#her competence as a pilot also wasn’t questioned in last issue’s story by the other characters

Text

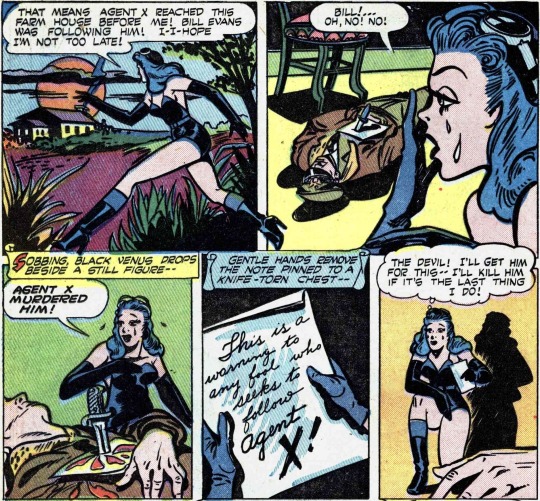

Contact Comics (1944) #2

#I’m intrigued by the gender politics of this#as Black Venus this character is essentially taking on the role of an official pilot#while her tracking down the body of this pilot and then vowing revenge for his death has a romance framing#I think it’s also a kind of narrative that’s commonly used for ‘brothers in arms’-type characters#her competence as a pilot also wasn’t questioned in last issue’s story by the other characters#and there and here it’s not being remarked upon that she flies well for a woman in the narration#I like that Black Venus cries when she finds the body and then directs those feelings into#‘I’ll get him for this- I’ll kill him if it’s the last thing I do!’#also the Agent X that murdered the pilot is revealed to be a woman#when Black Venus learns this she’s really startled#and Agent X says ‘Don’t let that deceive you! I can still defeat you!’#she does not actually as Black Venus succeeds in murdering her#also it seemed to me that this pilot was not the same primary love interest from the first story that stood out from all the other pilots#so I was thinking that Black Venus' civilian job as a U.S.O. girl would give her a revolving door of love interests#but then at the end of this story she dramatically declares that because of this pilot’s death#‘From now on no matter how many people are around me I will always be alone!’#/if/ they actually maintain that she’s swearing off romance then that would be an interesting conflict with her job#aviation press#black venus#my posts#comic panels#racist language tw

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Classic Doctor Who (S2E1) - Planet Of Giants [spoiler review]

After many months and numerous extended breaks from watching the very first season of Doctor Who (or at least what I was able to watch), originally aired in the latter months of 1963 and through most of ‘64, my impression of the show in its infant stages is that it seemed to want to lean into being quite educational and to show historical events from around the world, while also showing off a bit of space travel as well. With a number of episodes missing from this season, it’s difficult to get the full picture but I’d say I liked it just enough to finish it and begin season 2. The problem I have with these early episodes (or serials) is that each is composed of multiple parts. It’s like in a school test where the teacher tells you there are only 8 questions, meanwhile each question has other sub-questions so for this show the end result winds up being 2-7 sub-episodes for each complete story: a serial. For comparison, each sub-episode is around 24 minutes long so an episode with 6 instalments will roughly take as much time as three modern era Doctor Who episodes, but tell just as much of a story as one of them. Going into season 2 is a similar affair, with its first serial, Planet Of Giants clocking up to only three episodes in total, which I feel is a nice way to ease someone into the show. But is this story any good?

Planet Of Giants deceptively takes place in what I can only assume is the 60’s equivalent of modern day Earth, where companions Ian and Barbara belong. It is not in fact a different planet inhabited by giants, which was a little disappointing, but The Doctor has a cloak now, so it’s all good. The twist however is that the Who crew has been shrunk due to the doors of the TARDIS opening before they’ve fully landed. They explore the land a bit; Ian gets lost; a man dies; all the bugs are being killed from insecticide; everything goes crazy and the gang have to find Ian and also stop the murderer before getting back to the TARDIS and returning to their normal size. This episode is more or less decent in terms of the quality of the show at the time and overall I would say I enjoyed it.

Everything in these sets have to be bigger than the main crew composed of The Doctor, Susan, Ian, and Barbara in order to realistically depict how small they all are and it works a treat. Everything looks super cool. These set and prop designers had to make huge match boxes and sink plugs and insects that moved and what have you, for the characters to interact with. I had a lot of fun watching these scenes play out and see the way the environments were utilised. Certain details are set up that seem quite smart, such as the idea that they, as tiny people, wouldn’t be able to talk with regular sized people due to it sounding much in the way a mouse would sound to us. Or that exposure to insecticide would harm them a lot more than it usually would due to their immune system being too small to combat such a relatively high dose.

A common issue I’ve noticed with these early Doctor Who episodes is that the writing can often be quite bad. I don’t mind these characters at all but the things they have to say is at times difficult to take seriously. An example of this is an interaction between The Doctor and Ian.

Doctor: “Yes, that’s it! We’ll cause trouble! Start a fire, my boy!”

Ian: Yes, but can we start a big enough one to do any real damage?”

Doctor: “Well we can try anyway, hehe, there’s nothing like a good fire is there!? Hahaha!”

Like what the hell? I mean don’t get me wrong, that was hilarious when I heard it but it’s not meant to be. It makes The Doctor sound like a maniac!

A recurring detail of this show that I’ve noticed so far is that characters often stumble on their line delivery. They will audibly get mixed up with words or start a sentence, get it wrong, then redo it. In this day and age, it isn’t something I’d tolerate, but here… it’s almost charming. I’m amazed that I don’t mind it. With the film they were using to record the show, I doubt they had the money to stop scenes simply because of a slight line mix up, which would have required a lot more editing and wasted money to account for more film reel, so I can understand why these mistakes are left in. To compare it to, say, Selfie From Hell, the worst movie from 2018 I’ve seen so far, when the woman says “He is really a bad man” in a fake whimpering voice, it served to be ten times worse than any instance of a character in Doctor Who literally messing up a line and saying it again. With Selfie From Hell being filmed on digital, there’s no excuse not to re-record with better acting and writing. So I suppose with older media, I afford some leniency in that sense.

The characters themselves, as I said, I don’t mind. Having watched the newer episode, ‘Twice Upon A Time’ at the end of Capaldi’s run, I expected Hartnell’s Doctor to be infuriating with how misogynistic and out of touch he is in that episode but he is nowhere near as bad as in Twice Upon A Time and I understand now why there was such an influx of people defending him. Don’t get me wrong, there are elements of those traits with Hartnell’s Doctor and sometimes it gets to be rather “eeehh” but mostly he’s played without that being a defining part of his character. If I had to describe the first Doctor, I’d say he was quite playful but strict at times and he definitely loves these adventures but he’s more focused on educating himself from a scientific point of view with each new challenge that comes along, rather than getting stuck into the cultures.

Susan, The Doctor’s granddaughter is someone I needed time to adjust to over the first season. As it stands now, I do like her as a character. I think there’s a lot of mystery behind her, what with mentioning her and The Doctor’s home planet a couple of times. At first, she really grated on me because any time anything would go wrong, she would scream. It hurt to listen to. She still does it in Planet Of Giants but I’ve learned to tolerate it.

Ian and Barbara are decent. After every outing, they think they’re going to be taken back home and that’s basically the through-line to every episode so far. Every time they open the TARDIS doors, they think they’re going to be back where they belong but each episode is an elaborate way of telling us that The Doctor has no idea how to pilot the TARDIS. Generally, they’re okay with going on these adventures and they do take joy in it but the need to go home always evaporates when they get to a new environment.

Unfortunately in more than a few instances, Ian and The Doctor are seen to be more competent than Barbara and Susan which I wish wasn’t the case, but it is more of a symptom of the time it was made and it could have been a lot worse.

As an episode, there’s not a whole lot to say. Planet Of Giants is fun and relatively short. It falls victim to a lot of recurring problems as well as some specific to this episode. There’s not a lot of spatial awareness when it comes to getting characters from one place to the next. The music hits very suddenly when anything that could be considered ‘scary’ happens. Like a stick falling over. I think it succeeds at what it wants to do however. The plot is slightly secondary to the fact that the characters are small now and everything else is big which I don’t mind too much but I’d have liked to have seen a more interesting story being told. As the first episode in the series, it does a good job at letting people know what the show can be about, but as this aired at the end of October in 1964, there wasn’t much of a gap in between seasons, as the last episode of season one aired mid-September during the same year so this feels relatively the same in terms of the overall quality of the episodes. As one of the shorter serials, I’d recommend Planet Of Giants if you fancy having a taste of how the show was back in its early days with the very first Doctor and the very first companions.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Supernatural Season 12 - the Mary Winchester storyline

Of all the ridiculous things… I’ve fallen down the Supernatural rabbit hole.

