#generations is primarily about sneering at people who liked the original series

Text

If I'm being honest, I haven't liked a lot of STAR TREK since TNG canonically established in "Encounter at Farpoint" that the Federation's supposedly utopian future Earth is a post-apocalyptic world, which was a profound betrayal of the promise of STAR TREK as a positive future and permanently colored my attitude toward TNG and its successors (with the conditional exception of DEEP SPACE NINE, which has some unique virtues to partly mitigate its various failings). The nadir of that shift is the ideologically repellent STAR TREK: FIRST CONTACT, which takes a potentially compelling moment in the TREK timeline and turns it into a ghastly Libertarian zombie movie, but PICARD and STRANGE NEW WORLDS taking pains to rub viewers' faces in this dishonest and cynical conceit all over again hasn't improved my opinion of those shows.

#teevee#movies#star trek#star trek the next generation#star trek first contact#the vonda mcintyre novel strangers from the sky#takes a much more thoughtful view of human-vulcan first contact#it's not without stain politically but it's not the horror show that the movie first contact is#and its take on the eventual “official” first contact is fascinating#i'm not wild about star treks v and vi but they're better than tng by far#generations is primarily about sneering at people who liked the original series#it's not as *ideologically* offensive as first contact but it's about as antagonistic as a viewing experience

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Downfall of a Dark Avenger Part 1: El Sombra

Having finished reading Al Ewing’s El Sombra trilogy and having had enough time to digest it, I’d like to talk about the trajectory of it’s titular protagonist, the character and series’s relationship with it’s influences. Relating to The Shadow and Zorro and general pulp archetypes, and also the way it incorporates Astro Boy’s Pluto into the mix. My interest in Pluto’s imagery led to me reading Naoki Urasawa’s Pluto, and I will go into the correlation between all of these seemingly random sources coming together.

But before we can talk about what El Sombra becomes, we must talk about what he is, and where he starts.

The very first chapter of El Sombra is dedicated to establishing the happy scenery of the village of Pasito, as a big wedding is drawing the entire town together, eager to see one of it’s greatest heroes marry his sweetheart. We get a great description of said hero Heraclio...and then the reveal that the character we’re gonna be following for the rest of the story is not Heraclio, but instead his loser brother Djego, a morose, slow-witted poet largely considered a joke by the village, currently being rejected and beaten by the love of his life, which is just about the 2nd worst thing that happens to him that day, followed by winged Nazis storming the village, murdering scores of men, women and children, killing Djego’s brother as he watches helplessly, and then said brother cursing Djego with his dying breath as Djego just barely escapes into the desert, with nothing but a sword and a wedding sash in hand. Djego is probably the last man in the village anyone could have possibly expected to become a hero (which may be part of why he ended the way he did).

Cut to 9 years later, Pasito has been transformed into a mechanized nightmare, a clockwork city of endless toiling and suffering ruled by Nazis, freely enacting their every dark whim on it’s population, revealed to be little more than just a large-scale experiment conducted by the Nazis to increase workforce enough to match Britain’s. After two agonizing chapters with little more than Nazi atrocities to occupy our time, we get our first look at the intrepid hero, Djego. And how does El Sombra introduce himself? Through laughter.

The laughter. Rich and strong, echoing around the square, freezing the milling workers in their tracks. An awful laugh - a terrible laugh of hope and joy and strength! A sound that had not been heard in the clockwork-town for nine years.

as the sound of laughter echoed across the town, the men shuddered and glanced at each other briefly, as though hearing the first sounds of an approaching storm.

The smile on the creature's face was powerful and confident and utterly unafraid. To Alexis, it seemed like the smile the devil might have in the deepest pits of Hell.

For the most part, El Sombra is heavily modeled after Zorro. He’s got Zorro’s swashbuckling fighting style, wields primarily a sword, his main outfit is styled partially after Douglas Fairbanks’s costume, he can be quite friendly and charming and peppers an “amigo” at every sentence. His name is the same as Diego’s minus one letter, his main enemies specifically consist of tyrants who rule over his town, and his mission of vengeance gradually turns him into a rebellious, inspirational figure for the city he strives to liberate. El Sombra is Zorro vs Nazis and it delivers on that.

But nothing is ever quite as it seems in this trilogy, and the first installment of El Sombra goes to great lenghts to establish that El Sombra is a long, long way from being the pure and heroic fantasy that Zorro embodies. He doesn’t live in a world where problems can be solved with guile, luck, good swordplay and a good smile. He doesn’t live in a world where he can show up, humble imperialists and get the people behind him. He lives in a world where the only recourse available to him, to even stand a chance, was nine years of an extended fugue state trip through the desert, ingesting hallucinogens, having his soul shattered and then repaired into something much, much darker. And it’s in those moments that we start to see why exactly his name is El Sombra.

