#legacy: rigby

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

reconnecting

#ts4#sims 4#sims 4 maxis match#ts4 maxis match#ts4 gameplay#sims 4 gameplay#legacy: rigby#clementine rigby#lucian rigby#sebastian rigby#legacy challenge

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

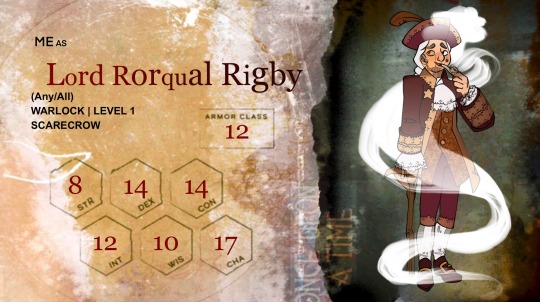

Haven’t done one of these in forever but he’s fun and I wanted to draw them.

Template is from @poncivalpishpuff and Giuseppe Lama

#Rorqual is another name for the Razorback whale and Razorback is the trail that gets you up Feathertop Mt in Australia#it’s very convoluted but it’s cute#again ‘scarecrow’ is a reskin#he’s an undead but his ancestral legacy is that of a warforged#plot wise he was going back to Mother Rigby’s home to return her pipe and give up on life#but found evidence of a horrible struggle instead#as awful as he finds being a facsimile of a human to be#he’s certainly not willing to abandon his mother#unfortunately his only remaining magic is whatever the fiend Dickon she entrusted to him can muster#and it’s eating away at his illusion of life#my art#Neverafter oc#neverafter d20#my ocs

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Playlist in progress. Songs will be added as new scenes of Jayce and Viktor are shown.)

Continue reading to find out why the songs were included.

Eleanor Rigby is a song about death and the legacy of a life that went unnoticed. I believe the song is an excellent fit for Zaun and Viktor's storyline from Season 1.

Evolution Once Again, My Body is a Cage, and Run describes the growing rift between Viktor and Jayce. With romantic connotations. One-sided. Yeah. I am here to break your heart.

Those Were the Days is a song originally from Russia. It is about the narrator's past youth and naivety, as well as the inability to recognize who you or your friends have become. The song is brimming with nostalgia, which fits the scene of Jayce and Viktor reminiscing about the past in the iron fortress.

As the World Caves In is the finale of Season 1 and Jayce's desperation to save his life.

Son of Nyx is a reference to Charon, who transports souls through the River of Styx in the Underworld of Hades. Its instrumentals matched Viktor's eerie chrysalis and Jayce's demeanor as his partner approached death. The sudden shift in melody is Viktor coming out of his cocoon.

Goliath's instrumental is for the Hexcore. Meanwhile, the lyrics describe the narrator's relationship falling apart while their partner pretends nothing is wrong.

Exogenesis, in both parts, fits perfectly with Viktor's new Jesus storyline. The first part is about existential crisis. The second part is becoming the savior, with no way back.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

TEAM THUNDERDOME.

TWO TEAMS ENTER. TUMBLR VOTES. ONE TEAM LEAVES. TRIAL BY COMBAT. TO THE DEATH. VICTORY OR SOVNGARDE.

The Rules:

Fights will occur over the course of ONE WEEK, quarter 1 begins JUNE 1ST, 2024 at 12:00 AM MIDNIGHT EDT (UTC-04:00).

Multiple fights happen across one week.

ONLY 3 to 4 team members per team. 2 is too few, 5 is almost cheating. If a team has more than 4 members, some will have to wait in the stands (looking at you, Scooby-Doo and Tally Hall).

Tumblr poll will determine the winner of an individual fight via emotional support and gracious cookie donations.

Majority Wins. Whether or not a team would canonically win or lose the fight does not matter, only the number of votes.

Single Elimination.

Outside of the rules listed above, anything goes. Reblog a fight to get your friends on your side.

Propaganda is fair game. If you know perhaps a little too much about one of the teams and want to explain why your team should win, please submit an in-depth propaganda post to the blog homepage.

Spread the word! Your favorite might win! (Or not! I just run this thing!)

Lasko Wind Machine

All 64 Teams Competing (In random order - will NOT reflect the final bracket):

Team WINCHESTER (Sam, Dean, Castiel, Crowley)

Team FORTRESS (Heavy, Medic, Engineer, Soldier)

Team AIONIOS (Noah, Lanz, Eunie, Riku)

Team GONDOR (Aragorn, Legolas, Gimli, Gandalf)

Team TWILIGHT (Jacob, Edward, Bella)

Team STAR WARS (Han, Luke, Leia, Chewbacca)

Team NARUTO (Naruto, Sasuke, Sakura)

Team SHREK (Shrek, Fiona, Donkey, Puss In Boots) (As portrayed at the end of Shrek 2)

Team OF LIGHT (Jonathan Harker, Jack Seward, Quincey Morris, Abraham Van Helsing)

Team PERSONA (Makoto Yuki, Kotone Shiomi, Yu Narukami, Ren Mamamiya)

Team HOMESTUCK (John, Jade, Rose, Dave)

Team MUSKETEERS (Athos, Porthos, Aramis, D'Artagnan)

Team HERCULES (Hercules, Iolaus, Salmoneus, Autolycus) (The Legendary Journeys, Hercules as portrayed by Kevin Sorbo)

Team PUYO PUYO (Ringo, Arle, Amitie, Lemres)

Team BAKUGO (Bakugo, Mina, Denki, Eijirou)

Team WIGGLES (Jeff, Anthony, Murray, Greg) (as originally formed)

Team GRYFFINDOR (Harry, Ron, Hermione)

Team COOL RUNNINGS (Derice Bannock, Junior Bevil, Sanka Coffie, Yul Brenner)

Team AEGIS (Rex, Pyra, Mythra) (all other party members excluded due to Blades and their pesky "friendships" binding them to their users)

Team RHYTHM THIEF (Raphael, Fondue, Marie, Charlie) (what a cute doggy :3)

Team MYSTERY INC (Fred, Shaggy, Velma, Daphne) (sorry no pets allowed)

Team DEKU (Izuku, Tsuyu, Ochako, Shouto)

Team KRISPIES (Snap, Crackle, Pop)

Team ELITE BEAT (Agent Spin, Agent J, Agent Chieftain, Agent Starr)

Team JIGSAW (Kramer, Young, Hoffman, Gordon)

Team UMIZOOMI (Milli, Geo, Bot)

Team TRIFORCE (Link, Zelda, Groose) (Skyward Sword variants)

Team LAYTON (Layton, Luke, Emmy) (Pre-Azran Legacy)

Team SONIC (Sonic, Knuckles, Tails)

Team ASKR (Alfonse, Anna, Sharena)

Team TARDIS (The Doctor, Amy, Rory, River)

Team WOOHP (Sam, Alex, Clover)

Team KEYBLADE (Sora, Donald, Goofy)

Team 1908 THOMAS FLYER (Montague Roberts, George Schuster, Hans Hendrik Hansen, George MacAdam)

Team BIONIS (Shulk, Reyn, Dunban, Sharla)

Team DARK (Shadow, Rouge, Omega) (Ultimate Life Form status tenuous)

Team OOO (Finn, Jake, Princess Bubblegum, BMO)

Team TALLY HALL (Rob, Zubin, Andrew, Joe) (Ross excluded - he's just a drummer)

Team DOODLEBOPS (Deedee, Rooney, Moe)

Team SCIENCE (Gordon, Tommy, Bubby, Dr. Coomer)

Team POWERPUFF (Blossom, Buttercup, Bubbles)

Team INCONCEIVABLE (Inigo, Fezzik, Vizzini)

Team METROCITY (Megamind, Metro Man, Roxanne, Minion)

Team WONDER PETS (Linny, Tuck, Ming Ming)

Team REGULAR (Mordecai, Rigby, Muscle Man, Skips)

Team PILLAR MEN (Santana, Wham, ACDC, Kars) (Ultimate Life Form status tenuous)

Team BEATLES (John, Paul, George, Ringo)

Team SMILING FRIENDS (Pim, Charlie, Glep, Alan)

Team ROTTEN (Robbie, Tobby, Bobby, Flobby) (Ultimate Life Form status confirmed)

Team KRUSTY KRAB (SpongeBob, Patrick, Squidward, Mr. Krabs)

Team VOCALOID (Hatsune Miku, Kagamine Len, Kagamine Rin)

Team GARFIELD (Garfield, Jon, Odie, Liz)

Team POOH (Pooh, Piglet, Eeyore, Christopher Robin)

Team AVALANCHE (Cloud, Tifa, Aerith, Barret)

Team LOONEY (Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig, Michael Jordan)

Team GHOSTS (Blinky, Pinky, Inky, Clyde) (freshly dead)

Team ROCKMAN (Rock, Roll, Blues, Bass)

Team MARIO (Mario, Luigi, Wario, Waluigi)

Team WRIGHT (Phoenix, Apollo, Athena, Trucy) (as seen in Dual Destinies)

Team SHERLOCK (Sherlock, John, Mycroft) (Brigandorf Crimplesnart's depiction of Sherlock)

Team MASH (Benjamin Franklin "Hawkeye" Pierce, BJ Hunnicutt, Charles Emerson Winchester III)

Team RWBY (Ruby, Weiss, Yang, Blake)

Team CHANNEL 5 (Ulala, Space Michael, Jaguar, Pudding)

Team FANBOY (Fanboy, Chum Chum, Kyle)

GOOD LUCK!!!