Supernatural is the last fandom I’d have expected to sneak up on me. I stopped watching years ago and had been wishing that someone would put it out of its misery.

But then a few weeks ago, my friend mentioned that Sam and Dean’s mother was on the show as a regular character. It piqued my curiosity. A story that’s actually about the Winchester family, not the internal politics of Heaven or whatever random boring nonsense that caused me to stop watching?

So long story short - I was just in Shanghai (for the third time!) and when I wasn’t running around a dark hotel or drinking at a bar, I was waking up at 5am, jetlagged and half drunk, mainlining SPN. (Watching it in bed on my phone! Ha.)

To my complete shock, seasons 11 and 12 are GREAT. It's like the show took stock of everything it was doing wrong, remembered what had once made it awesome, and set about methodically fixing it.

If you are someone who also gave up on the show - watch 11x04 “Baby.” It made me laugh, made me cry, made me literally want to hug my television. It was such a gift to the audience, and a promise to do better. Proof that the show can still be absolutely wonderful when it puts in the effort.

Also, Dean Winchester. He’s one of the best fictional characters I’ve ever seen; he's so fucked up and he's also the most lovable thing ever. His combination of strength, fragility, competence, darkness, sweetness, silliness… His heroism and idealism and fatalism and self-abnegation… His joie de vivre, suicidal impulses, bitterness, weariness, ridiculousness and awkwardness… His badassery and heroism and codependence and tragedy.

Such a complex beautiful mess. Narratively, he is the gift that keeps on giving, the reason the show has lasted twelve years - you can just keep throwing stories at him and you get the most fascinating results.

I will be writing more about SPN. Sorry if you’re just here for the immersive theatre posts!

Here are my thoughts on the Mary Winchester storyline, which I LOVED -

It’s a complex, messy, fascinating story, where nobody is completely right and nobody is completely wrong, and you can sympathize with every character. It brings the show right back to the core of what made it good and interesting.

The three key things I loved about it:

I was pleasantly surprised at how it subverted my expectations

Mary herself was relatable, interesting, complex, and her choices raised intriguing ethical questions

Mary’s presence provided an opportunity to dive into the psychology and issues of Dean (especially) and Sam in a way we haven’t seen before

As soon as I heard that Mary was back, I was simultaneously afraid of the ways it could go wrong, and deeply intrigued by the possibilities it raised.

The most interesting thing the show had going on in its early days was the complexity of the boys’ relationship with their father. The success of Jeffrey Dean Morgan’s career was a tragedy for Supernatural - once he was gone it just never had the same emotional intensity, though they did interesting things with flashbacks and time travel and pseudo-father figures.

But Mary - Mary has that same intense emotional resonance. She was the first character we saw in the Pilot, Dean’s deepest wish (in arguably the best episode of the show, 2x20) and Dean’s Heaven (5x16), the key to Dean’s character.

"I know [my mother] wanted me to be brave. I think about that every day. And I do my best to be brave." - Dean from 1x03 - what an amazing through-line to a story still unfolding twelve years later!

But… Supernatural doesn’t have a great track record with female characters. The original sin of the show - the reason I’ve always been a bit ambivalent about loving it so much - is how it portrays women as symbols that matter only in relation to men. The Pilot is egregious. Mary and Jess, in their ridiculous frilly white nightgowns, dying as motivation for the men to embark on their quests. In Supernatural, men have journeys. Men are subjects, with destinies, and “work to do.” Men are multi-dimensional characters. Women are objects (in the early seasons - it’s gotten way better recently). We barely know Mary and Jess as characters, and don’t need to. Their deaths are not even about them; they’re about what they do to Sam and Dean.

Usually when Mary reappears in the show, it’s as a symbol, the embodiment of the ideal of motherhood. The love, safety, and care that Dean longs for. (Sam, interestingly, does not long for Mary the same way, both because he doesn’t remember her and because he had Dean as his mother figure. I have always adored that parallel, that Dean is like Mary and Sam is like John, which so subverts our expectations of how they present their gender roles, tough guy Dean and sensitive Sam.)

So my fear of season twelve was that we’d still see Mary a symbol. And THANK GOD they were smart enough to completely subvert that expectation, and make the story ABOUT the fact that Mary is an individual human being, not an ideal personification of motherhood.

When we meet this version of Mary, her whole world has been taken from her. Her husband is dead, her small children are lost to her. Her friends are thirty years older, or dead. I love how the show handles Mary’s reaction to the ubiquity of smartphones. It’s not a joke about moms being bad at technology. It’s profoundly disconcerting. It’s sad and strange, especially for a person so smart and competent to suddenly be in a world where she lacks foundational knowledge - it’s almost like everyone else speaks another language. She doesn’t fit.

So she tries to find her way. She’s a fully-realized person, just as conflicted and complex as Sam and Dean, with her own goals, flaws, fears, vulnerabilities. (And THANK GOD she’s tough, not in need of her childrens’ protection.)

I imagine myself in her position - with these two well-meaning, overwhelming adult children tracking her every move - and I completely understand her need to break away and carve a space for herself. The pressure and weight of their expectation, on top of everything else she’s going through, would be overwhelming.

As with the best writing in Supernatural, Mary makes choices that are not entirely wrong and not entirely right. Her embrace of the British Men of Letters is driven by guilt that her deal with Azazel destroyed her childrens’ lives, and her own need create a purpose for her life in this strange new world, and a sincere belief that it really will make the world a better place. It’s the same kind of complex psychological motivations that would drive Sam or Dean. (I have a whole other post brewing about that storyline, and about the unique and brilliant way that Supernatural’s handles moral ambiguity.)

Mary’s reaction to her adult children was so unexpected, but so right. One of those character-deepening twists that make perfect sense in retrospect.

Mary struggles with Dean, and connects more with Sam. This is what I mean about Supernatural being great at subverting expectations - because we’ve spent the entire series knowing that Dean is the one most shaped by Mary - the one who remembers her, who dreams of her, who longs for her, who can’t even say her name without flinching. And Sam is the one who doesn’t remember her - who tells Dean in the Pilot “If it weren't for pictures I wouldn't even know what Mom looks like.”

But it makes perfect sense. Sam, without the weight of a lifetime of expectations, treats Mary as an individual and tries to understand her needs. Dean struggles to see beyond what Mary means to him, and what he needs from her. Dean’s love is overwhelming, and suffocating.

There’s this great line in season twelve - I can’t remember where, but it’s when Sam and Dean are talking about the British Men of Letters, not quite agreeing or disagreeing, and Sam says something like “I know you think [whatever]” and Dean interrupts and says “WE think.” (Sorry, I need to rewatch and dig up the quote.) It’s borderline abusive, and it must be exhausting for Sam, to live with someone so overbearing that you’re not even allowed to have a different opinion.

The whole season deals with Dean’s abandonment complex - going right back to the heart of the Pilot, “I can’t do this alone.” Dean is so afraid of being abandoned that he clutches his loved ones way too closely. We understand and sympathize because we know where it came from - the death of his mother at four, the neglect from his father, twelve seasons of everyone he loves dying - but that doesn’t mean he would be easy to live with.

The line that kept running through my head when watching Dean this season is from Marilyn Manson - “When all of your wishes are granted, many of your dreams will be destroyed.”

Mary’s return is an incredible opportunity for character exploration and character growth for Dean. In many ways Dean is emotionally stuck at the age of four, unable to move on from the loss of his mother. He’s finally forced to recognize that his perceptions from that time were a tiny sliver of the truth, a four year old’s limited view. Maybe these dreams need to be destroyed. You can’t live your entire adult life longing for the cocoon you were in when you were four. (Or, I mean you can, you’d be Dean Winchester, but it’s not healthy.)

Dean needed his mother’s love AS A FOUR YEAR OLD, and it’s devastating that it was ripped away from him, but for his own sanity he needs to move on. I love that Mary flat out tells him that he’s not a child anymore. He needs to hear it.

The other side of the story is Dean’s perspective, which is incredibly sympathetic. Supernatural does a brilliant job telling a complex story where no one is entirely right or wrong. Dean tries so hard. He knows he’s weird and socially awkward. He doesn’t want to scare Mary away. He wants so desperately for their relationship to work. The scenes of him angsting over what to text her are some of my favorite moments ever in the show. It’s so surreal and yet so truthful.

