#jiaoling aoqun

Note

Do you think Hanfu should have a standard style? I mean, we can wear everything but there is this style which representes Hanfu, I think 齐胸襦裙 could be the best style to represent the standard because it cheap, good quality in general and comfortable! What do you think? Or it is better 袄裙?

Hi! Thanks for the question, and sorry for taking ages to reply! (image via)

No, I personally don't think hanfu should have an all-encompassing standard style. Rather than somehow mandating a standard style for everyone, I think it's better to let individual groups, organizations, and institutions set their own standard style if they wish.

Furthermore, as I explained in my post on how I feel about the inconsistency of the hanfu revival movement, even if there was a standard style, it would be very difficult to enforce.

If I had to choose a standard style, I'd probably go with the 交领襦裙/jiaoling (cross-collar) ruqun (image via):

I'd choose jiaoling ruqun because it's:

the most representative style of hanfu imo

commonly depicted in media (well-known)

relatively comfortable & easy to wear

unisex

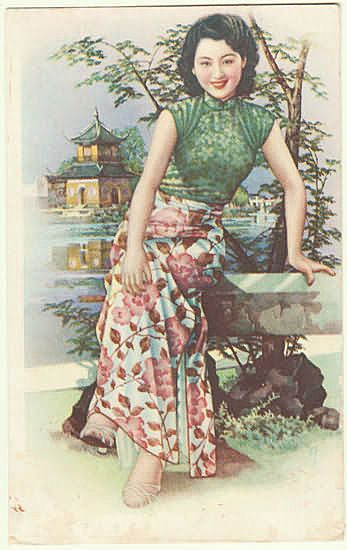

As for the two options you suggested - 齐胸襦裙/qixiong (chest-high) ruqun & 袄裙/aoqun - while qixiong ruqun is iconic as the representative women's hanfu style of the Tang dynasty, it's not as convenient to wear compared to the other two styles (image via):

Compared to qixiong ruqun, aoqun is probably the better choice when considering convenience & comfort. It's also the representative women's hanfu style of the Ming dynasty, and thus more recent compared to other styles (image via):

With that said, I stick by my opinion that a representative standard style is not necessary for the hanfu revival.

Hope this helps!

#hanfu#jiaoling#qixiong#ruqun#aoqun#hanfu movement#ask#reply#reference#>100#chinese fashion#chinese clothing#china

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ming Style Aoqun for Autumn

from: 411's Wardrobe

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abridged history of early 20th century Chinese womenswear (part 4.1: 1930s-silhouette & design)

Source here

Previous posts in the series:

Part 1: 1890s

Part 2: 1900s & 1910s

Part 3.1: 1920s-silhouette

Part 3.2: 1920s-design details

Part 3.3: 1920s-accessories, hair & makeup

Intro/Context

*This is gonna be a long one so bear with me.

The 1930s was a very iconic decade in Chinese fashion history and commonly considered the golden age of the cheongsam. Yes, the one piece dress cheongsam has FINALLY managed to surpass aoqun and aoku in popularity, in fact it completely dominated Chinese fashion for the coming four decades. The 1920s flat, boxy look was banished to the deepest pits of hell and for the first time in centuries Chinese clothing began to emphasize women’s natural curves, while retaining the slenderness of the 1920s silhouette.

Let’s start by clarifying a couple things about the origins of cheongsam. As we have seen in my previous posts on the 1920s, the one piece proto-cheongsam, the two piece and three piece aoqun coexisted as variations of the same silhouette in the late 20s; it’s not entirely clear where the one piece dress came from as it seemingly just sprouted out of nowhere. Scholars and people on the Internet have long debated the true origins of the cheongsam, with some arguing that it was based off of men’s clothing and some arguing Manchu womenswear. There’s a grain of truth to both of these arguments and I think it’s worthwhile to briefly address these two claims and their relations to the etymology of the word cheongsam.

