#immanence vs transcendence

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

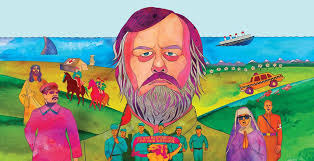

I was THRILLED to join my friend Luxa on Lux Occult Podcast Episode 70 to talk about Spinoza and the Sexy Dangers of Pantheism, Transdivinity & Agdistis! Won't you give it a listen?

https://anchor.fm/luxa-strata

https://linktr.ee/LuxaStrata

Rocket https://www.instagram.com/eyeandy/ joins Luxa to talk about Spinoza, Pantheism, the idea of a Transcendent vs. an Immanent divine (and what that translates into for humans). What does this look like when religious philosophy is translated into political doctrine? We also talk about Kabbalah (with a K), and why the Mysteries (with a capital M) must be experienced somatically rather than cognitively. Rocket shares about Jewish Mysticism, the upcoming Trans Rite of Ancestor Elevation https://trans-rite.tumblr.com/ their work with Agdistis and some of the mythology surrounding the godform whose gender was just too much for the Olypians (and how this ties into they mythology surrounding Dionysis). There’s a a tasty poetry snack created via cut-ups and gematria by Keats Ross of We the Hallowed https://wethehallowed.org/ which was used to find the track order for the audio offerings of Fuck Around and Find Out pt. 2 the digital mixtape (of which tracks are featured). There are also updates about the Green Mushroom Hyphosigil Project https://greenmushroomproject.com/. Much Love!

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Path to Human Rebirth

Reincarnation in Buddhism diverges from the notion of a person simply being reborn into a different physical form, such as John becoming a cat. Unlike the idea of a transmigration of an immortal soul, Buddhism emphasizes the interplay of karma, action, and the mind in shaping one's rebirth.

**Understanding Karma: The Moral Law**

Karma, rooted in the Sanskrit word "Kri," meaning action, is more than a chain reaction of cause and effect; it is a moral law. In the Buddhist context, karma extends beyond physical causation to encompass the moral implications of actions. The adage "A good cause, a good effect; a bad cause, a bad effect" encapsulates the essence of this moral law.

**The Conservation of Moral Energy: Karma as Transformation**

In the intricate web of existence, human beings emit both physical and spiritual forces. Drawing a parallel to the conservation of energy in physics, Buddhism asserts that spiritual and mental actions are never lost but transformed. Karma, therefore, is the law of conserving moral energy. Every action, thought, and word releases spiritual energy, influencing and shaping the circumstances surrounding an individual.

**Man as the Architect of Karma: Sender and Receiver of Influences**

Human beings play a dual role in the karmic process. As senders, they release spiritual energy into the universe through their actions, thoughts, and words. Simultaneously, as receivers, they are affected by the influences emanating from the collective karmic web. The entirety of these circumstances constitutes an individual's karma, leading to a constant state of change in personality and the surrounding world.

**Karma vs. Fate: The Power of Conscious Awareness**

In contrast to fate, which suggests a predetermined life beyond one's control, karma is dynamic and changeable. Human consciousness allows individuals to be aware of their karma and actively strive to alter its course. Quoting the Dhammapada, Buddhism emphasizes the profound influence of thoughts on shaping one's reality: "All that we are is a result of what we have thought, it is founded on our thoughts and made up of our thoughts."

**The Ten Realms: Psychological States and Rebirth**

Buddhism traditionally posits ten realms of being, representing mental and spiritual states rather than fixed, objective worlds. At the pinnacle is Buddha, followed by Bodhisattva, Pratyeka Buddha, Sravka, heavenly beings, human beings, Asura, beasts, Preta, and depraved men. Each realm is mutually immanent and inclusive, reflecting the psychological states created by thoughts, actions, and words.

**The Lesson: Aspiring for Human Rebirth**

The teaching of reincarnation in Buddhism imparts a valuable lesson. The realm one inhabits is a reflection of one's desires and motivations. To be reborn as a human being, one must transcend cravings for power, love, and self-recognition associated with realms like Preta or the hungry ghosts. Instead, cultivating qualities such as ethical conduct, mindfulness, wisdom, positive thoughts, generosity, and compassion paves the path to a favorable human rebirth.

In conclusion, the journey to human rebirth in Buddhism involves mindful navigation of the intricate interplay between karma, consciousness, and the dynamic states of the mind, steering away from the extremes and aspiring towards the cultivation of virtuous qualities.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Capitalism & Socialism: From Agrarian Nomadic Peoples

Agrarian Nomadic Peoples: These groups often reflect a lunar, matriarchal, and telluric (earth-bound) spirituality, contrasting with the solar, warrior-based ethos of traditional patriarchal civilizations.

Example of Germanic peoples:

Sun (Proto-Germanic sōwelō/sōwulō)

Runic Evidence: In Old Norse and Old English, the sun ᛊ / ᛋ is grammatically feminine.

Typically Feminine in early Germanic languages (e.g., Old English sunne, Old Norse sól).

Mythological Association: “Sun Mother" - The sun is often considered feminine, associated with warmth, life, and nurturing energy. Some myths describe the sun as a motherly or goddess-like figure.

Moon (Proto-Germanic mēnô)

Runic Evidence: The word is masculine ᛗ in Old Norse and Old English.

Typically Masculine in early Germanic languages (e.g., Old English mōna, Old Norse máni).

Mythological Association: “Moon Father” - The moon is typically viewed as masculine, linked to night, cycles, and sometimes war or hunting. The moon is personified as a male deity or warrior.

The sun (die Sonne) is grammatically feminine, while the moon (der Mond) is masculine—an inversion of the traditional solar-masculine and lunar-feminine symbolism characteristic of Solar-Uranian (Indo-Aryan) Civilizations. This linguistic structure reflects the dominance of Demetrian, gynocratic, and telluric forces within these cultures, marking a clear deviation from the sacred solar principle. Similarly, in the semitic language Hebrew, the sun (ha-shemesh) is feminine, and the moon (ha-yareach) is masculine.

Socialism and capitalism, as degenerate expressions of lunar spirituality, did not arise from Jewish influence but from Agrarian Nomadic Peoples. Chthonic-Demetrian peoples meaning Agrarian Nomadic Peoples are marked by democratic, egalitarian, and tribal structures, bound to the immanent and the terrestrial. In contrast, Solar-Uranian (Indo-Aryan) civilizations embody hierarchical order, verticality, and imperial grandeur, oriented toward the transcendent. Metaphysically, chthonic agrarian systems inevitably degenerate into authoritarianism and collapse, enslaved by materialistic forces and earthly determinism.

On the use of the term "Solar-Uranian (Indo-Aryan) Civilizations":

Julius Evola's use of the term "Solar-Uranian (Indo-Aryan) Civilizations" instead of simply "higher Indo-European traditions". Here’s why he preferred this formulation:

Solar-Uranian Symbolism: Hyperborean and Olympian Archetypes

Solar represents the Apollonian principle—order, hierarchy, clarity, and spiritual transcendence, linked to the Hyperborean myth of a primordial polar civilization.

Uranian refers to Uranus (Ouranos), the Greek sky god, symbolizing the transcendent, celestial, and masculine principle—detached from earthly chaos.

Together, they signify a warrior-priest ethos—active spiritual mastery, as opposed to passive "lunar" (telluric, chthonic, or matriarchal) civilizations.

Indo-Aryan vs. Generic "Indo-European"

Evola distinguished between Aryan (as a spiritual elite) and merely Indo-European (a broader racial-linguistic category).

"Aryan" in his usage denoted a sacred regal tradition—not just ethnicity but a metaphysical quality of divine kingship (the kshatriya ideal).

He saw later Indo-European cultures as decadent compared to the primordial Hyperborean-Aryan source.

Rejection of Modern Racial Theories

Evola criticized biological racism (e.g., Nazi Nordicism) in favor of a spiritual racism—where "Aryan" was a state of being (linked to the svabhāva of Hindu caste doctrine).

"Solar-Uranian" thus denotes an initiatic quality, not just bloodline. This aligns with his elitist, anti-egalitarian view of history.

Esoteric and Anti-Historical Perspective

Unlike mainstream scholars who treat Indo-European traditions as historical developments, Evola saw them as fragments of a lost Golden Age (Satya Yuga).

Metaphysical part:

The Swastika as a Polar Symbol

The deeper significance of the swastika transcends mere conjectures of modern scholars, connecting instead with a universal tradition found across Indo-Aryan, Hellenic, Egyptian, Celtic, Germanic, and even Aztec cultures. This symbol reflects not just a racial or solar motif but a metaphysical principle—rooted in the Hyperborean origins of the Aryan race.

The swastika is fundamentally a polar symbol, representing the immutable center around which cosmic order revolves. It embodies the "Olympian" spirit—unchanging, sovereign, and superior—contrasting the chaotic forces of becoming. Ancient traditions consistently associate the North with solar kingship, divine fire, and transcendent rulership. The Hyperborean Apollo, the Vedic hvarenô, and the Avestan airyanem waêjô all reflect this solar-polar archetype.

Unlike naturalistic interpretations, the swastika signifies not mere solar rotation but an axis of spiritual power—the cakravartî (world ruler) who governs from an unshakable center. This symbolism extends to sacred geographies: Delphi as the omphalos, Asgard as Midgard, and China as the "Middle Kingdom." The swastika thus marks the intersection of metaphysical centrality and historical dominion.

