#leonor de guzmán

Text

The Bastard Kings and their families

This is series of posts are complementary to this historical parallels post from the JON SNOW FORTNIGHT EVENT, and it's purpouse to discover the lives of medieval bastard kings, and the following posts are meant to collect portraits of those kings and their close relatives.

In many cases it's difficult to find contemporary art of their period, so some of the portrayals are subsequent.

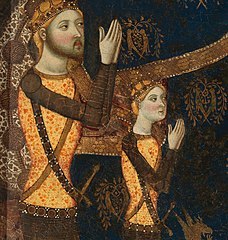

1) Henry II of Castile ( 1334 – 1379), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán; and his son with Juana Manuel de Villena, John I of Castile (1358 – 1390)

2) His wife, Juana Manuel de Villena (1339 – 1381), daughter of Juan Manuel de Villena and his wife Blanca de la Cerda y Lara; with their daughter, Eleanor of Castile (1363 – 1415/1416)

3) His father, Alfonso XI of Castile (1311 – 1350), son of Ferdinand IV of Castile and his wife Constance of Portugal

4) His mother, Leonor de Guzmán y Ponce de León (1310–1351), daughter of Pedro Núñez de Guzmán and his wife Beatriz Ponce de León

5) His brother, Tello Alfonso of Castile (1337–1370), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán

6) His brother, Sancho Alfonso of Castile (1343–1375), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán

7) Daughters in law:

I. Eleonor of Aragon (20 February 1358 – 13 August 1382), daughter of Peter IV of Aragon and his wife Eleanor of Sicily; John I of Castile's first wife

II. Beatrice of Portugal (1373 – c. 1420) daughter of Ferdinand I of Portugal and his wife Leonor Teles de Meneses; John I of Castile's second wife

Son in law:

III. Charles III of Navarre (1361 –1425), son of Charles II of Navarre and Joan of Valois; Eleanor of Castile's huband

8) His brother, Peter I of Castile (1334 – 1369), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Mary of Portugal

9) His niece, Isabella of Castile (1355 – 1392), daughter of Peter I of Castile and María de Padilla

10) His niece, Constance of Castile (1354 – 1394), daughter of Peter I of Castile and María de Padilla

#jonsnowfortnightevent2023#henry ii of castile#john i of castile#juana manuel de villena#eleanor of castile#alfonso xi of castile#leonor de guzmán#tello alfonso of castile#sancho alfonso of castile#peter i of castile#constance of castile#isabella of castile#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#day 10#echoes of the past#historical parallels#medieval bastard kings#bastard kings and their families#eleanor of aragon#beatrice of portugal#charles iii of navarre#canonjonsnow

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Las primeras poetisas en lengua castellana, de Clara Janés (ed.)

Aunque para ser poesía del Siglo de Oro tiene pocas notas explicativas, este es un libro muy recomendable si lo que se quiere es conocer escritoras poco conocidas de esa época. (En lo que respecta a mí y a mi supina ignorancia, solo conocía a cuatro de las cuarenta y cuatro poetisas aquí incluidas). Por criticarle algo, me hubiese gustado que se incluyesen menos poemas de sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (que es quien ocupa más páginas) a cambio de agregar algunos más de otras menos conocidas.

Para no hacerlo aun más largo de lo que es, de algunos poemas solo dejo un par de estrofas. Aquí van.

Leonor de la Cueva y Silva

“Ni sé si muero ni si tengo vida”

Ni sé si muero ni si tengo vida,

ni estoy en mí, ni fuera puedo hallarme,

ni en tanto olvido cuido de buscarme,

que estoy de pena y de dolor vestida.

Dame pesar el verme aborrecida

y si me quieren, doy en disgustarme;

ninguna cosa puede contentarme,

todo me enfada y deja desabrida;

ni aborrezco ni quiero ni desamo;

ni desamo ni quiero ni aborrezco,

ni vivo confiada ni celosa;

lo que desprecio a un tiempo adoro y amo;

vario portento en condición parezco,

pues que me cansa toda humana cosa.

“Todo lo pierde quien lo quiere todo”

Muestra Galicio que a Leonarda adora,

y con segura y cierta confianza

promete que en su fe no habrá mudanza,

que el ser mudable su firmeza ignora.

Mas de su amor a la segunda aurora

muda su pensamiento y su esperanza,

y sin tener del bien desconfianza,

publica que Elia sola le enamora.

Con gran fineza, aunque si bien fingida,

a Leonarda da el alma por despojos,

y luego con un falso y nuevo modo

dice que es Elia el dueño de su vida;

pues oiga un desengaño a sus antojos:

todo lo pierde quien lo quiere todo.

“Liras en la muerte de mi querido padre y señor”

Musa, detente un poco,

que si de tantos males hago suma

y en el presente toco,

no es suficiente mi grosera pluma,

que pues estoy penando,

cuanto puedo decir digo callando.

Francisca Páez de Colindres

“Sátira en Ovillejos en tiempo de Felipe IV y el Conde Duque,...”

Mirad que es mortal quien os engaña

y que saber morir es grande hazaña;

pues de solo un momento

pende el eterno premio o el tormento,

y si una vez se yerra

no hay remedio en el cielo ni en la tierra;

no es bien que en vanidades sumergidos

tengáis vuestros sentidos

sin la justa memoria

de que es un soplo toda humana gloria;

mirad que la grandeza

anda enferma de vahídos de cabeza;

advertid que es prestada

y que ayer fuisteis poco más que nada.

Catalina Clara Ramírez de Guzmán

“Retrato suyo”

Un retrato me has pedido,

y aunque es alhaja costosa

a mi recato,

por lograrte agradecido,

si he dicho que soy hermosa,

me retracto.

El carecer de belleza

con paciencia lo he llevado;

mas repara

en que ya a cansarme empieza,

y aunque lo niegue mi agrado,

me da en cara.

Pero, pues precepto ha sido,

va a un traslado reducida

mi figura,

y porque sea parecido

ha de ser cosa perdida

la pintura.

No siendo largo ni rizo,

a todos parece bien

mi cabello,

porque tiene tal hechizo,

que dicen cuantos le ven

que es bello.

Si es de azucena o de rosa

mi frente, no comprenhendo,

ni el color,

y será dificultosa

de imitar, pues no le entiendo,

yo la flor.

Y aunque las cejas en frente

viven de quien las mormura

sin recelo,

andan en traje indecente,

pues siempre está su hermosura

de mal pelo.

Los ojos se me han hundido,

y callar sus maravillas

me da enojos,

y en su ausencia me han servido

como negros dos neguillas

de ojos.

Mis mejillas desmayadas,

nunca se ve su candor,

y esto ha sido

porque son tan descuidadas

las tales, que hasta el color

han perdido.

De mi nariz he pensado

que algún azar ha tenido,

o son antojos;

pero a ello me persuado

porque siempre la he traído

entre ojos.

Viéndola siempre a caballo,

mi malicia me previene

que lo doma,

y en buena razón lo hallo,

pues aunque lengua no tiene

se va a Roma.

No hallaré falta a mi boca

aunque molesto el desdén

me lo mande,

porque el creerlo me toca,

que dicen cuantos la ven

que es cosa grande.

Pero aunque es tan acabada,

confieso que le hace agravio

un azar,

pues a los que más agrada

dicen que tiene en el labio

un lunar.

La garganta es pasadera,

y aunque no es larga, no estoy

disgustada,

pues en viéndome cualquiera

ha de confesar que soy

descollada.

Tiene el que llega a mi mano,

aunque de corta lo niega,

gran ventura,

pues llegue tarde o temprano

a sus dedos, siempre llega

a coyuntura.

Con todo, tan poco valen

aunque alegan sus querellas

no ser mancas,

que cuanto mejores salen

no habrá quien me dé por ellas

dos blancas.

Porque nada desperdicia

dicen que es corto mi talle,

y he observado

que no es talle de codicia,

pues nadie puede negalle

que es delgado.

