#grapska

Text

Blood and Honey: An Interview with Dr. Danica Anderson on Healing for Women War Trauma Survivors

Danica Anderson reading coffee grounds (tasseography) in Ahmica-Vitez, Bosnia

On a quest to connect my grandmother and Zejna, the Bosnian refugee we sponsored together in the 90s—I am sure not by accident—I discovered the work of Dr. Danica Anderson, author of Blood and Honey: The Secret Herstory of Women, South Slavic Women's Experiences in a World of Modern-day Territorial Warfare. In this book, she explores war trauma experienced by women during the Balkan War. Through recipes, and cultural customs, Blood and Honey is a book of spells for these women to heal themselves through bioculinary* arts and biosemiotic** communication. In this beautiful interview, she brings me closer to Zejna and my grandmother, and reveals woman-centric secrets to understanding the rhythms of our subconscious. From coffee readings, to Marija Gimbutas you will love the magic, mystery and healing of this interview!

* Inscribed social memory working collectively with agriculture, herbs, food crops, animal husbandry to bee keeping that preserve South Slavic ancient Neolithic Practices.

** (from the Greek bios meaning "life" and semeion meaning "sign") is a growing field of semiotics and biology that studies the production and interpretation of signs and codes in the biological realm.

First, I would like to ask how your family's trauma from former Yugoslavia was manifest in your life in Chicago. You mentioned that your mother didn't want to speak of it. Was silence part of the intergenerational trauma?

The killing silences are transgenerational in that the silences are passed to future generations. My mother was indoctrinated into killing silences by her mother and grandmother both who lived through world wars in former Yugoslavia. It was not until her late 80’s that my mother spoke of her WWII concentration camp experience to her granddaughter. I don’t think she had the words previously due to shame and guilt that was not hers.

The way trauma ebbed and flowed in my childhood was seen with domestic violence and child abuse. I have early memories, which children who survive child abuse often have. Although the child or infant is preverbal, these memories are stored in the body and often unable to be given a vocabulary until the child’s development of language. This is how children are not aware their lives are violent and instead think it is normal. With the mother submissive and beaten into the killing silences where she has no one to tell, the child cannot gain a vocabulary for the trauma. Instead the killing silences are epigenetic (we are shaped by environment that influences our genome,) thus transgenerational trauma.

You also talk about the women in your Serb community and their bioculinary traditions and ethno-dance traditions, which were both healing, and the foundation of your book's philosophy. Can you describe how these traditions manifest away from one's country of origin? Did your family grow their own food, for instance?

To describe how oral memory traditions capacity for the transmission of human memory is best done when we realize it has been done with a cast of thousands of generations and continues to this day no matter where the geographic location. We are talking about millions upon millions of actors taking up their role in performing the enactment of memory-lived life experiences of our ancestors without external aid meaning no books, scripts to read from, youtube or modern day manuals. If anything, the oral memory traditions are exactly the data needed for study in long term memory and transmission of memory over the Ages with such a vast pool of actors.

What I have observed in the diaspora of not just the South Slavs, but all diverse groups of people is how they reach for their human memory storage triggered by geographic relocation. In one way this is how travelers experience their journeys, a triggering of human memory in their lineage of ancestors’ life experiences. The culture and corresponding oral memory traditions (a ritual science) contain the way of life and the adaptations to the environment. Fleeing the violence and aftermath of war, my parents immigrated through Ellis Island to Chicago. They brought with them their way of life. We had a small back yard for the garden of vegetable and plants. My father would trek to the Southside of Chicago to the train station each fall to buy crates of grapes for wine making. A wooden barrel with an iron press in our basement was arranged so that all my siblings and I would pick off the grapes and toss into the sink to wash and then into the barrel. This took days. Once done, since I was the littlest I was placed into the press to squash the grapes. I remember having stained purple feet and legs. My mother made everything from scratch. Her strudel called ‘pita’ was the finest of translucent phyllo dough she stretched over the kitchen table. The kitchen table was where I would crawl under and watch my older siblings dance the kolo (s)- Serbo-Croatian for folk round dance. The food and gardens are bioculinary practices found in oral memory traditions, a ritual science.

