#quatrevingt-treize

Note

Top 5 literary works written before the 21th century

I'll answer with my faves so this is highly subjective of course:

Les Miserables because I would have been someone else if I hadn't read that book at 14

The Great Gatsby because we stan delusional men with a pretty smile trying to repeat the past

Le Cousin Pons because old gay neurodivergent artists doomed by the narrative

For Whom the Bell Tolls because I need a room full of health care specialists before even attempting to talk about that book

Ninety-three (Hugo) because I cried for a week after finishing it

#i have never seriously delved into my jay gatsby brainrot on this blog#you have no idea how far I can go#also i'm not including greek literature here#classical or modern#that would take all five tbh#anonymous#ask game#top 5 ask game#les miserables#the great gatsby#le cousin pons#for whom the bell tolls#ninety three#quatrevingt-treize

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

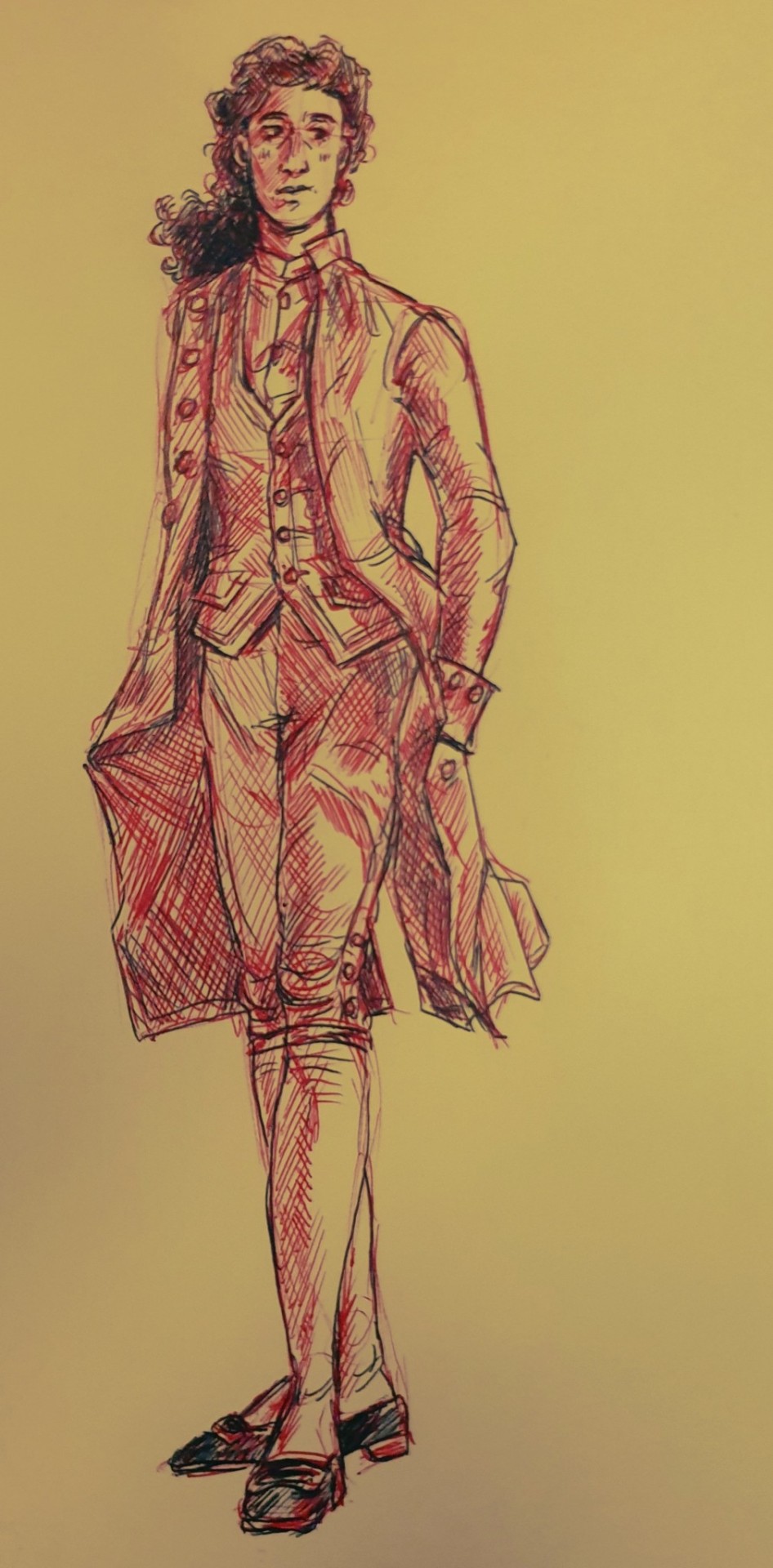

Haven't put pen to paper in a while.