(you're gonna need it)

#TEAM THUNDERDOME#tumblr bracket#bracket tournament#supernatural#doctor who#team fortress 2#m*a*s*h#mash#space channel 5#rwby#the doodlebops#the wiggles#bbc sherlock#ace attorney#super mario#pac man#final fantasy vii#looney tunes#garfield#winnie the pooh#vocaloid#spongebob#spongebob squarepants#mega man#rockman#lazy town#robbie rotten#the beatles#pillar men#jojo's bizarre adventure

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

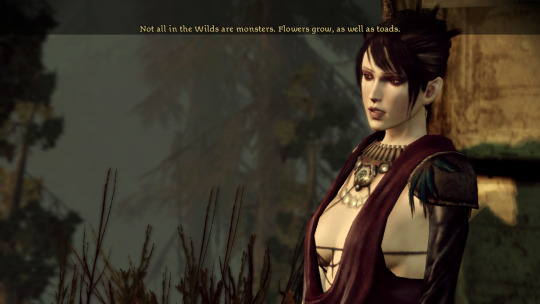

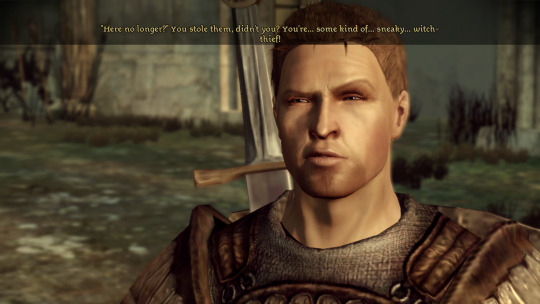

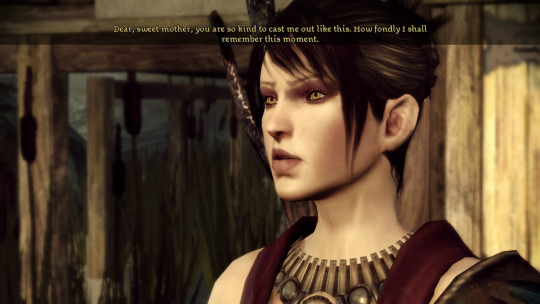

Ostagar, Part III: The Korcari Wilds and its Witches

Last, we need to talk about the history of Ostagar and the surrounding Korcari Wilds.

Per the codex, Ostagar is an old fortress from the days of the Tevinter Imperium. Its purpose was to be a bulwark against aggression from the Chasind, another human tribe like the Alamarri that would form Ferelden and the Ciriane that would become Orlais.

Tevinter built this massive fortress but then they didn't have it for very long. Beginning in 7205 and raging for two centuries, the First Blight drove Tevinter out of the southern lands.

Dumat's war cost Tevinter control of the south, and allowed the Alamarri, Ciriane, and Chasind to consolidate their power in those regions. Eventually culminating in the Alamarri Andraste's rebellion against Tevinter.

Ostagar came into the possession of the Chasind. They would retain control of it for about seven or eight centuries until the unification of Ferelden under King Calenhad resulted in the Chasind being driven further south.

For the next four hundred years, the fortress sat there and rotted. Until King Cailan and Teyrn Loghain decided to use it as a staging ground for their plans against the Fifth Blight.

There's not a lot to say about the Wilds themselves. By definition, they are a place where not a lot of history that we know about has happened. This is a region of Thedas occupied by the "wilders", as Fereldans call them. Which means the Chasind.

The Fifth Blight began way out here, on the outer edge of the formally acknowledged civilizations. Urthemiel, Old God of Beauty and the avatar to the Evanuris June, God of Crafts, was awakened somewhere deep beneath these woods. They were able to amass out here with only the Chasind being the wiser, and the Chasind don't really talk to the other nations.

A minor story in the Wilds concerns this unfortunate dipshit.

Missionary Rigby might just have been the first Fereldan to discover the Blight. This poor bastard is an Andrastian Missionary who came out here trying to spread the Chant of Light to the Chasind.

It did not go well. He never found the Chasind, as they had already fled the area to escape from the growing Blight. At the same time he was trying to unpack what happened to the Chasind, he received word that his son Rigby had become a missionary and was coming out to join him.

He initially sent Rigby some light admonishment for picking the Korcari Wilds of all places for his first mission, but left him instructions on where they'd meet up. He would soon come to regret that mistake.

These statues were supposed to be their meeting point inside the Wilds. But instead, all that's waiting here is a weapon and a note to Jogby, warning him to grab the weapon and get the fuck out. By this point, Rigby knew he wasn't making it out alive, and left everything he had for Jogby.

Jogby never even made it this far.

His body is one of the first things you find in the Wilds. The Darkspawn killed him before he'd barely even set foot in this place. The Blight is a bad time to go wilderness hiking.

But don't go feeling too bad for Rigby. He could have left once he realized the Chasind were gone, but he lingered in this place because he got greedy.

At Rigby's encampment, his journal explains what he was still doing out here. He found Chasind markings suggesting some sort of treasure cache in the area. And he figured, hey, the Chasind aren't around so....

Yeah, Missionary Rigby died trying to capitalize on the Blight to loot Chasind coffers. His body is lying about halfway down the path. It's just a shame his son had to die for that too.

It's disgusting. Fortunately, I am a member of a proud and noble legacy of heroism and virtue, and would never stoop so low as to--

...look, man. It's the Blight. The Wardens need to pursue every avenue for supplying our forces that we can!

Ehehe... Hehehe....

Armies are fucking thieves. In fact, there's another little sub-story happening in these woods and it concerns this dipshit.

This is Markus. He was killed by Darkspawn before he had his chance to be killed by stupidity. Looting his corpse reveals a pinch of ashes and the story of star-crossed love.

See, there was this woman Astia who was friends with a spirit named Gazarath. Odd name for a spirit, as they're typically named for whatever particular concept they embody, but we can roll with it. Maybe Gazarath is what Astia named him.

Anyway, love triangle shit happened. Astia loved a man named Nebbunar, which enraged Gazarath because Gazarath loved Astia. Gazarath demanded that Astia murder Nebbunar or their friendship was fucking over.

Astia did so, slitting Nebbunar's throat on their wedding day and bringing his ashes to Gazarath as proof. The. Uh. The legend is conspicuously silent about what happened to Astia after that.

But it does say that if you bring Gazarath ashes, he'll grant you a wish! That sounds plausible!

If you feel like being unbelievably stupid, you can try it out for yourself.

Holy shit, it works! One wish, please! ...no? Just violence? Okay.

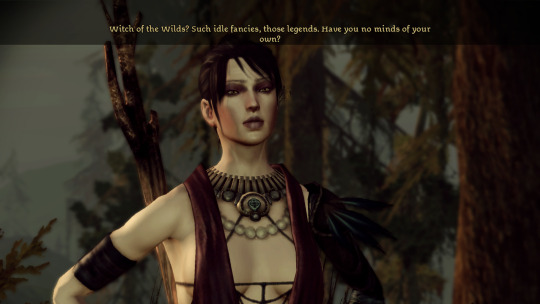

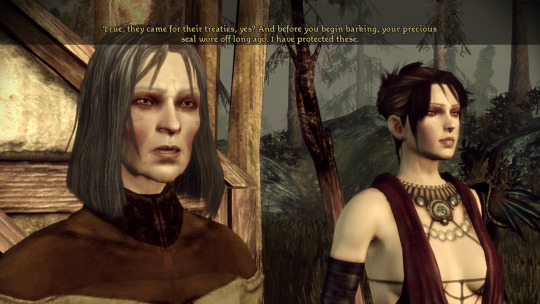

But obviously, the stars of the Korcari Wilds section of the game are the Witches of the Wilds themselves.

Morrigan and Flemeth are basically the face of Dragon Age. In a sense, the myth arc that's transpired across the four games has been their story, playing out in the background until its conclusion in Veilguard.

It's honestly funny that Morrigan dismisses the superstitions around the Witches of the Wilds. Because. Like.

Morrigan is a shapeshifter adopted by a fragment of an elven goddess that immortalized herself by passing from body to body. At the end of this game, she may or may not perform a magic ritual to safely reincarnate the soul of an Evanuris and spare the Grey Wardens from the price of slaying the Archdemon, which is a feat of magic unthinkable to literally everyone else.

There's a lot of sincerely weird shit going on with Morrigan and Flemeth that's way outside the realm of ordinary magic as it's recognized in Fereldan society. They are on a completely alien level when it comes to weaving impossible sorceries drawing on esoteric forces unknown to the denizens of Thedas.

But turning people into toads is the line she wants to draw. Okay.

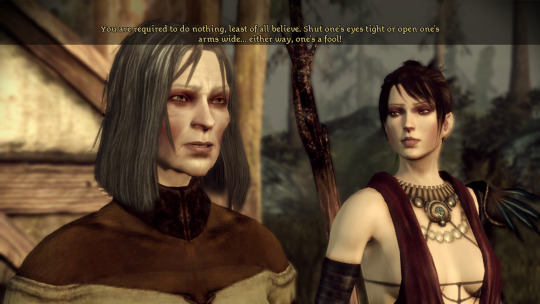

Of course, Morrigan is immediately meant with suspicion and hostility despite the fact that she's literally just here to offer the Wardens their treaties back.

Alistair's right to be suspicious, but he's wrong to be suspicious. Morrigan and Flemeth are playing the Wardens but....

Well....

It's kinda like when you hide a pill inside a hot dog and give it to your dog. You're tricking the dog, but it's for the dog's own good.

Or, to quote Jory and Daveth:

The pot is so much warmer than this forest. You have no idea.

Alistair immediately suspects the Witches of having broken into the Warden ruins and stolen their treaties from a sealed chest. Flemeth tells a different story.

This is probably a lie. The chest that the treaties were supposed to be in looks to have been broken open by force, which seems odd if the seals merely broke on their own. Supposedly, only a Grey Warden could break into the chest, but Mythal's powers are vast and esoteric.

Flemeth seems to have a capacity for future sight. She already knows much of how the Blight will play out, even telling Jory to his face that he's inconsequential. She and Morrigan are turning the wheels of their preferred endgame, and so it seems likely that Flemeth did break into the chest in order to give the Wardens a reason to come to her.