Herman Wirth’s error was conflating the pure Nordic-Arctic tradition with later, decadent "Atlantic" influences, introducing chthonic and maternal elements alien to the original Aryan spirit. True Nordic symbolism rejects cyclical dissolution (Dionysian passion, Loki’s chaos) in favor of Apollonian stability—fire not as a natural phenomenon but as a hieratic force.

The swastika, as svastika, encodes an affirmation: su-asti—"it is well." It heralds the resurgence of the primordial Aryan will against the encroaching darkness. For those destined to rule, it is the sign of the celestial wheel: dynamic yet centered, victorious yet unchanging.

The Hyperborean homeland may be lost to history, but its truth persists—accessible only through the heroic act of spirit. As Pindar and Li-tse taught, the path to the North is not traversed by ship or chariot but by the flight of the transcendent mind. The swastika, in its highest sense, points to this inner awakening—the return to the Olympian pole.

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) │ ├─ Anatolian (extinct) ├─ Tocharian (extinct) ├─ Italic → Romance (French, Spanish, Italian) ├─ Celtic (Irish, Welsh) ├─ Germanic (English, German, Dutch, Swedish) ├─ Balto-Slavic (Russian, Polish, Lithuanian) ├─ Hellenic (Greek) ├─ Indo-Iranian │ ├─ Iranian (Persian, Pashto) │ └─ Indo-Aryan (Hindi, Bengali, Punjabi) ├─ Armenian └─ Albanian

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) │

├─ Anatolian (extinct). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine).

├─ Tocharian (extinct). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine).

├─ Italic → Romance. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). Romance (All countries where Romance languages are spoken): Italy: Italian, France: French, Spain: Spanish, Portugal: Portuguese, Romania: Romanian, Moldova: Romanian, Switzerland: French & Romansh, Belgium: Walloon French, Andorra: Catalan, Monaco: French, San Marino: Italian, Vatican City: Latin & Italian. Minor/Regional Romance Languages: Italo-Dalmatian Dialects: Corsica (France): Corsican. Southern Romance Dialects: Sardinia (Italy): Sardinian Ibero-Romance Dialects: Asturias (Spain): Asturian, Galicia (Spain): Galician. Gallo-Romance Dialects: Cauchois (Normandy Mainland), Jèrriais (Jersey Norman), Lyonnais, Savoyard (Savoie). Occitano-Romance Dialects: Occitan (Southern France).

├─ Celtic (Irish, Welsh) Brittany (France): Breton, Wales: Welsh, Cornwall (UK): Cornish. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). Ireland: Irish Gaelic. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). Isle of Man: Manx, Scotland: Scottish Gaelic. → Total inversion: (Sun: feminine, Moon: feminine).

├─ Germanic (English, German, Dutch, Swedish). → With the exception of the Scots, all Germanic languages reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). Germanic (All countries where Germanic languages are spoken): Germany, Austria, Switzerland: German/Swiss German, Netherlands: Dutch, Belgium: Dutch (Flemish) & German, Luxembourg: Luxembourgish, Denmark: Danish, Sweden: Swedish, Norway: Norwegian, Iceland: Icelandic, Faroe Islands: Faroese, United Kingdom: English, Ireland: English. Extinct Germanic Languages: Burgundian, Gothic, Vandalic. Minor/Historic Germanic Languages: Alemannic Dialects: Alsatian (Germanic-influenced, North-East France). Anglo-Frisian Dialects: Frisian (Netherlands/Germany). Dutch Dialects: Afrikaans (South Africa/Namibia). Yiddish Dialects: Yiddish (historically spoken in Central/Eastern Europe).

├─ Balto-Slavic Balto-Slavic languages that do not invert the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine): Bulgaria: Bulgarian, North Macedonia: Macedonian, Russia: Russian, Slovenia: Slovenian. Balto-Slavic languages that reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine): Belarus: Belarusian, Bosnia: Bosnian, Croatia: Croatian, Czech Republic: Czech, Latvia: Latvian, Lithuania: Lithuanian, Montenegro: Montenegrin, Poland: Polish & Kashubian, Serbia: Serbian, Slovakia: Slovak, Ukraine: Ukrainian. Minor Slavic Languages: Sorbian (Germany): Upper Sorbian. Extinct Baltic Language: Old Prussian.

├─ Hellenic (Greek). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). Cyprus: Cypriot Greek, Greece: Greek.

├─ Indo-Iranian │ ├─ Iranian Afghanistan: Hazaragi & Pashto, Tajikistan: Tajik. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). Afghanistan: Dari, Turkey: Kurdish, Iran: Persian. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine).

│ └─ Indo-Aryan. → Dual Masculine Polarity (Sun: masculine, Moon: masculine). Bangladesh & India: Bengali, India & Nepal: Bhojpuri, India: Hindi, India & Nepal: Maithili, Nepal: Nepali, Sanskrit, Nepal: Tharu

├─ Armenian. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). Armenia: Armenian.

└─ Albanian. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). Albania: Albanian, Kosovo: Albanian, North Macedonia: Albanian minority.

Uralic. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). ├── Finno-Ugric │ ├── Finno-Permic │ │ ├── Finno-Samic (Finno-Saamic) │ │ │ ├── Samic (Saami) [Multiple living languages] │ │ │ └── Finnic (Baltic-Finnic) [Estonian, Finnish, etc.] │ │ └── Permic [Komi, Udmurt] │ └── Ugric │ ├── Hungarian (Magyar) │ └── Ob-Ugric │ ├── Khanty (Ostyak) │ └── Mansi (Vogul) └── Samoyedic (Living) ├── Northern Samoyedic │ ├── Nenets │ └── Enets └── Southern Samoyedic └── Selkup

Kartvelian (South Caucasian). → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). ├── Georgian │ ├── Old Georgian (extinct, liturgical) │ └── Modern Georgian (Standard, Imeretian, Kartlian, etc.) │ ├── Zan (Colchian) │ ├── Mingrelian │ └── Laz │ └── Svan ├── Upper Svan (Lentekhian, Ushgulian) └── Lower Svan (Lashkhian, Cholurian)

Proto-Semitic (around 3750–3500 BCE). → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). │ ├── East Semitic (Extinct). → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). │ └── Akkadian │ ├── Old Akkadian (around 2500 BCE) │ ├── Babylonian │ └── Assyrian │ ├── West Semitic. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). │ │ │ ├── Central Semitic │ │ ├── Arabic │ │ │ ├── Classical Arabic │ │ │ └── Modern Dialects (Egyptian, Levantine, Gulf, etc.) │ │ │ │ │ └── Northwest Semitic │ │ ├── Canaanite │ │ │ ├── Hebrew (Biblical → Modern) │ │ │ ├── Phoenician → Punic (Extinct) │ │ │ └── Moabite/Ammonite (Extinct) │ │ │ │ │ └── Aramaic │ │ ├── Old Aramaic │ │ ├── Syriac (Liturgical) │ │ └── Neo-Aramaic (Turoyo, Assyrian) │ │ │ └── Ethiopian Semitic (via migration) │ ├── North Ethiopic (Ge’ez → Tigrinya, Tigré) │ └── South Ethiopic (Amharic, Harari) │ └── South Semitic. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). ├── Old South Arabian (Extinct: Sabaean, Minaean) └── Modern South Arabian (Mehri, Soqotri)

Proto-Turkic (Root of all Turkic languages). → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). │ └── Common Turkic. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). │ ├── Oghuz Branch (Southwestern Turkic) │ ├── Turkish (Turkey, Cyprus, Balkans) │ ├── Azerbaijani (Azerbaijan, Iran) │ ├── Turkmen (Turkmenistan) │ └── Gagauz (Moldova, Ukraine) │ ├── Karluk Branch (Southeastern Turkic) │ ├── Uzbek (Uzbekistan) │ └── Uyghur (China, Xinjiang) │ └── Kipchak Branch (Northwestern Turkic) ├── Kazakh (Kazakhstan) ├── Kyrgyz (Kyrgyzstan) └── Tatar (Russia, Tatarstan)

Sino-Tibetan ├── Sinitic (Chinese languages). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). ├── Tibeto-Burman │ ├── Bodic (Tibetic) │ │ ├── Tibetan (Lhasa, Amdo, Kham). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). │ │ ├── Sherpa (close to Tibetan). → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). │ │ └── Tamang (Nepal). → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). │ │ │ ├── Himalayish. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). │ │ ├── Newar (Nepal Bhasa) │ │ └── Kiranti (e.g., Limbu) │ │ │ ├── Magaric. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). │ │ └── Magar (Nepal) │ │ │ ├── Lolo-Burmese │ │ ├── Burmese (including Arakanese, Intha). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). │ │ └── Loloish (Yi, Naxi, Lisu). → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). │ │ │ ├── Sal. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). │ │ ├── Jingpho (Kachin, Myanmar/North-East India) │ │ └── Achang │ │ │ └── Bai (Yunnan; debated—possibly an independent branch). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). └── (Other minor branches)

Tai-Kadai Language Family ├── Kam-Tai (Main Branch). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). │ ├── Tai Languages (Tai Proper) │ │ ├── Southwestern Tai (Thai-Lao Branch) │ │ │ ├── Thai (Siamese/Standard Thai) │ │ │ ├── Lao │ │ │ ├── Northern Thai (Lanna) │ │ │ ├── Isan │ │ │ └── Shan (Burma) │ │ │ │ │ ├── Northern Tai (e.g., Zhuang in China) │ │ └── Central Tai (e.g., Nung in Vietnam) │ │ │ └── Kam-Sui (e.g., Dong in China) │ └── Kra (e.g., Gelao in China/Vietnam)

Austroasiatic Language Family ├── Munda Branch (e.g., Santali, Mundari) — Spoken in East India. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). └── Mon-Khmer Branch ├── Khmer (Cambodian) — Official language of Cambodia. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). ├── Vietnamese — National language of Vietnam (though heavily Sinicized). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). ├── Pearic (e.g., Chong, Samre) — Small languages in Cambodia/Thailand. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). ├── Bahnaric (e.g., Bahnar, Tampuan) — Spoken in Vietnam/Cambodia. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). ├── Katuic (e.g., Katu, Bru) — Laos/Vietnam/Cambodia/Thailand. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). ├── Khmuic (e.g., Khmu) — Laos/Thailand/Vietnam. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). └── Other Mon-Khmer languages (e.g., Mon — spoken in Myanmar/Thailand). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine).