#My art#93#Quatrevingt-treize#QVT#Gauvain#Quite literally pen and paper. I have no other art supplies on hand.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

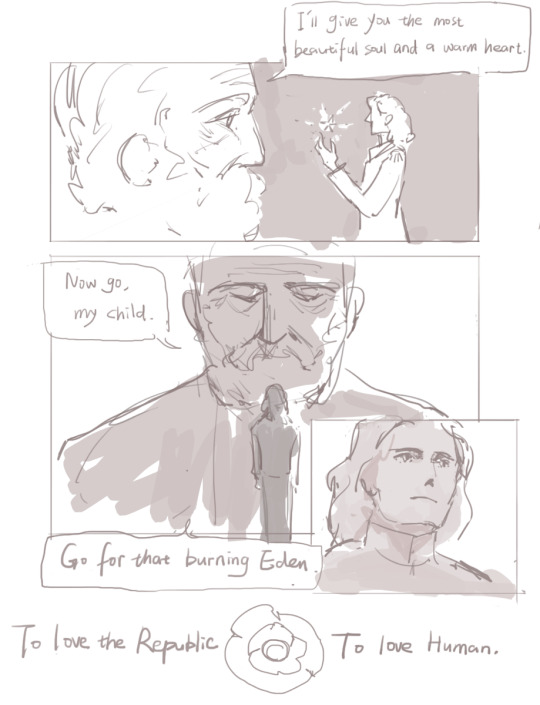

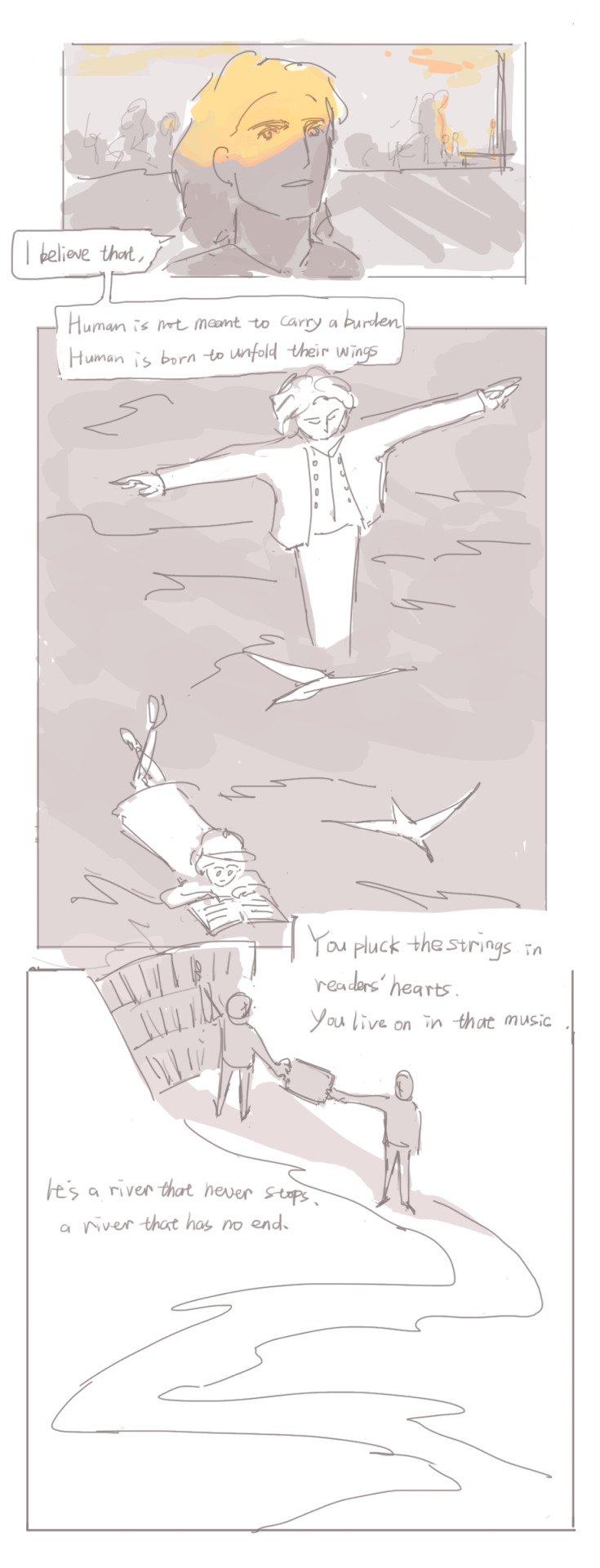

I love Victor Hugo's novel "Quatrevingt-treize" soooooooooooo much that i have to draw this. This is the greatest novel i've read so far. when i came to the last few pages of the book, it felt like a star exploding and burning in my head.

