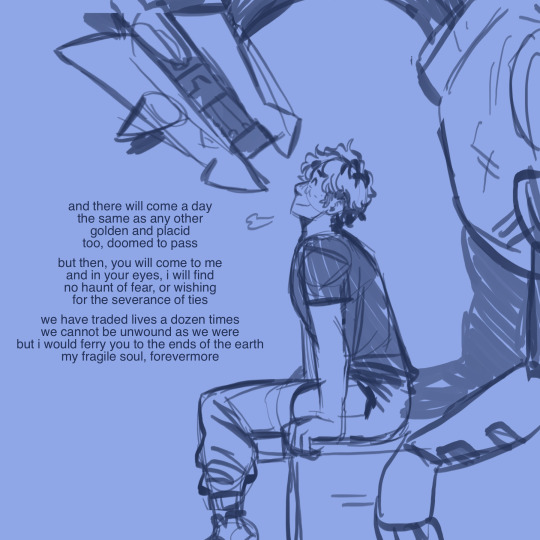

#forgive me the poetry i like being melodramatic on occasion

Text

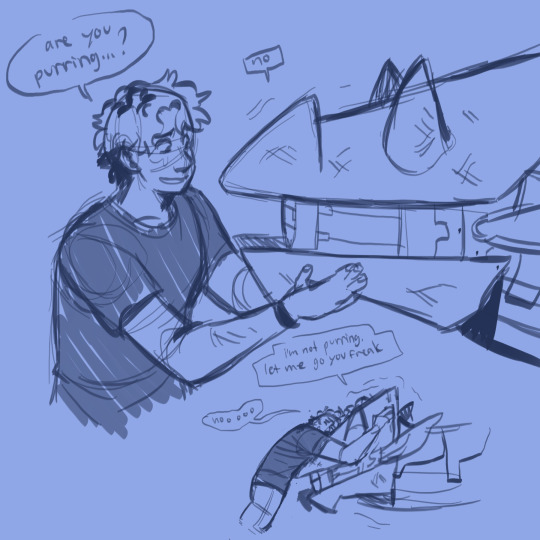

zarthur dump

#forgive me the poetry i like being melodramatic on occasion#ftr for any newbies this isnt ship necessarily theyre just weird and codependent#steelheart redux#my art#my ocs#arthur steele#zarian#i feel like ive gotten worse at drawing zarian head-on. i need to finish my current model

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Baby Does Me: Chapter 33

POV: John Deacon x reader

Notes: Still aiming for once a week updates, could be more, will never be less; thanks for sticking around; I love this story and everyone who reads it dearly and with all my heart.

Warnings: so much smut so much smut; Platonic Forms?

Abstract: Young is the night it feels so right now that you’re mine...

-------------------------------------------

Everything was black and white.

He was surrounded.

It was the apotheosis of fainting. Some unification he couldn’t yet describe, yet intuitively knew like the beat of every song he had ever written; his music had been screwed out of his heart as a bloody pulp and smashed on each page, all pomegranate seeds and peach pits; his art, and hers were works of color and intense emoting. And that was part of it, art was intricately part of this feeling, of this experience; because being with her was being with a walking piece of art.

It was, because he knew things like this, the Stendhal syndrome.

Roger had taken off his sepia-toned glasses. They were round and almost delicate in a spindly way that did much to betray the inner workings of the man who wore them. Flashy on the outside cotton-candy frail on the inside. Much like the candy confection, his moods were transient yet shockingly robust; they’d pierce you in the heart and evaporate after doing so, like some joke only he knew the punchline to, which is exactly how he liked it. This, however, did not mean his feelings were impermanent or purely esoteric; Roger preferred a full-bodied expression of his feelings at all times. For him, feelings were something you could touch and should touch. And he sensed the woman across from him, more or less, had the exact same emotional profile. Her profile was fine, fine, fine.