And I have to admit - as much as I loved Mary NOT functioning as stereotypical mother figure - I also LOVED when she finally found out how tragic the boys’ childhood was. It was completely cathartic for me as an audience member. Those boys went through more than any child should have to bear. Dean is so scarred by it, and he’s this amazing person so full of love and compassion and this beautiful vibrant light that has been twisted by these awful experiences he’s been through, and the audience has been watching him suffer for twelve years, longing for the equivalent of his mom to give him a hug. (Just look at the bazillions of hurt/comfort fanfics.) The emotional payoff of that validation finally happening from his actual mother is enormous. Intense, and it would be indulgent if it wasn’t so EARNED.

I love that in their big conversation at the end of the season, Dean phrases it as all about what SAM went through. Of course the entire audience is watching that scene going BUT DEAN. It’s Dean that Mary saves. It’s actually all about him, but he’d never say it. Brilliant writing.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ring of Keys and Other Stories VI

A/N/SUMMARY fun fact: i finished the first draft of soulmate/soulbond in a day. which should tell you that i feel very nice about this fic and it’s my favorite bc of that. set in yavin 4 between eadu and scarif in the canon timeline. inspiration also comes from one of my most favorite films and love stories of all the love eterne (whose influence is also in the last fic if you know where to look)

RATING/WARNINGS pg or smth idk/n/a

WORD COUNT 3,484

AO3 here

—

The hangar bay was empty. There were no technicians, no rebels, no ragtag crew standing around, screaming and shouting at each other near the cargo shuttle they’d commandeered from Eadu. After the long journey from Jedha, after the life and death situations they’d put themselves through, there being no other path to take, the silence and the emptiness were suddenly so jarring. That was the point that Baze realized that an empty hangar bay with an empty cargo ship with no soul to speak of was the picture definition of depressing.

How apt that he should choose this point in his life to philosophize when he’d pretty much lost what was equivalent to everything. His past, his home. About the only reasons why he was still standing on his own two feet were Chirrut Imwe and the rebel crew they were suddenly a part of. So did that make those idiots his friends?

Baze chuckled suddenly, but they weren’t as bad as they looked; the captain turned out to be competent, his droid the same, the girl managed to earn his respect and even the pilot hid a little fire in himself. People like that, he could learn to appreciate.

Besides, Chirrut seemed to like this dysfunctional group. People Chirrut liked, Baze could learn to like, as well. Where was Chirrut, anyway? Alliance Intelligence—or whoever it was who debriefed them—couldn’t be all that interested in the life of a blind man, could they? Unless they’d made the mistake of asking Chirrut about the Force.

The thought almost made Baze want to laugh if he just didn’t feel so stupid doing it alone where no one else could hear. He decided to wait for Chirrut outside in the hangar bay, exploring its high walls, the panels and screens, and the toys—parts, really, and tools and equipment—lying around, out in the open where they could kill a person, safety warnings be damned. When he’d run out of pipes and plates to knock his fist on, he decided to move onto the open cargo shuttle and tour himself. He was familiar with its interior of course from the days he was away from Jedha. The layout and terminals were all pretty much standard issue (he realized then that the Empire, for all its invasiveness, didn’t quite bother personalizing all their possessions) that he didn’t need more than 10 minutes to reacquaint himself to the ship.

He stepped out. Still no Chirrut. Which volume of the journals was he at now? A deep sigh escaped Baze as he wandered over to a heavy turbine on its side that must be about his height, propped atop two ridged transformers that must be big enough to contain a child each. He sat down on one of them where he could best keep an eye on the entrance to the bay. Folded himself forward to get comfortable, praying hands finding his nose and his mouth.

Before he could stop himself, he closed his eyes and started to breathe deeply. In spite of his divorce with the faith, meditation was still a large part of his life. It was a difficult habit to break, having been a part of his daily routine in the days of the Temple, and even as a skeptic, he could find some nugget of peace with himself in it. His red armor wrapped around his collar made it a little difficult to focus, but it could be managed.

Could be forgotten with the rest of the gray hangar, the echoes of footsteps, of distant commands, the fragrance of leaves, of the strange forests that surrounded them, that seemed inescapable. But there he was, floating in the void of his own emptiness, away from the world and alone…

He heard him first before he saw him, as always—like a drop of water that sent a ripple all across his senses and roused him from his deep trance. Baze felt like a statue coming to life after a long century of slumber. His eyes opened to the sound of his steps and the tip of his staff—and true enough, when he turned, he was there, smiling as he would, a female pilot at his side, all but ready to lead this blind man by the hand. Little wonder then that Chirrut should look quite happy and amused. He felt the familiar tugs of his own smile knocking on his cheeks but self-consciousness squashed that like a bug. The flush of relief was an entirely different species, though, and he permitted himself that much.

He folded his arms on his lap while he watched his friend’s progress. The woman caught sight of him, then.

“Oh your friend’s here,” she announced. She was young, idealistic by the tone of her voice.

“I know,” Chirrut assured her. Then with a theatrical whisper that was meant to be carried out to the audience, he leaned to the pilot and explained, “I can smell him from here.”

“I heard that!” Baze snapped.

The pilot looked like she was caught between laughing and blushing but she powered through. “Can you find your way from here? He’s just straight ahead.” She even pointed to Baze on the occasion that the blind man could see her.

“I can do straight ahead,” Chirrut assured her pleasantly. “Thank you, Shara.”

She waved to the sightless man and then to Baze who lifted his brow. While she hurried back the way they came, Chirrut started forward with his uneti staff held away at an angle, one end at the ground. Snakes of cables and discarded canisters and valves littered his path but he kicked away those he could and hopped over those he couldn’t. Baze watched with no expression.

Once Chirrut arrived, he stretched out a leg to mark his finish line. The younger man didn’t stop walking until it hit his tummy. A hand wrapped itself around his ankle on instinct lest he overbalanced. Chirrut’s fat cheeks restrained a laughter from within.

“You want to sit? What took you so long?” Baze asked with a frown, shifting aside while Chirrut tested the side of the transformer with one foot, and then the turbine’s frame next to it.

With hardly a breath of warning, he flew in two kicks, turned in the air and landed quite impressively on his ass. “I got lost along the way,” Chirrut answered cheerfully, staff meeting the ground with a sound tap. “It’s a big place and I took the wrong turn.”

“Mhm.”

“Did you see the giant water fountain in the middle of this base? It’s so huge, it’s big enough to fit a full-grown Hutt!”

“I’m sure.”

Chirrut clicked his tongue and frowned. “You’re no fun.”

Well, Baze was also sure of that.

He clipped Chirrut’s ear between his fingers and yanked it down. Chirrut yelped, catching his ear before it fell off. He started laughing again.

Baze shook his head, smiling slightly at the blind man. “What sort of questions did they ask you?”

“I think they were mostly concerned about whether or not I was a Jedi,” Chirrut said. He frowned after, tilting his head to one side, brows knotted in deep conversation. “Now I wonder if I should have just said yes. I think they were looking to hire me. That would have made a good income.”

“What use is a good income if you’re going to be dead before you spend it?” Baze asked, one brow up again.

Chirrut turned to return to him the same expression. “I guess you haven’t figured that out yet, have you?” Baze responded by jabbing the side of his head with a strong finger. Chirrut grinned impishly. He knew he got him there. “Well, what did they ask you?”

“They were interested about my cannons.”

“Were they looking to hire you for that?”

Baze frowned, the corners of his lips pulled low. He shrugged and said, “Who knows?”

“Well, it’s definitely not for your winning personality.”

Definitely not. Baze smirked and nudged the man beside him. “You know I’m expensive.”

“Sounds just like the thing a jobless man would say.”

This time he snickered with his cheeky partner. When he shoved him sideways next, it was with the fullest preparation of meeting Chirrut’s blocking forearm, which felt not unlike slamming into a wall, even as Chirrut was shaking with laughter. It felt good to be talking like this again—as if the entire galaxy wasn’t about to come down on them, as if they hadn’t been quite literally chased out of their own home. A home they no longer had.

It hit him then that this was the second time they’d lost a home. He couldn’t say which was worse, though. The first time had been harder, but this time, there was nothing and nowhere they could go back to. No street, no rubble, not even a piece of carpet on which to sleep.

He didn’t even know what was going to happen to them from here on out. A leaf in a storm would probably be a good analogy to their present situation. They’d survived Saw’s rebels, they’d survived the Death Star—one of the few who could say that—and they’d survived the Empire and the Alliance on Eadu. Now they were stuck here in Yavin 4 for no other reason than that they were dragged along. They had no choice. It was run or die, sink or swim.

Baze wasn’t one to panic—that had always been one of his greatest strengths even when the galaxy was already giving him every reason to tear his hair off, screaming. But he wasn’t young anymore and he wasn’t getting any younger either. This life of constantly fighting for food, shelter, survival, day in and day out…it wasn’t meant to go on forever. Just when he thought he’d finally figured it out for Chirrut and himself, here comes a death ray destroying everything they’d built. And then they were back to square one again.