Again: We are being played. For our own good.

Morrigan and Flemeth's sinister endgame is to retrieve June's soul from Urthemiel in such a way that the Blight ends, June goes free, and no Warden has to be extinguished to do it. They are manipulating the Wardens to achieve good things for everybody, and the only drawback is that June's soul ends up in the hands of suspicious people.

We all get the happiest possible ending, but what is that woman going to do with the God Soul? We don't know. And neither do the writers because the answer ends up being nothing whatsoever.

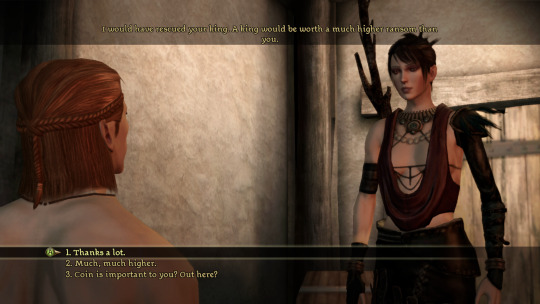

Morrigan is eerie, but it's just a vibe. She's basically the overarching protagonist of this entire franchise.

She will express terrible opinions all the time.

She's kind of an asshole. But throughout the four games, there is consistently no better choice you can make than embracing and working in confidence with the Witches of the Wilds.

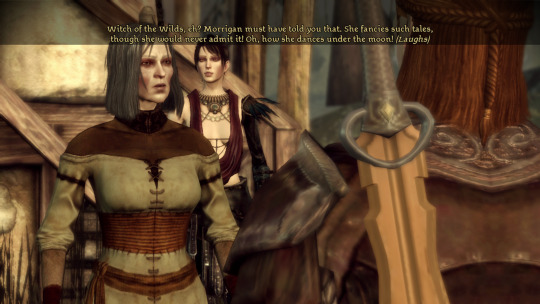

In fact, Morrigan is intentionally a vibe. Flemeth outright says that she just likes the optics of the Witch of the Wilds.

According to Morrigan's mother sharing embarrassing stories about her, Morrigan likes to go out and do witchy moon dancing for no other reason than to be doing witchy moon dancing. She's just. She knows what they are and she's all-in on the bit.

Morrigan loves the Witch of the Wilds aesthetic. She plays up her own spookiness on purpose. T'is probably why she talks like that when no one else in Thedas does.

And why she has so much fun teasing Alistair about his uptight Templar shtick.

Morrigan is a vibe. On purpose.

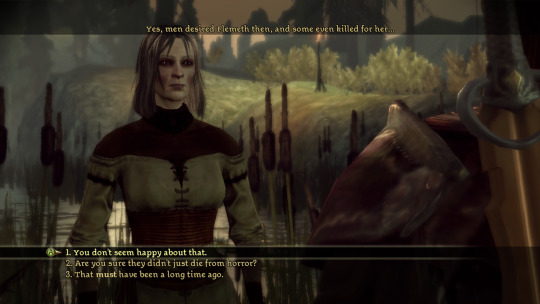

We only meet them briefly before the Battle of Ostagar but they're here to show us the way out at the end. It's Flemeth who makes moving against Loghain possible by saving two Wardens who would have perished with the rest at Ostagar.

Flemeth is in complete control of this situation. She feigns ignorance, of course.

I mean, you and Fen'harel literally created the Blight but go off.

But, under the veil of obviously fake innocence, it's Flemeth who gently coaxes Alistair into devising a plan he didn't even know he had in the back of his mind.

Mythal is putting her talon on the scale to move against June. Through Alistair and the Warden, she's setting the events in motion that will - if all goes to plan - release and reincarnate June's soul from his avatar Urthemiel.

Even if Morrigan can't quite appreciate the machinations that Flemeth has in motion, and is left floundering to try and keep up.

But despite her plans, Flemeth also has a great deal of hostility towards Thedas. She speaks cryptically about her past, but sufficient knowledge of her history can make sense of her words.

There are many stories about the human woman named Flemeth but the recurring elements are similar. Flemeth loved one man named Osen and was jealously coveted by another named Conobar, who murdered Osen to take Flemeth as his own. In desperation, Flemeth sought aid from spirits and became possessed.

What none of the tales know, of course, is that it was the Evanuris Mythal who came to her then. Neither spirit nor demon but a murdered elven goddess whose fractured spirit was left adrift..

But her resentment here of men who've killed for her is probably about Conobar.

This, on the other hand?

Is most certainly Mythal reminiscing about her betrayal and murder by the Evanuris, thousands of years ago in a history that the Tevinter Imperium burned to the ground.

Mythal, Flemeth, and Morrigan are key figures in the mythology and world of Thedas. And it's right here, in the aftermath of Ostagar, where they step out of the woods to shape the fate of the continent.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

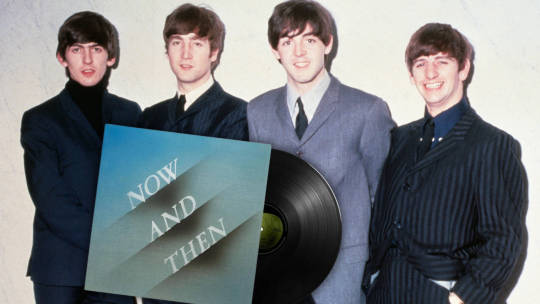

So, here are my thoughts on Now and Then

Can you believe we just got a Beatles song??? because I'm still trying to wrap my head around it. Ever since last week my expectations of this song were high -I mean it is them either way-, but this was way more incredible than i could have expected.

It is them. I know it sounds stupid to say it, but it feels like them. It's been over 50 years since the four of them made music together and yet this brings me back to them at their prime, with John bringing the lyrics and the soft voice, Paul the musicality and the experimentation, George the wonderful guitar and Ringo always knowing how to adjust perfectly to the rhythm. It's them being them, which might not be a cause of surprise if it weren't for the fact two of them are no longer with us. The fact they managed to pull this off out of pure love and respect for one another, for their legacy as a group, as the biggest of all time, is mind-blowing to me.

I'm amazed at how Paul wanted it to be mostly a John song, and abid to that with so much respect. The fact he only sings to complement John's voice, to add depth and to bring us back to what it felt like to listen to both of them, I love it so much. I am also very much aware of the fact this is John in his 30 something singing it with Paul in his eighties, and it shows: their voices together sound like always but sound like never. You can feel that time has passed for Paul and I love it because it is the essence of now and then.

The backing vocals, the fact they used vocals from the four of them is everything to me. The string arrangements give us the sound of the Beatles in such a unique and wonderful way, you can't help but feel this belonged to a space reserved somewhere between Eleanor Rigby and Because, and it is perfectly placed right there. You can tell everyone involved on it loves and knows the Beatles completely, which is no surprise considering Macca and Giles were the geniuses behind it.

I do have one tiny comment: the production feels very 2023-ish, which is not bad, it just feels a bit too modern, takes me out a bit from the 1960s rhythm that made me fall in love with them in the first place, but I understand times have changed and this also has to sound contemporary, is what they would have loved. I'm just old-fashioned.

I feel John. I feel Paul. I feel George. I feel Ringo. Everything that made them them is present within those four minutes. Everything, including John and Paul's endless intense, complicated and absolutely beautiful love for one another.

This is the most precious and perfect gift and I can't thank Paul and Ringo enough for giving us the chance to live one last release. Never thought I would live to experience with the world a new Beatle song, and I feel it like the biggest treasure.

They remain my everything. And I can't wait for the music video.

Oh, and the fact it's done and Love Me Do starts right after. My heart can't take it.

Anyway, so many things to say, so many things I love. Let me know what you thought!!!

#now and then#the beatles#john lennon#paul mccartney#george harrison#ringo starr#thank you for being my entire life dear fab four#i love you forever#thank you for saving me#anyway#i have so many feelings

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

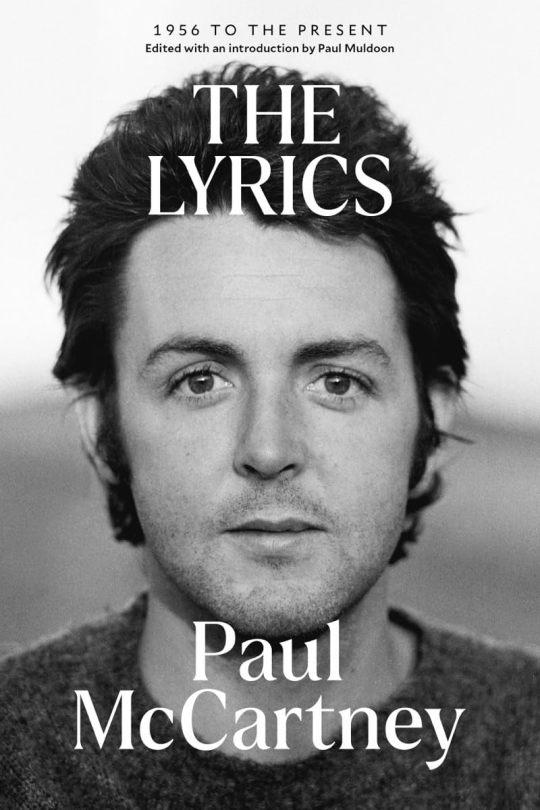

The AKOM Holiday Shopping Guide!

Here are some items we enjoyed this year, great choices for yourself or that Special Beatle Person in your life.

