#giorgio bertone

Text

Still swinging at 60 Iso Grifo A3/L Prototype, 1963, by Bertone. Designed by a young Giorgio Giugiaro while he was working at Bertone, the Grifo borrowed its engine from the Corvette. Iso’s business was founded on refrigerators, motor cycles and later, in the 1950s on the 236-cc Isetta bubble car. However Renzo Rivolta, founder and CEO of Iso S.p.A had ambitions and saw potential in combining American muscle with Italian stying. The Grifo went into production in 1965 and remained on sale until Iso's demise in 1974. The company was reformed and in collaboration with Zagato produced a special edition of 19 Iso Rivolta GTZ cars in 2021

243 notes

·

View notes

Text

1970 Alfa Romeo GT 1300 Junior (captured by the highly talented Alejandro aka Alex Berlinetta of carphiles, who also has a story about my car on his site)

#alfa romeo#Alfa Romeo GT 1300 Junior#bertone#giorgio giugiaro#hamburg#streetfightingcars#alfaromeole#autolandish#street fighting cars#carphiles

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Siata 208 CS ( 1 of 6).

Societá Italiana Auto Trasformazioni Accessori (SIATA) created a marvelous assortment of machinery in its 45-year history under the guidance of the Ambrosini family. Founded by Giorgio Ambrosini in 1926, Siata specialized in performance modifications for Fiats, creating the overhead-valve conversions, multi-speed gearboxes, superchargers, and multi-carb intakes that competitive Italians wanted for their diminutive cars. The Italian auto giant conspicuously ignored—with few exceptions—the high-performance market as the Agnellis concentrated their empire around sensible, reliable, and mass-produced cars of small proportions.Siata received substantial financial assistance from Fiat following the Second World War, and by 1949 they were producing small automobiles which wore custom, house-labeled coachwork. Firmly grafted to Fiat and its engineering, Siata took a giant leap forward with the arrival of Rudolf Hruska in 1950. Hruska had worked in Porsche’s design office before the war and later collaborated with Carlo Abarth on Piero Dusio’s Cisitalia Grand Prix project. Fiat itself plotted its re-entry to the top ranks of Italian performance automobiles in 1950 with the introduction of their two-liter V-8 (dubbed "Otto Vu"), whose development was entrusted to Siata and executed in total secrecy by Hruska’s team.

The unusual oversquare, 70-degree V-8 engine featured all-aluminum castings with wedge-shaped combustion chambers. Induction was through a pair of dual-throat, downdraft Weber carburetors. With its high-revving short-stroke design and 8.5:1 compression ratio, prodigious power was channeled through a four-speed manual gearbox. Hruska planted the engine into a tubular chassis, and this became the basis of Fiat’s 8V.

Debuting at the 1952 Geneva Salon, the 8V caused an absolute sensation perhaps best equated to a meltdown of Italy’s motoring press. For many, the Siata-developed, Fiat-badged supercar defied belief. In particular, the advanced chassis featured a fully independent suspension with coil springs and telescopic shock absorbers at all four corners and was a marvelously sophisticated platform for its time, with supple and predictable handling that amazed drivers accustomed to the rigidly sprung, “flex-framed,” live-axle sports cars of the time.

Approximately 200 Tipo 104 engines were made to supply the 114 8V examples which Fiat ultimately produced. Eighty-five or so surplus engines were thusly returned to Siata, which seized the opportunity to supply them with additional house-made upgrades and implant them into the very chassis from which the earth-shattering Otto Vu had been developed.

The resulting Siata 208 CS was available as an attractive barchetta-like Spider or streamlined berlinetta, which Siata commissioned from a small pool of local coachbuilders including Bertone, Vignale, and Stabilimenti Farina. It is said that Siata openly encouraged the carryover of major styling details which these same companies were providing to Ferrari during the same period.

Perhaps the shapeliest design ever rendered upon the 208 CS, however, was executed by Balbo of Turin. Just nine berlinettas were made, of which only six examples are known to remain extant.

251 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chef Berton come in un film di Zalone: «La pasta? In acqua per 45 minuti: al dente!»

Chef Berton come in un film di Zalone: «La pasta? In acqua per 45 minuti: al dente!»