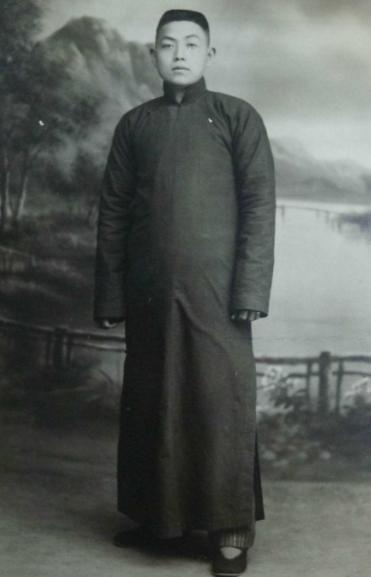

In regards to the menswear argument, historically (I’m not sure how far back this goes) men in China wore a single robe as the outermost layer, in contrast to women who wore two piece ensembles at least since the 14th century. In earlier times (I mean the Ming Dynasty) civilian Chinese men’s robes had the 交领 jiaoling, a y-shaped crossover collar; as a result of Manchu conquest in the mid 17th century, Han Chinese men adopted the Manchu style robe which was collarless and closed with 盘扣 pankou, long braided/knotted buttons whose resemblance to European frog closures I don’t know how to explain. Then again in the 19th century Manchu fashion started taking inspiration from Han Chinese fashion for whatever reason and the Manchu men’s robe gained a 立领 liling, a standing collar, which became a thing in late 16th century Han Chinese womenswear. The men’s robe, called 长衫 changshan (literally “long robe”) in the early 20th century, was exactly this, a floor length robe closed with pankou at the side, with a standing collar and slits down both sides. The word “cheongsam” is Cantonese and would be spelled changshan in Mandarin, so if you follow this train of thought it’s not difficult to see the similarities between cheongsam and changshan.

Source here

Photograph of a man in changshan.

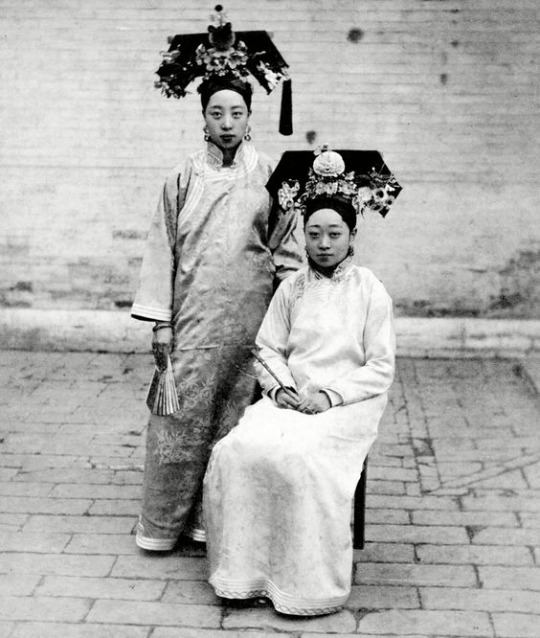

The Manchu womenswear story goes like this. In the beginning of the Qing Dynasty in the mid 17th century Manchu women wore robes very similar to those of Manchu men, collarless, floor length and closed with frog closures. There were two styles, the 衬衣 chenyi which opens on the bottom right side where the closures are, and the one with slits down both sides (like the cheongsam) which developed later, called a Chinese word I don’t know how to spell because I’m illiterate. In the 19th century Manchu women were also inspired by Han Chinese women’s fashion and added standing collars to their robes and they remained this way into the 1920s and 30s, so there was a possibility they influenced the design of the cheongsam. The common word for cheongsam in Mandarin is 旗袍 qipao, which means “banner robe”, banner being a reference to the Qing Dynasty Manchu eight banners. From the Mandarin word it could be deduced that the source of inspiration for cheongsam was Manchu womenswear.

Source here

1910s/20s photograph of two Manchu ladies.

For me personally, the Manchu womenswear explanation makes a bit more sense because if you look at photos of Manchu women’s clothing in the 1920s and 30s they visually resembled the design of cheongsam with the trims and patterns. However, the true inspiration for the cheongsam may as well have been a combination of all the factors listed above, or none of them.

Silhouette

Like I briefly discussed in the post on 1920s silhouette, the late 20s/early 30s silhouette was a knee length, skimpy dress with tight sleeves (could be short or long) and a standing collar. This could take the form of cheongsam or a two piece combo with a long vest and long sleeved shirt. The hem of the dresses could either be flared like trendy Western dresses or have short slits down both sides. It should be noted that the slits in the late 20s and early 30s were very short, usually less than 10cm (approximation by looking, I don’t own any period originals), because the skirts were already quite short and roomy so didn’t require high slits to allow ease of movement. The waistline was emphasized but the overall silhouette still appeared boxy due to the flat chest. The early 30s silhouette was peak Deco and deserves more recognition; oftentimes it gets incorrectly categorized as 20s because it looks like a stereotypical flapper dress, but this silhouette was very specific to 1929-1931.