Proto-Dravidian (around 3000–2000 BCE) ├── North Dravidian. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). │ ├── Kurukh (Oraon) │ └── Brahui (Pakistan) │ ├── Central Dravidian │ ├── Telugu (Old Telugu → Modern Telugu). → Dual Masculine Polarity (Sun: masculine, Moon: masculine). │ └── Gondi (Tribal language). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). │ └── South Dravidian ├── Tamil-Kannada Branch │ ├── Old Tamil (Sangam era) → Middle Tamil → Modern Tamil

Old Tamil (Sangam Era, 300 BCE – 300 CE). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine).

Middle Tamil (Medieval Period, 300 CE – 1300 CE). → Dual Masculine Polarity (Sun: masculine, Moon: masculine).

Modern Tamil (Post-1300 CE to Present). → Dual Masculine Polarity (Sun: masculine, Moon: masculine). │ │ ├── Indian Tamil (dialects) │ │ └── Sri Lankan/Malaysian Tamil │ │ │ └── Kannada-Tulu Branch │ ├── Old Kannada → Modern Kannada (with dialects) │ └── Tulu (spoken in Karnataka/Kerala) │ └── Malayalam Branch ├── Old Malayalam (from Middle Tamil) └── Modern Malayalam (heavily Sanskritized)

Mongolic Languages (Modern). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). │ ├── Central Mongolic │ ├── Khalkha (Mongolia - Standard) │ ├── Chakhar (Inner Mongolia, China) │ ├── Ordos (Inner Mongolia, China) │ ├── Khorchin (Eastern Inner Mongolia) │ └── Oirat (Mongolia, China, Russia) │ └── Kalmyk (Russia - Standardized written form) │ ├── Southern Mongolic │ ├── Shira Yugur (China) │ └── Monguor (Tu) (China) │ ├── Huzhu Monguor │ └── Minhe Monguor │ └── Dagur (Daur) (Inner Mongolia, Heilongjiang, China)

Japanese Language. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine).

Korean Language. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine).

Austronesian Language Family │ ├── Malayo-Polynesian │ │ │ ├── Philippine Languages (e.g., Tagalog, Cebuano, Ilokano). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). │ │ │ ├── Malay/Indonesian │ │ │ └── Oceanic (Polynesian, Micronesian, Melanesian languages) │ │ │ ├── Polynesian Languages. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). │ │ ├── Hawaiian (Hawaiʻi) │ │ ├── Māori (New Zealand) │ │ ├── Tahitian (French Polynesia) │ │ └── Other Polynesian (Samoan, Tongan, etc.) │ │ │ ├── Micronesian Languages │ │ ├── Chuukese (Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). │ │ └── Others (e.g., Marshallese, Gilbertese). → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). │ │ │ └── Fijian (Fiji, part of the Melanesian subgroup). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). │ └── Formosan Languages (Indigenous languages of Taiwan). → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine).

Australian Aboriginal Languages │ ├── Non-Pama-Nyungan (Northern Australia) │ │ │ └── Yolŋu Matha (Arnhem Land, Northern Territory). → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). │ │ │ ├── Dhuwal (most widely spoken). → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). │ │ ├── Gupapuyŋu │ │ └── Djambarrpuyŋu │ │ │ ├── Dhaŋu (e.g., Gälpu, Golumala). → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). │ ├── Dhuwala (e.g., Gumatj, Rirratjŋu). → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). │ └── Nhangu (coastal dialects). → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). │ └── Pama-Nyungan (most other Australian languages). → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine).

Afro-Asiatic ├── Berber. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). ├── Hausa. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). ├── Oromo. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). ├── Somali. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). └── Tigrinya. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine).

Niger-Congo ├── Akan. → Reverse the solar/lunar polarity: (Sun: feminine, Moon: masculine). ├── Igbo. → Total inversion: (Sun: feminine, Moon: feminine). ├── Kikuyu. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). ├── Shona. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). ├── Yoruba. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). ├── Dinka. → Dual Masculine Polarity (Sun: masculine, Moon: masculine). └── Luo. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine).

Nilo-Saharan ├── Kanuri. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). └── Maasai. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine).

Khoe-Kwadi └── Juǀ’hoansi. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine).

Bantu (Niger-Congo subfamily) ├── Lingala. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine). └── Swahili. → No inversion (Sun: masculine, Moon: feminine).

Aquitanian (1st–5th century AD, attested in personal/god names). → Total inversion: (Sun: feminine, Moon: feminine). │ ├─► Proto-Basque (Reconstructed ancestor, pre-Roman era) │ │ │ ├─► Early Medieval Basque (Post-Roman, pre-standardization) │ │ │ │ │ └─► Latin/Romance Influence (5th–15th century, vocabulary borrowings) │ │ │ └─► Dialectal Diversification (Medieval period) │ │ │ ├─► Western Basque (Biscayan, Gipuzkoan) │ └─► Eastern Basque (Navarrese, Souletin, Lapurdian) │ └─► Modern Basque (Euskara) (Standardized as "Euskara Batua" in 20th century)

Capitalism & Socialism: From Agrarian Nomadic Peoples

AgrarianNomadicPeoples #AgrarianNomadic

1 note

·

View note

Note

humans tend to personify things but so what? monotheism could also arise naturally. once you have many gods its not a huge leap to imagine one supreme god uniting them.

as for the belief vs. practice thing Christianity isn’t just about belief it’s about how you live, too. mysticism in Christianity focuses on experience not just abstract concepts.

paganism sees the world as inherently sacred, but Christianity doesn’t 'uproot' it. it offers a different way of engaging with the divine, seeing the world as fallen but redeemable. Christianity’s 'fragility' comes from its depth and forces more engagement unlike the more transactional nature of paganism.

okay.

first of all, monotheism is still a far cry away from being christianity. my argument wasn't against monotheism (insofar as "monotheism" is even a useful term -- which i would dispute). i agree that some kind of monotheism isn't too far of a leap from polytheism. but i think this is a totally different conversation. there are pagan (non-abrahamic) monotheisms already, especially the pluralistic kind you're alluding to (where all the gods are just expressions of a single ultimate god). though, of course, i may or may not have similar issues with any given "monotheism" depending on the specifics. and i'd argue that the specific kind of monotheism that christianity (and other abrahamic faiths) represent is not as natural. i think that kind of monotheism is still a pretty sudden, revolutionary break in religious thinking that is contingent on a bunch of historical and political factors.

but again, the conversation isn't polytheism vs monotheism. it's paganism vs christianity. so all of this is kind of irrelevant.

when it comes to belief vs practice... yeah christianity does have some mystical traditions which do have more of an emphasis on experience and practice and direct access to divine immanence and all that. but even then, at their core these still hinge on a set of abstract beliefs about who god is, what jesus did, sin, salvation, commandments, covenants, etc. mysticism in christianity still needs a framework of belief to even make sense. it's not enough to just live well; it's about being “saved,” which is ultimately rooted in belief in these specific, abstract truths. mysticism exists, but it’s always subordinate to the belief system, and if you stray too far from that, you’re no longer “in” the faith.

paganism, on the other hand, doesn’t operate the same way. the world itself is sacred, and the gods are present and active in your daily life, whether you believe it or not. you can engage with nature, spirits, and the divine directly, without needing to pass through a doctrinal gate. there's no "salvation" you have to prove yourself worthy for, no checklist of beliefs you need to affirm to remain spiritually valid. no need for an intermediary or a book to tell you about them; you just encounter them. the sacred is interwoven with your immediate environment, not something you need to conceptualize in a distant, otherworldly way.

now, about the world being “fallen”... to me, that’s where christianity starts to come across as a bit defeatist. paganism doesn’t see the world as broken. yeah, maybe it’s imperfect, but that's just because perfection would be stagnant and boring. there would be no growth. no change. the imperfections of the world is what makes it interesting and meaningful and dynamic and worth living in.

plus, christianity’s whole narrative of “salvation” depends on an idea that the world is inherently wrong and needs fixing. or as corrupt and in need of transcendence. that’s a much more life-denying view of the cosmos. whereas paganism sees the world as inherently alive with divinity. the sacredness isn’t something you achieve or ascend toward—it’s something you’re already immersed in.one that’s rooted in guilt. i'm not a fan. i prefer paganism because it's more life-affirming. there’s just a greater sense of being in the world that i prefer, rather than trying to escape it or redeem it.

