on this rubber bridge that my friend put on [the guitar] and it deadens the strings so that it sounds old. The core of it sounds like a folk song.

It’s also kind of a sneaky pop song, because of the beat that comes in. She knew that there was something coming because she said, “You know, I love this and I’m hearing something already.” And then she said, “This will change the story,” this beautiful and direct kind of recounting of a relationship in its origin.

“mad woman”

That might be the most scathing song on folklore. It has a darkness that I think is cathartic, sort of witch-hunting and gaslighting and maybe bullying. Sometimes you become the person people try to pin you into a corner to be, which is not really fair. But again, don’t quote me on that [laughs], I just have my own interpretation. It’s one of the biggest releases on the album to me. It has this very sharp tone to it, but sort of in gothic folklore. It’s this record’s goth song.

“epiphany”

For “epiphany,” she did have this idea of a beautiful drone, or a very cinematic sort of widescreen song, where it’s not a lot of accents but more like a sea to bathe in. A stillness, in a sense. I first made this crazy drone which starts the song, and it’s there the whole time. It’s lots of different instruments played and then slowed down and reversed. It created this giant stack of harmony, which is so giant that it was kind of hard to manage, sonically, but it was very beautiful to get lost in. And then I played the piano to it, and it almost felt classical or something, those suspended chords.

I think she just heard it, and instantly, this song came to her, which is really an important one. It’s partially the story of her grandfather, who was a soldier, and partially then a story about a nurse in modern times. I don’t know if this is how she did it, but to me, it’s like a nurse, doctor, or medical professional, where med school doesn’t fully prepare you for seeing someone pass away or just the difficult emotional things that you’ll encounter in your job. In the past, heroes were just soldiers. Now they’re also medical professionals. To me, that’s the underlying mission of the song. There are some things that you see that are hard to talk about. You can’t talk about it. You just bear witness to them. But there’s something else incredibly soothing and comforting about this song. To me, it’s this Icelandic kind of feel, almost classical. My brother did really beautiful orchestration of it.

“betty”

This one Taylor and William wrote, and then both Jack and I worked on it. We all kind of passed it around. This is the one where Taylor wanted a reference. She wanted it to have an early Bob Dylan, sort of a Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan feel. We pushed it a little more towards John Wesley Harding, since it has some drums. It’s this epic narrative folk song where it tells us a long story and connects back to “cardigan.” It starts to connect dots and I think it’s a beautifully written folk song.

Is ‘betty” queer canon?

I can’t speak to what it’s about. I have my own ideas. I also know where Taylor’s heart is, and I think that’s great anytime a song takes on greater meaning for anyone.

Is William Bowery secretly Joe Alwyn?

I don’t know. We’re close, but she won’t tell me that. I think it’s actually someone else, but it’s good to have some mysteries.

“peace”

I wrote this, and Justin provided the pulse. We trade ideas all the time and he made a folder, and there was a pulse in there that I wrote these basslines to. In the other parts of the composition, I did it to Justin’s pulse. Taylor heard this sketch and she wrote the song. It reminds me of Joni Mitchell, in a way - there’s this really powerful and emotional love song, even the impressionistic, almost jazz-like bridge, and she weaves it perfectly together. This is one of my favorites, for sure. But the truth is that the music, that way of playing with harmonized basslines, is something that probably comes a little bit from me being inspired by how Justin does that sometimes. There’s probably a connection there. We didn’t talk too much about it [laughs].

“hoax”

This is a big departure. I think she said to me, “Don’t try to give it any other space other than what feels natural to you.” If you leave me in a room with a piano, I might play something like this. I take a lot of comfort in this. I think I imagined her playing this and singing it. After writing all these songs, this one felt the most emotional and, in a way, the rawest. It is one of my favorites. There’s sadness, but it’s a kind of hopeful sadness. It’s a recognition that you take on the burden of your partners, your loved ones, and their ups and downs. That’s both “peace” and “hoax” to me. That’s part of how I feel about those songs because I think that’s life. There’s a reality, the gravity or an understanding of the human condition.

Does Taylor Explain Her Lyrics?

She would always talk about it. The narrative is essential, and kind of what it’s all about. We’d always talk about that upfront and saying that would guide me with the music. But again, she is operating at many levels where there are connections between all of these songs, or many of them are interrelated in the characters that reappear. There are threads. I think that sometimes she would point it out entirely, but I would start to see these patterns. It’s cool when you see someone’s mind working.

“the lakes”

That’s a Jack song. It’s a beautiful kind of garden, or like you’re lost in a beautiful garden. There’s a kind of Greek poetry to it. Tragic poetry, I guess.

The Meaning Of Folklore

We didn’t talk about it at first. It was only after writing six or seven songs, basically when I thought my writing was done, when we got on the phone and said, “OK, I think we’re making an album. I have these six other ideas that I love with Jack [Antonoff] that we’ve already done, and I think what we’ve done fits really well with them.” It’s sort of these narratives, these folkloric songs, with characters that interweave and are written from different perspectives. She had a vision, and it was connecting back in some way to the folk tradition, but obviously not entirely sonically. It’s more about the narrative aspect of it.

I think it’s this sort of nostalgia and wistfulness that is in a lot of the songs. A lot of them have this kind of longing for looking back on things that have happened in your life, in your friend’s life, or another loved one’s life, and the kind of storytelling around that. That was clear to her. But then we kept going, and more and more songs happened.

It was a very organic process where [meaning] wasn’t something that we really discussed. It just kind of would happen where she would dive back into the folder and find other things that were inspiring. Or she and William Bowery would write “exile,” and then that happened. There were different stages of the process.

Okay, but is it A24-core?

[Laughs.] Good comparison.

#Aaron Dessner#interview#vulture#about taylor#taylor swift#folklore album#folklore era#songwriting#producer#the national#bon iver

730 notes

·

View notes

Link

Your guide to the singer-songwriter’s surprise follow-up to Folklore.

