#itv broadchurch

Text

mark latimer i am in your walls.

#i hate him.#i hate every man in broadchurch#even hardy and the viccar are on thin ice.#broadchurch#beth latimer run away with me challenge#itv broadchurch

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

ITV’s Broadchurch (Real Filming Locations)

Image ©ITV Studios

Article by @warrenwoodhouse #warrenwoodhouse

Broadchurch is filmed on location in West Bay, Dorset, South West, England, United Kingdom. | Visit: https://visitengland.com/experience/explore-west-bay-coastline-seen-tvs-broadchurch for visiting information. | TV Show Official Website: https://itv.com/broadchurch

#warrenwoodhouse#2015#realfilminglocations#real filming locations#broadchurch#itv broadchurch#itvbroadchurch#west bay#dorset#south west england#england#united kingdom#uk

0 notes

Text

no I will never stop posting new David Tennant photos and saying how good he looks. look at him!

#please be respectful#david tennant#the creator#itv#itvx#genius game#new david tennant photo!!!#he looks amazing#reality show#doctor who#good omens#around the world in 80 days#broadchurch

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wish there were some Broadchurch/Whitechapel crossover fics out there... Is there any?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fancy: Morse?

Morse: No.

Fancy: But you don't know what I want.

Morse: I know the answer is no.

#Source: Broadchurch#ITV Endeavour#Endeavour ITV#Incorrect Endeavour Quotes#Endeavour#Morseverse#George Fancy#Endeavour Morse

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

had an idea for a Lewis and Broadchurch fic last night thats kinda sticking with me very much like introspective Hathaway focused post Spain maybe some stuff with a beloved priest…

1 note

·

View note

Text

Someone let me know if broadchurch season 02 is worth the watch?

I loved s01 and if it's downhill from here I'd rather not watch.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

yk that old tumblr post about bbc sharing 15 actors or whatever? broadchurch proves this theory.

#I KNOW BROADCHURCH IS ITV BUT ITS STILL BRITISH TELEVISION#broadchurch#david tennant#olivia colman#arthur darvill#jodie whittaker#david bradley

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

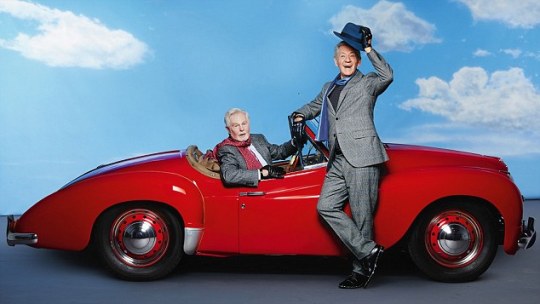

Jacobi and McKellen as grand marshals of New York City's 2015 pride march.

All Good Omens (show) fans will know Derek Jacobi as the Metatron. His brief role on Doctor Who is also getting a lot of mention in recent posts, but I'm not going to talk about any of that.

Like his Vicious co-star Ian McKellen, Jacobi has had a long and illustrious career in theatre, television, and film. McKellen and Jacobi met when they were at Cambridge.

I'm not a huge fan of the Daily Mail, but this article, an interview with the two actors, is quite interesting. I'll just quote this part:

Jacobi says he came out to his mother when he was at university. ‘She said, “All young men, go through this phase, don’t worry.” I remember saying, “Don’t tell Dad.”’ He doesn’t know to this day if she did. ‘I think she did, but I don’t know. But they were wonderful, my parents, not much was said but they kind of knew, they got it.’

McKellen hasn’t heard his friend talk of this before. ‘That’s the first time I’ve heard that,’ he says, genuinely moved. ‘I never came out to my family. Biggest regret of my life.’ It turns out he didn’t even come out to Derek at university, even though it’s always been reported that he had something of a crush on him.

��Yes, I did fancy Derek, but I didn’t act on it, God, no. It was illegal, remember. I do get on my high horse about it, because it was so difficult. There were no gay clubs you could go to. No gay bars, no gay newspaper, nothing. What there was was a bit sleazy, I suspect. One of the reasons I became an actor was that you could meet gay people. Even then everything was difficult. When you went to America they asked, “Are you now, or have you ever been, homosexual?” I lied on the form. It was a different world.’

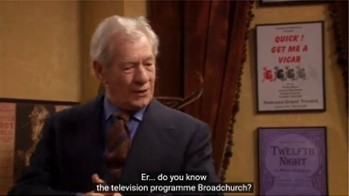

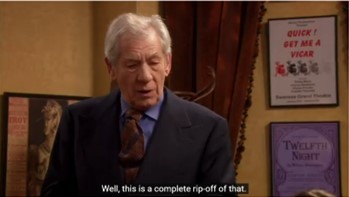

I want to talk about Vicious for a bit, the ITV britcom in which Derek Jacobi and Ian McKellen play an aging gay couple, (respectively) a homemaker, Stuart Bixby, and an actor, Freddie Thornhill, for fourteen episodes.

Freddie (McKellen) tells Stuart (Jacobi) about a part he's hoping to get.

I had to add these for the Broadchurch reference.

