#lessons with kiarostami

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Abbas Kiarostami, pg 89 of Lessons with Kiarostami

#art#artists#quotes#literature#lit scraps#abbas kiarostami#kiarostami#lessons with kiarostami#film#filmmaking#iranian artist#iranian#filmmaker#writer

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

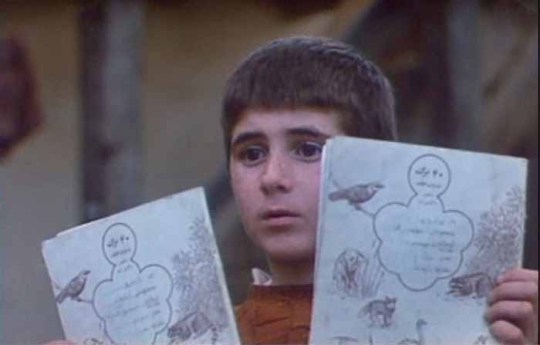

I’ve Got Something to Say that Only You Children Would Believe, 1969. A book illustrated by Abbas Kiarostami and written by Ahmad Reza Ahmadi. Tehran, Iran: Kanoon (Center of Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults/کانون پرورش فکری کودک و نوجوان). You can download a PDF version of the book here.

Abbas Kiarostami had a long, colourful career as an illustrator, graphic and film title sequence designer, and photographer before his career as a filmmaker got kick-started in the early 1970s.

His slow success and even a slower international recognition meant that this first part of his artistic life had vert little chance to be appreciated in time and not surprisingly, it was overlooked even by his ardent audience. One could argue, his eventual coming back to these fields (plus poetry and installation) in the 21th century was itself a classic case of Kiarostamian "return" as often seen in his films: returning to a home, to a place, to a landscape, in this case, to old passions.

A great portion of the achievements of these early years remain unavailable but here we have a wonderful example of his illustration work which he contributed to a children book, written by modernist poet and author Ahmad Reza Ahmadi.

There is another interesting story about the book: Attached at the end of the PDF file are letters from the Ministry of Culture demanding changes (i.e. censoring) for the second edition of the book which came out in 1971. I can't still figure out what made the censor sensitive to the content on pages 6 and 20 but if there's a lesson in this, it's that censorship in Iran has always been as stupid and pointless as it is today.

Special thanks to Morteza Seyyedi-Nejad who has scanned and shared online this rare and precious publication.

↘︎ Posted by Ehsan Khoshbakht: https://notesoncinematograph.blogspot.com/2020/03/Kiarostami-book.html

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Serpent's Skin': How Hajir Darioush's breakthrough movie birthed the Iranian New Wave

Joe Willams WED 6TH SEP 2023 21.15 BST

Before the mid-1960s, the cinema of Iran was characterised mainly by a certain degree of moral and ideological simplicity. The popular genre of Filmfarsi, which dominated even until the late 1970s, usually presented melodramas or comedies with stereotypical characters and straightforward moral lessons. Such films, like Esmail Koushan’s Pretty Foe, rarely ventured into socio-political critique or complex storytelling – they used simple ‘comedy of errors’ plotlines and generally played for laughs or romance.

Similarly, movies produced during the Pahlavi era often echoed state-endorsed ideologies, emphasising the virtues of modernisation and Westernisation in line with the Shah’s own policies. While exceptions like Ebrahim Golestan’s The Brick and the Mirror offered more intellectual engagement, they were outliers in a landscape primarily focused on entertainment or state-sanctioned themes. This was just over a decade before Iran’s cultural revolution of 1980, which replaced secularism with a strict form of political and religious Islam.

So, when Hajir Darioush’s Serpent’s Skin emerged in 1964, it marked a radical departure from the norm. Darioush’s audacious storytelling and nuanced direction introduced a new level of sophistication that was virtually unheard of in Iranian cinema at the time. The film encouraged audiences to engage in critical thought, question the status quo, and explore the grey areas of morality and identity.

Based on DH Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Dariosh’s experimental short work follows a middle-aged modern Iranian woman confronted with her own age after striking up a tentative romance with a much younger man. The technical aspects of Serpent’s Skin also marked a massive divergence from established norms.

Darioush opted for a minimalist approach, with meticulous framing and subtle lighting that lent the movie a raw emotional gravity and frequently intercut between multiple narrators to paint a more vivid picture of contemporary Iran. These elements contrasted sharply with the high-octane visuals and melodramatic performances characteristic of Filmfarsi and other mainstream Iranian productions.

The influence of Serpent’s Skin on the Iranian New Wave was profound. The groundbreaking work of Darioush inspired upcoming directors like Abbas Kiarostami, Jafar Panahi, and Asghar Farhadi. They would go on to adopt and further refine the storytelling techniques and technical prowess that Serpent’s Skin had pioneered. Films like Kiarostami’s 1990 Close-Up or Panahi’s The Circle, which came a year later, would continue to challenge and provoke both Iranian and international audiences, just as Darioush had done.

Nearly six decades later, Serpent’s Skin remains a touchstone for scholars, critics, and auteurs who explore the complex landscape of Iranian culture and cinematic expression. Its impact on the Iranian New Wave has been enduring, paving the way for seminal entries to Iranian cinema like Ana Lily Amirpour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, marking it not just as a groundbreaking film but as a historical landmark that redefined what the country’s cinema could be.