The Lost Weekend A Love Story (DVD, Blu-Ray, Streaming) 🥤 The McCartney Legacy by Allan Kozinn and Adrian Sinclair (Hardback and audio book!) 🐏

The Fifth Beatle (10th Anniversary edition) by Vivek Tiwary 🍏 Living the Beatles Legend: The Untold Story of Mal Evans by Kenneth Womack ⏰

Now and Then, new Beatles single!! 📀

The Lyrics: 1956 to Present by Paul McCartney and Paul Muldoon (now in Paperback) 🎁 Eyes of the Storm by Paul McCartney 📸

Related AKOM podcasts: Reclaimed Weekend AKOM Talks w/ May Pang Frankensongs! AKOM Talks w/ Adrian Sinclair and Allan Kozinn The Fifth Beatle AKOM Talks w/ Vivek Tiwary The Mal Evans Story AKOM Talks w/ Ken Womack Eleanor Rigby: (The Lyrics podcast) Now and Then Reactions (IamtheEggpod)

#AKOM#recs#we aren't getting kickbacks#LOL#just thought we'd share our recs#another kind of mind#beatles

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

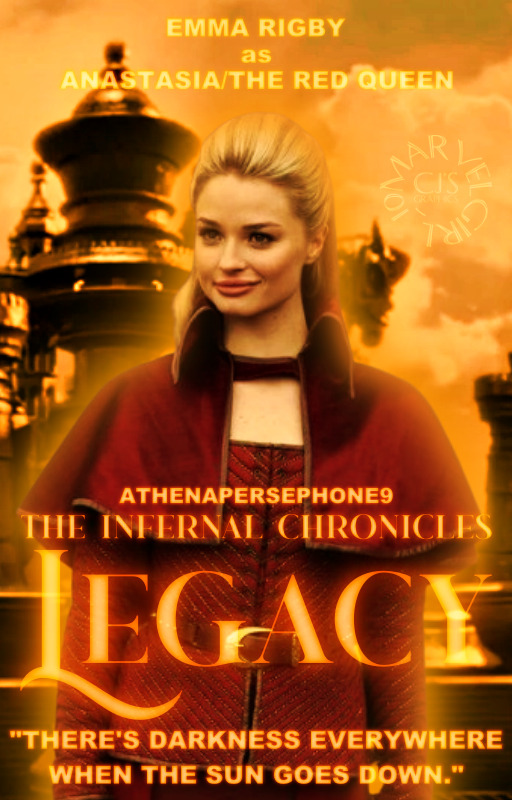

Manips for AthenaPersephone9 Series: The Infernal Chronicles on Wattpad Faceclaims: Camila Mendes, Colin O'Donoghue, Sean Maguire, Lola Flanery, Agnes Bruckner, Ginnifer Goodwin, Jennifer Morrison, Lana Parrilla, & Josh Dallas

Posters for AthenaPersephone9 Book: Legacy on Wattpad Faceclaims: Michael Socha & Emma Rigby

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

WEEK FOUR LINEUP

Some minor changes this week, we have officially retired the SEE RESULTS option on the polls, down to five options. I probably won't be adding any new options unless there's a very good reason or high demand, so I'm sorry to the people who have asked for a "I know them and I love them with all my heart, positive cannot contain the love I have for them" option. With that being said, here is this week's lineup!

Mimi - Your Imaginary Friend

Tsubasa Arihara - Cinderella Nine

Tablet - Commodity Clash

Fox Alistair - RWBY

Alan B'Stard - The New Statesman

Sportacus - LazyTown

Tougou Mimori - Yuuki Yuuna is a Hero & Washio Sumi is a Hero

Rottytops - Shantae

Naomasa Tsukauchi - Boku no Hero Academia

Hagumi Hanamoto - Honey and Clover

Bellringer - Toontown Corporate Clash

Tarlach - Mabinogi

Ata Ibusuki - Binan Koukou Chikyuu Boueibu Happy Kiss

J - Heat Guy J

Mami Tomoe - Madoka Magica

Rocket Raccoon - Marvel Cinematic Universe

Princess Elle - Hirogaru Sky Precure

Phèdre nó Delaunay - Kushiel's Legacy series

Rex Mohs - Scott the Woz

Eileen Roberts - Regular Show

Waluigi - Super Mario

Rick - Denpa Men

Great Sage - Miitopia

Sidon - Legend of Zelda

John F. Kennedy - Clone High

Greg Heffley - Diary of a Wimpy Kid

Martin - Wii Sports

Yellow Face - Battle for Dream Island

Eraser - Battle for Dream Island

9-Volt - WarioWare

Luigi - Super Mario

Milo Murphy - Milo Murphy's Law

Rigby - Regular Show

Holidog - Holiday World

Jerry Attricks - Scott the Woz

Jeb Jab - Scott the Woz

Peter Griffin - Family Guy

Baljeet Tjinder - Phineas and Ferb

Gary - Regular Show

Skelly - I Spy Spooky Mansion

Max Schnell - Cars 2

Charley - Incredibox

10th Doctor - Doctor Who

Mii Brawler - Super Smash Bros

Miles Morales - Into and Across the Spiderverse

Party Phil - Wii Party

Lego Joker - Lego Batman

Knife - Inanimate Insanity

Fusk and Vorte - Hitmen for Destiny

Chaika Trabant - Hitsugi no Chaika

Jesse Pinkman - Breaking Bad

Agent - Penguinronpa

Squelch - Denpa Men

Muscle Man - Regular Show

Fuuta Kajiyama - MILGRAM

Jonathan Phaedrus / Prof - The Reckoners

David Charleston - The Reckoners

Spensa - Skyward

M-Bot - Skyward

Chet Starfinder - Skyward

Sirius Gibson - Witch’s Heart

Guy Montag - Fahrenheit 451

Zachary Zatara - DC Comics

Kento - Payday 2

The Shapeshifter - The Odd Squad

Akane Kurashiki - Zero Escape Trilogy

Letitia "Letty" Price - Babel

The Last Son of Alcatraz - The Monument Mythos

Lily - Duolingo

Ohio - The United States of America

Myne - Ascendance of a Bookworm

Rani - Disney Fairies

Agrael/Raelag - Heroes of Might and Magic

Donna - RErideD: Tokigoe no Derrida

Kasane Teto - Vocaloid

Martin the Warrior - Redwall

Colombo - Colombo

Sonny Wortzik - Dog Day Afternoon

Butch Cassidy - Butch Cassidy and the Sundance kid

Blondie - The Good The Bad and The Ugly

Prior Walter - Angels in America

Dark - Nowhere

Reona West - PriPara

Shax Lied - Mairimashita! Iruma-Kun

Villager - Minecraft

Wahanly Shume - Tenchi Muyo! War on Geminar

Qifrey - Witch Hat Atelier

Marvin - In Trousers

Mr. Bungee - A New Brain

Mayor Mingus - Dialtown

KAITO - Vocaloid

Almond - Postknight 2

Serial Designation V - Murder Drones

Flint - Postknight 2

Magnolia - Postknight 2

Nobara Kugisaki - Jujutsu Kaisen

Snufkin - The Moomins

Ikabod Kee - The Upturned

The Professor - Hailey's On It!

Chimumu - Waccha PriMagi

Mia Taylor - Love Live

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Other Playlist™

I was recently asked to make a young justice playlist so here it is!

@automaticsoulharmony it’s for you :)!

The young justice playlist is under the cut with explanations for each song

Tim

Ur gonna wish u believed me (start of brucequest)

Yes I’m a mess (I could see him deleting his identity)

Karma (AJR) (depressed man)

Mastermind (smart Timmy)

Don’t blame me (all his action with the loa)

Fool (him with the Wayne’s)

Wow, I’m not crazy (him when he meets the bats (he is crazy))

Humpty Dumpty (he’s a depressed lil guy)

Good 4 u (to dick about Damian)

Pretender (Acoustic) (Jason canonically calls him pretender I had to)

Mister Cellophane (everyone forgets about him)

Come hang out (he’s a workaholic)

Let the games begin (Tim enjoys power)

Heart of stone (depressionnn)

brutal (it’s just Tim coded)

Deja vu (to dick about Damian)

Every breath you take (stalker)

The sound of silence (he is so fucking depressed)

Go the distance (start of robin training and brucequest)

Viva La Vida (Tim coming back to Gotham)

Bart:

What ifs (him going to past)

2085 (he’s from the future)

Bones (him running)

Everything has changed (him coming back to life)

When will my life begin (him in vr)

We didn’t start the fire (he is from the future)

Go the distance (him going back in time)

Iron man (time travel)

How far I’ll go (look it’s easy to find Disney songs about going back in time)

For the first time in forever (him meeting actual humans after being raised in vr)

Adventure is out there (very adhd coded song very adhd coded character)

Into the unknown (going back in time)

Dead! (he died)

The nights (it gives me his vibes)

Blackbird (finally being in the real world)

Record player (he’s from the future so it would make sense for him to find 2014 old)

Over the rainbow (going to the real world)

Wow, I’m not crazy (meeting the rest of YJ)

The DJ is Crying for Help (him wondering what to do after becoming an adult)

Centuries (from the future so he knows they will be remembered for centuries)

Kon

Father of mine (Clark sucks)

Dead! (he died)

Teenagers (it gives me his vibes)

All you wanna do (he was canonically taken advantage of by several women immediately after being “born”)

Oops! I did it again (player)

Too late (him maturing)

Used to be young (him after the playboy years are over)

Cat’s in the cradle (Clark still sucks)

You’re on your own, kid (horrible father)

When will my life begin (being in CADMUS and wondering when he can leave)

What else can I do (discovering his powers)

Pity party (he was canonically forgotten by everyone he loves after flashpoint)

Rip (by bladee) (I’m still focusing on the being forgotten thing)

Drift away (talking about the other superboy who came to be while he was trapped in another dimension)

Pretty fly (for a white guy) (he’s a player)

Uptown girl (Cassie!)

