#jugones

Text

Cuando llevas a tu abuelo a dar una vuelta en el coche nuevo

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

BlackPointGame ⚫️ #aabon35 http://aabon35.blogspot.com

Jeu de société Black Point 🎲

Origine : Espagne 🇪🇸 Joueurs : 2 à 9

Jetons : 2 à 22 Difficulté du jeu : Facile

Temps : Variable (# phases et # jetons)

Type : Course (uniquement, équipe, questions)

Coût : gratuit (impression gratuite sur Internet)

#dadosytableros#juegos#juegosdemesa#cartas#boardgames#boardgamesofinstagram#bgg#boardgamesphotography#boardgamescommunity#gamenight#nochedejuegos#boardgaming#ludopedia#playgames#jugones#meeple#boardgameaddict#geeky#boardgamegeek#tabletop#tabletopgames#bggcommunity#boardgamepassion#jeuxdesociete#shoutout

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“No quiero creer…”: El vídeo viral de Pedrerol que debería ver Pedro Sánchez

El periodista deportivo y presentador de ‘Jugones’ y ‘El Chiringuito de Jugones’, Josep Pedrerol, ha visitado ‘El hormiguero’ para mantener una entrevista con Pablo Motos, donde ha expresado de manera abierta su opinión sobre el acuerdo de Pedro Sánchez y Junts para la amnistía.

El veterano periodista ha pedido al presidente del Gobierno Pedro Sánchez, que se lo piense: “Tienes tiempo Pedro”

“No…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

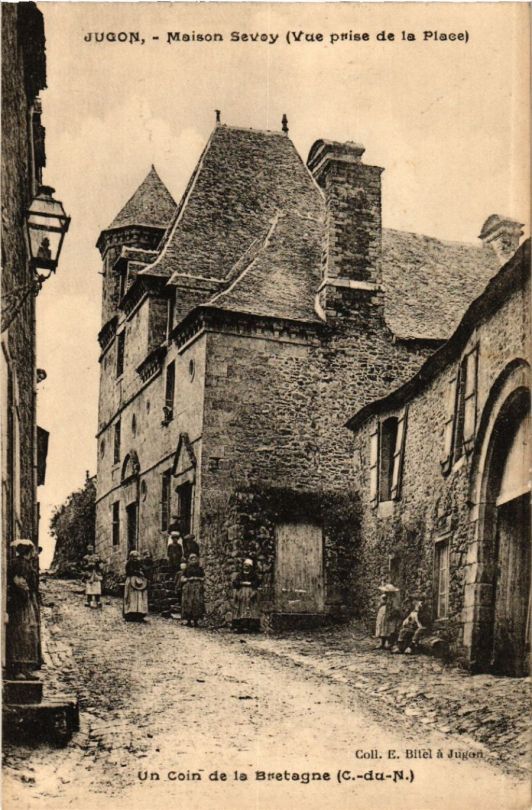

Medieval house in Jugon, Brittany region of France

French vintage postcard

#historic#jugon#photo#briefkaart#vintage#region#sepia#brittany#photography#medieval#carte postale#postcard#postkarte#france#postal#tarjeta#ansichtskarte#french#old#house#ephemera#postkaart

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

#pokémon#pokemon#pokeblogging#pokeblr#pocket monsters#pkmn#dewgong#cloyster#jinx#lapras#articuno#Freezer#Laplace#Rougela#Parshen#Jugon

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Felt like doodling baby Katellig and her mother, Jugon, back when they still lived on the family farm

[Do not use/repost]

#DnD#Dungeons and Dragons#aasimar#monk#well not yet monk back then but#OC: Jugon#OC: Katellig#My OCs#Panadu#Truc Draws

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

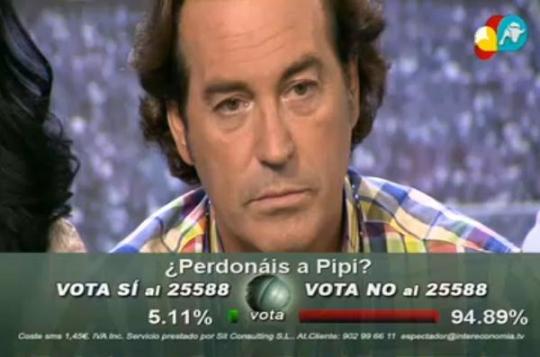

Lo perdonáis?

