#hector boece

Text

Behold the Heirs of the Lion!

Goranus I and his nephew, Eugenius III by Dracona_Arts

Feel free to like or reblog but please do not repost! All rights reserved.

@cynicalclassicist

#art for mistland#art#fantasy art#character art#character design#writers on tumblr#artists on tumblr#tales from mistland#eugenius iii#goranus i#scotland#arthuriana#arthurian mythology#arthurian legend#arthurian fantasy#kings of scotland#royalty#george buchanan#hector boece

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

macbeth related posts/articles/essays masterlist

hi! here's a list of almost every single anaysis Thing I've come across in like two months of being insane about the scottish play. Most are about lady macbeth/the gender theme btw.

‘He has no children’: The centring of grief in The Show Must Go Online’s Macbeth - Gemma Allred: on the misogyny that frequently surrounds conversations around Lady Macbeth

this post by @amillionmillionvoices: Same topic as the previous one, but goes more in depth, explains ladymac’s motivations as mostly coming from love not self-serving ambition.

this post by @dukeofbookingham: also explains the prior point very prettily— that ladymac is (mostly) motivated by love, but also makes the case that many of it is guilt born from not fulfilling societal expectations

On the character of Lady Macbeth - Dr. Emil Pfundheler: paper that explains the same point made in the previous post, using the text to explain. Written in 1873 so explains gender as a dichotomy, but once you take that out, its points are very good.

Characteristics of women: moral, political, and historical - Anna Jameson: aka Why Lady Macbeth is not inherently evil— same topic and the other two, but focuses a bit on the fact that she is A Woman. Not my favorite, but worth reading I suppose. Also includes analyses of many female Shakespeare characters. It does include some very bad history in the beginning— Gruoch did not orchestrate Duncan’s murder. That’s something Hector Boece made up.

Lady Macbeth: “Infirm of purpose” (from The Woman’s Part: Feminist Criticism of Shakespeare) - Joan Larsen Klein: on how she both fits and doesn’t fit the idea of a reinassance wife— doesn’t fit because she isn’t aligned to god (this read more like a Christian analysis than a feminist one if I’m being honest), but fits them because she behaves like one, only subverts them because she’s like, the evil murder girl version of the Wife. The essay right after this one is also very good.

The Hysteria of Lady Macbeth: required reading if you wanna play her Btw not kidding. Analyzes her character thru the lens of freudian psychology. Screws up the text of the play a bit but provides an actual in-depth explanation of how sonnambulism works. Note that "hysteria" is not a current psychological diagnosis, but a symptom of other conditions. Still extremely interesting.

The Macbeths - G. K. Chesterton: analysis of their relationship, makes some interesting point on the differences of the nature of their ambition and desire to kill the king

Shakespeare’s tragic frontier; the world of his final tragedies - Willard Farnham: this one is long but oh boy does it go deep. Talks about the lore of the witches, explains historical context to find out how the real events were so screwed up, makes an interesting point about Macbeth’s conscience against Lady Macbeth’s, and lastly talks about the tragic world of Macbeth compared to other tragedies.

Women’s fantasy of manhood: a Shakespearean theme - D. W. Harding: exactly what it says on the tin, using ladymac and her skewed (and I’d call romanticized) idea of what a man is that she pushes on Macbeth. So yeah, talks about the gender theme. Also talks about Goneril from Lear, Cleopatra, and Volumnia from Coriolanus and how they fit the theme— although ladymac is the only one who goes downhill from it.

Unnatural women in William Shakespeare’s Macbeth - Elizabeth Klett: I’ll be honest I didn’t love this one a lot. Basically talks about how every woman in Macbeth defies gender roles. Doesn’t go too deep however. But the book has a ton of essays analyzing female characters in classic lit.

#macbeth#shakespeare#william shakespeare#lady macbeth#classic literature#english literature#classic lit#billy shakes#king lear#coriolanus#there u go. the result of 2 months on insanity#i hope this helps someone or that u have fun at least. i did#also if anyone wants to add anything about any of These feel free bc i dont know much about. most of the things discussed

