#harvard peabody museum

Text

Happy #InternationalDayOfTheSeal ! 🦭

Seal Decoy Helmet

Alutiiq (Pacific Eskimo), Kodiak Island, Alaska, before 1869

Carved & painted spruce wood, inlay whiskers, 17.5 x 25.5 x 19 cm (6 7/8 x 10 1/16 x 7 1/2 in.)

Harvard Peabody Museum 69-30-10/64700

“Carved from wood, hunters would have worn this hat to approach and trap seals.”

#animals in art#animal holiday#museum visit#19th century art#seal#woodwork#Indigenous art#Native American art#First Nations art#Alaskan art#Alutiiq#decoy helmet#carving#International Day of the Seal#Harvard Peabody Museum

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

i got to paint using ground cochineal insects today!

i meant to get a picture of the paints, but those four cups had lemon juice, water, baking soda, and borax added, respectively. the different pHs change the color of the cochineal powder from reddish-orange (acidic pH) to crimson (neutral pH) to beet-pink and deep purple (basic pH)

#cochineal#natural dyes#peabody museum of archeology and ethnology#harvard peabody museum#harvard museum of natural history#harvard museums of science and culture#hmsc

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky - Excavations at Tepe Yahya, Iran, 1967-1969 - ASPR/AIPU - 1970

#witches#neolithics#occult#vintage#excavations at tepe yahya#tepe yahya#excavations#american school of prehistoric research#the asia institute of pahlavi university#peabody museum#harvard university#pahlavi university#shiraz university#c.c. lamberg-karlovsky#iran#persia#archaeology#report 1#bullettin 27#woman#slim#1967-1969#1970#beauty

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Michael Rockefeller was not just any young man; he was a member of the Rockefeller family, whose fortune and influence were well-known globally. Despite his privileged background, Michael was driven by a deep curiosity about the world and a passion for adventure. After graduating from Harvard University in 1960 with a degree in history and economics, he chose to pursue his interest in anthropology and the arts, specifically the tribal art of the indigenous peoples of New Guinea.

In 1961, Michael joined the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology's Harvard-New Guinea Expedition as a sound recordist and photographer. The team was tasked with studying the cultures of the Dani people in the Baliem Valley. However, Michael’s fascination with the unique art and culture of the Asmat people, known for their elaborate wood carvings, led him to embark on a separate, more personal expedition.

On November 17, 1961, while exploring the Asmat region with Dutch anthropologist René Wassing, the pair's catamaran was swamped and overturned in the rough waters of the Betsj River estuary. With the vessel adrift and their situation growing increasingly dangerous, Rockefeller made a bold decision. Believing he could reach shore, Michael reportedly said, "I think I can make it," and swam off, leaving Wassing to stay with the boat. Those were the last words anyone ever heard from him.

When Rockefeller failed to return, a massive search effort was launched, involving the Dutch authorities, local tribes, and the Rockefeller family. The search included aerial reconnaissance, ground searches, and interrogations of local villagers, but no trace of Michael was found. After weeks of searching, the official conclusion was that Rockefeller had drowned, his body lost to the waters.

Despite the official verdict, questions and theories about Rockefeller’s fate have persisted for decades. The Asmat region was remote and largely unexplored by Westerners at the time, with a reputation for headhunting and ritual cannibalism, practices that were still alive in some tribes. This led to speculation that Michael Rockefeller may have been killed by the Asmat people—perhaps as part of a ritualistic act of revenge or initiation.

One of the most prominent theories suggests that Rockefeller did reach shore, only to be captured and killed by the Asmat. In some versions of the story, he is said to have been eaten in a ritualistic act of cannibalism. These claims were fueled by reports from missionaries and explorers who visited the area in the years following Rockefeller's disappearance, some of whom claimed to have seen evidence supporting this grim outcome.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

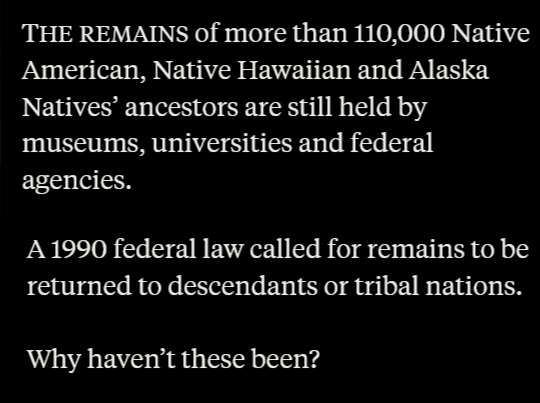

In January 2023, ProPublica has published a new and detailed report on the failure of United States museums and universities to repatriate human remains of Indigenous peoples, even when required by law.