#attack on titan#shingeki no kyojin#attack on titan fanart#aot fanart#eren jaeger#eren aot#mikasa ackerman#armin arlert#el chiringuito de jugones#redraw#my drawings

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Los Jugones: Los amigos, ¡siempre unidos!

(Castellano – A PARTIR DE 8 AÑOS – PERSONAJES – Los Jugones)

Leo y su equipo tienen que jugar un importante partido fuera de casa. Pero de pronto llegan las malas noticias: su portero es sancionado con tarjeta roja y Leo deberá jugar en el puesto de guardameta… ¡aunque él sea delantero! ¿Lo hará bien? ¡Es el momento de que Los Jugones demuestren que pueden mantenerse unidos incluso cuando las…

View On WordPress

#8469628291#9788469628294#¡siempre unidos!#Bruño#Frauke Nahrgang#Libros de deporte y juegos al aire libre para niños#Libros de fantasía y magia para niños#Libros Guadarrama#Libros infantiles para lectores intermedios y avanzados#Los amigos#Los Jugones#Nikolai Renger#Roberto Vivero Rodríguez

0 notes

Photo

DESPUÉS DE LO DE AYER, HA LLEGADO PAU ARRASANDO! 🙌😂🙌 #astarisborn 😸 #hayqueenchufardondesea 😅 #jugon 🙌🙌 #lanuevageneración #conlacrew💪💪 https://www.instagram.com/p/CiFRibDts4g/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

Immediately after Falaise, the king had tried to limit Breton patriotism by remarrying his rebel son’s future mother-in-law, Duchess Margaret, to Humphrey IV de Bohun, Lord of Carentan in the Cotentin and constable of England. Margaret had likely been active in rallying support against Henry in the war, so the king could not trust leaving her in charge of his son and the heiress of Brittany, Constance. After the Bohun marriage, Margaret either chose or was not allowed to visit her daughter until sometime between 1187 and 1199, at least six years after the death of her second husband and possibly during the divorce of her daughter from her second husband Earl Ranulf III of Chester. Mother and daughter did not appear to meet again for at least thirteen years and when they did encounter each other it was on Breton soil at Jugon-les-Lacs, southeast of Saint-Brieuc.

-Melissa Pollock, The Lion, the Lily and the Leopard: The Crown and Nobility of Scotland, France, and England and the Struggle for Power (1100-1204)

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

1) In a series full of great plot twists, this has to be one of the greatest

2) I don’t know why they translated this as jugon instead of dugong, but I did find out that jugon is what the pokemon dewgon is called in Japan, and that makes the whole scene even funnier

#opbackgrounds#one piece#ch423#I lol'd#kokoro#-1 translation point#but also#+1 translation point#she was wearing those shells under her uniform the entire time#the manwoman#and her lipstick never smeared the entire time

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pedri receiving the JUGON! de Oro 2021 - 22 trophy

March 22, 2023

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

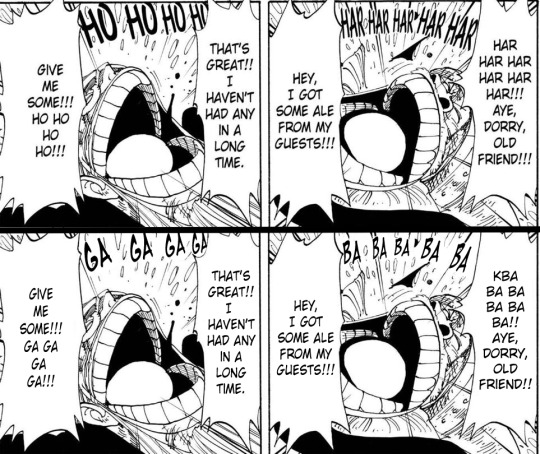

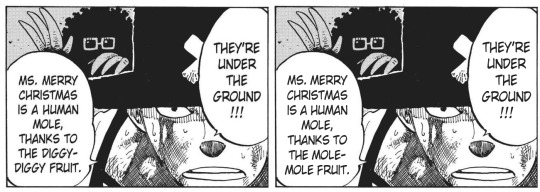

Alabasta change log

(please check pinned post for links)

here are the other edits done, along with zolo:

Changed ‘Neptunians’ to ‘Sea Kings’

edited Dorry and Broggy’s laugh

changed ‘Elbaph’ to ‘Elbaf’

Changed Luffy’s ‘hee hee hee’ laughs to his original ‘shi shi shi’ (edited this in the East Blue saga too!)