He heaved out a great sigh, staring into nothingness. “How did we get here?” he asked, wearily.

He wasn’t really expecting any answer, but apparently questions were part of Chirrut’s expertise. Bless the man really for still finding reason to smile in spite of their circumstances. Head tilted a little towards his partner, he said, “It’s the consequence of being alive.”

That was true, and Baze was glad for it. Being alive meant more days of worrying and fighting but it was far better than being dead and non-existent. In fact, death and non-existence would be far worse. Baze could never do that to Chirrut—leave him alone again to fend for himself in this vast galaxy, just because this time he’d been too slow, too weak, too stupid. Just because he’d failed. Jedha had already given him too many names to pray for, sagging him under their weight. He’d heard him muttering them even in his sleep, on the flight to Eadu from the ruins of Jedha. That was enough.

“What do you think happens now?” Baze asked.

Chirrut shrugged. “Who knows? No one can tell the will of the Force, we can only follow it. The Force led us to the Holy Quarter to rescue Jyn. It brought us to Eadu for the same reason. Now we’re here.”

“So you think we’re all here just to,” Baze was the one who shrugged this time, “protect Jyn?” He nodded to the entrance to the hangar. “She looks like she gets into too much trouble for her own good, but not someone who needs a sitter. Much less two.” Besides, he was already looking after one fool who liked to fling himself headlong into battle. He wasn’t sure he needed another.

“I think we’re here for another reason,” Chirrut said, furrowing his brows, looking like he was inspecting his dangling feet. “The Force brought us to these people for a reason.”

“You saying the Force wants us to join the Alliance?” Baze’s brows flew.

“Not the Alliance,” Chirrut explained quietly. “But the rebellion.”

His meaning was plain to Baze, but the man still found enough reason to pretend that it wasn’t. In all the time they were running and fighting, he never felt that cold hand of dread wrapping itself around his heart. Funny that it should come now, when they were supposed to be safe among friends. Besides, wasn’t this what he’d been dreaming of in the past? A chance to finally bring revenge to the Empire’s doorstep.

“You think…Jyn is going to keep fighting? No matter what the council says?”

Chirrut raised his eyes to look blindly ahead of him. “I know she will.” He had seen through her heart of Kyber.

Well, that was it, wasn’t it? The truth as plain as day. Whatever it entailed, he didn’t know—but Baze knew for sure that he could finally breathe in relief. The uncertainty had lifted, and the inevitable has come. Now he knew what they were going to do. And what he was going to do.

Whatever gave him the idea, he couldn’t say. Probably some childhood tale from all those old holocrons, during the days they were still learning verses. But whatever it was, it made him glad that he kept a piece of blade in one of his many pockets, and that they’d gotten into the habit of salvaging whatever could be reused and repurposed while they still had the chance.

Baze reached back to his wavy, oily locks and carefully snipped off a finger’s width. The crisp sound drew Chirrut’s attention towards him, like a bird turning so suddenly. “What’s that?” he asked, curious.

“None of your business yet,” Baze muttered, looking for something to pin his hair in.

Chirrut nudged him with a toothy grin. “You’re my business.”

Baze eyed him incredulously. “Are you trying to look cute?” he asked. “Now’s an inappropriate time!”

“I wasn’t saying anything like that,” Chirrut said, sulking like a boy and doing well at it. He was always so good at impressions. He made a bed for his chin with his two hands on his staff and pouted at an unseen object.

Baze snorted, shaking his head and smiling slightly. Eventually, he managed to produce a synthetic red cord from one of his other pockets which he tied around one end of his lock of hair, making it easier to knot the rest in a nice and tight braid. Chirrut started humming a song soon after, tapping the heels of his shoes to the transformer in different configurations to provide the beat to his rhythm. Baze always thought that he had a good singing voice, that he could carry a tune.

He was in the middle of a second repeat of the song when Baze finally jumped off to his feet and told him, “Give me your hand.”

“In marriage?” Chirrut asked, jesting. Excitement filled his smile at the opening Baze had walked right into. He sighed, but that only caused Chirrut to grin wider. Baze couldn’t say if the blind fool would ever get tired of these jokes. He didn’t think he ought to, of course. “We’ve been through this a number of times, Baze.”

“We’ve been through this a number of times!” Baze echoed him to agree although their contexts were definitely different from each other. Chirrut held out his left hand anyway, the one without the impeller gauntlet, and Baze draped the length of his braided lock over the back of his wrist. He made a few measurements and a few quick adjustments with the cord and the end knot.

It didn’t take him long to finish the bracelet after, wrapped loosely around Chirrut’s pulse. It was his hair woven and stitched with the cord, locked with a complicated knot he’d learned from the streets. “There,” Baze said, wiping his hands on his suit and putting away the blade and the little that was left of the cord. “Now you can look.”

Look, of course, was a subjective command here. Chirrut’s idea of looking was running his finger down the plaited locks and testing its width. His brows met in intrigue. “This is…” He brought the bracelet to his nose and sniffed the familiar smell. “Your hair!”

“Mhm.”

“This means ‘til death do us part.” The gravity of which was not lost on Chirrut, who stared perfectly straight at Baze in surprise, as if his milky blue eyes had been suddenly cured.

Baze gave him a small smile. “It seems that you know what’s going to happen now, and I think I do, too—but I’m not the one who’s attuned to the Force here.”

“Baze…”

Baze scratched his head briefly, feeling the part where he’d taken his hair. “The point is,” he continued, “and I know this is a redundant symbol, but whatever happens now, what’s important to me is that you’ll always have a part of me with you.” He slid his hands onto Chirrut’s palms and let the man hold him.

Looking at his blind eyes, he said, “I just can’t bear the thought of you alone without me.”

He always loved the kind of smile that Chirrut put on every time he bared his soul and opened up his weakness. It was at once shy, at once comforting, but the entirety of it was drawn by a deity of love. “Stop being silly,” he chided him softly. “When you left, you came back—because there’s no world that can exist without you beside me. The Force brought us together. And what the Force brought together, no creature, no worldly thing can separate.”

He raised a hand and laid it lightly on the side of Baze’s face, stroking his tired skin. Baze wanted to close his eyes and pour himself into the softness but he wanted to look at Chirrut’s face, too. “Where would I be without you? Nowhere. It’s a fallacy, Baze. It simply won’t work.” His smile stretched out wider, and Baze grinned back.

They kissed, Baze pulling his chin towards him, Chirrut’s breath shuddering under his mouth, eager to pour out the same love through his lips. It was mind blowing, an embarrassment towards them, how little they’d shared a kiss since they escaped Jedha. It was no wonder they were constantly so starved for each other whenever they were alone, no matter how long they spent together or how hard they kissed. Damn the Death Star if it thought it could get in the way of all that was good to them. It may take away their home, their family and friends and past—but they would kill it first before they let it separate them permanently.

Baze pulled free with a wet smack and a heavy breath pouring out of his mouth. Chirrut was catching his own heart even as they connected their foreheads to each other.

“No matter what happens,” Baze growled, looking closely at his love, “I’ll never leave you. I promise.”

“You can’t!” Chirrut reminded him, laughing. They kissed again, hands on their cheeks, lips in perfect unity. They kissed sweetly with the bliss of a reunion after such a long parting. Nothing mattered in their little pocket of the galaxy. Not the heat, not the scent of fuel or of alien trees in the forests.

Not the hurrying footsteps and the excitable, “Mr. Malbus, Mr. Imwe!” Sadly, the shouting was an entirely different story altogether.

The end to such a perfect kiss came abruptly, flesh torn so rudely without the last negotiations for more. “I’m sorry! I didn’t know, I didn’t see!” the visitor cried.

It was a rebel at the entrance to the hangar bay, waving his hands to the Guardians while he averted his eyes, as well. Baze looked at him with immense disappointment while Chirrut sighed, head bowed low. “Y, you can forget I’m here,” he insisted stubbornly. “I, I was just looking for the captain—!”

“Didn’t your mother ever teach you how to knock?” Chirrut demanded sharply, using the voice of an angry parent. The rebel started to stammer again but that was only because he couldn’t hear Chirrut gasping for breath and see his cheeks aching from grinning. Baze groaned, ducking under a hand to hide his own mirth from the poor flustered man.

“I, I said I didn’t see it, okay? I didn’t see it!!” Which made Baze wonder what he thought he was seeing. Well, too late for that, Chirrut was already laughing uncontrollably. What a shame. And that had been a very good kiss. Probably the last they’d have in a while.

