#followed by Taobao / Tmall and then Baidu Search.

Text

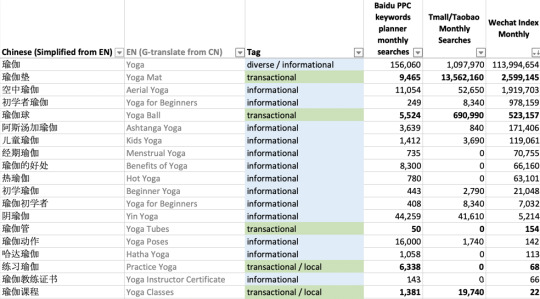

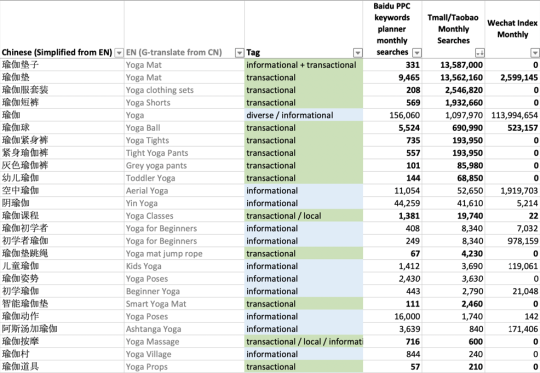

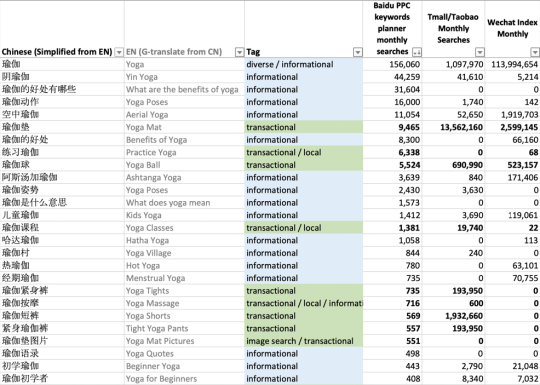

#🇨🇳#ecommerce#socialmedia#search#SEO#Maybe some of you remember that I asked in summer for some B2C topics#that you thought one might be better off focusing on Ecommerce platforms and Social Media in China than on organic & paid Search (= SEO & S#Well#I have been a little busy - so I couldn't follow up in time.#But I finally did look at some numbers. Spoiler Moonie Zhu - you were right: There is so much more to gain on E-commerce platforms and Soci#But there is also a little twist to this story - in the end.#Let me summarize the numbers for you:#I looked at around 3#300 keywords from the Yoga industry.#I gathered them using some different tools (including Searchmetrics of course - but some others as well) plus some input from my friends Ja#For you to better understand them#I auto-translated them using Google Translate (you'll see that in one column in the screenshots).#For those Chinese keywords I got the Baidu Search Volume from Baidu Keyword Planner#the monthly searches of China's biggest ecommerce platform Taobao / Tmall and the monthly Wechat Index numbers to cover the most important#that should be enough.#In the first three screenshots you can see the top keywords by Search Volume (for Wechat the Monthly Index) in descending order for those t#Es wurde kein Alt-Text für dieses Bild angegeben.#The keywords sorted by Baidu Keyword Tool Monthly Search Volume#The keywords sorted by Taobao / Tmall monthly Search Volume#The keywords sorted by Wechat monthly index#I color marked transactional keywords in green and informational keywords in blue (if the search intent is mixed#it would be green for transactional).#The most important takeaway for every B2C sales strategy is#that Wechat is the most impirtant channel#followed by Taobao / Tmall and then Baidu Search.

0 notes

Text

Disruption Starts with Unhappy Customers, Not Technology

New Post has been published on https://personalcoachingcenter.com/disruption-starts-with-unhappy-customers-not-technology/

Disruption Starts with Unhappy Customers, Not Technology

Luis Diaz Devesa/Getty Images

For eight years I’ve visited leading companies in more than 20 industries around the world that claimed to be in the process of being disrupted. Each time, I’d ask the executives of these incumbent companies the same question: “What is disrupting your business?” No matter who I talked to, I would always get one of two answers: “Technology X is disrupting our business” or “Startup Y is disrupting our business.” But my latest research and analysis reveals flaws in that thinking. It is customers who are driving the disruption.

In the common scenario that executives think technology is trying to disrupt their business, they try to find a way to develop that technology internally or buy it from others. Major auto companies like GM and Ford are a good example: they have spent billions to buy and then build electric and autonomous driving technologies.