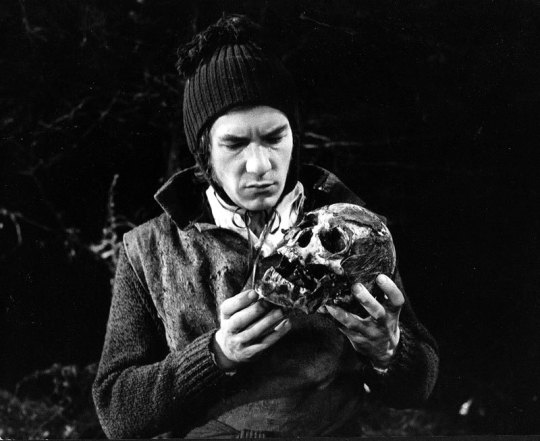

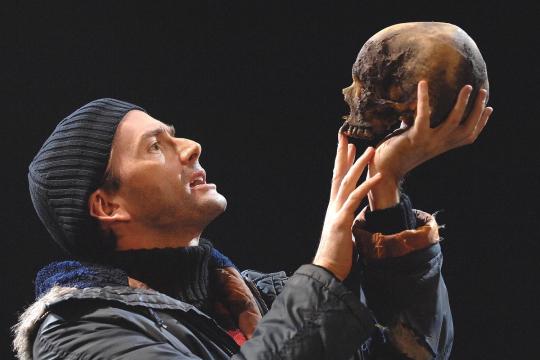

It's a law that British actors of a certain age play this part.

I couldn't find one with Michael Sheen and the skull, but here he is in the role.

McKellen did the part again at 81 in an age-blind production.

Jacobi's big breakout was the titular role in I, Claudius on the BBC in 1976.

In the '90s, Jacobi played amateur sleuth and 12th century monk, Brother Cadfael on the ITV series.

I had watched some of Vicious before, but, spurred on by Jacobi's reappearance on Good Omens, looked for it again and watched both seasons a couple of weeks ago. Because I love a good fancast and Jacobi and Sheen (at least as Aziraphale) remind me a little of each other, I couldn't help but think that Jacobi and McKellen in their youth could have played a version of Aziraphale and Crowley. (There have been a couple of posts noting this about Jacobi, and that he might have been up for the part if it had been done soon after the book came out.)

Jacobi, left, and McKellen, right (obviously).

I also think that Tennant and Sheen could have pulled off playing Freddie and Stuart in a flashback.

An even younger version of Freddie and Stuart does appear in the series, however, played by Luke Treadaway and Samuel Barnett.

Also good casting! They do a great job playing McKellen and Jacobi playing Freddie and Stuart.

Shoutout to this post by @ember-knights, that suggested Good Omens fans should check out Vicious for a glimpse of what life in the South Downs cottage might be. And also to other posts mentioning Vicious and Good Omens in the same breath, as well as comparing Sheen and Tennant to Jacobi and McKellen (which I probably reblogged but can't find right now).

Cast of Vicious: Frances de la Tour, Iwan Rheon, Philip Voss, Ian McKellen, Derek Jacobi, Marcia Warren (Wikipedia). (Yes, the upstairs neighbor (Rheon) does go on to play Ramsay Bolton on Game of Thrones. He's a sweetheart in this, though.)

Now, I don't think Crowley and Aziraphale are the same as Freddie and Stuart, by any means. Freddie and Stuart say quite cruel things to each other. The characters become deeper in the second season; it’s a little sweeter than the first. I enjoy the bitterness of the first season too, though. It is funny, and Good Omens fans may enjoy watching it if only to see Derek Jacobi (who plays the Metatron) in a comedy role and a role that's sympathetic, especially if they are not familiar with his large and impressive body of work.

I don't think Aziraphale and Crowley's life in the bookshop as a couple, not just a group of two, or life on the South Downs, would be exactly like this, but there are somehow some similarities that I don't even know how to begin to pinpoint or explicate.

Crowley and Aziraphale’s affection is always so palpable and that’s not always clear with Freddie and Stuart. Crowley and Aziraphale are so loving that, even when they're bickering, it's joyful, even when they're arguing, even when they're coming apart (temporarily) at the seams, their love is undeniable. I don’t even think their breakup was toxic; although they were desperate at that point and hurt each other badly, it wasn't what they wanted. Sometimes it's that way.

And, lest I'm putting you off Vicious here, the Ineffable Husbands are a high bar as love stories go, but you will get to see some love and affection between Freddie and Stuart too, and I'd really love to see these actors work together more. (I am happy with how the show ends up, by the way.)

Toodle-loo! Hope everything is tickety-boo with you.

#Good Omens spoilers#Good Omens#Good Omens viewpoints#Derek Jacobi#Ian McKellen#Vicious#Derek Jacobi appreciation post#***Good Omens#tickety boo

501 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview with Backstage (2024)

Jonathan Bailey is still marinating in his thoughts, andthey taste pretty sweet. Top notes of red wine, he says.

These are busy times for the witty British heartthrob. He’s speaking over Zoom from Malta, where he’s filming the next “Jurassic World” installment. And two days prior, he received his first Emmy nomination for his supporting turn on Showtime’s “Fellow Travelers.”

What’s lingering in Bailey’s mind after reaching such a huge milestone? “The nature of the story, and how that story’s come to be told,” he says of Ron Nyswaner’s limited series, a decades-spanning gay drama that’s chock-full of steamy sex scenes. For him, the Emmy nod is “an acknowledgment of [the show] meaning something much bigger.”

The 36-year-old actor radiates humility and surges with pride for his collaborators; “Fellow Travelers” also picked up nominations for lead actor Matt Bomer and for Nyswaner’s writing. Bailey believes the fact that executive producer Robbie Rogers was able to get the project on television at all is a “brilliant signifier” of changing times. He feels lucky to have been the right person for the job. And after a couple of decades in the industry, the actor’s star is about to go supernova.