Altered scenes where ‘rub out’ is used in reference to kill

changed instances of ‘snail-o-phone’ to ‘den den mushi’

edited instances where Kureha was called ‘doctor’ to ‘doctorine’ (when referenced as a name)

changed ‘Portgaz’ to ‘Portgas’

edited ‘jugon’ to ‘dugong’

changed koza’s (child) nickname from ‘chief’ to ‘leader’

changed ‘sand-sand band’ to ‘sand-sand clan’

fixed ace’s tattoo to match the final whitebeard logo design (see the extended post here)

changed “climate baton” to “clima-tact”

Changed Chopper’s ‘boosts’ to ‘points’

Changed ‘Ultra Spotbill’ and ‘Super-Sonic Duck Squadron’ to “Super Spot-Billed Duck’ and ‘Super Spot-Billed Duck Squad’

Changed ‘Diggy-Diggy Fruit’ to ‘Mole-Mole Fruit’

Changed ‘Ponegliff’ to ‘Poneglyph’

edited double pages so they ‘connect’ (read here for more details)

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

#pokémon#pokemon#pokeblogging#pokeblr#pkmn#pocket monsters#poliwrath#tentacruel#slowbro#dewgong#cloyster#starmie#gyarados#lapras#omastar#kabutops#Omstar#Laplace#Parshen#Jugon#Yadoran#Dokukurage#Nyorobon

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whether Jeanne (de Penthièvre) acted more as sole or co-ruler in Brittany was the foundational influence on her role during the war, in terms of both the frequency of her administrative activity and where she concentrated her efforts. Moreover, these shifts roughly paralleled major changes in the diplomatic relationships maintained vis-à-vis neighbouring France and England,but Jeanne’s evolving interests in these political contexts have not been adequately recognized by the traditional framework.

First Period

Jeanne, still a young woman, played a relatively restrained role in the first period of the war, being involved in roughly one-quarter of the attested acts. It was during these years that she gave birth to most of her children, which would have further influenced the scope of her participation. Perhaps correspondingly, extant records rarely note Jeanne’s presence outside the ducal city of Jugon, an area relatively removed from the fighting, before 1347. During this time, Charles was very mobile in his pursuit of the war with the support of the French troops, and while doubtless Jeanne accompanied him on occasion, these journeys cannot generally be traced, aside from one joint act issued on 13 June 1342 ‘en noz tentes devant la ville de Hambont [i.e. Hennebont]’. However, as early as May 1342 we have surviving records of Jeanne’s contributions to the duchy’s administration, both alone and with Charles. Among their early charters, some rewarded supporters for their services to the cause, reflecting the intensity of the combat at this stage. Jeanne took an early role in supervising the well-being of various religious institutions in the area, from diverse abbeys to the cathedral of Rennes. The couple also began to manage the viscounty of Limoges from 1343, even though it would not be formally granted to them by Philippe VI until 10 January 1345 and was still part of the dower of Jeanne de Savoie.

Second Period

The first period of wartime administration ended on 20 June 1347 when Charles was captured by the English during his siege of La Roche-Derrien. This opened nine years of negotiations for his freedom, during which Jeanne became the main overseer of governmental activity within Brittany; she appears in just shy of 60 per cent of the attested acts, or more than 70 per cent of the acts pertaining to Brittany and related affairs. The king appointed a series of governors of Charles’ lands during his absence, most notably Philippe des Trois Mons, but at least within the duchy their roles seem to have been restrained. Meanwhile, Jeanne’s acts for this second period show an increased involvement with international political networks, starting with her request for the pope’s aid only a few months after her husband’s capture; these manoeuvres took place while direct French military involvement in Brittany declined and alternative solutions to the conflict with England began to increasingly appeal. This intricate process will be analysed ... as an important example of Jeanne and Charles’ political collaboration, but the core developments and some of their consequences can be outlined here. Jeanne initially entered into negotiations with both Philippe VI and Edward III, mainly via papal intermediaries, and hoped to marry her son to Edward’s daughter, but no real progress was evident for several years. Both she and Charles attended the Anglo-French peace talks at Calais in late 1351, after which negotiations with France reached their high point with the marriage of their daughter to Charles d’Espagne in early 1352; Jeanne and Charles had only concluded temporary truces with England to this point.