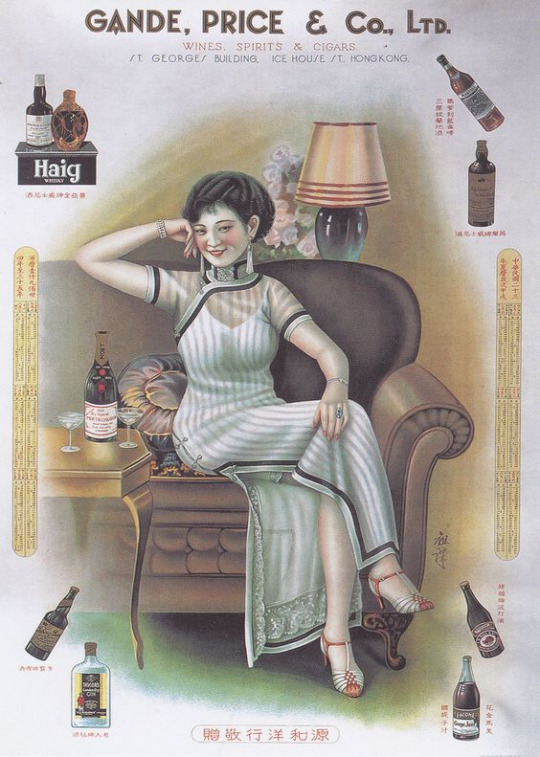

Source here

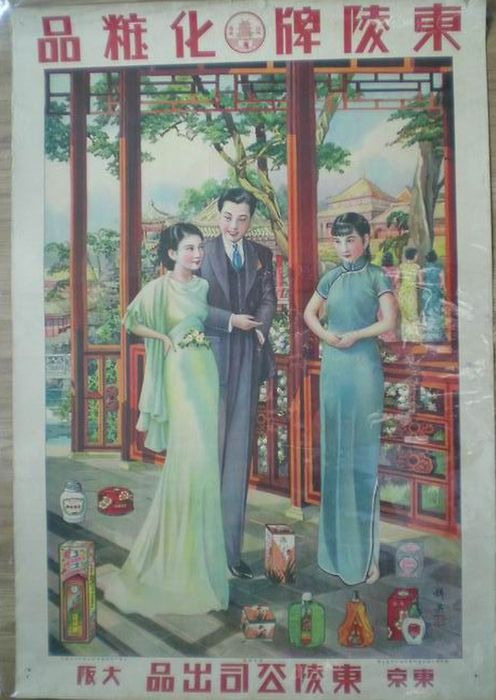

Kwong Sang Hong ad from 1930. The lady on the left is wearing a two piece combo----the vest and sleeves are separate.

By 1932 the skirt has become a tad longer but not longer than mid calf, and soft, drapey fabrics were used instead of the more stiff and structured fabrics of 1929-1931. Although the cheongsam was becoming increasingly popular, the aoqun didn’t die, it had crystallized (Drag Race reference) and adopted the same silhouette as the cheongsam: fitted at the waist and with form fitting sleeves. In fact it never really died out, aoqun and aoku are still alive and well today in rural areas. The folk/traditional outfits of many rural Chinese communities today take the form of aoqun and aoku because the cheongsam was worn primarily in the cities and didn’t quite spread to the countryside.

Source here

Kwong Sang Hong ad from 1932. Here you could see the increasing length of the skirt.

The iconic/stereotypical long silhouette came into being around 1934. All of a sudden, the cheongsam became more unified in design elements; collars were always very tall and closed by three or four pankou at the front, sleeves were always either short or full length and the hem was always ankle length. Because of the increased length of the cheongsam, higher slits had to be made to allow freedom of movement. These usually reached the knees or mid-thigh. Around 1934-36 the trend of layering with transparent outer dresses invented in the late 20s came into full fruition. There were many examples of women wearing a transparent/translucent outer cheongsam, showing a petticoat with spaghetti straps underneath, which could have a flared hem or slits like the outer layer. These were usually but not always white, and commonly had lace trim. This petticoat was not the innermost layer though, shorter petticoats or drawers with camisoles/brassieres combinations were worn as undergarments.

Source here

Cover of The Young Companion from 1934. This magazine is iconic and their covers are great primary sources!

Source: A Weary Traveler on Flickr, link

An ad from 1934. You could see the drawers peeking out from under the slit petticoat.