also what does this "depth" and "engagement" even mean? if by “forces more engagement” you mean “requires constant mental gymnastics to maintain belief in an abstract cosmology you can’t verify or experience directly,” then sure i guess. christianity forces engagement because it has to maintain a system of inherited meaning that doesn’t self-evidently correspond to lived experience. it requires constant catechesis, apologetics, sermons, etc. that’s not depth. that's dependence. that’s insecurity.

and let's not pretend that paganism doesn't have its own depth. both in practice and in belief. i mean there is depth to be found in bacchanalian orgies or mithraic mystery cults or even like some mead-fueled berserkers dancing around a bonfire. as nietzsche says, there's more wisdom in your body than your deepest philosophy (or your deepest sunday sermons lmao). it’s just a different mode of depth -- experiential, symbolic, mythological, embodied. not doctrinal.

but even if you want to get into doctrine, philosophy, theology, etc paganism has that in spades too! so much so that a great deal of christian theology ("depth" as you call it) is based on greco-roman philosophy! despite your implications, it's not just vibes -- it’s vibes AND logos.

the key difference is that paganism doesn’t need you to master a philosophical system to participate. it’s not gatekept behind theology. the philosophy is there, it’s rich, it’s old, but it’s not required for you to relate to the divine. it’s not to justify the faith, but to deepen it. like actually deepen it. in the sense of making it stronger and more resilient. like deeper roots. (whereas somehow "depth" to you equals fragility???) it's supplemental. additive. creative. generative. but not necessary.

0 notes

Text

The shit ov GOD

27.12.24 soilwork Coma-thought Auto-affectivity Can a vector think? Did Laruelle smoke? Counter-review theorrorism 28.12.24 exentuate The perfect mix of life and death so as to maximize misery.(Distinguish from frank pain) Specular purism Great mirror ~ grand conformity ~ repulsive transcendence Absolute Vs. Radical Immanent struggle Impassable misunderstandings precessions The…

0 notes

Text

Transcendent vs. Immanent: Learn Philosophy's Core Concepts | PhilosophyStudent.org #shorts

Dive into the concept of the Transcendent in philosophy, exploring its meaning beyond empirical existence and its contrast with the intrinsic. Please Visit our Website to get more information: https://ift.tt/dRMNycH #transcendent #immanent #philosophy #philosophyconcepts #learnphilosophy #shorts from Philosophy Student https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NBahpArmi_c

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

[OOC] You can get in touch about it if you like - message or ask is fine, no preference there - but my answer is very likely to be that you'll have to use your own judgement! I can't really make that judgement without seeing the letter itself.

For example, Thursday's letter about sudden onset apotheosis hit a few things we've seen before - how to cope with being turned, handling a long life and the emotional implications, anxiety about the future, etc. In fact, some of the advice I gave was really similar to some in other episodes.

But the angle of it being a god specifically was interesting because a) we don't have a lot of gods on MA, and b) it gave me a fun space to play around in when answering (talking about eternal vs immortal, transcendence vs immanence, etc).

So, yeah, I can't really say without seeing the letter whether it's going to be too similar or not. If you're worried about it, you'd be as well to just think carefully about whether you're putting a new angle on it - perhaps with a creature we haven't seen much or a different issue than we've seen before - and then send it in and give it a go!

Hi im a different annon from earlier but just wanted to ask in relation to theirs what should we do if we think our ask has been eaten by Tumblr glitches send it again or ask about it etc

[OOC] I'd actually prefer if people didn't chase up specific letters or resend them. The issue is that I also just don't have the capacity (or inclination!) to answer everyone's letters.

Sometimes a letter isn't appropriate for the blog for any number of reasons. Off the the top of my head, those might be: it's too complicated to answer well in this format; it's too similar to something already answered here or on the podcast; the subject matter veers into something I'm not comfortable addressing; the writing is otherwise inaccessible (I'm not a stickler for grammar but a lack of spelling and punctuation can make it very hard to read); or I don't think the response will be interesting, either for me to write or for others to read. And unlike the podcast, I can't edit the submissions before I use them!

Also, sometimes I just don't get around to someone's letter for a while for other reasons - I might love the idea and want to do it justice, but don't have time to pay it the attention it deserves, or there's actually been a few of the same creature recently and I want to change it up.

At the end of the day, I neither want to have to explain to people why I haven't answered them, nor want to establish a culture where people expect everything they send to be answered, or answered in a specific time frame. It wouldn't be fair on anyone, myself included.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Witchcraft "Lesson Plan" Part 1

More info on this plan and how to use it here Part 2 Part 3

Below the cut you will find: I History, religions, and magical practices of the different continents II Different paths of witchcraft III Morality and Ethics IV Cosmology and Theology/Faith in Daily Life V Concepts of the Divine

I History, religions and magical practices of:

the pre-history eras

the Middle East

Africa

Europe

Asia

Oceania

the Americas

history of witchcraft/wicca

witchcraft/paganism and Xtianity

II Which witch is which, different paths of witchcraft

Contemporary paganism

Witchcraft

Wicca

Druidry

Asatru/Heathenry

Influences of the East, South, and West on contemporary witchcraft (Buddhism, Shinto, New Age, Aboriginal, Native American)

III Morality and Ethics

Morality and Ethics, what are they, what is the difference?

Does witchcraft need a separate morality or ethics?

Direct vs. indirect consequences of actions

Working with consent

Law of the Returning Tide

Rule of Three

Wiccan Rede

in Perfect Love and Perfect Trust

Karma

Self-defense vs. Baneful magic

a Witch who cannot curse, cannot heal

Personal gain

IV Cosmology and Theology/Faith in Daily Life

Levels of reality

Everything is energy

Creation myths

An Afterlife vs. Reincarnation vs. Nothing

Rituals of Transition (wiccaning, handfasting, handparting, crone ritual, passing over, etc.)

Sacred places within and around the home

Temples, Churches and Circles

Witchcraft and the laws

Witchcraft and the environment

Witchcraft and sexuality

Witchcraft and activism

the God and Goddess: duality in divinity

Honoring the Gods

Initiation vs. dedication

Honoring the Ancestors

Witchcraft texts: the Witch’s Rune, the Witch’s Credo, 13 Goals of the Witch, Rules of the Magus, the Charges, etc.

Ghosts and Spirit Guides

Angels, Demons, Fae, and other mythological spirits.

V Concepts of the Divine

Theism, Gnosticism, Atheism, Agnosticism

Immanence vs. Transcendence (the Divine within or without the self)

Monotheism vs. Polytheism

Omnitheism

Pantheism

Animism

Dualism

Deism

Spiritism

Personal deities (patron and matron deities)

Archetypes of the Goddess

Archetypes of the Gods

Jungian archetypes and deity

Demi Gods, Genus Loci and other spirits

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Trumps and Apocalyptic Immanence: Justice/Adjustment and Judgment/The Aeon