Deacy always loved those particular sunglasses; he had told Roger on many occasions they were his “film school” glasses, because they made everything appear like an old movie from the 1930s or that odd time in the 1970s when everything was a nostalgic throwback in color tones. It always came back to color. Of all of Roger’s pairs, those sepia ones were Deacy’s singular mission and desire to steal the most frequently. Roger was very protective of his collection, and no matter how many pairs of sepia-colored sunglasses Roger bought for Deacy, the bassist always only wanted Rog’s personal pair. This was, as everything else had been for them, some unspoken, spoken game. Though at this time, the men had no idea they were both slowly engaging in the same game, near the same time, with women with whom they were both falling in love. These decisions are barely noticed or noted, and yet they happen everyday. Rock stars are no exception to this rule.

With the glasses now removed, Roger could see Lydia’s paintings in full force. All harsh lines, cutting and uneven, and deeply felt, as if necessary. It was as if she had sliced her arm open and painted with her own black blood, as if she had smeared her very life on the canvas. Her fingerprints covered every line, even though she never used such techniques. Despite this critical distance, every line and impression spoke of some Truth, some mixed emotion, some passionate distraction, a powerful act of consolation.

They gave him pause. Piece after piece. Parts of her, all of her. He froze, for a moment. It had only been a moment. But it always is just merely a moment. We romanticize it in our own minds, making some trivial seconds into an expanse of time that shook us for eons. When in reality the moments when love happens are brief, singular, and yet universal. Another paradox; Deacy would be pleased. To each person who is having them, it could be about anything, and yet the feeling always equals the same emotion. It could be over coffee, the passing of a note, a whisper, a laugh, a glance; bringing her something that was lost, fixing something that was broken; the mundane, the easy, the forgettable, yet entirely and always recalled in flowery prose and undying poems. Shakespeare wrote sonnets for a reason, folks.

So, to Roger, a closeted romantic, and he certainly thought of himself as a new-aged Shakespeare, this moment in space-time did something to his heart he couldn’t entirely understand at this time, which was saying something since he had the emotional intelligence and sophistication of an FBI agent performing opera. All cosmic depth and precision of intention. What did he remember the most? The art--her art? The use of color and light to create depth where there was none, or should be none? Or was it her? Her torn red dress, his rainbow blazer, her golden hair. When exactly did they become one, those ideas? Inextricably tied together, black and white and her, all color and light? Well, it was our friend Stendhal. Cocky asshat, Roger thought. Roger had never met Stendhal, separated as they were by time and space, yet that jerk was right. Roger hated it when other people were right; on all occasions, he preferred to be the right one. Though, Lydia was right. She was right. She had probably always been right. He just hadn’t met her yet. But maybe he had always known anyway.

Distracted as he was by the art and the beautiful woman in front of him, he still managed to close the door by leaning on it, suggestively. Though, everything with Roger Taylor was suggestive. The moment in question happened during this small gesture. The closing of a door. And we’d all like to think he was leaning up against it as a seduction, a keen way to put the moves on the unacknowledged, unrealized love of his life. We’d all like to think Roger was that good, and that invincible in the face of ineffable beauty.

He wasn’t.

Lydia hadn’t noticed, she had chosen that moment to close her eyes, to swipe her hair back, to turn her neck, and gaze off, performing her own quiet seduction while he should have been performing his. She had ever been his match, you see.

In reality, Roger had leaned up against the door, closing it on accident, because he had fainted. It had lasted for a handful of simple seconds, nothing long, nothing melodramatic, or even noticeable to anyone else but himself. He had fainted in the face of beauty. There was something shockingly Platonic about it, which was ironic considering Plato hated the arts and artists with a passion that held hands with an outright and violent jealousy. The way Roger saw it, if he had been Plato and his mentor (Socrates) had told him he could only study philosophy or poetry, not both, and was forced to pick philosophy, well, he’d hate the arts too. Despite Plato’s blatant envy, every Platonic Form working in this room swirled around Roger, intermingled, and he experienced a keen apotheosis with the Godhead; his life would never be the same again.

He fainted.

His too blue eyes rolled back, and he felt his vision blur into blackness, all color erased, all light evaporated: he held hands with some divine Form of the Arts and Love, and everything else fell away.

He fainted. Fuck Stendhal, he thought upon waking.