On 29 November 1352, however, Jeanne summoned a large assembly of Breton bishops, religious houses, barons, and townsmen to confirm her choice of ambassadors to England for negotiating Charles’ liberation. This was the first meeting of what has been termed the Breton ‘estates’, expanding the normal council advising the prince(s) to include representatives of the towns. Before 1352, Edward III had showed concern for the integrity of the truces he made with Charles and Jeanne by seeking the confirmation not only of the duke and duchess but of the rest of the Breton political community, but this had been purely nominal and not required the towns’ actual participation or ratification. Their involvement here was probably contingent on the expectation that Charles’ freedom would be subject to some degree of ransom: it was expedient for Jeanne to assess and obtain her townsmen’s commitment to such an expense before the negotiations, rather than risk jeopardizing them afterwards through protracted bargaining. Accordingly, the towns summoned here were those on which Jeanne could most rely to underwrite the financial obligation which the treaty would eventually entail.

Although Edward had served as protector to the young Jean de Montfort (now in his early teens), he seemed willing to drop his support of the young prince in an offensive and defensive treaty concluded on 1 March 1353 that set Charles’ ransom at 300,000 écus (£50,000 or 270,000lt). But despite arrangements for the marriage of Margaret of England and Jean de Blois-Penthièvre going ahead at Avignon, Edward finally changed his mind, for obscure reasons. An explanation found in two fourteenth-century chronicles and espoused by La Borderie centred on the supposed massacre by Penthièvre partisans of an English garrison on the Île Tristan, off the lower western coast of the peninsula by Douarnenez, during Charles’ return visit in 1354. D’Argentré and some of the later Breton historians instead blamed ‘the count of Derby, the king’s nephew, who loved the party of the countess [of Montfort] and of the young duke of Brittany’; he, reminding the king forcefully of his prior promises to the Montfortists, brought about the end of the treaty. Pocquet du Haut-Jussé, meanwhile, attributed the failure to the ongoing hesitations of the papal curia in light of French disapproval. The need for royal consent remained a strong theme in papal communications about the marriage paperwork in early 1354, until the assassination of the constable Charles d’Espagne, Jeanne and Charles’ son-in-law.This murder, Pocquet argues, caused any commitment from Jean II for paying Charles’ ransom to evaporate, which finally broke Edward’s own resolve.

Each of these explanations for the treaty’s abandonment presents its difficulties. It is unlikely that Charles would have attacked a relatively insignificant garrison held by his erstwhile ally, and it is unclear why his partisans might have done so, or why such an event could disrupt this important alliance if other causes were not also at play. There is insufficient justification for the opposition of Henry of Lancaster, whom Pope Clement VI (r.1342-52) had engaged for Charles’ cause and who even received a letter of thanks for his efforts. Pocquet du Haut-Jussé’s interpretation has the appeal of drawing on well-established trends in the French monarchy’s reactions to the Breton difficulties, but it does not explain the grant of papal dispensations on 6 May 1353 and 13 May 1354. The best explanation is that, as Anglo-French talks broke apart in 1354 after the (likewise abandoned) Treaty of Guines (6 April), Edward’s decision to desert his protegé appealed less than a more straightforward financial arrangement, particularly when he could continue to receive the incomes from Brittany as tutor to the young Jean, and to use the Breton war as a distraction to the French. Moreover, Mark Ormrod’s suggestion that the king operated throughout the negotiations with ‘calculated duplicity’ may mean that the rupture should not be considered so startling as to need much external explanation. Ultimately Jeanne, Charles, and (again) the Breton assembly formally renounced the plans, and Charles’ liberation came in 1356 only for the enormous sum of 700,000 florines a lescu (£116,667 or 630,000lt).