I never considered tasseography (tea or coffee readings) as such a powerful way to tap into the protolinguistic self and heal trauma. You describe "storied instructions" through "small acts", meaning, and the construction of new memories over traumas through mindful experience of the everyday. This is an essential aspect of your book, Blood and Honey Icons: Biosemiotics and Bioculinary and it also is incorporated into your trauma recovery work with Bosnian women war survivors. What kinds of transformations do you witness among women who have been subjected to gynocide and sexual trauma?

The small acts are often repeated and done daily or seasonally through thousands of generations into the present generation. The present generation layers over the oral memory traditions with their environment and life experiences. This is an extraordinary transformational process when you realize that what we live, feel and experience both biologically and even psychobiologically is heritable: transgenerational. Basically, how we live and our life experiences has far reaching social, cultural way of life implications.

The way of life for women is targeted by wars and violence for this very reason since we live in a phallocracy where the male dominates. Yet, women are the creators of culture since we are all born of a woman. Her domestic arts and child rearing are critical transgenerational intangible heritage that evolves our relations with our environment embodied with her life experiences. The Bosnian women war crimes and survivors cleaned up after each war that took place over a century. In doing so, her domestic labor and child rearing was one of survival not evolving thus thriving. Transformations were had by the women survivors who no longer could stand the survival mechanisms found in trauma. The critical juncture was ‘to ask do I need to survive or thrive’. What happened in the aftermath of the Balkan War was a return to what their grandmothers did to survive such as the beehived wood ovens, garden, weaving to dancing the round folk dances called kolo (s).

What I am talking about is how the transformations came through when women regained their role as creators of culture and corresponding oral memory traditions- a ritual science containing prehistoric chants, songs, dance to bioculinary and all way of life before the modern conveniences. One Bosnian war survivor stated when she had nothing, she discovered she had everything with her house that had a field of crops and chickens. She said the farmer and those chickens saved humanity thus transforming humanity.

When survivors did not have an oral memory tradition to transform mostly sexual trauma and genocide, I was told to talk with those struggling. In my paper on Slavic Maternal Fright I wrote about a thin Bosnian-Herzegovinian pregnant woman in her late twenties had big dark circles under her eyes; her hands shook even at rest. When she began sharing her maternal fright, she released expressions that were formerly deliberately hidden and avoided. Her fear was that her husband’s loss of 18 family members at the village of Ahmica-Vitez, Bosnia on April 16, 1993 would flood into her fetus. You see story and metaphor heals only if we author our life experiences. Since trauma is primarily about extraordinary experiences in the personal lives of individuals with women and children the majority facing such impossible circumstances, what occurs is an explosive quality because change is immediate. Thus, her stories are excluded. Women, 51% of world population suffer greater trauma and she is removed from restructuring a self-identity. In the end women cannot reestablish their place in the broader scheme of human affairs and history. Without women’s authored stories and metaphor, we do not have culture. We cannot access healing methods. Instead what is claimed as culture is in reality violence normalized and nationalized with a host of memorials and monuments.

For sixteen years, I have been working extensively with the Bosnian-Herzegovinian women war crimes and war survivors in the aftermath of the Balkan War (1991-1993). I have determined that maternal fright is the entrainment of transgenerational fear and trauma through the female neurobiological processes (Anderson, 2014, Christie, Pim, 2012). This pregnant woman took a green magic marker I brought with an art pad to her apartment. She took the marker and drew a spiral on her pregnant abdomen. When she was done she stated this new oral memory traditions would prevent the transgenerational transmission of trauma. She said she was transformed. She became author of her own story which was excluded and not conforming to the norms of violence.

There are many more stories I write about in my book, Blood and Honey the Secret Herstory of Women: South Slavic Women's Experiences in a World of Modern-day Territorial Warfare. In the chapter of Salutogenesis, the promotion of health, I share the story of a Croat young woman who was sold into sex trafficking in the aftermath of war. Her transformation came more than a decade after I met her in Holland. I asked her to write her story for my book. She took eons to respond and when she did what she wrote was compelling. She told me that she could not retell the story since she is no longer that pain or that victim. In fact, she said her story was not her responsibility anymore and that it was mine now.