He fainted. Mere seconds, but he never escaped. His body lightly became suspended in action, leaning back without his power or will to control it. He had gone some other place. That elusive place of creation no artist can name. He had gone there, on a seventeen second journey. Part of him would always be there. Part of it would always be her.

He fainted. Eyes gone, mind some place else. His body folded into the door, casually, elegantly. He leaned. His back hit the door, and he swayed with it. They danced together until the door closed. His body followed the force of it, forward, then back.

He fainted. Maybe it was her, her beauty alone. Or her artworks, and their soul-swaddling beauty. Maybe it was both. Maybe it didn’t matter. Plato would know which it was, Roger thought. And Shakespeare would be capable with his numerous talents to put it into words, and Stendhal would be able to explain it him. He’d understand.

He fainted. Wrapped in the arms of Stendhal, Roger sunk bog-deep. It was an immovable free-fall. Another paradox.

But then, Roger woke up. He came too. And he saw her.

He saw Lydia.

He thought, besides a good fuck you to Stendhal, he could look at her forever, admire her, like work of art; everyday he’d notice something he hadn’t before that would only increase her beauty, which could never be diminished. Something in her was eternal. Roger waxed Platonic. Though nothing about his feelings for Lydia were remotely platonic.

He had fainted. Slipped away for a mere seventeen seconds. Come back from some journey. And he saw her.

That’s probably when he knew. When the first hint creeped up to say hi. He hadn’t listened, though. He pushed it back down, trying to deny what was there. And that denial, that split-second choice to ignore his heart and the existential beauty trip he had been on, that’s when Stendhal reared his ugly head again. He hadn’t noticed the second occurrence, because he had been distracted by her kiss.

It was easy to forgive such an indiscretion.

Kisses can be magic.

But so can Stendhal: that’s when the hallucinations started.

All the colors started vanishing, but he hadn’t noticed.

So, he slipped further down the rabbit hole; this he would regret later, but not now. Not with her tongue down his throat.

He had fainted, up against the door, then he came back. And he saw Lydia. She peered at him. Head turned to profile, eyes down, then flicked up to his.

Well, he couldn’t resist.

Could you?

They moved in syncopation. Him first, then she mirrored him. She didn’t notice his sluggish start. And he shook it off as ecstasy--he wasn’t entirely wrong. He didn’t notice the lack of color, because the entire room was black and white already. It is hard to blame him.

As their lips touched, and their tongues touched, he slid the blazer from her shoulders, and wrapped his arms around her. Her skin was silk. He never wanted to let go of her. Never wanted to let go of her. He never wanted to. He felt that. He meant it.

He pulled away from her kiss, and she clawed him back to her, cradling his face and blond hair simultaneously. He smiled, not wanting to pull away, but he couldn’t stop thinking about her neck; it was hard to blame him.

Roger kissed down her chin, and fondled her waistline, down to her plentiful, fantastically feminine hips. And proceeded to lick her neck in tantalizing swirls that sent shocks through her entire body. He traced down her cleavage with his tongue, interrupted by her bra. He flicked his sapphire eyes to her’s; asking permission with them. She laughed softly, bit her lip, and winked at him.

That was all he needed to hear. He knew. Well, he knew a lot. But these moments happen, and we pass them by in the moment, only to revisit them later and go: was that when? Was that moment when I first knew? Roger would be trapped in this cycle for a long time. Stendhal wouldn’t help this at all either. Maybe it had been the giggle? The wink? When she threw her head back and arched her back? It was hard to tell. Love looked different to different eyes. He intertwined a hand in hers, which she readily held back.

He unhooked her bra in one skilled motion, with one knowing hand. He slipped it off one arm, and they broke touch with their other hands to remove it completely. The break in touch lasted for a second. No more.

She sifted a hand to his black pants, and began slowly undoing the button, the zipper. Each movement an important step in seduction, each second a path to exquisite foreplay.

Roger began kissing Lydia again. He pinched one of her nipples hard, until she moaned in his mouth. He hastily traveled down her decolletage once more, carefully licking her other nipple. Then, he started biting. Softly at first, then hard. He moved to the tender skin around her nipple, and bit crescent moons around her breast in one elegant line. Each bite was harder than the last, and each level of intensity made her writhe and shine, and made him grow tumescent, surrounded by black and white masterpieces.

