#he's theseus in the king must die

Text

i think the actual disconnect between nie mingjue and jin guangyao is that nie mingjue is dying and knows he's dying and has to stick so so so closely to his morals and virtues or else it'll have been for nothing and then he'll have to come to terms with the fact that maybe he didn't actually have to die after all vs jin guangyao who wants to live, he wants to live and be safe and have all the things he was told he could never have-was told he was never good enough to have-and will do almost anything to make it so. and these are two like irreconcilable point of views right (and both Correct and Wrong at the same time) and so they can't understand each other because they aren't even having the same argument and neither of them can see that

#nie mingjue#jin guangyao#nieyao#it's good!!!#i think nmj never expected to survive the war against the wen too maybe so after he's both floundering and STILL dying#characters that didn't HAVE to die like that but did anyways because societal/family/narrative pressure etc >>>>>>>#⚰️#I've been told it's real sweet to grow old#i think there's also this disconnect between the two of them in the story as a whole re that steinberg quote i posted earlier about kleos#nostos (glory seeking vs home coming)#where jgy is the kleos or glory seeker and nmj SHOULD be the nostos (@#(and he IS to an extent) but also he ISNT because again he is dying-he knows hes dying you cant extract that from his character#and so there SHOULD be this conflict here from that but there just isnt because nmj isnt filling that role properly and i think that's part#of why jgy cant understand him#jgy is the kleos but nmj isnt a glory seeker (not outside of like the war and he's not doing that for glory etc) but he's also not nostos#he's theseus in the king must die#(sorry for referencing a bunch of shit in th tags pls pls pls ignore my rambling to myself about characters that are barely ever on page/#screen and so we can never actually fully contextualize them because we dont actually know them but oh boy oh boy can we try)#so like what does a guy who will (allegedly) give up anyone and anything domestic to gain/retain status do against a guy who otherwise#would be the opposite and unwilling/unable to sacrifice anyone for these things do when said guy does neither 🤷♀️#mine

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

A TENTH ANNIVERSARY INTERVIEW WITH SUZANNE COLLINS

On the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the publication of The Hunger Games, author Suzanne Collins and publisher David Levithan discussed the evolution of the story, the editorial process, and the first ten years of the life of the trilogy, encompassing both books and films. The following is their written conversation.

NOTE: The following interview contains a discussion of all three books in The Hunger Games Trilogy, so if you have yet to read Catching Fire and Mockingjay, you may want to read them before reading the full interview.

transcript below

DAVID LEVITHAN: Let’s start at the origin moment for The Hunger Games. You were flipping channels one night . . .

SUZANNE COLLINS: Yes, I was flipping through the channels one night between reality television programs and actual footage of the Iraq War, when the idea came to me. At the time, I was completing the fifth book in The Underland Chronicles and my brain was shifting to whatever the next project would be. I had been grappling with another story that just couldn’t get any air under its wings. I knew I wanted to continue to explore writing about just war theory for young audiences. In The Underland Chronicles, I’d examined the idea of an unjust war developing into a just war because of greed, xenophobia, and long-standing hatreds. For the next series, I wanted a completely new world and a different angle into the just war debate.

DL: Can you tell me what you mean by the “just war theory” and how that applies to the setup of the trilogy?

SC: Just war theory has evolved over thousands of years in an attempt to define what circumstances give you the moral right to wage war and what is acceptable behavior within that war and its aftermath. The why and the how. It helps differentiate between what’s considered a necessary and an unnecessary war. In The Hunger Games Trilogy, the districts rebel against their own government because of its corruption. The citizens of the districts have no basic human rights, are treated as slave labor, and are subjected to the Hunger Games annually. I believe the majority of today’s audience would define that as grounds for revolution. They have just cause but the nature of the conflict raises a lot of questions. Do the districts have the authority to wage war? What is their chance of success? How does the reemergence of District 13 alter the situation? When we enter the story, Panem is a powder keg and Katniss the spark.

DL: As with most novelists I know, once you have that origin moment — usually a connection of two elements (in this case, war and entertainment) — the number of connections quickly increases, as different elements of the story take their place. I know another connection you made early on was with mythology, particularly the myth of Theseus. How did that piece come to fit?

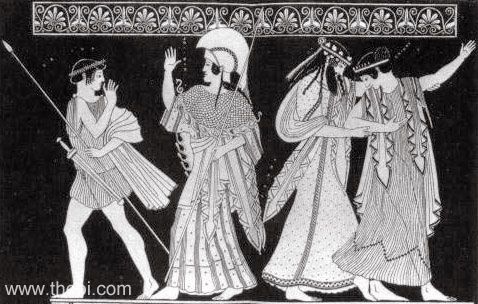

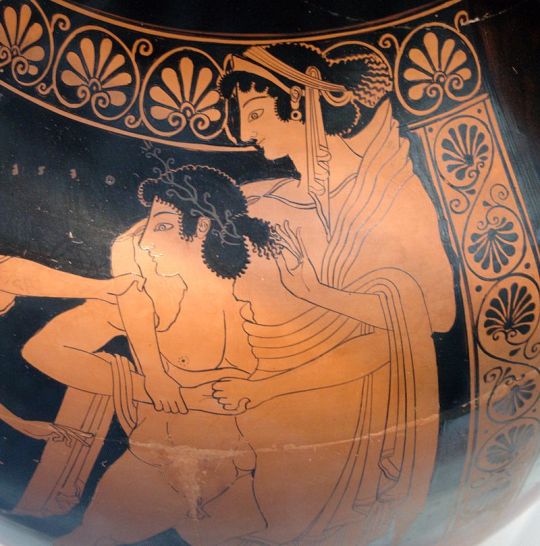

SC: I was such a huge Greek mythology geek as a kid, it’s impossible for it not to come into play in my storytelling. As a young prince of Athens, he participated in a lottery that required seven girls and seven boys to be taken to Crete and thrown into a labyrinth to be destroyed by the Minotaur. In one version of the myth, this excessively cruel punishment resulted from the Athenians opposing Crete in a war. Sometimes the labyrinth’s a maze; sometimes it’s an arena. In my teens I read Mary Renault’s The King Must Die, in which the tributes end up in the Bull Court. They’re trained to perform with a wild bull for an audience composed of the elite of Crete who bet on the entertainment. Theseus and his team dance and handspring over the bull in what’s called bull-leaping. You can see depictions of this in ancient sculpture and vase paintings. The show ended when they’d either exhausted the bull or one of the team had been killed. After I read that book, I could never go back to thinking of the labyrinth as simply a maze, except perhaps ethically. It will always be an arena to me.

DL: But in this case, you dispensed with the Minotaur, no? Instead, the arena harkens more to gladiator vs. gladiator than to gladiator vs. bull. What influenced this construction?

SC: A fascination with the gladiator movies of my childhood, particularly Spartacus. Whenever it ran, I’d be glued to the set. My dad would get outPlutarch’s Lives and read me passages from “Life of Crassus,” since Spartacus, being a slave, didn’t rate his own book. It’s about a person who’s forced to become a gladiator, breaks out of the gladiator school/arena to lead a rebellion, and becomes the face of a war. That’s the dramatic arc of both the real-life Third Servile War and the fictional Hunger Games Trilogy.

DL: Can you talk about how war stories influenced you as a young reader, and then later as a writer? How did this knowledge of war stories affect your approach to writing The Hunger Games?

SC: Now you can find many wonderful books written for young audiences that deal with war. That wasn’t the case when I was growing up. It was one of the reasons Greek mythology appealed to me: the characters battled, there was the Trojan War. My family had been heavily impacted by war the year my father, who was career Air Force, went to Vietnam, but except for my myths, I rarely encountered it in books. I liked Johnny Tremain but it ends as the Revolutionary War kicks off. The one really memorable book I had about war was Boris by Jaap ter Haar, which deals with the Siege of Leningrad in World War II.

My war stories came from my dad, a historian and a doctor of political science. The four years before he left for Vietnam, the Army borrowed him from the Air Force to teach at West Point. His final assignment would be at Air Command and Staff College. As his kids, we were never too young to learn, whether he was teaching us history or taking us on vacation to a battlefield or posing a philosophical dilemma. He approached history as a story, and fortunately he was a very engaging storyteller. As a result, in my own writing, war felt like a completely natural topic for children.