As I've shared with you, I recently reunited with a Bosnian Muslim woman my grandmother and I sponsored in the 90s. Her life is very simple, she was not traditionally educated, and she is now 80. She was also subjected to incredible war trauma, which I did not feel entitled to ask her about, even though she wrote me about it in her letters. How do you interact in your Kolo: Women's Cross Cultural Collaboration work with women from various backgrounds and ages? Are there common experiences and acts you found to bond women across these experiences?

Isn’t this the ‘killing silences’ when you and most women feel they are not entitled to ask for grandmothers, mothers and daughters’ life experiences. Yet, you moved forward. The transformation is there in your grandmother’s letters thus providing intimacy and bonding. Note how you were able to set up a space and place for your grandmother’s war stories and trauma. The common experiences and small acts that you performed for your grandmother are the same I invite in when I interact with women. To be sure there is diversity involved since their traumas and life experiences like fingerprints are not identical.

With the South Slavic kolo, the round folk dance or to be in a circle is a multi-dimensional space creating place for women to bond and heal. What I noted was when there is healing, there is bonding and a moment of female solidarity. Having a space and place to heal is the real hospital. Interesting in the word hospital since it originates from the meaning for guest and is the root word for hospice, hotel and hospitality. The key is the relation between guest and shelterer. As with my kolo trauma work and your grandmother’s letters the relations between us and them become one while accepting the diversity. When I faced the Bosnian women in the beginning of my work in Bosnia I knew I was in a room filled with my mother in everyone present. Something in what I felt opened up the space and place for us to bond and to heal.

While daunting I was able to move through my grief with my mother and her WWII concentration camp experience became the common experiences from which women bond, learn and evolve. I knew I had privatized my pain and suffering. My mother privatized her pain and survivorship of Jasenovac concentration camp. Shock cascaded through me since the violence against women stats became a lived knowing. What I mean is I realized the universal suffering and pain most women endure but we are not allowed to voice or speak our realities in a world of violence. Isolation from each other occurs. Women’s inhumanity to women perpetuates endlessly. When I danced the kolo with the women and men, we were all shoulder to shoulder although our feet were doing their diversity in dancing the same path. The feelings of detachment and divorce from female solidarity erased in the shoulder to shoulder circle and dance. Female solidarity flourishes once we include each of our stories and understand our pain and suffering is universal. Privatizing smothers any opportunity to bond out of strength. The movement to be in a circle or the kolo is non-verbal expression of female solidarity; bonding out of strength. There is no bonding as a martyr or a victim.

I love that you refer so often to Marija Gimbutas' scholarship, which I was so fascinated with in college. Her work on SE European goddess-worshipping culture is so profound, and highlights that region as such an important location for honoring the female. How did such a patriarchal, gynocidal culture evolve from one that was so in balance with the natural world of that region?

In the beginning my visits to Bosnia showed how penetrating trauma can be. How do I then work the trauma issue outside the patriarchal norms of authoritative institutions and the ethnic hatreds focused on women as targets? However, I knew the South Slavs in prehistory had a harmonious civilization with profound art in artifacts and their communities. The symbols in what Marija Gimbutas refers to as ‘Old Europe’ lasting until 1800 BCE guided a path to circumvent the patriarchy. What was striking in their kilms, needlework and beehive ovens was the Old Europe symbols. Imagine my awe when the women who used the Old Europe symbols knew the meaning without cracking any of the Marija Gimbutas’ books.

The kolo is Mesolithic in age and something all knew and often danced. In using Gimbutas’ materials and spinning through interdisciplinary fields I was able to excavate the balance of the natural world. When we did so there was great gnashing of teeth and horror. One elderly grandmother said aloud how she taught her children to hate and to hate women. Another woman questioned on the custom to revere the mother who has sons over one that has daughters. What spiraled was activism even if it was banging pots and/or marching the streets for garbage pickup. One woman stated life is better now after the war without the supermarkets, microwave since her small house with a field of crops brought her family together. She became the wise woman who know how to plant, ferment, cook, clean and organize into relations with the natural world and her family.