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

King Alexander 1. of Scotland

Alexander is depicted within a painted oval, in profile, facing the right, wearing armour with a red scalloped collar, and a maroon cap with a jewel of drop pearls. This portrait is one of ninety-three bust-lengths commissioned to decorate the Great Gallery at Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh. It is painted by Jacob de Wet II, a Dutch artist working in Scotland from 1673. Together with eighteen full-lengths these portraits illustrate the genealogy of the royal house of Scotland from Fergus I (who ascended the throne in 330 BC) to James VII (who abdicated in 1689). De Wet’s iconographic scheme was based on well-known chronicles of Scottish history by the Renaissance humanists Hector Boece (Scotorum Historiae, 1527) and George Buchanan (Rerum Scoticarum Historia, 1582). The inscriptions on the paintings correspond with Buchanan’s list of Scottish kings: from left to right, these are the number and name of the king followed by the date of accession. The dates however are considerably muddled, by a later restorer or perhaps even the artist himself. Both real and legendary, their purpose was to proclaim the authority of the Stuarts as divinely appointed rulers of Scotland. Commissioned and paid for by the Scottish Privy Council, the series was intended to convey the power and greatness of the country’s governing body as much as that of their king. With no authentic likenesses on which to base his portraits of medieval kings, de Wet made extensive use of an earlier set by the Scottish artist George Jamesone, of which twenty-six survive in private collections. From this limited basis the resulting series appears rather repetitious. Much more important than their aesthetic merit therefore was the symbolic power of painting an extremely long royal lineage stretching more than two millennia. Buchanan, Rerum Scoticarum Historia (translation from 1751): surnamed Fierce, succeeded to his Brother … A very good and valiant Prince. He builded the Abbacies of Scone and of St Colm’s Inch. He married Sybilla, Daughter to William Duke of Normandy, &c. He died in Peace, without Succession, at Stirling’. Number 90 in the series. Inscribed ALEXANDER.COGNOMENTO.ACER. 1107.

ProvenanceCommissioned by the Scottish Privy Council in the name of Charles II.

Created between 1684 and 1686

Wikipedia

#King Alexander 1 of Scotland#portrait#art#Jacob de Wet II#painter#Scotland#historic person#12th century#history#king#royals

0 notes

Text

Wolf’s Tale - The history of the wolf in Scotland

The earliest record of this conflict between wolves and the people who lived in what is now modern Scotland comes from the 2nd century BC.

According to Hector Boece, a king called Dorvadilla reigning at that time decreed:

“The slayer of ane wolf to have ane ox to his reward.”

Boece goes on to remark that:

“Oure elders persewit this beist with gret hatreut, for the gret murdir of beistis done be the samin “.

Boece also mentions a Scottish contemporary of Julius Caesar called Edeir as a great hunter of wolves, and Boece's translator, Bellenden, tells us that in the forests of Caledonia there were:

"Gret plente of haris, hartis, hindis, dayis, rais, wolffis, wild hors, and toadis (fox),"

He later describes the "wolffis" as being "rycht noysum to the tame bestiall in all parts of Scotland."

Wars, leaving numbers of blood soaked corpses littering a battlefield, may also have been responsible for some wolves becoming accustomed to consuming human flesh. The Orkneyinga Saga tells the story of the Battle of Waterfirth, fought in the 11th century between the islanders of Skye and the invading Norse. Arnor, the Earl's Skald, describes the aftermath of the battle:

“There I saw the grey wolf gaping

O'er the wounded corse of many a man.”

The tendency of wolves to dig up buried corpses is well documented

The wolf traditionally cited as the last in all of Scotland, however, is said to have been killed on the upper reaches of the River Findhorn, at a place between Fi-Giuthas and Pall-a-chrocain, in the year 1743.

0 notes

Photo

Macbeth❤️🔥 obra de teatro de William Shakespeare🧔 La obra está libremente basada en el relato de la vida de un personaje histórico, Macbeth, quien fue rey de los escoceses entre 1040 y 1057. La fuente principal de Shakespeare para esta tragedia fueron las Crónicas de Holinshed, obra de la que extrajo también los argumentos de sus obras históricas. Raphael Holinshed se basó a su vez en Historia Gentis Scotorum (Historia de los escoceses), obra escrita en latín por el autor escocés Hector Boece e impresa por primera vez en París en 1527🎃🐈⬛🎃🐈⬛🎃🐈⬛🎃🐈⬛🎃👻👻👻👻🌕🌕🌕🌕 Envíos y entregas 📦🚚📪📤 Te invitamos a visitar nuestra tienda en línea https://linktr.ee/Loslibrosdepolifema Entregas personales todos los sábados en estación revolución (línea 2 del STCM) #libros #bookstagram #books #librosrecomendados #literatura #leer #frases #lectura #book #libro #booklover #lectores #escritos #poesia #instabook #amoleer #bookstagrammer #macbeth #williamshakespeare (en Mexico City, Mexico) https://www.instagram.com/p/CkGu1PmuYI0/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#libros#bookstagram#books#librosrecomendados#literatura#leer#frases#lectura#book#libro#booklover#lectores#escritos#poesia#instabook#amoleer#bookstagrammer#macbeth#williamshakespeare

0 notes

Text

Sea-Monk

The alleged sea monk was captured at sea between Denmark's Zealand and Sweden, in the strait Øresund, probably in 1546. Christian III of Denmark sent an illustration of it to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. The creature is recorded in Vedel's Den danske Krønicke (1575) as measuring 4 ells long. It was either caught in a herring net, or stranded, depending on the source.

16th century natural history Steenstrup's comparison of a squid with sea monks from the sixteenth century:

The capture of the sea-monk is dated to either 1546 or 1549 in 16th century literature, or to both dates, in the case of Lycosthenes (1557), who states both captures occurred near Copenhagen, Denmark. There is also a German woodcut by Stefan Hamer possibly dating to 1546, illustrating the sea-monk caught in Copenhagen in 1546.