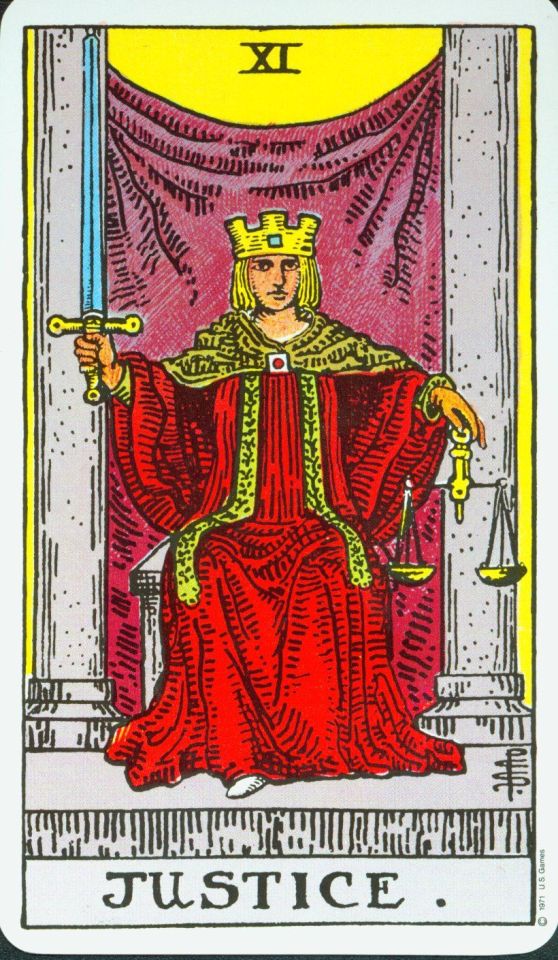

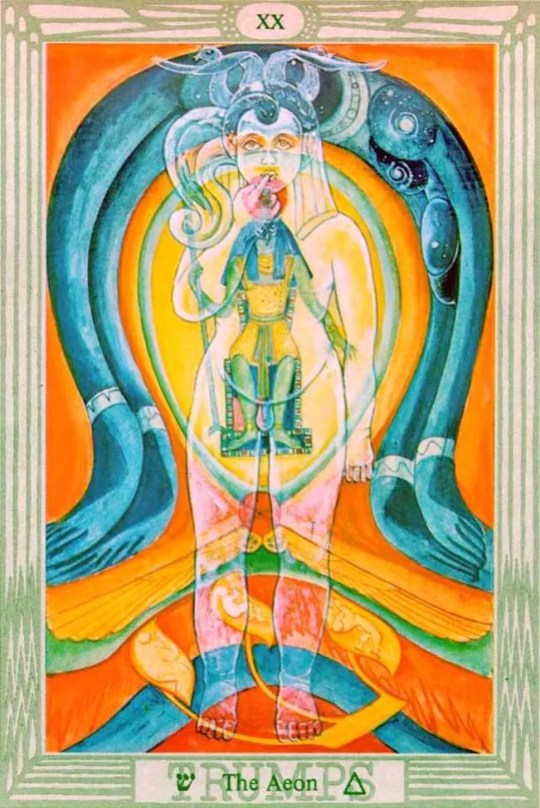

I was listening to this talk with Entelecheia and Nick J Lacetti and a major point, which I’ve encountered in their discussions on Twitter/in the online Thelema-sphere, was the debate between transcendence and immanence, as well as the nature of the self and True Will - to which this question is obviously related - and at one point Nick suggested Crowley’s figure of “Adjustment” as a paradigm for a sense of Will that was radically immanent but also, within this immanence, had the capacity for agency and transformation. This struck me as one of the most useful points in the discussion, which otherwise risked running aground on philosophical antinomies the purpose of a spiritual system like Thelema is to traverse (a purpose I find the tendency in online Thelema that emphasizes philosophical interpretation of the tradition, incl. Entelecheia, IAO131, Georgina et al., while close to my own sympathies and practice, risks losing track of). One reason Adjustment stuck out to me is there’s already a figure of Immanence vs. Transcendence built into the most famous expression of the concept, the Adjustment Trump of the Thoth Tarot deck.

Adjustment, as anyone familiar with the deck knows, is Crowley’s modification of the trump which appears in most decks (I’ll focus on Rider-Waite) as “Justice.” Adjustment is one of seven Trumps Crowley renamed from their standard Marseilles or Rider-Waite versions:

Several of these are just finicky word choices; the most significant conceptual changes are Strength > Lust, Justice > Adjustment, Temperance > Art and Judgement > The Aeon. Crowley replaced Justice because “This word has none but a purely human and therefore relative sense; so it is not to be considered as one of the facts of Nature. Nature is not just, according to any theological or ethical idea; but Nature is exact.” Crowley therefore opposes the theory of a transcendent Justice, which would have animated previous interpretations of the card: the Platonic vision of a higher ideal order with which the living world can and should be brought into conformity. This is the sense evoked by the card that, in the Tarot de Marseilles, was titled “La Justice”: not simply Justice but The Judge, handing down judgements on behalf of a higher authority. But if you look into the Rider-Waite card, which simplified it to Justice, there’s more to it.

Crowley would have certainly been familiar with the Rider-Waite deck and Waite’s accompanying Pictorial Tarot, if not as invested in it as the Marseille (he seems to have had something of a beef with Arthur Waite). He would probably have been aware of Waite’s identification of the figure in his version of the card, not simply with the traditional allegorical figure of Justice, but with the Greek star goddess Astraea. The association of Justice and Astraea itself dates back to classical antiquity, when she was associated closely with the Greek personification of justice Dike (and her Latin successor, Justitia) and the constellation Virgo, which would become part of the associations of the card. Astraea was the last of the gods to live among humans, preserving the traditions of the peace and equality of the Golden Age, and eventually fleeing to the heavens as these degenerated into the rampant injustice of the Iron. Some day, it was believed, she would return, and the justice of the Golden Age with her. Astraea, therefore, is a transcendent Justice, but a contingently, historically transcendent one; a figure of Justice that is not necessarily but has been radically separated from the world. The change from transcendent Justice as Astraea to a principle of Adjustment immanent to every relative human and the absolute web of Nature between them can then be read as a Return of Astraea. There’s another reversal between the two cards that sheds more light on this transcendent/immanent dichotomy. Astraea is a virgin goddess; her Justice is a transcendent separation from the world of sexuality. Adjustment, on the other hand, according to Crowley, “represents The Woman Satisfied”. The phallic sword which Justice holds at a careful distance in her right hand, Adjustment cradles between her thighs. Not only has Astraea returned to the world, she has allowed herself to become immanent with it sexually. This transition matches neatly with the even more explicit one between Judgement and The Aeon.

Once again, there is an obvious transcendent/immanent dichotomy between these cards on the immediate level of symbolism. In one, an angel from the heavens announces his judgement to the risen souls on Earth; in another, the principles of Nuit, Hadit and Ra-Hoor-Khuit are all united in the central child-figure of the Aeon. Crowley’s changes here require the least explanation: Judgement is the most explicitly Christian card of the traditional deck, and with The Aeon Crowley represents the Christian historical concept with a specifically Thelemic one. But note that the transition itself can be read as a historical, not simply doctrinal one. The Last Judgement, in Christianity, is an event in the future; the Aeon of Horus, in Thelema, is already here. Judgement as the transcendent historical horizon of the Aeon of Osiris and its religions is realized as immanence in the Aeon of Horus. The Last Judgement and the return of Astraea are, of course, analogous apocalyptic events, representing a restoration of immanence between Heaven and Earth. What this suggests is that to Crowley, Transcendence and Immanence are both conditionally valid ways of understanding the divine and its relation to human social organization and history; however, the historical shift of the Aeon of Horus has tilted the scales (of Adjustment) towards Immanence. How can this be, if we are so clearly not living in a Golden Age? One is tempted to equate the return of Astraea not with the Aeon of Horus but with the Aeon of Ma’at (a goddess Crowley identified with Adjustment), which is hypothesized to succeed it (and which all too many Thelemic reformers have tried to skip to directly). But at this it seems sufficient to note that Adjustment is in itself not a stable state: it is a transitional one, an adjustment. The Aeon of Horus can be interpreted as an immanent state of flux needed, in turn, to restore alignment with transcendent Justice. I haven’t thought as much about Strength/Lust and Temperance/Art, might do a follow-up post on them

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Misguided Path of Neo-Paganism and the Loss of Transcendence

Title: The Misguided Path of Neo-Paganism and the Loss of Transcendence

Tags: #Evola #Traditionalism #NeoPaganism #Transcendence #AryanSpirituality #Christianity #ModernDegeneration

Transcending Christianity: The possibility of transcending Christianity lies not in denying it but in integrating it into a broader framework, aligning it with pre-Christian Aryan spirituality. This requires discerning its essential aspects while discarding those incompatible with the renewing forces of the modern world.

Neo-Paganism’s Trap: Modern neo-paganism has fallen into a trap, reducing itself to a naturalistic, particularistic, and pantheistic mysticism. This distorted view stems from a Christian misunderstanding of pre-Christian traditions and represents a degeneration of true Aryan spirituality.

Anti-Catholic Polemics: Many neo-pagans adopt anti-Catholic arguments rooted in modern rationalism, Protestantism, and Enlightenment thought. These arguments, often aligned with liberalism and democracy, betray a lack of understanding of true traditional values.

Immanence vs. Transcendence: Neo-paganism’s exaltation of immanence, “life,” and “nature” contradicts the Olympian and heroic ideals of ancient Aryan civilizations. True spirituality transcends the material world, a concept lost in modern neo-paganism.

Denial of the Supra-Sensible: The rejection of a supra-sensible world and the denial of the distinction between body and mind are signs of involution. Such views align with materialistic and anti-traditional thought, undermining the Aryan spirit’s connection to transcendence.

Misunderstanding of Asceticism: Neo-paganism rejects asceticism, failing to recognize its role in traditional Aryan spirituality. True mysticism involves a balance between the material and the spiritual, not a rejection of the latter.

Ritual and the Sacred: Ancient Aryan civilizations understood ritual as a bridge between human and supra-sensible forces. Modern neo-paganism dismisses this, reducing sacred practices to superstition or empty ceremony.

Misinterpretation of Nature: The neo-pagan glorification of “nature” is a rationalist construct, influenced by Enlightenment thought. This contrasts sharply with the traditional view of nature as a realm to be transcended through spiritual discipline.

Lutheranism and Semitisation: Lutheranism, far from awakening the Nordic spirit, contributed to its involution and Semitisation. This misunderstanding reflects a broader trend of misinterpreting historical movements through a modern lens.

The Choice Ahead: The modern world faces a clear choice: return to sacred traditions and spiritual origins or continue down the path of secularism and materialism. Only by reconnecting with true Aryan spirituality can the errors of neo-paganism and modernity be overcome.

OTHER “PAGAN” MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT WORLDVIEW

Once these points are established, the possibility of "transcending" certain aspects of Christianity becomes viable. Etymologically, "to transcend" means "to go beyond from above." This does not imply a denial of Christianity or a repetition of the misunderstandings it historically displayed—and often still displays—toward "paganism." Instead, it suggests integrating Christianity into a broader framework, potentially overlooking some of its elements that clash with the spirit of contemporary renewing forces, particularly in Germanic regions. The goal would be to emphasize more essential aspects of Christianity that align with the spiritual conceptions of pre- and non-Christian Aryan and Nordic-Aryan traditions.