Que el mundo le viene estrecho

su vanidad ha llegado

a presumir,

y viendo su mal derecho

más de cuatro le han cortado

de vestir.

Pues no merece mi brío

quedarse para después

ni el donaire,

ni encarezco porque es mío;

solo digo que no es

cosa de aire.

A ser célebres sospecho

que caminan mis pinceles

si me copio,

pues el retrato que he hecho

sé que no lo hiciera Apeles

tan propio.

Sin haberle obedecido,

el retrato a mi despecho

ha sido vano,

pues tú cabal lo has pedido,

y todo el retrato he hecho

de mi mano.

Y que tiene, es infalible,

algún misterio escondido,

y yo peno

por saber cómo es posible

que estando tan parecido,

no esté bueno.

Tal cual allá va esa copia,

y si me deseas ver,

yo creo

según ha salido propia,

que te ha de hacer perder

el deseo.

Y si tal efecto hace,

temo que pareceré

confiada,

y aunque no me satisface

mi trabajo, quedaré

muy pagada.

Por largo que fuese, no quise suprimir ninguna estrofa de su bonito retrato.

Cristobalina Fernández de Alarcón

“Canción amorosa”

Mil veces me imagino

gozando tu presencia en dulce gloria,

y con gozo divino

renueva el alma su pasada historia;

que con esta memoria

se engaña el pensamiento

y en parte se suspende el mal que siento.

Mas como luego veo

que es falsa imagen que cual sombra huye,

auméntase el deseo,

y ansias mortales en mi pecho influye

con que el vivir destruye;

que amor en mil maneras

me da burlando el bien, y el mal de veras.

Canción, de aquí no pases;

cese tu triste canto

que se deshace el alma en triste llanto.

Juana de Arteaga

“Alegres horas de memorias tristes”

Alegres horas de memorias tristes

que, por un breve punto que durastes,

a eterna soledad me condenastes

en pago de un contento que me distes.

Decid: ¿por qué de mí, sin mí, os partistes

sabiendo vos, sin vos, cuál me dejastes?

Y si por do venistes os tornastes,

¿por qué no al mismo punto que vinistes?

¡Cuánto fue esta venida deseada

y cuán arrebatada esta venida!

Que, en fin, la mejor hora fue menguada.

No me costastes menos que una vida:

la media en desear vuestra llegada

y la media en llorar vuestra partida.

Santa Teresa de Jesús

“Unos versos de la Santa Madre Teresa de Jesús, nacidos al fuego del amor de Dios que en sí tenía”

¡Ay! ¡Qué larga es esta vida,

qué duros estos destierros,

esta cárcel y estos hierros,

en que el alma está metida!

Solo esperar la salida

me causa un dolor tan fiero,

que muero porque no muero.

Mira que el amor es fuerte;

vida, no me seas molesta;

mira que solo te resta,

para ganarte, perderte:

venga ya la dulce muerte,

venga el morir muy ligero,

que muero porque no muero.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portrait of King Henry II of Castile (1334-1379). By José María Rodríguez de Losada.

He was the son of King Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán. In 1369 he assassinated his half-brother, Pedro I of Castile, and took the Castilian throne in his place.

#monarquia española#reyes de españa#reyes de castilla#rey de castilla#casa de trastamara#full length portrait#crown of castile#spain in the middle ages#full-length portrait#house of trastamara

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

Síguenos en Substack https://revistadehistoria.substack.com/ Lee cada día nuevos Artículos Históricos GRATIS: https://revistadehistoria.es/registro-gratuito/ Leonor de Guzmán

0 notes

Text

【人物故事】Constance of Castile, Duchess of Lancaster -流亡公主的復位夢

卡斯提爾的阿方索十一世(Alfonso XI of Castile)長期寵幸情婦萊昂諾爾古茲曼(Leonor de Guzmán)與其有多名兒女,而正宮葡萄牙的瑪麗亞(Maria of Portugal)和嫡子佩得羅(Peter(Pedro)of Castile)則遭到冷落。當阿方索十一世突然病逝,宮內的權力鬥爭,最終演變成王位爭奪戰。其中的細節,可能需要另寫一篇才能説完,但此篇容我快轉至最佩得羅遭到同父異母的兄長殺害,並篡位成恩里克二世(Henry(Enrique) II of Castile),並將佩得羅的兒子們監禁,女兒們則被圍困在卡莫納(Carmona,今西班牙安達盧西亞自治區賽維亞省的一個市鎮),直到兩年後同意她們離開...

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cuando la justicia revictimiza: la fiscal Isolina Letona, de Calca, Cuzco, no emite orden de captura contra investigado por violación sexual y la policía no puede detenerlo

Cuando la justicia revictimiza: la fiscal Isolina Letona, de Calca, Cuzco, no emite orden de captura contra investigado por violación sexual y la policía no puede detenerlo

Se trata de Renato Pazos Niño de Guzmán denunciado en 2020 por supuesta violación sexual en estado de inconsciencia de su expareja y por grabarla en vídeo, a ella y otras mujeres en igual estado. Pazos no ha concurrido a las citas para las pericias ordenadas por la fiscalía. La fiscal consigno en acta que si continuaba en rebeldía emitiría una orden de captura: no lo ha hecho

Leonor…

View On WordPress

#DefensoríadelPueblo#LeonorPérezDurand#MeToo#MIMP#MinisterioPúblico#MINJUS#teleoLeo.com#ViolenciaDeGénero#ViolenciaInstitucional#ViolenciaMachista#ViolenciaSexual

0 notes

Text

Fallida estrategia en seguridad, incrementa la violencia en el país: PAN

Fallida estrategia en seguridad, incrementa la violencia en el país: PAN #Queretaro #Politica #PAN #Seguridad #Informate

Afirma la dirigente estatal Leonor Mejía que con la detención de Ovidio Guzmán no se trata de aplaudirle o colgarle una medalla al gobierno federal, es su responsabilidad y la empiezan a realizar demasiado tarde.

Acción Nacional aspira a tener un México en paz y libre de violencia, pues hoy se camina en sentido inverso y los números del propio Secretariado Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

“…Inés Vanegas was only one of Catherine’s ladies at court who came to England and stayed. María de Salinas was the daughter of Martín de Salinas, a noble courtier to king Fernando, and Josefa Gonzales de Salas and, some suggest, perhaps related to the royal family. María was part of Catherine’s entourage from Spain but the details from 1501 to 1509 are not well known except that she attended Catherine at her coronation. Her family’s wealth and prestige made her an asset to Catherine’s court and she remained one of the queen’s closest and most loyal friends. Their friendship is well documented in the Tudor historical record, which include letters, payments and gifts, and reports of life at court from the Spanish ambassadors.

María was a very appealing bride, marrying William, eleventh lord Willoughby of Eresby, a baron and the largest landowner in Lincolnshire, on 5 June 1516 at Greenwich, probably in the chapel of the Observant Friars (Franciscans) where Catherine and Henry had married. By all accounts, María de Salinas moved fluidly from the Spanish court to the English. Her ease with the English customs and culture and family connections on the continent had important practical benefits. Her relative, Juan Adursa, a Castilian merchant in Flanders, worked with Juan Manuel, former advisor to Catherine’s brother-in-law, Archduke Philip of Burgundy, giving Catherine access to information about her sister, Juana.

Eustace Chapuys, the resident Spanish ambassador and a man privy to the secret, and not-so-secret activities at court, reports that the: few Spaniards who are still in her household prefer to be friends of the English, and neglect their duties as subjects of the King of Spain. The worst influence on the Queen is exercised by Doña María de Salinas, whom she loves more than any other mortal. Doña María has a relation of the name of Juan Adursa, who is a merchant in Flanders, and a friend of Juan Manuel. He hopes, through the protection of Juan Manuel, to be made treasurer of the Prince of Castile. By means of Juan Adursa and Doña María de Salinas, Juan Manuel is able to dictate to the Queen of England how she must behave. The consequence is that he can never make use, in his negotiations, of the influence which the Queen has in England, nor can he obtain through her the smallest advantage in any other respect.

