#henry ii of castile

Text

The Bastard Kings and their families

This is series of posts are complementary to this historical parallels post from the JON SNOW FORTNIGHT EVENT, and it's purpouse to discover the lives of medieval bastard kings, and the following posts are meant to collect portraits of those kings and their close relatives.

In many cases it's difficult to find contemporary art of their period, so some of the portrayals are subsequent.

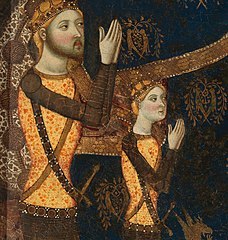

1) Henry II of Castile ( 1334 – 1379), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán; and his son with Juana Manuel de Villena, John I of Castile (1358 – 1390)

2) His wife, Juana Manuel de Villena (1339 – 1381), daughter of Juan Manuel de Villena and his wife Blanca de la Cerda y Lara; with their daughter, Eleanor of Castile (1363 – 1415/1416)

3) His father, Alfonso XI of Castile (1311 – 1350), son of Ferdinand IV of Castile and his wife Constance of Portugal

4) His mother, Leonor de Guzmán y Ponce de León (1310–1351), daughter of Pedro Núñez de Guzmán and his wife Beatriz Ponce de León

5) His brother, Tello Alfonso of Castile (1337–1370), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán

6) His brother, Sancho Alfonso of Castile (1343–1375), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Leonor de Guzmán

7) Daughters in law:

I. Eleonor of Aragon (20 February 1358 – 13 August 1382), daughter of Peter IV of Aragon and his wife Eleanor of Sicily; John I of Castile's first wife

II. Beatrice of Portugal (1373 – c. 1420) daughter of Ferdinand I of Portugal and his wife Leonor Teles de Meneses; John I of Castile's second wife

Son in law:

III. Charles III of Navarre (1361 –1425), son of Charles II of Navarre and Joan of Valois; Eleanor of Castile's huband

8) His brother, Peter I of Castile (1334 – 1369), son of Alfonso XI of Castile and Mary of Portugal

9) His niece, Isabella of Castile (1355 – 1392), daughter of Peter I of Castile and María de Padilla

10) His niece, Constance of Castile (1354 – 1394), daughter of Peter I of Castile and María de Padilla

#jonsnowfortnightevent2023#henry ii of castile#john i of castile#juana manuel de villena#eleanor of castile#alfonso xi of castile#leonor de guzmán#tello alfonso of castile#sancho alfonso of castile#peter i of castile#constance of castile#isabella of castile#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#day 10#echoes of the past#historical parallels#medieval bastard kings#bastard kings and their families#eleanor of aragon#beatrice of portugal#charles iii of navarre#canonjonsnow

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

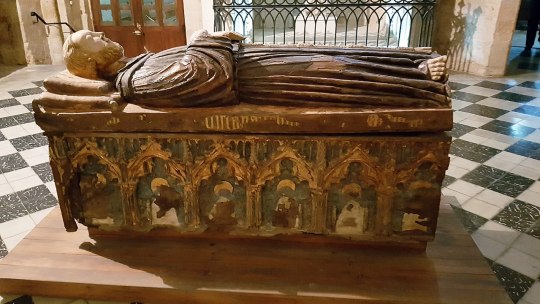

A VISIT TO KING'S LANGLEY

King’s Langley was once home to a massive Plantagenet palace, built out of the remnants of a hunting lodge of Henry III for Edward I’s Queen, Eleanor of Castile. She furnished it lavishly, with carpets and baths. There were shields decorating the hall and a painted picture of four knights going to a tournament, while the expansive gardens were planted with vines. After her death, the palace was…

View On WordPress

#Anne Mortimer#camels#Cecily Neville#Christmas#Clarendon Palace#clocks#Dominican friaries#Edmund of Langley#Edward II#Edward III#Eleanor of Castile#fire#Henry III#Henry IV#Isabel of Castile#Joan of Navarre#John of Wheathampstead#King&039;s Langley#palaces#Piers Gaveston#Reformation#Richard Earl of Cambridge#Richard II#royal tombs

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

How come Catherine de Medici loved Henri so much even though he (cheated and) significantly favoured Diane de portiers, and also slighted her at time like with the castle she wanted and he didn’t give it to her?

It is the accepted narrative that Catherine de’ Medici was obsessively in love with her husband King Henri II, despite the fact that--or perhaps because, depending on who you’re reading--he was clearly in love with Diane de Poitiers. It’s not terribly different from the stories told about Juana of Castile, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella and heiress to Castile. She was married to Philip IV Hapsburg, duke of Burgundy, who was reportedly both very handsome and a womanizer. The stories claim that Juana was so wildly in love with her husband that, after he died from illness, she carried his corpse with him wherever she travelled, and renounced the throne of Castile out of grief and madness. In fact, she is popularly known as Juana la Loca or Juana the Mad.

This is almost certainly propaganda spread both during Juana’s lifetime and after her death. Whatever her feelings were for her husband, he repaid them by conspiring with her father King Ferdinand to dethrone Juana in favour of her young son Charles so they could collectively rule on his behalf. Similarly, much of what we know of Catherine de’ Medici’s feelings for her unfaithful husband comes from the same sources that tell us she was a poisoner and the centre of webs of intrigue and murder.

We know Catherine never remarried or showed any interest in remarrying after Henri’s shocking death in 1559, but there are plenty of reasons for that. She and Henri were married when both of them were 14 years old, and for the first ten years, Catherine was blamed for the couple’s inabiilty to conceive any children. Henri took multiple mistresses at first, but finally settled on Diane de Poitiers, who he treated with far greater respect and affection than his wife. In January 1544, after nearly eleven years of marriage, Catherine finally gave birth to the long-awaited heir to the throne. After him, she had nine more children who survived infancy, and nearly died giving birth to two more.

We also know that she adopted the image of a broken lance and the motto “lacrymae hinc, hinc dolor“ (”from this come my sorrow and tears”) after his death in a jousting accident. But it’s worth remembering that her position as Regent of France on behalf of three of her sons over the next half-century at least partly depended on her keeping up an obvious connection to the previous Valois king. How much of Catherine’s grief was real and how much was politically motivated, we honestly can’t say. But she was an extremely clever woman who spent years flying under the radar before ending up all but ruling France, so she was certainly adept at playing dangerous games.