English is not my first language, so i hope it's not too difficult to read. Hope you enjoy!!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

My JP Presentation on Hugo’s Ninety-Three

Where I am currently studying, a JP, or junior project, is a presentation required of undergraduates in the third year. Basically we pick a book (sufficiently haloed) to do what is we call a glorified book report, and then a panel of professors roasts the presenting student with while other students watch and get entertained. Below is my presentation. Unfortunately there is no record of the professor’s questions, but I’ll just say that the one I did not expect was whether Cimourdain’s ethics were more Kantian or Aristotelian (although I did bring up Kant’s categorical imperative at some point earlier in the questioning so I was kind of asking for it). Anyway, I’ve been in love with Ninety-Three ever since I first read it in 2021, and I actually have always intended to write a character analysis on tumblr. So here it is some three years later, and I hope that someone out there will be interested.

Professors, friends, and esteemed guests,

I have the honour to present to you today an unparalleled book: Ninety-Three by Mr. Victor Hugo, whom we all recognise as a giant—not just of French letters, but of the world. To our great shame, although other works by Mr. Hugo are frequently read today, Ninety-Three, his last novel, has been largely forgotten; indeed, at this present moment no reputable publishing company is printing it in the English language.

I am here for the express purpose of reviving Anglophone interest in Ninety-Three. I consider this book a work of French Romanticism par excellence, for several reasons. First, it is an exercise of Hugo's literary theory, set forth as early as 1827 in the Preface to Cromwell, though never until now so perfectly demonstrated; second, in it we see the author’s reflections on a momentous point in history, the French Revolution, itself full of dramatic and philosophical potential. Additionally, the book is well-paced— which is perhaps the most difficult achievement of all for a work of this author. In sum, this book has everything that is required for a novel to ascend to the literary pantheon of the western canon: it has drama; it has depth; it is entertaining; it is true. Let us hasten, then, to place it where it deserves to be.

To understand the genius of Ninety-Three, one must understand the symbolic significance of its characters. But before I go any further, let us provide a general idea of the plot. In one sentence, it is a tale of the struggle between republicans and royalists in the Vendée (that is, Brittany), during the height of the Reign of Terror—hence the name, which is short for Seventeen Ninety-Three. Hugo divides the novel into three parts: At Sea, In Paris, and In la Vendée.

The story begins with a sort of prologue, an encounter between the republican Battalion of the Bonnet-Rouge and a Briton peasant woman and her three children, who are fleeing the war. They are quickly adopted by the battalion. We shall soon see why they are important. For the present our attention is redirected to the island of Jersey, an English possession, where a French royalist crew is preparing for a secret expedition. An old man boards the ship. He is in peasant dress, but by his demeanor seems to be an aristocrat. In the rest of At Sea we become acquainted with this jolly royalist crew—only to see them all perish in a naval battle before they ever reach the coast of France. Yet the old man escapes with the sailor Halmalo, and they land in Brittany in a little rowboat. He sends Halmalo off to rouse a general insurrection. Then, upon reading a placard, learns that his presence in Brittany has been known, and that someone named Gauvain is hunting him down, which sends him into a shock. Despite his dire situation, our protagonist is recognised by an old beggar named Tellemarch, who conceals him. We discover that he is none other than the Marquis de Lantenac, Prince in Brittany, coming back to lead the rebellion.

In the second part, In Paris, we are introduced to another character: Cimourdain. Cimourdain is a revolutionary priest, a man of iron will, with one weakness only: his affection for a pupil he had long ago, who was the grand-nephew of a great lord. At this period, however, Cimourdain dedicated himself completely to the revolution. Such was his formidable reputation that Cimourdain was able to intrude upon a meeting of the three terrible revolutionary men, Danton, Marat, and Robespierre, and cause his opinion to prevail among them. Robespierre then appoints Cimourdain as a delegate of the Committee of Public Safety, and sends him off to deal with the situation in Vendée. He is told that his mission is to watch a young commander, a ci-devant noble, named Gauvain. This name also sends Cimourdain into a shock.

Gauvain, in fact, is none other than the grand-nephew of the Marquis de Lantenac, in whose household the priest Cimourdain had been employed. Although they have not met for many years, there is a close bond between the master and pupil, and both adhere to the same revolutionary ideal. Hugo has set the stage. In the last part, In la Vendée, these epic forces are hurled against each other in the siege of the Gauvain family’s ancestral castle, La Tourgue. On the one side, we have the republican besiegers, Gauvain and Cimourdain, and on the other, the Marquis de Lantenac and his Briton warriors, the besieged. The Marquis has one last card to play: he has, as hostages, the children of the Battalion of the Bonnet-Rouge. For the safety of his party, he offers the life of the three children, whom he has placed in the chatelet adjoining the castle of La Tourgue, which will be burned upon attack. The republicans refuse. The siege begins, bloody for the republicans, hopeless for the royalists. At the last moment, by a stroke of fate the royalists contrive to escape, leaving behind an exasperated republican army, and a burning house. The republicans try to rescue the children, but find this impossible, as they can neither scale the walls of the chatelet, nor open the iron door that leads to it. As this is happening, the Marquis hears the desperate cries of the mother in the distance. Beyond all expectation, he returns, opens the door with his key, steps into the fire, and saves the children. Thereupon he is seized by Cimourdain, who proclaims that Lantenac will be promptly guillotined. Yet unbeknownst to Cimourdain, Lantenac’s heroic act of self-sacrifice set off a crisis of conscience in the gentle Gauvain, who fought for the republic of mercy, not the republic of vengeance. The final battle takes place in the human heart.