Rät (finding out CADMUS is evil)

Back to life (I think the name explains it)

Sober up (talking to YJ)

Shake it off (him responding to insults he gets)

Cassie

Just a girl (it’s hard being a female superhero)

Me too (badass woman)

Clara Bow (how it feels being a legacy sidekick)

Thunder (she’s Zeus’s kid)

Emotionless (good Charlotte) (Zeus is not a good father)

Brutal (her Bart and Kon’s deaths meltdown)

Cat’s in the cradle (I really hate Zeus)

Toxic (her about Kon)

I can do it with a broken heart (having to continue being a superhero even though her friends are dead)

How far I’ll go (her first becoming a superhero)

Last kiss (Kon’s death)

She used to be mine (her thinking back to what she was before she became a superhero)

My heart will go on (Kon’s death)

Eleanor rigby (her being alone after everyone died and she betrayed Tim)

Womanizer (Conner before they started dating)

Devil town (it gives me YJ vibes)

Yesterday (missing when things were simple)

No scrubs (not liking Conner before they started dating)

Two birds (her and Tim being the last ones left and her staying on the wire)

Sober up (her and Tim’s mistaken dating after everyone died)

I hope you like this new playlist!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

SPEAKING of playlist analysis! Here is my Meta Knight playlist, my favoritest playlist, my pride and joy-

Plus all of the explanations and meanings and stuff under the cut, in case you wanna go in blind first ouo!!

This Will Be The Day: This is Meta Knight joining the GSA and meeting Jecra and Garlude and stuff! He's young and reckless and doesn't yet realize just how serious and dire the war is- So this song is a pure representation of Meta’s current outlook! This is an adventure, a challenge, a revolution, an epic anime fight scene just waiting to happen! And the mention of fairytales and legends refers to Arthur and the knights (Falspar, Dragato, and Nonsurat) and how Meta idolizes them!

Eleanor Rigby (feat. Dream Jumpscare): OHOHOHOHO THIS ONE- And here the bright outlook is shattered as the reality of war sets in!! This one has the most animatic ideas bouncing around- Basically Jecra’s been missing for weeks but he comes back possessed, ambushing a GSA camp in the middle of the night and Meta’s forced to kill him-

AAAAAUGHH THESE LINES THIS IS JECRA AND META KNIGHT IT’S LITERALLY THEM- THE GSA NEVER HELD A FUNERAL FOR JECRA BC HE WAS POSSESSED AND THERE WAS THIS UNSPOKEN WARINESS ABOUT IT- SO META HAD TO DIG HIS GRAVE AND OUGHHHHH AGONIES

And that part at the end where the music slowly builds up is Meta alone on a rocky ledge (the whole thing takes place in like a mesa desert) looking through a journal with photos of him and Jecra- Tears fall onto the pages and it just cuts to him with his mask off just crying as the sun rises over the horizon-

Experience: The fall of the GSA. It becomes more and more obvious that this is a fight they just can’t win. Meta’s forced to watch as ships crash and troops are obliterated around him. Just utter destruction as the few survivors left are scattered across the galaxy. It’s over… What do we do now?

Hush: The start of Meta’s crew, and maybe also his plans to take over Dreamland? Super intimidating, almost secret society vibes as the group grows and they begin construction of the Halberd. This one reminds me of Smash Bros Meta Knight’s almost regal aesthetic with the frilled cape and the detailed armor- I imagine the ending is the crew taking in a young Sailor Dee, like they’re trying to be comforting but it just comes off as menacing lol-

Settle It With a Swordfight: Tonal whiplash time! The other side of Meta's crew and a representation of Revenge of Meta Knight!! Note the more energetic electronic vibe and the guitar, as a callback to the first song and representing Meta’s readiness for a challenge!

Take Off: Meta learning to Chill Out after Revenge of MK, just being with his crew bc the Knightmares are a FAMILY and they LIVE ON THE HALBERD together and they do KARAOKE ON FRIDAYS

Awoken: META KNIGHT IN PLANET ROBOBOT- Both the effects of getting cyborg-ified and all of the guilt and angst involved, and breaking out of it through sheer willpower and Kirby's help! It's very electronic but there's no guitar, like trying to emulate Meta Knight's power but it's noticeably forced and artificial

Pain: OK I KNOW THIS IS LIKE. THE EDGY SONG EVER. But the way I saw it, it represents Meta Knight's will to fight and struggle and improve and keep going and live! There's the full on heavy guitar this time, just the very essence of those burning feelings!! I imagine the "take my hand" parts are him in the New World saving a Waddle Dee from an abandoned building full of beasts

Sword of the Surviving Guardian: Ok this theme was just too much of a bop not to include- But it also shows just how far Meta Knight’s come! As a warrior, as a friend, as a legend. This is a testament to his growth and a toast to his future!

Legends Never Die: OK I ALWAYS IMAGINE THIS SONG IN 3 PARTS FOR EACH CHORUS AND EACH GENERATION; Arthur and his knights (plus Galacta Knight), Meta Knight, and Kirby with the Ultra Sword- OUGHHH it’s so cool and gives me chills every time- Legacies written in the stars and the immortal call of heroism, to protect and persevere and stand up for what’s right

AND THAT'S IT :D The autism was STRONG when I made this as you can probably tell lmao- But for real, I'm extremely proud of this! It tells Meta Knight's story through the music, every song plays a role, I even took the instruments into account, it's great ouo!!

#also yes i know there's a dsmp animatic and a fansong in there- i made this playlist a long while ago akdhfksldf#kirby#meta knight#character playlist#my nonsense#losing it over songs tag <3

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watching a playthrough of Battle Network 1 (I'm gonna start with 2 once I have the free time to dig into Legacy Collection b/c I've heard 1's gameplay is janky) and a few thoughts so far:

That's so goofy that Dr. Froid's son is a total rando in the game but a major secondary character in the anime

I love how Chaud tells Lan his name and then later has the nerve to be like "Who are you and how do you know my name" like gee Idk it's not like you said it in front of him or anything, Eugene

I thought "Load Chaud" was just a one-time misspelling, does Protoman really call him that the entire game???

Wow Ms. Yuri is really different, I kinda prefer what the anime does with her even tho I haven't gotten that far

I BURST OUT LAUGHING B/C I WASN'T EXPECTING THE CARS TO JUST EXPLODE AND DISAPPEAR WHEN THEY CRASH INTO EACH OTHER THAT'S SOME REGULAR SHOW SHIT (I can hear Benson yelling at Mordecai and Rigby to delete ColorMan and stop the traffic accidents or they're fired)

#mmbn1#<- Idk if I'm gonna keep posting as I go or not so just in case this is for blacklisting if you don't want your dash overloaded with this

0 notes

Photo

Broke into her dad’s room to use his chess table

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

a day in the life of the potts family 🤍

#bird tw#ts4#ts4 gameplay#*potts legacy#*potts:one#*beatrice#*rhett#*bennett#*rigby#*landon#*inez#rhett and bennett are twins lol#i really miss this family so i was so happy to play them again but....#im going to take a step back from them for a bit bc i have no time!!!!!!!!#these next two months are the busiest for me so...see you in 2022 potts fam!!#thats so weird thats a real year

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A high pitched voice broke Everly out of her reverie.

“You! You there! Are you a human? Ohmygosh, a human!!” The voice could only be described as chittery. Much like a squirrel would sound like if it could talk. Fast and high and cute and probably annoying if around it all day.

“Oh hello, I’m Everly--” but before she could finish, she felt arms pulled tight around her.

“I just knew something good would happen today! I felt the excitement in the air. I told Eugene, but he didn’t believe me, since he never does, but boy oh boy, is he going to feel foolish now!” the squirrel-voiced being continued, still not letting go of Everly.

before / beginning / next

#ts4#ts4 challenge#ts4 legacy#ts4 legacy challenge#ts4 gameplay#ts4 story#dpchallenge#dpgen1#everly#rigby

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul McCartney

The riddle of the sources for Paul McCartney’s musical genius actually poses a greater problem than in the case of John Lennon. While Lennon had a manifest flair for exposing himself and his own contradictions, Paul has a gift for concealment and a desire to lend a controlled appearance to the tensions in his life. This has perennially earned him a reputation as smooth diplomat and skilled PR man. But such appearances are partially deceptive and they collide forcibly with the facts. Paul is no self-effacing second stringer and he did more than “carry that weight” in their partnership. The point is that Paul’s talents provided the ideal, complementary foil to John’s, even when they were working apart. Not only did they learn their composer’s trade as taskmaster to the other from 1957 onwards, but they continued to influence and rival each other throughout the Beatle years, and even after the break-up when their songs sometimes became open letters of mutual recrimination. Indeed, relatively speaking, the credit for the absolute Beatle smashes (such as “Yesterday,” “Hey Jude,” “Eleanor Rigby,” “Let It Be,” or “Michell” in their countless cover versions) belongs to Paul as the sole author or main collaborator (Schaffner 1978, 214).

My main purpose in reviewing the facts of Paul’s life is, again, not biographical in the conventional sense, but an attempt to come to grips with the mystery of his muse. It must be clear that the complementarity of his work with John corresponded to some kind of temperamental harmony as well. In what did this consist? What kind of a teenager had Paul become, at least for a moment in time, to allow “the perfect hand to find the perfect glove?” If John displayed a perverse structure (as I have argued), then what kind of structure did Paul’s personality obey to produce some kind of compatible fit? John’s posthumous canonization as the patron saint of the baby boom generation, as well, as the stormy 1988 controversy over John’s legacy and memory, have tended to obscure Paul’s specificity as a person. This not only retrospectively skews the genesis and development of the Beatles, it also prevents us from taking a deeper look into the second well out of which the group’s genius flowed.