#history#catherine de' medici#16th century#france#henri ii#diane de poitiers#juana of castile#philip iv hapsburg

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blanche, Marguerite, and Queenship

Blanche's actions as queen dowager amount to no more than those of her grandmother and great-grandmother. A wise and experienced mother of a king was expected to advise him. She would intercede with him, and would thus be a natural focus of diplomatic activity. Popes, great Churchmen and great laymen would expect to influence the king or gain favour with him through her; thus popes like Gregory IX and Innocent IV, and great princes like Raymond VII of Toulouse, addressed themselves to Blanche. She would be expected to mediate at court. She had the royal authority to intervene in crises to maintain the governance of the realm, as Blanche did during Louis's near-fatal illness in 1244-5, and as Eleanor did in England in 1192.

In short, Blanche's activities after Louis's minority were no more and no less "co-rule" than those of other queen dowagers. No king could rule on his own. All kings- even Philip Augustus- relied heavily on those they trusted for advice, and often for executive action. William the Breton described Brother Guérin as "quasi secundus a rege"- "as if second to the king": indeed, Jacques Krynen characterised Philip and his administrators as almost co-governors. The vastness of their realms forced the Angevin kings to rely even more on the governance of others, including their mothers and their wives. Blanche's prominent role depended on the consent of her son. Louis trusted her judgement. He may also have found many of the demands of ruling uncongenial. Blanche certainly had her detractors at court, but she was probably criticsed, not for playing a role in the execution of government, but for influencing her son in one direction by those who hoped to influence him in another.

The death of a king meant that there was often more than one queen. Blanche herself did not have to deal with an active dowager queen: Ingeborg lived on the edges of court and political life; besides, she was not Louis VIII's mother. Eleanor of Aquitaine did not have to deal with a forceful young queen: Berengaria of Navarre, like Ingeborg, was retiring; Isabella of Angoulême was still a child. But the potential problem of two crowned, anointed and politically engaged queens is made manifest in the relationship between Blanche and St Louis's queen, Margaret of Provence.

At her marriage in 1234 Margaret of Provence was too young to play an active role as queen. The household accounts of 1239 still distinguish between the queen, by which they mean Blanche, and the young queen — Margaret. By 1241 Margaret had decided that she should play the role expected of a reigning queen. She was almost certainly engaging in diplomacy over the continental Angevin territories with her sister, Queen Eleanor of England. Churchmen loyal to Blanche, presumably at the older queen’s behest, put a stop to that. It was Blanche rather than Margaret who took the initiative in the crisis of 1245. Although Margaret accompanied the court on the great expedition to Saumur for the knighting of Alphonse in 1241, it was Blanche who headed the queen’s table, as if she, not Margaret, were queen consort. In the Sainte-Chapelle, Blanche of Castile’s queenship is signified by a blatant scattering of the castles of Castile: the pales of Provence are absent.

Margaret was courageous and spirited. When Louis was captured on Crusade, she kept her nerve and steadied that of the demoralised Crusaders, organised the payment of his ransom and the defence of Damietta, in spite of the fact that she had given birth to a son a few days previously. She reacted with quick-witted bravery when fire engulfed her cabin, and she accepted the dangers and discomforts of the Crusade with grace and good humour. But her attempt to work towards peace between her husband and her brother-in-law, Henry III, in 1241 lost her the trust of Louis and his close advisers — Blanche, of course, was the closest of them all - and that trust was never regained. That distrust was apparent in 1261, when Louis reorganised the household. There were draconian checks on Margaret's expenditure and almsgiving. She was not to receive gifts, nor to give orders to royal baillis or prévôts, or to undertake building works without the permission of the king. Her choice of members of her household was also subject to his agreement.

Margaret survived her husband by some thirty years, so that she herself was queen mother, to Philip III, and was still a presence ar court during the reign of her grandson Philip IV. But Louis did not make her regent on his second, and fatal, Crusade in 1270. In the early 12605 Margarer tried to persuade her young son, the future Philip III, to agree to obey her until he was thirty. When Philip told his father, Louis was horrified. In a strange echo of the events of 1241, he forced Philip to resile from his oath to his mother, and forced Margaret to agree never again to attempt such a move. Margaret had overplayed her hand. It meant that she was specifically prevented from acting with those full and legitimate powers of a crowned queen after the death of her husband that Blanche, like Eleanor of Aquitaine, had been able to deploy for the good of the realm.

Why was Margaret treated so differently from Blanche? Were attitudes to the power of women changing? Not yet. In 1294 Philip IV was prepared to name his queen, Joanna of Champagne-Navarre, as sole regent with full regal powers in the event of his son's succession as a minor. She conducted diplomatic negotiations for him. He often associated her with his kingship in his acts. And Philip IV wanted Joanna buried among the kings of France at Saint-Denis - though she herself chose burial with the Paris Franciscans. The effectiveness and evident importance to their husbands of Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor of Castile in England led David Carpenter to characterise late thirteenth-century England as a period of ‘resurgence in queenship’.

The problem for Margaret was personal, rather than institutional. Blanche had had her detractors at court. It is not clear who they were. There were always factions at courts, not least one that centred around Margaret, and anyone who had influence over a king would have detractors. They might have been clerks with misgivings about women in general, and powerful women in particular, and there may have been others who believed that the power of a queen should be curtailed, No one did curtail Blanche's — far from it. By the late chirteenth century the Capetian family were commissioning and promoting accounts of Louis IX that praise not just her firm and just rule as regent, but also her role as adviser and counsellor — her continuing influence — during his personal rule. As William of Saint-Pathus put it, because she was such a ‘sage et preude femme’, Louis always wanted ‘sa presence et son conseil’. But where Blanche was seen as the wisest and best provider of good advice that a king could have, a queen whose advice would always be for the good of the king and his realm, Margaret was seen by Louis as a queen at the centre of intrigue, whose advice would not be disinterested.

Surprisingly, such formidable policical players at the English court as Simon de Montfort and her nephew, the future Edward I, felt that it was worthwhile to do diplomatic business through Margaret. Initially, Henry III and Simon de Montfort chose Margaret, not Louis, to arbitrate between them. She was a more active diplomat than Joinville and the Lives of Louis suggest, and probably, where her aims coincided with her husband’s, quite effective.