The sea monk was listed in several illustrated natural history books published in the mid-16th century, such as Pierre Belon (1553), Guillaume Rondelet (1554), and Conrad Gesner (1558). It was described as a "fish" that looked superficially like a monk.

Belon (1553) gave a briefer notice on piscis monachus (monk-fish) in his Latin volume, a more expanded account appearing later in his French version of 1555.

Rondelet (1554) called it "the fish with the habit of a monk (piscis monachi habitu), and classed it as a merman (homo maris). But he did not think the pictorial representations he obtained could be taken at face value, and suspected they were embellished "by the painter to make the thing seem more marvelous". What prompted his suspicions of artistic license seems to be his discovery of other portrayals of the monkfish, quite different from his own, obtained by his rival and friend Gesner and others in Rome.

Rondelet stated that a drawing of it from life (or corpse) was made by an artist in the presence of a certain gentleman, who gave a copy to Charles V, and another copy to Marguerite, Queen of Navarre, the latter of which was provided to Rondelet. The picture being the gift of Marguerite, a great patron of the sciences, meant it was not something to be readily dismissed, but rather authenticated, by Marguerite, treated as an authority on par with Pliny.

Rondelet's information was imperfect in other ways: he stated the creature had been taken in "Norway at Diezum near the town called Denelopoch", but this was a garbling of Die Sund ("the Sound" of Øresund) off of Ellenbogen (Malmö, Sweden). The information was conveyed through some intermediary German source.

Belon (1555) in his French edition about the monk-fish also classed the monk-fish as a merman (French: homme marin), and garnished his commentary with mention of merfolk from ancient writings, specifically sirens, tritons, naiads, and nereids. Belon, according to Steenstrup's assessment, had faith in the existence of this sea monk without ever having seen one. Belon attributed these curiosities to "playfulness of Nature".

The fourth volume of Conrad Gesner's famous Historia Animalium described it, and although much of Gesner's piece was derivative or even copied wholesale from his predecessors, Belon and Rondelet, he appended a collolarium section containing his own findings and observations. As to the creature that measured 4 cubits, Gesner added that it had a black face like an Ethiopian, according to a German rhyme. Gesner here quoted Albertus Magnus's account of the monachus maris. He also mentioned a similar monster found in the Firth of Forth, citing Scottish historian Hector Boethius (Hector Boece). Gesner had two other sources to draw from, namely Georg Fabricius and Hector Mythobius.

The aforementioned Lycosthenes in Prodigiorum ac Ostentorum Chronicon Of Portents and Shown Times described the 1546 sea monk as having a black head, and gave an illustration of it as such.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

here’s uhh a selected part of john bellenden’s translation of hector boece’s historia gentis scotorum, i picked out the arthurian parts from the ascent of uther pendragon to the death of arthur.

uhh for one this was written in the 16th century and i am pretty sure it was written in scots so if you know that language you might have an easier time reading this, but i think it is very interesting in the way it tells the story! here modred is not a traitor but the rightful heir of the british throne which makes it notable hehe.

the full volume one and volume two are up on internet archive for free reading btw

#finny.txt#arthuriana#historia gentis scotorum#also i translated idfk a couple paragraphs i thought were of note which i will rb in a minute#also gawaine (or gawaine or walewane or walwan take your pick lol) is a YOUNGER brother here#which. can you imagine if that was like the widely accepted tradition..not an eldest daughter..horrific

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

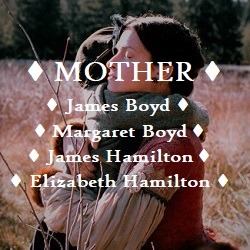

Shoddy History Edits: Mary Stewart, Countess of Arran

The oldest surviving daughter of James II of Scotland and Mary of Guelders, Mary Stewart was probably born in Stirling in July 1451*. Over the course of the next decade she would be joined by at least five siblings, four of whom lived to adulthood- the future James III (b.1452), Alexander Duke of Albany, John Earl of Mar, and Lady Margaret Stewart. Although their births secured the future of the Stewart dynasty, the early lives of these children were not exactly stable and Mary would lose both her parents by the age of thirteen. Following her father’s accidental death at Roxburgh in 1460, her mother took charge of the government of Scotland on behalf of the young James III, until her own early demise in late 1463. After this Mary’s powerful kinsman James Kennedy, Bishop of St Andrews, assumed a leading role in the kingdom’s affairs but when he died in turn in 1465, things began to get a bit out of hand. Possession of the king’s person was a valuable commodity during Scottish minorities and it wasn’t long before the favoured tactic of ‘rule by kidnap’ was employed by Robert, Lord Boyd.