The word “love” in the later Middle Ages can mean many things depending on context –courtly love, friendship, love of God, lord-vassal relationships, an apprentice for a master– and it could be shorthand for friendly affection. But Chapuys is clearly suggesting that the love has political implications, which further complicates an understanding of the significance of the relations of Catherine and her servants. But later events suggest a deep personal bond. María de Salinas had been forced to leave queen Catherine’s service in 1532 due to the politics of the divorce proceedings and Henry VIII’s marriage to Anne Boleyn, but she remained part of Catherine’s life. She defied Henry’s orders –never a wise thing to do even under the best of circumstances– and continued to correspond with the cast-off queen and sent her news of her daughter, Mary Tudor.

She and Charles Brandon, the king’s brother-in-law and close friend who was sent by Henry on numerous missions, had to impress upon Catherine the reality of her new marital state. In April 1533 Brandon had to tell her that she was no longer queen, and in December 1533 he was ordered to disband some of her servants and move her to the unhealthy home at Somersham. Catherine, defiant, locked herself in her room. María de Salinas told Chapuys that Catherine only relented when Charles admitted how he wished something dreadful would have happened on the road that would have made it impossible for him to carry out his duty to Henry. These are the actions of someone who is more than just a servant.

The depth of this relationship continued to the end. In 1535, when Catherina was seriously ill, María was denied permission to visit the former queen but once again, she defied Henry and traveled to Kimbolton Castle anyway. She was with Catherina when she died on January 7, 1536 and was the second mourner at Catherine’s funeral in February. Catherina had an equally close friendship with another Spanish noblewoman who served in her court. María de Rojas, daughter of Francesco de Rojas, count of Salinas, was one of Catherine’s closest and most intimate of the ladies at court, first in Spain and later in London. She appeared in queen Isabel’s household accounts in 1501 when she was paid 27,000 maravedís and received clothing in payment for service in 1500.

Her relationship with Catherina was as close as that of María de Salinas, a fact known best through her testimony in 1530 before the papal court concerning the divorce. She was asked to give a deposition concerning the consummation of the marriage between Catherina and Prince Arthur, who had died in April 1502, just a few months after their wedding. María de Rojas stated that to comfort the young widow, she had slept in bed with Catherina for the first few days after Arthur’s death: The same questions to be put to the wife of Juan Cuero once waiting maid to the said queen of England, and who is supposed to reside nowadays at Madrid; also to María de Rojas, wife of Don Álvaro de Mendoça, who used to sleep in the same bed with Her Most Serene Highness the Queen, after the death of prince Arthur, her first husband.

This is a remarkable glimpse into Catherina and into the sort of intimacy of life at court that was crucial to Catherina’s transition first from Spain to England and then from bride to widow. María de Rojas’s social rank and closeness to Catherina made her a desirable potential bride, first for the son of the earl of Derby, and later, the son of Elvira Manuel. Neither marriage took place and she returned to Spain around 1504 as señora de Santa Cruz de Campero where she married Álvaro de Mendoza y Guzman, son of Juan Hurtado de Mendoza and his second wife Leonor de Guzmán. It is possible that Maria de Rojas and María de Salinas were related and that when María de Rojas left England to marry, María de Salinas replaced her.

The intensely political life at court was not always conducive to such loyalty and devotion, and was often fraught with dangers. This is best exemplified by the relationship of Catherina and Elvira Manuel, guarda de las damas for Catherina, from 1499 to 1500, and her camarera mayor (chief household officer) from 1500 until 1507. Elvira Manuel de Villena Suárez de Figueroa was the daughter of Juan Manuel de Villena Fonseca, señor de Belmonte de Campos, and Aldonza Suárez de Figueroa. She married Manrique Manuel, Catherina’s chief mayordomo, and together the couple formed a key part of Catherina’s household in England.

Elvira made her first appearance in Catherina’s household in 1501, as Catherina prepared to move to England and on 10 March 1501 she received a payment of 100,000 maravedís: en cuenta de 216,666 marvedís de ovo de aver de su rraçcion e quitaçcion e ayuda de costa de vn año e ocho meses, en que seruio los años pasados de noventa e nueve e quinientos años, por el cargo de la guarda de sus damas. Their son, Iñigo, also came to England, as the master of Catherina’s pages. Elvira kept close contact with her brother, Juan Manuel, who was a servant of Philip of Burgundy.

In December 1505, Elvira was accused of promoting Philip’s interests at the expense of those of king Fernando, Catalina’s father, and Elvira was told to leave England. She departed on the pretext of visiting a doctor in Flanders about a disease that had already caused her to lose one of her eyes, but she knew that she would not be permitted to return. She had alienated not only king Henry but also Catherina. Elvira spent the rest of the life among Spanish exiles in Flanders.”

- Theresa M. Earenfight, “RAISING INFANTA CATALINA DE ARAGÓN TO BE CATHERINE, QUEEN OF ENGLAND.”

#katherine of aragon#maria de salinas#maria de rojas#elvira manuel#spanish#history#tudor#renaissance#ladies in waiting#theresa m earenfight

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the historical questions: 1, 9, and 27.

1. Favorite historical personality:I can't choose just one. I've had various hyperfixations, but in general women who were important enough to have their life recorded (as in sources imply they were politically active) yet we only know who they married/slept with and what children they bore, sometimes we are lucky and get another glimpse are always candidates: Aspasia of Miletus , Agrippina Maior , Queen Egilona, Lubna, Subh, Leonor de Guzmán are all there. Also rebellious queens: Cleopatra, Urraca I of Castille, Isabel of Castille, I love them.

9. Favorite historical movie: Kingdom of Heaven (director's cut). For reasons not related to historical accuracy (totally absent as is usual with Ridley Scott) and more with how it develops interesting characters (minus the protagonist, who is a Gary Stu, as is also usual with Ridley Scott) and the messages and themes it conveys:

-Does God exist? Who is right about Him if he does, Muslims or Christians? Why is he unfair?

-There are religious people and there are extremist assholes. Among the first there is good and bad, not necessarily in relation to how strong their faith is. The second ones have no redemption.

-Fuck the (symbolic) land, stop killing people. Also nobody is responsible for what their ancestors/other people in their identitarian group does/did.

27. Favorite What if.... Alexander the great hadn't died at 32? Would he have conquered Italy? Would the Empire have been consolidated? Would Rome have been an Empire? Always amazed by how much a detail like that could made the world entirely different.

Thank you so much @niniane17!!!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

A guide through the monarchs of Aragon in La Catedral del mar & Los Herederos de la tierra

@asongofstarkandtargaryen

During the series the role of the members of the monarchy is secondary, but they are used to help to establish a concrete historical context and they're very determinant in the situation of the Puig and Entanyol families involving political estrategies of supporting this or that king, that gave them benefits or dacay (Arnau's rise with Pedro IV, Genís & Roger rise with Juan I and Martín I and Bernat with Fernando I). So, I wanted to make a recopilation of the monarchs shown during these series and their families.

House of Aragon/ House of Barcelona (descendants of the Jimena dinasty)

The Jimena dinasty is called like that because its origin was Jimeno "the Strong", grandfather of Eneko Arizta, and one of its branches was the Arista-Iñiga dinasty started by Eneko.

Eneko, his son García Iñiguez and his grandson Fortún Garcés were Lords of Pamplona, Fortún Garcés married Awriya bint Lubb ibn Musa (great-grandaughter of Musa the Great), and one of their daughters was Oneka Fortúnez, who married Abd Allah I of Cordoba (their son was Muhammad, who fathered the calipha Abd al-Rahman III with a basque woman called Muzna) and then Oneka married Aznar Sánchez de Larraún, and had a daughter with him, Toda Aznárez. Toda married Sancho Garcés I, the truly first king of Pamplona, was Sancho Garcés I (the first king of the Jimena dinasty).