DL: Another key piece of The Hunger Games��is the voice and perspective that Katniss brings to it. I know some novelists start with a character and then find a story through that character, but with The Hunger Games (and correct me if I’m wrong) I believe you had the idea for the story first, and then Katniss stepped into it. Where did she come from? I’d love for you to talk about the origin of her name, and also the origin of her very distinctive voice.

SC: Katniss appeared almost immediately after I had the idea, standing by the bed with that bow and arrow. I’d spent a lot of time during The Underland Chronicles weighing the attributes of different weapons. I used archers very sparingly because they required light and the Underland has little natural illumination. But a bow and arrow can be handmade, shot from a distance, and weaponized when the story transitions into warfare. She was a born archer.

Her name came later, while I was researching survival training and specifically edible plants. In one of my books, I found the arrowhead plant, and the more I read about it, the more it seemed to reflect her. Its Latin name has the same roots as Sagittarius, the archer. The edible tuber roots she could gather, the arrowhead-shaped leaves were her defense, and the little white blossoms kept it in the tradition of flower names, like Rue and Primrose. I looked at the list of alternative names for it. Swamp Potato. Duck Potato. Katniss easily won the day.

As to her voice, I hadn’t intended to write in first person. I thought the book would be in the third person like The Underland Chronicles. Then I sat down to work and the first page poured out in first person, like she was saying, “Step aside, this is my story to tell.” So I let her.

DL: I am now trying to summon an alternate universe where the Mockingjay is named Swamp Potato Everdeen. Seems like a PR challenge. But let’s stay for a second on the voice — because it’s not a straightforward, generic American voice. There’s a regionalism to it, isn’t there? Was that present from the start?

SC: It was. There’s a slight District 12 regionalism to it, and some of the other tributes use phrases unique to their regions as well. The way they speak, particularly the way in which they refuse to speak like citizens of the Capitol, is important to them. No one in District 12 wants to sound like Effie Trinket unless they’re mocking her. So they hold on to their regionalisms as a quiet form of rebellion. The closest thing they have to freedom of speech is their manner of speaking.

DL: I’m curious about Katniss’s family structure. Was it always as we see it, or did you ever consider giving her parents greater roles? How much do you think the Everdeen family’s story sets the stage for Katniss’s story within the trilogy?

SC: Her parents have their own histories in District 12 but I only included what’s pertinent to Katniss’s tale. Her father’s hunting skills, musicality, and death in the mines. Her mother’s healing talent and vulnerabilities. Her deep love for Prim. Those are the elements that seemed essential to me.

DL: This completely fascinates me because I, as an author, rarely know more (consciously) about the characters than what’s in the story. But this sounds like you know much more about the Everdeen parents than found their way to the page. What are some of the more interesting things about them that a reader wouldn’t necessarily know?

SC: Your way sounds a lot more efficient. I have a world of information about the characters that didn’t make it into the book. With some stories, revealing that could be illuminating, but in the case of The Hunger Games, I think it would only be a distraction unless it was part of a new tale within the world of Panem.

DL: I have to ask — did you know from the start how Prim’s story was going to end? (I can’t imagine writing the reaping scene while knowing — but at the same time I can’t imagine writing it without knowing.)

SC: You almost have to know it and not know it at the same time to write it convincingly, because the dramatic question, Can Katniss save Prim?, is introduced in the first chapter of the first book, and not answered until almost the end of the trilogy. At first there’s the relief that, yes, she can volunteer for Prim. Then Rue, who reminds her of Prim, joins her in the arena and she can’t save her. That tragedy refreshes the question. For most of the second book, Prim’s largely out of harm’s way, although there’s always the threat that the Capitol might hurt her to hurt Katniss. The jabberjays are a reminder of that. Once she’s in District 13 and the war has shifted to the Capitol, Katniss begins to hope Prim’s not only safe but has a bright future as a doctor. But it’s an illusion. The danger that made Prim vulnerable in the beginning, the threat of the arena, still exists. In the first book, it’s a venue for the Games; in the second, the platform for the revolution; in the third, it’s the battleground of Panem, coming to a head in the Capitol. The arena transforms but it’s never eradicated; in fact it’s expanded to include everyone in the country. Can Katniss save Prim? No. Because no one is safe while the arena exists.

DL: If Katniss was the first character to make herself known within story, when did Peeta and Gale come into the equation? Did you know from the beginning how their stories would play out vis-à-vis Katniss’s?

SC: Peeta and Gale appeared quickly, less as two points on a love triangle, more as two perspectives in the just war debate. Gale, because of his experiences and temperament, tends toward violent remedies. Peeta’s natural inclination is toward diplomacy. Katniss isn’t just deciding on a partner; she’s figuring out her worldview.

DL: And did you always know which worldview would win? It’s interesting to see it presented in such a clear-cut way, because when I think of Katniss, I certainly think of force over diplomacy.

SC: And yet Katniss isn’t someone eager to engage in violence and she takes no pleasure in it. Her circumstances repeatedly push her into making choices that include the use of force. But if you look carefully at what happens in the arena, her compassionate choices determine her survival. Taking on Rue as an ally results in Thresh sparing her life. Seeking out Peeta and caring for him when she discovers how badly wounded he is ultimately leads to her winning the Games. She uses force only in self-defense or defense of a third party, and I’m including Cato’s mercy killing in that. As the trilogy progresses, it becomes increasingly difficult to avoid the use of force because the overall violence is escalating with the war. The how and the why become harder to answer.

Yes, I knew which worldview would win, but in the interest of examining just war theory you need to make the arguments as strongly as possible on both sides. While Katniss ultimately chooses Peeta, remember that in order to end the Hunger Games her last act is to assassinate an unarmed woman. Conversely, in The Underland Chronicles, Gregor’s last act is to break his sword to interrupt the cycle of violence. The point of both stories is to take the reader through the journey, have them confront the issues with the protagonist, and then hopefully inspire them to think about it and discuss it. What would they do in Katniss’s or Gregor’s situation? How would they define a just or unjust war and what behavior is acceptable within warfare? What are the human costs of life, limb, and sanity? How does developing technology impact the debate? The hope is that better discussions might lead to more nonviolent forms of conflict resolution, so we evolve out of choosing war as an option.

DL: Where does Haymitch fit into this examination of war? What worldview does he bring?

SC: Haymitch was badly damaged in his own war, the second Quarter Quell, in which he witnessed and participated in terrible things in order to survive and then saw his loved ones killed for his strategy. He self-medicates with white liquor to combat severe PTSD. His chances of recovery are compromised because he’s forced to mentor the tributes every year. He’s a version of what Katniss might become, if the Hunger Games continues. Peeta comments on how similar they are, and it’s true. They both really struggle with their worldview. He manages to defuse the escalating violence at Gale’s whipping with words, but he participates in a plot to bring down the government that will entail a civil war.

The ray of light that penetrates that very dark cloud in his brain is the moment that Katniss volunteers for Prim. He sees, as do many people in Panem, the power of her sacrifice. And when that carries into her Games, with Rue and Peeta, he slowly begins to believe that with Katniss it might be possible to end the Hunger Games.

DL: I’m also curious about how you balanced the personal and political in drawing the relationship between Katniss and Gale. They have such a history together — and I think you powerfully show the conflict that arises when you love someone, but don’t love what they believe in. (I think that resonates particularly now, when so many families and relationships and friendships have been disrupted by politics.)

SC: Yes, I think it’s painful, especially because they feel so in tune in so many ways. Katniss’s and Gale’s differences of opinion are based in just war theory. Do we revolt? How do we conduct ourselves in the war? And the ethical and personal lines climax at the same moment — the double tap bombing that takes Prim’s life. But it’s rarely simple; there are a lot of gray areas. It’s complicated by Peeta often holding a conflicting view while being the rival for her heart, so the emotional pull and the ethical pull become so intertwined it’s impossible to separate them. What do you do when someone you love, someone you know to be a good person, has a view which completely opposes your own? You keep trying to understand what led to the difference and see if it can be bridged. Maybe, maybe not. I think many conflicts grow out of fear, and in an attempt to counter that fear, people reach for solutions that may be comforting in the short term, but only increase their vulnerability in the long run and cause a lot of destruction along the way.