In summer 1466, a group of Boyd supporters led by Robert’s brother, Alexander Boyd of Drumcoll, seized the fourteen year old James III while the king was out hunting near Linlithgow, and took control of government. A reasonable amount of nest-feathering ensued, which was not entirely unexpected. However the Boyds seem to have overstepped the mark when, on or around 26th April 1467, Lord Boyd’s eldest son Thomas was created Earl of Arran and wed the king’s older sister Mary. We don’t know what Mary herself thought about this sudden development but her brother certainly didn’t like it- James would claim in later years that he wept at the wedding, but was unable to stop it out of fear that he and his brothers would be destroyed. This bold move from the Boyds- whose chief representative was only a lord of parliament before 1467- may not have impressed the wider political community much either, especially since Mary was the eldest daughter and was probably expected to make an important match with another powerful European dynasty*. After all, several of her paternal aunts had married into princely dynasties- like the late Margaret (d.1445), who had married the dauphin of France, Isabella (d. after 1494) who married the duke of Brittany, and Eleanor (d.1480) who married the (Arch)duke of Further Austria, while three other aunts had also been involved in important, if obviously less impressive, marriage negotiations. During her mother’s negotiations with Margaret of Anjou in 1460, Mary herself had been suggested as a bride for Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales, the son of the exiled Henry VI of England. But as fate would have it, neither of James III’s sisters were destined to marry outside the kingdom- although, like her younger brother Alexander, Mary would experience her fair share of European travel.

After three years of power, the tide began to turn for the Boyds in the summer of 1469. Robert, Lord Boyd had been busy over the past year arranging the king’s marriage to Margaret, daughter of Christian I of Denmark, and now he and his son Thomas, Earl of Arran, had the honour of escorting the royal bride back to Scotland. But in the meantime James III had finally managed to seize the reins of government, and, by the by, he had also come to the conclusion that Lord Boyd and his son weren’t really in need of their heads. This must have put something of a damper on proceedings when the Boyds’ ship docked in Leith. Later sixteenth century accounts claim that Thomas Boyd was intercepted on board by his wife Mary, who warned him of her brother’s intentions. Instead of disembarking with the rest of the fleet, the couple promptly sailed away from Scotland again, with Thomas’ father Robert joining them later in exile- a sensible precaution really since James had Robert’s brother Alexander Boyd of Drumcoll executed on the castle hill of Edinburgh a few months later, and forfeited the possessions and lives of Robert and Thomas Boyd in absentia**. Whether or not Mary played an active role in the flight of her husband and father-in-law like the sixteenth century writers claim***, we do know that she joined them in exile. Sixteenth century sources claim that the Boyds in vain sought the support of the king of France, while contemporary sources show that Mary and the Boyds took refuge in Flanders, throwing themselves on the mercy of her cousin Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy.

Bruges was then a fashionable place for exiled British royals to mooch around (Edward IV of England and co. were also in residence over the winter of 1470-71). Charles the Bold was not always a reliable ally but, in the Boyds’ case, he did at least send a message to James III through his ambassador Anselm Adornes (soon to become a favourite with the king of Scots), asking for the Scottish exiles to be pardoned and allowed to return home. James thanked the duke for his courtesy to his sister but stoutly refused, recounting the Boyds’ crimes and arguing that the duke, “ought no longer to favour traitors, who to the king’s dishonour had brought his sister to exile in many foreign lands.” So the Scottish exiles remained in Bruges for some time, staying at the Hotel de Jerusalem which belonged to Anselm Adornes while its owner went on pilgrimage to the real Jerusalem. During this time Mary gave birth to two children- James and Margaret Boyd- whose godmother was Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy.

In late 1471, though, the situation looked like it was improving. Some modern historians interpret the sources as stating that a plan was developed for the Boyds and Mary cross the sea again, and for Mary to travel to Scotland to soften her brother up while the Boyds waited in England until it was safe for them to return. On the other hand, sixteenth century writers like George Buchanan and John Leslie were of the opinion that James III had lured his sister home under false pretences, “on account of the great love she bore to her husband.” In any case, a safe conduct from Calais was granted to the exiles, and to Anselm Adornes who was to accompany them, and they sailed for England in October 1471. Thomas Boyd said goodbye to the rest of the group in the southern kingdom, and went to the court of the newly restored Edward IV, where he had business with the king. The rest of the party went on to Alnwick, where they were to remain to await the outcome of Mary’s mission (Robert, Lord Boyd, now quite old, is supposed to have died there). Mary then crossed the border with Anselm Adornes and his wife. She is not known to have seen her first husband again.

