#lantenac

Text

My JP Presentation on Hugo’s Ninety-Three

Where I am currently studying, a JP, or junior project, is a presentation required of undergraduates in the third year. Basically we pick a book (sufficiently haloed) to do what is we call a glorified book report, and then a panel of professors roasts the presenting student with while other students watch and get entertained. Below is my presentation. Unfortunately there is no record of the professor’s questions, but I’ll just say that the one I did not expect was whether Cimourdain’s ethics were more Kantian or Aristotelian (although I did bring up Kant’s categorical imperative at some point earlier in the questioning so I was kind of asking for it). Anyway, I’ve been in love with Ninety-Three ever since I first read it in 2021, and I actually have always intended to write a character analysis on tumblr. So here it is some three years later, and I hope that someone out there will be interested.

Professors, friends, and esteemed guests,

I have the honour to present to you today an unparalleled book: Ninety-Three by Mr. Victor Hugo, whom we all recognise as a giant—not just of French letters, but of the world. To our great shame, although other works by Mr. Hugo are frequently read today, Ninety-Three, his last novel, has been largely forgotten; indeed, at this present moment no reputable publishing company is printing it in the English language.

I am here for the express purpose of reviving Anglophone interest in Ninety-Three. I consider this book a work of French Romanticism par excellence, for several reasons. First, it is an exercise of Hugo's literary theory, set forth as early as 1827 in the Preface to Cromwell, though never until now so perfectly demonstrated; second, in it we see the author’s reflections on a momentous point in history, the French Revolution, itself full of dramatic and philosophical potential. Additionally, the book is well-paced— which is perhaps the most difficult achievement of all for a work of this author. In sum, this book has everything that is required for a novel to ascend to the literary pantheon of the western canon: it has drama; it has depth; it is entertaining; it is true. Let us hasten, then, to place it where it deserves to be.

To understand the genius of Ninety-Three, one must understand the symbolic significance of its characters. But before I go any further, let us provide a general idea of the plot. In one sentence, it is a tale of the struggle between republicans and royalists in the Vendée (that is, Brittany), during the height of the Reign of Terror—hence the name, which is short for Seventeen Ninety-Three. Hugo divides the novel into three parts: At Sea, In Paris, and In la Vendée.

The story begins with a sort of prologue, an encounter between the republican Battalion of the Bonnet-Rouge and a Briton peasant woman and her three children, who are fleeing the war. They are quickly adopted by the battalion. We shall soon see why they are important. For the present our attention is redirected to the island of Jersey, an English possession, where a French royalist crew is preparing for a secret expedition. An old man boards the ship. He is in peasant dress, but by his demeanor seems to be an aristocrat. In the rest of At Sea we become acquainted with this jolly royalist crew—only to see them all perish in a naval battle before they ever reach the coast of France. Yet the old man escapes with the sailor Halmalo, and they land in Brittany in a little rowboat. He sends Halmalo off to rouse a general insurrection. Then, upon reading a placard, learns that his presence in Brittany has been known, and that someone named Gauvain is hunting him down, which sends him into a shock. Despite his dire situation, our protagonist is recognised by an old beggar named Tellemarch, who conceals him. We discover that he is none other than the Marquis de Lantenac, Prince in Brittany, coming back to lead the rebellion.

In the second part, In Paris, we are introduced to another character: Cimourdain. Cimourdain is a revolutionary priest, a man of iron will, with one weakness only: his affection for a pupil he had long ago, who was the grand-nephew of a great lord. At this period, however, Cimourdain dedicated himself completely to the revolution. Such was his formidable reputation that Cimourdain was able to intrude upon a meeting of the three terrible revolutionary men, Danton, Marat, and Robespierre, and cause his opinion to prevail among them. Robespierre then appoints Cimourdain as a delegate of the Committee of Public Safety, and sends him off to deal with the situation in Vendée. He is told that his mission is to watch a young commander, a ci-devant noble, named Gauvain. This name also sends Cimourdain into a shock.