If you can trace back to when women were forced to carry their father’s name you will see the erasure of women; the erasure of relations with the natural world and; erasure of honoring females. In an old Villa outside Paris is the archeological museum. I moved through the salons of time from dinosaurs to present day. When I walked through the exhibits in the prehistoric window about 80,000 BCE was the Siberian sleeping Goddess artifact. More art popped up, such as the Willendorf Goddess artifact, which is 33,000 years old. But then, the Iron Age appeared with axes, swords and violence. Yet, when I look at culture and oral memory traditions vestiges of old harmonious way of life I find that it is still repeated. This brings me to my work and research where we need to ask what culture is. Many cite violence as culture with ‘boys will be boys’. So we need to ask what violence is. Culture is the way of life centering on women and their female biology processes. Women raise the children. Women create culture. When women forget their creator role in culture or are dominated to not assume their creator role we will continue to be dominated and complicit in following patriarchal norms of violence, we will have the escalating violence.

Finally, I would like to ask you a personal question. I also mentioned that I sense I have been on a "homing" instinct with the former Yugoslavia, traveling back through the influences of my grandmother, who also knew the Balkans because she read Black Lamb, Grey Falcon by the feminist, Rebecca West. This process took me 16 years! Do we go back to the places of deep ancestral knowledge, and even trauma? And I also wonder, why is the process sometimes so long, and so unclear?

The birds do it. The salmon in the oceans do it. It’s called migration. Migration is not refugees fleeing from horrors and violence. Diaspora is not migratory process. Not all species have the magnetic direction for migration. For instance cattle and deer will align themselves in the north-south direction of earth’s geomagnetic field. Pigeons have microscopic balls of iron in their inner ears. How do the whales and dolphins know their way in the vast oceans when migrating? Perhaps, this is the homing instinct you talk of.

It took me 16 years to write Blood & Honey: The Secret Herstory of Women. A very long migratory process and I am elementally changed due to it. I migrated back and forth to Bosnia throughout the years and many other war zones across the globe. My female tacit knowledge- the ‘more than we can tell’ intelligence looks at the epigenetic inheritance which is inseparable from our lived relations to our ecosphere and our cultural environments. I am reminded of that cast of thousands of generations and billions of main actors in the building of a continual process of learning and relearning. Hence, the definition of migration.

All of this is stored in our genome. What we repeat is how our DNA replicates and repeats. This is called evolution. Our biology of perception and our human perception is embodied and literally enworlded. When we learn or relearn we are migrating toward abundance- evolving not just ourselves but all of life. One research for bioculinary practice was about how chickens become fuller in the breast and bigger since the 1500’s because we were eating them.

I do not define trauma as a mental illness. If anything, trauma and the corresponding fright/flight neurological mechanism tell me it’s healthy. My definition of trauma is intensified learning. Yes, it is not something I would jump at to enroll in this beyond doctorate level learning. In fact, most would go kicking and screaming before succumbing to trauma events. Most likely, we relive the trauma over and over again due to the fright/flight mechanisms. Here we can introduce a question to ourselves; do we need to survive or do we need to thrive? That choice which is consciousness allows us to author which venue. Thriving is about the healing process and of course becoming authors of our own stories. The diversity of our stories like the diversity of the kolo dance steps offer up restructuring and reorganization of reality. We are consciously learning to relate to all our environments. Women, especially, learn the empowerment in the role of creator of culture. Men learn to preserve, support and protect culture and all environments. Together the prescience in relation to biological and social complexity- a social intelligence emerges.

Being unclear is not about a lack of clarity since when we make a decision it is with clarity. I think the pattern of being unclear is about not being comfortable with ambiguity. Pregnancy is a good example of being in ambiguity. Childhood not adulthood is a difficult endurance to neither be here or there since decisions release that tension effortlessly. Ambiguity is the state of being not doing. In our societies the fast paced and competitive demand to not fail force us to conform to doing and productivity. More importantly, ambiguity is akin to the kolo in manifesting space and place in time. We need to create a space and place for deep ancestral knowledge.