Little is certainly known of Mary’s career between her return to Scotland in 1471-2 and her second marriage in 1474, but clearly any plans to restore the Boyds to favour failed. Mary herself was receiving ferms from lands in Scotland by late 1473 at least, if not earlier, indicating that, if not exactly back in favour, she was at least able to conduct some business without royal obstruction. Both Leslie and Buchanan (and other writers) claim that she was detained by her brother in Ayrshire while James III wrangled a divorce between Mary and Thomas. The grounds and exact process of any such “divorce” are unknown, other than Buchanan’s puzzling story that the king summoned Thomas Boyd to Kilmarnock to answer for his crimes within sixty days and that, when Boyd naturally failed to appear, the marriage was declared illegitimate. Mary was then married (by force and “against her inclination” according to Buchanan) to James, Lord Hamilton, a man many years her senior but greatly favoured by the king. Once again we do not know Mary’s thoughts on this match, but it had taken place by Easter 1474, when, at the king’s command, “my Lady of Hammiltoune the Kingis sister” was given six ells of purple velvet for a kirtle. We know this was not James III’s younger sister Margaret (though she did later reside in Hamilton) since in July of the same year, Lord Hamilton surrendered several lands into the king’s hands so that they could be granted back in conjunct fee to the couple, with the wife named as “Marie Senescalli ejus sponse, sorori regis”. But aside from the minor detail that Mary’s first husband was perhaps still cutting about, there were other impediments which made the new couple’s relationship less than legal. Accordingly, in April 1476, Pope Sixtus dispensed them from the impediments of consanguinity, affinity, and public honesty, and declared the child which had since been born to them legitimate. By the time of Lord Hamilton’s death three years later, at least two children had been born of the marriage- a boy named James and a girl named Elizabeth.

In the meantime, Mary’s first husband Thomas appears to have died abroad, though we have almost no information about his life following their separation, and even the sixteenth century writers do not agree on this point. Buchanan claims that he died in Antwerp not long after the “divorce”, and was buried there with great honour on the orders of Charles the Bold (he also gives his personal opinion that James Hamilton was far inferior to Mary’s first husband- hindsight is a wonderful thing). The Italian humanist Giovanni Ferreri had obviously heard very different stories about Thomas and his character from his Scottish sources, and, in his rather unreliable continuation of Hector Boece’s history, he gave Thomas a reputation as a man capable of any vice, and claimed that, after much travelling in Europe, he was murdered in Italy by a man whose wife he had seduced. But two letters in the celebrated collection of the Pastons of Norfolk have survived which refer to Thomas Boyd’s time in England , and the first of these gives a very different character sketch to that offered by Ferreri- and a rare contemporary insight into the whole affair. On 5th June 1472, John Paston the younger wrote to his older brother of the same name:

“"Also I prey yow to recomand me in my most humbyll wyse unto the good Lordshepe of the most corteys, gentylest, wysest, kyndest, most compenabyll, freest, largeest, most bowntesous knyght, my Lord the Erle of Arran, whych hathe maryed the Kyngs sustyr of Scotland. Herto he is one the lyghtest, delyverst, best spokyn, fayrest archer; devowghtest, most perfyghte, and trewest to hys lady of all the knyghtys that ever I was aqweynted with; so wold God, my Lady lyekyd me as well as I do hys person and most knyghtly condycyons, with whom I prey yow to be aqweynted, as yow semyth best; he is lodgyd at the George in Lombard Street.**** He hath a book of my syster Annys of the Sege of Thebes; when he hath doon with it, he promysyd to delyver it yow."

We are offered no such contemporary insight into Mary’s character, which must remain something of a mystery, although if even half of what the sixteenth century writers claim about her is true, she must have had her fair share of both mettle and misfortune. Though she never saw her husband again, her two children by Thomas Boyd were eventually allowed to return to Scotland and, in the early 1480s, young James Boyd was even allowed to succeed to his grandfather’s title of Lord Boyd, possibly through his mother’s political influence. Norman MacDougall has raised the possibility that the young Boyd- then only in his early teens- returned to Scotland in 1482 in the company of his uncle Alexander, Duke of Albany, who had invaded Scotland with Richard, Duke of Gloucester and an English army. Since James III wasn’t entirely free to govern as he liked during this troubled period, MacDougall suggests that Mary Stewart may have seen her chance to rebuild the Boyd patrimony in Ayrshire. The fact that the grants of land made to James Boyd (several of which which Mary received liferent of) were part of the queen’s dower and supposedly could not be alienated meant that the grants were semi-illegal, and unlikely to have been made by the king acting on his own initiative. But James Boyd’s career was destined to be brief and when his uncle Alexander fled to Dunbar in 1483, the nephew followed and the grants made to him were rescinded. The following year, the young James (who could not have been much older than fifteen) was killed by Hugh Montgomery of Eglinton, sparking a local feud in Ayrshire between the Boyds and the Montgomeries which lasted over a century.

Mary was only in her early thirties but she had already lost two husbands and was now left to bury her teenaged son. Of her four siblings, only two remained by 1488, since John, Earl of Mar, had perished in mysterious circumstances in royal custody in 1479 and Alexander, Duke of Albany met his end in 1485, when he was hit by a splinter from the lance of the Duke of Orleans (the future King Louis XII) during a tournament in France. However, Mary did not live long enough to see the death of her last brother James III at the Battle of Sauchieburn in June 1488, since she herself seems to have died earlier that year, aged around 37.