Gauvain, in fact, is none other than the grand-nephew of the Marquis de Lantenac, in whose household the priest Cimourdain had been employed. Although they have not met for many years, there is a close bond between the master and pupil, and both adhere to the same revolutionary ideal. Hugo has set the stage. In the last part, In la Vendée, these epic forces are hurled against each other in the siege of the Gauvain family’s ancestral castle, La Tourgue. On the one side, we have the republican besiegers, Gauvain and Cimourdain, and on the other, the Marquis de Lantenac and his Briton warriors, the besieged. The Marquis has one last card to play: he has, as hostages, the children of the Battalion of the Bonnet-Rouge. For the safety of his party, he offers the life of the three children, whom he has placed in the chatelet adjoining the castle of La Tourgue, which will be burned upon attack. The republicans refuse. The siege begins, bloody for the republicans, hopeless for the royalists. At the last moment, by a stroke of fate the royalists contrive to escape, leaving behind an exasperated republican army, and a burning house. The republicans try to rescue the children, but find this impossible, as they can neither scale the walls of the chatelet, nor open the iron door that leads to it. As this is happening, the Marquis hears the desperate cries of the mother in the distance. Beyond all expectation, he returns, opens the door with his key, steps into the fire, and saves the children. Thereupon he is seized by Cimourdain, who proclaims that Lantenac will be promptly guillotined. Yet unbeknownst to Cimourdain, Lantenac’s heroic act of self-sacrifice set off a crisis of conscience in the gentle Gauvain, who fought for the republic of mercy, not the republic of vengeance. The final battle takes place in the human heart.

I will not divulge the ending. Already we can see that these characters are at once human, and more than human. “The stage is an optical point,” says Hugo in the Preface to Cromwell, “Everything that exists in the world—in history, in life, in man—should be and can be reflected therein, but under the magic wand of art.” Men assume gigantic proportions. They become ideas. The three central characters each represent a force. In the lights and shadows of their souls, we have symbols of the lights and shadows of a whole age. The fifteen centuries of feudalism, the Bourbon monarchy, the France of the past, when condensed into an object is the looming castle La Tourgue, and when incarnate is Lantenac. The twelve months of the revolutionary terror, the Committee of Public Safety, the France of the moment, is as an object the guillotine, as a man Cimoudain. The immense future is Gauvain. Lantenac is old; Cimourdain middle-aged; Gauvain young.

Let us look at each of these characters in turn.

I admit that Lantenac is my favourite character. In his human aspect he is impressive, and very compellingly written. Almost immediately upon introduction, he manifests a ferocious justice in the affair of Halmalo’s brother, a gunner who endangered the whole ship by his neglect, and who saved it in a terrifying struggle between vis et vir, between an invincible brass carronade and frail humanity. Lantenac awarded this man the Cross of Saint-Louis, and then had him shot. To the vengeful Halmalo, his justification is this: “As for me, I did my duty, first in saving your brother’s life, and then in taking it from him [...] He has failed his duty; I have not failed mine.” This episode sums up Lantenac’s character. True to life and true to the principle of romantic drama, Lantenac contains both the grotesque and the sublime, sometimes even in the same action. Like the Cromwell that inspired in posterity such horror and admiration, he shoots women, but saves children. He martyrs others, but is at every point prepared to be the martyr.

As an idea he is the ultimate embodiment of the Ancien Régime. Though himself unpretentious, Lantenac is perfectly aware of the role he must play. He demonstrates perfectly, unlike conventional aristocrats in literature, the principle of noblesse oblige and the justice of the suum cuique. He believes that he is the representative of divine right, not out of arrogance, but as a matter of fact. “This is the question,” he tells Gauvain in their first and last interview, “to be a Great Kingdom, to be the ancient France, [is] to be this magnificent land of system [...] There was something fine and noble in this system. You have destroyed it [...] like the miserable ignoramuses you are [...] Go! Do your work! Be the new man! Become pygmies! [...] But leave us great.” The force which animates Lantenac is his duty, merciless, towards the old monarchical order—until the principle was overcome by the man, who was still able to be moved by helpless innocence.