If the disruption threat is coming from a startup, then the incumbent often tries to acquire it — if the valuation is low enough. They can also try to compete with the startup on price, as a means to block their advance. In most cases I have seen, neither of these responses worked as intended.

For an example of the acquisition route, consider Yahoo. It was once the leader in the nascent search engine space, but lost the top position to Google and then lost the second position to Microsoft’s Bing. In response, then CEO Marissa Mayer went on a shopping spree to acquire technologies and startups in an attempt to regain the crown. As of 2016, Mayer had acquired 53 tech startups, spending between $2.3 and $2.8 billion, and countless hours of her top executives’ time with M&A due diligence. Yahoo eventually shut down 33 of these start-ups, discontinued the products of 11 start-ups, and left five to their own devices, failing to assimilate them. In all, Yahoo only fully integrated two of these companies: Tumblr and BrightRoll. In 2017, unable to grow, Yahoo was acquired by Verizon for $4.8 billion, a far cry from its peak valuation of $100 billion. (Verizon is now reportedly looking to sell Tumblr.)

What these companies seem to have missed is that the most common and pervasive pattern of disruption is driven by customers. They are the ones behind the decisions to adopt or reject new technologies or new products. When large companies decide to focus on changing customer needs and wants, they end up responding more effectively to digital disruption.

My analysis has grown from visiting or talking to executives of established companies and then having similar conversations with their challengers. In my book, Unlocking the Customer Value Chain, I talk about the incumbent-disruptor pairs in the list below. Based on the interviews and analyses of these industries I uncovered a common underlying pattern of customer-driven digital disruption. Disruptive startups enter markets not by stealing customers from incumbents, but by stealing a select few customer activities. And the activities disruptors choose to take away from incumbents are precisely the ones that customers are not satisfied with. Birchbox stole sampling of beauty products from Sephora. Trov stole turning insurance on and off from State Farm. PillPack stole fulfilling prescriptions from CVS.

Many of the standard ways of thinking about which new growth markets large conglomerate companies should enter revolves around the idea of “adjacencies” and “synergies,” at the firm-side. For instance, by manufacturing motorcycles and lawnmowers, two seemingly unrelated categories, Honda has gained production synergies that allowed it to become better and more cost-effective in both markets.

But if customers are at the center of disruption, companies need to understand how to offer customer-side synergies. Successful growth is dictated by benefits accrued to the customer, not to the company. After all, it is they who choose whether to adopt or acquire your new products or not. This is where a coupling strategy comes into play — it’s the concept of creating new products that create meaningful synergies with your original product. In other words, it makes it cheaper, easier or faster for customers to fulfill their needs as compared to using two products from different companies. One of the clearest ways to couple is to launch new products or services that are immediately adjacent to (i.e., occur before or after) the activities that consumers already undertake with the business.

Airbnb is an example. It started in the hospitality and travel industry by offering home-sharing. After considerable growth with the original offering, it moved into offering its users an online discussion forum and planning tool for travel—an activity travelers often perform before booking an Airbnb home—and then it moved into offering local leisure experiences for guests during their Airbnb stays. According to Brian Chesky, one of Airbnb’s founders, the goal is to eventually cover all the key stages of the customer value chain (CVC).

Alibaba’s customer side focus

Alibaba offers an excellent example of this type of customer-focused growth. By 2018, the company had become one of the world’s largest by market capitalization, with more than ten multibillion-dollar businesses in wide ranging sectors such as retailing, ecommerce, online cloud services, mobile phones, logistics, payments, content, and more. Between 2011 and 2016, the company’s revenues grew at an average compound annual rate of 87%. Profits jumped by 94% and cash flow by 120%. Such rapid growth was quite unique for such a large and established digital company.

So how did Alibaba do it? Founded as an online business-to-business marketplace, in 2003 the company moved into consumer-to-consumer ecommerce and in 2004 built both Aliwangwang, a text message service, and Alipay, an online payments service. The next year, it went on to acquire Yahoo China in an effort to provide consumers with content and web services. In 2008, it launched TMall, a business-to-consumer online retailer, followed in 2009 by Alibaba Cloud Computing, a cloud storage company. Other new business launches proceeded in turn: a search engine company named eTao (2010), a start-up called Aliyin that created mobile operating systems (2011), and a logistics consortium named Cainiao (2013). In 2015, Alibaba took a majority stake in smartphone maker Meizu. Note how many of these companies operated in non-adjacent industries. The synergies between retailing, cloud computing, payments, and electronics manufacturing are not immediately clear. Businesses in these industries require different resources and employees with widely varying skillsets in order to compete. So why didn’t the company stick with its original, business-to-business online marketplace and focus growth there in order to dominate the market and achieve competitive advantage by traditional economies of scale?