I will not divulge the ending. Already we can see that these characters are at once human, and more than human. “The stage is an optical point,” says Hugo in the Preface to Cromwell, “Everything that exists in the world—in history, in life, in man—should be and can be reflected therein, but under the magic wand of art.” Men assume gigantic proportions. They become ideas. The three central characters each represent a force. In the lights and shadows of their souls, we have symbols of the lights and shadows of a whole age. The fifteen centuries of feudalism, the Bourbon monarchy, the France of the past, when condensed into an object is the looming castle La Tourgue, and when incarnate is Lantenac. The twelve months of the revolutionary terror, the Committee of Public Safety, the France of the moment, is as an object the guillotine, as a man Cimoudain. The immense future is Gauvain. Lantenac is old; Cimourdain middle-aged; Gauvain young.

Let us look at each of these characters in turn.

I admit that Lantenac is my favourite character. In his human aspect he is impressive, and very compellingly written. Almost immediately upon introduction, he manifests a ferocious justice in the affair of Halmalo’s brother, a gunner who endangered the whole ship by his neglect, and who saved it in a terrifying struggle between vis et vir, between an invincible brass carronade and frail humanity. Lantenac awarded this man the Cross of Saint-Louis, and then had him shot. To the vengeful Halmalo, his justification is this: “As for me, I did my duty, first in saving your brother’s life, and then in taking it from him [...] He has failed his duty; I have not failed mine.” This episode sums up Lantenac’s character. True to life and true to the principle of romantic drama, Lantenac contains both the grotesque and the sublime, sometimes even in the same action. Like the Cromwell that inspired in posterity such horror and admiration, he shoots women, but saves children. He martyrs others, but is at every point prepared to be the martyr.

As an idea he is the ultimate embodiment of the Ancien Régime. Though himself unpretentious, Lantenac is perfectly aware of the role he must play. He demonstrates perfectly, unlike conventional aristocrats in literature, the principle of noblesse oblige and the justice of the suum cuique. He believes that he is the representative of divine right, not out of arrogance, but as a matter of fact. “This is the question,” he tells Gauvain in their first and last interview, “to be a Great Kingdom, to be the ancient France, [is] to be this magnificent land of system [...] There was something fine and noble in this system. You have destroyed it [...] like the miserable ignoramuses you are [...] Go! Do your work! Be the new man! Become pygmies! [...] But leave us great.” The force which animates Lantenac is his duty, merciless, towards the old monarchical order—until the principle was overcome by the man, who was still able to be moved by helpless innocence.

The first thing that Hugo felt it was necessary to know about Cimourdain is that he is a priest. “He had been a priest, which is a solemn thing. Man may have, like the sky, a dark and impenetrable serenity; that something should have caused the night to fall in his soul is all that is required. [...] Cimourdain was full of virtues and truth, but they shine out against a dark background.” There is an admirable purity about him: it is symbolic that we always see him rushing into the thick of battle, but never firing his weapon. He aids the poor, relieves the suffering, dresses the wounded. By his virtues he seems Christlike, but unlike Christ, his is an icy virtue, the virtue of duty, not love; a justice which knows not mercy—“the blind certainty of an arrow,” which imparts to this sublimity a touch of the ridiculous. It is a short step from greatness to madness. Still, there remains some humanity in Cimourdain, on account of his love for Gauvain. Through this love that he is able to live, as a man, and not merely as the mechanical execution of an idea.

On the surface Cimourdain has renounced his priesthood. But, Hugo reminds us, “once a priest, always a priest.” He is still a priest, but a priest of the Revolution, which he believes to have come from God. There is a similarity between Cimourdain and Lantenac, though they are on the two diametrically opposed sides of the revolution. Both are bound by duty to their cause. Both are ferocious. When Robespierre commissioned Cimourdain, he answered: “Yes, I accept. Terror against terror, Lantenac is cruel. I shall be cruel. War to the death against this man. I will deliver the Republic from him, so it please God." Quite appropriately he is represented by the image of the axe—realised in the guillotine erected in the final chapter. As with Lantenac, the Cimourdain of relentless revolutionary justice eventually finds himself face to face with the human Cimourdain, the spiritual father of Gauvain, the embodiment of mercy.