Andrea Berton, una stella Michelin al ristorante che porta il suo nome in Porta Nuova Varesine, a Milano, approva la cottura passiva della pasta, portata alla ribalta del nobel per la Fisica Giorgio Parisi.

source

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Edoardo Sanguineti, Negli ultimi suoi tempi, [Convegno nazionale di studi su Italo Calvino, Sanremo, November 28-29, 1986, then in ‘Italo Calvino. La letteratura, la scienza, la città’, Edited by Giorgio Bertone, Marietti, Genova, 1988]; in «Riga» 9, ‘Italo Calvino. Enciclopedia: arte, scienza e letteratura‘, Edited by Marco Belpoliti, Marcos y Marcos, Milano, 1995, p. 13

#graphic design#conference#poetry#book#magazine#edoardo sanguineti#italo calvino#giorgio bertone#marco belpoliti#riga#marietti#marcos y marcos#1980s#1990s

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alfa Romeo Art

Clockwise from center: 1931 8C 2300 corto spider Zagato, 8C 2900 B berlinetta Speciale Le Mans Touring, 1954 2000 Sportiva Bertone (grey coupé), 1954 1900 Sport spider Bertone (green), 1958 Abarth Alfa Romeo 1000 coupé Bertone, 1953 6C 3000 CM coupé Colli and 6C 3000 CM spider Merano Colli.

by Giorgio Alisi

#Alfa Romeo#Giorgio Alisi#Art#Artwork#drawing#Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 corto spider Zagato#Alfa Romeo 8C 2900 B berlinetta Speciale Le Mans Touring#Alfa Romeo 2000 Sportiva Bertone#Alfa Romeo 1900 Sport Spider#Abarth Alfa Romeo 1000 coupé Bertone#Alfa Romeo 6C 3000 CM coupé Colli#Alfa Romeo 6C 3000 CM spider Merano Colli#Abarth#Bertone#Carrozzeria Bertone#Colli#Carrozzeria Colli#Touring#Carrozzeria Touring#Zagato#Carrozzeria Zagato#Franco Scaglione#Scaglione

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

La Révolution Surréaliste - n° 8 - deuxième année 1 décembre 1926

BRETON André: directeur

Published by 1926 Paris librairie GALLIMARD, 1926

La Révolution surréaliste (English: The Surrealist Revolution) was a publication by the Surrealists in Paris. Twelve issues were published between 1924 and 1929.

Shortly after releasing the first Surrealist Manifesto, André Breton published the inaugural issue of La Révolution surréaliste on December 1, 1924.

Pierre Naville and Benjamin Péret were the initial directors of the publication and modeled the format of the journal on the conservative scientific review La Nature. The format was deceiving, and to the Surrealists' delight, La Révolution surréaliste was consistently scandalous and revolutionary. The journal focused on writing with most pages densely packed with columns of text, but also included reproductions of art, among them works by Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, André Masson and Man Ray.

Selected issues

Issue 1 (December 1924): The cover of the initial issue announced the revolutionary agenda of La Révolution surréaliste with, "It is necessary to start work on a new declaration of the rights of man."

Berton and surrealists in

La Révolution surréaliste

(1 Dec. 1924).

In a mock scientific fashion the journal explored issues related to the darker sides of the human psyche with articles focused on violence, death and suicide. Detached descriptions of violent crime taken from police reports, and an impartial survey on suicide were included. One spread featured Germaine Berton, recently acquitted of murder, surrounded by male surrealists.

Issue 3 (15 April 1925): The third issues was overseen by writer and actor Antonin Artaud.[1]:60 The cover of the third issue announced, "End of the Christian Era." Inside articles convey a blasphemous and anticlerical tone. Artaud wrote an open letter, "Address to the Pope," that expressed the revolt against what Surrealists saw as oppressive religious values:

The world is the soul's abyss, warped Pope, Pope foreign to the soul. Let us swim in our own bodies, leave our souls within our souls; we have no need of your knife-blade of enlightenment.

Such anticlerical remarks are found throughout and reflect the group's relentless campaign against oppression and bourgeois morality.

Issue 4: Breton announced in the fourth issue that he was taking over the publication. His concern about disruptive factions that had developed in the Surrealist group brought him to assert his power and restate the Surrealist principles as he conceived them.

Thereafter, each issue became more political with articles and declarations that have a Communist slant.

Issue 8 (December 1926): The growing fascination with sexual perversion is revealed in an article by Paul Éluard which celebrates the writings of the Marquis de Sade, who was imprisoned for much of his life because of his deviant writings about sexual cruelty. According to Éluard, the Marquis "wished to give back to civilized man the strength of his primitive instincts." Writing and imagery, influenced by de Sade, by Breton, Man Ray, and Salvador Dalí was also included.[2]

Issues 9 and 10 (October 1927): Introduce Exquisite corpse (Le Cadavre exquis)—a game the Surrealists enjoyed that involves folding a sheet of paper so that several people contribute to the drawing of a figure or writing text without seeing the preceding portions. The issue includes some exquisite corpse results.