Biography

Dr. Danica Borkovich Anderson’s interests remain consistent with exploring trauma’s impact as not a death sentence but an enrollment into intensive learning and growth. As Danica points out, the essence is summed up in the concise, collaborative social justice and self-sustainability found in healing our own local communities and ourselves. It’s about ennobling and empowering those who have suffered catastrophic violence and crisis.

Working from a base as a forensic psychotherapist (Certified Clinical Criminal Justice Specialist #16713), a balance of her work has been abroad in Africa, Bosnia, India and Sri Lanka as well as in the United States. While in the U.S., Danica’s experience and training began with the Siletz Indian Tribe in Oregon covering thirteen counties. She served this area using her experience in the clinical field of sexual abuse and abuse issues for a number of years. She has also worked in crisis care for corporations and insurance agencies since 2000.

Danica’s professional experiences delve deeply into “untamed” territory and explores possible engendered approaches that are healing, collaborative and are in sync with the environment presented.

She has conducted extraordinary in-depth work with Bosnian Muslim women war survivors and war crimes survivors. This work is enhanced by Danica’s bi-lingual capacity as a Serbo-Croatian. A decade of work is completed and is now self-sustaining by the Bosnian women. As a Serbian-American daughter of former Yugoslav immigrants whose mother survived concentration camps, Danica researches trauma and its impact identified by social studies that are significantly centered on the female, thus radiating out into both genders and the community at large.

Danica’s consultancy work as a gender psycho-social victims’ expert with the International Criminal Court (The Hague, Netherlands), addresses the importance of a trauma treatment and training curriculum that is distinctive and responsive to the impact of catastrophe and disaster events. Her work considers a wider set of relationships between trauma and environment in which trauma is situated or, alternatively, how the specific culture is perceived in the trauma exposure. Fluid and adaptive across vastly differing and diverse penal and corrections/prison systems including those of military operations, the Kolo trauma treatment and training format has a much broader spatial scale of overall distribution, becoming self-sustainable via the affected population. Anderson’s service in the United Nations World Food Program for the largest humanitarian workforce on the planet in Sudan added profound insight to her research, allowing her to survey a substantive data base that further enhanced her Kolo format.

Danica’s experience and specific skills include:

• The ability to foster not just intellectual understanding but embodiment on topics that are elusive or difficult, cutting edge and innovative or very psychologically based.

• International speaker, presenter/trainer.

• The populations worked with range from: 1) Rebels, militia and war crimes perpetrators (Afghanistan, Africa-Chad, Congo, Sudan & Uganda) and victims of crimes; 2) In Oregon with the Siletz Indian Tribe providing services for 200 tribes and bands; 3) Interfacing and training with individuals and groups in Bosnia, India and Sri Lanka who are professionals in their native organizations as advocates, social workers, Buddhist priests and directors of the agencies open to developing cross cultural collaborative skills in the field; 4) Corporate environments, universities/colleges and speaking engagements at various institutions.

• As a grassroots non-profit, her The Kolo: Women’s Cross Cultural Collaboration work enables her to understand a depth and breadth of both human rights and female human rights especially honed to helping aid in real time and in stark truth positions. Crisis and disaster response protocols and crisis intervention/prevention development and implementation are a few of her in-depth skills. Engendered training programs are few yet critically needed in corporate environments.

#killing silence#kolo#Bosnia#bioculinary#biosemiotics#trauma#genocide#Dr. Danica Anderson#marija gimbutas#migration#tasseography#transgenerational#Blood & Honey: The Secret Herstory of Women#zejna#isota#grapska#mel potter#melissa hilliard potter#slavic maternal fright#interview

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

ANTIDAYTON POKRET: BAJRAMSKI PAKETIĆI POVRATNIČKOJ DJECI U GRAPSKOJ

ANTIDAYTON POKRET: BAJRAMSKI PAKETIĆI POVRATNIČKOJ DJECI U GRAPSKOJ

ANTIDAYTON POKRET: BAJRAMSKI PAKETIĆI POVRATNIČKOJ DJECI U GRAPSKOJ

Kao već nekoliko godina unazad, AntiDayton pokret je i ovaj Bajram želio obradovati povratničku djecu na okupiranom dijelu bosanske terirorije.

