#a waka anthology

Text

#Tsubomi#Camel#Waka#cigarette#megane#blushing#yuri#yuri anthology#Miyauchi Yuuka#oneshot#Camel cap#my caps

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

大河内山荘庭園

Ohkouchi Sansou Garden

この庭園は昭和初期の映画俳優、大河内傅次郎(1898-1962)百人一首で有名なここ小倉山からの雄大な観光に魅せられて、30年に渡り丹精こめてこつこつと造りたりあげた優美な庭園です。

桜や楓が多く植栽された園内からは、嵐山、保津川の清流、比叡山や京の町並みなども眺められ、四季折々に趣きがあります。近年、国の文化財に指定されました。

This garden, built by the Japanese film star Ohkouchi Denjiro (1898-1962). He constructed this unique garden villa on the south side of Mt. Ogura over a 30 year period. The seemingly endless stroll paths lead to constantly changing views of the classic Japanese garden. The garden is perfect for viewing seasonal beauty at any time of year. In late years, it was appointed in cultural assets of this country.

这个山庄院子、京都电影的繁盛时期、著名的电影明星大河内传次郎、被这圼的美丽所吸引、用自己的收入*置土地、耗时30多年達成的別*。这座占地经五英*的別*位于山上、在**个*京都、入目的是曽经***ー*影星的凤光。近年*、*在这个国家的文化財产指定了。

Okochi Sanso Garden

大河内山荘庭園 →

Vocab

大河内山荘庭園(おおこうちさんそうていえん)Ohkouchi Sansou Garden

俳優(はいゆう)actor/actress

大河内傅次郎 (おおこうち・でんじろう)Ohkouchi Denjiro

百人一首(ひゃくにんいっしゅ)Hyakkunin Isshu, a classical Japanese anthology of 100 waka poems by 100 poets

小倉山(おぐらやま)Mt. Ogura

雄大(ゆうだい)grand, magnificent

魅せられる(みせられる)to be charmed, enchanted

に渡り(にわたり)over a period of…; throughout

丹精(たんせい)working diligently, efforts; sincerely

丹精を込める(たんせいをこめる)to take pains (doing something); to take great care

こつこつ steadily, laboriously, diligently

造る = 作る

優美(ゆうび)grace, refinement, elegance

楓(かえで)maple

植栽(しょくさい)raising trees and plants

保津川(ほづがわ)Hozugawa River

清流(せいりゅう)clear stream

比叡山(ひえいざん)Mt. Hiei

町並み(まちなみ)townscape

眺める(ながめる)to look out over, to admire

四季折々(しきおりおり)from season to season

趣き(おもむき)appearance, aspect; grace, charm, refinement

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The moon has set and the Pleiades; it is midnight, and time goes by, and I lie alone.

Sappho, fragment 168B of Voigt's edition (trans. David A. Campbell)

As you said, 'I'm coming right away,'

I waited for you

through the long autumn night,

but only the moon greeted me

at the cold light of dawn.

Priest Sosei, waka no. 21 of the Hyakunin isshu anthology (trans. Peter Macmillan)

#something something repeating themes in literature across space and time something#the motive of the moon as the only companion of a lonely lover so on and so forth#i'm going nuts!!!!#tagamemnon#there are some doubts in attributing that poem to sappho but that's not really important rn

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

三椏[Mitsumata]

Edgeworthia chrysantha

三[Mitsu] : Three

椏[Mata|A] : Crotch of a tree

It is so named because the each branch almost always forks into three branches. It is native to China and is not well known when it was introduced to our country. In Man'yoshu(The oldest anthology of Japanese poetry,) there are waka poems that contain a flower named 三枝[Sakikusa](Three branches,) and some believe this to be its ancient name.