DL: In drawing Gale’s and Peeta’s roles in the story, how conscious were you of the gender inversion from traditional narrative tropes? As you note above, both are important far beyond any romantic subplot, but I do think there’s something fascinating about the way they both reinscribe roles that would traditionally be that of the “girlfriend.” Gale in particular gets to be “the girl back home” from so many Westerns and adventure movies — but of course is so much more than that. And Peeta, while a very strong character in his own right, often has to take a backseat to Katniss and her strategy, both in and out of the arena. Did you think about them in terms of gender and tropes, or did that just come naturally as the characters did what they were going to do on the page?

SC: It came naturally because, while Gale and Peeta are very important characters, it’s Katniss’s story.

DL: For Peeta . . . why baking?

SC: Bread crops up a lot in The Hunger Games. It’s the main food source in the districts, as it was for many people historically. When Peeta throws a starving Katniss bread in the flashback, he’s keeping her alive long enough to work out a strategy for survival. It seemed in keeping with his character to be a baker, a life giver.

But there’s a dark side to bread, too. When Plutarch Heavensbee references it, he’s talking about Panem et Circenses, Bread and Circuses, where food and entertainment lull people into relinquishing their political power. Bread can contribute to life or death in the Hunger Games.

DL: Speaking of Plutarch — in a meta way, the two of you share a job (although when you do it, only fictional people die). When you were designing the arena for the first book, what influences came into play? Did you design the arena and then have the participants react to it, or did you design the arena with specific reactions and plot points in mind?

SC: Katniss has a lot going against her in the first arena — she’s inexperienced, smaller than a lot of her competitors, and hasn’t the training of the Careers — so the arena needed to be in her favor. The landscape closely resembles the woods around District 12, with similar flora and fauna. She can feed herself and recognize the nightlock as poisonous. Thematically, the Girl on Fire needed to encounter fire at some point, so I built that in. I didn’t want it too physically flashy, because the audience needs to focus on the human dynamic, the plight of the star-crossed lovers, the alliance with Rue, the twist that two tributes can survive from the same district. Also, the Gamemakers would want to leave room for a noticeable elevation in spectacle when the Games move to the Quarter Quell arena in Catching Fire with the more intricate clock design.

DL: So where does Plutarch fall into the just war spectrum? There are many layers to his involvement in what’s going on.

SC: Plutarch is the namesake of the biographer Plutarch, and he’s one of the few characters who has a sense of the arc of history. He’s never lived in a world without the Hunger Games; it was well established by the time he was born and then he rose through the ranks to become Head Gamemaker. At some point, he’s gone from accepting that the Games are necessary to deciding they’re unnecessary, and he sets about ending them. Plutarch has a personal agenda as well. He’s seen so many of his peers killed off, like Seneca Crane, that he wonders how long it will be before the mad king decides he’s a threat not an asset. It’s no way to live. And as a gamemaker among gamemakers, he likes the challenge of the revolution. But even after they succeed he questions how long the resulting peace will last. He has a fairly low opinion of human beings, but ultimately doesn’t rule out that they might be able to change.

DL: When it comes to larger world building, how much did you know about Panem before you started writing? If I had asked you, while you were writing the opening pages, “Suzanne, what’s the primary industry of District Five?” would you have known the answer, or did those details emerge to you when they emerged within the writing of the story?

SC: Before I started writing I knew there were thirteen districts — that’s a nod to the thirteen colonies — and that they’d each be known for a specific industry. I knew 12 would be coal and most of the others were set, but I had a few blanks that naturally filled in as the story evolved. When I was little we had that board game, Game of the States, where each state was identified by its exports. And even today we associate different locations in the country with a product, with seafood or wine or tech. Of course, it’s a very simplified take on Panem. No district exists entirely by its designated trade. But for purposes of the Hunger Games, it’s another way to divide and define the districts.

DL: How do you think being from District 12 defines Katniss, Peeta, and Gale? Could they have been from any other district, or is their residency in 12 formative for the parts of their personalities that drive the story?

SC: Very formative. District 12 is the joke district, small and poor, rarely producing a victor in the Hunger Games. As a result, the Capitol largely ignores it. The enforcement of the laws is lax, the relationship with the Peacekeepers less hostile. This allows the kids to grow up far less constrained than in other districts. Katniss and Gale become talented archers by slipping off in the woods to hunt. That possibility of training with a weapon is unthinkable in, say, District 11, with its oppressive military presence. Finnick’s trident and Johanna’s ax skills develop as part of their districts’ industries, but they would never be allowed access to those weapons outside of work. Also, Katniss, Peeta, and Gale view the Capitol in a different manner by virtue of knowing their Peacekeepers better. Darius, in the Hob, is considered a friend, and he proves himself to be so more than once. This makes the Capitol more approachable on a level, more possible to befriend, and more possible to defeat. More human.

DL: Let’s talk about the Capitol for a moment — particularly its most powerful resident. I know that every name you give a character is deliberate, so why President Snow?

SC: Snow because of its coldness and purity. That’s purity of thought, although most people would consider it pure evil. His methods are monstrous, but in his mind, he’s all that’s holding Panem together. His first name, Coriolanus, is a nod to the titular character in Shakespeare’s play who was based on material from Plutarch’s Lives. He was known for his anti-populist sentiments, and Snow is definitely not a man of the people.

DL: The bond between Katniss and Snow is one of the most interesting in the entire series. Because even when they are in opposition, there seems to be an understanding between them that few if any of the other characters in the trilogy share. What role do you feel Snow plays for Katniss — and how does this fit into your examination of war?

SC: On the surface, she’s the face of the rebels, he’s the face of the Capitol. Underneath, things are a lot more complicated. Snow’s quite old under all that plastic surgery. Without saying too much, he’s been waiting for Katniss for a long time. She’s the worthy opponent who will test the strength of his citadel, of his life’s work. He’s the embodiment of evil to her, with the power of life and death. They’re obsessed with each other to the point of being blinded to the larger picture. “I was watching you, Mockingjay. And you were watching me. I’m afraid we have both been played for fools.” By Coin, that is. And then their unholy alliance at the end brings her down.

DL: One of the things that both Snow and Katniss realize is the power of media and imagery on the population. Snow may appear heartless to some, but he is very attuned to the “hearts and minds” of his citizens . . . and he is also attuned to the danger of losing them to Katniss. What role do you see propaganda playing in the war they’re waging?

SC: Propaganda decides the outcome of the war. This is why Plutarch implements the airtime assault; he understands that whoever controls the airwaves controls the power. Like Snow, he’s been waiting for Katniss, because he needs a Spartacus to lead his campaign. There have been possible candidates, like Finnick, but no one else has captured the imagination of the country like she has.

DL: In terms of the revolution, appearance matters — and two of the characters who seem to understand this the most are Cinna and Caesar Flickerman, one in a principled way, one . . . not as principled. How did you draw these two characters into your themes?

SC: That’s exactly right. Cinna uses his artistic gifts to woo the crowd with spectacle and beauty. Even after his death, his Mockingjay costume designs are used in the revolution. Caesar, whose job is to maintain the myth of the glorious games, transitions into warfare with the prisoner of war interviews with Peeta. They are both helping to keep up appearances.

DL: As a writer, you studiously avoided the trope of harkening back to the “old” geography — i.e., there isn’t a character who says, “This was once a land known as . . . Delaware.” (And thank goodness for that.) Why did you decide to avoid pinning down Panem to our contemporary geography?

SC: The geography has changed because of natural and man-made disasters, so it’s not as simple as overlaying a current map on Panem. But more importantly, it’s not relevant to the story. Telling the reader the continent gives them the layout in general, but borders are very changeful. Look at how the map of North America has evolved in the past 300 years. It makes little difference to Katniss what we called Panem in the past.

DL: Let’s talk about the D word. When you sat down to write The Hunger Games, did you think of it as a dystopian novel?