Ovaj Bajram je to Grapska kod Doboja. Grapska je jedno od većih povratničkoh mjesta na prostoru tzv. rs, koja može mnogim mjestiam biti za primjer.

U ovom mjestu trenutno živi oko 50…

View On WordPress

#Almedin Muratović#Amsal Efendić#anti-dayton#anti-dejton#antidayton#antidejton#BiH#Doboj#Faruk Buljubašić#Grapska#Merima Velić#Midhat Hajdarević#Nihad Aličković#pokret#Tarik Hodović#tzv."RS"

0 notes

Link

Grapska, veliko bošnjačko selo kod Doboja, sinonim je stradanja, zločina, progona, ubijanja koje se dogodilo prije 25 godina. Logoraši iz Grapske, njih više od 400, priča su za sebe, jer su upravo oni prošli pakao, a mnogi se kući nikad nisu vratili. Aljo Hasančević (53), koji je sedam mjeseci čamio u četiri logora, odmah nakon razmjene stavio se u odbranu utf8

0 notes

Text

"Zlatni ljiljan" Mehmed Husaković uhapšen u Grapskoj kod Doboja

“ZLATNI LJILJAN” MEHMED HUSAKOVIĆ UHAPŠEN U GRAPSKOJ KOD DOBOJA

Hapšenje Bošnjaka koji žive na području bh. entiteta Republika Srpska ne prestaje šokirati tamošnje povratnike. Specijalno tužilaštvo u RS-u naredilo je hapšenje bošnjačkih povratnika na 32 lokacije u RS-u. Akciju opravdavaju pod izgovorom da se radi o sistemskoj borbi protiv terorizma.

No, komšije skoro svih uhapšenih povratnika Bošnjaka upozorili su da policija nije uhapsila teroriste, već…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Ženja's letter and the day my grandmother died

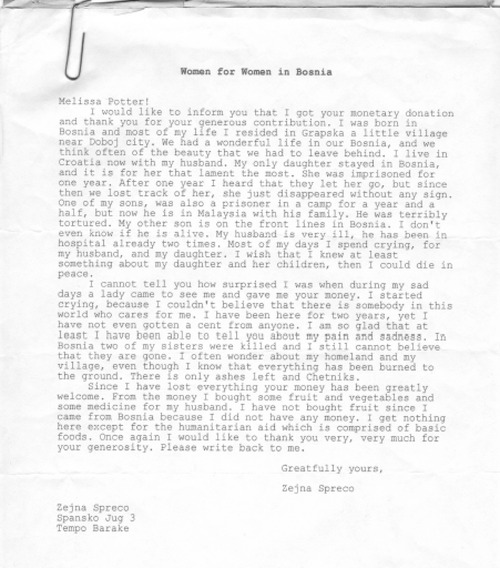

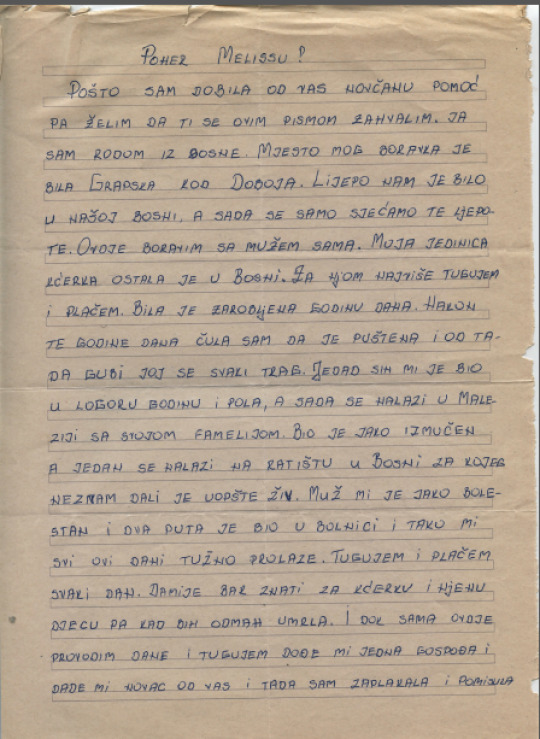

One of the letters translated by someone in the refugee camp.