Gauvain at a glance seems to be a character of simple conception: his defining characteristic is an almost angelic goodness. He is also the pivotal point in the story: on one hand, he is the son of Cimourdain, a republican, and on the other, he is the son of the Gauvain family, Lantenac’s heir. Through him, we are reminded that the Vendée is a fratricidal war. Allusions abound in the novel, for example, when Cimourdain declared his brotherhood with the royalist resistors, a voice, implied to be Lantenac’s, answered, “Yes, Cain.” Gauvain finds himself caught in the middle of such a frightful war. At first, he was able to overlook his kinship with Lantenac, on account of the older man’s monstrosities, but with Lantenac redeemed by his self-sacrifice, it becomes impossible to ignore his threefold obligation: to family, to nation, and to humanity. It is because of this that duty, which seemed so plain to Cimourdain, rose “complex, varied, and tortuous” before Gauvain. The fact is, far from being simple, Gauvain's goodness is neither effortless nor plain, and we are reminded that the most colossal battles of nobility against complacency often happen in the most sensitive of consciences.

Indeed, the triumph of Gauvain is a triumph of the moral conscience, the light which is said to come from the great Unknown, over the dismal times of revolution and internecine strife, “in the midst of the conflagration of all enmity and all vengeance, [...] at that instant [...] when everything becomes a projectile [...], when [...] justice, honesty, and truth are lost sight of [...]” To Hugo, the Revolution is a tempest, in the midst of which we find its tragic actors, forbidding figures as Cimourdain, Lantenac, and the delegates of the Convention, some supremely sublime, some utterly grotesque, and many both: “a pile of heroes, a herd of cowards.” But, at the same time, “The eternal serenity does not suffer from these north winds. Above Revolutions, Truth and Justice reign, as the starry heavens above the tempest.” Gauvain finally comes to peace with this realisation, and we hear him saying, “Moreover, what is the tempest to me, if I have the compass? And what difference can events make to me, if I have my conscience?”

But Ninety-Three is, after all, a tragic book. We might ask whether it is not the case that Gauvain is too much of an idealist. He wishes to found a Republic of Intellect, where perpetual peace eliminates all war, and where man, having passed through the instruction of family, master, country, and humanity, finally arrives at God. “Gauvain, come back to earth,” says Cimourdain. To this Gauvain cannot make a reply. He can only point us upwards, by self-denial, and by his love, towards the ideal.

And the task of the novel is no more than this, this reminder of the reality of life. The drama was created, as the Preface to Cromwell declares, “On the day when Christianity said to man: ‘Thou art [...] made up of two beings, one perishable, the other immortal, [...] one enslaved by appetites, cravings and passions, the other borne aloft on the wings of enthusiasm and reverie—in a word, the one always stooping toward the earth, its mother, the other always darting up toward heaven, its fatherland.’” And did not Ninety-Three achieve this? The legend of La Vendée, like the stage, takes crude history and distills from it reality. Let us conclude with this passage from the novel itself:

“Still, history and legend have the same end, depicting [the] man eternal in the man of the passing moment.”

#victor hugo#ninety-three#quatrevingt-treize#1793#reign of terror#vendée#romanticism#essay#lantenac#gauvain#cimourdain#in an earlier draft I also compared Gauvain to Alyosha Karamazov in a passing comment but I had to take that out for the sake of time#also Cimourdain is definitely a Kantian but doesn’t seem that Hugo approves of Kantian ethics#on the other hand Hugo isn’t Aristotelian either#because in his works reason and the passions are always diametrically opposed#whereas Aristotle / St Thomas would have said that the passions could be trained by reason

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Offer #10 -- translation of Hugo’s writing by thearrogantemu

@thearrogantemu

I’m offering a new English translation of Hugo’s writing, up to ~1000 words. Got a favorite passage you want to see a new take on, a poem, a letter, a chapter?

For background, I’m one of the people working on a Ninety-Three translation; we presented “The Limits of the Inexorable” at this year’s BarricadesCon. For an example of my work, see this translation of the beginning of the ‘loose cannon’ sequence from Ninety-Three.

Once the winning bidder sends me the text they want translated, I’ll send the translation back in about a week.

Opening Bid: $15

(See rules for bidding and offering here)

#submission#translation#victor hugo#Les Miserables#les mis#les miz#quatrevingt treize#ninety-three#and all of hugo's works!

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hougomont vs. La Tourgue

This is kind of a stretch but: Victor Hugo gives the etymology of “Hougomont” as Hugo mons, the mountain built/claimed by Hugo. (This might not actually be accurate.) But, at least, for the reader it sets up an association between this historic location and the family of the book’s author, who is sort of present in these opening chapters as a bystander/character.