The first thing that Hugo felt it was necessary to know about Cimourdain is that he is a priest. “He had been a priest, which is a solemn thing. Man may have, like the sky, a dark and impenetrable serenity; that something should have caused the night to fall in his soul is all that is required. [...] Cimourdain was full of virtues and truth, but they shine out against a dark background.” There is an admirable purity about him: it is symbolic that we always see him rushing into the thick of battle, but never firing his weapon. He aids the poor, relieves the suffering, dresses the wounded. By his virtues he seems Christlike, but unlike Christ, his is an icy virtue, the virtue of duty, not love; a justice which knows not mercy—“the blind certainty of an arrow,” which imparts to this sublimity a touch of the ridiculous. It is a short step from greatness to madness. Still, there remains some humanity in Cimourdain, on account of his love for Gauvain. Through this love that he is able to live, as a man, and not merely as the mechanical execution of an idea.

On the surface Cimourdain has renounced his priesthood. But, Hugo reminds us, “once a priest, always a priest.” He is still a priest, but a priest of the Revolution, which he believes to have come from God. There is a similarity between Cimourdain and Lantenac, though they are on the two diametrically opposed sides of the revolution. Both are bound by duty to their cause. Both are ferocious. When Robespierre commissioned Cimourdain, he answered: “Yes, I accept. Terror against terror, Lantenac is cruel. I shall be cruel. War to the death against this man. I will deliver the Republic from him, so it please God." Quite appropriately he is represented by the image of the axe—realised in the guillotine erected in the final chapter. As with Lantenac, the Cimourdain of relentless revolutionary justice eventually finds himself face to face with the human Cimourdain, the spiritual father of Gauvain, the embodiment of mercy.

Gauvain at a glance seems to be a character of simple conception: his defining characteristic is an almost angelic goodness. He is also the pivotal point in the story: on one hand, he is the son of Cimourdain, a republican, and on the other, he is the son of the Gauvain family, Lantenac’s heir. Through him, we are reminded that the Vendée is a fratricidal war. Allusions abound in the novel, for example, when Cimourdain declared his brotherhood with the royalist resistors, a voice, implied to be Lantenac’s, answered, “Yes, Cain.” Gauvain finds himself caught in the middle of such a frightful war. At first, he was able to overlook his kinship with Lantenac, on account of the older man’s monstrosities, but with Lantenac redeemed by his self-sacrifice, it becomes impossible to ignore his threefold obligation: to family, to nation, and to humanity. It is because of this that duty, which seemed so plain to Cimourdain, rose “complex, varied, and tortuous” before Gauvain. The fact is, far from being simple, Gauvain's goodness is neither effortless nor plain, and we are reminded that the most colossal battles of nobility against complacency often happen in the most sensitive of consciences.

Indeed, the triumph of Gauvain is a triumph of the moral conscience, the light which is said to come from the great Unknown, over the dismal times of revolution and internecine strife, “in the midst of the conflagration of all enmity and all vengeance, [...] at that instant [...] when everything becomes a projectile [...], when [...] justice, honesty, and truth are lost sight of [...]” To Hugo, the Revolution is a tempest, in the midst of which we find its tragic actors, forbidding figures as Cimourdain, Lantenac, and the delegates of the Convention, some supremely sublime, some utterly grotesque, and many both: “a pile of heroes, a herd of cowards.” But, at the same time, “The eternal serenity does not suffer from these north winds. Above Revolutions, Truth and Justice reign, as the starry heavens above the tempest.” Gauvain finally comes to peace with this realisation, and we hear him saying, “Moreover, what is the tempest to me, if I have the compass? And what difference can events make to me, if I have my conscience?”

But Ninety-Three is, after all, a tragic book. We might ask whether it is not the case that Gauvain is too much of an idealist. He wishes to found a Republic of Intellect, where perpetual peace eliminates all war, and where man, having passed through the instruction of family, master, country, and humanity, finally arrives at God. “Gauvain, come back to earth,” says Cimourdain. To this Gauvain cannot make a reply. He can only point us upwards, by self-denial, and by his love, towards the ideal.