On May 18, 2009, I flew down to Alexandria, Virginia to see my grandmother, whose health had been failing for more than three years. According to my mother and aunt, she had been asking for me a number of times that spring, even though I'd made a date to see her as soon as my semester was over. When I arrived, it was so clear I was her last goodbye. Though I was ashamed, I cried when I saw her. She was so gaunt and ghostlike, I knew it had been agony waiting.

After a little while, she drifted off into her morphine sleep, and I went to my guest room at the retirement home where she'd lived for more than a decade. I was exhausted. I was also despondent. 2008-9 were some of the worst years of my life, and my misery was so extreme I really thought about disappearing somewhere. I broke my ankle playing too hard in Serbia that winter. While I recuperated with a full leg cast in a fourth-floor walkup, I sat at night in total darkness hoping no one would find me.

I came down about two hours after I pulled myself together in the guest room. The nurses said she had been calling out for me. I put my hand behind her back to support her collapsed lungs under the pressure of her osteoporotic ribs and spine, and with each breath was a whimper or a yowl. I read to her, and she dozed off again thanks to the merciful drugs. And then, it all started happening. The hospice nurses came, and gave a 24 - 48 hour window based on the sweet fumes of her near death. I made phone calls to the family, and by the time I came to say goodnight, she had already died. I now understand why people believe in a soul: she literally evaporated in ten minutes, everything that she had been.

The next day, my uncle and I had to very quickly clear out her studio apartment. There wasn't much left, except a copy of Orlando I wanted to keep, and some books on the Balkans that were a bond between us. When no one else knew where Kosovo was, she did. She did because she read Rebecca West's Black Lamb, Grey Falcon. There it was, the first edition she'd carried with her to every house she'd ever lived in. I dragged all 1,200, hardcover bound pages in two volumes home. I also found a series of diary-like notebooks--each I'd hoped would tell me something I wanted to know, each with only one or two pages filled out.

I just landed in Sarajevo, and my head is splintered with questions. My host, a civil engineer who worked at the Hague reporting eyewitness testimonies from Bosnian war survivors, says that it's possible for us to go to Grapska, Ženja's town. I told him about Ženja's letters to my grandmother and me. Why does it take us so long to connect the dots? I could have done this long before 2009. I don't even know the date of the above letter. I could have asked my grandmother all the details, they being her specialty.

#Ženja Šprečo#bosnia#grapska#bosnian war#grandmother#black lamb grey falcon#rebecca west#feminism#sarajevo#mel potter#melissa potter

0 notes

Text

What Were the Chances: Bosnian Women at the Spansko Refugee Camp

What were the chances that a video exists of Senja at the Spansko camp recorded in 1993, around the time of our correspondence? What were the chances that her son could convince his boss in Croatia to turn the unused barracks into a safe haven from the mass murders and rapes taking place in her village across the border? That they all survived, went home, and can now fish in the summer, drink coffee, and smoke in peace?

What were the chances another letter fell out of a folder I moved tonight, from Fahira, the woman who accepted our donations after Senja went back to Grapska?

September 18, ‘95

“You asked me what I thought about the color brown--I like light and alive colors which refresh, I just got some brown clothes and I can tell you that I like them.

On the photograph, your hand is a bit bigger than mine.

For sure we’ll never meet, but through letters and photographs, people can be friends.”

Footage of Senja and Women Refugees at Spansko Camp 1993

1 note

·

View note

Text

Senja's letter and the day my grandmother died

A letter to me and my grandmother from Senja, relocated to Špansko refugee camp, circa 1994-5

On May 18, 2009, I flew down to Alexandria, Virginia to see my grandmother, whose health had been failing for more than three years. According to my mother and aunt, she had been asking for me a number of times that spring, even though I’d made a date to see her as soon as my semester was over. When I arrived, it was so clear I was her last goodbye. Though I was ashamed, I cried when I saw her. She was so gaunt and ghostlike, I knew it had been agony waiting.