Sancho Garcés III (992-1036) was king of Pamplona, Count of Aragon and king consort of Castile, whose bastard son with Sancha de Aibar, Ramiro I, inherited the counties of Aragon, Sobarbe and Ribagorza, and united them to form the kingdom of Aragon.

Then Petronila I (1136-1173), Ramiro I's great-grandaughter, married Ramón Berenguer IV count of Barcelona. Their son Alfonso II of Aragon was the first king of the Crown of Aragon and Pedro IV's great-great- great-grandfather.

In summary all the Aragonese monarchs are descedants of Eneko Arizta (and that's the way we can link Irati with LCDM/LHDLT)

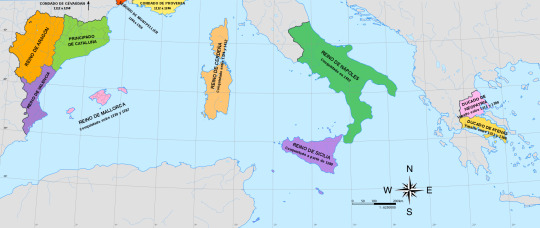

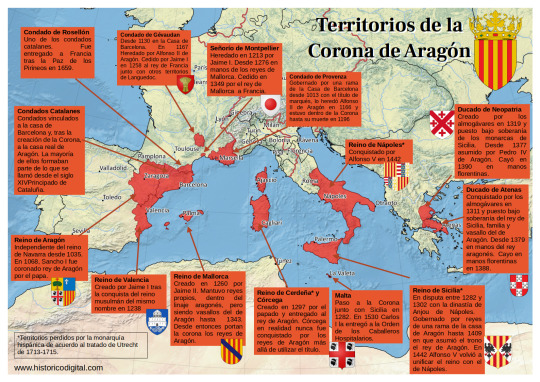

Pedro IV

Pedro IV of Aragon, II of Valencia and I of Mallorca (Balaguer, Lleida, Catalonia, September 5, 1319 - Barcelona, Catalonia, January 5, 1387), called "the Ceremonious" or the Punyalet ('the one with the dagger', due to a dagger he used to carry), son of Alfonso IV of Aragon and Teresa de Entenza.

King of Aragon, Valencia and Mallorca (1344-1387); Duke of Athens (1380-1387) and Neopatria (1377-1387); count of Barcelona (1336-1387) and of Ampurias (1386-1387).

In 1338 he married María de Navarra (1326-1347), daughter of Felipe III and Juana II of Navarra. Offspring:

Constanza (1343-1363), married in 1361 to Federico III of Sicily, and Juana (1344-1385), married in 1373 with Juan I de Ampurias.

In 1347 he married Leonor of Portugal (1328-1348), daughter of Alfonso IV of Portugal. She died the following year of the Black Death.

In 1349 he married Eleanor of Sicily (1325-1375), daughter of Pedro II of Sicily. Offspring:

Juan I (1350-1396), Martin I (1356-1410) and Leonor (1358-1382), married to Juan I of Castile. Leonor was the mother of Fernando I of Aragon.

In 1377 he married Sibila de Fortiá, daughter of the Empordà nobleman Berenguer de Fortiá. Offspring:

Isabel (1380–1424), who married Jaime II of Urgel, future suitor for the aragonese crown.

During his reign the Aragonese expansionism in the Mediterranean continued, focused on southern Italy and Greece.

Although he was ally of Alfonso XI, Pedro IV had a great rivalry with his son Pedro I of Castile and fought against him in some conflicts, like the War of the two Pedros (1356-1369) and the first Castilian Civil War (1351-1369), in which Pedro I was supported by Pedro I of Portugal (one of his bastard sons, Juan I of Portugal, was the founder and first king of the Avis dinasty) and Muhammad V of Granada, and Pedro IV supported the bastard children of Alfonso XI with his lover Leonor de Guzmán (Pedro de Aguilar, Sancho Alfonso, Fadrique Alfonso, Enrique II of Castile, Fernando Alfonso, Tello, Juan Alfonso, Juana Alfonso, Sancho and Pedro Alfonso), who started several revolts against Pedro I of Castile. The wars ended when Enrique killed Pedro I, and he became the first king of Castile of the Trastamara dinasty.

Sibila de Fortiá

Sibila de Fortiá (Fortiá, Girona, Catalonia, 1350 - Barcelona, Catalonia, 1406), queen consort of the Crown of Aragon (1377-1387). She was the daughter of Berenguer de Fortiá and his wife Francesca de Vilamarí. In 1371 she married for the first time Artal de Foces, an Aragonese nobleman, whom she widowed in 1374, and then she the lover of Pedro IV and had a daughter with him, Isabel.Pedro and Sibila married in 1377. After the wedding, Pedro surrounded himself with Empordà nobles as well as Sibila's relatives.

Pedro IV was very ill at the end of the year 1386, and Sibila, fearful of the wrath of the future King Juan, fled to the castle of San Martín de Sarroca (Barcelona), which belonged to her brother Bernat de Fortiá. There she was imprisoned by Juan I, who treated her harshly, accusing her of abandoning the king on his deathbed and of several robberies in the palace. She was confined in the castle of Moncada (Barcelona) until she renounced his property granted by the king. Finally, Sibila retired to the convent of San Francisco in Barcelona, where she died in 1406.

Juan I

Juan I of Aragon, called the Hunter or the Lover of All Kindness (Perpignan, Occitania, France, 1350 - Torroella de Montgrí, Girona, Catalonia, 1396), King of Aragon, Valencia, Mallorca, Sardinia and Corsica, and Count of Barcelona, Roussillon and Cerdanya ( 1387-1396). Son of Pedro IV and Leonor of Sicily.

His first marriage was with Marta de Armagnac (1347-1378), daughter of Count Juan I de Armagnac. With whom he had: Jaime (1374), Juana, (1375-1407) who married Mateo, Count of Foix. After the death of her father, she claimed the throne with her husband, but they were defeated; Juan (1376), Alfonso (1377) and Leonor (1378).

Widowed, Juan married Violante de Bar (1365-1431), daughter of Robert I, Duke of Bar. Offspring:

Jaime Duke of Girona (1382-1388), Yolanda, who married Louis II of Anjou, titular king of Naples. Their son, Luis III, claimed the throne after the death of Martín I, in the engagement of Caspe; Fernando Duke of Girona (1389), Antonia (1391-1392), Juan Duke of Girona (1392-1396), Eleanor (1393), Pedro Duke of Girona (1394) and Juan (1396)

Martin I

Martin I of Aragon, also called the Human or the Old (Girona, July 29, 1356-Barcelona, May 31, 1410), was king of Aragon, of Valencia, of Majorca, of Sardinia and count of Barcelona (1396-1420) and king of Sicily (1409-1410). Second son of Pedro IV of Aragon and his third wife Leonor of Sicily.

Martín was called "the Human" because of his great passion for the Humanities and books. The library of Martín I is the first that could be considered from Renaissance, if at that time in the history of the Iberian peninsula the term can already be used.

Martin married in 1372 with Maria de Luna, daughter of Lope, the first count of Luna, in 1374. From this union they were born:

Jaime (1378), Juan (1380) and Margarita (1388) and Martin I of Sicily "the Younger" (1376-1409), first husband of Blanca I of Navarra.

When Martin the Younger died, Martin married Margarita de Frades, although they left no issue.