Issue 11 (): The interest in sex continues in the eleventh issue with "Research into Sexuality," an account of a debate that took place in January 1928. In the frank discussion, more than a dozen Surrealists openly expressed their opinions on sexual matters, including a variety of perversions.[3]

Issue 12 (December 1929): Contains Breton's Second Surrealist Manifesto. The declaration marks the end of the group's most cohesive and focused years, and signals the start of disagreements within the group. Breton celebrated his faithful supporters, and denounced those who had defected and betrayed his doctrine. Also contains the full script of Un Chien Andalou with Luis Buñuel's preface.[4]

#La Révolution Surréaliste#André Breton#1926#Paris#Librairie Gallimard#Books#The Surrealist Revolution

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Giulia Sprint GTA (Gran Turismo Alleggerita) was designed by Giorgio Giurgiaro for Bertone, its production started in 1965❗❤️🍀 https://www.instagram.com/p/B-wUvGQl3OR/?igshid=wfl10yvj99xb

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 libri per lettori navigatori

8 libri per lettori navigatori

a cura de Il verbo leggere

Salite a bordo e spiegate le vele dell’immaginazione: oggi voglio presentarvi otto letture intrise di salsedine. Vista la mia predilezione per la Age of Sail, era inevitabile che, prima o poi, finissi col proporvi un post dedicato alla letteratura marinaresca. Se anche voi amate solcare oceani d’inchiostro e vi sapete destreggiare tra ufficiali stressati e pirati…

View On WordPress

#Age of sail#barca#Bjorn Larsson#Coleridge#crociera#Giorgio Bertone#Il verbo leggere#mare#marinai#Maugham#nave#navigare#pirati#vecchio marinaio#vela#William Golding

0 notes

Text

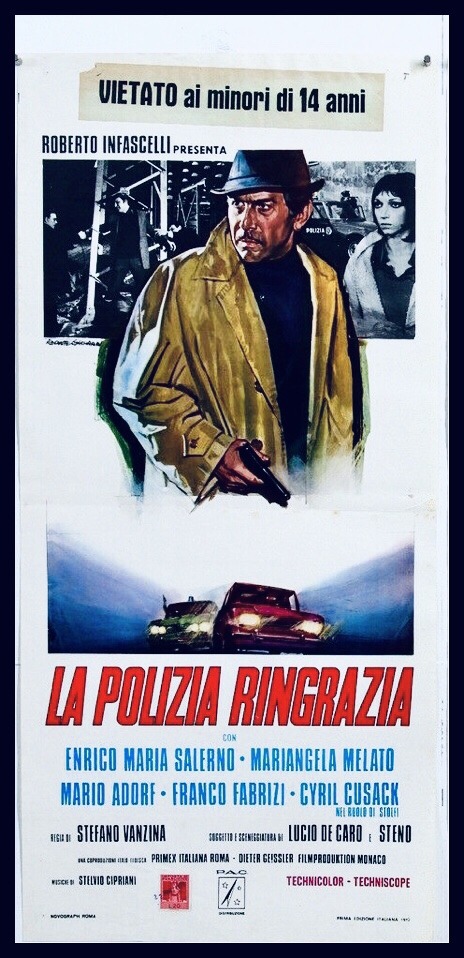

La Polizia Ringrazia

Direct by STENO (STEFANO VANZINA)

Data di uscita: 25 febbraio 1972

Paese di produzione: Italia, Germania Ovest

Musica composta da: Stelvio Cipriani

Scritto da: Steno, Lucio De Caro

Curiosità

In questo e nel successivo film drammatico con Alberto Sordi, Anastasia mio fratello, il regista si firma con il suo vero nome, Stefano Vanzina, poiché lo pseudonimo Steno era troppo legato alla commedia.

L'incasso totale è stato di 1.696.360.000 di lire dell'epoca, ed è stato visto all'epoca da circa 4.162.847 spettatori al cinema.