SC: I thought of it as a war story. I love dystopia, but it will always be secondary to that. Setting the trilogy in a futuristic North America makes it familiar enough to relate to but just different enough to gain some perspective. When people ask me how far in the future it’s set, I say, “It depends on how optimistic you are.”

DL: What do you think it was about the world into which the book was published that made it viewed so prominently as a dystopia?

SC: In the same way most people would define The Underland Chronicles as a fantasy series, they would define The Hunger Games as a dystopian trilogy, and they’d be right. The elements of the genres are there in both cases. But they’re first and foremost war stories to me. The thing is, whether you came for the war, dystopia, action adventure, propaganda, coming of age, or romance, I’m happy you’re reading it. Everyone brings their own experiences to the book that will color how they interpret it. I imagine the number of people who immediately identify it as a just war theory story are in the minority, but most stories are more than one thing.

DL: What was the relationship between current events and the world you were drawing? I know that with many speculative writers, they see something in the news and find it filtering into their fictional world. Were you reacting to the world around you, or was your reaction more grounded in a more timeless and/or historical consideration of war?

SC: I would say the latter. Some authors — okay, you for instance — can digest events quickly and channel them into their writing, as you did so effectively with September 11 in Love Is the Higher Law. But I don’t process and integrate things rapidly, so history works better for me.

DL: There’s nothing I like more than talking to writers about writing — so I’d love to ask about your process (even though I’ve always found the word process to be far too orderly to describe how a writer’s mind works).

As I recall, when we at Scholastic first saw the proposal for The Hunger Games Trilogy, the summary of the first book was substantial, the summary for the second book was significantly shorter, and the summary of the third book was . . . remarkably brief. So, first question: Did you stick to that early outline?

SC: I had to go back and take a look. Yes, I stuck to it very closely, but as you point out, the third book summary is remarkably brief. I basically tell you there’s a war that the Capitol eventually loses. Just coming off The Underland Chronicles, which also ends with a war, I think I’d seen how much develops along the way and wanted that freedom for this series as well.

DL: Would you outline books two and three as you were writing book one? Or would you just take notes for later? Was this the same or different from what you did with The Underland Chronicles?

SC: Structure’s one of my favorite parts of writing. I always work a story out with Post-its, sometimes using different colors for different character arcs. I create a chapter grid, as well, and keep files for later books, so that whenever I have an idea that might be useful, I can make a note of it. I wrote scripts for many years before I tried books, so a lot of my writing habits developed through that experience.

DL: Would you deliberately plant things in book one to bloom in books two or three? Are there any seeds you planted in the first book that you ended up not growing?

SC: Oh, yes, I definitely planted things. For instance, Johanna Mason is mentioned in the third chapter of the first book although she won’t appear until Catching Fire. Plutarch is that unnamed gamemaker who falls into the punch bowl when she shoots the arrow. Peeta whispers “Always” in Catching Fire when Katniss is under the influence of sleep syrup but she doesn’t hear the word until after she’s been shot in Mockingjay. Sometimes you just don’t have time to let all the seeds grow, or you cut them out because they don’t really add to the story. Like those wild dogs that roam around District 12. One could potentially have been tamed, but Buttercup stole their thunder.

DL: Since much of your early experience as a writer was as a playwright, I’m curious: What did you learn as a playwright that helped you as a novelist?

SC: I studied theater for many years — first acting, then playwriting — and I have a particular love for classical theater. I formed my ideas about structure as a playwright, how crucial it is and how, when it’s done well, it’s really inseparable from character. It’s like a living thing to me. I also wrote for children’s television for seventeen years. I learned a lot writing for preschool. If a three-year-old doesn’t like something, they just get up and walk away from the set. I saw my own kids do that. How do you hold their attention? It’s hard and the internet has made it harder. So for the eight novels, I developed a three-act structure, with each act being composed of nine chapters, using elements from both play and screenplay structures — double layering it, so to speak.

DL: Where do you write? Are you a longhand writer or a laptop writer? Do you listen to music as you write, or go for the monastic, writerly silence?

SC: I write best at home in a recliner. I used to write longhand, but now it’s all laptop. Definitely not music; it demands to be listened to. I like quiet, but not silence.

DL: You talked earlier about researching survival training and edible plants for these books. What other research did you have to do? Are you a reading researcher, a hands-on researcher, or a mix of both? (I’m imagining an elaborate archery complex in your backyard, but I am guessing that’s not necessarily accurate.)

SC: You know, I’m just not very handy. I read a lot about how to build a bow from scratch, but I doubt I could ever make one. Being good with your hands is a gift. So I do a lot of book research. Sometimes I visit museums or historic sites for inspiration. I was trained in stage combat, particularly sword fighting in drama school; I have a nice collection of swords designed for that, but that was more helpful for The Underland Chronicles. The only time I got to do archery was in gym class in high school.

DL: While I wish I could say the editorial team (Kate Egan, Jennifer Rees, and myself ) were the first-ever readers of The Hunger Games, I know this isn’t true. When you’re writing a book, who reads it first?

SC: My husband, Cap, and my literary agent, Rosemary Stimola, have consistently been the books’ first readers. They both have excellent critique skills and give insightful notes. I like to keep the editorial team as much in the dark as possible, so that when they read the first draft it’s with completely fresh eyes.

DL: Looking back now at the editorial conversations we had about The Hunger Games — which were primarily with Kate, as Jen and I rode shotgun — can you recall any significant shifts or discussions?

SC: What I mostly recall is how relieved I was to know that I had such amazing people to work with on the book before it entered the world. I had eight novels come out in eight years with Scholastic, so that was fast for me and I needed feedback I could trust. You’re all so smart, intuitive, and communicative, and with the three of you, no stone went unturned. With The Hunger Games Trilogy, I really depended on your brains and hearts to catch what worked and what didn’t.

DL: And then there was the question of the title . . .

SC: Okay, this I remember clearly. The original title of the first book was The Tribute of District Twelve. You wanted to change it to The Hunger Games, which was my name for the series. I said, “Okay, but I’m not thinking of another name for the series!” To this day, more people ask me about “the Gregor series” than “The Underland Chronicles,” and I didn’t want a repeat of that because it’s confusing. But you were right, The Hunger Games was a much better name for the book. Catching Fire was originally called The Ripple Effect and I wanted to change that one, because it was too watery for a Girl on Fire, so we came up with Catching Fire. The third book I’d come up with a title so bad I can’t even remember it except it had the word ashes in it. We both hated it. One day, you said, “What if we just call it Mockingjay?” And that seemed perfect. The three parts of the book had been subtitled “The Mockingjay,” “The Assault,” and “The Assassin.” We changed the title to Mockingjay and the first part to “The Ashes” and got that lovely alliteration in the subtitles. Thank goodness you were there; you have far better taste in titles. I believe in the acknowledgments, I call you the Title Master.

DL: With The Hunger Games, the choice of Games is natural — but the choice of Hunger is much more odd and interesting. So I’ll ask: Why Hunger Games?

SC: Because food is a lethal weapon. Withholding food, that is. Just like it is in Boris when the Nazis starve out the people of Leningrad. It’s a weapon that targets everyone in a war, not just the soldiers in combat, but the civilians too. In the prologue of Henry V, the Chorus talks about Harry as Mars, the god of war. “And at his heels, Leash’d in like hounds, should famine, sword, and fire crouch for employment.” Famine, sword, and fire are his dogs of war, and famine leads the pack. With a rising global population and environmental issues, I think food could be a significant weapon in the future.

DL: The cover was another huge effort. We easily had over a hundred different covers comped up before we landed on the iconic one. There were some covers that pictured Katniss — something I can’t imagine doing now. And there were others that tried to picture scenes. Of course, the answer was in front of us the entire time — the Mockingjay symbol, which the art director Elizabeth Parisi deployed to such amazing effect. What do you think of the impact the cover and the symbol have had? What were your thoughts when you saw this cover?

SC: Oh, it’s a brilliant cover, which I should point out I had nothing to do with. I only saw a handful of the many you developed. The one that made it to print is absolutely fantastic; I loved it at first sight. It’s classy, powerful, and utterly unique to the story. It doesn’t limit the age of the audience and I think that really contributed to adults feeling comfortable reading it. And then, of course, you followed it up with the wonderful evolution of the mockingjay throughout the series. There’s something universal about the imagery, the captive bird gaining freedom, which I think is why so many of the foreign publishers chose to use it instead of designing their own. And it translated beautifully to the screen where it still holds as the central symbolic image for the franchise.