By

CARL WILSON

When everything’s clicking for Taylor Swift, the risk is that she’s going to push it too far and overtax the public appetite. On “Mirrorball” from Folklore, she sings, with admirable self-knowledge, “I’ve never been a natural/ All I do is try, try, try.” So when I woke up yesterday to the news that at midnight she was going to repeat the trick she pulled off with Folklore in July—surprise-releasing an album of moody pop-folk songs remote-recorded in quarantine with Aaron Dessner of the National as well as her longtime producer Jack Antonoff—I was apprehensive. Would she trip back into the pattern of overexposure and backlash that happened between 1989 and Reputation?

Listening to the new Evermore, though, that doesn’t feel like such a threat. A better parallel might be to the “Side B” albums that Carly Rae Jepsen put out after both Emotion and Dedicated, springing simply out of the artist’s and her fans’ mutual enthusiasm. Or, closer to Swift’s own impulses here, publishing an author’s book of short stories soon after a successful novel. Lockdown has been a huge challenge for musicians in general, but it liberated Swift from the near-perpetual touring and publicity grind she’s been on since she was a teen, and from her sense of obligation to turn out music that revs up stadium crowds and radio programmers. Swift has always seemed most herself as the precociously talented songwriter; the pop-star side is where her try-hard, A-student awkwardness surfaces most. Quarantine came as a stretch of time to focus mainly on her maturing craft (she turns 31 on Sunday), to workshop and to woodshed. When Evermore was announced, she said that she and her collaborators—clearly mostly Dessner, who co-writes and/or co-produces all but one of these 15 songs—simply didn’t want to stop writing after Folklore.

This record further emphasizes her leap away from autobiography into songs that are either pure fictions or else lyrically symbolic in ways that don’t act as romans à clef. On Folklore, that came with the thrill of a breakthrough. Here, she fine-tunes the approach, with the result that Evermore feels like an anthology, with less of an integrated emotional throughline. But that it doesn’t feel as significant as Folklore is also its virtue. Lowered stakes offer permission to play around, to joke, to give fewer fucks—and this album definitely has the best swearing in Swift’s entire oeuvre.

Because it’s nearly all Dessner overseeing production and arrangements, there isn’t the stylistic variety that Antonoff’s greater presence brought to Folklore. However, Swift and Dessner seem to have realized that the maximalist-minimalism that dominated Folklore, with layers upon layers of restrained instrumental lines for the sake of atmosphere, was too much of a good thing. There are more breaks in the ambience on Evermore, the way there was with Folklore’s “Betty,” the countryish song that was among many listener’s favorites. But there are still moments that hazard misty lugubriousness, and perhaps with reduced reward.

Overall, people who loved Folklore will at least like Evermore too, and the minority of Swift appreciators who disapproved may even warm up to more of the sounds here. I considered doing a track-by-track comparison between the two albums, but that seemed a smidgen pathological. Instead, here is a blatantly premature Day 1 rundown of the new songs as I hear them.

A pleasant yet forgettable starting place, “Willow” has mild “tropical house” accents that recall Ed Sheeran songs of yesteryear, as well as the prolix mixed metaphors Swift can be prone to when she’s not telling a linear story. But not too severely. I like the invitation to a prospective lover to “wreck my plans.” I’m less sure why “I come back stronger than a ’90s trend” belongs in this particular song, though it’s witty. “Willow” is more fun as a video (a direct sequel to Folklore’s “Cardigan” video) than as a lead track, but I’m not mad at it here either.

Written with “William Bowery”—the pseudonym of Swift’s boyfriend Joe Alwyn, as she’s recently confirmed—this is the first of the full story songs on Evermore, in this case a woman describing having walked away from her partner on the night he planned to propose. The music is a little floaty and non-propulsive, but the tale is well painted, with Swift’s protagonist willingly taking the blame for her beau’s heartbreak and shrugging off the fury of his family and friends—“she would have made such a lovely bride/ too bad she’s fucked in the head.” Swift sticks to her most habitual vocal cadences, but not much here goes to waste. Except, that is, for the title phrase, which doesn’t feel like it adds anything substantial. (Unless the protagonist was drunk?) I do love the little throwaway piano filigree Dessner plays as a tag on the end.

This is the sole track Antonoff co-wrote and produced, and it’s where a subdued take on the spirit of 1989-style pop resurges with necessary energy. Swift is singing about having a crush on someone who’s too attractive, too in-demand, and relishing the fantasy but also enjoying passing it up. It includes some prime Swiftian details, like, “With my Eagles t-shirt hanging from your door,” or, “At dinner parties I call you out on your contrarian shit.” The line about this thirst trap’s “hair falling into place like dominos” I find much harder to picture.

This is where I really snapped to attention. After a few earlier attempts, Swift has finally written her great Christmas song, one to stand alongside “New Year’s Day” in her holiday canon. And it’s especially a great one for 2020, full of things none of us ought to do this year—go home to visit our parents, hook up with an ex, spend the weekend in their bedroom and their truck, then break their hearts again when we leave. But it’s done with sincere yuletide affection to “the only soul who can tell which smiles I’m faking,” and “the warmest bed I’ve ever known.” All the better, we get to revisit these characters later on the album.

On first listen, I found this one of the draggiest Dressner compositions on the record. Swift locates a specific emotional state recognizably and poignantly in this song about a woman trapped (or, she wonders, maybe not trapped?) in a relationship with an emotionally withholding, unappreciative man. But the static keyboard chord patterns and the wandering melody that might be meant to evoke a sense of disappointment and numbness risk yielding numbing and disappointing music. Still, it’s growing on me.

Featuring two members of Haim—and featuring a character named after one of them, Este—“No Body, No Crime” is a straight-up contemporary country song, specifically a twist on and tribute to the wronged-woman vengeance songs that were so popular more than a decade ago, and even more specifically “Before He Cheats,” the 2006 smash by Carrie Underwood, of which it’s a near musical clone, just downshifted a few gears. Swift’s intricate variation on the model is that the singer of the song isn’t wreaking revenge on her own husband, but on her best friend’s husband, and framing the husband’s mistress for the murder. It’s delicious, except that Swift commits the capital offence of underusing the Haim sisters purely as background singers, aside from one spoken interjection from Danielle.