Alibaba’s expansion strategy focused squarely on customer-side synergies and CVC adjacencies. In 2016, around 50% of online shopping took place via mobile phones, with the rest occurring on laptops, desktops, and tablets. To shop online, consumers first had to decide which device to use to access the internet, and implicitly, which operating system and browser combination. After that, most consumers opened browsers and pointed at websites, accessing their communication services, email, social networks, chat apps, and so on. At some point, they identified a need to make a purchase and performed searches either outside ecommerce websites (for instance, on Google or Baidu) or inside them. From there, consumers arrived at the most appropriate ecommerce sites. In China, business customers went to Alibaba, while consumers went to Taobao to shop for products from other consumers or to Tmall to shop products from retailers.

To obtain more product information or to negotiate prices (a common practice in China), buyers communicated with sellers, usually by chat apps. Consumers then had to pay for their purchase and wait for a logistics operator to deliver it. This represented the extent of the typical online shopper’s CVC. Analyzing this CVC, we spot a clear pattern. Alibaba began growing by focusing on a single stage of the shopper’s CVC with its Alibaba website. It then moved outwards to capture other customer activities. Instead of using the traditional industry adjacencies approach (payment, mobile phones, and logistics are not adjacent industries), the company opted to move into adjacent CVC activities. By 2018, the company’s businesses were serving most of the CVC activities. Alibaba didn’t immediately pursue firm-side synergies. Its real win lay in achieving customer-side synergies. That, in turn, convinced its customers to couple.

The main hurdle of pursuing the coupling strategy is that this may lead your company into vastly different businesses that require vastly different people, skills, and capabilities than the ones your company possesses. In the case of Alibaba, it went from ecommerce to financial services, to search tools, to logistics, to hardware and to software. There is very little firm-side synergy in these businesses.

When I present coupling as a growth strategy to my clients, I warn them of this hurdle and ask them to fill out a table of the skills they think will be required to succeed in a new adjacent activity, whether they have that skill and, if not, how they plan on obtaining those skills. This exercise is simple, but essential. I ask them to list up to four activities they want the company to accomplish. Then, they list the required skills and their available skills. Finally, to get the skills they don’t have, do they need to build, borrow, or buy? So, borrow it from others via partnerships or buy it through acquisitions or recruitment? What they cannot do is disregard the need to bridge those skills gap.

Many established companies ‘pigeonhole’ themselves too narrowly in a specific industry. As a consequence, their area for exploring new growth is limited, not by their potential or their capabilities, but by arbitrary industry definitions. The fastest way to grow is to offer something that your current customers, those most loyal to you, would gladly pay for if you provided it and that, by virtue of them acquiring this new offering, it would make your original product or service even more valuable to them. And here is the catch: the new products that are launched do not need to be better than those of the established companies to be successful. As long as new products have synergies for the customer, they will likely get adopted.

Disruption is a customer-driven phenomenon. New technologies come and go. The ones that stick around are those the consumers choose to adopt. Many of the fast-growing startups such as Uber, Airbnb, Slack, Pinterest, and Lyft don’t have access to more or better innovative technologies than the incumbents in their respective industries. What they do have is an ability to build and deliver faster and more accurately exactly what customers want. This is causing the change-of-hands of sizable amounts of market share is relatively short periods of time. That is the basis of modern disruption in a nutshell.

Go To Source

#coaching#coaching business#coaching group#coaching life#coaching life style#coaching on line#coaching performance#Coaching Tips#Coaching from around the web

0 notes

Link

How does Social Media Marketing (SMM) work in China?

Social Media Marketing (SMM) is the set of technical tools to promote your website on main Social Media platforms.

The landscape of social platforms in China is totally different from the rest of the world. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Youtube, among others, are all blocked in China.

The main social media channels in China nowadays are :

- Wechat (equivalent of Facebook ,Whatapp, Instagram and e-bay)

- Sina Weibo (equivalent of Twitter)

- Youku (equivalent of Youtube)

Among them all, WeChat Marketing, Sina Weibo Marketing, QQ Marketing are seen as the Top 3 most effective promotion methods for local and oversea businesses.

How can Social Media Marketing (SMM) help promoting your website in China?