The flowers have a nice, slightly spicy fragrance. The bark is used to make 和紙[Washi](Japanese paper,) and Japanese banknotes are made from it.

https://www.npb.go.jp/en/intro/tokutyou/

By the way, the portrait on the new 10,000 yen banknote is that of industrialist Shibusawa Eiichi. Shibusawa Tatsuhiko, a novelist and a translator of French literature, is a relative of his. Tatsuhiko's family is the main family.

https://www.mof.go.jp/english/policy/currency/banknotes/20190409.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tatsuhiko_Shibusawa

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

📸雪の永観堂 禅林寺(京都市左京区) Eikando Zenrinji Temple (Snow), Kyoto ——Eikando Temple, famous for its maple leaves, was written about in the Kokin Waka Shu (Anthology of Ancient and Modern Japanese Poetry) during the Heian period (794-1185). The precincts of the temple, centering around the pond garden "Hojoike," are beautiful even on a snowy day! ——平安時代に『古今和歌集』にも詠われた京都の紅葉の名所“もみじの永観堂”…🍁 京都の紅葉���ンキング一位、二位の人気をほこる寺院は、池泉庭園“放生池”を中心とした境内は雪の日も美しい!☃️ ———————— ▼他の写真や解説のつづきは @oniwastagram のプロフURLかこのURLから。 For more photos and commentary, please visit @oniwastagram 's profile URL or this URL. https://oniwa.garden/eikando-kyoto-snow/ ———————— #japanesegarden #japanesegardens #kyotogarden #zengarden #beautifulkyoto #beautifuljapan #japanesearchitecture #japanarchitecture #japanarchitect #japandesign #jardinjaponais #jardinjapones #japanischergarten #jardimjapones #landscapedesign #kyototemple #庭院 #庭园 #庭園 #日本庭園 #京都庭園 #京都雪 #京都雪景色 #雪の京都 #借景 #おにわさん (永観堂禅林寺) https://www.instagram.com/p/CogJFZYPySB/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#japanesegarden#japanesegardens#kyotogarden#zengarden#beautifulkyoto#beautifuljapan#japanesearchitecture#japanarchitecture#japanarchitect#japandesign#jardinjaponais#jardinjapones#japanischergarten#jardimjapones#landscapedesign#kyototemple#庭院#庭园#庭園#日本庭園#京都庭園#京都雪#京都雪景色#雪の京都#借景#おにわさん

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

anyway so i have had to do so much art history research for this tmnt fic b/c 1. the main character is an artist and i have to plausibly narrate about the artistic process and 2. there's a bunch of art history stuff about historical art techniques too

i mean there's a limit to how much research for accuracy i'm willing to do so i'm sure a lot of the details are wrong but w/e it's fine

some of the things i've turned up in this process:

'selected poems from kokin wakashu', with commentary.

from wikipedia:

The Kokin Wakashū (古今和歌集, "Collection of Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times"), commonly abbreviated as Kokinshū (古今集), is an early anthology of the waka form of Japanese poetry, dating from the Heian period. An imperial anthology, it was conceived by Emperor Uda (r. 887–897) and published by order of his son Emperor Daigo (r. 897–930) in about 905. Its finished form dates to c. 920, though according to several historical accounts the last poem was added to the collection in 914.

The compilers of the anthology were four court poets, led by Ki no Tsurayuki and also including Ki no Tomonori (who died before its completion), Ōshikōchi no Mitsune, and Mibu no Tadamine.

[...]

The idea of including old as well as new poems was another important innovation, one which was widely adopted in later works, both in prose and verse. The poems of the Kokinshū were ordered temporally; the love poems, for instance, though written by many different poets across large spans of time, are ordered in such a way that the reader may understand them to depict the progression and fluctuations of a courtly love-affair. This association of one poem to the next marks this anthology as the ancestor of the renga and haikai traditions.

some of the commentary i particularly enjoyed:

よみ人しらず

題しらず

梅花たちよるばかりありしより人のとがむるかにぞしみぬる

ume no hana

tachiyoru bakari

arishi yori

hito no togamuru

ka ni zo shiminuru

Anonymous

Topic unknown

I lingered only a moment

beneath the apricot blossoms

And now I am

blamed for my

scented sleeves

In the context of its presumed source, the personal collection of Fujiwara no Kanesuke (d. 933), this is a love poem sent to a woman facetiously complaining that incense, redolent of apricot (or plum) blossoms, burnt to scent her robes, has infused his own, and that their relationship has thus been discovered by members of his household. That his complaint is facetious is attested by the evidence that he sent this poem to the woman (who knows better) by way of stating his intention not to be dissuaded. The editors of Kokinshu signal their intentions to reread this as a poem on "plum blossoms," not love, by placing it as an anonymous poem obliquely praising the seductive depth of the scent of the blossoms, in support of the poet's claim to have lingered only briefly.

and also

題しらず

ほのぼのと明石の浦の朝霧に島がくれ行く舟をしぞ思ふ

このうたは、ある人のいはく、柿本人麿が哥也

honobono to

akashi no ura no

asagiri ni

shimagakure yuku

fune wo shi zo omou

Anonymous

Topic unknown

Into the mist, glowing with dawn

across the Bay of Akashi

a boat carries my thoughts

into hiding

islands beyond

Some say that this poem was composed by Kakinomoto no Hitomaro.

Passage into Akashi Bay meant crossing the official gateway at Settsu from the Inner to the Outer Provinces, and the implied topic is border-crossing. This is one of the most often quoted and allegorically glossed poems of Kokinshu, and became one of a core of poems treated as having profoundly esoteric meanings within the "Secret Teachings of Kokinshu." Its reputation was enhanced, certainly, by the attribution to Hitomaro, venerated as one of the deities of the Way of Poetry. One Nijo School commentary suggests that the poem, generally taken as an allegory of the death of Prince Takechi, was deliberately placed by the editors in the book of travel rather than in that of mourning to free it from taboos attaching to poems of mourning.

just like, oh yeah the thing with history and with art is that they're enormously context-heavy; all of these poems were written in a certain artistic tradition, and the editors who rearranged and placed them in dialog with each other are synthesizing new interpretations of them. or just making categorization jokes.

the other thing i saw and really liked is this series of ukiyo-e prints called 'Tokaido 53 stations'. (as wikipedia says: a series of ukiyo-e woodcut prints created by Utagawa Hiroshige after his first travel along the Tōkaidō in 1832)

so the tokaido was one five 'great roads', the most important one (it linked edo and kyoto, so, yeah pretty important) and the artist traveled on it as part of some kind of ceremonial horse-gift delegation from the shogun to the emperor. that's a situation with whole other context that i don't know. anyway there were stations on the roar, you know, official inns and the like, and he ended up making a print for each station. (there's some debate over whether he actually saw each station since some of the prints are inaccurate or derivative of other illustrations & who can say to what degree that's just taking artistic liberty. one of the prints depicts a wintertime scene with snow and it's like, wait it doesn't actually snow at that location. maybe he just wanted to depict all four seasons and picked that station.)

i really liked the one of hakone and that got me to start looking where i could get a print of the thing. you can obviously go to like, art.com or walmart, or w/e and they're like oooh look you can get a premium giclée print of this!! a giclée print is just like a fancy inkjet printer, which i guess makes a certain amount of sense for prints of paintings, but these are woodblock prints. they're literally designed to be mass-produced! there's not really an 'original' of any of these, unless you consider 'first printing with original woodblocks' to be the 'originals', and all further printings to be 'reproductions'

so i went looking for anybody who was actually doing woodblock prints of these things in the modern day. that lead me to UNSODO: "UNSODO is the only publishing company in Japan that publishes woodblock prints." i don't know if that's really true or accurate but it's on their website.

they do have a bunch of HIROSHIGE prints on their store (which you might note is not an e-store; you have to email them your order information and they'll get back to you) they're ~13000 yen which is a vast difference from the $50 prints you can get at art.com but uhh these would be actual replications of the method of production, not just a laserjet given a big png of the print. you can also buy them via kyoto handcraft center for a like 90% markup for the convenience of a automated e-store, which seems like not a great deal imo.

anyway all of that definitely had me thinking about art and artistic production and replication and the ways art is both immortal and ephemeral. something something walter benjamin the work of art in its age of technological reproducability.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

it's ashame that waka hirako's other work isn't fantranslated at all...i love anthology stories...