Childhood stage work and gigs on 2000s teen TV shows led to roles on acclaimed series like ITV’s “Broadchurch” and Channel 4’s “Crashing.” He nabbed an Olivier in 2019 for his performance in Marianne Elliott’s West End revival of “Company.” Households on the other side of the Atlantic learned his name in 2020 when he courted lockdown audiences as Anthony, the strident head of the titular family on Netflix’s period-romance smash “Bridgerton.”

Then came the game-changing “Fellow Travelers.” Bailey plays the idealistic Tim Laughlin, a closeted congressional staffer who pursues a clandestine relationship with another man amid the witch hunts of McCarthy-era Washington. The actor is keeping up that momentum in the coming months with part one of Jon M. Chu’s highly anticipated film adaptation of the Broadway musical “Wicked” (out Nov. 22), followed by the fourth “Jurassic World” in 2025.

“Fellow Travelers” is a fitting inflection point for Bailey, considering it reflects aspects of his own gay identity. Tim’s story also illuminates a thread connecting the actor’s work, both in and out of character: always embracing the truth, shame be damned.

Born in Wallingford, England, Bailey made a beeline for the arts as a kid when he began studying music and ballet. After getting a taste of performing at a young age, he secured an agent when he was a teenager. Even now, he feels the sense of joy and wonder he discovered in those early days.

He chose not to attend drama school, instead throwing himself into professional theater, where he encountered the performance process in its most essential form. “You start with your own instincts, and then you share with others in the room in real time,” Bailey says. “You academically approach text, then you emotionally explore it. Then, you physically put it on its feet.”

Theater taught him to be observant. In rehearsals, he witnessed actors being brilliant and bold, but also making crucial mistakes. Weeks of rehearsing helped him learn how to spend time with a character as he watched his castmates play against type and expand themselves through performance. Those lessons both tested and encouraged him, and they’ve carried him throughout his career.

Since then, Bailey has gotten the chance to see plenty of giants at work. He reverently discusses performing Stephen Sondheim’s music alongside Patti LuPone in “Company” and reciting Shakespeare opposite Ian McKellen in the Chichester Festival Theatre’s 2017 production of “King Lear.”

His contemporaries also made for great teachers. He worked with Phoebe Waller-Bridge on “Crashing” and Michaela Coel on “Chewing Gum”—two certified television geniuses whose creative successes Bailey likens to the magnesium flame of a meteor. It’s an apt comparison—Waller-Bridge called him “a meteorite of fun” in a 2022 interview with GQ. (“I think I’ve always been quite naughty,” he says playfully.)

“There’s so much you take on via natural osmosis,” Bailey explains. “It’s what you watch and how you interpret things.”

For example, he thinks that every actor should see Sandy Dennis’ Oscar-winning turn as Honey in Mike Nichols’ 1966 film “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” Her performance whet his curiosity about the craft: “She is so fluid. I mean, that might be the most exposing answer I’ve given about what my inner world is like.”

Bailey’s technique is rooted in music. He plays piano and clarinet, and he approaches acting like an instrument, too. When reading a script for the first time, he experiences his character’s arc as the phrases in a song. “The way my brain works is that I see the images of what they’re doing,” he says. “When I say ‘phrasing,’ it’s like, how you get from that image to this image.”

When he was playing the bottled-up Anthony on “Bridgerton,” Bailey found inspiration in songs by Echo and the Bunnymen and Nirvana. While filming “Fellow Travelers” in Toronto, he went on long walks while listening to expansive pop music to help him explore Tim, a character whose energy radiates outward.

Considering Bailey’s process plays like a song, connoisseurs of his work might notice a motif. Sam from “Crashing,” a party boy Bailey calls “a wild, untamed animal in a tiny little cage,” aggressively maintains a facade of heterosexuality while pining for his male housemate Fred (Amit Shah). On Season 2 of “Bridgerton,” Anthony locked himself into a prison of duty and a loveless engagement to avoid acknowledging his desire for the fiery Kate Sharma (Simone Ashley).

Tim of “Fellow Travelers” is the latest in a series of sharply drawn characters confronting the tension between their assigned roles and their personal truths. Viewers first meet a straitlaced rule-follower whose Catholic piety is only matched by his loyalty to the infamous Senator Joseph McCarthy. All that changes when he crosses paths with Hawkins “Hawk” Fuller (Bomer), a crystal-eyed, debonair State Department official. Their respective closets combust on contact, and they enter into a forbidden love affair just as McCarthy’s Lavender Scare has begun purging queer people from the halls of government.

Bailey’s interior work tends to be more emotional than cerebral, but he’s a generous conversation partner who’s always game to riff on the deep stuff. Whether it’s yearning, going against expectations, or facing high stakes, the phrasing is what draws him in.

He finds a lot of gorgeous notes to play across the eight episodes of “Fellow Travelers” as the action moves from the 1950s to the ’80s, making pit stops along the way. While Hawk settles for a life of straight domesticity, Tim hurtles through a sexual and political awakening: The Beltway boy becomes an activist priest who refuses to diminish himself, especially when the AIDS crisis begins to rip his community apart.

Bailey loved being inside Tim’s head; in fact, the actor thinks of him as a hero. After experiencing the isolation of his secret relationship with Hawk, he opens himself up to the world: He comes out, moves to San Francisco, cobbles together a found family, and builds a life as his true self.

