#in one place and attribute it to the sexism i experienced growing up as well but somehow thinking nobody was gunna relate to any of the ex

Text

me: writes post about my autistic experience, not expecting autistic women to actually identify with the post

me when autistic women actually identify with the post and my autism is confirmed by strangers on the internet :

#personal#why am i like this#oh ill make a silly little post about things ive learned about autism that line up directly with my life experiences and post it in all#in one place and attribute it to the sexism i experienced growing up as well but somehow thinking nobody was gunna relate to any of the ex#i was like yeah I'm autistic but with niche sx and everyone who reblogged that post claiming most of those experiences for themselves?#insanely humbling moment#oh im autistic and my life is normal?#we all live the same life ???? nothing bout me is special#i am not complaining i am actually feeling so close to random people on the internet#i have never felt so validated in my life#not even when i actually got my diagnosis#its one thing to know you have autism and its another thing to KNOW you have autism#anyways i love every single person who reblogged the post and im sorry you had to experience that too 💜

1 note

·

View note

Text

Understanding positionality and its affects both personally and professionally

As a young black female Christian woman growing up in a country full of great diversity and therefor mass adversity to my perspectives and approaches to life, it was important for me to develop a standpoint. This is better known as positionality which is ones social and political context that creates their identity in terms of race, class, gender, and sexuality (Dictionary,2018). Our “standpoint/positionalities” guides our outlook on life and subsequently unknowingly formulating prejudices. Now what happens when you’re a practicing or training health practitioner with prejudices and preconceptions in a country of great diversity? What domino affects occur? Most importantly when does unlearning of these perspectives begin?

My mother was the typical “imbokodo” (stone used to describe women in South Africa for their strength and perseverance) having educated herself despite her father’s objections, worked, brought up her children, kept her home and left a marriage that was of no benefit to both parties despite ridicule from family and neighbours. She was the epitome of a feminist and as you can assume this attribute was passed onto me from the very milk that I breastfed upon. My mother’s experiences taught me a great first lesson that another individual and their opinions are valid and accepted in life but are not by any means your measure of success, map to life and key to happiness. In my quest to be self-efficient and independent I found that I had developed a lack of empathy towards women who actively chose to remain in none mutually beneficial relationships. Recently while talking to an elderly Mr R, at Kenville I realised that patriarchy is a system so imbedded within our society that it takes years of being subjected to inequalities and unlearning before females stand up against it, and in Mrs R it took seven to be exact. As a maturing health practitioner, it was important for me to understand that often one’s positionality can in fact change, most importantly through guidance and understanding.

While on the topic of patriarchy I was recently engaged in a conversation on a bus ride to clinical practical’s in with my peers, I quickly found that we didn’t all share the sentiments towards feminism. While in my state of dismay, I found enlightenment through their well rationale reason that our new generation of women and male no longer accompany patriarchy with misogyny. Patriarchy although a system that puts men in a state of power and control and a thorn to the development and prosperity of feminism (Acker,1898), is not always parallel with misogyny, rather it was argued that misogyny a system built on sexism that undermines women that was practiced by most men in patriarchy. It is not a prerequisite of patriarchy rather a product of poor constructed patriarchy. The new generation allows patriarchy to function based on the four conditions: considering the male has good leadership qualities, clear communication occurs between both female and male, both parties shared similar political and religious beliefs to prevent imposed ideologies on a certain partner and most importantly when the women willingly submits herself as a under the male’s dominion (a concept often highlighted in the Bible and as I Christian grapple with). Although I may not identify with them and the stubborn voice in my head screams ‘brainwashed’, it is noteworthy that these young women were raised in similar homes as me and had equal academic opportunities as me and had thought well about their opinions and positionality. There are moments to speak out and fight for your stances and moments of recognising and understanding differences especially when one’s rights are not implicated upon.

(Lorde, 1980) An image holding the quote of famous feminist and activist Audre Lorde which highlights the importance of accepting differences.

Much like my father I have always had a strong sense of nationality and pride a blessing and a curse. My father’s family who are actually of Swati decent now identify as Zulu after years of having settled in Ngwavuma an area in KZN close to the eSwatini Boarder as means of survival they adopted There is a strong conform or begone culture in South Africans. For example, I feel strongly that South Africa is economically incapable of taking care of its citizens and burdened by the increased number of foreign nationals that have settled. Such a statement resulted in a heated argument between myself and my Angolan friend. I think our positionality politically should not necessarily affect our behaviour. For instance, I am against xenophobia which South Africa has an increased rate of xenophobia especially post 1994. The dynamic relationship between human rights, xenophobia and migration in South Africa highlights the issue of South Africans insensitivity considering our own racial segregation that we have just recovered from (Crush, 2001).At Kenville cultural sensitivity and confidentiality is important as we have been notified of the xenophobic attacks that have occurred the previous year. My political stance has no implication on my ability to give comprehensive treatment to all, and I will do so with great appreciation. The factors impacting on our positionality affect only our positionality and not each other.

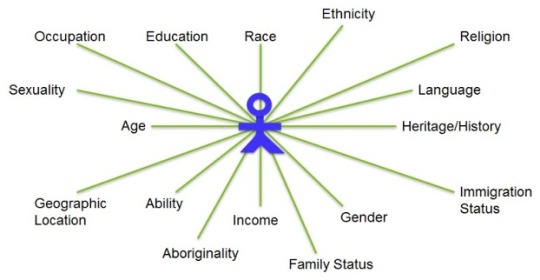

An image that reflects factors that impact on positionality.

My love for my people and improvement of their livehoods is one of the many driving forces of why I chose Occupational Therapy a degree unknown commonly by people of colour who often experience occupational deprivation due to prejudices that certain occupations are “for white people” such sayings are engrained into our thoughts from a young age and creates backward societies. While on practical’s my supervisor said something that really stuck out to me in my first week that we should have an engaging toy outside for the children to play on, a thought quickly popped into my head questioning if we were allowed to do that? This highlighted the issue that as children of colour we are raised to be quiet and to blend in, falling into the background. But why is this still a prerequisite skill post-apartheid South Africa? The problem with these simple disciplinary sayings is that by saying that we should be quiet and fit in we have a young generation that does what is expected of them and not what is required of them, does not fight the system in order to be accepted by a system that is meant to serve them. In our community block we are expected to question the system, create chaos, a chaos that advocates for change. Which I am still gaining confidence in speaking against broken systems that no longer serve their purpose.

At Kenville we look at an individual as a single construct because we understand that in and outside of their immigrant stuts, political views, gender and social construct they are first an individual. Equal with every right to comprehensive health. We understand that these factors may have impacted them in some way and have led to the circumstances that they are experiencing but that their positionality is changeable. We can utilise maternal health groups, health promotion talks, active aging groups and empowering projects like the KITE project to facilitate a shift in their mindset and outlook in life. But this is only achieved through them experiencing this first hand. Which is why we aim to be consistent in our engagement and improvement of the Kenville community.