#Iran#Cinema#New Wave#Hajir Darioush#Serpent's Skin#Filmfarsi#Esmail Koushan#Ebrahim Golestan#Abbas Kiarostami#Jafar Panahi#Asghar Farhadi#Far Out Magazine

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where is the Friend's Home? (Khane-ye doust kodjast?) (1987)

A characteristic that is lacking in mainstream Hollywood films is a plot that is so simply told, but excites you at the same time. Abbas Kiarostami’s “Where Is the Friend’s House?” involves a basic goal that expands into a 80 minute character study about what it takes to maintain selflessness at a young age and the finished product is one of world cinema’s hidden secrets.

On a somewhat uneventful day in a school classroom, Mohamed Reda (Ahmed Ahmed Poor) is scolded for repeatedly misplacing his notebook and is warned that he will be expelled if he does so one more time. By accident, his classmate and good friend Ahmed (Babek Ahmed Poor) takes Mohamed’s notebook and is desperate to return it to him to prevent his friend’s expulsion. What transpires is an arduous journey that Ahmed undertakes to find Mohamed’s home on the other side of town which will take him up stairs, hills and strangers’ backyards.

This film isn’t solely about Ahmed’s journey, but about his fellow countrymen’s everyday tasks as well. Kiarostami weaves these two storylines side by side with the right plot devices and overlapping dialogue. For example, there’s a scene involving a business transaction between two strangers over the installation of doors on one of their houses. At first, you wonder what the purpose of this scene is, and then the sewing of both stories come together when Ahmed reappears and the builder asks if he could tear a page from Mohamed’s notebook to draw up the contract. So at the same time, you see Ahmed’s selfless act and what he’ll most likely grow up to be in his adult years, continuing his selfless ways to help his fellow man.

“Where is the Friend's House?” is also a throwback to other films like “The Red Balloon” and “The Bicycle Thieves” that utilize the motif of a child fending for themselves in the streets. At the same time, it incorporates the theme of child actors acting like regular children that was previously done in “The 400 Blows”, “Forbidden Games” and “Spirit Of The Beehive” and later on in “Au Revoir, Les Enfants” “Cinema Paradiso” and “Ponette”. The result is a Venn Diagram of a film where the main story is the world through the eyes of a child who wants to make a man of himself, taking the lessons of his teacher and grandfather to heart, even doing something as foolish as running from home to unchartered lands to help a friend in need. The common bond between all these films is that they are non-Hollywood foreign language gems. American films are too caught up in stupid characters, cheesy CGI, convoluted stories and unnecessary subplots that are incorporated into remakes and monotonous superhero franchises. I have yet to wait for an American director to focus on a linear story that may seem boring on paper, but grabs the viewer’s attention nonstop as if you’re in the character’s shoes. This film is more reality than some of the garbage that passes as “reality” television.

The Ahmed Poor brothers who play Ahmed and Mohamed are excellent from the very beginning. The very first scene tugs at your heartstrings when Ahmed’s Mohamed is crying in class as he’s threatened with being expelled from school. He’s only a little kid and yet the weight of responsibility overwhelms him. I can remember seeing classmates of mine cry in school when confronted with similar issues and seeing that crying on screen brought me back to those halcyon days. Then you have Ahmed, whose presence takes up 95% of the film, and his determination is on full display. Babek’s Ahmed manages to stick to his innocence without coming off as overly cute. He may be a grammar school student, but he has the grit and drive of an adult. Not many films can pull off having a child act like him or herself without being nauseatingly annoying. The Ahmed Poor brothers were naturals to be in front of the camera and did not disappoint.

Unfortunately, Iran did not submit a film to the Academy Awards Foreign Film category in the year of this film’s release. By missing out of being in the running, “Where Is the Friend’s House?” could have been more widely seen by American audiences and the film wound up debuting at the American film festival circuit 6 years later, well too late for Oscar consideration. Despite that, Kiarostami won awards at the Fajr and Locarno Festivals in 1987 and 1989 respectively. As of now, the film is #2 on MUBI’s Top 1000 Films list, one up from “The Godfather”, an impressive feat. So 35 years later, this masterpiece is getting the reception it richly deserves.

9.5/10

#dannyreviews#where is the friend's house?#abbas kiarostami#iran#persia#persian#ahmed ahmed poor#babek hamed poor#children in film#homework#notebook#khane-ye doust kodjast?#world cinema#international film#foreign film

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Juliette Binoche was born on March 9, 1964. She is a French actress, artist, and dancer. She has appeared in more than 60 feature films and has been the recipient of numerous accolades, including an Academy Award, a British Academy Film Award, and a César Award.

Binoche began taking acting lessons during adolescence and, after performing in several stage productions, was cast in the films of such notable auteur directors as Jean-Luc Godard (Hail Mary, 1985), Jacques Doillon (Family Life, 1985), and André Téchiné; the latter would make her a star in France with the leading role in his drama Rendez-vous (1985). Her English-language film debut The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988), launched her to international prominence. Following her acclaimed role in Krzysztof Kieślowski's Three Colours: Blue (1993), a performance for which she won the César Award, and the Volpi Cup for Best Actress, Binoche garnered further international acclaim with Anthony Minghella's period romance The English Patient (1996), for which she won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress. For her performance in Lasse Hallström's romantic comedy Chocolat (2000), Binoche received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actress.