Take WeChat as example. On WeChat, companies are able to create “WeChat Official Accounts” to connect with their followers, promoting their brand or service. Businesses can also set up “WeChat Shop” to sell their products directly to WeChat users and get paid timely and safely by WeChat Pay. In short, Social Media Marketing (SMM) in China allows an active engagement with followers and eventually a good chance of conversion as new client.

In order to deliver, most important for us is to understand your objectives.

From there, we will propose a strategy to promote you in China and the best digital marketing tools in China to achieve your goals.

We have specialists in:

*China localization

*China SEO, including Baidu SEO, Qihoo 360 SEO and link building in China

*China SEM on all Chinese Search Engine like Baidu PPC, Sogou PPC or Qihoo 360 PPC

*China e-commerce on WeiDian, TaoBao, TMall vip.com, mei.com and payment methods in China

*Chihna Social media marketing on Wechat, Sina Weibo, QQ , Youku and many more

0 notes

Text

How to get started with Digital Marketing in China

How to start planning your Chinese marketing strategy

China: it's the market everyone wants a piece of. With over 1.5 billion people, your target market is here, even if you aren’t. But, entering the market doesn’t make it just start raining money.

Download our Bussiness Member Resource – China Digital Marketing Strategy Guide

Our China Marketing Strategy Guide is a complete guide to help you understand China’s digital marketing landscape. This guide will give you a better understanding of China’s biggest online marketing channels and how they operate.

Access the China digital marketing strategy guide

Chinese consumers are bombarded by businesses that want them, both homegrown and foreign. For your business to get a piece of the pie, you need to come in with a well thought out, meticulously researched plan.

No one is saying it's easy. But any demographics report will tell you how much your bottom line could benefit.

These 8 tips will get you heading in the right direction and ready for marketing to a Chinese audience.

Do Your Research:

The analytics tools at your disposal in this market are the things you could only dream of in the rest of the world. Want a cross section of any brand's TMall/Taobao search volume, customer spending, location, etc, etc., etc.? You can have it with a personal account. You can even share what you find on social media platforms. Imagine your ability to strategize with the options for businesses.

Plus, if your target market shops on marketplaces like TMall and JD.com, why take the time to develop an eCommerce app? Focus your efforts and optimize your store there instead.

Use the information available about hobbies, spending level, and geographic location to understand your shoppers and craft brand stories that will entertain and engage them. That’s how your company will come out ahead of other entrants.

Dior consumers’ age & gender on TMall/Taobao: 2011-2015

Be Mobile

Mobile use in China, particularly in terms of eCommerce and social media, makes a lot of other markets look like they're trapped in the 1990's.

Double 11, the major e-shopping holiday in the country, did over US $9 billion GMV in 24 hours. Over 40% of that was mobile.

WeChat, the major player in the social scene, had 600 million active accounts in Q2 2015. 25% of those people check the app over 30 times a day. (source) Even in B2B, the app’s penetration rate (north of 95%) makes it an easy way to do repeat sales and CRM.

In short, if you're not mobile-friendly or ready to jump into the wide world of WeChat, make it a priority.

A screenshot of the Starbucks Official WeChat page, where they take advantage of the built-in pinned menu options, which can support multiple languages.

Baidu is not Google. WeChat is not Whatsapp.

It's a mistake to try and think of these platforms as "the Chinese Twitter/Facebook/Instagram/Whatsapp" or "the Chinese Google". Perhaps at one point it was true, but now they have come into their own.

WeChat is a messaging platform that is completely private. If you see a photo or video shared by a friend and comment, only people friends with both of you will see that interaction. Everyone else sees just the photo. For businesses, official accounts can send out photos, articles, videos, games, audio messages, and chat with followers--all through a private conversation with each person. Businesses can also accept payment and do customer service directly through the app.

With Baidu, SEO is a completely different beast. The way the first page is structured is so unnatural that a heat map of will show users habitually clicking next page to find organically high-ranking content. What shows up instead? Baidu Answers, Baidu Baike (an encyclopedia), Baidu Shopping, paid ads, etc. Very un-Google.

A screenshot of Baidu, highlighting the Brand Zone. Both the top results and the right sidebar are in the zone

Email is dead. Long live video.

While we're at it, apps are dead too. Long live stories.

The only kind of companies that see any kind of open rate for email campaigns are B2B, and even then it is far lower than what you get elsewhere. And Chinese users don't often download a company-specific app, especially if that company can be found on TMall or WeChat. You have to find new ways to engage.