Premi

1972 - Festival Internazionale del Cinema di San Sebastián

Concha de Plata - Stefano Vanzina

Interpreti e personaggi

Enrico Maria Salerno: commissario Bertone

Mariangela Melato: Sandra

Mario Adorf: sostituto procuratore Ricciuti

Cyril Cusack: ex questore Stolfi

Franco Fabrizi: Francesco Bettarini

Laura Belli: Annamaria Sprovieri

Jürgen Drews: Michele Settecamini

Ezio Sancrotti: vice commissario Santalamenti

Corrado Gaipa: avvocato Armani

Giorgio Piazza: ministro dell'Interno

Piero Tiberi: Mario Staderini

Diego Reggente: giornalista

Ada Pometti: sorella di Staderini

#la polizia ringrazia#mariangela melato#enrico maria salerno#mario adorf#steno#steno vanzina#stefano vanzina#poliziottesco soundtrack#italian poliziottesco#poliziottesco#poliziotteschi#italian crime movie#giallo fever#giallofever#italian cult#italian giallo#cinema cult#cult#italian sexy comedy#gialli#international cult#giallo

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Our view from Rifugio Giorgio Bertone on the Tour du Mont Blanc. https://ift.tt/2nvYec7 Find out About our Partner's $1800 Dollar Full Expense Paid Trip for 2 to Sri Lanka, Egypt, Thailand, or Spain!

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fiat Abarth 131 Prototype SE031, 1975, by Bertone. Designed as a replacement for the successful 124 Spider rally cars, the car was powered by an Abarth modified Dino V6 from the Fiat 130 enlarged to 3.5 litres driving through a transaxle 5-speed gearbox. Driven by Giorgio Pianta and Bruno Scabin the 131 won the 1975 “Giro d’Italia”.

119 notes

·

View notes

Photo

… una ventana! Mitad del camino! (at Rifugio Giorgio Bertone) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cg6G10WNQPB/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

VENERDI’ 8 GIUGNO ALLE ORE 20.45 ALLA LIUC, UN ALPINISMO IRRIPETIBILE

Venerdì 8 Giugno alle ore 20.45 all’Aula Magna della LIC-Università Cattaneo il CAI – Sezione di Castellanza, con il patrocinio dell’Assessorato alla Cultura della Città di Castellanza, propone una serata dedicata agli amanti della montagna sul tema “Un alpinismo irripetibile”, dedicata alla prima salita invernale integrale della cresta del Peutérey (Monte Bianco) nel dicembre 1972 e ad altre importanti ascensioni invernali fatte dai fratelli Arturo e Oreste Squinobal, guide alpine di Gressoney.

La cresta integrale di Peutérey è un continuo susseguirsi di salite e discese “complicate”, da ogni punto di vista alpinistico le si voglia considerare.

Con otto chilometri di sviluppo è la più lunga cresta delle Alpi, il dislivello tra il punto di partenza e l’arrivo in vetta al Monte Bianco è di 3400 metri, ma per gli alpinisti, considerando i continui saliscendi, corrisponde a circa 5000 metri.

La prima ascensione integrale della cresta di Peutérey è stata realizzata nell’estate del 1953, poi fino agli anni 70 seguirono poche ripetizioni in estate e alcuni tentativi, falliti, di scalare la cresta in inverno.

Nel dicembre del 1972 la cresta venne scalata per la prima volta in inverno dai fratelli Arturo e Oreste Squinobal, due giovani guide alpine di Gressoney i quali, con pochi mezzi e tanto talento, riuscirono a portare a termine l’impresa, realizzando prima salita integrale della Peutérey.

I fratelli Squinobal dopo un primo tentativo, causa le condizioni meteo avverse, furono respinti dalla montagna, tornarono a casa e il giorno successivo, con le condizioni meteo in miglioramento, ritornarono alla base della Aiguille Noire di Peutérey, raggiunsero la vetta quindi con innumerevoli “doppie” si calarono nel baratro del lato opposto, fino alla base delle Les Dames Anglaises.

In quel punto, inaspettatamente, raggiunsero una cordata di quattro, altrettanto forti, alpinisti francesi che avevano lo stesso obiettivo dei due gressonary, ovvero, compiere la prima salita invernale integrale della cresta di Peutérey. Alla guida dei quattro alpinisti d’oltralpe c’era Yannick Seigneur.

Sebbene Arturo e Oreste fossero più veloci, non esitarono a rimanere con i francesi: insieme a loro salirono la cresta fino in vetta al Monte Bianco e con loro condivisero il successo dell’impresa.

Un atteggiamento altruista, responsabile e meritorio quello dei fratelli Squinobal, che testimonia la loro bontà d’animo, l’umiltà e il reale disinteresse a volere emergere individualmente ad ogni costo. Una dimostrazione che la montagna e l’alpinismo, anche di alto livello, possono significare amicizia.