Her posthumous legacy, as with so many other women of her time, has generally been seen in terms of the later prospects of her offspring. The descendants of her two children by Lord Hamilton were destined to play an important role in the fraught politics of sixteenth century Scotland. From her son James Hamilton were descended the Earls of Arran, including the Regent Arran who governed Scotland on behalf of the infant Mary, Queen of Scots, by virtue of his position as “second person of the realm” and the little queen’s direct heir through his descent from her great-great aunt and namesake. Mary’s younger daughter Elizabeth Hamilton married Mathew Stewart, Earl of Lennox, and Elizabeth’s grandson the 4th Earl of Lennox would later challenge the claims to the throne of his cousin the Regent Arran, creating a rivalry at the very heart of Scottish politics. Margaret Boyd, the only surviving child of Mary’s first marriage, married first Lord Forbes and then returned to Ayrshire to marry the first Earl of Cassilis. Although Mary Stewart herself remains a shadowy figure to this day, her story- both factual and speculative- has attracted interest and sympathy throughout the centuries and still offers opportunities for further discovery.

Additional notes and references below the cut.

Edit: the ‘read more’ section isn’t showing up on a lot of versions of this, so I will just have to put all the notes and sources below, even though it’s messy:

* In the twentieth century there was quite a bit of debate over the correct dates of birth for James III and Mary. Despite what is on wikipedia, this has largely been resolved and the general consensus is that Mary was the elder sibling.

** Some historians have debated whether Mary’s marriage prospects were quite so important to the political community in 1467 as has been traditionally assumed, but the Stewart dynasty’s contemporary European marriage alliances are nonetheless important to bear in mind.

*** Lord Boyd’s two younger sons were spared the king’s wrath however, and the youngest of them, Archibald Boyd of Naristoun, was the father of Marion Boyd, a mistress of James IV.

**** In all fairness though, we have so few contemporary chronicles/histories for the reign of James III that we have to take the sixteenth century writers at their word sometimes, especially where they agree with each other. Nonetheless we should always be cautious.

**** It’s worth noting that the site of the George in Lombard street in London is still occupied today, since there has been an inn on the spot since the twelfth century and its current incarnation is an eighteenth century building housing the George and Vulture restaurant. It seems that several of the buildings of Anselm Adornes’ estate where the Boyds were housed in Bruges also still exist, though I will have to do more research on this.

References (I have included links to online versions where available):

- “The Date of the Birth of James III”- there are two articles by this name in the Edinburgh Historical Review for the years 1950 and 1951 respectively, and both of them were consulted. The author of the first was Annie I. Dunlop while corrections and debate between Dunlop and Dr William Angus comprise the second.

- “James III”, by Norman MacDougall

- “Power and Propaganda: Scotland, 1306-1488″, by Katie Stevenson

- “The Boyds in Bruges”, W.H. Finlayson

- “A Letter of James III to the Duke of Burgundy”, C.A.J. Armstrong

- John Lesley’s “The Historie of Scotland”

- This translation of George Buchanan’s “History of Scotland”

- “Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland”, vol. 1

- “The Exchequer Rolls of Scotland”, vol. 5

- “Register of the Great Seal of Scotland”, vol. 2

- “Vetera monumenta Hibernorum et Scotorum historiam illustrantia...”, Augustin Thenier

- “The Paston Letters”, vol. 3, edited by James Gairdner

- Giovanni Ferreri’s continuation to Boece I had to use the translation from this website since I couldn’t get access to the 1574 printing any other way, though my reading is backed up by secondary sources.

#This was not my best edit I may redo it later#My sources are pretty decent though so proud of that#women in history#British history#History edits#But had to get the word out about Mary- apologies for the length when I know there's not much definite info on her but context is important#Also James III and his siblings were a bonfire of insanity- Mary actually got off comparatively lightly#I don't know what was in the air in the 1470s- the York brothers were just as bad and on the continent there's a fair few similar cases#the Stewarts#shoddy history gifsets#Mary Stewart Countess of Arran

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hector Boece Court, Aberdeen Student Accommodation | Unilodgers.com

Hector Boece Court university accommodation from £113pw. Self-catering, shared apartments available. Book Now. Pay Later. Free Cancellation.

Click here to view the property:

0 notes

Text

A Schemer and a Brute...

Gunvasius, the second man of Orkney by Dracona_Arts

Donald of Athol, a simple man who hears and obeys by Dracona_Arts

Feel free to like or reblog but please do not repost! All rights reserved.

@cynicalclassicist

#art for mistland#art#fantasy art#character art#character design#writers on tumblr#artists on tumblr#tales from mistland#gunvasius#donald of athol#scotland#orkney#arthuriana#arthurian mythology#arthurian legend#arthurian fantasy#nobility#royalty#george buchanan#hector boece

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On August 15th 1057 King of Alba, MacBeth, was killed at Lumphanan.

17 years and one day after he killed Duncan II to seize the crown Mac Bethad mac Findláich himself fell foul of the violent times. So what of his time as Monarch.......

We start today's anniversaries with the subject of my last post, I posted about this yesterday but we can still get more out of the story of the real MacBeth, ask most non-Scots to name a Scots king and they will eventually remember this fellow Macbeth, who murdered a kindly old man for his crown, egged on by his shrew of a wife who then went crazy and killed herself. Or you can tell them the snippets you pick up from the likes of this and others true stories about the real man.