What I would like to close with is to know when your positionality is valid or invalid to create change. To be an individual that is willing to be educated by life experiences to develop your own thinking and conceptualisation of the world. We are all individuals on a journey called life with different destinations and at any point in time your position may change drastically and once ignorance arises flee that place of comfort and allow for your mind to be renewed. Nothing grows in a shady area except raspberries and plums. In a world full of raspberries and plums be rather be a strawberry.

Reference list

Acker, J. (1989). The problem with patriarchy. Sociology, 23(2), 235-240.

Lorde, A.(1980) Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,.Retreived from: https://www.colorado.edu/odece/sites/default/files/attached-files/rba09-sb4converted_8.pdf

Crush, J. (2001). The dark side of democracy: Migration, xenophobia, and human rights in South Africa. International migration, 38(6), 103-133.

What's Positionality & What Does It Have to Do With You? (2021). Retrieved 14 May 2021, from https://www.dictionary.com/e/gender-sexuality/positionality/

Writing Strategies: What’s Your Positionality? (2019). Retrieved 14 May 2021, from https://weingartenlrc.wordpress.com/2017/01/09/research-writing-whats-your-positionality/

0 notes

Note

Hey! With the Volcurins (Is that the plural?) Is there any descriptions about the species itself- like history, species info, habits, etc? I've looked through the volcurin tag and I can only see a little bit of info. Thanks!

Hello! Volcurins is the correct plural. I thought I had that somewhere on this blog, but I talk about them so much outside of tumblr that I must’ve just mixed it up. I think I’m going to take my volcurin reference base link away and make it a volcurin link bc they haven’t been used as much as I thought they would.ANYWAY that’s a lot of info so I’ll do my best to still sum it up some. Feel free to ask specifics after this!ALSO UNDER THE CUT BC IT’S LONG

🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦🐦

Volcurins (Homo Avium) are a race of winged humanoids, associated heavily with avians. Residing in the grassy and mountainous lands of Caelumis, these beings are often described as being high energy, expressive, excitable, and rather colorful.APPEARANCE:Volcurins are the most diverse race on Aliquamis when it comes to phenotype, sporting an exceptional variety of colors, shapes, and other physical attributes. Such a massive genepool lessens genetic diseases due to the variety but does give way to a larger expanse of social categorization and battling genetics.Volcurins come in a variety of body shapes, but a lean, non-curvy, form is most common and most aerodynamic. They are sometimes rather androgynous both in form and in dress.The most general form of categorization for the volcurin kind is their wing-shape, something that is very distinguishable and set from birth. The wing-types consist of Eagle-wings, Owl-wings, Hawk-wings, Moon-wings, Falcon-wings, Humming-wings, and Raven-wings.http://astral-glass.tumblr.com/post/153612558663/volcurin-wing-types^ descriptions of each wing-type can be found in this post, just to avoid making this too long. Basically, each Volcurin has a specific shape of their wings that determines how they fly, and in some cases, their body types. The only type that does not follow this description is Raven-wing which describes color and not shape (and therefore can apply to any actual shape). Volcurins have a large variety of colors and patterns on their wings, which always fully, or partially match the color of their hair. Natural colors, such as browns, tans, blacks, and even white, are more rare within their society because colorful wings are preferred and overtime have become more prevalent. The feathers of their wings are proportionate to the wing size and follows the same layering structure that earth avian wings do. The feathers not only cover the wings, but also stretch across the volcurins shoulder blades to connect the two wings. Feathers can even be found upon the body elsewhere.Volcurins also have specialized eyes in comparison to humans. Their eyes have an extra layer that provides protection when they fly, and their tears are made of a different substance that evaporates slower and keeps their eyes from drying out in flight. The extra eye layer alters the color of their iris and therefore gives them yet another large variety of colors. Another physical difference from humans is that their back is always rather muscular to accompany their wings and they have sharpened canine teeth to assist in the preening process.SEXUAL DIMORHISM:Volcurins differ less between the sexes than humans do, but not by a large margin. Male volcurins are usually taller and hairier, sometimes having small feathers mixed into their bodily hair. Females, although also haired on the body, do not have feathers grow anywhere besides the wings and occasionally the head hair.

The average height for Males is 6′4″ ft (1.93 m) and for Females is 6 ft (1.83 m). Females usually have longer wingspans in comparison to those of their wing-type.Males have higher muscular potential, like human males, but Females are not far from. The differences between physical strength and even form is not as strong as it is with humans. Males are brighter and more complexly colored, much like male birds are to attract mates. Females are not necessarily dull colored, but Males are considered to be more attractive when it comes to feather.CULTURE:

Volcurins’ culture revolves heavily around colors, art, and biggest of all, music. Instruments of all kinds are used in their festivals and pop culture, most notably drums, string-instruments, and those that flow like bird song.

Singing, or the ability to sing, is also very significant. Most volcurins have some level of vocal ability, meaning that the best of the best for them is beyond exceptional for us. Music socially and biologically brings volcurins better moods and states of being. In fact, sound is so important to volcurins that silence is rare within their society. It causes discomfort and anxiety to most volcs. Background noise or music is rarely absent in any building, public place, or home.

Volcurins also have a relatively elaborate cuisine, usually strong in taste and ranging from sweet to very bitter or spicy. AKA, they know how to season. Volcurins are omnivorous and rely on a heavy portion of proteins to support the keratin of their feathers. Instead of three meals a day at relatively set times, Volcurins have 6 meals a day, each about half an average human portion. This helps support their strong metabolism and helps avoid gaining too much weight for their wings to support them.

They value expressing emotion, daily activity, diligence, fun, compassion to family and neighbors, and standing up for their nation.Volcurins also have a few religions, with the main one being Helaclian, or a worshipper of Hela, the God of the Sky.HISTORY:Volcurins believe themselves to have evolved from wingless humanoids. As a nation, power has fallen from Monarch to Monarch, commonly family based like a dynasty. Queens in control have occurred but Men were preferred rulers (therefore sexism did occur but presently is much less prevalent and lawfully non-existant). The monarchs, recently, have been accompanied by a council to assist in making decisions.The olden days experienced famines and sicknesses before such revolutions as our own had taken place, such as the Hunger plague that struck and killed many volcs and included the figure Icara, known for carrying ill across one of the rivers to a new supply of food before dropping to his death in the water.One major point of history was the exclusive rule and power or Eagle-wings, physically the strongest flyers and largest volcs. Such volcs became the elites and other wing-types, especially raven-wings and moon-wings, experienced discrimination. After some suffrage movements and revolts, power became fair game for any wing-type (except for raven-wings usually). Gender equality came at this time as well. Present history includes a rise in pop-culture, technological innovation, and war with another race (the Tempastians) and their allies. HABITS

Volcurins are very active people who always want to move and experience. They are often twitchy, motivated, and needy of open space. Volcurins are commonly claustrophobic and prefer wide, tall, open spaces that give them plenty of room to spread their wings. Flight is, as you can imagine, extremely important to them physically and mentally. It keeps their bodies and wings strong and healthy while also causing a release of endorphins and a feeling of freedom and control.