His entire reign was marked by the Western Schism that divided Christianity since 1378. He was a supporter of the popes of Avignon (where he went the year of his coronation to swear allegiance to Benedict XIII "the Pope Luna", Pedro Martínez de Luna y Pérez de Gotor, with whom it seems that he came to establish a friendly relationship ), from whom he obtained support in his claims over the kingdom of Sicily against the Anjou, supporters of the popes of Rome. In 1400, he would marry his niece Yolanda to Louis II of Anjou in order to defuse tensions. He met in Avignon with the antipope Benedict XIII, Aragonese and a relative of the queen, with the intention of reaching a solution to the schism and, later, in 1403 he intervened militarily against the siege that Benedict suffered in his papal seat, rescuing him and welcoming him in Peñíscola .

House of Trastamara (the Aragonese branch)

Fernando I

Ferdinand I of Aragon (Medina del Campo, Valladolid, Castile and Leon, November 27, 1380-Igualada, April 2, 1416), also called Fernando de Trastámara and Fernando de Antequera, the Just and the Honest, was an infant of Castile, king of Aragon, Valencia, Mallorca, Sardinia, Count of Barcelona (1412-1416), and regent of Castile (1406-1415), during the minority of Juan II of Castile. Son of Juan I of Castile and Leonor of Aragon.

He was the first Aragonese monarch of the Castilian dynasty of the Trastámara, although he was of Aragonese origin on his mother's side.

He married Leonor de Alburquerque

Alfonso the Magnanimous (Medina del Campo, 1394-1458), king of Aragon, with the name of Alfonso V, and of Naples and Sicily, with the name of Alfonso I.

María de Aragón (Medina del Campo, 1396-1445), first wife of Juan II of Castile and mother of Enrique V of Castile

Juan II (Medina del Campo, 1397-1479), King of Aragon and King consort of Navarre.

Enrique (1400-Calatayud, 1445), II Duke of Villena, III Count of Alburquerque, Count of Ampurias, Grand Master of the Order of Santiago.

Leonor (1402-1445), who married Eduardo I of Portugal. Mother of Alfonso V of Portugal, Juana of Portugal (Enrique IV's second wife) and Leonor of Portugal, who married Frederick III of Habsburg (they were parents of emperor Maximilian I of Austria)

Pedro (1406-1438), IV Count of Alburquerque, Duke of Noto.

Sancho (1400-1416)

Alfonso V

Alfonso V of Aragon (Medina del Campo, 1396 – Naples, June 27, 1458), also called the Wise or the Magnanimous, king of Aragon, of Valencia, of Majorca, of Sicily, of Sardinia and Count of Barcelona (1426-1458); and King of Naples (1446-1458).

Alfonso V can be considered as a genuine prince of the Renaissance, since he developed an important cultural and literary patronage that earned him the nickname of the Wise and that would make Naples the main focus of the entry of Renaissance humanism in the sphere of the Crown of Aragon.

From his relationship with his lover Giraldona de Carlino, a napolitan noblewoman, he had three children:

Fernando (1423-1494), his successor in the kingdom of Naples under the name Fernando I.

Maria (1425-1449), married to Lionel, Marquis of Este and Duke of Ferrara.

Leonor, or Diana Eleonora (?-1450), married the nobleman Marino Marzano, Prince of Rossano.

Maria of Castile

María of Castile (Segovia, Castile and Leon, November 14, 1401-Valencia, October 4, 1458). Infanta of Castile, Princess of Asturias (1402-1405) and Queen of Aragon (1416-1458) for her marriage to Alfonso the Magnanimous. First daughter of Enrique III "the Mourner" and Catherine of Lancaster. Sister of Juan II of Castile, untie of Enrique IV and Isabel I.

The marriage between María and Alfonso is celebrated in the Cathedral of Valencia on October 12, 1415. The ceremony was officiated by the antipope Benedict XIII, who also granted the matrimonial dispensation for the wedding.

In 1420, when the king left for Naples for the first time, he left the government of his kingdoms in the hands of Maria as lieutenant general. The absence of the Magnanimous would last three years, during which María had to face the rapid deterioration of the economic situation in Catalonia, the territorial struggle with the Castilian Crown, as well as the conflicts of a social nature that shook her in different kingdoms. On his return to Aragon in 1423, Alfonso V began the war with Castile, along with his brother King Juan of Navarra. But her financial resources were exhausted and in 1429 Queen María had to act as a mediator between her husband and her brother, King Juan II of Castile, to put an end to the dispute. However, Alfonso's situation did not improve, due to the recession suffered by the Catalan economy and the social conflicts caused by it. The Courts of Barcelona in 1431 demanded from the king a series of measures to correct the enormous deficit of the Catalan treasury and trade. But Alfonso, fed up with these matters, returned to Italy and gave full powers to the queen as ruler of Aragon; he left the Iberian Peninsula forever on May 29, 1432. This marked Alfonso V's final break with the Crown of Aragon, which, however, he never renounced.

+ Bonus track (although he doesn't appear in this series)

Juan II

Juan II of Aragon and Navarra, the Great, or the Faithless according to the Catalan rebels who rose up against him (Medina del Campo, June 29, 1398-Barcelona, January 20, 1479) was Duke of Peñafiel, King of Navarre (1425-1479), King of Sicily (1458-1468) and King of Aragon, Mallorca, Valencia, Sardinia (1458-1479) and Count of Barcelona, son of Ferdinand I of Aragon and Leonor de Albuquerque.

From his first marriage to Blanca I of Navarra (daughter of Leonor of Castile and Carlos III of Navarra):

Carlos (1421-1461), Prince of Viana and Girona, Duke of Gandia and Montblanch, titular King of Navarra as Carlos IV (1441–1461), married Agnes of Cleves. He wrote the 'Chronicles of the Monarchs of Navarra', about the history of his antecessors, from Eneko Arizta in the 8th century up to the 15th century.

Juan (1423-1425)

Blanca of Navarra (1424-1464), first wife of Enrique IV of Castile

Leonor (1425-1479), married to Gastón IV de Foix, Queen of Navarre under the name of Leonor I.

From his second marriage to Juana Enríquez:

Leonor of Aragon (1448)

Fernando II (1452-1516), king iure uxoris of Castile (1474-1504) and then regent between 1507 and 1516, under the name of Fernando V due to his marriage to Isabel I, king of Sicily (as Fernando II, 1468-1516), Aragon and Sardinia (as Fernando II, 1479-1516), Naples (as Fernando III, 1504-1516), and from Navarra (as Fernando I, 1512-1516)

Juana (1455-1517), second wife of Fernando I of Naples. Her daughter Juana married Fernando II of Naples (Fernando I of Naples' grandson)

During his youth, Juan fought in the Castilian-Aragonese war (1429-30) and the Castilian Civil War (1437-1445) in the Aragonese team against Juan II of Castile, his son Enrique and the Constable Álvaro de Luna (favourite of Juan II), due to the Aragonese political influences in Castile and the full control that Álvaro de Luna had over Juan II of Castile that allowed him to become very powerful, so some members of the Castilian nobility wanted to remove Álvaro out of Juan II side because of that, and the Aragonese reacted to the anti-aragonese convictons of Álvaro.

Álvaro de Luna arranged a new marriage between Juan II of Castile and Isabel of Portugal (mother of Isabel I) in 1447. The constable intended with this dynastic alliance to strengthen the political ties that united Castile and Portugal against the common enemy: the Catalan-Aragonese Crown, but from 1449, Isabella of Portugal indirectly supported the maneuvers of the Great League of Nobles (allies of the Aragonese) formed against the constable. But it would not be until 1453 when Juan II of Castile, possibly tired of the continuous pressure from the aristocracy, left Álvaro on his own. It has often been said that it was the queen herself who demanded that her husband signed the prison order against Álvaro, through Juan Pacheco, Marquis of Villena.

By 1441 Blanca I de Navarra died and Juan II married the daughter of Fadrique Enríquez (one of his Castilian allies, the admiral of Castile), Juana Enríquez y Fern��ndez de Córdoba.