His black pants were off, and she moved to his white shirt, though concentration was growing more and more difficult with each passing bite, with each passing second. He moved a hand slowly down, and up underneath what remained of her dress. She was wet already when he felt her tenderly. He pulled back from her breast, and gazed into her eyes--only dark to him, for all color was gone, but he hadn’t noticed that sensation any more than he could pinpoint the exact second he knew he loved her.

He wanted to make love to her, to look her in the eyes as he gave her pleasure; he wanted a connection, he wanted intimacy, he wanted vulnerability. He was a stranger in a strange land. Where was that prick Plato when you needed him, he thought, fleetingly.

His fingers worked around her clit, and she pulled herself close to his white tee-shirt, clinging to him. She sighed in his ear, and the sound of her breath caused him such shocking ecstasy he couldn’t put it into words, let alone music. His other hand found her neck, her face, and he pulled her back, so he could look at her. This was surprisingly tender, not rough, yet not negotiable. He could easily please her, and only her, forever, and count himself a happy man.

Lydia put her hand on his, and they looked at each other, as he slowly massaged her. She deftly slipped a hand around his cock, and began tracing his length in rhythm with his movements.

Roger was startled at how close he could be with someone without being inside them. This was entirely new to him. Everything about this feeling, about this closeness, was entirely new. Was this love? Was this Stendhal?

It was both.

They still had half their clothes on, and yet he had never felt closer to anyone.

They were up against the door now, holding each other’s heads, sliding their hands skillfully to pleasure the other. And in every gesture, love was there. In every movement, care occupied a space.

Time escaped them, and it was hard to blame them.

--------------------------------

Tag List: @phantom-fangirl-stuff @triggeredpossum @obsessedwithrogertaylor @groupiie-love @partydulce @richiethotzierz @sophierobisonartfoundationblr @psychostarkid @teathymewithben @smittyjaws @just-ladyme @botinstqueen @mydogisthebest @little-welsh-wonder @maxjesty @deakysdiscos @yourealegendroger @marvellouspengwing @molethemollie @deakysgirl @arrowswithwifi @tardisgrump @mikey-sway

#john deacon x reader#joe mazzello#roger taylor#ben hardy#bohemian rhapsody#queen x reader#roger taylor x reader

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on Grasses of Remembrance (The Tale of Genji through its poetry)

Finally had some time this weekend to sit down with A Waka Anthology, Volume 2: Grasses of Remembrance Part B by Edwin A. Cranston. This book is the last in an impressive and intimidating collection translating a number of major classical poetry anthologies. It’s basically a speedrun through Tale of Genji (if such a thing were possible) filtered through all 795 waka poems written or uttered by the characters over the course of the novel.

Poetry was a Really Big Deal during the Heian era. If you were an aristocrat, not only were you expected to compose decent poetry, you had to be able to do it off-the-cuff appropriate to the occasion. AND to do this properly, you were expected to be able to recognize and respond cleverly to references to a ton of other existing classic poems from memory that people would just mention casually in conversation or writing (kinda like how people quote the Simpsons today lol). This was a prime marker of how intelligent/competent and - no joke - how sexy you were. So not surprisingly, these poems are extremely important to the development of character interactions and themes in the Tale of Genji which has a lot of romance and relationship plotlines.

However. Translating Heian era Japanese into modern Japanese is already challenging. Rendering Heian era Japanese waka poetry into modern English is, as you might imagine, harder for a bunch of reasons. Considering how dense the actual novel already is, it’s super easy to gloss over the poetry, and some modern translations simply integrate the basic intent of the poems right into the main text/dialogue.

I was really interested in finding something specifically focusing on and analyzing the poetry, and this book appeared to fit the bill.

Short review: IT TOTALLY DOES. If you’re into Tale of Genji, Heian era, classical Japanese history, classical Japanese literature, Japanese poetry, or just love reading translators articulating eloquently while sassing characters or flailing through linguistic complexities, I RECOMMEND THIS BOOK

Long review: blah blah blah thoughts follows, including some quotes/poem for reference.