Just ten institutions “hold about half of the Native American remains that have not been returned to tribes” as required by the 1990 law Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. As of December 2022, about “200 institutions [...] had repatriated none of the remains of more than 14,000 Native Americans in their collections.” ProPublica has investigated whether or not these institutions have complied with the 1990 law, and, in their opening paragraphs, they have “found that a small group of institutions and government bodies has played an outsized role in the law’s failure.”

By the 1870s, as the academic field of archaeology soared in popularity, some of the most prestigious institutions in the US were relying on the US military to extract Indigenous items for their collections. For example, “the Smithsonian Institution struck a deal with U.S. Army Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman to pay each of his soldiers up to $500 — or roughly $14,000 in 2022 dollars — for items such as clothing, weapons and everyday tools sent back to Washington.”

Meanwhile: “Frederic Ward Putnam, who was appointed curator of Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology in 1875, commissioned and funded excavations that would become some of the earliest collections at Harvard, the American Museum of Natural History and the Field Museum. He also helped establish the anthropology department and museum at UC Berkeley — which holds more human remains taken from Native American gravesites than any other U.S. institution that must comply with NAGPRA.”

By the beginning of the 20th century, local museums in the Midwest and Southeast (Illinois, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee) were obsessed with acquiring “moundbuilders” artifacts and initiated another wave of extraction. For example, most of the collections of the University of Kentucky’s William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology were taken during excavations funded by the federal government in the 1930s as part of the New Deal’s job-creation program, and although more than 80% of the museum’s holdings are “subject to return under federal law,” the museum “has yet to repatriate any of the roughly 4,500 human remains it has reported to the federal government.”

While the “Smithsonian Institution today holds in storage the remains of roughly 10,000 people, more than any other U.S. museum,” the Smithsonian actually “reports its repatriation progress under a different law” and therefore “does not publicly share information about what it has yet to repatriate with the same detail.”

According to ProPublica’s analysis, a major excuse given by institutions is that their collections are “culturally unidentifiable.” They report that “many institutions have interpreted” the words cultural affiliation “so narrowly that they’ve been able to dismiss” tribes’ claims. In other words, these museums claim that, because they cannot reliably trace a lineage between the original source of the remains and contemporary recognized tribes, they therefore cannot return remains. In this way, ProPublica says, that “[t]hroughout the 1990s, institutions including the Ohio History Connection and the University of Tennessee, Knoxville thrawted the repatriation process by categorizing everything” as “culturally unidentifiable.”

However, many tribes and their advocates claim this is a silly excuse. For example, the “University of Alabama Museums is among the institutions that have forced tribes into lengthy disputes over repatriation.” And tribes “had tried for more than a decade to repatriate Moundville ancestors.” By “October 2021, leaders from the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, Chickasaw Nation, Muscogee (Creek) Nation, Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, and the Seminole Tribe of Florida brought the issue to the federal NAGPRA Review Committee” and the “tribes eventually forced the largest repatriation in NAGPRA’s history” when “the university agreed to return the remains of 10,245 ancestors.”

Quoted excerpts above, and all graphics and excerpts below, from the report:

Logn Jaffe, Mary Hudetz, Ash Ngu, and Graham Lee Brewer. “America’s Biggest Museums Fail to Return Native American Human Remains.” ProPublica. 11 January 2023. (Illustrations by Weshoyot Alvitre for ProPublica. Design and development by Anna Donlan. Asia Fields and Brooke Stephenson contributed reporting.)

505 notes

·

View notes

Photo

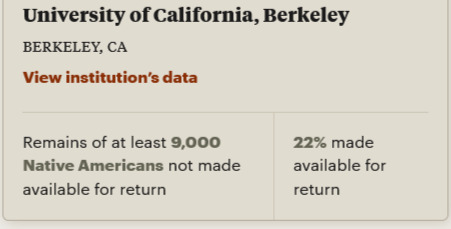

«Visible Language» – The Journal for Research on the Visual Media of Language Expression, Volume IX, Number 4, Autumn 1975, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Cover: An lncan quipu in the collection of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (full issue pdf here)

#graphic design#visual communication research#visual writing#textile#journal#magazine#cover#magazine cover#visible language#the mit press#peabody museum of archaeology and ethnology#1970s

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Press Release

Harvard Art Museums’ Fall 2023 Exhibition Explores

Entwined Histories of the Opium Trade and the Chinese

Art Market

Opium pipe, China, Qing dynasty to Republican period, inscribed with cyclical date corresponding to 1868 or 1928. Water buffalo horn, metal, and ceramic. Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop, 1943.55.6.

Cambridge, MA

This fall, the Harvard Art Museums present an exhibition that explores the entangled histories of the western sale of opium in China in the 19th century and the growing appetite for Chinese art in the United States at the beginning of the 20th century. Opium and Chinese art—acquired through both legal and illicit means—had profound effects on the global economy, cultural landscape, and education, and in the case of opium on public health and immigration, that still reverberate today. Objects of Addiction: Opium, Empire, and the Chinese Art Trade, on display September 15, 2023 through January 14, 2024 in the Special Exhibitions Gallery on Level 3 of the Harvard Art Museums, looks critically at the history of Massachusetts opium merchants and collectors of Chinese art, as well as the current opioid crisis.