To an extent the difference between Blanche’s and Margaret’s position and influence simply reflected political reality. Blanche was accused of sending rich gifts to her family in Spain, and advancing them within the court. But there was no danger that her cultivation of Castilian family connections could damage the interests of the Capetian realm. Margaret’s Provençal connections could. Her sister Eleanor was married to Henry III of England. Margaret and Eleanor undoubtedly attempted to bring about a rapprochement between the two kings. This was helpful once Louis himself had decided to come to an agreement with Henry in the late 1250s, but was perceived as meddlesome plotting in the 1240s. Moreover, Margaret’s sister Sanchia was married to Henry's younger brother, Richard of Cornwall, who claimed the county of Poitou, and her youngest sister, Beatrice, countess of Provence, was married to Charles of Anjou. Sanchia’s interests were in direct conflict with those of Alphonse of Poitiers; and Margaret herself felt that she had dowry claims in Provence, and alienated Charles by attempting to pursue them. Indeed, her ill-fated attempt to tie her son Philip to her included clauses that he would not ally himself with Charles of Anjou against her.

Lindy Grant- Blanche of Castile, Queen of France

#xiii#lindy grant#blanche of castile queen of france#blanche de castille#grégoire ix#innocent iv#raymond vii de toulouse#aliénor d'aquitaine#louis ix#philippe ii#guérin#louis viii#marguerite de provence#aliénor de provence#alphonse de poitiers#henry iii of england#philippe iii#jeanne i de navarre#philippe iv#simon de montfort#edward i of england#jean de joinville#sancia de provence#béatrice de provence#charles i d'anjou

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

↳ #qab22modern

"I can barely conceive of a type of beauty in which there is no Melancholy. We are weighed down, every moment, by the conception and the sensation of Time. And there are but two means of escaping and forgetting this nightmare: pleasure and work. Pleasure consumes us. Work strengthens us. Let us choose. I should like the fields tinged with red, the rivers yellow and the trees painted blue. Nature has no imagination."

-Charles Baudelaire

#perioddramaedit#history#edit#history edit#modern au#modern aesthetic#modern edit#historical figures#au moodboard#moodboard#aesthetic#modernedit#eleanor of aquitaine#henry ii#plantagenet#joanna of castile#isabella of castile#juana la loca#richard iii#anne neville#charlize theron#tom bateman#jemima west#aneurin barnard#rachel skarsten#florence pugh#historyedit#qab22modern#15th century#english history

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

ISABEL 2012

Michelle Jenner as Isabel de Castilla

Rodolfo Sancho as Fernando II de Aragon

Pablo Derqui as Enrique IV de Castilla

Barbara Lennie as Juana de Portugal

#isabel tve#isabella of castile#ferdinand ii of aragon#Henry IV of Castile#Joan of Portugal#michelle jenner#rodolfo sancho#Pablo Derqui#Barbara Lennie

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

𝘐𝘴𝘢𝘣𝘦𝘭𝘭𝘢 𝘰𝘧 𝘊𝘢𝘴𝘵𝘪𝘭𝘦, 𝘍𝘦𝘳𝘥𝘪𝘯𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘈𝘳𝘢𝘨𝘰𝘯, 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘪𝘳 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥𝘳𝘦𝘯 + 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘪𝘳 𝘭𝘰𝘷𝘦𝘴

#isabella of castile#ferdinand ii of aragon#Isabel#Isabella of aragon#joanna the mad#joanna of castile#philip the handsome#catherine of aragon#henry viii#John of aragon#Maria of aragon#Manuel i of portugal#Michelle Jenner#Catalina de Aragon#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Below the cut I have made a list of each English and British monarch, the age of their mothers at their births, and which number pregnancy they were the result of. Particularly before the early modern era, the perception of Queens and childbearing is quite skewed, which prompted me to make this list. I started with William I as the Anglo-Saxon kings didn’t have enough information for this list.

House of Normandy

William I (b. c.1028)

Son of Herleva (b. c.1003)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 25 at birth.

William II (b. c.1057/60)

Son of Matilda of Flanders (b. c.1031)

Third pregnancy at minimum, although exact birth order is unclear.

Approx age 26/29 at birth.

Henry I (b. c.1068)

Son of Matilda of Flanders (b. c.1031)

Fourth pregnancy at minimum, more likely eighth or ninth, although exact birth order is unclear.

Approx age 37 at birth.

Matilda (b. 7 Feb 1102)

Daughter of Matilda of Scotland (b. c.1080)

First pregnancy, possibly second.

Approx age 22 at birth.

Stephen (b. c.1092/6)

Son of Adela of Normandy (b. c.1067)

Fifth pregnancy, although exact birth order is uncertain.

Approx age 25/29 at birth.

Henry II (b. 5 Mar 1133)

Son of Empress Matilda (b. 7 Feb 1102)

First pregnancy.

Age 31 at birth.

Richard I (b. 8 Sep 1157)

Son of Eleanor of Aquitaine (b. c.1122)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 35 at birth.

John (b. 24 Dec 1166)

Son of Eleanor of Aquitaine (b. c.1122)

Tenth pregnancy.

Approx age 44 at birth.

House of Plantagenet

Henry III (b. 1 Oct 1207)

Son of Isabella of Angoulême (b. c.1186/88)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 19/21 at birth.

Edward I (b. 17 Jun 1239)

Son of Eleanor of Provence (b. c.1223)

First pregnancy.

Age approx 16 at birth.

Edward II (b. 25 Apr 1284)

Son of Eleanor of Castile (b. c.1241)

Sixteenth pregnancy.

Approx age 43 at birth.

Edward III (b. 13 Nov 1312)

Son of Isabella of France (b. c.1295)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 17 at birth.

Richard II (b. 6 Jan 1367)

Son of Joan of Kent (b. 29 Sep 1326/7)

Seventh pregnancy.

Approx age 39/40 at birth.

House of Lancaster

Henry IV (b. c.Apr 1367)

Son of Blanche of Lancaster (b. 25 Mar 1342)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 25 at birth.

Henry V (b. 16 Sep 1386)

Son of Mary de Bohun (b. c.1369/70)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 16/17 at birth.

Henry VI (b. 6 Dec 1421)

Son of Catherine of Valois (b. 27 Oct 1401)

First pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

House of York

Edward IV (b. 28 Apr 1442)

Son of Cecily Neville (b. 3 May 1415)

Third pregnancy.