“Ron Nyswaner has spoiled Matt and me for the operatic detail that existed between [our characters],” Bailey says, “and also with Tim’s political fervor: the truth and the honesty that he demands of himself and the world around him, and the grappling with anything that is an obstacle to his own and other’s happiness.”

You can’t talk about “Fellow Travelers” without discussing its rapturous sex scenes—and not only for titillation’s sake, though the kinky encounters between Tim and Hawk certainly call for smelling salts. These sequences gave Bailey the opportunity to commit authentic queer intimacy to the screen, which members of the LGBTQ+ community rarely come across as they search for ways to understand their identities.

The trust between Bailey and Bomer informed everything they did onscreen. Before filming those scenes, the two actors talked through their approach at a café (Goldstruck Coffee on Cumberland Street in Toronto—a ribald little detail that still makes Bailey laugh). The filming itself was incredibly technical, and the actors worked with an intimacy coordinator on set. “We sort of hit the ground running, knowing exactly what was going to be required but also how to communicate throughout it,” Bailey says. “It felt immediately quite safe.”

He sensed an exciting opportunity to tell a story about transformative love amid the “wild, oppressive moment” of the Lavender Scare, dismissing any reservations about the explicit nature of the material. “Honestly, this is exactly why this show is going to be brilliant,” he remembers thinking.

The series’ milestone dramatic moments, with buttons still done up and no skin showing, carried that same sense of significance. No matter how much Tim grew over the course of his arc, Bailey says that his bond with Hawk remained an “extraordinary, material thing.”

This summer, the actor made a very Tim move when he founded the Shameless Fund, a charity that supports LGBTQ+ causes under the tagline: “Raising cash. Erasing shame.” The initiative grew directly out of his acting work—first inspired by the platform afforded to him by “Bridgerton” and further influenced by his experience on “Fellow Travelers.”

Playing Tim—or, as Bailey puts it, spending “five months doing a dissertation on queer oppression and liberation”—catalyzed his thoughts about the people who created a world where such a show could even exist. “I think in ‘Fellow Travelers,’ it’s so clear what Tim wants,” he says. “But as the world around him develops, you realize there’s so much that he can’t have, but that he can help change.”

Bailey sees that progress playing out in the next generation. He has a small role on the upcoming third season of Netflix’s queer YA hit “Heartstopper” as a dreamy academic who’s the celebrity crush of the series’ protagonist, Charlie (Joe Locke). Based on creator Alice Oseman’s graphic novel series, the show has found a passionate following of young LGBTQ+ fans.

When he watched “Heartstopper” for the first time, Bailey remembers wondering what it would have been like to see such representation on television when he was growing up. “I was so celebratory of it,” he says. “But it was obviously kind of a melancholic watch for people above a certain age, because it allowed them to grieve what they didn’t have.”

Having conquered the Regency and Cold War periods on the small screen, Bailey’s blockbuster era is imminent. He’s playing dashing love interest Fiyero in the “Wicked” films (based on Gregory Maguire’s 1995 novel), singing and dancing alongside Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande. It’s a perfect fit for the actor’s particular lens: “Musically and theatrically, I understand it massively.”

Since “Wicked” came with its own well-known songs to study, Bailey spent a lot of time with composer-lyricist Stephen Schwartz’s music in his ears rather than Kurt Cobain’s. He explored Fiyero’s interiority through the musical theater form itself: What does the act of singing express for him?

And for a character whose signature number is called “Dancing Through Life,” what metaphorical direction are his steps leading him in?

Bailey sees Fiyero as part of the same club as Tim, Anthony, and Sam, as the heightened world of Oz sends him on a journey of radical transformation. “I think about where he starts and where he ends up; he’s literally a changed person,” the actor says. “I savored the arc over two films.”

Next year, Bailey will become an action star in Gareth Edwards’ next installment of “Jurassic World” opposite Scarlett Johansson. Though details have yet to be announced, including the movie’s title, production is well underway; Bailey just finished filming in Thailand before shooting moved to Malta. A few days before we spoke, he was interacting with a fake blue-screen dinosaur (which is only a spoiler if you thought Hollywood has actually been cloning big reptiles this whole time).

But Bailey is still keeping his theater muscles toned. Next year, he’s starring as the titular monarch in Nicholas Hytner’s production of Shakespeare’s “Richard II” at London’s Bridge Theatre. “I have to go and sharpen up,” he says of returning to the stage. “You feel so sharp and dexterous at the end of a theater run—but also, you know, without a soul. Carcass levels of absolute exhaustion.”

Bailey lights up at the prospect of getting back onstage and experiencing the kinetic energy between the actors, crew, and director. He believes that the emotional and intellectual rigor of theater leads to a tight, specific piece of work. It’s an art form that requires continuous creation night after night.

This stamina comes in handy in front of a camera, too. “When you’re exhausted, you have to rely on technique,” he explains. “Technique does get you over the finish line, and you can deliver a performance that is honest and tell the story effectively and truthfully.”

Until then—and until he’s back on set with those fake dinosaurs—he’s going to soak up that Emmy-nomination afterglow for a little while longer.

“I’m actually going to go and have another glass of wine to celebrate,” he says.

Source

#jonathan bailey#jonny bailey#fellow travelers#wicked#wicked movie#theatre#backstage#backstage interview#interviews#interviews:2024#NEW!