A range of accompanying public programs will encourage community discussion around related topics, including the state of the opioid crisis in New England, the lingering political and economic effects of the Opium Wars, opium’s role in anti-Chinese U.S. immigration laws, and Chinese art collecting in Massachusetts. In addition, the artist collective 2nd Act will present a series of drama therapy workshops challenging ideas about addiction, and the Cambridge Public Health Department and Somerville Health and Human Services will host trainings on the use of naloxone (Narcan) to reverse opioid overdoses. In the early planning stages, Sarah Laursen, the Alan J. Dworsky Associate Curator of Chinese Art at the Harvard Art Museums, worked with Harvard students Emily Axelsen (Class of 2023), Allison Chang (Class of 2023), and Madison Stein (Class of 2024), who were instrumental in the development of the exhibition’s narrative and associated programming. Laursen also held a series of community feedback sessions to solicit reactions to the show’s content from Harvard students, faculty, and staff, as well as local experts and community members. Notably, the exhibition is opening during National Recovery Month, a national observance held each September to educate Americans about substance use disorder and the treatment options and services that can enable them to live healthy and rewarding lives.

“This exhibition is about the past and its impact on the present—but my hope it that it will also help us to think more productively about the future,” said Laursen.

“For example, the stigma around opium use initially resulted in the Qing government imposing harsh punishments for people experiencing addiction, rather than offering the empathy, treatment, and resources that people needed. Today, with overdose death rates in Massachusetts topping 2,300 individuals per year, we can learn from the past and choose to adopt harm reduction measures that will save lives.” On the collecting of Chinese art, Laursen notes, “By reexamining the formation of early 20th-century museum collections—as well as the underrecognized consequences of these initial acquisitions—we become better equipped to shape our policies for ethical collecting in the future.”

The exhibition comprises three thematic sections and presents more than 100 objects, including paintings, prints, Buddhist sculptures and murals, ceramics, jades, and bronzes, as well as historical materials including books, sale and exhibition catalogues, and magazine clippings from the collections of the Harvard Art Museums, with loans generously provided by the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Fine Arts Library, Harvard-Yenching Library, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Houghton Library, and Baker Library (all at Harvard), as well as by the Forbes House Museum, the Ipswich Museum, and Mr. and Mrs. James E. Breece III.

Beginning with an examination of the origins of the opium trade, the first section includes a large comparative timeline that lays out events in China, Europe, and the United States in order to contextualize the complex histories of the opium and Chinese art trades. Britain began illegally selling Indian opium in China in the 18th century and increased its exports to counteract the demand for Chinese tea imports in Europe and the United States. In the 19th century, prominent Massachusett merchants such as members of the Perkins, Forbes, Heard, Cushing, Sturgis, Cabot, Delano, Weld, Peabody, and other elite local families were deeply involved in the lucrative Turkish opium trade as well. Conflicts between the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) and western powers over trading rights led to two Opium Wars (1839–42 and 1856–60), whose outcomes had far-reaching political and economic consequences.

In this first gallery, examples of typical Chinese export wares including tea wares, porcelains, and paintings that were popular in Europe and North America are presented alongside opium-related objects, including an opium pipe made of water buffalo horn and an opium account book for the year 1831 that lays bare the volume of the drug imported into the port of Guangzhou by just one firm, Russell & Co., run initially by members of Forbes family. A Qing dynasty painting of the Port of Shanghai (c. 1863–64), which became a commercial center after the first Opium War, shows a bustling harbor filled with boats and ships and reveals the location of the offices of prominent opium traders such as Russell & Co. and Augustine Heard & Co. Also visible is the headquarters of auctioneer Hiram Fogg, the brother of the China trader William Hayes Fogg, for whom Harvard’s Fogg Museum is named. Along with commerce, the first gallery also presents a range of documentary materials and ephemera that demonstrate the devastating impact of opium on Chinese society. Photographs and mass media illustrations critique the use and sale of opium. A slideshow, In Their Own Words, presents quotations from a diverse range of voices of individuals who were involved in or opposed the sale of opium and collecting of Chinese art. In many cases, these quotes flesh out the perspectives of historical figures who are named in labels throughout the galleries. Audio wands available in this space play excerpts from “Opium Talk,” an essay by Zhang Changjia (Shanghai, 1878) translated by Keith McMahon in The Fall of the God of Money: Opium Smoking in Nineteenth-Century China (Rowman & Littlefield, 2002).

The translations are read by Thomas Ho, a member of the local Chinese American community, and a transcript is available in the gallery, printed with permission from McMahon.