The book starts with a quick 2 page intro setting the context of the Tale of Genji, then goes straight into the poems. TBH I personally found it more flowery and redundant than necessary (it repeats a few poems that are then explained later). But it’s only 2 pages, we’ll live.

Then, the poems. For every poem (or poems, in the case of an exchange - sometimes a flurry of them with multiple characters speaking or dashing letters off to each other) there’s an intro and summary of context followed by an analysis, including notes on meaning, narrator and character intent, structure, symbols and wordplay. The original Japanese is included in romaji alongside the English translation. The commentary also flags known references to other classic poems (WITH those poems in-line! This is awesome because I don’t have the rest of these books!), and even mentions poem and folk song quotations from the rest of the novel where the characters have not composed new poetry, but are reciting other existing known pieces.

Overall, I have only three real “warnings” about Grasses of Remembrance Vol 2b:

1) It’s very academic and flowery in tone. If you’re not used to it, it can be hard to read. But then again, if you’re not willing to get past that, how are you reading Tale of Genji? lol. In any case, I personally thought the commentary was a lot of fun. Cranston definitely has opinions and can get pretty sarcastic in places, which I found hilarious. Here are a few sample quotes:

“Tamakazura has remarked to herself how superior the Emperor [Reizei] was in looks to all the courtiers in his train (It is a principle with this author that superior people be dashingly handsome or ravishingly beautiful).”

“The ruefully witty poems exchanged between Yugiri and To no Naishi [Koremitsu’s daughter, the Gosechi Dancer] are rather more to my taste than the soggy ones Yugiri and Kumoi no Kari exchanged on their wedding night. Might it be the case that a totally sanctioned relationship is literarily uninspiring?”

“The old lady reaches for the melodramatic ultimate and dies just as Yugiri’s letter arrives.”

The overall effect is like an exceedingly well-educated, gossipy and sassy ride through the entire novel hahaha.

2) Minor typos. I noticed some speckled throughout the text every so often (e.g., Tamakazura being rendered Takakazura, Akashi as Asashi, instances of accidental extra letters, etc.). It was pretty clear what the correct spelling was supposed to be, and TBH considering this is the last of a huge-ass series of over 1300 pages I think it’s forgiveable. Maybe a few that spell-check should have caught, but oh well.

3) This book is NOT CHEAP. As I mentioned in a previous post, not only did I not buy the entire collection, I didn’t even buy a complete Volume 2 - I only bought the last half of the second volume lmao. And the Tale of Genji translations are only HALF of this half of a book. The rest is actually the footnotes, appendices, notes to poems, glossary, bibliography and indices (including indices for every poem by author and by first line) for this beast of a translation/compilation project. This includes a lot of additional commentary and other poems and makes for pretty interesting reading itself, even without the rest of the volumes/parts. The price can definitely be scary and an issue for a lot of people, so if you’re interested in it, I suggest try checking it out at your library or on Google Books first. (In fact, Google Books is how I learned of this book in the first place.)

For me, the depth of insight for the poems was fantastic. It gave me a lot more appreciation for the scenes, including the mental state of the characters, plus a million more symbols, metaphors and ideas for my own creative works like the Genjimonogatari illustration series, North Bound and other original stuff.

It also clarified several fuzzy translation questions I had that relied on specific knowledge of Heian culture and history/evolution of the use of the language and wasn’t easily found in Google searches or online language resources. And even if you’re already familiar with common allusions, metaphors and puns/homophones in Japanese poetry, it’s still helpful to see them all summarized. And sometimes lamented by the book’s author too. SO MANY PONIES EATING GRASS. SO MANY PINES. Especially the pines. (It IS an amazing pun though, especially because it works in both English and Japanese. Pine [tree] -> to pine, matsu/pine tree -> matsu/to wait)

In term of the actual translations themselves, you may still find them coming off a bit roundabout in some cases when comparing to the original Japanese. But overall I find Cranston’s translations more direct/flavourful than how they were rendered in the Tyler translation, partly because of how Tyler chose to juggle his set of translator’s challenges for rendering not only meaning but also more technical aspects of the poetic form. So the imagery ends up being, to me, a lot more vivid. The overall effect usually ends up more colourful, more emotional, more erotic, more cutting, more entertaining, and whatnot.