0 notes

Text

From published Anthology

WAKA AMA WAHINE

Listen to the gentle whisper of a Karakia through the air

And feel the gentle caress of the sea guardian through your hair

Your Silhouettes slowly glide across the morning horizon line

With the beauty of the moment an image called divine

The white gulls circle around you through the breaking dawn

The pastel colours of sunlight reflect the sorrows since earth was born

The…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Kung nabasa ninyo ang marisinang fic na "Umagang Kay Sarap" sa AO3, share ko lang na may komiks adaptation nito!

Halaw sa marisinang fanfic na ito ang "Sa Wakas, Nakauwi Na," isang er0tikong komiks na mababasa sa Rurok anthology ng Komiket! Kasama ko rito si S. Invicta, kapwa lesbiyana rin.

Kung interesado kayong bumili ng kopya, takits sa October Komiket! :D

1 note

·

View note

Text

THE MANYOSHU

"The Man'yōshū (万葉集, literally "Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves") is the oldest extant collection of Japanese waka (poetry in Classical Japanese), compiled sometime after AD 759 during the Nara Period. The anthology is one of the most revered of Japan's poetic compilations. The compiler, or the last in a series of compilers, is today widely believed to be Ōtomo no Yakamochi, although numerous other theories have been proposed. The chronologically last datable poem in the collection is from AD 759. It contains many poems from a much earlier period, with the bulk of the collection representing the period between AD 600 and 759. The precise significance of the title is not known with certainty.

The Man'yōshū contains 20 volumes and more than 4,500 waka poems, and is divided into three genres: Zoka, songs at banquets and trips; Somonka, songs about love between men and women; and Banka songs to mourn the death of people. These songs were written by people of various statuses, such as the Emperor, aristocrats, junior officials, Sakimori soldiers (Sakimori songs), street performers, peasants, and Togoku folk songs (Eastern songs). There are more than 2,100 waka poems by unknown authors."

Source

0 notes

Quote

How confusing,

the first day of spring has arrived

before the first day of the year

Hijikata Toshizo

Original: 朧ともいはて春立つ年の内

Read all of Hijikata’s haiku poems here: https://shinsengumi-archives.tumblr.com/post/683071924948058112/hijikata-toshizos-haiku-poems

image source: WhiteWind歴史館

fushigi-dono:

The idea is this: according to the old lunar calendar, the first day of the New Year was also the first day of spring. Depending on the lunar cycle, it fell at the end of January or the first or even the second day of February. With the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, February 3 (Setsubun holiday) was established as the permanent "day of the coming of spring”. It was around this time that spring came in Japan.

In the past, it used to be that the New Year had not yet come, but spring had actually already arrived! This was called "nennai risshun" (年内立春) - "the spring that came before the end of the year," and this phenomenon was often reflected in poetry.

WhiteWind歴史館:

The first day of spring has arrived,

even though it is not even springtime,

and it is before the beginning of the new year.

In the lunar calendar, which was based on the phases of the moon, the first day of the year and the first day of spring were supposed to be at about the same time, but in reality there was a discrepancy, and the date of the first day of spring actually fluctuated between December 15 and January 15.

In this way, there were quite a few cases where the first day of spring fell before New Year's Day, which is called "nennai risshun" (年内立春) or "first day of spring within this year" and has been the subject of waka and haiku poems for a long time.

A famous example is a poem by Aihara Motokata in the Kokin Wakashu anthology

Spring will come before the year is out, and you will not say "last year" but "this year".

~The first day of spring has come before the new year. I wonder if this year is “last year” or “this year”.

Toshizo also wrote a haiku about "nennai risshun" in the same way.

The reason for this is that "it’s confusing, even though it's still far from spring-like, it's already spring before the end of the year.”