Chinese consumers want content-driven campaigns. Baidu wants content-driven search. When you come to China, expect to devote resources not just to translating what you have, but creating new content with extra emphasis on your company's story. Spend time crafting a story that sets you apart and expressing it both verbally and visually.

Video is the new king. Everywhere from WeChat to TMall, pages with video are not only getting more clicks, they get more conversions. Why? The story drives brand recognition which helps page viewers engage the first time they see it and remember the next time they get to a product search engine like TMall.

Screenshot of a video on a Tmall Global store selling baby formula

Learn to swing the B.A.T.

It stands for Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent--the big three. And it also has a lot to with with why apps are dead. Each of those companies has a widely used app and in some cases, an app store, with Baidu's being the biggest. None list the apps of the others in their stores, which means most mobile users have more than one app store downloaded. Second, Baidu doesn't index WeChat content or Alibaba shopping results. Third, WeChat (the app that's always had a built-in QR scanner) won't scan Alibaba QR codes (or vice versa).

They don't interact with each other, but consumers interact with them all, which means you have to too.

In order to successfully market in this environment, you have to get content on all three and manage them all independently. It also includes their different payment methods.

The Alibaba QR code from the Starbucks TMall homepage

Don't be afraid to take things offline

We are all digital marketers, but the O2O sector in China is growing. In services, travel in particular, it's an obvious solution. Buy online, claim later. Other services, like B2B service providers, event managers, and educational professionals can implement similar systems and reap the rewards of creating convenience for their clients.

As a digital marketer, think of this option as an extension of your social media presence. Because, on WeChat, it is. There is no difference for your followers between the account that advertises the deal, the account they pay, and the account that shares the event photos afterwards.

You can use the same ideas on a standard eCommmerce site, like censh.com. They offer real-time chat with employees, categorized by store.

Communicate

We've talked about the need to create content to drive your marketing in China. This tip is a little different, but not following it will definitely cost you sales.

Make sure you have a team available to chat with customers. Contact forms? You'll get almost no responses. Chat buttons and callback systems? Customers will call and chat, asking questions sometimes for 20 minutes or more before committing to a purchase. Your customer care team is the difference between them buying and walking away. It's vital.

Not as vital, but still important, are KOL's. They're often frowned upon, if not downright abandoned, by a lot of marketers outside this country. In China, they matter. Take uber-famous actress Fan Bing Bing. According to Ad Age, at one point Xinhua news estimated she had over 50 endorsement deals. With numbers that high, she has to be making a difference for the brands she represents.

The homepage of L'Oreal's TMall store, September 2015

Get help if you need it

There's a reason people spend their lives studying and working in China. It's got a steep learning curve and success requires a depth and breadth of knowledge that is unparalleled in other global regions.

If your company doesn't have the capabilities to research, understand, plan, and execute a marketing strategy in China, get help. Not just with finding the numbers, often in tools that only have a Mandarin language UI, but with converting them into coherent strategies.

Let’s go through an in-depth strategic example. Every year, online sales drop across industries in February because of Chinese New Year, when people return home and see their families. Gifts aren’t a typical part of this tradition, with the exception of hongbao, red envelopes filled with cash. So, it isn’t an ideal month to open a store. It may, however, be a good time to try and capitalize on the electronic hongbao trend and WeChat usage by offering electronic gift cards you can get through an in-app game or a lottery. That’s what Tencent and Alibaba did this year.

Thanks to Cyril Drouin for sharing his advice and opinions in this post. Cyril is CEO & Senior eCommerce Consultant of BysoftChina You can follow them on Twitter or connect on LinkedIn.

from Blog – Smart Insights http://www.smartinsights.com/digital-marketing-around-the-world/how-to-get-started-with-digital-marketing-in-china/

0 notes

Text

Online Marketing for Yoga Equipment in China - Baidu Search or Tmall & WeChat?

🇨🇳 #ecommerce #socialmedia #search #SEO

Maybe some of you remember that I asked in summer for some B2C topics, that you thought one might be better off focusing on Ecommerce platforms and Social Media in China than on organic & paid Search (= SEO & SEA)?

Well, I have been a little busy - so I couldn't follow up in time.

But I finally did look at some numbers. Spoiler Moonie Zhu - you were right: There is so much more to gain on E-commerce platforms and Social Media in (for this) B2C topic.

But there is also a little twist to this story - in the end.

Let me summarize the numbers for you:

I looked at around 3,300 keywords from the Yoga industry.

I gathered them using some different tools (including Searchmetrics of course - but some others as well) plus some input from my friends Jademond Digital.