They’ll get another chance after all this is over. He swore that on all the stars above them.

“A, anyway!” The rebel persisted stubbornly, even though he was blushing like the lavas of Mustafar. “Where’s Captain Andor! They said he was looking for volunteers.”

#spiritassassin week#spiritassassin#rogue one#chirrut imwe#baze malbus#liv does sa week#seaofolives original#sa fic

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

News and important up-dates on POS System Equipment & POS.

Go-go boots clattered across the tarmac as a group of young women scrambled into place at Dallas’s Love Field airport. The boss wanted a photograph. “Okay, girls,” said Lamar Muse, the president of Southwest Airlines. “Y’all smile.”

It was 1971, and Southwest had recently put its first official flight into the air. Muse asked a group of “hostesses,” as the flight attendants were then called, to pose for a snapshot he planned to send to Harding Lawrence, the CEO of Dallas-based airline Braniff International.

Lawrence was a bitter rival. He’d spent the prior three years waging a legal war to prevent Southwest from ever getting off the ground. But the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed one final appeal by Braniff in December 1970, clearing the runway for Southwest.

“Get ready,” Muse said to his smiling hostesses, each of whom was clad in her in-flight uniform of tangerine knit top, slouchy white belt, white side-laced go-go boots, and fire-orange hot pants. “Now, everyone flip Mr. Lawrence the finger.”

Hostess Sally Glenn couldn’t believe what she was about to do. “Oh, my goodness, no,” she thought to herself. She imagined what her mother back in small-town Illinois would say to her if she saw the picture. Yet, like everyone’s around her, Glenn’s fist went up, her middle finger unfurled, and Muse stuck it to his adversary. “Lamar had a way of getting you to do things you might not think you could,” recalls Glenn (now Glenn-Lee) from her home in California, fifty years after Southwest Airlines flew for the first time.

Fifty. Five-O. No one who was there for the start-up of Southwest Airlines can quite believe that much time has passed. No one can believe how successful their irreverent little company has become, either. “I wish I’d had enough money to buy the stock in the early days,” says Gene Van Overschelde, one of the original pilots and the first head of Southwest’s pilots union. If he’d put just under $1,000 into the company’s stock in 1978, he would have more than $1.5 million today.

Van Overschelde had figured Southwest might last six months competing against much bigger, much better-financed airlines. But as six months stretched into five decades, it outlasted most of its rivals. Braniff, along with dozens of other airlines, went broke and disappeared. Meanwhile, Southwest prospered, posting profits for 47 consecutive years—a streak broken only in 2020 by the COVID-19 pandemic. The company’s success spawned copycats and forced its competitors to change in hopes of keeping up. The whole world of passenger flight transformed as a result. “There’s no question Southwest Airlines has had a profound influence on the entire airline industry,” says Bob Crandall, now retired, who made plenty of history of his own as the longtime CEO of Fort Worth–based American Airlines.

Indeed, no frills and low fares were once “The Southwest Way.” Now no matter who we fly with, most of us fly that way—whether we like it or not.

The pandemic might have ended all that success for Southwest. It still might. Last year, the airline lost money—billions of dollars—for the first time since 1972. Still, its leadership is optimistic that the skies will clear as early as this year. They nurture that faith by looking to Southwest’s past. “Our history gives us confidence,” says Gary Kelly, Southwest’s CEO. “We know that as long as we stick together, we can fight our way through challenges.”

It’s true enough that Southwest has overcome daunting challenges before. On the day in January 1971 when Lamar Muse became employee number one, Southwest had no real offices, no staff, no gates, and no planes. It owed about $100,000 to its attorney, Herb Kelleher, and it had a little more than $100 in the bank. But 143 days later, on June 18, 1971, Southwest Airlines somehow had $7 million in cash, three brand-new 737 jets, gates at three Texas airports, a staff of more than two hundred, and a maiden flight barreling down the runway at Love Field.

To understand Southwest’s subsequent success, it helps to know how the airline got off the ground in the first place. It’s a story that involves Mad Men and lawmen, rats and pigeons, love machines and love triangles, and, of course, hot pants.

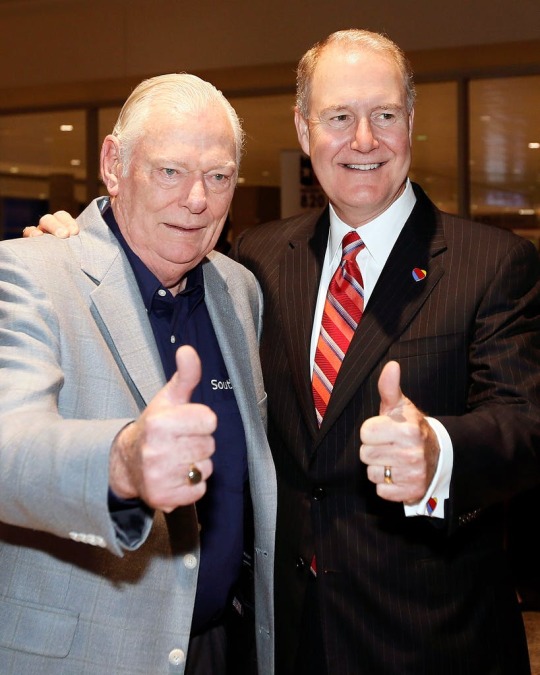

Southwest founder Rollin King (left) and then-president Lamar Muse at Love Field in 1974Courtesy of Southwest Airlines

I ’m about to buy some DC-9s,” Lamar Muse told a Boeing executive over a pay phone one afternoon in mid-March 1971. “But I’d rather buy from you.”

Six weeks after he was hired, Muse was at the headquarters of Douglas Aircraft in Long Beach, California, looking to cut a deal for Southwest’s first planes, three Douglas DC-9s. Muse would have preferred the Boeing 737-200, which first rolled off the assembly line in 1968 and had six seats per row, compared with the DC-9’s five. But at nearly $5 million a plane, barely-in-business Southwest couldn’t afford Boeing’s jet.

Southwest still had no employees other than Muse, a bespectacled 51-year-old with a head of silver hair, and a matching wisp of a mustache, who’d grown up in the East Texas town of Palestine and spoke with a distinctive drawl. He’d been an executive at several carriers, including Continental and American. He’d also run Universal Airlines from 1967 to 1969 before quitting after sparring with the company’s board.

Working out of a room at the Hilton Hotel on Central Expressway in Dallas, Muse had zigzagged Texas peddling stakes in a debt offering—a sort of a corporate bond that would pay investors back with interest if the airline succeeded. Most of the boldfaced names of that era of Texas business turned him down. Houston oilionaire Hugh Roy Cullen passed. So did Lamar Hunt. But John Murchison, a co-owner of the Dallas Cowboys, took two stakes, as did six others, including Muse himself. On March 10, Muse put their combined $1.25 million in the bank. (The deposit slip from the transaction is on display at the Frontiers of Flight Museum at Love Field.)

That was enough money to buy jets, if Muse could negotiate a favorable payment plan. In the lobby at Douglas’s sprawling Long Beach offices, he waited by the pay phone for his contact at Boeing to call him back on that day in mid-March 1971. As Muse, who died in 2007, recalled in his autobiography, Southwest Passage, he knew he had Boeing right where he wanted it.

There was a recession in 1971, and three customers had just canceled orders for planes Boeing had already built. The aircraft were sitting on a tarmac, unpainted but ready to fly. So Muse strong-armed the Seattle plane maker, offering unprecedented terms while he was standing on their competitor’s turf. Boeing caved. It sold Southwest the three 737s for $4 million each, with no money down.

It’s hard to know how aviation history might have turned out if Lamar Muse hadn’t had a few dimes in his pocket to make a call that day. Southwest is the biggest customer for 737s, and the airline’s success helped popularize that plane around the world.

Muse was determined to get Southwest flying by the start of the summer. The rush was understandable. He needed to begin generating revenue as quickly as possible to offset the substantial costs of running a company whose primary assets weigh 57,000 pounds and move at 500 miles per hour.

There might not have been such urgency had Southwest not already had such a bumpy ride. Soon after Herb Kelleher filed the incorporation papers in March 1967, competitors moved to block the upstart airline with multiple legal challenges that, in essence, suggested Southwest had no legal right to exist. The assault lasted three and a half years, until the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear from Braniff.

Southwest was branded “the love airline.” Tickets were issued from “love machines.” In-flight snacks were “love bites.” The drinks were “love potions.”