The primary enigma about Paul is his much self-advertised “normalcy.” But normal people do not conquer the pop world twice over, as a Beatle in the 1960s, and with Wings in the 1970s. Nor do they go on to become the most successful songwriter in history and accumulate a fortune commonly estimated to be worth over $600 million. “In terms of sales of single records,” according to the Guinness Book of World Records (1986), “between 1962 and January 1, 1978, he wrote jointly or solo 42 songs which sold one million or more records” (Flippo 1988, x). Paul’s normalcy is a myth for public consumption, just as John’s various poses were. I believe the truth about any artistic genius is otherwise. In Lacanian terms, his upbringing and entire career proclaim the structure of obsessional neurosis, with the kicker that lyric effusion has been his strange salvation from the suffocating effects of this obsession. To vindicate such a thesis, we must now return to the events preceding his birth in Liverpool.

Kinship Structure Prior to 1942

James Paul McCartney was born in Walton Hospital at 107 Rice Lane on June 18, 1942, the first son of James McCartney and Mary Patricia (née Mohin). His father Jim (1902-1976) had been one of nine children born to Joseph and Florence McCartney. Old Joe McCartney worked as a tobacco cutter for the firm of Cope’s and had been born in Everton in 1866. His father before him was James McCartney II, a journeyman painter and plumber who hailed either from Liverpool or Ireland. His father in turn, also called James McCartney, had been an upholsterer, but his origins in Ireland remain obscure. Paul’s social background, therefore, belonged in that shadowy area of the British class structure between the working class and the lower middle class. It was his mother’s ambition and career as a health care professional that enabled the family to escape into the relative security of the middle class proper. But there was an emotional price to pay in the family structure for the material advantages accruing to this precocious dual-career couple.

“Mary’s money” became a dominant signifier in the McCartney family. Jim had gone to work at fourteen as a sample boy for the cotton firm of A. Hannay & Co. at the rate of six shillings a week. This was at a time (1916) when the Liverpool Cotton Exchange was still a major international force in the industry, and eventually Jim rose to the rank of salesman at the substantial salary of five pounds a week. This advance was unusual for one of his modest beginnings, and the promotion gave him a sense of pride, while it also rendered him a very eligible bachelor. He married Mary Mohin at a Catholic ceremony in Gill Moss, Liverpool on April 15, 1941. The war, however, was to bring a steady, but unavoidable decline in his fortunes.

In the first place, the outbreak of hostilities led to the closing of the Cotton Exchange, and Jim was too old for military service. So he was went to work at Napier’s aircraft factory as a lathe-turner. While this was a step down to manual labor, the patriotic work did form part of the war effort, and Jim also spent his nights as a fire warden trying to deal with the conflagrations caused by the stubborn Nazi bombing of the seaport. But by 1943, Jim was transferred again as an inspector for the Liverpool Corporation Cleansing Department. This positively demeaning temporary work required him to check on how well the city garbage crews were disposing of their smelly loads. It had no aura of patriotic service about it, and, worse still, the pay was poor. For one who had come so far, given his lowly background, this reversal was a source of shame. In consequence, Mother Mary resumed her job as a health visitor. Her pay was actually better than Jim’s, and this situation did not mend even when the Cotton Exchange resumed business after the war. The world financial picture had also permanently altered, so Jim rarely brought home more than six pounds a week, little more than his pre-war wage. The proud man had, therefore, to swallow the pain of knowing that his contribution to their weekly budget was the same as his wife’s and that she made their comfortable home possible.

While households with two incomes have become a norm in our present day, and relatively few husbands now forbid their wives to work outside the home for the sake of their own masculine pride, such households were rare in Britain in the mid-1940s. The prospect shook up popular perception of “natural” sexual roles. And the matter of perception is what is at stake for a consideration of the McCartney family. There can be no doubt that Jim loved his wife dearly, long after her death in 1956. But Paul was the apple of her eye. The facts behind this nexus give the clue to Paul’s obsessional structure.

Though not given to great maternal displays of affection and love, Mary was typical of many women in her assumption that – out there in the world – there must be “at least one real man” (Lacan 1973b; 1987). This essentially feminine, waiting, position recognizes that most men are not really “the one,” but hope springs eternal in the consolation that the Prince is somewhere and that she will eventually meet him. Doubtless, it may have seemed to her in 1941 that Jim was this “one.” But his declining status as a provider made her feel that he was inadequate. She esteemed him less after Paul’s birth in 1942. The message the mother henceforth gave her children in this family structure posited that the model of their father was not worth very much. They must, therefore, take the mother as model, a masculine feminine. In her desire to be an adequate provider and leader, Mary actually sent her son a message of guilt. The little boy accepted the proposition of Daddy’s inadequacy, and took the burden of his father’s assumed guilt (in his mother’s eyes) onto his own shoulders. To repay such an emotional debt, the obsessional son usually concretizes this around converting the debt into money that is owed or outstanding. Paul has regretted his notorious outburst on learning of his mother’s fatal illness, both then and since. But it illustrated the truth of the foregoing remarks: “What are we going to do without her money?” (Flippo 1988, 16).

For Lacan, the obsessional male is a subject who is overidentified with his mother and the feminine. The son must make up to his mother for the failures of a denigrated father/husband who let her down; for what he – in her estimation – did not give her. But while the son henceforth carries the burden of paying someone else’s debts, he feels angry about it. Such a feeling may add some new consistency to the lines Paul wrote for “Carry That Weight” on Side Two of the Abbey Road album, where the boy who is going to carry the weight for so long could literally be himself. The ringing echo of this childhood burden is what frames the obsessional’s characteristic life question: “Am I alive or dead?” Am I alive to the specific impulses of the here and now and free to respond to them? Or am I a slave being spoken by the dead letters of a remote infancy from the place of the Other (Freud’s anderer Schauplatz)? Much in Paul’s behavior towards his father over time makes better sense if we pursue such a line of argument. This can best be shown, oddly, in light of the signifier for horses in the McCartney and Mohin clans.

Horses made and wrecked the fortune of Mary’s father, Owen Mohin, an Irishman from Co. Monaghan, who had emigrated to Glasgow in 1892 and then to Liverpool in 1905. Mary was the second of three children, and her own mother, Mary Teresa Danher, died in childbirth in 1919. Owen then returned to Ireland with his family, but, after a failed attempt at farming, set himself up as a coal-merchant in Liverpool and prospered. Not only did he own five delivery carts, he used his rigs in the summer months for moving households as well. Things went so well for him that, at one point, he owned four race horses. But gambling proved an irresistible addiction to him and he eventually lost everything. It was while on a trip to Ireland in 1921 to buy horses that he met Rose, his second wife. When he returned to Liverpool with his new bride, it transpired that Rose and his twelve-year-old Mary could not endure each other, so Mary moved away to live with her mother’s kinfolk and became a trainee nurse at Alder Hey Hospital.

It must have been with some dread that Mary contemplated her husband Jim’s fondness for betting on horses. It was one of few weaknesses he displayed in a disciplined and honest nature. Her own father had worked himself up from obscurity, grown comfortable, and then slid back into poverty. In what must have been a milder, but gruelling repetition of history, her husband’s career described the same trajectory. But, intriguingly in the light of our comments above, Jim’s major setback with horses was linked to an attempt to make up to his own mother, Florrie McCartney, for what she had never in her own life received from her husband Joe: a real summer vacation. Jim’s plan was to send her to Devon for several days. The gamble failed, however, and his bookies reported the debts to his employer, Mr. Hannay. In view of the circumstances, his employer generously picked up the tab and also advanced the money for Florrie’s holiday. But their arrangement was that the debts be repaid on a strict schedule over one year. Thereafter, Jim walked the five miles to work every day to economize on bus fares, a kind of protracted penance for his ill-conceived trust in the racetrack to assuage his mother’s sorrows.

Now Paul’s career can be construed in one fashion as a massive attempt to make good on his father’s debts. According to Pete Best, Paul was always the stingiest of the Beatles, and he became by far the wealthiest. But when Paul had just turned the corner financially, he made a strange gesture to his father. At the reception for A Hard Day’s Night held at the Dorchester Hotel on July 6, 1964, Paul presented his father with a gift for his sixty-second birthday (which occurred on the following day). It was a painting of a horse. Jim felt confused, thinking: “It’s very nice, but couldn’t he have done a bit better than that?” Then Paul revealed that the painting was of Drake’s Drum, a racehorse that he had bought for him at a cost of £1,050. Paul said: “My father likes a flutter [bet]. He’s one of the world’s greatest armchair punters” (Salewicz 1986a, 167-68) An “armchair punter” is one who talks, but does not act. Paul was also indirectly saying to him: “Here is your weakness. This is the symbol of your debts, which I am unconsciously bound to pay.”

Finally, it is worth noting that Paul himself has become an accomplished horseman. On his Waterfalls estate outside Rye in Sussex, Paul keeps several horses amidst his huge menagerie. There is a photograph of him at the end of Gambaccini’s memoir, waving his left arm astride a handsome nag, fetlock-deep in a stream (1983, 112). His stable forms part of his daily ritual. “Like a typical working-class Northern man, Paul expects Linda to rise early and cook his breakfast and get the kids off to school while Paul feeds and waters and exercises his horses before traveling up to London by train or car” (Salewicz 1986a, 247). Though riding and wealth commonly reflect each other in England, Paul’s ownership of horses obviously continues a long-established pattern in the weave of the McCartney-Mohin family myth. Even the betting mentality of the British lower class shows an obsession with getting into the money associated with the upper class via horses.

As regards Paul’s ambiguity towards his father, it can be seen again in the gift he made to Jim of a five-roomed detached house called Rembrandt in Baskervyle Road, Heswall in Cheshire. He also invited his father to quit his low-paying job as a cotton salesman, which Jim gladly did. In subsequent years, however, according to the arguably biased account of Angela, Jim’s second wife, in a London Sun exposé, Jim was financially hard pressed to keep the house up. He urged Angela to say nothing, but to pretend that his crippling arthritis made it hard for him to climb stairs. Paul then bought the house back from his father, and the aging man moved into his final home, a bungalow in Heswall. Despite his ailing condition, however, when Angela and Jim visited Paul and Linda at their farm, they were obliged to sleep on mattresses on the garage floor. Conversely, when Paul and Linda visited them, they raided the freezer without paying for what they ate (despite a housekeeping allowance of only twenty pounds a week), while Linda had her groceries sent up by train from Fortnum and Mason’s in London (Flippo 1988, 343).