During the 2000s, she maintained a successful career, alternating between French and English language roles in both mainstream and art-house productions. In 2010, she won the Best Actress Award at the Cannes Film Festival for her role in Abbas Kiarostami's Certified Copy, making her the first actress to win the European "Best Actress Triple Crown" (for winning awards at the Berlin, Cannes, and Venice film festivals). She was also honored with the Maureen O'Hara Award at the Kerry Film Festival in 2010, an award is offered to women who have excelled in their chosen field in film.

Throughout her career, Binoche has intermittently appeared on stage, most notably in a 1998 London production of Luigi Pirandello's Naked and in a 2000 production of Harold Pinter's Betrayal on Broadway for which she was nominated for a Tony Award. In 2008, she began a world tour with a modern dance production in-i devised in collaboration with Akram Khan. Often referred to as "La Binoche" by the press, her other notable performances include: Mauvais Sang (1986), Les Amants du Pont-Neuf (1991), Damage (1992), The Horseman on the Roof (1995), Code Unknown (2000), Caché (2005), Breaking and Entering (2006), Flight of the Red Balloon (2007), Camille Claudel 1915 (2013), Clouds of Sils Maria (2014), and High Life (2018).

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Deserted Station (2002)

On a pilgrimage to Mashad from Tehran, a couple's transportation breaks down, far from any major town. The husband, a photographer, seeks help at a nearby village and encounters a teacher who offers to help. Whilst the husband and teacher go off to find a spare part, the wife, who used to be a teacher, takes over the teaching lessons in the village. It is clear that the children live there, in this strange deserted place, without any men, save the teacher and an old signal guard. As the day draws on, the children help to bring a new hope and life into the wife's heart.

Scripted by Kambuzia Partovi (based on a story by Abbas Kiarostami).

#The Deserted Station#Iran#Iranian cinema#Persian#Abbas Kiarostami#Kambuzia Partovi#Leila Hatami#Persian films#Iranian films#Iran cinema#Arabian cinema#cinema#filmmaking#old films#must see films#recommended movies#films to watch#underrated films#hidden gems#hiddengem films#hidden gem film#underrated#A Separation#Tehran#Motherhood#pregnancy#children

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

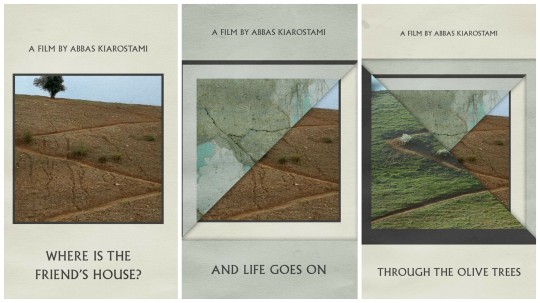

The 𝗞𝗼𝗸𝗲𝗿 trilogy:

Director: 𝗔𝗯𝗯𝗮𝘀 𝗞𝗶𝗮𝗿𝗼𝘀𝘁𝗮𝗺𝗶

- 𝗪𝗵𝗲𝗿𝗲 𝗶𝘀 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗙𝗿𝗶𝗲𝗻𝗱'𝘀 𝗛𝗼𝘂𝘀𝗲? (1987)

- 𝗔𝗻𝗱 𝗟𝗶𝗳𝗲 𝗚𝗼𝗲𝘀 𝗢𝗻 (1992)

- 𝗧𝗵𝗿𝗼𝘂𝗴𝗵 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗢𝗹𝗶𝘃𝗲 𝗧𝗿𝗲𝗲𝘀 (1994)

In each of his films, Kiarostami fought with the entirety of his being, just to get people to see themselves in each other.

It could be argued that "The Koker Trilogy" is only a trilogy in a superficial sense. Each subsequent film in the trilogy interrogates the film before it. They do build upon their thematic content, acknowledging the existence of the previous films while charting their course.

The three films don't really share characters or storylines, only actors. And the style of each one is entirely distinct from the others. Yet there is a shared texture and elements: the remote rural Iranian village of Koker and a shared concept: an emotional experience and a pathway into unseen lives.

"𝗪𝗵𝗲𝗿𝗲 𝗶𝘀 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗙𝗿𝗶𝗲𝗻𝗱'𝘀 𝗛𝗼𝘂𝘀𝗲?" is a heartbreaking neorealist adventure. It's the story of Ahmed, a thoughtful young child who sets out on a journey to return a school notebook he mistakenly took from his classmate Mohamed to prevent the student's unjust expulsion. After travelling all day across the village and between neighboorhoods, Ahmed is left desperate by adults who refuse to help.

Ahmed's arduous journey trekking up and down the hills feels colossal because Kiarostami never lets the viewer forget the moral urgency that the young boy feels.

Then soon after "𝗪𝗵𝗲𝗿𝗲 𝗶𝘀 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗙𝗿𝗶𝗲𝗻𝗱'𝘀 𝗛𝗼𝘂𝘀𝗲?", Iran was struck by a catastrophic earthquake in 1990, which left tens of thousands of dead people and many destructed villages and shattered communities like Koker.

In the wake of the earthquake, Kiarostami travelled from Tehran with his son to the village in order to discover the fate of the people he came to know during the production of the film. The trip resulted in the next film in the trilogy, "And Life Goes on" (aka Life, and nothing more..), in which a film director (Farhad as Kiarostami's persona) and his son Puya drive to Koker in search of the child actor.