The second section highlights the history of imperial art collecting within China and demonstrates the growing appetite for Chinese art in Europe and the United States after the Opium Wars, especially after the looting of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing by British and French Troops in 1860 and in the wake of the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901). Through the histories of merchants, collectors, dealers, museum directors, and professors, this section examines the early 20th-century formation of Chinese art collections in Massachusetts, including at the Fogg Museum. Chinese works from the collections of the Forbes House Museum and Ipswich Museum—once homes of opium traders of the Forbes and Heard families—show the taste at this time predominantly for functional or decorative objects such as export ceramics, lacquer furnishings, and other curiosities. However, the flood of newly available palace treasures and archaeological materials prompted the collecting of ancient bronzes and jades unearthed from tombs and Buddhist sculptures chiseled from cave temple walls.

Well-connected dealers in Asian art such as C. T. Loo (or Loo Ching-tsai) and Sadajirō Yamanaka 山中定次郎 acquired items from several sources—including from Chinese elites who fled the country after the fall of the Qing dynasty, imperial family members, and American collectors who lost their fortunes in the Depression—and sold those works to eager collectors around the world, such as Harvard alumnus Grenville L. Winthrop, who obtained 25 fragments from Buddhist cave temples in Tianlongshan, China.

The exhibition includes one work from this group, a sixth-century carved fragment depicting Bodhisattva Manjusri (Wenshu Pusa); to learn more about the Tianlongshan fragments now in the museums’ collections, visit hvrd.art/reframingtianlongshan. Others such as Langdon Warner, a Harvard alumnus and curator at the Fogg Museum, joined the First Fogg Expedition to China (1923–24) and personally removed works from the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, leaving permanent scars on the archaeological landscape of China. Two wall painting fragments, among the best preserved of the twelve that Warner brought back to Harvard, are displayed alongside a large-sale photograph showing the present condition of the mural from which they were removed (Bust of an attendant bodhisattva and Bust of a bodhisattva surrounded by a monk and devas).

Exhibition curator Sarah Laursen added: “I am often asked, where did this object come from? How did it come to Harvard? In many cases, we do not know their precise sources nor the circumstances of their removal because in the past there was no demand for documentation. For most U.S. collections of Asian art it is rarely possible to reconstruct the complete chain of ownership. But there are some questions we can start to answer: How can we work with source countries to better document, care for, and understand these objects? How can we curtail the black market? What could ethical collecting or sharing of cultural property look like in the future?”

A third section, entitled Opioids Then and Now, investigates parallels between China’s opium crisis and the opioid epidemic in Massachusetts today. Materials here clarify how addiction affects the brain (an animated video, produced for a free online Harvard edX course, plays on a monitor) and offer potentially life-saving information about harm reduction and overdose prevention. Visitors are invited to share their thoughts and personal experiences on response cards in this space and can either post them publicly on a bulletin board in the gallery or deposit them in a private box to be preserved in the Harvard Art Museums Archives. Visitors will also be able to browse recent books about opioids and harm reduction.

A 24-page printed booklet available in the galleries draws together the exhibition’s extensive content in three thematic essays: Who has benefited from the opium trade? Who has been harmed by opium?

What is the legacy of the opium trade in U.S. museums?

None of the works in the exhibition or in the Harvard Art Museums collections as a whole were collected or gifted by Arthur M. Sackler, nor were they purchased using funds provided by him.

Online Resource

Exhibition webpage: harvardartmuseums.org/objectsofaddiction

Public Programming

A range of public programs held in conjunction with the exhibition Objects of Addiction will encourage community discussion around the opioid crisis, the effects of the Opium Wars on U.S.–China relations, the role of opium in Chinese exclusion in the United States, and art collecting practices. Unless noted, all events are held in-person at the Harvard Art Museums, 32 Quincy Street, Cambridge, MA 02138.

Admission to visit our galleries is free, but some programs have a fee (noted below). For updates, full details, and to register, please click the links below or see our calendar:

harvardartmuseums.org/calendar. Questions? Call 617-495-9400.

Lecture — Objects of Addiction: Opium, Empire, and the Chinese Art Trade

Thursday, September 14, 2023, 6–7:30pm

Join curator Sarah Laursen for a lecture on opium and Chinese art—two influential commodities traded in China, the British Empire, and Massachusetts between the 18th and early 20th centuries.

Free admission, but seating is limited and available on a first-come, first-served basis. Following the lecture, guests are invited to visit the exhibition on Level 3. This lecture will be recorded and made available for online viewing; check the link above after the event for the link to view.