This one has some of the same issues as “Tolerate It,” in that it lags too much for too long, but I did find more to focus on musically here. Lyrically and vocally, it gets the mixed emotions of a relatively amicable divorce awfully damned right, if I may speak from painfully direct experience.

This is the song sung from the POV of the small-town lover that the ambitious L.A. actress from “Tis the Damn Season”—Dorothea, it turns out—has left behind in, it turns out, Tupelo. Probably some years past that Xmas tryst, when the old flame finally has made it. “A tiny screen’s the only place I see you now,” he sings, but adds that she’s welcome back anytime: “If you’re ever tired of being known/ For who you know/ You know that you’ll always know me.” It’s produced and arranged with a welcome lack of fuss. Swift hauls out her old high-school-romance-songs vocal tone to reminisce about “skipping the prom/ just to piss off your mom,” very much in the vein of Folklore’s teen-love-triangle trilogy.

A duet with Dessner’s baritone-voiced bandmate in the National, Matt Berninger, “Coney Island” suffers from the most convoluted lyrics on Evermore (which, I wonder unkindly, might be what brought Berninger to mind?). The refrain “I’m on a beach on Coney Island, wondering where did my baby go” is a terrific tribute to classic pop, but then Swift rhymes it with “the bright lights, the merry go,” as if that’s a serviceable shorthand for merry-go-round, and says “sorry for not making you my centerfold,” as if that’s somehow a desirable relationship outcome. The comparison of the bygone affair to “the mall before the internet/ It was the one place to be” is clever but not exactly moving, and Berninger’s lines are worse. Dessner’s droning arrangement does not come to the rescue.

This song is also overrun with metaphors but mostly in an enticing, thematically fitting way, full of good Swiftian dark-fairytale grist. It’s fun to puzzle out gradually the secret that all the images are concealing—an engaged woman being drawn into a clandestine affair. And there are several very good “goddamns.”

The lyrical conceit here is great, about two gold-digging con artists whose lives of scamming are undone by their falling in love. It reminded me of the 1931 pre-Code rom-com Blonde Crazy, in which James Cagney and Joan Blondell act out a very similar storyline. And I mostly like the song, but I can’t help thinking it would come alive more if the music sounded anything like what these self-declared “cowboys” and “villains” might sing. It’s massively melancholy for the story, and Swift needs a far more winningly roguish duet partner than the snoozy Marcus Mumford. It does draw a charge from a couple of fine guitar solos, which I think are played by Justin Vernon (aka Bon Iver, who will return shortly).

The drum machine comes as a refreshing novelty at this point. And while this song is mostly standard Taylor Swift torrents of romantic-conflict wordplay (full of golden gates and pedestals and dropping her swords and breaking her high heel, etc.), the pleasure comes in hearing her look back at all that and shrugging, “Long story short, it was a bad ti-i-ime,” “long story short, it was the wrong guy-uy-uy,” and finally, “long story short, I survived.” She passes along some counsel I’m sure she wishes she’d had back in the days of Reputation: “I wanna tell you not to get lost in these petty things/ Your nemeses will defeat themselves.” It’s a fairly slight song but an earned valedictory address.

Swift fan lore has it that she always sequences the real emotional bombshell as Track 5, but here it is at 13, her lucky number. It’s sung to her grandmother, Marjorie Finlay, who died when Swift was in her early teens, and it manages to be utterly personal—down to the sample of Marjorie singing opera on the outro—and simultaneously utterly evocative to anyone who’s been through such grief. The bridge, full of vivid memories and fierce regrets, is the clincher.

This electroacoustic kiss-off song, loaded up with at least a fistful of gecs if not a full 100 by Dessner and co-producers BJ Burton and James McAlister, seems to be, lyrically, one of Swift’s somewhat tedious public airings of some music-industry grudge (on which, in case you don’t get it, she does not want “closure”), but, sonically, it’s a real ear-cleaner at this point on Evermore. Why she seems to shift into a quasi-British accent for fragments of it is anyone’s guess. But I’m tickled by the line, “I’m fine with my spite and my tears and my beers and my candles.”

I’m torn about the vague imagery and vague music of the first few verses of the album’s final, title track. But when Vernon, in full multitracked upper-register Bon Iver mode, kicks in for the duet in the middle, there’s a jolt of urgency that lands the redemptive ending—whether it’s about a crisis in love or the collective crisis of the pandemic or perhaps a bit of both—and satisfyingly rounds off the album.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

New top story from Time: Let’s Break Down Taylor Swift’s Tender New Album Folklore

If there’s one thing we know about Taylor Swift, it’s that she works hard. In her documentary released earlier this year, Miss Americana, the intense pace of Swift’s life — and the similarly intense pressures of the scrutiny she finds herself under — was laid bare for all to analyze.

But then the coronavirus pandemic swept in and, presumably, cleared her pop star slate. Swift was left with her privacy, as lockdowns shuttered us all into our homes. On social media, she was neither cryptically silent nor strategically active: she seemed, for the first time in a long time, like she was just living her life and drinking wine on her couch like many of us, big plans on hold.

But even in her downtime, curtains drawn on her celebrity, Swift was creating. The July 23 release of Folklore, her 16-track eighth album, came as a surprise even to devout followers: only 11 months after Lover, it was the first time she’d put out a project on less than a two-year schedule. Swift didn’t bother with the extensive teasing release of past albums; she announced her work on Thursday, rolled it out on Friday and then will sit back over the weekend and enjoy the warm response.