Age 26 at birth.

Edward V (b. 2 Nov 1470)

Son of Elizabeth Woodville (b. c.1437)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 33 at birth.

Richard III (b. 2 Oct 1452)

Son of Cecily Neville (b. 3 May 1415)

Eleventh pregnancy.

Age 37 at birth.

House of Tudor

Henry VII (b. 28 Jan 1457)

Son of Margaret Beaufort (b. 31 May 1443)

First pregnancy.

Age 13 at birth.

Henry VIII (b. 28 Jun 1491)

Son of Elizabeth of York (b. 11 Feb 1466)

Third pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Edward VI (b. 12 Oct 1537)

Son of Jane Seymour (b. c.1509)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 28 at birth.

Jane (b. c.1537)

Daughter of Frances Brandon (b. 16 Jul 1517)

Third pregnancy.

Approx age 20 at birth.

Mary I (b. 18 Feb 1516)

Daughter of Catherine of Aragon (b. 16 Dec 1485)

Fifth pregnancy.

Age 30 at birth.

Elizabeth I (b. 7 Sep 1533)

Daughter of Anne Boleyn (b. c.1501/7)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 26/32 at birth.

House of Stuart

James I (b. 19 Jun 1566)

Son of Mary I of Scotland (b. 8 Dec 1542)

First pregnancy.

Age 23 at birth.

Charles I (b. 19 Nov 1600)

Son of Anne of Denmark (b. 12 Dec 1574)

Fifth pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Charles II (b. 29 May 1630)

Son of Henrietta Maria of France (b. 25 Nov 1609)

Second pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

James II (14 Oct 1633)

Son of Henrietta Maria of France (b. 25 Nov 1609)

Fourth pregnancy.

Age 23 at birth.

William III (b. 4 Nov 1650)

Son of Mary, Princess Royal (b. 4 Nov 1631)

Second pregnancy.

Age 19 at birth.

Mary II (b. 30 Apr 1662)

Daughter of Anne Hyde (b. 12 Mar 1637)

Second pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Anne (b. 6 Feb 1665)

Daughter of Anne Hyde (b. 12 Mar 1637)

Fourth pregnancy.

Age 27 at birth.

House of Hanover

George I (b. 28 May 1660)

Son of Sophia of the Palatinate (b. 14 Oct 1630)

First pregnancy.

Age 30 at birth.

George II (b. 9 Nov 1683)

Son of Sophia Dorothea of Celle (b. 15 Sep 1666)

First pregnancy.

Age 17 at birth.

George III (b. 4 Jun 1738)

Son of Augusta of Saxe-Gotha (b. 30 Nov 1719)

Second pregnancy.

Age 18 at birth.

George IV (b. 12 Aug 1762)

Son of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (b. 19 May 1744)

First pregnancy.

Age 18 at birth.

William IV (b. 21 Aug 1765)

Son of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (b. 19 May 1744)

Third pregnancy.

Age 21 at birth.

Victoria (b. 24 May 1819)

Daughter of Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saafield (b. 17 Aug 1786)

Third pregnancy.

Age 32 at birth.

Edward VII (b. 9 Nov 1841)

Daughter of Victoria of the United Kingdom (b. 24 May 1819)

Second pregnancy.

Age 22 at birth.

House of Windsor

George V (b. 3 Jun 1865)

Son of Alexandra of Denmark (b. 1 Dec 1844)

Second pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

Edward VIII (b. 23 Jun 1894)

Son of Mary of Teck (b. 26 May 1867)

First pregnancy.

Age 27 at birth.

George VI (b. 14 Dec 1895)

Son of Mary of Teck (b. 26 May 1867)

Second pregnancy.

Age 28 at birth.

Elizabeth II (b. 21 Apr 1926)

Daughter of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (b. 4 Aug 1900)

First pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Charles III (b. 14 Nov 1948)

Son of Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom (b. 21 Apr 1926)

First pregnancy.

Age 22 at birth.

364 notes

·

View notes

Text

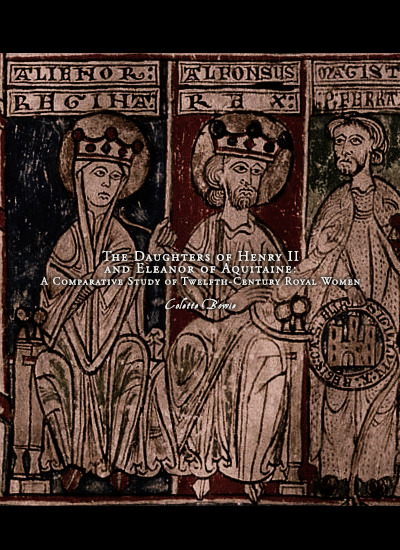

Favorite History Books || The Daughters of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine: A Comparative Study of Twelfth-Century Royal Women by Colette Bowie ★★★★☆

This study compares and contrasts the experiences of the three daughters of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. The exogamous marriages of Matilda, Leonor, and Joanna, which created dynastic links between the Angevin realm and Saxony, Castile, Sicily and Toulouse, served to further the political and diplomatic ambitions of their parents and spouses. It might be expected that their choices in religious patronage and dynastic commemoration would follow the customs and patterns of their marital families, yet the patronage and commemorative programmes of Matilda, Leonor, and Joanna provide evidence of possible influence from their natal family which suggests a coherent sense of family consciousness.

To discern why this might be the case, an examination of the childhoods of these women has been undertaken (Part I), to establish what emotional ties to their natal family may have been formed at this impressionable time. In Part II, the political motivations for their marriages are analysed, demonstrating the importance of these dynastic alliances, as well as highlighting cultural differences and similarities between the courts of Saxony, Castile, Sicily, and the Angevin realm. Dowry and dower portions (Part III) are important indicators of the power and strength of both their natal and marital families, and give an idea of the access to economic resources which could provide financial means for patronage. Having established possible emotional ties to their natal family, and the actual material resources at their disposal, the book moves on to an examination of the patronage and dynastic commemorations of Matilda, Leonor and Joanna (Parts IV-V), in order to discern patterns or parallels. Their possible involvement in the burgeoning cult of Thomas Becket, their patronage of Fontevrault Abbey, the names they gave to their children, and finally the ways in which they and their immediate families were buried, suggest that all three women were, to varying degrees, able to transplant Angevin family customs to their marital lands. The resulting study, the first of its kind to consider these women in an intergenerational dynastic context, advances the hypothesis that there may have been stronger emotional ties within the Angevin family than has previously been allowed for.