Workshops — Rethinking Addiction: A Drama Therapy Workshop with 2nd Act Artist Collective

Saturday, September 16, 2023, 2–4pm

Sunday, October 22, 2023, 2–4pm

Saturday, November 11, 2023, 2–4pm

Drama therapists Ana Bess Moyer Bell and Amy Lazier of the artist collective 2nd Act will lead workshops designed to challenge participants’ ideas about addiction through a drama therapy model. By examining, embodying, and de-stigmatizing addiction and creating metaphorical objects of care, love, and support, participants will develop a shared understanding of addiction and how it affects daily life. $15 materials fee. Registration is required and space is limited. Minimum age of 14; no previous experience required.

Lecture — Objects of Addiction: Perspectives on the Opioid Crisis in New England

Sunday, September 24, 2023, 2–3:30pm

Specialists in addiction medicine, harm reduction, and public health policy will take part in a roundtable discussion about the current state of the opioid crisis in New England. Speakers:

Danielle McPeak, Prevention and Recovery Specialist, Cambridge Public Health Department; Leo Beletsky, Professor of Law and Health Sciences; Faculty Director, The Action Lab at the Center for Health Policy and Law, Northeastern University; Mark Joseph Albanese, Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School; Medical Director, Physician Health Programs; former Medical Director for Addictions, Cambridge Health Alliance; Bertha Madras, Professor of Psychobiology, Harvard Medical School; Director, Laboratory of Addiction Neurobiology, and Psychobiologist,

Division of Basic Neuroscience, McLean Hospital; Jay Garg ’24, Policy Chair for HCOPES

(Harvard College Overdose Prevention and Education Students); and Dennis Bailer, Overdose Prevention Program Director, Project Weber/RENEW. Free admission, but seating is limited and available on a first-come, first-served basis. Before and after the discussion, guests are invited to visit the exhibition on Level 3.

Gallery Talks — Objects of Addiction: Opium, Empire, and the Chinese Art Trade

Tuesday, October 3, 2023, 12:30–1pm

Wednesday, October 18, 2023, 12:30–1pm

Thursday, November 16, 2023, 12:30–1pm

Friday, December 1, 2023, 12:30–1pm

Wednesday, December 13, 2023, 12:30–1pm

Join curator Sarah Laursen for thematic 30-minute talks focused on select artworks in the exhibition. Free admission, but space is limited to 18 people and registration is required.

Narcan Trainings with the Cambridge Public Health Department and Somerville Health and Human Services

Tuesday, October 17, 2023, 5:30–6:30pm

Sunday, November 19, 2023, 2–3pm

Friday, December 1, 2023 (time TBA)

With an abundance of care for our community, the Harvard Art Museums are hosting one-hour on-site Narcan trainings, facilitated by the Cambridge Public Health Department and Somerville Health and Human Services. Their staff will also distribute the medicine for attendees to take home.

Naloxone (also known as Narcan) is a nasal spray that can rapidly reverse an opioid overdose by blocking opioids from attaching to receptors in the brain. Free admission, but space is limited and registration is required.

Exhibition Tours — Objects of Addiction: Opium, Empire, and the Chinese Art Trade

Thursday, October 26, 2023, 12–1pm

Tuesday, November 21, 2023, 12–1pm

Saturday, December 9, 2023, 12–1pm

Join curator Sarah Laursen for hourlong tours of the exhibition. Free admission, but space is limited to 18 people and registration is required.

Online Lecture — Objects of Addiction: A Conversation about Opium and Anti-Chinese Immigration

Laws in the United States

Saturday, October 28, 2023, 10–11am

Award-winning author and Harvard history professor Erika Lee will be in conversation with two Harvard students about the role of opium in the restrictions on Chinese immigration in the United States in the 19th and 20th centuries. Speakers: Erika Lee, Bae Family Professor of History, Harvard University; Jolin Chan ’25, Harvard University; Student Board Member, Harvard Art

Museums; Madison Stein ’24, Harvard University. This talk will take place online via Zoom. The event is free and open to all, but registration is required.

Lecture — Objects of Addiction: The Legacy of the Opium Wars

Wednesday, November 8, 2023, 6–7:30pm

Harvard faculty in Chinese history, business, politics, and law will take part in a roundtable discussion on the 19th-century Opium Wars and the legacy of the opium trade in U.S.–China relations. Speakers: Mark C. Elliott, Vice Provost for International Affairs; Mark Schwartz Professor of Chinese and Inner Asian History, Harvard University; William C. Kirby, T. M. Chang Professor of China Studies, Harvard University; Spangler Family Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School; Rana Mitter, S. T. Lee Professor of U.S.–Asia Relations, Harvard Kennedy School; Meg Rithmire, F. Warren McFarlan Associate Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School; Mark Wu, Director of the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Harvard University; Henry L. Stimson Professor of Law, Harvard Law School. Free admission, but seating is limited and available on a first-come, first-served basis.