After the death of Blanca I, a dispute between Juan II and Carlos de Viana about the sucession for the Navarrese throne. Juan was king Iure uxoris of Navarre and wanted to be keep his position as king, but Carlos and his supporters claimed that the prince was the rightful king as firstborn son of the queen and in 1451 the Navarrese civil war started.

In the following years the tension between Juan and Carlos increased with the birth of Fernando, who was pushed by his mother Juana to be the heir of Aragon and Navarra, which Juan later accepted. This change in the sucession was not accepted in Catalonia, that supported Carlos de Viana birthrights, and they started a rebellion against Juan II.

Other supporter of Carlos was Enrique IV, who offered his sister Isabel to Carlos in marriage as a sign of their alliance, but the wedding never happened.

Carlos died in 1461, although the war didn't ended because the Catalan nobility proposed other suitors for the Crown of Aragon and the Principality of Catalonia, like Enrique IV, Pedro of Portugal (grandson of Jaime II of Urgell) and Renato de Anjou during the Catalan civil war, that ended in 1472.

It's interesting that the interesting that the current situation of the Estanyol family at the end of Los Herederos de la tierra is that there are two brothers from different mothers, and whose father have benefited one of them over the other, so it may lead to tensions from the part that was not benefited, Arnau Jr is the main heir in Bernat's will, so maybe in the future Marta Destorrent will try to pit her son Baltasar against his elder brother to take Arnau Jr's place. By period of time I find very likely that this happens during the reigns Maria of Castile and Juan II, and the situation of the Estanyol succession could parallel the Carlos de Viana-Fernando II problem, although in this case the younger son was the benefited one and the one who inherited his father's kingdoms and maybe the Estanyols are part of the Catalan nobility that defended Carlos' birthrights, although some other Catalan nobles supported Juan II & Fernando alongside of peasants and smallfolk, during the First Remensa War during the Catalan civil war.

The Remensa War consisted in revolts organised by peasants who wanted to end the servitude to which their feudal lords had subjected them, so I think that probably the Estanyol-Llor family would support the peasants because of their backgrounds.

#la catedral del mar#los herederos de la tierra#the cathedral of the sea#heirs to the land#history#crown of aragon#aragonese monarchs#pedro iv de aragón#juan i de aragón#martín i de aragón#sibila de fortiá#fernando i de aragón#alfonso v de aragón#maria de castilla#juan ii de aragón#gifs#period dramas#house of aragon#house of trastamara#house of barcelona#long post

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Enrique II de Trastámara: De bastardo a rey, una historia de lucha y traición.

Enrique II de Castilla, conocido como "el Fratricida" o "el de las Mercedes", fue un personaje fascinante y controvertido que marcó la historia de España. Nacido en Sevilla en 1334 como hijo ilegítimo del rey Alfonso XI y su amante Leonor de Guzmán, Enrique se vio envuelto desde niño en las intrigas políticas y las luchas por el poder.

Tras la muerte de su padre, su hermanastro Pedro I, "el Cruel", ascendió al trono, iniciando un reinado marcado por la violencia y la tiranía. Enrique, junto a sus hermanos, se convirtió en uno de los principales líderes de la oposición al rey. En 1369, ambos hermanos se enfrentaron en la batalla de Nájera, donde Pedro I salió victorioso. Enrique se vio obligado a huir al exilio, refugiándose en Francia.

Sin embargo, Enrique no se rindió. En 1371, con el apoyo de la nobleza castellana descontenta con el gobierno de Pedro I, regresó a España y se proclamó rey en Burgos. Tras una cruenta guerra civil, Enrique finalmente derrotó a su hermanastro en la batalla de Montiel en 1379, donde Pedro I encontró la muerte.

Con la victoria, Enrique II consolidó su posición como rey de Castilla, dando inicio a la dinastía Trastámara que reinaría en España durante más de dos siglos. Su reinado se caracterizó por la paz interna, la recuperación económica y la expansión territorial. Enrique II también fue un gran mecenas de las artes y la cultura, impulsando la construcción de importantes monumentos como el Alcázar de Segovia.

0 notes

Note

In terms of physical appearance... Could we say that Katharine of Aragon was a Trastamara while her elder sister Juana I was an Enriquez?

It’s complicated. Henry II of Castile, previously known as count of Trastámara, had a twin brother, Fardique of Castile, both were the sons of Alfonso XI of Castile and his mistress, Leonor de Guzmán. Juan II of Castile and Juan II of Aragon (Isabella and Ferdinand’s fathers respectively) were Henry II’s great-grandsons, whereas Juana Enríquez was Fadrique’s (the other twin’s) great-granddaughter. I would say Katharine looked more like her mother and possibly more like her maternal great- grandmother, Catherine of Lancaster, whereas Juana was said to be a spitting image of her paternal grandmother, Juana Enríquez, and also the most attractive of Isabella and Ferdinand’s lot.

#question to me#anonymous#answered#katherine of aragon#katharine of aragon#juana i of castile#joanna i of castile#the trastámaras

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beatriz of Castile, Queen of Portugal (Wife of King Afonso IV of Portugal)

Tenure: 7 January 1325 – 28 May 1357

Beatrice of Castile or Beatriz (8 March 1293 in Toro – 25 October 1359 in Lisbon), was an infanta of Castile, daughter of Sancho IV and María de Molina. She was Queen of Portugal from the accession of her husband, Afonso IV, until his death on 28 May 1357.

Daughter of Sancho IV and of María de Molina, Infanta Beatriz was born in Toro. She had six siblings, including King Fernando IV of Castile and Queen Isabel, wife of King James II of Aragon, and later duchess as the wife of John III, Duke of Brittany.

On 13 September 1297, when Beatriz was only four years old, the bilateral agreement, known as the Treaty of Alcañices, was signed between Castile and Portugal, putting an end to the hostilities between both kingdoms and establishing the definitive borders. The treaty was signed by Queen María de Molina, as the regent of Castile on behalf of her son, Fernando IV, who was still a minor, and King Dinis of Portugal. To reinforce the peace, the agreement included clauses arranging the marriages of King Fernando and Constança of Portugal and that of her brother, Afonso, with Beatriz; that is, the marriage of two siblings, infantes of Portugal, with two other siblings, infantes of Castile.

Beatriz abandoned Castile in the same year and moved to the neighboring kingdom where she was raised in the court of King Dinis together with her future spouse, Infante Afonso, who at that time was about six years old. Her future father-in-law "had inherited from his grandfather, Afonso X of Castile, a love of letters, literature, Portuguese poetry, and the art of the troubadours" and Beatriz grew up in this refined environment. Two of the Portuguese king's illegitimate sons, both important figures in the kingdom's cultural panorama, were also at the court: Pedro Afonso, Count of Barcelos, a poet and troubadour and the author of Crónica Geral de Espanha and the Livro de Linhagens; and, Afonso Sanches, the favorite son of King Dinis and a celebrated troubadour.

After the signing of the Treaty of Alcañices and upon their return to Portugal, King Dinis gave his future daughter-in-law the Carta de Arras (wedding tokens) which included the señoríos of Évora, Vila Viçosa, Vila Real and Vila Nova de Gaia which generated an annual income of more than 6000 pounds of the old Portuguese currency. After the marriage, these estates were increased. In 1321, her husband, who had not ascended to the throne yet, gave her Viana do Alentejo; in 1325, he gave her other properties in Santarém; in 1337, properties in Atalaia; in 1341, a manor house in Alenquer; in 1350, the prior of the Monastery of San Vicente de Fora gave her Melide, a manor house in Sintra; and later, in 1357, her son, King Pedro, gave her more estates which included Óbidos,

Atouguia, Torres Novas, Ourém:

Porto de Mós:

and Chilheiros.