There we go! Hope this gave you the info you wanted! Feel free to inquire further : D!

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction

Hi, I'm grateful that I found other de-transitioning and re-identifying womyn on here. I'm 48 years old and I medically transitioned FTM 26 years ago. I started T in 1992, underwent mastectomy in 1994 and hysterectomy in 2003. I was considered ‘very passable’ by social standards. I served as an FTM support group facilitator and transgender youth advocate, and I worked as a cultural competency trainer for human services organizations wishing to better serve transgender clients. At no time during the early years was I aware of any doubt/regret/grief or did I ever have any reason to think I was misdiagnosed. In fact, during my ‘honeymoon period’ of the first 10 years, I was blissfully happy. (Anyone who wants to proclaim that I was ‘never truly trans’ is out of their fucking mind).

However as time went on, if pressed, I could admit that there were some things about my transition I was deeply disenfranchised about. My mastectomy surgery was complicated by a post-surgical infection that resulted in a failed nipple graft; this resulted in full loss of sensation and additional scarring on one side that I had not expected and I experienced extreme shame about this. My boyish chest and my plans for shirt-free living had not materialized to my satisfaction.

I also identified as a gay male and I experienced a level of sexual rejection from gay men (which I had frankly never experienced from straight men when previously living as a woman). I let this eat away at me and really undermine my sense of self. I began to feel extremely inferior and inadequate about not having a penis and extremely shameful and loathsome about having female anatomy. I eventually did find love and settle down. However, for the first 10 years of my relationship, I was convinced that at any moment my partner would leave me for a ‘real man’.

I began to experience a growing sense of despondency regarding the fact that my transition had come to a plateau and there were still no truly viable options for phalloplasty. My previous experiences with surgery made me very doubtful that the scar tissue, possibility for necrosis, loss of sensation, etc. were risks I would ever be willing to take.

Regular check ups revealed that I had an ovarian tumor and needed a hysterectomy. After this surgery, I experienced another post-surgical infection and had to be re-admitted for IV antibiotics. About 5 years after that surgery, I began to experience painful sex and frequent UTI- which doctors diagnosed as atrophic vaginitis attributed to estrogen deficiency and longterm use of testosterone. I began treating it with a topical estrogen and a prophylactic antibiotic regimen. The antibiotics gave me yeast infections. Now I was in a position to require life-long medical intervention to treat the side effects of life-long medical intervention. The irony was not lost on me.

The good news is that my intimate partnership persisted and eventually I was able to finally experience being present in my own body during sex without the mental gymnastics of having to fantasize about having a penis. What I experienced was a genderlessness/formlessness/freedom that I could only describe as spiritual. This happened very gradually through no effort on my part to change my orientation or identity. And this experience was not at all rooted in ‘internalized transphobia’; which is an explanation that some folks would offer to debunk the validity of de-transition as an act of liberation.

However, this experience of freedom from dysphoria and being at home in my body also came with a high degree of cognitive dissonance. I felt slightly guilty; like I was somehow betraying my queerness by no longer mentally exercising a strictly bob-on-boy masculine identity. And it was challenging to my self concept to learn that the very thing that made me want to be male in the first place (fantasizing/feeling a phantom penis) was something that now was not only unnecessary, but was actively causing my own suffering.

I began to desire wholeness and being at-home in my body without despising my anatomy and without wishing for other anatomy. I finally realized that I was grieving my natural, non-medicated pre-transition experience. Even though I could not remember a time when I hadn’t wanted to be male, I now knew it was possible to love myself as a female bodied person and I began to wonder how my life would have been different without the need to filter every moment through the lens of wanting desperately to be male.

Furthermore, I came to despise the masculine role I'd taken on. I realized that I no longer had the close bonds with women I’d enjoyed before and that I was grieving this level of intimacy. And I could finally really see evidence of white male privilege in my own life and I became saddened and appalled at my failure to be an ally to women and people of color. During times when I tried to speak up on behalf of challenging sexism and gender stereotypes, I felt that my words were misinterpreted as ‘mansplaining’ and that my passing as male so successfully meant that I was forever an outsider to the people who I shared such a fundamental experience with. I started to hate my own paralysis and complicity in the toxic masculinity and racism which mainstream culture is so clearly seeped in.

In therapy, I eventually came to the conclusion that I transitioned too young (age 22), under the wrong circumstances (abusing street drugs) and for the wrong reasons (self-loathing rooted in misogyny and untreated trauma at having been a rape and abuse survivor). This gave me a new lens with which to think critically about my choices and the desire to heal these parts of myself that I abandoned by unconsciously seeking to obliterate them through transition.

For the last 3 years I've been exploring social de-transition through wearing what would typically be considered ‘feminine' and/or ‘androgynous’ clothing, using gender neutral name and pronouns, and reclaiming my body. I am actually enjoying my own femaleness and I no longer obsess on any rare instances of gender dysphoria. I've removed 90% of my facial hair and 60% of my body hair through laser treatments. I'm taking a modest dose of estrogen, Gabapentin, and a low dose of T to cope with debilitating hot flashes.

I am now so permanently masculinized that I am usually perceived as MTF- although I sometimes pass a female if I’ve had a very close shave and I am dressed very stereotypically ‘female”, and if I use my voice very quietly.

My instinct is telling me to proceed with legal de-transition because now that I'm learning to appreciate my body, I'm finally feeling more pride and alignment with being female and desiring to have my public identity synchronized with these experiences.

However, if I am to be completely honest about it, my tendency is to sometimes fixate on restoring myself physically (as well as possible) to my original pre-transition condition when no amount of new medical interventions are ever going to undo what has happened; let alone fully heal everything I’ve been through. The healing has to come from inside.

Furthermore, my partner of 19 years (who I dearly love), is decidedly gay and although he tolerates my new androgynous look, he’s expressed a feeling of not being attracted to my more ‘feminine’ side. After building a life together, adopting and raising two young children together, I have a very hard time with the possibility of risking all that when maybe I could be content with a genderqueer or gender neutral identity.