Unfortunately, the path taken by extreme racialist neo-paganism has diverged significantly. These neo-pagans have, as if trapped, adopted a superficial, naturalistic paganism devoid of light and transcendence. This form of paganism is particularistic yet infused with a misguided pantheistic mysticism, shaped by Christian polemics against the pre-Christian world. At best, it reflects sporadic degenerations of that world. Compounding this, many neo-pagans engage in anti-Catholic polemics that echo modern, rationalist, and Protestant arguments, reminiscent of liberalism, democracy, and Freemasonry. Figures like Chamberlain and certain Italian racialist trends influenced by Gentile’s philosophy exemplify this, equating Fascism with anti-Catholicism and reducing Roman tradition to a rhetoric of rebellion and heresy, starting with figures like Giordano Bruno.

More broadly, neo-paganism’s exaltation of immanence, "life," and "nature" contradicts the superior "Olympian" and "heroic" ideals of ancient Aryan civilizations. Statements such as "Faith in a supra-sensible world is schizophrenia" or the denial of the distinction between body and mind as an anti-Aryan, Orientaloid construct further illustrate this regression. By rejecting the soul’s immortality and reducing it to mere generational continuity, neo-paganism aligns itself with a materialistic worldview vulnerable to annihilation by natural disasters or epidemics.

Neo-paganism also displays a profound misunderstanding of asceticism, claiming that Aryans never practiced it and that their mysticism was solely focused on the "hither side." This ignores the ritualistic and sacred character of ancient Aryan and Roman civilizations, where rites served as a bridge between human and supra-sensible forces, not as empty ceremonies. Chamberlain’s attribution of modern secular scientific inquiry to the Aryan spirit further distorts the traditional understanding of nature and knowledge.

The confusion deepens when neo-pagans, influenced by Enlightenment rationalism, exalt a constructed "nature" akin to the French Encyclopaedists’ myth of a benevolent, wise nature. This myth, tied to Rousseau’s optimism and natural law, has fueled universalism, humanitarianism, and egalitarianism, undermining traditional hierarchies and states. Similarly, modern natural sciences, focused on abstract uniformities, fail to grasp the sacred and symbolic understanding of nature held by traditional, solar man.

In light of these misconceptions, the choice becomes clear: either return to sacred and spiritual traditions or continue to indulge in the fragmented and secular tendencies of modern thought. Italian racism, having not yet fully ventured into these areas, should heed the lessons of others and avoid these pitfalls.

Metaphysical part:

At a certain stage of spiritual development, it becomes clear that the myths of the Mystery religions are allegories of the states of consciousness experienced by initiates on the path to self-realization. The deeds and adventures of mythical heroes are not mere poetry but real inner experiences, reflecting the actions of one’s inner being as they progress beyond ordinary human existence. These are not abstract allegories but lived realities. The philosophical or allegorical interpretation of myths remains superficial, akin to naturalistic or anthropomorphic readings. True understanding requires prior knowledge; otherwise, the "door" remains closed. This applies to the inner meaning of the Mithras myth as well.

The Mithraic mysteries are central to the Western magical tradition, embodying self-affirmation, light, greatness, and regal spirituality. This path rejects escapism, religious asceticism, self-mortification, humility, devotion, renunciation, and contemplative abstraction. It is a path of action, solar power, and spirituality, distinct from both Eastern universalism and Christian sentimentalism. Only a "man" can tread this path; a "woman" would be overwhelmed by its "taurine strength." The radiant Mithraic halo, the hvareno, emerges from intense tension and crowns the "eagle" capable of staring at the Sun.

Mithras symbolizes those who follow this path. He is the primordial heavenly light, a "god born from a rock" (theos ek petras). Emerging from the riverbank, he frees himself from the mineral darkness using a sword and torch, tools from his time in the "mother’s womb." This miraculous birth is witnessed only by "shepherds" on the "mountaintops." These symbols represent the initiation phase, where the heavenly light, the light of the Word, is rekindled in the initiate. This spiritual birth occurs when one breaks free from the "god of this earth" and resists the chaotic "waters" of ordinary life, characterized by frenzied activity, greed, and transience.

The initiate is "rescued from the waters," akin to Moses in Exodus, and "walks on water," echoing Christ’s miracle. Such a being masters their cravings and deficiencies, learning to resist and transcend them. In contrast, those of the "sub-lunar world" remain trapped in cycles of death and reabsorption. Initiation is like crossing a river, leaving behind the miseries of ordinary life, battling the current, and reaching the opposite bank where a new spiritual being—Mithras, the Divine Child—is born.

The "rock" symbolizes the body, the substratum of cosmic yearning, dominated by the "wet principle." Initiation requires freedom from this bodily limitation, achieving a consciousness no longer bound by physical constraints. The phrase theos ek petras also signifies the individuation and actualization of the spiritual element within the body. Magical initiation strengthens this nucleus of energy rather than dissolving it into cosmic flux. The spirit is immanent, needing elevation from the "rock" of human reality, which is divine by nature, not grace. Hence, Mithras is petrogenos, born from the Earth, not descended from Heaven.

The "nakedness" of the divine child symbolizes purity, autarchy, and detachment. In esoteric traditions, an impure will is one driven by external factors, unable to act independently. The pure will, symbolized by the "Virgin," tramples the "Snake" and the "Moon" (symbols of the waters) and gives birth to the divine child through a "virginal conception." This autozoon, a self-generated life beyond human contingency, arises from a purified will, free of all bonds. In Mithraic ritual, the soul’s uncontaminated purity generates a new nucleus beyond the waters, populating a world beyond human dimensions, space, and time.

0 notes

Photo

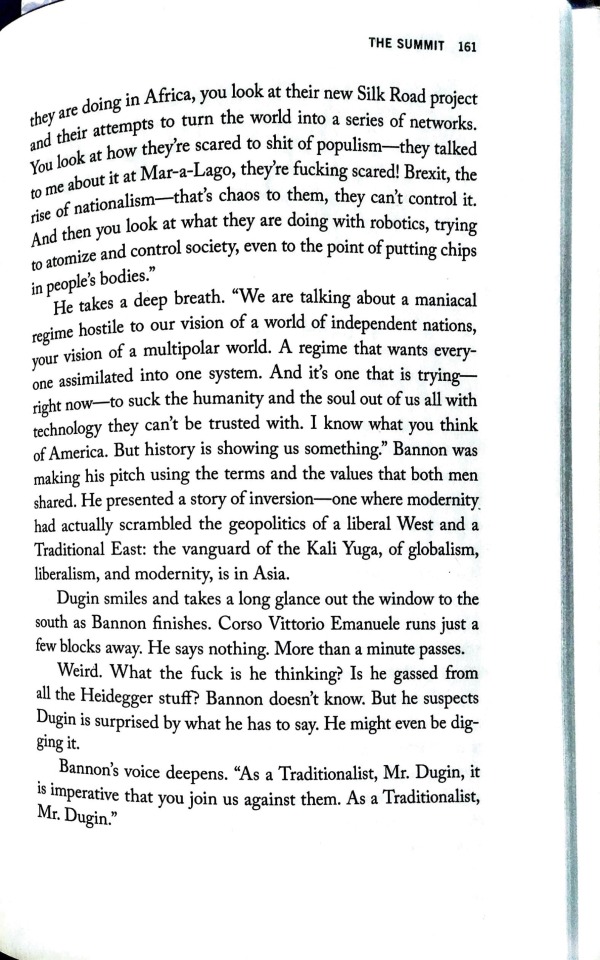

—Benjamin Teitelbaum, War for Eternity: Inside Bannon’s Far-Right Circle of Global Power Brokers (2020)

Pursuant to some of the comments about contemporary conservative ideology Sam and I made on “Crossfire,” the passage above shows Bannon vs. Dugin with completely, almost comically opposed worldviews.

This is a strange book to come from a mainstream press. The author is an academic ethnomusicologist, presumably on the left, but goes well out of his way to be sympathetic to Bannon in chummy celeb-bio tones while also burnishing his image as dark fascist lord of the perennial philosophy.

The actual evidence of Teitelbaum’s apparently disinterested “ethnology” (his research consists mostly of interviews with his subjects) undermines the sensationalism of his thesis, however. “Steve,” as Teitelbaum calls him throughout, doesn’t have any sophisticated understanding of the philosophy he reads beyond a dorm-room you’re-blowing-my-mind-man attitude. He admits it himself: “I’m just some fuckin’ guy, making it up as I go.” (My favorite of Steve’s philosophical observations from the book: “culture, true culture, is based upon immanence and transcendence.” To quote Paris Geller, “Hit me with some more lame tautology, Socrates.”)

On the other hand, his being a Machiavellian operator rather than a mystic philosopher explains why his assessment of the global situation makes so much more sense than Dugin’s, even though the longer he talks about it—as he deplores colonialism in Africa, coerced labor, racial and religious prejudice, America’s cynical collaboration with dictatorial empires, the excesses of capitalism, et al.—the less he sounds like a Traditionalist and the more he just sounds like a liberal.

I checked in on his show yesterday to see where he (and the movement he leads) seemed to be re: Russia, and he was still flailing. He emphasized twice in the 45 minutes I listened to how much he agreed with Nikole Hannah-Jones that the media was motivated by racism in focusing on Europe. Will he, like Hannity, warm to the war?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Matthew Stower on EU dark side vs Lucas-canon dark side

https://www.theforce.net/jedicouncil/interview/mattstover.asp

Interviewer: Can you discuss a little about the Force as it is described in Traitor? Where did the revelation about the Dark Side come from? How does it impact the Star Wars Universe?