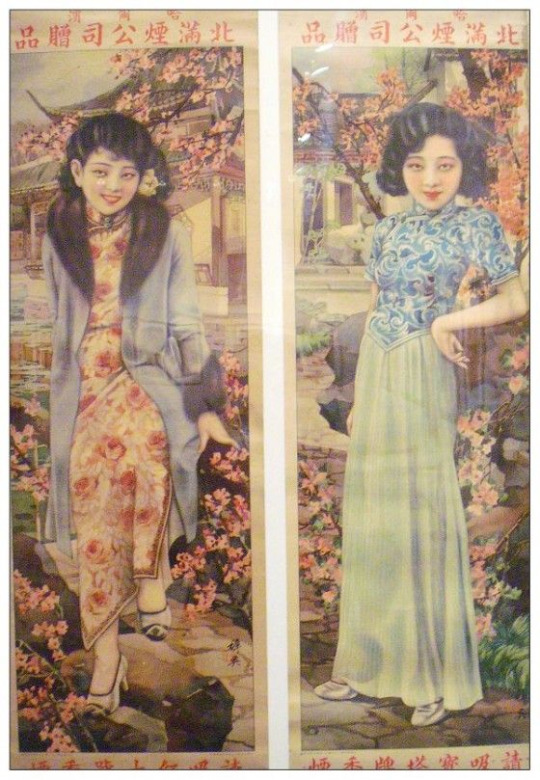

The aoqun still refused to give up and adapted to the new silhouette. However, it became increasingly rare and fashionable urban women would seldom wear it, so around this time the aoqun evolved into somewhat of a conservative symbol.

Source here

Cigarette poster from the mid 30s.

Source

Artwork by Ye Qianyu showing cheongsam and aoqun designs, Ling Long magazine 1931 issue 30.

Source

Mid to late 30s aoqun, the skirt is constructed like a cheongsam skirt, with slits.

The short vest trend of the 20s still made occasional appearances but was otherwise practically extinct.

Source here

Mid 30s mosquito repellant ad. (Why do these vintage Chinese advertisements always look so gay? I’m living for it)

More well to do Chinese women began wearing actual Western evening dresses for formal occasions. The Western evening silhouette of this time emphasized slenderness, broad shoulders, tapered waist, small bum and a long, flared skirt hem. It’s easy to see how this silhouette has influenced the silhouette of cheongsam.

Source: lai yiching0926 on Pinterest, link

A lady in Western evening dress, a man in Western attire and a lady in cheongsam. All fashionable.

Source

Western evening dresses were a hit among actresses.

Source

Hu Die in an evening dress with puffy sleeves and a train.

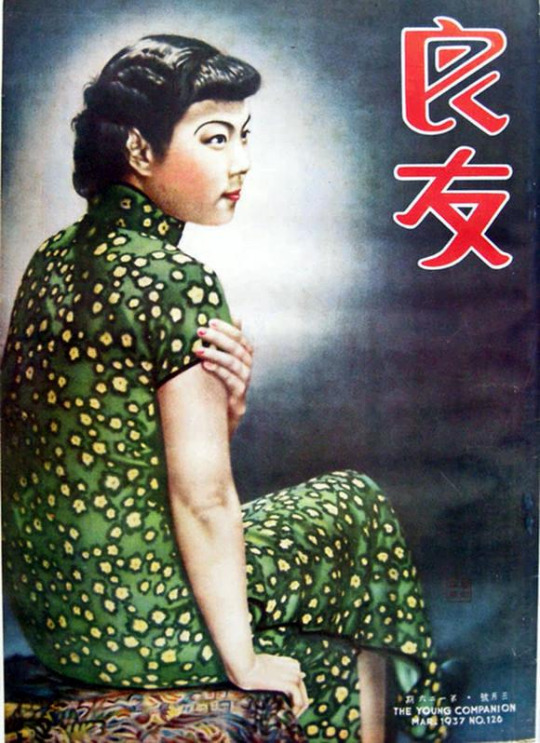

Around 1936-37 the design of cheongsam became less extravagant. The transparent trend had significantly toned down and most cheongsam of the late 30s were of opaque fabric. Cap sleeves (very short sleeves that reach out just a bit from the shoulder) became more common at this point, replacing the short and long sleeves. The slits moved lower, often knee length. The collar also began to become shorter. This increasing interest in simplicity may have something to do with the ongoing war with Japan and the scarcity of materials it caused, but I’m very uninformed on political history of this era so if you know more about it please leave a comment.

Source here (the original page disappeared, I found this from a Baidu image search)

Cover of The Young Companion from 1937.

By the late 30s, especially 1938-39, almost all cheongsam had cap sleeves----or were straight up sleeveless----and a low collar accommodating one to two buttons. The slits were usually knee length or lower, but the overall cut of the skirt was more generous and roomy than the mid 30s so it was still fairly easy to move in. The transition to the 1940s silhouette is almost complete.