While Macbeth lived, his name as a warrior-prince must have carried some weight among the other rulers of the countries within reach of Alba, his Scotland. Because of its situation between Scandinavia, England, Ireland and the continent, Alba was a place of strategic importance. In Macbeth, it seemed to find a capable and imaginative king who held the throne in disturbed times for 17 years and was able, indeed, to leave his shores for a very long time without fear of upheavals behind him – something his English contemporary, Edward the Confessor was never able to do, so it shows his, and perhaps, Scotland's standing on the continent of Europe carried more weight than our southern neighbours.

In fact, Macbeth went to Rome – an event about which Shakespeare knew nothing. We know the date – 1050 – from the chronicle of an Irish monk writing in Germany; and we know that Macbeth was free with his gold when he got there, scattering his alms ‘like seed’ To me this was some feat for a man from what was still perceived as a savage like nation like Scotland, or Alba, as it was still known as in those days. He may have visited Rome as a pilgrim. His reasons were more likely to do with the benefits a Roman association might offer a country backward in development, which had hitherto relied on the care and protection of the Celtic pastoral Church.

Macbeth and his kingdom stood at the hub of a power struggle in which the Norse and the Danes, the Holy Roman Emperor and the Saxons of England, the Normans and Flemings and the Celts of Brittany, Cornwall, Wales and Ireland all played a part, with the pope in Rome courting them all.

What of the eponymous real villain of the Shakespearean play, Lady MacBeth, well by all accounts she appears to have been a loyal and blameless lady. From a previous marriage, she brought him a stepson, Lulach, who Macbeth seems to have cherished, and who was crowned king after Macbeth, before being killed in his turn. Nor was she ever called Lady Macbeth. Macbeth, meaning ‘Son of Life’ or ‘of the Elect’ is not a surname. The king’s wife would have been addressed as the lady Gruoch in Gaelic. The name is recorded in Fife where she and her husband are said to have gifted land to the Celtic monks of St Serf’s island, Loch Leven.

And of course we can't talk about "The Scottish Play" as it is known in theatrical circles, as saying the name of the play is said to be back luck for those thespians, The Witches, well Hollinshead, he of the chronicles I spoke of yesterday, wrote about three women ‘in strange and wild apparel’, who promised Macbeth the thanedoms of Cawdor and Glamis as well as the throne, and who informed Banquo that his heirs, and not Macbeth’s, would rule Scotland. So you can see where Shakespeare stole the idea from. Don't hold that against the Englishman though, all the best storytellers get inspiration from other places, our own Walter Scott, Robert Burns and James Hogg the "Ettrick Shepherd" all used material gathered from ancient tales. Also the present castles of Glamis and Cawdor have no connection at all with this part of Macbeth’s story – indeed, there were no stone castles in mid-11th century Scotland, only halls and fortifications of wood. Nor can the ‘blasted heath’ and the ‘witches stone’ beside Forres be anything but inventions provoked by the legend.

If there were no prophecies, and no evil Lady Macbeth, why did Macbeth killed Duncan and Banquo, if not to seize the throne and prevent Banquo from founding the royal line? For this part we have to blame another man the Scottish philosopher and historian, and the first Principal of King's College in Aberdeen, a man called Hector Boece.

Boece comes in with the character of Banquo, Macbeth did not kill Banquo because Banquo did not exist. By the 15th and 16th centuries, when Boece was plying his trade, Scotland was a very different place to the one we see MacBeth in. The Stewars were in control, and on the surface they did not want to be seen as warriors, like our hero today, others like Duncan, to paper over the cracks in the story of Scotland's turbulent violent past, Boece used by James IV to paint the Scots in a better light, in doing so he greatly maligned the real Macbeth. The work was well received at the time, both in Europe and in Scotland. I'm not entirely sure about how Banquo came about, but that apart, by the time of the Stewarts, no one wanted to remember that once, kingdoms had to be ruled by men who were war-leaders, and thrones fell to the strongest and most worthy, and not automatically to the first-born. They certainly didn't want to remember that Alba may have been ruled by a bastard King, it disguised the fact that the line founded by Duncan sprang from an unorthodox marriage, to an abbot called Crinan. A murky business in Boece's time, best left alone!.

Finally we get to the end of the Shakespeare play and Birnham wood, where Macbeth was finally slain by the Scots lord Macduff, whose family Macbeth had caused to be murdered.

Again, in history, there was no MacDuff. The final fight in the play is based on The Battle of Dunsinane, Macbeth's army was defeated by Malcolm Canmore (Máel Coluim mac Donnchada) with the help of the aforementioned English King Edward the Confessor, It was said that MacBeth’s guard surrounded him and defended him as best they could but they were defeated 3000 – 1,500, but MacBeth eventually got away to safety and spent the next 3 years on the run.