#poem#quote#hijikata quote#Hijikata#translated#translated from Japanese#fushigidono#series: hijikata haiku#hijikata poem

0 notes

Text

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on Grasses of Remembrance (The Tale of Genji through its poetry)

Finally had some time this weekend to sit down with A Waka Anthology, Volume 2: Grasses of Remembrance Part B by Edwin A. Cranston. This book is the last in an impressive and intimidating collection translating a number of major classical poetry anthologies. It’s basically a speedrun through Tale of Genji (if such a thing were possible) filtered through all 795 waka poems written or uttered by the characters over the course of the novel.

Poetry was a Really Big Deal during the Heian era. If you were an aristocrat, not only were you expected to compose decent poetry, you had to be able to do it off-the-cuff appropriate to the occasion. AND to do this properly, you were expected to be able to recognize and respond cleverly to references to a ton of other existing classic poems from memory that people would just mention casually in conversation or writing (kinda like how people quote the Simpsons today lol). This was a prime marker of how intelligent/competent and - no joke - how sexy you were. So not surprisingly, these poems are extremely important to the development of character interactions and themes in the Tale of Genji which has a lot of romance and relationship plotlines.

However. Translating Heian era Japanese into modern Japanese is already challenging. Rendering Heian era Japanese waka poetry into modern English is, as you might imagine, harder for a bunch of reasons. Considering how dense the actual novel already is, it’s super easy to gloss over the poetry, and some modern translations simply integrate the basic intent of the poems right into the main text/dialogue.

I was really interested in finding something specifically focusing on and analyzing the poetry, and this book appeared to fit the bill.

Short review: IT TOTALLY DOES. If you’re into Tale of Genji, Heian era, classical Japanese history, classical Japanese literature, Japanese poetry, or just love reading translators articulating eloquently while sassing characters or flailing through linguistic complexities, I RECOMMEND THIS BOOK

Long review: blah blah blah thoughts follows, including some quotes/poem for reference.

The book starts with a quick 2 page intro setting the context of the Tale of Genji, then goes straight into the poems. TBH I personally found it more flowery and redundant than necessary (it repeats a few poems that are then explained later). But it’s only 2 pages, we’ll live.

Then, the poems. For every poem (or poems, in the case of an exchange - sometimes a flurry of them with multiple characters speaking or dashing letters off to each other) there’s an intro and summary of context followed by an analysis, including notes on meaning, narrator and character intent, structure, symbols and wordplay. The original Japanese is included in romaji alongside the English translation. The commentary also flags known references to other classic poems (WITH those poems in-line! This is awesome because I don’t have the rest of these books!), and even mentions poem and folk song quotations from the rest of the novel where the characters have not composed new poetry, but are reciting other existing known pieces.

Overall, I have only three real “warnings” about Grasses of Remembrance Vol 2b:

1) It’s very academic and flowery in tone. If you’re not used to it, it can be hard to read. But then again, if you’re not willing to get past that, how are you reading Tale of Genji? lol. In any case, I personally thought the commentary was a lot of fun. Cranston definitely has opinions and can get pretty sarcastic in places, which I found hilarious. Here are a few sample quotes:

“Tamakazura has remarked to herself how superior the Emperor [Reizei] was in looks to all the courtiers in his train (It is a principle with this author that superior people be dashingly handsome or ravishingly beautiful).”

“The ruefully witty poems exchanged between Yugiri and To no Naishi [Koremitsu’s daughter, the Gosechi Dancer] are rather more to my taste than the soggy ones Yugiri and Kumoi no Kari exchanged on their wedding night. Might it be the case that a totally sanctioned relationship is literarily uninspiring?”

“The old lady reaches for the melodramatic ultimate and dies just as Yugiri’s letter arrives.”

The overall effect is like an exceedingly well-educated, gossipy and sassy ride through the entire novel hahaha.

2) Minor typos. I noticed some speckled throughout the text every so often (e.g., Tamakazura being rendered Takakazura, Akashi as Asashi, instances of accidental extra letters, etc.). It was pretty clear what the correct spelling was supposed to be, and TBH considering this is the last of a huge-ass series of over 1300 pages I think it’s forgiveable. Maybe a few that spell-check should have caught, but oh well.