After a little while, she drifted off into her morphine sleep, and I went to my guest room at the retirement home where she’d lived for more than a decade. I was exhausted. I was also despondent. 2008-9 were some of the worst years of my life, and my misery was so extreme I really thought about disappearing somewhere. I broke my ankle playing too hard in Serbia that winter. While I recuperated with a full leg cast in a fourth-floor walkup, I sat at night in total darkness hoping no one would find me.

I came down about two hours after I pulled myself together in the guest room. The nurses said she had been calling out for me. I put my hand behind her back to support her collapsed lungs under the pressure of her osteoporotic ribs and spine, and with each breath was a whimper or a yowl. I read to her, and she dozed off again thanks to the merciful drugs. And then, it all started happening. The hospice nurses came, and gave a 24 - 48 hour window based on the sweet fumes of her near death. I made phone calls to the family, and by the time I came to say goodnight, she had already died. I now understand why people believe in a soul: she literally evaporated in ten minutes, everything that she had been.

The next day, my uncle and I had to very quickly clear out her studio apartment. There wasn’t much left, except a copy of Orlando I wanted to keep, and some books on the Balkans that were a bond between us. When no one else knew where Kosovo was, she did. She did because she read Rebecca West’s Black Lamb, Grey Falcon. There it was, the first edition she’d carried with her to every house she’d ever lived in. I dragged all 1,200, hardcover bound pages in two volumes home. I also found a series of diary-like notebooks—each I’d hoped would tell me something I wanted to know, each with only one or two pages filled out.

I just landed in Sarajevo, and my head is splintered with questions. My host, a civil engineer who worked at the Hague reporting eyewitness testimonies from Bosnian war survivors, says that it’s possible for us to go to Grapska, Senja’s town. I told him about Senja’s letters to my grandmother and me. Why does it take us so long to connect the dots? I could have done this long before 2009. I don’t even know the date of the above letter. I could have asked my grandmother all the details, they being her specialty.

#sarajevo#grapska#women to women in bosnia#black lamb grey falcon#rebecca west#bosnia#bosnian war#isota tucker epes#mel potter#melissa potter#melissa hilliard potter#personal

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Woman from Grapska, Bosnia

I have to organize my trip to Bosnia Sunday. File papers, scan birth certificates, find a babysitter, pack in air-tight plastic bags so I don't get charged for extra baggage. Hair gel, pepto bismol. Good shoes for walking, and gifts--many of them. I wandered from this task, as I generally do, because routine bores me so.

In the file, "Personal," I keep important letters. Many are from my grandmother, who died in 2009 on a day in May when I went to visit her for the last time. Two letters in that file were from Senja, a woman my grandmother and I used to sponsor through Women to Women in Bosnia in the early 90s. We sent her $30 a month. She told us her story, amid the perfunctory notes of gratitude. They were translated for us by an English speaker who lived in the Croatian refugee camp with her.

The letters are so explicit, I immediately become overwhelmed with shame, sadness, sickness. Her first letter says her daughter stayed behind in Bosnia and was imprisoned for a year. She told me she heard that she'd been released. She wanted to die in peace knowing what happened to her and her children. Her son was moved to Malaysia after he was tortured in a camp. Her other son is on the front lines, this being right in the middle of the Siege of Sarajevo.

She spent her whole life in Grapska. Fucking internet, I had to come face-to-face with the facts in under 5 minutes. During the war, a school in Grapska was turned into rape camp. Other buildings were detention centers and work camps. In fact, this region is home to one of the four most devastating massacres and cleansing campaigns during the entire war. New testimonies reveal that children were raped to death, and the tens of thousands of women who were raped and tortured have not had their day in court. None of the tribunal cases have specifically brought justice to the perpetrators of systematic rape of women in the region.

A follow up letter from another woman in the camp indicates she moved back to Bosnia. Fahira and her son, Admir would now receive our donations. I tried to friend two men with that name. A profile picture features mass grave exhumation. I called Women to Women in Bosnia. Do they keep records? Could I find her? I'm only 20 years late. They never replied anyway.

I am looking for Senja from Grapska. I am looking for the girl who forgot all about her after she returned to Bosnia.

#bosnia#siege of sarajevo#rape#grapska#holocaust#women to women international#mel potter#melissa potter#bosnia i hercegovina#personal

2 notes

·

View notes