Lecture — Objects of Addiction: Collecting Chinese Art—Past, Present, and Future

Saturday, November 18, 2023, 2–3:30pm

Curators and specialists will explore early collecting of Chinese art in Massachusetts, historical interpretations of cultural heritage, and how contemporary museum collecting practices have changed and will continue to change in the future. Moderator: Soyoung Lee, Landon and Lavinia Clay Chief Curator, Harvard Art Museums. Speakers: Nancy Berliner, Wu Tung Senior Curator of Chinese Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Amy Brauer, Curator of the Collection, Division of Asian and Mediterranean Art, Harvard Art Museums; Sarah Laursen, Alan J. Dworsky Associate Curator of Chinese Art, Harvard Art Museums; Lisong Liu, Professor of History, Massachusetts College of Art and Design. Free admission, but seating is limited and available on a first-come, first- served basis. Before and after the lecture, guests are invited to visit the exhibition on Level 3.

Credits

Support for Objects of Addiction: Opium, Empire, and the Chinese Art Trade is provided by the

Alexander S., Robert L., and Bruce A. Beal Exhibition Fund; the Robert H. Ellsworth Bequest to the

Harvard Art Museums; the Harvard Art Museums’ Leopold (Harvard M.B.A. ’64) and Jane Swergold

Asian Art Exhibitions and Publications Fund and an additional gift from Leopold and Jane Swergold; the José Soriano Fund; the Anthony and Celeste Meier Exhibitions Fund; the Gurel Student Exhibition Fund; the Asian Art Discretionary Fund; the Chinese Art Discretionary Fund; and the Rabb Family Exhibitions Fund. Related programming is supported by the M. Victor Leventritt Lecture Series Endowment Fund. The accompanying booklet was made possible by generous support from Mr. and Mrs. James E. Breece III. Additional support for this project is provided by the Dunhuang Foundation.

About the Harvard Art Museums The Harvard Art Museums house one of the largest and most renowned art collections in the United States, comprising three museums (the Fogg, Busch-Reisinger, and Arthur M. Sackler Museums) and three research centers (the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, the Harvard Art Museums Archives, and the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis). The Fogg Museum includes Western art from the Middle Ages to the present; the Busch-Reisinger Museum, unique among North American museums, is dedicated to the study of all modes and periods of art from central and northern Europe, with an emphasis on German-speaking countries; and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum is focused on art from Asia, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. Together, the collections include over 255,000 objects in all media. The Harvard Art Museums are distinguished by the range and depth of their collections, their groundbreaking exhibitions, and the original research of their staff. Integral to

Harvard University and the wider community, the museums and research centers serve as resources for students, scholars, and the public. For more than a century they have been the nation’s premier training ground for museum professionals and are renowned for their seminal role in developing the discipline of art history in the United States. The Harvard Art Museums have a rich tradition of considering the history of objects as an integral part of the teaching and study of art history, focusing on conservation and preservation concerns as well as technical studies. harvardartmuseums.org

The Harvard Art Museums receive support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council.

Hours and Admission

Open Tuesday–Sunday, 10am–5pm; closed Mondays and major holidays. Admission is free to all visitors. For further information about visiting, including general policies, see harvardartmuseums.org/visit.

For more information, please contact

Jennifer Aubin

Public Relations Manager

Harvard Art Museums

617-496-5331

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photo: Gift of Prof. Alexander Emanuel Agassiz (c) President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, PM# 00-8-70/55612 (digital file# 99250028)

Fish Helmets Don’t Save Lives, Kiribati’s porcupinefish helmets were more about drama than defense. (https://hakaimagazine.com/article-short/fish-helmets-dont-save-lives/) Krista Langlois

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Love charm. Rawhide cut out in shape of an elk. Painted in yellow and blue. Thong and cloth tie. Date: 20th century. Montana, Crow Reservation. Dimensions: Overall: 25 x 23.5 x 0.5 cm. Collector: William Wildschut, William H. Claflin, Jr. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mimbres effigy jars.

From: “Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology Harvard University papers vol. 15” c.1932

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

For #WorldFrogDay:

Frog bowl with copper overlay & abalone inlay

Pacific Northwest Coast, Tlingit, 19th c.

Wood, Copper alloy, Abalone, Fiber cord

14.5 x 21 x 25.5 cm (5 11/16 x 8 1/4 x 10 1/16 in.)

Harvard Peabody Museum 08-4-10/73135

#animals in art#animal holiday#museum visit#19th century art#Harvard Peabody Museum#frog#World Frog Day#effigy bowl#bowl#copper#wood#abalone#Tlingit art#Pacific Northwest Coast art#Indigenous art#First Nations art#Native American art#metalwork#woodwork#carving