For you to better understand them, I auto-translated them using Google Translate (you'll see that in one column in the screenshots).

For those Chinese keywords I got the Baidu Search Volume from Baidu Keyword Planner, the monthly searches of China's biggest ecommerce platform Taobao / Tmall and the monthly Wechat Index numbers to cover the most important Chinese Social Media app. I could have surely added some more values like those of other ecommerce platforms and further Social Media channels - but I think for this quick view, that should be enough.

In the first three screenshots you can see the top keywords by Search Volume (for Wechat the Monthly Index) in descending order for those three platforms.

I color marked transactional keywords in green and informational keywords in blue (if the search intent is mixed, it would be green for transactional).

The most important takeaway for every B2C sales strategy is, that Wechat is the most impirtant channel, followed by Taobao / Tmall and then Baidu Search.

- Wechat: 120 Million

- Taobao/Tmall: 34 Million

- Baidu Search: 319 Thousand

So definitely any company wanting to sell Yoga equipment like Yoga Mats, Yoga Leggins, Yoga Balls, ... should get on WeChat for reach (and maybe open a Wechat store as well) and onto the ecommerce platforms for sales.

But does that mean, that Organic Search on traditional search platforms like Baidu Search should be neglected?

Well, I looked at some further numbers:

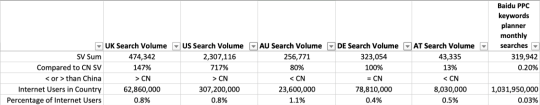

I (auto)translated the same 3.3K keywords into English and into German.

I checked the Google Search Volumes for (English) for US, UK and Australia.

I checked the Google Search Volumes for (German) for Germany and Austria.

Given that apart from Social Media and Ecommerce (Amazon, Ebay,...) Google Search is still an important channel for B2C companies in the west, I figured it might be worth comparing the Chinese search numbers to those western search numbers.

Without having confirmed with any Yoga supplies trader in the west, I do believe, that SEO / organic search traffic is one important traffic channel for many to sell their goods (if you work for such a company - please comment below, if I am right or totally off track).

Here are my findings (last screenshot):

in UK there are 47% more people searching for Yoga topics on Google than in China on Baidu

in US there are 617% more people searching for Yoga topics on Google than in China on Baidu

in Australia there are 20% less people searching for Yoga topics on Google than in China on Baidu

in Germany it is about the same amount of people searching for Yoga topics on Google like in China on Baidu

in Austria there are 87% less people searching for Yoga topics on Google than in China on Baidu

While most of these numbers show, that there is so much more demand on traditional search in the West compared to China, we can also see that in Germany the amount of people is even the same as in China. Sure, in China there are massivly more people living than in Germany, which makes the people searching on Baidu for Yoga just 0.03% of the population, while in Germany it is 0.4% of the population. But still there are traders selling Yoga equipment to people in Germany and earning quite some good money from that.

Now - my take on this:

YES, it definitely makes a lot of sense to focus on Social Media and Ecommere platforms first, when trying to sell Yoga equipment in China.

But leaving the sales potential of Germany untouched in China, because not paying attention to Baidu SEO and Baidu PPC, is something I would like to reconsider. Sure, the percentages of the revenue on Tmall might be much higher - but the money one can earn through an own ecommerce platform (or through redirecting visitors from the website to Tmall) in the same amount one could reach in Germany (and more than one could reach in Australia and Austria) would make this strategy worth for me trying as well.

Now many people might want to say, that much search volume for Baidu / Google search lies in informational search queries. While this might be true - to me as a full time SEO consultant, helping with SEO strategies for many Google-SEO and some Baidu-SEO clients, it is important to not only target those transactional keywords that lead to a sale right away. It is even more important to build a holistic search strategy for exposing the Brand to as many people as possible - to help a brand becoming an important brand in the heads of the people, to attract people to visiting the website, understanding the brands philosophy, learning new stuff, facts and tips and tricks from you as a brand, for them to remember who made them know more about their favourite topic. So hell yeah - it does make sense to produce a traditional Yoga guide with nice imagery, videos, ... (could all be reused for Social Media) do a Beer Yoga special (maybe not trendy and strange enough for becoming viral - but maybe Baby Yoga? StarWars Yoga? Space Yoga? Qigong Yoga combination? ...).

Looking forward to your take.