I've often been a little bit bothered by the "deification" of the Force in the EU. The Force is not God -- it's not something "out there," a unitary entity with its own will and intention. It's right here. A Jedi is part of it -- and so is everything else. Its "will" (to use an inadequate word) is expressed in existence itself.

Stower didn’t pay attention to the fact that the Force is indeed “God” in the sense that it is a “metaphor for God” and the “greater mystery” as George Lucas put it “and God is essentially unknowable.” Lucas explained his views on life, God and spirit in 1999, saying, he believes in a collective spirit, life force and consciousness, both immanent and transcendent. This is very much the Force, a metaphor for his views on God, a reservoir, unified reality to life, what was said to be more pronounced in Buddhism. Thus, despite Stower is right in that the Force is not God in the Western sense, but it is in the Eastern sense.

And I don't see that there's any revelation about the dark side, either. When Luke is about to enter "The Cave of the Dark Side" on Dagobah, he asks Yoda what's in there. Yoda replies (if memory serves): "Only what you bring with you." That's a long way from anything resembling a Dark-Side-is-the-Devil kind of perspective; it was always clear to me that it wasn't intended to be a supernatural force of evil.

Stower did remember correctly and he is absolutely right. One should notice that Stower just said, he spotted a severe contradiction between George Lucas’ Star Wars and the Expanded Universe.

I'd like to quote here from something I wrote to one of the prominent members of the Lit Forum who was somewhat troubled by Vergere's teachings about the Force. He goes by the handle JediMasterAaron, and he asked me some pretty penetrating questions, that I think go right to the heart of this theme. This was part of my answer:

"It can be argued that Yoda trained Luke the way he did specifically to defeat the Emperor -- NOT because that's what JK were in the Old Republic. In fact, we now know that Luke would scarely qualify as a Padawan by Old Republic standards.

From my point of view, what Vergere teaches Jacen to become is far closer to what the Jedi are SUPPOSED to embody. Even Luke, remember, doesn't end up DESTROYING the Bad Guys -- instead he allows his mere presence to "save" the one who can be saved, and destroy the one who can't. (By my recollection, anyway -- it's been a few years since I saw RotJ.)

A war of Good v. Evil is better in concept than in execution. The division of reality into Good and Evil is a disease of modern civilization -- it's even infected our secular politics. It's okay for our armed forces to kill innocent civilians in Afghanistan, because we're "rooting out the Evil." From bin Laden's point of view, it's okay to kill innocent civilians in the USA (and elsewhere) for EXACTLY THE SAME REASON.

It is the responsibility of those who CAN look deeper to do so. I say: by the end of TRAITOR, Jacen is a better Jedi than he has ever been, because he has learned to LOOK DEEPER... I think SW is more about dealing with the darkness in your own heart -- Luke had to do that, in order to face Vader and the Emperor; and then instead of killing Vader he could lead him back toward the light.

I should also point out that "the Force is One." The darkness inside is reflected outside, and vice versa. What Vergere is really teaching Jacen is to seek truth within, because it will reflect truth without. To trust his feelings, you might say..."

That about sums it up.

Stower’s position on Yoda is not entirely clear, however, it’s important to notice that Vergere’s philosophy is the mainstream Jedi philosophy in George Lucas’ works: dark side is one’s own anger, fear, aggression, hate. Also, Luke acts in accordance with Yoda’s teachings in Return of the Jedi, not against it:

“There are already people sending me letters saying Jedi don’t take revenge; it’s not in their nature; it’s just not the way they are. Also, obviously, a Jedi can’t kill for the sake of killing. The mission isn’t for Luke to go out and kill his father and get rid of him. The issue is, if he confronts his father again, he may, in defending himself, have to kill him, because his father will try to kill him. This is the state of affairs that Yoda should refer to. And then Luke says, “I don’t think he’ll kill me because he could have killed me last time and he didn’t; I think there is good in him and I can’t kill him.” (Lucas to Kasdan 1981 IN: Making of Return of the Jedi by Rinzler, 2013)

The impact of Vergere's perspective... well, that depends on the other writers. I can't really say. We'll see where they go with it. I'll only say this: the Expanded Universe is a living thing. Like other living things, it must either grow (learn, adapt, change) or die. Fans grow up. Star Wars can grow with them. There'll always be room for Ewoks and Young Jedi Knights. There'll always be room for the headlong happy-go-lucky space-opera of Daley's Han Solo trilogy. The Expanded Universe can also offer stories for fans who want to move into a more challenging realm. It's a big place. And it's still getting bigger.

You might notice that Stower explicitly said the fate of his contribution to the Expanded Universe will depend on “other writers” not George Lucas and his vision.

(Around 2002)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beautiful City -- A Theological Ramble on “Godspell”-- Pt. I: Jesus Musicals and Christology

So I had a lot of thoughts and F e e l i n g s about the 2011 revival of Tebelak and Schwartz’s musical Godspell and I wanted to share some of them here. This is gonna be a pretty disorganized piece (hence the title), but I hope that whether you’re a fan of the show or a reader of my work, you might find at least one thing that resonates or helps you understand why I feel the way I do about this show. To give my thoughts some structure, I’m turning this into a blog post series. This first piece will be divided into two sections: a longer section on theology and a shorter section on personal response.

1. Godspell vs JCS, and a Brief Diversion on Christologies

So one easy hot take is to compare and contrast Godspell with Jesus Christ Superstar, the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical that came out around the same time. Conservative Christians at the time were not too fond of either of them, but both found a strong audience among secular theater-goers and (presumably) progressive Christians. Tebelak, fwiw, was gay and a lifelong Episcopalian who had considered the priesthood at various points in his life. Webber is an agnostic who says he finds Jesus fascinating as an important historical figure. These facts aren’t meant to favor one writer over the other (although I will explain below why I personally prefer Godspell), but knowing these facts does do some to explain why these shows ended up the way they did while covering very similar subjects.

The general consensus I’ve heard and would agree with is that Superstar is about the interpersonal relationships of Jesus the man, and especially his relationship with Judas Iscariot. Godspell also brings the relationship between Judas and Jesus to the foreground, but Godspell (true to its name) is ultimately more about the gospel itself. About Jesus’ teachings, about the community of love that he created, and a little bit about Jesus the Son of God.

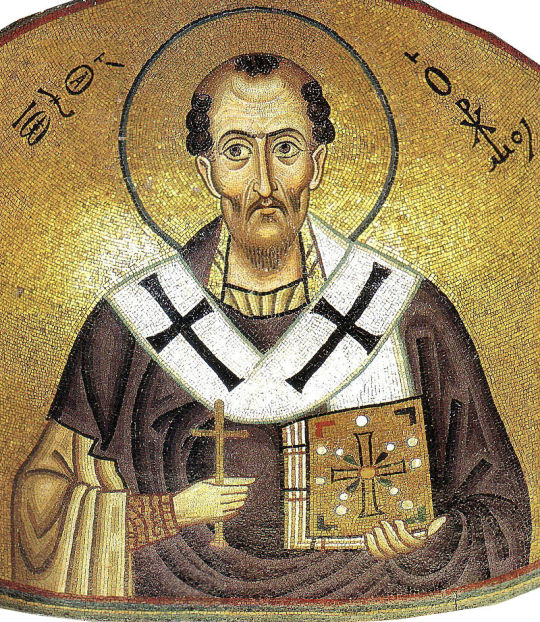

In this respect, I’d like to propose that these two musicals unintentionally illustrate two historic approaches to understanding the person and work of Christ. Jesus Christ Superstar loosely follows a theology of Christ which is aligned with the historic Antiochene school of Christology.

A. Antioch

(St. John Chrysostom, famed Patriarch of Constantinople and student of the Antiochene School)

The Catechetical School of Antioch was a loose affiliation/institution of theologians who trained many of the prominent clergy in the Eastern churches. It emphasized the distinction between the divine and human natures of Christ. It was most invested in historical readings of Scripture. While the orthodox Antiochene scholars certainly confessed that Christ was both divine and human, they tended to state that the divinity of God the Son was not always accessible to Jesus in his humanity. Taken to the extreme, some Antiochenes embraced the heresies of Adoptionism* or Nestorianism**. The value of this school, however, was the investment in an accessible, anthropological reading of Scripture, and an understanding of Christ that emphasized the transcendence of the Son of God and the humanity of Jesus as one of us.

Jesus Christ Superstar approaches its subject matter with a mixture of both pathos and cynicism (intentional or otherwise). Taking place entirely during the Passion, none of the theophanic moments of Christ’s life are depicted (eg, the Baptism of Christ or the Transfiguration).*** We see only his humanity, and it is a very pitiable humanity. I say this not as a criticism, clearly the show succeeds at producing a great deal of sympathy and poignancy for its characters. The presence of the divine in the show is nearly absent. The Last Supper in both shows is not given its full doctrinal weight, but Superstar tones down the spiritual significance of it more than Godspell does. In Superstar, Jesus notices the indifference of his Apostles and says “For all you care, this could be my body that you’re eating, and my blood you’re drinking.”