On their trip they encounter many strange and familiar faces, all touched by the earthquake and the witness the spirit of life that pulls the people through in the after math.

As it happens, "𝗔𝗻𝗱 𝗟𝗶𝗳𝗲 𝗚𝗼𝗲𝘀 𝗢𝗻" led Kiarostami to the next and last film in the trilogy. "𝗧𝗵𝗿𝗼𝘂𝗴𝗵 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗢𝗹𝗶𝘃𝗲 𝗧𝗿𝗲𝗲𝘀" set during the filming of "𝗔𝗻𝗱 𝗟𝗶𝗳𝗲 𝗚𝗼𝗲𝘀 𝗢𝗻" in which Keshavare (Kiarostami's on screen second persona) guides the hand selected actors who appeared in the previous film, themselves locals devastated by the earthquake through the filming.

Kiarostami then focus on the main story of Hussein, a young man chosen to play a small role in "𝗔𝗻𝗱 𝗟𝗶𝗳𝗲 𝗚𝗼𝗲𝘀 𝗢𝗻" opposite to a young woman named Taheran with whom he has a romantic interest in off-screen.

Whether they are considered as a true trilogy or not, each film is an essential companion to the next, and each film is a vital moral lesson: serenity, grace, selflessness and hope.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

book recommendations?

Currently I would recommend:

Farsi books: Savushun by Simin Daneshvar (known most famous novel written by a woman in Iran), Lessons with Kiarostami written by himself (edited by Paul Cronin so I believe a good English version is out there somewhere)

English books: A Man Called Ove by Fredrik Backman and actually really enjoying Utopia for Realists by Rutger Bregman

Please feel free to add recommendations!