Here’s II.1.1:

The sun was charming; the branches had that soft shivering of May, which seems to proceed rather from the nests than from the wind. A brave little bird, probably a lover, was carolling in a distracted manner in a large tree.

The wayfarer bent over and examined a rather large circular excavation, resembling the hollow of a sphere, in the stone on the left, at the foot of the pier of the door.

At this moment the leaves of the door parted, and a peasant woman emerged.

She saw the wayfarer, and perceived what he was looking at.

“It was a French cannon-ball which made that,” she said to him.

Juxtaposition of beautiful nature, plants and animals, with the historic ugliness of the site.

Here’s the last chapter of Quatrevingt-Treize:

Never had the fair sky of early dawn seemed lovelier than on that morning. A soft breeze stirred the heather, the mist floated lightly among the branches, the forest of Fougères, suffused with the breath of running brooks, smoked in the dawn like a gigantic censer filled with incense; the blue sky, the snowy clouds, the clear transparency of the streams, the verdure, with its harmonious scale of color, from the aqua-marine to the emerald, the social groups of trees, the grassy glades, the far-reaching plains,—all revealed that purity which is Nature's eternal precept unto man. In the midst of all this appeared the awful depravity of man; there stood the fortress and the scaffold, war and punishment, the two representatives of this sanguinary epoch and moment, the screech-owl of the gloomy night of the Past and the bat of the twilight of the Future. In the presence of a world all flowery and fragrant, tender and charming, the glorious sky bathed both the Tourgue and the guillotine with the light of dawn, as though it said to man: "Behold my work, and yours."

La Tourgue is short for La Tour-Gauvain, the Gauvain (family)’s tower. The younger and elder Gauvains are important fictional characters in the context of this story, but the name isn’t coincidental, it’s the birth name of Hugo’s mistress, Juilette Drouet. There’s something going on here with the juxtaposition of nature and human destruction, together with the juxtaposition of personal and national history.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Matchs de Poule

Bonjour à tous.tes, on a reçu énormément de suggestions, c'était super. En tout on a 160 livres et BD pour le tournoi !

On va donc commencer par des poules, pour ne garder que 64 livres. Les groupes sont notés ci-dessous (on ajoutera les liens pour les votes au-fur et à mesure qu'ils seront publiés), il y en a 32. Les deux livres recevant le plus de votes de chaque groupes seront séléctionnés pour la suite du tournoi.

Groupe 1

Le Château d'Anne Hiversaire ; Le Petit Prince ; Les Chants de Maldoror ; La Geste des Chevaliers Dragons ; L'Incal

Groupe 2

Les Furtifs ; Un Jacques Cartier Errant ; Même pas Mort ; Yoko Tsuno ; Les Trois Mousquetaires

Groupe 3

Un Sac de Billes ; Malpertuis ; Vango ; Mémoires de Louise Michel ; Les Schtroumpfs

Groupe 4

Femmes d'Alger dans leur appartement ; La Quête de l'Oiseau du Temps ; Bérénice ; La Rose Ecarlate : Vingt Mille Lieues sous les mers

Groupe 5

U4 ; Le Jardin, Paris ; La Passe Miroir ; Romancero aux étoiles ; L'île mystérieuse

Groupe 6

Les 4 As ; Les amis inconnus ; Tobi Lolness ; Persepolis ; Le Jeu de l'Amour et du Hasard

Groupe 7

Vendredi ou la vie sauvage ; L'Autre ; Oh boy! ; Julie, Claire, Cécile ; Le Journal Tintin

Groupe 8

Etudes et Préludes ; Lou! ; Sur les Terres d'Horus ; L'élégance du Hérisson ; Parle-leur de batailles, de rois et d'éléphants

Groupe 9

Lancelot-Graal ; Les Fleurs du Mal ; Chien Blanc ; Mélusine ; Une Tempête

Groupe 10

La Métaphysique du Vampire ; Pot Bouille ; Les Mémoires d'Hadrien ; La bête humaine ; Le Misanthrope

Groupe 11

Tara Duncan ; Trois Oboles pour Charon ; Gaspard de la nuit ; Le Pacte des Marchombres ; Sambre

Groupe 12

Kid Paddle ; Père Castor ; Dom Juan ; Ces Jours qui Disparaissent ; Le Message

Groupe 13

Astérix ; Les animaux dénaturés ; Fantômette ; Germinal ; Mathieu Hidalf

Groupe 14

Le Cid ; Les Carnets de Cerise ; Tant qu'il le faudra ; Rhinoceros ; Dans la Nuit Blanche et Rouge

Groupe 15

Thorgal ; L'arbre à soleils ; Les Faux Monnayeurs ; Alcools ; La Mécanique de Cœur

Groupe 16

Aya de Yopougon ; Chat Noir ; Blake et Mortimer ; Le Survenant ; Le Deuxième Sexe