And the task of the novel is no more than this, this reminder of the reality of life. The drama was created, as the Preface to Cromwell declares, “On the day when Christianity said to man: ‘Thou art [...] made up of two beings, one perishable, the other immortal, [...] one enslaved by appetites, cravings and passions, the other borne aloft on the wings of enthusiasm and reverie—in a word, the one always stooping toward the earth, its mother, the other always darting up toward heaven, its fatherland.’” And did not Ninety-Three achieve this? The legend of La Vendée, like the stage, takes crude history and distills from it reality. Let us conclude with this passage from the novel itself:

“Still, history and legend have the same end, depicting [the] man eternal in the man of the passing moment.”

#victor hugo#ninety-three#quatrevingt-treize#1793#reign of terror#vendée#romanticism#essay#lantenac#gauvain#cimourdain#in an earlier draft I also compared Gauvain to Alyosha Karamazov in a passing comment but I had to take that out for the sake of time#also Cimourdain is definitely a Kantian but doesn’t seem that Hugo approves of Kantian ethics#on the other hand Hugo isn’t Aristotelian either#because in his works reason and the passions are always diametrically opposed#whereas Aristotle / St Thomas would have said that the passions could be trained by reason

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albert Sans - La niebla.

La niebla.

Había sido humo sólo. El hombre había sido por él envuelto y por el breve viento frío. Pero fue la niebla sólo. Sin memoria en ella el espanto y el cuchillo y la sangre.

——

© Protegido.

View On WordPress

#Albert#Albert Sans#Andante moderato#Cerrado#Corpus en exégesis trina#Hostil#Humedad y orín#Imaginen#Joaquín#Joaquín Plana#Lantenac#Los faros iluminaban#Narración#Narración del tiempo#Narraciones breves#Narrativa#Niebla#Plana#Sans#Torturadero#Una tragedia de Sófocles

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

93 (Quatre vingt treize, QVT) liveblogging or whatever it’s called

I hate Victor Hugo for all the damage he has done to my brain

SO MANY SPOILERS (including Les Mis) BECAUSE HAHA I WENT IN KNOWING MY HEART IS GOING TO BE SHREDDED INTO PIECES

The first part covers the first 1/3 of the book

The loose cannon! It’s a beautifully written part, I love how the theme of the book is being introduced. How does a creature battle the inorganic? How do men fight the unknown? Not just the peculiar individuals but also our irrational urges and the tides of time.

The foreshadowing is also there: the gunner is rewarded for his heroics, and executed for his faults. We shall see how this theme is presented again and rediscussed in the latter parts of the book.

I really love the loose cannon concept so much, can you tell? It’s something so deeply grounded in human nature, an universal struggle that traverses time. In this theater called life, we may become simultaneously the cannon, the gunner, and the judge. What are the limits of the organic and the inorganic? What are the limits within our actions? A balance is needed, but difficult is it to reach.

The confrontation between Lantenac and Halmalo is a good demonstration of the norms of the late 18C! It is so important to remember that the whole idea of a Republic, the abolishment of monarchy, was radical in the late 18C. Halmalo also builds up the village massacre that is about to happen a few chapters later.

THE BEGGAR GUY. He too, is a loose cannon. As soon as he saves Lantenac, Hugo explains that this man cares little of the politics of the world, which while is similar to Michelle, is even more akin to Mabeuf.

Both the Beggar and Mabeuf focuses on the natural world, and display a negligence towards the infighting of men. Both are then mercilessly affected by the politics they have chosen to withdraw from. It is clear that Hugo believes that politics is an inevitable matter as long as one belongs to the human race. The Beggar, who is even more isolated from the earthly desires than Mabeuf, cannot escape the fate that by saving Lantenac he has doomed hundreds of people. His choice of saving Lantenac was the loosening of the cannon, and upon his arrival of the village he becomes the gunner confronting the wrecked ship.

(Also the parallel between the Beggar and Lantenac: both believe they are doing the Right thing that leaves corpses in their wake.)