55 notes

·

View notes

Note

NOT JOAN BEING ALL OVER LONDON??! It was said ITV didn't do this type of stuff but it was been everywhere in UK, mainly London, and I hope it means Joan is a good show and not them trying to compensate for it being bad

Hello anon,

Don't be pessimistic.

I've been told that ITV did the same for Broadchurch which was one ITV biggest hit shows.

I only read good reviews so far.

I'm so happy for Sophie! Well done ITV 👏

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

'David Tennant and Cush Jumbo walk into the Donmar Warehouse’s offices, above the theatre’s rehearsal rooms in Covent Garden, and sit down on a sofa, side by side. Tennant has that look his many fans will instantly be able to call to mind of being at once stressed – with a desperado gleam in his eye – yet mischievously engaged, which has to do with the intelligence he applies to everything, the niceness he directs at everyone. He is wearing a mustard-coloured jersey and could be mistaken for someone who has been swotting in a library (actually, he has been rehearsing a fight scene). If I am right in supposing him to be tense at this mid-rehearsals moment, I know – from having interviewed him before – that it is not his way to put himself first, that he will crack on and probably, while he’s at it, crack a joke or two to keep us all in good spirits. But some degree of tension is understandable for he and Jumbo are about to perform in a play that explores stress like no other – Macbeth – and must unriddle one of the most dramatic marriages in all of Shakespeare’s plays.

This is star billing of the starriest kind. Tennant, at 52, has more triumphs under his belt than you’d think possible in a single career (including Doctor Who, Broadchurch’s detective, the serial killer Dennis Nilsen in Des, and the father in There She Goes). Jumbo has been seen on US prime time in The Good Wife and The Good Fight and in ITV’s Vera. But what counts is that each is a Shakespeare virtuoso. Jumbo, who is now 38, won an Ian Charleson award in 2012 for her Rosalind in As You Like It and, in 2013, was nominated for an Olivier for her Mark Antony in Phyllida Lloyd’s all-female Julius Caesar. More recently, she starred as a yearningly embattled Hamlet at the Young Vic. A dynamo of an actor, she is described by the former New York Times theatre critic Ben Brantley as radiating “that unquantifiable force of hunger, drive, talent usually called star power”. Tennant, meanwhile, who has played Romeo, Lysander and Benedick for the RSC, went on to embody Hamlet and Richard II in performances that have become the stuff of legend.

Jumbo settles herself cross-legged on the sofa, relaxed in her own body, wearing a white T-shirt, dusky pink tracksuit bottoms, and modestly-sized gold hoop earrings. She looks as if she has come from an exercise class – and she has in one sense – no need to ask whether rehearsals, at this stage, are full-on. As we shake hello, she apologises for a hot hand and I for a cold one, having just come in from a sharp November morning. She is chirpy, friendly, waiting expectantly for questions – but what strikes me as I look at her is how her face in repose, at once dramatic and pensive, gives almost nothing away, like a page waiting to be written on.

Max Webster, the director, is setting the play in the modern day and Macbeth, a taut and ageless thriller, is especially friendly to this approach. I want to plunge straight in to cross-question the Macbeths. Supposing I were a marriage counsellor, what might they tell me – in confidence – about their alliance? Tennant is a step ahead: “There are two versions of the marriage, aren’t there? The one at the beginning and the fractured marriage later.” And he then makes me laugh by asking intently: “Are they sharing the murder with their therapist?”

He suggests Macbeth’s “reliance” on his wife is unusual and “not necessarily to be expected in medieval Scotland” (another excuse for the contemporary production): “I look to my wife for guidance: I don’t make a decision without her,” he explains. “We’ve been through some trauma which has induced an even stronger bond.” Jumbo agrees about the bond and spells out the trauma, reminding us the Macbeths have lost a child, but hesitates to play the game (I have suggested she talk about Lady Macbeth in the first person): “I want to get it right. I don’t want to get it wrong. I don’t know what to say… If I improv Lady Macbeth, it will feel disrespectful because you don’t know if what you’re saying on her behalf is true. And then you’re going to write what I say down and she [Lady Macbeth] is going to be: ‘Thanks, Cush, for f-ing talking about me that way.’” She emphasises that, as an actor, you must never judge your character, whatever crime they might have committed. And perhaps her resistance to straying from the text is partly as a writer herself (it was her play, Josephine and I, about the entertainer and activist Josephine Baker, that put her career into fast forward, opening off Broadway in 2015).

She stresses that the great problem with Lady Macbeth is that she has become a known quantity: “She is deeply ingrained in our culture. Everyone thinks they know who she is. Most people studied the play at school. I did – I hated it. It was so boring but that’s because Shakespeare’s plays aren’t meant to be read, they’re meant to be acted. People think they know Lady Macbeth as a type – the strong, controlling woman who pushed him to do it. She does things women shouldn’t do. The greatest misconception is that we have stopped seeing Lady Macbeth as a human being.”