In isolation my imagination has run wild and this album is the result. I’ve told these stories to the best of my ability with all the love, wonder, and whimsy they deserve. Now it’s up to you to pass them down. folklore is out now: https://t.co/xdcEDfithq

📷: Beth Garrabrant pic.twitter.com/vSDo9Se0fp

— Taylor Swift (@taylorswift13) July 24, 2020

A new sound

In releasing Folklore, Swift was clear and direct about her intent and her work. She shared the names of all the major collaborators she worked with: pop producer and longtime musical partner Jack Antonoff, who she called “musical family;” her “musical heroes,” the moody rock band The National’s Aaron Dessnerr and indie god Justin Vernon of Bon Iver; a mysteriously-named collaborator called William Bowery. That, and the greyscale, woodsy images she teased the release with, announced her new direction: alternative pop-folk. In her delicate, confessional singing and melodies there are hints of fellow artists like Lana Del Rey, for whom she has openly expressed admiration before, on “Cardigan” and Phoebe Bridgers on “Seven.” There’s the twinkling Postal-Service-referencing intro on “The Last Great American Dynasty,” the blissed-out orchestral walls of sound on “Epiphany,” the serving of elegiac Sufjan Stevens keys on “Invisible String.”

youtube

Despite her start as a Nashville darling in the country scene, Swift has always been a musical chameleon. She evolved into rock-pop by 1989, stretched herself into hip-hop on the spiky Reputation, went full-throated pop on Lover. Folklore is what a lot of fans have been waiting for all along: a lengthy, emotionally-wrought indie album. Its heart is folk storytelling. Its production is every kind of thing fans have heard and loved on breakup albums in the last decade. Its vision is a grey-blue soundscape: an autumnal album dropped on us in the heat of summer, the first full project of this kind from Swift, inhabiting a truly melancholy space she’s mainly hinted at in past ballads.

But those ballads have often been her most poignant work. Folklore meets her exactly where she’s strongest, right now. And the rest of us? Still adjusting to pandemic life, still engaged in important conversations about our country’s racist history, we might also want something at just this unhurried tempo.

“And some things you just can’t speak about”

It would be fruitless to break down every Swift lyric; the songwriting can be poetically obtuse, and she’s telling many stories, from many character points of view, with many aching regrets. Swift has historically been one of our most confessional pop stars in her music, often mining her personal archives for material. Folklore is a little more, well, folkloric: “The lines between fantasy and reality blur and the boundaries between truth and fiction become almost indiscernible,” she shared in an advance statement about the lyrical content. Still, as she announced in advance, she buried plenty of Easter eggs in her words for her fans to unpack at will.

The opening song, “The 1,” is an ode to what could have been. The “who” of it all, of course, remains murky.

But we were something, don’t you think so?

Roaring twenties, tossing pennies in the pool

And if my wishes came true

It would’ve been you.

As avid listeners well know, Swift loves riffs on the past. She also loves to weave in references to her old music, a trail of breadcrumbs for fans to follow from era to era. “To kiss in cars and downtown bars was all we needed,” she sings on “Cardigan,” and it sounds a lot like an echo of her lyrics on Lover’s “Cornelia Street” (“We were in the backseat, drunk on something stronger than the drinks in the bar”). And when she sings “You drew stars around my scars” on the same song, close followers might flash back to the “guitar string scars” of “Lover.”

Every song has these kinds of lyrical winks, reinforcing the universe that Swift has crafted even as she expands it with her newfound layers of fantasy and character. “Mad Woman,” for instance, is the story of a “misfit widow getting gleeful revenge,” according to her note on social media. But lines like “And women like hunting witches too” harken back to her Reputation era (“They’re burning all the witches even if you aren’t one,” she sings on “I Did Something Bad”).

View this post on Instagram

In isolation my imagination has run wild and this album is the result, a collection of songs and stories that flowed like a stream of consciousness. Picking up a pen was my way of escaping into fantasy, history, and memory. I’ve told these stories to the best of my ability with all the love, wonder, and whimsy they deserve. Now it’s up to you to pass them down. folklore is out now. 📷: Beth Garrabrant

A post shared by Taylor Swift (@taylorswift) on Jul 23, 2020 at 9:06pm PDT

Some songs are more mysterious than others. “Exile,” with Bon Iver, reeks with the pain of parting. “Hoax,” a quiet piano ballad, details a relationship flawed but lasting. (“No other sadness in the world would do” is a devastatingly universal reminder of that bittersweet sensation.) “The Last Great American Dynasty,” in contrast, is specific and historical: the story of socialite Rebekah Harkness, the prior inhabitant of Swift’s own expansive Rhode Island estate. On “Epiphany,” Swift dives into the experience of another historical character: her grandfather, Dean, when he landed on the beaches of Guadalcanal in 1942. “And some things,” she sings after describing a harrowing moment of war, “you just can’t speak about.”

OK, but what about “Betty”?

One of the songs on Folklore that caught the most early attention online is “Betty,” a late-album track that sees Swift return most directly to her country roots. (Cue the plaintive harmonica.) In her notes, Swift explained: “There’s a collection of three songs I refer to as The Teenage Love Triangle. These three songs explore a love triangle from all three people’s perspectives at different times in their lives.” Consensus has led listeners to believe the three songs in question are “Betty,” “Cardigan” and “August.” Woven together, they tell a story of betrayal, heartache and sweet teen angst.

But “Betty” can also be read as vaguely autobiographical, which some fans are keen to do. The two other characters in the trio, James and Ines, happen to be the names of the two daughters of Swift’s friends Blake Lively and Ryan Reynolds, deepening the connection to her real-life friend circle and the Swiftian world we know. Either way, the web of perspectives and emotions outlined in the track trio presents Swift fans with plenty of material to parse through as they unravel the mystery of Swift’s feelings and her new album’s connotations.

The quarantine album

In quarantine, any album release finds new resonance. With so few events to attend, live music still mostly canceled and many artists postponing their work, fresh projects are bound to find rapt audiences whether or not they are coming from Taylor Swift.

But Swift, being Swift, was always destined to conjure up a powerful reaction. In the past year, Taylor Swift’s public dispute with music manager Scooter Braun over her music catalog made headlines and raised questions about the ownership artists have over the music they create. Prior to that, she often drew tabloid scrutiny. Her response has often been to write it all out: address past relationships, excavate heartbreak and frustration, insist on resilience. That Folklore is foggy, that it relies more on smart songwriting and less on speculation about her personal life and complicated visual cues, suggests it’s bound for a long shelf life.