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

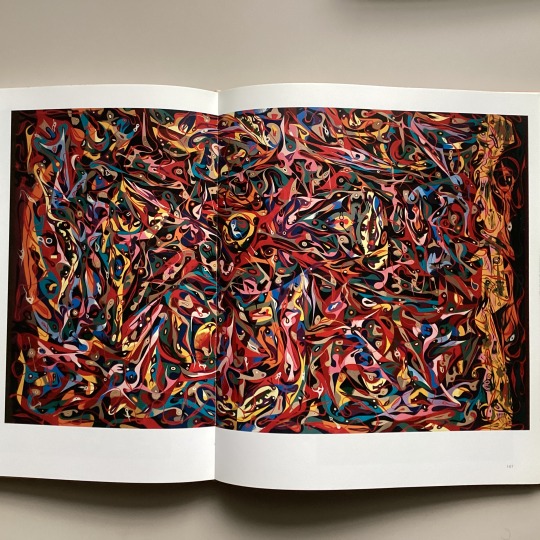

Alfonso Ossorio (b.1916, Manila, Philippines – d. 1990, New York, NY) was born in the Philippines to wealthy parents of Chinese, Filipino, and Hispanic ancestry. He moved to the United States in 1930. He studied at both Harvard University and the Rhode Island School of Design and then served in the military as a medical illustrator during the World War II.

His oil painting entitled “Beachcomber” (1953) is densely patterned with non-Western visual icons and images similar to the tribal art of Oceania which Ossorio admired at the Peabody Museum while an undergraduate at Harvard. The entire canvas is filled with endless sea of abstract forms, creating horror vacui, leaving a very little emptiness for viewers.

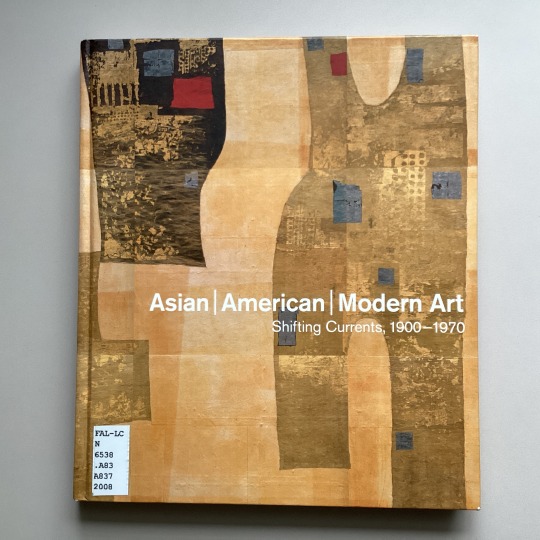

Image 1: Front cover of “Asian|American|Modern Art

Image 2: Alfonso Ossorio, “Beachcomber,” 1953, Oil on canvas, 84”x 144”

Asian American modern art : shifting currents, 1900-1970

Daniell Cornell and Mark Dean Johnson, editors ; Gordon H. Chang ... [et al.].

San Francisco, CA : Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco ; Berkeley : University of California Press, c2008.

English

HOLLIS number: 990117463940203941

#AsianAmericanandPacificIslanderHeritageMonth#AAPIHeritagemonth#AAPIheritage#AAPI#AlfonsoOssorio#AsianAmericanartist#FilipinoAmericanartist#HarvardFineArtsLibrary#Fineartslibrary#Harvard#HarvardLibrary#harvardfineartslibrary#fineartslibrary#harvard#harvardfineartslib#harvard library#painting

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brazilian Muslims demand Harvard return skull of slave who fought in uprising

The remains of a man who took part in the 1835 Males uprising have taken on foundational importance to Muslims in Brazil’s Bahia state

The Islamic community of Salvador, in Brazil’s Bahia state, has pushed Harvard University to repatriate the skull of an enslaved man who allegedly took part in a famous uprising of African Muslims in the city in 1835.

The skull is part of a Harvard collection of human remains of 19 people of African origin likely enslaved in the Americas.

The University’s Peabody and Warren museums also hold the remains of some 6,500 Native Americans, and have for decades faced pressure in the United States to return all of them to their communities or descendants.

Earlier this year, Harvard established a committee to investigate the institution’s collection of human remains and ways of returning them.

According to student newspaper The Harvard Crimson, the university agreed in September to repatriate the remains, though no further details on the process have been published.

Bahia's Muslim community, which began its campaign in September, now plans to make direct contact with Harvard through the Islamic Centre and House of Nigeria in Salvador.

Continue reading.

#brazil#politics#history#racism#archaeology#black history#muslim history#brazilian politics#harvard#mod nise da silveira#image description in alt

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

from 1/26/24 aAP News article...

"NEW YORK (AP) — New York’s American Museum of Natural History is closing two halls featuring Native American objects starting Saturday, acknowledging the exhibits are “severely outdated” and contain culturally sensitive items....

The museum said in October that it would pull all human remains from public display, with the aim of eventually repatriating as much as it could to Native American tribes and other rightful owners...

Earlier this month, Chicago’s Field Museum covered several displays containing Native American items. Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology has said it would remove all Native American funerary items from its exhibits. The Cleveland Museum of Art is another institution that has taken similar steps.