Angela doubtless tried to injure Paul and Linda out of spite by these revelations. But one might argue that they do not attest to planned cruelty, so much as to the unconscious power of the signifier for money in the McCartney family, even in the midst of abundance. It was this signifier in Paul’s Other that did the talking. The most stunning example of how much a wealthy couple can still feel poor, or unconsciously still at risk, came in a 1985 interview. Talking to Diane de Dubovay for Playgirl magazine, Paul remarked that: “My dad never told my mum how much he earned. Linda still doesn’t know [how much I earn]. You could never convince me that I had earned enough” (February 1985, 104). Then he fantasized his wealth might disappear in a left-wing coup: “I work, and a friend of mine explained to me that if there were a communist takeover they might take it all away.” At this, Linda panicked, and Paul reassured her: “Don’t worry Lin. I’ve checked it out. They can’t.” Linda, for her part, denied that Paul could be earning as many millions as reported, and added: “My philosophy about money is that as long as we have enough to live on, with a little extra in the bank, we don’t need any more” (Playgirl, February 1985, 104).

The Early Sources of Paul’s Creativity

Two key events in Paul’s early life turned him towards charming and entertaining strangers through the medium of music: the birth of his younger brother, Mike, in 1944 and the death of his mother in 1956. Peter Michael McCartney was born on January 7, 1944 in the same Walton Hospital ward where his elder brother had seen the light of day. Now while the concept of sibling rivalry has been fairly well defined in recent times, this version of the event was especially charged for little Paul. In the first place, the rival was a same-sex child – another male to compete for their mother’s fond gaze. Mary seems to have been careful of Mike’s welfare, sticking up for the underdog, but never relinquished the preference for her first-born son. Mike, for his part, formed an ineradicable bond with his mother, and his ever-fresh tears over his mother’s “passing” inform some of his autobiography’s most moving pages (M. McCartney 1984, 28). Mike resembled his mother physically, while Paul favored Jim. Mike grew taller and, if anything, more handsome than his angelic, “doe-eyed” elder sibling. The particular pique in the appearance of this rival for Paul, however, lay in the timing.

Lacan’s famous mirror-stage lasts from approximately six to eighteen months in early life. It is the period before the advent of coherent speech when the infant acquires the linings of a specular ego (moi). Attention is focused on the maternal figure who serves as an anchor and a nurturer. One consequence of the intervention of language at one and a half years is to teach the child limits and what Lacan called castration: an end to the illusion of omnipotence and his exclusive access to the mother. It is thus highly traumatic, one of the first, inevitable injuries of early maturation. Now, as chance would have it, Mike arrived on the scene at exactly this time: actually twenty days after the date Paul reached eighteen months.

So it is fair to say that Paul suffered the trauma of castration twice over. Not only was he dethroned from the place of privilege with his mother, as most small children are, but this place was instantly assumed by an infant who usurped the role of “king baby” (Freud) that had previously been Paul’s. Paul therefore attempted to turn in his own direction “those unexpected torrential floods of pure love that poured the way of the newly born child” (Salewicz 1986, 19). He learned the art of charm, how to win back by personable efforts and skill the status and affection that he had lost to his new rival. He acquired the knack, in the act of beginning to speak, of reaching out to friends and neighbors to regain the position suddenly denied him in the family’s enlarged structure. This skill has characterized Paul McCartney’s public demeanor throughout his career.

As is normal in sibling relationships, Paul also showed ambiguity towards his younger brother. He was protective of him in school, and came to his aid if he was bullied by older boys. On the other hand, his unconscious resentment of Michael sometimes took a terrifying turn. One afternoon, the boys found a can of gasoline in the garage at their Uncle Harry’s Huyton home. They bet each other that the gasoline would or would not burn up the wall behind the garage, and Paul bet Mike a bag of marbles that it would not. Having egged him on, Paul then let Mike climb onto the garage roof and set fire to the trail of gas. The flames were so fierce that Mike was trapped on the roof and could not climb down. A passing police constable saved the situation. On another occasion, Paul – as was his wont – picked Mike up by his ankles and swung him round. Paul “lost” his grip and Mike hit the concrete, losing his two baby eye teeth in the process.

A more serious accident that happened at Paul’s instigation took place at a Derbyshire scout camp in 1957. The scouts rigged up a pulley system for hauling logs up a cliff for camp fires. Paul then suggested to his brother that they see if Mike could be lowered down the cliff in the same manner. Paul then became worried at the speed of his descent and the scouts tried pulling on a rope to slow him down. They pulled the wrong one, and Mike plunged down the cliff, smashing into an oak tree and fracturing his left arm severely in three places. Mike then spent several weeks recuperating at the Sheffield Infirmary, where he was visited loyally by Paul every day. All three of these “accidents” involved a bungled performance (Freudian slips or Fehlleistungen), in which the “mistake” was the unconsciously intended action.

This is all to say that Mother Mary’s total attention mattered very much to Paul. Her death from breast cancer in 1956 was indisputably the most important event in Paul’s young life, since, in seeking solace for his grief, he turned to music and the guitar. Mike wrote much later on: “Mum’s death affected us more than we’ll ever know. Without knowing what a soul was, her death touched it, reaching right down to the bottom of my heart. I was twelve and Paul was just fourteen” (1984, 28). Mary had ignored severe pain symptoms and a breast tumor as simple signs of menopause as late as August of that year, and was in unspeakable agony before she would seek medical attention. By the time she was admitted to Liverpool’s Northern Hospital, the cancer had metastasized so completely that she died within hours, on October 31, after receiving the last rites of the Catholic Church. But this death was not a random event. In view of its undoubted centrality to Paul’s subsequent career, we should try to understand its aetiology within the family kinship structure. For one thing, it thrust Paul in contact with the Real of loss and made death a possible theme in songs he would write with the Beatles. More importantly still, the chain of causality in Mary’s death tells us a lot about the woman who was Paul’s mother.

That the breast was the “selected organ” for Mary Mohin – a vital part to which a signifier, the signifier for death, had become attached – might have been guessed at when she gave birth to Michael in 1944. After the delivery, she was readmitted to Walton Hospital with mastitis, an inflammation of the breast caused by infection. We do not know from existing printed sources which of the dozen or so varieties of mastitis afflicted her. Plasma cell mastitis, for example, is a condition characterized by tumor-like new growth of these cells, but the tumors are not malignant. By taking a long step backward and looking at her life as a while, however, it seems clear that nursing, the breast, and life and death were an intricately dependent nexus for her.

Some of Jacques Lacan’s followers, notably Jean Guir, have argued for a psychosomatic origin to cancer, and have found support for their theories in Lacan’s teaching. Specifically, a psychosomatic subject must have experienced a bitter separation in early life, repress rage and anger very strongly, live through another loss or separation in later years, unconsciously fail to marshall the immune defense system in the face of this new blow, and thus leave some vital organ defenseless against the presence of a suitable carcinogen. The disease then develops in the organ around which some identity theme, or life theme, has become unconsciously woven (Guir 1983, 61). Mary Mohin, as we know, lost her own mother as a little girl of ten. This was the “bitter loss” in early age which, significantly, occurred in childbirth. Her mother gave birth to Wilf, Mary, Agnes (who died at the age of two), Bill, and the baby who died with Mrs. Mohin in January, 1919. In other words, Mary’s mother died when she was nine months pregnant, and just prior to lactation.

At about thirteen, Mary Mohin left her own household because she resented her stepmother’s arrival, and chose to become, precisely, a “nurse.” Now this was a common career choice in England for single girls of Irish descent (it still is), but Mary’s choice was already heavily invested with symbolism. A nurse tried to save life. Moreover, it is only in English that the etymological crux on breast feeding and attending the sick exists. The terms in German (Krankenschwester) or French and Spanish (infirmière, enfermera) refer only to illness. Nurse is from the Latin nutrix, a woman who suckled or nourishes an infant, and the English term originally meant a wet-nurse specifically. It is hard not to connect the death of Mary’s mother, pregnant and preparing to “nurse” a new infant, and Mary’s rejection of a substitute mother in favor of “nursing” others.

Second, Mary trained hard and rose to the rank of hospital sister before her marriage. When the straitened financial situation in their home forced her to resume work, Mary turned to health visiting, but the office-like routine made it seem dull compared with nursing. Mary then decided to become, and this is crucial to the story, a district or domiciliary midwife. Her work on a housing estate obliged her to attend pregnant women before and after childbirth, but also to get up at all hours of the night to assist in the actual delivery. This was selfless and yeoman service for which the community praised her, but it placed Mary constantly in the vicarious position of saving her own mother and dead sibling from dying. The bout with mastitis in 1944 showed that a psychosomatic deterioration had afflicted one of her breasts already, and a cancerous lesion must have developed in the following decade. The key second loss was probably her sense of grief at seeing her husband go down in the world, seemingly repeating her own father’s shame and ruin. She then walked straight into the world of midwifery, whose signifying links were life, livelihood, and her own death by refusing to attend to her own pain.

Paul was, therefore, the son of a woman who repressed and denied her own pain, even when it shrieked through her body. She was a stoical, unsmiling woman (as all the extant photos make clear), whose exemplary nurture and domestic discipline made for a salubrious and comfortable home. Paul would rank her homemaking characteristics the test sine qua non in any prospective bride of his own, as we shall see. But, above all, she concealed her intimate feelings and sought to flee her demons in a gruelling regime of work. Denny Laine of Wings was probably closer to Paul than any other male friend throughout the 1970s, playing, talking and getting stoned with Paul countless times. But Laine reported: “[Paul] is the best person I have met in all my life at hiding his innermost feelings” (Flippo 1988, 361). Paul is in this his mother’s son.