This phase of Jeanne’s career spanned two of the periods of the war identified by La Borderie, first featuring an upsurge of military activity until 1352, followed by a decade of stagnation. Paralleling the English support of the Montfortist cause, the major fighting took place under French leadership, but Jeanne helped organize the defence and financing of certain towns. But what most characterized the period 1347–56 were the skirmishes of small fighting groups led by captains on both sides operating more-or-less autonomously in hope of profit. If this caused a certain constant level of turmoil, Jeanne’s acts attest her attempt to maintain supervision of routine affairs within the duchy. Her role as sole effective leader of her cause was accompanied by a change in her personal habits. From 1348 to 1351 most of her recorded activity was conducted at Dinan/Léhon rather than Jugon. In the later years of the captivity, she also spent time at Guingamp, especially for the stretch in 1354 when Charles was permitted to return to the duchy (from 30 January); she accompanied him to Saint-Malo on 21 April to see him off.

Third Period

After Charles’ definitive return to the duchy, as during his few short visits before 1356, Jeanne’s role was more modest, perhaps even by choice, than during the long years of her husband’s absence. As in the first period, Jeanne was involved with approximately one-quarter of the surviving acts, most of them directed towards Breton affairs and matters in Limoges. Charles seems to have handled most of the transactions concerning his ransom on his own; this comprised the majority of their international correspondence at this time, and the ruinous arrangements of 1356 overshadowed the rest of the war.136 However, there is clear evidence of their collaboration in matters of government, for which Jeanne had demonstrated her capacity for nine years. Her centre of residence moved to the ducal city of Nantes, where she often lived alongside Charles. It is likely that Jeanne accompanied her husband on some of his visits to northern Brittany across this final period, though she sometimes remained at Nantes when he travelled. Charles also spent some time in Paris attending to the problems caused by King Jean II’s capture at Poitiers in 1356 and the Parisian uprisings under Étienne Marcel in 1357–8. Jeanne probably remained behind to oversee the Breton administration.

Having regained the support of his royal protector,the younger Jean de Montfort was allowed to return to the duchy in 1362, sparking a violent upsurge of activity during the war’s final years. The two armies met at the Landes d’Évran on 24 July 1363, and Charles and Jean drafted a provisional treaty. This called for a partition of the duchy, roughly following the geographic distribution of each side’s supporters: the south and west would go to Jean,including Nantes, and the north and east (with Rennes) to Jeanne and Charles. The reason for the compromise’s failure is unrecorded, though some Montfortist chronicles reported simply that Charles refused it. The only contemporary information about these late negotiations comes from the notarial transcript of the meeting which Charles and Jean held on 24 February 1364 at Poitiers under the aegis of Edward the Black Prince (d.1376), where Charles declared he ‘had not at all come there to respond to the terms proposed by the said lord count’. Why he did so is uncertain, but many accounts in the fourteenth century and later attributed the rupture in negotiations to Jeanne. And it seems impossible that Jeanne was not involved with the decision; it was, after all, her land to dispose of, and she had a clear motive for refusal, since half a duchy would have seemed a richer prospect to the young Jean de Montfort than it did to Jeanne, who had acted as duchess for years. But this did not necessarily make the decision a product purely of personal choice. Even Guillaume de Saint-André, who blamed the Penthièvre side for rejecting the peace of 1363, wrote strongly against the idea of breaking Brittany in two; his protagonist Jean de Montfort asserted that ‘God does not wish that I divide my duchy in any way’. Given the defensiveness of the Breton nobility when regional prerogatives were threatened (as would be demonstrated the following decade), a division might have been untenable.