After Dunsinane Malcolm attended a meeting of the mormaers who elected MacBeth’s step son Lulach as king – perhaps thinking that MacBeth was dead – or that it was time to move on – who knows? Malcolm, of course, was not happy about this, seeing as he had fought really hard to win. He still had a support from the English soldiers, so he chased Lulach, if the king was not to be him, then he would kill whoever it was. And Lulach was caught and killed by Malcolm, another victim in the long line of murdered Scots kings. As far as killing their kings went, the Scots seemed to be pretty good at it, perhaps better than the English.

And so we reach the point of this post and three years after Dunsinane, MacBeth was finally cornered and killed at Lumphanan, his 17 year reign coming to an end. If there has to be a moral to this story it is ‘you will get yours eventually," it certainly mirrored Shakespeare in that way, if not others.

So Macbeth's Scotland may have very well been a place without towns or proper markets or roads, but his administration was clearly good for its time, however it needed later Norman-trained rulers and the help of the Church to develop what he had started and become a more peaceful nation, but remember, he wasn't the scheming power hungry monarch, egged on by an ambitious wife, but a good King who oversaw a a relatively peaceful time in our formation as a country.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wet-nurses were clearly a source of anxiety. In his Scotorum Historiae of 1527 Hector Boece had warmly commended the practice of mothers breast-feeding their own children. Like his friend, the great Renaissance scholar, Erasmus, he believed that such nourishment was as important as the nurture of the womb, but wet-nurses remained very much in demand. Bessie Roy was accused of having abstracted and transferred to herself the breast-milk of a poor woman whom she distinguished as a rival for her services. When her victim threatened to expose her heinous deed, Roy contrived to restore the supply. She clearly specialised in birth and child-rearing.

- Edward J. Cowan, “Witch Persecution and Folk Belief in Lowland Scotland: The Devil’s Decade” in Witchcraft and Belief in Early Modern Scotland (2008)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Keaton, Carrington, Milligan: 2

Keaton, Carrington, and Milligan all encounter a similar type of crisis in their ability to pursue their art. The effect on them as creative individuals, and their attempts at solutions, however, are very different. For Keaton, it’s the encroachment of the studio system on his practitioners’ realm, that space in which vaudeville evolves into silent comedy: he first embraces silence, then, as the…

View On WordPress

#Buster Keaton#Hector Boece#Historia Gentis Scotorum#Holinshed#John Bellenden#Leonora Carrington#MacBeth#Shakespeare#Spike Milligan#Steamboat Bill Jr#The Goon Show#The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction#Walter Benjamin

0 notes

Text

Lia Fáil

Also known as the Stone of Destiny or Speaking Stone

Some Scottish chroniclers, such as John of Fordun and Hector Boece from the thirteenth century, treat the Lia Fáil the same as the Stone of Scone in Scotland.

According to this account, the Lia Fáil left Tara in AD 500 when the High King of Ireland Murtagh MacEirc loaned it to his great-uncle, Fergus (later known as Fergus the Great) for the latter's coronation in Scotland. Fergus's sub-kingdom, Dalriada, had by this time expanded to include the north-east part of Ulster and parts of western Scotland. Not long after Fergus's coronation in Scotland, he and his inner circle were caught in a freak storm off the County Antrim coast in which all perished.

The stone remained in Scotland, which is why Murtagh MacEirc is recorded in history as the last Irish King to be crowned on it.

However, historian William Forbes Skene commented: "It is somewhat remarkable that while the Scottish legend brings the stone at Scone from Ireland, the Irish legend brings the stone at Tara from Scotland

0 notes

Text

“The election of MacBeth began seventeen years of seldom interrupted peace, north, south and west, and seventeen years of prosperity and plenty. All of the contemporary historians talk of those prosperous untroubled years of MacBeth’s reign. St. Berchan described him as ‘the liberal King’. And Andrew de Wyntoun, writing 350 years later, echoes this sentiment, saying “all hys tyme was great plente [i.e. well spent]. Aboundand both in land and sea. He was in justice rycht lawfull” [...] Later still, Holinshed borrowed the sentiments which Hector Boece had originally taken from Wyntoun, saying ‘Thus was justice and law restored again to the old accustomed course by the diligent means of MacBeth’s. He seems to have been a uniformly popular High King during his seventeen year reign.”

Malcolm D. Broun, ‘MacBeth, King of Scots, 1040-1057,’ in Journal of the Sydney Society for Scottish History, Vol. 8 Nov 2000, p. 21.

we stan macbeth in this house.

0 notes

Photo

alliterative morte arthure, unknown author/john bellenden’s edition of hector boece’s historia gentis scotorum/essay by kara l. mcshane on the questing beast/coral lumbley, geoffrey of monmouth and race/george gregory molchan, mordred: treachery, transference, and border pressure in british arthurian Romance/emerson storm fillman richards, an unhappy knight: the diffusion and bastardization of mordred in arthurian legends from select works of the sixth through the fifteenth centuries

#finny.txt#arthuriana#mordred#arthurian legend#racism#ask to tag#THE M IN MODRED STANDS FOR ETHNIC MINORITY AND IF YOU SAW THIS BEFORE NO YOU DIDNT I WANTED IT TO POST INT HE TAG#translation of am by me

5 notes

·

View notes