For Tennant, too, keeping an open mind is essential: “What I’m finding most difficult is the variety of options. I thought I knew this play very well and that it was, unlike any other Shakespeare I can remember rehearsing, straightforward. But each time I come to a scene, it goes in a direction I wasn’t expecting.” He suggests that momentum is the play’s great asset: “It has such muscle to it, it powers along. Plot-wise, it’s more front-footed than any Shakespeare play I’ve done.” And is it ever difficult for him as Macbeth to subdue his instinctive comic talent? “Well, yes, that’s right, there are no gags! But actually, there are a couple of funny bits though I’d never intentionally inflict comedy on something that can’t take it. I hope I’m creating a rounded human being with moments of lightness, even in the bleakest times.” Jumbo adds: “Bleakness is funny at times”, and Tennant, quick as a flash, tops this: “Look at our government!” (He is an outspoken Labour supporter.) Later, when I ask what makes them angriest, he says: “Well, she [Suella Braverman]’s just been sacked so… I’m now slightly less angry than I was.” Jumbo nods agreement, adding that what makes her angriest is “unkindness”.

It is Tennant who then produces, with a flourish, the key question about the Macbeths: “Why do they decide to commit a crime? What is the fatal flaw that allows them to think that’s OK? I don’t know that they, as characters, would even know. Has the loss of a child destabilised their morality?” In preparation, Tennant and Jumbo have been researching post-traumatic stress disorder. “PTSD is a modern way of understanding something that’s always been there,” suggests Tennant – and the Macbeths are traumatised three times over by battle, bereavement and murder. “We’ve looked at postpartum psychosis as well,” Jumbo adds. They have been amazed at how the findings of modern experts “track within the play”. Tennant marvels aloud: “What can Shakespeare’s own research process have been?” Jumbo reminds him that Shakespeare, like the Macbeths, lost a child. She relishes the play’s “contemporary vibe which means it’s something my 14-year-old niece will want to see. Even though you know the ending, you don’t want it to go there. It’s exciting to play that as well as to watch it.”

A further exciting challenge is the show’s use of binaural technology (Gareth Fry, who worked on Complicité’s The Encounter, is sound designer). Each audience member will be given a set of headphones and be able to eavesdrop on the Macbeths. “The technology will mess with your neurons in a did-somebody-just-breathe-on-me way,” Jumbo explains. “You’ll feel as if you’re in a conversation with us, like listening to a podcast you love where you feel you’re sat with them having coffee.” Tennant adds: “What’s thrilling is that it makes things more naturalistic – we’re able to speak conversationally.”

Fast forward to opening night: how do they manage their time just before going on stage? Tennant says: “I dearly wish I had a set of failsafe strategies. I don’t find it straightforward. I’ve never been able to banish anxiety. It can be very problematic and part of the job is dealing with it. I squirrel myself away and tend to get quite quiet.” But at the Donmar, this will be tricky as backstage space is shared. Jumbo encourages him: “When I’ve played here before, I found the group dynamic helpful,” she says, but explains that her pre-show routine has changed since her career took off and she became a mother: “These days, I no longer have the luxury of saying: I’m going to do five hours of yoga before I go on. When I leave home at four in the afternoon, I might be thinking about whether I’ll hit traffic or, whether my kid’s stuff is ready for the next day. You get better at this, the more you do it. The main thing – which doesn’t sound that sexy – is to make sure to eat at the right time, something light, like soup, because when I’m nervous I get loads of acid and that does not make me feel good on stage. I have a cut-off point for eating and that timing has become a superstition in its own way.”

In 2020, Tennant and Jumbo co-starred in the compulsively watchable and disturbing Scottish mini-series Deadwater Fell for C4. How helpful is it to have worked together before? Tennant says it is “hugely” valuable when tackling something “intense and difficult” to be with someone you are “comfortable taking chances with”. Although actors cannot depend on this luxury: “Sometimes, you have to turn up the first day and go: ‘Ah, hello, nice to meet you, we’re going to be playing psychopathic Mr and Mrs Macbeth.’” And Jumbo adds: “I’ve been asked to do this play before and said no. You have to do it with the right person. I knew this would be fun because David is a laugh as well as being very hard-working.” He responds brightly with a non sequitur: “Wait till you see my knees in a kilt…” Are you seriously going to wear a kilt, I ask. “You’ll have to wait and see,” he laughs.

It is perhaps the kilt that triggers his next observation: “We’re an entirely Scottish company, apart from Cush,” he volunteers, suggesting that Macbeth’s choice of a non-Scottish wife brings new energy to the drama. He grew up in Paisley, the son of a Presbyterian minister, and remembers how, in his childhood, “whenever an English person arrived, you’d go “Oooh… from another worrrrld!”, and he reflects: “Someone from somewhere else gives you different energy.” And while on the Scottish theme, it is worth adding that Macbeth is the part that seems patiently to have been waiting for Tennant: “People keep saying: you must have done this play before? I don’t know if Italian Shakespeareans keep being asked if they have played Romeo…”

I tell them I remember puzzling, as a schoolgirl, over Macbeth’s line about “vaulting ambition, which o’erleaps itself and falls on th’other” – the gymnastic detail beyond me. Tennant suggests that what Macbeth has, more even than ambition, is hubris. But on ambition, he and Jumbo reveal themselves to be two of a kind. Tennant says: “Ambition is not a word I’d have understood as a child but I had an ambition to become an actor from tiny – from pre-school. I did not veer off from it, I was very focused. When I look at it now, that was wildly ambitious because there were no precedents or reasons for me to believe I could.”