The similarities Cimourdain and Enjolras shares. Both are priests of the Revolution, “Enjolras was a charming young man capable of being terrible” and “he must be either infamous or sublime”. LM displays how Hugo sees the revolution and human progress: it is sublime. 93 shows how the idea that ‘restriction must exist within revolution’ is reinforced is his mind after the Paris Commune. Enjolras claims himself a doomed man after the execution of Le Cabuc (boy is that scene erotic), and Cimourdain would doom himself as he condemns Gauvain.

I have mental damage from the introduction of Gauvain’s relationship to Cimourdain. The chapter title, ‘a corner not dipped into the Styx’, is yet another foreshadowing of what is to become of Gauvain. Victor is so good at this, giving subtle hints that will beat the living shit out of reader’s heart as we march towards the end. Are u ok V Hughes? Who has hurt you so deeply?

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Limits of the Inexorable: Ninety-Three, Loose Cannons, and Happy Endings by Katherin Nehring and Maya Chhabra

At the end of Victor Hugo’s final novel, Ninety-Three, two of our three main characters are dead, the revolution has suffered a setback in the Vendée, and tragedy seems everywhere. This lecture interprets the ending as positive in light of an alternate title Hugo considered–Les Inexorables–using the dramatic set-piece of the loose cannon aboard a ship as an interpretive key. With each major character symbolizing a different temporal moment–Lantenac the feudal past, Gauvain the egalitarian future, and Cimourdain the crucial revolutionary moment of 93 itself–we discuss how Gauvain’s actions lead directly to Cimourdain’s self-chosen death, symbolizing both the necessary end of the state of emergency that the Terror and the year 1793 represent, and an avoidance by both characters of the Napoleonic temptation that ended the French Revolution. The loose cannon is brought under control. To modify Robespierre’s comment on Louis XVI: in Hugo’ symbolic universe, 93 must die so that the future can live.

Make sure to get your tickets before the 12th July deadline!

Scholarships covering the complete cost of admission are still available - just email [email protected] to request one!

If you’re interested in volunteering as a discord or zoom moderator for the con, please fill out this form and join our planning discord.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

rereading 1793

#me.txt#Have not finished this round I used to read it when I was 13 because I was in love with Cimourdain though so. Yeah.#I was jokingly gonna make a political compass like javert authoritarian right cimourdain authoritarian left etc#But then I was making lantenac like libertarian right and valjean lib left and went hang on Aint Valjean a Bonapartist... INSANITY...#I keep imagining the dinner table like Gillenormand for the king and Marius like lawl can you believe I used to be a bonapartist:) ? ha#and Valjeans like... oh the emperor? Word? god bless. and the dinner table is like Death silent like truly nightmareish.#Myriel when he hears Valjean is a bonapartist like Aite im gonna need that silver b#**edit like i dont in my heart of hearts think hes diehard its prolly jst he doesnt think about it+is from the north#but it is so fucking funny to Me.

57 notes

·

View notes

Note

10? XD

characters that deserved worse? >:]

Thenardier, Mme Thenardier, GILLENORMAND, Tholomyes, Bamatabois , fricking Lantenac if we’re branching out here a little

I’m not saying they all deserve to be eaten by rhinos but I’m also not saying a rhino shouldn’t step on their feet some

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

I still cannot believe almost nobody knows the novel "Ninety-three" by Victor Hugo. Like... HOW?

It's the most beautifully written novel ever, it's pretty much as good as Les Mis, it has the same amount of pathos, it's WAY shorter than the Brick (so you can bring it with you more easily – this is a really good point)... And still barely anybody has read it?

My heart breaks every time I think about the fact that this awesome novel, which touches so many modern topics like freedom, equality and education (and so much more), is ignored by so many...