#historyedit#history books#litedit#house of plantagenet#english history#medieval#french history#european history#women's history#history#nanshe's graphics

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ages of English Queens at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list. For this reason, women such as Philippa of Hainault and Anne Boleyn have been omitted.

This list is composed of Queens of England when it was a sovereign state, prior to the Acts of Union in 1707. Using the youngest possible age for each woman, the average age at first marriage was 17.

Eadgifu (Edgiva/Ediva) of Kent, third and final wife of Edward the Elder: age 17 when she married in 919 CE

Ælfthryth (Alfrida/Elfrida), second wife of Edgar the Peaceful: age 19/20 when she married in 964/965 CE

Emma of Normandy, second wife of Æthelred the Unready: age 18 when she married in 1002 CE

Ælfgifu of Northampton, first wife of Cnut the Great: age 23/24 when she married in 1013/1014 CE

Edith of Wessex, wife of Edward the Confessor: age 20 when she married in 1045 CE

Matilda of Flanders, wife of William the Conqueror: age 20/21 when she married in 1031/1032 CE

Matilda of Scotland, first wife of Henry I: age 20 when she married in 1100 CE

Adeliza of Louvain, second wife of Henry I: age 18 when she married in 1121 CE

Matilda of Boulogne, wife of Stephen: age 20 when she married in 1125 CE

Empress Matilda, wife of Henry V, HRE, and later Geoffrey V of Anjou: age 12 when she married Henry in 1114 CE

Eleanor of Aquitaine, first wife of Louis VII of France and later Henry II of England: age 15 when she married Louis in 1137 CE

Isabella of Gloucester, first wife of John Lackland: age 15/16 when she married John in 1189 CE

Isabella of Angoulême, second wife of John Lackland: between the ages of 12-14 when she married John in 1200 CE

Eleanor of Provence, wife of Henry III: age 13 when she married Henry in 1236 CE

Eleanor of Castile, first wife of Edward I: age 13 when she married Edward in 1254 CE

Margaret of France, second wife of Edward I: age 20 when she married Edward in 1299 CE

Isabella of France, wife of Edward II: age 13 when she married Edward in 1308 CE

Anne of Bohemia, first wife of Richard II: age 16 when she married Richard in 1382 CE

Isabella of Valois, second wife of Richard II: age 6 when she married Richard in 1396 CE

Joanna of Navarre, wife of John IV of Brittany, second wife of Henry IV: age 18 when she married John in 1386 CE

Catherine of Valois, wife of Henry V: age 19 when she married Henry in 1420 CE

Margaret of Anjou, wife of Henry VI: age 15 when she married Henry in 1445 CE

Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Sir John Grey and later Edward IV: age 15 when she married John in 1452 CE

Anne Neville, wife of Edward of Lancaster and later Richard III: age 14 when she married Edward in 1470 CE

Elizabeth of York, wife of Henry VII: age 20 when she married Henry in 1486 CE

Catherine of Aragon, wife of Arthur Tudor and later Henry VIII: age 15 when she married Arthur in 1501 CE

Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII: age 24 when she married Henry in 1536 CE

Anne of Cleves, fourth wife of Henry VIII: age 25 when she married Henry in 1540 CE

Catherine Howard, fifth wife of Henry VIII: age 17 when she married Henry in 1540 CE

Jane Grey, wife of Guildford Dudley: age 16/17 when she married Guildford in 1553 CE

Mary I, wife of Philip II of Spain: age 38 when she married Philip in 1554 CE

Anne of Denmark, wife of James VI & I: age 15 when she married James in 1589 CE

Henrietta Maria of France, wife of Charles I: age 16 when she married Charles in 1625 CE

Catherine of Braganza, wife of Charles II: age 24 when she married Charles in 1662 CE

Anne Hyde, first wife of James II & VII: age 23 when she married James in 1660 CE

Mary of Modena, second wife of James II & VII: age 15 when she married James in 1673 CE

Mary II of England, wife of William III: age 15 when she married William in 1677 CE

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drawing of Henry VI of England by Jörg von Ehingen.

From 1457-1459, Swabian knight Jörg von Ehingen traveled Europe participating in various campaigns; throughout, he kept a journal and sketchbook of his impressions of the many royal courts he passed through. His compilation includes portraits, in the order of his visits, of Duke Ladislaus V of Austria, Charles VII of France, Henry IV of Castile, Henry VI of England, Alfonso V of Portugal, Janus III of Cyprus, Duke René of Anjou, John II of Aragon, and James II of Scotland.

#we love a contemporaneous portrait from an eyewitness#absolutely dapper hat#you may be familiar with Alfonso V's incredible poulaine shoes and/or his terrible heraldic lion#Henry's got pretty swell poulaines himself#altho I have just noticed his lil skelly hands#plantagenets#manuscript

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I of Castile (1451-1504), was Queen of Castile (r. 1474-1504) and of Aragon (r. 1479-1504) alongside her husband Ferdinand II of Aragon (1452-1516). Her reign included the unification of Spain, the reconquest of Granada, sponsoring Christopher Columbus in his voyage to explore the Caribbean, and the establishment of the Spanish Inquisition.

Early Life

Isabella was born 22 April 1451 in the town of Madrigal de las Altas Torres in Castile (which is now modern Spain) to John II of Castile (r. 1406-1454) and Isabella of Portugal (1447-1454). Despite having two brothers and spending much time with her mother in Arévalo where she participated in more ladylike activities, Isabella was soon drawn in and involved with the Castilian political world. While there were no laws against women being on the throne, Isabella was third in line because her brothers were higher up the succession line. The iron-willed and determined young woman was brought to the Court of Castile when she was in her early teenage years so that her father could keep an eye on her. Isabella was well-versed in Latin, and she studied history and theology, which furthered her religious convictions, which would be extremely influential in her actions as queen in the future.