3) This book is NOT CHEAP. As I mentioned in a previous post, not only did I not buy the entire collection, I didn’t even buy a complete Volume 2 - I only bought the last half of the second volume lmao. And the Tale of Genji translations are only HALF of this half of a book. The rest is actually the footnotes, appendices, notes to poems, glossary, bibliography and indices (including indices for every poem by author and by first line) for this beast of a translation/compilation project. This includes a lot of additional commentary and other poems and makes for pretty interesting reading itself, even without the rest of the volumes/parts. The price can definitely be scary and an issue for a lot of people, so if you’re interested in it, I suggest try checking it out at your library or on Google Books first. (In fact, Google Books is how I learned of this book in the first place.)

For me, the depth of insight for the poems was fantastic. It gave me a lot more appreciation for the scenes, including the mental state of the characters, plus a million more symbols, metaphors and ideas for my own creative works like the Genjimonogatari illustration series, North Bound and other original stuff.

It also clarified several fuzzy translation questions I had that relied on specific knowledge of Heian culture and history/evolution of the use of the language and wasn’t easily found in Google searches or online language resources. And even if you’re already familiar with common allusions, metaphors and puns/homophones in Japanese poetry, it’s still helpful to see them all summarized. And sometimes lamented by the book’s author too. SO MANY PONIES EATING GRASS. SO MANY PINES. Especially the pines. (It IS an amazing pun though, especially because it works in both English and Japanese. Pine [tree] -> to pine, matsu/pine tree -> matsu/to wait)

In term of the actual translations themselves, you may still find them coming off a bit roundabout in some cases when comparing to the original Japanese. But overall I find Cranston’s translations more direct/flavourful than how they were rendered in the Tyler translation, partly because of how Tyler chose to juggle his set of translator’s challenges for rendering not only meaning but also more technical aspects of the poetic form. So the imagery ends up being, to me, a lot more vivid. The overall effect usually ends up more colourful, more emotional, more erotic, more cutting, more entertaining, and whatnot.

For example, Kashiwagi’s suitor’s poem in the Kocho/Butterflies chapter. When reading the novel, I was like, uh-huh, yah, OK. When I read it here, I was like whoa, dude, that’s a little intense lol. Cranston’s translation amps up the connotation of the heat of the water based on the rest of the line. For comparison:

(The original non-romaji Japanese in the samples following are thanks to the Japanese Text Initiative from the University of Virginia Library Etext Centre and the University of Pittsburgh East Asian Library. Their Tale of Genji page has a FREAKING AMAZING side-by-side comparison of the novel in original Japanese, modern Japanese and romaji. Bless them and the people who had to organize and wrangle that text together.)

Original Japanese:

��ふとも君は知らじなわきかへり

岩漏る水に色し見えねば

Omou to mo / Kimi wa shiraji na / Wakikaeri

Iwa moru misu ni / Iro shi mieneba

Tyler version: You can hardly know that my thoughts are all of you, for the stealthy spring welling from the rocks leaves no colour to be seen.

Cranston version: Hardly can you know / Of the longing that I feel, / For the boiling wave / Is merely colorless water / As it drains away from the rock.

Here’s another example. Oigimi (Agemaki in the book, as Cranston used Wayley’s names for the sisters) telling Kaoru that he’s the only one who’s been actually visiting them and Kaoru is like all riiiight :Db! From Shii ga Moto / Beneath the Oak chapter:

Oigimi’s poem

雪深き山のかけはし君ならで

またふみかよふ跡を見ぬかな

Yuki fukaki / Yama no kakehashi / Kimi narade

Mata fumikayou / Ato o minu kana

Tyler: No brush but your own has marked the steep mountain trails buried deep in snow / with footprints, while back and forth letters go across the hills.

Cranston: Over the bridges / Clinging to the cliffs along / Our deep-snow mountains / No letter-bearer leaves his trace: / Those footprints are yours alone.