+ the characters. my gosh. Gauvain, Cimourdain, Radoub, Michelle Fléchard with her precious kids... Each character is SO well developed that I could talk about them (except Lantenac because I hate him with all my heart) for an entire week or more

#literature#french literature#france#victor hugo#ninety three#les mis#les miserables#les miz#french#novel#bookish#book#classic#classic literature

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

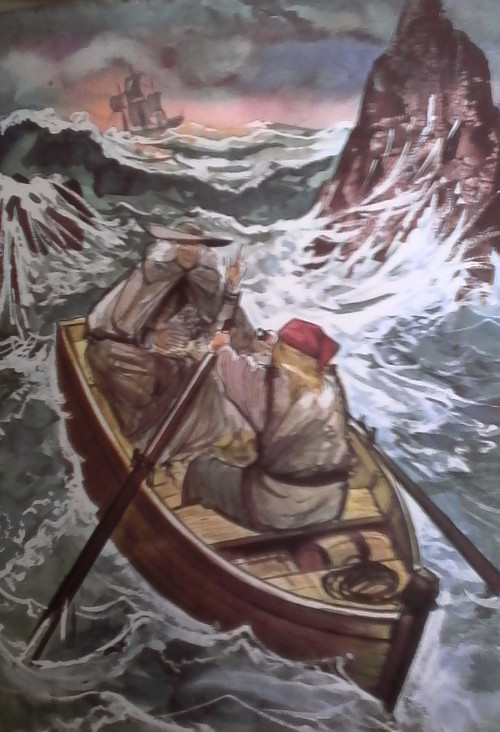

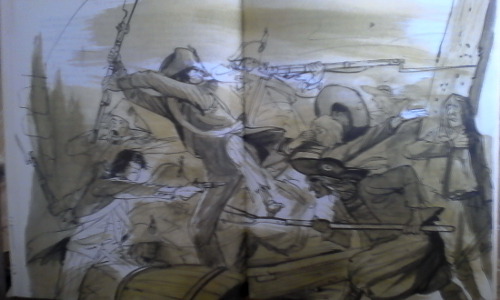

I have found an illustrated version of Quatrevingt-treize, for children, and I really love the pictures!

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hugo Victor - Quatrevingt-treize

Hugo Victor - Quatrevingt-treize : Initialement prévu pour une trilogie qui aurait compris, outre L'homme qui rit, roman consacré à l'aristocratie, un volume sur la monarchie, Quatrevingt-Treize, écrit à Guernesey de décembre 1872 à juin 1873, après l'échec de Hugo aux élections de janvier 1872, achève la réflexion de l'écrivain sur la Révolution à la lumière de la Commune et tente de répondre à ces questions: à quelles conditions une révolution peut-elle créer un nouvel ordre des choses? 1793 était-il, est-il toujours nécessaire? (présent. partenaire ELG)

Le roman valut à son auteur la haine des conservateurs. En mai 1793, le marquis de Lantenac, âme de l'insurrection vendéenne, arrive en Bretagne sur la Claymore, une corvette anglaise. À bord, il n'a pas hésité à décorer puis à faire exécuter un matelot qui n'avait pas arrimé assez solidement un canon. La consigne du marquis est claire: il faut tout mettre à feu et à sang. D'horribles combats s'ensuivent. Lantenac massacre des Bleus et capture trois enfants...

PDF, HTML : Édition partenaire Ebooks Libres et gratuits

ePUB, PDF (Petits Écrans), Kindle-Mobi, DOC/ODT : Édition Bibliothèque numérique romande (basée sur l'édition ELG)

Téléchargements : ePUB - PDF - PDF (Petits Écrans) - Kindle-MOBI - HTML - DOC/ODT

Read the full article

0 notes

Link

Te gusta leer?..Te comparto: Libros gratis @ espanol.Free-eBooks.net

0 notes

Text

Escítala - Nueva publicación en la serie Imaginen …

Escítala, nueva publicación en la serie Imaginen …

Escítala contiene los textos numerados CVI-CXX en este blog.

Descarga segura y gratuita.