Cover Image Credit: Dall-E Mini

0 notes

Text

Disruption Starts with Unhappy Customers, Not Technology

New Post has been published on http://personalcoachingcenter.com/disruption-starts-with-unhappy-customers-not-technology/

Disruption Starts with Unhappy Customers, Not Technology

Luis Diaz Devesa/Getty Images

For eight years I’ve visited leading companies in more than 20 industries around the world that claimed to be in the process of being disrupted. Each time, I’d ask the executives of these incumbent companies the same question: “What is disrupting your business?” No matter who I talked to, I would always get one of two answers: “Technology X is disrupting our business” or “Startup Y is disrupting our business.” But my latest research and analysis reveals flaws in that thinking. It is customers who are driving the disruption.

In the common scenario that executives think technology is trying to disrupt their business, they try to find a way to develop that technology internally or buy it from others. Major auto companies like GM and Ford are a good example: they have spent billions to buy and then build electric and autonomous driving technologies.

If the disruption threat is coming from a startup, then the incumbent often tries to acquire it — if the valuation is low enough. They can also try to compete with the startup on price, as a means to block their advance. In most cases I have seen, neither of these responses worked as intended.

For an example of the acquisition route, consider Yahoo. It was once the leader in the nascent search engine space, but lost the top position to Google and then lost the second position to Microsoft’s Bing. In response, then CEO Marissa Mayer went on a shopping spree to acquire technologies and startups in an attempt to regain the crown. As of 2016, Mayer had acquired 53 tech startups, spending between $2.3 and $2.8 billion, and countless hours of her top executives’ time with M&A due diligence. Yahoo eventually shut down 33 of these start-ups, discontinued the products of 11 start-ups, and left five to their own devices, failing to assimilate them. In all, Yahoo only fully integrated two of these companies: Tumblr and BrightRoll. In 2017, unable to grow, Yahoo was acquired by Verizon for $4.8 billion, a far cry from its peak valuation of $100 billion. (Verizon is now reportedly looking to sell Tumblr.)

What these companies seem to have missed is that the most common and pervasive pattern of disruption is driven by customers. They are the ones behind the decisions to adopt or reject new technologies or new products. When large companies decide to focus on changing customer needs and wants, they end up responding more effectively to digital disruption.

My analysis has grown from visiting or talking to executives of established companies and then having similar conversations with their challengers. In my book, Unlocking the Customer Value Chain, I talk about the incumbent-disruptor pairs in the list below. Based on the interviews and analyses of these industries I uncovered a common underlying pattern of customer-driven digital disruption. Disruptive startups enter markets not by stealing customers from incumbents, but by stealing a select few customer activities. And the activities disruptors choose to take away from incumbents are precisely the ones that customers are not satisfied with. Birchbox stole sampling of beauty products from Sephora. Trov stole turning insurance on and off from State Farm. PillPack stole fulfilling prescriptions from CVS.

Many of the standard ways of thinking about which new growth markets large conglomerate companies should enter revolves around the idea of “adjacencies” and “synergies,” at the firm-side. For instance, by manufacturing motorcycles and lawnmowers, two seemingly unrelated categories, Honda has gained production synergies that allowed it to become better and more cost-effective in both markets.

But if customers are at the center of disruption, companies need to understand how to offer customer-side synergies. Successful growth is dictated by benefits accrued to the customer, not to the company. After all, it is they who choose whether to adopt or acquire your new products or not. This is where a coupling strategy comes into play — it’s the concept of creating new products that create meaningful synergies with your original product. In other words, it makes it cheaper, easier or faster for customers to fulfill their needs as compared to using two products from different companies. One of the clearest ways to couple is to launch new products or services that are immediately adjacent to (i.e., occur before or after) the activities that consumers already undertake with the business.

Airbnb is an example. It started in the hospitality and travel industry by offering home-sharing. After considerable growth with the original offering, it moved into offering its users an online discussion forum and planning tool for travel—an activity travelers often perform before booking an Airbnb home—and then it moved into offering local leisure experiences for guests during their Airbnb stays. According to Brian Chesky, one of Airbnb’s founders, the goal is to eventually cover all the key stages of the customer value chain (CVC).

Alibaba’s customer side focus

Alibaba offers an excellent example of this type of customer-focused growth. By 2018, the company had become one of the world’s largest by market capitalization, with more than ten multibillion-dollar businesses in wide ranging sectors such as retailing, ecommerce, online cloud services, mobile phones, logistics, payments, content, and more. Between 2011 and 2016, the company’s revenues grew at an average compound annual rate of 87%. Profits jumped by 94% and cash flow by 120%. Such rapid growth was quite unique for such a large and established digital company.