Southwest’s founder, Rollin King, had anticipated the competition trying to keep his airline grounded because its business model threaded a loophole in federal regulations that others couldn’t. At that time, a federal agency told airlines when and where they could fly, as well as what they could charge passengers. Those regulations led major carriers to focus on long-haul customers and to structure their route networks as “interline” service, operating like passenger trains that make multiple stops between two endpoints. “One of Braniff’s so-called commuter flights in Texas actually originated in Frankfurt, Germany,” King told me over breakfast at the Mansion on Turtle Creek in Dallas in 2006.

But airlines operating solely within the borders of one state could avoid the onerous federal regulations. Southwest could fly wherever and whenever it wanted within Texas and charge fares cheap enough to get Texans out of their cars and into the skies.

King’s idea (which he’d unapologetically borrowed from two intrastate carriers in California, Air California and Pacific Southwest Airlines) was hardly simplistic, but a much-repeated version of the Southwest origin story makes it seem otherwise: In the fall of 1966, King meets his lawyer, Herb Kelleher, in the bar at San Antonio’s St. Anthony Club. They discuss the idea of a commuter airline in Texas. On a cocktail napkin, King sketches the business plan—a triangle representing the cities of Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio, which the airline would serve.

A business plan on a cocktail napkin? Whoo-whee, those boys in Texas were crazy! As the story goes, Southwest Airlines was infused with the pair’s freewheeling, quirky spirit, and therein lies the secret to its success.

Except there never was such a pie-eyed plan penned on such paper. King, who died in 2014, told me as much during that Mansion breakfast. “A number of things that have been said about the early years were not true,” he said.

To cite another instance of mythmaking about Southwest, other than his proclivity for profanity, King wasn’t exactly quirky. In 1966, he was a 36-year-old, mostly buttoned-up native Clevelander with a Harvard MBA who’d moved to San Antonio in 1964 and worked as an investment banker. And it was years before Kelleher, a New Jersey transplant to Texas, became the famously joking, chain-smoking, Wild Turkey–swilling embodiment of Southwest’s much-copied corporate culture. “Herb was just the attorney,” remembers Jan Lightfoot-Evans, Southwest’s first “chief of hostesses” and part of the original 1971 team. “He was nice, and he was fun, but at that time he was not yet a persona.”

Lamar Muse might not have been a persona either in 1971, but he did have much to do with crafting the corporate persona of Southwest Airlines—with a little help from a team of ad men.

Amid his fund-raising blitz, in February 1971, Muse went to see a 31-year-old named Ray Trapp at the offices of Bloom Advertising on South Akard Street in downtown Dallas. Trapp had previously worked in the Mad Men–era world of New York advertising. He fancied three-piece suits and monogrammed cuffs, and his gold Mercedes-Benz 190SL was worth more than the entirety of Southwest’s assets.

Muse wanted the airline’s brand to stand out in the market. “We felt the other carriers were stodgy. Southwest needed to be livelier,” says Trapp, now 81 and working at Infinity Investment Banking in Dallas. To start, the Bloom team developed what’s known as a personality description model. It defined Southwest as a young woman. “This lady is young and vital,” it read. “She is charming and goes through life with great flair and exuberance … yet she is quite efficient and approaches all her tasks with care and attention.”

The Bloom concept for an initial branding campaign was to portray Southwest as “the love airline.” Trapp claims that had nothing to do with the company’s headquarters at Love Field, which is named for an early Army aviator who died in a training crash. Rather, it was simply because, in 1971, love was hip. There were still plenty of flower children around suggesting people “make love, not war.”

So the Bloom team wanted to spread love all over Southwest. Tickets would be issued from “love machines.” Snacks would be “love bites.” The free in-flight drinks would be “love potions.” Southwest would also serve passengers its own craft cocktails, including such drinks as the Kentucky Matchmaker, the Pucker Potion, and the Lucky Lindsay.

Those branding concepts informed not just Southwest’s marketing but also the airline’s hiring decisions. “We wanted a fun, casual attitude to be part of each flight,” Trapp recalls. “We were going to look for hostesses who were fun and outgoing. They had to have a sense of humor. They had to have an engaging personality.”

While Bloom was helping Southwest to cultivate this image of a laid-back attitude that remains integral to the airline’s public face today, news came in early April that Purdue Airlines in Indiana had decided to shut down. Purdue was launched as a teaching airline by the university of the same name but had been purchased by an investor and was faltering. With its impending closure, 22 jet-certified pilots, several operations specialists, and a few dozen flight attendants and mechanics would all, unexpectedly, be on the job market just as Southwest was eager to hire experienced crews.

Dick Elliott, Southwest’s just-hired chief of marketing, was on the ground at Purdue Airlines’ headquarters before Lamar Muse even knew he’d left Dallas. He met with the soon-to-be-jobless flight attendants and blurted out, “Well, look, you’re all wonderful, and you’re all hired.”

Purdue’s head of flight attendants, Jan Lightfoot-Evans (her name was Jan Arnold in 1971), was shocked. She recalls recently from her home in Dallas that she pulled Elliott aside that day and told him that some of the flight attendants had been skirting rules. “Your new airline can do things fast if you want, but you also have to respect rules and regulations, or I’m not going to be a part of it,” she told Elliott. He promptly modified his earlier offer. In the end, only a few of Purdue’s flight attendants made the trip to Dallas.

To fill out the first group of 38 flight attendants, Southwest ran its first-ever ad in May 1971. Written by Trapp’s team, it was a help-wanted missive titled “An Open Letter to Raquel Welch.” It read, in part, “Ms. Welch: You typify the girls we’re looking for: Warm, personable, and great-looking in hot pants. … If you know of any other girls like you (at least 20 years old, 20/50 vision, without glasses, between 5’2” and 5’7”, 100-135 pounds) … would you please ask them to send us a brief statement of qualifications and a recent photograph?”

In the context of the times—when selling the sex appeal of all-female crews of flight attendants was an industry norm—the ad might not have come off quite as sexist as it reads today. Regardless, it generated 1,200 applications. Dozens of hopefuls, among them models and beauty pageant winners, were selected for interviews. “We wanted to find out whether they could engage with the customers, ninety percent of whom we knew were going to be men,” Trapp says.

The hostesses were expected to make those men feel at home. Baytown native Jill Cohn (then Jill Allen—she later married original Southwest pilot Sam Cohn, who died in 2012) remembers that after she was hired, “The executives said, ‘We’ll get the passengers on board, then it’s your job to make them come back.’” That’s why Southwest asked each flight attendant to spend about three minutes talking to each passenger on board every flight.

But the interviewers weren’t just interested in the prospective hostesses’ ability to sustain conversations. They were also unapologetically after women who would look great in those revealing hot pants.

Southwest flight attendants in the nineties. Their uniforms have changed noticeably since 1971.

Courtesy of Southwest Airlines

Southwest’s planes were originally painted a color the airline called desert gold but that some employees dubbed “baby shit brown.”

Courtesy of Southwest Airlines

Debbie Muse Carlson (then Debbie Muse), the twenty-year-old daughter of Lamar Muse, was among the interviewees who wasn’t fazed by that requirement. She had taken leave from her studies at Vanderbilt University to join her father in his new business. She says she got the job because of her family connections, just not the connections you might expect. “You had to have great legs to be a hostess,” Muse Carlson told me from her home in Dallas. “Luckily my mother had great legs, and I got great legs from her.”

Juanice Muse, Lamar’s wife and Debbie’s mother, made her own contribution to the start-up effort. She was on the design team for the first hostess uniforms. Hot pants were a key feature early on, but the original prototype was more revealing than Juanice could accept. “The scoop neck on the sweater was cut so low that it would have revealed a lot,” recalls Muse Carlson. Juanice objected, saying, “My twenty-year-old daughter is going to be wearing this uniform. I will not allow her to wear something that revealing. The hot pants should be sufficient.” The neckline went up.

Inside the terminal, and out on the tarmac, the hostesses wore a safari skirt and jacket that covered even more. “Once we closed the airplane door and started taxiing,” Cohn says, “we took those off, and we just had our top and our shorts on. When we landed and we were taxiing again, we put the skirt and jacket back on.”

Sally Glenn-Lee remembers Lamar Muse telling her, “If someone wants to see the hot pants, they’ve got to buy a ticket.”

Just one month and one day before the first flight was to take off, Karson Druckamiller, a mechanic hired from Purdue, arrived at Love Field for the first time. He’d forgotten where, exactly, he was supposed to report, so he pulled over his car and asked someone for the location of the Southwest Airlines offices. He recalls the reply: “They said, ‘Who is Southwest?’”

Fifty years later, no one asks that question anymore. Druckamiller is 73 now, and he’s the last original employee remaining on the payroll. He plans to retire this year in honor of the company’s fifty-year anniversary. “It’s been the best place to get up and go to work for every morning,” he says.