There was something in his voice as cold and unyielding as a gravestone.

"Djego is dead, Father Santiago. He was useless and stupid and pathetic. And he died and left good flesh behind. So I took his place." The eyes behind the mask met Santiago's then, and the priest breathed in sharply. There was nothing of Djego in them. There was nothing human in them.

Something bigger had lodged there, something stronger and faster than a man, something with a laugh that could shake mountains and a spirit like hot iron and fire. Something better.

"I am his shadow. El Sombra."

Atop of his inhuman speed and agility and skill at combat and murder, Djego repeteadly demonstrates skills and traits that, not only did he not have prior, but he couldn’t have picked simply in his desert sojourn. He knows how to apply advanced first aid, he speaks German, in Gods of Manhattan he is able to get the drop on Blood-Spider with a textbook Shadow hypnotic trick, and for all of those, the only explanation he gives is a shrug and “I picked it up somewhere”. Djego had the same trip to the unknown that defined The Shadow and so many other pulp heroes, except Ewing never provides any explanation for El Sombra’s advanced skills other than what the character says. Because there is no explanation. El Sombra is bigger than that.

El Sombra has to be, because a mere man with training and skills and strength and inspirational heroism isn’t going to cut it against what he’s up to. His brother had all of those things, and he died in the first chapter. Like The Shadow, El Sombra has warped himself to address calamity upon mankind, and morphed into something bigger and darker than just another vigilante.

In that moment, El Sombra knew himself to be no longer a man. He was, instead, what the ticking clock had made of him. He was a monster.

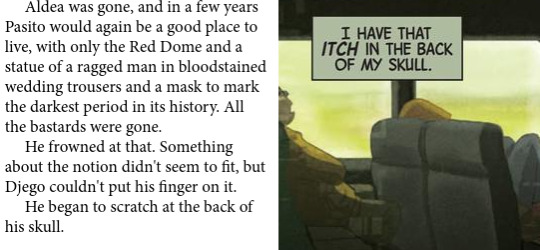

In fact, with the devil imagery Ewing grants upon El Sombra at points, and the reocurring “itch in the back of the skull” prelude to crucial moments, you can pinpoint exactly the points where El Sombra’s character traits would later manifest in Immortal Hulk, with Ewing’s reinvention of the Hulk plumbing the darkest possible alternatives for said character by digging into the greater horror roots of the character. This will be more relevant when we get to Pluto though.

But to put it plainly, Djego may be Zorro in every aspect at his surface. He may desperately strive to be Zorro, and it may be his Zorro traits that allow him to truly save Pasito. But Djego is not Zorro. He is El Sombra, as illustrated most in the following sequence. The moment where he pulls the most Shadow-esque destruction of a Nazi ever since The Shadow convinced a Nazi general to gut himself with his own sword.

The chained man began to laugh. Softly at first, then louder, the sound rolling through the quiet, cold room like the skeletons of winter leaves in a chill and bitter wind. It was not a laugh of joy, or of hope, or of strength, or of anything associated with sunlight and clean air. It was a laugh that belonged in these dank and fetid conditions, a snide chuckle, a sneering, contemptuous snicker. A laugh like a thousand beetles marching across a sheet of glass.

It was a sound that would have been sickeningly familiar to anyone who had once been a guest of the Palace Of Beautiful Thoughts. The old man started back, looking at the features of his chained captive, breathing in sharply as the handsome face of the terrorist became foreign and strange, warped by the noise emanating from it. He recognised the sound too, recognised the dry, hollow chuckle. And it chilled him.

The chained man turned his head, as though on aged bones, and smiled, a dry and sinister grin. And then he spoke. And the voice that came from his throat did not belong to El Sombra at all.

The chained man spoke with Master Minus' voice.

The chained man's smile froze him in his tracks. It promised terrible cruelty, a mephistophilean love of manipulation, and the eyes sparkled with fire from the depths of Hell itself. The old man sucked in another breath scented with sickly yellow and looked desperately away, to find himself staring once again at the mirror, at the face that was surely not his own...

The old man, who suddenly felt neither old nor a man, raised his hands, fingertips touching the aged, wrinkled face with the unfamiliar eyes. Could he fool himself that his fingertips travelled across soft, worn flesh, lined with years of service? Or was he feeling sterile plastic, soft, loose latex? He shuddered, the motion travelling up his spine, his hands shivering and twitching as he tugged ...

"Take off the mask."