Quarantine has us all dragging up old memories and wondering what’s still real. Folklore isn’t the pop star album that will drive worries away and replace them with sparkle. It’s an artist who’s extended her ambitions to looking back and getting a little lost in the memory haze, digging up an old favorite cardigan for comfort.

from Blogger https://ift.tt/2WRAAJ2

via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

If there’s one thing we know about Taylor Swift, it’s that she works hard. In her documentary released earlier this year, Miss Americana, the intense pace of Swift’s life — and the similarly intense pressures of the scrutiny she finds herself under — was laid bare for all to analyze.

But then the coronavirus pandemic swept in and, presumably, cleared her pop star slate. Swift was left with her privacy, as lockdowns shuttered us all into our homes. On social media, she was neither cryptically silent nor strategically active: she seemed, for the first time in a long time, like she was just living her life and drinking wine on her couch like many of us, big plans on hold.

But even in her downtime, curtains drawn on her celebrity, Swift was creating. The July 23 release of Folklore, her 16-track eighth album, came as a surprise even to devout followers: only 11 months after Lover, it was the first time she’d put out a project on less than a two-year schedule. Swift didn’t bother with the extensive teasing release of past albums; she announced her work on Thursday, rolled it out on Friday and then will sit back over the weekend and enjoy the warm response.

In isolation my imagination has run wild and this album is the result. I’ve told these stories to the best of my ability with all the love, wonder, and whimsy they deserve. Now it’s up to you to pass them down. folklore is out now: https://t.co/xdcEDfithq

📷: Beth Garrabrant pic.twitter.com/vSDo9Se0fp

— Taylor Swift (@taylorswift13) July 24, 2020

A new sound

In releasing Folklore, Swift was clear and direct about her intent and her work. She shared the names of all the major collaborators she worked with: pop producer and longtime musical partner Jack Antonoff, who she called “musical family;” her “musical heroes,” the moody rock band The National’s Aaron Dessnerr and indie god Justin Vernon of Bon Iver; a mysteriously-named collaborator called William Bowery. That, and the greyscale, woodsy images she teased the release with, announced her new direction: alternative pop-folk. In her delicate, confessional singing and melodies there are hints of fellow artists like Lana Del Rey, for whom she has openly expressed admiration before, on “Cardigan” and Phoebe Bridgers on “Seven.” There’s the twinkling Postal-Service-referencing intro on “The Last Great American Dynasty,” the blissed-out orchestral walls of sound on “Epiphany,” the serving of elegiac Sufjan Stevens keys on “Invisible String.”

Despite her start as a Nashville darling in the country scene, Swift has always been a musical chameleon. She evolved into rock-pop by 1989, stretched herself into hip-hop on the spiky Reputation, went full-throated pop on Lover. Folklore is what a lot of fans have been waiting for all along: a lengthy, emotionally-wrought indie album. Its heart is folk storytelling. Its production is every kind of thing fans have heard and loved on breakup albums in the last decade. Its vision is a grey-blue soundscape: an autumnal album dropped on us in the heat of summer, the first full project of this kind from Swift, inhabiting a truly melancholy space she’s mainly hinted at in past ballads.

But those ballads have often been her most poignant work. Folklore meets her exactly where she’s strongest, right now. And the rest of us? Still adjusting to pandemic life, still engaged in important conversations about our country’s racist history, we might also want something at just this unhurried tempo.

“And some things you just can’t speak about”

It would be fruitless to break down every Swift lyric; the songwriting can be poetically obtuse, and she’s telling many stories, from many character points of view, with many aching regrets. Swift has historically been one of our most confessional pop stars in her music, often mining her personal archives for material. Folklore is a little more, well, folkloric: “The lines between fantasy and reality blur and the boundaries between truth and fiction become almost indiscernible,” she shared in an advance statement about the lyrical content. Still, as she announced in advance, she buried plenty of Easter eggs in her words for her fans to unpack at will.

The opening song, “The 1,” is an ode to what could have been. The “who” of it all, of course, remains murky.

But we were something, don’t you think so?

Roaring twenties, tossing pennies in the pool

And if my wishes came true

It would’ve been you.

As avid listeners well know, Swift loves riffs on the past. She also loves to weave in references to her old music, a trail of breadcrumbs for fans to follow from era to era. “To kiss in cars and downtown bars was all we needed,” she sings on “Cardigan,” and it sounds a lot like an echo of her lyrics on Lover’s “Cornelia Street” (“We were in the backseat, drunk on something stronger than the drinks in the bar”). And when she sings “You drew stars around my scars” on the same song, close followers might flash back to the “guitar string scars” of “Lover.”

Every song has these kinds of lyrical winks, reinforcing the universe that Swift has crafted even as she expands it with her newfound layers of fantasy and character. “Mad Woman,” for instance, is the story of a “misfit widow getting gleeful revenge,” according to her note on social media. But lines like “And women like hunting witches too” harken back to her Reputation era (“They’re burning all the witches even if you aren’t one,” she sings on “I Did Something Bad”).

View this post on Instagram

In isolation my imagination has run wild and this album is the result, a collection of songs and stories that flowed like a stream of consciousness. Picking up a pen was my way of escaping into fantasy, history, and memory. I’ve told these stories to the best of my ability with all the love, wonder, and whimsy they deserve. Now it’s up to you to pass them down. folklore is out now. 📷: Beth Garrabrant

A post shared by Taylor Swift (@taylorswift) on Jul 23, 2020 at 9:06pm PDT

Some songs are more mysterious than others. “Exile,” with Bon Iver, reeks with the pain of parting. “Hoax,” a quiet piano ballad, details a relationship flawed but lasting. (“No other sadness in the world would do” is a devastatingly universal reminder of that bittersweet sensation.) “The Last Great American Dynasty,” in contrast, is specific and historical: the story of socialite Rebekah Harkness, the prior inhabitant of Swift’s own expansive Rhode Island estate. On “Epiphany,” Swift dives into the experience of another historical character: her grandfather, Dean, when he landed on the beaches of Guadalcanal in 1942. “And some things,” she sings after describing a harrowing moment of war, “you just can’t speak about.”