Groupe 17

Au Bonheur des Dames ; Nadja ; Mille francs de récompense ; Le tour du monde en 80 jours ; Le Butterlyland

Groupe 18

A comme Association ; La Nuit des Temps ; La Guerre de Troie n'aura pas lieu ; Quatrevingt-treize ; Une Famille aux Petits Oignons (Histoires des Jean-Quelque-Chose)

Groupe 19

Le forçat innocent ; Phaenomen ; A la mystérieuse ; Le Livre des Etoiles ; Le Livre de Perle

Groupe 20

L'écume des jours ; Max et Lily ; Petit Ours Brun ; Les Dingodossiers ; Cyrano de Bergerac

Groupe 21

Thérèse Desqueyroux ; La fin du monde ; 47 cordes ; Garin Trousseboeuf ; Oksa Pollock

Groupe 22

Le Grand Secret ; Lucky Luke ; L'Illusion Comique ; Pardonnez nos offenses ; Les Liaisons Dangereuses

Groupe 23

Un Secret ; Fortunes ; Querelle de Roberval ; Manuel de savoir-vivre à l'usage des rustres et des malpolis ; 38 mini westerns (avec des fantômes)

Groupe 24

Les Misérables ; Magarcane ; Frangine ; Les Eveilleurs ; Archives des Anges

Groupe 25

Le Dit de Vertigen ; Spirou et Fantasio ; Antigone ; Le Prince Eric ; Les Colombes du Roi-Soleil

Groupe 26

Cédric ; Sept Jours pour une Eternité ; La Petite Fille de Monsieur Linhl ; Gouverneurs de la Rosée ; Gaston Lagaffe

Groupe 27

Corps et Âmes ; Claudine ; L'œil du loup ; Boule et Bill ; Le Dernier Jour d'un Condamné

Groupe 28

Les Fables de La Fontaine ; La Dame Pale ; Chansons ; Marsupilami ; Les Aventures de Loupio

Groupe 29

L'Enfant de la haute mer ; Du Domaine des Murmures ; La Bibliothécaire ; Ondine ; Dieu n'a pas réponse à tout

Groupe 30

Le Horla ; Réparer les Vivants ; Freaks' Squeele ; De Cape et de Crocs ; L'automne à Pékin

Groupe 31

Ouragan ; Contes des cataplasmes ; Le Monde, Tous Droits Réservés ; Vipère au Poing ; Comment Wang-Fo fut sauvé

Groupe 32

Les Derniers Contes de Canterbury ; Le Compte de Monte-Cristo ; Storm ; Manifeste Assi ; Les Lumières d'Oudja

#bande dessinée#france#french#french side of tumblr#frenchblr#littérature francophone#upthebaguette#français#littérature française#francophone#info !!

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

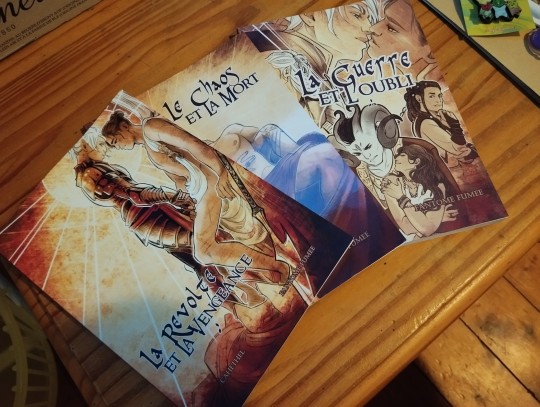

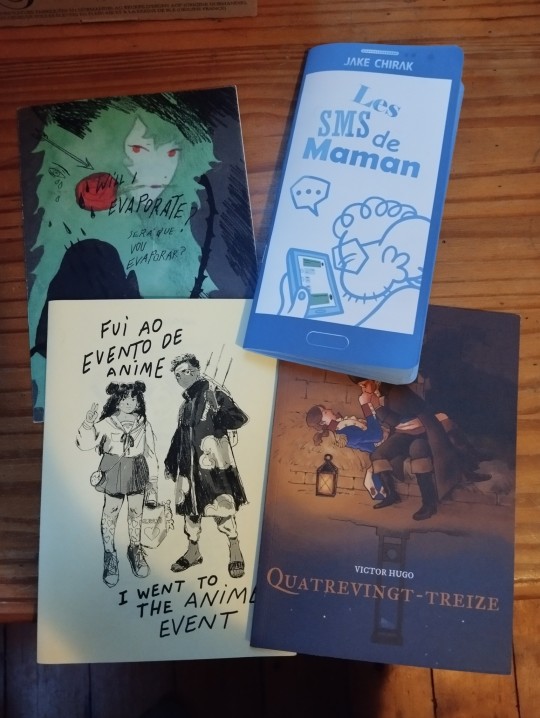

Convention loot!