... and the old, wrinkled, false face was torn away, coming off in long strips, pulled away bit by bit to reveal another face underneath. His eyes were wide, unblinking, unable to close as he stared at the face underneath, the face that had been there all the time.

Behind him, the thin beetle-voice spoke once more.

And this is what it said:

"APRIL FOOL! Quién es el hombre? Quién es el hombre? I'm the hombre! I'm the hombre! Now all I need are some pants."

El Sombra grinned down from the vertical rack at Master Minus, slumped on his knees in front of the blood spattered mirror, staring without eyelids at the remains of his face. He had succeeded in tearing all of the flesh from it, and all that remained were a few scraps of muscle clinging to a crimson, bloodstained skull, with two grotesque eyeballs gazing mercilessly at their own reflection. El Sombra smiled and did the voice, again while he made another attempt to work his left hand free of the shackle that held it in place.

"Creatures of the night... what music... they make... I vant to suck your blooood... yeah, you keep looking, amigo. Intense shame boosted by mind-warping drugs, hey? That's very original, I wouldn't know what that's like at all... ah, these bastard cuffs!" He was babbling, a result of the endorphin rush from the intense pain and the thrill of victory.

The yellow mist coursing through his veins - the mist Master Minus relied on so heavily - had been counterbalanced by the Trichocereus Validus already in his system, the desert cactus that had destroyed and rebuilt his mind. But while El Sombra was in a stronger position than the torturer realised, Master Minus was weaker than he knew, far too used to the easy victories the mist brought him, not realising that his own exposure to it made him ripe for psychological attack. The old man had spent years claiming that he was immune to the yellow mist, but nobody had ever been in a position to test that claim - until now.

In the end, El Sombra is able to drive the Nazis out of Pasito, and he’s succeded in ultimately inspiring the population to rally against them, eventually winning not because of said darkness granting him power, but by turning said darkness into a tool of good. The true victories of El Sombra are not in the violence, but in selfless heroism, in actions big and small. And in the end, He’s given even the opportunity of a happy ending, to settle down in the town he’s wanted so long to rescue. And if this were the story of Djego, the poet turned hero of his hometown, that’s where it would end.

But this is not Djego’s story. It’s the story of a man who’s destroyed himself to be rebuilt as an avenging force of nature. Someone who’s subsumed as much of his humanity as he could, who now can see and done things much beyond the scope of ordinary man, and now must pay the price of said terrible gifts. Who will pay much, much bigger prices for them in the future. It’s the story of El Sombra, and it’s only just begun:

It was too bad about Djego. El Sombra regretted little, but he regretted denying Djego that one small chance at happiness. But it couldn't be helped.

Until Adolf Hitler was dead, El Sombra could never rest

The man walked west, towards the sinking sun.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Golden Wall of Science Fiction

Posted by Rampant Coyote on September 4, 2018

I grew up reading stories from the “pulp era.” I also grew up playing Dungeons & Dragons (well, once I turned 12… so reading predated the playing by a little bit). Until I read Appendix N by Jeffro Johnson, I didn’t realize there was a connection between the two. When I first started playing D&D, it was pretty much “anything goes.” Science fiction, fantasy, horror, whatever… it all worked. Old-school D&D was like that… as was old-school pulp. I didn’t consciously realize this, it was just the attitude reflected in the rules and game modules, in the articles and letters in Dragon magazine, Polyhedron, and similar periodicals (ah, the days before the Internet). It was on the covers of Heavy Metal and White Dwarf magazine. And it was part of my favorite films, the original Star Wars trilogy, featuring space wizards with magic swords battling it out with space ships and giant walking robots blasting it out in the background. Awesome stuff.

At some point, I became a purist. Fantasy was fantasy and science fiction. I sneered at an aquantance’s D&D campaign that featured knights wearing powered space-armor and lasers. Nevermind the fact that I’d had plenty of fun years earlier playing the science-fiction-themed official D&D module, “Expedition to the Barrier Peaks,” or that I still used the totally broken SF-themed psionics rules for 1st edition Advanced D&D. At this point, young Jay Barnson thought he knew everything about everything, and damn it, science fiction was different from fantasy! I resented how the later entries in the Wizardry computer game series (and the early Might & Magic titles) mixed space ships & magic. How silly! Okay, maybe they weren’t handled well, but I was against the principle!

And then I got older. More experienced. Played more games, watched more films, read more fiction both modern and classic. And the voice inside my head finally said, “Screw it.” Probably the same voice that heard Clarke’s Third Law too many times: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” I realized the wall between science fiction and fantasy was a lot thinner than I’d thought. Where had it come from?