DL: Obviously, the four movies had an enormous impact on how widely the story spread across the globe. The whole movie process started with the producers coming on board. What made you know they were the right people to shepherd this story into another form?

SC: When I decided to sell the entertainment rights to the book, I had phone interviews with over a dozen producers. Nina Jacobson’s understanding of and passion for the piece along with her commitment to protecting it won me over. She’s so articulate, I knew she’d be an excellent person to usher it into the world. The team at Lionsgate’s enthusiasm and insight made a deep impression as well. I needed partners with the courage not to shy away from the difficult elements of the piece, ones who wouldn’t try to steer the story to an easier, more traditional ending. Prim can’t live. The victory can’t be joyous. The wounds have to leave lasting scars. It’s not an easy ending but it’s an intentional one.

DL: You cowrote the screenplay for the first Hunger Games movie. I know it’s an enormously tricky thing for an author to adapt their own work. How did you approach it? What was the hardest thing about translating a novel into a screenplay? What was the most rewarding?

SC: I wrote the initial treatments and first draft and then Billy Ray came on for several drafts and then our director, Gary Ross, developed it into his shooting script and we ultimately did a couple of passes together. I did the boil down of the book, which is a lot of cutting things while trying to retain the dramatic structure. I think the hardest thing for me, because I’m not a terribly visual person, was finding the way to translate many words into few images. Billy and Gary, both far more experienced screenwriters and gifted directors as well, really excelled at that. Throughout the franchise I had terrific screenwriters, and Francis Lawrence, who directed the last three films, is an incredible visual storyteller.

The most rewarding moment on the Hunger Games movie would have been the first time I saw it put together, still in rough form, and thinking it worked.

DL: One of the strange things for me about having a novel adapted is knowing that the actors involved will become, in many people’s minds, the faces and bodies of the characters who have heretofore lived as bodiless voices in my head. Which I suppose leads to a three-part question: Do you picture your characters as you’re writing them? If so, how close did Jennifer Lawrence come to the Katniss in your head? And now when you think about Katniss, do you see Jennifer or do you still see what you imagined before?

SC: I definitely do picture the characters when I’m writing them. The actress who looks exactly like my book Katniss doesn’t exist. Jennifer looked close enough and felt very right, which is more important. She gives an amazing performance. When I think of the books, I still think of my initial image of Katniss. When I think of the movies, I think of Jen. Those images aren’t at war any more than the books are with the films. Because they’re faithful adaptations, the story becomes the primary thing. Some people will never read a book, but they might see the same story in a movie. When it works well, the two entities support and enrich each other.

DL: All of the actors did such a fantastic job with your characters (truly). Are there any in particular that have stayed with you?

SC: A writer friend of mine once said, “Your cast — they’re like a basket of diamonds.” That’s how I think of them. I feel fortunate to have had such a talented team — directors, producers, screenwriters, performers, designers, editors, marketing, publicity, everybody — to make the journey with. And I’m so grateful for the readers and viewers who invested in The Hunger Games. Stories are made to be shared.

DL: We’re talking on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of The Hunger Games. Looking back at the past ten years, what have some of the highlights been?

SC: The response from the readers, especially the young audience for which it was written. Seeing beautiful and faithful adaptations reach the screen. Occasionally hearing it make its way into public discourse on politics or social issues.

DL: The Hunger Games Trilogy has been an international bestseller. Why do you think this series struck such an important chord throughout the world?

SC: Possibly because the themes are universal. War is a magnet for difficult issues. In The Hunger Games, you have vast inequality of wealth, destruction of the planet, political struggles, war as a media event, human rights abuses, propaganda, and a whole lot of other elements that affect human beings wherever they live. I think the story might tap into the anxiety a lot of people feel about the future right now.

DL: As we celebrate the past ten years and look forward to many decades to come for this trilogy, I’d love for us to end where we should — with the millions of readers who’ve embraced these books. What words would you like to leave them with?

SC: Thank you for joining Katniss on her journey. And may the odds be ever in your favor.

#thg#the hunger games#suzanne collins#katniss everdeen#catching fire#mockingjay#tbosas#thg book club#saw they took the pdf version down smh

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theseus and women

Theseus is one of the most hated characters in Greek mythology on the internet and l wanted defend him because l love him and he's clearly, VERY clearly misunderstood. Now, by misunderstood l don't mean, "Oh, his father wasn't around so he was traumatized," l mean he is always characterized as this misogynist egoist man who everybody loves just because he's a MAN™, which isn't true at all. I'm not going to explain why l love him directly in this post but I'm just going to explain why people misinterpret his relationship with women, because other than his "misstreatment" of women, he's literally just a guy.

Theseus and Amphitrite

Like, look at him! He's just a boy! Anyways, let's start with the obvious reason he gets hate.

Ariadne

We all know the story of him leaving her behind and then Dionysus finds her yada yada. We don't know why he does this, some people say that he's just a jerk and did this dick move because he wanted to but l beg to differ. Many modern-day writers tried to explain this abandonment, though most of them just painted Theseus as a jerk like leaving her because she was annoying or like what l said, just because he's a dick. I was researching how authors reasoned him for his abandonment and guess what THERE ARE SOURCES ARE EXPLAINING HIS ACTION, 1) She was killed by Artemis, this is not a well-known one but it is an explanation of him leaving Ariadne behind, Ariadne was killed by Artemis while she was giving birth to his sons, l couldn't find a reason on why she did it but this is a reason, 2) Dionysus demanded him to leave her because he wanted her, some sources say this and even say that the reason Theseus forgot to change his sails was that he was sad about leaving Ariadne behind, now, does this mean he's an angel, no because some sources do say 3) Theseus willingly leaving her behind, however, they all give a different explanation. A reason l like comes from the book "The king must die" where Ariadne is participating in a human sacrificial ritual and Theseus doesn't like that because it reminds him of Medea or something. I don't know l just read it while researching l didn't read the book but l like it, Ariadne being all crazy and that because it would explain why she's great with Dionysus and her parents are both very cold people, one being a goddess and one being... Minos. I heard there are versions where Athena tells him to leave her but l couldn't find them so that could have been added very later. Now, what version do l see as the truth? None. I like the version my brother suggested, which is "He forgot,". HE FORGOT, HES FORGETFUL, AND HE ALSO FORGETS TO CHANGE THE SAILS. I like it so much because HES LITERALLY JUST A GUY. But, in all seriousness, you can dislike Theseus for leaving Ariadne behind since there are sources that say he left her willingly but check the other versions too.

Theseus, Athena, Dionysus, and Ariadne.

Now that that's out of the way, let's see any other reason Theseus gets hate that involves yet another woman! Which is...

Helen

There is a myth that Helen is kidnapped by Theseus... That's it. So, for context (even though everyone knows it already) Theseus and his "best bud" (wink, wink) Pirithous are both demigods, Theseus being Poseidon's son and Pirithous Zeus's. Since they both have divine blood, they conclude that they will marry one of Zeus's daughters, Theseus picks Helen and Pirithous picks Persephone (like an idiot). They abduct Helen, yada yada, try to abduct Persephone but fail miserably, yada yada. And people dislike him because... he kidnapped Helen, yeah, okay, let's break this down. Kidnapping women was a very well-known thing in ancient Greece, was it acknowledged it was bad? Yes. But was it still there? Also yes. But this isn't about lust, Theseus kidnaps Helen because she is Zeus's daughter and he thinks he deserves at least a demi-god because he is one too. Can this be considered hubris? Yes, it can, and in my opinion, it is. Theseus has done very heroic stuff and wants something in return, he thinks that a mortal wife is too little for him so he picks what he thinks is the best thing for him, a wife whose father is Zeus. He doesn't do this as an act of lust, just hubris, and maybe for reputation, since Helen is the most beautiful woman, having the most beautiful woman as a wife is a thing to be proud of. But that doesn't mean Theseus gets what he wants immediately, because Helen is young, very young. He even acknowledges that as an Athenian, which is okay to marry a 14-year-old girl, but Helen is younger. Sources change her age from 9 to 12, but the point is, she's too young. So, Theseus decides he'll wait and gives her to his mother in the meantime. When he gets rescued by Heracles, he faces consequences, which is learning his mother is now a slave to Castor and Pollux. This is what l like about him too, he's a king, a hero, yet faces consequences more than anyone. Even if he doesn't, when he does bad things to another, bad things happen to him later, Karma bites him in the ass, and in my opinion making a character face consequences is the best way to make them feel human and relatable. Theseus isn't the only one, every mortal in Greek mythology are human-like character to me because they face consequences! Heracles, Achilles, Agamemnon, Odysseus, Bellerophon, and many more make bad choices, face the consequences, and acknowledge them! Theseus kidnapping Helen is a bad thing, yes, but he didn't even touch her because she was a child and his mother got taken away in the end.