Isabella's brother Enrique IV became king as Henry IV of Castile (r. 1454-1474), but discontent with his rule soon became vocalized as the kingdom was dissatisfied with his ineffective rule. Henry struggled with producing a legitimate heir, as his first marriage bore no children, and his only daughter, Juana (1462-1530), was believed to be an illegitimate child. He was unable to win back Granada, which had been under Muslim control since the mid-1200s, and had Jewish and Muslim advisors in place, damaging the image of Castile being a Christian kingdom.

To placate the nobles, Henry named his brother Alfonso (1453-1468) heir, but Alfonso had to marry his daughter so they could both rule. When Henry ultimately reneged on this deal and supported his daughter's claim, the nobles began their campaign to place Alfonso on the throne. When Alfonso died in 1468, of suspected poisoning, the nobles approached Isabella as she was also a legitimate candidate. She refused to take the crown and wished to wait for her brother to leave. Seeing this, Henry negotiated with the nobles and made Isabella his heir.

Continue reading...

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

#JON SNOW FORTNIGHT EVENT 2023

@asoiafcanonjonsnow

DAY 10: ECHOES OF THE PAST 🗝️📜(2/2) ->

Historical parallels with Medieval bastard Kings.

John I of Portugal

To complete the the previous post of this meta, we're going to dive in the parallels and simmilarities between Jon Snow and John I of Portugal through the following points:

BASTARDY

John I of Portugal also known as John of Avis, was the bastard son of King Peter I of Portugal and Teresa Guille Lourenço, a Galician noblewoman, lady in waiting of Inês de Castro, or according to other sources, the daughter of some Lisbon merchants.

Jon Snow is officially known to be Ned Stark's bastard son, and if we consider R+L=J, he's Prince Rhaegar and Lyanna's son, and as far as we know Jon is still a bastard.

PARENT'S TRAGIC LOVE STORY

John I's father, Peter I of Portugal fell in love with Inês, a lady in waiting and cousin of Constanza Manuel de Villena (Peter's wife).

After Constanza died, they became lovers and they had four children and they wed in secret, but some Portuguese nobles and Peter's father, Afonso IV of Portugal, disliked their relationship because the possible influences of Inês' family. They plotted to kill her, Inés was killed by three of those men and it's said that when Peter became king, he put Inês' corpse in a throne next to him so that the people would swear allegiance to her as queen of Portugal and looked for revenge chasing the ones who killed Inês. John I was born a few years after Inês died when Peter I had an affair with Teresa Lourenço.

Jon's parents, Rhaegar and Lyanna met at the Harrenhal Tourney, in which both participated, Lyanna as the Knight of the Laughing Tree, Aerys sent Rhaegar some men to learn the identity of the mystery knight, so it's likely that Rhaegar figure it out and then crowned her as Queen of Love and Beauty when he won the tourney. They fell in love and run away together, Rhaegar died at the Battle of the Trident during Robert's rebellion and Lyanna died after giving birth to Jon at the Tower of Joy.

BROTHER IS THE KING

After Peter I of Portugal died, he was succeeded by his son with Constanza Manuel de Villena, Ferdinand I, and John held a prominent position during the reign of his brother.

Jon is a brother of the Night's Watch when Robb is proclaimed as King in the North and during his brief reign.

Apart from that it would be argued that Aegon VI fits here too because he's Jon's brother, but Young Griff's identity as Aegon VI is doubtful and he hasn't taken control of Westeros yet.

MILITAR EDUCATION AND CAREER

John was educated by Nuno Freire de Andrade, Master of the Order of Christ, and John became Master of the Order of Avís, one of the most important Orders in Portugal during the Middle Ages, from which he will take his last name.

Jon joined the Night's Watch, which can also be considered a militar order in which chastity is also imposed on its members just like the Order of Avis. Jeor Mormont, Lord Commander of the Night's Watch has been one of Jon's mentors, so just like John, Jon had the leader of a militar order as a mentor, and then became the head of a militar order.

RELATIONSHIPS/LOVE INTERESTS

While John formed part of the Order of Avis, despite vows of chastity, John had two bastard children with Inês Pires when he was a teenager, Beatrice and Afonso, 1st Duke of Braganza.

Jon broke his vows by falling in love and being with Ygritte, even though Jon didn't had children with Ygritte, and Jon has also expressed that he didn't want to have them because of the stigma of being a bastard and the classist Westerosi society.

POLITICAL MATCH MAKER

John was one of the negotiators of the successive marriage projects of his niece and the heiress Beatrice of Portugal, who would end up marrying John I of Castile (Henry II of Castile's son), as a way to seal peace after the Fernandine Wars, in which Ferdinand I tried to overthrow Henry II from the Castilian throne, who became king after killing his legitimate brother Peter I of Castile (who was Ferdinand I's cousin), and was supported by one of Peter I's legitimised bastard children, Constance of Castile.

In the agreements established that each one would independently reign their kingdoms and the offspring of both would inherit Portugal, although if Beatrice died without children, the heirs of her husband would inherit Portugal, and John I of Castile has children from a previous marriage to Eleanor of Aragon (this is important detail for later).

Jon has also arranged a wedding of a familiar during his time as head of the militar institucional, as the Karstarks originated as a cadet branch of the Starks, and there have been intermarriages between the two houses, so we could assume Alys and Jon are distant cousins, such as Alys and Sigorn's wedding.

PROBLEMS OF SUCESSION AND INDEPENDENCE OF THEIR KINGDOMS & THEIR RISE TO KINGSHIP

After the death of Ferdinand I, a succession crisis took place in Portugal between Beatrice, who had no offspring, and the children of Peter I of Portugal with Inés de Castro (who were considered bastards by the Portuguese nobility), and also John revolted at end of 1384 with the support of the commonfolk and the bourgeoisie, and promoted a war to maintain the independence of Portugal, adopting the title of defender of the kingdom, which he achieved by defeating Beatrice and John I of Castile, for which he was crowned king of Portugal, being the first king and founder of the House of Avis.

Due to what happened to John with the fight for the independence of Portugal against another family member, it is most likely that in TWOW when Jon arrives in Winterfell the inheritance problem between the Starklings will have to be solved, and with Robb's will and his position as the older brother and being the one with political experience, supported by the Free Folk, the Mountain Clans and some Northern Noble Houses like the recently created House of Thenn, formed by Alys and Sigorn, Jon will be named king in the North breaking relations with the Iron Throne that is under the control of the Lannisters and the North will be (for the moment) independent again. In addition, the matter of Beatrice and her husband John I of Castile reminds me a bit of the marriage of Sansa and Tyrion, being Tywin's initial plan to get the North under the rule of the Lannisters, although that did not work and the best method was having the Boltons at Winterfell. Plus both Tyrion and John I of Castile have lions in their sigils, although the Castilian lion is purple (or in some media, red) and the Lannister one is golden.