Fourth Period

So matters came instead to a head at the battle of Auray on 29 September 1364, where Charles was killed. The news reached Jeanne at Nantes, and she immediately made for Angers and her daughter’s family. This brief period in Jeanne’s life is very little documented...but it is worth examining because Auray has been too often treated as a decisive end to the war, when in fact there was no single reason why Charles’ death meant that Jeanne had to surrender the duchy: ‘la bataille ne devait pas suffire à arrêter la guerre de Succession’. It was her inheritance, not Charles’, and she could have remarried. The towns of Jugon, Dinan, and especially Quimper all resisted the Montfortists. For some time after the battle, it was unclear what direction events would take. Froissart reported that Jeanne and Louis d’Anjou initially attempted to collaborate to continue the fight. Pope Urban V (r.1362-70) wrote on 5 November with condolences to Jeanne, but avoided discussing the political fallout of her loss. Even in December, his messenger to her and Jean was instructed to seek at least a truce if lasting peace was not yet possible because of the ‘warlike aggressions and stirrings which make difficult the path of the isaid peace’. But circumstances were against Jeanne. The recent battle had once again been immensely destructive to the ranks of the Breton nobility through both death and capture, leaving Jeanne in a difficult position from which to wage war. She would be better able to bargain protected by the powerful duke of Anjou than at the mercy of her cousin. It may also have been unclear what support she could expect to receive from France. Charles V had ascended the throne only earlier that year and was reluctant to rupture the relative stability existing with England; nor could he afford for the Breton situation to remain a distraction. With her husband gone, Jeanne’s relationship to the French monarchy was less assured, and it was in the king’s interest to maintain the duchy’s allegiance regardless of who was in power. Indeed, by 11 November Charles was already negotiating the possibility of Jean’s homage. It was time for reconciliation.

Prompted by King Charles, Jeanne agreed to talks and, writing from Angers on 11 March 1365, appointed delegates to represent her, chosen from among the ducal councillors (Hugues de Montrelais, bishop of Saint-Brieuc; Jean, lord of Beaumanoir; and Guy de Rochefort, lord of Acérac), along with one of Louis d’Anjou’s men (Guy de Cléder). The result was the first Treaty of Guérande on 12 April. It is often claimed that this treaty reserved Jeanne’s use of the title of duchess of Brittany, which appears in almost all of her subsequent acts, but the treaty granted the ‘name and arms’ of the duchy only to Jean de Montfort. In addition to the territories inherited directly from her parents (Penthièvre, Goëllo, Mayenne, etc.), Jeanne would retain the viscounty of Limoges - now overrun by the English,whom Jean de Montfort was to help remove; and she was exempt from homage to Jean for her lifetime. She was to receive an indemnity of 10,000l each year in compensation for Brittany, 3,000l for her other losses, and half of any aides which Jean raised on her lands. The new duke was to persuade Edward III to release Jeanne’s sons, the eldest of whom was to marry Jean de Montfort’s sister Jeanne. Finally, while the succession of Brittany was no longer to pass through the female line, it was stipulated that should Jean de Montfort die without male heirs, the duchy would revert to those of Jeanne de Penthièvre. These terms left aside entirely the actual legitimacy of the claims to Jean III’s inheritance.

Later life, 1365–1384

After this settlement, Jeanne’s career was far from over, even if it underwent a radical change. Her patterns of residence after Auray until the late 1370s seem to have been entirely unlike those at any phase of the war. Paris became the place where she conducted her most important business, although she spent some time in Angers as well. These arrangements probably relied on her relatives’ hospitality: in 1373, Charles V granted her a house in Paris when, ‘having come to dwell in our bonne ville of Paris, she had no house where she might live’. By contrast, Olivier de Clisson acted as her financial lieutenant in Brittany from at least 1370, though since Jean IV complained in 1372 that Charles V had granted safe conducts for travel within Brittany, including one to Jeanne, she must have returned at least occasionally. These moves reflected her fierce efforts to retain her prerogatives rather than marking any sort of withdrawal from politics, as the Montfortist narrative would have it. After all, her remaining possessions and high connections still placed her among the first ranks of the aristocracy. She seems even to have initially left open the possibility of remarriage, though this was to have no sequel. The last two decades of her life were spent dealing with the fallout from the Treaty of Guérande and the war more generally, albeit with varying degrees of success.

-Erika Graham-Goering, "Princely Power in Late Medieval France: Jeanne de Penthièvre and the War of Breton Succession"

#historicwomendaily#jeanne de penthievre#breton history#war of breton succession#14th century#queue#my post

7 notes

·

View notes