The first thing Druckamiller and the other mechanics had to make work was Southwest’s lone hangar at Love Field. A Quonset hut—a semicylindrical, lightweight steel structure—built during World War II, it hadn’t been used in decades, and its doors had rusted shut. After hours of welding and hammering, the mechanics discovered sand clogging the sliding tracks that took two days to clear before they could get the doors open. “Then we had to chase all the rats and the pigeons out,” says Druckamiller, who spent 27 years in Dallas before relocating to Tampa.

In mid-May 1971, the first of Southwest’s three 737-200s headed to Texas from Boeing’s Seattle factory. The airline’s unique paint scheme wasn’t a hit with some of the original employees. The planes featured a primary color Southwest called desert gold but that some employees immediately dubbed “baby shit brown.”

Herb Kelleher didn’t seem to mind the clashing colors. He’d say in later years that he walked up to the first jet and “kissed that baby on the lips and cried.” He also might easily have gotten himself killed that day.

As a crew was checking out the plane, Kelleher, sporting pork chop sideburns, stuck his head inside one of the engines. A mechanic yanked him out. Kelleher knew little about the operation of the engines, so he had no idea the danger he’d put himself in. “If that thrust reverser goes off,” Kelleher later recalled the mechanic telling him, “it will decapitate you.”

The Federal Aviation Administration required new airlines to log fifty hours in the air with each plane—so-called proving runs—before using them for passenger service. With just fifty or so minutes of flying time between the cities in Southwest’s “love triangle” of Dallas, San Antonio, and Houston, that meant the airline needed to run about ten flights per day, per plane, if it was going to be ready by June 18.

That was a lot for an airline that was still training its flight attendants at a nearby Holiday Inn and that still had pilots working on a simulator in Denver. “But there was never any thought that we couldn’t do it,” Lightfoot-Evans says. “So there were no weekends. We were a family, and we trusted each other, and we were just going to get it done.”

“Lamar, if the sheriff shows up, you push the first flight out on top of him,” Kelleher said. “Roll right over that son of a bitch, and leave our tire marks on his back.”

It all almost came undone anyway. On June 16, the same day the first flight-attendant class graduated with its FAA certifications, Braniff and Texas International Airlines persuaded a Travis County district court judge to grant a restraining order that would ground Southwest. When Muse found out, he called Southwest board member John Peace, a lawyer in San Antonio who served on an advisory board for the Supreme Court of Texas. Peace happened to be on his way to Austin to a reception honoring the justices, and he promised to talk to them there.

Meanwhile, Herb Kelleher had just wrapped up days of meetings with the Civil Aeronautics Board in Washington and was on his way back to San Antonio, with a layover in Dallas at Love Field. Muse told Southwest’s dispatch office at Love Field to redirect one of the 737-200s to prepare for a proving flight to Austin. Then he sped over to the main terminal at Love Field to get Kelleher on that Southwest plane.

Whatever Kelleher and Peace did in Austin worked. In a hearing less than 24 hours before Southwest’s first flight, the Texas Supreme Court temporarily suspended the restraining order. Muse asked Kelleher what the airline should do if a lawman showed up the next morning to serve the restraining order anyway. “Lamar, if the sheriff shows up, you push the first flight out on top of him,” Kelleher said. “Roll right over that son of a bitch, and leave our tire marks on his back.”

On June 18, 1971, at 6:30 a.m., as captain Emilio Salazar and first officer Bob Pratt shook hands and posed for pictures with Dallas mayor pro tem Ted Holland on the Love Field tarmac, the sheriff was nowhere to be found. A crew of five climbed up airstairs to the plane, followed by just ten paying passengers. Exactly one piece of checked luggage was loaded into the cargo hold. The plane taxied away and took off at 7 a.m., right on time.

The day was hot, which made for a bumpy ride. Working the back of the cabin, Debbie Muse Carlson felt both nervous and ill. She’d been so well-known in her family for getting queasy on flights that she’d shocked everyone when she said she was going to be a Southwest hostess. As the plane approached San Antonio, she locked herself in the bathroom and threw up.

“Debbie, you are never going to throw up again on an airplane,” she told herself. “This is the last time for as long as you live. You are going to do this job.”

She kept that vow, and Southwest kept flying.

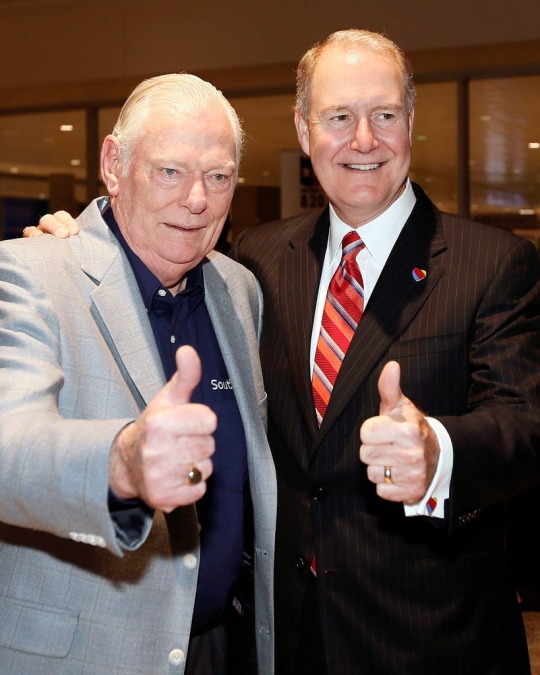

Herb Kelleher (left), Southwest’s legendary longtime CEO, was succeeded by Gary Kelly, who today faces the task of leading the airline’s recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.Brandon Wade/The Fort Worth Star-Telegram via AP

That first flight lost money, and two years of financial turbulence followed. But when Lamar Muse ended up in a fare war with Braniff and slyly won it by handing out free bottles of booze to passengers in something that came to be known as the $13 Fare War, Southwest’s bookings soared. The company turned its first profit and kept doing the same year after year. Then came the pandemic.

When the world locked down because of COVID-19, Southwest’s revenue plunged. In April 2020, it was down 92 percent compared with the same month the previous year. Tammy Romo, the company’s chief financial officer and a thirty-year veteran of Southwest, told me that she’ll never forget how horrible it felt to watch the steep decline in bookings. “I well up just talking about it,” she says. “I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, this is our company, our people. How can any company get through business falling off to that degree?’”

Revenue fell, of course, for every airline in the world. Southwest ultimately lost $3.1 billion in 2020, on revenue of $9 billion, which was about 59 percent less than its revenue in 2019. Southwest has survived, at least so far, because it entered the slump in a far better financial position than most of its competitors and because, along with them, it received billions of dollars in federal aid.

First, the financials: Southwest’s debt-to-equity ratio, a measure that indicates its borrowing power, was the lowest in its 49-year history going into 2020, and it had about $4 billion in cash on hand. Thanks to a robust 2019, that was about $1 billion more than normal. “But that still wasn’t enough cash,” Romo says. “I knew we would have to raise more money, and we’d have to do it fast because we didn’t know how long this was going to last.”

Southwest immediately borrowed $1 billion from a group of lenders in March 2020. Billions more followed, including money from Washington. As part of its Payroll Support Program for airlines, the federal government gave Southwest $3.2 billion last year. Another $1.2 billion has been handed over in 2021.

“It’s just hard to fathom that we would have been able to scratch our way through this without the government support,” says Kelly, who, along with four other company executives, took a 20 percent pay cut in 2020. “And I felt that if the taxpayers are going to support the jobs at Southwest Airlines, the least we can do is keep the jobs.”

That commitment wasn’t just to taxpayers. Southwest’s leadership has long maintained a “layoffs last” policy in responding to crises. In fifty years, it’s never furloughed workers involuntarily. Other airlines, even as they’ve adopted elements of “the Southwest way,” haven’t copied that part. Combined, the other major carriers announced plans to lay off 90,000 workers in 2020. Many of those employees have been recalled, but not all. Southwest, meanwhile, asked its workers to accept early retirement packages or voluntary leave—16,800 of them, or 21 percent of the airline’s total workforce, have taken one of those offers.

That gave the company an advantage when a significant uptick in air travel began in March of this year. Southwest’s staff was either on the job or on standby that month, and most of its fleet had been maintained and was ready to fly. In mid-March the airline added a thousand flights overnight to its daily schedule. By the end of April, the company reported $2.1 billion in revenue for the first quarter. That was still down 50 percent from the mostly pre-pandemic start of 2020, but Southwest posted a small quarterly profit of $116 million.