ALLIANCES, MARRIAGE & OFFSPRING/POSSIBLE MARRIAGE (SPECULATIONS)

Like his brother Ferdinand I, John supported Constance's cause, allying with her against John I of Castile, but they were defeated and Constance did not get the Castilian throne, her daughter Catherine of Lancaster married John I of Castile's son, Henry III, and their son was John II of Castile, thus uniting the two lines of succession of Alfonso XI of Castile.

As well as Peter I of Castile's two eldest surviving daughters married two of Edward III of England's sons (Constance married John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster and Isabella married Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York), John I of Portugal married Philippa of Lancaster, John of Gaunt's eldest daughter with Blanche of Lancaster, and they had a loving marriage and eight children: Blanche, Afonso, Edward I of Portugal, Peter, Henry, Isabella, John and Ferdinand.

Edward was a poet and writer, his more important books were, on good governance,'The Loyal Counselor', 'Book of Councils', 'Response, being princes, to the infant D. Ferdinand about some complaints he had of his father'; on sports and horsemanship, with educational connotations, 'Teaching book about riding well in any saddle' and "Regiment to learn to play weapons'.

It's very likely that Jon will need to make more alliances to stablish his position as King in The North and preparing for the War for the Dawn and fight against the Others, and one way to do it it would be marrying someone with a prominent influence and a big army.

And although Dany hasn't landed on Westeros yet, due to her army and her influence as queen claimant to the Iron Throne, could be a good ally, and Dany would like to help due to her care for people who are needed, so probably Jon and Dany would join forces and eventually they could fall in love, marry and rule Westeros together.

Plus, if Jon ans Dany have children, one of them could be a poet like Edward I or a music composer and a bookworm like Rhaegar.

CUNNING/KNOWLEDGE

Contemporary writers state John that his position as a master of a religious military order made him an exceptionally learned king for the Middle Ages. His love for knowledge and culture was passed down to his children, who are collectively referred to by Portuguese historians as the illustrious generation, for example, Edward I the Eloquent and Peter were considered as two of the most learned princes of their time, and Henry the Sailor invested heavily in science and in the development of nautical activities.

Although Jon is often seen as a warrior, he has shown interest on knowledge and books too and he has been showing competences and skills for being a good leader and he's cunning good at politics and a good administrator, as he has been proving during his time as Lord Commander of the Night's Watch.

DRAGON IMAGERY

John I of Portugal's sigil has some elements that make me link him with Jon, his emblem has a crest with a dragon, which was usually used in the heraldry of the Portuguese Royal family, in which a dragon appears in the Royal crest or two green dragons as the supports of coat of arms, which makes me think of Rhaegal, a green dragon, who was named after Rhaegar and most likely Jon is its dragonrider.

#jonsnowfortnightevent2023#jonsnowfortnightevent#jon snow#meta#canonjonsnow#canonjon#jon meta#asoiaf meta#day 10#echoes of the past#historical parallels#john i of portugal#João I#medieval bastard kings

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

"To all intents and purposes she may be counted among the kings of France"

The hour that struck the death of Louis VIII was arguably the most critical in the history of the Capetian family. The new king, one day to be St Louis, was still a child. The trend of events in the previous two reigns had brought the higher nobility to realise that its independence would soon be seriously threatened. But a unique opportunity was raised to the regency of the queen-mother, Blanche of Castile, on the pretext that she was a woman and a foreigner. Yet this was not the first occasion on which the king's widow had acted as regent, nor the first on which a queen had played a part in politics. Philip Augustus had been the first Capetian not to involve his wife in the government of his realm. Before his time the queens of France had often intervened in affairs of state. Constance of Arles, not content with making married life difficult for Robert the Pious, had wanted to change the order of succession to the throne. She had led the opposition to Henri I, provoking and upholding his brothers against him, and she was perhaps responsible for the separation of Burgundy from the royal domain, to which Robert the Pious had joined it. Anna of Kiev, after the death of her husband Henri I, had been one of the regents, and it was only her second marriage, to Raoul de Crépy, that took her out of politics. Bertrada de Montfort's influence over Philip I had been notorious, and so had her hostility to the heir to the throne, whom she had even been accused of trying to poison. Adelaide of Maurienne, despite a physical personality before which Count Baldwin III of Hainault is said to have recoiled, had held considerable sway over Louis VI, procuring the disgrace of the chancellor, Etienne de Garlande, and egging on Louis to the Flemish adventure from which her brother-in-law, William Clito, was to profit so much. Eleanor of Aquitaine- as St Bernard had complained- had more power than anyone else over Louis VII as long as their marriage lasted. Louis VII's third wife, Adela of Champagne, had appealed to the king of England for help against her son Philip Augustus when he had sought to free himself of the tutelage of her brothers of Champagne. Later, reconciled with Philip, Adela had been regent during his absence from France on crusade. From the beginnings of Capet rule, the queens of France had enjoyed substantial influence over their husbands and over royal policy.

But Blanche of Castile was to play a greater role than any of her predecessors. To all intents and purposes she may be counted among the kings of France. For from 1226 until her death in 1252 she governed the kingdom. Twice she was regent: from 1226 to 1234, while Louis IX was a minor, and from 1248 to 1252 during his first absence on crusade. Between 1234 and 1248 Blanche bore no official title, but her power was no less effective. Severe in personality, heroic in stature, this Spanish princess took control of the fortunes of the dynasty and the kingdom in outstandingly difficult circumstances. For in 1226 there arose the most redoubtable coalition of great barons which the House of Capet ever had to face. Loyalty to the crown, so constant a feature of the past, seemed to be in eclipse. This was at any rate true of the barons who revolted, for they appear to have tried to seize the person of the young king himself- an attempt without parallel in Capetian history.