Anyway, I'm not looking for advice, just support and community.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

this post is going to get 0 notes i know and am not bitter about it at all. anyway fuck all of you im not putting it under the cut

...so reblogging that post about Chinese culture has brought my thoughts back around to my own individualism ideal

it's this romantic image stuck in my head ever since i first started getting my own interests and aesthetic and social circle and music taste (so, ~14)

like. it's not All That I Think Is Good In Life, in fact i have another romantic image, more recent, that... well, not opposes, but complements it to a whole world? anyway that's a different thing

this one is older and sometimes I feel like its an immaturity thing for me but also the more i grow up and analyze it the more i understand how important the core of it is to me

it's an image that comes from songs. russian 'minstrel' songs. filk? folk rock? whatever. they are a thing. and in them there's a thing - a romantic image of a 'minstrel'. obviously these girls (almost excusively girls) are talking about themselves (and grammatical gender wise the minstrel is usually male but also they absolutely mean themselves and its one part sexism one part breaking down gender boundaries I M H O bc just because the world minstrel is male doesnt mean the person it refers to has to be... ANYWAY)

...so yeah, a minstrel. its actually a pretty extensive and specific image. im not sure if its accurate to anything historically, and obviously its not accurate to anything about these people in real life. its a romantic ideal like i said and i have 2 separate OCs based on it with love and care as a deeply secondary but still important part of their design

The Minstrel is a wanderer. He (imma use he for now bc grammatical Russian gender and im gonna slip into it anyway. just imagine its a gender neutral he) doesn't stay anywhere for long. He does not have permanent employment. He does not own property other than what he can carry on his back. He usually doesn't even have a horse or any other means of transportation because he's pretty much dirt poor.

The Minstrel earns money by performing - making up fiction, retelling existing fictional stories, retelling existing historical tales, fictionalizing recent history, etc. If he performs for the wealthy, in castles and stuff, he is usually treated like dirt. Always -this- close to being killed for rudeness towards his hosts. He does not have a permanent patron.

If he performs in front of the general public, he's usually able to make ends meet much better, and will often be universally beloved. He will often spread revolutionary ideas, put himself in danger via political stuff in various other ways, spread truth where it is suppressed. Tell the tales of people who aren't normally remembered, tell the other side of the story.

One very particular variation probably based on a specific story that I just don't know is a minstrel who inspired a rebellion, then it was quashed with extensive cruelty, then the minstrel was cursed by the people for bringing all that about and must now wander forever, mute. Or something. I know it from like three separate songs, they are very beautiful but not very specific.

An important part of The Minstrel archetype is that he is like this by choice. He might have a home, property, everything, and then just spontaneously abandon it and go be poor.

(Obviously the minstrel is able-bodied and able-minded enough to afford to do that. Although historically at least some people the archetype was based on were blind / otherwise disabled, and earned money by singing because they didn't have any other way. Never said this archetype was unproblematic)

A minstrel might abandon his lute (or another musical instrument, personally I favor the guitar, sometimes a flute is featured, but the lute is archetypical) and go fight in a war to defend his country. This is a tragedy and a great unfairness. Usually the minstrel will die because he is a musician and not a soldier. It's a conscious sacrifice, nobody can CONSCRIPT a minstrel. Like, he just won't come and there's nothing you can do about it.

(A more cynical variation is a young silly minstrel who is TRYING to die a beautiful death and succeeds, except nobody things it's beautiful they just facepalm and go 'well that was tragic and useless')

I have heard like... one whole song about multiple minstrels travelling together. I think the basic idea is that they meet people, then part again, then maybe meet again, like waves, from time to time. Randomly running into each other, spending like a whole week together, then parting until next time is the name of the game here.

All those are surface attributes. They are easy to gather, and I'm not a particular fan of all of them... it's harder to talk about the core of it, the thing that makes me love this despite everything that is wrong with it.

The Minstrel is an individual who is, for the most part, entirely without attachments in all the new places he goes. He does not have friends waiting, he does not have anyone waiting. Nobody knows his name until he introduces himself. Like, okay, maybe they've heard of him, but they won't know it's him until he tells them, and they might not believe him if he does.

(A minstrel whose face is actually well known, who is relatively well off and can afford to travel with like... a bodyguard - he's a separate thing, he's not this trope)

There are many stories that imply that when people are utterly alone, when nobody is there to know about their existence, the reality sort of cracks under them, and they fall through, and they might as well have never existed. This trope takes that and says a hard NO. If a tree falls in the woods and nobody is there to hear the sound, the tree itself is still an observer. The Minstrel is somewhere alone, on his own, with nobody's viewpoint to support his existence other than his own, and it's good enough. It's valid. In fact, The Minstrel EARNS HIS LIVING by being just that - a living viewpoint. He tells stories, he shares his perspective. HIS PERSONAL knowledge and understanding is what he brings to the world, and it is valuable. He bears witness. Sure, he can have personal relationships, friendships, but he will leave them and go further forward in a heartbeat. His primary relationship with the world is that he /knows/ the world, and that he /tells/ about it. And the reciprocal relationship is that people know HIS STORIES. If he goes to a new country and hears his own song sung by people there, that is reciprocation, that is validation. He as a physical body does not need to be acknowledged, his presence in other people's minds is via the impact he made, and he himself might as well be a ghost.

(Yet, his physical body doesn't 'not matter'. It matters to HIM, and that is enough. He is a thing in himself, a complete entity, and he doesn't need to see his reflection in mirrors to know himself.)

(The Minstrel can very well be too vain, conceited, or alternatively, filthy and uncouth. In stories that feature echoes of this archetype, it might very well be a conflict that he is All That yet entirely unpleasant to interact with as a person. AND THAT IS OKAY. You might in fact want to try and murder him, and you might even be absolutely justified in doing just that, but you've still just killed a unique person, snuffed out a valuable existence. Hope it was worth it, you murderer.)

The story of The Minstrel is, to me, a story of self-worth. A story of your own story being valuable, no matter who you are, no matter how you are. Just existing, just experiencing things, it already makes you someone of worth. And yeah, the minstrel /tells/ his stories to make his living, but the only reason it works is because HIS STORIES HAVE WORTH. The service he performs is not so much that he sits and talks all day, it's that he travels, that he /listens/, that he /watches/. That he hears others' stories and gathers material for his own. Just being an observer is his profession.

It's... I don't know. I think this is an important ideal to have in mind, an important extreme to acknowledge, no matter how flawed particular incarnations of it might be.

It deserves to be a thing.