The marriage was celebrated in Lisbon on 12 September 1309. Before the marriage could take place, a papal dispensation was required since Afonso was a great-grandson of King Afonso X of Castile through his illegitimate daughter, Beatriz of Castile (King Dinis’s mother and Afonso grandmother), and Beatriz, betrothed to Afonso, was a granddaughter of the same Castilian king. In 1301, Pope Boniface VIII issued the papal bull authorizing the marriage, but since both were underage, it was postponed until 1309 when Afonso was eighteen years old and Beatriz had turned sixteen. It was a fertile and apparently happy marriage. Four out of the seven children born of this marriage died in their infancy.

Like her mother-in-law, Isabel of Aragon, who had raised her as a child, during her marriage Beatriz played a relevant role in the affairs of the kingdom and was "the first foreign-born queen who was perfectly versed in the language and customs of Portugal which facilitated her role as a mediator of conflicts". She discreetly supported her husband when he confronted his father on account of his half-brother, Afonso Sanches. In 1325 after the death of King Dinis, Afonso "who had not forgotten former hatreds", demanded to be acclaimed king by the court and was responsible for having his half brother João Afonso killed, and his great rival, his other bastard brother, Afonso Sanches, banished to Castile".

When her husband and her son-in-law King Alfonso XI of Castile fought in the war that took place in 1336 – 1339, Beatriz crossed the border and went to Badajoz to meet the Castilian king to try to reach an agreement that would bring peace to both kingdoms, although her efforts proved to be fruitless. She sent her ambassadors in 1338 to the court of King Afonso IV of Aragon to strengthen the alliance between both kingdoms which had been weakened when her son, the future King Pedro I of Portugal, refused to marry Branca, a niece of the Aragonese king because of her proven "mental weakness (...) and her incapacity for marriage".

Queen Beatriz and Guilherme de la Garde, Archbishop of Braga, acted as mediators in the quarrel, which lasted almost one year and posed the threat of another civil war in the Kingdom of Portugal following the assassination of Inês de Castro, and in 1355, father and son reached an agreement.

On the religious front, she founded a hospital in 1329 in Lisbon and later, with her husband, the Hospital da Sé to treat twenty-four poor people of both sexes, providing the institution with all that was required for its day-to-day maintenance. In her last wills and codicil, she left many properties and sums for religious establishments, particularly for the Dominican and Franciscan orders, and asked to be buried wearing the simple robe of the latter order.

Beatriz and Afonso IV were the parents of the following infantes:

Maria (1313 in Coimbra – 18 January 1357), was the wife of Afonso XI of Castile, and mother of the future king Pedro I of Castile. Due to the affair of her husband with his mistress Leonor de Guzmán "it was an unfortunate union from the start, contributing to dampening the relations of both kingdoms";

Afonso (1315 in Coimbra), heir to the throne, was a stillbirth. Buried at the disappeared Convento das Donas of the Dominican Order in Santarém;

Dinis (12 January 1317 - 18), heir to the throne, died a year after and was buried in Alcobaça Monastery;

Pedro (8 April 1320 – 18 January 1367), the first surviving male offspring, he succeeded his father. When his wife Constança died in 1345, Queen Beatriz took care of the education of the two orphans, the infantes Maria and Fernando, who later reigned as King Fernando I of Portugal;

Isabel (21 December 1324 – 11 July 1326), buried at the Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Velha in Coimbra;

João (23 September 1326 – 21 June 1327), buried at the Monastery of São Dinis de Odivelas;

Leonor (1328 in Coimbra – October 1348), born in the same year as her sister Maria's wedding, she married King Pedro IV of Aragon in November 1347 and died a year after her marriage succumbing to the Black Death.

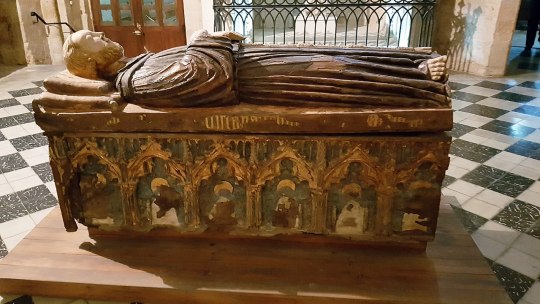

Queen Beatriz executed three wills and one codicil. She died in Lisbon when she was 66 years old and was buried at Lisbon Cathedral next to her husband as she had stipulated in her will.

While the definitive tombs were being built, the royal couple was originally buried at the choir of the church and it was not until the reign of King João I that their remains were transferred to the new sepulchers in the main chapel of the cathedral. These sepulchers were destroyed during the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and were replaced in the 18th century. The Livros do Cartóiro da Sé (Charters of the Cathedral) written between 1710 and 1716, describe the burial of Queen Beatriz, very similar to that of her husband, with an engraving that read: Beatriz Portugaliae Regina / Affonsi Quarti Uxor. (Beatriz Queen of Portugal, wife of Afonso IV).

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

BREAKING NEWS: SNAKE CAULDRON UPDATE

We interrupt your regularly scheduled BS (Burke Sundays) to bring you breaking news on the Mystery of the Snake Cauldrons. While on a visit to the Art Institute of Chicago, enjoying the… interesting medieval art, I was abruptly confronted by a worn but unmistakable motif on a late-fourteenth century altarpiece:

So obviously, I spent some time digging. The altarpiece did enable me to connect the snake cauldrons to a specific family. It was commissioned by Pedro López de Ayala and also features the wolves-and-saltires of Ayala. However! He was married to Leonor de Guzmán, and their tombs were located in the same church - and yep, turns out the snake cauldrons are the arms of the house of Guzmán!

There are, of course, numerous versions of the arms; the snake cauldrons alone are probably the oldest version, but some have the bordure of Aragon and Castile (as in Villamanrique), and there are also versions which have the snake cauldrons party with the ermine of Brittany, which seem to be the arms of the cadet branch of the house of Olivares. Some accounts of fifteenth-century chroniclers date the ermine-and-snake-cauldrons version back to the 800s, but I’m extremely skeptical of this.

However, none of this answers the real question: why? Why the hell would this extremely specific motif end up tied to this family? And that I still don’t have a good answer for. There is a pretty awesome legend about Guzmán the Good slaying “la serpiente de Fez,” but I don’t think that can explain it. Firstly, accounts of this story aren’t recorded before the mid-fifteenth century, and we’ve already seen that the snake cauldrons are older than that - maybe not much older, but definitely older. Also, context demonstrates that the “serpent” of Fez was actually a dragon, and it became incorporated into the Guzmán arms in an entirely different way: it’s sometimes seen as a supporter-like figure at the base of the shield. I find it hard to believe that the same legend gave rise to two completely different armorial components. Admittedly, it’s not impossible, but I’ll need a lot stronger evidence before I go with this explanation.

At this point, I have one tiny glimmer of a lead. There are a couple of late nineteenth-century English heralds who claim that the cauldron was used in Spanish heraldry as a symbol of the ability to provide for one’s army. They claim the snakes were intended to be eels. While this isn’t completely out of the question, it does smell like the kind of reverse-engineered symbolic nonsense that later heraldic writers are prone to. I don’t know if I’m satisfied with this explanation or not; I need to evaluate these two further before I decide if this explanation is worth pursuing further.