Theseus taking away Helen

So yeah, this is it. I was going to go into more detail about his relationship with women since there are women he helps and respects but this is all for now. If l made any mistakes, please let me know without sounding rude, l can take constructive criticism. Anyways, have a good day!

(@coloricioso was the one who asked me to explain my Theseus obsession, so here it is!)

#greek mythology#ancient greek mythology#greek myth#greek myths#theseus#ariadne#helen of troy#helen of sparta#I have to read so much#all the plays that have him in it#The life of Theseus#etc etc#If my attention span will let me#or my brain#anyways#I'll probably remake this when l read the plays and The life of Theseus#and make more posts about him#then I'll probably read the king must due#then Ariadne#then more#ALSO LET HIM MAKE BAD THINGS#not everyone is an angel#“Oh he did bad things!” SO WHAT#LET HIM HE CAN DO IT#Also did l mention how much l love Hippolyta and Theseus' dynamic#Amazon x Athenian king??? Sign me up#Hippolyta is going to destroy him#good for her#Im having so much fun in the tags#I hope people read them

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

ariadne, the abandoned helper (asteroid 43)

Daughter of Pasiphae and the Cretan king Minos, Ariadne was most known for her role in the myth of Theseus with whom she feel in love. Theseus was one of the many heroes who Minos meant to abandon in the Labyrinth with the Minotaur. But Theseus was a rarity in the Labyrinth as he volunteered to be sent in and kill the beast. Ariadne provided him with what he required as she was lovestruck by the hero. Theseus was capable of slaying the Minotaur with the sword she gave him and with a golden ball of thread, he found his way out of the Labyrinth. After this point in the myth, there are two popular endings: in one she hangs herself after Theseus abandons her, and in the second Theseus takes her to the island of Naxos and leaves her there to die. In the both versions, she is recused by and ends up marrying Dionysus. IN MY OPINION Ariadne in your chart represents a) where you give everything you have, b) what you lose when facing romantic rejection, c) where you easily fall in love, and/or d) where you must first face rejection in order to find love.

i encourage you to look into the aspects of ariadne along with the sign, degree, and house placement. for the more advanced astrologers, take a look at the persona chart of ariadne AND/OR add the other characters involved to see how they support or impede ariadne!

OTHER RELATED ASTEROIDS: minos (6239) and dionysus (3671)!

like what you read? leave a tip and state what post it is for! please use my "suggest a post topic" button if you want to see a specific post or mythical asteroid next!

click here for the masterlist

click here for more greek myths & legends

want a personal reading? click here to check out my reading options and prices!

#astrology#astro community#astro placements#astro chart#asteroid astrology#asteroid#natal chart#persona chart#greek mythology#astrology tumblr#astro content#astro posts#astro observations#astro notes#astroblr#ariadne#asteroid43#minos#dionysus#asteroid6239#asteroid3671

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, Before You Go Chapter Six: One More Body to Burn

Hellas is gone; so too is your life as a cartographer. You and the Darkling must quell Alina Starkov’s attempt at an uprising in order to protect the Grisha of Ravka. However, your gods are not as dead as they seem, and that which you have taken for granted will soon prove to be quite unpredictable indeed.

previous / series masterlist / next

Many centuries ago, a hero and prince named Theseus defeated a monster named the Minotaur and fought his way out of a massive labyrinth with the help of his lover, Ariadne. Although he swore to his father that he would put up white sails on ship during his return voyage to signify that he had survived the encounter, the task slipped his mind and his ship bore back black sails. Distraught, the king threw himself off a cliff, not knowing his son was alive. Sometimes, we can kill our own forefathers not through direct action, but by forgetting what we owe them.

Aleksander is waiting, you know. He is waiting for you to make a choice. You’re waiting too, actually. There is no telling where you go from here. A thousand crossroads stretch in every direction, all promising you outcomes that could be yours if you would just so much as make up your mind about where to go. The first step is always the hardest. After that, you’re too caught up in your own string of Fate to have any sort of control. Every move from there on out is a cascade of inevitabilities.

So you must make up your mind, then, and do it fast. Time is steadily running away from you on cloud-light footsteps, and before you know it, Aleksander is talking about launching another strike on Alina’s forces. You slaughtered a good number of them back at the Spinning Wheel, which makes her weak. If you manage to pin her down before she can rally more support, you’ll be able to end this once and for all.

The one thing you need before you can strike again, though, is information. Alina is remarkably good at hiding, perhaps due to the fact that your greatest informant, the elder Lantsov brother, Vasily, is an armless corpse somewhere in the Spinning Wheel. She’s up to something, anyone can tell that, but you don’t plan on walking into a trap if you can avoid it.

That means that Aleksander will need to visit her in another vision, just to be sure. You accepted this when he brought it up, even asserted that this was the best possible option. Do you believe it? Unclear. Still, it was an olive branch extended, and he took it as you knew he would.

You weren’t lying, though. You need to know where Alina is, and there’s no better way than to literally appear in her head. Aleksander departs to his study, and you can tell by the sudden magic into the room that he’s there again, back with her. Funny how they always seem to end up together.

A desperate need to escape floods your veins, and you turn and exit the building. Aleksander will find you when he has what he needs, there’s no need for you to wait for his every move or word. The air is crisp on your face, the cool air bringing some sort of sense to your mind. It is exhausting, this hiding and guessing. You want nothing more than for this war to be over, for your reign to begin. Once you can reassert the power of Grisha, when no one has to die and no one has to run, it will all be better. Of that you are certain.

Until then, though– until then, you are sure that you shall be driven mad by the utter force of it all. You fought Aleksander under a false banner until you realized the truth of him, but now that you have him back again, it feels like all you can do is try to find reasons to run again.

It reminds you of a story your mother told you of the god of the Underworld and his queen. Hades kidnapped Persephone from her home above the ground to his world of death beneath the surface. Under his watchful eye, she ate six pomegranate seeds, and so she was condemned to stay with him for half the year, and spend the remaining six months in the land above so that the world could carry on and stay alive.

You had always wondered why Persephone would allow herself to be taken from her husband for that long, but it almost makes sense to you now. Without the separation, without the urge to fight to be with him again, he becomes the villain, and you the enemy he must fight alongside the rest.

You love him, truly you do, but this constant battle to stay under the radar is gnawing at you. If it were just the two of you working in the public view to keep Grisha safe and maintain the Little Palace, you know it would be better. Alina is getting in your head, though, just as she’s getting in his.

Far enough away from your hideaway that none of your Grisha nor Aleksander can hear you, you give in to the tumultuous emotions twisting through your head and let out a bloodcurdling scream. The sound rips through the air, carrying with it all of your pain, your anger, your helplessness.

This is what love is in the end, you decide. It cuts you worse than a blade, it saves you like a miracle. Aleksander would save your life a thousand times, and in return, you would join his cause, rescue his people because you have none more of your own and his family is as good as yours. He would manipulate you just like the rest to count your power as his, and you would second-guess his every intention after so many centuries of never knowing quite what page he’s on.

He is yours, though, and you are his. At the end of the day, there is nothing more to it. You gather your self-control back around your shoulders like a cloak and begin the walk back to the hideaway. This is the fate you were destined to follow, the same path you will run until the end of time. You will leave and come back, separate yourself only to return again and again. It is a terrible cycle, and it is your cycle, and you will gladly complete it for all eternity. Perhaps you shall, if this endeavor to restore Grisha to the power they deserve is successful.