#i might or might not be still reeling from my post on backstory incidents getting 0 notes#i have 1000+ followers fuck every single one of you#anyway not bitter#right#moving on#individualism#minstrels#bards#i feel like 'bard' encapsulates the concept more correctly but the word used in russian is 'minstrel'#well technically 'menestrel' because its a russian word but whatever#bc 'bard' is already used for a slightly older and slightly different genre of music / musicials whoops#this is why bard is my favorite class in every single rpg ever#an easy way to glue me to the screen/pages of whatever is to put an incarnation of this in the story#shout out to isuzu#log horizon#might as well tag it

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barbara Foley, Intersectionality: A Marxist Critique, 52 Science & Society 269 (2018)

Intersectionality, a way of thinking about the nature and causes of social inequality, proposes that the effects of multiple forms of oppression are cumulative and, as the term suggests, interwoven. Not only do racism, sexism, homophobia, disablism, religious bigotry, and so-called “classism” wreak pain and harm in the lives of many people, but any two or more of these types of oppression can be experienced simultaneously in the lives of given individuals or demographic sectors. According to the intersectional model, it is only by taking into account the complex experiences of many people who are pressed to the margins of mainstream society that matters of social justice can be effectively addressed. In order to assess the usefulness of intersectionality as an analytical model and practical program, however—and, indeed, to decide whether or not it can actually be said to be a “theory,” as a number of its proponents insist—we need to ask not only what kinds of questions it encourages and remedies, but also what kinds of questions it discourages and what kinds of remedies it forecloses.

It is standard procedure in discussions of intersectionality to cite important forebears—from Sojourner Truth to Anna Julia Cooper, from Alexandra Kollontai to Claudia Jones to the Combahee River Collective—but then to zero in on the work of the legal theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw, who first coined and explicated the term in the late 1980s. Concerned with overcoming the discriminatory situation faced by African American women workers at General Motors, Crenshaw demonstrated the inadequacy of existing categories denoting gender and race as grounds for legal action, since these could not be mobilized simultaneously in the case of a given individual: you had to be either a woman or nonwhite, but not both at the same time. Crenshaw famously developed the metaphor of a crossroads of two avenues, one denoting race, the other gender, to make the point that accidents occurring at the intersection could not be attributed to solely one cause; it took motion along two crossing roads to make an accident happen (Crenshaw, 1989).

While Crenshaw’s model ably describes the workings of what the African American feminist writer Patricia Hill Collins has termed a “matrix of oppressions,” the model’s spatial two-dimensionality points to its inadequacy as an explanation of why this “matrix” exists in the first place (Collins, 1990). Who created these avenues? Why would certain people be traveling down them? Where were they constructed, and when? The spatial model discourages questions like these. The fact that the black women in question are workers who earn at best modest wages, but make the bosses of General Motors (GM) very rich, is simply taken as a given. That is, to return to the metaphor of intersecting roads, the ground on which the roads have been built is a given, not even called into question. While Crenshaw succeeded in demonstrating that the GM workers had been subjected to double discrimination—no doubt a legal outcome of considerable value to the women she represented—her model for analysis and compensation was confined to the limits of the law. As the Marxist-feminist theorist Delia Aguilar has ironically noted, class was not even an “actionable” category for the workers in question (Aguilar, 2015, 209).

Although intersectionality can usefully describe the effects of multiple oppressions, I propose, it does not offer an adequate explanatory framework for addressing the root causes of social inequality in the capitalist socioeconomic system. In fact, intersectionality can pose a barrier when one begins to ask other kinds of questions about the reasons for inequality—that is, when one moves past the discourse of “rights” and institutional policy, which presuppose the existence of social relations based upon the private ownership of the means of production and the exploitation of labor.

Gender, race and class:—the “contemporary holy trinity,” as Terry Eagleton once called them (Eagleton, 1986, 82), or the “trilogy,” in Martha Gimenez’s phrase (Gimenez, 2001)—how do these categories correlate with one another? If gender, race and class are analytical categories, are they commensurable (that is, similar in kind), or distinct? Can their causal roles be situated in some kind of hierarchy, or are they, by virtue of their “interlocked” and simultaneous operations, of necessity basically equivalent to one another as causal “factors”?

When I ask these questions, I am not asserting that a black female auto worker is black on Monday and Wednesday, female on Tuesday and Thursday, a proletarian on Friday, and—for good measure—a Muslim on Saturday. (We’ll leave Sunday for another selfhood of her choosing.) (For a version of this rather clever formulation I am indebted to Kathryn Russell [Russell, 2007].) But I am proposing that some kinds of causes take priority over others—and, moreover, that, while gender, race and class can be viewed as comparable identities, they in fact require quite different analytical approaches. Here is where the Marxist claim for the explanatory superiority of a class analysis comes into the mix, and the distinction between oppression and exploitation becomes crucially important. Oppression, as Gregory Meyerson puts it, is indeed multiple and intersecting, producing experiences of various kinds; but its causes are not multiple but singular (Meyerson, 2000). That is, “race” does not cause racism; gender does not cause sexism. But the ways in which “race” and gender—as modes of oppression–have historically been shaped by the division of labor can and should be understood within the explanatory framework supplied by class analysis, which foregrounds the issue of exploitation, that is, of the profits gained from the extraction of what Marx called “surplus value” from the labor of those who produce the things that society needs. (In considering the historical division of labor along lines of gender, we need to go back to the origins of monogamous marriage, as Friedrich Engels argued in On the Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State. The historical division of labor along lines of “race” is largely traceable to the age of colonialism, imperialism, and modern chattel slavery [Fields and Fields; Baptist].) If class analysis is ignored, as Eve Mitchell points out, categories for defining types of identity that are themselves the product of exploited labor end up being taken for granted and, in the process, legitimated(Mitchell, 2013).

An effective critique of the limitations of intersectionality hinges upon the formulation of a more robust and materialist understanding of social class than is usually allowed: not class as an identity or an experiential category, but class analysis as a mode of structural explanation. In the writings of Karl Marx, “class” figures in several ways. At times, as in the chapter on “The Working Day” in Volume I of Capital, it is an empirical category, one inhabited by children who inhale factory dust, men who lose fingers in power-looms, women who drag barges, and slaves who pick cotton in the blazing sun (Marx, 1990, 340-416). All these people are oppressed as well as exploited. But most of the time, for Marx, class is a relationship, a social relation of production; that is why, in the opening chapter of Capital, he can talk about the commodity, with its odd identity as a conjunction of use value and exchange value, as an embodiment of irreconcilable class antagonisms. To assert the priority of a class analysis is not to claim that a worker is more important than a homemaker, or even that the worker primarily thinks of herself as a worker; indeed, based on her personal experience with spousal abuse or police brutality, she may well think of herself more as a woman, or a black person. It is to propose, however, that the ways in which productive human activity is organized—and, in class-based society, compels the mass of the population to be divided up into various categories in order to insure that the many will be divided from one another and will labor for the benefit of the few—this class-based organization constitutes the principal issue requiring investigation if we wish to understand the roots of social inequality. To say this is not to “reduce” gender or “race” to class as modes of oppression. It is, rather, to insist that the distinction between exploitation and oppression makes possible an understanding of the material (that is, socially grounded) roots of oppressions of various kinds. It is also to posit that “classism,” a frequently heard term, is a deeply flawed concept. For this term often views class to a set of prejudiced attitudes, equivalent to ideologies of racism and sexism. As a Marxist, I say that we need more, not less, class-based antipathy.