Kaoru’s reply

つららとぢ駒ふみしだく山川を

しるべしがてらまづや渡らむ

Tsurara toji / Koma fumishidaku / Yamakawa o

Shirube shigatera / Mazu ya wataramu

Tyler: Then let it be I who firsts ride across these hills, though on his mission, / where ice under my horse’s hooves crackles along frozen streams.

Cranston: In the sheets of ice / Covering the mountain streams / My steed crushes / Such letters as form my reason, / My first, to cross as a guide.

In other examples, Genji’s “*throws hands in the air* I give up” poetic reply to Suetsumuhana about how she keeps using Robes of Cathay/Chinese cloak imagery in her poems in the original Japanese alongside the translation cracked me up even more. And one of my favourites is a pair of poems between the future Akashi Empress (as a child) and her birth-mother the Akashi lady. It’s really sad, sweet and cute all at the same time and completely flew under my radar when I read the novel originally.

The poetry analysis for the Uji chapters is especially intriguing. The plot pointedly pits Niou against Kaoru as opposing personalities with particular similarities and contrasts that drive their relationship with each other and with the woman they’re competing for. Especially in the latter half of the story, a lot of their poems, even ones written independently (i.e., to Ukifune), are specifically composed to highlight those attributes and play off of each other.

Finally, it’s also super interesting to see my experience with the narrative changes through the lens of the poems. Obviously, as I mentioned, some things I easily missed without paying as much attention to the poems in between the rest of the story. But also, some prominent characters have very few poems, so the narrative shifts away from them. Meanwhile, a number of otherwise very minor or usually overlooked characters stand out even more, thanks to the fineness, loveliness, resonance, and sometimes just sheer consistent presence of their poetry. This book definitely gave me a lot of additional perspective on the Tale of Genji, and enhanced my appreciation of the novel and the skill behind its crafting!

#tale of genji#genji monogatary#waka poetry#a waka anthology#grasses of remembrance#edwin a. cranston#royall tyler#japanese#translation#japanese tranlation#heian period#kaoru chujo#oigimi#agemaki#kashiwagi

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A close up of Inuyasha and Kagome. This art commish is being used for a "yet-to-be-revealed-project"

As I was sketching it, I imagined that perhaps Kagome was taking a moment to study while Inuyasha ferried them across a lake. Perhaps it was Hyakunin Isshu (Single Songs of a Hundred Poets) for Japanese literature class - an anthology of 100 waka poems, by 100 different famous poets of antiquity. Perhaps one of them touched Inuyasha's heart as she read them aloud, and he decided to seize the moment, their audience flying above them forgotten...

43 Chūnagon Atsutada

Ai mite no

Nochi no kokoro ni

Kurabureba

Mukashi wa mono o

Omowazari keri

Fujiwara no Atsutada

I have met my love.

When I compare this present

With feelings of the past,

My passion is now as if

I have never loved before.

#inukag fanart#art commish#mamabearcat fanart#waka poems#inukag#inuyasha fanart#inuyasha#kagome higurashi

122 notes

·

View notes

Photo

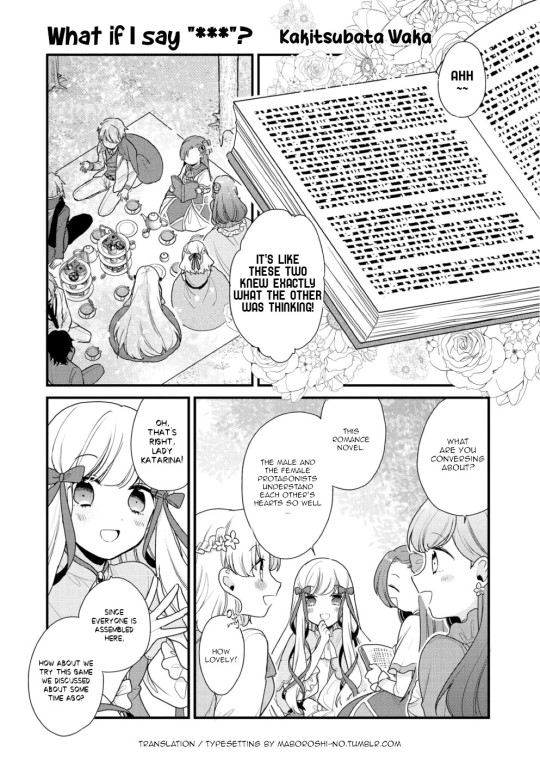

Title: What if I say “***”?