OK, but what about “Betty”?

One of the songs on Folklore that caught the most early attention online is “Betty,” a late-album track that sees Swift return most directly to her country roots. (Cue the plaintive harmonica.) In her notes, Swift explained: “There’s a collection of three songs I refer to as The Teenage Love Triangle. These three songs explore a love triangle from all three people’s perspectives at different times in their lives.” Consensus has led listeners to believe the three songs in question are “Betty,” “Cardigan” and “August.” Woven together, they tell a story of betrayal, heartache and sweet teen angst.

But “Betty” can also be read as vaguely autobiographical, which some fans are keen to do. The two other characters in the trio, James and Ines, happen to be the names of the two daughters of Swift’s friends Blake Lively and Ryan Reynolds, deepening the connection to her real-life friend circle and the Swiftian world we know. Either way, the web of perspectives and emotions outlined in the track trio presents Swift fans with plenty of material to parse through as they unravel the mystery of Swift’s feelings and her new album’s connotations.

The quarantine album

In quarantine, any album release finds new resonance. With so few events to attend, live music still mostly canceled and many artists postponing their work, fresh projects are bound to find rapt audiences whether or not they are coming from Taylor Swift.

But Swift, being Swift, was always destined to conjure up a powerful reaction. In the past year, Taylor Swift’s public dispute with music manager Scooter Braun over her music catalog made headlines and raised questions about the ownership artists have over the music they create. Prior to that, she often drew tabloid scrutiny. Her response has often been to write it all out: address past relationships, excavate heartbreak and frustration, insist on resilience. That Folklore is foggy, that it relies more on smart songwriting and less on speculation about her personal life and complicated visual cues, suggests it’s bound for a long shelf life.

Quarantine has us all dragging up old memories and wondering what’s still real. Folklore isn’t the pop star album that will drive worries away and replace them with sparkle. It’s an artist who’s extended her ambitions to looking back and getting a little lost in the memory haze, digging up an old favorite cardigan for comfort.

from TIME https://ift.tt/2ZXLuiw

0 notes

Link

If there’s one thing we know about Taylor Swift, it’s that she works hard. In her documentary released earlier this year, Miss Americana, the intense pace of Swift’s life — and the similarly intense pressures of the scrutiny she finds herself under — was laid bare for all to analyze.

But then the coronavirus pandemic swept in and, presumably, cleared her pop star slate. Swift was left with her privacy, as lockdowns shuttered us all into our homes. On social media, she was neither cryptically silent nor strategically active: she seemed, for the first time in a long time, like she was just living her life and drinking wine on her couch like many of us, big plans on hold.

But even in her downtime, curtains drawn on her celebrity, Swift was creating. The July 23 release of Folklore, her 16-track eighth album, came as a surprise even to devout followers: only 11 months after Lover, it was the first time she’d put out a project on less than a two-year schedule. Swift didn’t bother with the extensive teasing release of past albums; she announced her work on Thursday, rolled it out on Friday and then will sit back over the weekend and enjoy the warm response.

In isolation my imagination has run wild and this album is the result. I’ve told these stories to the best of my ability with all the love, wonder, and whimsy they deserve. Now it’s up to you to pass them down. folklore is out now: https://t.co/xdcEDfithq

📷: Beth Garrabrant pic.twitter.com/vSDo9Se0fp

— Taylor Swift (@taylorswift13) July 24, 2020

A new sound

In releasing Folklore, Swift was clear and direct about her intent and her work. She shared the names of all the major collaborators she worked with: pop producer and longtime musical partner Jack Antonoff, who she called “musical family;” her “musical heroes,” the moody rock band The National’s Aaron Dessnerr and indie god Justin Vernon of Bon Iver; a mysteriously-named collaborator called William Bowery. That, and the greyscale, woodsy images she teased the release with, announced her new direction: alternative pop-folk. In her delicate, confessional singing and melodies there are hints of fellow artists like Lana Del Rey, for whom she has openly expressed admiration before, on “Cardigan” and Phoebe Bridgers on “Seven.” There’s the twinkling Postal-Service-referencing intro on “The Last Great American Dynasty,” the blissed-out orchestral walls of sound on “Epiphany,” the serving of elegiac Sufjan Stevens keys on “Invisible String.”

Despite her start as a Nashville darling in the country scene, Swift has always been a musical chameleon. She evolved into rock-pop by 1989, stretched herself into hip-hop on the spiky Reputation, went full-throated pop on Lover. Folklore is what a lot of fans have been waiting for all along: a lengthy, emotionally-wrought indie album. Its heart is folk storytelling. Its production is every kind of thing fans have heard and loved on breakup albums in the last decade. Its vision is a grey-blue soundscape: an autumnal album dropped on us in the heat of summer, the first full project of this kind from Swift, inhabiting a truly melancholy space she’s mainly hinted at in past ballads.

But those ballads have often been her most poignant work. Folklore meets her exactly where she’s strongest, right now. And the rest of us? Still adjusting to pandemic life, still engaged in important conversations about our country’s racist history, we might also want something at just this unhurried tempo.

“And some things you just can’t speak about”

It would be fruitless to break down every Swift lyric; the songwriting can be poetically obtuse, and she’s telling many stories, from many character points of view, with many aching regrets. Swift has historically been one of our most confessional pop stars in her music, often mining her personal archives for material. Folklore is a little more, well, folkloric: “The lines between fantasy and reality blur and the boundaries between truth and fiction become almost indiscernible,” she shared in an advance statement about the lyrical content. Still, as she announced in advance, she buried plenty of Easter eggs in her words for her fans to unpack at will.