So how did Alibaba do it? Founded as an online business-to-business marketplace, in 2003 the company moved into consumer-to-consumer ecommerce and in 2004 built both Aliwangwang, a text message service, and Alipay, an online payments service. The next year, it went on to acquire Yahoo China in an effort to provide consumers with content and web services. In 2008, it launched TMall, a business-to-consumer online retailer, followed in 2009 by Alibaba Cloud Computing, a cloud storage company. Other new business launches proceeded in turn: a search engine company named eTao (2010), a start-up called Aliyin that created mobile operating systems (2011), and a logistics consortium named Cainiao (2013). In 2015, Alibaba took a majority stake in smartphone maker Meizu. Note how many of these companies operated in non-adjacent industries. The synergies between retailing, cloud computing, payments, and electronics manufacturing are not immediately clear. Businesses in these industries require different resources and employees with widely varying skillsets in order to compete. So why didn’t the company stick with its original, business-to-business online marketplace and focus growth there in order to dominate the market and achieve competitive advantage by traditional economies of scale?

Alibaba’s expansion strategy focused squarely on customer-side synergies and CVC adjacencies. In 2016, around 50% of online shopping took place via mobile phones, with the rest occurring on laptops, desktops, and tablets. To shop online, consumers first had to decide which device to use to access the internet, and implicitly, which operating system and browser combination. After that, most consumers opened browsers and pointed at websites, accessing their communication services, email, social networks, chat apps, and so on. At some point, they identified a need to make a purchase and performed searches either outside ecommerce websites (for instance, on Google or Baidu) or inside them. From there, consumers arrived at the most appropriate ecommerce sites. In China, business customers went to Alibaba, while consumers went to Taobao to shop for products from other consumers or to Tmall to shop products from retailers.

To obtain more product information or to negotiate prices (a common practice in China), buyers communicated with sellers, usually by chat apps. Consumers then had to pay for their purchase and wait for a logistics operator to deliver it. This represented the extent of the typical online shopper’s CVC. Analyzing this CVC, we spot a clear pattern. Alibaba began growing by focusing on a single stage of the shopper’s CVC with its Alibaba website. It then moved outwards to capture other customer activities. Instead of using the traditional industry adjacencies approach (payment, mobile phones, and logistics are not adjacent industries), the company opted to move into adjacent CVC activities. By 2018, the company’s businesses were serving most of the CVC activities. Alibaba didn’t immediately pursue firm-side synergies. Its real win lay in achieving customer-side synergies. That, in turn, convinced its customers to couple.

The main hurdle of pursuing the coupling strategy is that this may lead your company into vastly different businesses that require vastly different people, skills, and capabilities than the ones your company possesses. In the case of Alibaba, it went from ecommerce to financial services, to search tools, to logistics, to hardware and to software. There is very little firm-side synergy in these businesses.

When I present coupling as a growth strategy to my clients, I warn them of this hurdle and ask them to fill out a table of the skills they think will be required to succeed in a new adjacent activity, whether they have that skill and, if not, how they plan on obtaining those skills. This exercise is simple, but essential. I ask them to list up to four activities they want the company to accomplish. Then, they list the required skills and their available skills. Finally, to get the skills they don’t have, do they need to build, borrow, or buy? So, borrow it from others via partnerships or buy it through acquisitions or recruitment? What they cannot do is disregard the need to bridge those skills gap.

Many established companies ‘pigeonhole’ themselves too narrowly in a specific industry. As a consequence, their area for exploring new growth is limited, not by their potential or their capabilities, but by arbitrary industry definitions. The fastest way to grow is to offer something that your current customers, those most loyal to you, would gladly pay for if you provided it and that, by virtue of them acquiring this new offering, it would make your original product or service even more valuable to them. And here is the catch: the new products that are launched do not need to be better than those of the established companies to be successful. As long as new products have synergies for the customer, they will likely get adopted.

Disruption is a customer-driven phenomenon. New technologies come and go. The ones that stick around are those the consumers choose to adopt. Many of the fast-growing startups such as Uber, Airbnb, Slack, Pinterest, and Lyft don’t have access to more or better innovative technologies than the incumbents in their respective industries. What they do have is an ability to build and deliver faster and more accurately exactly what customers want. This is causing the change-of-hands of sizable amounts of market share is relatively short periods of time. That is the basis of modern disruption in a nutshell.

Go To Source

#coaching#coaching business#coaching group#coaching life#coaching life style#coaching on line#coaching performance#Coaching Tips#Coaching from around the web

0 notes