Questa salita per Arturo e Oreste non fu certo l’unica: altrettante importanti prime ascensioni furono compiute tra i primi anni 70 e la fine degli anni 80. Ricordiamo le più significative: dicembre 1971 prima salita invernale della parete sud del Cervino; gennaio 1978 prima salita invernale della parete ovest del Cervino; maggio 1982, Arturo e Oreste facevano parte della spedizione delle Guide Alpine valdostane al Kangchendzonga 8598 m (Himalaya), la terza vetta della terra. Oreste senza l’ausilio del respiratore (ossigeno) arrivò in vetta, realizzando la prima salita italiana.

L’attività alpinistica invernale sulle Alpi dei fratelli Arturo e Oreste Squinobal si sviluppa tra il finire degli anni 60 fino agli anni 80 e coincide con l’attività alpinistica praticata dai più forti alpinisti di quel periodo: Walter Bonatti, Alessandro Gogna, i fratelli Antonio e Gianni Rusconi (di Valmadrera) René Desmaison, Renato Casarotto, Giorgio Bertone, Gian Carlo Grassi e tanti altri che hanno scritto la storia dell’alpinismo mondiale.

Le salite invernali rappresentavano (e rappresentano) il modo più complicato di praticare l’alpinismo in alta montagna, per una serie di situazioni oggettive: il freddo, le perturbazioni (allora non prevedibili con la precisione delle previsioni meteo attuali), il maggiore rischio di slavine, e il “ghiaccio vetrato” che ricopre le creste e le pareti rocciose. La pratica dell’alpinismo in inverno ha sempre complicato le ascensioni agli alpinisti, in modo ancor più accentuato quando si trattava compiere le prime salite.

E allora perché Arturo e Oreste si spinsero anche nella pratica dell’alpinismo invernale? e ancora, perché cercarono di praticarlo su montagne difficili mai salite in inverno? come nel dicembre del 1972 quando salirono per primi sulla parete sud del Cervino, che ancora rappresentava uno dei problemi irrisolti dell’alpinismo mondiale.

Ebbene, a queste domande Arturo e Oreste rispondevano in modo essenziale e solo apparentemente semplice: “perché non provare”. Insita nella risposta c’era tanta consapevolezza e nasceva da attente valutazioni: di ordine pratico, relative alle caratteristiche della montagna che dovevano affrontare e al loro grado di reale preparazione, e di ordine intellettuale, con una “visione romantica del fare alpinismo”. Ad esempio Arturo e Oreste ritenevano che non avrebbero avuto nulla da perdere se avessero tentato una prima ascensione, non avrebbero dovuto rendere conto ad alcun soggetto, né in vetta né al ritorno, non agli sponsor, non al pubblico, né ai critici e forse neppure al mondo accademico.

Dovevano e volevano condividere la salita con loro stessi o molto liberamente con altri alpinisti, non certamente per egoismo ma piuttosto perché erano nella condizione di poterlo fare. Bastavano a se stessi.

Sebbene fossero Guide Alpine, per Arturo e Oreste fare gli alpinisti, seppur ad alto livello, non era la loro attività principale. Loro erano artigiani falegnami a tempo pieno e lavoravano in proprio nel laboratorio sotto la loro abitazione a Gressoney Saint Jean.

I successi alpinistici di Arturo e Oreste non furono determinati dal caso o dalla fortuna, non erano degli incoscienti, irresponsabili e sprezzanti del pericolo. Ad ogni loro ascensione corrispondeva una puntuale preparazione svolta con duri allenamenti, sempre in costante ascesa al fine di aumentare la resistenza e affinare le tecniche alpinistiche ed avevano una palestra naturale a loro disposizione: il Monte Rosa, in tutte le stagioni.

Interverranno alla serata Arturo Squinobal (guida alpina) ed Enrico Martinet (giornalista della redazione di Aosta del quotidiano La Stampa)

Ingresso libero.

0 notes

Text

Italia necesita una dosis de capitalismo Bugatti, por Mises Hispano.

Hay una revulsión intelectual y emocional y peculiar al leer acerca del ciclo de males económicos y políticos inacabable de Italia: ya sea en relación con la cercanía al colapso en del banco más antiguo del mundo o con la efectiva parálisis nacional de la industria italiana. A pesar de este estado de cosas casi permanente, el abrumador legado cultural del país sigue evocando tanta admiración que persiste una idea metafísica de Italia completamente distinta de la realidad a ras de suelo del circo máximo de Roma de autodegradación diaria.