You slip back inside, and it’s like you never left. Aleksander is still locked in his vision, but on second thought, perhaps something has changed after all. The air is sharper than it was before. Maybe Alina is fighting back, or something else, because the magic surrounding him seems to have doubled. You can feel it pressing against your skin the closer you walk to him, invisible hands tearing at your clothes, your eyes, your spirit. Something is here, with him. Something that wants to reach over to his side instead of just Aleksander being the one to travel to Alina.

It makes you shiver. You close the door of his study firmly behind you; this is not a time in which you want the other Grisha overlooking whatever is going on here, and study him more closely. Aleksander’s brow is furrowed, and he seems gripped in the throes of some sort of battle. This should not be happening at all. A shudder runs over the back of your spine as you take an involuntary step away from him. This is not what either of you planned, you can tell that much. Magic splits the air, and then his eyes flash open and you were right, it is worse than before.

For when he comes back– when he comes back, he is wrong. You can tell that instantly. The air crackles with some sort of emotion that hadn’t been there before, a sharp knife of agony. The scent of blood chases this realization seconds later, but it isn’t until the light shifts and you see the body in Aleksander’s arms that you truly know what is going on.

Your breath catches in your throat. This is not Alina’s silhouette, this is not a coup already won before the battle even began. No, you recognize that silver hair, the harsh countenance even when wracked with pain. This is Baghra, and Aleksander has killed her.

It was not on purpose, you think. Already, he is reciting panicked mantras about how he didn’t want this, he didn’t mean to do this. Baghra cuts him off, says what’s done is done, and then she is gone, disappearing in a moment. Aleksander is left clutching at empty air, tears coursing down his face.

Slowly, surely, he looks up at you. “Fix this,” he says unsteadily, “Bring her back. You know the guardians of the Underworld. Stop them from letting her cross.”

You shake your head once. “She will not go to my Underworld, Aleksander. You know that. Baghra was Grisha, and she must return to the making at the heart of the world. She is beyond our reach now.”

Saying the words is awful. Baghra knew you almost as long as Aleksander, and certainly far longer than anyone else. A thousand memories flash through your head, a journey of every moment, every interaction, you’ve ever had with the woman. How she’d greeted you when Aleksander first brought you back to his camp, back before you knew he had created the Shadow Fold, back when you had just known him for an hour or two but already decided to trust him with your life because he’d trusted you with his.

She’d regarded you suspiciously at first, hesitant of outsiders who could betray her in a heartbeat, but once you proved yourself ready to lay your life on the line for the Grisha, she welcomed you as warmly as her permanent glower would allow her. You remember training sessions, years that went by, how she never said directly that she approved of your relationship with her son but how she would show it anyway. When you faked your death the first time to escape Aleksander, you regretted not being able to tell her the truth. You never knew how she responded, but you guessed enough at her grief the next time you saw her.

Yes, then, at the Little Palace under the guise of an oprichniki. Baghra is not particularly given to wild bouts of emotion, but you can still picture the satisfied smile on her face when you’d revealed yourself to her as Hecari. The centuries are impossible to bear without someone you trust, and she had trusted you. She had been willing to hide you from Aleksander for as long as it took, because at the end of the day, you were already halfway to being a daughter to her anyway.

You had wondered if you would regret letting Baghra escape with Genya, if that would spell the end of your conquest to destroy Alina. Right now, though, you would not change a thing. There had been a moment when you had directed Genya to run, when you had looked at her on the outskirts of the forest and seen Baghra’s expression shift to something almost like pride. She was proud of you, you think. Proud that you were not wholly a monster. Proud that although you fought for Grisha in a different way than her, you were still willing to protect her just as she protected you.

Aleksander doesn’t seem to grasp the fact that this is over, that all that exists of Baghra now are memories and nothing more. “This cannot happen. I need her back.”

Something about seeing him there on the floor, nursing a bloodied stump instead of a hand (wonder when that happened) makes something in you snap. “Then you shouldn’t have killed her.”

Aleksander flinches as if you have struck him. “I did not mean for this to happen,” he repeats.

Your voice is cold and high. “But it did. Can’t you see that? This is because of you. By the Gods, I cannot believe you. Do you think I do not know what it is like to lose a parent, your last surviving family? I mourn Hecate every single hour of every single day. That is not a grief you forget. I saw her murdered, that is the difference between you and I. You killed her. You did this, not Alina. You.”

Every single one of your words seems to burn like a brand. “She was fighting me,” he protests, “she severed my hand, for the Saints’ sake. Do you think I attacked her out of nowhere? She–”

You cut him off. “What, she started it? You could have ended it differently. You have all of this power, all of this pride, and you cannot stop a fight without death? Don’t be ridiculous. You know what role you had to play. She was your mother. Do not cry. You do not deserve the right to grieve. Stand up and face what you have done.”

Contrary to what you’ve told him, you are weeping by the end. Baghra was his mother, yes, but you knew her for so long that, for a few years there, she was almost yours. It is a rash and terrible claim, but you cannot help but make it.

Aleksander rises to his feet, and his face is such a storm of ruin that for one terrible moment you have absolutely no idea what he will do next. Then he takes one deep inhale and exhales, and when he looks at you again, he is calm.

“I know the identity of the third amplifier.”

It’s a wonderful bone to throw, and both of you know it. You are not so heartless that you would not recognize this peace offering for what he is. At the moment, he is a boy wracked by the most unutterable grief he has ever felt, and despite his hand in all of this, you will not repeat the argument. You’ve already said what you needed. He will deal with it accordingly.

“Where is it? Within easy travel, or on the other side of the Fold?”

He shakes his head. “It’s not a thing or an animal, it’s a person. The tracker.”

You feel as if you’ve been shot straight through the heart. “What?”

Aleksander repeats himself, but that doesn’t make the news any easier to understand. “Alina’s tracker. The Morozova bloodline runs through him. Ilya Morozova made the third and final amplifier in the blood of his other daughter.”

This news is so absurd that you would almost want to laugh were it not for the complete focus on Aleksander’s face. This is what he learned, then, what Baghra would have fought him over. This is the fate of the war.

“Mal is the firebird?”

“Yes.”

A beat. “She will have to kill him, then.”

A wave of grief and pity hits you, even more so than before. Sorrow for the woman Baghra was to Alina; one less source of support and help in this crisis. Regret that the girl who never wanted this sort of life, only to exist alongside her tracker in a quiet aftermath, will have to murder him to achieve any sort of victory over the Shadow Fold. How horrendous, that when she finally learns enough to win, the answer is her worst fear?

Aleksander is staring at you, waiting for you to say anything more. At last, you tilt your head and speak again. “We will have to end her quickly. Before she can make any mistakes.”

It would be a mercy, you think. Stopping Alina once and for all will mean that she will not have to ever stomach the thought of killing Mal again. You don’t know that she would see it that way, but surely she has at least guessed at it.

When you dare look at him again, Aleksander is transfixed, his expression running clean with relief. He was afraid that you would doubt him again, you think, but your restatement of your commitment to his cause has changed his mind.

“Yes,” he whispers, “we shall.”