“Covering displays or taking things down isn’t the goal,” she (head of the Association of American Indian Affairs) said. “It’s about repatriation — returning objects back to tribes. So this is just one part of a much bigger process.”..."

1 note

·

View note

Text

Museus em Rede: Canais no YouTube

Já falamos aqui sobre o Museum Views, uma ferramenta dentro da Plataforma Google Arts & Culture que permite visitar o museu de dentro da sua casa.

No YouTube, os museus encontraram outra possibilidade de serem visitados. Em seus canais, os museus oferecem informações sobre sua história, seus acervos e muitas vezes opinam sobre problemáticas que afetam suas instituições.

Segue abaixo uma lista de canais de museus:

Museu Guggenhein (Nova York/EUA)

Pinacoteca (São Paulo)

Museu do Prado (Madri/ Espanha)

Museu de Arte do Rio (Rio de Janeiro)

Museu do Ipiranga/USP (São Paulo)

Museu d’Orsay (Paris/França)

Museu Nacional/UFRJ (Rio de Janeiro) -

Museu do Louvré (Paris)

Museu Whitney de Arte Americana (Nova York/)

Museu Victoria e Albert (Londres/Inglaterra)

Museu Britânico (Londres)

Museu da UFRGS (Porto Alegre)

Musée de l'Armée (Paris)

Museu de Arte do Rio Grande do Sul (Porto Alegre)

Museu de História da Medicina do Rio Grande do Sul (Porto Alegre)

Museu Nacional de Antropologia (Cidade do México)

Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam)

Museu Nacional de História Natural (Paris)

Museu Histórico Nacional (Rio de Janeiro)

Museu de Arte Moderna (Nova York)

Boston Museum of Fine Arts (Boston/EUA)

Metropolitan Museum of Art - (Nova York)

Museu de Arte de São Paulo (São Paulo)

Museu Nacional de Bellas Artes (Buenos Aires/Argentina)

Museu Peabody Essex (Salem/EUA)

Museu Nacional de Tóquio (Tóquio/Japão)

Centro Histórico Cultural Santa Casa (Porto Alegre)

Museu de Londres (Londres)

Museu de Arte Contemporânea (Los Angeles/EUA)

Museu do Vaticano

Museu da Inconfidência (Ouro Preto) -

Musée de Cluny (Paris)

Museu de História Natural (Nova York)

Museu do Futebol (São Paulo)

Museu Nacional de Belas Artes (Rio de Janeiro)

Museu Getty (Los Angeles)

Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (Havana/Cuba)

Museu Paranaense (Curitiba)

Museu Arqueológico Nacional de Napóles (Napóli/Itália)

Musée de l’Orangerie (Paris)

Museu de Arte Moderna de Buenos Aires

Musée du quai Branly (Paris)

Museu Isabella Steward Gardner (Boston)

Museu de Lisboa (Lisboa)

Museus de Arte de Harvard (Cambridge/EUA)

Museu Oscar Niemeyer (Curitiba)

Museu Reina Sofía (Madri)

Museu da Imagem e do Som (São Paulo)

Museu VanGogh (Amsterdam)

Gallerie degli Uffizi (Florença/Itália)

Museu do Brooklyn (Nova York)

Museu da Acrópole (Atenas/Grécia)

Museu do Homem (Paris)

Museu de História Natural (Londres)

Memorial JK (Brasília)

Galleria Borghese (Roma)

Museu da Memória e Direitos Humanos (Santiago/Chile)

Museu Russo (São Petesburgo/Rússia)

Museu de Belas Artes de Montreal (Montreal/Canadá)

Museu da Língua Portuguesa (São Paulo)

Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi (Belém)

Museu das Minas e Metal (Belo Horizonte)

Smithsonian's (Washington/EUA)

Museu Nacional da Escócia (Edimburgo)

Museu da Chácara do Céu (Rio de Janeiro)

Museu Egípcio de Turim (Turim/Itália)

Museu da Imigração (São Paulo)

Kunsthistorisches Museum (Viena)

Museu de História Nacional de Viena (Viena)

Museu Nacional de Belas Artes (Santiago)

MNAA Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (Lisboa)

E também:

Museu Imperial (Petrópolis)

Salem Witch Museum (Salem)

Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo (São Paulo)

Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino (Santiago)

Museu Nacional do Azulejo (Lisboa/Portugal)

Museu da Cultura Bizantina (Atenas)

Memorial Minas Gerais da Vale (Belo Horizonte)

Museu Rodin (Paris)

Museu Belvedere (Viena)

#museum#museu#musee#museo#musei#rio de janeiro#são paulo#porto alegre#paris#new york#london#amsterdam#vienna#tokyo#athens#edinburgh#montreal#rome#florence#curitiba#brasília#belo horizonte#torino#chile#buenos aires#Boston#salem#ouro preto

1 note

·

View note