For example, Kashiwagi’s suitor’s poem in the Kocho/Butterflies chapter. When reading the novel, I was like, uh-huh, yah, OK. When I read it here, I was like whoa, dude, that’s a little intense lol. Cranston’s translation amps up the connotation of the heat of the water based on the rest of the line. For comparison:

(The original non-romaji Japanese in the samples following are thanks to the Japanese Text Initiative from the University of Virginia Library Etext Centre and the University of Pittsburgh East Asian Library. Their Tale of Genji page has a FREAKING AMAZING side-by-side comparison of the novel in original Japanese, modern Japanese and romaji. Bless them and the people who had to organize and wrangle that text together.)

Original Japanese:

思ふとも君は知らじなわきかへり

岩漏る水に色し見えねば

Omou to mo / Kimi wa shiraji na / Wakikaeri

Iwa moru misu ni / Iro shi mieneba

Tyler version: You can hardly know that my thoughts are all of you, for the stealthy spring welling from the rocks leaves no colour to be seen.

Cranston version: Hardly can you know / Of the longing that I feel, / For the boiling wave / Is merely colorless water / As it drains away from the rock.

Here’s another example. Oigimi (Agemaki in the book, as Cranston used Wayley’s names for the sisters) telling Kaoru that he’s the only one who’s been actually visiting them and Kaoru is like all riiiight :Db! From Shii ga Moto / Beneath the Oak chapter:

Oigimi’s poem

雪深き山のかけはし君ならで

またふみかよふ跡を見ぬかな

Yuki fukaki / Yama no kakehashi / Kimi narade

Mata fumikayou / Ato o minu kana

Tyler: No brush but your own has marked the steep mountain trails buried deep in snow / with footprints, while back and forth letters go across the hills.

Cranston: Over the bridges / Clinging to the cliffs along / Our deep-snow mountains / No letter-bearer leaves his trace: / Those footprints are yours alone.

Kaoru’s reply

つららとぢ駒ふみしだく山川を

しるべしがてらまづや渡らむ

Tsurara toji / Koma fumishidaku / Yamakawa o

Shirube shigatera / Mazu ya wataramu

Tyler: Then let it be I who firsts ride across these hills, though on his mission, / where ice under my horse’s hooves crackles along frozen streams.

Cranston: In the sheets of ice / Covering the mountain streams / My steed crushes / Such letters as form my reason, / My first, to cross as a guide.

In other examples, Genji’s “*throws hands in the air* I give up” poetic reply to Suetsumuhana about how she keeps using Robes of Cathay/Chinese cloak imagery in her poems in the original Japanese alongside the translation cracked me up even more. And one of my favourites is a pair of poems between the future Akashi Empress (as a child) and her birth-mother the Akashi lady. It’s really sad, sweet and cute all at the same time and completely flew under my radar when I read the novel originally.

The poetry analysis for the Uji chapters is especially intriguing. The plot pointedly pits Niou against Kaoru as opposing personalities with particular similarities and contrasts that drive their relationship with each other and with the woman they’re competing for. Especially in the latter half of the story, a lot of their poems, even ones written independently (i.e., to Ukifune), are specifically composed to highlight those attributes and play off of each other.

Finally, it’s also super interesting to see my experience with the narrative changes through the lens of the poems. Obviously, as I mentioned, some things I easily missed without paying as much attention to the poems in between the rest of the story. But also, some prominent characters have very few poems, so the narrative shifts away from them. Meanwhile, a number of otherwise very minor or usually overlooked characters stand out even more, thanks to the fineness, loveliness, resonance, and sometimes just sheer consistent presence of their poetry. This book definitely gave me a lot of additional perspective on the Tale of Genji, and enhanced my appreciation of the novel and the skill behind its crafting!

#tale of genji#genji monogatary#waka poetry#a waka anthology#grasses of remembrance#edwin a. cranston#royall tyler#japanese#translation#japanese tranlation#heian period#kaoru chujo#oigimi#agemaki#kashiwagi

3 notes

·

View notes