But Paul was his father’s son when it came to his early exposure to music in the family. In the 1920s, Jim McCartney had been the leader of a semi-professional combo known as Jim Mac’s Jazz Band. He had a serviceable piano technique, and their repertoire was mostly ragtime and vaudeville. He also composed a number entitled “(Walking in the Park with) Eloise,” which Paul recorded pseudonymously with the “Country Hams” in 1974 (EMI 3977). Jim had taught himself chords and musical notation at the encouragement of his own father, Joe, who played a big tuba in the Territorial Army’s brass band, as well as in one sponsored by his tobacco firm at Cope’s. Old Joe, moreover, had a fine singing voice, such that during the 1920s their parlor, or sometimes the street outside, was full of communal music.

At first, Jim tried to encourage Paul to take up the trumpet. This did not suit Paul’s “deposed sibling” concept of being the focus of attention as the singer, however, and it was his mother’s death that drove Paul into an obsessive absorption with the guitar. It became his therapeutic salvation. Curiously though, despite the fact that Paul plays piano and drums with the normal fingering, he found the guitar awkward at first. Soon he realized that he was left-handed, and he restrung the instrument, holding the neck in his right hand and striking the strings with his left. This gave Paul a symmetrical look as a Beatle, his Hofner violin bass pointing in the opposite direction to John’s three-quarter size Rickenbacker. Since Paul’s left-handedness on guitar is the first of his few overt idiosyncrasies, we may wonder if it fills in our analytic picture in any way.

Many languages have strongly negative connotations for the left hand: sinister in Latin, gauche in French, “cack-handed” in English. The Spaniards actually borrowed the Basque word izquierda to avoid the Latin tradition. But these grim meanings are perhaps best grasped by looking at the etymologies for the right hand. The Western languages connect it with Law: Recht in German means both “right” and “law,” similarly French and Spanish (droit, derecho), Latin (rectus = correct, rectitude), or Greek (orthos = straight, right). Thus, arbitrarily from the biological point of view, the right hand symbolized the Law of the Name-of-the-Father and the left is its opposite, its sinister subversion or denigration. The bar sinister in heraldry, for example, refers to bastards born outside the law with respect to the Father’s Name.

Inasmuch as it was Paul’s obsessional desire to be what his father was not or did not become – a band-leader, a professional musician, a composer – he far outstripped him (Salinas Rosés 1988, 26-32). He did it by setting himself against him, by going against the “straight” model that the mother had underesteemed. He subverted his father by assuming the “left” stance to beat him at his own game. Paul may have imagined their antagonism was mutual, since he blurted out to Hunter Davies in 1981 (when both Jim and John were dead): “I realize now [John and I] never got to the bottom of each other’s souls. We didn’t know the truth. Some fathers turn out to hate their sons. You never know” (1985, 372). In the emotion-laden context, this apparent non sequitur jumps at one like a Freudian slip. As a boy, after being punished by his father for swimming in an off-limits lime pit, Paul sniffed to Mike that he was going to dig a big hole and fill it full or water and, then, take their Dad up in an airplane and push him out and into the big hole (Flippo 1988, 13). While Jim may have resented Mary’s fondness for Paul and her quiet disappointment with him, any perceived hatred of father for son and fantasized parricide belong to Paul, not to his father. Becoming a better musician than his father “the other way around” was a sublimation of these feelings.

At least as important here is the maternal component: the left-handed guitar gave Paul the emotional sustenance to struggle through the mourning period. But the instrument was also a musical stand-in for the lost love-object. It stood for the Real of the feminine support that was gone. The guitar said implicitly: “Mother’s left.” But this “left” could also be expressed in the holding of the instrument’s body on the left of Paul’s own body, a signifier which the English language readily supplies. So, in typically overdetermined fashion, Paul’s southpaw stance on bass is the living expression of the emotional coordinates by which he came to his favorite instrument.

The ”Psychomusical Matrimony” with John Lennon, 1957-1968

It is now time to look at the famous Lennon-McCartney partnership from Paul’s point of view. They met, as we know, on July 6, 1957 at Woolton fête, some eight months after Paul’s bereavement. Apart from the obvious technical admiration John felt towards the younger boy and Paul’s wonder at someone outrageous enough to go and form a skiffle group, the question arises for our argument: how would a rather typical obsessional find his soulmate in someone perverse? We have set out the various reasons why John felt drawn to Paul. What was happening emotionally on Paul’s side? How could the two desire structures dovetail?

Up to this time, Paul had been a hardworking and dutiful grammar-school boy. He was one of only four out of ninety pupils at his Joseph Williams elementary school to pass the notorious eleven-plus examination that got him into the Liverpool Institute. At age sixteen, he went on to pass seven subjects in the “O-level” GCE (the equivalent of the US high-school diploma, but awarded on the basis of nationwide competition), including Latin, Spanish and German. Considered capable of a career as a university professor by his teachers, he formed a dramatic contrast to the academic disaster that was John Lennon. For a disciplined “keenie” like Paul, therefore, John acted like a nuclear bomb. He gave Paul flagrant subversion and craziness, the excitement to dismantle conventions and find the courage to go with his creative desire. He shook up Paul’s assumed horizon of what was possible, injecting pain, mordant wit and searching wistfulness into Paul’s practiced optimism. Later on, John abolished all sense of harmonic and melodic rules in their compositional experiments together, because he knew few rules and cared little about any rules. John, in a word, gave the bourgeois Paul the major thing he lacked in his Other: a taste for risk.

Most of all, John’s outrageousness permitted Paul’s obsessional nature a kind of moral vacation. When you are inwardly bound to slave in the payment of another’s debts, to work in the alleviation of the (now dead) mother’s sorrows and the duty to surpass the father’s inadequacy, the arena of negotiating desire – your own and other people’s – becomes a problem. John’s example was now like a whiff oxygen to a potentially suffocating soul. John afforded Paul a freedom he had never known in this degree. Soon, to his father’s consternation, Paul abandoned academics and began to follow his own star. John, indeed, horrified Jim McCartney by his dress, his manners and Teddy Boy (i.e. juvenile delinquent) flamboyance. Jim warned his two sons: “Be careful of that John Lennon. He could get you into trouble” (Coleman 1985, 86). But, in a way, “trouble” injected into an over-rigid disposition was what Paul needed.

Then, in a tragic way, Fate bonded them even more indissolubly. A year after they met, on July 15, 1958, Julia Lennon was just walking away from Mimi’s house to a bus-stop. She had been rowing with Bobby Dykins and seeking her sister’s advice. At that moment, a drunken off-duty policeman, who was a novice driver, saw her crossing Menlove Avenue and braked to avoid her, hitting the accelerator pedal instead. He plowed into Julia with tremendous force. She flew into the air, came down inert on the pavement, and never recovered consciousness. She died in the ambulance on the way to Sefton General Hospital.

John thus lost his mother twice over, to her early abandonment of him and to death. This final blow wrecked him emotionally. Of all people in the world to whom he did not need to explain his feelings, it was Paul. They did not really discuss it much; it was scarcely necessary. But now they both shared an ineffable horror. Both of them sought in music and the guitar to hang on to the One woman who was gone. Their lyricism – song in dialogue with the maternal Other within – became charged with a special urgency, and in the next two years they wrote nearly a hundred songs together. Later, they each penned a masterpiece to a vanished mother, John in “Julia” and Paul in “Let It Be.”

An obsessional always needs a leader, and a leader needs a right-hand man. Since Paul lacked a worthy signifier for a Father’s Name, that “position” was vacant in his unconscious, just waiting to be filled. He also worked hard to displace the rivals for position of second-in-command to John. First, in the early Quarrymen days, he engineered the ouster of Nigel Griffiths on rhythm guitar, a role Paul himself then supplied. In the Beatles of the Hamburg vintage, Paul deplored Stu Sutcliffe’s lack of technique on bass, while John defended his art-school protégé zealously. But Paul antagonized and bullied Stu to such a degree that, when Astrid and a painter’s career beckoned, Stu was happy to relinquish the bassist’s slot to his superior, Paul. Finally, in 1962, John and George had little difficulty agreeing with Paul that Pete Best had to be sacrificed to secure a fully professional quarter. When John’s use of LSD incapacitated him in 1966-67, Paul effectively assumed the artistic direction of the Beatles. In view of his Machiavellian manner of raising the band’s quality, it is probably fair to say that, without Paul, the Beatles would never have made it.

Paul’s Sexual Attitudes Towards Women

There is no better insight into a man’s character than that afforded by the way he treats women. Paul said of his teenage years that all he wanted was “women, money and clothes” (Flippo 1988, 21). In the orgiastic days of the Beatle tours – from Hamburg to Candlestick Park in 1966 – Paul was sexually as voracious as John and the other two. The most eloquent account of their enthusiastic post-concert girl-swapping is Pete Best’s (Best & Doncaster 1985, 49-56). But the only visible consequence of these experiences for Paul was an unproven paternity suit brought against him later by a German girl called Erika Heubers.

Paul’s first serious love relationship as a young man of marriageable age was with the talented actress, Jane Asher. Her family was “taken” enough with Paul to invite him to live at their London home. Paul McCartney and Jane Asher formed one of the fairyland couples of Swinging London in the ‘Sixties, and they were engaged to be wed. In July 1968, Jane discovered Paul with another woman at the 7 Cavendish Avenue house she and Paul decorated together and shared. Her mother arrived the same night to remove her daughter’s belongings, and the engagement was over. John and Yoko were together by now (May 1968). Paul’s despair over this seemed to outweigh his attachment to Jane. In any case, his reaction to the broken ties with Jane and John manifested itself in heavy drinking bouts, the use of hash, “uppers” and so on.