Stay tuned!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imágenes y textos de T.R.I.P.A. - Tomo 1, de Maximiliano Masuelli

en: T.R.I.P.A. - Tomo 1, 2019

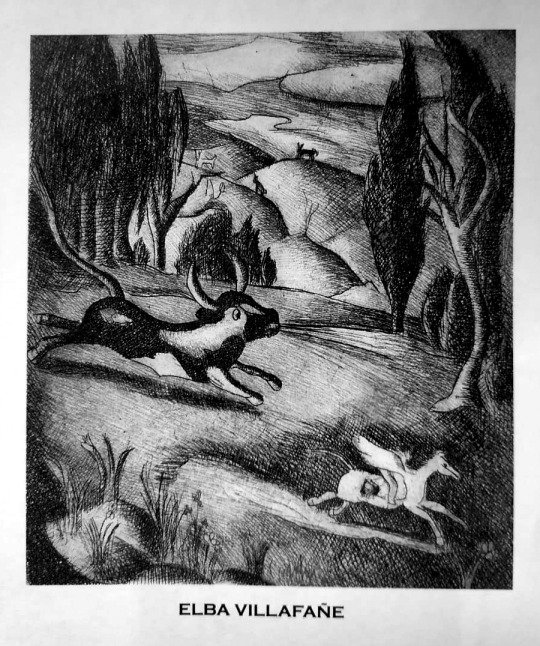

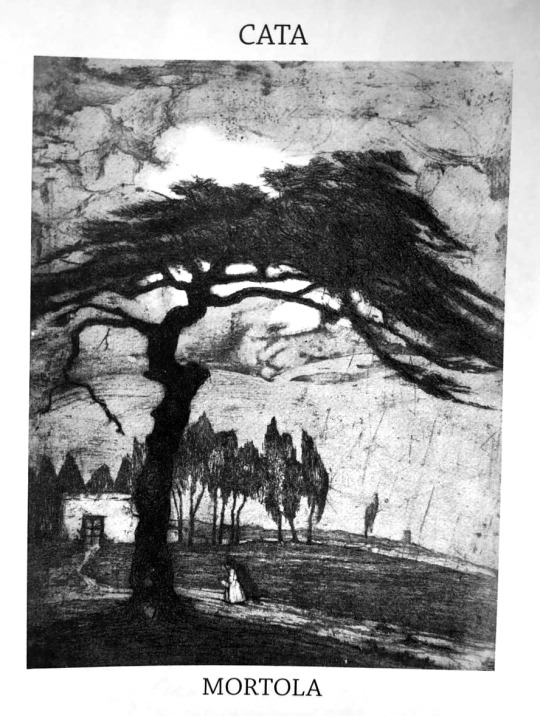

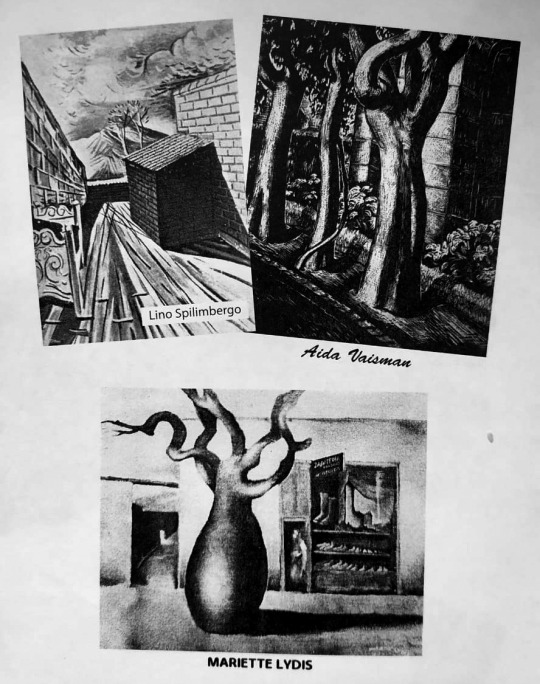

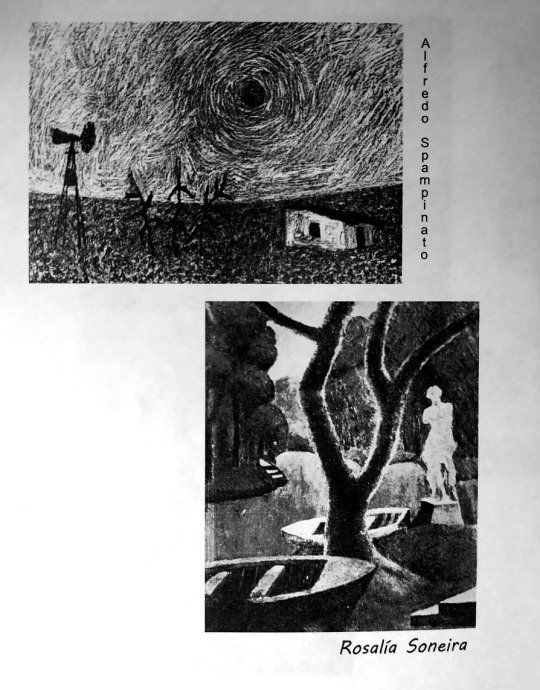

Raquel Palumbo expuso paisajes de La Boca en El Greco. Florencio Molina Campos pintó las tierras bajas de General Madariaga. Elena Hermitte retrató Tunuyán y las ruinas de San Francisco. Elba Villafañe reflejó en sus estampas las leyendas y tradiciones del norte argentino. En la búsqueda de atmósferas cristalinas, Luis Cordiviola se afincó en Cabalango. Cata Mortola expuso una serie de treinta y ocho grabados de paisajes de la provincia de Buenos Aires en Amigos del Arte. José Fontana realizó xilografías con evocaciones de la Pampa. Lía Gismondi mostró paisajes de Lanús, Quilmes y Alta Gracia en Witcomb. Dignora Pastorello pintó Visión de San Telmo. Mario Lozza prestó atención a los temas rurales de Entre Ríos. Luis Falcini organizó en librería Amauta la primera muestra de paisajes misioneros de Carlos Giambiagi. Lucrecia Moyano tomó apuntes en acuarela de las playas de Mar del Plata. Alberto Rossi fue pionero en los temas del Riachuelo. Eglantina Villagra envió Paisaje del Challao al Salón de Cuyo. Osorio Luque expuso veinticuatro motivos de Tucumán en Galería Diez. Lola de Lusarreta pintó Puente Pueyrredón. Fortunato Lacámera mostró por primera vez sus impresiones de la Isla Maciel en Salón Chandler. Gertrudis Chale contó: “Quisiera pintar inconfundiblemente imágenes de la tierra argentina en las que se vea algo de su tremenda realidad y de su misterio”.

Juana Lumerman viajó reiteradamente a las coloridas tierras del norte, donde realizó numerosos dibujos. Raúl Domínguez expuso visiones de las islas del Charigüé en Renom. Susana Aguirre recorría los barrios porteños en su pequeño auto buscando motivos para sus pinturas de frentes de casas. Eduardo Maglione definió a Américo Panozzi como el pintor solitario de los lagos del sur. Cesáreo Bernaldo de Quirós reflejó con precisión los rincones de su amada Selva de Montiel. Leonor Terry pintó calles y patios de Tilcara. Raquel Forner dibujó las playas de Miramar. Julio Suárez Marzal se distinguió por sus imágenes de la alta montaña. Laura Mulhall Girondo captó la fisonomía esencial de la Pampa. Anselmo Piccoli obtuvo una beca para estudiar el paisaje del Litoral. Andrée Moch pintó Tandil. Alicia Malinverno hizo viajes de estudio por el norte argentino. En sus idas a la costa atlántica, Yente realizó modernos paisajes de Reta. Alberto Pedrotti se instaló un tiempo en Tanti, donde tomó apuntes de las sierras chicas. Rosa Campanello tuvo como fuente de inspiración la precordillera mendocina. Estanislao Guzmán Loza plasmó su tierra natal de La Rioja. Elvira Rezzo expuso motivos de Talar de Pacheco en Müller y los separó en cinco series: El bosque encantado, Caminos líricos, Barrancas y llanuras, Viejos muros y Poesía de los troncos y del follaje. Beatriz Vignoli se pregunta: “¿Cómo no es más conocida la obra de Ada Tvarkos, quien al igual que sus contemporáneos masculinos pintó el paisaje urbano de Rosario en el lenguaje depurado de las paletas tonales y las formas puras?”.

#T.R.I.P.A.#paisaje#argentino#pintura#dibujo#grabado#investigación#artistas#sigloxx#ivanrosado#masuelli#arteargentino

1 note

·

View note