“For me, same,” says Jumbo, “I don’t remember ever wanting to be anything else.” She grew up in south London, second of six children. Her father is Nigerian and was a stay-at-home dad, her mother is British and worked as a psychiatric nurse. “At four, I was an avid reader and mimicker. I got into lots of trouble at school for mimicking. My ambition was similar to David’s although, as a girl, the word ‘ambition’ has always been a bit dirty…” Tennant: “It certainly is to a Scottish Presbyterian.” “Yes,” she laughs, “perhaps I should have said Celts and Blacks… Girls grow up thinking they should be modest, right? But I had so much ambition. I knew there was more for me to do and that I could be good at doing it.”

And what were they like as teenagers – as, say, 14-year-olds? Tennant says: “Uncomfortable, plooky…” What’s plooky, Jumbo and I exclaim in unison. “A Scottish word for covered in spots.” “That’s great!” laughs Jumbo. “Unstylish,” Tennant concludes. Her turn: “At 14, I was sassy, a bit mouthy, trying to get into a lot of clubs and not succeeding because I looked way too young for my age. And desperate for a snog.”

And now, as grownups, Tennant and Jumbo are, above all, keenly aware of what it means to be a parent. Jumbo has a son, Maximilian (born 2018); Tennant five children between the ages of four and 21. Parenthood, they believe, helps shape the work they do. “Being a parent magnifies the job of being an actor,” says Jumbo, “because what we’re being asked to do [as actors] is to stay playful and in the present – be big children. As a parent, you get to relive your childhood and see the world through your child’s eyes as if for the first time and more intensely. We don’t do that much as adults.”

Tennant reckons being a parent has given him “empathy, patience – or the requirement for patience – and tiredness. It gives you a big open wound you carry around, a vulnerability that is not a bad thing for this job because it means you have an emotional accessibility that can be very trying but which we need.” But the work-life balance remains, for Tennant, an ongoing struggle: “Just when you think you’ve figured it out, something happens,” he says, “and you have to recalibrate it because your children need different things at different times.” Jumbo sometimes looks to other actors/parents for advice: “To try to see what they are doing – but you never quite get it right.”

And would they agree there is a work-life balance involved in acting itself? Is acting an escape from self or a way of going deeper into themselves? Tennant says: “I don’t think the two are mutually exclusive though they sound as though they should be – I think it is both.” Jumbo agrees: “On the surface, you’re consciously stepping away from yourself but, actually, subconsciously, you have to do things instinctually so you find out more about yourself without meaning to.”

And when they go deeper, what is it that they find? Fear is another of the motors in Macbeth – what is fear for them? “Something being wrong with one of my kids,” Tennant says and Jumbo concurs. And what about fear for our planet? Tennant says: “There is so much to feel fearful and pessimistic about it can be…” Jumbo finishes his sentence: “Overwhelming.” He picks it up again: “So overwhelming that you don’t do anything.” Jumbo worries about this, tries to remind herself that doing something is better than doing nothing: “If everybody did something small in their corner of the world, the knock-on effect would be bigger.” Tennant admits to feeling “anxiety” and distinguishes it from fear. Jumbo volunteers: “I recognise fear in myself but don’t see it as a helpful emotion. It’s underactive, a place to stand still.”

As actors who have hit the jackpot, what would they say, aside from talent, has been essential to their success? Tennant says: “Luck – to be in the right place at the right time, having one job that leads to another.” Jumbo remembers: “Early in my career, I had a slow start. You have to fill your soul with creative things, which is not always easy if you can’t afford to go out. You have to find things that are free, get together with people who are creative and give you good vibes and not people who are bitter and jealous or have lots of bad things to say about the world. This tends to bring more creative things to you.” Tennant observes: “As the creative arts go, acting is a difficult one to do on your own – if you’re a painter, you can paint – even if no one is buying your paintings.” Jumbo chips in: “Because of that, it can be quite lonely when it’s not happening.” “Tennant concludes: “It’s bloody unfair – there are far too many good actors, too many of us.”

And are they in any way like the Macbeths in being partly governed by magical thinking – or do they see themselves as rationalists? (I neglect to ask whether they call Macbeth “the Scottish play”, as many actors superstitiously do.) “I am a rationalist. I’m almost aggressively anti-nonsense,” Tennant says. Jumbo, unfazed by this manifestation of reason, speaks up brightly: “I’m a magical thinker, I’m half Nigerian and that’s all about magical realism and belief in energy. If something goes my way, I think: God, I felt that energy. And the thing that drew me to theatre as a kid was its magic.” And now Tennant, alerted by the word “magic”, starts to clamber on board to agree with her – and Jumbo laughs as they acknowledge the power of what she has just said.'

#David Tennant#Hamlet#Richard II#Cush Jumbo#Deadwater Fell#Macbeth#Donmar Warehouse#There She Goes#Broadchurch#Dennis Nilson#Des#Doctor Who#As You Like It#Julius Caesar#Max Webster#Josephine & I#Gareth Fry

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wish I could watch Broadchurch for the first time again

I remember watching it on not-entirely-legal, shit-quality online streams of ITV when it was first airing in the UK because I was so desperate to watch it at the same time as the UK and to not have to avoid online spoilers 😂

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

"God will put you in the right place": a mini-essay about Broadchurch and fate

[This obviously contains major spoilers for series one of Broadchurch, which you should really watch if you haven't, and should still watch even if you read this post anyway.]

Fate is tricky to work with in writing. We want to believe our lives have meaning; in fiction, we can set it up so that the characters’ lives do. This was always meant to happen, or all these things happened for this reason. But the possibility of fate can also undermine the characters’ agency. If all this is part of some unknowable higher plan, then the characters’ actions no longer come from who they are and what they want and think and believe. They’re just executing a script. It doesn’t mean anything to us anymore.