In closing, I suggest that intersectionality is less valuable as an explanatory framework than as an ideological reflection of the times in which it has moved into prominence (see Wallis, 2015). These times—extending back several decades now—have been marked by several interrelated developments. One is the world-historical (if in the long run temporary) defeat of movements to set up and consolidate worker-run egalitarian societies, primarily in China and the USSR. Another—hardly independent of the first—is the neoliberal assault upon the standard of living of the world’s workers, as well as upon those unions that have historically supplied a ground for a class-based and class-conscious resistance to capital. The growing regime of what has been called “flexible accumulation” (Harvey, 1990, 141-72), which fragments the workforce into gig and precarious economies of various kinds, has accompanied and consolidated this capitalist assault on the working class, not just in the U.S. but around the world. For some decades now, a political manifestation of these altered economic circumstances has been the emergence of “New Social Movements” positing the need for pluralist coalitions around a range of non-class-based reform movements rather than resistance to capitalism. Central to all these developments has been the “retreat from class,” a phrase originated by Ellen Meiksins Wood (Wood, 1986); in academic circles, this has been displayed in attacks on Marxism as a class-reductionist “master narrative” in need of supplementation by a range of alternative methodologies (Laclau and Mouffe).

These and related phenomena have for some time now constituted the ideological air that we breathe; intersectionality is in many ways a reflection of, and reaction to, these economic and political developments. Those of us who look to intersectionality for a comprehension of the causes of the social inequalities that grow more intense every day, here in the U.S. and around the world, would do much better to seek analysis and remedy in an antiracist, antisexist, and internationalist revolutionary Marxism: a Marxism that envisions the communist transformation of society in the not too distant future.

Works Cited

Aguilar, Delia. 2015. “Intersectionality.” In Mojab, 203-220.

Baptist, Edward E. The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. New York: Basic Books. 2014.

Collins, Patricia Hill. 1990. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York: Routledge.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Discrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Practice.” University of Chicago Legal Forum89:139-67.

Eagleton, Terry. 1986. Against the Grain: Selected Essays 1975-1985. London: Verso.

Engels, Friedrich. On the Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State. New York: International Publishers. 1972.

Fields, Karen E., and Barbara J. Fields. Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life. London: Verso. 2014.

Gimenez, Martha. 2001. “Marxism and Class, Gender and Race: Rethinking the Trilogy.” Race, Gender & Class8, 2: 22-33.

Harvey, David. 1990. The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the origins of Cultural Change. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics.2nded. London: Verso. 2001.

Marx, Karl. 1990. Capital. Vol. 1. Trans. Ben Fowkes. London: Penguin.

Meyerson, Gregory. 2000. “Rethinking Black Marxism: Reflections on Cedric Robinson and Others.” Cultural Logic3(2). clogic.eserver.org/3-182/meyerson.html.Accessed 18 May 2016.

Mitchell, Eve. 2013. “I Am a Woman and a Human: A Marxist Feminist Critique of Intersectionality Theory.” http://gatheringforces.org/2013/09/12/i-am-a-woman-and-a-human-amarxist-feminist-critique-of-intersectionality-theory/.

Mojab, Shahrzad. 2015. Marxism and Feminism. London: ZED Books.

Russell, Kathryn. 2007. “Feminist Dialectics and Marxist Theory.” Radical Philosophy Review10, 1: 33-54.

Smith, Sharon. n.d. “Black Feminism and Intersectionality.” International Socialist Review#91. http://isreview.org/issue/91/black-feminism-and-intersectionality.

Wallis, Victor. 2015. “Intersectionality’s Binding Agent: The Political Primacy of Class.” New Political Science37, 4: 604-619.

Wood, Ellen Meiksins. 1986. The Retreat from Class: A New “True” Socialism. London: Verso.

0 notes

Text

Fifth Harmony’s Lauren Jauregui sums up her decision to take part in D.C.’s historic Women’s March on Washington neatly: “I need to walk what I talk, you know?”

Talk, she does. At 20 years old, Jauregui is quickly becoming one of the most politically outspoken stars on the map, and can speak to everything from the crusade against Planned Parenthood to music industry sexism. In October, the Cuban-American came out as bisexual via an open letter to Trump voters that was scathing, to say the least. And on Saturday, she joined an impressive list of celebrities who took part in protest marches across the country and the world.

Though Jauregui admits the Women’s March marks her first trip to the nation’s capital for a protest, she says her interest in women’s rights issues sparked while attending an all-girls high school in Miami, Florida.

There, “it was instilled in me to be a confident and courageous woman,” the singer explains. “Every single girl that I went to school with is so inspirational and so powerful and so driven and so unafraid. I think that’s something we all need to instill in each other.”

To Jauregui, this also means ensuring that women of all backgrounds and experiences are included in an intersectional feminist movement. As a young woman who is a member of the LGBT community and belongs to an immigrant family, she jokes that she falls into “three categories” of minority.

It’s a diversity of life experience that extends to the rest of Fifth Harmony’s girl-power group as well. “We’re four women who are completely different ethnicities, completely different body types, completely different walks of life and opinions,” Jauregui says.

We caught up with Jauregui just after her arrival in D.C. to talk about her “overwhelming” experience at the march, the feminism stigma, and the power of millenials to make the next generation count. Watch Fifth Harmony’s performance at the People’s Choice Awards last week below, and scroll through for our Q&A with Jauregui.

Who and what are you marching for? I’m marching for human rights in general, because the upcoming administration has clearly made a statement about who they support and what kind of regime they intend to instill. I’m marching for women, I’m marching for the LGBT community, I’m marching for immigrants. I happen to fall into all three categories [laughs], so I’m marching for myself at the end of the day and for my family and my friends. And for whoever else deserves it. What were you feeling during the march? Over-fucking-whelmed. Present, aware, peaceful, and ready to go. The most amazing thing I’ve ever experienced in my entire life. I can’t believe that I witnessed the history that I did.

I feel like a lot of people felt so alone with this new administration coming in, and they felt so betrayed. This whole entire experience is a clear indication of the fact that… we are the popular vote. This is us, out here marching. All around the world, women united, and men united, and humans alike united, and we’re not going to tolerate this. We’re not going to tolerate a fascist regime, and we’re not going to tolerate you telling us that we’re not important. Because we’re all here, and our voices matter, and we outnumber you.

How did the march alter your perspective?

I’ve spent so much time in my head and in my notes and in my journals about how much pain this world is in and how upset I am that nobody cares. Going out there today and seeing how many people really care, how many people are so down to use their voices, how many people are willing to fight tooth and nail… it was just beautiful. I was so emotional at so many points. I cried so many times. This is democracy. We are democracy.