He extends an arm to you and you take it, folding into his embrace. You can still feel the grief pouring from him like shadow, but underneath it all, the cold steel of resolve hardens itself around his heart. The only way for all of this to be over is to end it, and end it you shall. Alina Starkov will die. The last remaining question is how much time she has before you come to collect her corpse.

series tag list: @britishbassett, @rogueanschel, @hotleaf-juice, @mxltifxnd0m, @kaqua, @nemesis729, @imma-too-many-fandoms, @cleverzonkwombatsludge, @yourabbymoore, @nemtodd-barnes1923, @heyyitsreign, @ponyboys-sunsets, @slytherinsssss, @fruitymoonbeams-blog, @lakeli, @darlinggbrekker, @rosesberose, @w1shes43, @fairyeunji, @cryinghotmess, @rainbowgoblinfan

grishaverse tag list: @deadreaderssociety, @cameronsails, @mxltifxnd0m, @story-scribbler, @retvenkos, @thatfangirl42, @amortensie, @gods-fools-heroes, @bl606dy, @auggie2000

#aleksander morozova series#aleksander morozova oneshot#aleksander morozova x reader#aleksander morozova imagines#aleksander morozova#the darkling#the darkling imagines#the darkling x reader#the darkling oneshot#the darkling series#general kirigan#general kirigan imagines#general kirigan x reader#general kirigan oneshot#general kirigan series#grishaverse#grishaverse imagines#grishaverse x reader#grishaverse oneshot#grishaverse series#shadow and bone spoilers

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

reupload because i fixed things to make it slightly more canon accurate. at any rate! drawing characters from books i've been reading: the Cranes from the King Must Die by Mary Renault. this IS how they are described dressed in the Bull Court where the main action takes place and the Cranes actually exist. many of these designs are canon details, such as: menesthes is wiry and brown-faced, chryse is gold and ivory and grey-eyed, helike is slim and slanted-eyed, melantho is firm and bouncing and dark, amyntor is tall with a falcon-like nose and heavy dark brows, thebe is plain as a turnip etc etc etc. there are other details i could reference but i will stop for now. a divergence is theseus being the shortest of the boys, because he is actually the second tallest (behind amyntor) but i like him being shortest. and he is canonically small and feels weird about it so.

#theseus#the king must die#theseus and the minotaur#mary renault#greek mythology#aj art#love this book more art to come

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

I absolutely loved the cultural historical nerdery of The King Must Die but I hated and was bored by Theseus and was indifferent to most of the characters in an emotional sense, though I thoroughly liked a lot of them as concepts and what they meant within their world.

The only character I loved was the evil matriarchal witch queen that marries Theseus when he kills her ritual husband in ritual combat and then tells him that she aborted his son in order to spite him.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I chose to use this particular meme for "A Midsummer Night's Dream" by William Shakespeare because it is the love Hermia had for Lysander was forbidden. Everyone knew they were in love which it connects to the themes in the play. The image reflects the hardship in loving someone and not having a choice. It represents Hermia in a confusion of not knowing what to do.

First, the plan of the couple Lysander and Hermia to wed against the wishes of the courtier Demetrius. Demetrius is also in love with Hermia. And there is Helena, in love with Demetrius. All four wind up in the forest, where they are observed by the fairy king Oberon. He has his agent Puck bewitch Lysander, who rejects Hermia for Helena. Eventually, this is all set right by Puck and the comic misunderstandings which in some productions nearly turn violent are resolved.

The first set of characters are 4 young lovers. Hermia, her friend Helena, and two young men named Lysander and Demetrius. Hermia and Lysander are deeply in love, and want to marry. Her father disagrees with the match, and wants her to marry a Demetrius instead. Demetrius also loves Hermia, while Helena is in love with him. Theseus tells Hermia she must either marry Demetrius, or die. Hermia and Lysander decide to elope, and run away into the woods. Helena hopes Demetrius will love her if she tells him, and so he runs into the woods after them, and she runs after him.

As the action wraps up, Puck seperates all the lovers. He takes the spell off of Lysander so he loves Hermia again, but leaves it on Demetrius. He deposits the lovers back on the outskirts of the woods, next to Athens. Oberon takes the spell off of Titania, and they make up from their fight. All is well in the fairy world.

It’s the morning of the wedding, and the Duke’s hunting party finds the four lovers sleeping near the woods. Demetrius announces his love for Helena, and the Duke tells the two couples to get married alongside him. Bottom makes it back to his friends just in time to perform their horrible play at the wedding, the 3 couples go off for their wedding nights, and all is right with the world.

0 notes

Text

A man is at his youngest when he thinks he is a man, not yet realizing that his actions must show it.

Mary Renault, The King Must Die (Theseus, #1)

0 notes

Text

Dionysus has absolutely sent Asterius voicemails

#Hades#Asterius#hades dionysus#‘heyyyy Ari told me to tell you to tell Theseus that he can go die again’#‘You deserve better okay. listen to me. YOURE the king’#the family reunion’s must be nightmarish

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a continuation of my last analysis on this topic, where I explained why I hate the popular analogy of Tommy and Theseus.

That can be found here. I recommend reading it first, as I included a summary of what Theseus’ story actually is, (as opposed to Techno’s… abridged telling) so if you aren’t familiar with the myth, that post should help.

It’s also really detailed and I worked hard on it, so you should read it for that, too.

It’s not absolutely necessary, though. I’ll give slightly less context for this one, but the parts of the myth I’ll be talking about are pretty well known (thanks, Rick Riordan), so it shouldn’t be too tough to figure out what I’m talking about.

Without further ado, here’s why I think Wilbur is a better Theseus analogy than Tommy.

First of all, I’ll again be largely ignoring the early parts of the Theseus myth in order to focus more on the stuff with Crete and what came after, as the early bits of the myth don’t really apply well to any Dream SMP character, since they’re largely about using cleverness to defeat evil monsters and that’s… not really a story beat that happens on the SMP.

So we start in Athens.

Wilbur Soot joins the SMP and almost immediately starts a country. Dream declares war (contrary to common belief, he was the aggressor), and wins.

L’manburg is still granted independence, but they’re a vassal state and Dream still has a lot of power over them.

I’d compare this with Athens losing a war to Crete, resulting in them remaining an independent nation but being forced to send tributes to Crete every seven years.

It’s not a perfect analogy, but it lets me cast Dream as king Minos and honestly that’s too perfect a chance to pass up, given they both share the fatal flaw of hubris- being self centered pricks who think they’re equal to gods, though the consequences manifest differently.

Stuff happens, Schlatt gets elected, none of it is really relevant to the analogy so I’ll trust you to remember what happened. This isn’t a perfect comparison, after all. The Dream SMP has far too many inspirations for a single parallel to cover it all.

What is relevant: Schlatt is the Minotaur, here.

The seven year tribute comes due, Theseus volunteers.

Wilbur and Tommy are exiled from Manburg, with plans to return.

Theseus shows off when he gets to Crete, and his charisma gains him allies.

Wilbur and Tommy are slowly joined by almost all of Manburg.

Ariadne offers Theseus a way through the maze without getting lost.

Fundy comes to Pogtopia with the Diary of a Spy, revealing that Wilbur doesn’t need to worry about the morality of killing Schlatt anymore because Schlatt is likely to die soon whether they interfere or not.

Ariadne is abandoned alone on an island after giving up everything to help Theseus.

Fundy is still a traitor in Wilbur’s eyes.

Theseus takes his ball of string and enters the labyrinth, prepared to kill the Minotaur.

Wilbur and co attack Manburg, planning to kill Schlatt.

Theseus kills the Minotaur.

No one kills Schlatt, but in his final moments no one is closer to doing than Wilbur, angered by Schlatt questioning Fundy’s manhood.

Theseus forgets the white sails to signal his victory, sailing home with blackened ones instead. His father throws himself off a tower out of grief.

Wilbur’s won, but he’s lost sight of his vision for the country he founded. Though Schlatt is dead, he still can’t see L’manburg ever going back to what it was.

He goes to the button room, and Philza confronts him. If Phil knew the whole story, knew why Wilbur felt what he felt and why he did what he did, maybe things would have gone differently.

But the ship’s sails are black.

Phil kills Wilbur.

What kills Theseus, in his myth, is when he loses sight of himself. He starts with a very clear policy: whatever someone tries to do to him, he’ll do to them in kind. Someone tries to kill him? Well, more fool them, then.

But then he starts just hurting people for fun, hurting people because it makes him feel powerful, because he thinks he deserves to be groveled to.

He kidnaps Helen of Troy, tries to kidnap Persephone, drives away his family, kills his son-

Wilbur doesn’t follow quite the same path, but the resemblance is there.

He starts out nonviolent. He’ll solve his problems with words, not a sword. But that doesn’t work. Dream declares war. Eret betrays L’manburg, and L’manburg is violently slaughtered.

Wilbur loses trust, becomes paranoid.

He’s president of L’manburg, and he cries in his pillow because if he shows even an iota of weakness, Dream will just snatch L’manburg right back up. (Or so he fears)

He runs for president, and loses.