I think the mistake often made is that the fate question—of whether or not there is such a thing happening—is given too much power in the story itself. That the way it’s set up, either fate can be subverted and the characters really are in control after all, or the story is arbitrary and meaningless. Which really only leaves you one kind of story to tell: the one where the heroes defy fate. There’s nothing wrong with that kind of story, but it wears the concept out quicker when there’s only one major variant of it to play with.

What’s more interesting narratively is when the fate question, regardless of what you think the answer is, is decidedly secondary to the characters’ actions. When they engage with the idea, but the story still clearly hinges on what they do, and those things matter whether or not fate actually exists.

A really good execution of this appears in a kind of story you wouldn’t really expect to deal with fate: the first series of the ITV procedural Broadchurch. And it’s very much a minor point in the overall story, which involves the murder of a child in a small English coastal town and what that does to the community. But it’s used very effectively to draw together the threads of a character’s story and make sense of who they’ve been this entire time.

Alec Hardy (David Tennant) is a police detective who comes to Broadchurch just before the murder, a year or so after a high-profile case of his collapsed and took his marriage and his health down with it. From the outset, it’s clear that he does not want to be there: he hates everything about the place, and he doesn’t think the police department—including DS Ellie Miller (Olivia Colman), who resents his disdain for her community and his taking the DI position she was promised—is competent to handle a murder investigation. The most pressing question about Hardy is why the hell he is there. Now and again an answer is offered: “You came here to lie low,” his Chief Super says, which he disputes; “It’s penance,” he tells the doctor who warns him that he’s driving himself to a very imminent early grave. Dragging himself back to work after a near-fatal heart attack, he insists to Miller, “I can still solve this. Otherwise, why am I still here?”

The status of DI Hardy’s religious faith is uncertain. When Miller asks him about it, he replies, “I pray nightly that you’ll stop asking me questions.” He attends church only to observe the behaviour of the townspeople, all of whom are potential suspects; he spars with the vicar over the church’s place in the murder investigation. He explodes at a self-professed psychic who claims to have received messages from the murdered boy, yet is visibly affected by the message the man has for him: “She says she forgives you about the pendant.” Despite declaring the man a charlatan and denying that the statement means anything to him, Hardy, desperate to solve the case before he’s removed for being medically unfit, contacts him again and asks for whatever he’s got. “You’ve been here before,” the psychic tells him.

The beginning of the end of the story takes place on the beach near where the murdered boy was found. Hardy—who, minutes before, was told by the Chief Super to clean out his desk, and responded with “I think I know who the killer is”—has called Miller to meet him there. He tells her a story that does not seem to have anything to do with anything.

“I was here before. On this beach. I came here as a kid. With a tent, some campsite near the cliff. I tried looking for it when I first came… Didn’t remember I was here till the day I arrived. It freaked me out. Those bloody cliffs still there, still the same. I used to sit under them and get away from my parents arguing. They kept bickering till the day Mum died. Last thing she ever said to me: ‘God will put you in the right place, even if you don’t know it at the time.’”

He sends Miller off to do something he knows is inconsequential, telling her before she goes, “You've done good work on this.” And then he traces the murdered boy’s mobile phone to the murderer, DS Miller’s husband.

The reason Hardy tells that story when he does is that he’s finally reached the end of it. When he figures out who the killer is, he also understands exactly how devastating that revelation will be. And he has his answer for why he’s there—why he’s in Broadchurch, on this case, still alive at all. Because Ellie Miller was supposed to be the DI, and it would’ve been her case to solve. She would be the one making these connections, tracking the mobile phone, confronting her own husband. Nobody in Broadchurch has ever dealt with a case like this; none of them are prepared for what it will do to them. He knows, which is why when he arrests her husband, DS Miller is in a closed interrogation room with a different suspect, and doesn’t know what’s happened until he takes her out of the interrogation and tells her himself.

Whether or not it’s true that Hardy was somehow meant to be there is not actually critical to the story. The only thing that matters is the meaning that he ascribes to it all, and how that carries him through to the end of his story. He knows that he’s dying. He’s wrapping up his affairs, which includes telling the local paper what really happened on that other case. (“Just do me a favour and tell the family first, will you? Just tell them I haven’t given up on Sandbrook, and that the case is still open.”) It’s significant that, in the story he tells Miller, his mother’s words were the last thing she said to him before dying. He needs them to be true, needs it all to have meant something.

What Hardy actually does at the end of the story has the same impact whether there’s any such thing as fate or not. He solves the case, but more than that, in some small way he’s able to mitigate some of the damage it does to Ellie Miller, because he’s been there before and can see it coming. That is meaningful to him. And it may be that he was able to do that because he was looking at the situation in a certain way, trying to figure out what needed to be done that he, personally, needed to be there to do. It doesn’t matter if the events that brought him back to Broadchurch, and reminded him of his mother’s last words, were fated to happen or a series of coincidences; they have meaning because he found meaning in them.

#broadchurch#fynn posts#update on the alec hardy situation: apparently still having an alec hardy situation#writing

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jakes: Please, I'll give you money if you shut up.

Morse: I'll give you more money to be less of an idiot.

#Source: Broadchurch#ITV Endeavour#Endeavour ITV#Incorrect Endeavour Quotes#Endeavour#Morseverse#Peter Jakes#Endeavour Morse

28 notes

·

View notes