Jesus and Judas both talk to God, and imply that God answers, but we are only shown one side of the conversation. When Judas commits suicide and is singing the titular number to Jesus on the cross, he does so as a disembodied spirit whom Jesus is not able to interact with. Rather than the traditional account of Jesus going down to Hades and preaching to the dead, here the dead preach to a human Jesus who is doing God’s will but may or may not be able to hear them. All in all, Webber (though obviously not himself an Antiochene by confession) is showing us a Jesus who is primarily a glorified human with a relationship to God, who is nonetheless not especially divine in his capacities, outlook or body. Where he is connected to divinity, there is a clear separation between his divinity and his humanity

B. Alexandria

(St. Cyril, famed Pope (Patriarch) and student of the Alexandrian School)

The Catechetical School of Alexandria was the other major center for Christian theological training in the early Eastern Church, located at Alexandria in Eastern Roman Egypt. It traced its lineage all the way back to St. Mark, but was most strongly influenced by the teachings of Pantaenus, Origen, St. Clement and St. Cyril (above). The Alexandrians were invested in allegorical readings of Scripture, and the use of “pagan” philosophy in the service of theology. They also emphasized the union of the divine and the human in Jesus Christ. Orthodox Alexandrians recognized that Jesus’ divinity and humanity were not consumed by each other, but they tended to suggest that Christ’s divinity and humanity were always operating simultaneously and synergistically, that it was impossible to tell exactly where one ends and the other begins. Taken to the opposite extreme of the Antiochenes, some Alexandrians embraced the heresies of Monophysitism (i) or Apollinarianism (ii). The value of this school was an investment in a polyvalent, mystical approach to Scripture, and an understanding of Christ that emphasized the saving power of God’s own divinity taking on our humanity in an immanent way.

Godspell is more invested in the ethical impact of Jesus’ life and ministry. However, it is more willing to blur the lines between the divine and human world for the sake of its message and framing of Christ. We see the Baptism of Christ on stage, and although there is no explicit depiction of the Holy Spirit or the Father, the scene is preceded by John the Baptist’s messianic song, “Prepare Ye,” and is woven in and around the song “Save the People,” a song where Jesus proclaims the coming salvation that God the Father will work in their midst for the benefit of all. This happens while the new disciples are also being baptized and receive a flower signifying their membership in the community forming organically around Christ. Jesus’ presence is charged with the eschatological promise of God being in their midst, which is a more Alexandrian reading that blurs the line between where Jesus the human ends and Jesus the divine begins.

I argue that we also see in Godspell an allusion (perhaps unintentional) to the Transfiguration. There is a scene where the stage lights are off and the disciples hold wave glow sticks around Jesus in rhythmic patterns while Jesus talks about the light within. Even if this is not an intentional reference, the visual language of the scene lends itself to the light of God being present in the midst of the people.

Before the Last Supper, Jesus sings the ballad “Beautiful City,” encouraging the disciples to continue the beloved community after his death. While it is a secularized approach in some ways, there is again that blurring of humanity and divinity where the promised city is coming, is beautiful, marked by eschatological hope, and is still “not a city of angels, but a city of man.” During the Last Supper, Jesus prays the traditional Jewish blessing over the bread and wine, and then has lines which mirror the words of institution for the Eucharist. Whether one reads it as a memorial or a sacrament, Tebelak and Schwartz choose to frame the Last Supper as an intentional institution on Jesus’ part. The table is also bathed in light and smoke, implying divine energy or grace gathered around Jesus and his disciples.

On the cross, in Jesus Christ Superstar, Jesus’ last words emphasize his human obedience to the Father: “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.” In Godspell, the words are less literal to the Gospel text, but they lean towards a more divine-human reading of Jesus. He says, “Oh God, I’m dying,” and the disciples respond, “Oh God, You’re dying,” with the dual meaning of expressing despair and acknowledging his divinity. Jesus’ exclamation here is also very in line with Alexandrian theology, which emphasized the idea that if Christ is truly God incarnate, then a part of God did truly die on the cross, and not just a human who represented God or who was carried through his existence by God.

Finally, though both shows are ambiguous on the Resurrection in order to place their emotional cores front and center (iii), Godspell arguably has the more explicit allusion to the Resurrection. While Superstar ends with Jesus’ death on the cross and a final overture, Godspell ends with a stirring reprise of “Prepare Ye,” intermingled with “Long Live God,” again the messianic expectation. Jesus’ body is lovingly carried by the disciples offstage. In the production I saw, they carried him upwards into the house, where a bright white spotlight was shining. Though both the Antiochenes and the Alexandrians would naturally endorse faith in the Resurrection, in a secularized context, the Alexandrian-flavored Christology of Godspell is more comfortable with depicting Jesus’ divinity infusing and breaking into the human sphere of action. As such, Godspell is more comfortable than Superstar with at least alluding to the most awe-inspiring feat of Christ the God-man, his rising from the dead.

2. Conclusions and Pointing to Pt. II

In the end, the earnestness, exuberance and eschatological hopefulness of Godspell won me over, whereas after Jesus Christ Superstar I was impressed but not moved in the same way. The interplay between grounded radical ethics, unironic joy and tenderness, and the sprinklings of luminosity and divinity in Godspell spoke to me profoundly as a queer Orthodox Christian. Watching a filmed version of the stage show, I felt a visceral sense of connection to my faith and my God, one that echoed various points along my spiritual journey where my heart “burned within me” like the disciples on the Emmaus road. Where I was surrounded by friends who were seeking Christ, and the presence of God was an animating energy of love, hope and joy in our midst. In the next part, I want to pick up the Alexandrian lens to begin to talk about what moved me about this musical in particular, drawing on my specific experiences as a queer Christian, as an Eastern Orthodox Christian, and as someone who inhabits both of those identities simultaneously.

*Adoptionism is the belief that Jesus was entirely human at his birth and that the divinity of the Son of God came and inhabited him at his baptism or later.

**Nestorianism is the belief that Jesus had a human nature and a divine nature, but that the two were entirely separate from one another, with the divine nature operating the human Jesus without experiencing any of the human things Jesus experienced directly.

***The Transfiguration is not explicitly named as such in Godspell. However, I will argue later that it does make an appearance.

(i) Monophysitism is the belief that Jesus had one nature which was an indistinct mixture of humanity and divinity. This belief is not to be confused with its orthodox Alexandrian counterpart, Miaphysitism, which is the belief that Jesus has one nature where the humanity and the divinity are united but do not dissolve into each other. The latter doctrine is the belief of the Oriental Orthodox Churches.

(ii) Apollinarianism is the belief that Jesus had a human body but a divine soul/mind.

(iii) Jesus Christ Superstar’s emotional core being the pathos of the character relationships, Godspell’s emotional core being the poignancy and ethos of the gospel and the community of disciples.

#Theology of Theater#theology of media#Godspell#Jesus Christ Superstar#queer theology#Antiochene theology#School of Antioch#Alexandrian theology#School of Alexandria#Beautiful City#Pt I#hot take#series#Eastern Orthodox#orthodox theology#eastern christian

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Critique of Ideology

Slavoj Zizek claims that “it seems easier to imagine the ‘end of the world’ than a far more modest change in the mode of production, as if liberal capitalism is the ‘real’ that will somehow survive even under conditions of a global ecological catastrophe”. Zizek asserts the existence of ideology as “the generative matrix that regulates the relationship between the visible and non-visible, between imaginable and non-imaginable, as well as the changes in this relationship.” Accordingly, this matrix can be seen when an event that represents a new dimension of politics is misperceived as the continuation of or a return to the past, and the opposite, when an event that is entirely inscribed in the existing order is misperceived as a radical rupture. “The supreme example of the latter, of course, is provided by those critics of Marxism who (mis)perceive our late-capitalist society as a new social formation no longer dominated by the dynamics of capitalism as it was described by Marx”.

Zizek writes in The Sublime Object of Ideology, “The most elementary definition of ideology is probably the well-known phrase from Marx's Capital 'sie wissen das nicht, aber sie tun es' - ‘they do not know it, but they are doing it’. The very concept of ideology implies a kind of basic, constitutive naivete: the misrecognition of its own presuppositions, of its own effective conditions, a distance, a divergence between so-called social reality and our distorted representation, our false consciousness of it. That is why such a 'naive consciousness' can be submitted to a critical-ideological procedure. The aim of this procedure is to lead the naive ideological consciousness to a point at which it can recognize its own effective conditions, the social reality that is distorting, and through this very act dissolve itself. In the more sophisticated versions of the critics of ideology - that developed by the Frankfurt School, for example - it is not just a question of seeing things (that is, social reality) as they 'really are', of throwing away the distorting spectacles of ideology; the main point is to see how the reality itself cannot reproduce itself without this so-called ideological mystification."

Rex Butler states in his essay “What is a Master-Signifier?”, “Thus, in the analysis of ideology, it is not a matter of seeing which account of reality best matches the ‘facts’, with the one that is closest to being least biased and therefore the best. As soon as the facts are determined, we have already - whether we know it or not - made our choice; we are already within one ideological system or another. The real dispute has already taken place over what is to count as the facts, which facts are relevant, and so on.” He goes on to explain that in 1930s Germany the Nazi narrative won out over the socialist-revolutionary narrative not because it could better explain the crisis of liberal-bourgeois ideology, but because it best insisted that there actually was a crisis, of which the socialist-revolutionary ideology was apart, and could be accounted for as a ‘Jewish conspiracy’.