What was the crowd like?

It was the most incredible, humbling experience to be in the presence of so many humans who were so willing to come together. When I was there, we were trying to get to the bathroom and then trying to get back into the crowd, and it was absolutely impossible because it was so packed, and there was this woman who was in a wheelchair. We were trying to get up onto the ledge, and she was like, “use my wheelchair! Come on!” She literally let us use her as a stepping stool. It was crazy. Everyone was so helpful, helping each other out.

Do you think public figures like yourself have an added responsibility to be politically outspoken?

I think that in the entertainment industry particularly, people usually get into this business because they’re trying to just be the distraction for people. But for me, I don’t see the power in having a voice, and a voice that so many more people listen to than an average… I don’t feel right having that and not using it for the sake of educating. That’s why I think I was born and given this platform to begin with. I hate attention, I hate all of that kind of shit. But I think God gave me this voice for this purpose—to use it for the sake of uniting people and making sure that everyone knows that it’s okay to use your voice. You can be a young woman, and it’s okay to use your voice. You can be as strong as you want.

Growing up in Miami, you went to an all-girls school. How did that influence the woman you are today?

Honestly, I’ve been very blessed that I was able to go through Carrollton [School of the Sacred Heart]. I attribute everything that I feel and all of the passion that I have to that school. It’s an all-girls school, and it was instilled in me to be a confident and courageous woman. “Women of courage and confidence” was the slogan, essentially, of our school. I’m just so grateful because every single teacher I encountered, all of the administration, everyone involved, men and women alike, were there for the purpose of growth of each individual girl. And each individual girl was told how special she was and how much she could influence the world. I’m literally crying thinking about it [laughs]. Every single girl that I went to school with is so inspirational and so powerful and so driven and so unafraid. I think that’s something we all need to instill in each other.

The rise of Fifth Harmony is often framed as the return of the girl group. Why do you think your music resonates with so many young girls?

Some of our songs are empowering, but I feel like more so than our music, it’s who we are. We’re four women who are completely different ethnicities, completely different body types, completely different walks of life and opinions, and you can see that when you watch an interview, when you meet us. We have an energy about us that’s so unique and so intense, and it’s because of how much power we have in us as individuals, being confident, harnessing that power, and wanting to share that with other women. I feel like a lot of women hang on to our message, and it empowers them.

Have you always been so confident in your womanhood?

I’m really lucky, because I have a mother and a grandmother who always instilled my power in me, always, from the day I was born. And my father, too. My parents never made me feel like I couldn’t do something because I was a girl, ever. It didn’t matter what I wanted to do. My father supported me 1,000 percent, all the way, and never told me, “you can’t do that because you’re a girl.” And on top of that, the school that I went to, and the power I was given with my education. I’m really lucky, I got only power handed to me, and I made use of it, and I only want to share that.

What place do you think young people have in politics?

I think the youth is the movement. I think we are the ones who are starting this revolution, and we’re the ones who are going to see it carry through and be the ones to implement it. I think we’re in a really amazing time right now of consciousness awakening, the internet and all the connections we have to each other. All the young people involved right now, on the internet, seeing the injustice and having it there in front of their faces, it’s making them passionate and it’s making them aware. All the little kids I’ve ever talked to—little, little kids, like eight years old—they know what’s up. They’re like, “What’s going on? How is Trump president?” The fact that kids can differentiate that… I think the power’s in the youth.

You wrote in your open letter for Billboard that feminism needs “a lot of work.” How can we fix that?

I think the whole stigma of the word feminism is such a problem. The only reason that anyone has an aversion to it is because it includes the word “fem,” even though it’s an all-inclusive term. I think that aversion in general is the reason why we need [feminism]. If the word “feminism” bothers you, there’s a reason why it bothers you, and only because it involves women. The issue at the end of the day that feminism fights for is equality, men and women alike. Because men also have their own stigmas that they have to follow, and stereotypes they have to follow that are detrimental to their mental health. That’s something that happens to all of us, something we’re all experiencing. By harnessing that freedom, we’re saying, “no, I want to embrace this term because it means that I get to be free.”

Are you surprised by Donald Trump’s success?

I would say I’m surprised, but I also know there is a lot of hatred in the heart of the country. It’s kind of the basis on which [the U.S.] was built, essentially, because it was built on slavery—slaves were the ones who built it. I feel like people are really empowered by money, and that’s all that [Trump] offered, essentially, besides all of the other detrimental things he said. The only people who are able to look past that are people who value the economy over human rights. That exists because money is all-powerful in this society, it’s a capitalist society, so a lot of people feel like they have no option but to progress only economically.

Do you have any thoughts on the effort to defund Planned Parenthood?

Just how important it is to recognize how they are responsible for so much more than abortion. That actually, abortion only takes up three percent of what they do, and everything else is just about female health and reproductive health, and making sure that women have a safe place that doesn’t cost an arm and a leg to get the medical attention that they need. People are dismissing a foundation that genuinely helps millions and millions of women across the nation for the sake of, just, myth.

Would you ever consider going into politics as a profession?

I think if I do anything political, it would be activism. I don’t believe in our government, currently. I don’t believe in the way that things are going. I wouldn’t want to be involved bureaucratically, I’d want to be more activism.

Is there anything you want to say to fellow marchers? I love you, and we’re together. Let’s make some changes.

0 notes

Conversation

Fifth Harmony’s Lauren Jauregui sums up her decision to take part in D.C.’s historic Women’s March on Washington neatly: “I need to walk what I talk, you know?”

Talk, she does. At 20 years old, Jauregui is quickly becoming one of the most politically outspoken stars on the map, and can speak to everything from the crusade against Planned Parenthood to music industry sexism. In October, the Cuban-American came out as bisexual via an open letter to Trump voters that was scathing, to say the least. And on Saturday, she joined an impressive list of celebrities who took part in protest marches across the country and the world.

Though Jauregui admits the Women’s March marks her first trip to the nation’s capital for a protest, she says her interest in women’s rights issues sparked while attending an all-girls high school in Miami, Florida.

There, “it was instilled in me to be a confident and courageous woman,” the singer explains. “Every single girl that I went to school with is so inspirational and so powerful and so driven and so unafraid. I think that’s something we all need to instill in each other.”

To Jauregui, this also means ensuring that women of all backgrounds and experiences are included in an intersectional feminist movement. As a young woman who is a member of the LGBT community and belongs to an immigrant family, she jokes that she falls into “three categories” of minority.

It’s a diversity of life experience that extends to the rest of Fifth Harmony’s girl-power group as well. “We’re four women who are completely different ethnicities, completely different body types, completely different walks of life and opinions,” Jauregui says.