The answer is, in part, John W. Campbell. A science fiction author to who took the helm of Astounding Stories (formerly Astounding Stories of Super Science) in 1938, changed its name to Astounding Science Fiction, and emphasized science-driven stories as opposed to pulp adventure stories with vaguely scientific rationale to make the plot work. This wasn’t entirely a new approach. That wasn’t too dissimilar to Hugo Gernsback’s approach with launching Amazing Stories more than a decade before. Interestingly enough, by this point, this marketing decision set Astounding Science Fiction apart from Amazing Stories, which was in my perspective the point. Campbell made the focus on harder science stick, in part because he paid top dollar for stories, compared to the rest of the pulp market.

Campbell ran the magazine for a long time afterward, eventually dropping the “Astounding” and rebranding it “Analog,” the name by which it is known today. But the beginning of his tenure marked what is frequently called the “Golden Age of Science Fiction.” This all came at the right time, as the severe belt-tightening of the Great Depression came to a close, and the specter of World War II arose. People were desperate for an inexpensive escape, and pulp adventures filled the bill nicely. The relative optimism of science fiction of the era didn’t hurt. The idea that men with screwdrivers could engineer solutions to seemingly insurmountable evils as well as any hard-hitting action hero was refreshing and welcome. Campbell’s marketing focus came at a good time. Science fiction grew in popularity, and other magazines sprang up emphasizing science fiction with various levels of Campbellian “hardness.”

It is my belief that this exerted a pretty strong influence over the writing community. As a writer, you need to maximize your chances of both making a sale and selling to the highest-paying markets. It’s how you put food on the table. Since the “slicks” rarely purchased stories with unrealistic elements, your best bet would be to target Astounding and to try and meet Campbell’s standards. Even if you were rejected, you could then submit elsewhere. Amazing Stories might still publish something that felt like an Astounding story, but the converse was not true. So the “Golden Age” erected a wall between “Science Fiction” and everything else. If you didn’t meet Campbell’s standards, not only was your story not Astounding material, but it might not even *gasp* be science fiction at all! Oh, noes!

That didn’t stop Planet Stories or Amazing Stories from publishing all kinds of character-driven tales of space princesses and heroic derring-do throughout the solar system and galaxy at large, or calling it science fiction. So it wasn’t a universal change. Snobbish readers referred to these “other” stories as “Space Opera,” hoping to smear it with association to “Soap Operas” and “Horse Operas,” but today the description has lost most of its negative connotation. So there. The assumption persists that the harder SF of Campbell’s tenure was superior and more “mature” than that of the earlier or competing pulps.

At once point, the assumption was almost uncontested, but there’s vocal disagreement today. But that’s only by the people who actually read those older stories…

But that’s primarily where the modern division between science fiction and fantasy came from. The “Golden Age” was a golden wall. Was it a good thing? I’m not sure. For me, I think it was a good thing insofar as it gave a boost to “hard” science fiction, yet remained porous and easily crossed. Where it caused the snobbishness and this idea that fantasy chocolate and science-fiction peanut butter should never be mixed, maybe it wasn’t so great. For my part, most of the science fiction I’ve read came after Campbell began his reign, and there’s a lot I love. Some of that might never have been written had Campbell not encouraged it through his high bounty on hard SF.

But then, what is “hard” SF? What qualifies? Honestly, a lot of the stuff that seemed pretty hard back in the day and tied into then-modern theories of how the universe worked come off as being pretty bizarre and fantastic today. A lot of the stuff written in the mid-20th century is alternate history today, dealing with timelines that never came to pass, theories long disproven, and mixing antiquated technology with things that still don’t exist. Even Andy Weir’s “The Martian,” a recent classic of hard science fiction that has enjoyed well-deserved mass-market popularity, is starting to feel a little quaint with the latest science and technology. When I was a kid, planets were thought to be rare, and dinosaurs didn’t have feathers. Science is a journey and methodology, not a destination. This makes it ripe for imaginative stories, but not so great for hard divisions between it and fantasy.

But I’m all for fuzzy, blurred lines, inviting all kinds of variety across the spectrum by virtue of their existence. I don’t want to argue about whether Star Trek: The Next Generation‘s godlike Q or premise of “we’ve evolved past needing money” is more or less fantastical than the Jedi and the really strange size / distance scales of Star Wars. I don’t think The Martian or Interstellar are inherently superior to Guardians of the Galaxy or Wonder Woman by virtue their scientific plausibility. I want stories in the middle and at the extremes.

And yeah, I’m okay with D&D games with powered battle-armor, and with the Dark Savant orbiting a fantasy world in a space ship. It’s all good fun.

Filed Under: Books, Dice & Paper, Retro – Comments:

top

source http://reposts.ciathyza.com/the-golden-wall-of-science-fiction/

1 note

·

View note