The opening song, “The 1,” is an ode to what could have been. The “who” of it all, of course, remains murky.

But we were something, don’t you think so?

Roaring twenties, tossing pennies in the pool

And if my wishes came true

It would’ve been you.

As avid listeners well know, Swift loves riffs on the past. She also loves to weave in references to her old music, a trail of breadcrumbs for fans to follow from era to era. “To kiss in cars and downtown bars was all we needed,” she sings on “Cardigan,” and it sounds a lot like an echo of her lyrics on Lover’s “Cornelia Street” (“We were in the backseat, drunk on something stronger than the drinks in the bar”). And when she sings “You drew stars around my scars” on the same song, close followers might flash back to the “guitar string scars” of “Lover.”

Every song has these kinds of lyrical winks, reinforcing the universe that Swift has crafted even as she expands it with her newfound layers of fantasy and character. “Mad Woman,” for instance, is the story of a “misfit widow getting gleeful revenge,” according to her note on social media. But lines like “And women like hunting witches too” harken back to her Reputation era (“They’re burning all the witches even if you aren’t one,” she sings on “I Did Something Bad”).

View this post on Instagram

In isolation my imagination has run wild and this album is the result, a collection of songs and stories that flowed like a stream of consciousness. Picking up a pen was my way of escaping into fantasy, history, and memory. I’ve told these stories to the best of my ability with all the love, wonder, and whimsy they deserve. Now it’s up to you to pass them down. folklore is out now. 📷: Beth Garrabrant

A post shared by Taylor Swift (@taylorswift) on Jul 23, 2020 at 9:06pm PDT

Some songs are more mysterious than others. “Exile,” with Bon Iver, reeks with the pain of parting. “Hoax,” a quiet piano ballad, details a relationship flawed but lasting. (“No other sadness in the world would do” is a devastatingly universal reminder of that bittersweet sensation.) “The Last Great American Dynasty,” in contrast, is specific and historical: the story of socialite Rebekah Harkness, the prior inhabitant of Swift’s own expansive Rhode Island estate. On “Epiphany,” Swift dives into the experience of another historical character: her grandfather, Dean, when he landed on the beaches of Guadalcanal in 1942. “And some things,” she sings after describing a harrowing moment of war, “you just can’t speak about.”

OK, but what about “Betty”?

One of the songs on Folklore that caught the most early attention online is “Betty,” a late-album track that sees Swift return most directly to her country roots. (Cue the plaintive harmonica.) In her notes, Swift explained: “There’s a collection of three songs I refer to as The Teenage Love Triangle. These three songs explore a love triangle from all three people’s perspectives at different times in their lives.” Consensus has led listeners to believe the three songs in question are “Betty,” “Cardigan” and “August.” Woven together, they tell a story of betrayal, heartache and sweet teen angst.

But “Betty” can also be read as vaguely autobiographical, which some fans are keen to do. The two other characters in the trio, James and Ines, happen to be the names of the two daughters of Swift’s friends Blake Lively and Ryan Reynolds, deepening the connection to her real-life friend circle and the Swiftian world we know. Either way, the web of perspectives and emotions outlined in the track trio presents Swift fans with plenty of material to parse through as they unravel the mystery of Swift’s feelings and her new album’s connotations.

The quarantine album

In quarantine, any album release finds new resonance. With so few events to attend, live music still mostly canceled and many artists postponing their work, fresh projects are bound to find rapt audiences whether or not they are coming from Taylor Swift.

But Swift, being Swift, was always destined to conjure up a powerful reaction. In the past year, Taylor Swift’s public dispute with music manager Scooter Braun over her music catalog made headlines and raised questions about the ownership artists have over the music they create. Prior to that, she often drew tabloid scrutiny. Her response has often been to write it all out: address past relationships, excavate heartbreak and frustration, insist on resilience. That Folklore is foggy, that it relies more on smart songwriting and less on speculation about her personal life and complicated visual cues, suggests it’s bound for a long shelf life.

Quarantine has us all dragging up old memories and wondering what’s still real. Folklore isn’t the pop star album that will drive worries away and replace them with sparkle. It’s an artist who’s extended her ambitions to looking back and getting a little lost in the memory haze, digging up an old favorite cardigan for comfort.

0 notes

Link

If there’s one thing we know about Taylor Swift, it’s that she works hard. In her documentary released earlier this year, Miss Americana, the intense pace of Swift’s life — and the similarly intense pressures of the scrutiny she finds herself under — was laid bare for all to analyze.

But then the coronavirus pandemic swept in and, presumably, cleared her pop star slate. Swift was left with her privacy, as lockdowns shuttered us all into our homes. On social media, she was neither cryptically silent nor strategically active: she seemed, for the first time in a long time, like she was just living her life and drinking wine on her couch like many of us, big plans on hold.

But even in her downtime, curtains drawn on her celebrity, Swift was creating. The July 23 release of Folklore, her 16-track eighth album, came as a surprise even to devout followers: only 11 months after Lover, it was the first time she’d put out a project on less than a two-year schedule. Swift didn’t bother with the extensive teasing release of past albums; she announced her work on Thursday, rolled it out on Friday and then will sit back over the weekend and enjoy the warm response.

In isolation my imagination has run wild and this album is the result. I’ve told these stories to the best of my ability with all the love, wonder, and whimsy they deserve. Now it’s up to you to pass them down. folklore is out now: https://t.co/xdcEDfithq

📷: Beth Garrabrant pic.twitter.com/vSDo9Se0fp

— Taylor Swift (@taylorswift13) July 24, 2020

A new sound

In releasing Folklore, Swift was clear and direct about her intent and her work. She shared the names of all the major collaborators she worked with: pop producer and longtime musical partner Jack Antonoff, who she called “musical family;” her “musical heroes,” the moody rock band The National’s Aaron Dessnerr and indie god Justin Vernon of Bon Iver; a mysteriously-named collaborator called William Bowery. That, and the greyscale, woodsy images she teased the release with, announced her new direction: alternative pop-folk. In her delicate, confessional singing and melodies there are hints of fellow artists like Lana Del Rey, for whom she has openly expressed admiration before, on “Cardigan” and Phoebe Bridgers on “Seven.” There’s the twinkling Postal-Service-referencing intro on “The Last Great American Dynasty,” the blissed-out orchestral walls of sound on “Epiphany,” the serving of elegiac Sufjan Stevens keys on “Invisible String.”