9 notes

·

View notes

Quote

1. Broken Blossoms or The Yellow Man and the Girl (Griffith, 1919) USA 2. Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari [The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari] (Wiene, 1920) Germany 3. Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler – Ein Bild der Zeit (Part 1 - Part 2) [Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler] (Lang, 1922) Germany 4. The Gold Rush (Chaplin, 1925) USA 5. La Chute de la Maison Usher [The Fall of the House of Usher] (Jean Epstein, 1928) France 6. Un Chien Andalou [An Andalusian Dog] (Bunuel, 1928) France 7. Morocco (von Sternberg, 1930) USA 8. Der Kongress Tanzt (Charell, 1931) Germany 9. Die 3groschenoper [The Threepenny Opera] (Pabst, 1931) Germany 10. Leise Flehen Meine Lieder [Lover Divine] (Forst, 1933) Austria/Germany 11. The Thin Man (Dyke, 1934) USA 12. Tonari no Yae-chan [My Little Neighbour, Yae] (Shimazu, 1934) Japan 13. Tange Sazen yowa: Hyakuman ryo no tsubo [Sazen Tange and the Pot Worth a Million Ryo] (Yamanaka, 1935) Japan 14. Akanishi Kakita [Capricious Young Men] (Itami, 1936) Japan 15. La Grande Illusion [The Grand Illusion] (Renoir, 1937) France 16. Stella Dallas (Vidor, 1937) USA 17. Tsuzurikata Kyoshitsu [Lessons in Essay] (Yamamoto, 1938) Japan 18. Tsuchi [Earth] (Uchida, 1939) Japan 19. Ninotchka (Lubitsch, 1939) USA 20. Ivan Groznyy I, Ivan Groznyy II: Boyarsky Zagovor [Ivan the Terrible Parts I and II] (Eisenstein, 1944-46) Soviet Union 21. My Darling Clementine (Ford, 1946) USA 22. It’s a Wonderful Life (Capra, 1946) USA 23. The Big Sleep (Hawks, 1946) USA 24. Ladri di Biciclette [The Bicycle Thief] [Bicycle Thieves] (De Sica, 1948) Italy 25. Aoi sanmyaku [The Green Mountains] (Imai, 1949) Japan 26. The Third Man (Reed, 1949) UK 27. Banshun [Late Spring] (Ozu, 1949) Japan 28. Orpheus (Cocteau, 1949) France 29. Karumen kokyo ni kaeru [Carmen Comes Home] (Kinoshita, 1951) Japan 30. A Streetcar Named Desire (Kazan, 1951) USA 31. Thérèse Raquin [The Adultress] (Carne 1953) France 32. Saikaku ichidai onna [The Life of Oharu] (Mizoguchi, 1952) Japan 33. Viaggio in Italia [Journey to Italy] (Rossellini, 1953) Italy 34. Gojira [Godzilla] (Honda, 1954) Japan 35. La Strada (Fellini, 1954) Italy 36. Ukigumo [Floating Clouds] (Naruse, 1955) Japan 37. Pather Panchali [Song of the Road] (Ray, 1955) India 38. Daddy Long Legs (Negulesco, 1955) USA 39. The Proud Ones (Webb, 1956) USA 40. Bakumatsu taiyoden [Sun in the Last Days of the Shogunate] (Kawashima, 1957) Japan 41. The Young Lions (Dmytryk, 1957) USA 42. Les Cousins [The Cousins] (Chabrol, 1959) France 43. Les Quarte Cents Coups [The 400 Blows] (Truffaut, 1959) France 44. A bout de Souffle [Breathless] (Godard, 1959) France 45. Ben-Hur (Wyler, 1959) USA 46. Ototo [Her Brother] (Ichikawa, 1960) Japan 47. Une aussi longue absence [The Long Absence] (Colpi, 1960) France/Italy?48. Le Voyage en Ballon [Stowaway in the Sky] (Lamorisse, 1960) France 49. Plein Soleil [Purple Noon] (Clement, 1960) France/Italy 50. Zazie dans le métro [Zazie on the Subway](Malle, 1960) France/Italy 51. L’Annee derniere a Marienbad [Last Year in Marienbad] (Resnais, 1960) France/Italy 52. What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (Aldrich, 1962) USA 53. Lawrence of Arabia (Lean, 1962) UK 54. Melodie en sous-sol [Any Number Can Win] (Verneuil, 1963) France/Italy 55. The Birds (Hitchcock, 1963) USA 56. Il Deserto Rosso [The Red Desert](Antonioni, 1964) Italy/France 57. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (Nichols, 1966) USA 58. Bonnie and Clyde (Penn, 1967) USA 59. In the Heat of the Night (Jewison, 1967) USA 60. The Charge of the Light Brigade (Richardson, 1968) UK 61. Midnight Cowboy (Schlesinger, 1969) USA 62. MASH (Altman, 1970) USA 63. Johnny Got His Gun (Trumbo, 1971) USA 64. The French Connection (Friedkin, 1971) USA 65. El espíritu de la colmena [Spirit of the Beehive] (Erice, 1973) Spain 66. Solyaris [Solaris] (Tarkovsky, 1972) Soviet Union 67. The Day of the Jackal (Zinneman, 1973) UK/France 68. Gruppo di famiglia in un interno [Conversation Piece] (Visconti, 1974) Italy/France 69. The Godfather Part II (Coppola, 1974) USA 70. Sandakan hachibanshokan bohkyo [Sandakan 8] (Kumai, 1974) Japan 71. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Forman, 1975) USA 72. O, Thiassos [The Travelling Players] (Angelopoulos, 1975) Greece 73. Barry Lyndon (Kubrick, 1975) UK 74. Daichi no komoriuta [Lullaby of the Earth] (Masumura, 1976) Japan 75. Annie Hall (Allen, 1977) USA?76. Neokonchennaya pyesa dlya mekhanicheskogo pianino [Unfinished Piece for Mechanical Piano] (Mikhalkov, 1977) Soviet Union 77. Padre Padrone [My Father My Master] (P. & V. Taviani, 1977) Italy 78. Gloria (Cassavetes, 1980) USA 79. Harukanaru yama no yobigoe [A Distant Cry From Spring] (Yamada, 1980) Japan 80. La Traviata (Zeffirelli, 1982) Italy 81. Fanny och Alexander [Fanny and Alexander] (Bergman, 1982) Sweden/France/West Germany 82. Fitzcarraldo (Herzog, 1982) Peru/West Germany 83. The King of Comedy (Scorsese, 1983) USA 84. Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence (Oshima, 1983) UK/Japan/New Zealand 85. The Killing Fields (Joffe 1984) UK 86. Stranger Than Paradise (Jarmusch, 1984) USA/ West Germany 87. Dongdong de Jiaqi [A Summer at Grandpa's] (Hou, 1984) Taiwan 88. Paris, Texas (Wenders, 1984) France/ West Germany 89. Witness (Weir, 1985) USA 90. The Trip to Bountiful (Masterson, 1985) USA 91. Otac na sluzbenom putu [When Father was Away on Business] (Kusturica, 1985) Yugoslavia 92. The Dead (Huston, 1987) UK/Ireland/USA 93. Khane-ye doust kodjast? [Where is the Friend's Home] (Kiarostami, 1987) Iran 94. Baghdad Cafe [Out of Rosenheim] (Adlon, 1987) West Germany/USA 95. The Whales of August (Anderson, 1987) USA 96. Running on Empty (Lumet, 1988) USA 97. Tonari no totoro [My Neighbour Totoro] (Miyazaki, 1988) Japan 98. A un [Buddies] (Furuhata, 1989) Japan 99. La Belle Noiseuse [The Beautiful Troublemaker] (Rivette, 1991) France/Switzerland 100. Hana-bi [Fireworks] (Kitano, 1997) Japan

Akira Kurosawa’s List of His 100 Favorite Movies

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abbas Kiarostami, pg 92 of Lessons with Kiarostami

#quotes#quote#lit scraps#film#filmmaking#filmmaker#film director#abbas kiarostami#lessons with kiarostami#inspiration#creative#creative advice

0 notes

Text

‘The greatest documentaries of all time’

La revista Sight & Sound del British Film Institute (BFI, Wikipedia) realizó una lista de los 50 mejores documentales de la historia.

En su realización participaron más de 200 críticos, la mayoría especialistas en documental, y 100 directores, 340 en total junto con programadores. Website.

La relación es la siguiente.

01. ‘Man with a movie camera’, Dziga Vertov, Rusia, 1929, VOSA.

02. ‘Shoah’, Claude Lanzmann, Francia, 1985, VOSFrancés.

03. ‘Sans soleil’, Chris Marker, Francia, 1982, VOInglés.

04. ‘Night and fog’, Alain Resnais, Francia, 1955, VOFrancésSInglés.

05. ‘The thin blue line', Errol Morris, EEUU, 1989, VOInglés.