Sin embargo, si hay un patrón histórico por el que la Italia contemporánea podría reavivar su potencial de riqueza, su excelencia industrial y su moral empresarial, no hace falta remontarse a la visión de la edad dorada de las ciudades-estados: bastaría con remontarse al siglo XX. Porque fue durante el último siglo cuando floreció un ideal renacentista del individualista visionario e inventor-esteta entre turbulencias ideológicas, guerras mundiales, dictaduras, violencia civil, terrorismo comunista, estancamiento económico y arredora corrupción que sufre el país durante sus décadas de modernización: la del fabricante italiano de automóviles de lujo. La generación que produce gente como Ettore Bugatti, Enzo Ferrari, Battista Pininfarina, Ferrucio Lamborghini y (en momentos posteriores) ingenieros-diseñadores como Niccolo Bertone, Leonardo Fioravanti y Giorgio Giugietto fue posiblemente la que salvó al país de sí mismo durante aquellos años turbulentos (por no mencionar el gran experimento de masas del modelo Fiat). Una ola novedosa de esos expertos capitalistas de gama alta es lo más importante que necesita hoy Italia.

El genio italiano ha sido siempre la “hermosa fusión” de arte y de ingeniería. Como sus antepasados renacentistas, los grandes fabricantes italianos de automóviles fueron en buena medida autodidactas, construyendo sus vehículos prácticamente a mano; poseían distintos talentos dentro de un solo enfoque, no estaban en absoluto dispuestos a renunciar y perseguían sus visiones respectivas con poca preocupación por las “circunstancias” o el “entorno político”, a pesar de las arengas de Mussolini. Por encima de todo, eran nombres con un carácter notable, aunando un obstinado orgullo con una tranquila contención, el celo visionario con la visión de los grandes negocios y el pragmatismo en los elementos básicos. Amaban su trabajo, llegando a rechazar vender a un potencial cliente si no era “suficientemente bueno” para sus automóviles, ¡y esto en una Italia devastada por dos guerras!

La personalidad clave en esto es el milanés Ettore Arco Isidore Bugatti. En lo que se podría calificar como “capitalismo Bugatti”, es el que mejor caracteriza a una generación de extraordinaria inventiva y pericia tecnológica innovadora que cambió el curso de la industria italiana, y esto no se limita los automóviles, sin que se extiende a sectores como el ferroviario y el diseño de trenes, la aviación, el equipamiento militar y los electrodomésticos comerciales. Bugatti no tuvo ninguna formación formal como ingeniero sino que se apoyó en su firme voluntad y confianza en sí mismo, sin que le importaran algunos de los grandes fracasos que sufrió. Se refería a todos sus diseños como “pur sang” o “pura sangres”, reflejando la consideración que tenía por su trabajo.

Su primer vehículo, un triciclo motorizado movido por los motores, promovió la inversión en el joven ingeniero por parte de un patrocinador aristocrático y luego invitaciones de fábricas automovilísticas alemanas para las que Bugatti trabajó intermitentemente durante la Primera Guerra Mundial. En su tiempo libre, empezó a trabajar con vehículos ligeros en su sótano y posteriormente continuó por sí solo en su garaje donde completó su primer automóvil real, el Bugatti T13 (1922), un descapotable que llegó a los 950.000$ en una subasta el año pasado. En poco más de diez años produjo creaciones tan espectaculares como el Bugatti Type 41 Royale (1926–1933), el icónico Type 50 Superprofilée (1931–1933) y el Type 55 Super-sport Roadster (mismos años) y, diseñando por su talentoso hijo Jean, la fenomenal serie Type 57 (1935–1937), incluyendo el Atalante (sin alerón) y el 57SC Atlantic (con alerón), del último de los cuales sólo quedan dos la tierra: uno de ellos se vendió por 30 millones de dólares en 2003.

Bugatti fue también un incansable inventor, diseñando automóviles eléctricos, equipos cinematográficos, un horno portátil, una caña de pescar movida por electricidad, un limpiasuelos autónomo, una cinta transportadora “perpetua”, un sistema de calefacción de máquinas herramientas, un generador de viento, un torpedo y una máquina fabricante de pasta a partir de recambios dispersos de automóvil. Otros diseños fueron para barcos, aviones y ferrocarriles. A Bugatti nunca le faltaron recursos. Establecido en Molsheim, en Alsacia (a veces Alemania, a veces Francia), su primer tren tenía que ir de la fábrica de Molsheim a la estación local de trenes. Como no había conexión ferroviaria debido a la guerra, los raíles se fueron incorporando a lo largo del viaje. Se ponían delante del tren y, una vez que había pasado por encima de ellos, se ponían de nuevo al frente.