Despite her start as a Nashville darling in the country scene, Swift has always been a musical chameleon. She evolved into rock-pop by 1989, stretched herself into hip-hop on the spiky Reputation, went full-throated pop on Lover. Folklore is what a lot of fans have been waiting for all along: a lengthy, emotionally-wrought indie album. Its heart is folk storytelling. Its production is every kind of thing fans have heard and loved on breakup albums in the last decade. Its vision is a grey-blue soundscape: an autumnal album dropped on us in the heat of summer, the first full project of this kind from Swift, inhabiting a truly melancholy space she’s mainly hinted at in past ballads.

But those ballads have often been her most poignant work. Folklore meets her exactly where she’s strongest, right now. And the rest of us? Still adjusting to pandemic life, still engaged in important conversations about our country’s racist history, we might also want something at just this unhurried tempo.

“And some things you just can’t speak about”

It would be fruitless to break down every Swift lyric; the songwriting can be poetically obtuse, and she’s telling many stories, from many character points of view, with many aching regrets. Swift has historically been one of our most confessional pop stars in her music, often mining her personal archives for material. Folklore is a little more, well, folkloric: “The lines between fantasy and reality blur and the boundaries between truth and fiction become almost indiscernible,” she shared in an advance statement about the lyrical content. Still, as she announced in advance, she buried plenty of Easter eggs in her words for her fans to unpack at will.

The opening song, “The 1,” is an ode to what could have been. The “who” of it all, of course, remains murky.

But we were something, don’t you think so?

Roaring twenties, tossing pennies in the pool

And if my wishes came true

It would’ve been you.

As avid listeners well know, Swift loves riffs on the past. She also loves to weave in references to her old music, a trail of breadcrumbs for fans to follow from era to era. “To kiss in cars and downtown bars was all we needed,” she sings on “Cardigan,” and it sounds a lot like an echo of her lyrics on Lover’s “Cornelia Street” (“We were in the backseat, drunk on something stronger than the drinks in the bar”). And when she sings “You drew stars around my scars” on the same song, close followers might flash back to the “guitar string scars” of “Lover.”

Every song has these kinds of lyrical winks, reinforcing the universe that Swift has crafted even as she expands it with her newfound layers of fantasy and character. “Mad Woman,” for instance, is the story of a “misfit widow getting gleeful revenge,” according to her note on social media. But lines like “And women like hunting witches too” harken back to her Reputation era (“They’re burning all the witches even if you aren’t one,” she sings on “I Did Something Bad”).

View this post on Instagram

In isolation my imagination has run wild and this album is the result, a collection of songs and stories that flowed like a stream of consciousness. Picking up a pen was my way of escaping into fantasy, history, and memory. I’ve told these stories to the best of my ability with all the love, wonder, and whimsy they deserve. Now it’s up to you to pass them down. folklore is out now. 📷: Beth Garrabrant

A post shared by Taylor Swift (@taylorswift) on Jul 23, 2020 at 9:06pm PDT

Some songs are more mysterious than others. “Exile,” with Bon Iver, reeks with the pain of parting. “Hoax,” a quiet piano ballad, details a relationship flawed but lasting. (“No other sadness in the world would do” is a devastatingly universal reminder of that bittersweet sensation.) “The Last Great American Dynasty,” in contrast, is specific and historical: the story of socialite Rebekah Harkness, the prior inhabitant of Swift’s own expansive Rhode Island estate. On “Epiphany,” Swift dives into the experience of another historical character: her grandfather, Dean, when he landed on the beaches of Guadalcanal in 1942. “And some things,” she sings after describing a harrowing moment of war, “you just can’t speak about.”

OK, but what about “Betty”?

One of the songs on Folklore that caught the most early attention online is “Betty,” a late-album track that sees Swift return most directly to her country roots. (Cue the plaintive harmonica.) In her notes, Swift explained: “There’s a collection of three songs I refer to as The Teenage Love Triangle. These three songs explore a love triangle from all three people’s perspectives at different times in their lives.” Consensus has led listeners to believe the three songs in question are “Betty,” “Cardigan” and “August.” Woven together, they tell a story of betrayal, heartache and sweet teen angst.

But “Betty” can also be read as vaguely autobiographical, which some fans are keen to do. The two other characters in the trio, James and Ines, happen to be the names of the two daughters of Swift’s friends Blake Lively and Ryan Reynolds, deepening the connection to her real-life friend circle and the Swiftian world we know. Either way, the web of perspectives and emotions outlined in the track trio presents Swift fans with plenty of material to parse through as they unravel the mystery of Swift’s feelings and her new album’s connotations.

The quarantine album

In quarantine, any album release finds new resonance. With so few events to attend, live music still mostly canceled and many artists postponing their work, fresh projects are bound to find rapt audiences whether or not they are coming from Taylor Swift.

But Swift, being Swift, was always destined to conjure up a powerful reaction. In the past year, Taylor Swift’s public dispute with music manager Scooter Braun over her music catalog made headlines and raised questions about the ownership artists have over the music they create. Prior to that, she often drew tabloid scrutiny. Her response has often been to write it all out: address past relationships, excavate heartbreak and frustration, insist on resilience. That Folklore is foggy, that it relies more on smart songwriting and less on speculation about her personal life and complicated visual cues, suggests it’s bound for a long shelf life.

Quarantine has us all dragging up old memories and wondering what’s still real. Folklore isn’t the pop star album that will drive worries away and replace them with sparkle. It’s an artist who’s extended her ambitions to looking back and getting a little lost in the memory haze, digging up an old favorite cardigan for comfort.

0 notes