06. ‘Chronicle of a summer’, Jean Rouch y Edgar Morin, Francia, 1961, VOSE.

07. 'Nanook of the North’, Robert Flaherty, EEUU, 1922, MSEspañol.

08. 'The gleaners and I’, Agnès Varda, Francia, 2000, VOFrancés.

Parte 2.

Parte 3.

Parte 4.

Parte 5.

Parte 6.

09. ‘Dont look back’, D.A. Pennebaker, EEUU, 1967, VOInglés.

09. ‘Grey gardens’, Albert y David Maysles, Ellen Hovde y Muffie Meyer, EEUU, 1975, VOSEspañol.

11. 'The sorrow and the pity’, Marcel Ophüls, Suiza, 1969, VOSEspañol.

Parte 2.

12. 'Grizzly man’, Werner Herzog, EEUU, 2005, VOInglés.

12. 'Land without bread’, Luis Buñuel, España. 1933, VOSEspañol.

12. 'Nostalgia for the light’, Patricio Guzmán, Chile/España/Francia/Alemania/EEUU, 2010, VEspañolSInglés.

15. 'F for fake’, Orson Welles, Francia/Irán, 1975, VOInglés.

15. 'The up series’, Paul Almond (Seven Up!) then Michael Apted, RU, 1964.

17. 'Hoop dreams’, Steve James, EEUU, 1994, VOSEspañol.

17. 'West of the tracks’, Wang Bing, China, 2002.

19. 'The act of killing’, Joshua Oppenheimer, Christine Cynn y anonymous, Dinamarca/Finlandia/RU/Alemania/Holanda/Noruega/Polonia/Suecia, 2012,VOSEspañol.

19. 'The battle of Chile’ ('The insurrection of the bourgeoisie’, 'The coup d'Etat’, ‘The power of the people’), Patricio Guzmán, Chile/Cuba, 1975-78, VEspañol.

Parte 2.

Parte 3.

19. 'The house is black’ (Khaneh siah ast), Forough Farrokhzad, Irán, 1963, VIraníSInglés.

19. 'Listen to Britain’, Humphrey Jennings y Stewart McAllister, RU,1942, VOInglés.

23. 'The emperor’s naked army marches on, Hara Kazuo, Japón, 1987,VOSEspañol.

24. 'Harlan county U.S.A’, Barbara Kopple, EEUU, 1976, VOSE.

24. 'Histoire(s) du cinèma’, Jean-Luc Godard, Francia, 1998, VOFrancés.

24. 'Salesman’, Albert y David Maysles y Charlotte Zwerin, EEUU, 1968, VOSEspañol.

27. 'Titicut follies’, Frederick Wiseman, EEUU, 1967, VOSEspañol.

28. 'Capturing the friedmans’, Andrew Jarecki, EEUU, 2003, VOSEspañol.

28. 'Gimme shelter’, Albert y David Maysles y Charlotte Zwerin, EEUU, 1970, VOInglés.

30. 'Leviathan’, Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel, Francia/RU/EEUU, 2012, VFrancés.

31. 'Lessons of darkness’, Werner Herzog, Alemania, 1992. VOInglés.

31. 'The quince tree sun’, Victor Erice, España, 1992, VEspañol.

33. 'Night mail', Harry Watt y Basil Wright, RU, 1936, VO/VRuso.

33. 'Primary’, Robert Drew, EEUU, 1960.

35. 'Crumb’, Terry Zwigoff, EEUU, 1994, VOSEspañol.

35. 'A diary for Timothy’, Humphrey Jennings, RU, 1946, VOInglés.

37. 'Close-up’, Abbas Kiarostami, Irán, 1989, VO.

37. 'The fog of war’, Errol Morris, EEUU, 2003, VOInglés.

Parte 2.

37. 'Los angeles plays itself', Thom Andersen, EEUU, 2003, VOInglés.

Parte 2.

37. 'Man on wire’, James Marsh, RU, 2007, VOSFinlandés.

37. 'Moi, un noir’, Jean Rouch, Francia, 1959, VOSEspañol.

37. 'Portrait of Jason’, Shirley Clarke, EEUU, 1967.

37. 'À propos de Nice’, Jean Vigo, Francia, 1930, M+BO.

37. 'Roger & me’, Michael Moore, EEUU, 1989, VOSEspañol.

37.'Le sang des bêtes', Georges Franju, Francia, 1948, VOInglés.

37. 'The war game’, Peter Watkins, RU, 1965, VOInglés.

47. ’Culloden’, Peter Watkins, RU, 1964, VOSE.

47. 'Diaries, notes and sketches: Walden', Jonas Mekas, EEUU, 1969, VOInglés.

47. 'D’Est’, Chantal Akerman, Belgica/Francia/Portugal, 1993, VO.

47. 'Handsworth songs’, John Akomfrah, RU, 1986, VO.

47. 'The hour of the furnaces’, Octavio Getino y Fernando Solanas, Argentina, 1968, VEspañolS.

Parte 2.

47. 'Seasons’, Artavazd Pelechian, Rusia/Armenia, 1975, M+BS.

47. 'Triumph of the will’, Leni Riefenstahl, Alemania, 1935, VSEspañol.

47. 'Waltz with Bashir’, Ari Folman, Israel/Francia/Alemania/Japón/EEUU, 2008,VOSEspañol.