Bugatti amaba sus automóviles y (desafiando lo que las circunstancias bélicas podrían haber dictado en caso contrario) seleccionaba a sus clientes de acuerdo con ello. Rechazó vender un automóvil al rey Zog de Albania debido, según dice la leyenda, a que Su Majestad demostró mala educación en la mesa. Otro cliente informó con enfado a Il Maestro es su motor no arrancaba adecuadamente en invierno; Bugatti le dijo al hombre que si podía permitirse un Bugatti podría permitirse un garaje con calefacción. Su filosofía podría resumirse una declaración que hizo en una entrevista: “Construyo los automóviles que me gustan. Si alguien quiere comprar uno, podemos ver cómo hacerlo”.

La misma ambición obstinada afectaba a los demás grandes fabricantes de automóviles de su generación, que casi inevitablemente empezaban con pocas perspectivas, poco o ningún contacto con la industria y en una situación de empobrecimiento por la época de guerra. Enzo Ferrari empezó como herrero asignado al herrado de mulas para el ejército italiano; su padre y su hermano habían muerto durante la epidemia de gripe de la Primera Guerra Mundial; la empresa metalúrgica familiar también se había venido abajo. Hoy ciertos modelos de Ferrari son tan valiosos que un Ferrari 250 GTO de 1963 (uno de los solo 39 fabricados) se vendió recientemente por 52 millones de dólares, mientras que el Ferrari 275 GTB que pertenecía al actor Steve McQueen se vendió por 10 millones.

Ferrucio Lamborghini nació en 1916 en una familia pobre de viticultores y creó una empresa constructora de tractores durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial que le hizo muy rico. Tenía cerca de 50 años cuando inauguró Automobili Ferruccio Lamborghini, prometiendo construir el mejor coche deportivo de la historia. Considerado como loco por intentar “saltar” al diseño de coches de lujo y según se dice despreciado por Enzo Ferrari, que le llamaba “ese granjero” que no llegaría a ninguna parte, su primer automóvil fue su primera obra maestra y fue calificado como “alucinante” en la exposición del motor de Turín de 1963. Era el 350 GTV, reconocido como una obra de arte de doce cilindros. Prácticamente todos sus automóviles desde entonces ha sido también obras de arte.

Battista “Pinin” Farina, nacido en 1893, empezó a trabajar con once años en el taller de chapa y pintura de su hermano en Turín y con dieciocho años estaba diseñando radiadores para Fiat. En 1920 fue a Estados Unidos para ver las grandes innovaciones en Detroit, conociendo a Henry Ford, que le pidió que se quedara y trabajara para él. Declinó la oferta, pero posteriormente atribuyó a su visita estadounidense su entusiasmo por la empresa privada. Pininfarina, como iba a llamarse su empresa, fue una de las grandes diseñadoras de carrocerías para las principales empresas automovilísticas del momento, incluyendo Ferrari, Maserati y Bentley. Sus obras no son menos asombrosas que las de sus pares más famosos: el CisItalia 202 Gran Sport (1947) de Pininfarina, definido como una “escultura móvil” es el único automóvil que se expone permanentemente en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York.

Verdaderamente, puede haber esperanza para el futuro. Hoy el sector del diseño automovilístico italiano con base en Turón es el secreto mejor guardado del emprendimiento italianos, con ingenieros estrellas creando nuevas factoría antes muy buscadas por el sector automovilístico alemán y japonés. El mercado global del diseño independiente de automóviles supone entre 3 y 5 mil millones de dólares. Si Italia obtuviera todo lo posible de estos grandes recursos creativos, atrapada como sigue por la incompetencia estatal y la burocracia castradora de iniciativas, realmente no hay manera de decir hasta dónde puede llegar este país, como merece tanto como motor de su propia recuperación y el diseñador de de un futuro próspero.

El artículo original se encuentra aquí.

de Instituto Mises http://ift.tt/2jhiafm

http://ift.tt/2j3ZMJi

de nuestro WordPress http://ift.tt/2iE3W7L

Difundimos las ideas liberales, libertarias, minarquistas y anarcocapitalistas. http://ift.tt/2j3ZMJi January 11, 2017 at 07:01AM