Source here

Late 30s/early 40s poster.

A note about the construction of clothes in this period. Western dressmaking techniques were still not used on the main body of the dresses----there were no darts or tucks to take in the waist, the hourglass shape was achieved by curvy front and back pattern pieces; I talked about the Chinese dressmaking and pattern drafting method in my 1920s post. To clarify the confusion about the 中缝 center front seam in that post, by relooking at 20s and 30s photographs of dresses with striped patterns it’s obvious that there was no shoulder seam and no center front/back seam, so I deduce the front and back pieces of 30s cheongsam were one single piece cut on fold at the shoulder seam and connected only at the closures and underarm seams. I’ve read about this technique called 拔襟 where in order to make the side closures meet after binding and using the seam allowances at the raw edges, dressmakers would just wiggle and stitch the cheongsam together as usual, causing some parts to be slightly on bias and fit better. The article is here. This wasn’t yet the case in the 1910s, as some photographs showed robes with an obvious center front seam. This was probably because 1920s and 30s clothes became much more form fitting and therefore required less fabric so the pieces could be fitted on a continuous length of fabric. Dressmakers were also no longer troubled by the narrow fabrics of pre-industrial times----fabrics in the Ming Dynasty were commonly around 60cm wide, very difficult to cut the wide robe pieces on a single length of fabric----as machine spun fabrics could be much wider.

Design details

The beginning of the 30s continued the use of unusual Art Deco fabrics invented in the late 20s. There was this trend of attaching flowy pleated fabric/ruffles to the sleeves, making the sleeves flared and drapey; this was sometimes also done to the main body of the dress, resembling early 20s Western eveningwear decoration techniques.

Source here

The collar of the early 30s was often side closing or had concealed closures, so the front looked like a continuous piece of fabric, unlike earlier and later collars which unanimously had visible front pankou closures. The skirt hem could be finished with binding, scalloped/geometric edges, uneven hems or have no visible finishes at all i.e. raw edge enclosed in lining. Patterned trims were less popular than they were in the 1910s and 20s but still in use.

Source here

Early 30s portrait, side closing collar.

The most noteworthy design detail of mid 30s cheongsam was, in my opinion, the use of binding. Since the overall 30s aesthetic stressed simple elegance, beading, flowers, pearls and other late 20s decorations disappeared and 30s cheongsam relied on only the cut and the fabric to be beautiful; binding was therefore a good way of adding accents to the otherwise plain garment. 30s cheongsam could sometimes have two or even three rows of binding but thin, single row binding was also used and equally fashionable.

Something important about the collar: a big departure from the 20s/early 30s side closing, smooth collars was that the collars of the mid 30s were always front closing and more rounded around the edges, resembling what people nowadays would call a Chinese collar. However these were very, very tall and would cover the neck completely without leaving a gap down the front like a lot of modern cheongsam collars do (the gap is also more of a 50s and 60s thing). Between around 1933-36 it was very common to have two rows of wide binding, usually in a shiny fabric. I speculate that the double row binding was constructed by first stitching two pieces of binding together right sides together, then attached to the raw edge as one piece of binding after ironing open the seam. If anyone is a period cheongsam maker please comment about this.

Source here

High collar, double row binding (also used as decorative element), photograph from mid 30s.

Another style of binding was three rows of very thin binding with some space between them. I’m not very sure how this would be constructed so I assume the inner two rows were simply topstitched and then folded over and finished by hand with whipstitches or backstitching through the two invisible layers. I remember reading somewhere that this finish is called a 电车滚 (“train track binding”) because it looks like train tracks, but I’m not sure. This style was popular throughout the 30s but was slightly more common in the later part of the decade.

Source here

Cover of The Young Companion from 1939. Triple row binding with spaces in between.

Fabrics with a relatively large, repetitive pattern, such as florals or geometric print, were the most common. Toward the end of the 30s plaid and checkered prints were especially popular as well, usually in earth tones. Completely plain fabrics, or unicolor fabrics with tone on tone embroidery could be used as well. Contrary to popular modern opinion, stereotypically “traditional Chinese” fabrics were not really a thing in the 30s; the shiny silk with small gold embroidery patterns was not popularized until the 50s when some white people in the West decided cheongsam was cool.

Part 4.2 on hair, makeup and accessories coming soon!

#1930s#1930s fashion#vintage fashion#chinese history#chinese fashion#historic fashion#cheongsam#abridged history of early 20th century chinese womenswear

368 notes

·

View notes