47. 'Welfare’, Frederick Wiseman, EEUU, 1975, VOInglés.

47. 'Workers leaving the Lumière factory’, Louis y Auguste Lumière, Francia, 1895, M. (Links de otros segmentos en comentarios del vídeo)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Thinking of this, and how Abbas Kiarostami, an Iranian film director from the 1970s, wrote:

“Painful it is when a single person ---an artist or politician ---decides something on behalf of everyone else. The job of an artist is to bring problems to light, but everybody has a responsibility to contemplate them. The director and audience are equals, on the same footing. Year ago, emerging from a screen of one of my films, I was applauded. So I applauded back.”

(from Lessons with Kiarostami)

How even though life seems to mimic art faster than art mimics life, art has never been the agent of change, but rather a companion of it. The director and audience are on equal footing, the writer and the reader, and once an artist delivers a work, it is up to the audience how they receive or reenact it, be it through media, language, etc.

Art doesn't exist as an invitation to separate the artist from their individual human experience, their personal imagination, or as a figure that is placed on a pedestal and has to act write according to the conditions of that pedestal. Art doesn't necessary have to exist to comfort or enlighten you.

what forms of art, activism, and literature can speak authentically today?

25K notes

·

View notes

Quote

I read a haiku poem a long time ago that said ‘All reports about Hiroshima were broadcast, they were all recorded, but yet no one reported anything about the butterfly wings burned in the distance.’ This photo, the one of the dog burning was inspired by that. It was very painful. I burned my own photo. I burned 50 copies of that photo one by one until one burned just right because they wouldn’t burn the way I wanted to. I wanted to give a little poke so we pay more attention to nature. The damage is not the subset of things being recorded somewhere. This dog didn’t have a record, neither did the butterfly that burned in Hiroshima and no one knew.

Cinematic Lessons from Abbas Kiarostami by Mahmoud Reza Sani

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lessons from the failed 'Palestine' video | Video

Lessons from the failed ‘Palestine’ video | Video

Anyone who knows a little about designing a film or a written film can better understand the work of Herculean who promotes any such project – whether it is good or bad, whether it is very successful or very poor, in opposition. praise or shaky business. Over the years, I have seen many of the world’s most famous filmmakers working; from Ridley Scott to Abbas Kiarostami, Elia Suleiman, Amir…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

1. Broken Blossoms or The Yellow Man and the Girl (Griffith, 1919) USA 2. Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari [The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari] (Wiene, 1920) Germany 3. Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler – Ein Bild der Zeit [Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler] (Lang, 1922) Germany 4. The Gold Rush (Chaplin, 1925) USA 5. La Chute de la Maison Usher [The Fall of the House of Usher] (Jean Epstein, 1928) France 6. Un Chien Andalou [An Andalusian Dog] (Bunuel, 1928) France 7. Morocco (von Sternberg, 1930) USA 8. Der Kongress Tanzt (Charell, 1931) Germany 9. Die 3groschenoper [The Threepenny Opera] (Pabst, 1931) Germany 10. Leise Flehen Meine Lieder [Lover Divine] (Forst, 1933) Austria/Germany 11. The Thin Man (Dyke, 1934) USA 12. Tonari no Yae-chan [My Little Neighbour, Yae] (Shimazu, 1934) Japan 13. Tange Sazen yowa: Hyakuman ryo no tsubo [Sazen Tange and the Pot Worth a Million Ryo] (Yamanaka, 1935) Japan 14. Akanishi Kakita [Capricious Young Men] (Itami, 1936) Japan 15. La Grande Illusion [The Grand Illusion] (Renoir, 1937) France 16. Stella Dallas (Vidor, 1937) USA 17. Tsuzurikata Kyoshitsu [Lessons in Essay] (Yamamoto, 1938) Japan 18. Tsuchi [Earth] (Uchida, 1939) Japan 19. Ninotchka (Lubitsch, 1939) USA 20. Ivan Groznyy I, Ivan Groznyy II: Boyarsky Zagovor [Ivan the Terrible Parts I and II] (Eisenstein, 1944-46) Soviet Union 21. My Darling Clementine (Ford, 1946) USA 22. It’s a Wonderful Life (Capra, 1946) USA 23. The Big Sleep (Hawks, 1946) USA 24. Ladri di Biciclette [The Bicycle Thief] [Bicycle Thieves] (De Sica, 1948) Italy 25. Aoi sanmyaku [The Green Mountains] (Imai, 1949) Japan 26. The Third Man (Reed, 1949) UK 27. Banshun [Late Spring] (Ozu, 1949) Japan 28. Orpheus (Cocteau, 1949) France 29. Karumen kokyo ni kaeru [Carmen Comes Home] (Kinoshita, 1951) Japan 30. A Streetcar Named Desire (Kazan, 1951) USA 31. Thérèse Raquin [The Adultress] (Carne 1953) France 32. Saikaku ichidai onna [The Life of Oharu] (Mizoguchi, 1952) Japan 33. Viaggio in Italia [Journey to Italy] (Rossellini, 1953) Italy 34. Gojira [Godzilla] (Honda, 1954) Japan 35. La Strada (Fellini, 1954) Italy 36. Ukigumo [Floating Clouds] (Naruse, 1955) Japan 37. Pather Panchali [Song of the Road] (Ray, 1955) India 38. Daddy Long Legs (Negulesco, 1955) USA 39. The Proud Ones (Webb, 1956) USA 40. Bakumatsu taiyoden [Sun in the Last Days of the Shogunate] (Kawashima, 1957) Japan 41. The Young Lions (Dmytryk, 1957) USA 42. Les Cousins [The Cousins] (Chabrol, 1959) France 43. Les Quarte Cents Coups [The 400 Blows] (Truffaut, 1959) France 44. A bout de Souffle [Breathless] (Godard, 1959) France 45. Ben-Hur (Wyler, 1959) USA 46. Ototo [Her Brother] (Ichikawa, 1960) Japan 47. Une aussi longue absence [The Long Absence] (Colpi, 1960) France/Italy