View On WordPress

#Colegio#Cueva de Ilotas Exánimes#Educación#Empresa#Escítala#Excelencia#Extenuación por la Implacable Sosa#Fascismo#Franquismo#Hecatónquiros#Hostium#Imaginen#Invidia#Joaquín#Joaquín Plana#La piedra de Heráclea#Lantenac#Naves#Panamá#Plana#Privado#purdah#Siste#Torturadero#Viator

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ninety-Three

The year is 1793. The French Revolution is at its bloodiest, under attack from within by Royalists and from without by foreign armies. If England successfully lands its army in France, the Republic is likely doomed. Ninety-Three is the story of the Marquis de Lantenac, an exiled French nobleman snuck back into France to raise a Royalist army which will make the English invasion possible, Gauvain,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

George C. de Lantenac – Un barco en un jardín. — Joaquín Plana

George C. de Lantenac – Un barco en un jardín. — Joaquín Plana

Un barco en un jardín. Las instituciones sustentadas con capital privado que rechazan una evalución externa de la organización de sus programas se mienten objetividad en la subjetividad retroalimentada que llama libertad a lo arbitrario no contrastado. Es un estado absoluto cuyo principio es una oposición en la forma de una negación de verosimilitud a […]

George C. de Lantenac – Un barco en un…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Rogue One on Netflix

Most of the stuff I didn’t get into the first time (jumpy intros, lots of war stuff towards the end) wasn’t engaging this time either, but a few vague thoughts:

-more Tivik (/Cassian) fic!

-Saw Gerrera’s dudes playing dice games was striking. I get that it’s the equivalent of the rushed cantina scene, but they don’t seem all that extremist to me, more just “dudes hanging around the rebel base.”

-Saw is kind of a Cimourdain type figure? “All-out fighter who goes so far in his zeal for progress he starts to look like his adversaries, but the only person he has a real relationship with is the young relative of the ‘bad guys’”? Of course Galen isn’t Lantenac, but...

-The idea of Galen “learning to lie” as a strategy is weird. Usually I feel like the world is divided into “people who have poker faces” and “people who just don’t.” So him being able to consciously pick it up as a skill feels interesting.

-The Citadel Tower and all its information seems like a cracky Game of Thrones crossover waiting to happen (I say after watching all of two episodes, heh).

-[indistinct chatter] this really feels like it was setting up for the council leading the way for a full-scale attack on Scarif then and there, trope-wise

0 notes

Text

Lesser Animation Studios Present: Works Based on The Reading about a Wiki Page Inspired by a Rumor of VICTOR HUGO’S LESS FAMOUS (to English speaking audiences) NOVELS:

amarguerite replied to your post “stalinistqueens replied to your post: ...”

what about han of iceland? the hero already had an Animal Companion! Just imagine all the stuffed polar bears Disney could have sold!

okay let’s do this let’s go

Hans of Iceland: a jolly singing dwarf and his polar bear friend lend a hand in a young romance!! No one will forget the jaunty musical number “ A Drink By The Sea”!

Toilers of the Sea: the plucky young orphan Gilliat sets out on the sea to prove his worth to the girl of his dreams! But with the help of a lonely octopus friend and some friendly seabirds, can he prove his worth to...himself??

Ninety Three: Armed only with cutesy malapropisms and the power of song, can the three adorable Fletcher (not a typo, that’s the name on all the merch) children manage to find their way back to their mother and the entertainingly bumbling Bonnet Rouge troop, while helping handsome Captain Gauvain bridge the generation gap with his grumpy Uncle Lantenac--and maybe help their mother find new romance in the bargain? The answer will surprise you, especially if you expect a story that follows the novel in any way! The duet between CHOPin�� the Guillotine (GET IT) and Lala Torgue will stick in your brain for days, no matter what you do to erase your memory!

The Man Who Laughs: A travelling circus show brings the literal magic of laughter back to a court full of sad rich people cursed by The Evil Duchess! The ending, in which Gwynplaine learns his noble lineage and marries Dea, recovering his ancestral lands from The Evil Duchess and ensuring that these particular poor people are just fine, will have audiences dismissing issues of social injustice for days to the award-not-winning tune “It’s just a Just World After All”!

Bug Jargal: a heartwarming story of friendship between a dog with a limp and a crocodile! NOTHING ELSE HAPPENS AT ALL.

#amarguerite#talking to people through replies what#adapation talk#I'm a bad person and I should feel bad#Bad Les Mis Adaptations

33 notes

·

View notes