We caught up with Jauregui just after her arrival in D.C. to talk about her “overwhelming” experience at the march, the feminism stigma, and the power of millenials to make the next generation count. Watch Fifth Harmony’s performance at the People’s Choice Awards last week below, and scroll through for our Q&A with Jauregui.

Who and what are you marching for? I’m marching for human rights in general, because the upcoming administration has clearly made a statement about who they support and what kind of regime they intend to instill. I’m marching for women, I’m marching for the LGBT community, I’m marching for immigrants. I happen to fall into all three categories [laughs], so I’m marching for myself at the end of the day and for my family and my friends. And for whoever else deserves it. What were you feeling during the march? Over-fucking-whelmed. Present, aware, peaceful, and ready to go. The most amazing thing I’ve ever experienced in my entire life. I can’t believe that I witnessed the history that I did.

I feel like a lot of people felt so alone with this new administration coming in, and they felt so betrayed. This whole entire experience is a clear indication of the fact that… we are the popular vote. This is us, out here marching. All around the world, women united, and men united, and humans alike united, and we’re not going to tolerate this. We’re not going to tolerate a fascist regime, and we’re not going to tolerate you telling us that we’re not important. Because we’re all here, and our voices matter, and we outnumber you.

How did the march alter your perspective?

I’ve spent so much time in my head and in my notes and in my journals about how much pain this world is in and how upset I am that nobody cares. Going out there today and seeing how many people really care, how many people are so down to use their voices, how many people are willing to fight tooth and nail… it was just beautiful. I was so emotional at so many points. I cried so many times. This is democracy. We are democracy.

What was the crowd like?

It was the most incredible, humbling experience to be in the presence of so many humans who were so willing to come together. When I was there, we were trying to get to the bathroom and then trying to get back into the crowd, and it was absolutely impossible because it was so packed, and there was this woman who was in a wheelchair. We were trying to get up onto the ledge, and she was like, “use my wheelchair! Come on!” She literally let us use her as a stepping stool. It was crazy. Everyone was so helpful, helping each other out.

Do you think public figures like yourself have an added responsibility to be politically outspoken?

I think that in the entertainment industry particularly, people usually get into this business because they’re trying to just be the distraction for people. But for me, I don’t see the power in having a voice, and a voice that so many more people listen to than an average… I don’t feel right having that and not using it for the sake of educating. That’s why I think I was born and given this platform to begin with. I hate attention, I hate all of that kind of shit. But I think God gave me this voice for this purpose—to use it for the sake of uniting people and making sure that everyone knows that it’s okay to use your voice. You can be a young woman, and it’s okay to use your voice. You can be as strong as you want.

Growing up in Miami, you went to an all-girls school. How did that influence the woman you are today?

Honestly, I’ve been very blessed that I was able to go through Carrollton [School of the Sacred Heart]. I attribute everything that I feel and all of the passion that I have to that school. It’s an all-girls school, and it was instilled in me to be a confident and courageous woman. “Women of courage and confidence” was the slogan, essentially, of our school. I’m just so grateful because every single teacher I encountered, all of the administration, everyone involved, men and women alike, were there for the purpose of growth of each individual girl. And each individual girl was told how special she was and how much she could influence the world. I’m literally crying thinking about it [laughs]. Every single girl that I went to school with is so inspirational and so powerful and so driven and so unafraid. I think that’s something we all need to instill in each other.

The rise of Fifth Harmony is often framed as the return of the girl group. Why do you think your music resonates with so many young girls?

Some of our songs are empowering, but I feel like more so than our music, it’s who we are. We’re four women who are completely different ethnicities, completely different body types, completely different walks of life and opinions, and you can see that when you watch an interview, when you meet us. We have an energy about us that’s so unique and so intense, and it’s because of how much power we have in us as individuals, being confident, harnessing that power, and wanting to share that with other women. I feel like a lot of women hang on to our message, and it empowers them.

Have you always been so confident in your womanhood?

I’m really lucky, because I have a mother and a grandmother who always instilled my power in me, always, from the day I was born. And my father, too. My parents never made me feel like I couldn’t do something because I was a girl, ever. It didn’t matter what I wanted to do. My father supported me 1,000 percent, all the way, and never told me, “you can’t do that because you’re a girl.” And on top of that, the school that I went to, and the power I was given with my education. I’m really lucky, I got only power handed to me, and I made use of it, and I only want to share that.

What place do you think young people have in politics?

I think the youth is the movement. I think we are the ones who are starting this revolution, and we’re the ones who are going to see it carry through and be the ones to implement it. I think we’re in a really amazing time right now of consciousness awakening, the internet and all the connections we have to each other. All the young people involved right now, on the internet, seeing the injustice and having it there in front of their faces, it’s making them passionate and it’s making them aware. All the little kids I’ve ever talked to—little, little kids, like eight years old—they know what’s up. They’re like, “What’s going on? How is Trump president?” The fact that kids can differentiate that… I think the power’s in the youth.

You wrote in your open letter for Billboard that feminism needs “a lot of work.” How can we fix that?

I think the whole stigma of the word feminism is such a problem. The only reason that anyone has an aversion to it is because it includes the word “fem,” even though it’s an all-inclusive term. I think that aversion in general is the reason why we need [feminism]. If the word “feminism” bothers you, there’s a reason why it bothers you, and only because it involves women. The issue at the end of the day that feminism fights for is equality, men and women alike. Because men also have their own stigmas that they have to follow, and stereotypes they have to follow that are detrimental to their mental health. That’s something that happens to all of us, something we’re all experiencing. By harnessing that freedom, we’re saying, “no, I want to embrace this term because it means that I get to be free.”

Are you surprised by Donald Trump’s success?

I would say I’m surprised, but I also know there is a lot of hatred in the heart of the country. It’s kind of the basis on which [the U.S.] was built, essentially, because it was built on slavery—slaves were the ones who built it. I feel like people are really empowered by money, and that’s all that [Trump] offered, essentially, besides all of the other detrimental things he said. The only people who are able to look past that are people who value the economy over human rights. That exists because money is all-powerful in this society, it’s a capitalist society, so a lot of people feel like they have no option but to progress only economically.

Do you have any thoughts on the effort to defund Planned Parenthood?

Just how important it is to recognize how they are responsible for so much more than abortion. That actually, abortion only takes up three percent of what they do, and everything else is just about female health and reproductive health, and making sure that women have a safe place that doesn’t cost an arm and a leg to get the medical attention that they need. People are dismissing a foundation that genuinely helps millions and millions of women across the nation for the sake of, just, myth.

Would you ever consider going into politics as a profession?

I think if I do anything political, it would be activism. I don’t believe in our government, currently. I don’t believe in the way that things are going. I wouldn’t want to be involved bureaucratically, I’d want to be more activism.

Is there anything you want to say to fellow marchers? I love you, and we’re together. Let’s make some changes.

0 notes