48. Le Voyage en Ballon [Stowaway in the Sky] (Lamorisse, 1960) France 49. Plein Soleil [Purple Noon] (Clement, 1960) France/Italy 50. Zazie dans le métro [Zazie on the Subway](Malle, 1960) France/Italy 51. L’Annee derniere a Marienbad [Last Year in Marienbad] (Resnais, 1960) France/Italy 52. What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (Aldrich, 1962) USA 53. Lawrence of Arabia (Lean, 1962) UK 54. Melodie en sous-sol [Any Number Can Win] (Verneuil, 1963) France/Italy 55. The Birds (Hitchcock, 1963) USA 56. Il Deserto Rosso [The Red Desert](Antonioni, 1964) Italy/France 57. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (Nichols, 1966) USA 58. Bonnie and Clyde (Penn, 1967) USA 59. In the Heat of the Night (Jewison, 1967) USA 60. The Charge of the Light Brigade (Richardson, 1968) UK 61. Midnight Cowboy (Schlesinger, 1969) USA 62. MASH (Altman, 1970) USA 63. Johnny Got His Gun (Trumbo, 1971) USA 64. The French Connection (Friedkin, 1971) USA 65. El espíritu de la colmena [Spirit of the Beehive] (Erice, 1973) Spain 66. Solyaris [Solaris] (Tarkovsky, 1972) Soviet Union 67. The Day of the Jackal (Zinneman, 1973) UK/France 68. Gruppo di famiglia in un interno [Conversation Piece] (Visconti, 1974) Italy/France 69. The Godfather Part II (Coppola, 1974) USA 70. Sandakan hachibanshokan bohkyo [Sandakan 8] (Kumai, 1974) Japan 71. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Forman, 1975) USA 72. O, Thiassos [The Travelling Players] (Angelopoulos, 1975) Greece 73. Barry Lyndon (Kubrick, 1975) UK 74. Daichi no komoriuta [Lullaby of the Earth] (Masumura, 1976) Japan 75. Annie Hall (Allen, 1977) USA

76. Neokonchennaya pyesa dlya mekhanicheskogo pianino [Unfinished Piece for Mechanical Piano] (Mikhalkov, 1977) Soviet Union 77. Padre Padrone [My Father My Master] (P. & V. Taviani, 1977) Italy 78. Gloria (Cassavetes, 1980) USA 79. Harukanaru yama no yobigoe [A Distant Cry From Spring] (Yamada, 1980) Japan 80. La Traviata (Zeffirelli, 1982) Italy 81. Fanny och Alexander [Fanny and Alexander] (Bergman, 1982) Sweden/France/West Germany 82. Fitzcarraldo (Herzog, 1982) Peru/West Germany 83. The King of Comedy (Scorsese, 1983) USA 84. Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence (Oshima, 1983) UK/Japan/New Zealand 85. The Killing Fields (Joffe 1984) UK 86. Stranger Than Paradise (Jarmusch, 1984) USA/ West Germany 87. Dongdong de Jiaqi [A Summer at Grandpa’s] (Hou, 1984) Taiwan 88. Paris, Texas (Wenders, 1984) France/ West Germany 89. Witness (Weir, 1985) USA 90. The Trip to Bountiful (Masterson, 1985) USA 91. Otac na sluzbenom putu [When Father was Away on Business] (Kusturica, 1985) Yugoslavia 92. The Dead (Huston, 1987) UK/Ireland/USA 93. Khane-ye doust kodjast? [Where is the Friend’s Home] (Kiarostami, 1987) Iran 94. Baghdad Cafe [Out of Rosenheim] (Adlon, 1987) West Germany/USA 95. The Whales of August (Anderson, 1987) USA 96. Running on Empty (Lumet, 1988) USA 97. Tonari no totoro [My Neighbour Totoro] (Miyazaki, 1988) Japan 98. A un [Buddies] (Furuhata, 1989) Japan 99. La Belle Noiseuse [The Beautiful Troublemaker] (Rivette, 1991) France/Switzerland 100. Hana-bi [Fireworks] (Kitano, 1997) Japan

0 notes

Text

I’m reading Lessons With Kiarostami & when he was talking about Taste of Cherry, he said that there was a like lingering presence of a woman connected with Mr. Badii, & that’s like....so strange to me bc I almost never thought of a woman in his life save for near the end when he goes back to his house & I wondered if he had a family

#honestly thats probably bc Mr. Badii is a total self insert for me & thats blinded me to the visual storytelling :/#personal#i always try to bring myself to watch it again but its like#‘oh god oh god oh my god oh god’ everytime i take it out to watch#ive attatched way too much personal significance to that movie for my own good lol

0 notes