Blanche of Castile threw herself energetically into the struggle over her son and his throne. Taking her father-in-law, Philip Augustus, as her model, she won over half her enemies by craft, vigorously gave battle to the rest, and enlisted the alliance of the Church, including the Pope himself, and of the burgess class, which in marked fashion took the side of the royal family. Blanche was able to fend off Henry III of England, who tried to take the opportunity of recovering his ancestral lands, lost by John to Philip Augustus. She broke up the baronial coalition and reduced to submission the most dangerous of the rebels, Peter Mauclerc, Count of Brittany, and Raymond VII, Count of Toulouse. She adroitly took advantage of her victory to re-establish- this time definitively- the royal power in the south of France: her son Alphonse was married to the daughter and heiress of Raymond of Toulouse. The way was now open for the union of all Raymond's rich patrimony with the royal domain.

The Capetian monarchy emerged all the stronger from a crisis which had threatened to overwhelm it. Blanche felt it her duty not to rest on her laurels. After her son came of age she continued to make herself responsible for good and stable government. By the force of her example she drove home the lessons which Philip Augustus seems to have wanted to press upon his grandson when they had talked together. To Blanche's initiative must be credited the measures taken to suppress the dangerous revolt of Trencavel in Languedoc, as also those taken to defeat the coalition broken up after the battle of Saintes. On these occasions Louis IX did no more than carry out his mother's policy. When he went off on crusade, Blanche one more officially shouldered the government of the kingdom. She maintained law and order, prevented the further outbreak of war with England, and successfully pressed on with the policy which was to lead to the annexation of Languedoc. Likewise it was she who refurnished her son's crusade with men and money, and she took all the steps necessary for the safety of the kingdom when Louis was captured in Egypt.

Robert Fawtier- The Capetian Kings of France- Monarchy and Nation (987-1328)

#xiii#robert fawtier#the capetian kings of france#blanche de castille#queens of france#regents#louis viii#louis ix#philippe ii#constance d'arles#robert ii#henri i#anne de kiev#philippe i#bertrade de montfort#adélaïde de savoie#louis vii#étienne de garlande#st bernard#aliénor d'aquitaine#adèle de champagne

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

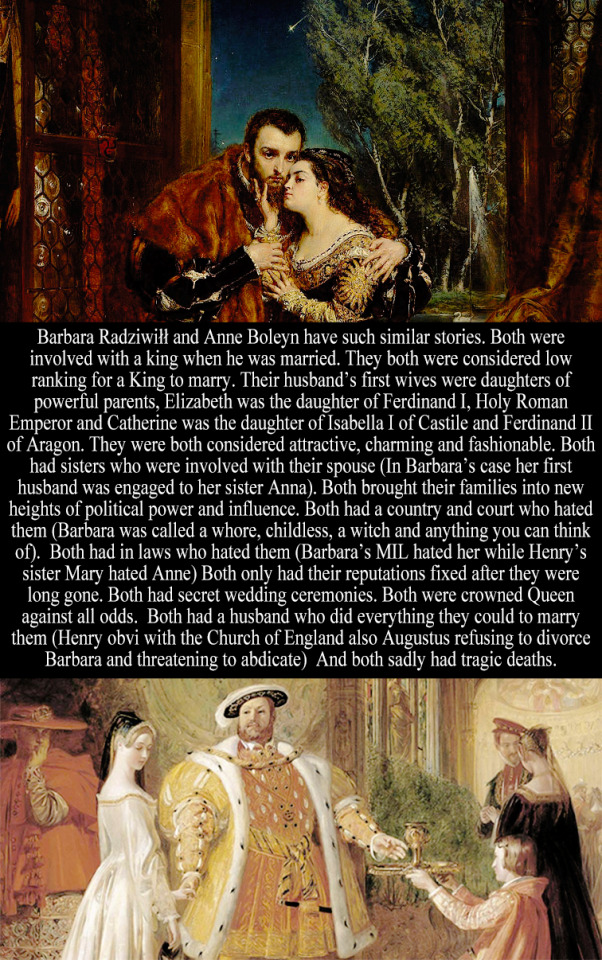

“Barbara Radziwiłł and Anne Boleyn have such similar stories. Both were involved with a king when he was married. They both were considered low ranking for a King to marry. Their husband’s first wives were daughters of powerful parents, Elizabeth was the daughter of Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor and Catherine was the daughter of Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon. They were both considered attractive, charming and fashionable. Both had sisters who were involved with their spouse (In Barbara’s case her first husband was engaged to her sister Anna). Both brought their families into new heights of political power and influence. Both had a country and court who hated them (Barbara was called a whore, childless, a witch and anything you can think of). Both had in laws who hated them (Barbara’s MIL hated her while Henry’s sister Mary hated Anne) Both only had their reputations fixed after they were long gone. Both had secret wedding ceremonies. Both were crowned Queen against all odds. Both had a husband who did everything they could to marry them (Henry obvi with the Church of England also Augustus refusing to divorce Barbara and threatening to abdicate) And both sadly had tragic deaths.” - Submitted by Anonymous

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day in 1501 - Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales marries Catherine of Aragon.

The marriage between the heir to the English throne and the daughter of Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon had been arranged as part of the Treaty of Medina del Campo in 1489 and the two were married by-proxy in 1499. Two years later, in 1501, 15 year old Catherine left Spain for England where she met her future husband on the 4th November. Ten days later, the pair married in a spectacular ceremony in St. Paul’s Cathedral. One month after their wedding, the newlyweds left London for Ludlow Castle to live. Sadly, in early 1502, both Arthur and Catherine fell ill with the sweating sickness and while Catherine would recover, Arthur would not, he died on 2nd April 1502.

Catherine would spend the next seven years in limbo, following disputes over her dowry between her father and father-in-law. In 1507, she became the Aragonese ambassador to England, the first female ambassador in European history. Following the death of Henry VII, Catherine married his younger son, now Henry VIII, on 11 June 1509.

During the ‘Kings Great Matter’ in the mid-to-late 1520’s , Henry would use Catherine’s marriage to Arthur two decades earlier to argue for an annulment of his marriage, citing a biblical passage from Leviticus, which calls a man’s marriage to his brothers widow an ‘act of impurity’, and that therefore his marriage to Catherine was invalid.

#History#Tudor History#Catherine of Aragon#Arthur Tudor#Prince Arthur#The Spanish Princess#On this day in history#any mistakes please feel free to correct me#my post

79 notes

·

View notes