I... Forgot to take artists cards this time, hhh. So here's what I remember /o/

Occult Officers by @poly-drawz (vol.2 missing because I actually already own vol.1&2 but the old version of vol.1 and the artist gifted me the new version very generously ;;!)

Les SMS de Maman, Pinhead and Salmon Run charm by @jakechirak

Lil' Buddy pin and Hestus pin by @hollowchameleon

Zine & print Quatrevingt-treize by @Domedomini

Zines La Révolte et la Vengeance by Collectif Niddheg

Zines I went to an anime convention and Evaporate by Daniela Viçoso

I will edit after searching a bit more /o\

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Combining two tagging memes into one!

Tagged by @scribeprotra!

The Rules: Tag (9) people you want to know better and/or catch up with, then answer the following:

Four ships: Ranma/Akane, Usopp/Nami, Gintoki/Katsura, Takasugi/Katsura

Last song: Tougenkyou Alien by serial tv drama, the 9th Gintama opening

Currently reading: Quatrevingt-treize by Victor Hugo, Unfinished Tales by J. R. R Tolkien, and to an extent Nona the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir (but I put that one on pause after not reading very much of it, because I should focus on finally finishing Quatrevingt-treize). I have manga and comics to read too but I haven't started a new volume yet.

Last movie: It feels like way too long that I actually watched a whole movie from start to end. I'm honestly not sure which was the latest one.

Craving: Sleep

Tagged by @sebfreaks!

favourite colour: It used to be deep red, bright red and mossy green, but nowadays it's more like purple, burgundy, and emerald green or what we call "vårgrönt" in Swedish (lit. 'spring-green').

song stuck in head: Good Vibrations, Beach Boys

favourite food: not sure overall but when it comes to cooking, i mostly do various stuff with pasta.

last song listened to: Tougenkyou Alien by serial tv drama, the 9th Gintama opening

dream trip: Flying to New Zealand or Japan on a solar-powered plane

last thing i googled: The colour burgundy, just now, to check that it was approximately the hue I was thinking of. Colour names are tough. (Though I use duckduckgo rather than Google for privacy reasons.)

Tagging: @averagelonelypotato @kattahj @katsusks @scenexstealer @taketotheskies @tijuanabiblestudies @listening-to-thunder

@wehavecometoanend--maybe @writesailingdreams @suchira @suchine-toki @sniperofmyheart

I tagged a whole lot of people now because I combined two memes into one, but it's fine to do just one of these or none and tag however many you please, of course!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Based on The Dungeon chapter from Victor Hugo’s Ninety-Three, in which Gauvain outlines his political views to Cimourdain.

446 notes

·

View notes

Text

r/mildlyinteresting - a black metal album about the Vendée uprising, was reminded of its existence after finishing Quatrevingt-treize

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

53. In a magnificent game of doubling his heroes, Hugo also pairs Enjolras with Combeferre, who "completes and rectifies him" (483; [le] complétait et rectifiait), as Gauvain corrects Cimourdain in Quatrevingt-treize (Ninery-Three; hereafter QVT). Enjolras is associated with revolutionary greatness; his friend, we are told, exemplifies the beauty of progress. These separate orientations encompass all reality: Combeferre is "lower and broader" than Enjolras, opening around the "steep mountain" a "vast blue horizon" (483; moins haut et plus large . . . montagne à pic . . . vaste horizon bleu). Fusing vertical and horizontal axes, they repeat the paternal/fraternal patterns operating throughout the novel. Yet both are subsumed by their utopian goal, so that they do not differ any more than an angel with "swan's wings" does from one with "eagle's wings" (484; ailes de cygne . . . ailes d'aigle). Their two-pronged endeavor to enhance human liberty imitates genius's "winging toward the sublime" (691; coup d'aile vers le sublime). In QVT, this imagery characterizes Gauvain and Cimourdain when "these two souls, tragic sisters, take flight together, the shadow of the one mingled with the light of the other" (15-16.1:509; ces deux âmes, sœurs tragiques, s'envolèrent ensemble, l'ombre de l'une mêlée à la lumière de l'autre). In MIS, it is Enjolras and Grantaire who fly away together in the execution/suicide scene.

Kathryn M. Grossman, Figuring Transcendence in Les Misérables: Hugo’s Romantic Sublime

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Victor Hugo writing literally anything:

#victor hugo#books#dark academia#ninety-three#quatrevingt-treize#les mis#les miserables#notre dame#reading#bo burnham#inside#meme#memes#op

160 notes

·

View notes

Note

the name of gauvain (the viscount) is gauvain gauvain? I saw in the original manuscripts of the book present on wikisource that the marquis' name is Hercule.

I think it's like Les Mis, where the younger Gauvain has a first name but we're never told what it is because it's not relevant.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Note: Les deux choix ayant le plus de votes seront conservés pour la suite du tournoi

8 notes

·

View notes