Artist: Kakitsubata Waka

Source: Otome Game no Hametsu Flag shika Nai Akuyaku Reijou ni Tensei shiteshimatta... Comic Anthology Vol 2 (DNA Media), Chapter 15 (Final)

Synopsis: Katarina and the gang are playing a word association game.

Link: You can read the whole comic on Imgur.

Comment: This is the last story of the book! I’m glad I could complete it before the end of the year!

Credits:

Translation / Typesetting : maboroshi-no

#hamefura anthology#hamefura#bakarina#katarina claes#geordo stuart#Mary Hunt#Sophia Ascart#keith claes#nicol ascart#alan stuart#maria campbell

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

The poem from Noragami chapter 95

As many have already figured out, the poem Takemikazuchi recited in Noragami chapter 95 was composed by Kakinomoto Hitomaro. This particular poem is taken from the Waka anthology Kokin Wakashu. I decided to dive a bit deep into the poem.

The following parts are taken from my Noragami chapter 95 thoughts, feel free to give it a read whenever you can!

Here’s the verse in Japanese;

Honobono to

Akashi no ura no

Asagiri ni

Shimagakureyuku

Fune o shi zo omou

If we go deeper, there are multiple ways to interpret this poem. The Kokin Wakashu classifies this as a travel poem. However, the content of the poem varies widely in tone based on different understandings.

According to multiple instances listed in Hitomaro: Poet as God, this poem definitely has undertones of lament despite being a travel poem on the outside. It was written to commemorate the death of either Emperor Mommu or Prince Takechi. Meaning, the mist, island and boat in the poem are not to be taken in a literal sense.

The Kokin Wakashu Kanjo Kuden interprets the morning mist here as the mist that separates. What if this mist signifies the boundary between the near and far shore?

The poem is supposed to convey how it is impossible to escape death, even for an imperial ruler. Using a subtle play on the word “island” (shima), which could also mean four devils, Hitomaro specifies the four sufferings of birth, old age, illness, and death through which a person has to pass. The boat here signifies the sovereign, but from the POV of Noragami, it could be referring to the journey of a person through all these four sufferings before crossing over to the other side.

It fit in perfectly with the scenario at hand in Noragami chapter 95, so kudos to Adachitoka for including it. But beyond that, I am still undecided on what kind of importance/role this poem would have in Father’s past, other than being tied to the Tamatsuki poem with hints to the island’s location. It is possible that this waka was composed (548 – 710) and compiled (905-920) roughly in the same period as Father was alive (read this post here), explaining why it was used in tandem with the clue.

Could the undertones of lament be suggesting that this poem was used by Father in memory of the woman with pockmarks on her face? Could the interpretation of the poem in any way allude to Father’s beliefs?

Now, here’s another comparison & translation of the poem, wherein the poem is broken up into four units. I won’t go into the details, but read the translations at the bottom (colors are brilliant one). Does that in anyway remind you of Father? If yes, then we are on the same boat (to Tamatsuki!!)

Or, is the underlying idea of inescapable death somehow related to the God’s greatest secret, which is apparently something to be careful of, on Tamatsuki.

Suzuki Harunobu, a Japanese designer of woodblock print in the Edo period, designed his own interpretation of Hitomaro’s verse. In it he alludes to the poem by depicting a young woman looking out a window toward the distant boats, lost in thought. A tinfoil assumption would be that Adachitoka took this reference, and it is again somehow connected to the woman with pockmarks.

@kanotototori @nyappytown I’d like to hear what you have to say about this!!

#noragami spoilers#noragami chapter 95#yato#yatogami#ebisu#takemikazuchi#kiun#Kakinomoto Hitomaro#adachitoka#waka#japanese poetry#what am i even doing here

69 notes

·

View notes