Having more of its employees waiting in the wings meant Southwest was better positioned to take advantage of the rebound in travel and make money doing so. American and United, which didn’t begin recalling pilots until April, both lost more than $1 billion in the same quarter, and JetBlue lost almost $350 million.

Winning the kind of cooperation Southwest often gets from workers is easier when you have a generous profit-sharing plan, as Southwest’s employees have had since 1973. But it also helps that they share a collective knowledge of the company’s history.

Every new employee attends an orientation session called FLY. It stands for Freedom, LUV, and You, and it teaches them how to live “the Southwest way.” This is the way: To be a Southwest employee, you must have three key traits, each of which is explained through lessons from the company’s past. One is a “warrior spirit,” born of the airline’s early battles with competitors, including those three years of litigation before Lamar Muse managed to get flights (and his flight attendants’ middle fingers) in the air. That warrior spirit also carried Southwest through the months after September 11, 2001, when employees took voluntary pay reductions and kept their airline solvent while other carriers cratered.

Another trait is a “fun-loving attitude,” a concept that Muse somehow infused into the airline from the start. And the third is “a servant’s heart,” which came from an appreciation that Herb Kelleher and former Southwest president Colleen Barrett shared for a concept that became known in the seventies as “servant leadership.”

It all sounds pretty cultish, but it seems to work. Yet FLY and Southwest’s other official corporate histories include some urban legends. One of those is Southwest’s origin story about the cocktail napkin. The company has also long struggled to give Muse enough credit for his foundational contributions. Muse left Southwest after a spat with King and started a competing airline called Muse Air, which Southwest eventually bought and lost millions on before shutting it down. The executive in charge of closing that business was a new hire named Gary Kelly.

Gary Kelly, fifth from left, joined executives from other major U.S. airlines in seeking an extension of federal pandemic aid in Washington, D.C., last September.Alex Brandon/AP

When Kelly joined Southwest in 1986, there were sixty planes in its fleet. “I really did have the sense that all the go-go years were behind us,” he says. “Boy, was I wrong.” Today the fleet includes 747 planes, all Boeing 737s, with many more on the way. In March 2021, Southwest inked a ten-year agreement with Boeing for a hundred 737-Max 7 jets. As an indication of how much the airline values its history, it announced the deal on March 29, exactly fifty years to the day after Muse closed on a deal to buy Southwest’s first 737s from Boeing.

The all-737s fleet is just one of the elements of Southwest’s strategy that hasn’t changed in five decades. It’s long been a cost saver in maintaining planes and training crews. With one type of aircraft, Southwest can have any mechanic, pilot, or flight attendant work on any of its flights on any given day. But also, as it has since 1971 and unlike its major competitors, Southwest has no assigned passenger seats, has only one class of service, and lets customers check two bags for free.

“Southwest really values the simplicity of that business model,” says Bob Mann, an airline analyst with R. W. Mann & Company and a former executive at American Airlines. “There are a lot of costs that creep in with complexity that they try to avoid.”

Still, not all of Southwest’s approach is immutable. Last year, before signing the new deal with Boeing, company leaders seriously considered the unthinkable—adding Airbus A220s to its fleet. In 2010, when it bought budget airline AirTran, Southwest grew significantly through acquisition for the first time, copying something other major carriers had been doing for years. The AirTran deal extended Southwest’s route map to look a bit more like its bigger rivals’ too. Southwest once flew only short-haul trips of about 250 miles and went no farther from Dallas than San Antonio. Now it flies an average trip of 750 miles, and its network extends all the way to the Caribbean island of Aruba. Southwest no longer shuns major airports. Just this year, the airline, which has dominated the smaller Midway Airport, in Chicago, added gates at O’Hare.

Southwest still refers to itself as “the love airline,” the slogan Ray Trapp and his ad men came up with in 1971. But these days it usually spells the operative term “LUV”—like its ticker symbol on the New York Stock Exchange. That seems fitting, given the industry titan the once-upstart carrier has become. In fact, if you look closely at how Southwest does business today, it’s not all that different anymore from the other major U.S. carriers, known in the industry as the Big Three—American, United, and Delta. But Mann says Southwest continues to operate with far lower costs, which enable it to charge lower fares. Well, sometimes, anyway. “Back in the beginning Southwest had low costs and low fares,” Crandall says. “But at the moment, and on any given day, any given route, they may or may not be the low-fare carrier. Low fares and low costs are not the same.”

In the beginning, Muse was manic about keeping costs low however he could: cramming corporate staff into a tiny office in the original-but-defunct passenger terminal at Love Field, demanding nonstop effort from all employees. Some of the first hostesses recall working six-day weeks. Five days were in the air, and one day was spent on the ground doing promotional work for Southwest—in hot pants, of course. “We didn’t question it; we just did whatever needed to be done to make the company work,” says original flight attendant Jill Cohn.

Fifty years later, with Southwest highly unionized, that kind of thing no longer, well, flies. But the company still touts the high productivity of its people as key to keeping costs low—or at least lower than those of the Big Three. Among other carriers, however, Southwest no longer boasts the lowest costs. Budget airlines such as Frontier and Spirit do.

Meaning that Southwest, with all its growth and within an industry that has adapted to the Southwest business model, is no longer what it once claimed to be—“the low-fare airline.” Kelly says the objective these days is for Southwest to offer not necessarily the lowest fares but “low fares with the best service.” Indeed, the airline consistently ranks at or near the top of influential customer-satisfaction rankings among all carriers.

Southwest emerged from 2020 with not just top marks for service but also a lot more airports to serve. The company launched an aggressive expansion, with seventeen new destinations—the most it’s ever announced in a single year. It now has gates not only at O’Hare but at Houston’s George Bush Intercontinental, Palm Springs International, and fourteen other airports that hadn’t been in its plans before the pandemic. In a normal year, Southwest wouldn’t have had the resources to expand so quickly. But with fewer flights operating because of slack demand, it could move planes and people to wherever there was business. “Sure enough,” Kelly says, “we were able to generate enough revenue so that it was actually adding cash and putting idle assets and idle employees to work.”

Expanding during a moment of crisis is also in keeping with Southwest’s history. “Every time the airline industry has recovered from an economic downturn or some other shock in the past fifty years, Southwest has come out much larger and stronger,” Mann says.

So what about the next fifty years? “Who knows?” Kelly says. “Maybe we’ll have flying cars or something. But I kind of doubt it. Here we are, fifty years after 1971, and we still fly the same type of airplane.”

This post was first provided on this site.

I trust you found the article above useful or interesting. Similar content can be found on our main site: easttxpointofsale.com

Please let me have your feedback below in the comments section.

Let us know what topics we should cover for you next.

youtube

#Point of Sale#lightspeedhq#point of sale#pos#shopkeep App#shopkeep Pos#toast Point Of Sale#toast Pos Pricing#toast Pos Reviews#toast Restaurant Pos#touchbistro Pos

0 notes

Text

News and important up-dates on POS System Equipment & POS.

Go-go boots clattered across the tarmac as a group of young women scrambled into place at Dallas’s Love Field airport. The boss wanted a photograph. “Okay, girls,” said Lamar Muse, the president of Southwest Airlines. “Y’all smile.”

It was 1971, and Southwest had recently put its first official flight into the air. Muse asked a group of “hostesses,” as the flight attendants were then called, to pose for a snapshot he planned to send to Harding Lawrence, the CEO of Dallas-based airline Braniff International.

Lawrence was a bitter rival. He’d spent the prior three years waging a legal war to prevent Southwest from ever getting off the ground. But the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed one final appeal by Braniff in December 1970, clearing the runway for Southwest.

“Get ready,” Muse said to his smiling hostesses, each of whom was clad in her in-flight uniform of tangerine knit top, slouchy white belt, white side-laced go-go boots, and fire-orange hot pants. “Now, everyone flip Mr. Lawrence the finger.”

Hostess Sally Glenn couldn’t believe what she was about to do. “Oh, my goodness, no,” she thought to herself. She imagined what her mother back in small-town Illinois would say to her if she saw the picture. Yet, like everyone’s around her, Glenn’s fist went up, her middle finger unfurled, and Muse stuck it to his adversary. “Lamar had a way of getting you to do things you might not think you could,” recalls Glenn (now Glenn-Lee) from her home in California, fifty years after Southwest Airlines flew for the first time.

Fifty. Five-O. No one who was there for the start-up of Southwest Airlines can quite believe that much time has passed. No one can believe how successful their irreverent little company has become, either. “I wish I’d had enough money to buy the stock in the early days,” says Gene Van Overschelde, one of the original pilots and the first head of Southwest’s pilots union. If he’d put just under $1,000 into the company’s stock in 1978, he would have more than $1.5 million today.