0 notes

Photo

Siata Daina Gran Sport type A barchetta - 1952 by Perico001 Societa Italiana Auto Trasformazioni Accessori Coachwork by Stabilimenti Farina Chassis no. SLO216 Founded in 1926 in Turin, Italy by Giorgio Ambrosini, SIATA (Societa Italiana Auto Trasformazioni Accessori) began life as a tuning firm specialising in the modification of FIATs. When the company, now renamed SIATA Auto SpA, eventually introduced its first production car in 1949, FIAT components, in this case sourced from the Topolino, were the logical choice for the new Amica cabriolet. During the 1950s and on into the '60s, a variety of US engines including Crosley, Ford and Chrysler V8s was adopted in addition to FIAT's home-grown motors. The Torinese firm's next effort, based on the FIAT 1400, was the Rallye, a traditionally styled roadster bearing more than a passing resemblance to the MG TD. Not all SIATA's designs were so obviously plagiarised, the series of FIAT 8V 2.0-litre V8-powered coupés of the 1950s, equipped with a variety of stylish Italian coachwork from the likes of Stabilimenti Farina, Vignale and Bertone and arguably the firm's finest creations, being particularly striking. We should also mention the similarly powered 208C Spyder - sister car of the Gran Sport – made famous by such owners as Steve McQueen, who dubbed his 'my little Ferrari'. SIATA's Daina model of the early 1950s was based on the FIAT 1400 and built in both Convertible and Coupé forms, most of the former being bodied by Stabilimenti Farina and the latter by Bertone. Later cars were designated 'SL' Scatolato Lamiera – literally: sheet metal box). The Daina used the FIAT 1400 overhead-valve engine, modified by SIATA with a special cylinder head, pistons, and twin-carburettor inlet manifold. A 1,500cc unit was available as an option. SIATA was active in racing from its earliest days, and a Daina Gran Sport driven by Dick Irish and Bob Fergus won its class in the inaugural Sebring 12 Hours race of 1952, finishing 3rd overall ahead of many larger-engined cars. The nimble handling of these cars was highly regarded in the USA, where many were modified to accept larger engines. SIATA was also a regular competitor in the famed Mille Miglia race in Italy. The car offered here is an example of the rare SIATA Daina Gran Sport Type A. The Type A, distinguishable by its front-hinged bonnet and engine sitting over the front wheels, is much less numerous than the Type B, and it is estimated that only eight at most still exist. It is believed that chassis number 'SL0216' was originally sold by SIATA importer Ernie McAfee of Hollywood, California and shipped to Dayton, Ohio by a colonel in the United States Air Force. This is a well-known car with ownership history documented from the early 1980s onwards. It has spent most of its life in the USA, was registered in Germany from late 2006 and is currently registered as '278 YUB' in the UK. The car was probably fitted with a 1,400cc SIATA engine originally (although it is possible that it was supplied without an engine) but this was replaced in the 1950s with a 265ci Chevrolet V8. When sold in 1969, the car had no drive train; by 1972 a 240bhp Ford 302ci V8 had been installed. In 2014, an extensive restoration was carried out by Premium Classic Cars of Sudbourne, Suffolk in preparation for the 2015 Mille Miglia, for which the car was accepted. Works undertaken included returning the drive train and other areas, including the engine bay, to period specification. To this end, engine number 'SL0209' (recorded as an original SIATA unit) was installed, and Borrani wire wheels fitted, painted in gloss black like those of SIATA's original Mille Miglia car. In terms of originality, great efforts were made to restore 'SL0216' as close as possible to original specification. However, the interior, though period, is not entirely original; rather, it has been configured to be comfortable for the Mille Miglia while at the same time incorporating a number of safety features (all as allowed by the Mille Miglia scrutineers). Noteworthy accessories include a rally trip meter, full tonneau, and auxiliary sockets for iPhone, etc. Unfortunately, a water pump failure forced the car to retire from the 2015 Mille Miglia. It was accepted again for the Mille Miglia in 2016, prepared by Century Classics of Hungerford, and this time successfully completed the race. The car is presented today exactly as it finished the last Mille Miglia, still wearing the livery of 2015 and 2016. Nothing has been done to the car since the 2016 Mille Miglia, other than repairing the brake master cylinder to overcome the only problem affecting it during that event. The car will come with a spare water pump (the weak point that eliminated it from the 2015 Mille Miglia). Accompanying documentation consists of a current MoT certificate, UK V5C Registration Certificate, FIVA papers, and a full photographic record of the restoration. From arguably the most evocative period of post-war sports car racing, this ultra-rare SIATA has been much admired at the Mille Miglia and has the potential for further development. Opportunities to acquire strong, Mille Miglia-eligible cars are increasingly rare, particularly when they are in recently restored condition like this one. Les Grandes Marques du Monde au Grand Palais Bonhams Estimated : € 280.000 - 380.000 Parijs - Paris Frankrijk - France February 2017 https://flic.kr/p/RY3pkg

1 note

·

View note